Archive for May 2022

Streaming media: All you can eat, until it eats you

DB here:

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas remarked: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

I wrote the preceding paragraph two years ago, and the Covid outbreak and enhanced technology have made the split between theatrical distribution and streaming distribution even sharper. (And as the Movie Brats predicted, multiplexes are raising ticket prices.) A crisis point was reached last month when Netflix glumly reported that instead of adding 2.5 million customers as it had expected, it lost some 200,000. Worse, the firm announced a likely loss of 2 million more in the next quarter. The news led Netflix stock to fall by over 30%, wiping out over $45 billion in value.

This stunning decline, coupled with Warner Bros. Discovery’s decision to cut the recently launched CNN+, sent shock waves through the industry. Stock values dropped for Disney, Warners, Paramount, and Roku as well, even though some had strong subscription growth. At the moment, disillusion seems to be settling in. A Wall Street analyst has noted:

We think the industry is facing a point of no return in which the economics of the old models look increasingly frail while the potential of the brave new world now appears overly hyped.

Discussions of mergers, acquisitions, and big company restructuring are ongoing, with layoffs already starting.

As researchers, we at The Blog try to see past current convulsions to larger patterns. But it seems plausible that we are approaching some significant changes. Without trying to predict much, and being no expert on streaming tech, I still thought I’d try to think through some ideas about the state of streaming and its historical significance.

An interim report

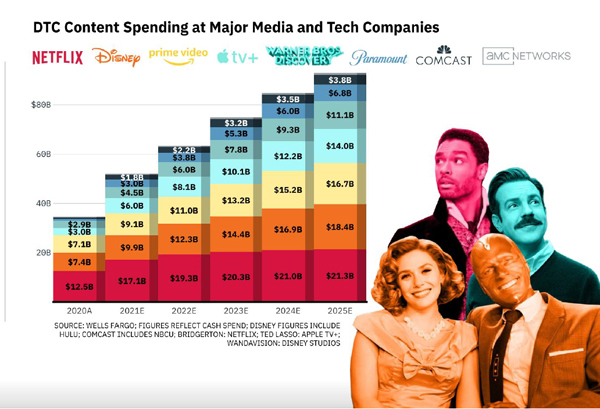

The Future of Content, Variety Intelligence Platform April 2022, p. 10.

Best to start with some basic information. Here’s what I came up with, all subject to correction and nuancing.

Streaming is now firmly established as a distribution/exhibition platform. It’s now the focus of all major US media conglomerates and it’s a market force every independent producer and company must reckon with. Broadcast television is waning. Viewership is declining, and this year saw a ten-year low in the number of pilot shows ordered by the networks. Cable subscriptions are likewise plummeting. Over the last ten years, cable channels lost 30-50% of viewers. Only the Discovery channel managed to grow, and live sports (e.g., ESPN) hung on, though damaged by the pandemic. Globally, streaming is growing rapidly, with both Hollywood majors and national and regional media firms plunging in.

Theatrical film, severely curtailed by the pandemic, is staggering. In nearly every country of the world, 2021 attendance was half or less that of 2017-2019. Studios are now releasing far fewer features, even in the crowded summer months. About 1000 theatre locations have not reopened since early 2020. Los Angeles has lost the Arclight and Pacific Theatres chains and the Landmark Pico theatre. In my home town a five-screen second-run house shuttered during the pandemic, and a six-screen multiplex is rumored to close soon.

As Lucas and Spielberg foresaw, the films that fill multiplexes are blockbuster franchises. So far this year, Spider-Man: No Way Home and Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness have done robust business, and exhibitors confidently expect big turnout for Top Gun: Maverick and Jurassic World Dominion. The surprise success of Everything Everywhere All at Once ($47 million box office) doesn’t mitigate the bleak prospects for most offbeat theatrical fare. Prestige films, romantic comedies, arthouse films, and many genre pictures can’t usually yield big enough returns, and the aftermarket–cable, DVD, and other ancillary outlets–which helped support them in the past scarcely survives.

Which leaves streaming as a primary source of filmed entertainment. At least 86% of US households access streaming services, either by subscription (SVOD) or as ad-supported services. The result is an immense amount of choice. You can browse studio libraries, imports, straight-to-streaming features (e.g., the latest Pixar releases) and series (e.g., Inventing Anna, Tokyo Vice).

Except for Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Apple+, the major streaming services are aligned with US entertainment conglomerates. Indeed, streaming made Netflix and Amazon entertainment behemoths, as attested by recent Academy Awards and Emmys.

Exact figures fluctuate, but the principal subscription streamers vary enormously in scale. At the beginning of this year, pre-meltdown, Netflix declared a global subscription base of about 220 million, with Disney+ at 196 million. Paramount claimed about 56 million (incuding Showtime and other offshoots), Discovery 22 million, and Peacock 24.5 million, including both paid and free. According to Amazon, over 200 million Prime members streamed material in 2021. As of March, Apple+ was estimated to have 25 million paid subscribers, with about twice that number benefiting from access via promotions (e.g., purchase of Apple hardware).

The simultaneous theatrical/streaming release (Dune, Wonder Woman 1984) is becoming rare as audiences return to theatres, but it remains an option (e.g., Firestarter). More common is a strategic delay far less than the usual ninety-day window that was common before the pandemic. The Batman opened in multiplexes on 4 March and was streaming 18 April. Universal and Paramount are prepared to send a feature online 17 days after theatrical release.

Fickle audiences and fluctuating “content” create churn. As a monthly subscription transaction, paid streaming lets consumers depart at will. Canceling cable subscriptions was difficult due to long-term contracts and obstreperous bureaucracy. Unsubscribing to Netflix or Apple+ is a lot easier. In addition, cable programming had a considerable stability, with long seasons and evergreen attractions. Studios signed extensive licenses for films and series, since cable was a perpetual money machine. Moreover, a movie might be available on several cable outlets. Now, however, the streaming industry faces audience churn.

Defections are common, especially among the young. An April survey found that nearly a third of Gen X subscribers and nearly half of Millennial and Gen Z subscribers have both added and dropped at least one streaming service in the last six months. Overall, nearly a third of subscribers say they have canceled at least one service in the same period. Web-experienced viewers are adept at hopping onto and off the latest thing.

Churn is accentuated by the exclusivity of the new media oligopoly. As the majors discovered the money to be made, they regained control of their library licenses. Netflix had The Office, its most popular attraction, until Warners took it back in 2019–soon after Netflix had renewed it for $100 million. The turnover is ongoing: this month Netflix lost Top Gun, the Ninja Turtles, the Muppets, Marvel TV series, and the first six seasons of Downton Abbey. The majors have gradually reasserted the exclusivity of their product.

As competition has intensified, streamers have been forced to acquire their own programming, both films and series. The pool must be refreshed to retain current subscribers and attract new ones. The problem is that once the new material has run its course, viewer loyalty can wane. This is especially true when the streamer dumps a full season of a series for bingeing: it encourages newcomers to sign up briefly and then defect. Disney has executed a powerful balancing act between legacy material and new offerings (Pixar features, Marvel spinoffs) that keep audiences faithful.

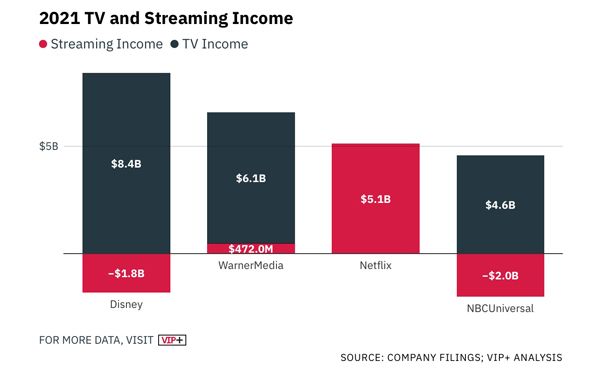

Streaming is not yet profitable. Broadcast and cable television are far more lucrative because they gain revenue from advertising and fees. Disney and Universal each lost about$2 billion on streaming in 2021.

Hence the concern over Netflix’s April report of decline in subscriptions. Streaming is its core business. A loss of $2 billion for the Disney conglomerate (parks, cruises, ABC TV, etc.) amounts to a rounding error. The majors’ deep pockets can sustain streaming enterprises for some time, but Netflix is far more vulnerable.

The streaming services are investing huge amounts in new “content.” The major providers are estimated to spend $50 billion acquiring projects this year. Producers are in a powerful position to demand big budgets to outmatch the competition. The costs are exacerbated by the high demands of talent, who now expect to be paid largely up front, since there is little opportunity for the deferred fees and back-end deals that depend on ancillary revenue.

No wonder then that several services have raised subscription rates. More drastically, in its current crisis Netflix has announced plans to offer an ad-supported tier of the sort already provided by Universal/NBC’s Peacock. Other services, Disney included, will probably shift to a similar option, especially since there is some evidence indicating that consumers will accept commercial interruptions in exchange for lower fees. Netflix also plans to control password-sharing, which helped it grow recognition but in the face of intense competition depletes its audience. It may be harder to combat the use of virtual private networks, aka VPNs, which allow roundabout access to region-based offerings.

One monetization strategy seems to be the rebirth of windows. Once a high-demand film is released to streaming, the service can add an upcharge for accessing it. Blockbusters like The Batman and the new Spider-Man trilogy were launched online with an extra fee for initial viewing. Over time, the prices fell gradually, just as in the old first-run/ second-run days. Even classics can benefit from premium treatment: The Godfather is free on Paramount+, but a rental costs $3.99 on Amazon Prime and Apple+. Arthouse fare is even more privileged; I paid $19.99 to see Drive My Car in its online release, though now it’s free on HBO Max.

It’s still TV

Bill Amend, Foxtrot.

In the late 2000s, streaming video entertainment was the province of mostly smallish, scattered companies like Twitch, Pluto, and others. Netflix and YouTube also took the plunge. Hulu, a consortium of Fox, Universal, and Disney, represented the majors’ initial effort to explore the market. As download speeds improved, problems with buffering and latency were overcome by new streaming protocols.

Soon enough, a familiar cycle emerged. Tim Wu’s book The Master Switch shows that mass information technologies (telegraph, telephone, film, TV) tend to consolidate into oligopolies. Major companies buy or kill off the competition. This happened with streaming, as one by one the big players came to the foreground. Netflix had early-mover’s advantage, having pioneered the distribution of DVDs by mail, and Amazon had a massive customer base in place already. The studios had helped Blockbuster wipe out small video-store chains, which had demonstrated the existence of a massive market, then turned their attention to selling discs directly to consumers. In 2019 the big players began to consolidate control over the expanding streaming landscape.

By acquiring other services (e.g., Paramount’s buying Pluto) and assembling proprietary components already in hand (e.g., WarnerMedia’s repurposing HBO Go), the firms have come up with integrated platforms. Disney+ launched in 2019, Peacock and HBO Max in 2020. Discovery+ and Paramount+ appeared in 2021, and Amazon bought MGM earlier this year. Sony, while licensing its film releases to its counterparts, has focused on animation by picking up Crunchyroll, which will absorb Sony’s Funimation service.

It’s early in the game, and it will take time for the companies to reassemble libraries that have licenses yet to expire. Doubtless many titles will be available for premium rental on rival sites, since no company wants to leave money on the table. Still, it seems clear that a considerable siloing of “content” will enable firms to enhance their power over their intellectual property. From this standpoint, we can think of streaming as a new phase in the development of home video.

In the earlier entry, I argued that home video formats gave the consumer a great deal of freedom. Even cable promoted “appointment viewing,” but tape, and then DVD, allowed the consumer a lot of flexibility. You could buy or rent a movie and watch it when you pleased. You could copy it too. Convenience is always a plus in a consumer item, and home video added to it a welcome price point: renting a tape or disc was cheaper than buying a movie admission, and in discount bins you could find a DVD for a few bucks.

With physical media, movies became manipulable by the audience. Ripping a DVD yielded a file that could be remade. Mashups, Gifs, and other transformations were feasible. Video essays changed film studies, and satire, homages, and fan analyses filled the internet. You could play with your movies.

Streaming withdrew this flexibility but offered greater convenience. A platform combines the array of a video store (think of those tiled pages as display racks) with push-button access. You still have the option of time-shifting, and you can share home viewing with others. But there’s no longer a physical medium. You don’t own or rent the film as object; you have bought access to it as a display, and only when you’re online. (“Buying” a digital copy is no guarantee of possession, if the service loses its license to the title.)

For decades, movie exhibition was a service business. We paid for the experience. Briefly, between 1980 and 2020, films became consumer artifacts as well. Ordinary folk enjoyed the sense of possession shared by film collectors of earlier decades. But with the decline of discs, we are once more paying for the experience while the object lies elsewhere.

Because of Hollywood’s preternatural fear of piracy, turning the artifact back into a service is a way to secure intellectual property. Not that people will stop trying to make personal copies. It’s possible to record streaming transmission, but the majors are counting on several factors. Just as people became tired of piling up DVDs they probably won’t watch, they could tire of filling hard drives with rips.

A few hardcore headbangers will enjoy sticking it to the man, but most people will reckon if you already pay for streaming the movie, why copy it? Given customer inertia and the convenience of streaming, why bother to pirate a movie that’s probably on streaming somewhere, available whenever you want? The trouble and expense of ripping may be greater than simply signing up for another subscription service. There are certainly overseas markets for pirated streaming shows, but as the companies expand their platforms abroad, piracy may diminish.

In sum, streaming has become the next step in the majors’ reassertion of control over their IP. It surpasses the old video store’s inventory, offers the convenience of click-ordering and time-shifting, and retains the advantages of in-home consumption. All we relinquish is ownership of a copy. Now that SVOD services are generating new attractions, providing long-running series with spaced-out hour-long episodes, and exploiting advertising-supported tiers, we are getting a version of fully on-demand cable TV.

We can glimpse this prospect in the demand for bundling, or aggregation. Customers’ biggest complaint is that there’s too much choice. The 200 channels of maximal cable are dwarfed by the streaming torrent. Nielsen estimates that as of last February there were 817,000 unique program titles available. Hence the emergence of streaming MVPDs, the “multichannel video programming distributors.” They provide a mix of movies, broadcast network series, classic TV, sports, and cable news. The best example is YouTube Live, which charges $64.99 per month, far beyond most of its SVOD competitors and reminiscent of classic cable fees. Yet YouTube Live is the most popular MVPD.

Add to this the number of FAST outlets, free ad-supported streamers such as Pluto, Tubi, Roku, Freevee, et al. With MVPDs these already constitute about a third of streaming offerings. One survey found that 34% of US consumers would prefer a free streaming service with 12 minutes of ads per hour. Streaming is starting to look like. . . well, just good old TV. The free platforms approximate broadcast TV, and the paid ones are cable reborn.

It takes time to make a classic

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill (2007).

Streaming demands a constant flow of new material, compared with the relative stability of broadcast TV, so the problem has been how to release it all. Netflix made a splash by dumping entire seasons at once, encouraging bingeing and getting immediate buzz and uptake. Viewers came to expect the big gulp. One survey found that over half of viewers under sixty now want firms to provide all the episodes of a series at once. But this strategy can damage long-term subscriptions by encouraging churn.

It also makes the product forgettable. Most direct-to-streaming films have a short shelf life. Does anybody watch War Machine (2017) or Bird Box (2018) now? Most auteur efforts seem to me to have had little cultural impact, not even Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019, with a mild theatrical release as well) or Soderbergh’s The Laundromat (2019). They came and went fairly quickly. A rolled-out theatrical film had an afterlife, it could circulate through the culture in many ways, and it could find niche audiences. Could The Godfather (1972) have its standing today if it were released straight to SVOD? Are there now “classic” streaming features?

This applies to art films too, I suspect. The international festival circuit allowed films to trickle from the big events to national and regional festivals over months, so outstanding films could build critical response and whet audience interest. Eventually some would find commercial distribution city by city. The pandemic compressed that process as festivals began to allow remote viewing of their screened titles, sometimes to audiences outside the locality. Kino Lorber’s Kino Marquee plan, which allowed simultaneous online access to new releases across the country, was a creative effort to maximize a film’s reach. Sponsored by local theatres, the plan in effect yielded a quick nationwide release on a scale that couldn’t easily be matched in pre-Covid days. It’s hard to imagine, though, that L’Avventura (1960) would have its standing today if it had played so quickly throughout the country.

Producers are belatedly realizing that the slow rollout characteristic of classic film distribution had the advantage of building audience awareness. A theatrical trailer is targeted toward habitual moviegoers and word of mouth. Theatrical releases garner promotion and extensive critical coverage that last longer than a Twitter alert. Theatrical screening can make a film an event–not always successfully, but at least it offers a chance. At a 19 May Cannes panel, a Swiss distributor pointed out that theatrical releases do better on streaming than straight-to-streaming ones.

The rationale is partly financial, of course. Here is the new head of Warner Bros. Discovery David Zaslav:

When you open a movie in the theaters, it has a whole stream of monetization. But more importantly, it’s marketed and builds a brand. And so when it does go to a streaming service, there is a view that that has a higher quality that benefits the streaming service.

There’s also the fact that a film on the big screen has a force that even a home theatre display can’t match. Another executive notes: “The undivided attention you get from an audience in a theater is where franchises are born.”

Classics, too. Even if most people see most films on monitors and personal screens, there need to be places for the proper display of them–living museums of cinema, in archives and cinémathèques but also in multiplexes and art houses. If streaming is making films ephemeral, we need to hang on to screening situations that let films claim our full engagement. If cinema becomes more like opera, as Lucas and Spielberg prophesied, let’s all become patrons and devotees, even snobs. Let films ripen over the years in a shared cultural space. Then we may get future masterpieces. Or so we might hope.

Thanks to Erik Gunneson, Peter Sengstock, and Jeff Smith for information and ideas.

Thompson/Bordwell online books now available for free

DB here:

For some years we’ve offered digital books for sale via our site. These are either original works, like Pandora’s Digital Box and our Christopher Nolan study, or updatings of out-of-print publications like Planet Hong Kong and On the History of Film Style. Those have been available through purchase via PayPal.

I was never comfortable with using that service, but its ubiquity favored it. Now that its chieftain, billionaire Peter Thiel, is bankrolling Ohio Senate candidate J. D. Vance and other mega-MAGA figures, we see no reason to add to PayPal’s revenues, not even the few cents it receives from a purchase here.

So starting today, all the books formerly for sale are free to all. They sit in a stack on the right of this page. They are unlocked pdf files, and can be read or downloaded as you wish. Click on whatever interests you.

Thank you to all our readers who purchased some books in the past. We hope that making other titles easily available will attract you as well. Thanks as well to those educators who have asked students to use these in course work. If you haven’t acquired any of these so far, you’re welcome to pick them up!

Thanks as ever to our web tsarina Meg Hamel for setting up our online book sales originally, and for liberating them today.

P.S. 17 May 2022: Some readers have noted that Peter Thiel may no longer have an association with PayPal, as he sold his founding interest in the company in 2002. But he may still be one of several stockholders. Still, if we’re in error, we regret it and apologize. We don’t regret highlighting his deplorable political activities. And we’re glad to release the books.

How did “prestige horror” come about?

Trailer, The Northman (2022).

Kristin here:

Ever since last August I have been venturing into our local multiplexes to see movies. Fully vaccinated, twice boosterized, wearing a mask, and attending weekday matinees in the company of maybe four to ten other people, I have felt safe. It’s great to see movies on the big screen again, and I’ve seen nearly twenty, starting with Annette in August and not counting the five I saw at the Wisconsin Film Festival.

The latest was The Northman, on April 25, a Monday. I had seen the trailer for it three or four times before I realized that it was by Robert Eggers, director of The Witch, which I liked well enough, and of The Lighthouse, which I admire very much.

Before the film there was the usual flood of trailers, including ones for Nope, Men, and The Black Telephone. It struck me as I watched them that despite the fact that I am not particularly fond of the horror genre, there I was, waiting to see a horror film–at least I’m classifying it as such under the rather casual criteria I’m using here. And if you doubt it’s a horror film, I present you with a frame of the character identified in the credits as the He Witch, holding the mummified head of Heimar the Fool. (The story is based on an ancient Scandinavian myth, the same one whence Hamlet was derived. This may be the equivalent of the Yorick scene.)

Not only was I there to see a horror film, but I was looking forward to seeing two of the three such films previewed: Jordan Peele’s Nope and Alex Garland’s Men. (Apparently these succinct titles are designed to avoid even the faintest whiff of a spoiler.) Later, musing on that confluence of horror films coming out this spring, it occurred to me that all three of these directors had concentrated exclusively on the genre in the features they have made so far–three apiece, coincidentally. And while all three had had some degree of critical, popular, and/or financial success, none of the directors has so far moved into the world of franchise blockbusters. It’s so common these days for indie directors to be swept from the world of low-budget art-house filmmaking to to heady heights of franchise series that I suspect one or more of the three have received nibbles from the studios.

One or more may eventually succumb to the blandishments that have attracted such indie directors as Taika Waititi, Guillermo del Toro, and Chloe Zhao into the world of Hollywood blockbusters. For now, though, it’s remarkable to find three directors with such similar careers in many ways who have stuck to the modest genre that brought them success when they probably had other options. It’s so common these days for an aspiring filmmaker to break into the industry with a low-budget horror film that becomes a hit and then immediately to be helming an epic with a budget distinctly into nine figures. (For a list of superhero-film directors who started in horror, see here; for a more general one of indie directors who jumped to blockbusters, here.)

There’s a fourth director who belongs with this group. I haven’t yet seen a trailer for Ari Aster’s Disappointment Blvd., which is being kept under wraps but is due out this year. It is described as a comic horror film. Gamerant has the fullest information on it that I’ve found. Excerpts:

Following the tradition of his previous movies, Aster will serve as both writer and director of Disappointment Blvd. While the movie is shrouded in mystery and doesn’t have a trailer yet, it will be a decades-spanning horror-comedy about a famously successful entrepreneur. And if Hereditary and Midsommar are anything to go by, it will be a genre-bending horror-comedy at that. In conversation with UC Santa Barbara students, Aster described Disappointment Blvd. as a 4-hour long “nightmare comedy,” though whether he was joking about its length remains to be seen.

A24 will distribute Disappointment Blvd. as well as co-produce it with Square Pegs: Ari Aster and producer Lars Knudsen’s production company. Disappointment Blvd. began production in June last year and is set for release later this year, though no official date has been given yet.

There is speculation that the movie will have its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival due to take place from 17 to 28 May 2022. Fortunately, the festival announces its lineup on the 14th, so fans won’t have to wait long to find out.

Eggers, Peele, Garland, and Aster all unquestionably belong to a trend that has recently been given a name–in fact, two: “elevated horror” and “prestige horror.” Elevated horror as a concept began to gain currency after the release of Eggers’ first feature, The Witch, in 2015. I suspect that Garland’s Ex Machina, which came out in 2014, had something to do with that. Many would count it as science-fiction, but under my loose criteria here, it counts as horror–especially since Garland’s two subsequent films undeniably fall into the horror genre. Elevated horror, according to The Hollywood Reporter, is a treatment of films as quasi-art cinema, as well as a focus more on psychological dramas than gore.

I don’t care for the term “elevated horror,” since it could imply simply a ratcheting up of the level of horror included in the film. This is far from what these directors are doing, although The Northman has little interest in psychology and contains plenty of graphic dismemberment.

In recent years there has come to be a vituperative reaction against “elevated horror” among fans, who claim it implies that the rest of the genre is trivial, trash, whatever. I have no interest in the resulting debate, but google “elevated horror,” and you’ll find it.

The same basic debate simmers concerning the term “prestige horror,” with fans claiming that treating prestige as something new to horror films dismisses the many classics of the genre that have gained critical respect, awards, and status as classics. Yet The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby, Jaws, Children of Men, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and others have been and remain well-respected. They have, in fact, prestige, as do the films of this younger group of filmmakers who have stuck to the horror genre. But the classics just listed were directed by people who worked in a variety of genres and did not stick to horror. I’ll use “prestige horror” here, since it seems to me to accurately describe what distinguishes the work of these four directors and other films (e.g., A Quiet Place, Saint Maud) from more conventional mainstream horror films. The term basically, I think, is a suggestion of something more respectable emerging from an era in which “torture porn” seemed to dominate the genre.

This entry doesn’t aim to present an overview of prestige horror. I have simply been intrigued to see what these four filmmakers, who have made a body of work which could be considered the core of the current prestige-horror trend, have in common and how those commonalities have helped create this new perception of a trend within the larger genre.

My interest arises from the fact that within a short period these directors have each made multiple reasonably successful feature-length horror films that have attracted favorable attention from critics, film festivals, fans, and institutions dishing out awards.

The Films

Annilhilation

Here is a chronology of the four directors’ films, with information relevant to explaining their prestige status.

2014

EX MACHINA (Alex Garland) Dist. A24

Budget: $15,000,000

Worldwide Gross: $36,869,414

Rotten Tomatoes: 92% critics 86% audience (6 points difference)

2015

THE WITCH (Roger Eggers) Dist. A24

Budget: $4,000,000

Worldwide gross: $40,423,945

Rotten Tomatoes: 90% critics 59% audience (31 points difference)

2016

None

2017

GET OUT (Jordan Peele) Prod. Blumhouse and Dist. Universal

Budget $4,500,000

Worldwide gross $255,407,969

Rotten Tomatoes: 98% critics 86% audience (12 points difference)

2018

ANNIHILATION (Alex Garland) Prod. Skydance Media and Dist. Paramount

Budget: $40,000,000

Worldwide gross: $43,070,915

Rotten Tomatoes: 88% critics 66% audience (22 points difference)

HEREDITARY (Ari Aster) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: $10,000,000

Worldwide gross $80,200,936

Rotten Tomatoes: 89% critics 68% audience (21 points difference)

2019

THE LIGHTHOUSE (Robert Eggers) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: est. $11,000,000

Worldwide BO $18,177,614

Rotten Tomatoes: 90% critics 72% audience (18 points difference)

MIDSOMMAR (Ari Aster) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: $9,000,000

Worldwide gross: $47,967,636

Rotten Tomatoes: 83% critics 63% audience (20 points difference)

US (Jordan Peele) Prod. Monkeypaw Productions and Dist. Universal

Budget $20,000,000

Worldwide gross $255,184,580

Rotten Tomatoes: 93% on RT, 60% audience (33 points difference)

2020

None

[DEVS, Alex Garland, 8-episode mini-series for Hulu]

2021

None

2022

THE NORTHMAN (Robert Eggers) Prod. by Regency and Dist. By Focus (specialty wing of Universal)

Budget: est. $70-90,000,000

Worldwide gross to May 4: $43,934,635

Rotten Tomatoes: 89% critics 66% audiences (23 points difference)

MEN (Alex Garland) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: Unknown. Collider refers to it as “a low-budget horror film.”

NOPE (Jordan Peele) Prod. Monkeypaw Productions and Dist. Universal

Budget: Unknown [July 23, 2022. Variety now reports the budget as $68 million.]

DISAPPOINTMENT BLVD. (Ali Aster) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: Unknown

Clearly the pandemic has delayed the completion and release of horror films, as it has with other genres, resulting in a rush of releases by all four directors in the same year. There might have been films by all four directors in 2019, but Garland was presumably busy producing, writing. and directing all eight episodes of the FX series Devs, which premiered on March 5, 2020. The series could be described as being a combination of the sci-fi and horror genres, rather like Ex Machina.

The prestige

Reviews, professional and amateur

These days, one indicator of public prestige, albeit a crude one, is the critical aggregator site, Rotten Tomatoes. It is striking that every film in this group has been rated more highly by professional critics than by audience members. Other films mentioned in discussions of prestige horror also see a similar split, as with Saint Maud (2019, Rose Glass, distributed by A24), which had a 93% critical rating versus 64% audience approval. On the other hand, Saw (2004, James Wan, distributed by Lions Gate), which is definitely not in the prestige category, had a 51% critics rating and 84% audience approval.

Festivals and Awards

It is perhaps going a bit far to call these art-house horror, since they usually play multiplexes. Still, some premiere at prestigious festivals dedicated mostly to indie films that do play art houses. These include Sundance for The Witch, Get Out, and Hereditary. Ex Machina and Us were first shown at SXSW, the latter as the opening night film–a position held by A Quiet Place the year before. The Lighthouse premiered out of competition at Cannes, and Men will do so later this month (and possibly Disappointment Blvd., see above). Announcing the latter, Deadline commented, “The non-competitive independent sidebar to the main Cannes festival has grown in reputation in recent years, having premiered pics such as Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse, Sean Baker’s The Florida Project and The Rider by Oscar winner Chloé Zhao.”

For Nope, Peele took a more mainstream approach, revealing an extended trailer at Cinemacon on April 27, 2022.

Obviously awards signal prestige. To name some of the most notable, Eggers won for best director of a dramatic film for The Witch at Sundance. The Lighthouse won the critics’ FIPRESCI prize at Cannes, was nominated for an Oscar for best cinematography, and won the cinematography prize from the American Society of Cinematographers. Peele’s Get Out was nominated for four Oscars, winning best original screenplay. Peele made Time‘s list of the 100 most influential people in the world and the top-ten lists of the National Board of Review, the AFI, Time, and others. (He was also nominated as a producer of BlacKkKlansman.) Ex Machina surprised just about everyone by winning the Visual Effects Oscar in competition with Mad Max: Fury Road, The Martian, Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and The Revenant. The Hollywood Reporter considered its win “arguably the night’s biggest upset.”

These are some of the highly prestigious prizes. Festivals and prizes have proliferated in recent years. Local critics’ associations and proliferating specialist sci-fi/horror/fantasy festivals give out hundreds of awards, most of which never come to the general public’s attention. They do, however, stimulate interest among the core audience for horror films. (Extensive lists of such festival’s nominees and winners are provided on IMDB.)

Production and Distribution

The first three films on the above list made impressive profits on small budgets–especially Get Out. Ex Machina and The Witch were financed by cobbling together money from small, obscure companies and then picked up for distribution by A24. Both films came out one and two years respectively after A24 had released its first film in 2013, so relatively early in the company’s existence. They were among the many that have made A24 the most successful, admired producer and distributor of independent and foreign films. Ex Machina provided A24 with its first Oscar win.

The third, Get Out, made a spectacular amount of money on its modest budget.

These successes may have encourage Paramount to pick up the fourth, Annihilation, in the expectation of a similar success. Despite being one of the best films of the group (in my opinion), it was not popular and is the biggest money-loser of the group (though the final grosses for The Northman are yet to come).

The sub-genre bounced back with Heredity, which was (and may still be) A24’s biggest money-maker. The company then bankrolled Aster’s follow-up, Midsommar, which was profitable, if less so than Heredity. A24 also produced both films, so it was able to keep the entire take. These successes were perhaps some consolation for The Lighthouse‘s probable failure to break even. (A24 also produced it.) Eggers departed A24 for Regency, with an estimated $70-90,000,000 budget for The Northman–far and away the largest of any of the films released so far. Its worldwide gross as of May 4, two weeks after its release, is a bit under $44 million, making a profitable result unlikely.

The importance of A24 to the prestige horror film should be obvious. It has distributed six of the eleven films and produced three of those six.

A24 was formed in 2012. Today, the company’s astonishing list of films includes many indies of all types, including Moonlight, Minari, First Cow, The Florida Project, The Tragedy of Macbeth, and most recently Everything Everywhere All at Once.

A24 seems committed to Alex Garland, having announced that they will produce and release his next film beyond Men, entitled Civil War. That doesn’t sound like a horror film, but who knows?

A24 has clearly been crucial to the careers of Garland, Eggers, and Aster, but Peele has followed a different path to success. In 2002 he began as a stand-up comic and soon was appearing in occasional episodes of such shows as The Mindy Project and Fargo. He gained fame in the comedy series Keye & Peele, which ran from 2012 to 2015. He also produced it, forming his own production company, Monkeypaw Productions in 2012. Coincidentally this was the same year that A24 was formed, perhaps helping explain why the careers of these directors have progressed in parallel. He has continued to produce shows like Twilight Zone and Lovecraft Country. He turned to filmmaking in 2017 with Get Out, which was produced by Blumhouse, known for its low-budget, ordinarily less prestigious horror films. Universal distributed what became the most profitable film of the entire group, compared to its original budget, and soon formed a closer relationship with Peele.

In an interview with Indiewire, Peele described being cautious about asking for a larger budget for his next film, Us.

When he sat down with Universal, the studio that distributed “Get Out,” to pitch his sophomore feature, “the cards were kind of in my hands,” Peele said. “It didn’t feel like an audition. It was me telling them, ‘This is what I want to do, this is where I want to do it, how’s that sound?’” […]

“I had about five times the budget on this one, which by movie standards is still not that expensive of a film,” he said. “That was the key for me. Otherwise, I may not have had my freedom. As a filmmaker, I also thrive with a certain restriction. I didn’t want to overreach with the budget and all of a sudden have a studio being responsible on me.” He laughed. “There’s never been a point where they’ve expressed anything but wanting to make this.” When Universal gave Peele the green light to make “Us,” it also signed a first-look deal with his Monkeypaw Productions.

Universal financed and released the film, sending it to SXSW for its premiere. Remarkably, it and Get Out generated almost identical worldwide grosses. Indeed, they are far and away the top earners among this set of films. In 2019, the year Us came out, Universal signed Peele to a five-film contract, reportedly worth $300-400,000,000.

As a result of all this, Peele stands out from the rest of the group by being a very rich man. His worth in 2021 was widely estimated at $50,000,000.

This deal presumably included the recent remake of serial-killer film Candyman (2021), produced and written by Peele and directed by Nia DaCosta.

How much higher the budgets will be for these future films is impossible to predict. It is notable, however, that Nope was shot by Hoyte van Hoytema, cinematographer of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, Dunkirk, Tenet, and upcoming Oppenheimer. It was made on film and had sequences done in 65mm. It will be shown in Imax theaters, an obvious step up from the previous two films.

Moreover, Peele is among top Hollywood directors collaborating on Imax’s development of its next generation of cameras. Indiewire reports:

The new models are expected to be an improvement over IMAX’s current offering of cameras that utilize their proprietary 65mm film. The new cameras will be quieter, with a series of new features added to enhance usability. In addition to the four new cameras, many existing IMAX cameras and lenses are expected to be updated and improved.

If that was not exciting enough, the company will be collaborating with some of Hollywood’s top visual artists on the camera designs. Major directors including Christopher Nolan and Jordan Peele will weigh in on the new film cameras, as will top cinematographers including Hoyte van Hoytema (“Tenet”), Linus Sandgren (“No Time To Die”), Rachel Morrison (“Black Panther”), Bradford Young (“Arrival”), and Dan Mindel (“Star Trek”). Combined, those filmmakers account for many of the most acclaimed large-scale movies shot on film in recent years, in addition to even more that were shot digitally.

If Nope is a success, as Forbes is predicting it will be, will Peele branch out into other genres or continue to make prestige horror films on a bigger budget? His enthusiasm about Imax technology may hint at an inclination to break out of his current pattern for other effects-heavy genres. Still, perhaps a clue comes from the name he gave his production company, Monkeypaw Productions, invoking the classic Le Fanu horror story.

The distributors, and in the case of A24 producers, of these films have turned these directors into brand names elevated above most directors of horror films. The trailer for The Northman touted Eggers as “visionary” (top) while Paramount combined the signs of prestige in its poster: “new terror,” emphasizing Peele’s consistency as a director of horror; his “mind,” suggesting his genius for this sort of filmmaking; and naturally his record as an Oscar winner (above left).

Midsommar madness

Midsommar has emerged as one of the most admired films of the cycle, despite having had the lowest Rotten Tomatoes critics score and third lowest audience score. Its move toward prestige began quickly when less than two months after the film’s July, 2019 release, Aster appeared at the Scary Movies Festival at Film at Lincoln Center, introducing the Director’s Cut of the film. The length was increased from 148 to 171 minutes.

Martin Scorsese unexpectedly helped to raise Aster’s profile. Readers will remember his infamous remarks about MCU films not being cinema and his subsequent explanation of what he meant in The New York Times. There he listed some directors whose films exemplify genuine cinema:

Another way of putting it would be that they are everything that the films of Paul Thomas Anderson or Claire Denis or Spike Lee or Ari Aster or Kathryn Bigelow or Wes Anderson are not. When I watch a movie by any of those filmmakers, I know I’m going to see something absolutely new and be taken to unexpected and maybe even unnameable areas of experience. My sense of what is possible in telling stories with moving images and sounds is going to be expanded.

That’s pretty heady company for a director of horror films who has made two features, but there was more to come.

Scorsese followed up by writing an introduction to a book accompanying A24’s release of the Director’s Cut on Standard Blu-ray and 4K Ultra HD, available only directly from the company and packaged in jewel boxes charming enough that they could grace a Wes Anderson film. It shipped on July 20, 2020, about a year after the film’s release.

In early 2020, there was a considerable expectation among critics and fans that that the film would be nominated for Oscars. When that failed to happen, journalists’ lists of snubbed films often mentioned it indignantly. The Washington Post ran a story entitled, “The Oscars should get over their fear of horror films,” mentioning Midsommar, Us, and Heredity and especially Florence Pugh’s and Toni Colette’s performances. Indiewire listed Midsommar alongside The Farewell, Her Smell, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Booksmart, and Uncut Gems as films unfairly receiving no nominations.

Remarkably, a protest of sorts against Midsommar‘s lack of nominations was mounted during the opening musical number of the 2020 Oscars show, on February 9. Janelle Monáe headlined and staged it, including a group of backup dancers, some of whom were dressed as various characters from some of the year’s best-picture nominees: Joker, Jojo Rabbit, and Little Women. Prominent among them, however, are four women in white Midsommar costumes, and to make the point completely clear, Monáe herself donned a copy of the protagonist’s floral May Queen dress for the last part of the number (see bottom). Pugh was in fact nominated for Best Supporting Actress that year, but it was for Little Women. She didn’t win, but she managed to get an implicit shout-out in the opener.

The extensive press coverage of the number suggested that the content was Monáe’s idea, but the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences must have approved and cooperated to some extent, given that it presumably provided the costumes and would have been aware during rehearsals that the film references in the song and dance gave the snubbed films equal or even greater attention than the nominated ones. The number inspired considerable coverage in the press, and many upset Midsommar fans posted tweets that suggested they were somewhat placated by the number.

The Academy made further amends two months later, when on May 9 the Academy Museum announced that it had put in the winning bid ($65,000) for the original May Queen dress from the film, which was sold in one of A24’s series of real movie props-and-costumes auctions for Covid-related charities (FDNYFoundation being the Fire Department of New York).

The dress was put on display in the Museum in time for the September 30, 2021 opening.

Based on a preview tour for journalists, on September 22 Timeout declared the dress one of the eleven coolest things to see at the Museum, a list which also included Judy Garland’s ruby slippers and the shark from Jaws. The first “prestige horror” film to be represented in the Academy Museum (I presume) had brought the genre a new level of respect. Maybe next year Alexander Skarsgård or Steven Yuen or Jessie Buckley or Rory Kinnear might actually receive actor nominations, not to mention some best-picture nods for the new films.

One final observation. The prestige phenomenon has been happening for some time now with foreign films seeking release in North American market. Making inexpensive horror films occasionally works as a way for unknown directors to break into an otherwise difficult market for unknown directors. Examples would include the Swedish film Let the Right One In (2008, Tomas Alfredson), the Icelandic Lamb (2021, the first feature of Valdimar Jóhannsson), which premiered at Cannes and was nominated for best international film this year, and currently the Finnish Hatching (2022, the first feature of Hanna Bergholm). Interestingly, the pattern of critics rating the films higher than audiences as measured by Rotten Tomatoes holds true for such films as well, with the three titles scoring respectively: 98%/90%, 86%/61%, and 92%/59%. Their distributors were, respectively: Magnolia Pictures (under its genre label, Magnet Releasing), A24, and IFC Midnight (ICF Films‘s genre label).

A few notes.

[Oct 31, 2022: for more on prestige horror and A24 see my analysis of Men and discussion of A24 as an “auteur studios.”

Scott Derrickson is an interesting case where a director has specialized in mainstream horror films before moving on to a MCU franchise blockbuster, Doctor Strange (2016). He was at work on the sequel when a disagreement of some sort with Marvel led to his departure. He has returned to horror with the upcoming serial-killer film The Black Phone (distributed by Blumhouse) which I mentioned seeing the trailer for. His announced projects appear to be mainstream horror and fantasy.

The prestigious horror films of the past that I mentioned all received Oscar nominations, with some wins (in bold), mainly in below-the-line categories. The Exorcist: adapted screenplay, sound, picture, actress, supporting actor, supporting actress, director cinematography, art direction, editing; Rosemary’s Baby: adapted screenplay, supporting actress; Jaws: sound, editing, musical score, picture; Children of Men: adapted screenplay, cinematography, editing; and Bram Stoker’s Dracula: costume, sound effects editing, makeup, set design.

Directors of modest horror films do sometimes return to the fold after making a blockbuster. After a string of horror films, Scott Derrickson directed Doctor Strange (2016) but now returns with The Black Phone. From the trailer referenced above, this looks like a conventional serial-killer film, apart from having Ethan Hawke as its villain. Guillermo del Toro returned to his more comfortable indie roots after Pacific Rim, and Taika Waititi apparently is keeping his word about alternating big projects (Thor: Ragnarok and an upcoming Thor film) and personal ones (Jojo Rabbit); among his many announced films are several franchise films, but also Tower of Terror, apparently a horror film.

[May 17, 2022] Alex Garland seems to be abandoning the horror genre, at least for his next film. As its title, Civil War, suggests, its an action film about that conflict. As he says in a recent interview, he’s even contemplating giving up directing and sticking to screenwriting.

[May 22, 2022] Collider‘s Chase Hutchinson has posted a list ranking A24’s twenty-one horror films from worst to best. (I don’t know when it was originally posted, but it was updated yesterday, presumably to include Garland’s Men.) As I said, I’m not a big horror fan, so I had never heard of most of these, so I’m obviously not one to quibble with the ranking–apart from the fact that I would put The Lighthouse higher than Midsommar and The Witch. I haven’t seen Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, which tops the list, so I have no idea whether it really deserves to be number one.]