Archive for March 2015

Pixels into print: The unexpected virtues of long-winded blogging

Penance (2013).

DB here:

Remember Web 1.0, when blogs were really logs? You know, diary-like accounts of events befalling the writer? The sense that every instant of one’s life needs preserving and broadcasting got absorbed into Facebook and Twitter and Instagram, I suppose. Today blogs are more likely to feature essayistic thinking. People slow-cook their blogs more, it seems to me, and they write in a reflective mode. Since our blog has always been, um, expansive in such ways, I welcome the Ruminative Turn.

Like most academics, we write long for a reason. You need more words to dig into a question. That’s why books exist. But mid-range is good too. The blog format suits specualtive, exploratory work and informal prose that wouldn’t show up in a journal. In this para-academic register, the aim is to spread ideas and information around. A reviewer of the book I mention below puts it well: “democratic, attainable erudition.”

Because we write long, and maybe because we’re a bit chatty, a few of our entries have become published, suitably spruced up, as “real” articles for diverse audiences. Some overseas journals, both print and online, have published translations of pieces available here. Thanks to the good offices of the University of Chicago Press, a gaggle of our entries became a book, Minding Movies. Lately, three of our blogs have wriggled their way into paper—two as DVD liner notes, and a third in an imposing rectangular solid that is sort of a mega-book. All are aimed beyond the academy.

Doing Penance

Two summers ago our friend Gabrielle Claes tipped me to a visit by Kurosawa Kiyoshi, accompanying a screening of his Penance (Shokuzai) at the Brussels arthouse Cinéma Vendôme. Of course we went, and we had a good time with the film and the Q & A that followed. I duly wrote it up, did a bit of quick analysis, and offered it to the world online.

When the Doppelgänger branch of Music Box Films decided they wanted to distribute Penance on DVD, they asked for the essay. The it’s come out in a good edition (alongside Eddie the Sleepwalking Cannibal, worth a look, and other genre fare). My essay is preceded by one by Tom Mes of Midnight Eye, who discusses the film’s relation to its source novel and pinpoints its exploration of “the gray area between the mundane and the ghastly.” there’s also an informative interview with Kurosawa.

As a five-part TV series, Penance fits its plot to the installments pretty rigorously. A little girl is assaulted and murdered, and only her four playmates have seen the killer. Taking advantage of the serial structure, Kurosawa begins each episode by revisiting the original crime, picking details relevant to what we’ll see but expanding the sequence a bit by tracing each girl’s efforts to notify the community. It’s a sophisticated version of the “Previously on [name of series]” recaps we commonly get in TV serials.

After revisiting the killing and showing the aftermath as it affects each girl, every installment shows the children gathering for a grim birthday party. On that occasion Emiri’s mother Asako demands that the girls either find the killer or do penance for their lack of vigilance.

After this juncture, each of the first four installments attaches the narration to one girl’s viewpoint fifteen years later. The episodes trace the awful effects of the crime on the girls’ personalities and their adult lives. Each one gets involved with an unstable man, with catastrophic consequences. In each episode, Asako reappears at a critical moment to demand penance or to absolve the woman. The fifth episode centers on Asako herself: her immediate reaction to her daughter’s death, her search for the killer, and her realization that the crime has roots in her own past.

I was happy to get a chance to see Penance again, because it’s continually engrossing and quite moving. It also exemplifies the sort of clean, classical genre filmmaking that doesn’t get done in America very much. After watching all the GPS views and whooshes down to street level and nonstop bludgeoning supplied by Run All Night (still, an okay movie), it’s a pleasure to turn to a film that builds its tension through a fixed camera, calm clarity, and performances suggesting suppressed menace rather than explosive confrontations–though there are a few of those too.

Penance would be something for young filmmakers to study. It shows how locations can be used elegantly and economically, and how the inability to get extreme long shots in cramped quarters can actually be an advantage. Classrooms, offices, and gymnasiums are used with a sober restraint, each one given defining geometry and color scheme. A crucial confession takes place in a police station being renovated, and Kurosawa lets the scene unfold in a way that continually reveals surprising bits of space, such as a cop standing somewhat ominously at a distance. He’s unafraid of holding long shots because the shot is propelled by the drama, not the cutting pace. Here’s another example that illustrates the Monroe Stahr rules of storytelling: not a car chase or gun battle, but a quietly puzzling situation that evokes curiosity and suspense.

Asako has gone to a drawer and withdrawn a ring. We’ve not seen it before and have no idea what it signifies.

She crosses the room, as if to do something with it. Before we find out, cut to her husband in the hallway. This cut initiates a take lasting over three minutes.

When he reaches the doorway he catches her hurling it angrily into the wastebasket. So now we know he knows…but what?

Reminding her that she’s treasured this since college, he fetches it out for her and quietly leaves.

As she starts to explain, she follows him into the corridor. The camera pans right to reframe their new confrontation.

There she reveals her secret, slowly. As she crumples to the floor, Kurosawa permits himself a camera bobble–a rarity in a film that almost entirely avoids handheld camerawork. The husband at first consoles her…

…but then she confesses her secret. He pulls away from her.

She tries to embrace him, looking for solace, but he shuts her out and withdraws.

She’s left to fall to the floor crying in shame, in that classic attitude of distraught Japenese women.

The highest pitch of the drama–Asako’s revelations–has been given a close view, but the action has led up to it and away from it through character blocking, not cutting. The situation unrolls and builds tension completely through dialogue, body language, and facial reaction. But it could hardly be considered theatrical, because the camera has judiciously strengthened certain parts, concealed others, and obliged us to shift character perspective (Asako-husband-Asako) through slight changes of position. And playing so much of the scene in distant and dorsal shots harks back, inevitably, to Mizoguchi.

As I mentioned in the early entry and the liner notes, Kurosawa always knows where to put the camera–no small accomplishment these days–and there’s as much power in this apparently simple scene as in any of the grandiose Steadicam movements in more inflated films. Trust the audience to sense the undercurrents, and they will follow you if you have mastered calm, precise cinematic storytelling.

Grand hotellerie

The Doppelgänger gang released Penance on DVD last November. I’m only a little less late in mentioning the arrival of Matt Zoller Seitz’s newest addition to The Wes Anderson Collection: The Grand Budapest Hotel. The decision to base a big, luscious book on a single Anderson film gives this ambitious picture even deeper treatment than we saw in the Collection’s individual chapters. From Seitz’s rich opening appreciation to the amiable list of contributors (The Society of Crossed Pens), the book is a serious divertissement, a wonder-cabinet of images, ideas, and semi-childish fun.

It’s partly a making-of book. We get production stills, script pages, set designs, storyboards, animatics, special-effects secrets, costume designs, and the now-celebrated photochrom images. Seitz has larded his captions with shrewd critical points about lenses, compositions, lighting, and staging—not the normal gee-whiz commentary of an “authorized” making-of. Anderson’s enjoyment of practical effects, his judicious use of digital tools, and his most complex voice-over narration yet come through vividly.

Seitz is especially interested in the history and artistic models behind the movie. His interviews are crowded with information about Anderson’s inspirations, which seem endless. Of course there is Stefan Zweig, who is given several pages of intense discussion. We also learn of Anderson’s interest in the exiled directors like Lubitsch and Wilder, who gave us both a Europeanized Hollywood and a Hollywoodized Europe. There are homages to The Red Shoes and Colonel Blimp and Letter from an Unknown Woman. Anderson was equally committed to a broader historical context, passing his story through different eras—the bell-jar atmosphere before the Great War, the premonitions of World War II (itself never shown), and the postwar emergence of Communism, seen in the revamped and decaying Hotel in the 1960s. Seitz has even spotted borrowings from James Bond movies. As skillful an interviewer as he is graceful an essayist, Seitz induces Anderson to reveal the density of this sweet, sinister movie—the cinematic equivalent of Chandler’s line about a tarantula on a slice of angelfood cake.

There are as well interviews with Ralph Fiennes talking of the “farce spectrum,” costume designer Milen Canonero ordering up a Prada leather coat for Willem Dafoe, the very great composer Alexandre Desplat explaining his compositional procedures, production designer (and Milwaukee native) Adam Stockhausen discussing the magnificent settings, and DP Robert Yeoman talking about shooting on 35mm.

There are as well interviews with Ralph Fiennes talking of the “farce spectrum,” costume designer Milen Canonero ordering up a Prada leather coat for Willem Dafoe, the very great composer Alexandre Desplat explaining his compositional procedures, production designer (and Milwaukee native) Adam Stockhausen discussing the magnificent settings, and DP Robert Yeoman talking about shooting on 35mm.

Anderson’s fussbudget aesthetic meets its match in a book crammed with fastidious minutiae. Whimsy, as Lewis Carroll and G. K. Chesterton understood, escapes coyness only when it’s pursued rigorously. Seitz reviews the careers of the major players in postage-stamp pasteups. When Anderson is revealed as a connoisseur of frame stories, flashbacks, and other fancy techniques we favor on this site, Seitz provides a four-page spread of pick hits of voice-over. Max Dalton, the illustrator, gets the message. With their modestly lowered eyes and sidelong grins, his neo-New Yorker figures swarm these pages but assemble, obediently rank and file, in the end papers.

Most surprising of all for a production dossier, in-depth criticism is not only allowed in the tent but given its turn in the spotlight. Christopher Laverty analyzes the costumes with a precision seldom seen in academic writing, while Olivia Collette contributes an enlightening study of Desplat’s score. Steven Boone examines the art direction, with a special sensitivity to how set designs are fitted to anamorphic optics. Ali Arikan brings his characteristic lucidity to a study of Zweig’s Vienna and the traces it leaves on his fiction and Anderson’s film. The essays show that analytical film books, like volumes of academic art history, can be merit high production values.

My contribution, a revamping and nuancing of an earlier blog entry, looks at how Anderson adjusts his planimetric staging and shooting to different aspect ratios. For me, this assignment was the big time. No academic book, my usual publishing platform, could have illustrate my ideas so splendidly. I’m proud to be among fine company, and I like the fact that people are reading and buying the thing.

Of course very few film books have the built-in audience of a Wes Anderson project. As I wrote last summer, he brings his brand with him. But that isn’t, I think, a bad thing when the results are as lively and lovely as The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Last year I had to go to Hong Kong the weekend the film opened. I dashed to it during my first day in town, then squeezed in two more screenings during the festival. Now, after a year and many more viewings, it hasn’t cracked yet. At the moment I think of it in relation to the “hotel” books and movies of the 1920s and 1930s. I think of its predecessors, such as Arnold Bennett’s 1902 novel The Grand Babylon Hotel. (Did Anderson read it? I don’t find a mention here.) I remember those star-filled ensemble comedies of the 1960s like The Pink Panther and The Great Race, twitching with celebrity walk-ons and the cartoonish effects Anderson relishes. In short, I think about film history, and it pleases me when a film and its book trace out, in dazzling detail, an exceptional movie’s debts to tradition. Keep your Birdman and Gone Girl and Jersey Sniper (or is it American Boys?): This is the 2014 American film that will be remembered for decades.

Hello again, my language

Last year’s other big film for the future is, no doubt now, Adieu au Langage, just coming out on Blu-ray as Goodbye to Language from Kino Lorber. I’ve said my say about this item twice (here and here) so about all I have to add is that after several more viewings, I’m still convinced of its excellence. Kino Lorber gives us two versions, the 3D one and the “merged” 2D one. The 2D one is still one hell of a film, but of course in 3D it’s spectacular.

The disc includes an essay developed beyond my blog entries. It says some new things, but it’s inevitably incomplete. Godard’s films so teem with ideas (both intellectual and cinematic) that there’s almost always more to notice. “One can put everything in a film,” he remarked back in the 1960s. “One must put everything in a film.” He sort of does, especially here.

Both versions belong on every cinephile’s shelf. If I didn’t already have a 3D TV (purchased so I could watch Dial M for Murder and Gravity properly, and even freeze the frame), I’d get one so I could see Farewell to Language whenever I wanted. Consider your options. 3D TV is now dead enough to be cool.

Thanks to Austin Vitt of Music Box films for picking up Penance, and Richard Lorber and Robert Sweeney for recruiting me for the Godard disc. I’m indebted to Matt Zoller Seitz for bringing me on board the Anderson project, and to Caitlin Robinson of Twentieth Century Fox for loaning me a print of The Grand Budapest Hotel so that I could study its aspect ratios in their natural habitat.

Midnight Eye features Kohei Usuda’s very detailed review of Kurosawa’s latest project, an entry in the “idol movie” genre. You can find MZS’s video introducing the Grand Budapest book here.

Goodbye to Language.

1932: MGM invents the future (Part 2)

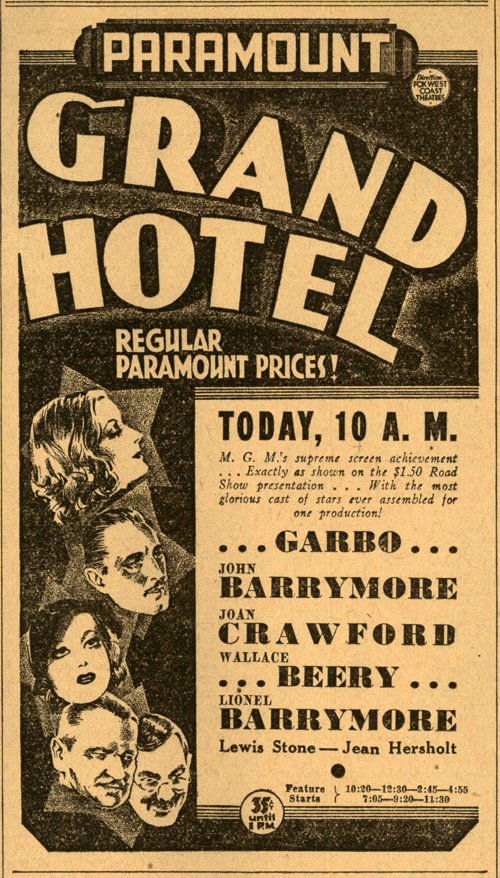

Courtesy John McElwee and his gorgeous, informative site Greenbriar Picture Shows.

DB here:

The inner monologue, as a report of a character’s immediate thoughts, seems to have been rare in 1930s films; it became more prominent in the 1940s. But the second big MGM narrative innovation of 1932 was almost instantly influential, redone and nearly done to death in the decades that followed. Even before the film was released, the idea of a “Grand Hotel plot” had gripped both the public and professional storytellers. And it never went away.

In the Strange Interlude entry, I mentioned that what’s usually of interest to us when we try to track the history of film forms is not the first time something is done but the moment when it becomes recognized as an active option. It stands forth as a strategy that can be copied, standardized, and revised. The Grand Hotel idea itself wasn’t utterly new, but the novel, play, and film of that title crystallized it as a distinct choice on the filmmaking menu.

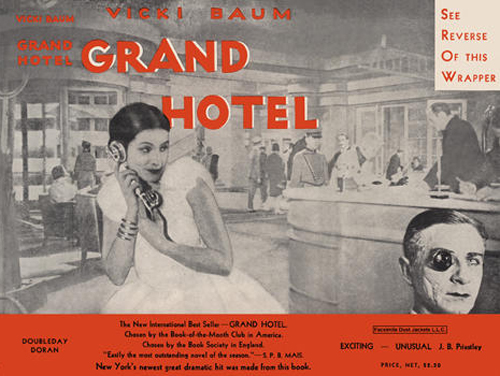

The book: Only approximations

Vicki Baum, an emerging German novelist, launched Grand Hotel as a magazine serial. It was published in book form in 1929 as Menschen im Hotel and became a huge seller. The following year saw Baum’s international breakthrough. In January a stage version opened in Berlin. It migrated to Broadway in November and enjoyed huge success. Meanwhile, a British publisher brought out an English translation. In February of 1931, Doubleday published an American edition. That month Baum arrived in Hollywood to work on the screenplay for what she called her “star-studded wedding cake.”

The central story remains constant in all the media versions. Three men converge in Berlin’s Grand Hotel, each with his own aims. Baron von Gaigern is a penniless aristocrat who has taken to theft. The provincial bookeeper Kringelein has been diagnosed with a fatal disease, so he has vowed to enjoy the good life before he dies. He demands a costly room and plans to wine, dine, and gamble his savings away. The business mogul Preysing is there to meet with potential partners in a big business deal. Preysing, it turns out, is the owner of the company employing Kringelein.

The men’s plans pull two women into their orbit. There is the glamorous but fading dancer Grusinskaya. She meets the Baron when he slips into her room to steal her pearls; during that night of sexytime they fall in love. Then there is the stenographer Flaemmchen, who takes a liking to the Baron but who is dominated by Preysing. He has hired her to record his deal-making, and he soon invites her to be his mistress. Add in secondary characters like the porter Senf, who at the start is waiting for news of his wife’s delivery of their baby, and Dr. Otternschlag, a disfigured war veteran who drifts around the lobby mournfully observing life.

The men’s plans pull two women into their orbit. There is the glamorous but fading dancer Grusinskaya. She meets the Baron when he slips into her room to steal her pearls; during that night of sexytime they fall in love. Then there is the stenographer Flaemmchen, who takes a liking to the Baron but who is dominated by Preysing. He has hired her to record his deal-making, and he soon invites her to be his mistress. Add in secondary characters like the porter Senf, who at the start is waiting for news of his wife’s delivery of their baby, and Dr. Otternschlag, a disfigured war veteran who drifts around the lobby mournfully observing life.

The novel’s action consumes three days and nights, with an epilogue on the morning of the fourth day. Each major character undergoes a crisis triggered by meeting others in the hotel. Preysing catches the Baron in his apartment, bent on robbery. In beating the Baron to death, Preysing ruins his life; he is arrested and his family leaves him. Flaemmchen, about to go off with Preysing, attaches herself to Kringelein and vows to help him recover his health. Grusinskaya, who has left Berlin for her tour date in Prague, calls the Baron’s room in vain, unaware that she will never see him again.

The book offers several attitudes toward the interwoven destinies. There is that of the grim Dr. Otternschlag, who sees in the lobby’s revolving door a ceaseless cycle of mundane suffering. “Always the same. Nothing happens. . . . And so it goes on. In—out, in—out.”

The bellboy looks at the same door and sees endless variety: “Marvelous the life you see in a big hotel like this. . . . Always something going on. One man goes to prison, another gets killed. . . .Such is Life!”

The omniscient narration provides another attitude, seeing in the door an image of life’s ephemeral, fragmentary quality.

The revolving door twirls around and what passes between arrival and departure is nothing complete in itself. Perhaps there is no such thing as a completed destiny in the world, but only approximations, beginnings that come to no conclusion or conclusions that have no beginnings.

All three musings represent, we might say, alternative ways of reading the novel: as an eternal return, a varied pageant of human drama, or scattered glimpses of incomplete lives.

Play and film: Call waiting

National Theatre production, New York 1930.

The novel spreads the action to the theatre, a casino, and an airplane flight, but the stage version confines itself wholly to the hotel. The play begins with a coup de théâtre for which Baum claimed the credit. Preysing, Kringelein, the Baron, Flaemmchen, and Grusinskaya’s maid Suzanne are introduced in a line of telephone booths, each making a quick phone call. The light in each booth flashes on and off as each one speaks. The pace builds until each speaker is “intercut” rapidly with another. Baum claimed that this pulsating sequence drove the opening-night audience to a frenzy of applause. Snazzy as it is, the prologue serves as crisp exposition, literally spotlighting nearly every major character, with Suzanne acting as a proxy for the dancer Grusinskaya. Then the revolving stage whisks us to a broad view of the lobby teeming with guests and staff.

The novel can proceed in a fragmentary way, shifting from one character to another, but the play contrives a more fluid rhythm of encounters. At the start, several characters assemble at the front desk, and after a “cutaway” to Grusinskaya’s room, we’re back in the lobby with Flaemmchen, the Baron, and Kringelein chatting while Preysing and his colleagues head off to their conference. Later all the major characters except Grusinskaya, who’s often marked as separate from the others, meet in the hotel bar and grill. At the conclusion, as characters depart, overlapping encounters carry Flaemmchen out the door with Kringelein, and Grusinskaya leaves for Prague wondering why the Baron has failed to meet her. The spatial concentration of the play squeezes the characters’ trajectories together more tightly than the novel does.

The film does much the same thing. When head of production Irving Thalberg bought the rights to Baum’s novel, he had to buy the stage rights as well, and so MGM funded the Broadway production. It garnered over a million dollars in its first year.

Claus Tieber points out that having seen the play, Thalberg insisted that the bits that pleased the Broadway audience had to stay in the film. No wonder that the film sticks close to the stage version. Although sequences are added, they seem in the spirit of the play’s swift pace. An American critic had described the book’s rapid changes of scene as like a film: “interlocking adventures, a little too easily linked perhaps, flit from screen to screen [shot to shot?].” Baum agreed:

I realized what had made my Grand Hotel, the novel and the play, a world success: it was probably the first of its kind to be written in a sort of moving picture technique. By now [1964] that’s the oldest of old hats, but in those days the kaleidoscopic effects, brief ever-changing scenes, flashes, staccato dialogue, were new, surprising, and exciting…on the stage. On the screen, I felt, this technique was the usual old stale shopworn thing.

In a crucial expansion of both book and stage show, the film emphasizes the telephone switchboard, marking the hotel as the crossing point of many destinies. After Preysing has beaten the Baron to death with a phone receiver, the switchboard is ominously stilled at the climax.

The prologue shows other protagonists making calls, but Grusinskaya, because of her isolation from the others, works the phone in the bulk of the film. Her final call for the Baron goes unanswered, heard only by his dog.

The play had enhanced the women’s roles, and the film goes farther by casting two top stars, Greta Garbo as Grusinskaya and Joan Crawford as Flaemmchen. With three strong male leads—Wallace Beery as Preysing, Lionel Barrymore as Kringelein, and John Barrymore as the Baron—the film became an ensemble drama that gave more or less equal weight to five characters. Accordingly it became known as the first “all-star picture.” On its tenth anniversary Variety proclaimed that it “disproved the contention that no picture could support a huge all-star cast.”

Even putting the cast aside, Grand Hotel crystallized a narrative option that had been emerging, more or less explicitly in the years before.

Networks and cross-sections

We can think of the Grand Hotel format as one variant of what I’ve called network narratives. Putting it generally, these are films that shift our attention across several somewhat linked characters and their projects.

Most films we encounter have a single protagonist, accompanied by helpers and facing some number of antagonists. Other plots have dual protagonists, perhaps cops who are buddies, or a man and a woman in a romantic relationship. A few films may have three protagonists, like Letter to Three Wives.

Another variation is the film with several protagonists, each given roughly equal weight. Usually the multiple protagonists share a goal, as in combat films, where they are united in a common mission. But when we have multiple protagonists pursuing different, largely unrelated goals, we have what I’m calling a network narrative.

What makes all these characters part of the same network? Any social relation. They might be relatives, friends, co-workers, classmates, neighbors, ex-lovers, or whatever. Also, mere proximity can connect characters; maybe they’re in the same hospital room or conference meeting or just in the same town.

As the film unfolds, we come to understand the array of characters and their connections. We follow one, then another, and we watch new relationships form. Sometimes hidden relationships are revealed to create a surprise. Some connections are distant, of the n-degrees-of-separation variety. The characters’ various purposes may run parallel, or they may intersect and clash—all more or less accidentally. Most plots of any sort are connected by causality, but network narratives are once tight (because of the pressure of the characters’ goals) and loose (because social ties can flow in many directions).

The advantage of the network approach is to yield a cross-section of life denied to more traditional linear narrative. Such plots can present, as Joseph Warren Beach puts it, a “comprehensiveness of view” that becomes “a composite picture of many distinct lives.” But the strategy raises problems too. The idea of a network narrative invites a dizzying expansion. X meets Y, who’s married to Z, the friend of A, who works with B, and pretty soon your story world is growing out of control. You need to constrain it somehow.

One way, as in Slacker, is just to sample one string of the network, moving from node to node. This generates a sort of “slice of life” plot, in the manner of Naturalist theatre. That snatches a few episodes from central characters’ lives without the customary setups and resolution. Bernard Shaw noted that “The moment the dramatist gives up accidents and catastrophes, and takes ‘slices of life’ as his material, he finds himself committed to plays that have no endings.” In film, we might think of one prototype of Neorealist cinema, The Bicycle Thieves. Baum’s framing narration of Grand Hotel, with its musing on stories without clear-cut beginnings or resolutions, tries for the same sense of what Zola called “a fragment of existence.”

Some of the literary models, such as The Lower Depths, accept a slice-of-life approach, without traditional climaxes and resolutions. Modernist writers pushed this possibility further, very open-textured networks. Dos Passos’ USA trilogy (1930-1936) is one example. Evelyn Scott’s The Wave (1929) presents seventy episodes from the Civil War, each concentrating on a different individual, although some characters reappear in sections devoted to others. A comparable strategy rules William March’s Company K (1933), with its 131 vignettes of World War I, with each soldier’s scene narrated in first person. Again, some characters reappear, but the network is largely a dispersed one.

Novels with well-defined protagonists occasionally strayed into a more lateral, open-textured approach. One example is the Wandering Rocks section of Ulysses, which fleetingly probes the minds and actions of about a hundred Dubliners moving through mid-afternoon. In Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway (1925), a sudden noise from a car stuck in traffic, followed by an airplane swooping above, causes various members of a crowd to think stray thoughts. Like Joyce, Woolf momentarily broadens the frame to register the reactions of characters unconnected with the protagonists, except by being present outside Buckingham Palace at the same moment. Only space and time create this network, and it’s ephemeral.

Bring us together

Given our appetite for linear narrative, some storytellers are bound to seek ways to tighten things up. Can we graft normal plot development—goals, conflicts, rising tension, climaxes, and resolutions—onto the network idea?

Yes. One way is to create the network through a circulating object, as in Tales of Manhattan, Au hasard Balthasar, American Gun, Twenty Bucks, or The Earrings of Madam de…. Sometimes the result will be episodic, but other times there will be a rising tension and a conclusion to at least some lines of action.

The most common way to constrain the network is to multiply the connections within the group. That is, don’t make the network loosely woven. So X meets Y, who’s married to Z, the friend of A; but A works with X, who is the cousin of B, who has been having an affair with Y, and so on. In other words, you create a “small world” defined by several connections among all the participants.

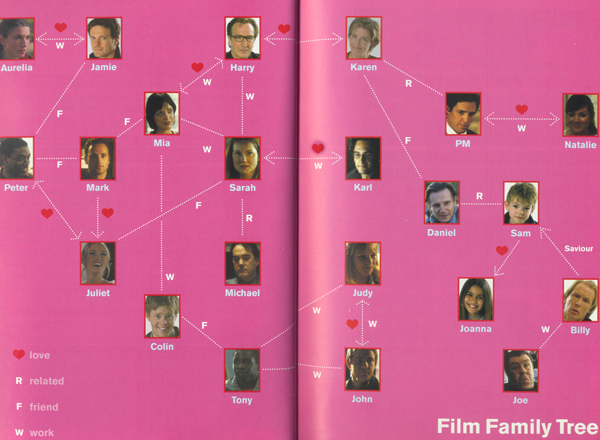

This small-word model is common in novels that create network narratives. Dickens, Balzac, and other writers have created complex degrees-of-separation plots. It’s likewise the pattern for most network narratives on film: several connections link many of the nodes. Here’s a diagram for Love Actually.

This chart is oversimplified because it doesn’t account for other relationships. Colin, for example, as the sandwich delivery boy, interacts with several of Harry’s employees. Still, at a glance you can see a fairly tight network.

Another way to constrain the network is to set limits of space and time. Slacker, like Mrs. Dalloway, explores a network established by spatial proximity; when we leave one character we pick up another nearby. The circulating-object option often presumes that the characters share a locale. Love Actually limits its intertwined stories to London, and still further to the Christmas season there. Louis Bromfield’s 1932 novel Twenty-Four Hours follows its Manhattan ensemble through one full day. (Compare that unlamented recent release, Valentine’s Day.) A 1938 British film, Bank Holiday traces several people across a weekend at a seaside resort.

The space can be more radically limited, as in Waldo Frank’s book of interconnected short stories City Block (1922). Perhaps influenced by Frank’s book, Elmer Rice wrote and staged Street Scene, a 1929 play that weaves together the lives of people living in a tenement. Their relationships are played out on the building stoop and the street in front. The play was filmed in 1931, and perhaps if it had been more successful, or had featured many big stars, we’d be talking about “Street Scene plots” rather than Grand Hotel ones.

Buildings are ideal for tying story lines together. Zola’s novel Pot-Bouille (1882) confines its action largely to an apartment house and the people who live there. Gorky’s play The Lower Depths brings together several characters in a flophouse. Inns, taverns, and hotels are natural points of convergence, and travelers naturally bring story action along with them. This is the narrative convention of l’auberge espagnole, based on the idea that in a Spanish inn you bring your own food.

When we have mostly strangers interacting in a constrained time and space, and when those interactions lead to traditional conflicts and resolutions (avoiding the slice-of-life pattern), we can speak of “converging-fates” narratives. Grand Hotel became the great prototype of converging-fates plotting.

Baum modernized the auberge espagnole idea by concentrating the action in a luxury hotel. She understood that these surroundings could motivate the chance meetings that propel the plot. She wasn’t alone. At the time her book was published, there were other “hotel” novels, notably Arnold Bennett’s Imperial Palace (1930). Whereas Bennett emphasizes the hotel staff and its routines, Baum concentrates on the guests. She motivates her comparisons across classes by making Kringelein a poor man having a final fling and making the Baron a penniless aristocrat keeping up appearances.

Baum showed how filmmakers who wanted an ensemble plot could bypass the sort of fragmentary, open-textured network seen in Dos Passos, The Wave, or Company K. She showed how to build more tightly integrated situations, with intersecting characters, each pursuing his or her goals and unexpectedly affecting other characters. The whole dynamic would take place in a rigorously confined setting and a sharply bounded period of time. The disparate story lines, knotting in certain scenes, would build to a climax. In Grand Hotel, all the characters’ fates come together when Preysing kills the Baron. Flaemmchen, terrified, rouses Kringelein and brings him into the crisis.

In such ways, a network narrative could become a variant of classical plotting, complete with exposition, conflict, crisis, and climax. Now Baum’s claim that the book traces mere fragments of life seems to be camouflage. Each protagonist’s fate has a linear logic; it’s just that the lines intersect.

If you’re a modernist, you find this a dilution of strong brew. You deplore the way fiction writers and moviemakers adapt avant-garde techniques to middlebrow taste. Yet if you’re a mainstream filmmaker, you can see that absorbing these techniques freshens up the norms. The crisscrossing destinies create an urgent pace, a new openness to chance and accident, and an invitation to imagine a patterning beyond that of straightforward single- or dual-protagonist plotting. Hollywood may feed on more “advanced” storytelling, but it doesn’t simply iron out the difficulties; in absorbing the techniques, it enriches its own traditions.

Thalberg predicted this change when the film was in production.

I don’t mean that the exact theme of “Grand Hotel” will be copied, though this may happen, but the form and mood will be followed. For instance, we may have such settings as a train, where all the action happens in a journey from one city to another; or action that takes place during the time a boat sails from one harbor and culminates with the end of the trip. The general idea will be that of a drama induced by the chance meeting of a group of conflicting and interesting personalities.

The last sentence isn’t a bad encapsulation of the converging-fates schema.

Hotel franchising

Thalberg was right, of course. Grand Hotel, in all its incarnations, encapsulated a narrative option that was irresistible. By 1955 Kenneth Tynan paid tribute to the fertility of the idea.

No literary device in this century has earned so much for so many people. Unite a group of people in artificial surroundings—a hotel, a life-boat, an airliner—and, almost automatically, you have a success on your hands.

Baum compared herself to the sorceror’s apprentice, who couldn’t stop her creature from splitting and rushing off in all directions. Critics detected traces of the novel and play in Translatlantic (1931), Union Depot (1932), and Hotel Continental (1932), all released before the MGM vehicle. These films do confine most of their action to a single setting, but they don’t multiply protagonists to the same extent as the original. A 1932 play, Life Begins, is closer to Baum’s model, finding converging destinies in a maternity ward. Some suspected that the 1932 film, released in May, was Warners’ effort to compete with Grand Hotel, premiering in April but not going wide until summer and fall.

MGM imitated itself in another 1932 release, Skyscraper Souls, which applied the formula to an office building. Faith Baldwin’s original novel Skyscraper focused on a working-girl romance, but the screenplay expanded the plot. A great many characters working in the skyscraper get involved in love affairs, a stock swindle, and an aborted jewelry theft. As with Grand Hotel, all the action transpires in one building.

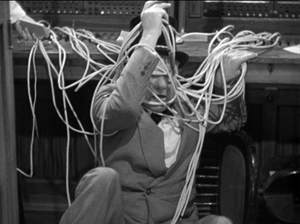

Like Strange Interlude, Grand Hotel inspired parody. In Paramount’s International House (1933) various personalities converge on a hotel in Wu-Hu, China, to buy the rights to Dr. Wong’s “radioscope” (aka TV). W. C. Fields, Stuart Erwin, Bela Lugosi, Franklin Pangborn, Cab Calloway, Rudy Vallee, George and Gracie, and the notoriously torrid Peggy Hopkins Joyce enliven the proceedings. There’s an allusion to the hotel switchboard in the original film when Fields gets tangled up in phone cables. He’s also flummoxed by Gracie Allen.

After one of Gracie’s non sequiturs Fields asks: “What’s the penalty for murder in China?”

A curious parallel surfaced in Die Wunder-bar, a German play premiered in February 1930, just a month after the opening of Grand Hotel’s stage version. Transposed to film, it became an Al Jolson vehicle, Wonder Bar (Warners, 1934). It has a fairly coherent threads-of-destiny plot. Flirtations, suicides, and musical numbers (including one with Al in blackface, of course) fill out action occurring in a single day. There was also Die Uberfahrt, a 1932 novel by Gina Kaus, translated as Luxury Liner and filmed under that title by Paramount in 1933. Variety called Wonder Bar “a ‘Grand Hotel’ of a Paris boite-de-nuit,” and Motion Picture Herald called Luxury Liner “Grand Hotel on a steamboat.”

The Grand-Hotel-on-an-X formula became a catchphrase, like Die-Hard-on-an-X of years later. We associate the phrase “Grand Hotel on wheels” with Stagecoach (1939) because that was used in its publicity. But reviewers had applied that phrase earlier, to Streamline Express (1935) and Time Out for Romance (1937)—the former involving a train, the latter an automobile convoy. The British import Rome Express (1933) was “Grand Hotel on a train” and Mitchell Leisen’s fine Four Hours to Kill (1935), set in a theatre lobby and lounge, became “Grand Hotel in miniature.” Fifty-four Ames Street, a screenplay apparently never filmed, was said to be “a sort of Grand Hotel in a New York apartment house.” Producers interested in Saroyan’s play The Time of Your Life saw in its tavern locale and migrating flocks of characters “an all-star vehicle somewhat along the lines of ‘Grand Hotel.’”

One critic worried that Winter Carnival (1940) was tantamount to “Grand Hotel on skis,” but F. Scott Fitzgerald, sweating over the script, had worried that it couldn’t be “a group picture in the sense that Stagecoach was, or Grand Hotel.” It had, he noted, “no sense of destiny.” That sense was much stronger in One Crowded Night (1940), an RKO B that I’m fond of. It might be called “Grand Motel,” as it brings together a preposterous number of plotlines at a desert auto court.

The Grand Hotel paradigm did not rest. The original film was remade, in more complicated form, as Week-End at the Waldorf (1945). There were other variants of the template—famously Lifeboat (1943) and Hotel Berlin (1945), less notably Ulmer’s Club Havana (1945) and the PRC cheapie The Black Raven (1943). Life Begins was redone as A Child Is Born (1940), and at the end of the decade Harry Cohn expressed interest in remaking it again. The play Flight to the West (1940), set on an airplane, showed Elmer Rice contributing to the trend.

By 1943, a Variety columnist was admitting that there was a tradition behind it all. “Ever since Boccaccio rounded up a herd of characters in his Decameron, dramatists have been utilizing the restricted space idea to make their stories more compact.” What he did not say was that most of Grand Hotel knockoff movies had been B-pictures.

Baum bitterly resented what had happened to her most famous work. “Countless cheap imitations and adaptations gave it a bad name. . . It all quickly became a mechanical toy. A formula, to be bought and sold on the supermarket.” That didn’t stop her from ringing changes on her model. Her play Pariser Platz 13 (1930), set in a beauty parlor, and her novel Martin’s Summer (1931), tracing a drama among strangers at a vacation resort, inevitably recalled her breakthrough work. She mined the vein again with Hotel Shanghai ‘37 (1939) and Hotel Berlin ’43 (1944). Things became risible when Variety announced that she was preparing a (never-filmed) screenplay called Grand Central Market, based on an idea by a busboy in the MGM commissary. But perhaps she wouldn’t have minded the jeers that she was milking her most marketable idea. “I know what I’m worth: I am a first-rate second-rate author.”

Catch them coming or going

The Grand Hotel converging-fates format got recycled for decades, in movies from The V.I.P.s and Hotel to Four Rooms and Auberge Espagnole. Network narrative as a general trend came back in a big way in the 1990s. In an essay for Poetics of Cinema, I counted some 148 examples just from the period between 1994 (Pulp Fiction, 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, Ready-to-Wear, Chungking Express, Exotica) and 2006 (Bobby, Colossal Youth, Selon Charlie), by way of Do The Right Thing, Magnolia, Sunshine State, Wonderland, and Happiness. Filmmakers, mostly non-Hollywood ones, revived and reformatted the old template. They could cunningly resolve some story lines, and so satisfying our fondness for closure, while also leaving some unresolved, and so satisfying our belief in realistic “slices of life.”

Although I should be fed up with such plots, I still find them intriguing. They can yield mystery, as we’re teased about the possible connections among the characters; their network pattern can be revealed or obscured by flashbacks, subjective sequences, frame stories, forking-path patterns, and other devices, as in Go and Once Upon a Time in Triad Society 2. The format can really test the ingenuity of a screenwriter.

Still, network plots pose unique problems. One is figuring out all the interactions in situ. How do you weave everything together? Apart from kinship and friendship, the easy links are chance encounters, merely passing in the street, watching somebody on TV, or, most desperate of all, the traffic accident. (Crash is only the most egregious instance.) Finding fresh ways to hook up your nodes is quite a challenge, as is devising a satisfying payoff for at least some of them.

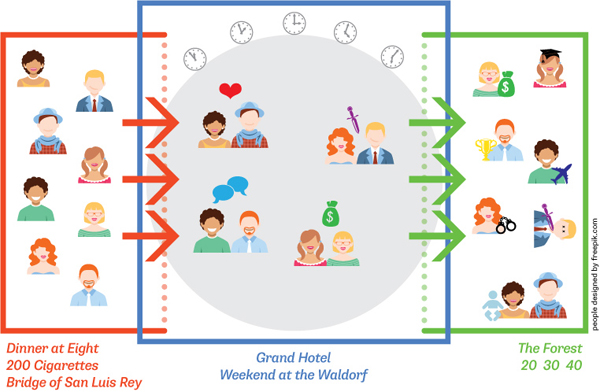

Another problem is more specific to the converging-fates option: the choice of “point of attack.” Taken just as geometry, the plot can be seen as having three phases. Here’s an infographic courtesy of our web tsarina Meg Hamel. On the left, the characters are independent. In the center–a closed environment like a hotel, or a more porous one like a holiday season–they are drawn together. They circulate and interact. On the right, we see them dispersing, all changed in one way or another.

The question is: Where do you cut into this process to start and end your plot? Some films, like In Which We Serve, try to trace the whole process more fully. We see it in a more spacious form in The Great Race and Cannonball Run. Perhaps The Rules of the Game would be another instance.

But most films of this ilk concentrate on the convergence, the central circle of interaction we see in Grand Hotel. That’s what we find in Mizoguchi’s Street of Shame, The Uchoten Hotel, Drive-In, Health, The Yacoubian Building, Monsoon Wedding, et al. Often there’s a time pressure too, as the clocks in the graphic indicate.

Or you the screenwriter could shift a step back and base your plot on the action before the characters commingle. My red block indicates a plot concentrating on this early phase. The dotted line indicates our seeing a little bit of the convergence.

The prototype is probably Dinner at Eight, a 1932 play made into a 1933 film (yes, also by MGM). The comic plot traces several couples invited to a dinner party. Some of them have one-off encounters before the big night, but the plot depends on the eventual convergence of everyone. The film stops just as the assembled guests step into the dining room. A modern parallel is 200 Cigarettes, which intercuts several guests on their way to a party. Again, we don’t see the party directly, but in an epilogue a montage of snapshots gives us some glimpses.

Probably the most famous example of pre-convergence plotting is the novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey. Thornton Wilder uses a flashback construction to trace the lives of the characters. At the start we learn that the bridge collapsed, killing them all, and then via an inquisitive priest we are taken back to the events that brought them to the same fate. By contrast, Claude Lelouche’s Il y a des jours…et des nuits saves the moment of convergence for a traffic tieup at the very end of the film.

Alternatively, you could build your plot at the other end, as indicated by my green box. Your story action begins with the dispersal of the characters who have already converged, though perhaps you show something of their encounters before they split up.

This is the rarest option, I think. One example is Benedict Fliegauf’s The Forest, which shows several people leaving a train station and proceeding on to their parallel, and fairly mysterious, lives. A more heavily motivated example is Sylvia Chang’s film 20 30 40, which initially brings three women together as passengers on an airplane flight before sending each off to her own pursuits. Although they live in the same neighborhood and their activities are intercut, the women never meet. Two films I haven’t seen seem to follow this parallel-dispersal pattern. In Urlaub auf Ehrenwart (Leave on Word of Honor, 1938), a commander gives his men leave for a day on their way to the front, and the plot follows each one’s experiences. It was adapted into a Japanese film, The Last Visit Home (Saigo no kikyo, 1945).

As with any plot scheme, the closer you look, the more variations and extensions you see. Sometimes it’s useful to see any one plot as a reconfiguration of other plots. The network principle–itself a threading of goal orientation, conflict, and other narrative devices–can be a beautiful meeting point of story possibilities. One reason I think filmmakers like these plots is that, somewhat like mystery stories, they are narrative to the nth degree. How many situations, characters, and unexpected connections and analogues can you squeeze into a single movie? It’s a challenge.

What crystallized in an MGM prestige production of 1932 seemed a fresh approach to film narrative. Even in the opportunistic ripoffs of the following decades, we can sense an excitement in tinkering with a new storytelling pattern. And of course some variants still seize us today. Just ask the audience making its way to The Second Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, or the young hipsters immersed in the mini-library that is Chris Ware’s Building Stories. Lately we haven’t seen many network movies, but I expect another wave. Like it or not, some story ideas never die.

My information about Vicki Baum’s career comes from Lynda J. King’s Best-Sellers by Design: Vicki Baum and the House of Ullstein (Wayne State University Press, 1988). I drew my Baum quotations from two curiously different editions of her memoirs, I Know What I’m Worth (Joseph, 1964) and It Was All Quite Different: The Memoirs of Vicki Baum (Funk and Wagnalls, 1964). The reviewer who called Baum’s novel cinematic was Herman Ould in “Experiments in Technique: Vicki Baum and Arnold Zweig,” The Bookman 79 (November 1930), 132.

Claus Tieber analyzes the Grand Hotel story conferences in “‘A story is not a story but a conference’: Story conferences and the classical studio system,” Journal of Screenwriting 5, 2 (2014), 225-237. In correspondence Patrick Keating has shared with me a story conference concerning Skyscraper Souls (MGM, 1932), in which the participants discuss transitions between scenes. Should the film cut from one plotline to another, or use camera movements, or have the characters link to one another? The filmmakers discuss Grand Hotel as a model for handling the problem. Thanks to Patrick for the information.

Joseph Warren Beach provides a helpful survey of experiments in mainstream fiction of this period in The Twentieth Century Novel (Appleton Century Crofts, 1932). I’ve drawn upon his chapter “The Breadthwise Cutting.” Shaw’s remarks on the slice-of-life plot are in his Preface to Three Plays by Brieux (Brentano’s, 1913), xv-xvi. In The Writing of Fiction (Scribners, 1924) Edith Wharton comments that English novelists of the early nineteenth century favored the “double plot,” a form that presented “two parallel series of adventures, in which two separate groups of people were concerned, sometimes with hardly a link between the two” (81). She considers this a “senseless convention,” but it seems to me another means of creating a network narrative. Sometimes the nodes connecting the groups become clear only gradually. There may be even a dose of mystery, as in Our Mutual Friend; the reader is encouraged to wonder how the two ensembles might be hooked up.

The diagram of the network in Love Actually comes from Peter Curtis, Love Actually (St. Martin’s, 2003), 6-7. Although at least one story line in the film doesn’t get fully resolved, Curtis is committed to a classical model: “I thought I’d like to have a go at writing that kind of film–to see if it was possible to write a film with nine beginnings, nine snappy middles and nine ends.” He declared himself inspired by Nashville, which I’d argue has a much looser texture and treats its story lines largely as slices of life.

Kenneth Tynan’s remark comes from his 1955 essay “Thornton Wilder,” reprinted in Profiles, selected and edited by Kathleen Tynan and Ernie Eban (Random House, 1995), 106. My citations of critical commentary on various films comes from the Hollywood trade press, as indexed in Lantern. Thalberg’s remark on Grand Hotel‘s likely influence is quoted from “Producer Discusses Pictures,” New York Times (3 May 1931), X6. Peter B. High discusses The Last Visit Home in his The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), 485-487.

My fullest treatment of network narratives is in Poetics of Cinema, in the essay “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance.” To the same subject Peter Parshall devoted an insightful book, Altman and After: Multiple Narratives in Film, which I plug here. A search of our site with “network narrative” as the key phrase will turn up several remarks on the format.

P.S. 23 March 2015: Thanks to Antti Alanen for a correction: I had accidentally written that Pot-Bouille was by Balzac, not Zola.

P.P.S. 31 March 2015: Rewatching Skyscraper Souls, I added a paragraph about it, which better sets up Patrick Keating’s information in the codicil. It’s a pretty good movie, in some ways more complex than Grand Hotel.

Francisco Ibáñez, 13, rue Percebe. With thanks to Vicente J. Benet.

Harry Potter and the Twelve-Year Boyhood

Kristin here–

Note: As far as I’m concerned, Boyhood and the “Harry Potter” films have been out long enough that there is no need for spoiler alerts. It would certainly help in understanding this entry if the reader had some knowledge of the Potterverse.

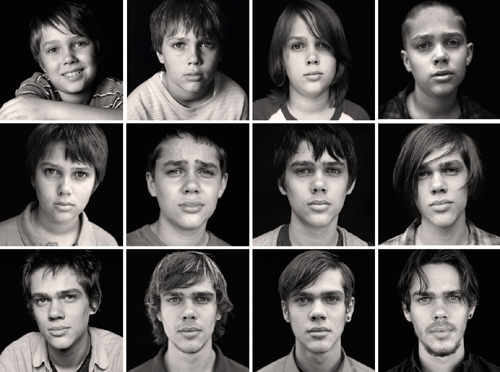

Apparently audiences who saw Boyhood in its premiere screening at Sundance in January, 2014, went in not knowing that the film had been shot at intervals across over twelve years. Once the reviews appeared, it became known that Richard Linklater had done so, recording the actors, most notably Mason, the boy at the center of the film, actually growing older over the course of nearly three hours. The result was an outpouring of enthusiasm from critics and art-film afficionados alike. Less so, perhaps, from more mainstream viewers who went to see Boyhood once the Oscar buzz heated up. (On Rotten Tomatoes, it is rated 98% favorable by critics and 83% by fans.) From its July release up to the recent Oscars ceremony, it was considered one of the front-runners.

The film’s Oscar campaign took a rather puzzling turn toward the end. The film, which was considered unique in its intimate portrayal of one boy growing up in an unstable family situation, was suddenly “Everyone’s Story,” as if it was so universal that we all could see ourselves in it. The double-page spread from the February 20 Hollywood Reporter (which shows photos from each year of shooting) is too large to reproduce here, but here’s the upper section of the right-hand page:

Virtually nothing in Boyhood‘s story reminded me of anything in my life from six to 18, though, yes, I did graduate from high school and go off to college. Maybe men who as children faced their parents’ divorces, physical abuse, frequent moves to new homes, and so on, would relate to the film and enjoy it more than I did. Or maybe less. I don’t think that seeing this as a universal portrayal of the human condition is very realistic, though that was an idea touted by many critics as well.

I was entertained until the last hour or so, when I realized that Mason was going to remaining fairly passive and sullen to the end. His sister Sam and mother Olivia seemed to be more interesting characters, since they had goals, held strong opinions (right or wrong), made mistakes, accomplished things, and so on.

As an actor, Ellar Coltrane spends much of his time listening to what other actors say to him. His reactions are limited in range and usually involve a fairly neutral expression. In fact, I began to think that his performance is the perfect illustration of Kuleshov’s most famous, though lost, experiment: the one where supposedly the same footage of actor Ivan Mosjoukine looking offscreen was cut together with shots of things like bread, a dead woman, a child playing–things that would logically invoke widely varying emotions. Audiences supposedly praised Mozhoukin’s performance, saying he expressed hunger, sorrow, and happiness admirably. Accounts of what was shown in the shots Mosjoukine was “looking at” vary, and it’s possible the experiment was planned but never made. Whatever was the case, however, the principle seems plausible. What we find in a shot, including a shot of a face, depends on what shots precede and follow it.

I think something of the sort happened in Boyhood. Some expert professional actors, plus Lorelei Linklater as Sam, enacted scenes with Coltrane. Spectators may have imagined how a child would react to the events of the scene and read those appropriate emotions in his frequently impassive face. Otherwise it seems odd that people watching a fairly good art film offering a close, realistic study of a family over a period of twelve years, would consider Boyhood such a moving and historically momentous film.

Putting aside the “Everyone’s Story” appeal, Linklater’s film offers the unique case of a feature film shot across the actual twelve years covered by its story, allowing the actors, most dramatically the young ones, to age before our eyes. That’s impressive in itself, with the producer/director/writer Linklater managing to sustain the momentum of the financing and the actors’ cooperation across the full twelve years. I don’t wish to take anything away from that accomplishment, just to put it in perspective a little.

Wait, did I miss something?

As David has pointed out, films that are innovative, even experimental in some ways often compensate by drawing more heavily upon conventions from other areas. Although the jumps from year to year are somewhat disorienting, Linklater helps us out. He draws upon the old device of having the haircuts of the characters differ each time, even emphasizing this way of marking the passage of time by showing Mason getting an unwanted buzz-cut onscreen. He also characterizes Mason in fairly standard shorthand ways. At the opening he seemingly contemplates death by staring at a dead bird that he is burying. His characterization as slightly rebellious is pretty conventional: looking at semi-clad models in a catalog, allowing himself to be goaded into spray-painting graffiti, flirting with a waitress when he should be clearing tables while working at a local restaurant. Apart from the innovative device of the actor growing across a single film, he’s not a particularly original character.

I think, however, that Linklater does something much more interesting with Boyhood, and it has to do with the narrative structure rather than the aging of the actors. The film tells a deliberately sketchy story. Each one-year segment is obviously part of the characters’ lives, but there is little attempt to bridge the gap between them to create a conventional narrative flow. There are no dialogue hooks to create smooth transitions, no overt continuing goals, just Mason’s implicit desire to make sense of life and Olivia’s to find a happy path forward for her family.

Most obviously, events that would ordinarily be explained or motivated are simply ignored. The cuts from one segment to another are sometimes jarring, sometimes subtle enough that we don’t immediately realize that we’re jumped forward another year. As reviewer Kurt Brokaw points out, there are “no turning calendar pages, no inter-titles signaling the passage of time.”

What happens to Olivia’s third husband? (I’m assuming here that Mason Sr. was her first husband.) We see him before the marriage at a party, and he seems a decent enough sort. In a later segment he is married to Olivia. We see little of him, apart from one evening when his sits on the porch drinking beer and berating Mason for coming home late. Will he turn into another drunken abuser, like the second husband? Instead, he just disappears. Possibly in real life the actor playing him dropped out, in which case it would have been easy enough to mention his death or departure–at least something that would motivate his being gone. We don’t, however, get such an explanation.

Similarly, we are concerned when Olivia flees the home of the second, truly abusive husband, taking Sam and Mason but leaving their two step-siblings behind. Sam is upset and begs to take them along, but Olivia is concerned only to escape with her own children. Do the two kids left behind bear the brunt of their father’s wrath? Do they continue to be abused by him or do they somehow break free? These are important questions, especially after the extended and tension-filled scene in which the drunken man threatens Olivia and all four children. In a conventional narrative they would most likely be answered in some fashion.

Another plot point that I wondered about was the sudden introduction of religion into the narrative when Mason Sr., who has shown no signs of religious inclinations, remarries into a profoundly Christian family. Does Mason Sr. become a believer himself, or does he just avoid strife by attending church with her and her parents?

These and other questions occurred to me and were left unanswered. This is clearly not sloppy storytelling but a systematic strategy. Linklater forces us at each leap forward to struggle a bit to figure out where in these characters’ lives we are now–where they’re living, who is still part of their story and who has departed.

Indeed, I’ve never seen a film that compresses time in such a way as vividly to suggest how many people come and go in our lives, some to reappear, some not. I recently was contacted by a first cousin once removed whom I lost track of when my family moved from the Midwest in 1963. Retired, he was sitting in on a film class that assigned Film Art and decided to find out if one of the authors might be his cousin. Turned out he was living in Milwaukee and I in Madison for decades without knowing it. These things happen, and they do seem as abrupt and surprising as in Linklater’s film. That I can identify with.

I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a narrative film made within or at least on the fringes of the American production system with such frequent gaps and where so many links in the chain of cause and effects are missing. That, in my opinion, is the true innovation of Boyhood, but it’s not something the publicists can sell to the public and the Academy voters.

Right before your eyes

When I heard about the most famous aspect of Boyhood, I immediately thought, “I’ve seen that happen in the ‘Harry Potter’ films.” I was far from the first to think that. An early–perhaps the first–link between the Boy and the Boy Who Lived came as part of the publicity campaign for the film. From July 4 to 10, 2014, the IFC Center in New York ran all eight Potter films in a row as part of a series “honoring the release of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood.” IFC, of course, financed the film and released it in the US on July 11, 2014. Brilliant! as Harry would say.

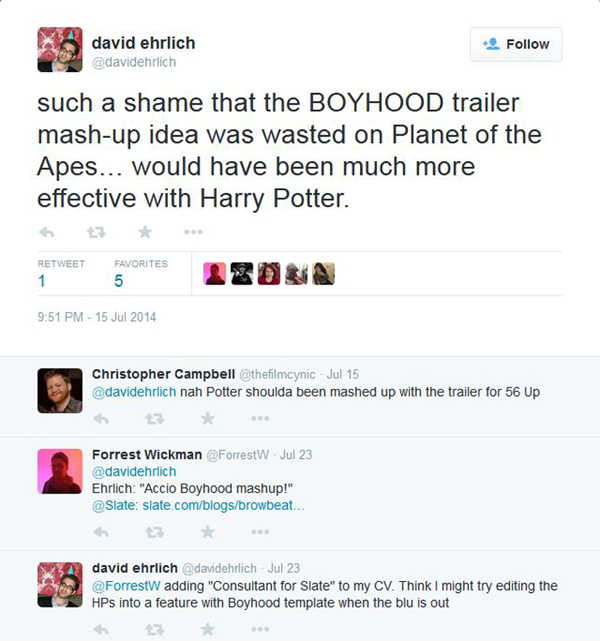

The professional and amateur fans on the internet then took over. On July 15 David Ehrlich (a freelance critic and among other things, Time Out NY‘s associate film editor) suggested a Boyhood/Potter mashup.

You cannot suggest such a mashup on the internet and not have someone take up the challenge. On July 23, Chris Wade posted Potterhood on Slate‘s culture blog, Browbeat, linked in the second comment above. (“Acciao” is a charm for summoning something.) Hence Ehrlich’s last comment in the thread above. A second mashup, also entitled Potterhood, appeared on IGN on February 6, 2015. Hard on its heels was the Honest Trailer – Boyhood, by Screen Junkies, posted on YouTube on February 10, which makes passing reference to Harry Potter. A sequence of five consecutive titles and shots:

The “Harry Potter” series (or, strictly speaking, serial) is only the most recent and well-known example. There have been other “growing-up” series and even a growing-up-and-growing-old series, which Christopher Campbell refers to in the first comment on Ehrlich’s tweet.

Justin Chang pointed out one precedent: “If the ‘Before’ movies are essentially Linklater’s riff on Rohmer, each one an endearingly loquacious two-hander played out against an idyllic Old World setting, then ‘Boyhood’ is unmistakably his tribute to Truffaut, who directed perhaps the greatest movie ever made about restless youth, ‘The 400 Blows.’ Similarly, the French master’s extended collaboration with actor Jean-Pierre Léaud as Antoine Doinel feels like an early template for what Linklater and Coltrane have pulled off here.”

There are wheels within wheels here. The Doinel series was mentioned to Daniel Radcliffe during an interview, and he responded, “The only one I’ve seen is The 400 Blows. Funny enough, I was asked to see that by Alfonso Cuarón, when he directed the third Harry Potter film. As a reference for Harry and his angst.”

Truffaut’s Doinel series went for a full twenty years, though not with yearly installments: The 400 Blows (1959), Antoine and Colette (1962, a short included in the anthology film Love at Twenty), Stolen Kisses (1968), Bed & Board (1970), and Love on the Run (1979). Unlike the “Harry Potter” series, these films were not planned ahead of time as a group. Truffaut would occasionally pop them in between his other films. They came out after some of his best films–Stolen Kisses after The Bride Wore Black, Bed & Board after The Wild Child, and Love on the Run after The Green Room. At the time we thought of them as Truffaut taking a break after a more difficult project. None of them lived up to the original, but we certainly did watch Jean-Pierre Léaud grow up.

Other critics have mentioned what has come to be called the “Up” series, which began as a television program, Seven Up! (1964) directed by Paul Almond. It consisted of interviews with 14 seven-year-olds. Michael Apted has continued the series with another film every seven years beginning with 7 Plus Seven (1970) and continuing, with the most recent being 56 Up (2012). One participant dropped out permanently, three skipped some episodes, but 56 Up interviewed 13 of the original 14, a remarkable achievement in showing the aging processes across 48 years and still going. Some people have found watching the series a profound experience. Roger Ebert wrote two four-star reviews of it, one in 1998 and another in January, 2013, a few months before his death. He called it “an inspired, even noble, use of the film medium.” But this series is documentary and perhaps not entirely a fair comparison. It is worth noting, though, that Jonathan Sehring, whose IFC had previously produced Waking Life, said that when Linklater pitched Boyhood to him, “The only thing I could draw as a parallel was Seven Up!”

I also wonder if back in the 1930s and 1940s some viewers found it moving as well as amusing to watch Mickey Rooney grow up in the Andy Hardy series, from A Family Affair (1937) to Love Laughs at Andy Hardy (1946), plus a revival, Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958), for a total of twenty films. This series was not intended as such at the beginning, but once the popularity of the character was apparent, MGM’s B unit cranked out two or three films a year and clearly planned to keep going indefinitely. These films had self-contained stories, but the subject matter was age-appropriate as Rooney, who was 17 at the time the first film was released, grew older.

Again, all this is not to denigrate Linklater’s film. It’s just a case of this blog seeking again to point out that almost nothing comes out of the blue with no historical precedents or conventions informing it. Certainly none of these series tried the sort of broken chain of causality that Linklater devised.

The Potter connection

Of all the series mentioned above, “Harry Potter” is most pertinent to Boyhood. Their production periods overlapped considerably, and their directors faced similar major challenges. This despite the disparity in their finances. “Harry Potter” had a huge budget supplied by Warner Bros., ranging from the lowest at $100 million for Chamber of Secrets to the highest at $250 million for Half-Blood Prince. (These are the budgets as publicly acknowledged, taken from Box-Office Mojo, which has no figures for the last two films.) Boyhood had a lean budget of $200 thousand for each of the twelve years and totaling about $4 million with postproduction and other expenses added in. Still, as we shall see, the challenges really had nothing to do with the budgets.

I didn’t see Boyhood until the day after the Oscar ceremony, when it was still playing in our local second-run house. I was surprised to discover that it includes references to “Harry Potter,” though to the books, not the films. These are among the several pop-culture and historical references (the Obama-Biden lawn-sign scene, various popular songs) that cue us as to which year of the twelve we have reached.

Early on Olivia reads a passage from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets to Mason and Sam. We don’t see the cover of the book, but it’s a passage that clearly identifies which entry in the series it is. Chamber of Secrets came out in the USA on June 2, 1999. (Incredible as it now seems, the American releases of the first two books were roughly a year behind the British ones and didn’t reach a simultaneous release date until Goblet of Fire in 2000.) The kids are obviously fans, since later they wear costumes to attend the book-store release of Half-Blood Prince, which dates the scene precisely as July 16, 2005. I don’t think the use of Rowling’s series is a random choice. The first six books cover six years in the educations of Harry and his friends at Hogwarts, with the seventh and final one following their attempts to thwart the villainous Voldemort. All begin in the summer, often specifically including Harry’s July birthday. The first six end as the school year concludes, and at the climax of the seventh, Harry, Hermione, and Ron return to Hogwarts for Voldemort’s defeat.

Both Linklater’s feature and the “Harry Potter” film serial face the challenge of retaining the child actors across a lengthy period of shooting. Moreover, neither Linklater nor the “Harry Potter” filmmaking team started with a complete script. The script for Boyhood was written year by year, with input from the actors. The early “Harry Potter” films were made before Rowling had completed her books, and she seldom shared information about what would happen in the upcoming ones.

The boyhood of the Boy Who Lived

Much has been made of the fact that Linklater managed to keep Coltrane committed to the project to the end. Had he decided not to go on playing Mason, the project would presumably have ended. No one connected with the film has ever suggested that the film could have been finished. There was no option of forcing him to commit at the beginning to the full twelve years of shooting, since California law forbids film contracts lasting longer than seven calendar years. (The “De Havilland” law from the 1940s was based on a lawsuit by Olivia de Havilland that changed the Hollywood contract system forever, a story quite interesting in itself.) Given that constraint, however, the production signed Coltrane for the initial seven years and then gave him a second contract for five years. Legally there was one point at which he could have bailed, but presumably the filmmakers would not have forced him to stay with the project if he had badly wanted to stop.

Lorelei Linklater, the director’s daughter, played the supporting but important character of Sam. While Coltrane never wanted to quit, she at one point did, and Harry Potter was involved. The director revealed this last month in an interview in The Telegraph:

Ironically, it wasn’t Coltrane who rebelled against this extraordinary commitment, but Linklater’s own daughter Lorelei. Three years into shooting Boyhood, when she was coming up to 12, she asked her father, ‘Can my character die?’ ‘She wanted out,’ Linklater says now. ‘But that was just one year.’

He learnt the true story behind Lorelei’s rebellion only last month when they were in England, and visited the Harry Potter sets at the Warner Bros studio tour. In one scene in Boyhood, Mason and Sam dress up as their favourite Potter characters and go along to a midnight sale of the latest Harry book. ‘I had Lorelei dress as Professor McGonagall, though I think she wanted to be Hermione,’ Linklater recalls. ‘Those stories were so real in her life. She thought she was going to get a letter from Hogwarts saying she could go there. She thought she might date Harry Potter. Not Daniel Radcliffe, Harry. So I think us filming that scene felt to her that we were belittling that, invading her space. She couldn’t admit it then. But she can now.’ He shrugs, ‘It was a daughter-dad thing,’ he says. ‘Not actress and director.’

Given Linklater’s daughter’s intense involvement in the Harry Potter universe, one wonders if the idea for Boyhood was, at least unwittingly, inspired by Rowling’s creation. By the time the deal for support and casting of Boyhood was settled in 2002, four of the books and the first film had come out. Not that it’s important to my points here, but it’s intriguing. If true, then certainly Linklater took his own project in a completely different direction.

Obviously Linklater persuaded Lorelei to continue, which is all to the good of the film. Mason has a lot of troubles, and having his sister die probably would seem too great a bid for sympathy by the filmmakers.

On the other hand, the “Harry Potter” producers faced the real possibility of having to replace some of the child actors, given that a highly expensive and popular series could hardly shut down because, say, Daniel Radcliffe or Emma Watson decided to leave or came to look too old for his or her role. Certainly there are so many students at Hogwarts that the minor parts could have been recast without difficulty. At minimum, though, it was important to keep the central and the important supporting roles constant: Harry, Hermione, Ron, Fred and George, Ginny, Neville, Luna, and Draco. Obviously keeping the actors in the adult roles constant was desirable as well, though the one replacement that proved necessary didn’t scuttle the series.

Warner Bros., though prescient about approaching Rowling for the rights early on, had little evidence that the first book would be as successful in the US as it had been in the UK. In 2011, Rowling wrote an informative article about her relationship with the series’ main screenwriter, Steve Kloves, who penned all the scripts except for that of Order of the Phoenix. She describes her first meeting with him, just before going into lunch with a big studio executive. (This would have to have been in the period from late summer of 1997 to early autumn, 1998.) She mentions being wary about being introduced to Kloves.

He was going to butcher my baby. He was an established screenwriter, which was just plain intimidating. He was also American, and we were meeting shortly after a review of the first Potter book in (I think) the New Yorker, which had stated that it was unlikely the British idiom would translate to an American audience. You have to remember that my first Warner Bros. meeting did not take place against a backdrop of massive American success for the novels. Although the books were already very popular in the U.K., it was still early days in the U.S., and I therefore had no real means of backing up my opinion that American fans of the book would rather not have Hagrid “translated” for the big screen, for instance.

Odd though it seems now, the “Harry Potter” actors were initially contracted only for the first film. By number three, Prisoner of Azkaban, there was already talk of a change of the young central actors. Radcliffe remarked in an interview, when asked if he thought at the start that he would do all seven movies, “I was never sure I was going to do any of the films, other than signing on for the first and second. After that, it was always going to be: We’ll take it one film at a time.” This suggests that the contracts were made film by film throughout, and that Linklater had a better chance of retaining his main actors than the “Harry Potter” producers did.

There was in fact considerable talk during the production of the “Harry Potter” series that one or more of the child actors would be departing. (The quotations with dates in brackets below are from the imdb news pages for Daniel Radcliffe , which is a handy chronology of information concerning the film series, often excerpted from sites behind paywalls.)

[5 Sep 2002] Harry Potter star Daniel Radcliffe has resigned himself to growing out of the child wizard movie role–literally. The 13-year-old actor has finished filming the second installment of the adaptation of J. R. Rowling’s massively successful seven strong children’s book series, but his voice has already broken and he’s just had a growth spurt. He says, ‘In a couple of years, I might have changed so much that I look wrong for the part–even though Harry grows with the books.”

[22 Oct 2002] Another company of young actors is expected to take over the principal roles in the Harry Potter film franchise beginning in 2004 for the fourth movie, Chris Columbus, the director of the first two Potter movies, predicted Tuesday. Noting that the current stars, Danial Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint will all be teenagers next year, Columbus told Reuters. “If I were a betting man, I’d say they’ll probably stop after three.”

Indeed, the delays with the third film had allowed the cast to grow more than between the first and second, and the difference is quite obvious in Prisoner of Azkaban (above).

The producers perhaps realized by this point that, although the first two films had been released one year apart (Nov 2001 and Nov 2002), the pace could not be maintained. Indeed, the final film was released in July of 2011. This meant that although seven years of plot duration had passed for Harry and his friends, it took ten years for the films to come out. In most cases there was a one-and-a-half to two-year gap between releases, which came in November or June/July.

The following year there was renewed speculation, this time that the main children would be replaced for the fifth film:

[18 June 2003] Although analysts have suggested that the three young stars of the Harry Potter movies are quickly outgrowing their characters, the Reuter News Agency on Tuesday, citing an industry source familiar with the matter, reported that they will likely return for the fourth Potter film, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, due to be released in November 2005. By that time, Daniel Radcliffe, who portrays Harry Potter, will be 16 years old. Reuters quoted Seth Siegel, founder of The Beanstalk licensing and marketing consultancy group, as warning that if the stars are not replaced by younger actors, “licensing will fade away.” Wendi Green, an agent for child actors with Abrams Artists Agency, told the wire service, “If [they] are too old, kids can’t relate to it.”

Tom Felton, who played the young villain Draco Malfoy throughout the series, said in a 2011 interview that “We all feared that after the fourth film that they were going to get rid of us and start again with new kids. So yes, we’re very proud to have made it through.”

The rumors about the departure of Radcliffe or others continued fairly late into the series:

[4 March 2007] British actor Daniel Radcliffe’s representative has confirmed that he has signed on to start in the final two films in the Harry Potter series. […] The hit franchise, which continues with the fifth installment, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, later this year, has grossed $3.5 billion globally at the box office. Rowling recently announced that the seventh and final book in the series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, will be published on July 21, but no film start date has been officially set.

Before the release of the final film, Kloves revealed that the departure of the main actors would have caused further upheaval in the series: “Emma was always the one who, we thought might leave, and I always said that if one of the kids left I would leave. And I would have because I only wanted to write for those three. I’m actually kind of amazed they all ended up doing it. It was the most important thing that happened to the movies.” Kloves’ continued participation obviously was crucial not just for keeping the series consistent in tone, but because he also had established a rapport with Rowling that gave her confidence that her books were being respected.