Archive for the 'Directors: Panahi' Category

Stuck inside these four walls: Chamber cinema for a plague year

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Privacy is the seat of Contemplation, though sometimes made the recluse of Tentation… Be you in your Chambers or priuate Closets; be you retired from the eyes of men; thinke how the eyes of God are on you. Doe not say, the walls encompasse mee, darknesse o’re-shadowes mee, the Curtaine of night secures me… doe nothing priuately, which you would not doe publickly. There is no retire from the eyes of God.

Richard Brathwaite, The English Gentlewoman (1631)

DB here:

We’re in the midst of a wondrous national experiment: What will Americans do without sports? Movies come to fill the void, and websites teem with recommendations for lockdown viewing. Among them are movies about pandemics, about personal relationships, and of course about all those vistas, urban or rural, that we can no longer visit in person. (“Craving Wide Open Spaces? Watch a Western.”)

Cinema loves to span spaces. Filmmakers have long celebrated the medium’s power to take us anywhere. So it’s natural, in a time of enforced hermitage, for people to long for Westerns, sword and sandal epics, and other genres that evoke grandeur.

But we’re now forced to pay more attention to more scaled-down surroundings. We’re scrutinizing our rooms and corridors and closets. We’re scrubbing the surfaces we bustle past every day. This new alertness to our immediate surroundings may sensitize us to a kind of cinema turned resolutely inward.

Long ago, when I was writing a book on Carl Dreyer, I was struck by a cross-media tradition that explored what you could express through purified interiors. I called it “chamber art.” In Western painting you can trace it back to Dutch genre works (supremely, Vermeer). It persisted through centuries, notably in Dreyer’s countryman Vilhelm Hammershøi (below).

Plays were often set in single rooms, of course, but the confinement was made especially salient by Strindberg, who even designed an intimate auditorium. For cinema, the major development was the Kammerspielfilm, as exemplified in Hintertreppe (1921), Scherben (1921), Sylvester (1924), and other silent German classics. Kristin and I talk about this trend here and here.

In the book I argued that Dreyer developed a “chamber cinema,” in piecemeal form, in his first features before eventually committing to it in Mikael (1924) and The Master of the House (1925). Two People (1945) is the purest case in the Dreyer oeuvre: A couple faces a crisis in their marriage over the course of a few hours in their apartment. (Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem available with English subtitles.) But you can see, thanks to Criterion, how spatial dynamics formed a powerful premise of his later masterpieces Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964).

Dreyer wasn’t alone. Ozu tried out the format in That Night’s Wife (1930), swaddling a husband, wife, child, and detective in a clutter of dripping laundry and American movie posters.

Bergman exploited the premise too, in films like Brink of Life (1958), Waiting Women (1952), his 1961-1963 trilogy, and Persona (1966). (All can be streamed on Criterion.)

Chamber cinema became an important, if rare expressive option for many filmmaking traditions. Writers and directors set themselves a crisp problem–how to tell a story under such constraints?

The challenge is finding “infinite riches in a little room.” How? Well, you can exploit the spatial restrictiveness by confining us to what the inhabitants of the space know. Limiting story information can build curiosity, suspense, and surprise. You can also create a kind of mundane superrealism that charges everyday objects with new force.

On the other hand, you need to maintain variety by strategies of drama and stylistic handling. Chamber cinema–wherever it turns up–offers some unique filmic effects, and maybe sheltering in place is a good time to sample it.

Herewith a by no means comprehensive list of some interesting cinematic chamber pieces. For each title, I link to streaming services supplying it.

Bottles of different sizes

From David Koepp I learned that screenwriters call confined-space movies “bottle” plots. There’s a tacit rule: The audience understands that by and large the action won’t stray from a single defined interior. In a commentary track for the “Blowback” episode of the (excellent) TV show Justified, Graham Yost and Ben Cavell discuss how TV series plan an occasional bottle episode, and not just because it affords dramatic concentration. It can save time and money in production.

Usually the bottle consists of more than a single room. The classic Kammerspielfilms roam a bit within a household and sometimes stray outdoors. But their manner of shooting provides a variety of angles that suggest continuing confinement. Dreyer went further in The Master of the House. He built a more or less functioning apartment as the set, then installed wild walls that let him flank the action from any side. Then editing could provide a sense of wraparound space.

The variations in camera setups throughout the film are extraordinary. Dreyer would create more radically fragmentary chamber spaces in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), while his later films would use solemn, arcing camera movements to achieve a smoother immersive effect. (For more on Dreyer’s unique spatial experimentation, here’s a link to my Criterion contribution on Master of the House. I talk about the tricks Dreyer plays with chamber space in Vampyr in an “Observations” supplement on the Criterion Channel.)

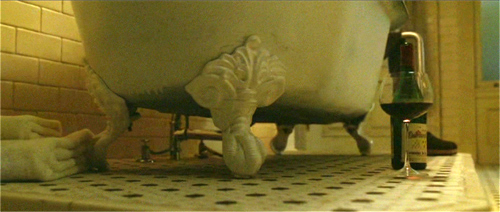

Likewise, Koepp’s screenplay for Panic Room allows David Fincher to move 360 degrees through several areas of a Manhattan brownstone. The film also offers a fine example of how our awareness of domestic details gets sharpened by a creeping camera.

Trust Fincher to find sinister possibilities in a dripping bathtub leg and a kitchen island.

Confined to quarters

Detective Story (1951).

Many chamber movies are based on plays, as you’d expect. Unlike most adaptations, though, they don’t try to “ventilate” the play by expanding the field of action. Or rather, as André Bazin pointed out, the expansion is itself fairly rigorous. They don’t go as far afield as they might.

Bazin praised Cocteau’s 1948 version of his play Les parents terribles (aka “The Storm Within”) for opening up the stage version only a little, expanding beyond a single room to encompass other areas of the apartment. This retained the claustrophobia, and the sense of theatrical artifice, but it spread action out in a way that suited cinema’s urge to push beyond the frame. The freedom of staging and camera placement is thoroughly “cinematic” within the “theatrical” premise.

Depending on how you count, Hitchcock expanded things a bit in his adaptation of Dial M for Murder. Apart from cutting away to Tony at his club, Hitchcock moved beyond the parlor to the adjacent bedroom, the building’s entryway, and the terrace.

An earlier entry on this site talks about how 3D let Sir Alfred give an ominous accent to props: a particularly large pair of scissors, and a more minor item like the bedside clock.

Hitchcock gave us a parlor and a hallway in Rope (1948), but when Brandon flourishes the murder weapon, the framing audaciously reminds us that we aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen.

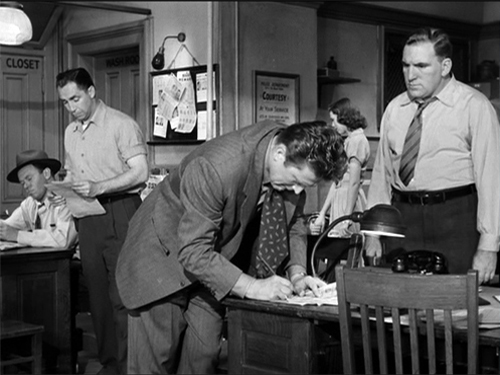

Bazin did not wholly admire William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951), despite its skill in editing and performances; he found it too obedient to a mediocre play. True, the film doesn’t creatively transform its source to the degree that Wyler’s earlier adaptation of The Little Foxes (1941) did; Bazin wrote a penetrating analysis of that film’s remarkable turning point. Detective Story is more obedient to the classic unities, confining nearly all of the action to the precinct station. Although I don’t think Wyler ever shows the missing fourth wall, he creates a dazzling array of spatial variants by layering and spreading out zones of the room. In his prime, the man could stage anything fluently.

As Bazin puts it: “One has to admire the unequaled mastery of the mise-en-scène, the extraordinary exactness of its details, the dexterity with which Wyler interweaves the secondary story lines into the main action, sustaining and stressing each without ever losing the thread.”

Some films are even more constrained. 12 Angry Men (1957), adapted from a teleplay, is a famous example. Once the jury leaves the courtroom, the bulk of the film drills down on their deliberation. Again, the director wrings stylistic variations out of the situation; Lumet claims he systematically ran across a spectrum of lens lengths as the drama developed.

But you don’t need a theatrical alibi to draw tight boundaries around the action. Rear Window (1954), adapted from a fairly daring Cornell Woolrich short story, is as rigorous an instance of chamber cinema as Rope. Here Hitchcock firmly anchors us in an apartment, but he uses optical POV to “open out” the private space.

With all its apertures the courtyard view becomes a sinister/comic/melancholy Advent calendar.

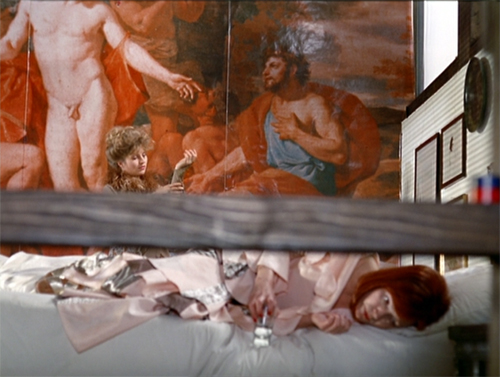

Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) denies us this wide vantage point on the outside world. This space seems almost completely enclosed. But Fassbinder finds a remarkable number of ways to vary the set, the camera angles, and the costumes. We’re immersed in the flamboyant flotsam of several women’s lives. The result is a cascade of goofily decadent pictorial splendors.

It’s virtually a convention of these films to include a few shots not tied to the interiors. At the end, we often get a sense of release when finally the characters move outside. That happens in 12 Angry Men, in Panic Room, in Polanski’s Carnage (2011) , and many of my other examples. Without offering too many spoilers, let’s say Room (2015) makes architectural use of this option.

On the road and on the line

Filmmakers have willingly extended the bottle concept to cars. The most famous example is probably Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), which secures each scene in a vehicle and mixes and matches the passengers across episodes. The strictness of Kiarostami’s camera setups exploit the square video frame and always yield angular shot/reverse shots. They reveal how crisp depth relations can be activated through the passing landscape or in story elements that show up in through the window.

Perhaps Kiarstami’s example inspired Danish-Swedish filmmaker Simon Staho. His Day and Night (2004) traces a man visiting key people on the last day of his life, and we are stuck obstinately in the car throughout. This provides some nifty restriction, most radically when we have to peer at action taking place outside.

Staho’s Bang Bang Orangutang (2005), a portrait of a seething racist, takes up the same premise but isn’t quite so rigorous. We do get out a bit, but the camera stays pretty close to the car. I discuss Staho’s films a little in a very old entry.

Like autos, telephones provide a nice motivation for the bottle, as Lucille Fletcher discovered when she wrote the perennial radio hit, “Sorry, Wrong Number.” The plot consists of a series of calls placed by the bedridden woman, who overhears a murder plot. The film wasn’t quite so stringently limited, but the effect is of the protagonist at the center of several crisscrossed intrigues.

A purer case is the Rossellini film Una voce umana (1948), in which a desperate woman frantically talks with her lover. It relies on intense close-ups of its one player, Anna Magnani.

It’s an adaptation of a Cocteau play, which Poulenc turned into a one-act opera. In all, the duration of the story action is the same as the running time.

I wish Larry Cohen’s Phone Booth displayed a similarly obsessive concentration, but we do have the Danish thriller The Guilty, where a police dispatcher gets involved in more than one ongoing crime. We enjoyed seeing it at the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival.

And of course car and phone can be combined, as they are in Locke (2013)–another play adaptation. Tom Hardy plays a spookily calm businessman driving to a deal while taking calls from his family and his distraught mistress. Those characters remain voices on the line while he tries to contend with the pressures of his mistakes.

House arrest, arresting houses

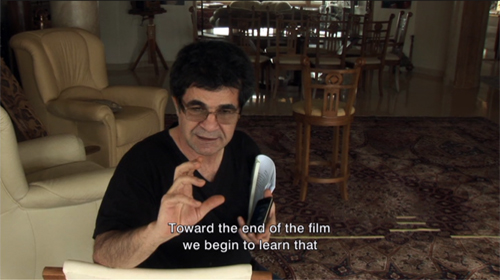

Sometimes you must embrace the chamber aesthetic. In 2010 the fine Iranian director Jafar Panahi was forbidden to make films and subjected to house arrest. Yet he continued to produce–well, what? This Is Not a Film (2012) was shot partially on a cellphone within (mostly) his apartment.

Wittily, he tapes out a chamber space within his apartment. Then he reads a script to indicate how absent actors could play it and how an imaginary camera could shoot it.

But his imaginary film still isn’t an actual film, so he hasn’t violated the ban. So perhaps what we have is rather a memoir, or a diary, or a home video? Panahi’s virtual film (that isn’t a film) exists within another film that isn’t a film. Yet it played festivals and circulates on disc and streaming. The absurdity, at once touching and pointed, suggests that through playful imagination, the artist can challenge censorship.

Panahi slyly pushed against the boundaries again with Closed Curtain (2013, above). Shot in his beach house, it strays occasionally outside. Next came Taxi (2015), in which Panahi took up the auto-enclosed chamber movie, with largely comic results.

More recently, he has somehow managed to make a more orthodox film, 3 Faces (2018), which considers the situation of people in a remote village.

The chamber-based premise needn’t furnish a whole movie. As in Room, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) is tightly concentrated in its first half. We are in two enclosures, a house and a train. The film then bursts out into a rushed, wide-ranging investigation. Large-scale or less, the chamber strategy remains a potent cinematic force.

They say that the last creatures to discover water will be fish. We move through our world taking our niche for granted. Cinema, like the other arts, can refocus our attention on weight and pattern, texture and stubborn objecthood. We can find rich rewards in glimpses, partial views, and little details. Chamber art has an intimacy that’s at once cozy and discomfiting. Seeing familiar things in intensely circumscribed ways can lift up our senses.

So take a break from the crisis and enjoy some art. But return to the world knowing that for Americans this catastrophe is the result of forty years of monstrous, gleeful Republican dismantling of our civil society. Rebuilding such a society will require the elimination of that party, and the career criminal at its head, as a political force. This pandemic must not become our Reichstag fire.

Yeah, I went there.

Thanks to the John Bennett, Pauline Lampert, Lei Lin, Thomas McPherson, Dillon Mitchell, Erica Moulton, Nathan Mulder, Kat Pan, Will Quade, Lance St. Laurent, Anthony Twaurog, David Vanden Bossche, and Zach Zahos. They’re students in my seminar, and they suggested many titles for this blog entry.

Bazin’s comments on Detective Story come in his 1952 Cannes reportage, published as items 1031-1033, and as a review (item 1180), in Écrits complets vol. I, ed. Hervé Joubert-Laurencin (Paris: Macula, 2018), pp. 918-922, 1059. My quotation comes come from the review, where he does grant that Wyler is the Hollywood filmmaker “who knows his craft best. . . . the master of the psychological film.”

The tableau style of the 1910s probably helped shift Dreyer toward the chamber model, which he learned to modify through editing. I discuss Dreyer’s relation to that style in “The Dreyer Generation” on the Danish Film Institute website. Also related is the web essay, “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic.”

Some other examples could be mentioned, but I didn’t find them on streaming services in the US. It would be nifty if you could see the tricks with chamber space in Dangerous Corner (1934); fortunately it plays fairly often on TCM. There’s also Duvivier’s Marie-Octobre (1959), a tense drama about the reunion of old partisans.

I especially like the 1983 Iranian film, The Key, directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and scripted by Kiarostami. It’s a charming, nearly wordless story of how a little boy tries to manage household crises when Mother is away. It has the gripping suspense that is characteristic of much Iranian cinema, and the boy emerges as resourceful and heroic (though kind of messy). Kids would like it, I think.

Also, I’ve neglected Asian instances. Maybe I’ll revisit this topic after a while.

P.S. 1 April 2020: Thanks to Casper Tybjerg, outstanding Dreyer scholar, for corrections about the nationality of The Guilty and the Staho films.

Gertrud (1964).

Vancouver 2018: A final few films

Kristin here:

As I write, David and I have been at home after the Vancouver International Film Festival for one week. Between Venice and Vancouver, I saw about 40 films, some of them likely awards competitors for the year and some more modest works that need to be sought out at festivals and big-city art-houses. (Today, in a cyclical gesture, we’re going back to the very first film we saw at Venice, First Man, this time in IMAX.)

During any festival there’s never time enough to write up comments on all the films we see. This is our last report on the 2018 Vancouver event, this time dealing with Middle Eastern films and one from South America.

3 Faces (Jafar Panahi, 2018)

3 Faces begins startlingly, with a vertical cell-phone image of a girl in a rocky area, dictating a suicide note as she walks. She identifies herself as Marziyah, a peasant girl who aspires to be study acting but whose conservative family (along with their entire village) have blocked her from doing so. She has written repeatedly to a famous TV actress, Behnaz Jafari (played by herself) for help, but receiving no response, she has decided to kill herself. The recording ends as the girl apparently hangs herself and the camera falls.

The image opens to fullscreen as Jafari, riding in a car with Panahi, watches the recording, distraught at the possibility that she has failed to help the girl. She also wonders whether Marziyah has really killed herself. Was the film edited to create that impression? Panahi thinks it looks authentic, and he drives Jafari out to the girl’s village to find out.

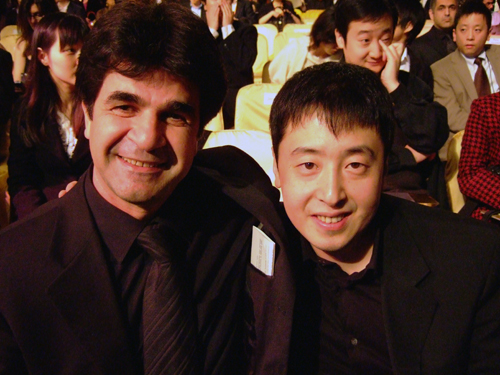

3 Faces is the fourth feature Panahi has made since his trial in 2010 and the resulting sentence banning him from filmmaking for twenty years. We had been following his career before that, most notably with The Circle and Offside. In happier days, David met Panahi briefly at the Hong Kong Film Festival, when they sat next to each other at an award ceremony. David posted an account of Panahi’s charges and sentencing in 2010. We have also written about films that Panahi has made since then: This Is Not a Film and Closed Curtain. Somehow, though we saw Taxi, we didn’t blog about it. Today Panahi remains unable to leave Iran to attend the festivals where his films are honored (3 Faces won the best-screenplay award at Cannes), and he has no access to studio facilities.

With 3 Faces, Panahi has moved on from making films about his plight and looks at the repression suffered by women and girls in the rural areas of Iran.

This time he follows the classic quest pattern of many of the golden age of Iranian cinema from the 1980s to the early 2000s. 3 Faces is perhaps most reminiscent of Kiarastami’s And Life Goes On, another director’s journey to the countryside to check on a child who may have died. It’s gratifying to see the fruitful quest pattern revived, and Panahi creates a work that is at once familiar and uniquely imaginative. The settings, mostly in Panahi’s car and the countryside of Iran near the Turkish border.

As in other such films, 3 Faces is as much about the unexpected encounters with strangers along the way: a wedding group celebrating on a steep mountain road, a woman testing out her own grave to make sure it’s comfortable, an old man who introduces Panahi to the patterns of honks locals use when approaching each other on the narrow roads. Upon reaching the village and encountering Marziyah’s family, it becomes apparent that they are baffled and annoyed by the girl’s ambitions to devote herself to a frivolous career rather than marry and settle down.

Jahari also encounters a retired actress from before the 1979 revolution, Shahrazade, now a recluse living in a tiny house near the village (see top). The “3 Faces” title apparently refers to the three generations of actresses, Shahrazade, Jafari, and Marziyah. This explanation is not apparent from the film, especially since Shahrazade is glimpsed only in extreme long shot from the back as she paints in a field.

Panahi has made a more acerbic film than those of Kiarostami, poking fun at the villages and especially emphasizing the way the men are obsessed with virility and controlling their womenfolk. Receding into the background despite his major role, Panahi takes p the feminism he displayed in Offside and reveals the more serious lack of freedom women and girls experience in rural areas. He does so without abandoning the humor that underlies many of the quest films.

Kino Lorber will distribute the film in the US, with a release planned for March, 2019.

Dressage (Pooya Badkoobeh, 2018)

Another trend in recent Iranian cinema might be termed the Farhadi effect. Asghar Farhadi has become the most prominent of the current group of Iranian directors, winning best foreign-language Oscars for both A Separation and The Salesman. His films tend to center around a serious mistake or a crime committed early on, with the varying reactions of the characters forming the bulk of the drama. In some cases sudden twists reveal motivations that tend to make the situation more ambiguous morally, and the rights and wrongs of the situation do not resolve clearly.

Dressage, Badkoobeh’s first feature, fits this pattern to some degree. A group of middle-class and upper-middle-class students are in the habit of robbing shops for thrills. As the film opens, they have robbed a small grocery store. When a clerk who lives in the store unexpectedly interrupts them, their leader knocks him out. Having fled, the group discovers that they have neglected to take the incriminating surveillance tape with them. The protagonist, sixteen-year-old Golsa, is sent back for it. Having retrieved it, she hides it in a bin at the stables where she helps take care of expensive dressage horses (above).

Golsa refuses to turn over the tape, either to the group or to her parents, all of whom wish to destroy the evidence. What Golsa plans to do with the tape is unclear, but she is subjected to more and more pressure to give it up. Along the way, her stubbornness begins to harm the very working-class people, such as the store clerk, whom she hopes to help.

The rather simple story is given some depth by Golsa’s love for one of the dressage horses. It’s made clear that such horses are valuable and must be exercised without letting them run free, which would risk damage to their legs, but at one point she takes her favorite into a field to frolic about.

Ultimately the film has less of the complexity and ambiguity of a Farhadi film, but it shows promise for a younger generation of Iranian filmmakers.

As far as I can determine, Dressage does not have a North American distributor.

Caphernaüm, aka Capernaum (Nadine Labaki, 2018)

I remember that during the Cannes festival, Kore-eda’s Shoplifters and Labaki’s Capernaum were among the films most often predicted to win the Palme d’Or. In the event, Shoplifters took the top prize, and justifiably so, and Capernaum received the Jury Prize, the second highest honor. Both films center around families living in poverty, though Shoplifters moves among the members of its family and emphasizes their mutual support. Capernaum, on the other hand stays resolutely with Zain, the 12-year-old boy who is so miserable that he takes his parents to court to sue them for having brought him into a wretched existence in the Beirut slums.

Labaki, determined to expose the reasons for the sufferings of children in the poorer areas of Beirut, spent three years researching the subject. She cast actual slum-raised children rather than actors and coaxed remarkable performances from them. It seems absurd to speak of a performance from the one-year-old girl who plays Yonas, the little boy whom Zain struggles to care for when the toddler’s Ethiopian-emigré mother is arrested for lack of proper papers; still, the child seems always to be doing exactly what is natural and appropriate for the situation. The result of working with non-professionals and children was 500 hours of footage to be edited down into a two-hour film. (The production information is from an interview with Labaki in The Hollywood Reporter.)

It seems churlish to find fault with Capernaum, which certainly must be given credit for exposing a side of life that most viewers will never witness. It mixes humor and pathos with a deft hand and is undoubtedly entertaining and thought-provoking. Yet there are moments when the film’s effort to tug at our heartstrings seems a bit too obvious and overdone. Some critics have been unqualifiedly moved by the film, while others find it a bit too manipulative. I suspect that most audiences who see it in art-houses in the US will share the reaction of the Cannes audience, who gave it a 15-minute standing ovation.

The meaning of the film’s title is intriguing, and some clarification might be helpful. I have given both its original Lebanese title, Capharnaüm, and the one used in English-speaking countries, Capernaum. They are variant spellings of the same word, but with different meanings. “Capharnaüm” is French and means “a confused jumble” or “a place marked by a disorderly accumulation of objects” (Merriam-Webster). It derives from the Aramaic spelling of the Hebrew name Capernaum, the village on the Sea of Galilee where Jesus is said in the Bible to have been based during most of his ministry.

The “confused jumble” derives from the large crowds that flocked around Jesus, as in Mark: 1-2:

And again he entered into Capernaum after some days, and it was noised that he was in the house.

And straightaway many were gathered together, insomuch that there was no room to receive them, no, not so much as about the door; and he preached the word unto them.

Labaki, being a Catholic (belonging to the Lebanese Maronite Church and having been educated at St. Joseph University in Beirut), would surely have been aware of both these meanings when she made her film. The notion of a crowded jumble applies well to the environments in which the children in the film live. Certainly the children belong to the downtrodden classes to whom Jesus ministered. Possibly the reference to Jesus’ miracles, several of were reportedly performed in Capernaum, helps to justify the implausibly upbeat ending of the film.

Capernaum will be released in the US by Sony Pictures Classics on December 14.

Birds of Passage (Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, 2018)

Birds of Passage is the first film directed by Ciro Guerra since his excellent Embrace of the Serpent, which was the first Colombian film nominated for a foreign-language Oscar. This time he co-directs with his wife and producer, Cristina Gallego.

Birds of Passage is a very different film from Embrace of the Serpent. The latter is set in the Colombian Amazon region, focuses on the decimation of indigenous peoples by the rubber trade, is shot in black and white, and cuts between two time periods decades apart involving two explorers guided by the same indigenous guide. Birds of Passages is set in a desert region of northern Colombia, deals with the early effects of drug-trafficking among the Wayuu people of the area, is shot in color, and follows a single extended family chronologically through five periods between the 1960s and 1980s, each announced by a dated title.

The result is a plot that is much easier to follow than that of Embrace of the Serpent. While the earlier film was based around the evocative, mysterious hunt through the jungle for a fictional sacred plant, Birds of Passage is very much anchored in the history of the early marijuana trade that the central family becomes involved in, growing very rich in the process.

In the film, the first American customers who draw the ambitious hero, Raphayet, to obtain a small amount of marijuana for them are some Peace Corps volunteers. Soon criminal traffickers become customers for Raphayet’s wares, and the roughly two decades of drug-running that follow balloon into a business that ends with a war within the family (see bottom).

The title refers to a motif that is introduced in the opening scene, when teenage Zaida, of the foremost family among the Wayuu, finishes her official transition to womanhood with a ritual dance based on bird mating rituals. Raphayet offers to dance with her (above), and the task of meeting her mother’s high dowry price includes him making his first small drug deal. The motif of real birds continues, but migrating “birds of passage” is also a local term for the American traffickers who fly in and out in small planes, bringing money in such large bundles that have to be weighed rather than counted.

As a film, Birds of Passage is not as challenging or evocative as Embrace of the Serpent. Its fascinating story, however, deals with the little-known history of the origins of the South American drug trade, the growing problem that has caused such upheaval in the region and is very much still with us.

The Orchard has the US rights, with no announced release date.

Returning for a moment to the Venice International Film Festival, three publications generated by the 2018 festival are now available for sale.

Two of these publications result from the festival’s 75th anniversary this year. Peter Cowie’s Happy 75º: A Brief Introduction to the History of the International Film Festival offers a succinct, chronological account of the festival’s facilities, organizers, guests, and winners year by year. Reading it enlivened the time spent in line before films for both David and me.

The festival also presented a large exhibition of photographs, again presented year by year, celebrating the films shown and the stars attending. This exhibition was mounted in the legendary Hotel des Bains, closed in recent years but formerly housing many of the festival’s glamorous guests. It is mainly connected in the minds of most moviegoers with Visconti’s Death in Venice, which was filmed there. There are plans to renovate and re-open it. A large catalog containing what appear to be all the photographs from the exhibition has also been published.

Finally, this year’s program, with extensive notes on the films, is available.

All of these can be ordered from amazon.it. The program can also be downloaded.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help during our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Birds of Passage

Familiar Middle-Eastern filmmakers return to VIFF

Closed Curtain (2013).

Kristin here:

Two years ago David and I wrote about a group of Iranian and Israeli films that featured prominently in the 2011 VIFF program. This year’s program boasted several more, many of them by the same directors.

Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partovi, 2013)

Despite still being banned from filmmaking and forbidden to leave Iran, Panahi has followed This is Not a Film with another fascinating feature that has made its way abroad. This time he co-directs with Kambuzia Partovi, who also plays one of the main characters, a screenwriter.

The writer flees to a seaside house (apparently Panahi’s) to hide his dog from a roundup of animals deemed “unclean” under Islam. Once ensconced, the writer tries to conceal his pet by sealing the many large windows with opaque curtains. Eventually their privacy is invaded by another refugee, a young woman sought by local police for participating in a nearby party.

This first section of the film seems to be a straightforward allegory for Panahi’s own situation, but well after the midpoint, Panahi himself appears and takes over as the main character. With the curtains removed, he stares at the pond behind the house, seemingly having a vision of himself amid the beauties of nature. He also gazes at the sea in front of the house, envisioning himself walking into it to commit suicide.

The opening stretches emphasize suspense, when the writer hears voices and sirens outside, and unseen officials hammer against the door. The result is an image of the creative artist forced to conceal himself from forces of authority. With Panahi’s appearance, the film becomes more subjective than allegorical, and the abrupt juxtaposition of the two parts of the film create a puzzling whole. But that whole is rigorously filmed and arouses interest throughout.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn (Mohammad Rasoulof, 2013)

In 2010, I posted about Rasoulof’s beautiful film, The White Meadows (2009), an overtly allegorical film about the sufferings of various sectors of Iranian society. At that point I wrote, “He was arrested alongside Jafar Panahi (who edited The White Meadows) and about a dozen others on March 2. Fortunately he was released fairly soon, on March 17. What his future as a director in Iran is remains to be seen.” Most immediately, he was given a prison sentence and banned from filmmaking. Neither condition evidently kept him from finishing the impressive Goodbye (2011), which I discussed here. More recently, upon returning to Iran from Europe, Rasoulof has had his passport seized and is unable to travel or to reunite with his family. Most observers believe that this treatment is a response to his harshly critical new film, Manuscripts Don’t Burn, which has attracted attention at several festivals.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn differs considerably from The White Meadows. There is no hint of allegory here as Rasoulof examines the state surveillance system.The plot centers around two dissident authors and their strategies for hiding their manuscripts and evading the authorities. While a ruthless, educated young official decides on two authors’ fates, two working-class men carry out the kidnapping, torture, and murders that he orders. The hitmenare seen as victims themselves, as one of them, trying to pay medical bills for a sick child, continually finds that his last job’s payment has not yet been transferred to his bank account. They endure stakeouts in chilly weather and grab takeout food on the fly. The whole film is shot in muted tones (in both Tehran and Hamburg) and conveys a sense of unrelenting grimness.

The plot is drawn from unspecified real-life events, and the film cautiously carries no credits for cast or crew. (For more information on the film’s background, see Stephen Dalton’s informative review from the film’s premiere at Cannes.)

The Past (Asghar Farhadi, 2013)

Since A Separation (2012; see our entry here) became the first Iranian film to win an Oscar for best foreign-language film, Farhadi has become the most prominent director working in that country. This is witnessed by the fact that his new film, The Past, has been put forth as Iran’s candidate for this year’s Academy nomination.

The plot of the new film draws upon familiar strategies that created a strong, moving situation in A Separation. Again a husband and wife are on the brink of divorce. In this case, the husband, Ahmad, is Iranian, and the wife, Marie is French. Clearly they had lived together for a time in France, since when Ahmad arrives from Tehran, he knows how to get around Paris. Marie has two daughters from a previous marriage and plans to marry the small-businessman Samir, by whom she is pregnant. Samir has a morose young son who resists the idea of having Marie as a mother.

With this larger cast of characters, disagreements and obstacles pile up. Marie is extremely strict and strong-willed. Her older daughter is rebellious and stays out late. Ahmad tries to mediate between Samir’s miserable son and Marie’s scolding, while Samir tries to please Marie and still help his son adjust to the upcoming marriage.

As in A Separation, The Past builds up a mystery about an unhappy event. Samir’s wife has attempted suicide. What led her to this desperate measure? Her chronic depression? An embarrassing argument with one of Samir’s customers? Or did she know of Samir’s affair with Marie? Ahmad’s attempts to solve this mystery provide a strong, intriguing subplot alongside the shifting conflicts among the main adult characters.

With so many characters involved, the accumulation of problems and unhappiness eventually threatens to tip over into an exasperating melodrama. But I think Farhadi juggles all these motivations and events so well that we never feel that he has gone too far.

There has been some controversy over the fact that the film was shot entirely in France and therefore has little Iranian about it. Indeed, the Farsi-speaking emigrés who attended the VIFF screening to hear their native language spoken were perhaps disappointed that it was all in French. Yet in an ensemble cast, Ahmad remains the central character, helping to reconcile the others and comfort the three children (as in a rare cheerful moment when he helps the younger ones get a toy out of a tree).

If not quite as satisfying a film overall as A Separation, The Past confirms Farhadi as an Iranian director who can make appealing films for an international audience.

Trapped (Parviz Shahbazi, 2012)

Trapped is probably closer than most Iranian films shown at festivals to the sort of thing seen by popular audiences in its home country. The program notes describe it as a “moral thriller.” It revolves around Nazanin, a studious first-year medical student (see image at bottom) forced through lack of dormitory space to share a flat with party-loving Sahar, who is trying to leave Iran. Sahar has borrowed money to pay for her exit visa and, unable to pay it back, is imprisoned. Nazanin struggles selflessly to help her out, including foolishly signing a promissory note taking on Sahar’s debt and even sharing the threat of imprisonment.

The plot reminded me of the “child quest” tales that were prominent in the golden age of the Iranian cinema of the 1980s and 1990s, such as The Mirror and Where Is My Friend’s Home. (Shahbazi was the assistant director of Panahi’s The White Balloon, as well as conceiving its basic premise.) Here the heroine is distinctly older than the protagonists of those films, but she retains a naivete that makes her seem more childlike than the other characters, who manipulate and ultimately threaten her.

While Trapped doesn’t have the simplicity and charm of those earlier films, it offers an absorbing story. It paints a grim picture of Tehran and gives some insight into the realities of life there. Like many Iranian films, it raises the prospect of emigration, though in this case Nazanin’s strong desire to stay in the country and become a doctor is held up as the better choice.

A Place in Heaven (Yossi Madmony, 2013)

Two years ago I also reported on Madmony’s Restoration. A Place in Heaven is a considerably more ambitious film. It traces the life of a military hero, known only by his wildly inappropriate nickname Bambi, across much of Israeli history. The title derives from a flashback scene early on, when a cook at a military camp praises Bambi’s brave deeds and remarks that he has already earned a place in heaven. A secular Jew, Bambi scoffs at the notion and signs an impromptu contract trading that place to the cook in exchange for a daily spicy omelet.

Although Bambi dotes on his son Nimrod, the boy grows up to become a strictly religious Jew who disapproves of much that his father does. Still, when Bambi is on his deathbed, Nimrod goes in search of the cook to get back the place in heaven. As with Restoration, the plot is largely based around the father-son relationship, though there is also a touching and tragically short relationship between Bambi and his beautiful wife.

Unlike the largely urban Restoration, this film shows off the bleakly beautiful landscapes of Israel’s desert.

There were many other striking and moving films on display at VIFF this year. David and I really can’t do justice to all of them, but in a final post he will consider Koreeda’s Like Father, Like Son, Jia’s A Touch of Sin, Johnnie To’s The Blind Detective, the Godard segment of 3x3D, and Oliveira’s Gebo and the Thief. Like the items I’ve invoked here, each deserves an entry to itself, but time limits and further travels force us to be quick. Still, we hope that you can tell from our entries, VIFF 2013 yielded an extraordinarily high level of quality. As usual!

P.S. 17 October 2013: Thanks to Hamidreza Nassiri for correcting the original entry: Panahi is not, as we had said, under house arrest.

Trapped (2013).

“I don’t hate anybody, not even my interrogators”

Jafar Panahi, May 2010.

DB here:

From Tehran comes the shocking news that Jafar Panahi, one of the finest of Iranian filmmakers, has been sentenced to six years in prison. The sentence also bans him from filmmaking for twenty years, forbids him to leave the country, and forbids him from giving interviews to the press, foreign or domestic. Panahi’s collaborator Muhammad Rasoulof was also sentenced to six years in jail.

This is the next step in a series of confrontations between Panahi and the government. He was earlier arrested for attending the funeral of Neda Agha-Soltan, the young woman shot in the 2009 protests. His passport was later seized. Before his most recent arrest he was forbidden to leave the country to attend the Berlin and Cannes festivals. Between March and May of this year he was in prison, during which he undertook a hunger strike. In May he was released on bail.

Since the mid-1990s Panahi has directed several extraordinary films, all explicitly or tacitly critical of aspects of Iranian society. Like his mentor Abbas Kiarostami, he attracted attention with films centering on children, notably The White Balloon (1995) and The Mirror (1997). The latter is a fine example of how Iranian directors have merged social realism, unexpected character psychology, and experimental storytelling strategies. The first half shows a stubborn little girl trying to get home from school. On a bus, she gets tired of pretending to be in a film and goes off on her own, with her microphone still attached. The crew tries to track her down, and much of the rest of the action takes place on the soundtrack, as we hear her encounters with street life and the crew’s commentary on what they manage to shoot. Sometimes the sound drops out entirely.

The Circle (2000) shifts to the adult world, illuminating critical moments in the lives of several women as they traverse the streets. Crimson Gold (2003), from a script by Kiarostami, shifts from presenting a crime-thriller situation to providing an unusual view of Tehran’s prosperous upper class. Offside (2006) won attention for its exuberant portraitsof women who disguise themselves as men to watch a soccer match. Panahi remarked drily to the court: “The space given to Jafar Panahi’s festival awards in Tehran’s Museum of Cinema is much larger than his cell in prison.”

The charges and the replies

The Mirror.

The oppression of filmmakers isn’t new, of course. Authoritarian political regimes across film history have banned films and punished their creators. In recent times, the Turkish actor-director Yilmaz Güney was imprisoned several times; while incarcerated, he wrote scripts to be filmed by others. After Devils on the Doorstep (2000), Jiang Wen was banned by Chinese authorities from film activities for some years, as was actress Tang Wei for appearing in Lust, Caution (2007).

But Güney was convicted of civil crimes, although of a political nature; his films were not, as I understand it, explicitly part of the charges. And although Jiang and Tang were punished for their film work, that punishment didn’t include jail time.

Panahi is in an unusually vulnerable situation. He is set to be imprisoned for preparing a film.

The official charges are “assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security” and “propaganda against the Islamic Republic.” The authorities charge that he and his colleague Rasoulof were “preparing an anti-government film bearing on the post-electoral events” of June 2009, when thousands of Iranians protested the disputed reelection of President Ahmadinejad. “You are putting me on trial for making a film that at the time of our arrest was only thirty percent shot.” Panahi was shooting his film in his home, and government authorities seized the footage.

Other accusations sought to bolster the case. Panahi’s household, according to the prosecution, held “obscene films.” In his defense statement last month, he replied that these were film classics that have inspired him. He was charged with participating in demonstrations, but he replied that he was there to observe, and this was within his rights. He notes as well that he shot no footage of the demonstrations, acknowledging that filming was forbidden. As you know, on-the-spot reportage leaked out through Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.

Panahi was accused of making his film without permission, but he responded that there is no legal requirement that a filmmaker obtain permission. He was accused of organizing protests at the opening of the Montreal Film Festival, but there he served simply as the head of the jury. He was charged with giving interviews to foreign media, but he pointed out that there are no laws forbidding someone from being interviewed. He was even accused of not giving scripts to his actors! He explained that he works with non-professional actors, and it’s common for Iranian filmmakers to simply explain what the actor must do and say.

The charges may be simply a pretext for silencing a prominent figure critical of current Iranian society. Panahi’s films do not circulate legally there, and he is widely believed to be in sympathy with liberal forces. The government has sought to eradicate the most visible of these factions, the Green Party. Even Islamic clerics have been swept up in the crackdown. A parallel case to Panahi’s is the attack on Mohammad Taqi Khalaji, a dissident cleric. Last January he was arrested and his computer and papers were seized. He too was incarcerated in Evin prison before being released on bail. Yet he was not formally charged with anything. His personal papers, including his passport, were not returned to him.

You can get some grim satisfaction for knowing that movies still matter in some parts of the world. Films have the power to shock bureaucrats and threaten authoritarian regimes. Instead of being simply “assets” or “content” to be extruded across platforms and shoved through release windows, cinema is in some places taken seriously as political critique.

Panahi’s case, his lawyer asserts, will be appealed.

Out of bounds

Offside.

Lest we Americans savor our superior virtue, consider this: Four months before 9/11, Panahi was traveling between Hong Kong and Argentina and stopped over in New York. He had been told he did not need a transit visa, but he was detained by American authorities at JFK Airport for lacking one. Here is Stephen Teo’s account in Senses of Cinema:

On his way to the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema on 15 April, 2001, after having attended the Hong Kong International Film Festival, Panahi was arrested in JFK Airport, New York City, for not possessing a transit visa. Refusing to submit to a fingerprinting process (apparently required under U.S. law), the director was handcuffed and leg-chained after much protestations to US immigration officers over his bona fides, and finally led to a plane that took him back to Hong Kong. As far as is known, this incident was not reported in any major US newspaper, even though The Circle was being shown in the United States at the time (another irony: for that film, Panahi was awarded the “Freedom of Expression Award” by the US National Board of Review of Motion Pictures).

We are in the season in which critics are likely to use the word courage casually, as in “Natalie Portman gives a courageous performance in Black Swan.” The ongoing struggle of Panahi and thousands of his fellow Iranians remind us what real courage, in the world outside the movie theatre, looks like.

A petition addressed to Iran’s leaders in regard to Panahi and Rasoulof’’s case can be signed here. For one proposal for how world film culture could respond, go here.

A fairly detailed chronology of events around Panahi’s imprisonment can be found on Wikipedia. Panahi’s counter to the official charges, as well as the source of this entry’s title quotation, can be found here.

I have so far found no U.S. coverage of Panahi’s treatment in America in spring 2001. A report here from Australia suggests that he was detained but not arrested. Senses of Cinema has published Panahi’s letter to the Board of Review protesting his treatment on that occasion.

The case of Mohammad Taqi Khalaji is discussed here and here.

P.S. 22 December 2010: Yesterday Jonathan Rosenbaum posted his June 2001 review of The Circle. It’s an excellent piece, providing both in-depth analysis and broader context, and it does make reference to Panahi’s detention upon arriving in the U. S.

P.P.S. 22 December 2010: Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for a name correction.

P.P.P.S. 26 December 2010: Director Rafi Pitts has published an open letter to President Ahmadinejad about Panahi and Rasoulof’s sentence. Read it here at mubi.

Jafar Panahi and Jia Zhang-ke, Asian Film Awards 2007. Photo by DB.