The ten best films of … 1928

Friday | December 28, 2018 open printable version

open printable version

La passion de Jeanne d’Arc

Kristin here:

Time for our twelfth annual alternative to the usual list of the ten best films of the current year. Instead, I offer a list from 90 years ago, in part for fun and in part to call attention to some lesser-known classics that are worth discovering. (See here for our lists from 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, and 1927.)

The year 1928 marked the triumphant conclusion of the silent cinema. Very few sound films were made that year, and those that were often included only music, perhaps sound effects, and occasionally some passages of dialogue. Sound was not innovated because the silent cinema was in aesthetic decline. Quite the contrary. It was initially an enhancement that film-industry people assumed would make films more lucrative. In most cases the “talkies” that followed over the next few years were inferior to their silent predecessors, in part due to the limitations of the new sound technology. Those who opposed the addition of sound could point to the films of 1928 as evidence that the young art form had already reached a peak of perfection that was being tarnished by the addition of recorded sound.

In compiling this year’s list, I came up with eight titles that seemed unquestionably to belong on it. There were another six on a list of possibilities for the final two slots. More than in past years, this year gave me a chance to go back and rewatch films I hadn’t seen in a long time, in some cases since graduate school in the 1970s. Some held up well, some not so much. In a few cases, restorations made since my first viewings revealed new strengths in films I remembered from poor prints.

As always, there are films that have been lost but which plausibly could have filled out the list, most notably Ernest Lubitsch’s The Patriot and F. W. Murnau’s 4 Devils.

First, the eight obvious choices, in no particular order apart from #1.

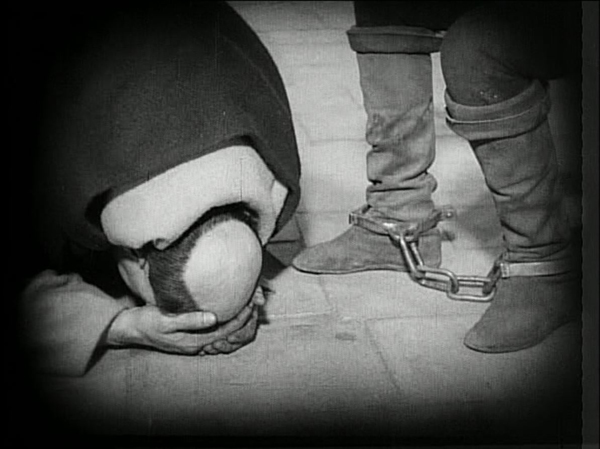

1. La passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Not every year includes a film that is not only one of the tops of its year but of all cinematic history as well. Carl Theodor Dreyer’s final silent film is one such masterpiece.

Jeanne d’Arc seamlessly blended the stylistic traits of the great artistic film movements of the 1920s, German Expressionism, French Impressionism, and Soviet Montage and made something new and unique of them.

Expressionist designer Hermann Warm’s past credits had included two films that have featured in these lists, Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Fritz Lang’s Die müde Tod. Warm collaborated with French theatrical designer Jean Hugo to create spare, white, off-kilter sets that focus our attention on the spiritual drama. Fast editing conveys subjectivity, as in the scenes where Jeanne is threatened with torture and where the citizens are suppressed when they riot after her execution. Rudolph Maté’s cinematography is startlingly dependent on close shots, particularly on the face of Jeanne, played by Renée Falconetti in one of the most intense and affecting performances in any film.

The steady progression of the action condenses days of trial testimony into one apparently continuous story. Between the sets and this inexorable march toward Jeanne’s martyrdom, there is a sense of both spatial and temporal disorientation that focuses our attention intensely on the central conflict.

Until 1981, prints of Jeanne d’Arc were indistinct and incomplete. A pristine print that restored the original visual quality and detail was found in Norway. (The film was among the early ones to be shot on panchromatic film stock without the actors’ using makeup. The result is a detail of texture in the faces that enhances the performances tremendously.) This print is the basis for the Criterion Collection’s edition of the film.

It’s a film that one can see over and over and still be overwhelmed at the originality and intensity of Dreyer’s vision. We saw it projected last November in Houghton, Michigan, with Richard Eichhorn’s recently composed accompaniment, “Voices of Light,” essentially an oratorio and film score rolled into one. We were somewhat trepidatious about whether the score would be distracting, but it proved very effective. Once again, I was reminded of how great this film is. (“Voices of Light” is an optional accompaniment on the Criterion edition linked above.)

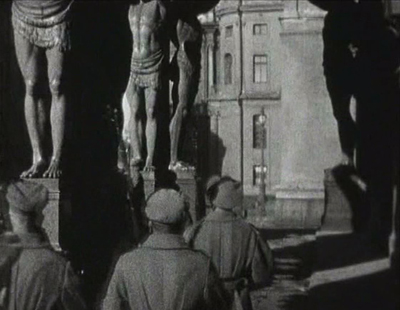

2. October

If Jeanne d’Arc gains intensity through a nearly claustrophobic treatment of space, Sergei Eisenstein creates an epic tenth-anniversary celebration of the 1917 Revolution in his October (finished and released a year late).

Perhaps the most extreme example of Soviet Montage’s frequent avoidance of a single protagonist, October cuts among a wide variety of the people involved in the revolution. Workers pull down a statue of the Tsar. Lenin speaks at Finland Station. Kerensky and his officials luxuriate in their Winter Palace headquarters. Sailors wait on the Aurora battleship. Elderly citizens try to protect the specious February Revolution. Female soldiers are summoned to protect the Palace from the attacking Red forces. Looters steal bottles from the Tsar’s wine-cellar. The result is a sort of patchwork collage of the Revolutionary events leading up to the storming of the Winter Palace and the attack itself, with a slow build to an exultant climax as the Red forces triumph.

Eisenstein was given extraordinary access to the locales of the actual events, so that the vast halls of the Winter Palace and the trappings of royalty (Fabergé eggs and fancy crystal liquor bottles) give a sense of reality rare in fictional reenactments. (There was a time when October was plundered for “documentary” footage of events which had not been recorded by cameras at the time.) He used the settings to ridicule the anti-revolutionary forces, as when young cadets are summoned to help fight the Red forces and are dwarfed by the muscular colossi that line one area of the Palace’s exterior (above).

The film also represents Eisenstein’s experiments with “intellectual montage,” where he attempts to convey ideas strictly through juxtaposing series of images. In belittling the phrase “for God and country,” he tries to reduce the notion of “God” to absurdity by linking a long series of increasingly exotic depictions of deities from different religions.

Whether Soviet audiences of the late 1920s could make anything of such passages is impossible to know for sure, but one suspects that some of them would have been incomprehensible. Still, it is exciting to see an artist playing with such possibilities. Certainly the technique lived on, whether from the simple juxtaposition of cackling hens and gossiping women in Lang’s Fury or Jean-Luc Godard’s dense, often impenetrable strings of images, especially in his political films.

October exists in many versions. Beware the heavily cut versions under the title Ten Days That Shook the World. These images were taken from the 2008 release by the Soviet Ruscico company in its “Kino Academia” series.

3. Spione

Despite the widespread enthusiasm for Lang’s Metropolis, his other big films of the 1920s–Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Die Nibelungen (Siegfried and Kriemhilds Rache), and Spione–seem to me better. Metropolis is perhaps flashier in its design and conception and certainly very entertaining, but it’s also sprawling and implausible and essentially pretty silly.

Spione, on the other hand, has a tight, fast-paced narrative. It’s sort of Dr. Mabuse boiled down to one feature instead of two, and with the villainous Haghi (again played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge) as a banker secretly masterminding a spy ring rather than a gambling racket. There are no great “heart vs. hand” themes here–just a rattling good tale stylishly presented. Expressionism has disappeared in favor of a streamlined look (above), and Lang’s editing has sped up since Mabuse.

There’s not much point in detailing the plot here, since it would involve too many spoilers. Discover it for yourself if you haven’t already.

Spione circulated for years in the truncated American release version, which is how I first saw it. A 2004 Murnau Stiftung restoration of the complete version was a revelation, not only for its more complete narrative but for its superb visual quality. It’s a feast of shots that only Lang could have composed (above and bottom). These frames are from the Eureka! DVD, but the company has subsequently released it in dual format DVD and Blu-ray. Kino Classics has also released it in Blu-ray. The same company has put out a boxed-set of all Lang’s silent films (including Die Pest im Florenz, directed by Otto Rippert from Lang’s script). We were given this recently and haven’t had time to explore it, but it looks like a must for any fan of Lang.

4. L’Argent

Marcel L’Herbier makes his second and final appearance on this annual list with his epic adaptation of Emile Zola’s L’Argent, updated to contemporary Paris. (See the 1921 entry for El Dorado; I also wrote about the Flicker Alley releases of the restored versions of L’Inhumaine [1923] and Feu Mathias Pascal [1925].)

Inspired by Abel Gance’s even more epic Napoléon (1927), L’Herbier set out to make a film that would require a large budget. To obtain that, he made a deal for his own company, Cinégraphic, to co-produce with the mainstream studio, Cinéromans. The result contains brightly lit sets of big banks and expensive apartments, as well as shots made in the Paris Bourse over a three-day weekend (above). L’Argent also had an all-star cast. It included Brigitte Helm and Alfred Abel fresh off Metropolis, thanks to the German distributor, UFA. It also meant that Cinéromans tampered with the film, re-editing and shortening it.

Given L’Herbier’s reputation as an aesthete and an avant-garde filmmaker, L’Argent was dismissed by many at the time as a purely commercial endeavor. It remained unseen and hence virtually forgotten for decades. A screening at the New York Film Festival in 1968 surprised and impressed the spectators. The real recognition of the film as a major artwork came, however, in 1973, when critic and theorist Noël Burch published his monograph, Marcel L’Herbier (Paris: Seghers, 1973). In it he hailed L’Argent as a masterpiece, devoting the entire final chapter to an analysis of it. Burch also wrote the entry on L’Herbier for Cinema: A Critical Dictionary: The Major Film-makers ([New York: Viking Press, 1980], Vol. Two, pp. 621-28), edited by Richard Roud; again Burch devoted much of his text to L’Argent.

I have expressed my reservations about L’Herbier’s films in earlier entries, but for me L’Argent is the big exception: stylistically daring and narratively engaging. Perhaps adapting Zola led L’Herbier to make a more conventionally suspenseful film than usual. Referring to the French Impressionist movement in general, Burch wrote, “L’Argent undoubtedly marks the end of the period of experimentation, since it is itself the culmination of all these experiments–not just L’Herbier’s, but those of the first avant-garde and even, to a certain extent, of the entire Western cinema (with the exception of the Russians)” (Roud, pp. 624-25).

The story involves two powerful bankers who spar for control of one large bank’s standing on the stock market. One, the villainous Saccard, aims to send a famous aviator on a perilous flight across the Atlantic to promote his bank’s oil holders in Latin America–while seducing the aviator’s wife during his absence. The other, Gundermann, tries to thwart him by buying up shares of his rival’s bank and then selling them to cause a drop in the bank’s value.

In portraying all the complex machinations going on, L’Herbier adopts a restless camera, frequently moving among and around characters rather than following them. The most striking example comes early on, when an underling comes to visit Gundermann and waits in an odd, unfurnished room decorated with a map of the world. As he looks around, the camera circles him until a servant unexpectedly appears through a door and escorts him in.

The odd distortions in these shot exemplify another cinematographic technique that was in increasing use during the late 1920s: conspicuous wide-angle lenses. On the left below, Saccard is nearly dwarfed by one of his telephones, while on the right the scene of the aviator’s departure makes the plane’s wings jut into the foreground and extend far into the background.

There are some subjective moments, carrying forward the tradition of French Impressionism. Yet for the most part the restless camera, the distorting lenses, the odd angles (see the top image of this section), and the unusual crosscutting are not subjective, which makes this an atypical Impressionist film. Instead they suggest the unnatural, disconcerting world of capitalism, of money and those who struggle over it. Perhaps by minimizing character psychology and striving to represent more abstract concepts, L’Herbier briefly carried Impressionism to a more political–and dramatic–level.

In 2008, L’Argent was released on DVD by Eureka! in the UK as a “Special 80th Anniversary 2 x Disc Edition.” The source material was a beautiful fine-grain positive struck from the original negative, with something close to L’Herbier’s original intended cut. It includes Jean Dréville’s Autour de “L’argent,” a 40-minute making-of (surely one of the first of its type), recorded during the original production. The DVD is still in print and is, as far as I know, the only release of this restored version.

5. Steamboat Bill Jr.

This was the first Keaton film I ever saw, and I immediately became a fan. (The director is credited as Charles Reisner, but we all know that Keaton was primarily responsible for the direction of his films of this period.) It’s not as good as The General (what is?), but it beats out The Cameraman, Keaton’s other feature of this year, by a nose.

Keaton plays the dandified son of a gruff steamboat owner. He returns home from school and gets put into working clothes by his father, whose deteriorating steamboat is competing for tourists with a larger, newer boat. Naturally young Bill is in love with the daughter of the other steamboat’s owner. The action mainly consists of Bill, Sr. trying to prevent Bill, Jr. from clandestinely meeting his girlfriend.

There’s lots of humor along the way to the climax, in which a huge storm hits the town. It’s a classic sequence of Keaton pulling variant gags on the situation of being in a high wind (above) and surrounded by collapsing buildings and flying objects. Perhaps Keaton’s most famous, and dangerous, gag comes when he pauses in front of a house’s façade, which tears loose and falls straight down on him–with a window sparing him from being crushed.

Reportedly the top of the frame missed his head by six inches, but we know Keaton was a little crazy in how far he would go for a laugh.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. was the last film Keaton made with his own production company. The Cameraman was made at MGM, and though it is very good, thereafter his career slowly declined after his move to that studio. This will, alas, be the last Keaton film represented in this series.

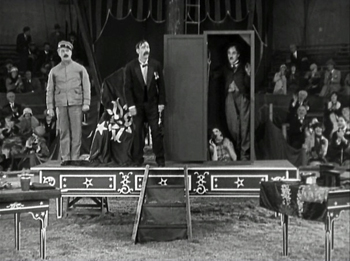

6. The Circus

Coincidentally, The Circus was the first Chaplin film I ever saw. I happened to take my first film course at the point where Chaplin had re-released The Circus, accompanied by a new musical score he composed himself. (Skip, if you can, the added opening, with Chaplin singing a maudlin song over an excerpt from later in the film.) The re-release was 1969, though I must have seen it in 1970 at Iowa City’s art-house, the Iowa. (Also coincidentally, my father managed the Iowa when he was at the university there on the GI bill in the years immediately after World War II. He was dating my mother at that point, and there she saw Day of Wrath. Hence when David and I became a couple in the mid-1970s, she understood what the book he was currently working on was about. But I digress.)

The print I saw at the Iowa was pristine.

Up to that point, The Circus had been unavailable to most viewers, though I suspect bootleg prints circulated among collectors. It’s among the least known of Chaplin’s features, and it’s still hard to see. There’s a Park Circus DVD available in England, consisting of the re-release version equally in mint condition; that’s the one I’ve taken these illustrations from. More recently the film has been released as a Blu-ray/DVD combination. There is also an Artificial Eye Blu-ray available, which gets high marks from DVD Beaver. I haven’t seen this and don’t know whether it’s the re-release version or the original.

Chaplin plays his Little Tramp character, introduced wandering around the sideshow attractions near a circus. Mistaken for a pickpocket, he flees among the booths, occasioning a brilliantly staged triple scene in a hall of mirrors. When he first enters it, he is alone and struggles to figure out how to exit. A short time later, pursued by the pickpocket, the two stumble into the room, and a comic chase ensues (above). Finally, a cop is chasing Charlie, who tries to confuse him by luring him into the mirror maze. It’s a set of gags that builds, with the figures popping unexpectedly into the foreground when we had assumed that the real actors were in the depth of the shot. Each scene in the maze is handled in a single take from the same camera setup.

The flight from the cop leads the Tramp into a failing circus cursed with a group of highly unfunny clowns. Charlie inadvertently and unwittingly becomes a sensation for his antics, including his invasion of a magician’s act.

The cruel circus owner hires him, supposedly as a prop man, and the show becomes a huge success. Charlie falls for the maltreated daughter of the owner, who in turn becomes smitten by a handsome tightrope walker. Trying to impress the daughter, the Tramp goes on when the tightrope walker fails to show up one day. The result is a classic extended scene of Charlie on the high wire, executing a series of comic moments before the whole thing is topped off by a group of monkeys who escape and end up swarming over him as he struggles to keep his balance.

I hope now that The Circus is becoming more available, it can takes its place beside Chaplin’s other features.

[December 29: Thanks to Valerio Greco for alerting me that a restoration of the original version of The Circus is underway in Bologna, to be released by The Criterion Collection.]

7. The Docks of New York

I’ve already written about this, Josef von Sternberg’s final silent feature, in 2010 on the occasion of The Criterion Collection’s release of it alongside Underworld and The Last Command in an essential box-set. The six films von Sternberg made with Marlene Dietrich after she came to Hollywood generally get more attention than any of his silents. If I were allowed three of his films for a proverbial desert-island situation, I would take Underworld, The Docks of New York, and Shanghai Express.

Docks is a concentrated dose of the atmospheric cinematography the director is famous for, in this case employed to create the grungy settings of the film. In the opening, the oil and sweat on the stokers’ bodies (above) is palpable, and the fog, hanging nets and lanterns, and smoke of the dockside sets establish the sleezy, hopeless milieu that drives the heroine to attempt suicide.

Apart from the impressive visuals, the film gains much of its appeal from its two central performances. Betty Compson manages to gain our considerable sympathy for “the Girl” in a remarkably short time, and she has to–the film is only 75 minutes long and she spends her first onscreen appearances unconscious after her near-drowning. George Bancroft, known mostly for supporting roles in westerns, came into his own as the protagonists of three von Sternberg films–including Thunderbolt but not The Last Command. Here he again plays the big lug with a well-hidden heart of gold.

Unfortunately the von Sternberg silents set from The Criterion Collection is out of print. Track it down somewhere or hope for a Blu-ray release.

[December 29: Peter Becker of The Criterion Collection tells me that, although a Blu-ray release is not yet scheduled, there is a good possibility that it will happen.]

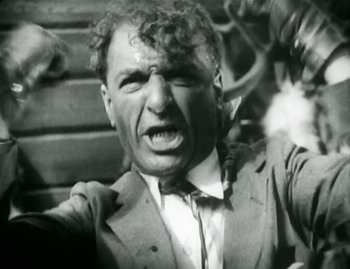

8. Storm over Asia

After Mother and The End of St. Petersburg, Storm over Asia (the original title translates as “The Heir of Genghis Khan”) is the last of Vsevolod Pudovkin’s three great silent features. Unlike the first two, it is set in Mongolia. The Soviet industry officials were concerned to portray the Revolution in the various other countries that along with Russia made up the Soviet Union.

The story takes place during the Civil War years that followed the Revolution. A young Mongolian peasant tries to sell a valuable fox fur at a trading post, but the British dealer cheats him. The peasant strikes him and is forced to flee into the mountains, where he joins the Red partisans fighting the British imperialists. (This does not follow historical fact, since the British occupied parts of Siberia and Tibet, but not Mongolia. In reality, for a brief period in 1921, White Russian forces drove out the Chinese from Mongolia. In response, the Red Army moved in, supporting the Mongols in their quest for independence.)

The British shoot the protagonist but discover on him a document that seems to identify him as the heir of Genghis Khan. So they set him up as a puppet ruler in order to control the local population. Eventually he rebels and leads a storm-like assault that defeats his oppressors.

Storm over Asia uses many of the Soviet Montage devices that by 1928 were fairly conventional. For instance, there are many rapid, rhythmic alternations of shots. When the fur trader reacts angrily against the protagonist’s resistance to being cheated, brief shots of his angry call for troops to capture the young man alternate with shots of a drum being beaten. The final “storm” battle uses rapid montage as well. There is also the usual visual symbolism mocking the enemy, as exemplified by the empty officer’s uniform in the shot above.

Early Montage films tried to do away with a single central character in favor of a focus on the masses. October, for example, has no main hero. In Storm over Asia, though, the story arc is definitely crafted around the Mongol’s growth into a rebellious leader of his people. We will see Eisenstein opting for a central identification figure in Old and New (1929).

My illustrations were taken from the old Image release, apparently no longer available. The Blackhawk print has been released by Flicker Alley.

Those are the eight films I put on my “top” list. I thought of stopping there, but the number ten is sacred for such lists, plus part of the point here is to throw a spotlight on lesser-known films.

I gathered a second group of films that might claim the remaining two slots. These were mostly films that were already hallowed classics when I was in graduate school: King Vidor’s The Crowd, Jean Epstein’s La chute de la maison Usher, René Clair’s The Italian Straw Hat, and Victor Seastrom’s The Wind. Beyond that there were the more recently rediscovered and much admired film, Paul Fejos’ Lonesome and the still little-known The House on Trubnoya, by Boris Barnet.

Oddly, the three American films on this list have some distinct similarities. The Crowd and Lonesome are surprisingly parallel. Lonesome follows two lonely people in New York finding each other and falling in love in one hectic day. The Crowd starts with a somewhat similar situation–both even involve dates at Coney Island–but follows the couple through several years of happy times and misfortune during their marriage. The Wind is less realistic, dealing with a sensitive young woman who travels to the west and, plagued by the incessant wind and a real or imagined rape, slips into madness. All three strive to reject the conventional Hollywood romance. Unfortunately all three, however admirable for most of their plots, lead to abrupt, implausible happy endings.

I saw The Italian Straw Hat in my graduate-school days and found it remarkably unfunny, given its reputation. Returning to it now, I still find the first two-thirds largely devoid of humor. (The dance scenes during the wedding party seem interminable, with no little vignettes or gags among the characters at all.) The last portion picks up, but on the whole it’s hardly the model French farce it is held to be. Certainly Clair made a leap forward in skill and sophistication in his early sound films. (Les deux timides, also 1928, is no doubt a better film.)

The Italian Straw Hat probably owes its classic standing in part to the fact that the Museum of Modern Art acquired and circulated it early on. Curator and critic Iris Barry adored it and lauded it in a 1940 essay (reproduced in the booklet included in the Flicker Alley release.) I wonder how many others of the films considered classics have become so because they were among the few silents available in the decades before the 1960s, when film studies and archival curatorship began to be more comprehensive. Knowing the range of international films we know now, would these films have become quite so highly respected above others? I found myself reluctant simply to fill out my list with old standards. The choice was difficult.

Wanting to avoid carrying on the older canon at the expense of more recently rediscovered films for at least one of my films on this list, I always try to include a little-known but worthy film here. This year there is only one (if you don’t count L’Argent), and that is Barnet’s The House on Trubnoya.

The final slot goes to Epstein’s The Fall of the House of Usher. I have always considered this a somewhat tedious film, but the restoration of the film’s full length and improved visual quality in the Epstein box-set released in 2014 by La Cinémathèque Française makes it far more interesting and effective.

So here is the completion of my list.

9. The House on Trubnoya

Boris Barnet was a member of Lev Kuleshov’s school in the early years after the revolution. He played a major role in Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, and he began directing films on his own with the wonderful serial, Miss Mend. He made more films, and some others may show up in our coming lists. Right now, there’s The House on Trubnoya.

The House on Trubnoya is included in Flicker Alley’s major DVD set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.” (I can’t believe that we didn’t feature this on our blog, but it includes eight major Soviet films of the silent era.) The copy on the back of the box describes Barnet’s film as “often described as one of the best Soviet silent comedies.” I’m not sure that’s a major distinction, though Kote Miqaberidze’s Georgian satire My Grandmother (1929; available on DVD and Fandor’s Amazon streaming site) is quite funny, as is Ivan Pyriev’s The State Functionary (aka The Civil Servant; not, as far as I know, available on home video). But The House on Trubnoya is my favorite among the comedies I’ve seen.

It’s a satire on middle-class citizens’ maltreatment of their servants, though it doesn’t become Soviet-style preachy until well into the story. The film begins by setting up the titular house (on a well-known street in Moscow). We see it via its staircase and landings in the morning, rendered in a vertical view that looks startlingly like an iPhone image (above). It also recalls the seven levels in the staircase elevator shot climbing upward to 7th Heaven, though who knows whether Barnet had seen that by the time he planned his film. The residents of the various apartments emerge to use the communal stairway as a junkyard and work area, dumping trash, splitting firewood, beating curtains, and generally abusing the rules of the building, as one conscientious young Party member points out.

We are introduced to a barber, whose lazy wife makes him do all the chores. Then suddenly we’re with a professional driver with his own car. Just as suddenly we’re watching a peasant girl chase her runaway duck through a maze of traffic and nearly get hit by a tram. As the driver brakes hastily and jumps out to see if she’s hurt, there’s a freeze-frame.

A narrating title declares, “”But wait, we forgot to tell you how the duck ended up in Moscow.” Reverse motion leads to another title, “A day earlier.” A flashback to the heroine’s comic departure from a train station in the middle of nowhere shows the very uncle whom she is going to Moscow to visit arriving at the station just after she has left. Finding herself lost in Moscow with her duck, the heroine gains employment as a put-upon maid serving the barber and living in the house on Trubnoya. Her political awakening and the rehabilitation of the House on Trubnoya form the rest of the plot.

The House on Trubnoya is, in short, an imaginative, clever, and funny Soviet Montage film. Barnet’s other films are worth exploring as well. Check out The Girl with the Hatbox from 1927; it didn’t make last year’s top items, but it was on the long list.

10. La Chute de la maison Usher

Jean Epstein, who was probably the finest of the French Impressionist directors, has figured in these ten best lists before, in 1923 for Cœur fidèle, in 1924 for the little-known L’affiche, and 1927 for his masterly La Glace à trois faces.

I have long considered La Chute de la maison Usher interesting for its use of German Expressionist-inspired sets, but the fuzzy, incomplete prints that for decades were the only available versions made it difficult to enjoy. The restored version on the complete DVD set of Epstein’s works, which I discussed here, makes it far more interesting.

Taking its slim plot from Poe, the film follows a visit by an elderly man to the isolated castle of his old friend, Roderick Usher. Usher is painting a portrait of his beloved wife, but it is soon made clear that each time he presses the brush to the canvas, a little of her life is drained away–though the local doctor is mystified by her decline.

The film retains some of the traits of Impressionism, as when Madeline’s reaction to the effects of her husband’s painting are rendered in a superimposition of negative and positive images of her face.

The film has a minimal plot, but its focus is largely on experimentation in creating an eerie atmosphere. Shots of books falling in slow motion from their shelves, of curtains blowing in a cold wind that seems perpetually to invade the house, of frogs copulating in a nearby pond, and of the Expressionist-derived decors contribute less to a linear plot than to a mood of undefined menace.

The castle’s exterior is represented by obvious cardboard models, which tends to undermine the effect created by the interiors. The cheapness of these models is particularly noticeable in the climactic scene of the destruction of the house. This is unfortunate, but one must give Epstein credit for having done so much with so little.

This will be Epstein’s final appearance in our “Ten Best” lists, but I would like to call attention to his other 1928 film, Finis Terrae, the first of what the Epstein box-set collects as his “Poémes Bretons.” These are less Impressionistic, though Finis Terrae has a few impressive subjective shots. They are more realistic and poetic, largely involving the sea.

As I wrote at the beginning, 1928 was part of the period when the American industry was on the cusp of making sound standard in its films. Other national cinemas followed at various paces. One film that did not quite make my top-ten list demonstrates what must have worried film theorists and critics–and no doubt some filmmakers.

The restored version of Lonesome includes some dialogue sequences in a film otherwise accompanied by recorded music. There is an enormous contrast between the silent and sound footage. The story is largely told visually, but the dialogue scenes, clearly done in a sound-proof studio, are delivered in a stilted fashion by the young actors who are otherwise so casual and lively. The prospect of whole films being made in that fashion clearly disturbed lovers of films like La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Steamboat Bill, Jr. Watching Lonesome gives a dramatic insight into this slice of cinema history–a period that fortunately lasted only a few years as the technology improved and as filmmakers increasingly managed to make sound films that were just as imaginative, artistic, and engrossing as their silent predecessors.

January 6, 2019: Thanks to Docks of New York fan Tony Lucia for a correction on that section.

Spione