Archive for the '1910s cinema' Category

Manual labors

The Tin Star (1957).

DB here:

Type “screenplay writing” into Amazon and you’ll get over 6000 hits. Some of those books will be biographies of writers or screenplays of released films. But there’s still a huge number of DIY books with titles like How to Write a Movie in 21 Days and Writing Screenplays That Sell. A lot of people are apparently only one manual away from a finished script.

Screenplay manuals trigger suspicion. Can it really be that easy? Wouldn’t this be a paradise for grifters? A successful writer would hardly share trade secrets, so most of these books would be written by losers and wannabes. And if you read enough of the manuals, you’ll see the inevitable repetition of banalities. Make your protagonist “relatable.” Keep the conflicts going. Try for a twist.

Reading through them can be mind-numbing, but if you’re interested in how filmmakers tell stories, sometimes they can open up your thinking. Or so I’ll argue.

DIY scripting

The tide of manuals rose during the 1910s, when the emerging American studio system was seeking talent. The tide subsided between the 1930s and the 1960s, when screenwriting was contract labor in that system. But as filmmaking turned “independent,” ambitious people outside the industry could break in with an original script. Manuals, most famously Syd Field’s Screenplay (1979), began to pop up, and the market for how-to books expanded. Field’s book remains in vigorous circulation today, among many competitors.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

If your research touches on matters of style, you may find it illuminating to study the way practitioners pick solutions to practical problems. Which is to say that the manuals can point us toward norms. Norms are, I’ve argued, like a menu of more and less preferred options for treating the material. We developed this angle of inquiry in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, and now it seems well-established that the manuals can sometimes point us toward tacit norms of construction or visual style. For examples of how this can work, see Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood, my The Way Hollywood Tells It, and Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir. Many of our blog entries have also explored these paths. With screenplay manuals, we just have to be particularly careful to distinguish valuable data from bilge–which means checking the manual’s precept against many films.

And we shouldn’t expect the manuals or professional journals to identify every normalized device. For example, screenwriters now love to start scenes with friends greeting one another with “Hey” and “Hey,” but I doubt that there’s an explicit decision to avoid “Hi.” Similarly, I’ve never found anyone writing in the classic era who mentions the common Hollywood device of the double plot, with one line of action devoted to a goal-oriented activity and another, interdependent one devoted to heterosexual romance. Even the rather elaborate 180-degree classical editing system wasn’t apparently spelled out anywhere; it was learned by imitation and reinforced because it was economical and efficient. People can learn and follow rules that are simply taken for granted as “the way we do things.”

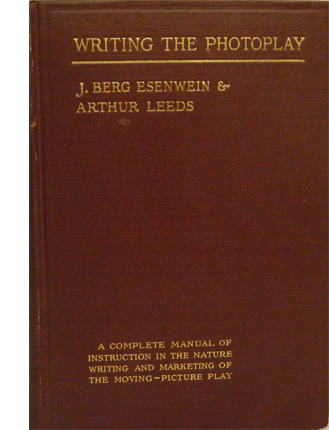

I think my soft spot for the manuals owes a good deal to my long-term affection for one item I saw in a 1913 guide. J. Berg Esinwein and Arthur Leeds’ Writing the Photoplay contains a lot of hints about standard practices of the period, but one of their diagrams changed my basic attitude about silent film technique.

The cinematic stage

In the late 1990s I became interested in the norms of scene staging in early film. I assumed that filmmakers had to call attention to story action without benefit of cutting to closer views, so I tried itemizing in a straightforward way the staging choices that could guide the viewer’s eye.

Many of the choices could be called “theatrical.” Lighting and setting could emphasize an actor’s gesture or facial expression. Performance factors operated as well, especially since actors were typically facing the viewer. Filmmakers’ reliance on these cues seemed to confirm the standard impression that early film was less “cinematic” than what came later.

Yet there were purely pictorial factors in play as well–notably, the placement of figures in the overall image. Composition of the frame, as in painting (and theatre) played a crucial role in guiding our attention.

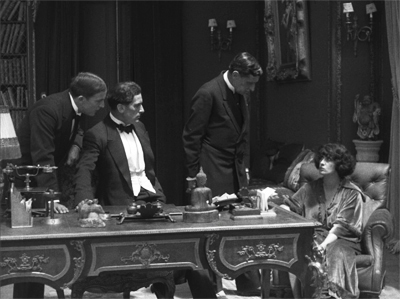

There was something else. I was fascinated, for reasons sketched here, with the depth that many scenes in “tableau cinema” displayed. Here’s a quick example from Alfred Machin’s Le Diamant noir (1913). The entire film is available from the Belgian Cinematek.

The young secretary Luc is accused of stealing the missing diamond. He protests his innocence, but the accusation will force him to leave the country.

All the cues I’ve mentioned are at work here: centered figure placement, frontally facing characters, attention-grabbing gesture, favorable setting (the rear doorway and curtains highlight Luc’s arrival), and so on. In addition, a tunnel of information bores through the frame, leading from the distance and culminating in action in the foreground.

But this tunnel couldn’t fairly be considered “theatrical,” since if the action were played on a stage, not all viewers would have the optimal view presented in the shot. Most of the audience simply couldn’t see this alignment of players. Theatrical staging tends to be lateral and fairly shallow, so that people sitting in different seats can all see the scene. A good part of planning a stage production is calculating sightlines. But in film, there’s only one sightline, that of the camera lens.

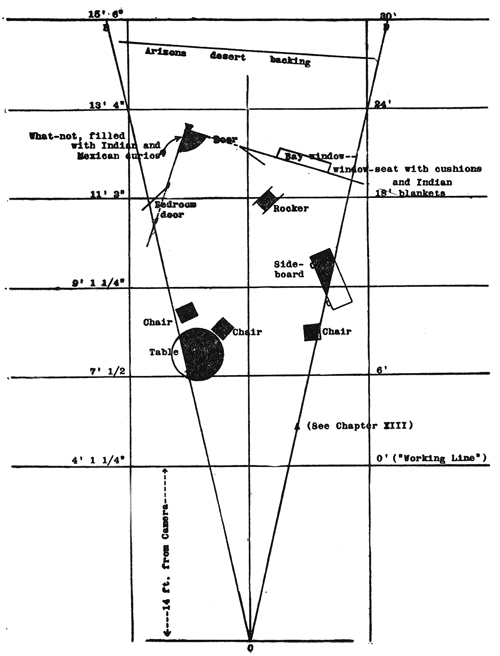

We tend to see film space as cubical, a room with a missing fourth wall. Actually, the playing space–what Esenwein and Leeds call “the photoplay stage”–is a tapering pyramid whose point touches the lens. Because the film image captures an optical projection, the space is narrow but deep. The authors provide a diagram of a scene to explain. (For the sake of clarity, I’ve removed some of their annotations; the full version is on p. 160 of their book.) The effect is of wedge shape that carves into what would be the wide space of a theatre scene.

In 1910s cinema, the camera lens (at point 0) is assumed to be some distance from the “working line,” the layer of maximal attention. For some filmmakers this line was nine or eleven feet from the camera, rather than the 14 feet assumed here. The rest of the space falls away in the distance, and depending on the lens and lighting used, these areas can be in more or less sharp focus. Filmmakers of the period often marked out the pyramid on the studio floor so that actors would know when they were out of shot.

This diagram makes explicit many of our taken-for-granted notions about film space. Someone moving closer to the camera gets larger, of course; but the figure also blocks out more and more of the background as the pyramid narrows. An actor’s forward movement on the stage inevitably takes up a small part of the overall area, but in cinema forward-thrusting action can dominate the frame.

Just as important, the fixity of the lens makes it possible to choreograph actors with a precision impossible in theatre. Luc’s confrontation with his employer in my second frame gives him pride of place, but once he’s slumped at the foreground desk, he can move his head and clear the central zone for us to see a servant waiting in the distance. In tableau cinema, staging isn’t just “blocking.” It’s blocking and revealing, a constant flow of information presented through shifting arrays of figures. I provide several examples in the lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

My heightened awareness of the visual pyramid made me more sensitive to staging in all periods of cinema. We might think that after the tableau cinema period, when filmmakers became more dependent on editing, their reliance on the “photoplay stage” vanished. But of course every shot, close or distant, presents us with the visual pyramid, and some filmmakers relied upon it to provide the graduated layers of space in an edited sequence. Specifically, the “deep focus” that became a favored technique of 1940s cinema around the world would seem a modernization of the principles of the 1910s recognition of wedge-shaped playing space. Here’s an outrageous example from Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941), shot by Gregg Toland after Citizen Kane.

Less punchy imagery than this suggest that the skills of 1910s staging were never really lost. Another passage from Ball of Fire brings Professor Potts to the foreground in a way reminiscent of Machin’s film. Of course it helps when Gary Cooper is the tallest galoot in the scene.

Cinema’s visual pyramid becomes almost sadistic at the climax of Anthony Mann’s Tin Star (1957). The young sheriff stops a lynching by shaming the town bully. The bully responds as you’d expect, but not in the sort of shot you’d expect.

Mann’s earlier films had experimented with foregrounds thrusting out at the viewer, but this sequence carries the idea to a limit. The actor collapses against the camera, inadvertently proving how lines of cinematic sight converge at the lens–that is, at our viewpoint. Try doing this on the stage!

This entry is more a piece of intellectual autobiography than anything else. I doubt many other people were opened up to the intricacies of staging thanks to a diagram in an old book. I mean it just as an example of how reading manuals can set you thinking about the expressive possibilities of film, and taking you in directions that you couldn’t predict.

More recently, in writing Perplexing Plots, I poked into manuals for would-be fiction writers, an area that literary historians seem to have neglected. These manuals yielded a lot of principles of what people thought went into good storytelling. In particular, I found that while Henry James and Joseph Conrad were making arguments about viewpoint and chronology, so too were people writing how-to manuals. The books indicated a new awareness of these techniques among writers aiming at mass audiences.

Terry Bailey surveys and analyzes early manuals in “Normatizing the silent drama: Photoplay manuals of the 1910s and early 1920s,” Journal of Screenwriting 5, 2 (Jun 2014), p. 209 – 224. For a comprehensive overview, see Steven Price, A History of the Screenplay.

The main argument here is developed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

Ball of Fire (1941).

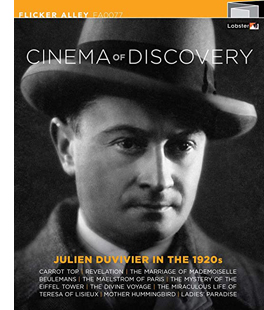

When the image ruled: Julien Duvivier in the silent era

Maman colibri (Mother Hummingbird, 1930).

DB here:

Rewind the tape of film history. What if cinema had been invented as a perfect audiovisual medium, with images exactly synchronized with sound? What would the evolution of film form and style have been like?

Actually, Edison and other early inventors wanted sound to accompany the picture. Technical obstacles to sync sound initially proved too strong, and the fact that the public approved of the silent image led to a delay in fulfilling what André Bazin called “the myth of total cinema.”

It’s long been felt that this delay was a good thing for the artistic development of the medium. Perfect image/sound coordination would have led filmmakers to a line of least resistance, a simple reliance on recording what was taking place in front of the camera. The absence of dialogue forced filmmakers to develop techniques of visual storytelling. “The time of the image,” thundered Abel Gance, “has come!”

Some film techniques were borrowed from theatre and painting, but others became identified closely with the moving image. Techniques such as camera movement, analytical cutting, and rhythmic crosscutting, have analogs in other arts but remain distinctly “cinematic” (chiefly because of cinema’s ability to control duration). During the 1910s and 1920s, filmmakers refined pictorial narrative in ways that couldn’t have been foreseen earlier, and avant-garde movements showed that the new medium had remarkable abstract and non-narrative possibilities as well.

Because of all this, it seemed that sync sound came along just when the silent cinema had reached an expressive peak. By then, people knew the powers of the moving image, and so could integrate sound with it to create an audiovisual art form.

I think there’s a lot to be said for this viewpoint, though it was often used as a cudgel to beat early talkies as “uncinematic.” There’s no denying that many filmmakers who made outstanding silent films, from Hitchcock, Lang, and Ford to Lubitsch, Eisenstein, and Renoir, managed to retain pictorial richness while relying on the unique contributions sound could make. In a teaching exercise, Eisenstein asked students to plan the filming of the assassination of Julius Caesar as a silent film, and then go back and reconceive it as a sound film. That way, the new synthesis could exploit the strengths of both ingredients.

Julien Duvivier’s silent films are good examples of the push toward maximal expressivity by means of visuals. He accepted the coming of sound, even welcoming color and depth, but by then he had already accepted the 1920s urge toward an overwhelming pictorial experience. At one level, he saw the need for spectacle–either shooting on striking locations, employing masses of actors, or creating flamboyant studio sets. At another level, the visual storytelling could be more inward-turning. How could moving images illuminate the thoughts and feelings of characters, the access to minds given through language in prose fiction and on stage? We can see in Duvivier’s late silent work a pressure in both directions: a love of eye-smiting locations either found or fabricated, and an urge to plunge into characters’ minds at every moment.

Julien Duvivier’s silent films are good examples of the push toward maximal expressivity by means of visuals. He accepted the coming of sound, even welcoming color and depth, but by then he had already accepted the 1920s urge toward an overwhelming pictorial experience. At one level, he saw the need for spectacle–either shooting on striking locations, employing masses of actors, or creating flamboyant studio sets. At another level, the visual storytelling could be more inward-turning. How could moving images illuminate the thoughts and feelings of characters, the access to minds given through language in prose fiction and on stage? We can see in Duvivier’s late silent work a pressure in both directions: a love of eye-smiting locations either found or fabricated, and an urge to plunge into characters’ minds at every moment.

These revelations come courtesy of Flicker Alley’s massive collection of nine of his late 1920s features, all beautifully restored by the dedicated team at Lobster Films. Poil de Carotte (1926), the earliest item in the box, shows a filmmaker utterly in command of the resources of the “mature silent cinema.”

Most of the films between that and Au bonheur des dames (1930) have been largely unknown and forgotten, and their revelation here is unlikely to add another masterpiece to his career log. But they’re very impressive for revealing the diversity and ambitions of mainstream French cinema of the 1920s. Moreover, Duvivier was prepared to carry a commitment to pictorial storytelling to striking extremes.

Eye candy, natural and artificial

Duvivier’s first film, Halcedama (1919; not in this collection), a French “Western,” made extensive use of the rugged terrain of the Corrèze region, “the savage heart of France,” according to a title. Extreme long shots (akin to those in Feuillade’s Tih Minh) let mountains and valleys dwarf the characters. The 1920s films tend to be melodramas, but they too exploit locations with expansive production values.

Before moving to cosmopolitan scenes, Le Tourbillon de Paris (1928)’s opening scenes give off a palpable sense of cold in their bleak display of a man struggling through the snow in Tignes, in the French Alps. The same regional realism is present in La Divine Croisière (1929), shot on location in several coastal cities.

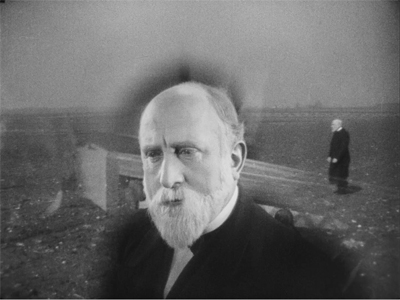

L’Agonie de Jérusalem: Revelation (1927) tells of an anarchist who rejects bourgeois comforts, including “paternal power,” and agitates for world revolution. When he’s blinded, he returns to the family home in Jerusalem. There he undergoes a conversion through identifying with Christ’s suffering and is miraculously cured. Duvivier took the production to Jerusalem, and the film features impressive scenes of the area, including the Wailing Wall and the Garden of Gethsemane.

For Maman Colibri (1930), Duvivier’s heroine, a woman who leaves her husband for a soldier young enough to be her son, follows him to his post in Algeria. The film exploits both desert landscapes and the sumptuous gardens of the Villa Arthur in Algiers. Closer to home, but still carrying the whiff of the picturesque, was Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans (1927), a comedy about rivalry between brewers. The film begins with a montage of Belgian cities and their landmarks, culminating in a documentary montage of Brussels. The film is bookended by a double wedding at the city’s splendid Grand Place.

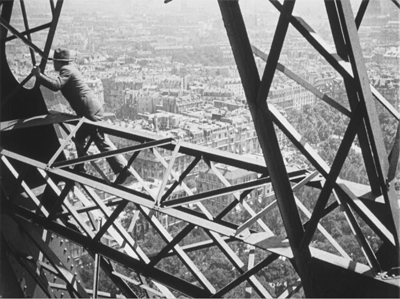

Probably the location shooting that will most attract a viewer today is the climactic sequence of Duvivier’s parody of Feuillade serials, Le Mystère de la Tour Eiffel (1927). It consists of a long chase up the girders of the tower, with actors scrambling after one another in vertigo-inducing shots.

As with Tih Minh, you have to marvel at the acrobatic skill and sheer guts of the performers.

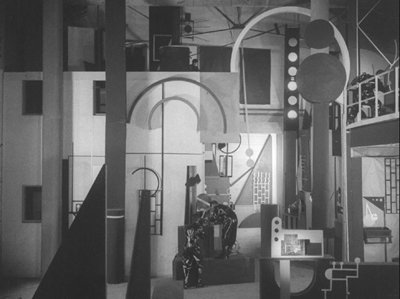

Duvivier also took advantage of the resources of well-endowed French studios, which had yielded impressive set design in Gance’s Napoleon (1927), L’Herbier’s L’Argent (1928), and Dreyer’s Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928). Le Tourbillon de Paris, tracing the return of a stage diva to the city she loves, shows her reentry into the haute monde in a huge nightclub scene. This is later matched by her triumph in before a theatre audience.

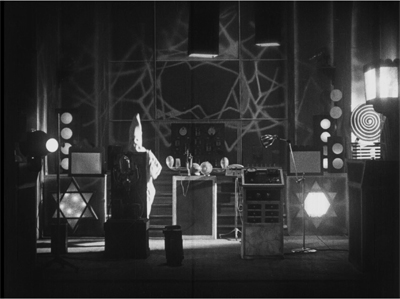

More stylized sets, in a comic vein, characterize the Antenna gang in Mystère de la Tour Eiffel. They use , the Tower to transmit coded messages to their agents. The gang headquarters may be a down-market parody of Léger’s modernist sets of L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1924).

Probably the most famous achievement of Duvivier’s set design is the staggering department-store set in Au Bonheur des Dames, Zola’s story of big business crushing local shops. Sweeping tracking and crane shots enhance the scale of Au Bonheur des Dames, modeled on the Galeries Lafayette (where a few shots were taken as well). The film contrasts the vista of the main shopping area with the cramped store of the fabric merchant Baudu.

The same difference emerges in the broad layout of the office of store’s boss Mouret and Baudu’s pinched apartment, built as a complete set of rooms.

Yet the sets can be less ostentatious and still powerfully functional. The simple, geometric grids and figure placements of the investiture scene in La Vie miraculeuse de Thérèse Martin (1929) gather force through their precise articulation of the stages of the heroine’s acceptance into the sisterhood.

In this twenty-minute sequence, details of gesture and position exude respect for the rigors of ritual and the sincerity of the girl. Duvivier’s calm precision reminds me of scenes in Bresson’s Anges du péché. At the same time, the impersonality of the ceremony is heightened by cutaways to Thérèse’s father, at once pious and regretful; with her novitiate, he will die alone. For him, Duvivier adds Impressionist flourishes to emphasize that the grille shuts him off from her.

Such scenes create a sort of “intimate spectacle” that goes beyond sheer scale.

In a fine crowd scene in La Divine Croisière, Duvivier deploys expressive detail within a mass of people. The predatory capitalist Kerjean has ordered a defective ship to sail, and the townsfolk fear that it has been lost. Simone, a courageous young woman, calls a meeting in which she asks them to cease mourning and set out to look for the sailors. In a brief montage reminiscent of the cream-separator sequence in Eisenstein’s Old and New, close-ups show the villagers gathering hope under Simone’s visionary appeal.

With this sort of intimacy, however, we move close to the second pictorial strategy that characterizes Duvivier and many of his peers: picturing the workings of the mind.

Getting inside

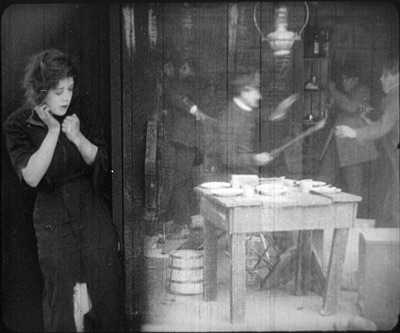

Kristin has pointed out that the 1910s were an era when many filmmakers wanted to go beyond simply creating a coherent story by adding expressive dimensions to the action. Many American films of the period try to illustrate characters’ thoughts, chiefly through flashbacks. There were more elaborate experiments as well, with attempts to portray dreams, hallucinations, and even alternative courses of action. (Some examples here.) In The Gangsters and the Girl (1914), a young woman imagines two consequences of a robbery.

Halcedama had, like many other French films, incorporated simple subjective techniques like these. The looming figure of the protagonist’s dead father interrupts several scenes, and one scene multiplies the presence of the man the protagonist has come to kill.

The early 1920s saw French filmmakers eagerly exploring other resources. Duvivier’s films are much of their time in their inclusion of wide-angle shots with big foregrounds, a great range of camera angles, freely moving camerawork (including crane shots), heavy use of superimposition and dissolves, and a multiplication of cuts, often very fast-paced.

Abel Gance’s La Roue (1922) and Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidèle (1923) crystallized these possibilities, and other filmmakers felt free to flaunt pictorial display. Many of these devices were put in the service of enhanced subjectivity.

In scene after scene, Duvivier dwells on the moment by plunging into characters’ reactions to the scene, given not through dialogue but through imagery. One of his favorite devices is the superimposition–not as a single item, as in The Gangsters and the Girl, but as a flurry of images melting into one another, suggesting a stream of consciousness. In L’Agonie de Jérusalem, Alice recalls the childhood she shared with Jean, as images rolling along a road.

The heroine of Le Tourbillon de Paris is dazzled by the array of jewels and dresses her husband offers her, and the heroine of Maman Colibri is captivated by her dance partner.

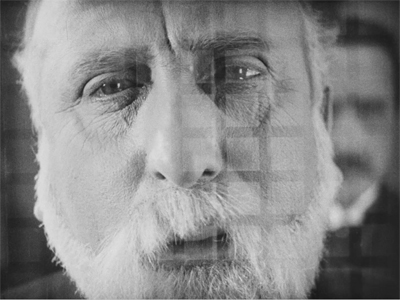

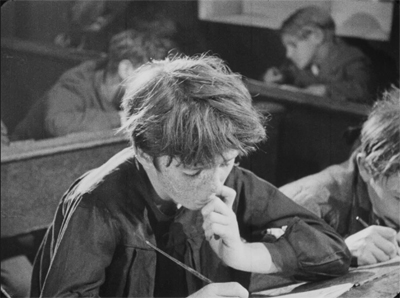

Poil de Carotte is a virtual anthology of ways of conveying mental states. This tale of child abuse probes the fear and despair François feels by being trapped in a family full of hate. The opening uses superimpositions of family members to show how it’s painful for him to write an essay about them.

His cruel mother haunts his dreams, and her attacks on him are given in distorted imagery.

As he rigs up a noose with which to hang himself, we get a rapid montage, in superimposition, of memories of ill treatment.

Nearly every film is packed with these inserted passages, which seek to deepen the drama without use of intertitles. Today they look old-fashioned, even though our films continue to use them. Back then they may have become a bit tiresome. Serge Bromberg’s text for the Flicker Alley booklet quotes a 1930 review:

Why does Julien Duvivier sometimes insist on techniques that seem obsolete today? Overprints [superimpositions] and special lenses no longer surprise us.

When they work best, I think, it’s because they find fresh material that allows them to unexpectedly expand the moment of a scene. For example, François’s father is not so much cruel as indifferent to the boy. His gradual realization that the mother is working the boy like a dog is given two ways. First, a multiple-image shot shows several versions of his son busy in the garden.

Then a series of dissolves following the father’s advance to the camera shows the sheaves now sprung up in profusion–all as a result of the boy’s labor.

Still, Duvivier was able to probe minds without such devices. The village meeting in La Divine Croisière, mentioned above, is an example. So too is a little bit of byplay in Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans.

Albert, a Parisian, is working in a Brussels brewery and has fallen in love with the boss’s daughter Suzanne. He leaves a corsage on her desk while she’s out. Seraphin, her shady fiancé, has found it there and, when she returns, offers it to her as his own gift. When Albert returns and finds her wearing it, he assumes that he’s won her affection–until he realizes Seraphin’s ploy. Duvivier could have played this out in a series of superimpositions in which Albert imagines her finding it, thinking of him, and wearing it for his sake. Instead, it’s left to the actors in a simple two-shot.

Albert sees her caress the corsage and he’s pleased. But then she says Seraphin gave it to her. There’s no dialogue title. She turns her head to the left to indicate he’s outside.

Albert starts to claim credit, but thinks the better of it and turns away. She notices and asks if he gave it to her.

He doesn’t admit it, but she realizes the truth.

As she ponders Seraphin’s deceit, Albert understands. He approaches, but she wards him off, still believing she must marry her fiancé.

Admittedly, this little pas de deux takes place after a dialogue in which Albert imagines all the slights he’s suffered as an outsider to the company, and before a lyrical passage in which he conjures up finding a flower in a lake. Duvivier couldn’t resist expanding the situation through his usual means. But the understated playing of the pair, without any verbal explanation, shows that he didn’t always need flashy visualizations to evoke characters’ changing reactions to a situation.

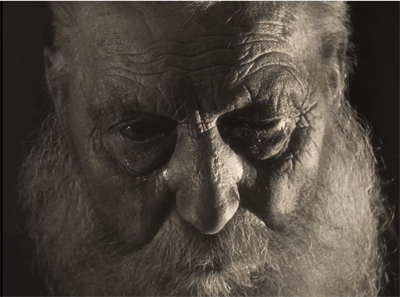

Duvivier remained active until his death in 1967, racking up an astonishing seventy-one features. There are plenty I have yet to see, but I’ll just signal some landmarks. Although he has remained most famous for his two Poetic Realist achievements, La Belle équipe (1936) and Pépé le Moko (1937), his accomplishments were more wide-ranging. Allô Berlin? Ici Paris! (1932) is a charming early sound comedy, and Un Carnet de bal (1937) and La Fin du jour (1939) won acclaim around the world. In Reinventing Hollywood I called attention to his significant American work: Lydia (1941), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Flesh and Fantasy (1943). His powerful Simenon adaptation Panique (1946) is admirable, as are the lighter-hearted Sous le ciel de Paris (1951) and La Fête à Henriette (1952). Marie-Octobre (1959) is an interesting experiment in the three unities. And his later policiers have their supporters, especially Voici les temps des assassins (1956). Attacked by the Nouvelle Vague as a fossilized academic, he has reemerged as a robust example of the enduring force of French film tradition. The Lobster/Flicker Alley box confirms him as a sturdy storyteller and an ambitious pictorialist.

Halcedama is available on the Cinémathèque Française website, among many other discoveries. Gance’s broadside, “Le Temps de l’image est venu!” is in L’Art cinématographique II, ed. Léon Pierre-Quint, Abel Gance, Lionel Landry, and Germaine Dulac (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1927), 83-102. It is available in an Arno Press reprint (New York, 1970).

The best book on French silent film is Richard Abel’s magnificent, encyclopedic French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915-1929. A very complete account of Impressionist cinema is in Noureddine Ghali, L’Avant-garde Cinématographique en France dans les années vingt: Idées, conceptions, théories (Paris: Experimental, 1995). Kristin’s argument about the 1910s is set forth in “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85.

Kristin picked Au Bonheur des dames as one of the best films of 1930. I discuss Lydia in a Criterion Channel installment, teased here. French Impressionism has remained a powerful, if usually indirect, influence on modern directors–for example, Scorsese.

Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans (1927).

Thrills and melodrama from the 1910s

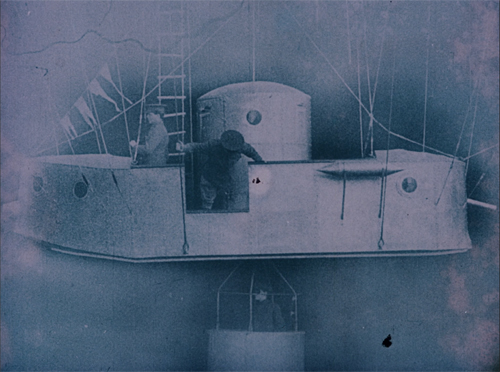

Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate (1915).

DB here:

Two new DVD releases remind us how 1910s filmmakers, unconstrained by realism, used the newish medium of film as a vehicle of charming, sometimes silly fantasy. One is the virtually unknown 1915 Italian feature Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate; the other is the famous but little-seen 1919 serial adventure Tih-Minh, by Louis Feuillade. The Filibus disc also contains a 1916 Italian feature Signori giurati… (“Gentlemen of the Jury,” here The Jury Decided). None seems to me a masterwork, but all are enjoyable and have something to teach us about the almost mad ambitions of an era discovering the power of long-form cinematic storytelling.

Lady with an airship

One thread over the life of this blog has been my nagging claim that the 1910s have not been widely recognized as the lively, innovative years they were. Yes, there was Griffith and Chaplin, but after that people tend to move on to rhapsodize about the glories of 1920s Europe and Hollywood. Of course many viewers appreciate the early work of Mary Pickford, William S. Hart, Buster Keaton, and Doug Fairbanks, and there are fans of great European directors like Sjöström and Feuillade, but even these luminaries are chiefly known for only a film or two.

Many scholars have labored loyally to bring to light major figures like Lois Weber and Albert Capellani, but these revelations remain niche tastes. Kristin and I have done our bit on the blog, in many entries and in the video lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” That suggests that today’s film industries, film culture, and artistic options have their sources in this era that, in retrospect, teems with creative possibilities.

The sheer imaginative variety of this output is brought home to me virtually every time I go back to see something recently discovered. My extended stay at the Library of Congress Kluge Center back in early 2016 was a smack on my head. In America, while filmmakers were elaborating the “continuity” system of storytelling (still with us), they were also pursuing side paths and fresh possibilities. (To check, start with “Anybody but Griffith” and move to later entries.) My discoveries complemented my years of visiting European archives to investigate both major auteurs and little-known films. (See the category “tableau staging.”) Now these releases, courtesy of Gaumont (Tih-Minh) and the cooperative efforts of Amsterdam’s Eye Filmmuseum, Milestone Film and Video, and Kino Lorber (Filibus) offer some new angles on the period.

Filibus centers on a supervillain who, unlike Fantômas or Dr. Gar el-Hama, is a woman. Like them, she’s a master of disguise, appearing as a genteel lady but also a suave gentleman and a sleek masked marauder. She steals jewelry through the usual methods: casing a household, sizing up the spoils, and confounding the authorities. What sets her apart is that she travels in a midsize airship that allows her to move swiftly from place to place and lower herself in a gondola to the numerous balconies that give access to the treasures.

She’s also adept at outsmarting the detective Kutt-Hendy. Exploiting the current public fascination with pseudo-scientific detection, the film shows her capturing his fingerprints on a rubber glove, and then leaving them at the scene of the crime. But she has old-fashioned tools as well, including a mysterious knockout scent.

Capably if unspectacularly directed by Mario Roncoroni, the scenes are mounted in straightforward ways for the period. Cutting, as you’d expect, consists largely of linking scenes or occasionally enlarging a detail we need to see, such as a camera inside the eye of a cat statue.

Within dialogues, simple axial cuts give us access to actors’ expressions. Sometimes Rondoroni moves a figure closer to the camera without motivation, simply to show us things more clearly, before the figure then retreats a couple of steps.

This is an anachronistic device, common in much earlier films. Most directors of the period motivated such movements by having something in the foreground that would draw the actor nearer to the camera.

The preposterousness of it all is well-recognized by everyone concerned, I think. The most impressive set, a parlor boasting Egyptomania galore along with the supposedly ancient but highly inauthentic cat sculpture, gets a good workout during the crime and the investigation. What remains, though, is Filibus’ unique transport system that allows her to bypass all the driving down roads and clambering up building facades we get in Feuillade. A blimp and a basket do the trick, leaving Filibus to sail off to her next conquest.

The film was noted as over-the-top in its own day. One critic wrote: “Great drama of adventure? Say rather a great cinematic mess of adventures. . . .” Evidently the tackiness of the special effects was evident as well. But we’re lucky to have it as one more document of the sometimes overstrained efforts to pack fresh sensations into the still-emerging format of the feature film.

Opium and murder

Signori giorati… is more orthodox and, I think, more satisfying as a story. A classic salon melodrama with plenty of diva posturing, it shows the decadence of the very rich brought to account. The adventuress Julienne (originally Lina) Santiago has seduced Dr. Nancey into setting up a plush opium parlor. Every night, the rich come to the “House of Forgetfulnesss,” where Julienne and the doctor blithely pick their pockets. When the police get interested, Julienne betrays Nancey and bolts, later to take up with one of their clients, the Marquis de Vallier. He resolves to marry her and brings her home to meet his daughter Helène (Valeria Creti, aka Falibus) and her husband. A deadly intrigue begins.

Signori giorati… shows the pluralism of visual expression of the period. While depth staging isn’t much developed here, the vast opium-den set carries the action far into the distance, where Julienne, masked, awaits the Marquis (above). Later, lurking in the reeds, Julienne stalks Helène’s husband.

Courtroom scenes in 1910s films are surprisingly varied, and director Giuseppe Giusti offers an unusual array of angles on the action.

A split-frame flashback illustrates courtroom testimony.

None of these moments is extraordinary for the period, but they nicely exemplify visual strategies becoming normalized in European cinema. Likewise, the somewhat awkward linkage between the first section around the opium den and the second on the Vallier estate show the need to tighten up the overall arc of the narrative–a problem European films would face for some years.

An unusual feature of the disc is the inclusion of five short films from the Amsterdam premiere of Filibus in 1918. This was made possible by the Eye Filmuseum’s splendid collection of early films from around the world shown in the Netherlands by the distributor Jean DeSmet. There’s also a brief short giving background to that collection.

From Vietnam to the Riviera

Tih-Minh (1919) followed in the wake of Louis Feuillade’s successful serials Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), Judex (1917), and La Nouvelle mission de Judex (1918). Released in installments from February to April 1919, Tih-Minh followed an important Feuillade feature, Vendémiaire, released in January. Throughout the same years Feuillade signed dozens of shorter comedies and dramas. Not only was he an efficient director on a scale we can hardly imagine today, but he had a powerful incentive: Gaumont gave its top directors a percentage of a film’s revenues, and Feuillade’s salary made him wealthy.

The plot revolves around a treasure supposedly hidden in Indochina. But where? A Sanskrit book contains notes, in code, about its whereabouts. The explorer Jacques d’Athys has unwittingly acquired it during his last expedition. Learning this, former German spies Kistna the “Asiatic” and Dr. Gilson recruit the hapless Marquis Dolores (above) and target Jacques’ villa in Nice. Jacques has also brought back the delicate young woman Tih-Minh (also above), daughter of a French colonist murdered, it’s revealed, by Gilson (né Marx!). The complications around the coded message lead the gang to a series of raids on the household, usually involving efforts to kidnap Tih-Minh. The efforts are resisted by our heroes–Jacques, his loyal servant Placide, the maid Rosette, and the British diplomat Sir Francis Gray.

Tih-Minh has an essentially comic structure. Unlike Fantômas and the Vampires, this gang can’t catch a break. Nearly every attempt they make, involving poisons, amnesia serum, hypnosis, and accomplices smuggled into the household, is thwarted, quickly or eventually. The ineptitude of Kistna’s gang is nearly matched by the passivity of Jacques’ team. They seem to wait around for the next assault, and when they prepare a trap, it usually fails. Only Placide, consistently suspicious, mounts countermeasures. Just when you wonder whether Nice has a police force, Jacques announces they can handle things best themselves.

Tih-Minh, a favorite of mine over the years, cracked a bit on this go-round. For the first time I found the opening installments dilatory and meandering. Feuillade is counting on our enjoying the company of these comfortably rich people and their rounds of coffee breaks, walks on the estate, and flower-picking in dazzling sunlight. And it is a kind of Bower of Bliss, which will eventually host three weddings.

Unlike the earlier serials, where he relies on composition in depth, here he favors lateral layouts. It’s as if the speed of the production pressed him toward lining up characters talking to one another in long-shot and medium-shot. Yet as I wrote about here, he varies the placement of heads in graceful waves.

These framings look forward to his later work’s “long-take” setups, broken only by dialogue titles.

The pacing and flashy visual invention pick up considerably in the later installments, when Feuillade hurls his cast through the magnificent landscapes of the Riviera. During the war, Gaumont moved substantial portions of production to the Victorine studios in Nice. Installing himself there in 1918, Feuillade takes advantage of everything in the neighborhood. You can sense his delight in finding ways to use the ocean front, rocky terrain, gorges, mountain crags, decrepit hilltop castles, luxurious estates, and hotel rooftops.

Pursuits across these forbidding spaces are a powerful attraction in their own right, and the second half of the film does not disappoint. For some shots the camera seems a mile away from the tiny human figures.

The actors accordingly give their all. Placide’s physical comedy is matched by his willingness to be beaten up, dropped from a great height, or folded up into a trunk lashed to an automobile roof. Flung into the ocean, he laughs it off.

Heroes and villains alike are willing to clamber around scaffolding and window ledges and crawl down the face of a mountain.

Mary Harald as Tih-Minh, apparently a wilting flower, seems game for anything as well.

We’re so used to stunt doubles for action scenes that we forget that long ago actors were athletes.

The vertiginous spaces and the bravado of the performers come to a climax when the chase moves to a zipline carrying rock from a quarry down into a valley. The villains dive into one of the gondolas and ride off to infinity. Undaunted, our heroes follow.

These shots, a rebuke to the cheesiness of Falibus‘ special effects, are alone worth the price of a DVD. And you thought Preminger treated actors roughly?

One more aspect of this release makes it a must-have for admirers of early film. It is one of the finest digital transfers of a silent film to disc that I have ever seen. Derived from a pristine negative, it is a perfect illustration of what 1910s cinema looked like at its best. (Thankfully, it is not tinted. Tinted versions often smudge original photographic detail.) We always knew that there was more on a 35mm orthochromatic film than we could see. Now we see it.

Gaumont’s disc of Tih-Minh is coded for all regions and contains optional English subtitles. Unless a US distributor picks it up, it will be available only at places like Fnac and Amazon.fr. University libraries and film departments should be able to get copies easily. Beware the bootleg version of the Belgian print (the source for the restoration’s intertitles) offered on eBay and elsewhere.

The Italian cinema of the 1910s was no less stylistically innovative than that of other nations, but the films haven’t achieved canonical status. Except for big, influential productions like Cabiria (1914), the output of this major industry has been overlooked, largely for reasons of availability. A breakthrough came with the superb collection, Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader, ed. Giorgio Bertellini (New Barnet: Libbey, 2013). My amateur forays into the area have yielded some nifty items, such as Fabiola (1918) and Maman Poupée (1919) and Il Maschera e il Volto (1919), as well as many I hope to share in the future.

Critical response to Filibus is sampled in Vittorio Martinelli, Il cinema muto italiano 1915, part 1: I film della grande guerra (Rome: Bianco e Nero, 1992), 190-192.

The standard study of Feuillade is Francis Lacassin’s magisterial Louis Feuillade: Maître des lions et des Vampires (Pairs: Bordas, 1995). (It’s a real bargain here.) I survey Feuillade’s staging strategies in Chapter 2 of Figures Traced in Light. A more general account of silent film staging in depth is in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Not incidentally, the Eye Filmmuseum offers a rich array of films from many periods, including the 1910s, for free viewing online.

Tih-Minh (1919).

How the world ended in 1916

The End of the World (1916).

DB here:

The pull-quote might be “Gripping entertainment and a vivid introduction to storytelling strategies characteristic of Danish silent cinema!” (Too long for a poster, though.) It appears in my essay on a remarkable silent film you may not know. I bet you’d like it.

Danish cinema has gripped my interest for about fifty years. Like most cinéphiles, I started with Dreyer, moved on to Christensen, and then just tried to keep up with trends leading to Scherfig, Vinterberg, Winding Refn, Anders Thomas Jensen, and Dogme. There always seemed to be a new comedy or noir or psychological drama or just weird-ass experiment to keep my loyalty (most recently, the well-crafted Another Round).

One of our first blog entries, on 20 October 2006, was devoted to an anthology on the great film company Nordisk. Soon I was chattering about von Trier’s editing in The Boss of It All and surveying a big batch of recent releases.

Now this national cinema’s silent-era history is coming steadily online. The Danes are too modest to brag about the enormous accomplishment of making so many beautifully restored classics available for anyone to watch. But here they are, accompanied by thematic essays from critics and historians.

Like other Little Cinemas That Could (Hong Kong, Taiwan. Iran), Denmark attracts me because it has shown what can be done a lot of imagination on smallish budgets. Or sometimes, biggish budgets. That’s an impulse that emerged in the 1910s when Nordisk was struggling to keep a foothold in the international market during the Great War. One result was a pair of remarkable spectacles.

A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet, 1918) is a massive, nutty plea for peace and international—make that interplanetary—understanding. The Martians are more or less like us, except they don’t kill other creatures, which leaves them time to assemble in carefully picturesque crowds and invest in ambitious infrastructure projects.

The other big Nordisk production was The End of the World (Verdens Undergang, 1916). A comet is plunging toward earth. Can we avoid collision? Or at least survive?

All the conventions of the cosmic disaster movie (Armageddon, Independence Day, 2012) are already in place. We have the innocent family, the corrupt capitalist squeezing money out of catastrophe, the scientists trying to calm the public, and of course the separated lovers who must find one another in the midst of chaos.

The special effects range from passable to truly impressive, as in the model of the village under fiery bombardment, surmounting today’s entry. The comet’s approach is cleverly suggested as a blip in the sky, and the shots of the heroine’s drowned neighborhood are splendid.

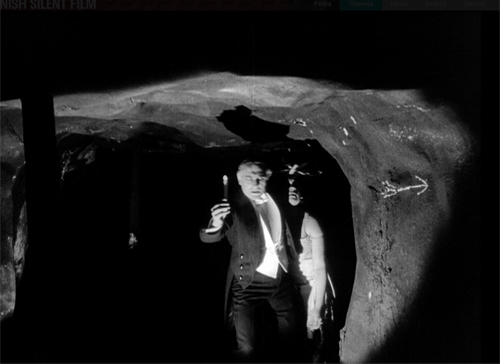

Just as remarkable are other technical achievements. The lighting in the underground passages of the capitalist’s mansion, with its Caligariesque steps, could teach the Germans a few tricks, and the miners’ fierce assault on the plutocrats is cut with rowdy, immersive vigor.

August Blom had made his reputation with Asta Nielsen dramas and another would-be blockbuster (Atlantis, 1913). He’s often considered a stolid director, but The End of the World seems to me an underrated achievement. Dismissed by many critics as over-produced, its ambitious spectacle is probably more to our current taste for overwhelming scale. For us, it seems, too much is never enough.

So I recommend to your attention this remarkable movie. As usual, I throw in a case for the 1910s as one of the great and glorious eras of film history. You can handily sample further evidence in the film links alongside the essay.

Thanks to Thomas Christensen and his colleagues at the Danish Film Archive. It was fun!

There’s always more to say about the Danes. Outside our blog entries, I’ve written about Nordisk and the “tableau aesthetic” and on early Dreyer in another essay on the Danish Film Institute site.

The End of the World (1916).