Archive for the 'National cinemas: Greece' Category

Venice, virtually

Careless Crime (2020)

Every September over the last three years, we’ve immensely enjoyed visiting the Venice International Film Festival. There David has participated in the Biennale College Cinema discussions with stimulating colleagues.

This year, alas, the coronavirus kept us home. But the festival did make available a selection of fourteen films online. Each could be viewed for five days at the very fair price of $6 per film. (Here is the array of choices. A few are still available, so hurry.)

We took advantage of this opportunity and watched several titles. Here are our thoughts about three of them. (The first section is by David, the second by Kristin.) We hope that if you get a chance to see them on the big screen or at home you’ll investigate.

GOFAC is back! Actually, it never went away

The Art of Return (2020).

Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I tried to analyze the conventions governing a certain approach to moviemaking, the one that’s come to be called “art cinema.” My examples were films by Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman, the French New Wave, and many of their contemporaries.

In the years afterward, I revisited the ideas and asked: Are these conventions still in force? My conclusion in an updated version of the essay in Poetics of Cinema (2008) was: yes. From Fassbinder to Wong Kar-wai, from Distant Voice, Still Lives (1988) to Maborosi (1995) and beyond, we can find art-cinema principles of storytelling and style. In that book, the extended example was Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi, 1985), while other chapters traced how this tradition mobilized new options like forking-path narratives (e.g., Run Lola Run, 1998) and network narratives (e.g., Les Passagers, 1999). There’s a pirated pdf of the updated essay here.

Since then, it’s been fascinating to watch a younger generation of filmmakers take up this tradition. Every festival I visit furnishes examples, as you can see from our entries on this site. I had the same sense when watching Pedro Collantes’ The Art of Return (El Arte de Volver) and Christos Nikous’ Apples (Mila). Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema is still with us.

The Art of Return is centered on Noemi, who returns to Madrid after six years in New York. She has come home to audition for a role in a telenovela, and in the course of twenty-four hours she encounters several people from her past. The film consists of a series of duologues, as Noemi visits her dying grandfather, quarrels mildly with her sister, reconnects with her actor friend Carlos, and learns through another friend what became of Alberto, her ex.

What makes The Art of Return a prototypical art film is the way sheer chronology replaces a strongly causal plot. Apart from attending her audition, Noemi doesn’t have a strong goal; she drifts from one encounter to another. Most of these long scenes are devoted to discussions of her past, with hints about why she left Spain, as well as reactions of others to her personality. The task for a filmmaker using this episodic structure is to create patterns of revelation for us and for the character.

We need backstory about Noemi, and Collantes shrewdly avoids supplying flashbacks that would supply that. Instead, her past is refracted through the reactions of characters who are reconnecting with her, after much that has happened in their own lives. Gradually we assemble a fragmentary sense of what impelled her to go to New York. This revelation of the past is in effect the “under-plot” of the action.

Along with this pattern of revelation for us there are revelations for Noemi herself. She learns about her friend Ana’s floundering artistic ambitions, about her ex Alberto, about Carlos’ judgments of her. In an art film, the keenest revelation for the protagonist comes through an epiphany, a moment in which the character–sometimes mysteriously–gains self-awareness.

The crucial epiphany in The Art of Return, I think, occurs in a quiet scene in the park, among the trees that Noemi feels have been sculpted by a mystical force. By chance–again–she sees something that gives her the strength to make a decision. Yet in a typical art-cinema move, the outcome of that decision is withheld from us, suspended in a shot reminiscent of The 400 Blows (1959).

Collantes skillfully creates a firm pattern, with the opening scene symmetrically balanced by the final audition. In between, as in La Dolce Vita (1960) and Angela Schanelec’s Passing Summer (2000), the protagonist’s encounters provide a sampling and survey of life in the city, from the bohemian artists to the Romanian migrant community. A College selection, The Art of Return has already been acquired for theatrical distribution in Spain and other territories.

Apples (2020).

Because the art-cinema tradition minimizes a goal-directed plot, it often creates patterning through routine actions that are modified across the film. The changes in the routines reveal changes in a character or a situation. A vivid example is given in the Greek film Apples. After we’ve seen our protagonist regularly buy and eat apples (lots of ’em), he learns from a grocer that apples sharpen memory. He immediately switches to oranges. What psychology can justify this strange piece of behavior?

We understand it completely, because what has gone before has created a compelling context. The era is vaguely pre-digital, though there are some anachronisms. In the midst of an epidemic of amnesia, the poker-faced Aris is taken to a clinic for memory recovery. His doctors have created an experimental technique to give him a new life by reenacting routines of childhood, adolescence, and young manhood. As he rides a bike, fishes in a stream, visits a costume party, and goes to a dance club, he records his actions on Polaroids. These will fill an album and serve as replacement memories.

So Aris has a goal, albeit a diffuse one. We haven’t been told his overall program, so we are left to slowly figure out the rationale behind his dressing up as an astronaut or getting a lap dance. The film’s narration is almost as laconic as its protagonist, although a couple of scenes with his doctors show some sardonic humor. They eat his cooking and ignore the pathos of his situation while also, probably, misdiagnosing him.

Crucially, his retraining regimen intersects with that of another amnesiac, a woman further along in the program. Their relationship gives the film a romantic subplot, as well as its two most exuberant scenes: a dance to “Let’s Twist Again,” in which Siri seems to suddenly recover muscle memory, and a drive that spurs him to sing along with “Sealed with a Kiss.” (Hints about the under-plot give these scenes a dose of mystery and ambiguity–two more appeals of art-cinema storytelling.) All of this takes place before the apples-to-oranges shift, which in this context becomes as dramatic a twist as one would find in a thriller.

Shot and paced with extraordinary rigor in the 4:3 format, Apples is a perfect example of how GOFAC can create a distinct blend of curiosity, surprise, humor, and suspense. The film’s revelations in the final stretch are carried out as unemphatically as everything else, lending the character’s secrets an austere dignity. Apples has been eagerly acquired for many territories, and the director, who worked with Yorgos Lanthimos on Dogtooth, is preparing an English-language project. It will be, he hopes, “more accessible/mainstream.” Not entirely, I hope.

A carefully artful Iranian film

Careless Crime (2020).

Back in 2014, we were introduced to the strange world of Iranian director Shahram Mokri with his second feature, Fish and Cat. It’s a 139-minute single-take movie with a twisty plot in which the camera runs into separate groups of people in a rural lake area, with events starting to repeat from different points of view as the camera circles back on its route. We saw it in Vancouver, but it had premiered in the Orrizonti program at the Venice International Film Festival in 2013; it won a special prize “For Innovative Content.”

This year Mokri was back in the Horizonti thread with his third feature, Careless Crime. This time Mokri didn’t win a Festival prize, but the film received a FIPRESCI award for Best Screenplay.

Careless Crime is even trickier than Fish and Cat. It’s one of those puzzling films that requires the spectator to figure out the time frames of the different plot threads–and indeed how many times frames there are–and keep track of many characters. It’s a bit like Lazlo Nemes’ Sunset in the way it demands that the viewer constantly keep on the alert for the most fleeting or oblique clues as to what’s going on. (It’s interesting that Nemes and Mokri both have a penchant for lengthy tracking shots following a character closely from behind, as in the frame above.) Apples is another film that provides only a few subtle clues abut a major plot premise that eventually provides a twist at the end

There are two major plotlines. A group of four scruffy men plan to set fire to a crowded cinema as a political protest. Their actions recall an actual event that was the inspiration for the story. In 1978 a group of four arsonists set fire to the Cinema Rex in Abadan, causing the deaths of over 400 people because the exits were blocked.The event is credited with having launched the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

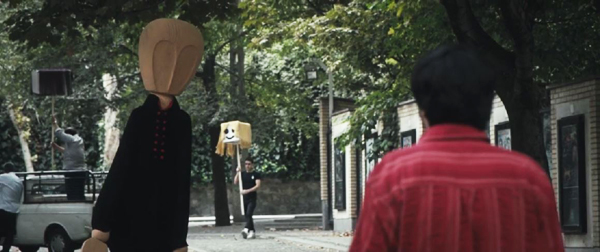

We follow the four men as they carry out inept preparations for their attack on the cinema. The group includes Faraj, a sad-sack who spends much of the early part of the film trying to get the nerve pills to which he is addicted. He tracks down a dealer who happens to be an employee at the local cinema museum and who is dressed in a large puppet costume, from the depths of which he digs out the precious bottle for Faraj.

The second plot involves a small, equally inept group of soldiers who have been sent to deal with an apparently unexploded missile deep in the countryside (see top). Contradictory information suggests that the missile landed some time ago and has been defused or that it landed the day before and needs urgent attention. Instead the men wander up into a local tourist area where two college girls are setting up an outdoor screening of the classic 1974 Iranian film, The Deer. This happens to be the film that had been screening at the Cinema Rex when the 1978 arson attack occurred. But the soldiers neglect their duty to solve the missile problem and spend their time waiting to see the young women’s film to find out if they are up to something nefarious. Thus two “careless crimes” may be involved. The the relationship between the two plotlines only becomes apparent late in the film.

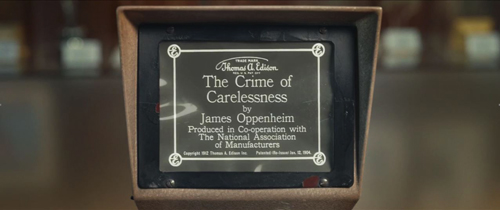

An obsession with cinema runs through both plots. The cinema targeted by the terrorists is apparently attached to the nearby museum and shows mostly art films, as is suggested by the posters for classic films that decorate the lobby. Young patrons and supporters of the cinema who hang around waiting for the show to start mention repeatedly that a friend has written an essay on The Deer, and we glimpse a poster for Kiarostami’s Close-Up. At one point Faraj, seeking the drug-dealer at the museum, sees a vintage film playing on an editing table.

It’s a 1912 Edison film, The Crime of Carelessness, in which poor safety conditions and a carelessly dropped cigarette led to a disastrous mill fire. At the end, a title in Farsi comes up, describing not the action of the silent film just shown but the 1978 Cinema Rex fire.

As all this suggests, there’s a good deal of magical realism in Careless Crime. At one point a single long take meanders around the open-air setting for the girls’ screening, picking up the same actions and dialogue repeated from different angles. During Faraj’s search for the drug-dealer, a museum employee guides him through the museum and its basement, again all in a single moving take. The seemingly endless basement is shot entirely against a black background, though at one point images of the two seemingly accompany them in the background.

Despite the grim subject matter, as in Fish and Cat, there is a good deal of self-conscious humor in Careless Crime. Little jokes are made about movies, and especially arty ones, as when a minor couple in the targeted cinema waits for the film to start. The woman looks at the screen (perhaps at a trailer?) and remarks, “I hate any film that has this laurel sign on it.” The reference is to one of the primary institutions of the international art cinema:

Is Mokri twitting the festival for not having chosen to show his films? As is now clear, his film’s repeat presence at Venice turned out to be an advantage in the long run. Although Careless Crime did not win a prize in the Horizonti competition, outside the official festival it received the FIPRESCI award for the best screenplay. Perhaps, when it finally becomes possible to return to the VIFF in person, we will see the next Mokri film and struggle not to be puzzled.

Thanks, as ever, to Alberto Barbera, Paolo Lughi, Savina Neirotti, Peter Cowie, and Michela Lazzarin for their assistance this year and in the past.

You can watch an extract of the Biennale press conference for Apples. The director discusses it in this Variety interview.

Our earlier entries on the Venice festival are here.

Apples (2020).

Venice 2019: Political dramas, allegorical and real-life

Waiting for the Barbarians (2019).

Kristin here:

The 76th Venice International Film Festival is over, but I have two films yet to blog about. This will be our final entry. Soon we’re both off to the other VIFF, the Vancouver International Film Festival, from which we will of course be blogging.

Waiting for the Barbarians

I was particularly looking forward to this film, since I admire Ciro Guerra’s two previous features, Embrace of the Serpent (2015) and Birds of Passage (2018). It was rather surprising that Guerra should have a new film premiering only a year after Birds of Passage, especially since both are in their own ways epics in relation to most other art films. The fact that it stars the great stage and screen actor Mark Rylance was another factor in its favor.

Oddly enough, the morning press screenings and evening red-carpet screening of Waiting for the Barbarians were relegated to the penultimate day of the festival, Friday, September 6. It was the last of the films in competition to be shown, with The Burnt Orange Heresy (in the festival’s Fuori Concorso thread) the closing film on Saturday. By that point, quite a few of the foreign-press members had departed for Toronto or elsewhere. The Friday afternoon press conference, despite including Johnny Depp on the panel (above), was SRO, but there was no immense queue to get and and very few standing at the sides or sitting on the central stairs, as usually happens when big stars are present.

Overall the film has received lukewarm reviews, with a few more praising pieces mixed in. Both David and I, however, found it riveting. It deals with the unnamed Magistrate (Rylance), who rules a fort community on the border of a desert landscape inhabited by nomadic tribes. The Magistrate controls the place with a loose rein, meting out mild punishments for what he perceives as minor infractions by the local population. He seems content, excavating for ancient wooden rods inscribed with undeciphered texts and apparently has a relationship with a sympathetic local prostitute. He seems friendly with the people under his care and has taken the trouble to learn their language.

The countries which this border area separate are never identified and are clearly fictional places serving to portray the horrors of colonial domination by western nations. Clearly the white officials and soldiers in the film are not intended to be British. The flags on display bear no resemblance to the Union Jack and the costumes are not British. The local nomads speak Mongolian, and the main female character, referred to only as “the Girl,” is played by Gana Bayarsaiknan, a Mongolian performer.

The conflict is set moving by the arrival of Colonel Joll, an ominous figure in black, sporting bizarre dark glasses with frames of twisted wire (in the background of the frame at the top). His suggestion that he will use “pressure” to force the locals to confess their crimes turns out to be a considerable understatement. Joll ventures a little way into the the territory of those he calls “the barbarians.” He claims to turn up evidence that the local people are plotting to attack the colonial forces along the border. He has discovered this evidence though torture.

Much more description would provide too many spoilers. In general, the Magistrate tries to reason Joll and his confederates out of their plans. He also frees prisoners and nurses the native girl, who has also been tortured, back to a semblance of health. Eventually he finds himself driven to rebellion.

The film, with exteriors shot in Morocco, creates a vivid sense of a fortress community isolated from the world, and the cinematography as the Magistrate leads a small group to try and return the Girl to her people is austerely beautiful.

So far all the release dates for Waiting for the Barbarians are for festivals, including the London Film Festival. Whether it will be released in the US, as Guerra’s two previous films were, is unknown. I would suggest giving it a chance, despite some lackluster reviews. It’s another film that would lose much of its effect when streamed on a small screen.

Adults in the Room

Each year a small number of celebrities receive special awards, essentially salutes to long and fruitful careers. This year the main honors went to Pedro Almodóvar, Julie Andrews, and Costa-Gavras. We didn’t catch the awards ceremonies themselves, and the Amodóvar and Andrews ceremonies were followed by classic films of their past (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown and Victor Victoria respectively). Costa-Gavras’ career started as an assistant director to René Clair, René Clément, Henri Verneuil, Jacques Demy, Marcel Ophüls, Jean Giono, and Jean Becker before beginning to direct on his own. Apart from his numerous features, perhaps most notably Z (1969), he has been president of the Cinémathèque Française since 2007.

Now, at age 86, he brought with him a new feature, Adults in the Room, a dramatization of the tensions and strategies of the politicians and diplomats struggling to find a solution to the Greek financial crisis.

As in most such films, the actors have been chosen for their resemblance to the historical figures. In the upper of the two images below, for example, Josiane Pinson plays Christine Lagarde, head of the IMF, and Daan Schuurmans is Jeroen Dijsselbloemm, president of the Eurogroup.

The film begins with the unlikely election of a leftist government in Greece (the Coalition of the Radical Left, or Syriza) in January of 2015. The film sticks largely to the point of view of Yanis Varaufakis, the fiercely dogged Finance Minister. His memoirs of the struggle to refinance Greece’s overwhelming debt and to keep Greece from being expelled from the European Union were the basis for the script by Costa-Gavras.

Remarkably, Costa-Gavras follows the events through an almost unbroken series of conversation scenes. These center on clashes between Varaufakis and Greece’s Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, and on stormy meetings involving representatives of the Eurogroup and the infamous “Troika” (the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund). The Troika faction, which had bailed out the Greeks and insisted on disastrous austerity measures, absolutely refuses Greece’s demand that the loans stop and that the debt be devalued to a viable level.

This does not begin to convey the complexity of the Greek crisis, but Costa-Gavras manages to create suspense, whether or not we can actually follow exactly what is going on. There are moments when Varaufakis’ negotiation strategies are withheld from us, and we are as puzzled as the officials watching them from across the room, as in this glance-POV cut:

These meetings are linked primarily by shots establishing the various cities in which these complex and fruitless meetings take place. Often superimposed titles reveal the locations, as when the Greek Prime Minister arrives in Brussels for one such meeting (see bottom).

By the end we are not left with a thorough grasp of the intricacies of these events, which would hardly be possible for a crisis that started around 2009 and is still going on. Still, we gain a somewhat better understanding than we are likely to have on the basis of news stories stretched sporadically over over so many years. We are also left indignant at the determination of the Troika to persist in the very policies that drove Greece deeper and deeper into debt. Some have found the film tedious in its intense focus on meetings and strategies. Others I talked to after the press screenings found it fascinating. Certainly the film and its source book have chosen the brief period of the crisis (about six months) that shows most clearly and dramatically what Greece faced from the rest of the EU and why its crisis still has not ended.

For one final time this year, thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Adults in the Room (2019).