Archive for January 2010

Paris-Berlin-Brussels express

Doktor Satansohn.

Our trip to Europe has come to an end, and so we finish with a post scanning some highlights.

The magic lantern learns new tricks

DB here:

What am I seeing? Many avant-garde films pose this question. Mainstream fiction film and documentary cinema have mostly relied on the idea that the image should be recognizable as “what it is.” But one strain of experimental film has worked to delay or even prevent us from making out what’s in front of the camera.

Sometimes we lose our bearings only briefly, as when we eventually identify pot lids in Ballet Mécanique or bits of sunlit linoleum in Brakhage films. Sometimes language points out what’s really there. The titles of Joris Ivens’ Rain and the Eames’ Blacktop: The Washing of a School Play Yard allow us to enjoy the ways that ordinary sights can yield unexpected abstraction. Sometimes we toggle back and forth, as when in Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son recognizable human figures, however grainy, jump into sheer blotchiness and then back into something like legibility. But other times we can’t ever tell what we’re seeing. Brakhage’s Fire of Waters offers one of the best examples I know, with its jagged bursts of light in a smoky void.

What am I seeing? The uncertainty was doubled during my visit to Ken Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern performance at the Cinémathèque Française. I say “doubled” because at least with Fire of Waters and Tom, Tom I knew I was watching a film. With this display, What am I seeing? started as a question about the format itself. Was it a film, a video, or something else?

Then the question became the customary one. Off-white textures—pebbly, dribbly, stalagmite-like—swim in and out of focus. Some are viscous and globular, some are like tangled foliage. They seem to spiral, but actually (I put up a finger to measure) they barely move. The effect of movement is given by pulsations of pure black, breaking the lyrical effect of the surfaces with a harshness that becomes aggressive. Aggressive as well is the soundtrack, blocks of sound from subway platforms and traffic and kitsch Latin percussion, all played at high volume. The surfaces just keep shifting and not shifting, sort of rotating while jabbing out at us, lovely and anxiety-inducing at the same time.

At the end of the performance, people crowded around the cardboard booth in the middle of the theatre. As Ken and Flo Jacobs packed up, they showed how they had generated the effects. What had I been seeing? Neither a film nor a video but a true magic-lantern display, assembled on the spot. But what had I been seeing? Something created with home-made equipment of a startling simplicity. (Strapping tape was involved.) Our magicians explained their tricks, like magic-lantern operators of earlier centuries explaining the science behind their shows. But I think it’s best that you not know until after you have a chance to see what they create.

In earlier entries (here and here) Kristin and I have praised Jacobs’ films for showing how very slight adjustments in technique or technology can create disturbing cinematic illusions. In this vein, the first item on the Cinémathèque program, a video called Gift of Fire, turned Louis Le Prince’s brief 1888 street scene into a 3D movie. (The homage was appropriate because Le Prince experimented with multiple-lens cameras.) The Nervous Magic Lantern performance generated a different sort of illusion, one conjuring up micro-landscapes and otherworldly vortices. In all, Jacobs makes us realize how many evocative effects are still to be discovered by tinkering with images thrown on a screen.

Detour to Berlin

KT here:

As David mentioned in last week’s entry, I took a week in the middle of our visit to Europe for research at the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin. The staff there welcomed me into their storerooms, and I spent the days looking at fragments and the records of their discovery and the nights downloading and backing up my photos. No time for filmgoing. The most I managed was a trip to the well-stocked arts bookshop Bücherbogen, which has one of the best selections of film books to be found in Germany. Our old friend, experimental filmmaker Carlos Bustamente, met me there, and we had a quick cup of tea–most welcome on a cold morning when the results of the biggest snowfall in decades were still blanketing many sidewalks and roads.

I did note one film-related phenomenon, however. Every day I took the S-Bahn from Savignyplatz to Friedrichstrasse. The tracks pass directly across the street from the Theater des Westens (that is, the western part of Berlin). It was playing Der Schuh des Manitu, a musical version of the  highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

By now it’s a familiar phenomenon in the U.S. for successful Hollywood films to be turned into stage musicals. It wasn’t always so. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, films were made of popular musicals, sometimes successfully, as with My Fair Lady, and sometimes not, as with Mame. But now the trend is the other way, with everything from Shrek to Hairspray getting the Broadway treatment.

It’s interesting to know that the same thing goes on abroad, though I’m not sure how prevalent such adaptations are. Der Schuh des Manitu, directed by Michael “Bully” Herbig, remains the highest grossing German film. Herbig doesn’t act in the stage play, as he did in the film, but he served as a creative advisor. The musical is a hit, having premiered on December 7, 2008 and it is expected to continue until at least the autumn of this year. There are several clips from both the film and the musical on YouTube. This one, at 8 minutes, gives a generous dose of the show. There are no subtitles.

I had only a couple of days back in Paris before we headed for Brussels for the final week of our trip. The German theme continued, since a few of the 1910s films David needed to see at the Cinematek here were German. The one I most wanted to see was Edmund Edel’s 1916 feature, Doktor Satansohn. Its main claim to fame is probably the fact that Ernst Lubitsch plays the title role. My book with Lubitsch started with his 1918 move to features, when he began to concentrate more on directing and less on acting. By 1920, with Sumurun, he appeared onscreen for the last time; being discontented with his performance as the tragic clown, he decided it was time to move behind the camera for good.

In the short films he starred in before 1918, Lubitsch often played a brash, ambitious Jewish youth, as in Der Stoltz der Firma (“The Pride of the Firm,” 1914). In Doktor Satansohn he’s a physician with a magical machine that transforms older women into beautiful young ones. We’re first introduced to a couple and the wife’s mother. When the latter makes a pass at her son-in-law and is rejected, she seeks the doctor’s help. His machine works by capturing the wife’s essence in a statuette and making the mother look like her daughter. Problem is, every time she’s about to kiss the husband, the doctor pops up with his devilish leer, visible only to the “wife.” David and I decided that the film is a comedy, though perhaps one only Germans of the day would find truly amusing. For one thing, the title character is clearly a Jewish caricature, one played to the hilt by Lubitsch. He decorates his machine with the Star of David and a Hebrew inscription (not to mention vipers and an image of Saturn).

Stylistically it’s a fairly conventional film for its day, though the black background of the doctor’s office, with its stylized youth machine and satyr-like bust, gives a hint of Expressionism to come. (See our topmost image.) Inevitably near the end there comes the moment beloved of historians of pre-World War II German cinema. The real daughter, released from her imprisonment in the statuette, confronts her double in the doctor’s waiting room. The Doppelgänger motif strikes again.

I wonder if German films actually have more Doppelgängers in them than appear in other national cinemas. Do they really reflect the disturbed soul of the nation? Or did the possibilities of filmic special effects draw moviemakers to try and multiply single figures? Georges Méliès and Buster Keaton used in-camera techniques to multiple their own figures in virtuoso displays. I recall being impressed by The Parent Trap‘s duplication of Hayley Mills when I saw it as a kid, and the whole notion of a single actor playing twins and other lookalike relations is a common enough convention. In Doktor Satanssohn, the doubled figure appears only in this one shot, and it’s the leering Lubitsch, delighted with his own nastiness, who walks off with the picture.

The 1910s, again, and still

DB again:

We saw Doktor Satansohn while I was studying staging and cutting strategies of the 1910s, thanks to the remarkable holdings of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, also known as the Cinematek. My comments on last summer’s visit are here.

Another German film, in a choppy Russian print, vouchsafed a new glimpse of Asta Nielsen. In Totentanz (Urban Gad, 1912), she plays a guitarist-dancer who must take to the stage to support her infirm husband. She attracts the devotion of a composer, and soon she feels attracted to him. Torn between desire and duty, she snaps during a rehearsal of his latest piece, “Totentanz.” In a chilling gesture, she uses his dagger to slice her lute strings.

Soon the two are locked in a violent erotic struggle, and a stabbing ensues. In all, melodrama as ripe as one could want.

As ever, I was happy to have my hypotheses about tableau staging confirmed by several of the titles I saw. A minor French bedroom farce, Le Paradis (M. G. Leprieur, 1914 or 1915), had a brief passage of the sort of blocking and revealing we find in many films of the period. The painter Raphael Delacroix (no kidding) is pretending to be the lover of Claire Taupin to deflect the advances of randy M. Pontbichot. But Claire is actually the mistress of M. Grésillon. . . .

First, very frontal staging strings out Pontbichot, Raphael, and Claire. The older man relents in his pursuit of her.

In the vivid depth characteristic of the tableau tradition, Pontbichot withdraws. But his position accentuates that central door, which starts to open.

Most remarkably, Pontbichot ducks almost entirely behind the couple, giving pride of place to M. Grésillon’s arrival in the center of the shot.

Pontbichot slides out in time to register Grésillon’s outraged reaction to finding his mistress in another man’s arms.

Grésillon rushes to the frontal plane, furious. As ever, a thrust to the foreground creates a major spatial/ dramatic event.

Although the Le Paradis passage is ABC compared to the emotionally powerful patterns of staging we find in Ingeborg Holm (1913), it illustrates how even average films could resort to the blocking/ revealing tactic within the deep-space geometry of the tableau.

More flamboyant was Il Jockey della Morte (1915), an Italian circus film made by the Dane Alfred Lind. Its bold lighting and varied angles on the Big Top recalled the Danish films of a few years before. Halfway through, Lind launches a dazzling chase that features leaps from a tall bridge and bicycling stunts on a cable stretched across a river.

Another Italian film, this time a diva vehicle, suggests that by 1917 1923 (see below) the tableau style was already giving way had given way to scenes organized around close shots. (See below.) L’Ombra (Mario Almirante) starred Italia Almirante Manzini as a lively, trusting wife who becomes paralyzed. While her husband betrays her with her younger protégée, she gradually recovers bodily movement. Yes, a paralyzed diva seems a contradiction in terms, but one small-scale scene shows a remarkable range of emotions. Berta’s hands start twitching, one lifts up, and she stares wildly, as if it were an alien being.

In an earlier scene, Berta had asked that a mirror facing her be tipped upward so that she would never see herself sitting immobile. This shot pays off now, when the hand ascends almost magically into the bit of reflection she can see.

When the hand descends, her astonishment turns into joy. She experimentally shoves the hands together, as if asserting her control.

In the end, she kisses her hands as if they were pampered children.

Manzini runs through many more micro-emotions than I’ve indicated here, but this sample is typical of the ways in which L’Ombra avoides the long-shot choreography of only a few years before and builds a performance out of face, body, and arms in a close framing. The mirror-shot motif shows that fairly careful filmic construction was emerging at this point too.

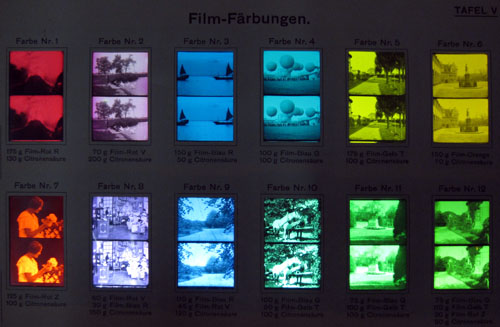

During my stay, I learned more about tinting and toning from the ever-helpful Noël Desmet. On the seldom-seen World War I drama L’Empreinte de la patrie (M. Dumeny, 1915), some images had curious oscillating patches of rusty brown. Noël explained that when Prussian Blue toning was combined with rose tinting, the chemicals eventually reacted to alter the pink cast. An example is shown at the top of this section, though the blue is more saturated in the original.

Once we get back to Madison, I’ll have to sort out all that I’ve learned from these movies. Onward and upward with the 1910s!

For more on Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern, see Scott Foundas’ interview here. The Youtube clip doesn’t do the spectacle justice. If you must know something of Jacobs’ tools, the Dailymotion video from the performance I saw offers some clues. My notions about 1910s staging are laid out in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. You can also find several discussions in earlier entries on this site. Just execute a search on tableau.

Now is a good time to thank Noël Desmet and Marianne Winderickx, both of whom are retiring from the archive in March. The research that Kristin and I have done over the years owes an enormous lot to them, and of course to the Director of the Cinematek Gabrielle Claes.

P.S. 15 November 2013: Ivo Blom has pointed out that the version of L’Ombra I saw wasn’t from 1917 but rather from 1923. Hence the corrections above. Thanks very much to Ivo! Go here for his blog and information about his newest publication on silent Italian cinema.

A tinting and toning sample card from the early 1920s. Courtesy Noël Desmet.

2-4-6-8, whose lipdub do we appreciate?

DB here:

“There is really no such thing as Art. There are only artists.” I tend to interpret the disarming opening of Ernst Gombrich’s Story of Art as a protest against the idea that art has an essence that unfolds through history. Those of us in film studies can spot the heritage of this Hegelian idea in one standard story that is told about how editing came to be a dominant technique. According to the formula, editing is “essentially cinematic,” but this essence didn’t reveal itself immediately. It emerged in phases, thanks to the insights of brilliant creators (Méliès, Porter, Griffith, the Russians). Understanding cinema’s history, according to this view, means tracking how film revealed its inherent nature.

In saying that Art doesn’t exist, Gombrich isn’t trying for an elaborate philosophical argument. He’s suggesting a way of understanding art history. His abrupt two sentences suggest that the historian shouldn’t presume that any art has an essence, a secret core that dictates how its history unfolds. He proposes seeing continuity and change in what we call the arts as springing from concrete activities of individuals and groups. Cinema’s history then becomes an account of the creative decisions of filmmakers faced with particular demands and problems. Some of those decisions can converge across the community. The results are trends, such as the increased use of editing, which have real consequences but which are aren’t the result of some secret, essential process.

Once we try to analyze art in terms of what creative communities have sought and achieved, we can ask how artists tend to behave. Across his career, Gombrich stressed that artists are sensitive to their circumstances. What tasks are assigned to the artists? What are the traditions and current fashions? What are the tastes of patrons? What constraints are put on the art-maker? How is art taught? How can the ambitious artist achieve distinction? (“What is there for me to do?”) What are the tricks of the trade at any moment? How do artists borrow from one another? And how might they compete with one another?

We often underrate competition as a stimulus to creativity. Gombrich notes that “the Dutch masters vied with each other, trying to outdo their rivals in certain accomplishments.”

Stressing the relevance of traditions not only implies an attention to the way art feeds on art; it should also make us aware of the cumulative nature of any such skill. What happens in such a hothouse atmosphere is that ambition leads to competition and frequently also to specialization, as it notoriously did in Holland.

In cinema, we might profitably consider competition as one source of the diversity within a tradition. I suspect that the great Soviet directors of the 1920s not only shared ideas but also competed by testing ever farther-out ideas about cutting. They also specialized in the manner Gombrich suggests by cultivating particular effects or genres: Pudovkin’s character-driven pathos, Eisenstein’s dynamic crowd effects, Kuleshov’s exploration of popular genres, Dovzhenko’s boldly elliptical storytelling. I’ve often thought that the Warner Bros. cartoonists probably walked out of the first screenings of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) with heavy hearts. How could they match that? They didn’t try. Instead, they cultivated something quite different: raucous, cynical, high-speed farce. And today, doesn’t it seem likely that Avatar took its final form as an effort to go beyond the CGI efforts of earlier directors—to prove that the director of Terminator II and The Abyss was still the King of the World of SPFX?

Boys and their long-take toys

One of the most visible arenas of cinematic competition is the sustained tracking shot following several characters. It requires a sort of virtuosity, or at least logistical skill, in coordinating everything—the speed and consistency of the movement, the passage of people in and out of the shot, the consistency of framing and focus, the timing of new information. Once somebody has executed such a shot, the challenge is thrown down to others. Can you make yours longer or fancier?

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I noted that Brian De Palma saw just such a challenge in Raging Bull’s famous tracking shot from the dressing room to the prizefight ring. “I thought I was pretty good at doing those kind of shots, but when I saw that I said, ‘Whoa!’ And that’s when I started using those very complicated shots with the Steadicam.” This sort of schoolyard one-upsmanship is probably what Christine Vachon had in mind when she called the single-take scene a “macho” choice.

There are some longer-term trends as well. Elaborate takes used at the start of a film can be found in the 1930s and 1940s (e.g., Ride the Pink Horse, 1947), but Welles laid down a clear marker in the opening of Touch of Evil (1957). Thereafter, starting a movie with an intricate, sustained camera movement became something of an emblem of directorial ambition.

Already, however, Dreyer, Ophuls, and Mizoguchi had used long takes, usually with camera movement, as building blocks of a film’s overall design. With Rope (1948) Hitchcock raised the possibility of making an entire film out of even fewer such shots, an initiative continued by the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó, who developed the choreography of such shots to a new level by incorporating crowds, zooms, and rack-focus passages. Béla Tarr and Gus van Sant have been modern exponents of the technique.

It was probably inevitable that somebody would try to make a feature-length film consisting of a single moving shot. Josh Becker’s Running Time (1997) renders a heist in what purports to be one take; there are cuts, but they’re pretty well disguised. Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002; above) uses video technology to create a feature out of one genuine take, “a single breath” as he called it. At the same time, Sokurov added the condition that the shot would be an exploration of a labyrinthine space, in this case the Hermitage, and a trip through different eras of Russian history.

My lipdub can lick your lipdub

Perhaps it was Russian Ark, or maybe just TV walk-and-talks, that inspired the recent cycle of single-take video lipdubs. In these the camera moves through a locale and picks up one person after another, all lip-synching the soundtrack. September’s massively popular lipdub from l’Université de Quebec à Montréal may have furnished the prototype. In the US, a pair of current examples neatly illustrates how borrowing and competition among moviemakers can yield intriguing results.

As you probably know, Shorecrest High School in Shoreline, Washington, mounted a very complicated lipdub—one take coasting through the school, picking up dozens of teens lipsynching to Outkast’s “Hey Ya!” before they all assemble in a theatre for a final shout-out. There are some somersaults too, which make any movie better. It is here.

But high school rivalries resurfaced. Shorewood High School, traditionally at odds with Shorecrest in sports and band, struck back with a lipdub of Hall and Oates’ “You Make My Dreams Come True.” The new entry raised the stakes by shooting the action backward, somersaults included. Here it is.

There’s no shortage of backwards videos, but the Shorewood clip plays in clever ways with our biases in perceiving movement. Because we’re wired to grasp motion as advancing in time, we can’t easily reconstruct the actual movement that the figures executed. After seeing the film many times, I still found it hard to visualize the actual progression of the shoot, starting from the assembled crowd and ending on the young woman running backward to the vehicle that pulls away. (A forward version is here.) Moreover, both forward and backward motion have an uncanny symmetry, so that it’s hard to detect the latter except through subtle cues like the way garments fall or a gait with a special snap. Even the moments that flaunt the reverse-motion device, such as things originally tossed down into the frame, seem instead to fly up and into the hands of bystanders.

The stakes have been raised. What will Shorecrest come up with? A radical change of angle? (An entire lipdub done from a very high or low vantage point?) Or maybe a more demanding location? (With spring coming, I’d vote for a miniature-golf course.) Anyhow, my imagination is more limited than the filmmakers’. All that matters for my purposes is that the very fact of competition gave birth to a pair of ingenious and sprightly movies.

If you’re thinking that I wrote this simply to give everyone who Googles “Gombrich lipdup” at least one result, you miss my point. Just as Gombrich was never shy about using advertising imagery and children’s drawings to illustrate some basic principles of visual psychology, so we ought to notice any examples that vividly show how artists strategize in order to create something new within a tradition. Which is to say: Yes, I consider the young filmmakers of Shorecrest and Shorewood artists. Why not?

Gombrich’s essay on Dutch painting first appeared as “Mysteries of Dutch Painting,” New York Review of Books 30, 17 (10 November 1983), 13-17. It is reprinted in his Reflections on the History of Art (London: Phaidon, 1987). Shorewood has supplied a sort of making-of bonus here, with some more challenges to Shorecrest thrown in. To see the genre coopted by politicians (who apparently can’t get all their cohorts together in the same space), go here (thanks to Camilla Lugan). Maybe US politicos could get some more support if they tried bopping like this? They could hardly look sillier than they do already.

PS 31 January: Jason Mittell of Middlebury College has alerted me to his students’ lively long-take lipdub on the virtues of recycling.

PPS 1 February: Yogesh Raut writes that another historical precedent for the dueling lipdubs would be one older than the Quebec one I cited.

In your recent entry on lipdub videos you cite a video made in 2009 by students in Quebec as “the prototype.” I think a more likely candidate is this video made by a company called Connected Ventures and first uploaded in April 2007:

While there have obviously been a ton of similar videos made since then, I think the folks at CV (who I have no connection with) probably deserve a little hat tip as innovators. Of course, it’s possible that they were copying someone else, but in general they seem to be recognized as the starters of the craze (see here, for example).

It’s good to learn this. There are probably other precedents as well. I’d just say that a prototype need not be the first work in a genre tradition; rather, it’s a fully developed, typical instance. We take Little Caesar as a prototypical gangster film, but it’s not the first. The Connected Ventures project is indeed a single take, and it follows various people lip-synching. But it doesn’t explore a building in a targeted way, making the revelation of new space add visual variety, and the walking characters seldom pass us from group to group in tight choreography (it relies more on loose pans). Like other early efforts in a genre, it seems simpler and rougher than later entries. I suppose that supports my point that competition can spur filmmakers to surpass their peers; it seems that later lipdub adepts took up the challenge to make the single take more intricate. Still, I should probably have called the Canadian video “a prototype” rather than “the prototype.” Many thanks to Yogesh for calling my attention to a particularly early work in the genre.

2 May 2010: Tonight’s Simpsons episode, “To Surveille, with Love,” opens with a single-take lipdub pastiche/ parody showing Springfield’s citizens moving to Ke$ha’s Tik Tok video. Next morning: It’s here.

French fortuities

DB here:

What is it about French doors and French books? I have no trouble opening a door in other countries, but here it’s hard to tell whether to push or pull. Yes, I know a door swings toward its hinged side, but sometimes the hinges seem hidden. Yes, there are often instructions on the door (POUSSEZ, TIREZ), but often there aren’t. And it’s not just me. French people ahead of me in a queue seem just as baffled. Yesterday, a kind lady helping me at the Bibliothèque Nationale made a mistake when opening her own office door. I also note that some doors have handwritten instructions (POUSSEZ, TIREZ) taped awkwardly to the glass. I’ve even seen one sporting a tired Post-It.

As for books, over the years I’ve fretted over a lack of coordination on two matters. First, in what direction will you print the book title on the spine? The French do it either way, top to bottom or bottom to top. Second, where does the table of contents go? Usually at the back, but not always.

Don’t get me wrong; this isn’t an anti-French diatribe. I’ve loved Paris since my first trip here in 1970. Some people come here to eat, to wander through a glorious city, to visit museums. I do some of those things too, but mostly I’ve come over the years to do research, explore bookshops, and to watch movies. It makes me boring company, I know—I don’t sit much in cafes reading newspapers and watching passersby—but it makes me happy. And Paris is about nothing if not happiness.

My first two lectures at the École Normale Supérieure seem to have gone reasonably well; I’ve got one more to give next Monday. At other times, while Kristin does Egyptological research in Berlin, I’ve done what I usually do in this city.

Landscapes and portraits

Eugene, or Eugène, Green is one of the most rigorously—some might say rigidly—formalist of contemporary filmmakers, and his moves are on display in La Réligieuse portugaise (The Portuguese Nun, 2009). It’s another movie about the making of a movie. Julie, a young Parisian with Portuguese roots, comes to Lisbon to shoot a film based on a seventeenth-century epistolary novel. Although the plot involves the passionate romance between a military officer and a nun, the project will apparently consist mostly of Julie’s voice-over and include only a couple of scenes showing her with the officer.

Green’s film exemplifies that process Dwight Macdonald described in Antonioni: the Talkies become the Walkies. Julie drifts around the city, meeting a little boy, a man contemplating suicide, and a nun. She returns at intervals to terraces that afford her a view of the gleaming city on the bay. Through a mysterious process, she comes to change her life and perhaps get a glimpse of what is holy about ordinary existence.

The first Green film I saw was Le Monde vivant (2003) and it’s still my favorite: a fable about medieval gallantry played out in a contemporary landscape, with knights and ladies and monsters wearing today’s casual clothes. I also like Le Pont des Arts (2004), though its resolute dedication to the values of High Art can put populists off.

Filming handsome women and beautiful men, Green subjects them to a regimen of geometrical framing and cutting. La Réligieuse portugaise opens with what seem to be standard establishing shots, but soon we realize that they present symmetrical pans across city views, and the shots are themselves embedded in an ABAB editing pattern. The opening not only sets up the location but announces, at one remove, the visual style.

Most noticeable is Green’s minimalist formula for a conversation. After seeing the actors in a full shot, often in profile, we get over-the-shoulder views. No surprise there, or in the tight ¾ singles that follow. But then we get straight-on facial close-ups, far more strictly patterned than comparable passages in, say, Demme’s Manchurian Candidate. Moreover, each line of dialogue is delivered whole in each shot; I didn’t detect any sound overlap at a cut. Each character is locked into his or her own image-sound module, and the scene strings these together.

The film’s trailer barely hints at the story but announces the modularity of Green dialogue. Like the opening, it introduces us to the visual scheme rather than the dramatic nexus.

Eventually you get used to these to-camera exchanges (the climactic one between Julie and the nun seems to last nearly a reel). So Green varies the format by supplying some other angles and even moments when characters turn from a scene to look enigmatically out at us—a sort of logical extension of the to-camera device. This could be a suffocating style, but I think that the prolonged landscape views give the movie a chance to breathe in a different rhythm. And Green has a certain humor about his cookie-cutter technique. He plays the director of the film, and his camera positions in that project never seem to replicate those in the movie we’re watching. Still, his crew is usually shot staring straight out at us.

The hieratic style seems to fit a movie which is, like Green’s others, about mysterious and even mystical forces inhabiting our world. Maybe the visual approach is too simple, and the plot’s quasi-resolution borders on the simplistic, but I’ve always liked films that apply strict structures to ordinary dramatic material in the hopes that something evocative will flash out. Ozu of course does this best, and in ways that Green may have picked up on; he’s usually compared to Bresson and Oliveira, but his dialogue patterns seem to owe a lot to the Japanese master. La Réligieuse portuguese is a little precious and unashamedly pretentious, but those qualities didn’t stop me from enjoying it.

Agora-phobia, apocalyptic visions, and dotty murders

I’d have welcomed a little Greenian simplicity and rigor in Agora, Alejandro Amenabar’s secular-humanist sword-and-sandal account of political and religious struggles in Alexandria in the early Christian era. It boasts the standard stuff: wailing pseudo-World-Music score, now-you-see-it-now-you-don’t cutting, glimpses of physiognomically challenged bystanders gaping at their betters, brawny heroes fighting for both Big Ideas and the love of a woman, swooping helicopterish CGI views of landscapes, handheld scenes of mass carnage, and overexplicit performances. Rachel Weisz reads her dialogue Special Delivery, often supplying two or three facial expressions per line.

She plays Hypatia, a philosopher-teacher who, in the movie’s version, anticipates the discovery of planetary orbits by a few hundred years. I’m all for a story centered on a smart scientist who happens to be a woman, and it’s a provocative dig at today’s fundamentalists to reverse costume-picture conventions and make early Christians the dogmatic oppressors. But Hypatia’s quest is literalized in a graphic motif that nobody can miss, and it’s embedded in a commonplace romantic tale of spurned lovers who don’t share her commitment to higher things, like the mathematics of conic sections. She is a political idealist surrounded by political opportunists, and the result can only be martyrdom. There are good middlebrow costume pictures, but Agora isn’t one of them.

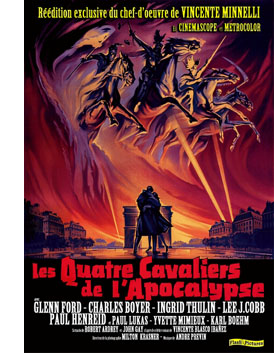

You want ersatz history done right, go to Hollywood. Minnelli’s 4 Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962) updates the old Metro property from World War I to the Big War. I saw it on 16mm long ago, before I came to appreciate Minnelli, and didn’t want to give it a go on DVD, so I was happy to see a newish copy in 35mm at the Filmothèque in the Latin Quarter. The theatre was minuscule, and the lobby was crammed with viewers anxious to escape the cold (see above). But both the Red and the Blue screening rooms were cozy, and a front-row seat afforded me a perfect view.

You want ersatz history done right, go to Hollywood. Minnelli’s 4 Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1962) updates the old Metro property from World War I to the Big War. I saw it on 16mm long ago, before I came to appreciate Minnelli, and didn’t want to give it a go on DVD, so I was happy to see a newish copy in 35mm at the Filmothèque in the Latin Quarter. The theatre was minuscule, and the lobby was crammed with viewers anxious to escape the cold (see above). But both the Red and the Blue screening rooms were cozy, and a front-row seat afforded me a perfect view.

I found the first half-hour or so of 4 Horsemen to be freighted with fairly clunky exposition laying out family relations. The high point is Lee J. Cobbs’ characteristically scenery-gobbling performance as the patriarch, culminating in his crazed vision of the night riders in the sky during a thunderstorm. Once the plot moves to Paris and Julio (Glenn Ford) falls in love with Marguerite (a weakly dubbed Ingrid Thulin), the drama gets going. Julio starts as an It’s-not-my-fight hero who, unable to flee with the married woman he loves and sickened by the depredations of the Gestapo, becomes a Resistance conspirator.

In general, I thought that the old actors—Paul Heinreid, Paul Lukas, and Charles Boyer—gave the movie most of its body and pathos. In particular, Lukas and Boyer evoke each man’s sorrow at choosing the wrong path in history, both personal and political. 4 Horsemen, made when old Hollywood was in its death throes, still had a sheen that films would lose in a few years. The scenes in the Paris Métro are shot quite close with Panavision lenses, which enables Minnelli to avoid big establishing shots and create tight, clever alignments of Julio on the platform with his woman Resistance courier. These sequences have a concise precision that American cinema would soon lose. Granted, narrative point of view skips around awkwardly, perhaps because of cutting in post-production. We probably need more of the daughter , although that would have the unfortunate consequence of giving us more of Yvette Mimieux. Nonetheless, Amenabar could study how to present motifs by noting the casual way cigarettes and lighters thread through the plot.

4 Horsemen goes rewardingly wacko at certain points, particularly in the red-soaked montages that stretch 1940s stock footage to CinemaScope proportions. (Truffaut fiddled with the same distortions, more expressively, in Jules et Jim, released at almost exactly the same time). Unhappily, these sequences are nothing like as delirious as the climactic stretch of Some Came Running. In sum, for me, mid-range Minnelli; but that’s pretty good. If Tarantino didn’t watch this in preparation for Inglourious Basterds, he should have.

Cited in that same Tarantino movie is an Occupation classic I’d never seen: Clouzot’s first feature, L’Assassin habite au 21. Of course it was playing, thanks to the attention focused on Clouzot’s unfinished L’Enfer project. L’Assassin‘s opening sequence is a flamboyant piece of work, and it includes what might be the first appearance of that strange tracking shot we start to see in 1970s horror films. You know the shot, in which the framing oscillates between objective and subjective views, now exploring, now stalking. After this flashy start, L’Assassin devolves into black comedy, putting on display a gallery of murder suspects, all eccentrics and grotesques living in the same pension. (In a metacinematic jab, it’s the “Pension des Mimosas,” citing one of the most celebrated French films of the 1930s.) Not as sour and cynical as Le Corbeau, the movie has a mordant charm, which extends to the sneakily misleading title.

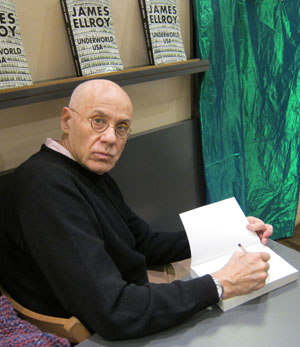

Finally, two lucky encounters. Between Four Horsemen and L’Assassin, I had a couple of hours so I slipped into a bookshop. Who should be there but James Ellroy, signing the French translation of Blood’s a Rover? Since I’m a fan, especially of the L.A. Quartet, I had to get an autographed copy. We chatted a little about his sentences, about his mother’s Wisconsin origins, and about filmmaker Ben Meade, some of whose work (Das Bus, Bazaar Bizarre) has involved Ellroy. While Ellroy signed books, he sang, “C’est si bon.”

Another encounter, this one a bit of a stretch. Tuesday I went to the Bibliothèque to reserve some scenarios of Louis Feuillade films. Wandering in the neighborhood, I came upon a tiny, appropriately named street. Not my guy, though they may have been related; this La Feuillade was a military officer of apparently mixed accomplishments. But I’ll take whatever fortuities I can get.

Paris fun, in at least three dimensions

What he saves films from: Serge Bromberg faces down the flames.

We’re ending the first week of three in Paris. At the invitation of Jean-Loup Bourget and Françoise Zamour, David is giving three weekly lectures at the École Normale Superieure. He’s introducing some ideas about the development of film style in the 1910s and early 1920s, updated with new material from his summer research in Denmark and Brussels. Jean-Loup and Françoise have proven excellent hosts, and the first lecture seemed to go well.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

We thought that Paris in January might be chilly and rainy, but we figured it had to be warmer than Madison. It turned out that Paris is experiencing unusually cold weather—about what would be normal in Wisconsin. There was light snow yesterday and last night, and the wind-chill factor was enough to turn our fingers numb if we stayed out long enough. The fountain in the center of the intersection at the northeast corner of the Jardin de Luxembourg has gradually become an iceberg.

Turns out, though, that it is still warmer than Madison, which is having highs in the single digits, as the weather forecasters say, and lows below zero. We’re better off here, though we wish we had brought our parkas.

It’s like Avatar, but much shorter

KT here:

The cold has driven us indoors, to museums and movies. As always seems to be the case, the Cinémathèque Française is hosting retrospectives of American films—in this case works by Laurel and Hardy and Gordon Douglas. There’s also a 3D series, which caught our attention right away. It’s not just your standard Kiss Me Kate and Dial M for Murder programming. In addition to such classics, there are many obscure films. We happened to arrive in time for the final two programs of the series, which ran from December 16 to January 3.

Our first full day in Paris ended with an evening of shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who in 1985 founded Lobster Films. Lobster has put out many DVDs by now, some of which we have reported on previously, here and here. In July, one of our entries on Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna mentioned that Serge presented a program of Georges Méliès films, in conjunction with the French release of Lobster’s huge DVD set of the great magician’s films.

Serge is quite a showman and obviously a popular figure, since there was a large crowd, including many families with children. On Saturday he chose and introduced a set of short 3D films in his series of programs usually titled “Retour de Flamme,” or “Saved from the Flames.” To begin the evening’s entertainment, he explained how, unlike modern celluloid 35mm film, the nitrate variety used up until the early 1950s ignites and burns easily. With the help of a rightly apprehensive volunteer holding up a film-can lid, Serge showed how modern celluloid catches fire only briefly and then dies out. The few inches of nitrate, however, flared up quickly.

Serge introduced each film thereafter, playing the piano to accompany the silents. The audience had been given both anaglyph (red-green) and polarized glasses, and Serge’s introductions to the films gave us time to switch between systems.

Many of the shorts shown on the program are available on DVD or YouTube, but the 3D effect plays best on the big screen. The evening began with an unannounced item, Three Dimensional Murder, a “Metroskopics” comedy short from 1942. A nervous detective visits a mysterious house and encounters Frankenstein, creeping hands, skeletons, and other ghouls and beasties, all of which find some occasion to throw things or hurl themselves toward the camera. The humor is, as a contemporary audience member might have said, pure corn and the 3D effects repetitive, but it was certainly a rare item.

Next came one of the Fleischer brothers’ cartoon shorts, Musical Memories. It was made with a patented system that used three-dimensional models as settings against which 2D cartoon figures drawn on cels moved about. (Such models can be seen fairly often in Popeye and other Fleischer cartoons of the 1930s.) There is some sense of depth. Still, the effect is strange, since the models have shading and the flat-looking figures do not. The cartoons are not 3D in the sense we typically think of, since there are no glasses involved.

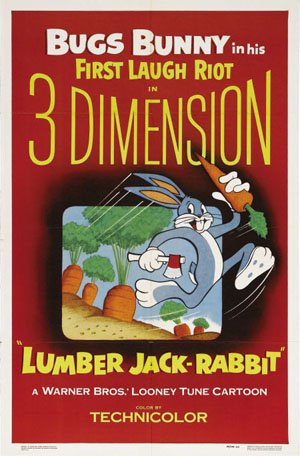

More cartoons followed, from the two main competing animation studios. Disney’s contribution was Working for Peanuts, a story set in a zoo with Chip and Dale stealing peanuts from an elephant and Donald Duck trying to foil them. Many a peanut seemed to fly out toward the spectator. Chuck Jones directed Lumber Jack-Rabbit (1954), a film that mixed size gags and spatial ones, with Bugs wandering into the domain of the gigantic Paul Bunyan. Perhaps not one of Jones’s best, but distinctly more interesting in 3D.

As Serge pointed out, most 3D technology was pioneered in the U.S. He included some exceptions, however, with a series of Soviet “Parade of Attractions” shorts shown at intervals during the evening. Experiments with underwater 3D photography and a garden of plants lacked soundtracks, but the final item, a vaudeville act with jugglers, had music and lots of bowling pins flying at the camera.

Unbelievably, there were efforts toward 3D as early as 1900. Serge showed some 3D experiments from that period by inventor Rene Bunzli. These were only about 10 seconds long and included a mildly risqué scene of a man arriving to visit his mistress and another discovering his wife in bed with her lover. The first color 3D film was shown: Motor Rhythm, made by Charley Bowers in 1940 for the Chicago Exposition and distributed by RKO. Using a combination of pixilation and 3D, the film shows a car jauntily assembling itself to a musical accompaniment, with many of the parts moving out toward the camera before attaching themselves in their proper places.

The National Film Board of Canada contributed Munro Ferguson’s Falling in Love Again, with characters wafted into the sky by road accidents and, while falling, falling in love. To watch it in high-quality 3D, go here. Pixar was represented by John Lasseter and Eben Ostby’s early digital experiment in 3D, Knick Knack, as a snowman trapped in a snow globe tries to break free to join a bathing beauty.

The evening ended with a surprise, two films that had never been meant to appear in 3D.

Méliès’s early shorts were often pirated abroad, and a lot of money was being lost in the American market in particular. After the Lubin company flooded that market with bootleg copies of a 1902 film, Méliès struck back by opening his own American distribution office. Separate negatives for the domestic and foreign markets were made by the simple expedient of placing two cameras side by side. The folks at Lobster realized that those cameras’ lenses happened to be about the same distance apart as 3D camera lenses. By taking prints from the two separate versions of a film, today’s restorers could create a simulated 3D copy!

Two 1903 titles–I think that they were The Infernal Cauldron and The Oracle of Delphi–triumphantly showed that the experiment worked. Oracle survived in both French and American copies, and the effect of 3D was delightful. For Cauldron only the second half of the American print has been preserved. Watching the film through red-and-green glasses, you initially saw nothing in your right eye, while the left one saw the image in 2D. Abruptly, though, the second print materialized, and the depth effect kicked in. The films as synchronized by Lobster looked exactly as if Méliès had designed them for 3D.

Film scholars gone wild

DB here:

William Cameron Menzies is most famous as an art director on films like The Thief of Baghdad (1924) and Gone with the Wind. He was one of the most visually daring artists to work in classic Hollywood; his eccentric framings and looming foregrounds may have influenced Orson Welles. (The Gothic distortions of Our Town and Kings Row are unlikely to be the creation of director Sam Wood.) Menzies also directed a few films, most notably the slightly nutty anti-Commie film The Whip Hand (1951).

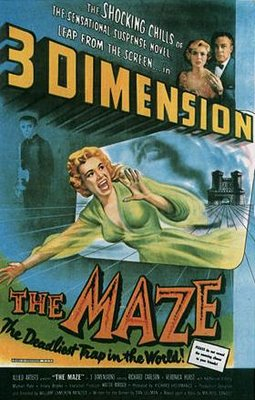

So Kristin and I had to go back to the Cinémathèque for Menzies’ rarely-seen 3D feature The Maze (1953). Alas, it was a washout. The feeble story concerns an heir returning to a castle to confront a giant frog, who may be his relative. I’d expected bravura deep-focus, with planes jutting out at me, but the film was dramatically and visually flat–no wordplay intended. The trailer, complete with fake bats on strings, is here.

We have other incidents to chronicle, but this dispatch can end with a quick list of some of the film friends we’ve encountered. We’ve already mentioned Professor Bourget, whose book on Fritz Lang came out recently (below left). We also ran into Cindi Rowell, an old friend from Pordenone and The Griffith Project, who had the excellent idea that we go to Chinatown–here hidden behind the facades of tower blocks. Cindi has vast experience in many aspects of film culture–preservation, programming, publication, web design, and the like–and is currently affiliated with the Middle East International Film Festival in Abu Dhabi.

Another old friend, Yuri Tsivian, is in Paris teaching during our visit, so we had a chance for a good dinner and lots of talk about editing in the 1910s. Below, he and Kristin pay homage to one of the shrines of Parisian cinephilia, the Studio des Ursulines movie theatre.

Left: Jean-Loup Bourget and his new book on Lang. Right: Yuri and Kristin at the Urselines.

Last night, with Kristin away in Berlin, I went to a dinner hosted by Jacques Aumont and Lyang Kim. Jacques is a major film theorist, whose many books and essays probe into the artistic qualities of cinema. His book on Eisenstein is available in English translation, as is his far-ranging study of the history and functions of images. Lyang is an outstanding photographer, whose book of haunting Christmas images Dans l’ombre de noël was just published in December. Among her pictures here are some gorgeous “fusion” images that recall our recent 3D experiences.

Then who should turn up but Marc Vernet and Rick Altman? It was an Iowa-Wisconsin reunion in the 10th. Marc is an expert on film noir, on cinematic images of absence, and on the American film company Triangle–associated with both Griffith and Ince. (Again, the 1910s.) Marc has set up a beautiful webpage full of information about early American cinema, and he blogs there frequently. Rick is known for his in-depth studies of film genre (especially the musical), film sound, and narrative theory. His most recent books, Silent Film Sound and A Theory of Narrative, are splendid contributions. Below, all four toast what turned out to be Rick’s birthday.

Today: More preparations for my lecture tomorrow, and of course at least one movie. Agora? Wiseman’s La Danse? Kinatay? The new Eugène Green, La religieuse portugaise? Or a rerelease (new print) of Minnelli’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse? Or….? The usual Parisian problem, but a good problem to have.

P. S. March 2010: After this Paris trip, I wrote an essay on William Cameron Menzies for this site.

Jacques Aumont, Lyang Kim, Rick Altman, and Marc Vernet, 9 January 2010.