Archive for the 'Directors: Lau Kar-leung' Category

Lau Kar-leung: The dragon still dances

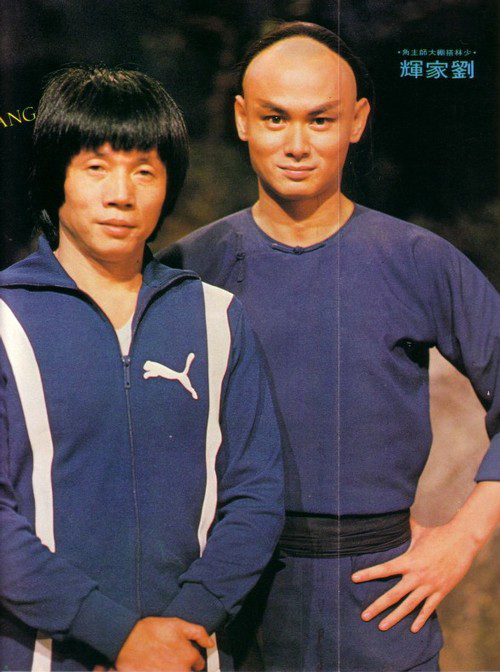

Lau Kar Leung (aka Liu Chia-liang, 1936-2013); Gordon Liu Chia-hui (aka Lau Kar-fei, 1955-).

DB here:

Back in 2020, I was asked to prepare a video lecture on the Hong Kong filmmaker Lau Kar-leung. Under the auspices of the Fresh Wave festival of young Hong Kong cinema, a retrospective and panel discussions were sponsored by Johnnie To Kei-fung and Shu Kei. The event took place in summer 2021. Tony Rayns also participated, offering a deeply informative talk that’s available here, but mine was not included. At a time when I hope people will continue to remember all that Hong Kong popular culture has given us, I’ve recast it as a blog entry.

For some years I’ve been arguing that the martial arts cinema of East Asia constitutes as distinctive a contribution to film artistry as did more widely recognized “schools and movements” of European cinema like Soviet Montage and Italian Neorealism. The action films from Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan have revealed new resources of cinematic technique, and the filmmakers have influenced other national cinemas. The power of this tradition is particularly evident in Hong Kong cinema’s wuxia pian (films of martial chivalry), kung-fu films, and urban action thrillers from the 1960s into the 2000s.

Chinese martial arts are well-suited to the movie screen. The performance discipline, seen both in the martial arts and in theatrical traditions borrowing from them, yields a patterned movement that lends itself to choreography. The staccato quality of motion yields a pronounced pause/burst/pause rhythm that can be displayed and enhanced by film technique, as we’ll see.

These aspects of martial arts were captured by filmmakers working for the Shaw Brothers studios between 1965 and 1986. They cultivated a local style that yielded films that looked unlike any others. Thanks to the immense resources of the Shaw Movietown studio, complete with big sets and collections of costumes, the new filmmaking style was given a unique force. With The Temple of the Red Lotus (1965) and Come Drink with Me (1966), what Shaws called its “action era” began, and thanks to international distribution Shaws’ swordplay films gained audiences around the world.

Shaws’ Big 3

Shaw Movietown main office, 1997. Photo by DB.

The new trend benefited from Chinese opera traditions and the martial arts novels of Jin Yong, pen name of Louis Cha Leung-yung. They also owed a debt to Japanese swordplay films, many of which Shaws distributed and urged their directors to study. There was as well the influence of Italian Westerns. Just as important was Shaws’ investment in color and widescreen processes. Updating technology not only allowed the films to compete on the world market; it offered rich opportunities for artistic expression. (See the essay “Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic adventures in Hong Kong.”)

Shaws directors quickly established conventions of the new swordplay film. Conflicts, of course, were expressed through combat, at least three major ones per film. One source of friction was the rivalry between martial arts schools run by masters; there might also be competition among traditions, regions (northern/southern), or nations (China vs. Japan). Typically there would be a hierarchy of villains, with our protagonists fighting them in turn. Plots would be more episodic than is typical in Western films. A looser structure favored including extensive set pieces of training or combat that were the appeal of the genre. And the plot would culminate in a long climactic fight, often to the death. These conventions, consolidated in the wuxia pian, carried over into the kung-fu films of the 1970s.

Two directors played central roles in shaping these conventions, and each had a distinctive approach to them. The vastly prolific Chang Cheh (Zhang Che) dominated the Shaws lot. He favored violent plots turning on revenge and intense male camaraderie, in which the martial arts served as a drama of loyalty or betrayal, friendship or deadly enmity. At the same period King Hu Chin-Chuan created one of the breakthrough “action era” works, Come Drink with Me, which immediately established a very different authorial vision. Hu was interested in historical and political intrigue, women warriors no less than male ones, and the martial arts as a spectacle of cinematic grace. Most of his major works, including A Touch of Zen (1971) were produced after he emigrated to Taiwan, although some were distributed by Shaw Brothers.

Neither Chang Cheh nor King Hu was trained in the martial arts, so they relied on choreographers to supply their action scenes. By contrast, Lau Kar-leung was a martial arts director who came to Shaws in the 1960s and choreographed many films for Chang and others. He took over directing duties in 1976 with The Spiritual Boxer and directed over twenty-five films for Shaws until 1985, when the company ceased producing theatrical features. He went on to direct several one-off projects until 2002.

Lau took the uniqueness of martial arts traditions more seriously than other directors, building entire films around one school or another, or among the contrast of rival traditions. He often opens the film with an abstract prologue showing off characteristic moves and tactics of the style that the film will treat. Unlike Chang, he is less concerned with male loyalty and violent revenge and is more inclined toward redemption and forgiveness. He shares Hu’s refined conception of film technique, but he is less overtly innovative. He refined stylistic conventions that were already in place at Shaws and many of which were basic to world cinema storytelling.

For example, Lau accepted the elevated production values demanded by the Shaw product. His films are filled with elaborate sets, both interiors and exteriors, and rich color values. He also recognized the power of editing, something that King Hu had brought to the fore. In the rest of this entry, I’ll concentrate on four of Lau’s distinctive innovations in the Shaws style.

Filling the wide frame

All widescreen filmmakers faced the problem of filling the spacious frame. (See CinemaScope: The Modern Miracle You See without Glasses” for discussion of American solutions.) The big Shaws sets enabled filmmakers to pack the frame with figures and settings. We therefore find plenty of dense long-shot compositions.

We also find flashy closer views. Chang Cheh was particularly fond of low-angle medium shots, which he considered “warmer” than straight-on or high angles (The Assassin, 1967; choreographed by Lau).

Hong Kong directors relied on “segment shooting” for action scenes. Instead of overall coverage, with repetitions for different camera angles (the US norm), they plotted the fighting moves for specific camera angles and shot them separately. By calibrating the performers’ actions to the camera setup, they created a unique blend of martial arts techniques with film techniques. Rather than simply record martial-arts movements, filmmakers “cinematized” them.

Lau seems to have taken particular pleasure in filling his frames in ingenious, fluid ways. He enjoyed the challenge of staging combat scenes in confined spaces, so that he couldn’t rely on expansive vistas. Partly, this tactic enabled him to show how different moves were required in close quarters. One of his favorite sequences was in Martial Club (1981). He explained:

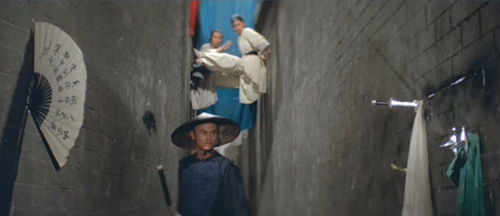

Gordon Liu is fighting Johnny Wong in an alley that narrows from 7-foot to 2-foot wide. The physical limits of the alley actually make the best showcase for the different boxing schools. How do you fight in a seven-foot-wide alley? You use big arm and leg movements. Going down to five-foot wide, you keep your elbows close to your body because you don’t want to expose yourself. Further down to three-or-four foot wide, you use Iron String Fist. Finally when you get down to two-foot wide, you engage the “sheep trapping pose.” The results were sensational.

At the same time, the narrowing alley offered rich opportunities to fill the frame with body parts and abstract slices of walls.

Something similar occurs in Legendary Weapons of China (1982), where two assassins must hide in an alley above a third. This time Lau uses some props to fill out the wall areas.

Lau delights in the possibilities of close fighting in any space. Sometimes the confinement isn’t a matter of setting; it’s dependent on letting the film frame itself constrain the action. Take a portion of a sequence from Dirty Ho (1979). The Prince (in disguise) calls on Mr. Fan, who tries to attack him, all the while pretending to play the host by offering wine.

Establishing shots lay out the zones of action to come, the chairs the men will occupy. Even a momentarily unbalanced framing is compensated for by movement in the empty area.

The first phase of the scene takes place in much closer framings, often tight two-shots. It’s here we see Lau’s virtuosity in finding constantly fresh ways to fill the frame, with compositions always picked for maximum clarity: that is, in showing Fan’s aggression and the Prince’s resourceful blocking, sometimes with comic symmetry.

The pause/burst/pause rhythm gets played out in low angles, with slight camera movements to adjust to the gestures.

The two major props, the fan and cups, get a real workout as they participate in the constant ballet of arms, faces, and fingers. All areas of the screen get activated: top, bottom, corners and sides.

Later in the scene, in a passage I haven’t included in the clip, the servant gets to take part, so now even more body parts are spread across the frame–and a cup even comes out at the viewer.

The scene ends with a comic commentary on the props: master and servant collapse at the table as a cup overturns.

This “close-up action scene” is as fully designed for the widescreen as any expansive long-shot sequence might be, but there’s a particular enjoyment to be had in seeing how a director can do so much with simple components.

Editing: Analytical cutting

Contrary to what many think, Chinese action pictures rely heavily on editing. At Shaws, King Hu pioneered extremely rapid cutting, reducing shots to half a second or less. Lau became a rapid cutter as well; his films from the 1970s and 1980s typically average three to five seconds per shot, with some films containing over 1000 shots.

It’s commonly said that Hong Kong martial arts films favored full shots and long takes, the better to respect the overall dynamic of the combat. Full shots, yes; but not necessarily long takes. While Western directors tended to believe that long shots had to be held quite a bit longer than closer ones, Hong Kong directors realized that long shots could be cut fast if they were carefully composed for quick uptake. Lau’s mastery of composition stands him in good stead when he starts putting shots together: every combat, even the fast-cut ones, are crystal-clear in their execution.

Directors across the world had settled on two major editing resources: analytical cutting and constructive cutting. The first type shows the overall spatial layout of a scene and then analyzes it into partial views. Our Dirty Ho sequence is an example. Constructive cutting deletes the establishing shot and relies on other cues to help the viewer build up the scene mentally. Hong Kong filmmakers made extensive use of both types, and as you’d expect Lau is a master of each.

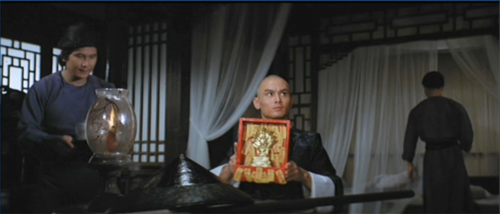

Most Hong Kong directors used analytical editing to favor the actors, to pick out their reactions to the ongoing action. Lau does this as well, as is seen in Dirty Ho. As you’d expect, Lau also uses cuts-in close views to emphasize combat tactics. In Challenge of the Masters (1976), after a villain (played by Lau) has felled his opponent, analytical cuts build to a revelation of a metal attachment to his shoe.

Executioners from Shaolin (1977) illustrates how Lau uses analytical editing during a large-scale fight scene. It’s far less constrained than the tabletop action of Dirty Ho, but he does find ways to narrow the action to particular zones. This is done through cuts to closer views–sometimes very close ones. And the editing is swift, with the average shot lasting only four seconds.

The scene’s opening establishes the hero Hung Hsi-kuan arriving at Pai Mei’s temple. There are two establishing shots, one a pan-and-zoom that presents the temple as Hung arrives, while the other (below) is a zoom back keeping the temple and Hung in the same frame. Both compositions stress the steep stairs leading up the hillside.

Once Hung starts up the stairs, more establishing shots reveal him surrounded. Lau indulges in a feast of different angles, stressing Hung’s vulnerability.

The scene’s second phase follows Hung’s progress up the steps. His encounters with many defenders are captured in a variety of angles, all of them orienting us to the changing situation. (At the top, he’ll encounter Lau himself, wielding a jointed staff.)

Camera setups on the steps themselves keep us aware of the forces arrayed around him. And the steps function a bit like the alleys in other films to limit the range of action.

The camera really penetrates the action, picking out details in the sort of tightly packed framings we saw in Dirty Ho.

Lau remarks: “You can get wonderful scenes of two pairs of hands folding and sliding in and out of each other’s grip.” This sort of tangible physical action is central to Lau’s scene analysis.

Analytical editing can include matches on action, cuts that let movement carry over across shots. Lau gives a virtuoso example in a match-on-action between extreme long-shots of a man in blue sent sprawling. The second shot ends with a zoom back.

It’s possible that Lau used two cameras for coverage of this, but that was a rare option in Hong Kong. It’s just as likely he managed the cut by repeating the fall, a movement stressed by a zoom back.

Again, you get a sense of a filmmaker challenging himself by setting up problems he will need to solve through mastery of his craft.

Editing: Constructive cutting

Trampolines and mattresses in shed on Shaw Movietown lot. Photo by DB.

The wuxia tradition features exponents of the “weightless leap,” the ability to spring very high into space. Before the advent of wirework and CGI, these soaring warriors were treated through editing that shows the leap in a series of shots. For instance, constructive cutting in Chang Cheh’s Golden Swallow (1968, choreographed by Lau) shows Silver Roc launching himself, soaring, and descending on his victim.

The jump was probably facilitated by a trampoline. On the screen, though, we see portions of the action that we assemble in our heads.

With his usual ingenuity, Lau sought out situations where he could test his skill with constructive editing–not just weightless leaps but combats among fighters at some distance from each other. My example is a brilliant sequence from Legendary Weapons of China (1982). (It takes place in semidarkness, so you may wish to adjust the brightness of your monitor.) Two rival assassins clash in a loft as they try to kill a third in the bedroom below. There ensues a three-way fight, pursued mostly through careful constructive editing.

There are a few establishing shots situating Ti Hau and Fan Shao Ching (disguised as a man) in the loft, but once they change their locations, most of the combat is given through constructive editing. That technique relies on cues of setting and character behavior (body position, facial expression, eyelines), and these are all mobilized early in the scene.

Details of props help us understand the action as well: the two threads bearing hooks and especially the gag with gas.

Once the assassin Ti Tan arrives on the floor below, pure constructive editing takes over. There’s no framing that includes him and his two attackers.

So Lau proceeds to cut together an ongoing fight upstairs (complete with fake meows) with Ti Tan’s suspicions downstairs.

The scene culminates in Fan and Ti Hau fleeing as Ti Tan, still suspicious, doubts that all the noise above him was created by a cat–and even the cat is presented through constructive editing.

In a sequence of 126 shots, the average is about two seconds, but each one is legible at a glance and carries the scene forward with utter smoothness. Lau’s precision in shot design serves him well when we have to assemble the action in our minds.

The smash zoom

Hong Kong action films of the 1960s are notorious for their use–some would say, over-use–of zoom shots. Yet at the time directors throughout the world were exploring the artistic possibilities of zooms. Most notable was the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó, who coordinated the zoom with complex movements of actors and the camera. So we ought to consider the possibility that the zoom in Hong Kong was more than a technical gimmick to spice up action scenes.

For example, a smash zoom can accentuates the pause/burst/pause pattern of the fight. During one combat in Chang Cheh’s The Blood Brothers (choreographed by Lau), the zoom emphasizes sudden bursts of action by whipping back from a fighter.

Alternatively, the zoom can play up the pause by calling attention to moments of stasis. Here a cut emphasizes the pause as the fighters’s weapons are locked before the fight resumes with a zoom back.

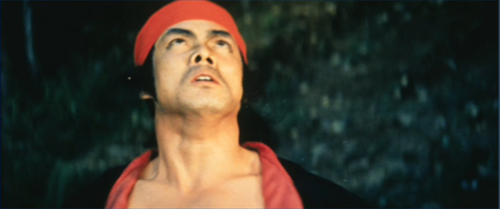

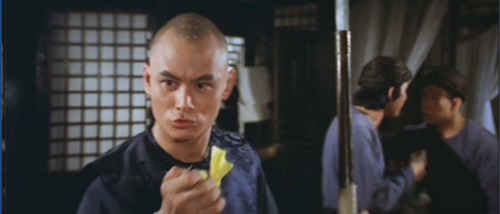

In such ways the zoom can break the fight into discrete stages. A far more elaborate instance takes place in Lau’s Return to the 36th Chamber (1980). Chu Jen-chi has painstakingly learned kung-fu at the temple through an apprenticeship of lashing bamboo poles together to make scaffolding. Accordingly, his technique is based on this very particular set of skills. I concentrate on the early stretches and the clip gives you some extra niceties. The whole thing is exhilarating to behold, thanks partly to energetic zooms.

Early on, the zoom introduces us to the lashing technique by showing the robe’s ripped fabric as a kind of handcuff.

Again we see Lau’s interest in watching how hands work, but here it becomes a specific combat tactic. The ensuing action will revolve around hands and wrists, and Lau’s zooms set up a question: What is Chu’s overall strategy?

The answer comes in a series of variations. First, Chu lashes his adversary to a bamboo pole like captured wild game.

Variation 2: Ensemble work. Chu takes on a batch of men, trussing them up horizontally.

He turns out to have in mind an engineering project, a sort of hitching post of miscreants. It’s capped by a shot of one of the Manchu bullies seeing his disciples’ wiggling fingers.

Variation 3: More ensemble work, now vertical, with the men’s wrists stacked like a bouquet.

Again, a master shot reveals the result and another close-up shows their wiggling fingers.

The kung-fu is of course extraordinary, but it takes an unusual cinematic imagination to heighten such elaborate patterns of movement in ways that are perfectly clear. Chu’s display of serious efficiency has a humorous side, capped by the gags that show the villains utterly flummoxed. We should ask if today’s action sequences in American films have this sort of unforced rigor and exuberance.

In the mid-1980s Shaw Brothers eased out of theatrical filmmaking, devoting Movietown to television production. Lau went on to one-off projects, some of which (e.g., Tiger on Beat, 1988) are well worth your attention. (Go here for the astonishing climax.) He had a late-career resurgence as choreographer for Tsui Hark’s Seven Swords (2005). But his prime achievements, I think, will remain his vastly entertaining and filmically rich Shaws classics. His dedication to the specifics of martial arts lore, his unique sense of comedy, and not least his precise direction brought unique qualities to the remarkable tradition of Asian action cinema.

Chang’s remark about “warm” low angles is in Chang Cheh, A Memoir (Hong Kong Film Archive, 2004), 82; he discusses shooting The Assassin on p. 86. Lau’s comments on Martial Club come from “We Always Had Kung-Fu: Interview with Lau Kar-leung,” in Li Cheuk-to, A Tribute to Action Choreographers (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006), 62; the remarks on hands are on p. 59.

I discuss Lau further in both Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and in this blog entry.

Lau as the drunken master in Heroes of the East (1978).

Little stabs at happiness 5: How to have fun with simple equipment

Tiger on Beat (1988).

DB here:

Simple equipment includes, but is not limited to, knives, pistols, shotguns, ropes tied to shotguns, surfboards, chainsaws, etc.

Herewith another attempt to brighten your days with a choice film sequence that never fails to bring a foolish grin to my face. Apologies as ever to Ken Jacobs for my swiping his title.

Tiger on Beat (aka, but less pungently, Tiger on the Beat, 1988) is prime Hong Kong showboating. This final scene assembles some of the greats—Chow Yun-Fat, Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, Chu Siu-Tung (too little to do)–and near-greats like Conan Lee Yuen-Ba, who gets points for heedlessly executing the stunts Chow and Chow’s doubles can’t. Lau Kar-Leung (aka Liu Chia-Liang), one of Hong Kong’s finest directors, imbues both the staging and the editing with the crisp, staccato rhythm that this tradition made its own, and that few American directors have ever figured out. (It’s a long clip, so it may take a little time to load. In addition, our Kaltura operation is having problems, so you may want to try different browsers.)

Come to think of it, this little-stabs entry contains some fairly big stabs of its own.

The whole film is worth a look. Opening scenes feature Chow in outrageous threads, the very opposite of a cop in plainclothes, and there’s a fine car chase in which many risk life and limb. But this sequence, lit high-key so that every splash of saturated color pops, is for me the highlight, a tour de force of action cinema. Probably not for the kids, but what do I know about kids?

Sequences like this were what drove me to teach Hong Kong film and write Planet Hong Kong. They also impelled Stefan Hammond and Mike Wilkins to write Sex and Zen and a Bullet in the Head (1996), the most deeply knowledgeable fanguide to this glorious cinema. Stefan followed it up with Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who Made Them (2000). Now Stefan and Mike have effected a merger of these and updated and expanded them. They’ve also recruited a band of other Guardians of the Shaolin Temple: Wade Major, Michael Bliss, Jeremy Hansen, Jude Poyer, David Chute, Dave Kehr, Andy Klein, Adam Knee, Jim Morton, and Karen Tarapata.

The result is another indispensable volume, More Sex, Better Zen, Faster Bullets: The Encyclopedia of Hong Kong Film. The recommendations are sound, the plot synopses are nearly as much fun as the movies, and the authors have wisely retained chapter titles like “So. You think your kung fu’s. . . pretty good. But still. You’re going to die today. Ah ha ha ha. Ah ha ha ha ha ha.”

They weigh in on today’s sequence: “This gory Armageddon-duet consistently scores on Top Ten End-Battle Lists among HK film aficionados.” Makes me even more confident to recommend it to you. They add that the credits music is “a hard-rocking theme song by HK power diva Maria Cordero.” So I let it run.

I analyze this and other action sequences in this blog entry. An appreciation of Lau Kar-Leung is here.

For more little stabs, check out earlier entries in this series.

Chow Yun-Fat gets his daily dose of egg yolks (Tiger on Beat).

Lion, dancing: Lau Kar-leung

Martial Club (1981, Lau Kar-leung).

“It’s too late. We don’t need stuntmen any more. We have computers.”

Lau Kar-leung

DB here:

Lau Kar-leung (in Mandarin: Liu Chia-liang), who died last week, was one of the best filmmakers of the 1970s and 1980s. Yet he remains largely unknown in the west.

Why? He made Hong Kong martial-arts movies, a genre long despised by upscale cinephiles. His career took off after the kung-fu boom in America and Europe had ended, so his films didn’t get wide circulation abroad. Worse, he worked for Shaw Bros., the studio decried as a soulless movie factory. (Oddly, his best films coincided with the decline of the studio’s output, as Run Run Shaw turned his attention more to television.) In Asia Lau’s films had to compete with the rising popularity of Golden Harvest’s fast, slick new films starring the Hui brothers, Sammo Hung, Yuen Biao, and Jackie Chan. And he largely missed the shift to the modern urban action picture that helped Hong Kong films into world markets in the late 1980s. Even though he made the remarkable cop movie Tiger on the Beat (1988), he never fully embraced the bloody-brotherhood ethos epitomized in the work of John Woo.

Before he became a director, Lau was a martial-arts choreographer. Credits list him on over 125 films, though he claimed to have worked on more than two hundred. He came into his own as an action choreographer in 1962, when he was about twenty-five. He worked for companies turning out both Cantonese and Mandarin martial-arts films. The film that brought him to attention was The Jade Bow (1966), made for the Great Wall company. This rattling effort, choreographed by Lau and his frequent collaborator Tong Kai, made ingenious use of wirework and reverse-motion effects.

The Jade Bow, hard and spare in its style, was strikingly similar to the new wave of martial arts films announced with great fanfare by the Shaws studios in the same year. Soon Lau became a major Shaws choreographer. Usually paired with Tong, he collaborated on many of Chang Cheh’s flamboyant, aggressive action pictures, including The Assassin (1967), One-Armed Swordsman (1967), Golden Swallow (1968), New One-Armed Swordsman (1970), Blood Brothers (1973), and Disciples of Shaolin (1975). Lau might stage fights for sixteen different releases in a single year.

Lau and Tong complemented one another. Lau grew up in a martial-arts household and learned classic technique from his father. Tong came from Cantonese opera, eventually working as a stage stuntman. To his film work Tong brought acrobatic styles and a deep knowledge of weaponry that helped him design eye-catching swords and spears. The two worked out fights together, one playing the protagonist, the other the antagonist. In 1975, Lau became a director while Tong continued to choreograph other projects.

Lau began directing just as the kung-fu boom needed something to spice it up. Bruce Lee had introduced serious, even melodramatic combat. Chang Cheh had continued in this vein while emphasizing agonizing violence, homorerotic tensions, and plots based on Shaolin temple legends. Soon Chang would innovate along a different dimension by presenting circus-like, almost camp extravaganzas centered on the Five Deadly Venoms team.

A dash, or more, of laughs

Lau’s directorial debut, The Spiritual Boxer (1975), is often considered the first kung-fu comedy, and many of his films include mugging, goofy dialogue, and physical gags. He went beyond one-off humor by finding ways to make combat itself funny. In Dirty Ho (1979) two masters maintain teatime manners while trying to thrust goblets, fans, and fingers into each other’s face (above). My Young Auntie (1981) features a demure heroine who is, to everyone’s surprise, an adept at kung-fu. Heroes of the East (1978; my preferred title: Shaolin vs. Ninja) rests entirely on a comic premise. A Chinese man marries a Japanese woman, but soon they quarrel about which nation has the stronger warrior tradition. Broken furniture follows. Even Legendary Weapons of China (1982), an attempt to present the Boxer Rebellion, can’t avoid spectacular gag scenes in which a magic doll is twisted to manipulate a fighter into grotesque positions.

Lau’s emblematic actor, as central to him as John Wayne was to Ford or James Stewart was to Anthony Mann, was Lau Kar-fai (Liu Chia-hui), familiarly known in Western circles as Gordon Liu. Sometimes bald, sometimes bearded or mustached, Liu can play hayseed, shirker, reluctant hero, con man, or elder sage. His breakout role came in one of Kar-leung’s most famous films, 36 Chambers of Shaolin (1978), which was given a comic sequel as Return to the 36th Chamber (1980). But there’s nothing funny about the ferocity of The 8-Diagram Pole Fighter (1984), which begins with a theatrically abstract representation of a battle and ends with Gordon Liu rescued by monks who bash in the teeth of their adversaries.

Lau brought to the action genre a fierce athleticism, a tireless energy—some of his films contain a dozen combats, big and small—and a thorough acquaintance with many martial-arts schools. A film might showcase one fighting style or several. At the climax of Legendary Weapons Lau himself steps in to perform virtuoso moves with a variety of spears, chain whips, daggers, swords, and staffs. Heroes of the East sets seven Japanese masters, each with a martial specialty, against our young Chinese husband, and the film provides virtually a compare-contrast essay in Asian combat tactics. Sometimes one thinks that Lau was aiming at nothing less than a filmic encyclopedia of classic martial arts, a sort of audiovisual database of the entire Chinese wuxia tradition.

This shouldn’t be taken to mean that his filming was straightforward. Lau had tremendous cinematic gifts. Staccato figure movement, often integrated with punchy zooms, give his scenes a racy, infectious pulse. Although he usually stays far enough back to capture the entire action, he cuts very fast, averaging four to five seconds, but his careful ‘Scope compositions and smooth match cuts keep the action intelligible. The frame teems with movement. A pole may jab into the foreground, and his fighters may pop up from the bottom or sides of the frame. Starting from a detail, a zoom-back can create a whooshing burst in the manner of a comic-strip splash panel. These conventions of local cinema were made especially gripping by their integration with the distinctive maneuvers of each fighting mode.

The Hong Kong tradition relies on rhythmic staging and cutting, but Lau took things further than most. Even in scenes not centered on combats, he found ways to make movements counter each other, cut for cut, or to flow from one figure to another across the scene. Motion often becomes contagious, with one man’s gesture followed by another man’s rhyming head turn or sudden twist of a torso. Fighters prowling in a darkened attic in Legendary Weapons are intercut with their target in the floor below; his abrupt gestures and pauses are echoed by theirs.

Once Lau found his stride, he seemed to make every film an experiment in rendering kung-fu’s most esoteric traditions through the resources of purely cinematic rhythm.

His most sustained output ran from 1975 to 1985, although he directed sporadically thereafter. His last directed film, Drunken Monkey (2003), failed to attract attention, but he remained the honored elder consulted by younger directors. Jackie Chan engaged him for his Drunken Master II (1994) and Tsui Hark hired him for Seven Swords (2005).

Let’s get unreal

Almost always, I tend to think, the quest for realism in cinema is misguided. Realism is often just an alibi for the brand of artifice we prefer. The great “realist” movements in cinema did access certain aspects of the world that were overlooked by other trends, but they treated those aspects through new conventions. From Soviet Socialist Realism through postwar American “semidocumentary” shooting and Method acting to Neorealism and onward, fresh forms replaced, or reworked exisiting ones. Reality is multifaceted, and any style can be said to be faithful to some facets of it.

It might be nice if our filmmakers working outside the realm of comedy acknowledged artifice more frankly. Today, watching the “realistic” action scenes of World War Z and others like it, with their choppy cutting, murky staging, and grab-and-go framing, I’m reminded not of their excuse (to render “the way characters feel”) but of their overarching purpose: to obtain a PG-13 rating. The new conventions aim to hide the action rather than display it.

That demand keeps many of today’s action films from being precisely and percussively arousing. We’re supposed to be satisfied with a vague excitement. Our films project a manic, diffuse busyness, an effort to suggest lots going on without ever specifying exactly what it feels like to run, to fall, to hit a wall, to feel a blow—in short, to face the stubborn physicality of the world. Those effects can, paradoxically enough, often be best activated by highly stylized cinema.

Consider the chainsaw climax of Lau’s Tiger on the Beat, which I’ve analyzed in an earlier entry. Even in this YouTube video, it retains a lot of its impact.

Yes, it’s over the top. Yes, it employs Hong Kong Physics. No, it wouldn’t get a PG-13. But every image and sound is focused to achieve crisp excitement. It’s very fast without being confusing. The use of film technique is cogent, inventive (how many ways to wreck a paint shop?), and stirring. And a little funny too.

It’s not realistic, but it knocks you upside the head. You either laugh or gape, but you can’t say you felt nothing. Stylization, in other words, is one path to powerful expression, and even exhilaration. Nobody understood that better than Lau Kar-leung.

On Lau Kar-leung and Tong Kai, my primary source has been A Tribute to Action Choreographers, ed. Li Cheuk-to (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006), 44-63. An engaging appreciation of Lau can be found in Bey Logan’s Hong Kong Action Cinema (Overlook, 1996). Logan has also provided informative commentary on many Lau films for the Dragon Dynasty DVD series. Stephen Teo discusses the sexual/ erotic side of Lau’s films in his indispensable Hong Kong Cinema (British Film Institute, 1997), 104-109. See also John Charles’ very useful Hong Kong Filmography, 1977-1997 (McFarland, 2000).

An enlightening interview with Lau is at Ric Myers’ Martial Arts in Media site.

As usual, the Hong Kong Movie Database is the primary online source for material on this wondrous cinema. Thanks to Ryan Law for building this great resource. Thanks also to Ross Chen of Lovehkfilm, a great source of news and reviews, for his many years of friendship and his dedication to the cause.

Gordon Liu (Lau Kar-fai) is often spoken of as Lau Kar-leung’s brother. Actually, they are not blood relations. Gordon was the godson of Lau’s father, and he was trained in martial arts by Lau Kar-leung. Thanks to Li Cheuk-to for help in clarifying this.

We owe a debt to Celestial Pictures, the company that acquired and remastered the classic Shaw films in mammoth quantities. Apart from the tweeting birds that seep into too many soundtracks, the restorations have been gorgeous and allow us to rediscover films that for decades were virtually impossible to see.

Several other entries on this site analyze Hong Kong filmmaking. Jackie Chan takes on James Bond here. I discuss Hong Kong’s use of anamorphic widescreen here. See also the daily series that started here and ended here. I discuss Lau Kar-leung in relation to King Hu and Chang Cheh in Planet Hong Kong 2.0.

In a related development, the new American Cinematographer (July 2013) contains an article in which Gil Hubbs, DP for Enter the Dragon (1973), provides lots of information on how that pivotal film was made. The piece is not yet available online.

Maybe just as tangential, an interview with me at last year’s FanTasia festival is on video here and transcribed here (rambling intact). Both touch on matters of martial-arts filmmaking. Thanks to David Hanley for all his work in bringing this to pass.

Of recent Hollywood action films the one I’ve seen that comes closest to the Hong Kong aesthetic is Steven Soderbergh’s Haywire.

P.S. 2 June: Thanks to Shawn McKenna for a correction!

Lau Kar-leung practicing drunken kung-fu in Heroes of the East (1978).

Bond vs. Chan: Jackie shows how it’s done

DB here:

During the 1990s several critics began to notice that filmmakers were doing something odd with action scenes.

Directors were consciously, even joyously, sacrificing clarity. When two characters were punching it out, the framing didn’t make it easy to know who was hitting whom, and how. Changes in angle and shot scale were sometimes so abrupt that you had little time to adjust. The cutting pace was so quick that you couldn’t entirely register the movement in shot A before shot B replaced it. Sometimes the spatial layout of the fight was confusing as well: too many close views, too few master shots. Later, the return of handheld shooting made many action scenes even more illegible, blurring and smearing them to the point that sound (as in the Bourne films) had to specify that a body has hit a window or a hand has busted a bottle. Now we have Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables, which might be a new summit in overbusy, incoherent, inconsequential action.

I wrote about this trend back in the 1990s, and I’ve returned to it on occasion since. Other writers, notably Todd McCarthy of Variety, noticed it too. He referred to the full-throttle editing and “frequently incoherent staging” on display in Armageddon (1998): “Bay’s visual presentation is so frantic and chaotic that one often can’t tell which ship or characters are being shown, or where things are in relation to one another.”

A decade later comes Peter DeBruge’s review of the “muddled execution” of The Expendables: Staging simultaneous fights “might’ve worked had the editors assembled all that footage in such a way that we could tell where characters are in relation to one another or what’s going on.”

The Michael Bay approach has become the principal way in which action scenes are shot. It isn’t absence of craft that leads to these aimless bouts. The filmmakers actively want the action to be hard, even impossible, to follow. Sometimes I think that this blurred bustle is there to secure a PG-13 rating; if you could really see the mayhem, we might be moving toward an R. But filmmakers don’t say that they’re self-censoring. They seem to think that making the action illegible is creative because it promotes realism.

Stallone explains why he scrambled up the fight scenes in The Expendables.

I don’t think many action scenes are shown from the character’s point of view. They are more from the director’s point of view. On Rambo, I thought the most economical and original way to shoot [the action] would be through Rambo’s eyes—if he were directing, what would his style be? But The Expendables is an ensemble picture, so it’s somewhat of a blend. I thought, ‘This is not supposed to hang in the Louvre.’ I wanted it to be disjointed and rough, not choreographed. If you really were filming a big battle with five cameras, [their footage] would not all flow together, so we set up the [cameras] to film the action we’d scripted and told the operators they were on their own. We said, ‘Do the best you can, and we’ll use the interesting shots from the characters’ perspectives.’”

Camera operator Vern Nobles describes shooting the action as “multi-camera craziness.”

You might point out that if somebody were really filming a big fight with five cameras, at least a couple of camera operators would be shot or punched silly. And presumably a few times we’d actually see other cameras.

Realism, as usual, is simply a fig leaf for doing what you want. Virtually any technique can be justified as realistic according to some conception of what’s important in the scene. If you shoot the action cogently, with all the moves evident, that’s realistic because it shows you what’s “really” happening. If you shoot it awkwardly, that presentation is “realistically” reflecting what a participant perceives or feels. If you shoot it as “chaos” (another description that Nobles applies to the Expendables action scenes)—well, action feels chaotic when you’re in it, right?

Forget the realist alibi. What do you want your sequence to do to the viewer? Do you want it to pass along an impression of bustle and flurry? Or do you want to make the viewer wince, recoil, even mildly reenact the movements of the players? Then follow the Hong Kong tradition. Yuen Woo-ping once told me that his goal was to make the viewer “feel the blow.” To convey the effort and strain, the impact and pain: that’s something worth doing.

It’s something that the blur-o-vision tussles lack, but even fights that are more carefully filmed are strangely unmoving. In Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), there’s a fistfight on a catwalk above a rotary press line. The presentation is more or less spatially unified, but it lacks drive because of certain creative choices. For instance, when Bond punches a security guard, the man simply drops out of the frame.

Where does he go? He doesn’t fall off the catwalk but seems to grab the railing, so maybe he’ll return for another go-round. But he doesn’t. As Bond falls back, another guard sneaks up on him. The framing and screen direction suggest that he’s approaching Bond from the front.

Actually, he’s sneaking up from the rear.

When Bond turns, we don’t see his punch.

In fact, we don’t see much of anything. Although the attacker is erect in one shot, he seems to be kneeling in the next, when Bond kicks him, somewhere below the frameline.

The attacker is standing again in the next shot, and he’s flung backward by the force of Bond’s unseen kick.

When the man returns, he tries to tackle Bond. At least, I think he does. The maneuver takes place, again, underneath the frameline.

At last we get a wider shot, but this serves mainly to align the fight with the conveyor belt below the men; guess who will fall?

More fighting, with punches and grappling blocked by the men’s bodies, culminates in Bond’s adversary falling into the print run.

Even here, however, we don’t really see what happens to the victim. He plunges through the river of newsprint and the machine starts belching.

Overall, we get a mild impression of what happened in the fight, but the action unfolds vaguely and is hardly stirring. Is this how you earn a PG-13?

The Hong Kong way

Righting Wrongs (1986).

While revising Planet Hong Kong for its web edition, I’ve been revisiting classic Hong Kong action scenes. In 1997-98, when the book was written, I had to rely on laserdiscs, but since then I’ve been able to look at more 35mm prints. (DVDs usually don’t help answer the sort of questions I’m asking, for reasons reviewed here.) Now I have a chance to put some thoughts about these movies online, in this blog and in the upcoming digital update of the book. As a start, here’s a recipe drawn from the best of Hong Kong fury.

First, go for clarity in every way. Not murky earth-toned sets but brightly colored and sharply lit ones; even an alley can dazzle. Put the camera on a tripod; pan if you must, but save your dolly moves for simple emphasis. No handheld.

Second, aim for precision. Stallone’s comments imply that a cameraman captures a preexisting fight, snatching an “interesting” shot here or there. But that’s not the case. Movie action is choreographed and the framing is calibrated to that. The gestures should be legible, favoring crisp and staccato movement, while the image’s composition aims to convey the action cleanly. It’s a pity that the haphazard framing of Stallone and his cameramen have ruined the choreography of Cory Yuen Kwai, Jet Li’s action designer (and a fine director in his own right).

Third, establish a rhythm. This involves not only building the fight. It also involves synchronizing the pace of characters’ movements with that of the cutting. On the whole, the old rule applies: More distant shots should be held longer than closer ones. This doesn’t mean you can’t use fast cutting, only that your fast cutting can be more finely judged when you take shot scale, composition, and speed of movement into account.

Rhythm means sensing a pulse, and for that you need slight pauses. So don’t cut away to something else before a punch or kick is completed. Let the arc of movement, itself perhaps stretched over several shots, come to a point of rest, if only for a couple of frames.

Fourth—and here is where realism is most explicitly abandoned—amplify the expressive qualities of the action. If movement is zigzag or springy or oscillating, stress that. Give emotional qualities not only to facial expressions but also to postures and combat moves. American heroes just grimace while their bodies remain inexpressive, lumpish. The hard guys in The Expendables might as well be made of granite. But in contrast your fighters needn’t wave their arms wildly. Just concentrate energy and emotion in the action. If the hero attacks, let him become as focused as a javelin. If your heroine falls, don’t let her just drop out of frame: Let her land with a thwack, preferably on the spine or neck, and let her body’s recoil send a spasm through the spectator too.

Hong Kong cinema supports Sergei Eisenstein’s belief that expressive human action is “infectious.” He thought that if physical action onscreen is imbued with vivid force it can arouse sympathetic echoes in the spectator’s own body. After a great action scene, such as in many Chang Cheh and Lau Kar-leung films of the 1970s, or in Yuen Kwai’s Righting Wrongs, when a tough guy gets a spittoon in the face, the viewer feels trembling and tired, but in a good way.

Glass story

Jackie Chan has become such a beaming, easygoing star that we forget that he was an excellent director of brutal fight scenes. He proved adept at filling anamorphic compositions with dynamic movement, as well as plucking out items of a set and sweeping them into the action. (See the parlor fight in Young Master, 1980, or the shenanigans in the rope factory in Miracles/ Mr. Canton and Lady Rose, 1989). In Police Story (1985), Jackie is trying to rescue Salina and save all the computer records in her briefcase. Koo’s gang is determined to stop him. The fight moves through different areas of a shopping mall.

In each of these locales, Jackie plays a suite of variations on what you can do with escalators, staircases, and, most memorably, glass. I can’t do justice to all the skirmishes, but consider some instances of how he stages and cuts the action for an impact that American movies seldom achieve.

The variations get steadily more elaborate. Early in the sequence, Jackie flings one thug, achingly, across the bottom handrails of an escalator.

The shot could hardly be more legible. You see everything. Next, Jackie is grabbed from the rear.

Naturally he has to flip his attacker down to the floor below, rendered in two dynamic shots from directly below and above.

Interestingly, the shots are so clearly composed (even with the fancy mirror effect in the second) that they can be very brief: 26 frames and 16 frames. Down at the bottom, the unfortunate fellow smashes through a display and lands straight on his spine. Unlike the security guards in Tomorrow Never Dies, this thug gets a little commiseration as he rolls over groaning. As in any fight sequences, disposable thugs may come back into action, but at least we’ll clearly see the fates of those who are put permanently out of commission.

After this burst of action Jackie provides a pause as he abruptly looks up in search of Salina.

What else can you do with escalators? How about tossing the next thug down the slim gap between two of them?

In a nice touch, we hear a long squeak as he slides down the trough.

Tomorrow Never Dies sets up its conveyor-belt climax straightforwardly, but Jackie’s choreography is more surprising. Audacious and imaginative as the stunts are, however, they are framed and cut in a way that makes the action clear and precise. Through cinematic choices Chan builds up an infectious arousal. This stuff hurts.

After a set-to in a hallway, Jackie pursues the gang into an area filled with display cases. He takes on the men ferociously, and sets them smashing through the vitrines in another string of variations. Jackie slams down a mirror on one thug, swings another into a display, and sends one spinning through a window. Each shot, of course, is of diagrammatic simplicity, all the better to amplify the expressive dimension and key up the viewer. You can’t watch shots of men hurled into layers of glass without feeling a few palpitations.

Nearly every shot is bound tightly to the next. What will occupy shot B is launched on the fringes of shot A, sometimes for only a few frames. The string of matches on action creates a fluid continuity quite different from the choppiness we often find in American sequences.

A good instance occurs after Jackie has been pinned under a toppled shelf. In a medium close-up, the gang leader orders his thug into action; behind him the plaid-coated thug moves left.

In long shot, with Jackie at a disadvantage, the thug continues his movement in the background as he grabs a heavy statuette.

In a medium-shot, Mr. Plaid Jacket lifts the statue, but as he moves aside he reveals Salina rushing toward him in the background. Look quick: She appears in the fifteenth frame, and is gone within another fifteen.

We can only glimpse Salina passing behind the thug, but the next shot shows her clearly: running, baseball bat in hand, toward him. The trajectory could not be clearer, and she swings the bat directly through the vitrine.

The force of the action is multiplied by the simplest cut possible: an axial enlargement, with the action slightly repeated and slowed. The first shot of Salina’s swing lasts seventeen frames, the second exactly twice as long. The arithmetic of the cutting extends the action’s beat.

Bursts of glass form the dominant, painful motif of this part of the sequence. (Jackie’s crew suggested he call the film Glass Story.) The shifting dynamic of the fight is rendered through close encounters of the splintery kind. But these are differentiated. Long shots portray the torments of the gang, but Jackie’s first encounter with glass is treated in one simple close shot, just a second long, that usually makes audiences flinch.

Jackie is attacked by the gang leader and he shoves Salina out of the way.

The leader springs forward to whack Jackie with the briefcase.

Cut to the opposite angle, a tight shot of Jackie.

The briefcase continues to be swung, and Jackie’s head smashes the windowpane.

Jackie bounces off the glass and grimaces in agony.

The proximity of the glass shards to his eyes probably triggers some primal revulsion in us, but this is only part of the image’s force. The whole shot lasts only 28 frames. I think that part of its percussive impact comes from the fact that at the start we don’t have time to register that the pane is there. (There are only seven frames before Jackie hits.) When the glass bursts, it’s as startling as if the screen surface has cracked as well, and this amplifies the painful impact of the blow.

For a time Jackie is at the gang’s mercy. But he makes a comeback, and eventually in a kind of summary of his other maneuvers he will bash the leader, body and head, through two glass cases. This phase of the scene concludes with Jackie running Mr. Plaid through a series of cases at the point of a motorcycle. Both crescendos are filmed in clear, smoothly-cut shots—and long shots at that.

We may wince for the fate of these gangsters, but we shuddered when we saw Jackie’s face knocked through a window. Soon Jackie will be flipping the leader down an escalator, a sort of envoi to the scene’s first phase, and he will be sliding down a three-story light pole to catch up with boss Koo himself.

To use Stallone’s comparison, I’d happily hang this splendid sequence in the Louvre.

But what sort of MPAA rating would it receive today? The painful physicality on display is given a staccato force through the framing and cutting. And don’t call it cartoonish. It’s Bond who’s cartoonish, with his unflappable ease and perfectly functioning gadgets and defiance of the laws of gravity and those fights he wins without suffering a scratch. Jackie shows us the sweat. He and his victims fall with painful awkwardness, he gets gashed and bruised, and he’s all too vulnerable to physics (or at least Hong Kong physics). Bond wins through debonair resourcefulness and a lot of luck. Jackie wins by refusing to lose.

He refuses to lose the audience too. In Police Story Jackie’s manic urge to make the scene maximally gripping is itself a little scary. Nonetheless, when a director isn’t afraid of tapping the real power of movies, a fight scene can give us an adrenalin transfusion. Who needs 3-D? Maybe only weak directors.

For other discussions of Hong Kong action scenes, see my “Aesthetics in Action: Kung-Fu, Gunplay, and Cinematic Expression” and “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse” in Poetics of Cinema. There are some other examples in my online essay on Shaw Brothers. My most ambitious efforts in this direction are in Planet Hong Kong, where I take up the issue of rhythm in more detail than I can here. Alas, many contemporary Hong Kong action scenes have learned bad habits from Hollywood. I’ll talk about the decline of crisp fight staging in the new edition of PHK, due online in early December.

Todd McCarthy’s 1998 review of Armageddon is here. Peter DeBruge’s review of The Expendables is here. Both may lurk behind a paywall. The coverage of The Expendables I mention is Michael Goldman, “War Horses,” American Cinematographer 91, 9 (November 2010), 52-56. The pilot online issue is here.

The Dragon Dynasty version of Police Story includes Bey Logan’s conversation with Brett Ratner. During the commentary, Ratner notes that Jackie holds his shots longer than would an American director, who would be likely to cut on every punch. Incidentally, I’ve found many DD releases of Hong Kong films to be superior in quality to other DVD versions, and Logan’s commentaries are information-packed. His book Hong Kong Action Cinema remains a fine piece of work.

The images from Tomorrow Never Dies are taken from DVD, with all the drawbacks of that format for close analysis. But I don’t think my conclusions would vary if I worked from 35mm. The Police Story frames are analog frame enlargements from a 35mm print and allow accurate frame-by-frame analysis. Even then, Jackie’s pacing is so fast that blurring is inevitable. Thanks to Heather Heckman for her assistance in turning my slides into digital files.

PS 17 September 2010: I forgot to mention that Matt Zoller Seitz has provided two of the most discerning (and hilarious) critiques of the Michael Bay High Rococo Action Style, here and here.

Young Master.