Archive for the 'National cinemas: Israel' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021 visits the Middle East

Sun Children (2020)

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival, online this year, continues through this coming Thursday. Films for which audience members buy tickets are all available to watch until 11:59 that night. So far our experiences have been that the streaming system works quite smoothly, with easy access to your chosen titles. Despite geo-blocking (dictated by distributors) in some cases, many films can be watched from outside Wisconsin and the Midwest.

Now, let’s visit the Middle East.

Iran: Sun Children and There Is No Evil

Despite the tragic death of Abbas Kiarostami and the exile into relative obscurity of the Makhmalbaf family, the Iranian cinema continues to produce important films by a small number of auteurs, most prominently Oscar-winner Asghar Farhadi (whose A Hero was recently acquired by Amazon for release later this year), Majid Majidi, the irrepressible Jafar Panahi, and his equally irrepressible colleague Mohammad Rasoulof.

The latter’s There Is No Evil (2020), which won last year’s Golden Bear as best film at the Berlin Film Festival, is on the current WFF program. I wrote about it last year from the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Also on the program is Majidi’s latest, Sun Children, which we saw for the first time. Those who think of Iranian festival-oriented films as developing slowly and subtly will be surprised by this one. It is jam-packed with a multi-strand dramatic plot, suspense, fast cutting, and many characters, all handled very skillfully by Majidi.

The film begins with a dedication to the “the 152 million children forced into child labor and those who fight for their rights.” That child labor, as the exciting opening scene emphasizes, often involves small crimes. Four boys set out to steal a tire from a car in the parking garage of a luxurious, multi-storied shopping mall. The suspense begins right away as a guard confronts them. Two of them flee in a classic chase scene, going up through the levels of the mall, past high-end shops that they could never dream of entering. They escape, and it is revealed that the four friends work at a large repair shop, full of stacks of tires, presumably acquired in the same fashion.

Soon Ali emerges as our point-of-view character, desperate to rescue his mother from a mental-health facility. There she lies strapped to a bed after a presumed suicide attempt. Eventually it emerges that the family home recently burned, killing Ali’s sister, whose death drove his mother mad. His father is an addict, and Ali has become the breadwinner. A small-time crime boss sets him a task: enroll in a local school and explore the basement and tunnels under it (above), where a treasure is hidden.

Much of the rest of the film generates more suspense, as Ali diligently makes his way around various obstacles and crawls through branching tunnels day after day, always risking expulsion from the school if he is discovered. His three friends help him at first, but eventually he is left to traverse the seemingly endless tunnels (which are in fact the city’s storm drains).

This part of the film introduces another major plotline, since the school, dependent on private donations, is located in the slums of Tehran. Its aim is to teach young, desperate, potentially criminal boys skills that they can use to get honest jobs. The school is far behind on its rent and in danger of being closed. This adds further suspense as the school officials, particularly a sympathetic vice principal, struggle to find donors. The schools debts lead to one of the film’s big action scenes, as, finding the gates locked one morning, the principal urges the boys to scale the fence. They do this with a determination that reveals their realization that their only hope for a decent life lies in the education they have been receiving.

They eagerly participate in a festival and pageant put on for potential donors (top).

In an interview, Majidi said that the “Sun School” that gives the film its name is based on an actual school in the Tehran slums, the “Sobhe Rooyesh” (“Morning of Growth”). The non-professional child actors, whose performances are all completely natural and affecting, were recruited from the school and surrounding slums. Roolholloh Zammi, who plays Ali, won the Marcello Mastrioanni Award at Venice last year. (I wish we could have been there to see him win!) Only the adults are played by [professional actors.

Israel: Here We Are (2020)

Given the current situation in Israel, it is just as well that Nir Bergman’s gentle psychological study Here We Are (a sadly unmemorable title) has no reference at all to politics, the military, or ethnic tensions. It’s a simple story of a man who has given up his career to care for his severely autistic son and is having difficulties facing the fact that the boy is nearly a man.

The early scenes set up Uri’s disabilities, as well as his obsessions (including pet goldfish–above–and dogs) and phobias (snails). They also establish Aharon’s utter devotion and patience as he cooks yet again Uri’s favorite pasta stars and uses an obviously well-established imitation game to coax his son past imagined snails on a biking route.

The plot action kicks in when Ahron’s estranged wife Tamara shows up, determined to arrange Uri’s transfer to a group home for young people with disabilities. Ahron angrily resists, claiming that Uri is happy at home and that he can care for his son himself.

We seem to be set up to view Ahron as the noble, self-sacrificing father and his wife as the shrewish woman who wants to dictate her son’s life. Eventually, however, Tamara obtains the legal papers requiring Ahron to bring Uri to his new home. Ahron sets out, but along the way he decides to go on the run with Uri, despite having little money.

Along the way there are growing hints that Ahron is stifling both Uri and himself. Twice he simply ignores Uri’s budding sexuality during encounters with young women.

The two seek shelter with an old friend of Ahron’s, Effi, an art teacher who reveals that Ahron had had a prominent and lucrative career as an artist and designer, which he had given up to care for Uri. Her attitude toward Ahron suggests her openness to a romantic relationship with him. Eventually we begin to doubt that he is acting in the best interests of himself and Uri, especially during a scene in which they are forced to dine on ice-cream sandwiches in a bus-station waiting-room.

Here We Are is a film that unfolds gradually and overturns your expectations slowly but thoroughly.

France-Lebanon: Skies of Lebanon (2020)

Chloe Mazlo is a French animator and artist who has previously made shorts (including The Little Stones, which won the 2015 César for Best Animated Short). Inspired by her grandparents’ life in Lebanon (he was Lebanese, she Swedish) during the lengthy civil war, she has made a feature that combines occasional animation with live action.

The film starts out in a stylized, fantastical world that inevitably has led critics to compare Skies of Lebanon to Amélie (2001). Alice, the heroine, is alienated from her parents and her home country, Switzerland, and take a job as a nanny in Beirut. The city as it was in the 1950s is represented by matte shots of actors presumably filmed against a green-screen, with backgrounds filled in by blow-ups of tinted postcards of the period. Such shots have a charming effect.

Alice meets cute with a handsome physicist whose goal is to invent a rocket to put the first Lebanese astronaut into space. Their romance develops in a fantasy landscape of patently artificial rocks and stars (bottom). They settle down together, raise children, and pursue their careers, with Alice becoming a watercolorist.

The fantasy strain in the film is most obvious in the brief animated scenes, as when a split-screen telephone conversation juxtaposes the real Alice with puppets representing her angry parents, who demand that she return home (top of section).

About a third of the way into the film, the tone switches abruptly as the Lebanese civil war breaks out. The animations and postcard background disappear. As characters flee and disappear mysteriously, a shot of a wall with “have you seen” photos pasted up emphasizes the danger that Alice is trying to ignore.

Even during the lengthy wartime portion of the film, there remains a faint underlying humor. Yet the abrupt shift of tone when the war starts is unsettling, given that we had settled down for a whimsical romance and end up with a war story. Presumably the idea is to emphasize how war breaks into the calm of ordinary life and banishes it. Whether audiences will take it that way is another matter. On the whole, however, the film is an imaginative and promising first feature.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

Skies of Lebanon (2020)

Torino tour of world cinema

Synonymes (2019).

Kristin here:

After visiting museums on the one free day we allowed ourselves in Turin before the festival began, we launched into viewing films from around the world. Here are three of the best we’ve seen, to add to the ones David has discussed.

Synonymes (France/Israel/German, dir. Navad Lapid)

Israeli director Navad Lapid has become a familiar figure for us as we have visited past festivals in Vancouver. We blogged about his Policeman in 2011 and The Kindergarten Teacher in 2014. His latest film raises his profile considerably, having won the Golden Bear at Berlin and had its North American premiere at Toronto. (Ozon’s By the Grace of God, which we blogged about from Vancouver, won the Silver Bear.)

Synonymes started with an abrupt chase, with the camera bouncing about as it follows our hero, Yoav, as he dashes through the streets of Paris (above). I was worried that this loose style of shooting would dominate, but Lapid has something more disciplined involved. The unfastened camera is usually used for exteriors, while interiors are made up of static shots.

He arrives at a large empty flat that someone has loaned him, where the heat has apparently been turned off. He proceeds to take a cold shower, and, having neglected to lock the door, he finds his backpack and sleeping bag stolen. He is left naked with no possessions whatsoever. A wealthy young couple from downstairs rescue him from hypothermia and become fascinated with him, taking him in briefly. Émile gives him money, as well as clothes. He holds up a long series of colorful shirts, which he himself apparently never wears, judging from his own muted wardrobe.

Lapid matches these colors to the decor, especially the distinctive, bright mustard-hued overcoat that Yoav wears through much of the film. The coat makes him easy to spot and marks him as an outsider among the more conventionally dressed Parisians around him (see top).

We soon learn that he is fleeing from his oppressive life in Israel and wants to become a Frenchman as soon as possible, refusing to speak anything but French despite his elementary grasp of the language. (The title comes from his habit, when wandering around alone, of muttering a series of words with similar meanings.)

There’s not much of a goal operating here, apart from Yoav’s increasingly strained efforts to turn himself into a Frenchman and abandon the violence inculcated into him by his time in the Israeli army. His one conventional job is as a security guard at the Israeli consulate. His violent outbursts and willfully eccentric behavior increase as the film goes along.

The rather episodic film revolves around the driven performance of Tom Mercier, an Israeli theater student who knew no French and, remarkably, is making his film debut here.

Kino Lorber has released Synonymes (as Synonyms )in North America. For a plot summary and a list of theaters where it has played and will be playing into January of next year, see the company’s webpage.

True History of the Kelly Gang (Australia, dir. Justin Kurzel)

Bushranger films, of which True History of the Kelly Gang is one, are more or less the Australian version of American westerns. The tale of Ned Kelly and his gang is almost a mini-genre in itself, going back to what is claimed to be the world’s first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906, dir. Charles Tait, partially surviving).

Justin Kurzel adopts a fresh take on the familiar Kelly tale, which is as much myth as fact. He based his film on Peter Carey’s novel of the same name, which won the Booker Prize and many other awards. By adding “True” to his title, Carey both acknowledged the fact that he was embroidering the national legend as much as adhering to the facts.

Kurzel does the same. A title appears on the screen: “Nothing you are about to see is true.” All of the words besides “true” fade out, and the rest of the film’s title fades in beside it. Those of us not steeped in Australian history and culture will not be able to fill in the inauthentic parts, but it doesn’t really matter. It’s a gripping story nonetheless.

The film opens when Ned is a boy, living with his mother Ellen and siblings in a bleak part of the bush consisting mainly of stubby dead trees (above). Although an honest lad to start with, he is drawn into the family’s long-time opposition to the local constabulary and military forces. Despite her fierce love for her family, Ellen sells him into apprenticeship to a putative merchant and herder (played with not quite too much gusto by Russell Crowe). The man turns out to be a highway robber, and Ned is reluctantly pushed toward a life of crime.

The film follows the novel in using a voiceover narration by Ned, reading from a diary purporting to be for his young daughter after his inevitable demise. (In fact the figures of the wife Mary and the daughter are part of the tale’s embellishment.) Indeed, we are nearly always in his presence and are led to sympathize with him because almost everyone around him except Mary exploits him.

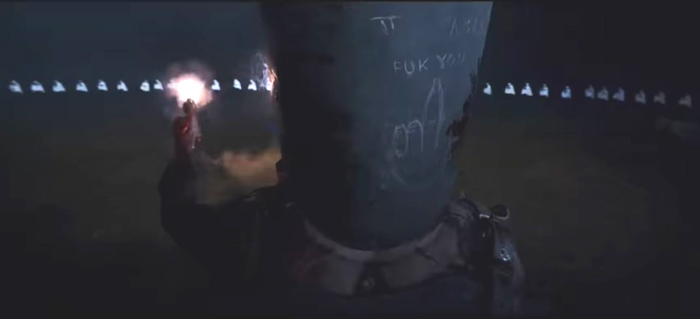

The film is visually impressive, including some shots that leave one wondering how they were accomplished. At intervals there are fast drone shots above the sea of dead trees as Kelly and others ride horses through the landscape. One shot at night features an immense pool of light from above that moves smoothly with the horseman, keeping him visible as the stark gray trees appear from and disappear into the inky surroundings.

The climactic shootout between Kelly’s gang of four men in home-made armor and a large posse approaching from the distant background provides an unforgettable image. The last man standing, Kelly himself, back to camera, fires at a line advancing figures. They appear spread across the screen as tiny white figures–looking distinctly like Ku Klux Klan men in full garb. (See bottom.)

True Story of the Kelly Gang contains considerable strong profanity and violence, which would seem to warrant a risky hard-R rating in the US. Nevertheless, just before the film’s world premiere at Toronto, IFC acquired the North American rights to the film for a reported seven-figure sum, bidding against three other distributors. IFC will evidently release it in 2020. (The first trailer has just been posted on Youtube, but there is currently no mention of the film on the IFC website.)

Noura’s Dream (Tunisia/France/Qatar, dir. Hinde Boujemaa)

Increasingly female directors working in Middle Eastern and North African countries are gaining a foothold in the international film market. Recent notable films have been Saudi director Haifa Al Mansoor’s The Perfect Candidate in competition at Venice and Nadine Labacki’s Lebanese film Capernaum, Jury Prize winner at Cannes in 2018.

Tunisian director Hinde Bujemaa’s Noura’s Dream centers on a woman with three children who is awaiting an imminent divorce from her incarcerated husband, Jamel, so that she can marry her lover, a car-repairman, Lassaad. Meanwhile she is working in a laundry to enhance her government checks and support her family (above).

Though Tunisia is somewhat more liberal than other Muslim countries, Noura still faces traditional prejudices. In the opening scene, an official tries to talk her out of the divorce for the sake of her children–as if living with an abusive criminal for a father is more desirable than having a kinder stepfather.

Jamel is released unexpectedly early, and Noura must live with him for the few days until the divorce is final. She pretends to be considering staying with him, despite the fact that he returns to his criminal activities and abuses his family, at one point throwing them out of the house (above). As Bujemma points out in a Variety interview, however, Jamel is not all bad, not taking the option of betraying to the police Noura’s adultery with Lassaad, still a criminal act in Tunisia.

In a way Noura’s Dream seems to reflect the considerable impact that Asghar Farhadi’s Oscar-winning films have had on other directors in the region. The situation of an impending divorce recalls A Separation, yet Farhadi’s films tend to have quiet, “everyone has his reasons” plot arcs with twist revelations and moral ambituities. Here, telling such a story and eager to display the biases against women in Tunisian society. Bujemma takes a more melodramatic approach. Jamel is an unrepentant criminal and Noura is a brave, determined woman struggling to separate herself and her children from him. Lassaad is a decent fellow nevertheless ultimately driven to reject her when she shows no signs of leaving Jamel.

It’s a film that effectively builds up considerable sympathy for Noura, played by prominent Middle-Eastern star Hind Sabri, and withholds hope, or possible hope, until the last shot.

Noura’s Dream has played several festivals, including Toronto, London, and now Torino and has releases in Europe and its native country, but there is so far no North American distributor.

The Horror Thread

As David mentioned in our previous post, the Torino Film Festival includes a retrospective program each year. This time it was horror films, from Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari to Roy Ward Baker’s Dr Jekyll & Sister Hyde (1971, UK). I fit some of these into my schedule in between the new films.

There were 35mm prints of I Walked with a Zombie (1943, Jacques Tourneur), The Masque of the Red Death (1964, Roger Corman) and The Devil Doll (1936, Todd Browning), among the films I saw. The DCPs of The Body Snatcher (1945, Robert Wise) and The Innocents (1961, Jack Clayton), the latter shown immediately after the former, offered two gorgeous examples of black-and-white cinematography. In all the retrospective included 36 films, many of them probably being viewed by Italian attendees for the first time in their original languages, rather than dubbed versions.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page.

True Story of the Kelly Gang (2019).

Finding a form: The College Cinema at the Venice International Film Festival

This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (Lemagang Jeremiah Mosese, 2019).

DB here:

For the third year I participated in the Mostra’s College Cinema, a wonderful program that funds and guides three features by up-and-coming directors and producers. (Details are here.) I’ve reported on the earlier sessions here and here.

This year my developing reaction to the trio of features was governed by what Kristin and I did the day before our panel. We saw two superb classics: Bertolucci’s The Spider’s Stratagem (1970) and István Gaál’s Current (1964). They reminded me of what ambitious filmmaking was like before the arrival of screenplay manuals dictating character arcs and first-act turning points.

In those days, a filmmaker was likely to find a distinct, even unique form for a story. The filmmaker would design the film organically, creating a large-scale shape that would let technique and dramatic structure build in relation to each other, not in accord with standard formulas.

Coupling via monitor

A good example is The End of Love, directed by Karen Ben Rafael. The Israeli Yuval and the French woman Julie have a child. He waits in Israel for a new visa, while Julie must manage child care under the pressures of her job in an architecture firm. Each begins to suspect the other of infidelity, and their families in each country add to the tension.

So much for a traditional “relationship” movie, whose ups and downs could have been presented in a standard way. But Rafael and her co-screenwriter Elise Benroubi hit upon a fresh way to trace the couple’s conflicts. Yuval and Julie are keeping in touch via a Skype-like video service, and we are completely confined to their exchanges in this medium. We see only what they see, in a series of to-camera shot/reverse-shots.

Some recent genre films have been “monitor movies,” like Paranormal Activity 4 (2012), Chronicle (2012), Unfriended (2014), and Searching (2018). But these exploit the device for suspense and horror. The End of Love lets the conditions of video communication structure the ongoing drama. A teasing opening suggests that the camera is lying in bed between the couple as they caress themselves; the next scene–a remarkable shot in itself (above)–reveals that video is their channel of communication.

As the film goes along, tensions between Yuval and Julie are presented as much through the mechanics of video exchanges as through the actors’ (very persuasive) performances. Unanswered calls signal a growing indifference. A mysterious shot wobbling through a dance club suggests either a phone accidentally turned on or a loud, defiant assault on the other person. I was especially taken by the moments when we get slight change of eyelines as characters look from the camera to study the display image of the other person.

The End of Love triggers a lot of ideas about how modern couples are led to expect that technology can overcome family problems. Being always online, always “in touch,” doesn’t mean that you’re engaging authentically with someone else. For all its power, the video hookup in the film creates an illusory intimacy, and its glitches stand for the aggravations, little and big, that come with physical separation. This thematic implication grows organically out of the creative decision to confine our viewpoint to what the camera can see and hear, but not heal.

Social drama into community myth

Another vigorous example of letting the material summon up the film’s form is This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection. Directed, written, and edited by Lemogang Jeremiah Mosese, it’s a poetic work that develops its imagery out of a dramatic situation.

The eighty-year-old Mantoa learns that her only surviving relation, her grandson, has died in a mining accident. After being consoled by her priest and the local choir, Mantoa tries to restabilize her life. But when she learns that her village is to be flooded for a dam project, she vows to save the bodies in the local cemetery–and to prepare her own grave.

This tale, set in Lesotho, is framed by a narrator telling us about her and her community. He sits in a blast of yellow light adjacent to a pool hall, and at intervals the story action pauses for his comments. The film takes its time–about 300 shots in two hours–to dwell on the details of her daily routine, such as the portable radio hanging from the wall, or Mantoa’s changing outfits.

But there are also more surreal images, such as Mantoa on a burned-out bedspring being slowly surrounded by sheep. The community that eventually supports her is presented as an almost abstract force, as are the out-of-focus government workers slowly hacking away at the perimeter of the village. The climax of the film makes powerful use of those figures as Mantoa confronts them in her boldest provocation of all.

Again a familiar situation–a tenacious elder tries to halt the destruction of a community (think Wild River)–is given fresh life through formal elaboration. Out of a primal conflict, Mosese generates a work of mythic dimensions. He does it through lustrous visuals, an evocative soundtrack, and a character who creates a legend that will live for generations.

Town and country

If The End of Love traces a jagged decline in a relationship, and This Is Not a Burial lifts a social conflict into spirituality, Lessons of Love finds another structure, this one aiming to express the inarticulate feelings of a man stuck in a situation. It’s a circle.

Yuri toils on his father’s farm, while his younger brother and sister try to avoid their responsibilities. Stolid, silent, and glum, Yuri harbors a good deal of anger, occasionally expressed in road rage. He relates to the world almost completely through physical contact.

Director Chiara Compara and her co-screenwriter Lorenzo Faggi start from a classic pattern: the migration of an innocent from the countryside to the city. This pattern is refreshed through a strategy going back to Neorealism: the insistence on the physicality of daily routines. A prolonged moment of Yuri tuning a radio recalls the famous scene of the maid’s morning ritual in Umberto D.

The early stretches of Lessons of Love stress the demands of farm work. The first shot is of a milk can, and soon we see logging, veterinary inspections, the purchase of a cow, and the dull evening meal. But we also get a sense of Yuri’s longing when he soberly eats during a TV love scene, and soon enough he’s visiting a strip club, watching as impassively as he did the TV show.

Through a tissue of routines, Yuri’s vague thoughts about escape emerge, and soon he is considering buying cowboy boots, dating Agata, and getting a construction job in town. That’s when the circular structure gets initiated, and new routines replace the old ones. Again, the details of hard labor aren’t stinted, and Yuri is challenged to break out of his smoldering solitude. Can a man who punches and embraces his favorite cow, and who furiously whacks a driver-side mirror, ever learn to talk to a woman who’s kind to him? The last shot of the film, discreetly echoing the first, provides the answer.

A fraught love affair, a defiant elder speaking up for a community’s heritage, and a lonely, locked-in man are familiar enough points of departure for a film. But these three College features offer fresh, rigorous treatment of their stories. Three acts and vulnerable-but-relatable heroes and heroines? Not necessary! There are other ways to go, as young filmmakers can show us.

Thanks as usual to Peter Cowie for inviting me to join the College Cinema panel, and to Savina Neirotti, the Head of the program. Thanks as well to other participants for lively conversation: Chaz Ebert, Glenn Kenny, Mick LaSalle, Michael Phillips, and Stephanie Zacharek. As ever, we appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Glenn has a fine appreciation of the College films on rogerebert.com. He too was reminded of Wild River, but no surprise as we’re both nerds in this (and other) respects.

The End of Love (Karen Ben Rafael, 2019).

Venice 2018: The Middle East

As I Lay Dying (2018)

Kristin here:

As Variety‘s Nick Vivarelli pointed out earlier this week, Arab cinema is well represented here at the Venice International Film Festival. The same is true of Middle Eastern films in general. I couldn’t catch all them, but here are some thoughts on those I saw.

The Palestine question as sit-com

Comedies about ethnic hostility in Ramallah are understandably rare. For a long time the only one I knew of was Elia Sulieman’s masterly Divine Intervention (2002), though there may be others. Now we have Sameh Zoabi’s Tel Aviv on Fire, a real crowd-pleaser playing in the competitive Horizons section of the festival, a section designed to showcase promising early-career filmmakers.

Despite the title, which might suggest a grim tale of conflict, perhaps involving terrorism, the film is very funny. “Tel Aviv Is Burning” is the name of a daily melodramatic TV series made in Ramallah by a group of Palestinians but enjoyedby both Jewish Israelis and Palestinians–mostly women. (All citizens of Israel are considered Israeli. This means that, ironically, the Israeli Film Fund is required to provide funding to Palestinian projects; it is one of Tel Aviv on Fire’s backers.) The story arc is at a point where a Palestinian woman is assigned to disguise herself as Jewish in order to seduce an important Israeli general and get a key to a hiding place for military plans.

Salam, the protagonist (played by Kais Nashif, who won the best actor award in the Horizons competition), is the lowly nephew of the show’s producer, fetching coffee and helping keep the Hebrew dialogue authentic. Suggesting a bit of action one day, he is promoted to be a writer, despite having no experience or skill. When Saam is stopped for no reason at an Israeli checkpoint (above), he meets a general, Assi. Salam boasts about being a writer on the show, which happens to be a favorite of Assi’s wife. Hoping to impressive his shrewish spouse, Assi puts pressure on Salam to slant the story: the heroine should fall in love with and marry the Israeli general she has seduced. Eager to get away, Salam agrees.

The rest of the story is a cleverly scripted series of twists as Assi makes further demands to make the Israeli general more sympathetic and Salam tries to foist these on his reluctant collaborators. One might argue that the final surprise revelation does in fact make the film lean toward the Israeli side. On the whole, though, Zoabi’s film balances the two factions and manages to convey that the ongoing conflict is absurd, given the many similarities between the two main characters and the universal appeal of “Tel Aviv on Fire” across Israel’s population.

One strength of the film is the stylistic contrast between the main story’s conventional lighting and location shooting and the tacky sets, garish colors, improbable dialogue, and over-the-top performances in the scenes from the TV series.

A microcosm of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Veteran Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai contributed a program of two films to the festival. The first was a short, A Letter to a Friend in Gaza, the second the feature A Tramway in Jerusalem, both playing Out of Competition.

A Letter to a Friend in Gaza is a evocation of the bitter disagreement between people, even within families, using a text by Albert Camus to sum up the issues in poetic form. I suspect one would need to know a great deal about the Palestinian occupation to fully grasp this oblique work.

The issues are readily apparent, however, in A Tramway in Jerusalem. Set aboard a tram, with occasional shots on platforms where it stops, the action consists of a series of short scenes between a wide variety of citizens. The episodes are separated by titles announcing the time of day, but these skip about, suggesting that this is not a day-in-the-life-of a tram tale but a series of random encounters. The vignettes are not connected, though a few characters recur, most notably a French tourist introducing his beloved Jerusalem to his son. The participants in these short scenes are played by actors, though the only one likely to be recognizable to a broad audience is Mathieu Amalric as the tourist (above).

The scenes suggest a range of possibilities for successful or failed coexistence. For no reason but prejudice a woman accuses a Palestinian man standing next to her of sexual harrassment, and the guards on board immediately throw him to the floor. Two sophisticated young women, one Palestinian with a Dutch passport, the other an Israeli, are standing side by side. They chat casually, clearly very much alike, and when, again for no reason, an aggressive guard demands the Palestian’s passport, the Israeli stands up for her. In an overly long episode, a Catholic priest soliloquizes about the death of the three religions struggling for dominance in their mutually sacred city. The French tourist, determined to idealize Jerusalem, fails to realize that a local couple is poking fun at him by enthusiastically advocating the violent suppression of Palestinians.

The Iranian search narrative endures

Not all Iranian films involve searches by any means, and yet searches, whether they involve a journey or not, provide the structure of many familiar classics like Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Mirror. By chance, two films at this year’s festival show searches involving in one the beginning of life and in the other its end.

Mostafa Sayari’s first feature, As I Lay Dying (Hamchenan ke Mimordam), also played in the Horizons competition. It begins after the death of an old man. One of his sons, Majid, who has cared for him recently, admits to the doctor that he had provided the sleeping pills that apparently killed his father, but the doctor agrees not to mention this on the death certificate. A hint that the time of death is not known provides the first clue in a subtle mystery. Further clues surface in the course of a psychological drama among the four siblings who assemble to drive their father’s body to a small, distant village for burial.

As the journey continues and quarrels develop, the siblings question Majid as to why he chose this remote village for the burial. The length of time that the father has been dead emerges further as a significant factor. By the end, the answers to the three siblings’ questions becomes apparent to them.

Speaking with others who had seen the film, I heard complaints that the story was difficult to understand. I think that As I Lay Dying is something of a mystery story, without being strongly signaled as such, and that sufficient clues are dropped along the way that the viewer should be able to understand the situation by the time the story ends, rather abruptly and perhaps seeming not to offer a resolution. (It would help to know that Muslim burials are supposed to take place as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours.) Certainly nothing is made explicit at the end, though again, an attentive viewer should figure out the implied outcome.

The film takes place largely on a bleak desert road, including some beautiful widescreen compositions reminiscent of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s work in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, perhaps coincidentally also involving a search in the desert, in that case for an already buried body. (See top.)

The search narrative goes back at least as early as Ebrahim Golestan’s Brick and Mirror (Khesht O Ayeneh, made 1963-64, released 1966). It was one of the historically important films shown in the “Venice Classics” series of recent restorations.

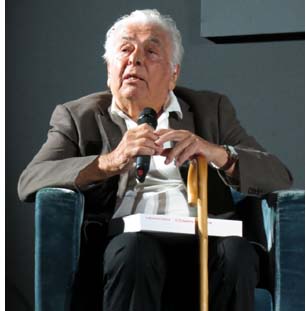

Brick and Mirror is generally considered the first Iranian art film, having come out three years before Dariush Mehrjui’s classic, The Cow (1969). Golestan was an experienced filmmaker, mostly of documentaries, but Brick and Mirror was his first fiction feature.

The title has nothing to do with the subject matter of the film but is more evocative, being, as Golestan has revealed, derived from a Thirteenth Century Persian poem: “What the Youth sees in the mirror, the Aged sees in the raw brick.” The word “brick” here does not refer to the familiar fired brick, which costs money to buy, but to the simple mud brick, widely used by the poor across the Middle East, since anyone with access to silt and a simple wooden frame can make them.

The story begins one night as the taxi-driver protagonist, Hashem, discovers that a woman passenger has left a baby in the back seat of his car. In a famous scene, he wanders the desolate neighborhood searching for her (see below). Eventually his girlfriend joins him in his apartment to help care for the child. The experience leads her to hope that they can marry and raise the child themselves, turning their so-far aimless affair into a family. The quest to find a practical, humane way to dispose of the baby–or not–takes up the rest of the film. Near the end, a lengthy scene of babies and young children in an orphanage reflects Golestan’s documentary experience.

The new print recalls the rough, often dark look of black-and-white widescreen films of the 1960s, especially those of the French New Wave. Golestan’s story of fruitless wandering and unresolved relationships has been compared by some critics to the films of Antonioni, and it seems clear that Antonioni’s work and other European films of the 1950s and 1960s influenced him. There are, however, distinct differences. While Antonioni deals with the psychology of bourgeois characters (except in Il Grido), the couple in Brick and Mirror are working-class, and their problems are caused as much by their social situation as by any general ennui.

Remarkably, Golestan was present to introduce the film. At 97, he remains articulate and charming. He primarily sketched out his early career and the inspirations for Brick and Mirror. The most interesting point concerned a startling moment during the early scene of Hashem searching the dark neighborhood for the elusive mother of the baby. A close composition of him at the top of a long stairway suddenly leads to a quick series of axial cuts, each shifting further back until he is seen in extreme long shot. The moment reveals the empty staircase and emphasizes the hopelessness of the chase. Golestan emphasized jump-cut quality of the passage and mentioned that he had not seen Breathless at the time Perhaps the moment harks back further, to the axial cuts of static figures used in Soviet films of the 1920s and the work of Kurosawa.

Previously only incomplete, worn prints of Brick and Mirror were available, and then only in rare screenings. The importance of this restoration was emphasized by the festival’s publication of a short book, Brick and Mirror, which brings together a number of essays by Golestan and others. It also describes the restoration, done with the director’s cooperation and accomplished at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in Bologna. My thanks to Ehsan Khoshbakht for providing me with a copy and more generally for his important work in reviving Iran’s film heritage, including programing the Iranian season at Bologna that I reported on in 2015.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

For more photos from this years Mostra, see our Instagram page.

[September 12: Thanks to Steve Elsworth for some corrections.]

Brick and Mirror (1966).