Archive for the 'National cinemas: Italy' Category

Thrills and melodrama from the 1910s

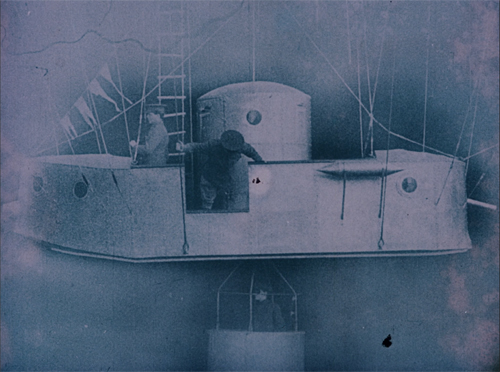

Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate (1915).

DB here:

Two new DVD releases remind us how 1910s filmmakers, unconstrained by realism, used the newish medium of film as a vehicle of charming, sometimes silly fantasy. One is the virtually unknown 1915 Italian feature Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate; the other is the famous but little-seen 1919 serial adventure Tih-Minh, by Louis Feuillade. The Filibus disc also contains a 1916 Italian feature Signori giurati… (“Gentlemen of the Jury,” here The Jury Decided). None seems to me a masterwork, but all are enjoyable and have something to teach us about the almost mad ambitions of an era discovering the power of long-form cinematic storytelling.

Lady with an airship

One thread over the life of this blog has been my nagging claim that the 1910s have not been widely recognized as the lively, innovative years they were. Yes, there was Griffith and Chaplin, but after that people tend to move on to rhapsodize about the glories of 1920s Europe and Hollywood. Of course many viewers appreciate the early work of Mary Pickford, William S. Hart, Buster Keaton, and Doug Fairbanks, and there are fans of great European directors like Sjöström and Feuillade, but even these luminaries are chiefly known for only a film or two.

Many scholars have labored loyally to bring to light major figures like Lois Weber and Albert Capellani, but these revelations remain niche tastes. Kristin and I have done our bit on the blog, in many entries and in the video lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” That suggests that today’s film industries, film culture, and artistic options have their sources in this era that, in retrospect, teems with creative possibilities.

The sheer imaginative variety of this output is brought home to me virtually every time I go back to see something recently discovered. My extended stay at the Library of Congress Kluge Center back in early 2016 was a smack on my head. In America, while filmmakers were elaborating the “continuity” system of storytelling (still with us), they were also pursuing side paths and fresh possibilities. (To check, start with “Anybody but Griffith” and move to later entries.) My discoveries complemented my years of visiting European archives to investigate both major auteurs and little-known films. (See the category “tableau staging.”) Now these releases, courtesy of Gaumont (Tih-Minh) and the cooperative efforts of Amsterdam’s Eye Filmmuseum, Milestone Film and Video, and Kino Lorber (Filibus) offer some new angles on the period.

Filibus centers on a supervillain who, unlike Fantômas or Dr. Gar el-Hama, is a woman. Like them, she’s a master of disguise, appearing as a genteel lady but also a suave gentleman and a sleek masked marauder. She steals jewelry through the usual methods: casing a household, sizing up the spoils, and confounding the authorities. What sets her apart is that she travels in a midsize airship that allows her to move swiftly from place to place and lower herself in a gondola to the numerous balconies that give access to the treasures.

She’s also adept at outsmarting the detective Kutt-Hendy. Exploiting the current public fascination with pseudo-scientific detection, the film shows her capturing his fingerprints on a rubber glove, and then leaving them at the scene of the crime. But she has old-fashioned tools as well, including a mysterious knockout scent.

Capably if unspectacularly directed by Mario Roncoroni, the scenes are mounted in straightforward ways for the period. Cutting, as you’d expect, consists largely of linking scenes or occasionally enlarging a detail we need to see, such as a camera inside the eye of a cat statue.

Within dialogues, simple axial cuts give us access to actors’ expressions. Sometimes Rondoroni moves a figure closer to the camera without motivation, simply to show us things more clearly, before the figure then retreats a couple of steps.

This is an anachronistic device, common in much earlier films. Most directors of the period motivated such movements by having something in the foreground that would draw the actor nearer to the camera.

The preposterousness of it all is well-recognized by everyone concerned, I think. The most impressive set, a parlor boasting Egyptomania galore along with the supposedly ancient but highly inauthentic cat sculpture, gets a good workout during the crime and the investigation. What remains, though, is Filibus’ unique transport system that allows her to bypass all the driving down roads and clambering up building facades we get in Feuillade. A blimp and a basket do the trick, leaving Filibus to sail off to her next conquest.

The film was noted as over-the-top in its own day. One critic wrote: “Great drama of adventure? Say rather a great cinematic mess of adventures. . . .” Evidently the tackiness of the special effects was evident as well. But we’re lucky to have it as one more document of the sometimes overstrained efforts to pack fresh sensations into the still-emerging format of the feature film.

Opium and murder

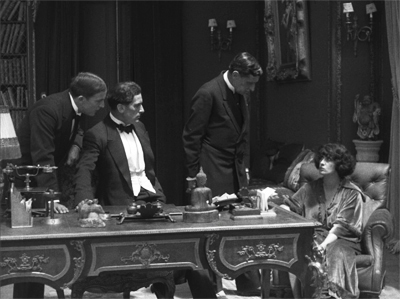

Signori giorati… is more orthodox and, I think, more satisfying as a story. A classic salon melodrama with plenty of diva posturing, it shows the decadence of the very rich brought to account. The adventuress Julienne (originally Lina) Santiago has seduced Dr. Nancey into setting up a plush opium parlor. Every night, the rich come to the “House of Forgetfulnesss,” where Julienne and the doctor blithely pick their pockets. When the police get interested, Julienne betrays Nancey and bolts, later to take up with one of their clients, the Marquis de Vallier. He resolves to marry her and brings her home to meet his daughter Helène (Valeria Creti, aka Falibus) and her husband. A deadly intrigue begins.

Signori giorati… shows the pluralism of visual expression of the period. While depth staging isn’t much developed here, the vast opium-den set carries the action far into the distance, where Julienne, masked, awaits the Marquis (above). Later, lurking in the reeds, Julienne stalks Helène’s husband.

Courtroom scenes in 1910s films are surprisingly varied, and director Giuseppe Giusti offers an unusual array of angles on the action.

A split-frame flashback illustrates courtroom testimony.

None of these moments is extraordinary for the period, but they nicely exemplify visual strategies becoming normalized in European cinema. Likewise, the somewhat awkward linkage between the first section around the opium den and the second on the Vallier estate show the need to tighten up the overall arc of the narrative–a problem European films would face for some years.

An unusual feature of the disc is the inclusion of five short films from the Amsterdam premiere of Filibus in 1918. This was made possible by the Eye Filmuseum’s splendid collection of early films from around the world shown in the Netherlands by the distributor Jean DeSmet. There’s also a brief short giving background to that collection.

From Vietnam to the Riviera

Tih-Minh (1919) followed in the wake of Louis Feuillade’s successful serials Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), Judex (1917), and La Nouvelle mission de Judex (1918). Released in installments from February to April 1919, Tih-Minh followed an important Feuillade feature, Vendémiaire, released in January. Throughout the same years Feuillade signed dozens of shorter comedies and dramas. Not only was he an efficient director on a scale we can hardly imagine today, but he had a powerful incentive: Gaumont gave its top directors a percentage of a film’s revenues, and Feuillade’s salary made him wealthy.

The plot revolves around a treasure supposedly hidden in Indochina. But where? A Sanskrit book contains notes, in code, about its whereabouts. The explorer Jacques d’Athys has unwittingly acquired it during his last expedition. Learning this, former German spies Kistna the “Asiatic” and Dr. Gilson recruit the hapless Marquis Dolores (above) and target Jacques’ villa in Nice. Jacques has also brought back the delicate young woman Tih-Minh (also above), daughter of a French colonist murdered, it’s revealed, by Gilson (né Marx!). The complications around the coded message lead the gang to a series of raids on the household, usually involving efforts to kidnap Tih-Minh. The efforts are resisted by our heroes–Jacques, his loyal servant Placide, the maid Rosette, and the British diplomat Sir Francis Gray.

Tih-Minh has an essentially comic structure. Unlike Fantômas and the Vampires, this gang can’t catch a break. Nearly every attempt they make, involving poisons, amnesia serum, hypnosis, and accomplices smuggled into the household, is thwarted, quickly or eventually. The ineptitude of Kistna’s gang is nearly matched by the passivity of Jacques’ team. They seem to wait around for the next assault, and when they prepare a trap, it usually fails. Only Placide, consistently suspicious, mounts countermeasures. Just when you wonder whether Nice has a police force, Jacques announces they can handle things best themselves.

Tih-Minh, a favorite of mine over the years, cracked a bit on this go-round. For the first time I found the opening installments dilatory and meandering. Feuillade is counting on our enjoying the company of these comfortably rich people and their rounds of coffee breaks, walks on the estate, and flower-picking in dazzling sunlight. And it is a kind of Bower of Bliss, which will eventually host three weddings.

Unlike the earlier serials, where he relies on composition in depth, here he favors lateral layouts. It’s as if the speed of the production pressed him toward lining up characters talking to one another in long-shot and medium-shot. Yet as I wrote about here, he varies the placement of heads in graceful waves.

These framings look forward to his later work’s “long-take” setups, broken only by dialogue titles.

The pacing and flashy visual invention pick up considerably in the later installments, when Feuillade hurls his cast through the magnificent landscapes of the Riviera. During the war, Gaumont moved substantial portions of production to the Victorine studios in Nice. Installing himself there in 1918, Feuillade takes advantage of everything in the neighborhood. You can sense his delight in finding ways to use the ocean front, rocky terrain, gorges, mountain crags, decrepit hilltop castles, luxurious estates, and hotel rooftops.

Pursuits across these forbidding spaces are a powerful attraction in their own right, and the second half of the film does not disappoint. For some shots the camera seems a mile away from the tiny human figures.

The actors accordingly give their all. Placide’s physical comedy is matched by his willingness to be beaten up, dropped from a great height, or folded up into a trunk lashed to an automobile roof. Flung into the ocean, he laughs it off.

Heroes and villains alike are willing to clamber around scaffolding and window ledges and crawl down the face of a mountain.

Mary Harald as Tih-Minh, apparently a wilting flower, seems game for anything as well.

We’re so used to stunt doubles for action scenes that we forget that long ago actors were athletes.

The vertiginous spaces and the bravado of the performers come to a climax when the chase moves to a zipline carrying rock from a quarry down into a valley. The villains dive into one of the gondolas and ride off to infinity. Undaunted, our heroes follow.

These shots, a rebuke to the cheesiness of Falibus‘ special effects, are alone worth the price of a DVD. And you thought Preminger treated actors roughly?

One more aspect of this release makes it a must-have for admirers of early film. It is one of the finest digital transfers of a silent film to disc that I have ever seen. Derived from a pristine negative, it is a perfect illustration of what 1910s cinema looked like at its best. (Thankfully, it is not tinted. Tinted versions often smudge original photographic detail.) We always knew that there was more on a 35mm orthochromatic film than we could see. Now we see it.

Gaumont’s disc of Tih-Minh is coded for all regions and contains optional English subtitles. Unless a US distributor picks it up, it will be available only at places like Fnac and Amazon.fr. University libraries and film departments should be able to get copies easily. Beware the bootleg version of the Belgian print (the source for the restoration’s intertitles) offered on eBay and elsewhere.

The Italian cinema of the 1910s was no less stylistically innovative than that of other nations, but the films haven’t achieved canonical status. Except for big, influential productions like Cabiria (1914), the output of this major industry has been overlooked, largely for reasons of availability. A breakthrough came with the superb collection, Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader, ed. Giorgio Bertellini (New Barnet: Libbey, 2013). My amateur forays into the area have yielded some nifty items, such as Fabiola (1918) and Maman Poupée (1919) and Il Maschera e il Volto (1919), as well as many I hope to share in the future.

Critical response to Filibus is sampled in Vittorio Martinelli, Il cinema muto italiano 1915, part 1: I film della grande guerra (Rome: Bianco e Nero, 1992), 190-192.

The standard study of Feuillade is Francis Lacassin’s magisterial Louis Feuillade: Maître des lions et des Vampires (Pairs: Bordas, 1995). (It’s a real bargain here.) I survey Feuillade’s staging strategies in Chapter 2 of Figures Traced in Light. A more general account of silent film staging in depth is in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Not incidentally, the Eye Filmmuseum offers a rich array of films from many periods, including the 1910s, for free viewing online.

Tih-Minh (1919).

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Streaming goodness

Trailer by Christina King.

DB here:

We’re been tardy about posting lately. Reasons, not excuses: I finished a book manuscript of ungainly length. Kristin has been preparing and giving a talk for an Egyptological conference. Some medical matters (non-fatal, boring) have preoccupied me further.

But who could resist telling you about the offerings of our revived Wisconsin Film Festival? Felled last spring by COVID, it has bounced back as lively as ever. Over 110 films are streaming over eight days, 13-20 May.

Some films are available to anybody anywhere, others only to people in Wisconsin or the Midwest or the USA. Some screenings may be “at capacity” because of audience limits set by distributors (who reasonably don’t want to cannibalize screenings at other fests). You can check your access to a film by visiting that film’s Eventive page on the fest site, and you can learn how to access the fest shows on the Eventive information page.

In particular, many of the regional productions we proudly host might be things you can’t be sure of catching anywhere else.

The other S-word

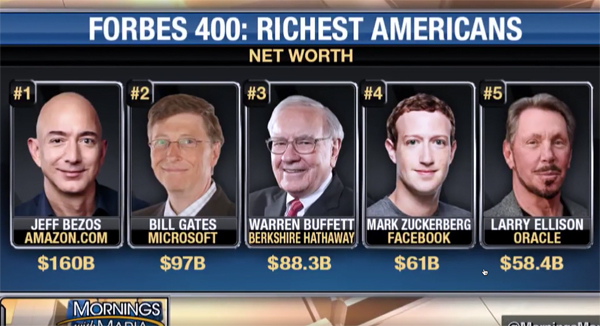

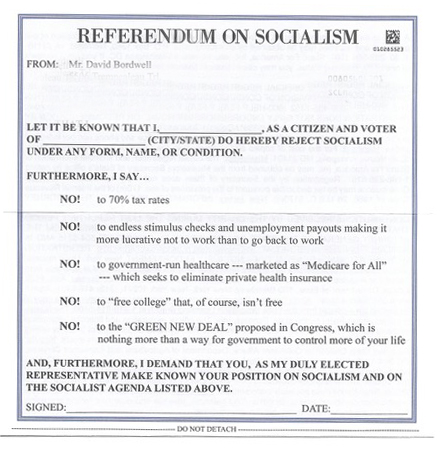

“Socialism” is back in the news. 120 mostly obscure brass hats have just proclaimed that the 2020 election was stolen. (Maybe this level of cluelessness explains our post-1945 record of winning wars.) The signatories add that the immediate conflict is “between supporters of Socialism and Marxism vs. supporters of Constitutional freedom and liberty.” These writers who obviously have not seen Dr. Strangelove or Seven Days in May. Otherwise, they’d try out better lines.

Earlier this week I received an invitation from former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley to sign up for the “National Referendum on Socialism.” The envelope window displayed a teasing flash of legal tender. It turned out to be a crisp 100-Bolivar note from Venezuela, worth about $.10.

This crushing proof that socialism doesn’t work was accompanied by Nikki’s memoir about seeing, first hand, the failures of regimes like Venezuela, Cuba, and Communist China, all representing “the terminal stage of socialism.” She reports that some of them lack toilet paper. This outrage must not stand.

For me to receive this, the Republican Big Data dragnet proves as undiscriminating as a notification I’ve inherited a fortune in Bitcoin. Still, I was happy to reply. I voted yes, or as Nikki would have it YES!, to all the options. These included 70% tax rates for her and her friends and a rejection acceptance of Nordic social democracy, an option her world travels seemed to have missed. And I’m keeping the Bolivars.

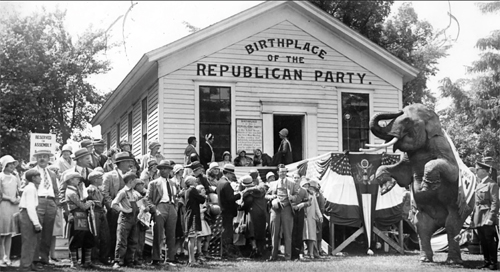

So the right-wing lies make it all the more timely that WFF has included a double feature that might well speak to the rising interest in socialism among the young and the equality-curious. The main film is Yael Bridge’s The Big Scary “S” Word. It interweaves an historical narrative with two ongoing dramas of today. From the survey we learn, as Cornel West explains, that socialism is “as American as apple pie.” John Nichols, author of The S-Word, is on hand to trace the movement back to the nineteenth century and remind us that “The Republican Party was founded by socialists.”

Other commentators show how the rise of capitalism and the cascade of crises it brought forth tended reliably to arouse demands for equal rights and economic justice. We learn of Lincoln’s friendly correspondence with Marx, of slavery’s centrality to American capital accumulation, and of the post-World-War II reaction against the New Deal, building through Reagan to Bush and Clinton. The 2008 financial crisis supplied fresh momentum for a critical reaction to capitalism; Wall Street’s capture of the economy encouraged some people to take a new look at socialist policies.

There are as well doses of theory, as when political scientists point out that capitalism depends crucially on expanding the concept of private property and inclines toward treating unpropertied individuals as interchangeable, expendable units. This may explain why conservatives explode over graffiti but praise a teenager shooting down peaceful demonstrators.

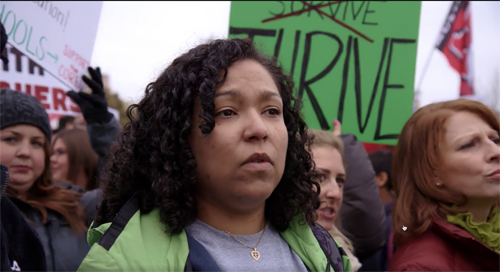

Threaded through Bridge’s account are affirmative moments: the creation of worker-owned coops, the establishment of the Bank of North Dakota (owned by taxpayers), and the stories of two young people who were fed up with injustice. One is Stephanie Price, an elementary-school teacher working two jobs; some of her income goes to books and supplies for her students. (This scenario is familiar.) She joins a teachers’ strike and finds that the union isn’t effective in fighting their Oklahoma legislature. Chris Carter, an ex-marine, is the only socialist on the Democratic side of the Virginia legislature. He learns that even Democrats are capable of sabotage (surprised?), running an oppo ad linking him with a hammer and sickle. The stories of Stephanie and Chris provide suspense and yield a flare of hope.

How to Form a Union, directed by Gretta Wing Miller, is a story that could only come from the People’s Republic of Madison. During the 197os, the Willy Street Coop was an emblem of our town’s progressive tradition. But as it expanded, it faced competition from Whole Foods and other hip purveyors of provender. (I remember visiting Whole Foods and feeling old when Björk came on the Muzak.) Workers at the Coop accused it of corporatization and agitated for higher wages, less draconian shift policies, and ultimately a union. What happened next is told with quiet passion and a fine array of talking heads.

The proclamations of our statewide election officials, cartoonish reactionaries like Ron Johnson, Glenn Grothman, and their lot, have over the last few years made me think that such large, loud, stupid people typify Wisconsin. Seeing these two films, steeped in state history, reminded me of things we can be proud of. Yes, Wisconsin gave America Joe McCarthy and Scott Walker and Reince (Obvious Anagram) Priebus and Scott Fitzgerald, who greeted voters in a hazmat suit while assuring them that Covid was no danger. But we also gave America socialist mayors, Bob LaFollette (a Republican), and political fighters like Tony Evers, Mandela Barnes, Mark Pocan, and Tammy Baldwin. These are people on the right–that is, left–side of history.

Roman New Year

The Passionate Thief (1960).

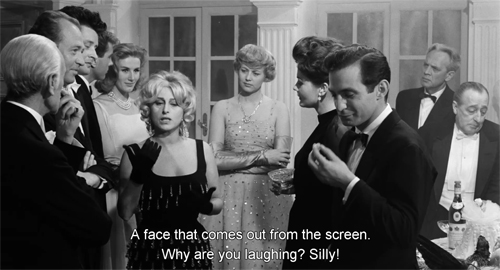

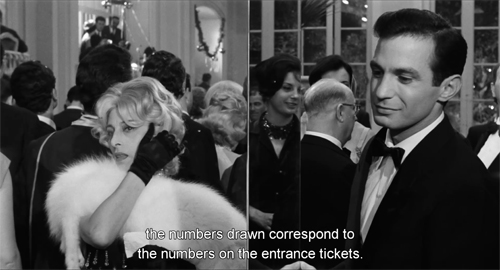

One of the long-running revelations of the Bologna festival Cinema Ritrovato is the rich tradition of Italian comedy. (See here, and here.) One admirer is our programmer Jim Healy, who this year brought us a delightful example, Mario Monicelli’s The Passionate Thief (another film from the fabulous year 1960). Two top Italian stars, the vivacious Anna Magnani and the glum Totò, work on the fringes of the film industry. This justifies behind-the-scenes glimpses of Cinecittà, as well as the usual satire on the follies of filmmaking. We’re introduced to Magnani as part of a crowd in a sword-and-sandal epic, while Totò scrapes up work as an extra.

But it’s New Year’s Eve, and Magnani seeks out friends for a party. Meanwhile Totò is recruited as a partner for pickpocket Ben Gazzara, in the sort of imported-star turn that was common in European coproductions. His brooding, cynical presence adds a touch of gravity to a crowded night of crisscrossing destinies featuring a drunk American millionaire (Fred Clark), frenzied Roman partygoers, and rich Germans whose mansion is invaded by our trio. Gusto, brio, sprezzatura, zest–choose the word, this movie has plenty.

It also has stunning black-and-white cinematography, and its use of the 1:1.85 ratio should be studied by every film student. The screen area is shrewdly filled in long-take mid-shots.

And since we know Ben is a thief, his wandering left hand draws us away from La Magnani’s monologue, while Totò frets in the background.

Yes, mirrors are involved throughout, sometimes creating weird split-screen effects.

Much of the movie was shot on location and it reminds us that the splendor of La Dolce Vita (released the same year) wasn’t a one-off.

This ripe imagery doesn’t slow down the bustle of the whole thing. The plot seems more episodic than it is; the opening sets up a minor character (a tram driver) and a food motif (lentils) that will pay off later. Clever as the devil, The Passionate Thief is one of those pieces of good dirty fun that keeps you, and us, going back to film festivals.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of the festival panjandrums (I always wanted to use that word) Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

The Passionate Thief (1960).

Vancouver: Stories, spliced and stacked

Sarita (2019).

DB here:

Humans love stories, the more the better. As a result, many storytellers find ways to bring distinct story lines together. The most common way is to link them, through subplots involving major and minor characters. Viktor Shklovsky urged us to think of folktales, novels, and plays as “braided” out of several story lines. At other times, the stories are bracketed within a bigger plot. A character tells others about incidents in childhood, or characters tell completely detachable tales, as Scheherazade and Chaucer’s pilgrims do. Instead of braiding, we get embedding within a frame situation.

I started to think again about these options watching four films at the always exhilarating Vancouver International Film Festival. All were engaging, partly because they often mixed comedy and drama in rewarding ways. They also offer a nice menu of creative possibilities, exploited by ambitious filmmakers.

Screen life

An omnibus film can offer a frame story, as the British classic Dead of Night does, but most modern ones simply line up one tale after another, in blocks. Essentially these are short stories, and they tend to follow literary patterns.

One option is the “snapper,” the plot consisting of twists and a sting in the tail, a surprise ending. Edgar Allan Poe may have invented this format, O. Henry canonized it, and Roald Dahl gave it a grisly tenor. Diverting examples of the surprise-ending story can be found in the omnibus Spanish film Tales of the Lockdown (2020).

All five modules are comic, though sometimes in a macabre vein. Produced during the COVID-19 lockdown, somehow staged and shot remotely, each episode is cleverly scripted and elegantly directed. In one, a reclusive Milquetoast is pressed by an aggressive neighbor who wants to sell him a plan to expunge “bad vibrations” from his apartment. The Feng Shui saleslady gets more than she bargained for when she learns the source of those vibes.

In another, an aspiring hitman recruited by The Agency gets a remote tutorial from an experienced killer, who makes him practice techniques on a teddy bear and the dogs he snags from the neighborhood. A third, gentler episode is still tricky: we’re led to presume some things about a couple that turn out to be not valid–at least, not until the end. Sorry to be so elliptical, but films like this oblige you to avoid spoilers.

The most straightforward comedy concerns a woman auditioning by video for a TV part, aided by her husband who decides he could get a role as well. For a local audience, the fact that she is played by star Sara Sálamo and her actual husband, a Real Madrid football player, doubtless adds to the fun. The last episode, a black comedy, presents a rich couple’s extreme reaction to a tenant strike in one of their buildings.

The filmmakers have found many nifty ways to exploit the limited viewpoint enforced by lockdown. Naturally, remote conversations take place over laptops, which motivates minimal change of setting and little need for elaborate action scenes, or even ordinary staging in interiors. Offscreen action is likewise conveyed minimally, just by speech or noise in the world outside. The funniest moments in the fifth episode concern the rich couple learning they’ve received a “package” which we never see and must assume is problematic, since the thug on speakerphone says it’s “middle-aged.”

Confined settings have in effect created five “chamber plays” of the kind I’ve talked about before. This constraint allows directors to design and dress settings and find playful compositions to accentuate the plot twists that keep us glued to the screen.

In all, Tales of the Lockdown is a display of light and lively cinema craftsmanship. It’s heartening to see creative energy maintained in pandemic conditions. It premiered on Spanish Amazon Prime and would be worth looking for on that platform in other markets.

Food, memories, and the future

The major alternative to the twisty snapper tale is the “slice of life,” the muted drama of a situation that may change little or not at all. Here the emphasis falls on characters–their relations, their reactions, and their sensitivity to one another. The classic examples come from Chekhov and from Joyce’s Dubliners, but they’re also prevalent in what used to be thought of as the classic New Yorker short story of John Cheever or J. D. Salinger.

Pensive incompleteness of this sort well suits the Hong Kong film Memories to Choke on, Drinks to Wash Them Down (2019). Directors Kate Reilly and Leung Ming-kai have made three of the four stories fictional, treating them as vignettes of restrained realism. A Malay caregiver takes a grandma on an afternoon outing. She wants to go to a political rally where rice will be given out, and she hopes to meet old friends from her village. The old lady is forgetful, and her chatter recycles memories of her youth. The trip turns out to be something quite different, but she doesn’t realize it. The caregiver’s concern turns a simple duty into an act of kindness, as well as a tactful political gesture.

In “Toy Stories,” two brothers meet in their mother’s toy store, which is being sold, contents and all. As with the first episode, memory comes to the fore. The men play games and quarrel about the Power Rangers figures they loved. One, who has a son, tries to find something educational to bring back. He is barely hanging on financially, while his brother has lost his job. A final scene shows a bit of development in their situation, and gives room for a little hope; it’s the only episode that ends, “To Be Continued.”

The third episode is a wistful, Wongkarwai-ish almost-romance. Ruth, an American Caucasian, has come to teach in the school where John, a Chinese, teaches economics. Both are on their way elsewhere–Ruth to teach in Beijing, John to “try something different” in America. They bond over food. (Of course; this is a Hong Kong movie.) From their meeting at a vending machine to the street stalls and cheap restaurants they explore, Ruth learns of the joys of salted egg, pig intestines, and above all yuen yeung, a uniquely local mixture of tea and coffee.

These three stories quietly evoke distinctive Hong Kong culture–the older generation’s memories of moving to the colony, the Gen-X absorption in popular culture, and the particularities of local cuisine. The fourth segment builds on these in looking toward the future.

It’s a documentary showing the barista and cat-lover Jessica Lam running for a local council seat. She faces a pro-Beijing candidate, but she’s more grassroots. She’s also an amateur and runs a fairly minimal campaign. Although she does denounce police violence against demonstrators, the main force of this sequence is the portrait of a sincere young woman trying to improve neighborhood life. This is the only episode with a climax, the election-day vote count. And there is a twist when Jessica gives her final verdict on the results.

The omnibus format has proven a strong option for contemporary Hong Kong cinema, as witness the powerful Ten Years (2015). Memories to Choke On addresses not state oppression, as that did, but the politics of everyday life, the ways in which the sagging economy and the Chinese takeover ripple through the lives of ordinary people. The impact is quite specific: local audiences would know that the actor playing John in the third segment is Gregory Wong Chung-yiu, who is at risk of years of imprisonment for participation in a demonstration. Each story is a telling vignette, a slice of Hong Kong life that will engage overseas audiences and instill a mixed nostalgia in everybody who has ever visited what Chuck Norris in The Octagon (a very different movie) calls “the place.”

Camp as community

The option of embedding the stories within a frame can blur their edges more or less. Sarita (aka Tell Me Who I Am; 2019), an Italian film about refugees from Bhutan living in a Nepalese camp, could have been a straightforward documentary about problems of exile and resettlement under the auspices of the UN. Instead, it blends real-life stories of the refugees with a young girl’s quest to recover her memory. In what filmmaker Sergio Basso calls a more fanciful and energetic approach than a “tragic” documentary would give, we get a film close to magical realism–with DIY Bollywood musical numbers.

Sarita is more or less happy in the camp. She has friends to play and dance with, a school to attend, and every opportunity to worship her favorite god Shiva. But she often quarrels with her parents and wonders why they can’t go back home, a place she has never known. Shiva wipes Sarita’s memory, endowing her with the drive to ask questions of everyone around her. In this Rip van Winkle device, we are introduced to camp routines, as well as the history of her displaced neighbors.

Sarita visits her beloved teacher, only to find that he is often laid low by his injuries from torture sessions. People tell her of ethnic cleansing in Bhutan, of disappeared relatives and political oppression. Deciding that “building my future is easier than desiring my past,” Sarita turns to her immediate prospects. But her sister tells of the hardships of getting a university education. Taking her grandma to be treated for diabetes, she learns of people sleeping in a clinic as they wait days for treatment.

After the family is assigned a home in Oslo, she acquires a super-8 camera and cassette recorder and begins to document the life she will leave behind. Now the world she rejected seems precious. After Sarita has gone, we see her grandmother and those left behind lingering at a tree, studying mementos of their departed neighbors.

Counterpointing the harsh realities of daily routines and homesickness are moments of song and dance, in bursts of brilliant color and gymnastic choreography. We also get fantasy scenes, satires on overeager bureaucracy (the resettlement officer is a hyperactive Gene Kelly wannabe), and signs that youthful exuberance can’t be contained by drab regimentation. We hear “There is no childhood here” on the soundtrack as kids are shown inventing games and playing jacks with pebbles. The ending, however, has the poignancy of pure realism (even though it’s fictitious).

This film is an extraordinary achievement. Basso and his colleagues made it over ten years–filming without electricity and no funding from national governments or NGOs. Yet the minimal conditions enabled close collaboration with the camp residents. Seeing the children’s dances inspired Basso to make it a musical, and he gained access to local leaders. Thanks to the Kuleshov effect, Sarita even appears to interview the head of the resettlement office. Although the performers had some coaching from a theatre director and a choreographer, they clearly have natural gifts, particularly Sasha Biswas, who carries the film.

In the wake of the coronavirus, seventy Italian independent cinemas cooperated in making Sarita available on streaming platforms. There, Basso reports, it has found an encouragingly large audience. Another item to look for on the streaming menu in your area!

Visions of the good life, words of disquiet

One more film about memory, but now the memories themselves are captured on film. And the stories aren’t sealed off in blocks or gently embedded in a wider frame. They’re stacked.

Again, to say too much would soften your efforts to come to grips with the teasing, hypnotic My Mexican Bretzel (2019). Think of it as layered, like a cake.

The image track consists of a Swiss family’s home movies from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. In luscious color we see a couple leading a European life of leisure: summers on the beach, winter skiing, tours of postcard capitals, yummy meals with friends in open-air restaurants. The husband, a genial, brawny fellow, clowns for the camera, but most screen time is given to his wife, a willowy brunette with a radiant smile. The landscapes might have come straight out of Holiday, that oversize American magazine dedicated to worldwide vacationing.

The next layer is a written text, purportedly a diary of Vivian Barrett. This tells of the marriage. Vivian traces the efforts of husband Leon to make and market an antidepressant. Leon’s love of flying during the war has translated into his urge to travel widely, especially on his luxurious yacht. But as the years pass, Vivian starts to record her worries, her dissatisfactions, and the temptation of taking a lover. Her musings are interrupted by remarks she finds in an untitled book by the Indian guru Kharjappalli. (Sample piece of wisdom: “God also doubts your existence.”) The couple’s lives form the outline of an Antonioni film.

Léon is making a record too. He’s wielding the Daddycam as he documents all those vacations and breakfasts and views of Manhattan, Hawaii, Las Vegas, and aqueducts. Vivian has misgivings (“If you film, you don’t have to live”) but learns to use the camera herself, and even steer the yacht.

Finally there is an exceptionally discreet effects track. The home-movie scenes are eerily silent because there’s no voice-over, but occasional noises are dubbed in, and very rarely there’s a snatch of music. On the whole, the absence of musical cues for emotion renders the pictures and the diary texts all the more powerful. (Compare the emotional tug of Jóhannsson’s score for Last and First Men, a film that also “overwrites” mysterious visuals with a text sourced to a woman.) The result is a dry, unsentimental treatment of a crumbling marriage in the midst of Europe’s postwar boom.

Out of 29 hours of found footage Nuria Giménez and her colleagues have fashioned a fascinating film that is at once pure documentary and creative fiction. I like to think of it as another way to assemble a narrative–at one level simple chronology of a cosmopolitan couple’s life, on another the hidden story of voyages to Italy and elsewhere. I kept seeing the ghosts of Bergman and Sanders in this couple on the modern Grand Tour.

I knew about none of these films before encountering them at VIFF, which is of course one reason we cherish this and all other festivals. Granted, there’s reassuring pleasure in seeing the latest accomplishments of established and esteemed old hands (here Ozon, Petzold, Vinterberg, Rasoulof et al.). Just as valuable, though, is the jolt of seeing newcomers present beguiling variants on familiar traditions. Three of these films, as far as I can tell, are first features, and they offer fresh takes on stories we thought we’d seen before.

All are graced with sharp cinematic intelligence and offer pointed commentary on lives lived now and back then, close to home or far away. All remind me of why this VIFF wing is called Panorama. Every movie widened my vision.

Thanks, as usual, to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival. Thanks as well to programmer and consultant Shelly Kraicer for background on Memories to Choke On.

You can sample the films in their trailers: Tales of the Lockdown is here; Memories to Choke On is here; Sarita is here; and a particularly shrewd one for My Mexican Bretzel is here (incorporating, I think, footage not in the film). Giménez’s film won the Found Footage Award at Rotterdam. If you insist on knowing about how her film was made before seeing it, you can check this Film at Lincoln Center interview.

I hope other festivals, and streaming services, and even theatres will pick up all these films for wide distribution.

My Mexican Bretzel (2019).

The poet of dynamic immobility: Ennio Morricone: A guest post by Jeff Smith

Ennio Morricone holding his principal instrument, the trumpet, in a picture taken in the 1970s. Photo by Roberto Masotti.

DB here: For our blog entry #1001, who better to memorialize Morricone than our stalwart collaborator Jeff Smith? He has provided many music-sensitive analyses of films both recent and classic. Our most popular entries from last year were his two looks (here and here) at the music and musical culture behind Once Upon a Time. . . . in Hollywood. Herewith his warm appreciation of a maestro.

Jeff here:

On July 6, 2020, the legendary composer Ennio Morricone passed away in Rome at the age of 91. As expected, several encomia were published reflecting upon Morricone’s musical genius. Of particular note were reflections by two writers for Variety, film critic Owen Gleiberman and film music historian Jon Burlingame.

The tributes highlighted many notable features of Morricone’s film work: his gift for melody, his sense of humor, his eclecticism, and his amazing productivity. Having written more than 500 film and television scores, Morricone’s compositional output was jaw-dropping. After all, even Josef Haydn wrote only 106 symphonies.

Throughout my own career as a film scholar, I frequently engaged with Morricone’s music. In preparation for the writing of my dissertation, I did an independent study with David on Hollywood film music. My final project? A detailed analysis of the score for Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, complete with handwritten transcriptions of every musical theme and motif I could identify.

I vividly remember the satisfaction I felt in being able to play the main title from start to finish on the piano. It is one thing to read music and play it. It is another to take what you hear and try to put it in some reproducible form on paper. Playing back Morricone’s famous theme, I felt I’d gained insight into the mind of the great composer. That work eventually became the basis for chapter six in my first book, The Sounds of Commerce.

My fascination with Morricone’s work has continued to the present day. Last summer, I wrote a review of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, a book of interviews conducted by Alessandro De Rosa. This past April the Criterion Channel posted my most recent “Observations on Film Art,” which examines musical motifs in Morricone’s score for The Battle of Algiers.

That’s close to thirty years of near-obsessive fascination with Morricone’s music and his compositional style. In what follows, I share some additional thoughts on the Maestro’s legacy, offering some insight on the reasons for his seemingly inexhaustible creativity.

The Sicilian defense

The first section of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words is all about the maestro’s love of chess. Although the composer would describe himself as a hobbyist, his chess skills surpassed those of most amateurs. Morricone played against Boris Spassky, Garry Kasparov, and other Grand Masters. When asked about his passion for the game, Morricone explains that he sees important parallels between music composition and chess. Both activities involve mathematical relations. These relations are further expressed in axes of verticality, horizontality, and graphics.

This initial discussion of chess struck me as a key to understanding Morricone’s creative process. The game of chess is often analogized as a battle where stratagems and tactics are deployed in an effort to outmaneuver – and thus, defeat – one’s opponent. That comparison undoubtedly rings true. Yet when one looks at the board before the game starts, it also represents something simpler: a field of open possibilities. Not every move is permissible, of course. But when you consider possible combinations of moves, the permutations can number in the millions. And even though the rules of chess constrain the patterns of moves that can be made, all of these possibilities are generated by the dispositions of up to 32 pieces on a field of 64 squares.

Morricone seems to approach the blank space of staff paper as though it were a chessboard at the start of the game. A chess player works with sixteen pieces that can be used in various combinations. A composer works with the twelve tones of the chromatic scale to create intervals and chords. As with the chessboard, there are millions of different permutations in the way these twelve tones can be arranged. More importantly, since each note in the scale can be varied by pitch class, duration, articulation, dynamics, and instrumental color, the options seem endless.

Yet while the “terror of the white page” can be an obstacle to the creative process, that has never appeared to be the case with Morricone. Why? I think it is because the composer found a method of composition that reduced the apparently infinite possibilities to the level of the merely multitudinous.

In Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, the composer characterized himself as a student of the Second School of Vienna. Unlike Arnold Schoenberg and Anton Webern, who were part of the first Viennese School, Morricone tried to transpose the former’s twelve-tone technique into a seven-tone system while retaining the latter’s commitment to the rules of serialism that ordered all other musical parameters. For Morricone, this system had the advantage of enabling him to write tonal music without having to slavishly adhere to its characteristic tensions and resolutions. By adopting Webern’s principles of serialism, the notes, according to Morricone, “are freed from their reciprocal constraints.”

Over time, Morricone learned how to adapt this simplified version of twelve-tone serialism to the needs of each film score he wrote. In some cases, he would work within a pentatonic system. In others, he might base his compositions on a row of six or eight tones. In still others, he might jettison the system altogether.

This simplified serial technique provided Morricone with a compositional framework that was extraordinarily generative. Once the composer has determined the tone row and the ordering of other musical parameters, he simply spins off hundreds of variations that are then fitted to the film’s dramatic situations. The smaller tone row still acts as a guarantor of harmonic unity. Morricone describes it as the music’s DNA, something like an identifying marker in every musical “cell.” Specific changes in rhythm, tempo, orchestration, volume, and tessitura all provide means of refreshing the basic musical schema.

Indeed, Morricone’s compositional system proved so procreant that he sometimes wrote three or four versions of a score’s theme in order to give the director some options to choose from. In Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, he offers an example with the police triumph theme in The Untouchables. The theme was the last one written for the score, and Morricone prepared three pieces that were recorded with two pianists. He then sent them off for director Brian De Palma’s consideration. De Palma didn’t like any of them. Back to the drawing board,

Morricone wrote three more pieces and shared them with De Palma. In a phone call, the director told Morricone that he still wasn’t convinced. Morricone completed three additional pieces and sent them. This time, though, he included a brief that summarized the strengths and weaknesses of all nine proposals. Morricone himself recommended against variant number six, claiming it was most triumphant and therefore the least convincing. Concluding his story, Morricone asks, “Guess which one he chose?”

After I sniggered at the composer’s dig at De Palma’s musical sensibilities, the larger implications of Morricone’s anecdote began to sink in. My mind was well and truly blown. If Morricone had written eight other themes in lieu of the one that was ultimately chosen, how much music had he actually written for The Untouchables? And if this, as Morricone indicates, was not an isolated case, how many unused cues are likely sitting in boxes somewhere in Rome simply waiting to be discovered? As noted earlier, Morricone had written music for more than five hundred films and television shows. Were the aggregated number of unused cues and alternate versions of themes the equivalent of another one or two hundred scores? And if we trust Morricone’s judgment, some of these versions are actually better than the ones we already know.

All of this is a reminder that Morricone’s output is astonishing. This is evident both in terms of the size of his corpus and the sustained quality of his work over a period of almost sixty years.

Much of that productivity, I think, was fueled by Morricone’s transposition of serialist concepts to the film score. Like the rules of chess, which prohibit certain moves, Morricone’s use of simplified tone rows gave him a set of “rules” that fruitfully limited certain options in terms of melody and harmony, but still preserved the usual range of choices for other musical parameters. It also shaped our sense of Morricone’s style by favoring certain compositional devices over others. Pedal points and ostinati are completely permissible in Morricone’s system. But a rapid chromatic run of the type used in classical Hollywood “hurries” would be out of bounds.

Such a rapid chromatic run is also ill-suited to Morricone’s aesthetic for another reason; it is a musical gesture that implies directional movement. Instead Morricone strives to produce a sensation of “dynamic immobility” in his work, the musical equivalent of the swirls, eddies, and ripples we associate with lake water. The sense of immobility derives from Morricone’s interest in writing tonal music outside of the strict rules governing the Western tonal system. One hears chord changes. But you couldn’t describe any particular change as a modulation insofar as there is no definite key to ground these harmonic relations. Consequently, you discern harmonic change, but without the sense of teleological movement toward a cadence as a definite endpoint.

If Morricone’s approach to harmony strives for a feeling of moving stasis, what then accounts for the music’s dynamism? For Morricone, it is the constant change evident in the other musical parameters: texture, pitch, dynamics, and timbre.

Listen again to the cue from The Untouchables. Do you notice the sorts of surges and swells produced by its chord changes? Does it sound like it moves to a definite endpoint? Or does one instead get the feeling of an endlessly deferred resolution? If those surges and swells produce the latter, that’s Morricone’s “dynamic immobility” in situ.

Morricone’s creative spark seems all the more remarkable when one considers that he worked in a production environment guided by the notion that “I don’t need it good; I need it Tuesday.” That Morricone flourished within this milieu for more than five decades eventually made him “untouchable.”

Roll over Beethoven and tell Tchaikovsky the news

A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

In The Sounds of Commerce, I argued that the 1960s proved to be an important period in the history of the Hollywood film score as the dominance of its neoromantic style began to wane. Driven partly by the popularity of theme songs and soundtrack albums, composers infused the classical Hollywood score with elements of both jazz and pop music. To be sure, those styles all had their place in Hollywood films. Characters performed Tin Pan Alley songs in musicals. Dance bands played jazz as part of the nightlife featured in gangster films and films noirs. And one even heard the occasional bit of Gershwin-style orchestral jazz pop up in a score. The changes I discerned in sixties film scores were more a matter of degree than of kind.

What prompted the change? Besides the emergence of new ancillary markets for film music, Hollywood also saw a generational shift take place throughout the industry, including film composers. Sadly, some of the greatest proponents of the classical Hollywood style, such as Herbert Stothart, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, and Victor Young, were dead before 1960. Others, like Roy Webb, Max Steiner, and Miklós Rózsa, remained active, but they saw fewer assignments come their way.

Taking their place was a new breed more attuned to changes in the jazz and pop idioms. Instead of aping Gershwin, these new composers were more likely to draw upon swing music or West Coast jazz. Similarly, several film composers also began to incorporate elements of pop music’s newest sensation: rock and roll. In an interview I did with Henry Mancini, he described his famous “Peter Gunn” theme as a rock tune due to its “straight eight” rhythms and its twangy guitar line. Not coincidentally, John Barry’s arrangement of the James Bond theme foregrounded Vic Flick’s guitar in a similar way. The middle section of the tune features a swinging, Dizzy Gillespie-ish break. But that guitar sound stood out, much closer to Carl Perkins than to Wes Montgomery.

During the 1960s, no film composer was as thoroughly steeped in the rock idiom as Ennio Morricone. Yet, unlike Mancini and Barry, who were drawn toward rockabilly in their use of electric guitar, Morricone cribbed from the slightly more modern sounds of early sixties surf-rock. Morricone tells Alessandro De Rosa that he used the electric guitar long before he wrote the scores of his spaghetti Westerns, albeit not as a solo instrument. Yet he opted to feature the electric guitar in the main theme of A Fistful of Dollars because he liked “its tough and sharp timbre,” which he felt was perfect for the atmosphere of the film.

De Rosa also notes that the Shadows’ surf music was extremely popular on Italian record charts in the early sixties, especially their Western-themed classic “Apache.” The distinctive twang of Hank Marvin’s Fender Stratocaster was widely imitated by Italian beat bands. By the time A Fistful of Dollars was in production, the Shadows’ influence had seeped into Italian popular music culture. When they topped the Italian charts in 1963 with “Geronimo,” another paean to the American west, it probably seemed quite natural to make the Stratocaster’s sound the centerpiece of Leone’s groundbreaking film.

Morricone made the electric guitar the star of many more spaghetti Western scores. But none so prominently as the “Man With the Harmonica” theme of Once Upon a Time in the West. Famously, the film features no main title in the opening credits, “scoring” the scene instead with the sounds of the wind, a creaking mill, the clanging of a metal gate, and an especially persistent horsefly (among other things). Morricone’s score doesn’t come into Leone’s film until about the twenty-minute mark. But when it does it makes quite an entrance.

Frank and his gang have just slaughtered the McBain family. The only survivor is a red-headed boy who comes running out of the house after hearing gunshots. As he comes into a close-up, Bruno Battisti D’Amario’s guitar starts blasting through the theater speakers. The sound is loud and distorted, cutting through the silence like an axe through a chicken’s neck.

In his instructions to D’Amario, Morricone insisted that the theme was meant to “wound the audience’s ears like a blade” the first time we hear it. As a coup de théâtre, it is brutally effective. I’ve seen it more than twenty times, and the moment never fails to give me chills. Here we see Morricone experimenting with the timbre of the guitar by heightening the effects of high volume and high voltage to overdrive the power valves of the amplifier. The effect was such that some critics even described Morricone’s score for Once Upon a Time in the West as a sort of “post-Hendrix” rock. The comparison was undoubtedly flattering. No musician had done more to explore the timbral possibilities of the electric guitar than Jimi Hendrix.

Morricone experimented in other ways that seemed to merge elements of avant-garde classical music with more vernacular forms. Consider his “Harmonica” motif in Once Upon a Time in the West alongside Henry Mancini’s main title for Wait Until Dark, which was released about a year before Leone’s epic. Both film scores explore microtonal effects, albeit in quite different ways.

In Mancini’s case, he asked the studio to give him two pianos that were tuned a quarter tone apart. He then asked his two performers to play the chords of an accompaniment figure in rapid succession.

The dissonance produced through this effect is unlike any produced in atonal writing. There the composer deliberately emphasizes intervals that create a sense of disharmony, such as minor seconds, major sevenths, and tritones. Yet Mancini’s microtonal experiment does something else entirely. Our ears tell us we should be hearing the same chord, but the repetition on the detuned pianos sounds a bit off. Mancini’s score evokes a kind of dislocation well suited to Wait Until Dark’s generic trappings as a psychological thriller. The effects, though, were even more pronounced for the two pianists who played on the main title. Pearl Kaufman and Jimmy Rowles both reported having to take frequent breaks during the recording sessions. The sort of “swimming” effect produced by the detuned pianos gave them a feeling of vertigo and nausea commonly found in motion sickness.

Morricone’s approach to microtonal harmonies proves to be much more elemental: the wavering sounds of two notes played on the harmonica, ostensibly a half step apart. Anyone who has played a harmonica knows it requires great breath control. Inhale and you make one pitch. Exhale and you make another. Beyond that, skilled performers can also bend pitch on a harmonica by changing their embouchure. Harmonica players can also use their hands as dampers, altering the sound in much the same way a wah-wah mute alters the tone of a trumpet.

All of these techniques give the harmonica player a number of means to bend pitch. Morricone takes full advantage of them with the “Harmonica” motif in Once Upon a Time in the West.

Listening to this passage, one can hear how Franco De Gemini’s mouth harp straddles the fence between sounding bluesy and sounding strident. Morricone viewed the half-step relation in the motif as a key element in building musical tension since it is heard in the flashback that explains Harmonica’s life-long quest for revenge. Yet De Gemini’s subtly wavering pitch seems to capture the full range of microinterval variants that fall between the D# and E that comprise the last two notes of the motif.

Both composers’ explorations of microtonal effects prove effective. But the precision of the quarter tone difference in Mancini’s detuned pianos gives the music a mechanistic quality that seems cold and brittle. By contrast, the harmonica’s fluid pitch-bending in Once Upon a Time in the West is looser, freer, more improvisatory – all of which fits the types of vernacular music played on harmonica.

This effect was enhanced by Morricone’s recording techniques. He first recorded the orchestra and then recorded De Gemini’s harmonic track individually. Although the latter recording was less precise, Morricone said that “the tension generated by the performance made his harmonica float over the orchestra. Now on the beat, then behind it, this time ahead….in short, it was almost as though it was fluctuating.”

Morricone’s compositional and recording techniques in Once Upon a Time in the West might seem less daring than Mancini’s more avant-garde experiment in Wait Until Dark. Yet Morricone’s music gains something in its more organic placement within Leone’s film. The harmonica’s wavering pitch is akin to the sorts of portamenti and string-bending frequently heard from saxophones, guitars, and basses in a multitude of rock and roll songs produced throughout the idiom’s history. And the harmonica as an object has long been a common feature of the Western’s iconography. In this way, Morricone’s experimentation is grounded in the dramatic, stylistic, and symbolic structures of Leone’s epic.

A horse of a different tone color

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966).

Unquestionably, Morricone’s most audible innovations came through his approach to orchestration. As nearly every obituary noted, his unusual combinations of instruments became a hallmark of the Morricone sound. In a summary of the signature elements found in the score for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, The Economist declared:

And then there is the freewheeling range of sounds with which he chose to make that music: the whistling, the yodeling, the gunfire and the squeaky ocarina, an ancient Italian wind instrument that looks like a sweet potato and is better known to a younger generation as the soundtrack of a Nintendo video game.

As I suggested above, Morricone was part of a cohort that moved outside the neo-Romantic style of film composition associated with the studio era. Unconventional orchestrations were an important part of that push.

Several factors provided impetus for this change. One was the embrace of jazz and pop styles. Incorporating those elements often meant writing for the instruments typically associated with those idioms. Mancini, John Barry, Frank De Vol, and Nelson Riddle all were prominent exponents of this approach during the 1960s. Indeed, many of Mancini’s orchestrations simply add strings to the usual forces of a jazz big band.

A second factor was the breakdown of the studio system in the 1950s. The majors’ retrenchment saw them making fewer films and reducing their overhead costs. They sold off parts of their backlots and leased their soundstages to independent producers or television crews. They also tried to shed labor costs, including those associated with maintaining an in-house orchestra.

This was bad news for musicians, who suddenly found themselves working in a gig economy as independent contractors. But it was good news for composers who now could write music for something other than a standard chamber orchestra. (During the Golden Age, studio bosses would sometimes chafe at the notion of hiring extra musicians, since they were already keeping as many as fifty regularly on call.)

With more flexible options when it came to musical labor, composers began to experiment with more unusual combinations. Whereas the typical studio orchestra employed one or two keyboardists, Bernard Herrmann arranged one cue in Journey to the Center of the Earth for nine organs. Three organists played electronic organs and one played a cathedral organ.

In many ways, Herrmann’s experiments with orchestration provide an interesting foil for Morricone’s own flights of fancy. For two of the scores Herrmann wrote for Alfred Hitchcock, he self-consciously limited his palette to the sounds of a single section of the orchestra. On Psycho, Herrmann wrote only for strings, claiming that the more monochrome sound was fitting for a black and white film. Yet, within that uniformity, Herrmann wrought an extraordinary range of subtle differences in timbre through the use of pizzicato, mutes, and unusual bowing techniques. The famous bird shrieks produced by the violins during the shower murder recall the avant-primitivism of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. But Herrmann achieved this effect only with strings rather than a full orchestra.

Herrmann did something similar in his unused score for Torn Curtain, which was written for sixteen French horns, nine trombones, two tubas, twelve flutes, two sets of timpani, eight cellos, and eight basses. For Torn Curtain, Herrmann’s restriction of his palette was inspired by the setting rather than the cinematography. By emphasizing the low brass and lower-pitched strings, the composer sought to find a sonic equivalent to the drab cheerlessness of life behind the Iron Curtain. Alas, Hitchcock rejected the score under pressure from Universal to produce a saleable music tie-in. The studio wanted something like the Beatles. What they got from Herrmann was more like John Philip Sousa on an acid trip.

If Herrmann’s orchestrations were the musical equivalent of a Mark Rothko painting, exploring a range of subtle shadings within a single color, Morricone’s were closer to the collage principles of Robert Rauschenberg. Just as Rauschenberg’s work juxtaposed unconventional materials and objects within a single canvas, Morricone enjoyed the wild, discordant collisions that could come by combining oddball instruments with one another. The composer is often described as a postmodernist because of his “everything but the kitchen sink” approach to orchestration. No doubt this is one of the reasons his work was so appealing to “downtown” musical avant-gardists like John Zorn.

Consider, for example, the way Morricone uses vocal textures throughout his score for The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. It features Edda Dell’Orso’s gorgeous soprano, natch. But it also features a variety of other vocal sounds, some of which border on the “unmusical.” These include the famous “coyote incipit” that has become something of a meme for the spaghetti Western more generally.

There are also plenty of other chants, grunts, and yelps that add their flavors to the musical stew. Morricone even had his singers vocalize through various trumpet mutes to produce the “wah-wah-wah” that is a motivic counterpart to the coyote incipit.

Morricone also made marvelous use of library effects to incorporate the sonic iconography of the Western into his score. We hear gunfire, whipcracks, and ricocheting bullets as elements of rhythmic punctuation throughout the music of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. (Since cowboy yells and whipcracks both appear in the opening theme of Rawhide, perhaps both of these tactics are a sly reference to star Clint Eastwood’s television career.) Even these audacious touches are supplemented by simple, but effective solutions to musical problems. In need of a rhythmic pulse underneath the melody, Morricone coaxed Bruno D’Amario to tap the pickup on his electric guitar.

All of this suggests something very Cagean in Morricone’s approach to orchestration. It is though he took the idea of Cage’s “prepared piano” in which different objects could be laid on the strings of piano’s soundboard, and applied it to the full orchestra.

What is the sound of one wing flapping?

The Mission (1986).

Although Morricone’s spaghetti Western scores displayed his boldest experiments in orchestration, his interest in unusual sonorities continued throughout his career. Some choices are a bit more conventional than others. But they always strike me as inherently right. The oboe seems like a fairly idiosyncratic instrument for an 18th-century Jesuit missionary. Surprisingly, though, its melancholic yet dulcet melismas are a perfect complement to the big sound of The Mission’s double chorus, the latter itself inspired by the luminous sacred music of Palestrina.

Or think of Morricone’s use of the panpipe. He seems attracted to its airy timbre, using it in several scores throughout his career. Yet, comparing its appearance in both Once Upon a Time in America and Casualties of War shows that the panpipe’s sound resists any easy associations. In Leone’s gangster epic, the panpipe is introduced in “Cockeye’s Theme” in a scene where Noodles buys a one-way ticket to Buffalo. After completing his purchase, his attention is drawn to a large poster encouraging tourists to visit Coney Island. The music suggests Noodles’ memories of childhood and his grief after hearing the news that his three childhood friends all died in a battle with federal agents.

It comes back, though, at the moment when Dominic is killed by Bugsy, a rival gang member. As Morricone noted, Leone identified this scene “as a definite point of no return in the story, the watershed marking the end of youth.”

In contrast, for De Palma’s combat film, Morricone used two panpipes in the theme he wrote for the young Vietnamese woman who is abducted, raped, and killed by US soldiers. Here the motivation was something that struck Morricone in the staging of her death.

She buckles her legs like a dying bird, before tumbling down from the high ground. I imagined a theme based on just a few notes for two panpipes, which by ping-ponging their sound, evoke the slowing fluttering of a bird’s wings shortly before death.

At first blush, Morricone’s description of the scene sounds like “Mickey-Mousing” where the music accents a character’s actions, movements, or gestures. But what Morricone actually gives us turns out to be much more sophisticated. A classical Hollywood composer like Max Steiner might have caught the girl’s collapse through a downward glissando or a rapid, descending scale run. Instead Morricone gives us a different musical gesture – the alternation of two notes on the panpipe – to suggest an action not visible onscreen: a dying bird’s fluttering wings.

As is evident in the clip, we hear the two panpipes play over the image of the young woman’s broken body. Yet Morricone associatively links it to the birdlike movement seen about a minute earlier: the buckling of her knees as she falls.

A moment such as this one nicely captures Morricone’s gift for storytelling. Many of Morricone’s fans treat his scores as absolute music, often listening to them repeatedly without ever watching the films they accompany. But Morricone also had a gift for translating a film’s larger themes and meanings into musical forms.

Morricone achieved fame for his beautiful melodies, rich harmonies, and surprising orchestrations. None of that would be very meaningful, though, if these elements weren’t firmly rooted in the composer’s extraordinary dramatic sense.

The greatest?

The Hateful Eight (2015).

At the end of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words, Alessandro De Rosa asks the composer if there was a specific moment when he realized he’d become one of the greatest, most influential composers of the century. Morricone gets flustered by the question, claiming such judgments are premature. In music, it takes hundreds of years to determine whether one’s work endures. He then adds a polite, but banal conclusion, saying it is wonderful to be appreciated and even better to have one’s music reach so many people.

Still disarmed by the question, Morricone continues hesitatingly:

The greatest of the century? It is difficult to reply….Oh dear…. where did you hear this?

De Rosa responds, “It was just to provoke your vanity…” Acknowledging the trap set before him, Morricone smiles and replies, “You don’t say….I figured!”

Morricone’s humility might be a tacit recognition that he’s had the great fortune to write music for the movies–one of the greatest engines for pleasure that the world has ever seen. A great film surely benefits from a great score. Yet it can seem that the composer is just along for the ride.

Still, Morricone understood that his music was often better than the films it accompanied. As he well knew, fortune gives with one hand and takes with the other. Morricone wrote music for masterpieces like Days of Heaven. He also worked on schlockfests like The Exorcist II: The Heretic.

Perhaps more than other craft positions, the lot of a film composer can seem unique. Music exists as its own formal system. But film scores are always written in the service of something else and judged accordingly. Directors often hope in vain that a composer can salvage a bad scene. Yet composers themselves will say they’re not miracle workers. And even when the score can stand on its own, some pugnacious critic will ask, “Should it?”

When I was doing the initial research for my dissertation during the early nineties, I recall some film music critics dividing the field into craft workers and stylists. The paradigm case for the former was a composer like Jerry Goldsmith, who subordinated his personality to the dramatic requirements of the work. Goldsmith could write a bittersweet jazz melody for Chinatown, a stirring horn call for the war epic Patton, cartoonish “Mickey-mousing” for the comic fantasy Gremlins, and outré dodecaphonic themes for sci-fi adventures like Planet of the Apes and Alien. Binge-watch all five films and it would seem hard to believe the music was all the work of a single person.

Stylists, on the other hand, were composers who had created such a distinctive sound that their music could not be mistaken for that of another. All three of the composers featured in my book seemed to fit that rubric – Henry Mancini, John Barry, and Ennio Morricone – a factor that likely contributed to the popularity of their scores in ancillary markets.

Looking back almost thirty years later, the label of stylist fits the work of Mancini and Barry quite well. In fact, I have anecdotal proof of the latter in my first viewing of Michael Apted’s espionage thriller Enigma. Halfway through film, I wondered to myself who had written the score since it sounded a lot like John Barry. Checking the poster afterward, my hunch was confirmed; it was John Barry!

For Morricone, though, the “stylist” label seems misapplied. At the time, this was due to the fact that he was so strongly associated with the spaghetti Western. He had written music for more than thirty films in the cycle and had come to define it in the public imagination. It is telling that the scores written for other spaghetti Westerns by Luis Bacalov or Riz Ortolani sound like Morricone facsimiles.

Identifying Morricone so closely with the spaghetti Western, though, ignores the inspired music he wrote for so many other genres: horror films, gangster films, thrillers, historical epics, political satires, and even the occasional romantic drama.

Take five Morricone classics not so randomly selected: Teorema, Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, Cinema Paradiso, Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, and The Hateful Eight. Could any other composer have written the notes that we hear? Probably not. They all seem to bear the distinctive Morricone signature. Yet they are also so unlike one another that it seems unfair to suggest that he didn’t mold his sound to the specific needs of each film. For Morricone, we have to throw out the “either/or” implied by the rubric. He’s both a craft worker and a stylist.

If that seems like a copout on my part, it’s one I will happily embrace. For me, like many others evaluating Morricone’s legacy after his death, his music is both cerebral and visceral. It warms the heart and tickles the brain, sometimes simultaneously. And that seems rare for much 20th-century concert music, which even at its best, can feel quite cold and analytical.

Thirty years later, Morricone’s music still enthralls me in a way that’s unlike that of any other film composer, especially when the score is heard coming from the big screen. I’ve had the great pleasure of screening a 35mm print of The Untouchables the past two years. Hearing Morricone’s main title played back in Dolby Stereo with a proper subwoofer, I still get goosebumps. I even anticipate the massive bass drum hit that punctuates the rhythms played by brushes on the snare. If the stinging guitar chord that introduces Frank was intended to sound like a stab, that bass drum sound is the musical equivalent of a gut-punch.

Ciao, Maestro! You will be missed. Yet your music will live on, perhaps even for centuries. For my part, you’ve given me hundreds of joyful moments at the cinema and a lifetime of wonderful memories.

Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words can be found here. If you want to learn more about his music, this is a great place to start. It includes reproductions of Morricone’s handwritten musical notation. It also includes a thorough survey of both Morricone’s film scores and his concert works.

My review of Ennio Morricone: In His Own Words is here. A brief discussion of Morricone’s score for The Hateful Eight can be found in my 2016 Oscar preview. Incidentally, Tarantino used Bernard Herrmann’s rejected score for Torn Curtain for the excerpt from Rick Dalton’s action film The 14 Fists of McCluskey in Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood. The cue can be found here and the scene from Tarantino’s film is here.

My chapter on Morricone’s spaghetti Western scores can be found in The Sounds of Commerce.

Henry Mancini discusses his score for Wait Until Dark in his autobiography, Did They Mention the Music? Bernard Herrmann’s score for Psycho has been analyzed by several film music scholars. Among the best is Fred Steiner’s “Bernard Herrmann’s ‘Black-and-White’ Music for Hitchcock’s Psycho,” anthologized in Elmer Bernstein’s Film Music Notebook: A Complete Collection of the Quarterly Journal, 1974-1978. Details of Herrmann’s orchestrations for his rejected score for Torn Curtain can be found in the liner notes of conductor Joel McNeely’s recording. They’ve been posted here.

The chess portrait above is by Riccardo Musacchio.

Morricone waits backstage at a 2010 concert of his work at the Royal Albert Hall in London. Photo by Roberto Musacchio.