Archive for June 2017

Ritrovato 2017: Drinking from the firehose

DB here:

Immense scale and teeming activity are nothing new to Il Cinema Ritrovato, the Cineteca di Bologna’s annual jamboree of restored and rediscovered films from all over the world. The scorching heat–90 degrees and more for the first few days–only makes it seem more intense than usual.

Kristin and I had to miss the last Ritrovato session, but we’re convinced that this nine days’ wonder is still the film-history equivalent of Cannes.

In one way, your choice is simple. You can follow one or two threads–say, the Robert Mitchum retrospective or the Collette and cinema one or the classic Mexican one, or whatever–and dig deep into that. Or you can skip among many, sampling several, smorgasbord-style.

In practice, I think most Ritrovatoians pursue a mixed strategy. Settle down one day for a string of, say, early Universal talkies and another day check out the restored color items. On off-days roam freely. The problem is you will always, always miss something you would otherwise kill to see.

At the start, I plumped for 1910s films, particularly Mariann Lewinsky’s reliable 100 Years Ago cycle. My other must was the Japanese films from the 1930s; half of the titles brought by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, were new to me. As of this writing, I haven’t seen those, but I have dug into the 1917 items. And I indulged myself with, no surprise, some gorgeous Hollywood things.

1917 and all that

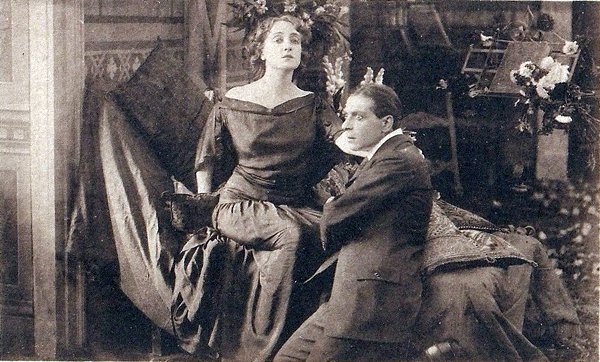

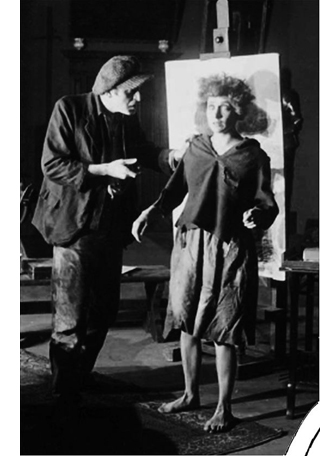

Malombra (1917).

If you caught any of my dispatches from Washington DC earlier this year (starting here) you know I was burrowing deep into American features of the 1910s That complemented several years of archival work on European films of the same period. So of course the chance to sample 1917 features from Hungary, Poland, Russia, and elsewhere was not to be passed up.

Some superb ‘teens films I just skipped through familiarity. Gance’s Mater Dolorosa (1917), possibly the most patriarchal film in the thread, remains tremendously inventive at the level of silhouette lighting and continuity cutting (a huge variety of camera setups during the fatal love tryst). And one of the very greatest directors of the period, Yegenii Bauer, was represented by two of his last films, The Revolutionary and Towards Happiness. I’ve studied both elsewhere, in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and online. Even so, I found plenty to keep me busy.

One of the main threads was devoted to Augusto Genina, a director with an astonishingly long and prolific career. Probably best known for Prix de Beauté (Miss Europe, 1930), he started in 1913 and made his last film in 1955. His 1910s films confirm that Italy was producing many films of striking beauty and audacity in those years.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

Take Lucciola (1917, right), the story of a waif who befriends a harbor layabout but leaves him to become a society princess admired by a debonair painter and three bulbous plutocrats. Pivoting from social satire to low-life melodrama, the film makes use of bold lighting and meticulous cutting, usually along the lens axis. (Like many European films of the ‘teens, Lucciola lies sort of between tableau cinema and the faster-cut American style.) All in all, a strong, tight movie.

In a similar vein is Addio, Giovenezza! (1918), adapted from a popular song. This one, screened in an open-air venue thanks to an arc-lamp projector, is another sad Genina tale. A careerist law student abandons his rooming-house maid for a social butterfly with a wardrobe to die for. Apart from one startling scene in a milliner’s shop, illuminated mostly by spill from the street, the lighting isn’t as daring as in Lucciola. Still, the poignant plot is again inflected by comic touches, proceeding largely from the hero’s nerdish fellow student. Genina redid the story again in 1927, and I’m hoping to catch that screening.

Malombra (1917), starring the diva Lyda Borelli, was by the great Carmine Gallone. (I’ve discussed La Donna nuda and Maman poupée hereabouts.) After moving into a castle, Marina becomes possessed by the spirit of the woman who died there. Our heroine’s job is to take revenge on the faithless husband. Flirtatious and iron-willed, Borelli dominates her scenes with shifts of stance, sudden freezes, rapid changes of expression, languorous arm movements, and, at one climax, a swift undoing of her hair that lets it all tumble wildly around her face. The print, needless to say, was superb.

In a lighter vein, if you wanted proof of the inventiveness of ‘teens Italian film, you couldn’t do better than Wives and Oranges (Le Mogli e le arance; 1917). This agreeably silly movie sends a bored young man to a spa populated by incredibly aged parents and a bevy of scampering daughters. With an avuncular friend, Marcello capers with the girls before settling on the most modest one as his wife. But her friends aren’t disappointed because our hero’s pals come for a visit and get roped into matrimony too.

Wives and Oranges has a remarkable freedom of narration. The film uses montage sequences with a fluidity that is rare at the time. To convey the boredom of Marcello’s daily routine, a string of quick shots is punctuated by changing clock faces. Later, the idea of finding one’s ideal love mate by matching halves of oranges is presented via an absurd montage of old folks, youngsters, babies, and just abstract hands, all wielding oranges.

Marcello’s paralyzing dilemma of choice is given as a nondiegetic insert of a donkey unable to decide between a hay bale and a bucket of water. These flashy devices keep us interested in a situation that, in script terms, is probably stretched too thin–although when things slow down you can count on the daughters forming a chorus line and zigzagging down the road or popping out from under the dinner table one by one.

Almost as lightweight was The War and Momi’s Dream (La Guerra e il sogno di Momi, 1917), by the great Segundo de Chomón, who moved among France, Spain, and Italy making fantasy films of many types. This one is largely meticulous puppet animation, in which a boy’s toys come to life and enact–at the height of the World War–their own combat.

Trick and Track marshall other toys to play out some seriocomic clashes, including a burning farmhouse and one astonishing shot of an entire town landscape, covered in a long camera movement. Again, there’s no underestimating the sheer technical audacity of Italian cinema of these days.

There’s always an exception, of course. The late David Shepard left us, among much else, Shepard’s Law of Film Survival: The better the print, the worse the movie. A good example is La Tragica fine di Caligula Imperator (1917), signed by Ugo Falena. It’s surprisingly retrograde for an Italian film of the period. Neither the staging (flat, distant) nor the cutting (minimal) nor the lighting (little modeling) is much in tune with contemporary norms. The problem may be the immense sets, which are indeed impressive but which seem to encourage the actors to a hard-sell technique.

The most amped-up is Caligula himself. Playing a mad Roman emperor often tempts any actor to gnaw table legs. But as an example of what a silent film really could look like, Caligula should be required viewing for anybody who sneers at Those Old Movies. If Christopher Nolan saw it, he’d demand to shoot on orthochrome nitrate.

Other 1917 features included The Soldier on Leave, from Hungary, and Stop Shedding Blood!, by the great Russian director Jakov Protazanov. The former was restored from a 17.5mm copy, the latter was missing the two central reels. The Protazanov in particular had some sharp staging in depth and rich sets.

In the same batch was Pola Negri’s screen debut in Bestia (1917, imported to the US as The Polish Dancer). In a fine copy, you could appreciate the bouncy but sultry screen presence that made her a star. And as often happens with films from anywhere in this period, the sets sometimes play peekaboo with the action. Pola, after a night out with her thuggish lover, sneaks back to her bed while her father snores in the background, caught in a slice of space.

Back in the USA

Kid Boots (1917).

The 1917 American entry was a strong, unpretentious Western by Frank Borzage, Until They Get Me. It’s missing some scenes in the middle, but it remains a forcefully quiet movie. The only gunplay takes place at the start, when a man racing to get to his wife in childbirth is forced into a gunfight. He kills the drunkard who provoked it, but by the time he reaches his home, his wife is dead. Now he must flee Selwyn, a mountie. Stealing a horse, he picks up an orphan girl fleeing an oppressive household. The rest of the film will intertwine the fates of the three, leading to a surprisingly civilized resolution.

Borzage is one of the many great directors–De Mille, Dwan, Walsh, Ford, Brown, King, Barker–who started doing features in the mid-teens. Most had long careers. They mastered the emerging norms of Hollywood continuity cinema and learned to deploy them with tact and precision. Just the timing of the reaction shots in Until They Get Me is worth study.

Frank Tuttle started in features a bit later, in 1922, but Kid Boots (1926), my first movie of the Ritrovato, showed complete mastery of comic storytelling. Eddie Cantor, a fired tailor, becomes amanuensis to Tom Sterling, a man-about-town in the throes of a divorce. The twist is that his wife, learning of Tom’s new inheritance, wants to halt the divorce by sharing his bed again. Eddie’s job is to keep the wife and the lawyers at bay until the divorce becomes final. Into this tangle plops perky Clara Bow in her first film after her breakout role in Mantrap (also 1926). You could watch her cock her chin and roll her eyes for hours. She steals the picture from Billie Dove.

The gag situations come thick and fast, with one high point being Eddie’s efforts to get Clara jealous by recruiting a strategically open door to help him pretend that his left arm actually belongs to Tom’s seductive wife. The whole thing culminates in a breathless chase on horses along a treacherous mountain pass. Eddie and all the others keep things lively, and Tuttle’s direction is exacting.

I strayed from the ‘teens again at Dave Kehr’s urging. Of Dave’s magnificent MoMA restorations, I caught William K. Howard’s Sherlock Holmes (1932). Apart from a wild-eyed Ernest Thesiger and an imperturbable Clive Brook, it boasts an abstract opening of silhouettes and confrontational close-ups and a conclusion of percussive flashes as Moriarty’s gang torches its way into a bank.

Ace cinematographer George Barnes had a field day with this one.

That was followed by Tay Garnett’s Destination Unknown (1933), a tense drama of a crisis on a bootlegging ship immobile on a windless sea. Hard, fast playing by Pat O’Brien and Alan Hale was offset by the leisurely presence of none other than Ralph Bellamy, aka Jesus of Nazareth. Don’t ask; just see it.

More from me, and Kristin, later in the week.

Thanks to Guy Borlée for a great deal of assistance on this entry. Thanks as well to the programmers and staff of the festival, especially Gian Luca Farinelli and Mariann Lewinsky.

The Ritrovato site is constantly updated. For our earlier Ritrovato communiqués, go here.

Malombra (1917; production still).

Grand motel

One Crowded Night (1940).

DB here:

If this blog got into the business of recommending movies to watch on TCM, I’d never get any sleep. TCM, an American treasure, runs so much classic cinema of great value that I can’t keep up.

Today, though, as we’re about to depart for Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I’m pausing to knock out a brief entry urging your attention to a minor release that exemplifies some of the trends I try to track in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. The film is no masterpiece, but it’s better than most of the stuff pumped into our ‘plexes, and it can teach us a lot about continuity and change in the studio years.

A few hours in Autopia

In trying to map out the storytelling options developed in the 1940s, I ran into one trend that looked forward to today’s network narratives. I use that term to pick out films that build their stories around the interaction of several protagonists connected by social ties (love, friendship, work, kinship) or accident. Nashville, Pulp Fiction, and Magnolia are some vivid prototypes. The most common form of network narrative back then was based on the Grand Hotel idea, where a batch of very different characters interact in one place for a short stretch of time.

The form comes into its own in the 1930s, as I’ve indicated in a blog on Grand Hotel (1932). That novel/ play/ film popularized the concept, and MGM ran with it under the banner of the “all-star movie.” It was picked up in other 30s films of interest, like Skyscraper Souls (1932, often run on TCM) and International House (1933). But whereas Grand Hotel was a big A picture, most of its successors were B’s—perhaps because such a plot offered an efficient way to use contract players in a short-term project.

I suspect that’s what happened with One Crowded Night (1940), to play on TCM this Thursday, 22 June (7:30 EST). Dumped in the summer doldrums (back then, summer wasn’t a big moviegoing season), it garnered pretty unfavorable reviews. The big complaints were about the coincidences that get piled on. Wrote Bosley Crowther:

The long arm of coincidences does some powerful stretching for the convenience of film stories, but seldom has it been compelled so such laborious exercise as it is in RKO’s “One Crowded Night,” which opened yesterday at the Rialto. In a manner truly phenomenal, it drags together the assorted characters implicated in a multitude of small plots and dumps them, of all places, in a cheap tourist camp on the edge of the Mojave Desert.

It is pretty far-fetched. The Autopia Court, a speck on the flat, hot expanse, is run by a family whose main breadwinner, Jim, has gone to jail. He’s innocent, framed by Lefty and Mat—who show up by chance at Autopia. Meanwhile, a pregnant Ruth Matson gets off a cross-country bus to recover from heat stroke; she’s on her way to San Diego to meet her husband, a sailor.

Things get complicated fast. A trucker who comes through regularly wants to marry an Autopia waitress with a shady past. One of the thugs makes a play for the naïve waitress who’s fed up with this flea-bitten joint. But she’s worshipped by the gas jockey, who’s no match for the city hood.

The interweaving of lives is very dense. Guess who shows up, recently escaped from prison up north? When two detectives come through guarding an AWOL sailor, imagine who he turns out to be? And what if Doc Joseph, an amiable old fraud peddling a potion that cures everything, turns out to lend a helping hand?

No coincidence, no story. And especially in Grand Hotel plots, when people keep running into each other at just the right moment. Films aren’t about reality; one of the damn things is enough. Films are about giving us experiences, and this B picture seems to me quite satisfying—not least because it shows a relaxed but smooth pace almost completely unknown to modern cinema. It’s no small thing to tell so many stories in 66 minutes.

How work looks

Budget-challenged RKO makes a virtue of its limits. The film has a bleached, suffocating squalor. Dust and glare rise up. The outdoor set makes the motel complex look plausibly cheap. The diner is knotty-pine, and as dingy as you could ask. The countertop yields a solid thump when a plate of comfort food hits, and it’s easy to imagine it being gaumy to the touch. Greasy smoke sizzles up from a grill, blurring a poster advertising the good life and a cola that promises “Keep Cool.” And the shot of the disgruntled fry cook Annie owes nothing to pin-up standards.

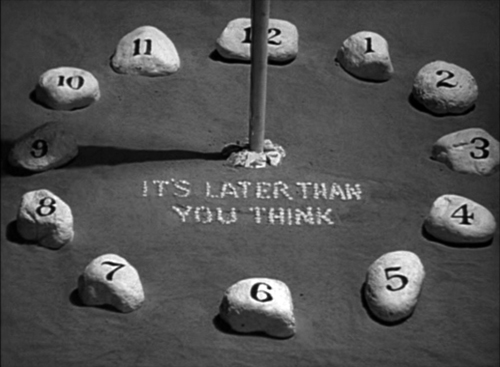

The film has that easy familiarity with the routines of working life celebrated by Otis Ferguson, who praised another film for its “reduction of the rambling facts of living and working to their most immediate denominator, to the shortest and finest line between the two points of a start and a finish.” We watch the Autopia staff briskly feed a busload of people during a ten-minute layover, fix up guest rooms, pour beers, wash dishes, scrub countertops, and pump gas—all the while an enigmatic sundial insists “It’s later than you think.”

With over twenty speaking parts, the film relies on swift, sharp characterizations. It’s lifted above the ordinary by the presence of the splendid Anne Revere, Hollywood’s embodiment of plain-speaking dignity, and the reliable Harry Shannon (aka father to Charles Foster Kane). Beloved blowhard J. M. Kerrigan plays the mountebank. Even a sweat-glistened Gale Storm (older boomers will remember her as TV’s My Little Margie) doesn’t do badly. The presence of so many character actors and bit players gives these people a worn solidity far removed from A-picture glamour. Everybody, young and old, looks fairly ill-used.

Irving Reis joined RKO after a brief but distinguished career in radio, where he created the much-lauded Columbia Workshop. One Crowded Night was his first screen credit at the studio. Renoir gets, deserved, credit for using deep-space compositions to suggest life lived in the background and on the edges of the shot’s main action. Reis, like many unheralded American directors, does the same thing. Network narratives encourage these juxtapositions, as story lines crisscross and characters react accordingly.

Reis went on to do more B pictures, as well as The Big Street (1942) and Hitler’s Children (1943). His later work includes Crack-Up (1946), All My Sons (1948), and Enchantment (1948; discussed hereabouts). He died young, in 1953. One Crowded Night shows him an efficient craftsman; Variety praised him for “development of the story’s many characters and juggling them through the many-sided yarn without confusion.”

The Grand Hotel formula would continue through the 1940s in Club Havana (1945), Breakfast in Hollywood (1946), and other low-end items. It would also yield a few A pictures, like Week-End at the Waldorf (1945, an explicit redo of Grand Hotel), Hotel Berlin (1945), and the hostage thriller Dial 1119 (1950). The format would go on to have a long life, right up to The Second-Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2015).

One Crowded Night, apart from its quiet virtues, served my book as a good example of just how pervasive certain models of storytelling became in the 1940s. Alongside the classic plot patterns of the single protagonist and the dual protagonist (often a romantic couple) other possibilities got explored. Some, like the Grand Hotel model, had been floated in the 30s and got revised in the 40s. Others took off on their own. All left a legacy—let’s call it a tradition—for the filmmakers who followed.

Thanks to TCM and its programmers for making this and thousands of other films available. But why not a version on Warner Archive DVDs? The Spanish DVD is pricy.

My quotations from Bosley Crowther come from “The Screen: At the Rialto,” The New York Times (27 August 1940), 17. The Daily Variety review appeared on 29 July, 1940, 3. Ferguson’s remark, on Joris Ivens’ New Earth, comes from “Guest Artist,” in The Film Criticism of Otis Ferguson, ed. Robert Wilson (Temple University Press, 1971), 126. For more on Ferguson, see my book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture.

Paul Guilfoyle and Anne Revere in One Crowded Night.

James Agee: Astonishing excellence: A guest post by Charles Maland

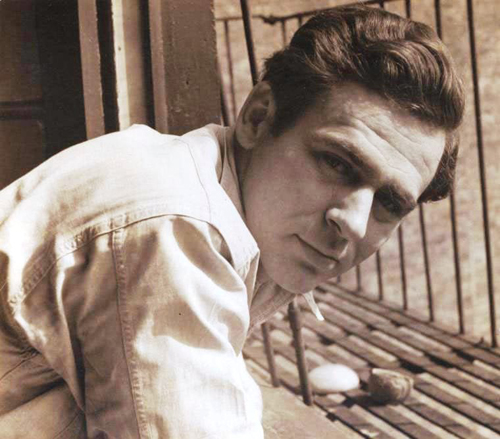

James Agee.

DB here: Charles Maland, a distinguished historian of American film, has just completed editing the definitive collection of James Agee’s film writings. It’s due to be published in July.

Agee changed American literature with Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and he changed film criticism with his reviews for The Nation and Time. After I wrote a 2014 blog entry on his work, I learned of Chuck’s project. Later I decided to turn the entry into a chapter of The Rhapsodes, a study of 1940s American film criticism. Naturally, I turned to Chuck for help. He was magnificently generous, steering me to sources and sharing new material he discovered. In particular, Agee’s unpublished manuscripts contain some powerful arguments and insights. Chuck’s historical introduction to the collection fills in many details of Agee’s relation to popular journalism, to the political and intellectual currents of his time, and to the Hollywood industry.

This book will be one of the most important film publications of 2017. As a warmup, we invited Chuck to write a guest entry on Agee and the process of editing the volume. We’re glad he responded, and we think you will be too.

In the summer of 1927, a precocious seventeen-year-old high school student wrote this to an older friend:

To me, the great thing about the movies is that it’s a brand new field. I don’t see how much more can be done with writing or with the stage. In fact, every kind of recognized “art” has been worked pretty nearly to the limit. Of course great things will undoubtedly be done in all of them, but, possibly excepting music, I don’t see how they can avoid being at least in part imitations. As for the movies, however, their possibilities are infinite—is, insofar as the possibilities of any art CAN be so.

Sixteen years later, British poet W.H. Auden wrote of the “astonishing excellence” of a movie column in The Nation, written by the same person, calling it “the most remarkable regular event in American journalism today.”

Auden was commenting on none other than James Agee (pronounced AY’-jee), a writer that New York Times reviewer A.O. Scott later called “the first great American movie critic.” Acknowledging that Agee didn’t “invent” movie criticism, Scott contends that he did show “what it could be as a form of journalism and a way of talking about the world.”

I concur with Scott about the importance of James Agee’s movie criticism, and for the past several years I’ve been preparing a complete edition of Agee’s movie reviews and criticism. Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, Manuscripts will appear this July from the University of Tennessee Press as Volume Five of The Collected Works of James Agee. Here I’d like to tell you a little more about who James Agee was and how he became a movie reviewer, what problems I encountered and discoveries I made in compiling the volume, and why Agee’s movie writings still deserve our attention.

Who was James Agee, and how did he become a movie reviewer?

James Agee (1909-1955) was born in Knoxville, Tennessee. In his relatively short career he was a feature writer for Fortune magazine; a book reviewer and movie reviewer for Time magazine; a movie columnist for The Nation; a co-screenwriter of, among others, The African Queen and The Night of the Hunter; and author of a volume of poetry, Permit Me Voyage (1934), an expansive social documentary book called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), and two novels, The Morning Watch (1951) and A Death in the Family (1957). The latter was published posthumously and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1958.

The novel also draws on Agee’s autobiography. When Agee was six, his father was killed in a car accident, and the novel explores just such a situation of a young boy, growing up in the Fort Sanders neighborhood of Knoxville, and the way he and his family cope with the father’s death. In real life, following his father’s tragic death, Agee’s mother sent her son to the St. Andrew’s School, a boarding school in Sewanee, Tennessee. After a year at Knoxville High School, Agee transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. There he finished high school and published his first movie review, on F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, which is included in the volume. He then completed his education as an English major at Harvard.

Agee loved movies from childhood. A Death in the Family includes a scene in which father and son walk from their neighborhood to go to the movies in downtown Knoxville, where they see a Charlie Chaplin short and a William S. Hart western. But he didn’t get the opportunity to review movies professionally until the 1940s. His first job as a feature writer for Henry Luce’s Fortune magazine paid the bills.

His book on Alabama sharecropper farmers in the Depression, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, started as an assignment from Fortune, but when Agee discovered that the subject far exceeded the boundaries of a feature article, he took a leave from Fortune to write the book. When it appeared in 1941, Americans were thinking about World War II and it sold only 600 copies, despite some positive reviews. The book’s reputation began to grow during the social turbulence of the 1960s, when it was reprinted and spoke to readers during that era in powerful ways. .

Following that disappointing commercial response, Agee returned to work for Time, Inc., now as a book reviewer for Time. (Volume 3 of the Collected Works, edited by Paul Ashdown, includes all of Agee’s published book reviews and non-film journalism.) While reviewing books, Agee kept alert to openings in the movie section, and he finally got his chance by reviewing The Big Street, starring Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda; the piece appeared in the September 7, 1942, issue of Time.

From then on, he remained on staff at Time as a movie reviewer until November 1948. His reviewing stint was interrupted after he wrote a powerful cover story for Time about the detonation of atomic bombs in Japan. For a few months in late 1945 and early 1946, Henry Luce put him on special assignment to write on social and political topics.

In December 1942, Agee also received an invitation from Peggy Matthews, arts editor of The Nation¸ a left-leaning journal of politics and the arts, to do a regular movie column for that audience. Agee accepted and his first contribution appeared late that month. Agee was writing about movies in two different places until his last Nation column on July 31, 1948. In between, by my best count, he reviewed 561 films in Time and 460 films in The Nation. Of that number Agee discussed 320 titles in both venues.

Agee stopped reviewing because he got the itch to write screenplays. Between 1948 and his death, he sometimes supported himself and his family as a screenwriter. His two most famous credits are on John Huston’s The African Queen (1951) and Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955). (Volume Four of the Collected Works, edited by Jeffrey Couchman, contains the script versions of these two films.) Partly to provide some income after he stopped reviewing but before his screenwriting career gained traction, Agee contracted with Life magazine (another Luce publication) to write extended essays on silent film comedy and John Huston. The resulting pieces, “Comedy’s Greatest Era” and “Undirectable Director,” are familiar to many readers. These pieces, along with some other individual Agee movie essays, like a review of Sunset Boulevard in Sight & Sound, also appear in the collection.

Problems and discoveries

The goal of this Agee collection is to provide access in one volume—for the first time—to all of Agee’s movie reviews, all of his other published articles and essays on movies, and a number of unpublished manuscripts I discovered in my research that cast light on Agee’s movie aesthetic and writing. Nearly all of Agee’s Nation reviews appeared in Agee on Film, Reviews and Essays (1958)—oddly, only his review of It’s a Wonderful Life was omitted—so compiling and editing those reviews was relatively uncomplicated.

The goal of this Agee collection is to provide access in one volume—for the first time—to all of Agee’s movie reviews, all of his other published articles and essays on movies, and a number of unpublished manuscripts I discovered in my research that cast light on Agee’s movie aesthetic and writing. Nearly all of Agee’s Nation reviews appeared in Agee on Film, Reviews and Essays (1958)—oddly, only his review of It’s a Wonderful Life was omitted—so compiling and editing those reviews was relatively uncomplicated.

Only a small selection of Agee’s Time reviews had appeared in Agee on Film. Because I began with what I thought was a full and accurate bibliography of all of Agee’s Time movie reviews, I thought that compiling them would be an uncomplicated task, too. I was wrong.

When he started reviewing for Time, and especially in his last months there, Agee was only one of several movie reviewers (although he was generally the primary reviewer). For the whole period he worked there, Time did not give bylines to writers. To verify what reviews Agee wrote, I enlisted the services of Bill Hooper, Time’s chief archivist. From him I learned that a copy-desk employee would handwrite in one master copy of each issue the name of the author of every article and review. These issues were then bound quarterly, and they eventually were deposited in the Time archives.

Mr. Hooper generously checked each volume against the bibliography I sent him and also responded to a number of questions that arose from the initial inquiry. The only period he was unable to verify was for the first three months of 1946: the bound volume from that period was missing. Fortunately, though, that was the time when Agee had taken an assignment as a special correspondent for social and political affairs.

As a result of these inquiries, I discovered that thirteen of the Time reviews and articles included in Agee on Film were in fact written by other journalists. It was even more suprising to discover that all thirteen of those pieces also appeared in the Library of America edition of Agee’s writings, Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005). Thus, of the 39 film reviews, essays, and profiles included in that volume, Mr. Hooper and I discovered that Agee had written only 26 of them. So I’m deeply indebted to Mr. Hooper. He enabled me to compile all of Agee’s film writings at Time in one place for the first time, at least as close as it is humanly possible to do.

As a result of these inquiries, I discovered that thirteen of the Time reviews and articles included in Agee on Film were in fact written by other journalists. It was even more suprising to discover that all thirteen of those pieces also appeared in the Library of America edition of Agee’s writings, Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005). Thus, of the 39 film reviews, essays, and profiles included in that volume, Mr. Hooper and I discovered that Agee had written only 26 of them. So I’m deeply indebted to Mr. Hooper. He enabled me to compile all of Agee’s film writings at Time in one place for the first time, at least as close as it is humanly possible to do.

The Agee papers, held principally in the special collections units at the University of Texas and the University of Tennessee, also contained a variety of fascinating information. I learned from financial records that Agee was well paid as a salaried employee of Time and that he was paid modestly at The Nation ($25 a column at first, later—it seems—by the word, which often amounted to less than $25). A few uncashed checks from The Nation in the archives suggest that Agee wasn’t much of a businessman. Other documents contained lists of film screenings that had been set up for Agee; they suggest that he saw a great many films, both in press screenings and regular theatre showings.

Perhaps most interesting for our purposes were a number of previously unpublished manuscripts. They included: 1) four-page typed “Movie Digest,” written in late 1935 or early 1936, containing thumbnail reviews (most with grades—A through F) of films, mostly from 1934 and 1935; 2) a scathing 1938 review of Bardèche and Brassilach’s The History of Motion Pictures that Partisan Review decided not to publish, probably because of how unrelentingly harsh it was; 3) a long letter that Agee wrote upon the request of Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish with suggestions about possible films to include in the Library of Congress film collection; and 4) some notes on movies and reviewing, probably from 1949, for a proposed Museum of Modern Art roundtable discussion of movies. All these manuscripts, including several essays or proposals for essays on René Clair and Sergei Eisenstein—both Agee favorites—are included in the collection.

Agee as movie critic

It’s hard in a short space to make generalizations about Agee’s aesthetic and why he should continue to interest us as a movie reviewer. Yet I would say he’s important for at least five reasons.

First, grounded in the history of film, he took films seriously and thought they were capable of being great, even though most movies failed to live up to his exacting standards. Beginning his childhood movie-going about the time that Chaplin was becoming an enormous star, Agee came to embrace a pantheon of filmmakers against which he measured other work. That pantheon included silent film comics like Chaplin and Keaton; filmmakers with great ambitions who had difficulty fitting into the system in which they worked, like D.W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, and Sergei Eisenstein; and European masters like Murnau, Pabst, Clair, Hitchcock, Dovzhenko, and Dreyer. He also praised a variety of contemporary American filmmakers, including those as diverse as William Wyler, Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, and John Huston.

First, grounded in the history of film, he took films seriously and thought they were capable of being great, even though most movies failed to live up to his exacting standards. Beginning his childhood movie-going about the time that Chaplin was becoming an enormous star, Agee came to embrace a pantheon of filmmakers against which he measured other work. That pantheon included silent film comics like Chaplin and Keaton; filmmakers with great ambitions who had difficulty fitting into the system in which they worked, like D.W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, and Sergei Eisenstein; and European masters like Murnau, Pabst, Clair, Hitchcock, Dovzhenko, and Dreyer. He also praised a variety of contemporary American filmmakers, including those as diverse as William Wyler, Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, and John Huston.

Second, his work is historically significant. He began writing just as the film industries of the United States and its Allies were trying to determine the role of movies during the world war that was raging. In his earliest reviews, Agee tended to celebrate the Allied documentaries (what he called “record” films) to the detriment of fiction movies. He was especially sensitive to a kind of poetic realism that he celebrated in Italian Neorealism (in his review of Shoeshine, for example) and in George Rouquier’s Farrebique.

Third, Agee was a magnificent and witty writer. He could write sustained, insightful essays, like his Time cover stories on Ingrid Bergman and on Laurence Olivier’s Henry V or his famous three-part defense of Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux. But he was also funny, especially when criticizing a film. Early in 1948 Agee got behind in his Nation reviews when he was hospitalized with appendicitis: to catch up he reviewed as many as 25 films in a single column, often in one sentence or two. Here are a few favorites:

On a mystery film starring Claude Rains, Agee wrote: “The Unsuspected is suspected too soon by the audience and too late by most of his fellow actors.” He disposed of an odd cinematic blend of whodunit and romance with this review: “Embraceable You is dispensable entertainment.” A John Wayne vehicle also took it on the chin: “Tycoon. Several tons of dynamite are set off in this movie; none of it under the right people.” He titled his February 14, 1948 column “Midwinter Clearance.” Perhaps my favorite was a Jeanne Crain-Dan Duryea vehicle: “You Were Meant for Me. That’s what you think.”

Fourth, Agee stands out because he had such catholic tastes. Although he was hard to please, he wrote enthusiastically and positively about a wide range of films. Agee praised European classics like Zero for Conduct, Ivan the Terrible (Part One), Day of Wrath, Children of Paradise, and Farrebique; British films like Henry V, Hamlet, Great Expectations, Odd Man Out, and Black Narcissus; a variety of American movies like The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Meet Me in St. Louis, The Big Sleep, The Best Years of Our Lives, Notorious, Monsieur Verdoux, and The Treasure of Sierra Madre; documentary films like Desert Victory, San Pietro, and They Were Expendable; Hollywood B films like Val Lewton’s Curse of the Cat People; the emerging Neorealist films; and dark urban dramas like Double Indemnity that later became known as film noir. Any critic who could write informatively and with enthusiasm about such a broad range of films had to possess a wide-ranging sensibility that welcomed the breadth of artistic possibilities presented by the movies of his era.

I should acknowledge here that some commentators have argued that Agee was not critical enough about really bad films and that he was too equivocal, trying to find something good to say about most of the films he reviewed. I’d respond to these claims in a couple of ways. First, it’s true that Agee was often equivocal in his reviews, but that equivocation often took the form of saying a film could have been more successful if it had done something better, but it didn’t. Another form of Agee equivocation was to say that an otherwise failed film did have some redeeming element (a song, a performance, a stylistically effective moment).

I think the fact that he would sometimes give bad films some positive gesture was partly a function of his love of the movies as an art form. I have to say I’m sympathetic to Agee here. I usually find something redeeming in almost every movie I see, and my wife regularly tells our friends that she’s the true critic in the family—they should ask her, not me, if they should see a film!

Second, I think there’s some difference between Agee’s Nation and Time reviews. He was under tighter editorial oversight at Time, and I think he was under more pressure to avoid completely lambasting a film than he was in his Nation columns. Getting a chance to read all of Agee’s Time and Nation reviews will offer readers an opportunity to think about how he wrote differently about movies for different audiences. The fact remains, however, that of the films and filmmakers he really admired, Agee showered praise on an unusually wide range of different kind of films.

Finally, as David Bordwell has observed, the publication of Agee on Film: Reviews and Essays in 1958 had a strong influence on the growth of film culture in the United States during the 1960s and after. As Bordwell put it,

There’s no knowing how many teenagers and twentysomethings read and reread that fat paperback with its blaring red cover. We wolfed it down without knowing most of the movies Agee discussed. We were held, I think, by the rolling lyricism of the sentences, the pawky humor, and the stylistic finish of certain pieces—the three-part essay on Monsieur Verdoux, the Life piece “Comedy’s Greatest Era,” the John Huston profile “Undirectable Director.” The adolescent fretfulness that put some critics off didn’t give us qualms; after all, we were unashamedly reading Hart Crane, Thomas Wolfe, and Salinger too. Some of us probably wished that we could some day write this way, and this well.

Agee on Film came along at a propitious time: European art film was beginning to flourish and a new generation of critics and reviewers—Sarris, Kauffman, Kael, Schickel, Simon, and later Ebert—engaged with this exciting new film culture. All, at one time or another, acknowledged Agee’s contributions. All, like Agee, published their reviews in book form.

For all these reasons, James Agee’s writings on the movies deserve our continued attention. I hope that by preparing a volume which contains all of Agee’s movie reviews and essays in Time and The Nation, all his other published writings on movies, and a number relevant but previously unpublished essays, I will help enable interested readers to get an accurate and fuller appreciation of Agee’s contributions to our evolving film culture.

Charles Maland is the author of Chaplin and American Culture (Princeton University Press, 1991) and the BFI classics volume on City Lights (2008). We thank him for his willingness to serve as a guest blogger.

Agee’s youthful encomium to film comes from Dwight Macdonald, “Agee & the Movies,” in Dwight Macdonald on Movies (Prentice-Hall, 1969), 3. Auden’s praise of his criticism is in “Agee on Film (Letter to the Editor),” Nation 159, no. 21 (18 November 1943): 628. A. O. Scott’s remarks come from Gerald Peary’s For the Love of the Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism (Bullfrog Films, 2009). The Bordwell quotation is in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2016), 2-3.

Agee’s name was frequently mispronounced. At the end of a 1948 Nation column, Agee apologized for mistakenly calling Amos Vogel “Alex” in a column, then went on to say, “I apologize to Mr. Vogel and to you; and sadly join company with an aunt of mine who used to refer to Sacco and Vanetsi, and with all those who call me Aggie, Ad’ji, Adjee’, Uhjee’, and Eigh’ ggeee’.”

Our next stop: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

P.S. 1 May 2019: For more on Agee, observed from many perspectives, including Chuck Maland’s, see the commentaries at the Criterion Collection.

James Agee, portrait by Helen Levitt.

FilmStruck and Criterion: Now Roku-ready

DB here:

Soon after Kristin posted the seventh installment in our Criterion series, there came the big news. FilmStruck and the Criterion Channel are now available for streaming via Roku. Some details are in this Variety story.

These streaming services had already been available on Apple TV, Chromecast, and other devices, but getting to Roku is a big boost. As of January, Variety says there are 13 million active Roku accounts. Roku capability is built into many smart TVs, and the set-top devices are reasonably low-priced. As a result, and as an early mover in the market, Roku has twice the penetration of its rivals.

Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I hope that subscribers will check out our monthly comments on films both classic and modern. Before or after our discussion, you can watch the films on the Criterion channel. We’ve regarded these short items as extensions of our blog, our research, and our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction. We try to make them clear and engaging.

If you subscribe to FilmStruck, you can log in and go straight to all our offerings. A synoptic page is here. Before Kristin’s entry on The Rules of the Game, we put up Jeff on the score of Foreign Correspondent, me on editing in Sanshiro Sugata, Kristin on landscape in two films by Abbas Kiarostami, Kristin on the child’s viewpoint in The Spirit of the Beehive, me on staging in L’Avventura, and Jeff on camera movement in Kieślowski’s Red. Whether or not you have FilmStruck, you can read blogs expanding on four of those entries here.

Coming up: Jeff on La Cérémonie and Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, Kristin on The Phantom Carriage and M, and me on Monsieur Verdoux, Brute Force, and Chungking Express.

And of course both FilmStruck and the Criterion channel offer a dizzying array of features, shorts, interviews, and bonus material. If you had told me just a few years ago that such a bounty would be so easily available, I’d have doubted it. Nothing beats seeing films on the big screen, but as a person who grew up with movies on TV (in small, degraded images and sound), I know that they retain some of their power in a lot of circumstances.

A monthly subscription equals the cost of three of Starbuck’s Cinnamon Dolce Lattes (Venti), whatever they are. Surely this is a great bargain. You can keep up with what’s coming along at Criterion’s website.

To those of you who have signed up and have followed our efforts: Thanks! Keep watching!