Archive for the 'National cinemas: New Zealand' Category

Venice 2019: Repremieres

The Spider’s Strategem (1970).

Kristin here:

The policy at the Venice International Film Festival is to show only world premieres of films. Luckily that includes premieres of restored prints of classic films. These form a major thread in the program here, and this year had been particularly rich in older films that have been unavailable or available only in incomplete or poor prints. We have been catching up with some favorites and were introduced to unfamiliar ones.

The Spider’s Strategem (1970)

Back in the mid-1970s, David and I taught Bernardo Bertolucci’s film, which he made directly after the better-known The Conformist (also 1970). Thanks to the New Yorker print, we came to know it well, and when we wrote Film Art: An Introduction, an example of it went in and has stayed in. David analyzed the film’s storytelling principles at length in Narration in the Fiction Film.

The film came out in VHS versions in the US and UK, both out of print, but it never was released on DVD or Blu-ray. Now it returns in a stunning restoration from Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna and Massimo Sordella. (The restored version is out on Blu-ray in Japan, but without English subtitles.)

The plot involves a young man, Athos Magnani, who returns to the village where his father, who shares his name and appearance, gained a reputation as a bold leader of a small resistance group during the 1930s. He was also mysteriously murdered. The father’s mistress, Draifa, urges his son to stay and investigate the crime, and, it is hinted, to take his father’s place in her bed.

Young Magnani does investigate, but he quickly becomes uncertain as to which villagers were his father’s friends and which his enemies. He also finds himself targeted with threats of violence. Flashbacks mix scenes of past and present with no attempt to differentiate them via period props, changing ages, or stylistic contrasts. The ambiguities, which continue to the end, are not surprising, given that the literary source was a Jorge Luis Borges short story.

Whether or not one enjoys the teasing plot, the visuals are enough to provide delight. The cinematography was done by two major Italian cinematographers: Franco Di Giacomo (The Night of the Shooting Stars, Il Postino) and Vittorio Storaro, known for his bold use of color (Dick Tracy, Tucker: The Man and His Dream, and Tango). The result (see top) is like a blend of classical paintings and an Italian fruit stall.

Now all we need is a Blu-ray release worthy of the print shown here.

Maria Zef (1981)

This was Italian director Vittorio Cottafavi’s penultimate work, made after he has worked almost exclusively in television since the beginning of the 1960s. It has a pleasantly old-fashioned look, perhaps not too surprising in that Cottafavi says he conceived it in 1938, two years after the source novel appeared. He was not able to make it until 1981, when it was seen a project local to the Friuli region of northeastern Italy.

Some internet sources list it as a TV series, but IMDb and others treat it as a film. Certainly it looks like a film and seems to have no obvious pause points. But it was produced by RAI and was shot in the TV-friendly Academy ratio rather than the wider formats that were standard by the 1980s. (While I was watching it, I thought of it as a much earlier film and was surprised to find that it was made so late.)

Maria, an adolescent girl, is traveling with her irrepressible younger sister Rosute and her dying mother. They carry a cart full of domestic implements to sell. The two are taken in by their uncle, Barbe Zef, who made the spoons and other wooden housewares that the trio had been peddling. He’s a gruff fellow, and violent when drunk. Under the influence, he rapes Maria and tries to stifle her subsequent resentment as if his attack had been just a natural impulse.

The film was shot on location in the Italian Alps (above). The region of Friuli will be familiar to many film scholars and buffs who have traveled there for the “Giornate del Cinema Muto” silent-film festival in Pordenone.

The restoration was done by Rai Teche. With luck, the new print will travel abroad and introduce Cottafavi, an Italian favorite, to broader audiences.

[September 10: Thanks to blogger Manfred Polak for providing further information on Maria Zef. He provides a link to a brief piece on the film at the Cineteca de Friuli website. This piece (in Italian) says the film will play at the I Milleocchi festival in Trieste, 13-18 September 2019. The Cineteca also plans a DVD release with numerous supplements. Its earlier release of Vito Pandolfi’s Gli ultimi had optional English subtitles, so perhaps the Maria Zef DVD will as well.]

Mauri (“Life force,” 1988)

This restoration from the New Zealand Film Commission and Park Road Post Production should make available a nearly forgotten classic of New Zealand cinema. It remains the only New  Zealand feature with a Māori woman, Merata Mita, as sole director. (In 1972, To Love a Māori had been co-directed by the husband-wife team Raimi and Rudall Hayward.) Mita had previously made the first feature-length documentary by a Māori woman, Patu! (1983). Much of her career was devoted to documentary filmmaking.

Zealand feature with a Māori woman, Merata Mita, as sole director. (In 1972, To Love a Māori had been co-directed by the husband-wife team Raimi and Rudall Hayward.) Mita had previously made the first feature-length documentary by a Māori woman, Patu! (1983). Much of her career was devoted to documentary filmmaking.

The plot centers largely around an interracial love triangle. Māori woman Ramari is loved by Steve, a white farmer who was schooled alongside Māori children and retained Māori friends as an adult. His father, however, is a rabid and apparently crazy racist who tries a variety of pranks, some violent, to break up the match. Ramari loves a Māori man, Rewa, who harbors a dark secret that prevents him from marrying her.

This drama plays out against the intertwined doings of the family and circle of friends headed by the matriarch Kara. She tries to instill traditional values into her children, grandchildren, and the various troubled people she has treated as her own offspring. The film is set and shot in a tiny, declining village, Te Mata, in the East Cape area of the North Island, south of the now-thriving Hawke’s Bay winery region.

According to the biographical page linked above, “Mita said she had consciously rejected Pākehā traditions of storytelling and embraced a layered approach, in keeping with the strongly oral traditions of Māori. She told writer Cushla Parekowhai: “These are differences that Pākehā critics don’t even take into account when they’re analyzing the film.” Pākehā is the Māori word for white people.

There are rare films, and here I think of Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger, that are entirely set in a specific non-white culture and make no attempt to explain that culture to a white audience. Clearly Mita was trying for the same approach. Her film met with some criticism for not following mainstream conventions of film narrative. Nevertheless, like To Sleep with Anger, Mauri draws in viewers with its drama and appealing characters. Today audiences with a greater openness to other cultures will most likely greet this restored version with greater sympathy and appreciation.

Death of a Bureaucrat (1966)

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea is undoubtedly Cuba’s most famous and revered director. Even those with the most passing knowledge of Cuban cinema will know such titles as Memories of Underdevelopment (1968) and Strawberry and Chocolate (1993). Death of a Bureaucrat is another familiar title, restored by the Academy Film Archive and the Cinemateca de Cuba. The screening was introduced by our old friend Joe Lindner, Preservation Officer at the Academy Archive.

The film is essentially a slapstick farce on a rather unlikely topic, the burial and reburial of the titular bureaucrat. He was a man who distinguished himself by inventing a machine to mass-produce the white busts of political leaders which stand in every government office in Communist countries (and which resemble the bust on the bureaucrat’s tombstone, above). The plot, however, is set off when it is discovered that as a tribute to such a genius, the dead man’s work card has been buried with him, and his widow needs it to receive her benefits.

The rest of the film is a series of escalating efforts by the man’s son to track down the exhumation order which the cemetery officials demand if they are to be able to rebury the body after the card is retrieved. Numerous stamps, signatures, and forms are required, all of which can only be provided by a single person–naturally different in each case. The hero becomes increasingly desperate and begins to try stealth, slipping into an office after closing hours and smuggling his father’s coffin into the graveyard to rebury it himself. All the while the grieving widow gathers all the ice her friends and neighbors can supply to prevent the body, kept at her house, from deteriorating.

The action is amusing enough, including one scene where a hearse is revealed to have a small plastic skeleton dangling from its rear-view mirror. The action does become somewhat repetitious and drawn-out, and one gets the feeling at times that the humor is perhaps aimed at an uneducated audience of workers and peasants, comparable to the Socialist Realism imposed upon filmmakers in the Soviet Union after the 1920s.

It’s interesting that such criticism of the workings of government would be permitted, and yet bureaucratic red tape seem to have been a somewhat safe target for Communist filmmakers, especially if presented as a sort of holdover of bourgeois practices. In the 1920s the Soviets had My Grandmother (Kote Mikaberidze, 1929) and The State Functionary (Ivan Pyriev, 1930), and Death of a Bureaucrat somewhat recalls them.

Extase (1933)

Each of the three years we have visited the Venice International Film Festival, there has been a preliminary evening where a restored early film has been shown. The first year saw the restored Rosita, the second Der Golem, both with orchestral accompaniment. This year there was an early Czech sound film, Gustav Machatý’s Ecstasy.

Having see the film only in the incomplete version that circulated in 16mm in the US for many years, I must say that I had not been impressed. The new restoration by the Národni filmový archiv, with much support from other archives, is a very different film indeed.

The story makes more sense now. It begins with the heroine, played by Hedy Kiesler-Lamarr (as she was then) as a young women who marries a wealthy older man. He turns out to have little interest in passionate love, and she is left on her own to be seduced by a young engineer working on a project near her husband’s estate. The film became famous for its scene of the heroine swimming nude, as well as her first, explicit for its day, love scene with the engineer.

The melodrama works its way out, with the rich man killing himself and the heroine, feeling guilty, leaving her lover. At this point, in the restored print, an abrupt switch to a lengthy sequence shows the engineer returning to work, with a joyous celebration of labor depicted in an imitation of Soviet films of the era. This incongruous ending to the plot comes quite unexpectedly, creating a film very different from the versions available hitherto.

Extase remains a less than wholly satisfactory film, but it now reveals its mixture of various influences of the era: the subjectivity of French Impressionism, the soft style of cinematography from the silent era, and in its ending, the propaganda and montage construction of Soviet cinema. Like Genina’s Prix de Beauté (1930), it’s an early-sound effort to preserve the aesthetics of mature silent cinema.

The evening definitely provided a new, startling version of a hitherto mutilated classic.

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for the invitation for David to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Our collaborator Jeff Smith provided a video analysis of another Alea film, Memories of Underdevelopment, for the Criterion Channel. He discusses it in this May blog post.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

September 10: Thanks to Hamish Ford and Lee Tsiantis for information concerning The Spider’s Strategem‘s releases on VHS and Japanese Blu-ray.

September 18, 2019: Thanks to Gareth McFeely for corrections on dates and spellings in the section on Mauri.

Mauri (1988).

Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker

Thor: Ragnarock (2017).

Kristin here:

Not every independent filmmaker secretly longs to direct a big Hollywood blockbuster. Jim Jarmusch made a name for himself 33 years ago with Stranger than Paradise (1984) and won well-deserved praise for Paterson last year. Like other independent directors, Hal Harley turned from filmmaking to streaming television, directing episodes of Red Oaks (2015-2017) for Amazon.

Still, in recent decades the big studios have picked young directors of independent films or low-budget genre ones to leap right into big-budget blockbusters, and those directors have taken the plunge. Doug Liman’s Go (1999) was one of the quintessential indie films of its decade, but his next feature was The Bourne Identity (2002). Colin Trevorrow’s modest first feature Safety Not Guaranteed (2012, FilmDistrict) led straight to Jurassic World (2015, Universal); Gareth Edwards’ low-budget Monsters (2010, Magnolia) was directly followed by Godzilla (2014, Sony/Columbia) and Rogue One (2016, Buena Vista); and Josh Trank went from a $12 million budget for Chronicle (2012, Fox) to ten times that for the $120 million Fantastic Four (2015, Fox).

Something similar happens occasionally with foreign directors. Tomas Alfredson went from the original Swedish version of Let the Right One In (2008, Magnolia) to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011), and the Norwegian team Joachim Ronning and Espen Sandberg, after making Bandidas (2006, a French import released by Fox) and Kon-Tiki (2012, a Norwegian import released by The Weinstein Company) were hired to do Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017, Walt Disney Pictures) and the upcoming Maleficent 2.

Recently women have followed this pattern as well: Patty Jenkins, going from Monster (2003, Newmarket Films) via a long stint in television to Wonder Woman (2017, Warner Bros.), and Ava DuVernay, from two early indie features and Selma (2014, Paramount), again via television, to A Wrinkle in Time (forthcoming 2018, Walt Disney Pictures).

Some of these directors have made the transition smoothly and successfully and some have not. Perhaps the most spectacular success has been that of Christopher Nolan, who went from Memento (2000) via Insomnia (2002) to Batman Begins (2005) and far beyond. But more about him later.

Why have indie filmmakers been able to make this move into the mainstream, often quite abruptly? What about their work appeals to the studios? Of course, there are a variety of reasons, depending on the project and the producers involved. It might be worth following one filmmaker’s career up to the transition to see if there are any clues.

A recent example of this trend is the box-office hit Thor: Ragnarok (released November 3), in the Marvel universe, owned by Walt Disney Studios. Its director, New Zealander Taika Waititi, had directed a handful of modestly budgeted films in his native country. The most successful of those, Boy (2010) made $8.6 million worldwide. After a month in release, Thor will cross $800 million this coming weekend, if not before, and will ultimately gross more than 100 times as much as Boy.

Every filmmaker takes his or her own path before making this leap into blockbuster projects. Waititi did not set out with the ambition to direct a superhero movie with an absurdly high budget. But his career was so full of luck early on that it hardly could have gone better if he had planned it. If you sought a model path to blockbuster fame, you could do no better than to imitate him.

Start by getting nominated for an Oscar

Waititi was actually preparing for a career as a painter, but he was also doing a lot of performing: stand-comedy and film and television acting, perhaps most notably as one of the young flatmates in Roger Sarkies’ 1999 classic, Scarfies. His first brush with superhero movies came with a small role in Green Lantern, 2011. He also, however, made some short amateur films for the 48-Hour film project in Wellington. (Possibly I saw one of them, since I attended the program of shorts during my first visit to Wellington in 2003.) That led to his first professional film, the 11-minute Two Cars, One Night (above).

Virtually all indies made in New Zealand are funded by the New Zealand Film Commission, and in this case the NZFC’s Short Film Fund financed Two Cars. In January, 2004 it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, with which Waititi soon became closely linked. It’s available on YouTube, but be prepared to pay close attention if you hope to understand the thick, rural Kiwi dialect of the charming non-professional child actors. (Waititi’s Wikipedia entry has a good rundown of his television and other work as well as his films.)

The film got nominated for a best live-action short Oscar, and although it didn’t win that, it picked up prizes from the Berlin, AFI, Hamburg, Oberhausen, and other festivals, as well as the New Zealand Film and TV Awards. In fact, the short effectively drove Waititi into filmmaking, as he described in a 2007 interview.

I spent years doing visual arts, doing painting and photography, and throughout that whole time I was acting quite a lot in theater and New Zealand film and television. But for that whole time I wasn’t really sure which one of those artforms I wanted to concentrate on, and eventually just started tinkering around with writing little short films. I made one short film which ended up doing really well, and then suddenly I was propelled into this job as a filmmaker. But actually I didn’t want to be a filmmaker, I just wanted to make short films to try it out! I still don’t really think I’m a filmmaker.

Perhaps not then, but the idea must be quite plausible to him by now.

Get support from the Sundance Institute ASAP

The short and its Oscar nomination launched Waititi’s move into feature filmmaking. In 2005 it was announced that Waititi had been accepted into the Sundance Directors and Screenwriters labs to develop A Little Like Love, which later became his first feature, Eagle vs. Shark.

It was really good for getting my feature made, because I kinda got fast-tracked in the funding process. In New Zealand, the only way of getting a movie done is through the Film Commission, the government agency that funds everything. So I got nominated for the Oscar in March 2005, I wrote the screenplay for Eagle vs Shark in May, then we went to the Sundance Lab in June, got funding from the Film Commission in August, and we were shooting in October.

In January, 2007, Eagle vs. Shark premiered at Sundance. It got a small release in the USA. Having followed filmmaking in New Zealand during work on my book The Frodo Franchise, I saw it here in Madison in a nearly empty theater.

Asked in the same interview about his experiences in the Sundance Directors and Screenwriters labs, Waititi replied:

It was just totally amazing, totally amazing! I think the biggest thing I took away from the lab was finding the tone for the film. In the marketing, it’s going to be presented as a comedy, and I think that’s where a lot of the problems will lie. Even in the criticism of the film, people don’t get that it’s not pure comedy.

The power of the Sundance Institute in supporting first feature films and in others ways promoting independent production worldwide is surprisingly little known. Most obviously the labs have aided the development of American indies like Miranda July’s Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005), as well as supporting Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash (2014) through the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. The Institute’s impact goes beyond the USA. The first film made in Saudi Arabia, Haifaa Al Mansour’s Wadjda (2012), also was aided by the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. Sundance’s website emphasizes that the grants and participation in labs is not just for a single film:

With more than 9,000 playwrights, composers, digital media artists, and filmmakers served through Institute programs over the last 35 years, the Sundance community of independent creators is more far-reaching and vibrant than ever before.

If you have been selected for any Institute lab program or festival, you are a member of this community. Sundance alumni receive support throughout their careers, including access to tools, resources and advice as well as artist gatherings and more. Alumni are also encouraged to actively contribute to the Institute’s creative community and to our mission to discover and develop work from new artists.

Waititi’s second feature, Boy, which premiered in January, 2010, carries the credit, “Developed With The Assistance Of Sundance Institute Feature Film Program.” What We Do in the Shadows, co-directed with comedy partner Jemaine Clement, premiered there in January, 2014, though without a credit to Sundance, but his most recent independent feature, Hunt for the Wilderpeople (January, 2016) gave “Special Thanks” to the Sundance Institute.

Asked about Sundance in 2016, when Hunt for the Wilderpeople had just premiered, he declared,

I’ve got a good relationship with them, I love coming here, and I do think that this festival suits my films rather than most of the festivals I’ve been to. I’m not going to Cannes, you know.

Waititi has taken his membership in this exclusive group seriously. In 2015, Sundance created the Native Filmmakers Lab, aimed at supporting Native American and other Indigenous filmmakers. Such support had been a policy in choosing filmmakers to participate in labs up to that point, and Waititi is mentioned as one of past participants. He also is listed as the only individual among a list of major institutions contributing to the Sundance Institute Native American and Indigenous Program:

The Sundance Institute Native American and Indigenous Program is supported by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, Surdna Foundation, Time Warner Foundation, Ford Foundation, Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, SAGindie, Comcast-NBCUniversal, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Embassy of Australia, Indigenous Media Initiatives, Taika Waititi, and Pacific Islanders in Communications.

Taika Waititi’s father was a member of the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui group of the Mãori people, and his mother was a Russian Jew. Waititi used the name Taika Cohen in his early years as an actor.

Live in Wellington, New Zealand

Part of Waititi’s luck consisted of starting his filmmaking career just as Peter Jackson and his team had transformed filmmaking in New Zealand by building up the state-of-the-art production and post-production facilities needed to made The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003). Peter Jackson, Richard Taylor, and Jamie Selkirk, the co-owners of The Stone Street Studios, Weta Workshop, and Weta Digital, offered services by these firms at cost to New Zealand filmmakers; Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh did the same with The Film Unit (later Park Road Post), a lab with sound-mixing and editing facilities. Indeed, it was the only lab for developing film in New Zealand.

From the start, Waititi could take advantage of this large support system. The credits for Two Cars, One Night (above) include Weta Digital for the special effects and The Film Unit for post-production. The credits of the 2005 short version of What We Do in the Shadows thanked Selkirk and Park Road Post, as well as Peter Jackson, who offered undisclosed further support. Beasts of the Southern Wild credits three companies for its special effects, including Weta Digital for the wild-pig episode and Park Road Post for sound-mixing, along with “Very Special Thanks” to the Sundance Institute.”

Having toured those companies in 2003 and 2004, I can state that few indie filmmakers have had access to such sophisticated facilities.

Make some good, eccentric films

Waititi’s first film to capture wide attention was Boy, based loosely on his experiences growing up in a village on the upper east coast of New Zealand’s north island. The director played the young protagonist’s irresponsible father, a comically incompetent gang leader who had deserted his family and returns home to dig up some stolen money he and his pals have buried in an enormous field–without marking where it is. He strives to be a good father, mostly by showing off, as when he tries to casually leap into his car through the window and ends up in a struggle that embarrasses Boy in front of his young friends (above).

It’s a film that brought the blend of poignancy and offbeat humor that Waititi had established in Eagle vs. Shark to maturity.

He followed it with a very different film, What We Do in the Shadows (2014), a mockumentary about three vampire flatmates living in Wellington. (The reference in Thor: Ragnarok to a three-pronged spear for killing multiple vampires is to the main characters of Shadows.) Here the poignancy is gone and the humor pushed to extremes in a fashion that recalls the Monty Python team. In fact, it’s similar to the silly humor of Thor.

Finally, Hunt for the Wilderpeople, a tale of a rebellious foster child going on the lam with his foster “uncle” in the wilds of New Zealand, ultimately made somewhat less money internationally than the other two but had an enthusiastic critical response in the US. There was some Oscar buzz surrounding it, though no nominations resulted. It was, however, a huge success at home, becoming the highest-grossing New Zealand film ever, taking that title away from Boy, which had taken it from the classic Once Were Warriors (1994). It also won best film, director, actor, supporting actress, and supporting actor at the New Zealand Film and TV Awards. Sam Neill’s participation in this film led to his cameo in Thor: Ragnarock.

Coming into the mid 2010s, Waititi had built a solid career as an independent maker of likable, entertaining, skillfully made–and funny– films.

Get tapped for a blockbuster

How and why did Marvel choose Waititi? One might suspect that it was because he already had a Disney connection. When Moana was in pre-production, they brought in many people native to Polynesia to help with planning and design. (Little-known fact: New Zealand is part of Polynesia.) Waititi was brought aboard and wrote a first draft of the script, most of which was altered in later drafts.

When asked if the Moana work had anything to do with the Marvel invitation, however, Waititi responded,

Well, they had not heard of the Disney thing so I know that wasn’t part of it. They have a record making out there and exciting choices and I think what they said to me was, “We want it to be funny and try a whole new tack. We love your work and do you think you can fit in with this?”

Waititi got the call from Marvel in 2015, when he was editing Hunt for the Wilderpeople. USA Today interviewed him in early 2016, when the film premiered.

“They were looking for comedy directors,” he says. “They had seen What We Do in the Shadows and Boy. They especially liked Boy.”

The result was exactly what the Marvel people were after, since the largely positive reviews have invariably cited the humorous, even self-parodic tone of the film. In interviews, Waititi has often spoken of the scene in which Thor and the Hulk have a fight and then sit down to talk about their feelings (top). He wanted to add it because it was the sort of thing that never happens in superhero movies. The Marvel people seem to have liked it. An excerpt provided the tag ending for the first official trailer.

Upstage your actors

I would wager that fans know more about what Taika Waititi looks like than they do about most of the other blockbuster directors mentioned above. He already enjoyed something of a fan base from his earlier films, largely the cult following of What We Do in the Shadows. He remains an actor, playing a major role in some of his own films (Boy, What We Do in the Shadows) and a minor one in others. He’s been a stand-up comic, so he can keep the patter going in interviews and fan-convention panels.

In July, he stole the Thor: Ragnarok Hall H panel at Comic-Con, cracking up the big stars on the panel and getting more laughs from the audience than all of them put together. Waititi’s public persona makes him resemble a character in one of his own films.

Indeed, he again played a supporting character in Thor: Ragnarok, though not exactly in persona proper: Korg, the fighter made of stone. Waititi did both the motion capture and the voice for Korg, and I found the first scene between him and Thor to be the funniest in the whole film.

Even before the release of the film, Waititi quickly gained a reputation for his eccentric clothing preferences. He wore a matching pineapple-print shirt and shorts to the Comic-Con panel (seen in two of the above images). Ava DuVernay was widely quoted as calling Waititi the “best-dressed helmer” in the entertainment world, including in The Hollywood Reporter‘s story on how the director has become a “fashion superhero.” Maybe Waititi is not yet as recognizable to the public as the stars in his film are, but that may not last long. On the day Thor: Ragnarok was released, GQ profiled him, with several photos in different outfits, declaring that he “drips with cool.”

Waititi does cool things that appeal to fans. To raise the money to release Boy in the North American market, he started a Kickstarter campaign with a goal of $90,000 and raised $110,796. He directed one of the popular series of comic Air New Zealand safety announcements based on The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, “The Most Epic Safety Video Ever Made,” with himself playing the Gandalf-like wizard (see bottom). He has 262 thousand followers on twitter and tweets frequently. (This does not count the many unofficial pages like TaikaWaititi Fashion, with 978 followers.)

One-for-them, one-for-me respectability

Once admired indie directors start making blockbusters, they often stress that it is a way of getting smaller budgets for more personal projects of the sort that made them admired to begin with. The generation of movie brats, such as Francis Ford Coppola, established this notion of trade-offs with the big studios.

Perhaps as successfully as anyone in Hollywood, Christopher Nolan has shown quite clearly that such trade-offs can work. Once Memento (2000) made his reputation, he followed it with one mid-budget film, Insomnia (2002) and reached the heights of superhero-dom with Batman Begins. The pattern of alternating personal and one-for-them films is evident from the budgets and worldwide grosses of his subsequent films–although he has become so popular that most studios would happily settle for his “one-for-me” grosses:

Memento (2000, reported budget $9 milion; worldwide about $40 million), Insomnia (2002, reported budget $46 million; worldwide $113 million), Batman Begins (2005, reported budget $150 million; worldwide $375 million), The Prestige (2006, reported budget $40 million; worldwide $110 million), The Dark Knight (2008, reported budget $185 million; worldwide, $1. 005 billion), Inception (2010, reported budget $160 million; worldwide $825 million), The Dark Knight Rises (2012, reported budget $250 million; worldwide $1.085 billion), Interstellar (2014, reported budget $165 million; worldwide $675 million), and Dunkirk (2017, reported budget $100 million, worldwide $525 million, with an Oscar-season re-release announced).

Waititi has invoked this notion of returning to his indie roots at intervals. In 2015 We’re Wolves, a sequel to What We Do in the Shadows, was announced, again to be co-directed by Jemaine Clement. Presumably, however, that project was put on hold, but not abandoned, for Thor. He has other scripts in the drawer and in one interview says, “I’m excited to go back and do those, and then I’d like to come back and do something else here. You know, a one-for-them, one-for-you kind of scenario.”

He has specifically said he would be up for another Thor film:

“I would like to come back and work with Marvel any time, because I think they’re a fantastic studio, and we had a great time working together,” Waititi told RadioTimes.com. “And they were very supportive of me, and my vision.

“They kind of gave me a lot of free reign [sic], but also had a lot of ideas as well. A very collaborative company.”

Specifically, he went on, “I’d love to do another Thor film, because I feel like I’ve established a really great thing with these guys, and friendship.

“And I don’t really like any of the other characters.”

The question is, will Hollywood let him go, at least for now?

Waititi’s first decade or so of filmmaking suggests some reasons why he was approached to make a $180 million epic. The Marvel producers were specifically looking for comedy. Comedies are supposedly harder to sell abroad, but put funny material into a big sci-fi film, and it can do just fine overseas. Many of the other indie filmmakers who made this transition started with genre films–low budget crime or sci-fi films.

Moreover, the Marvel producers who approached him were also willing to give him a free rein, so they were presumably trusting and open to someone whose work they admired. Not all producers would be so lenient. It no doubt helped that in this case, the studio was specifically looking for something original and funny–in short, different from the stolid reputation that the Thor films had gained among critics and viewers alike.

The Most Epic Safety Video Ever Made (c. 2014)

A decade at the Vancouver International Film Festival

The Red Turtle (2016).

Kristin here:

Recently this blog passed its tenth anniversary. Our first modest entry, on Christine Vachon’s book A Killer Life, was posted on September 26, 2006. The second was “A film festival for all seasons,” the first of David’s five reports on that year’s Vancouver International Film Festival, where he was a judge in the Dragons and Tigers competition for young Asian directors. Since then we both have come to VIFF nearly every year. Its organizers and staff are always welcoming and we can see lots of films in a relatively relaxed atmosphere free from the red carpets, the markets, and the celebrities that make some of the bigger festivals difficult to navigate. We’re delighted to be back in Vancouver now, reporting on its rich array of offerings for a tenth time.

The Rehearsal

Canadian-born, New Zealand-bred, New York-dwelling director Alison Maclean gives us The Rehearsal (2016), her first feature since her best-known film, Jesus’ Son (1998). In between she has been primarily working in television, including episodes of Sex and the City and The Tudors.

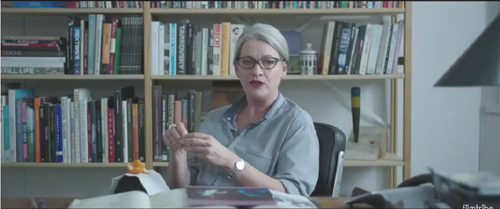

The film begins with an image of an Asian woman in a blonde wig and ultra-high-heel shoes facing directly into the camera and miming a tennis game (see bottom). Such an arresting opening is a wise move, since the film’s early portions are mostly expository. The opening introduces Stanley, a young Maori man who gains acceptance to a high-pressure, prestigious drama school, despite his apparent lack of the necessary talent and drive. Overcoming his initial listlessness, Stanley gradually bonds with his classmates. He also blossoms somewhat under the tough-love approach, sometimes verging on cruelty, that is the policy of Hannah, the demanding head of the school (Kerry Fox, above, best known for playing Janet Frame in An Angel at My Table).

The opening image turns out to be a flashforward to a rehearsal of an original playlet that Stanley and a group of teammates must put on at the end of the school year. For their story they seize upon a current local scandal in which a tennis coach has had an affair with an underage pupil. Stanley has begun dating the girl’s sister Isolde, which gives him knowledge about the situation that the group incorporate into their play. The main suspense arises from Stanley’s failure to tell Isolde what his team is up to, despite the fact that inevitably she will find out. More drama arises from the effects of Hannah’s harsh methods on the students, particularly Stanley’s vulnerable roommate.

The Rehearsal currently has no American distributor but will play on October 5 at the New York Film Festival.

The Confessions (Le Confessioni)

Early in The Confessions a spectacular drone shot follows a moving car from above the treetops. Eventually the car arrives at a driveway crowded with news photographers, and the camera leaves it to reveal a huge modern hotel and then move beyond it over ta body of water. Though not as flashy, the rest of the film has the sort of lush cinematography (above) and rich musical score that are familiar from such other recent prestigious Italian productions as The Great Beauty.

The plot involves a sort of bitter parody of a G8 meeting, with eight representatives of major countries meeting under the guidance of the head of the International Monetary Fund. They are preparing to execute some sinister plan, under the guise of “creative destruction,” that will solve a current international financial crisis in a way that will benefit rich countries at the expense of the poorest ones. Daniel Roché, the head of the IMF, has also invited an Italian monk, Roberto Salus (played by Tony Servillo, so memorable in The Great Beauty and especially Il Divo), to attend.

The reason for Salus’ presence is not clear, though Roché requests him to hear his first confession in twenty years. Roché is soon found dead. It’s apparently a suicide, but some of the finance ministers attending the meeting seemingly try to eliminate Salus by casting him under suspicion of murder. The film turns into a cat-and-mouse game, with each seeking out Salus for devious conversations, punctuated with tantalizing flashbacks that gradually reveal what Roché had revealed during the confession scene.

Although on the surface the film seems to be developing into a thriller, it is too playful to be taken entirely seriously, and the wise, reserved Salus always delivers the final sardonic comic topper in his exchanges with each of the villains. There is even a suggestion of a sort of magical realism at a few points. Ultimately The Confessions is a somewhat uneasy mixture of genres but a highly entertaining one.

The Red Turtle

In the early days of the blog (December 10, 2006), I wrote an entry claiming that in contemporary cinema, animated films are on average more likely to be stylistically superior to live-action ones. Animated films have to be intensively pre-planned, including recording soundtracks in advance. Such careful preparation, which eliminates the easy reliance on “coverage” and limits changes in post-production, imparts a rigor and care that are too often missing in live-action features. Two experiences with animated films here at Vancouver reinforce my point.

David and I agree that The Red Turtle is a standout among the films we’ve seen so far. It’s an animated feature by Michael Dudok de Wit, the Dutch animator who won the animated-short-film Oscar in 2000 for Father and Daughter. The Red Turtle won a Special Jury Prize at Cannes this year. It also has Studio Ghibli’s name attached, which might lead to some raised eyebrows.

Studio Ghibli’s three legendary animators all retired in recent years: Hayao Miyazaki, after The Wind Rises (2013); Isao Takahata, after The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013); and Hiromasa Yonebayashi, after When Marnie Was There (2014). Rumors that the studio would shut down fortunately proved false, despite the fact that its crew of animators was disbanded. The Red Turtle is the first film to bear the Studio Ghibli name since Marnie. The studio, not Dudok de Wit, initiated the project, and perhaps it will henceforth support occasional hand-picked productions like this one.

Though The Red Turtle uses traditional cell animation, it does not particularly imitate the studio’s familiar style Nevertheless, the film is far from being a radical departure from its previous output. For one thing, The Red Turtle is vitally concerned with the depiction of nature. It opens with a storm that drives a single survivor from a shipwreck onto the beach of a small island, uninhabited by humans. His first contact with living things there comes when a curious sand-crab crawls up his pant-leg, and a group of these crabs provides touches of comic relief throughout.

Three times the unnamed man tries to escape aboard bamboo rafts (above), but each time a large red sea turtle destroys his craft (see top) and forces him back to the island. In the story’s first fantastical event, the turtle transforms into a woman, and the two soon fall in love, Adam and Eve in a sparse Garden of Eden. They gain a son, a tsunami introduces a note of threat into the idyllic depiction of nature, and ultimately they face mortality. The simplicity and fantastical elements of the story would be perfectly convincing as a rendition of an existing myth, but the story is completely Dudok de Wit’s invention.

The three human figures are drawn very simply and look like they were rotoscoped, though I can find no confirmation of that online. The depiction of the natural landscape and the creatures that inhabit it are, however, stunningly beautiful. Without attempting a photorealistic look, Dudok de Wit’s team have captured the look and movement of sunlit seawater, the rhythmic rustling of leaves, and even the differences in color between the exposed and the submerged surfaces of woolsack blocks of granite at the ocean’s edge. It is almost as if they have managed to rotoscope all of nature.

The classic films by the main directors at Studio Ghibli are more elaborate and complex than The Red Turtle, but the new film suggests that the studio will maintain its high standards in its future productions.

The Red Turtle was bought by Sony Pictures Classics and is scheduled for a mid-December American release.

Window Horses (The Poetic Persian Epiphany of Rosie Ming)

While The Red Turtle is a high-profile animated film, Window Horses originated as an Indiegogo project. Its success in that campaign led Sandra Oh to back the film, signing signed on as a producer and providing the voice of the film’s heroine. The project gained additional support, including by the National Film Board of Canada. Still, it is likely to remain largely a festival item (it premiered at the Annecy International Animation Film Festival), with only a limited theatrical release in Canada early next year. (Information on that release is not yet available online, but news will presumably be posted on the film’s website.) It exhibits a lively imagination and stylistic sophistication that deserve a wider audience, which with luck it will achieve via streaming.

The story centers on Rosie Ming. With her Chinese mother dead and her father having apparently abandoned his family to return to Iran, she lives in Vancouver with her maternal grandparents. A self-published book of her verses leads to an invitation to a poetry festival in Shiraz. Donning a full chador in the hopes of fitting in, she finds herself surrounded by women wearing simple scarves and vibrant clothing.

The animation itself is colorful, with stylized faces that are vaguely reminiscent of Picasso (as in the tour-bus scene, above). Rosie stands out in her utter simplicity, rendered as a black-clothed stick figure with a round, white face sketched in only by eyes and, when she speaks, a mouth. Recitations of poems are accompanied by scenes of animation is a variety of styles, contributed by such animators as Kevin Langdale, Janet Perlman, Bahram Javaheri, and Jody Kramer.

Overall, it is an engaging and entertaining film, showing how much an independent filmmaker can do with limited means. In that it reminds me of Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues.

Films that have particularly impressed us so far include Pablo Larrain’s Neruda (playing again on October 9), Cristian Mungui’s Graduation (playing again October 5 and 11), and above all Terence Davies’ A Quiet Passion (playing again on October 9). We’ll be blogging about these and others over the next several days.

The Rehearsal (2016).

Around the world in a multiplex: First dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here–

My title exaggerates. There are other venues for the Vancouver International Film Festival besides the Empire Granville multiplex. There is the Pacific Cinematheque, often used for more avant-garde items; the Vancity Theatre, which screens art films and hosts industry events year-round; and the gorgeous old picture palace, the Vogue, a multiple-use venue that hosts both big screenings and gala events. But frequently we find ourselves wandering for a whole day among the Granville’s seven screens, circling the globe cinematically.

The Middle East

Four years ago we blogged about Captain Abu Raed (2007), the first Jordanian feature film in decades. This year there is The Last Friday (2011,  Yahya Alabdallah), and by now the fact of a Jordanian film appearing at festivals is no longer notable. Production has now been systematized. The Last Friday was financed (for around $100,000) by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan’s Educational Feature Film Program.

Yahya Alabdallah), and by now the fact of a Jordanian film appearing at festivals is no longer notable. Production has now been systematized. The Last Friday was financed (for around $100,000) by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan’s Educational Feature Film Program.

The basic plotline is simple, with protagonist Youssef, a handsome, hard-working middle-aged man, divorced and reduced to driving a taxi prone to breakdowns, struggling to earn money for a serious operation. The cinematography was done using a Red One camera, and the resulting images are impressive. (Alabdallah often resorts, with good effect, to what David has termed planimetric compositions, those shot directly toward a flat background.) There is little dialogue, and Youssef’s struggles are conveyed by small details, visual and aural. The fact that he has tampered with his apartment block’s switch boxes to steal electricity is established early on, but by-play with the fuses he has transferred or hidden becomes an unnecessary but entertaining motif.

Perhaps the “educational” part of the film comes from Youssef’s son, a teenage wastrel who hangs out at his father’s apartment. It eventually comes out that he has stopped going to school, and Youssef has the additional burden of confronting his ex-wife to thrash out a method for dealing with their errant son.

The Last Friday treads that risky line so many independent filmmakers on small budgets take, singling out a character with a problem and showing him or her doggedly dealing with it. It takes a sure touch and an interesting character to make this work, and Alabdallah manages both, helped by Ali Suliman’s performance in the lead role.

So far undoubtedly the biggest unexpected gem this year has been the Iranian family melodrama/thriller A Respectable Family (2012). The film is the first fiction feature by documentarist Massoud Bakhshi; it was shown in the Directors’ Fortnight series at Cannes and gained generally favorable reviews.

The plot concerns Arash, a professor who has lived in Paris for decades and, as a guest post at the university in his hometown of Shiraz winds down, seeks in vain for the return of his passport to allow him to return home. At the same time, a lawyer informs him and his mother that a sizable sum of money has been left to them by his estranged, abusive father. The family drama that plays out depends for effect on an extraordinarily complex and tight script with numerous abrupt turns and surprises that keep the audience as busy as in any recent Hollywood thriller. In particular, Bakhshi’s use of switches in point of view and flashbacks to the period of Arash’s youth are masterful.

Here I pass along the same advice I have given friends here at the festival in recommending the film: don’t read reviews or program notes about this film before seeing it. Everything I have read about the film gives away key pieces of information that should be kept secret.

The tone of the film, with its implicit but obvious criticism of the Iran-Iraq war and the regime that fostered it, plus the ending’s evident support for student demonstrators, make it amazing that the film could be made within Iran. It apparently has not been released within its home country and most likely won’t be. Yet the Iranian press reported calmly on its favorable reception at Cannes, as the press there usually does when national films gain prestige abroad. A story in the Teheran Times remarked: “It was a great surprise that non-Iranian filmgoers were able to relate to the Sacred Defense (1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war) and the concept of martyrdom, which are themes of the film, Mohammad Afarideh [the film’s producer] told the Persian service of the Mehr New Agency.” Afarideh added, “The film has an Iranian storyline, but the structure Bakhshi has chosen for the dialogue helps attract foreign audiences as well.”

Many in Iran and elsewhere were also surprised that A Separation could connect with western audiences in the way it did. It’s a pity that A Respectable Family is unlikely to gain such a widespread audience, but it is worth seeking out. It plays once more here in Vancouver, on October 3 at 6:45 pm in the Empire Granville 2.

Latin America

Una noche (2012) is listed in the program as a Cuban/UK/USA co-production. The Cuban contribution comes primarily from the setting and the cast–and the cooperation of the government. (Certainly it makes setting out to try and escape to the USA an unattractive prospect.) It was entirely shot in Havana and environs, and three young first-time actors play the principal roles. The director is Lucy Mulloy, making her feature debut. It is otherwise largely New York based, having been at least partially supported by the Independent Filmmaker project in its “Narrative Independent Filmmaker Lab,” which funds films with budgets of under a million dollars. Post-production seems mainly to have been done at the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU.

Perhaps as a result of such mixed origins, Una noche manages to create a strong, Hollywood-style plot with plenty of local color. The opening shows a blonde tourist in a car, but the heroine’s voice declares that this will not be this girl’s story but her own. Quick but effective characterization sets up the close relationship between twin brother and sister. They’re poor kids from the barrio scratching a living, with Lila working as a dance-hall girl and Elio serving as a cook. Yet we are away from Lila for long stretches, becoming aware, as she is not, that Elio is gay and has a crush a fellow cook. But Raul is an obviously straight young thug, and he has talked Elio into making an attempt to cross to the USA on a raft.

Their preparations, gathering the materials and supplies they need, take us through the poverty-stricken neighborhoods, with Elio’s shiftless friends catcalling at girls and joyriding on their bikes by clinging to buses. Raul visits a dealer to buy medicine for his AIDS-stricken mother, a gaunt former beauty still turning tricks to support herself.

The action escalates as Raul accidentally injures a tourist and Lila discovers that Elio is planning to leave her and go with Raul. Mulloy deliberately downplays the ending, flashing a dedication on the screen to give us the impression that the film is over. Almost as an afterthought mixed in with the beginning of the credits, she presents brief shots showing us of the fates of the characters, filmed from a distance and without Lila’s voiceover. The Variety reviewer found the ending abrupt and “somewhat inadequately foreshadowed,” yet it seemed appropriate to me, and indeed was one of the most original touches in the film.

The North American rights to Una Noche were picked up earlier this year by Sundance Selects after the film proved a hit at the Tribeca Film Festival, winning Best New Narrative Director, Best Cinematography, and Best Actors (shared between its two male leads). Ironically, two of the young lead actors used the Tribeca festival as an occasion to request asylum in the USA.

The Antipodes

There is something comforting about the fact that, after all the success of the Lord of the Rings trilogy and the prospect of a series of Avatar films  being made there into the indefinite future, the New Zealand Film Commission is still funding the same sorts of low-budget genre movies that were made before the country became Middle-earth and Pandora. Robert Sarkies, veteran Kiwi director, has followed up his gripping, headline-based thriller Out of the Blue (20o6) with a return to Scarfies (1999) territory, albeit on a more grotesque level.

being made there into the indefinite future, the New Zealand Film Commission is still funding the same sorts of low-budget genre movies that were made before the country became Middle-earth and Pandora. Robert Sarkies, veteran Kiwi director, has followed up his gripping, headline-based thriller Out of the Blue (20o6) with a return to Scarfies (1999) territory, albeit on a more grotesque level.

Two Little Boys (2012) is based on the old getting-rid-of-an-incriminating-corpse premise, with wimpy Nige (Bret Mackenzie, left) accidentally killing a Scandinavian sports star with his car. Despite a recent quarrel, Deano (Hamish Blake), his best friend from childhood, agrees to help him out and hatches more and more devious and grisly methods for disposing of the body–and later of Nige’s roommate, pudgy, clueless Maori roommate Gav, who adds a touch of sweetness with his persistent obliviousness to the pair’s fiendish doings.

It’s a feather-weight film, but one with many funny moments. It also shows off some parts of New Zealand seldom used in films, starting off in the southernmost and westernmost city, Invercargill, and the bleakly beautiful Catlins, on the southeast coast.

Europe

From the ridiculous to the sublime. Journal de France (2012) presents a sort of professional autobiography of the great French photographer and filmmaker Raymond Depardon. The framing situation is a journey through France that Depardon takes (supposedly alone, though there is someone there to film him), photographing landscapes and villages with his big view camera (bottom). There’s a charmingly chatty scene of him photographing four aged men who had posed for him in the same spot earlier (top).

Interspersed is footage from throughout Depardon’s career. This is presented in voiceover by co-director Claudine Nougaret, the filmmaker’s partner in private life and his long-time sound recordist. Much of this footage didn’t make it into the finished documentaries, including practice shots from when Depardon was learning the trade and amazing footage of many of the major events of the late twentieth century. Depardon travelled widely, often going into war-torn areas of Africa, such as Biafra in the late 1960s. His candid footage of people in the streets of Prague during its invasion by Russian tanks in 1968 is astonishing. Also memorable is a shot of Nelson Mandela quietly sitting in a chair. Depardon asked him to sit for a minute without speaking. Without a watch, Mandela timed it to the second. He learned the trick while in prison.

One comes away with a sense of not just a man with a keen eye and a great deal of patience. Depardon’s bravery and political conscience allowed him to leave behind a legacy of images with an immediacy that brings half-forgotten historical moments to vivid life.

Now I’m off to the Granville again, to see a Japanese film and then a South Korea one. David will blog about these in a future dispatch.