Archive for the 'Directors: Fleischer, Richard' Category

TRAPPED: Low-budget flash is good for you

Trapped (1949).

DB here:

Films of the 1940s sported many vivid titles, from Double Indemnity to The Best Years of Our Lives. But a lot of them really didn’t try too hard. We have Dangerous Lady, Shock!, Men on Her Mind, Bad Sister, Lust for Gold, and Criminal Lawyer. Even worse are Crack-Up, Manhandled, Temptation, Nightmare, Impact, Homicide, and even, the purest of all, Conflict.

Fortunately the lack of imagination didn’t always extend to story and style. In the Forties, even minor genre films could get flashy, displaying weird plot turns and wild visuals. Nowhere was this truer than in films centered on crime and mystery.

Granted, this material always encouraged some unorthodox techniques. (We can find examples going back to the 1910s.) Still, whatever you think “noir” was, it encouraged filmmakers to push even further. A 1930s B would have been unlikely to be as bodacious as a moment in Detour (1945), when a single forward tracking shot lets the lights lower and makes a coffee mug as big as a bucket.

For such reasons we should be grateful to the Film Noir Foundation, to the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and to Flicker Alley for bringing us Trapped (1949). The generic title had been used by four earlier films, and it could refer to several of the characters, but the results onscreen are far less banal. I hadn’t known the film, but if I had I might have wormed it into Reinventing Hollywood for the wrinkles it adds to the government-agent semidocumentary.

Crime high and low

Product placement for studio Hollywood’s favorite brand.

Trapped was produced by Brian Foy and distributed by Eagle-Lion, the same company that gave us the bizarre Repeat Performance (1947) and some of Anthony Mann’s best Forties items. According to the disc’s informative, pleasantly sensationalistic booklet, the project was hitching a ride on the success of Mann’s T-Men (1947). The Treasury Department approved of the project, and the film includes lots of fascinating shot-on-the-street scenes of LA. Although director Richard Fleischer doesn’t mention the film in his autobiography Just Tell Me When to Cry, he should have been proud of it. (He does mention Clay Pigeon, though, a film I talk about in another entry.)

A stern voice-over launches a quasi-documentary montage of the rise of counterfeiting after the war. Tris Stewart is serving time, but bills with his signature have resurfaced. Agreeing to act as a mole, he’s allowed to bust out of prison, but soon he eludes his federal handlers. He hooks up with his old girlfriend Meg and discovers that his precious plates are in the hands of an old adversary, Jack Sylvester. The bulk of the plot follows Tris’s effort to fund a last big job before fleeing to Mexico with Meg. In the course of it, he joins up with John Downey, a down-at-heel gambler.

The viewpoint shifts freely among the characters, so we always know more than any one of them. We know that the Feds have wired Meg’s apartment for sound. We learn that Downey is actually a government agent working to trap both Tris and Sylvester. And we see Tris eventually learn Downey’s identity decide to double-cross him.

Meg has a pivotal role in precipitating the climax. She’s naturally punished for hanging out with the wrong guy. I could apply my quatrain on Hollywood Stories:

The plot only works

If the men are all jerks;

But at the end of the game,

It’s the woman to blame.

Lloyd Bridges plays the sort of natty, grinning sociopath whom he would make memorable in The Sound of Fury (1951, aka Come and Get Me!). The dry John Hoyt is needed to carry the last stretch of the film, which he does with sangfroid, but Tris exits the plot a little sooner than we’d probably like. Eddie Muller suggests that Tris was intended to be in the climax but production contingencies put Sylvester into it.

To compensate, the wrapup becomes one of those dazzling Forties climaxes played out on an overwhelming location. Like the gasworks in This Gun for Hire (1942), the field of storage tanks in White Heat (1948), and the Fort Point Compound of The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950), here a vast trolley-car barn provides spectacular compositions and lighting effects.

Noir really did bring out the best in creative personnel. Guy Roe, a camera operator and assistant since the 1930s, had moved up to Director of Photography for Sirk (A Scandal in Paris, 1946), Mann (Railroaded!, 1947), another punchy Eagle-Lion effort, and Boetticher (Behind Locked Doors, 1948), so he was ready to give this effort flamboyant touches, some overt and some more subtle.

We tend to think of crane shots as aiming for surveying vistas outdoors. By the 1940s, many interiors were shot with smaller cranes or vertically mobile dollies that permitted alternation between tight high- and low-angle setups.

Roe would go on to shoot more films now considered strong noir entries: Armored Car Robbery (1950, another flat title) and The Sound of Fury. This last, as I suggest here, promotes the same tight high angles we find in Trapped, with perhaps more fine-grained results.

Fleischer didn’t have the blasting visual force of Mann, and Roe didn’t have the baroque imagination of Mann’s DP John Alton. Still, Trapped does deliver a handsome array of long-take deep-focus shots. These attest to the influence of Citizen Kane (1941) as a prototype for dynamic compositions, often exploiting ceilings on sets.

Such angles led directors to think more about using the vertical stretch of the screen, again aided by a camera pitched slightly high or low.

One turning point, Tris’s discovery of the Feds’ bug in Meg’s lamp, is designed to exploit a slightly tipped-down framing, with the splash of light accentuating the moment of revelation.

American crime films weren’t unique in their pictorial bravado. Watching Trapped drove me back to Noose, a 1948 British film by Edmund T. Gréville. A semi-comic tale of London gangsters, it abounds in florid depth compositions. (See below.) Just more proof that the 1940s saw a new exploration of bold narrative and stylistic initiatives in sound cinema around the world. And those weren’t confined to the big productions. Once new image schemas were available, artisans at all levels could make piquant uses of them.

The Flicker Alley release is nicely filled out with informative supplements contributed by Alan K. Rode, Eddie Muller, Donna Lethal, and Julie Kirgo. Mark Fleischer offers some touching reminiscences of his father’s life and creative ambitions. Thanks as well to Jeffrey Masino and Josh Fu of Flicker Alley. And we owe a debt to the collector who deposited a 35mm acetate print at Harvard, whence it comes to us.

For more on 1940s cinematography, see our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 and entries in the 1940s Hollywood categories here. Patrick Keating’s central chapters in The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood supply a lot of information about the growing use of cranes and maneuverable dollies for intimate dramatic scenes.

Noose (1948). A Brit noir ripe for Blu-ray release.

Little things mean a lot: Micro-stylistics

DB here:

In The Sound of Fury (aka Try and Get Me!, 1951), Howard Tyler has drifted into crime under the guidance of a breezy sociopath. They commit a string of holdups, culminating in a kidnapping. Howard’s partner bashes in the skull of their young captive. Wandering drunk and despairing, Howard ends up in the apartment of Hazel, a lonely manicurist. As Howard lolls on the sofa, she turns away to switch off the radio.

The next move is up to us.

If we’re alert, we can spot, on the end table in the corner of the frame, a newspaper with a headline that may be announcing the police investigation.

At first Hazel takes no notice. Will she? She does. She lifts the paper and is appalled.

Hazel turns toward Howard. Now we can see the entire headline as she reads aloud: Police are intensifying the search. She hasn’t made the connection between her guest and the boy’s disappearance.

Panicked, Howard lunges at her and crumples the newspaper.

Will this display of shattered nerves tip Hazel off?

As in the bomb-under-the-table model of suspense, at the start we know more than both characters know. She’s unaware of the kidnapping, and he’s unaware that the cops have found the victim’s car. In addition, the arc of suspense around the headline is quite small, though it leads on to something larger: Will Howard give himself away to the unsuspecting Hazel?

I’m impressed by the economy of presentation. Hitchcock might well have treated this moment in point-of-view shots, and a fairly protracted series of them. Or imagine how several filmmakers today would have handled this scene. There’d be a slow a track-in to the headline, then a circling camera movement that first concentrates on the woman picking up the paper, then racks focus to Howard on the sofa in the background.

Instead, director Cy Endfield makes very small changes of framing and staging matter a lot. The camera simply swivels, the actress simply comes to the foreground and pivots. The entire action, crucial as it will prove in what follows, consumes only twenty-five seconds.

Some stretches of a movie tend to be simply, barely functional: connective tissue or filler. Shots show cars driving up to places where the real action will take place, or characters striding down a corridor before going into a doorway. Other images want to engage us more deeply, but they do it through immensity. They try to awe us with majestic swoops over the sea or into the sky. (Recent example: Interstellar.) But other films engage us through detailing. They train us to notice niceties.

The Sound of Fury moment creates its detailing through visual space. What about time? And what about auditory factors? Our old friend, the telephone call, can furnish some examples.

Number, please

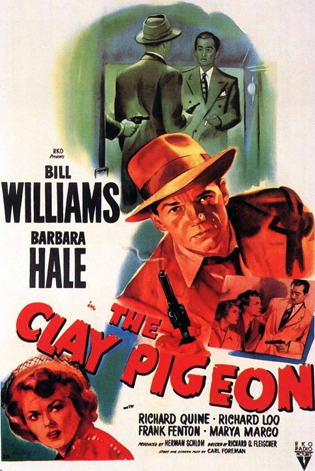

Clay Pigeon (1949).

Filmmakers must always decide how much of any action to show. Sometimes that allows the director, the cinematographer, and the editor to create fine-grained delays. These might not build up a lot of suspense but they can make us uneasy, and prepare us for a surprise later down the line.

As we mention in Film Art, and discuss in a related blog entry, a telephone scene forces the filmmakers to choose among clear-cut alternatives. Do we see both parties? Do we see only one and simply hear the other? (And is the voice of the one we don’t see futzed?) Do we see one and not hear the other at all? Most films don’t ask more than simple functionality, but even a B man-on-the-run feature like The Clay Pigeon (1949) shows what can be done with details of timing in setting up a phone call.

Jim Fletcher has war-related amnesia. He doesn’t know why he’s about to be court-martialed for treason. After escaping from the hospital, he learns that he is accused of betraying his best friend during their time in a Japanese POW camp. After convincing Martha Gregory, the friend’s widow, that he’s innocent, he searches for proof. The Clay Pigeon sticks mostly with Jim, but like most suspense films it slips in bits of unrestricted narration as well. Jim’s quest is tracked by mysterious men, and brief scenes give us glimpses of the forces pursuing him: agents of Naval Intelligence, and a gang of counterfeiters protecting the Japanese soldier who tortured Jim in the Philippines.

It’s the familiar structure of the double chase, dosed with minor mysteries. For example, when Jim gets a lead from a management firm, he leaves the office but the narration stays with the secretary who notifies her boss that Jim has been asking questions.

Cut to the executive’s office, where the camera reveals many stacks of wrapped bills on his meeting-room table. Something sinister is going on here, but what?

The decision to insert information addressed to us alone has more subtle consequences in two telephone scenes. Jim calls Ted Niles, another veteran of the POW camp. During these scenes, the filmmakers had the option of showing only Jim and never revealing Ted at the other end of the line. That tactic would have enhanced mystery, but it would have thrown suspicion on Ted. If he’s Jim’s friend and ally, why not show him?

So the filmmakers show Ted replying in his apartment. But later it will be revealed that Ted is working with the gang. The task is to introduce this important character in a way leaving open the possibility of his treachery. The solution the filmmakers hit upon is to show Ted just before he picks up the line. Here is the first instance, when Jim cold-calls him.

The camera shows Ted innocuously answering the phone and learning, to his surprise, that Jim has tracked him down.

At first Ted seems annoyed, but then he smiles and agrees to help.

The scene ends on Jim hanging up. If we wanted to plant more suspicion of Ted, we’d show him hanging up too and reacting to the call.

A later scene starts much the same way, with Ted coming in to answer a ringing phone and getting a message from Jim.

Both scenes show Ted answering the phone in a completely innocuous way. Yet the very fact of dwelling on his action of coming to the phone can be seen as planting uncertainty. In the second scene, for instance, where is he coming from? And in both scenes, Ted frowns at certain points. Perhaps he is pondering ways of helping Jim, but the expressions leave open the possibility that he is plotting against him. Ted’s duplicity is fully revealed only at the climax. (See image surmounting this section.)

In a mystery situation, a few seconds showing Ted alone gain a force they wouldn’t have in another genre. Some viewers will be surprised, some will say they knew it all along, but either way the detailing of a moment here and there has opened the possibility.

Party line

The Clay Pigeon telephone scenes show the speakers in alternation. The give-and-take of the conversation is presented by cutting back and forth. Another option is simply to show one speaker and let us hear the other without seeing him or her. As we’ve noticed, though, that would tend to make Ted a more mysterious figure.

Yet another possibility is the silent treatment: One speaker is shown talking, and we don’t hear the other at all. This option forces our attention wholly onto the reaction of the person we do see, and keeps us in the dark about the words and tone of voice of the person at the other end of the line. If the Clay Pigeon telephone calls presented Ted this way, that would be another tipoff.

Still, suppressing one half of the conversation can pay dividends when we already know the characters. At the climax of Humoresque (1947), detailing involves not a prop or a passing moment. Instead, a simple cut accentuates the shift from one sound space, that of violinist Paul Boray’s dressing room, to another, the luxurious living room of his lover Helen Wright. When he gets her call, he can’t understand why Helen isn’t at his big concert. But she is distraught because her own worries about keeping Paul’s love have been reinforced by Paul’s mother, who insists that she’s no good for him. And Helen is drinking again.

The scene’s tension is ratcheted up by first presenting only Paul’s angry questioning. We don’t hear Helen’s replies. When the dramatic momentum shifts to Helen’s desperate excuses for missing the concert, we concentrate on her meltdown more intently because now we don’t hear Paul’s replies. Her emotional response is magnified by the yearning climax of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Overture on the radio broadcast–another reason to suppress Paul’s voice.

The scene has been split between Paul’s end and Helen’s. By not seeing Helen’s reaction to his urgent questions, we wonder what is keeping her away. Like Paul, we’re unaware of her torment. But then we see and hear her, and our inability to know what he’s saying makes his pleas seem ineffectual. Whatever he’s saying doesn’t seem to matter. A simple speaker/listener cut raises the scene to a new pitch, which will build still further when we follow Helen out onto the terrace. One more detail, brutal: We don’t hear Paul’s voice, but we do hear the click when he hangs up.

One thing that links all these Little Things: What the filmmakers did not do. Cy Endfield did not indulge in camera arabesques or POV cutting. Richard Fleischer and his colleagues did not suggest Ted’s duplicity with music or a noirish shadow. Jean Negulesco and company didn’t yield to the temptation to crosscut furiously between a panicked Paul and an anguished Helen. These directors did something rare today. They presented the situation with stylistic simplicity. That way the big moments–the revelation of Ted’s treachery in the train, the frenzied mob in The Sound of Fury, the all-enveloping climax of Helen on the beach–become more vivid. Big things need little things to seem bigger.

Thanks to Jim Healy, who introduced me to The Sound of Fury and The Clay Pigeon.

For more on the bomb under the table, see the followup entry here.

Lest someone think I’m dumping on Nolan, let’s just note that he can, when he wants, summon up niceties. (By the way, thanks to readers for hustling to our Nolan vs. Nolan entry, but they should read the one on The Prestige and our Inception series here and here to get a fuller sense of our estimation of him. All of these are put into reader-friendly order in an insanely inexpensive ebook…..)

Several other blog entries consider detailing in performance: Henry Fonda’s hands, Bette Davis’s eyelids, and the facial expressions in The Social Network. I’m still mulling an entry on eyebrows, which are terribly underrated. For another Joan Crawford tour de force, there’s this.

Humoresque (1947).