Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Hark! How Harold’s angels sing (a repost)

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1094 entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed.

Movie fans may want something a little offbeat relax with at home, so we thought that in these turbulent times, classic comedy would be welcome. We’ve picked a 2017 entry to revive (and slightly revise): “The Boy’s Life,” devoted to Harold Lloyd. (He certainly had the holiday spirit; he’s said to have kept a Christmas tree up, complete with presents, all year round.) We still think he rewards our interest, and families and cinephiles ought to find his films fun. This entry introduces Girl Shy, still running on The Criterion Channel, with DB’s discussion included there. The blog entry refers to other Lloyd movies, all of which are on the Channel and some of which are also available on the TCM wing of Max (but not, alas, Girl Shy).

Warm holiday wishes from the two of us!

DB here:

On 9 September 1917, film history changed for the better. That was when we got the eyeglasses.

Their circular, horn-rimmed frames stood out as wire rims would not; besides, horn rims had become fashionable for young people. These specs held no lenses, but so much the better. Reflections from studio lights would have hidden the eyes of the winsome, earnest, clueless young man usually called the Boy.

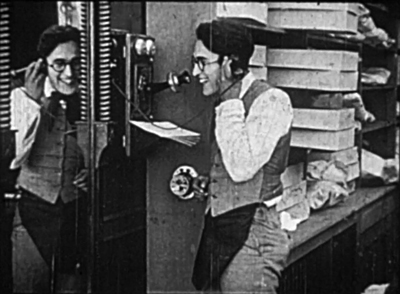

In Over the Fence, the film introducing him, he’s already amiable, a little vacuous but delighted to be talking to his girl on the phone and watching himself doing it.

Harold Lloyd had already featured in some sixty-five short comedies from 1915, playing characters called Willie Work and Lonesome Luke. Even after introducing the Boy, Lloyd continued with a few Lukes before phasing out this sad sack. No one expected that in a few years the glasses character would become world famous. Lloyd’s films were more lucrative in aggregate than those of any other silent comedian, and he became one of the central figures in Hollywood.

When our comrades at Criterion announced their plan for a centenary Lloyd celebration this month on FilmStruck, I suggested we devote an installment of our series to one of the films. Kristin and I have been Lloyd fans for decades. Fans and collectors kept his work alive. Kevin Brownlow had to remind people with his Lloyd documentary, The Third Genius (1989), that, well, Lloyd was a genius. The more you get to know his work, the better it looks, and the less plausible seem many of the clichés that have clustered around it.

One of the very best films to get to know is Girl Shy (1924). That’s the one analyzed in the latest Observations on Film Art episode on the Criterion Channel.

Man into Boy

For decades after sound came in, American silent comedies dropped mostly out of sight. Some 16mm copies were available in cut-down rental versions, and a few were circulated by the Museum of Modern Art Film Library. (Of Lloyd’s work, that included only The Freshman of 1925.) The MoMA canon became the canon. In the 1970s, thanks largely to piracy, the films of Keaton were added, and still later we came to recognize Charley Chase, Max Davidson, and other talents.

Throughout these years Lloyd’s films were almost invisible because he controlled the rights to them and limited their circulation. Kept in vaults in his rococo estate Greenacres, they would not reemerge until the 1960s, in cut TV versions distributed by Time-Life. Until fairly recently, most critics relied on memory of the films and the received image of the Boy dangling helplessly from the clock face.

Most of the sixty-one shorts featuring the Boy languish in archives, and some were lost in a fire on the Lloyd estate. But several two-reelers are readily available, as are all the longer films. What we have gives the lie to most clichés about this filmmaker.

Take the most persistent one. Socially conscious critics of the 1930s saw Lloyd’s work as naively reflecting the go-go 1920s. The Boy’s resolutely middle-class aspirations made him a crass avatar of complacency before the Crash. Chaplin seemed to stick up for the little guy, but Lloyd seemed to celebrate the striver; he compared himself to Tom Sawyer. It was all very neat. The Boy’s climb up the skyscraper in Safety Last could symbolize the heedless ambition of the white-collar worker, while the his efforts to fit in at college in The Freshman suggest desperate American conformity.

Those interpretations played down the fact that just as often Lloyd played hayseeds humiliated by city folk and con artists. In Girl Shy, the city slicker who wants the girl is a weasel, and Harold has to rescue her. Here, as often, the film is largely a procession of social humiliations. Lloyd, a predecessor of cringe comedy, in turn provided a model of embarrassment for Ozu’s silent films. Those films often feature students wearing the Boy’s glasses (below, Days of Youth, 1929). This isn’t mere imitation or homage; the glasses became a Japanese fashion item, called roydo, named after Lloyd. (Below, a photo from a student ski trip in the 1930s.)

More edgily, Lloyd also played foppish idlers, louche one-percenters who glide obliviously through the lower orders and need to learn humility. The original title of For Heaven’s Sake (1926) was to be The Man with a Mansion and the Miss with a Mission, a phrase retained in an intertitle. Here as elsewhere, the coddled Boy learns to help his social inferiors. If you’re after class-based critique, Lloyd films come out pretty well.

Likewise, there were the complaints that Lloyd’s comedy was mechanical. Chaplin was the poet and dancer. Keaton, in both concept and execution, showed himself a geometer, the dogged engineer of monumental effects more awe-inspiring than hilarious. Though granting that Lloyd, foot for foot, yielded more laughs than any of his peers, critics worried that he was only merely funny, a relentless gag machine. Here is James Agee, in one of the subtlest appreciations of silent cinema ever written:

If great comedy must involve something beyond laughter, Lloyd was not a great comedian.

But immediately, as an honest man, Agee must add:

If plain laughter is any criterion—and it is a healthy counterbalance to the other—few people have equaled him, and nobody has ever beaten him.

Still, Agee admits that Lloyd’s films pass beyond laughter in one respect. They offer harrowing suspense. What his audiences called “thrill comedy” remains chilling today. His antics on skyscraper ledges and girders still induce vertigo, and his car chases risk catastrophe on a scale that would worry Jackie Chan. Agee seems to grant that inducing shrieks as well as guffaws is no small accomplishment.

If Agee could have reviewed all the feature films, though, maybe his judgment wouldn’t have been so absolute. For example, Lloyd’s features take us beyond laughter in serious ways—into regions of vulnerability and inadequacy. The Boy is typically given a fault: cowardice (Grandma’s Boy), self-absorption (as hypochondria in Why Worry? and as self-indulgence in For Heaven’s Sake), lack of confidence (The Kid Brother), neurotic extroversion (The Freshman). In several films, the seriousness undercuts the comedy.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold can’t drive away the tramp, but Granny can do it easily, with some swipes of her broom. Our laughter is cut short when, in the space of a cut, as she calmly returns to the porch, we see the Boy slumped over, his head in his hands.

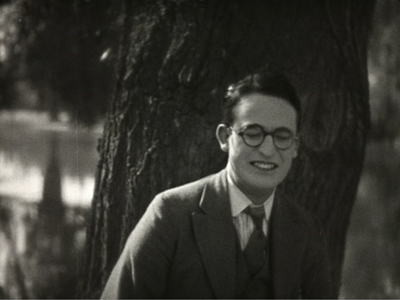

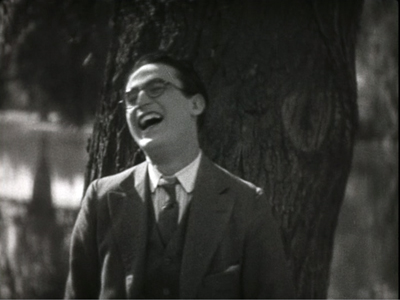

Soon he will admit that he’s a coward. Lloyd films switch their tone on a dime, shifting between comedy and drama breathlessly. In Girl Shy, the Boy not only dumps the girl he loves but does so by cruelly laughing at her trust in him. (Agee: “He had an expertly expressive body and even more expressive teeth.”) Wobbling and shifting his weight, Harold breaks the laugh with a gulp before carrying on his bluff.

Nothing in Keaton or Chaplin makes us as ashamed of our hero as we are right now. Soon he will do something worse.

This passage reminds us that Lloyd worked his face for all it was worth. Keaton had more expressions than he’s usually credited with (bewilderment, concentration, doggedness); it’s just that he doesn’t smile. Chaplin inherited the white-face clown tradition and often favored deadpan. He limited his facial reactions to squiggles and flashes, often no more than a skew of the mouth or hauteur in the brows, with an occasional embarrassed giggle. With Chaplin, the body expresses nearly everything, as befits an aesthetic predicated on the long shot.

But Lloyd, relying on medium shots, performs as a dramatic actor, with a wide repertory of expressions. Agee refers to his “thesaurus of smiles,” but he had other resources, as this Girl Shy scene attests. His producer Hal Roach is said to have remarked: “Harold Lloyd was not a comedian. But he was the finest actor to play a comedian that I ever saw.”

Another nuance: Comic laughter comes in many varieties. Like Keaton, Lloyd celebrates winning through tenacity and resilience. If we gasp at the geometrical audacity of Keaton’s humor, we’re buoyed by Harold’s righteous settling of accounts. It’s reported that audiences actually leaped up and cheered at the climaxes, when bullies and rascals were punished at delectable length. These are comedies of comeuppance and payback, outcomes universally enjoyed and still much in demand today.

Point the last: Neatness of construction. Chaplin’s films are lovably episodic; I still marvel that films that took so long to make are so loosely put together. Keaton by contrast is a metronome-and-protractor director, aiming to make every shot and sequence and reel sit in meticulous order. No one but he could have conceived the marvel of symmetry that is The General, or, on a lesser scale, Our Hospitality and Neighbors.

Lloyd’s films are no less finely put together, as many recognized at the time. A Film Daily review of The Kid Brother (1927) noted: “Lloyd and his gag-men again have devised a corking set of comedy situations that fit consistently into a well-joined plot and laughs keep building from little chuckles to hilarious roars.” Orson Welles praised “the construction of Safety Last, for instance. As a piece of comic architecture, it’s impeccable. Feydeau never topped it for sheer construction.”

To get a little more specific, I think that Lloyd’s model was the well-made dramatic film, the tight classical plot. This is the argument I make in the Girl Shy installment. I try to show that in this, his first film as an independent producer, Lloyd applied the emerging model of Hollywood narrative to feature-length physical comedy. Fairbanks had moved in this direction, and Lubitsch would achieve something similar with social comedy in The Marriage Circle (1924) and the masterpiece that is Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

Lloyd was a pioneer in showing how everything that worked for serious dramaturgy could work for comedy too. Girl Shy gives us a goal-oriented protagonist who has a serious flaw. Going beyond the figures of slapstick, we get access to his psychological yearnings and frustrations. His loneliness and fear of women fuel overwrought fantasies of domination. The Boy is caught up in the characteristic Hollywood double plot, involving love and career—two lines of action that usually block and deflect one another.

This linear action is deepened by a series of motifs. They’re simple in themselves (a stammer, a Cracker Jack box, a dog biscuit box), but they’re worked out with a pictorial and dramatic intricacy that’s rare at the time. And it’s all topped off by a two-reel chase that is simply one of the greatest ever put on the screen. At a time when every superhero blockbuster ends with a big action sequence, it’s worth seeing one that’s both graceful and hilarious, and it owes nothing to special effects.

Girl Shy shows how rewardingly complex silent Hollywood storytelling could be. It reveals Lloyd as a master craftsman of cinematic resources—dramatic, pictorial, emotional. He saw how to make a movie that would be engrossing even without the gags. The comedy deepens a powerful dramatic premise that moves forward with an organic, not mechanical, energy, and it’s developed in funny or poignant detail at every instant.

Filling the format

In the arts, form often follows format. The fourteen-line sonnet, the tondo painting, the twenty-two-minute sitcom, the nine-panel comic-book page: all provide the artist with a set framework within which to create. When Lloyd started out, film reels in the US were standardized at 1000 feet, which typically ran between twelve and fifteen minutes, depending on projection speed. Short films, particularly comedies, were either one or two reels, while features–dramas, mostly–ran four, five, or more.

The task of the filmmaker was to build a story that would fit the format. The temptation was padding. Griffith, for instance, often filled out his shorts with “goings and comings,” shots of characters leaving one place and making their way to another, sometimes across several shots. But once padding was inserted, filmmakers could make it engaging. Griffith did this by embedding the goings and comings in suspenseful situations, so that the travel shots served as dramatic delays. Mack Sennett needed scenes to lead up to a big chase (the “rally”), but those scenes could themselves have a linear logic, as with romantic rivalry or street quarrels.

Lloyd became very sensitive to film length. He knew that his initial popularity depended on the fact that Pathé and producer Hal Roach spit out a Lonesome Luke every week or two; he saturated the market. Even after Luke appeared in two-reelers, Lloyd wanted his new character, the Boy, to start in one-reelers. He recalled telling Roach, in sentences as breathless as the pace of a one-reeler:

Now, I’m getting started in a new character and you want people to get used to the character, you want them to see the character; and besides, if you make a poor, or mediocre, or moderately good, or even a bad picture in a two-reeler, it’ll kind of tend to sour the people on you because they won’t see another one for a month. But if I make one-reelers, we’ll get one out every week, so if a couple of them are not so good, and the third one is, it will cover up the other two, and besides it will keep you in front of the public.

As a result, Lloyd spent two years turning out an astonishing eighty-two one-reelers. Not until Bumping into Broadway (2 November 1919) did he launch a two-reeler featuring the Boy.

There’s evidence that Lloyd’s awareness of the niceties of running times went beyond a concern for building the brand. He understood that form and format had to mesh. His early one-reelers relied largely on the standard episodic knockabout. We’re given a defined situation, such as a modernized hotel (The City Slicker, 1918), a western saloon (Two-Gun Gussie, 1918), or a vaudeville theatre (Ring Up the Curtain, 1919). In this situation, the characters quarrel, pull pranks on one another, engage in fistfights, kick each other in the pants, and usually wind up in a chase. A string of gags might emerge, as when a stray snake terrifies the theatre troupe in Ring Up the Curtain, but the gag is quickly exhausted, and we go on to the next bit.

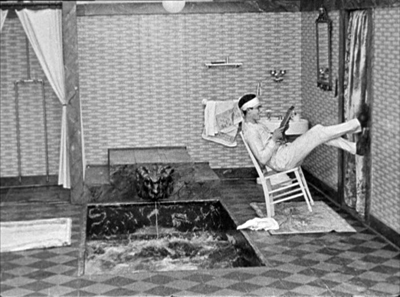

Once Lloyd settled on two-reelers, he built them up more carefully. He scaled, we might say, his plots and gags to a fairly tight, logical development in the fuller format. Part of that development involves what we might call nested gags. In Captain Kidd’s Kids (1920), the first part (roughly one reel) sets up Harold as a playboy recovering from a bachelor party. In his elaborate bathroom, he tips back his chair, leading us to expect him to fall in. But no: instead his butler, Snub Pollard, dumps ice in the pool.

There follows a string of shaving gags here and in the next room. Early in this series, Harold drips shaving cream in his morning tea; but after other gags he comes to drink it and finds it foul-tasting. Then he returns to the bathroom, tips back the chair again, with results we’d expected several minutes before.

Now we get some elaborate efforts to rescue Snub. The gags are simple, but by setting up one and then moving to set up and pay off others before returning to the first, Lloyd and his team avoid the start-stop-restart pattern than we find in many one-reelers.

The real plot action, of course, doesn’t get going until the second reel of Captain Kidd’s Kids, but Lloyd has provided some lively padding to start. Now or Never (1921) shows the same gag-braiding, with the recurring appearance of two drunks on the train ride that constitutes the bulk of the film.

Lloyd moved toward longer films cautiously—first to three reels, then four (A Sailor-Made Man, 1921), then five (Grandma’s Boy and Dr. Jack, 1922). He always said that most grew organically, beginning as two-reelers and then expanding when the story premises and gag sequences developed. To keep things in proportion, he tested the results on preview audiences, then reshot and recut his footage. The preview responses to one three-reeler, I Do (1921), convinced him to lop off the entire first reel. Although he had increased confidence in his ability to scale up, when he signed a new contract with Pathé in early 1922 he insisted that the company publish a notice to exhibitors declaring that film length would be

strictly governed by the character and quality of the material evolved in the production development of each subject—which means that the Lloyd standard of excellence is to be maintained first of all; a given story that turns out to be adequately filmed in two reels will be confined to two reels, and so released. This is a principle cherished by Lloyd himself.

Lloyd could be so confident because even his shorter releases were becoming the top-billed item on programs across the country. He was, in effect, returning the idea of “feature” to its original meaning—not simply a long film, but rather a movie that could be “featured” in publicity. He was also announcing his unusual concern for tight form.

Comic architecture

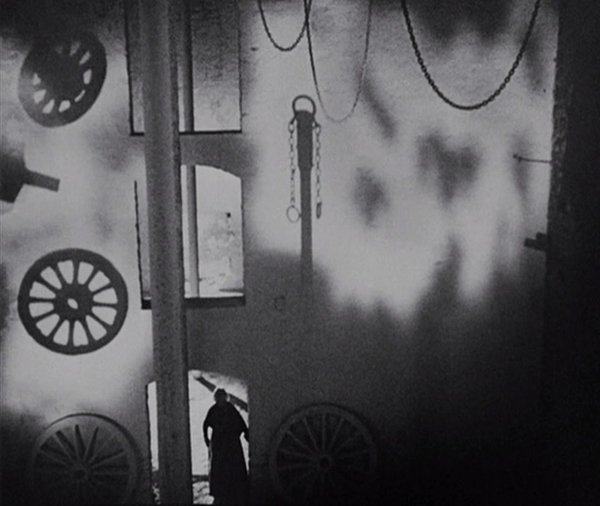

Grandma’s Boy (1922).

Lloyd moved to features in synchronization with his peers. Keaton was the first, with The Saphead (September 1920), though it’s less a comedy than a light drama; and Keaton returned to making two-reelers for three years. The Round-Up (October 1920) gave Fatty Arbuckle a comic role in what was basically a serious drama. Arbuckle starred in The Life of the Party (December 1920), another light drama with almost no physical comedy. Chaplin’s The Kid (February 1921), at a bit more than five reels, might be considered the first slapstick feature since the one-off Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914, six reels). The émigré Max Linder got into the act with two 1921 features, Seven Years’ Bad Luck (May 1921) and Be My Wife (December).

It might seem that Lloyd was a bit late with the four-reel Sailor-Made Man (December 1921). But that film capped his most extraordinary year to date, with four earlier films released in spring, summer, and fall. Along with six two-reelers released in 1920, Lloyd was now a major comedy star, and the Boy could carry a longer story.

But how to do that? His peers explored some options. In Arbuckle’s two features, it’s his physical presence that matters, not consistency of character; in one he’s a genial sheriff, in the other a lawyer inclined toward crookedness. Chaplin retained the Tramp persona in The Kid, but the film is a rather episodic affair. Once the main plot is resolved, a reel pads out its length with a dream sequence set in heaven. The Linder films are lively but digressive, with plots propelled by casual pranks and lovers’ misunderstandings.

By contrast, Lloyd’s features moved toward tight construction. Despite his claim that his films just grew longer accidentally, they were shaped in ways that make them seem through-composed. His comedy sequences are deftly prolonged, building and topping themselves with great speed. Gags are embedded and interwoven in ways that yield surprises, and motifs set up early in the film pay off later. We may have forgotten about them, but Lloyd hasn’t.

Lloyd’s obsession with overall form can be seen in his use of the “Lafograf,” a kind of EKG of viewers’ response at previews. Coders sat in the audience with pencil, paper, and stop watches to note every bit of amusement, from a titter to a screech. Once graphed, the entire movie displayed laughs big and small throughout, with most of the big ones spiking in the last reel.

A powerful demonstration of Lloyd’s skill came in his first five-reeler, Grandma’s Boy (1922). Chaplin called it “one of the best constructed screenplays I have ever seen on the screen.” Lloyd began it as a two-reeler, but after expansion it had become more drama than comedy. Roach urged him to add more gags, and the result is a remarkable balance between humor and pathos.

That mixture is given from the start in a prologue showing a baby Harold, glasses and all, bullied by another baby. Then the Boy as a boy is picked on and made to put a chip on his shoulder.

This last bit will pay off fifty minutes later. The rival, the little bully grown up, taunts Harold, not knowing Harold has captured the prowling tramp and proven his courage.

The upshot is a fight that knocks the stuffing out of the Bully. In the course of that fight, another moment calls up a contrast with an earlier scene. The day before, the Bully has pitched Harold into the well; now, after the Rival tries a foul blow, Harold administers payback.

These distant echoes can be very satisfying.

The organization of gags is likewise remarkably sustained. Walking home from his well dunking, Harold finds that his one suit has shrunk grotesquely. But the Girl has invited Harold to her home for an evening, so he needs another suit. Granny digs out his Grandpa’s suit, 1862 vintage. (The peddler said it was unique.) It still has mothballs in it. Granny also finds there’s no shoe polish, so she uses goose grease instead. These bits become the basis of a steadily building gag situation in the Girl’s parlor.

But not right away. First Harold arrives and discovers that his vintage outfit is matched by that of the butler. Another echo, when he mutters: “That peddler lied to Granny!” He sits to listen to the Girl play the piano, and gets his finger caught in a vase. Only now does one of the earlier gag setups start to pay off. A cat comes to lick his tastily greased shoes.

The grown-up Bully was introduced throwing a stick at a cat, but Harold is more gentle. He nudges the Girl’s cat away, but soon a troupe of cats enters to converge at his feet.

He has to dispose of them without the Girl’s noticing. Finally, when the couple move to the settee, the cats reconnoiter and the gag sequence pays off: Harold uses a statuette of a bulldog to scare them away.

Cozying up to the Girl, Harold ought to be in clover, but now she smells something—his suit. Investigating, he finds mothballs that he and Granny failed to remove. I’ll spare you more description. You can watch what happens next, including a new confrontation with the Rival. And again, Harold gives us an unforgettable suite of facial expressions.

Lloyd’s pacing allows just enough time for us to anticipate what might happen at each turn of events. Structurally, while Lloyd is developing and paying off the IOU of the mothballs, he wedges in a fresh setup, that of the neighbor kid’s requesting some gasoline. That becomes the topper for the mothball series, as the dog statuette topped the cat gags. This sort of braiding of gags, weaving the setup of one gag into the development of another, shows how a feature can be built out of quasi-melodic lines, like a song.

Even more important is the presentation of the protagonist. Lloyd gives his hero what modern screenwriters call a character arc. In the early 1920s Lloyd began to distinguish between gag pictures and “character pictures,” in which the story line depends on our concern for the protagonist.

In his short films, Harold had an established image, but his characterization varied a lot. Sometimes he was a good-natured everyman, but he could also be a scrapper, a hustler, or a ne’er-do-well. And his romantic relations with Bebe Daniels were wonderfully flirtatious; in one she helps him count bills by licking his thumb. In the features, Harold was given a more definite character, one with a pronounced fault. He was often insecure, awkward, and oblivious, qualities that led critics to call him a boob. The insult is referenced in Girl Shy, when his book gets mocked as The Boob’s Diary. Correspondingly, the romance plotline of his films became much more fraught.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold’s fault is cowardice, and he must keep the Girl from finding it out. His impulse is to hide from the world, but Granny inspires him with the tale of how his Grandpa overcame his fears and helped the southern army win the war. He did it, she says, thanks to a Zuñi charm given him by an old woman.

Now Grandma gives Harold the charm, and his faith in it enables him to capture the murderous thief. In a double climax, Harold, still clinging to the charm, is able to beat the Bully in a drag-out fistfight.

Of course the action is packed with delays, detours, and surprises. The capture of the thief is a superb flow of gags, from Harold braving the tramp’s hideout to a long chase, in which the talisman does duty as a pistol barrel. And the fight with the Bully gets expanded when Harold loses the charm and turns suddenly meek. After the fight, the topper comes when Granny reveals the real source of the charm’s power. Harold comes to understand that he has inherent reserves of courage.

Nicholas Kazan once observed: “You want every character to learn something. . . . Hollywood is sustained on the illusion that human beings are capable of change.” This principle of construction goes very far back, and it became the basis of Lloyd’s feature plots. We get not just a change of fortune (and so a happy ending) but a change in personality (and so a happier one).

From Grandma’s Boy onward, Lloyd’s features display disciplined, inventive construction–at the macro-level of plot and at the mid-range of gag sequences, down to precise shot-by-shot articulation of the action. Here’s a moment when Grandpa (he wears glasses too) sees, reflected in an inkstand lid, a Union officer preparing to clobber him.

Since the Bully is reincarnated in the Union officer Harold outwits, this flashback quietly prefigures the Boy’s victory over the Bully at the climax.

In my Criterion Channel presentation, Girl Shy serves as another example of how Lloyd brought classical construction to comedy. I could as easily have picked another superb item, The Kid Brother. Maybe next year?

It seems likely that Lloyd’s work became a model. Keaton’s trimly carpentered second feature Our Hospitality (1923) is in the same vein. And Chaplin, after he praised Grandma’s Boy, went on to declare: “The boy has a fine understanding of light and shape, and that picture has given me a real artistic thrill and stimulated me to go ahead.” Lloyd and the Boy, glasses and all, remade Hollywood comedy in important ways, and in the process they gave us wonderfully exuberant films.

Thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, and their team at Criterion. Thanks as well to Jared Case of George Eastman House for information about their print of Never Weaken.

Lloyd’s autobiography, An American Comedy, was timed to the 1928 release of Speedy, and it’s full of detail about gag structure and the production of his films. At one point he transfers our old friend, the distinction between suspense and surprise, to comedy. The book includes Frances Marion’s memorable line, “Harold, you’ve got to lose your pants.” Coauthored by Wesley Stout, An American Comedy was reprinted in a sturdy Dover edition with a 1966 interview and a cliché-challenging introduction by Richard Griffith.

Lloyd has been lucky in his admirers. Richard Schickel’s Harold Lloyd: The Shape of Laughter (New York Graphic Society, 1974) yields a finely sustained appreciation of his art. Adam Reilly’s Harold Lloyd: The King of Daredevil Comedy (Collier, 1977) is a vast compendium of biography, plot synopses, and visual documentation. Tom Dardis’s Harold Lloyd: The Man on the Clock (Viking, 1973) is a careful biography that situates Lloyd’s career in the development of the film industry. Donald W. McCaffrey offers a comparative study of plot structure in Three Classic Silent Screen Comedies Starring Harold Lloyd (Associated University Presses, 1976).

Most comprehensive of all is the remarkable Harold Lloyd Encyclopedia (McFarland, 2004) by Annette d’Agostino Lloyd (no relation). All the films are synopsized with credits and items from trade papers. Her Harold Lloyd: Magic in a Pair of Horn-Rimmed Glasses (BearManor, 2009) is full of fan enthusiasm, shrewd observation, and information I couldn’t find elsewhere. (She even checked Lloyd’s FBI file.) My Welles quotation above comes from this book, p. 167, as does Harold’s explanation of starting the Boy in one-reelers (pp. 85-86). The indefatigable d’Agostino Lloyd earlier produced Harold Lloyd: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1994).

The Agee essay is of course “Comedy’s Greatest Era” from 1949. My quotations come from James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland, vol. 5 in The Works of James Agee (University of Tennessee Press, 2017), p. 883. My Chaplin quote comes from Dardis’s biography, page 112. The quotation from Nicholas Kazan is in Jurgen Wolff and Kerry Cox, Top Secrets: Screenwriting (Lone Eagle, 1993), 134. Lloyd’s movie-measuring scheme is explained in P. A. Thomajin, “The Lafograf,” American Cinematographer (April 1928), 36-38, as applied to The Kid Brother, online here. The graph for Speedy is reproduced in Reilly’s Harold Lloyd, pp. 106-107.

A very pretty collection of early Lloyds is on Vimeo from Random Media. The standard DVD assemblage of features and shorts is the multiple-disc Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection. Several of these films are streaming on the Criterion Channel. Unfortunately, the version of Never Weaken (1921) available in these collections is a 1925 re-edit of the original three-reeler. The full version survives, however, and is available, in a so-so video, here. Criterion also offers an excellent Blu-ray disc of Speedy (1928), with solid extras, including an essay by Phillip Lopate and a visual essay on the film’s New York locations by Bruce Goldstein.

I analyze Ozu’s strong debt to Lloyd in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, pp. 152-159.

For the trivia fanatics: I think Harold’s manuscript in Girl Shy is mocking a sensational movie of a few years before, Men Who Have Made Love to Me. This film, written by Mary MacLane, an early feminist and scandal-rouser, was based on her memoirs. The movie is laid out in six parts, each devoted to the seduction method employed by one of her suitors. The film is lost, but it seems likely to have been the target of ridicule in the Lloyd picture.

Girl Shy (1924).

DIE HARD revived: An entry revisited

Die Hard (1988).

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1094 entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed.

Today’s revival responds to the return of Die Hard to theater screens in time for Christmas. Since our original posting in 2019 (“Not just a Christmas movie”), this supreme action picture has further cemented its reputation as a yuletide favorite (although it was originally released in July). Happy holidays from the Nakatomi Corporation!

DB here:

It’s been quite a fall season for UW–Madison film culture. There were visits from avant-garde legend Larry Gottheim, New York Times co-chief film critic Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston (Senior VP of Mastering at Disney), and Julia Reichert, whose American Factory is now routinely turning up on ten-best lists. The semester’s first screening at our Cinematheque was Kiril Mkhanosvsky’s Give Me Liberty, a Milwaukee movie also gracing year-end best lists. Our programs included restored films by African pioneer Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, retrospectives of Reichert and Kiarostami, a 3D double feature of Revenge of the Creature and Parasite (no, the other one), a program of early women directors in America, a selection of films conserved by the Chicago Film Society, and a miscellany ranging from Olivia and Near Dark to Tropical Malady and Red Rock West.

Travels to festivals, partly covered in our blog entries, forced us to miss too many of these shows. But we couldn’t miss the final one: Die Hard (1988).

It’s a film I’ve admired since I first saw it in summer of 1988. I’ve taught it in many classes, but never written about it. Seeing it again, in a pretty 35mm print from the Chicago Film Society, has made me want to say a few things as my final blog entry for this busy year.

The man between

Think-piece pundits like to say that Hollywood movies are about good guys versus bad guys. But usually things are more complicated. Very often the good guy is an outsider caught between two large-scale forces, good or bad or both–the cattle ranchers versus the townspeople, or the mob versus the cops. Often the protagonist is an outlier, forced to solve the problem using means that respectable social forces can’t.

Call it the problem of the House Democrats. When the lawbreaker can’t be brought to justice, how do you make him pay? The answer is one that William S. Hart movies provided in the 1910s. We need a “good bad man,” a rogue agent who knows the scheme from the inside but is willing to do the right thing. Which means that he has to be flawed too, a little or a lot, and that he can eventually reform.

In Die Hard, the forces of law and order line up as the Los Angeles police and the FBI. The threat is Hans Gruber’s gang, posing as terrorists but actually planning to rob the Nakatomi Corporation of $640 million in bearer bonds and kill lots of hostages in the process. The naive TV broadcasters support both, recycling official scenarios of how hostage-taking works and reinforcing the gang’s masquerade as a terrorist group.

The contrasts are marked. The forces of order are American, in alliance with a Japanese company, while the attackers are Europeans. At the start, we hear American music (the rap played by the limo driver Argyle), but Hans hums Beethoven. The cops’ technology notably fails, as when the assault vehicle and a helicopter are consumed by firepower. But the gang’s hi-tech expert Theo can crack the vault, assisted by Hans’ plan to push the Feds to cut the building power.

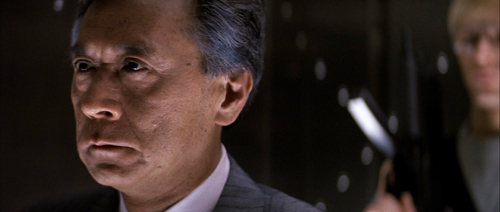

Above all, the forces of social order are strikingly inept, while the gang is ruthlessly efficient. Unlike the police, who “run the terrorist playbook,” Hans boasts that he has left nothing to chance. The cops can’t imagine an adversary that exploits the official by-the-book procedures. As for the business types, Takagi’s calm bluff and Ellis’s freewheeling jargon can’t cope with a gang leader who doesn’t get the Art of the Deal.

Clearly, America and Japan need help. That appears in the form of John McClane, the cop from the East Coast trapped in Nakatomi Plaza.

McClane is the man between, spatially and strategically. He witnesses the action from inside the skyscraper, and bit by bit he figures out the gang’s real scenario. And he’s caught between both forces. The gang tries to find and kill him, while the cops refuse to recognize him as an ally. Confronting Karl’s brother early on teaches McClane that he can’t play by procedure. (“There are rules for policemen,” says a thug who doesn’t believe in rules.) The LAPD’s ineptitude shows that McClane can’t expect help on that front. So he must become almost as reckless as his adversary, though in a virtuous cause. This principally means blowing stuff up.

McClane isn’t totally without resources. He has as helpers Al, the desk cop who comes on the scene and sustains his morale, and Argyle, who’s there to play a crucial role at the climax. But mostly he’s alone in facing problems. He needs weapons. He needs shoes. He needs to protect the hostages, most of all his wife Holly, who has climbed up the corporate ladder. (In another movie, she would be the in-between protagonist.) To keep Holly from becoming a bargaining chip, McClane needs to hide his identity. And he needs to figure out the gang’s ultimate plan, of seeding the rooftop with explosives that will destroy the building and cover their escape.

John’s solutions are notably low-tech. While the police and the gang depend on advanced firepower and computer finagling, McClane lashes an explosive to a desk chair and uses a fire hose as a rope. He has to improvise shoes by taping a maxi-pad to a bleeding foot. No holster for your automatic? How about some Christmas wrapping tape? And don’t forget to taunt your adversaries with Yankee wisecracks.

In the course of this drama, the very physical McClane becomes a model for his allies. Holly punches the reporter who revealed John’s identity, and Argyle cold-cocks Theo at the point of getaway. Most dramatically Al kills the revived Karl when he’s about to plug McClane. The people in between take up arms.

McClane and his allies solve the House Democrats’ problem. Law can’t be lawless, even in protecting itself. Business, always aiming at the bottom line, has to give up principles. (“Pearl Harbor didn’t work out, so we got you with tape decks.”) These forces of social order are inefficient, trusting, and superficial. They can’t stand up to sheer brutal onslaught. In a crisis they will fold, or simply choose the nuclear option: agents Johnson and Johnson are ready to lose a big chunk of hostages.

McClane is a mediating figure that permits the film to show you can be strategically lawless for the sake of lawfulness. The fly in the ointment, the monkey in the wrench, screws up plans on both sides, but for the benefit of everyone else.

The Big Dumb Action Picture isn’t so dumb

This thick array of thematic parallels would be interesting in itself, but it gets worked out through precise storytelling. There was a time when critics knocked action movies as simply ragbag assortments of fights, chases, and explosions. Die Hard, I think, changed ideas of just how well-wrought an action picture could be. About 53 minutes of it consist of physical action (including people sneaking around), leaving almost 70 minutes for other stuff: suspense, changing goals, surprise information, attention to parallel plotlines, and little moments like the thief pilfering candy just before an ambush.

The film typifies tidy classical Hollywood construction, beginning with an arrival (the jet) and ending with a departure (the McClanes in a limo). In between we get a big dose of the classic double plotline, romance and work. Holly’s job at Nakatomi threatens their marriage, and John takes on a temp job, that of fighting the gang, which also endangers the couple’s efforts to reconcile.

For every Superman, there’s a Kryptonite, and here the protagonist’s flaws include his fear of heights (set up in the second shot, reiterated throughout) and, more importantly, his resistance to Holly’s independence. By the end, he’s learned a lesson. The film’s streak of male sentimentality allows John to ask his wife’s forgiveness for blocking her career ambition. She’s ready to compromise too, reassuming his last name when she meets Al. The characters we care about change, at least a little. That could be the motto of most classical Hollywood plots.

As usual, we get crosscutting among several lines of action. John’s arrival is crosscut with Holly at work fending off Ellis, and in the rest of the film the gang’s stratagems are intercut with the cops’ plans and McClane’s efforts. At various points, five or six actions are alternating with one another.

All these escalating situations cluster into distinct parts, the four that Kristin has argued for as typical of Hollywood architecture.

The Setup runs about 33 minutes, culminating in the murder of Takagi and Hans’s promise that he can open the vault.

The Complicating Action, a counter-setup, coalesces around John’s goals of communicating with outsiders, avoiding capture, and attacking the thieves when he can. Through many chases and fights, the gang seeks to block all these efforts. The lines converge when John shoots Marco and tosses his body onto Al’s car. He gains the bag with the detonators, giving him the upper hand. Then the TV reporter gets involved, the cops arrive, and John is ordered to wait. Things seem to be stabilized.

After this midpoint, the Development supplies what Kristin calls “action, suspense, and delay.” Officer Dwayne Robinson arrives, pitting himself against Al and McClane. We can regard the police assault, Ellis’s clumsy attempt to broker a deal, and the arrival of the FBI men as a series of delays that endanger the stability of the standoff. At the end of this section, John meets Hans (posing as an escaped hostage): now both men know each other. And in the firefight that follows, John loses the detonators. Hans declares, “We’re back in business,” and the original plan can go forward.

The last twenty-five minutes constitute the Climax, launched by McClane’s “darkest moment.” He seems utterly beaten. Picking glass shards out of his feet, he gives Al a message for Holly over the CB radio. Al tells of his own burden, the accidental shooting of a child. The stakes are now very high.

Rapid crosscutting shows John finding the bombs on the roof and fighting with Karl, while the FBI helicopter attacks the building and Hans discovers that Holly is John’s wife. John stampedes the hostages down the stairs off the roof and escapes the strafing from the chopper before it blows. Argyle dispatches Theo, while John finds the surviving gang members in the atrium and shoots Hans, who falls to his death.

In the Epilogue, Al and John meet, Al dispatches Karl, Holly socks the newsman, and John and Holly drive off with Argyle.

These parts present a tight, logically building plot composed of swiftly changing situations. Along the way we encounter a great many motifs that create echoes or contrasts. Everyone notices the Rolex, at first a symbol of Holly’s talents but also of corporate swagger; only by unfastening it can they let Hans drop from the window. When Argyle floats the possibility that Holly will rush back into John’s arms for a movie ending, John murmurs: “I can live with that.” Agent Johnson speaks the same line, but for him it means an acceptable level of civilian casualties.

Holly’s unmarried name, Gennero, shows how a motif can develop in relation to the drama. At first it’s a sign of pride in her own identity (typical corporation, Nakatomi has misspelled it on the touch screen). Her name-change triggers the couple’s quarrel, but it has another narrative use: It conceals John’s identity from Hans. And at the end he introduces her to Al as Gennero but she reasserts her love by correcting him: “Holly McClane.”

Then there are differences of class and country. Hans reads Forbes, but McClane the US boomer references Roy Rogers and Jeopardy. (Hans is so unplugged from pop culture he thinks John Wayne was in High Noon.) Argyle the former cab driver and Al the cop know the downside of city life, but so does John the New York detective, who adapts Roy’s trademark phrase to the mean streets: “Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker.”

Even a conventional Hollywood gesture, that of attacking a picture of a loved one, acquires a nifty plot function. Annoyed at John, Holly slaps down the family portrait on her shelf. Good thing too, because otherwise Hans would have seen it during the invasion. We’re reminded of that picture when in a moment of quiet John looks at the same snapshot in his wallet. Only after Hans has encountered John is he able to flip the portrait back up and realize that Holly is the “someone you do care about.”

There are lots more felicities like these–so many that I’d consider Die Hard a “hyperclassical film,” a movie that’s more classically constructed than it needs to be. It spills out all these links and echoes in a fever of virtuosity. Hard to believe that the makers started shooting without a finished script.

Intensified continuity, personalized

Die Hard is a good example of a stylistic approach I’ve called “intensified continuity.” It’s a modification of the classical method of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. Here director John McTiernan and DP Jan de Bont tweak that approach in distinctive and powerful ways. You can find examples all the way through the movie, but I’ll draw most of my illustrations from the first hour, when the stylistic premises get laid out for us.

Cutting speeds accelerated sharply in Hollywood films from the 1960s onward, and for its time, Die Hard was a rapidly-cut movie. The average shot runs just under five seconds, about what you’d get in a 1920s silent film. By today’s standards, which fall more in the 3-4 second range (even for movies outside the action genre), it’s a bit sedate.

One factor that increases the cutting pace is a greater reliance on singles and close-ups. These are tighter than we’d expect in most studio films of the classic era.

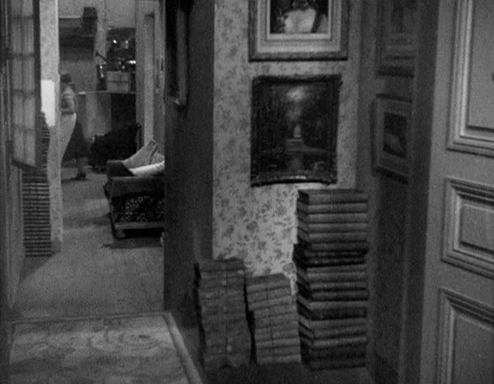

Even in close-up, the shots aren’t snipped free of their surroundings, thanks to the wide frame and layers of focus–both important in the film’s overall style, as we’ll see.

Likewise, intensified continuity exploits a greater range of lens lengths than we’d find in studio films of the classic era. We get wide-angle shots like those above along with telephoto shots throughout. Here the long lens is used to pile up people around Holly, and an even longer lens shows her optical viewpoint on the bandits in the office.

And there’s a free-roaming camera, thanks chiefly to Steadicam technology. But interestingly, Die Hard avoids some of today’s most common camera movements, such as shooting a fixed conversation with a sidewise or circular tracking shot. These would become more common in the 1990s.

McTiernan thought a lot about his camera movements, as he explains in interviews and the commentary track on the DVD. He wanted to shape spectators’ attention, to use camera movement to nudge things into view. “The audience’s eye wants to go with you.” Accordingly, more than in many contemporary films, Die Hard‘s camera movements have a shape: they end on a point of information.

Sometimes it’s just a quick pan, doing duty for a cut. At other times, the reframing is a gentle nudge that prepares for a new scenic element, as when Holly enters her office.

In shooting Predator (1987), McTiernan wanted to cut moving shots together, but his editor resisted. For Die Hard, he refilmed his camera movements at different rates so that two would match. A good example is when Karl’s brother strides carefully into an area under construction. The camera tracks with him, but when he turns to find the source of a whining noise, the arcing movement at the end of one shot is picked up in the next as the framing circles to reveal the saw.

That reveal is given, characteristically, in rack focus. I could have added rack focus as another featured technique of intensified continuity. McTiernan and de Bont take it very far, making Die Hard one of the great rack-focus movies. The image is constantly shifting focus to guide our attention to the changing layers of the scene.

This neat, compact presentation not only preserves the commitment to long-lens close-ups we find in intensified continuity. The technique also gives each rack focus the snapping force of a cut. (And you don’t need to build big sets.) Needless to say, the rack-focusing wouldn’t work if McTiernan hadn’t committed himself to staging his action in depth. More on this below.

Staging in ‘Scope

Die Hard finds ingenious ways to “let the audience’s eye go with you” in the widescreen format. Sometimes it’s a matter of classic edge framing. Thanks to a low angle, John and Holly converse along a wide-angle diagonal.

Sometimes McTiernan reverts to a technique not enough directors use nowadays: blocking and revealing. In classic cinema that was usually a technique reserved for long shots, when actors could move aside as part of ensemble. Die Hard applies blocking and revealing to the tight framings of intensified continuity.

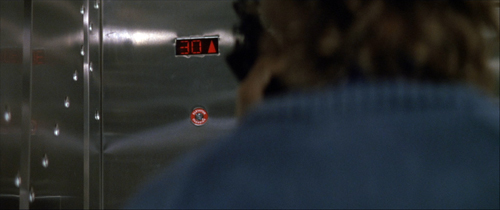

A thug in an elevator checks his weapon, pivots for an instant, and then moves aside to show the elevator arriving at the target floor.

Here again a rack focus helps. The moment reiterates the importance of the thirtieth floor in the skyscraper’s geography.

When Hans finds the body of Karl’s brother, we can study his expression. He flips the victim’s head to reveal a gunman, who looks to Hans before he says his line.

In a neat touch, the thug’s mouth isn’t shown. Today a director would probably show his whole face, but, really, who cares? The careful framing keeps him a secondary character, and a future target of McClane. And no need to rack focus on him, which would give him unwonted importance. All we need to remember him is that he’s the thug with long hair.

I can’t refrain from using one audacious example from late in the film. John and Hans have met, and Hans has revealed himself by targeting John with the pistol McClane has given him. In reverse shot, John reveals that it has no bullets and grabs it away from Hans.

But the pistol, and that gesture, have concealed the elevator behind them. When the pistol is knocked down, the elevator light pops on in the background. Our attention snaps to it, aided by that characteristic ping we hear throughout the movie (another motif).

The crisp turn of events, given visually and sonically, gets ampified by the acting. McClane’s cockiness turns to panic and Hans gets the upper hand. (“Think I’m fucking stupid, Hans?” Ping. “You vere saying?”)

The most bravura rack-focus comes during the climax, when the firehose reel whizzes down behind McClane and he realizes that he’s being dragged through the shattered window.

The coordination of the long lens, camera movement, staging, and racking focus is especially rich when Hans drifts among the hostages searching for the man in charge. He recites Takagi’s life history as he passes from one possibility to another (including, comically, Ellis).

At the climax of the passage, McTiernan’s staging-in-layers sets up Takagi, Karl, and Holly before Takagi takes charge. Briefly blocked by Hans, he admits his identity by stepping out from behind and into focus.

McTiernan isn’t done. A reverse shot of Hans finishing his spiel (“…and father of five”) punctuates the suspense. McTiernan buttons up this passage by returning to his “moving master” shot and having Karl shove Takagi out.

That clears the way for us to see Holly’s reaction. A beat dwells on her as she shifts her eyes to Hans, foreshadowing her conflict with him at the climax.

This sort of layering of faces popping in and out of visibility has precedents in earlier cinema, chiefly of the “tableau” period of the 1910s. McTiernan has, I think, spontaneously rediscovered for modern times what William C. de Mille was up to in the party scene in The Heir to the Hoorah (1916). (For more on that, go here.)

Of course McTiernan also has to work with the 2.35:1 anamorphic format, which enables him to spread his layers out more. That format also allows some remarkable compositions, such as the one surmounting today’s entry. The cut to the shot of John in Holly’s office uses the abstract splash painting (seen here for the first time) as a visual analogy for the explosion of gunfire offscreen at the same time.

McTiernan and de Bont constantly find striking but cogent images, thanks to lighting as well as color and format. Here’s McClane on top of an elevator peering through the perforated grille; his POV is a striking but still informative composition. the cut between the two provides a little punch of contrasting light and shade.

There are felicities like these feathered all through this remarkable movie, but the momentum of storytelling never flags. This remains a masterpiece of Hollywood filmmaking.

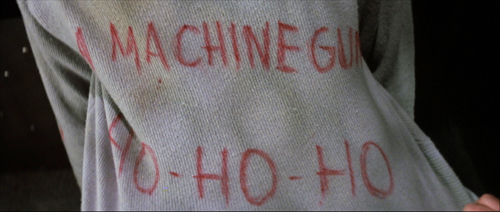

Thanks to our readers for following us this year. Kristin will be weighing in soon with her annual list of best films from ninety years ago. In the meantime, HO-HO-HO.

Madison owes an enormous debt to our Cinematheque team: programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, Ben Reiser, and Zach Zahos, as well as veteran projectionist Roch Gersbach. Santa should reward them. You can too by visiting the Cinematheque’s Podcast, Cinematalk. There you’ll find conversations with Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston, and James Runde.

For lots of background on the making of this film and the four sequels, there’s Die Hard: The Ultimate Visual History by Ronald Mottram and David S. Cohen. At rogerebert.com, Matt Zoller Seitz has a discerning appreciation on the occasion of the film’s twenty-fifth anniversary.

Jake Tapper has provided the definitive analysis of Die Hard as a bona fide Christmas movie.

McTiernan (with whom I share an alma mater) provides very good DVD commentaries (even for Basic). Prison also seems to have given him some pronounced political views. Alas, the website he created as a platform for them is apparently no longer available. Word is that McTiernan is preparing a new film, Tau Ceti 4, with Uma Thurman. A videogame promo is purportedly signed by him.

Of other McTiernan films, I also much admire The Hunt for Red October (1990). The Thomas Crown Affair (1999) seems to me better directed than the original, and The 13th Warrior (1999), despite being taken out of his hands, remains a pretty interesting film. (Name another Hollywood movie in which a Muslim poet visiting Northern Europe is justly appalled at its barbarism.) Nomads (1986) also has its good points.

I discuss the issues of narrative and style raised here at greater length in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. You can also search “intensified continuity” for blog entries hereabouts. On CinemaScope aesthetics, see this entry and this video.

Die Hard (1988).

BABYLON and the alchemy of fame

Babylon (2023).

DB here:

The circus parade has just passed, and behind it comes a little man mopping up all the droppings left by the lions, tigers, camels, and elephants. Somebody calls out, “Why don’t you quit that lousy job?”

The little man answers: “Are you kidding? And leave show business?”

From one angle, the joke anticipates the dramatic arc of Babylon. Damien Chazelle’s film traces how five characters seeking a future in the movies immerse themselves in a debauched culture, all for the sake of the dream machine.

For trumpeter Sidney Palmer and singer/actor Fay Zhu, the movie moguls’ bacchanals pay the bills and allow networking. Jack Conrad, a major star, loves being a drunken libertine but expresses contempt for the films he makes, movies that are only “pieces of shit” rather than innovative high art. Manuel Torres becomes an all-purpose gofer on set and eventually a studio executive, trying to work within the system. Nellie LaRoy is attracted to the movie world as much for the whirl of drink, drugs, dance, gambling, and fornication as for the glamor drenching the screen. Finding her film persona as the Wild Child, she can act by acting out.

These characters, all from working class origins, are brought together at a moment of technological upheaval: the period 1926-1934, with the establishment of talking pictures. This would seem to threaten moviemaking, not to mention the high life offscreen. Other pressures include the stock market collapse and the resulting depression, along with the establishment of a stricter standard of what could be depicted onscreen, the famous Hays Code. (The Code isn’t mentioned directly in Babylon, but it’s suggested as part of a broader concern with morality in the film colony.)

By the time sound has fully arrived, all of Babylon‘s primary characters, voluntarily or not, are no longer working in the Hollywood industry. Fay Zhu leaves for European production. Sidney, whose band is ideal for sound cinema, quits in disgust after he’s forced to darken his skin further. When the press and the public turn against Jack, he commits suicide. Nellie dances off into darkness and a lonely death. Manny, vainly in love with Nellie, can’t halt her self-destruction and has to flee town to avoid reprisals from the mob. From this angle, a confluence of debauchery and technology has wrecked whatever spark of life the system had.

The bleak satire that is Babylon poses a host of questions. Why, for instance, are there apparently deliberate anachronisms? The backdrop sets for the Vitoscope’s outdoor filming would be unlikely for 1926. Jack misquotes Gone with the Wind a decade before the book was published. The vast opening orgy seems more typical of Von Stroheim’s films than any actual Hollywood party on record. And given Vitoscope’s marginal status, how does the studio head afford such a mansion?

But I’m interested today in the ways the characters seek fame. I think their situations are a development of qualities we’ve seen in other Chazelle show-biz films. One way or another, nearly all those characters have sought to find a creative impulse that can make the compromise with a corrupt system yield some artistic rewards. The pressures and temptations of Babylon are extreme versions of factors we’ve seen at work in Whiplash and La La Land, but the characters react rather differently.

The suicidal drive for perfection

Whiplash (2014).

I think about that day

I left him at a Greyhound station

West of Santa Fé

We were seventeen, but he was sweet and it was true

Still I did what I had to do

‘Cause I just knew. . . .

These are the first lines we hear at the start of La La Land. Sung by a young woman slipping out of her car, they foreshadow the film’s plot developments. Sebastian and Mia, the couple at the center, both put their careers ahead of their love for each other and separate at the end. Each seeks success–Mia in screen acting, Sebastian in starting a jazz club–and that drive blocks a compromise in which one or both might give up their dreams for the sake of staying together.

Chazelle’s first two show-biz films present artistic achievement as a solitary quest that demands you to surrender normal ties to others. His strivers are loners, unable to subordinate their “dreams” to the demands of mutual love. Sacrificing everything to their quest, they have the self-righteous egocentrism of Romantic poets.

Whiplash tells the story of Andrew Neiman, an aspiring jazz drummer in music school. Worshipping Buddy Rich, he wants to be “one of the greats” himself. He spends hours in grueling solitary practice, and he has no friends. He is distant from his family, except for his father, with whom he goes to movies as if he were still a kid. He gives up a beginning romance with a young woman because, he tells her, he needs the time to practice.

The film introduces Andrew alone, bent over the drum kit, a distant figure in a corridor. In what follows, Chazelle isolates him, not through overwrought long shots showing him as remote from other students, but en passant, by medium shots that let us glimpse them in normal hallway conversation behind him.

Apart from competing with his peers, Andrew runs into Terence Fletcher, the fearsome leader of the school’s top jazz ensemble. Fletcher finds him practicing, invites him to try out for the band, and proceeds to run him through a program of brutal aggression, laced with just enough encouragement to keep Andrew on the hook. Good father/ bad father: the dynamic seems primal, but it’s an unequal struggle. Fletcher, always clad in satanic hipster black, knows how to dangle the prospect of success in front of Andrew’s bleary eyes.

That success comes in some degree, but haltingly. Andrew rises in the ranks, but through a series of unlucky mishaps, he humiliates himself in a major competition and assaults Fletcher onstage. He’s kicked out of school, but he’s also pressed to testify about his teacher’s abuse. It remains for Fletcher to entice Andrew one more time, tricking him into another public fiasco. Yet Andrew turns it into a sort of triumph.

Fletcher bullies Andrew into saying, “I’m here for a reason.” That reason, to put it in highfalutin terms, is the prospect of excellence within a worthy artistic tradition. To become as good as Buddy Rich is a wonderful prospect. But that’s a rosy picture. Breaking with Nicole, Andrew displays some of Fletcher’s cold-bloodedness, leading her to ask in her parting line, “What the fuck’s wrong with you?” She’s referring to his chopping off human ties, but she might as well be stressing Whiplash‘s suggestion that with that purity comes an eager masochism that is heightened by the master’s sadism. To be an artist is to sacrifice normal human ties but also to submit to a punishing game of power.

That game is played out in the career of Andrew’s idol. Buddy Rich, a technical virtuoso, had a combative view of musicianship. He conducted celebrated duels with other drummers and was said to have believed that for him, the drum was the solo instrument and the orchestra merely a batch of accompanists. As a bandleader, he was famous for vituperative attacks on his players. At once an obsessive like Andrew and a tyrant like Fletcher, he personifies the performer as a solitary seeker after inhuman perfection.

In what appears to be a burst of sincerity, Fletcher tells Andrew that the abuse he inflicts is solely to push the player to go beyond what’s expected. Only that will create the next Charlie Parker. Learning of the suicide of a student he tormented, he seems genuinely shaken–although he lies to his players by saying the boy died in a traffic accident. The sheer aggression that darkens his quest for quality is revealed when he deliberately sabotages his ensemble’s performance to make Andrew flub the piece.

At this point, though, Andrew catches some of Fletcher’s fury by launching into a maniacal solo. In its frenzied drive, it seems as if it could go on forever. By sheer force he wrests control of the orchestra from Fletcher, who seems with a smile to recognize what has happened and eventually plays along. He guides Andrew in a Rich-like descent into slower, then faster tempo. Reconciled with the strict father and the whiplashes he’s received, Andrew has demonstrated his heedless devotion to an exceptionally severe jazz tradition.

Music and machine

La La Land (2016).

Before it enacts the lovers’ separation foreshadowed in the opening song, La La Land gives us two protagonists aspiring to show-business success. Mia runs around town auditioning for TV shows, while Sebastian nurtures the dream of opening a jazz club. Like Andrew in Whiplash, Mia’s a loner with no deep relation with her peers. Sebastian, also a loner, harbors a conception of jazz playing that’s as combative as Buddy Rich’s. He explains a performance not as a communal exchange but as rivalry.

Look at the sax player right now. He just hijacked the song. He’s on his own trip. Every one of these guys is composing, they’re rearranging, they’re writing, and they’re playing the melody. And now the trumpet player, he’s got his own idea. And so it’s conflict and it’s compromise. . .

The game can get deadly. “Sidney Bechet shot somebody because they told him he played a wrong note.”

What drives the young and hopeful? The opening song suggests two impulses. First, there’s the fantasy realm of movies. “A Technicolor world made out of music and machine/ It called me to be on that screen/ And live inside each scene.” Second, there’s an urge to show the people back home that you’ve made it. “‘Cause maybe in that sleepy town/ He’ll sit one day, the lights are down/ He’ll see my face and think of how he/ used to know me.”

But neither purpose seems to be primary for Seb and Mia. True, Seb is a movie fan who quotes James Dean, but the couple aren’t apparently driven by fantasy. And although Mia comes from the sticks, she isn’t vindictive about it. Instead, they worry about succumbing to the mediocrity of the world they want to enter.

Jazz is dying, Sebastian laments. He plays at a piano bar and can’t introduce his own playlist. He picks up work as a keyboardist in an uninspiring but successful progressive-R&B ensemble. Mia auditions for clichéd roles and is facing a life as a barista.

The emptiness of their milieu is encapsulated in two party scenes. Unlike the infectious party in Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2009), these are scenes of careerist networking. Parties, Mia’s roommates argue, are essential for advancement; the person you schmooze today could hire you tomorrow (“Someone in the Crowd”). At the first party, confronted by snobs, Mia flees to the bathroom to confront herself in a mirror: Who is she really going to be? When she comes out, the party has become a sterile erotic tableau.

The alternative to giving people what they want is giving them you. Because Sebastian has found something of himself in jazz, he urges Mia to express herself in a one-woman show. She has her own tradition–the Hollywood movies her aunt showed her, and which she mimicked in skits she mounted as a girl. The show earns her an audition, where she channels her own experience in a song monologue about her aunt’s Paris adventures (“The Fools Who Dream”). It’s something of a reply to her mirror scene at the party. She gets the part, a lead to be built around her as a character.

Her successs and Sebastian’s steady if uninspiring life on tour initiate their breakup. Neither will sacrifice a career for a life together. Jazz may be conflict and compromise, but the only compromise visible here comes in the alternative time-frame climax showing the couple sharing domestic happiness. Somehow Mia has found stardom, with Seb as supportive spouse. But that’s a hypothetical outcome. As in Whiplash, you can achieve excellence by commitment to a personal tradition, but at the cost of close ties to others.

Party like it’s 1926

In the show-biz musicals, Chazelle’s protagonists’ goals aren’t defined as specific achievements–not winning a drumming prize but somehow becoming a drumming great, not getting a part in a particular show but getting some part in any show. Accordingly, like many off-Hollywood efforts, the films have episodic plot structures. Scenes tend to be more or less self-contained, with few dangling causes to lead to the next. Deadlines are set within a series of end-stopped scenes, not for the film as a whole. The action may be driven by coincidence, accident, and happenstance.

The episodic quality is less evident in Whiplash, whose scenes are dictated by scheduled rehearsals, solitary practice, and concert dates. Even there a flat tire, followed by a car crash, adds to the dramatic tension, and coincidence reintroduces Andrew to Fletcher after both have left the school. La La Land gives us a cascade of meet-cutes before the couple finally goes on a date. After that, their career trajectories depend chiefly on fortunate job offers, but also on Seb’s failing to remember a photo shoot. At the climax, a coincidental moment of traffic gridlock brings her and her beefcake husband back to the club to encounter Sebastian and the prospect of the future that might have been.

Moving from one protagonist to two to several in Babylon, Chazelle’s episodic inclination poses new problems. The major characters aren’t intimately connected, as in many network narratives. Manny is in love with Nellie, but he rarely sees her, and then only by accident. All are linked by being in the Hollywood system, and for the most part Chazelle is obliged to rely on crosscutting to interweave their developing careers.

The technique synchronizes their trajectories. Nellie is hired as actor at the first party, while Manny becomes Jack’s aide by escorting him home. The next day, as Nellie finds surprise success in her role for Vitoscope, Manny saves MGM’s costume picture by fetching a camera in time for a magic-hour shot. (The roots of Hollywood: a last-minute rescue.) Nellie’s rise to second lead is paralleled to Jack’s success in Blood and Gold, while Manny becomes Jack’s trusted assistant, sent to New York to catch the premiere of The Jazz Singer.

As the industry tries to assimilate sound, Nellie struggles and MGM hires Manny to supervise its Spanish-language production and coordinate musical shorts with Sidney’s band. Jack’s films start to bomb, Nellie’s star image goes out of style, and Manny rejoins Kinoscope to rehabilitate her. She remains a wild child, however, and Jack starts to realize his career is ending.

The storylines come to bleak endings when Jack commits suicide and Nellie drags Manny into her downward spiral, making them targets of James McKay’s mob. Once separated, Nellie vanishes and Manny flees the business. Sidney returns to playing live jazz for Black audiences, and his solo accompanies a montage sequence launched by Jack’s funeral and including a news story about Nellie’s 1938 death, possibly of a drug overdose.

To bring these protagonists physically together, Babylon relies chiefly on parties–five, by my count. The first and most sumptuous is an orgy hosted by Kinoscope’s boss Don Wallach. It demonstrates the dissipation of Hollywood culture. How could the comparative purity of Andrew or Mia or Sebastian survive this plunge into the mire? If nothing convinces one of the need to stand apart from the Hollywood milieu, this explosion of decadence should do it. Manny is a fixer (the guy sweeping up after the parade). Jack samples the fruits–a drink here, a quick copulation there–but Nellie is utterly in her element. She becomes the life of the party. If hedonism is an index of stardom, she shows, as she says, she was a star the moment she walked in.

At the party, Nellie and Manny explain why they’re attracted to this milieu. Manny says he wants to be part of something bigger, and he loves movies because they let you live the characters’ lives. Nellie agrees. Later, after she’s hired, she’ll holler that this will show everybody who said she was a loser. The two rationales–immersive fantasy and surprising the folks back home–are the same ones given in the opening song of La La Land. They have nothing to do with artistry in a tradition.

Jack’s case is a little different. He defends film as a high art, claiming that it needs a shot of modernism akin to Bauhaus design or twelve-tone music. Yet he has so little respect for his art that he plays his roles in an alcoholic stupor and condemns most films as shit. And claiming that sound would be as revolutionary as perspective in painting seems sheer silliness, especially after his joyless role in a regimented rendition of “Singin’ in the Rain.” In his longest tirade, he drops back to a mass-popularity argument. He tells his current wife that his immigrant parents found meaning in the nickelodeon, and millions more people will see him than will visit an O’Neill play.

You can argue that, like Mia in La La Land, Nellie and Jack succeed through self-expression. Nellie can cry on command because she remembers home; Jack cuts a dashing figure by his very nature. But they don’t work at their craft, or discipline their self-expression. Offscreen Nellie is a wastrel and Jack is a drunken pseud, babbling Italian, playing opera records, and garbling highbrow debates about mass culture and high art. Natural vitality gives Nellie and Jack some currency in the turmoil of silent film, but the discipline of talkies renders them obsolete.

They’re bereft of a tradition, though Jack senses the need for one. By contrast, Sidney has not only the jazz tradition but also, surprisingly, Scriabin. (Though in the Fletcher vein he admires Scriabin’s mutilation of his hands to play virtuoso passages.) It’s Sidney who quits the business out of principle. Not incidentally, he and Lady Fay seem the only protagonists with a powerful talents.

The second party, also hosted by Wallach, is somewhat more sedate than the first, though Nellie can be glimpsed nuzzling a unicorn’s horn. This initiates a montage that culminates in Nellie ecstatically watching her screen performance with an audience, who assail her for autographs.

The third party announces “Hooray for Sound” and brings together the three major characters in a night of frenzied activity. It’s reminiscent of the opening bacchanal, but seems more desperate, driving Nellie to break more bounds by daring death from a rattlesnake. (Lady Fay is the only partygoer bold enough to rescue her.) When Jack sees the melée that results, an uncharacteristically sustained and sober close-up, scored to a doleful piano, suggests that he senses that his milieu is headed for self-destruction.

Next party, far more upscale: Nellie tries to display her rehabilitation at a luncheon at a millionaire’s mansion. But her clumsy efforts to be genteel are mocked and so she lets loose with obscenity, attacks on food, and aggressive vomiting. Jack, Manny, Sidney, and FeiZhu have assimilated, but Nellie reverts to being the raucous low-life from Jersey. It’s career suicide. In parallel sequences we see Sidney forced into blackface and Jack frozen out by MGM.

The fifth party is a nightmarish descent into purgatory. “LA’s last real party,” McKay says as he ushers Manny and his colleague into a labyrinth of degenerate spectacle. Echoes such as the song “Her Girl’s Pussy” reveal the initial orgy as naive devilry: here is real shock. It’s as if the denizens of Hollywood have had their nerves rubbed so raw that only the most sadistic and gruesome entertainment will satisfy. Has this party been going all these years?

Taken all in all, it seems to me that the party sequences make explicit what the La La Land parties only suggested: to succumb to this milieu is fatal. The solitary quest of these lost souls render them vulnerable to temptations that will ruin them. In the Biblical Babylon, by pursuing false gods, the feasters have been weighed in the balance and found wanting. This is the story of people who think the party life (on the set of off) can last forever.

Granted, unlike Mia and Sebastian, the protagonists of Babylon have no other paths to their art. In the studio system, old-timers have assured us, you had to socialize with the decision-makers if you were to have a career. There were no equivalents of niche music clubs or indie film producers. In an odd way, Babylon is a roundabout tribute to the fluid artworld of today.

But then there’s the much-discussed final sequence.

Movies are bigger than ever

It’s 1952. Manny and his wife and daughter are visiting Los Angeles from New York, where Manny has a radio repair shop. As his wife and daughter return to their hotel, Manny drifts from the still-existent Kinoscope studio to a theatre. He finds himself in an audience watching Singin’ in the Rain. He sits transfixed, but his viewing is interrupted by a montage sequence that is, to say the least, a challenge to us.

What if the montage weren’t there? We’d have a scene in which Manny watches the new MGM movie restage the problems of early sound he witnessed, the tyranny of the mike and camera booth. He weeps. But then comes Kelly’s “Singin’ in the Rain,” which revises the mechanical chorus of old. Manny smiles. In his lifetime, the naive clumsiness of sound has been transmuted into something smooth and beautiful.

No wonder at the very end Manny is transported. He has achieved his hope of becoming part of something big. He has contributed to perfecting that imaginary world onscreen. We’d have what William Dean Howells claimed was the story all Americans wanted, “a tragedy with a happy ending.”

Hollywood has long justified its existence by appeal to magic. Disney provides the Magic Kingdom, while Lucas labeled his high-tech wizardry Industrial Light and Magic. At intervals throughout Babylon, characters echo the cliché. Jack calls a movie set the most magical place on earth; after his career has plummeted, he recalls the silent era in the same terms. The gossip columnist Elinor St. John celebrates “the camera’s magic tricks” in filming a battle. Without the inserted montage, Babylon‘s finale would confirm this mysterious magic, the way junk (the movies we see being made) can somehow become something splendid.

But we have that montage. Although it harbors many implications, it has the effect of sabotaging an upbeat ending. After a few shots recalling earlier scenes in the film (ending with the cliché of the couple passionately kissing), there’s a fusillade of images. They are snipped from silent cinema, abstract films, animation, widescreen splendors, foreign-language films, avant-garde films, computer films, CGI images, and wholly digital creations. Significantly, there are no Hollywood films represented from the 1930-1938 years we see in the last stretch of Babylon. It’s as if the visual narration is reminding us that the “something bigger” is indeed bigger than anything Manny experienced.

From one angle, it’s also a chronicle of technological change, all the “revolutions” that would follow the coming of sound. But where’s the magic? The usual counter to the mystique of magic is to point out the hard work of filmmaking. What delights us, on that account, is proficiency in craft and ingenious mastery of a tradition.

Chazelle floats another possibility. Having presented the digital future, he gives us luxurious images of dyes being mixed in colorful arabesques. Black-and-white footage is plunged into the brew.