Archive for April 2015

Richard Corliss: Fulltime Critic

Mary and Richard Corliss, Ebertfest 2008.

DB here:

Parker Tyler called James Agee America’s biggest movie fan, implying that he was a lesser critic for loving movies. But Agee, who was often cast into despair by the films he met week by week, was actually in love with Cinema. From each release he sought glimpses of what he imagined movies could be, and so seldom were.

Tyler’s phrase might better apply to Richard Corliss, but in a deeply complimentary sense. Like his friend and occasional jousting partner Roger Ebert, Richard didn’t judge a film by whether it measured up to some ideal yardstick of the medium. He welcomed the movies—at Time, some 2500, between 1980 and now—as they came. He let his wide tastes, good sense, vast memory and knowledge, and breakneck gift for language decide what they counted for.

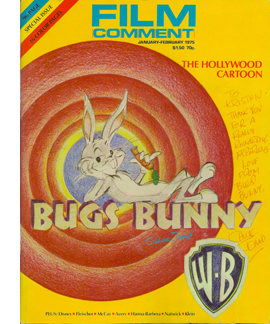

With Richard’s death we lose not only an effervescent critic. Under his stewardship of Film Comment (1970-1990) he helped found modern American film culture. Richard T. Jameson has eloquently recalled the Corliss era, when a magazine that had been committed to documentary and censorship debates became the paradigm of new ways of thinking about American and European film. Like Movie in England, it championed auteurism, and so it attracted great critics like Andrew Sarris, Robin Wood, and Raymond Durgnat. Yet Richard’s wide-ranging curiosity made Film Comment more pluralistic than its UK counterpart. It published reference-quality issues on animation, cinematographers, and set designers. In the days before the Net and specialized film books, cinephiles treasured these plump special numbers. The magazine ran historical and retrospective essays as well; refreshingly, not every piece was pegged to current releases. Richard gave us a new model of film magazines: richly designed, provocative (Durgnat especially), and sending the signal that everything cinematic could be studied.

With Richard’s death we lose not only an effervescent critic. Under his stewardship of Film Comment (1970-1990) he helped found modern American film culture. Richard T. Jameson has eloquently recalled the Corliss era, when a magazine that had been committed to documentary and censorship debates became the paradigm of new ways of thinking about American and European film. Like Movie in England, it championed auteurism, and so it attracted great critics like Andrew Sarris, Robin Wood, and Raymond Durgnat. Yet Richard’s wide-ranging curiosity made Film Comment more pluralistic than its UK counterpart. It published reference-quality issues on animation, cinematographers, and set designers. In the days before the Net and specialized film books, cinephiles treasured these plump special numbers. The magazine ran historical and retrospective essays as well; refreshingly, not every piece was pegged to current releases. Richard gave us a new model of film magazines: richly designed, provocative (Durgnat especially), and sending the signal that everything cinematic could be studied.

When he went over to Time in 1980, that square magazine suddenly looked younger. With Richard joining art critic Robert Hughes, it became a source of lively and penetrating arts journalism. Both turned Timespeak into something fresh. Hughes pulled it toward the eloquent bluntness of the Anglo essay tradition, while Richard transformed the forced puns and slant metaphors into something sprightly. Sarris may have been his mentor, but the rat-tat-tat pileup of clauses (semicolons optional), the self-correcting afterthoughts (as if a nuance had just occurred to the writer), and a concentration on actors all seem to me indebted to Kael. On Edward Scissorhands:

Depp, who wears the hyperalert, slightly wounded expression of someone who has just been slapped out of a deep sleep, brings a wondrous dignity and discipline to Edward. Wiest does a delightful turn on the plucky, loving mothers from old sitcoms. The whole movie, in fact, time-travels between today and the ’50s, when every suburban house could be a quiet riot of coordinated pastels. But the film exists out of time — out of the present cramped time, certainly — in the any-year of a child’s imagination. That child could be the little girl to whom the grandmotherly Ryder tells Edward’s story nearly a lifetime after it took place. Or it could be Burton, a wise child and a wily inventor, who has created one of the brightest, bittersweetest fables of this or any-year.

Richard gloried in the emotional and visceral energy of popular cinema. He defended both porn and zany comedy. On the Big Loud Action Movie he could channel Teenboy patois:

Toward the start of Fast Five — fifth and best in the series that began with The Fast and the Furious in 2001 — Brian (Paul Walker) is in a freight train and Dom (Vin Diesel) is steering a 1966 Corvette Grand Sport alongside it. At the last possible moment before the train goes through a bridge over a river, Brian jumps from the train and lands on the Corvette, which Dom then drives off a, like, million-foot cliff. As the car plummets down the ravine, our guys jump out and land safely in the water.

That “a, like, million-foot cliff” is alone worth the price of the issue. For such reasons, I think that Richard might be the most imitated critic of recent decades. Every reviewer at your town’s weekly hip throwaway wants to write like this.

They mostly can’t. In an essay on Fulltime Killer, Richard compared Johnnie To’s cinematic output to A. J. Liebling’s boast: “I can write better than anybody who can write faster, and I can write faster than anybody who can write better.” It pretty much applied to Richard himself. He wrote about film, books, TV, travel, sports. Of the Bulk Producers we always ask, “When does s/he sleep?” With Richard we have to ask: “When did he pause?”

The Richard I followed most closely was on display in long formats. His book Talking Pictures: Screenwriters in the American Cinema (1974) made a stir that’s hard to appreciate now. Good student of Sarris that he was, Richard was an auteurist. He once tried to persuade me that Russ Meyer was at least as good as Minnelli. Yet his book called us to arms in a different cause.

The most difficult and vital part of a director’s job is to build and sustain the mood indicated in a screenwriter’s script—a function that has been virtually ignored while citics concerned with “visual style” trot off in search of the themes a director is more liable to have filched from his writers. …

When it comes to the mood men, the metteurs-en-scène, auteur critics start tap-dancing away from the subject. George Cukor is a genuine auteur; Michael Curtiz is a happy hack; Mitchell Leisen is actually despised by some critics for “ruining” films like Midnight and Arise My Love. Yet what Leisen and the writers of Hands Across the Table did to make that film the most amiable of thirties screwball comedies is a prime example of sympathetic collaboration. As with so many delightful comedies, it is the writers who create the characters and establish a mood in the first half of the picture, and the director who develops both in the second half. The story line of Hands Across the table isn’t flimsy; it’s downright diaphanous. . . .

Openly imitating Sarris’ catalogue The American Cinema, Richard’s book created an artistic genealogy of screenwriters, picking out the Author-Auteurs, the Stylists, and so on and then ranking them.. But where Sarris is synoptic, Corliss is dissective. Working at full stretch, he gives pages of close attention to particular films. His analyses of The Power and the Glory, The Lady Eve, and The Marrying Kind (“wavering between third-person omniscient and first-person myopic”) carry great intellectual heft, while Sarrisian potshots fly by. Reputations get deflated (Jules Furthman) or elevated (Sidney Buchman).

The other Richard book I hold close is his BFI monograph on Lolita, a sustained critical tightrope act. Trembling between whimsy, serious examination, and a Nabokovian delight in shameless cleverness (puns again), Richard gives us Kubrick’s film as filtered through Pale Fire. There’s a bespoke opening poem (shades of Shade) which is then glossed line by line in as digressive a manner as poor Kinbote pursues in the novel. Nabokov as Hitchcock, echoes of Goulding’s Teen Rebel, Shelley Winters maneuvering her cigarette holder “as a Balinese dancer would her cymbals”: every paragraph scatters pieces of candy.

The other Richard book I hold close is his BFI monograph on Lolita, a sustained critical tightrope act. Trembling between whimsy, serious examination, and a Nabokovian delight in shameless cleverness (puns again), Richard gives us Kubrick’s film as filtered through Pale Fire. There’s a bespoke opening poem (shades of Shade) which is then glossed line by line in as digressive a manner as poor Kinbote pursues in the novel. Nabokov as Hitchcock, echoes of Goulding’s Teen Rebel, Shelley Winters maneuvering her cigarette holder “as a Balinese dancer would her cymbals”: every paragraph scatters pieces of candy.

Finally, something I return to often: Richard’s 1990 essay attacking (no politer word will do) TV movie reviewers. “All Thumbs: Or, Is There a Future for Film Criticism?” castigates the tribe’s superficiality, their canned brevity, their reliance on clips, and above all their encouraging people to believe in quick judgments. Stars, numbers, grades, and thumbs are too easy. Richard bites Time’s corporate hand, complaining about snack-sized opinions in People and Entertainment Weekly. Against this trend he speaks for longer-form writing, pointing out that Sarris, Kael, and others had their impact because they could surpass the word limits mandated for most reviewers. It takes time to develop ideas that are subtle. Obvious, maybe, but tell that to the young blogger who insisted to me that a review ought to take no more than 100 words.

Roger Ebert was a target of Richard’s piece, and he replied in a courteous counterblast. Yet the men were fast friends. Richard did friendship superbly, with an effusive generosity. Just out of college, I submitted a couple of articles to the new Film Comment, and to my astonishment Richard accepted them. As I turned more academic, I stopped offering pieces to the magazine, but Richard–who could easily have become a film professor himself–didn’t hold it against me. When I came to New York a few years later for a job interview that proved disastrous, Richard and Mary were the only friendly faces I encountered, and lunch at their apartment, larded with gossip, was the high point of that visit.

In later years I encountered Mary, mostly during our visits to MoMA, more than Richard. But every now and then I’d get another burst of gratuitous kindness. He reviewed my Planet Hong Kong in a funny online piece about how Hong Kong film takes the stuffiness out of anybody.

Even a relatively staid critic such as structuralist guru David Bordwell seems to be typing in his shorts, with a beer on his desk.

The last time I saw Richard was with Mary at Ebertfest in 2008. We had a diner breakfast, and Richard did a dead-on imitation of John McCain. I still see that smile—part devilish wise-guy, part nerdy enthusiasm, all glowing good humor. He was wearing goofy trainers bearing the logos of the Majors. They looked damn fine. We had a good day.

In an interview with David Thomson Richard recalls his life and the early Film Comment era. See also Matt Zoller Seitz’s sensitive appreciation, especially on Corliss’s mastery of the “long reported piece”–another point of contact with Agee.

The compleat screenwriter: David Koepp gives notes

DB here:

Regular visitors will know of my interest in David Koepp, screenwriter (Jurassic Park, War of the Worlds) and director (Ghost Town, Premium Rush). In 2013 I wrote an entry based on a long interview he kindly gave me.

Back in March of this year, David visited UW—Madison. It’s not strictly his alma mater; he left us to finish up at UCLA. Still, he retains ties to Wisconsin and recalls that while he was here he was inspired by our vast film society scene and some courses in the film and theatre departments. Across 2 ½ days he shared his experiences in a variety of settings, including Q & A’s after screenings of War of the Worlds, The Paper, and Ghost Town.

David is a craftsman who thinks about what he does. I’d call him an intellectual screenwriter if I didn’t think that made him sound more cerebral and austere than he actually is. He’s a vivacious, articulate presence: a born teacher, endowed with wit and good humor. During his visit he threw out plenty of ideas. Some are valuable for aspiring screenwriters, and others are intriguing guides for those of us who study movies.

Career paths

David Koepp and Maria Belodubrovskaya, 12 March 2015.

Starting out: If you want to write screenplays, a post at an agency isn’t ideal. It will, though, help you if you want to become a producer. Likewise, writing coverage can sensitize you to story, but it’s usually not the best route to becoming a screenwriter. It is a good path to becoming a creative executive.

Try to find a job that lets you write every day. A physically exhausting job makes you want to come home and zone out at night, when you should be writing.

Working from models: David learned a great deal from Kasdan’s Body Heat script. He recommends reading the first page of Hemingway’s novel To Have and to Have Not for a strong example of how character and story can co-exist and both start with strength and urgency.

David also urges writers to study plays, especially modern works by Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. [In the discussion, I failed to sell Chekhov as an alternative.]

Prepare for ups and downs, no matter how far you advance. Failure can encourage you to quit, but failure is endemic to the job and must be confronted the way an athlete learns to deal with injury. You must be resilient. “It’s dealing with failure that defines you as a person.”

Creative failures are, oddly, easier to handle if you’re directing because then the decision was yours. You understand how and why the mistakes were made. It’s harder to live with when you feel your script was in perfectly good shape and a director screwed it up or failed to express it clearly.

Maintaining a career

Death Becomes Her (1992).

“The first responsibility of an artist is to pay your rent.”

“Your ideas are your currency.” Talking about your script too much is a mistake. Keep your ideas to yourself as long as you can; otherwise you lose the need to write the script.

The time to talk is at the pitch meeting. It’s a bit disagreeable, but it forces you to have a clear-cut plot. “Until you tell it, you probably don’t have meaningful command of it.” Practice once or twice with a friend before the pitch, but not so many times that it becomes rote.

“Everything after the word no is white noise.”

Your first collaborator is the producer. Take seriously the problems he or she points out, but don’t automatically accept the solutions offered. Other voices are there to raise questions and point out problems, but not to solve them. Don’t let them take that job away from you; you’ll lose your voice.

The trick is to get your vision into the screenplay so that the director and the producer see it as you do. A good script is “all about clarity.” You can’t include camera directions, but every page should have a strong, simple image, briefly expressed. For example, in Death Becomes Her, Meryl Streep is teetering at the top of the stairs, before her husband pushes her down them. The script says: “She hovers there, like Wile E. Coyote at the top of a cliff.” It wasn’t a camera direction, but it called up a certain style in the mind of the reader, and, eventually, the director.

Read your dialogue out loud, playing all the parts.

Be prepared to have to write some things by committee, but, again, listen to the problems pointed out and think about the suggestions. But never let them fix your problems or take command of your story for you. It will lose its distinctiveness. The adage is: “No one of us is as dumb as all of us.”

The creative process

“Appeasing the audience gods”: Who will want to see your story?

The writer’s trance: “You get lost in it if it’s going well.” Play music, especially soundtracks to movies with a similar feel.

David’s steps:

*Thinking: “collecting string,” coming up with ideas on your own.

*Research: reading, interviewing, going on site. For The Paper, David and his brother visited a newsroom and got stories from journalists.

*Outlining: 3 x 5 note cards consisting of the obligatory scenes (“small, unintimidating chunks of story”). The cards can be arranged into five or so columns, corresponding to beginning, middle, and end. The card array gets turned into a prose outline (10-25 pages), with dialogue. “This is the heavy lifting.” At this point, the cards have served their purpose and you probably don’t return to them.

*First draft: Basically, something you can revise from. Those revisions should be successively shorter, so the story is never obscured by excessive description, no matter how well-written. “Scripts are not about pretty writing.” Be ready to cut. “You need less than you think you do.”

The 3-act structure is like musical scales, “something you can embrace or something you can rebel against.” But without some sort of structural approach, “it is all forest, no trees.”

Hollywood rewards success, but it also expects repetition of success. Your job is to try to do something different as frequently as possible. “I tried to write in every genre that interests me.”

Over twenty-seven years, David wrote about thirty scripts. Of them, roughly two dozen got made. Of that number, nine were originals. The most successful original was Panic Room, which was born from two ideas: the popularity of “safe rooms” in urban mansions, and the claustrophobia he once experienced when trapped in a small domestic elevator in a Manhattan townhouse.

Adapting a novel: In adapting, he first writes up an outline of the book itself, as written, to internalize its its structure, before creating the movie’s structure. Don’t worry about imitating the prose texture, especially passages presenting mental states. Film is about images and sounds, visible behavior and speech. But you can be faithful to the spirit of the novel. The War of the Worlds, though an update, respects Wells’ ideas and characterization.

Don’t pass up chances to use your craft; any job can be fun. Some assignments are painting, some are carpentry.

Rewrites may be imposed by studio staff or stars (who often push for a better or bigger role). You have to fight your way through them, taking what can help and talking your way out of ideas that can hurt. “Everything is a negotiation.”

In the shooting phase, the writer is often in a black hole, with nothing much to do. You needn’t be on the set, but do have to stay available if something needs to be done.

Studying film

The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997).

What would David study if he were an academic? “I’d love to take a course that traces influences, such as the connection between Shaw Brothers and Tarantino. In other words, get away from traditional categories of genre and national cinemas and focus on conections of thought and style between apparently diverse filmmakers.”

Would he focus on directors rather than screenwriters? Yes, because the director is “the overriding creative force.” Today a screenwriter needs a director’s support to get a film done. Moreover, directors “have a degree of control you can’t imagine.” They shape performances, tone, imagery, and sound, and they often govern script rewrites. David was struck seeing You Can’t Take It with You on stage and then noticing how Capra’s film version made the play’s amiable patriarch into a capitalist villain–a characteristic Capra touch.

Accordingly, major directors like Fincher become obstinate about details. “You have to be belligerent. There’s no other way.” David was present when Spielberg couldn’t get the overhead shot he wanted in The Lost World: Jurassic Park. The plan was to frame raptors rushing through tall grass from above, so that all we see are trails converging on the fleeing people. But on the first visit to the location, the grass wasn’t tall enough. “If I don’t have the grass,” said Spielberg, “I don’t have a shot.” Tall grass had to be replanted and the shot taken later. [DB: I think that shot is borrowed, somewhat clumsily, in the Wachowskis’ Jupiter Ascending.]

Producers also can control the process. Accordingly, David would also study ones with strong identities like William Castle and Sam Spiegel.

David’s affinity is for classic Hollywood. As a kid watching on TV, he liked horror films and Sherlock Holmes movies. He likes modern films in the classic tradition. When he was 14 he saw Star Wars soon after Jaws, and these had strong impact on him. The only comparable phenomenon today, he thinks, is the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

On noir, especially Snake Eyes

Snake Eyes (1998).

What made him write so many noirish thrillers? Probably his childhood; your tastes are formed between 14 and 24. He experienced the darkness and paranoia of the 1970s, intensified by the fact of his parents divorcing. An important influence was Rosemary’s Baby as well, a film he still reveres.

Filmmakers love noir, but don’t describe your project as a noir. Studios hate the term. They believe it doesn’t sell. Panic Room isn’t a noir, the producers were told; it’s like “an Ashley Judd movie.” [Presumably before that became a problematic term too.—DB]

The morality of noir is tricky. You can have unsympathetic protagonists, but be careful handling the bag-of-money movie. You can’t reward greed. “You can’t get away with the money.” In The Killing, the money has to blow away. True Romance was less powerful, ending with the kids on the beach dancing and rich. This concern isn’t mainly about morality, just an ending that satisfies.

David wrote Carlito’s Way as a 30s Warners gangster film, with a characteristic downbeat ending. Hence the need to lead the audience to expect a dying fall: A flashback and the voice of a “nearly-beyond-the-grave narrator.” The whole movie takes place in an instant.

In Snake Eyes, David welcomed the noirish formal problem of telling the same story three times, as in Rashomon. The tripled presentation would have occupied Act 2. What about the optical POV switches? Typically, shots aren’t fully scripted, and they weren’t here: the POV angles were De Palma’s choice.

Originally the film had a classic noir flashback structure. The opening would show flood waters after the storm, with floating chips, playing cards, and a blackjack table. Then the main story would take us into the past. The climax, back in the present, was to have been a fight in the water with Sinese trying to drown Cage.

As for giving away a key element midway through: David thought it would work. (Hitchcock did it in Vertigo.) But audiences didn’t like it. They seem to feel uncomfortable knowing something big that the main character doesn’t. But what about a movie like Ransom, which also reveals the villain? Not such a problem, says David, because if you show a character lying, you should do so quickly—not hold off for many scenes and reveal it a fair distance from the climax.

“This is the fun part of storytelling: What do we tell ‘em, and when?” [DB: In Film Art, we put it this way: “Who knows what when?”]

Envoi

What about the writers’ tasks in the late phases of preproduction? As I was finishing this entry, David sent a dispatch from Inferno, Ron Howard’s latest Dan Brown adaptation. After moving from Budapest to Florence to Venice, the production starts shooting tomorrow. David writes:

David Koepp visiting the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, with Vance Kepley, Director; Amy Sloper, Head Film Archivist; and Mary Huelsbeck, Assistant Director.

Pesky brats, adventurous ducks, and jiving swamp critters

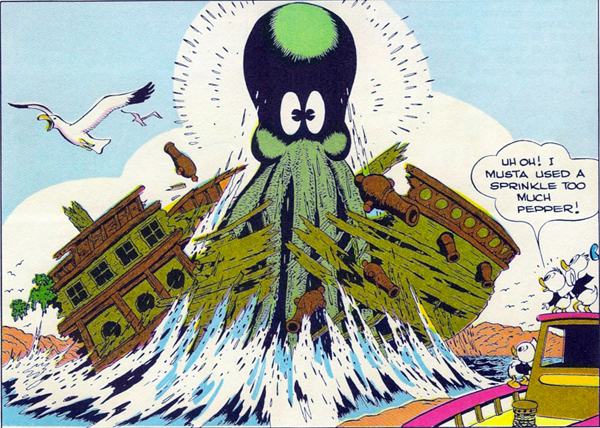

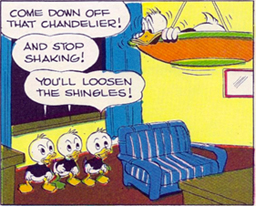

Carl Barks, Ghost of the Grotto (1947).

DB here:

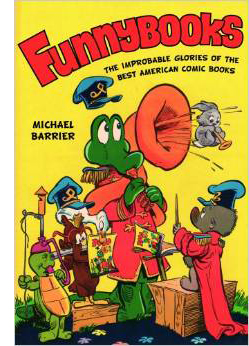

We never need an excuse to write about comic strips or comic books. We’re fans and, just as important, we think of them as having important connections to film. We’re particularly fond of classic funny-animal comics, from Krazy Kat (the greatest) onward. So I got a double dose of pleasure reading Mike Barrier’s Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books. It taught me a lot about the history of some favorites, and it set me thinking about some overlaps and divergences between film and graphic art.

No Girls Allowed

Like Mike’s Disney book The Animated Man, Funnybooks is at one level a scrupulously researched business history. It explains how publisher Western Printing and Lithography (of Racine, WI) became the center of a thriving industry. Before the mid-1930s the company’s juvenile line came out chiefly under the Whitman imprint. Its illustrated storybooks licensed characters from Disney and comic strips like Dick Tracy and Little Orphan Annie. But Hal Horne and Oskar Lebeck pushed toward creating comic books proper, those inviting items that could compete with the superhero titles that were emerging. Their instincts were sound: Western’s comics, distributed by the Dell company, sold hundreds of thousands of copies.

After several tries at compiling daily comic strips into a single volume, Lebeck turned to original content. In the early 1940s he hired Walt Kelly, Carl Barks, and John Stanley. All had worked in film animation (Kelly and Barks for Disney, Stanley for Max Fleischer), but they adjusted to the demands of more static cartoon art. Into the rise and fall of Western and Dell, Barrier weaves the personal stories of the three creators and their less famous peers. Funnybooks is at once industrial history and a collective biography.

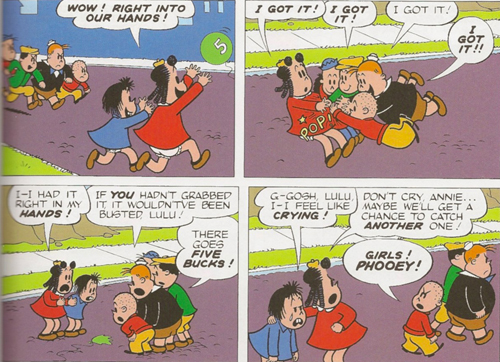

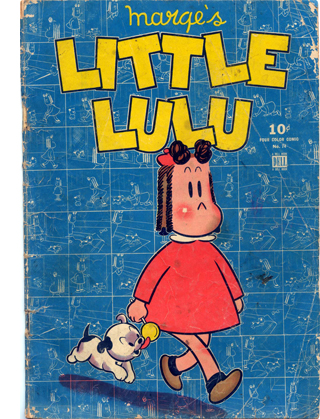

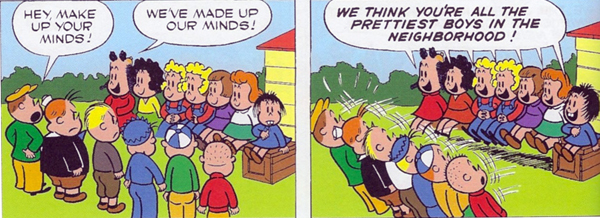

John Stanley, the least known of the trio, was brought on to do stories of Little Lulu, the stolid, crisply-curled girl created by Marjorie Buell. Stanley wrote and drew the entirety of the first book in 1945. The cover presents a heroine as blank as Hello Kitty and a background grid as febrile as a Chris Ware design. Afterward, Stanley chiefly served as writer on the Lulu stories, providing other artists with detailed scenarios and sketches. The panels might be somewhat stiff, but the plots were admirable. Often turning on mean childhood pranks, they were steeped in spite and petty revenge.

I remember enjoying Lulu’s stories, especially their verbal comedy. When Tubby (I think it was) hits Lulu with a pie, he says, “I’ve thrown a custard to her face.” Lulu replies: “I liked breathing out and breathing in.” This was probably a post-Stanley passage, but the fact that I’ve remembered it for sixty years indicates the ways grown-up jokes can stick in the unformed brain. (I knew Boris Badenov before I knew Boris Godunov.)

Mike is very good on the bitter humor that Stanley puts on display as Lulu and her girl pals skirmish with Tubby and his gang of sexist bullies.

His characters were never vulnerable to the suggestion so often made about the children in Charles Schulz’s comic strip Peanuts—that they were adults masquerading as children. They were instead children whose quarrels and schemes echoed adult life.

Lulu evolved, Mike shows, into a trickster who constantly showed up the boys, even as she herself was sometimes slapped down. In one story a rich boy, seeing Lulu longing for pastries in a shop window, doesn’t consider buying her one. Instead, he buys the shop and drops the shade on the window. Walking away on his golden stilts, “he felt very happy because now the poor little girl wouldn’t have to look at things she couldn’t buy.” Another compassionate conservative.

Stanley drew many other characters, including Bushmiller’s Nancy and the ingratiating Melvin Monster. His career fizzled out when comic-book publishing hit hard times in the 1950s. He wound up working in a factory that made aluminum rulers.

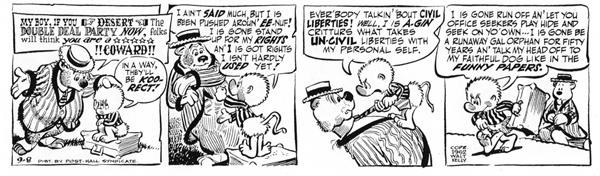

Rowrbazzle

Walt Kelly fared better. In the beginning he he worked on many series but he gained fame with his own creation, the enduring swampland of Pogo Possum and his friends. “Ensemble comedy,” Mike calls the remarkable menagerie Kelly assembled.

At first speaking in mangled Southern accents, Pogo, Albert the Alligator, Porkypine, Howland Owl, Churchy la Femme (another joke passing over kids’ heads), and a host of other creatures developed a patois as bizarre as the rodomontade you hear in Coconino County. Characters sang nonsense songs, recited garbled poetry, and engaged in pun-filled miscommunication. The wordplay was enhanced by lettering adjusted to different characters, notably the Gothic script associated with Deacon Mushrat and the circus-ballyhoo font employed by con artist P. T. Bridgeport.

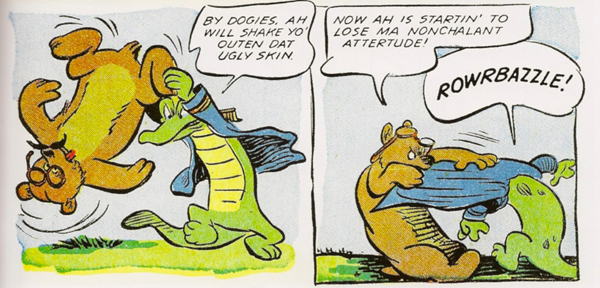

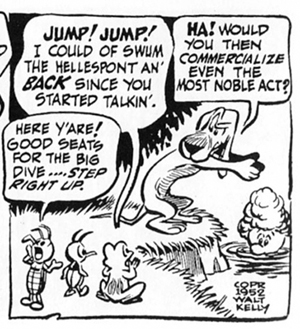

Slapstick went along with the verbal pyrotechnics. Kelly’s fluid line created complex equivalents of movie pratfalls, each one enlivened by fussy details (check the bear’s glasses below) and punctuated by unique sound effects. Barrier reports that in one Kelly comic, a cannon explodes with the sound “FRED.”

In all, eccentricity was the watchword, usually accompanied by food, or characters trying to get it. Albert had a disconcerting habit of accidentally eating his friends. Any of the crew might launch into retelling a classic children’s story featuring the entire cast. These were fairy tales not so much fractured as splintered. In all, it’s astonishing how many pictorial and verbal gags Kelly could cram into four daily panels.

Kelly, a superb draftsman, learned the secret of round forms in his Disney days, and Mike traces how this tendency toward cuteness helped make Pogo a success. But Kelly also had a nutty sense of humor that set him apart from other Western/Dell artists. Mike surveys Kelly’s range, from liberal political cartoons to Our Gang comics, and he treats with care how Kelly’s work included both racial caricatures and more affirmative images of African Americans.

Mike shows how Kelly’s talents outgrew the Dell family. As Pogo and his pals became more popular with intellectuals, the comic-book format proved a rickety vehicle for the artist’s ambitions. Kelly shifted his energies toward daily and Sunday strips that attracted nation-wide attention, not least for satirizing Joseph McCarthy and the Jack Acid (aka John Birch) Society. Pogo’s swamps, I thought at the time, became the liberal counterweight to Al Capp’s reactionary Dogpatch. Like Doonesbury and Calvin & Hobbes later, the dailies became incorporated into best-selling books published by Simon & Schuster. Those collections, to be found on every college kid’s bookshelf in the 1960s and 1970s, made Pogo as much a part of the official counterculture as Frodo Baggins. “We have met the enemy and he is us” became the slogan of a generation.

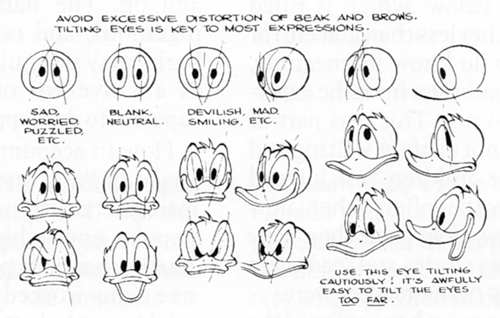

A peculiar affinity with those damn Ducks

If Funnybooks has a protagonist, it is Carl Barks. No wonder. Unlike Stanley, he both wrote and drew his books. Unlike Kelly, he was anonymous. A modest worker prized by all who knew him, he simply spent year after year turning out the beautifully crafted adventures of Donald Duck, Uncle Scrooge, and their associates. He was, it seems, born to make funny-animal comic books.

Mike Barrier is a long-time Barksian. His 1981 Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book is at once a biography, an appreciation, and a catalogue raisonné of this master of precision artwork. The new book fits some of Mike’s earlier arguments into the wider tale of Western and Dell, but he has also deepened his ideas about the nature of Barks’ achievement. He is able to expand his recognition of Barks’ gift for characterization, mood, and emotional expression.

Mike Barrier is a long-time Barksian. His 1981 Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book is at once a biography, an appreciation, and a catalogue raisonné of this master of precision artwork. The new book fits some of Mike’s earlier arguments into the wider tale of Western and Dell, but he has also deepened his ideas about the nature of Barks’ achievement. He is able to expand his recognition of Barks’ gift for characterization, mood, and emotional expression.

Instead of merely recycling an iconic character from the Disney animated shorts, Barks gave Donald his own town, Duckburg, populated by a new cast of characters—Gyro Gearloose, Gladstone Gander, the Beagle Boys, and others. Barks, it seems, gained this creative freedom because everyone at Western admired him. Mike quotes one old timer who calls Barks “the genius of the group. . . . He had a particular affinity with those damn Ducks.” Barks once thought he could support himself raising chickens. Fortunately for us, he turned his poultry fascination to comic books displaying elegant storytelling.

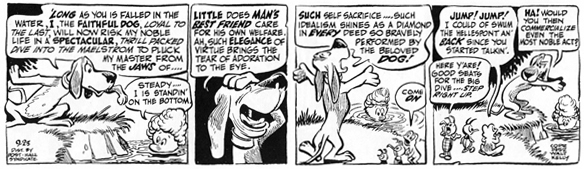

Here’s where Mike set me thinking about some relations between film and comics. He points out that a panel often needs to convey the passage of time—not through movement, as in film, but through devices for suggesting interplay among characters and their environment. The staging of the action, the composition, and the placement of dialogue balloons all create a rhythm of reading. Whereas Japanese manga can split an instant into many single, striking images (and thus create very long books), American comics developed ways to suggest the ripening of the story, moment by moment, within each panel.

My last Pogo panel featuring the self-aggrandizing hound Beauregard is a good example.

Without the balloons, the image would be a snapshot, but the balloons produce a temporal flow. The most prominent balloon, filling about a quarter of the frame, reports the frog urging Beauregard to jump. The next balloon that we notice, snuggled against the first, shows the bug trying to exploit the rescue (“Step right up”). Farthest right, Beauregard replies to the bug, talking diagonally past the frog. The speeches are the usual Kelly demotic, incorporating low slang, literary references, and pompous rhetoric, and the order in which we read them and attach them to action accentuates the differences in diction.

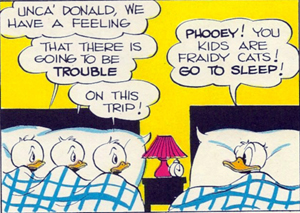

Barks could create this sense of rhythmic duration with his ready-made chorus of Huey, Dewey, and Louie. In this panel from “Frozen Gold” (1944), the cascade of balloons assumes a left-to-right reading and creates a pulse capped by Donald’s brusque reply.

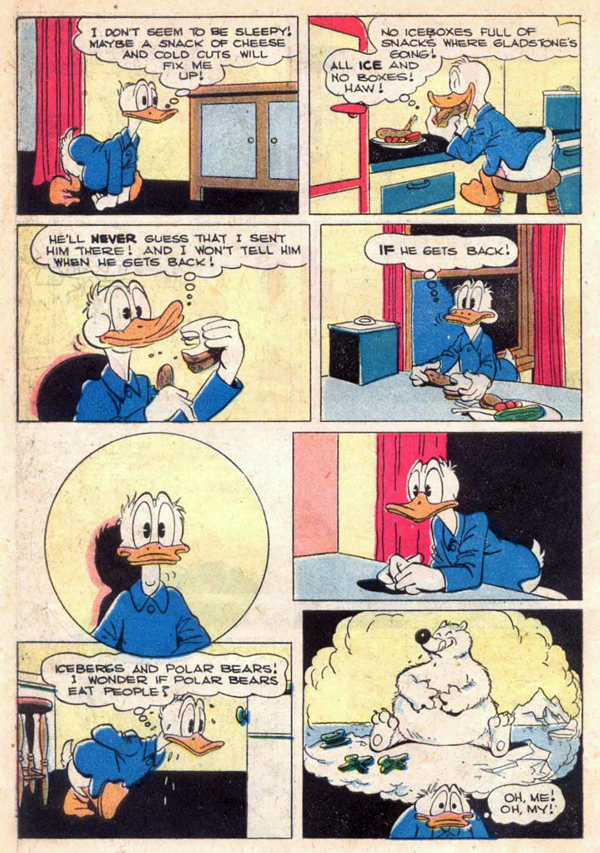

Most panels don’t create such a dense sense of time unfolding. That is more commonly achieved through several panels depicting a stretch of action. Or sometimes inaction. In a wonderful passage, Mike discusses how Barks uses a pause to suggest Donald’s growing guilt feelings after sending the odious Gladstone to the North Pole. At first he gloats, but then in a series of panels he starts to question what he’s done.

Barrier takes this page as a turning point in Barks’s evolution as an artist. Eight panels, some without action, convey a deepening psychological state, capped with an image of Donald crushed by his imagination of what could happen to Gladstone. The sense of food stuck in Donald’s craw is nicely hinted at by two motion lines near his neck.

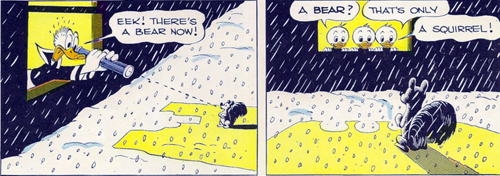

Instead of stretching action by a pause, the artist can accelerate it through ellipsis. Here’s a lovely Barks passage from “Christmas on Bear Mountain” (1947) that’s somewhat filmlike, and yet not. Huey, Dewey, and Louie are checking out a snowstorm and Donald approaches with his telescope. The suggestion is that he approaches their window from off right, with only a few steps until he gets there.

Now comes the first ellipsis: The boys have left the window, and Donald is already spotting what he thinks is a bear. This is very concise storytelling. A sharp change of angle shows another ellipsis: the boys are back at the window identifying the squirrel.

In the “cut” between panels 3 and 4, Donald has disappeared. Where’d he go? The next panel shows us.

The jumps in time are covered by the smoothly varied compositions: 1 and 2, sitting side by side, flow neatly, while 3 and 4, overlapping pictorially, actually cover a time gap. The gap is filled by panel 5, a nice variant on what we saw in 1 and 2. You’d seldom find cuts like these in a film, though I’d welcome somebody trying.

I don’t want to give the impression that Funnybooks is a theoretical study. Mike Barrier, who has thought seriously about the aesthetics and history of comics for fifty years, has given us another precious historical account of this extraordinary popular art and three of its masters. It’s up to us to recognize how his discoveries can shed light on pictorial storytelling generally.

P.S. 28 April 2015: Funnybooks has been nominated for an Eisner Award. Congratulations to Mike! Another fine nominee is Thierry Smolderen’s The Origins of Comics: From William Hogarth to Winsor McCay (University Press of Mississippi), translated by Bart Beaty & Nick Nguyen.

My illustrations are drawn from The Best of Walt Disney Comics 1944 and The Best of Walt Disney Comics 1947 (Western Publishing, n.d.); Walt Kelly, Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics, vol. 2 (Hermes, 2014); Walt Kelly, Pogo: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, vol. 2: Bona Fide Balderdash (Fantagraphics, 2012); and Little Lulu Color Special (Dark Horse, 2006). The model sheet of Donald heads comes from Mike Barrier, Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book (M. Lilien, 1981), 43.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell of Twentieth Century Books for helping me find some rare items. And be sure to check Mike Barrier’s encyclopedic website. His 23 April entry rounds up several reviews of Funnybooks.

If anyone reading this doesn’t know Scott McCloud’s superb surveys of the art and craft of comics, I should mention Understanding Comics (Morrow, 1993) and Making Comics (Morrow, 2004). Both books contain many observations on how comics manipulate time.

Looking back at my blog entry on Tintin, I think that the sense of time unfolding within the frame is what Hergé was getting at when he picked a certain image of Captain Haddock as the essence of his method. In the same entry, I suggest that Hergé was creating continuity and ellipses in ways similar to Barks’s Bear Mountain story. Still, Hergé offers more tightly constrained choices of angle and less drastically changing compositions.

They had time for everything then

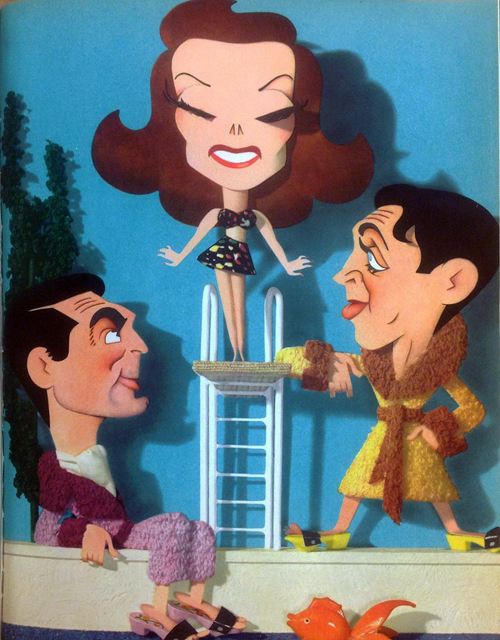

Advertisement for Woman of the Year. From Hollywood Reporter (23 April 1942), 5.

During the 1940s, MGM promoted some of its top pictures with unique illustrations. The artist would make cutout caricatures of the stars, dress them in fabrics, and then prepare little shallow-relief scenes, with props made of wood, carpets, and other stuff. Above, the microphones seem made of metal and plastic, and Tracy’s coat has real buttons attached. Below, the men’s slippers are three-dimensional, as is the toy goldfish and, I suppose, the diving board.

The little tableau would then be photographed, in luscious color. Some were printed with elaborately embossed borders.

I say “the artist” because he or she goes unidentified on these advertisements. The only signature is an enigmatic “K”; in the image above, it’s on the tiny baseball at the bottom. If anyone knows who K is, or can supply further background, please correspond.

Interestingly, these charming images continued to be published from time to time through the early years of the war. I’m afraid my reproductions don’t do them justice, but you get the idea.

Damn, but film research is fun.

P.S. 24 April 2015: Ask and ye shall receive. Alert reader Mark Schoenecker writes:

I’m sure you’ve already received correspondence naming the identity of the mysterious MGM illustrator responsible for those distinctive 3D paper sculpture pieces from the 30s and 40s — but in case you haven’t, his name is Jacques Kapralik. I’m an illustrator myself and have always been vaguely aware of the existence of these cut-out posters. What I didn’t know was that one man was behind them. I’d assumed it was a style prevalent during that era. It wasn’t until I found myself drawing my own series of caricatures in a similar vein that I decided to track down the originals online to see if I was remembering them accurately.

Here is a link to the most interesting article I came across: https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/movie-poster-of-the-week-the-jacques-kapralik-archive

I should’ve known that the indispensable MUBI would have something on this. It’s a fine piece of work by Adrian Curry, showing that Kapralik did movie title sequences as well. Be sure to check the links in that entry and the comments. The University of Wyoming holds Kapralik’s collection, and an online finding aid gives access to many of his beauties.

Many thanks to Mark for clueing me to this. You should immediately check Mark’s own lively, dry, and sometimes scathing, caricatures here. Who else thinks of drawing Dorothy Kilgallen and Korla Pandit?

Advertisement for the The Philadelphia Story. From The Hollywood Reporter (31 December 1940), 7.