Archive for the 'National cinemas: Denmark' Category

How the world ended in 1916

The End of the World (1916).

DB here:

The pull-quote might be “Gripping entertainment and a vivid introduction to storytelling strategies characteristic of Danish silent cinema!” (Too long for a poster, though.) It appears in my essay on a remarkable silent film you may not know. I bet you’d like it.

Danish cinema has gripped my interest for about fifty years. Like most cinéphiles, I started with Dreyer, moved on to Christensen, and then just tried to keep up with trends leading to Scherfig, Vinterberg, Winding Refn, Anders Thomas Jensen, and Dogme. There always seemed to be a new comedy or noir or psychological drama or just weird-ass experiment to keep my loyalty (most recently, the well-crafted Another Round).

One of our first blog entries, on 20 October 2006, was devoted to an anthology on the great film company Nordisk. Soon I was chattering about von Trier’s editing in The Boss of It All and surveying a big batch of recent releases.

Now this national cinema’s silent-era history is coming steadily online. The Danes are too modest to brag about the enormous accomplishment of making so many beautifully restored classics available for anyone to watch. But here they are, accompanied by thematic essays from critics and historians.

Like other Little Cinemas That Could (Hong Kong, Taiwan. Iran), Denmark attracts me because it has shown what can be done a lot of imagination on smallish budgets. Or sometimes, biggish budgets. That’s an impulse that emerged in the 1910s when Nordisk was struggling to keep a foothold in the international market during the Great War. One result was a pair of remarkable spectacles.

A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet, 1918) is a massive, nutty plea for peace and international—make that interplanetary—understanding. The Martians are more or less like us, except they don’t kill other creatures, which leaves them time to assemble in carefully picturesque crowds and invest in ambitious infrastructure projects.

The other big Nordisk production was The End of the World (Verdens Undergang, 1916). A comet is plunging toward earth. Can we avoid collision? Or at least survive?

All the conventions of the cosmic disaster movie (Armageddon, Independence Day, 2012) are already in place. We have the innocent family, the corrupt capitalist squeezing money out of catastrophe, the scientists trying to calm the public, and of course the separated lovers who must find one another in the midst of chaos.

The special effects range from passable to truly impressive, as in the model of the village under fiery bombardment, surmounting today’s entry. The comet’s approach is cleverly suggested as a blip in the sky, and the shots of the heroine’s drowned neighborhood are splendid.

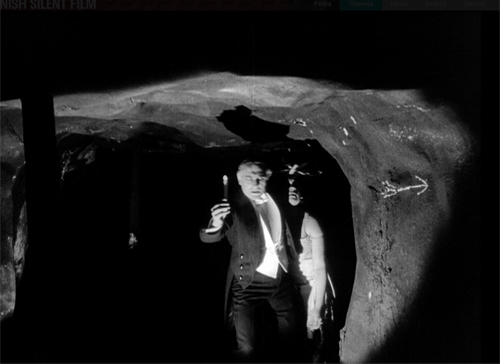

Just as remarkable are other technical achievements. The lighting in the underground passages of the capitalist’s mansion, with its Caligariesque steps, could teach the Germans a few tricks, and the miners’ fierce assault on the plutocrats is cut with rowdy, immersive vigor.

August Blom had made his reputation with Asta Nielsen dramas and another would-be blockbuster (Atlantis, 1913). He’s often considered a stolid director, but The End of the World seems to me an underrated achievement. Dismissed by many critics as over-produced, its ambitious spectacle is probably more to our current taste for overwhelming scale. For us, it seems, too much is never enough.

So I recommend to your attention this remarkable movie. As usual, I throw in a case for the 1910s as one of the great and glorious eras of film history. You can handily sample further evidence in the film links alongside the essay.

Thanks to Thomas Christensen and his colleagues at the Danish Film Archive. It was fun!

There’s always more to say about the Danes. Outside our blog entries, I’ve written about Nordisk and the “tableau aesthetic” and on early Dreyer in another essay on the Danish Film Institute site.

The End of the World (1916).

Rotterdam starts strong

Dear Comrades! (2020)

DB here:

Thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, we’re able to visit this venerable event, celebrating its fiftieth year! As with Venice and Vancouver, we’re happy to get online access to some outstanding films. We pass along the news to you here and in upcoming entries.

A dish best served cold?

Riders of Justice (2020).

Why is revenge so common as a driving force in film, fiction, and drama? Well, it sets up story action we like: search, mysteries, discovery, pursuit, confrontation. And it’s an impulse we find easy to understand. If you wrong me or mine, I’m likely to want payback.

As a high-school teacher once said to me, when I protested that the punishment wasn’t fair: “I don’t want to be fair. I want to be just.” In real life, Trump whines about unfairness, but he wouldn’t recognize justice if it met him head-on. Which it just might. Anyhow, in movies justice becomes our noblest excuse for the pleasures of vengeance.

Once our sympathy for the avenger is aroused, the storyteller has to decide how to treat the plot. Revenge shouldn’t be easy. It comes with a price. In Hong Kong films, revenge is usually the righteous settling of accounts.The price it demands is usually physical (wounds, maybe death) and social (the loss of friends cut down in the assault).

There’s another tradition of revenge drama that emphasizes the moral costs of revenge, the sense that it taints the avenger. You turn implacable, self-righteous, prone to error. Maybe the target isn’t really guilty? And can’t you forgive? And aren’t you turning obsessive? Can you sacrifice the other parts of your life to this mission? All of these questions haunt Anders Thomas Jensen’s seriocomic thriller Riders of Justice.

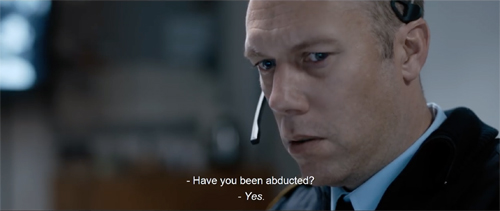

Markus, a stolid soldier, returns home when his wife is killed in a subway accident. His daughter Mathilde is traumatized. Markus’s stoic grief changes to rage when he is told by the statistician Otto, who survived the accident, that the crash was engineered by a gangster killing a rival. Markus’s icy pledge to vengeance sweeps up Otto, his two hacker friends, Mathilde, her boyfriend, and others.

In early days of this blog I wrote a lot about Danish films, which I’ve always admired. Many years ago Anders Thomas Jensen, director of Riders of Destiny, brought to our Wisconsin Film Festival The Green Butchers (2003). His scripts, for his own films and those directed by others, find a unique, tightly designed blend of drama and humor, with a penchant for showing the dumb side of male bonding (In China They Eat Dogs, 1999; Flickering Lights, 2000; Adam’s Apples, 2005)

Riders of Justice is in this vein, but it plays with larger ideas too. It starts and ends with a network-narrative premise (again, very Danish) emphasizing remote human connections. In between the characters come to grips with the role of chance in their lives. Scenes both serious and comic show them trying to reckon the reason behind their impulses. Even the numbermumbler Otto, who calculates probabilities of everything, admits to Mathilde that even the simplest event is impossible to explain through cause and effect.

You know that comfortable feeling you get at the start of a movie, when the story has hooked you, the characters command your sympathy (even when they make mistakes), and you realize that you’re in good hands for the next couple of hours? That was my response to Riders of Justice. Not least, it brings together for the umpteenth time two of the finest actors in world cinema, Mads Mikkelson (scary, in a trim Pentateuch beard) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (sensitive, blinking behind wire-rims).

Riders of Justice has been purchased by Magnolia and is planned for a spring release.

Bolshevik nostalgia in 1.33

Dear Comrades! (2020)

“Dear Comrades!” is the salutation of a letter never sent. At a meeting of officials trying to handle a sudden strike, Lyudmila Syomina voiced a need for harsh reprisals for these traitors to the Soviet state. But after being called to write a letter and read it at a forum, she flees. She is torn by fear that her daughter has been captured or killed during the very violence she advocated.

Dear Comrades!, the latest and perhaps best film from the distinguished, pleasantly erratic director Andrei Konchalovsky, is set in Novocherkassk, 1962. The strike and the massacre were revealed in 1975 by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and confirmed by an inquiry in 1992. Konchalovsky has undertaken a historical recreation, an examination of his parents’ postwar generation, and, I think, an oblique critique of authoritarianism. He seems equivocal about Putin’s “managed democracy” (though he’s not as big a booster as his brother Nikita Mikhalkov). In any case, we can’t help seeing the film as echoing the tyranny on display in Russia’s recent years, i.e., yesterday. Unlike the current demonstrators supporting Navalny, though, Konchalovsky’s characters yearn for well-run autocracy. After all, under Stalin, prices went down.

Classic Soviet fiction and film featured what’s come to be called a “conversion narrative.” In order to build any plot, you need drama. But you also have to conform to Bolshevik ideology. Some conflict can be supplied by villains (“traitors,” “wreckers”) seeking to undermine the Great Soviet Experiment. You can also create drama with characters who are ignorant of the true way, or uncertain about abandoning personal commitments and embracing the Party. So the plot can trace the gradual conversion of a character to sturdy Communist principles. This functions, in classic Socialist Realist storytelling, as psychology.

But Lyudmila is a hard-core Party loyalist. She benefits from the perks of office: a love affair with her superior in a nice apartment, the ability to jump the queue scrambling for food and matches, a paycheck that pays for a European-style coiffure. In exchange she mouths, with unblinking cobra severity, a strict adherence to policy. Yet her daughter Svetka has joined the strike and goes missing during the melée.Lyudmila’s search doesn’t easily dissolve her ideological tenacity. Like Mother Courage, Lyudmila stubbornly refuses to see what’s in front of her. She can’t believe that the KGB, not the Army, would plan a massacre that mowed down citizens.

Eventually we get glimpses of a de-conversion narrative. Lyudmila starts to sense that the current system is corrupt. “What am I supposed to believe in if not communism? Blow it all up and start again.” Yet what should replace it? The only alternative she knows. “I wish Stalin would come back.”

Konchalovsky has shot the film in lustrous, drypoint black and white, and in a silent-era ratio of 1.33:1. It’s one of the most elegantly composed and staged films I’ve seen in recent years; it could be studied just for its use of axial cuts. I’d almost call it “Straubian-Huilletian,” were it not so defiantly committed to the melodrama of a family crisis within social turmoil. But Dear Comrades! is far from your standard historical pageant. It’s at once austere and inventive.

Konchalovsky activates a great many motifs from classic Soviet film, treating them both for sly comedy and sharp drama. Satire on bureaucracy, another traditional source of plot developments, pervades the first half. Like Eisenstein in October, Konchalovsky can spare a shot mocking an empty conference table after the staff has fled.

Eisenstein is of course more grotesque: the panicked Mensheviks have leaped out of their furs, or been Raptured. The portrait of Khrushchev stands in for the Stalin picture hanging in every Socialist Realist office, parlor, bivouac, and meeting hall.

Konchalovsky stages the massacre of the strikers mostly through the heroine’s viewpoint. In place of the vast views supplied by Eisenstein in October (1928), the camera is tied down to a beauty shop.

In Soviet World War II films, the officials plan strategy in monumental headquarters (Front, 1943). The shabby offices of Konchalovsky’s provincials seem both cramped and hollow.

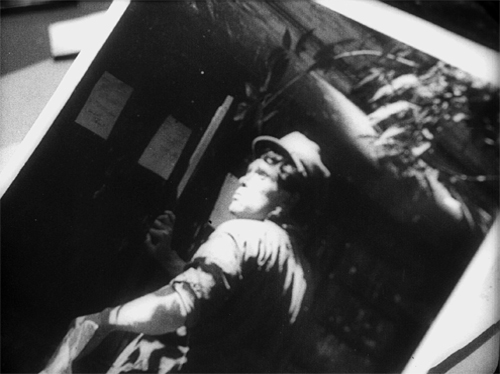

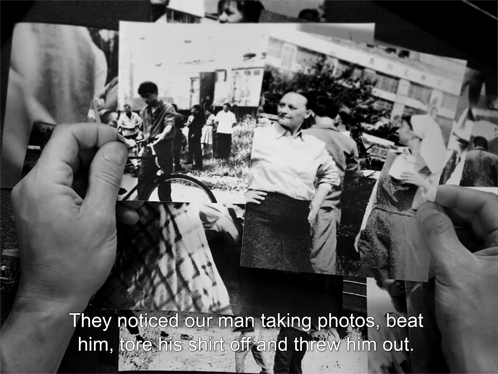

During the agitation and cleanup, Konchalovsky seems to me to rework specific images from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925). The hosing of blood from the streets seen in reflection echoes a shot of the factory in Strike. And in both, the police study the spies’ snapshots of strikers.

Dear Comrades! deserves all the attention it’s getting. Winner of this year’s Special Jury Prize at Venice, it has been picked up by Neon for US release. It’s also Russia’s submission for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award. It’s being streamed by several film festivals, notably Seattle’s, which offers it at a very reasonable price. But how I long to see it on the big screen.

I discuss some Danish network narratives in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema and other examples in some entries. Katerina Clark has an excellent discussion of the conversion narrative in The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Indiana University Press, 2000). For a discussion of Socialist Realist film style, see this entry.

P.S. 4 Feburary 2021: Anders Thomas Jensen gives a very informative interview about Riders of Justice in Variety.

Riders of Justice (2020).

Stuck inside these four walls: Chamber cinema for a plague year

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Privacy is the seat of Contemplation, though sometimes made the recluse of Tentation… Be you in your Chambers or priuate Closets; be you retired from the eyes of men; thinke how the eyes of God are on you. Doe not say, the walls encompasse mee, darknesse o’re-shadowes mee, the Curtaine of night secures me… doe nothing priuately, which you would not doe publickly. There is no retire from the eyes of God.

Richard Brathwaite, The English Gentlewoman (1631)

DB here:

We’re in the midst of a wondrous national experiment: What will Americans do without sports? Movies come to fill the void, and websites teem with recommendations for lockdown viewing. Among them are movies about pandemics, about personal relationships, and of course about all those vistas, urban or rural, that we can no longer visit in person. (“Craving Wide Open Spaces? Watch a Western.”)

Cinema loves to span spaces. Filmmakers have long celebrated the medium’s power to take us anywhere. So it’s natural, in a time of enforced hermitage, for people to long for Westerns, sword and sandal epics, and other genres that evoke grandeur.

But we’re now forced to pay more attention to more scaled-down surroundings. We’re scrutinizing our rooms and corridors and closets. We’re scrubbing the surfaces we bustle past every day. This new alertness to our immediate surroundings may sensitize us to a kind of cinema turned resolutely inward.

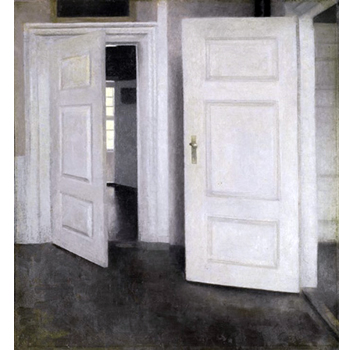

Long ago, when I was writing a book on Carl Dreyer, I was struck by a cross-media tradition that explored what you could express through purified interiors. I called it “chamber art.” In Western painting you can trace it back to Dutch genre works (supremely, Vermeer). It persisted through centuries, notably in Dreyer’s countryman Vilhelm Hammershøi (below).

Plays were often set in single rooms, of course, but the confinement was made especially salient by Strindberg, who even designed an intimate auditorium. For cinema, the major development was the Kammerspielfilm, as exemplified in Hintertreppe (1921), Scherben (1921), Sylvester (1924), and other silent German classics. Kristin and I talk about this trend here and here.

In the book I argued that Dreyer developed a “chamber cinema,” in piecemeal form, in his first features before eventually committing to it in Mikael (1924) and The Master of the House (1925). Two People (1945) is the purest case in the Dreyer oeuvre: A couple faces a crisis in their marriage over the course of a few hours in their apartment. (Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem available with English subtitles.) But you can see, thanks to Criterion, how spatial dynamics formed a powerful premise of his later masterpieces Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964).

Dreyer wasn’t alone. Ozu tried out the format in That Night’s Wife (1930), swaddling a husband, wife, child, and detective in a clutter of dripping laundry and American movie posters.

Bergman exploited the premise too, in films like Brink of Life (1958), Waiting Women (1952), his 1961-1963 trilogy, and Persona (1966). (All can be streamed on Criterion.)

Chamber cinema became an important, if rare expressive option for many filmmaking traditions. Writers and directors set themselves a crisp problem–how to tell a story under such constraints?

The challenge is finding “infinite riches in a little room.” How? Well, you can exploit the spatial restrictiveness by confining us to what the inhabitants of the space know. Limiting story information can build curiosity, suspense, and surprise. You can also create a kind of mundane superrealism that charges everyday objects with new force.

On the other hand, you need to maintain variety by strategies of drama and stylistic handling. Chamber cinema–wherever it turns up–offers some unique filmic effects, and maybe sheltering in place is a good time to sample it.

Herewith a by no means comprehensive list of some interesting cinematic chamber pieces. For each title, I link to streaming services supplying it.

Bottles of different sizes

From David Koepp I learned that screenwriters call confined-space movies “bottle” plots. There’s a tacit rule: The audience understands that by and large the action won’t stray from a single defined interior. In a commentary track for the “Blowback” episode of the (excellent) TV show Justified, Graham Yost and Ben Cavell discuss how TV series plan an occasional bottle episode, and not just because it affords dramatic concentration. It can save time and money in production.

Usually the bottle consists of more than a single room. The classic Kammerspielfilms roam a bit within a household and sometimes stray outdoors. But their manner of shooting provides a variety of angles that suggest continuing confinement. Dreyer went further in The Master of the House. He built a more or less functioning apartment as the set, then installed wild walls that let him flank the action from any side. Then editing could provide a sense of wraparound space.

The variations in camera setups throughout the film are extraordinary. Dreyer would create more radically fragmentary chamber spaces in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), while his later films would use solemn, arcing camera movements to achieve a smoother immersive effect. (For more on Dreyer’s unique spatial experimentation, here’s a link to my Criterion contribution on Master of the House. I talk about the tricks Dreyer plays with chamber space in Vampyr in an “Observations” supplement on the Criterion Channel.)

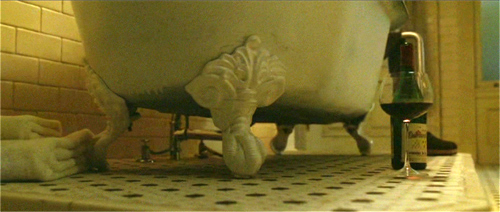

Likewise, Koepp’s screenplay for Panic Room allows David Fincher to move 360 degrees through several areas of a Manhattan brownstone. The film also offers a fine example of how our awareness of domestic details gets sharpened by a creeping camera.

Trust Fincher to find sinister possibilities in a dripping bathtub leg and a kitchen island.

Confined to quarters

Detective Story (1951).

Many chamber movies are based on plays, as you’d expect. Unlike most adaptations, though, they don’t try to “ventilate” the play by expanding the field of action. Or rather, as André Bazin pointed out, the expansion is itself fairly rigorous. They don’t go as far afield as they might.

Bazin praised Cocteau’s 1948 version of his play Les parents terribles (aka “The Storm Within”) for opening up the stage version only a little, expanding beyond a single room to encompass other areas of the apartment. This retained the claustrophobia, and the sense of theatrical artifice, but it spread action out in a way that suited cinema’s urge to push beyond the frame. The freedom of staging and camera placement is thoroughly “cinematic” within the “theatrical” premise.

Depending on how you count, Hitchcock expanded things a bit in his adaptation of Dial M for Murder. Apart from cutting away to Tony at his club, Hitchcock moved beyond the parlor to the adjacent bedroom, the building’s entryway, and the terrace.

An earlier entry on this site talks about how 3D let Sir Alfred give an ominous accent to props: a particularly large pair of scissors, and a more minor item like the bedside clock.

Hitchcock gave us a parlor and a hallway in Rope (1948), but when Brandon flourishes the murder weapon, the framing audaciously reminds us that we aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen.

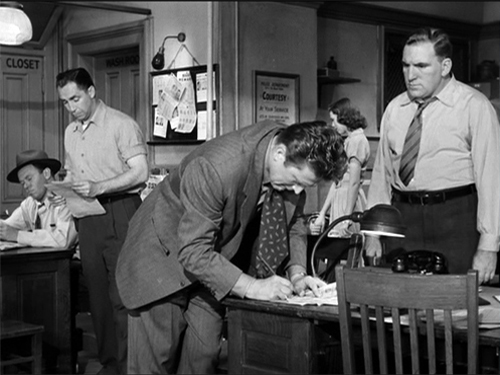

Bazin did not wholly admire William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951), despite its skill in editing and performances; he found it too obedient to a mediocre play. True, the film doesn’t creatively transform its source to the degree that Wyler’s earlier adaptation of The Little Foxes (1941) did; Bazin wrote a penetrating analysis of that film’s remarkable turning point. Detective Story is more obedient to the classic unities, confining nearly all of the action to the precinct station. Although I don’t think Wyler ever shows the missing fourth wall, he creates a dazzling array of spatial variants by layering and spreading out zones of the room. In his prime, the man could stage anything fluently.

As Bazin puts it: “One has to admire the unequaled mastery of the mise-en-scène, the extraordinary exactness of its details, the dexterity with which Wyler interweaves the secondary story lines into the main action, sustaining and stressing each without ever losing the thread.”

Some films are even more constrained. 12 Angry Men (1957), adapted from a teleplay, is a famous example. Once the jury leaves the courtroom, the bulk of the film drills down on their deliberation. Again, the director wrings stylistic variations out of the situation; Lumet claims he systematically ran across a spectrum of lens lengths as the drama developed.

But you don’t need a theatrical alibi to draw tight boundaries around the action. Rear Window (1954), adapted from a fairly daring Cornell Woolrich short story, is as rigorous an instance of chamber cinema as Rope. Here Hitchcock firmly anchors us in an apartment, but he uses optical POV to “open out” the private space.

With all its apertures the courtyard view becomes a sinister/comic/melancholy Advent calendar.

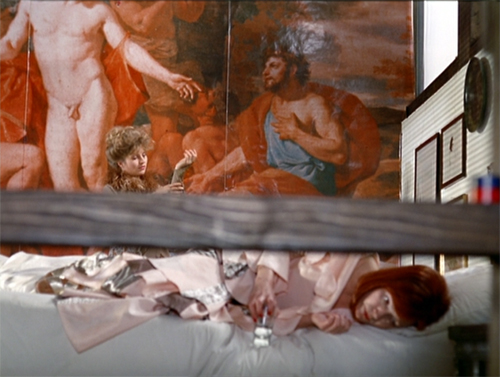

Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) denies us this wide vantage point on the outside world. This space seems almost completely enclosed. But Fassbinder finds a remarkable number of ways to vary the set, the camera angles, and the costumes. We’re immersed in the flamboyant flotsam of several women’s lives. The result is a cascade of goofily decadent pictorial splendors.

It’s virtually a convention of these films to include a few shots not tied to the interiors. At the end, we often get a sense of release when finally the characters move outside. That happens in 12 Angry Men, in Panic Room, in Polanski’s Carnage (2011) , and many of my other examples. Without offering too many spoilers, let’s say Room (2015) makes architectural use of this option.

On the road and on the line

Filmmakers have willingly extended the bottle concept to cars. The most famous example is probably Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), which secures each scene in a vehicle and mixes and matches the passengers across episodes. The strictness of Kiarostami’s camera setups exploit the square video frame and always yield angular shot/reverse shots. They reveal how crisp depth relations can be activated through the passing landscape or in story elements that show up in through the window.

Perhaps Kiarstami’s example inspired Danish-Swedish filmmaker Simon Staho. His Day and Night (2004) traces a man visiting key people on the last day of his life, and we are stuck obstinately in the car throughout. This provides some nifty restriction, most radically when we have to peer at action taking place outside.

Staho’s Bang Bang Orangutang (2005), a portrait of a seething racist, takes up the same premise but isn’t quite so rigorous. We do get out a bit, but the camera stays pretty close to the car. I discuss Staho’s films a little in a very old entry.

Like autos, telephones provide a nice motivation for the bottle, as Lucille Fletcher discovered when she wrote the perennial radio hit, “Sorry, Wrong Number.” The plot consists of a series of calls placed by the bedridden woman, who overhears a murder plot. The film wasn’t quite so stringently limited, but the effect is of the protagonist at the center of several crisscrossed intrigues.

A purer case is the Rossellini film Una voce umana (1948), in which a desperate woman frantically talks with her lover. It relies on intense close-ups of its one player, Anna Magnani.

It’s an adaptation of a Cocteau play, which Poulenc turned into a one-act opera. In all, the duration of the story action is the same as the running time.

I wish Larry Cohen’s Phone Booth displayed a similarly obsessive concentration, but we do have the Danish thriller The Guilty, where a police dispatcher gets involved in more than one ongoing crime. We enjoyed seeing it at the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival.

And of course car and phone can be combined, as they are in Locke (2013)–another play adaptation. Tom Hardy plays a spookily calm businessman driving to a deal while taking calls from his family and his distraught mistress. Those characters remain voices on the line while he tries to contend with the pressures of his mistakes.

House arrest, arresting houses

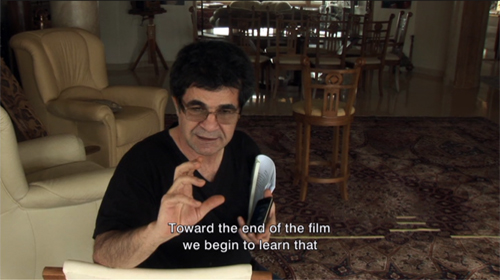

Sometimes you must embrace the chamber aesthetic. In 2010 the fine Iranian director Jafar Panahi was forbidden to make films and subjected to house arrest. Yet he continued to produce–well, what? This Is Not a Film (2012) was shot partially on a cellphone within (mostly) his apartment.

Wittily, he tapes out a chamber space within his apartment. Then he reads a script to indicate how absent actors could play it and how an imaginary camera could shoot it.

But his imaginary film still isn’t an actual film, so he hasn’t violated the ban. So perhaps what we have is rather a memoir, or a diary, or a home video? Panahi’s virtual film (that isn’t a film) exists within another film that isn’t a film. Yet it played festivals and circulates on disc and streaming. The absurdity, at once touching and pointed, suggests that through playful imagination, the artist can challenge censorship.

Panahi slyly pushed against the boundaries again with Closed Curtain (2013, above). Shot in his beach house, it strays occasionally outside. Next came Taxi (2015), in which Panahi took up the auto-enclosed chamber movie, with largely comic results.

More recently, he has somehow managed to make a more orthodox film, 3 Faces (2018), which considers the situation of people in a remote village.

The chamber-based premise needn’t furnish a whole movie. As in Room, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) is tightly concentrated in its first half. We are in two enclosures, a house and a train. The film then bursts out into a rushed, wide-ranging investigation. Large-scale or less, the chamber strategy remains a potent cinematic force.

They say that the last creatures to discover water will be fish. We move through our world taking our niche for granted. Cinema, like the other arts, can refocus our attention on weight and pattern, texture and stubborn objecthood. We can find rich rewards in glimpses, partial views, and little details. Chamber art has an intimacy that’s at once cozy and discomfiting. Seeing familiar things in intensely circumscribed ways can lift up our senses.

So take a break from the crisis and enjoy some art. But return to the world knowing that for Americans this catastrophe is the result of forty years of monstrous, gleeful Republican dismantling of our civil society. Rebuilding such a society will require the elimination of that party, and the career criminal at its head, as a political force. This pandemic must not become our Reichstag fire.

Yeah, I went there.

Thanks to the John Bennett, Pauline Lampert, Lei Lin, Thomas McPherson, Dillon Mitchell, Erica Moulton, Nathan Mulder, Kat Pan, Will Quade, Lance St. Laurent, Anthony Twaurog, David Vanden Bossche, and Zach Zahos. They’re students in my seminar, and they suggested many titles for this blog entry.

Bazin’s comments on Detective Story come in his 1952 Cannes reportage, published as items 1031-1033, and as a review (item 1180), in Écrits complets vol. I, ed. Hervé Joubert-Laurencin (Paris: Macula, 2018), pp. 918-922, 1059. My quotation comes come from the review, where he does grant that Wyler is the Hollywood filmmaker “who knows his craft best. . . . the master of the psychological film.”

The tableau style of the 1910s probably helped shift Dreyer toward the chamber model, which he learned to modify through editing. I discuss Dreyer’s relation to that style in “The Dreyer Generation” on the Danish Film Institute website. Also related is the web essay, “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic.”

Some other examples could be mentioned, but I didn’t find them on streaming services in the US. It would be nifty if you could see the tricks with chamber space in Dangerous Corner (1934); fortunately it plays fairly often on TCM. There’s also Duvivier’s Marie-Octobre (1959), a tense drama about the reunion of old partisans.

I especially like the 1983 Iranian film, The Key, directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and scripted by Kiarostami. It’s a charming, nearly wordless story of how a little boy tries to manage household crises when Mother is away. It has the gripping suspense that is characteristic of much Iranian cinema, and the boy emerges as resourceful and heroic (though kind of messy). Kids would like it, I think.

Also, I’ve neglected Asian instances. Maybe I’ll revisit this topic after a while.

P.S. 1 April 2020: Thanks to Casper Tybjerg, outstanding Dreyer scholar, for corrections about the nationality of The Guilty and the Staho films.

Gertrud (1964).

Vancouver 2019: Some final observations

It Must Be Heaven (2019).

We wrap up our coverage of this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival with a joint entry on movies from around the world.

Kristin here:

Out of Tune (2019)

Danish director Frederikke Aspöck has created a prison film with a seamless combination of humor, social commentary, and a subtly disturbing undertone.

Markus Føns arrives in jail, awaiting trial for corporate fraud. As a result of his popular financial advice books, he is notorious for having caused many to face financial ruin. He runs into the thuggish brother of a man who has lost a huge amount through Markus’ advice. The brother insists that Markus is owes the brother the full amount he lost. He dismisses Markus’ point that all investments are a gamble and, along with his gang, beat Markus up.

Terrified of further violence, Markus voluntarily transfers to the solitary-confinement wing, joining rapists, child molesters, and others who fear being attacked by other inmates. The prisoners in this wing are not really isolated, however. They’re let out to do chores, to sing in a choir, and to earn a bit of money by making pom-poms for local schools and celebrations.

The choir members (above), led by Niels, prove an engaging bunch, and much humor is generated by their disagreements about which songs from a collection of Danish classics they should sing. Markus initially sticks to his cell but finally joins the group. In one of the film’s funniest scenes, Niels insists that Markus is not a tenor but a bass, forcing him to sing in a range that clearly is not natural to him.

One of the rules of solitary is that the prisoners are not allowed to reveal or discuss their crimes–though Markus is famous enough that all the others know what he did. Simon, a genial young black man, admires Markus and increasingly becomes his ally against the dictatorial Niels.

Gradually the tone darkens, however, as it is revealed that two of the main characters, including Niels, are pedophiles. Markus declares that his white-collar crimes are less heinous than child molestation. The others, however, including Simon, declare Markus’ crimes worse. At that point he decides to take his revenge on the group and especially Niels, by seizing the leadership of the choir.

This balancing act between humor and drama works well, with Aspöck managing to make the pedophiles somewhat sympathetic and amusing characters without excusing their crimes. The satire on how upper-class celebrity criminals like Markus manage to become objects of fascination is effective without becoming heavy-handed.

It Must Be Heaven (2019)

I am a fan of the Palestinian director Elia Suleiman, who manages to make autobiographical feature films at wide intervals. I am particularly fond of Divine Intervention (2002) and I also like The Time That Remains: Chronicle of a Present Absentee, which we saw in Vancouver in 2009.

It Must Be Heaven does not quite achieve the excellence of those earlier two films, being a bit uneven. Still, it contains many excellent scenes and gags, and it was among the best films I saw at this year’s festival.

The earlier portion sets up Suleiman’s sense of unease about the events that surround him in his native Nazareth. A running motif has him peeping timidly over his back wall as his neighbor’s son without permission picks lemons from his trees. Gradually the man takes over the care of the whole orchard.

Eventually Suleiman goes abroad, and we soon learn that he is seeking funding for his next film, presumably the film we are now watching.

Two of the funniest scenes take place in the offices of the producers Suleiman visits in Paris and New York. Both end in failure, but the huge number of international companies and funding agencies listed in the credits suggests that the director’s efforts must have been complex, lengthy, and, in some cases successful. The scene in New York involves a cameo by Gael García Bernal, who has an offer on a Mexican project of his own, but he obviously has little control of that project, let alone the ability to aid his friend Suleilman. The one in Paris has Vincent Maraval, of Wild Bunch (one backer of the film) playing a producer who rejects the project as not Palestinian enough.

Other than visiting producers, Suleiman wanders the streets of Paris and New York, observing incongruous events around him. Some of these are very amusing, others simply odd.

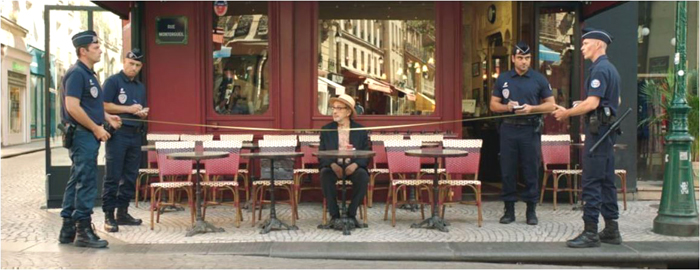

Comparing It Must Be Heaven to Suleiman’s earlier “autobiographical” films, the basic problem here becomes apparent. While Suleiman (or an actor playing him as a child) wove in and out of the action, participating in it, here many scenes involve him as a largely passive observer of events that have little or nothing to do with him. In one such scene, he sits at a cafe table, watching as four police officers carefully measure the spaces of the outdoor tables before pronouncing them compliant with regulations (see top). In Palestine he walks in the country and observes a Bedouin woman with a novel way of transporting two large vats of liquid. In Paris he observes police on Segways performing a search in the street below in perfectly choreographed loops. At times he is more affected by the action, as when a tattooed muscle-man stares at him threateningly in an otherwise empty Métro car.

Suleiman is an engaging performer, but watching him stare in bemusement at the odd behavior that he encounters in each place he visits grows a bit old. Nevertheless, there are many funny or just bizarre scenes in the film, including a lengthy tussle between Suleiman and an invading sparrow determined to perch on his keyboard. The visit to Paris, in which Suleiman somehow got the streets emptied so that he wanders completely alone through them is both impressive and somewhat disconcerting (above).

Suleiman is routinely compared to Tati and Keaton, but his work is similar to that of Roy Andersson too, is equally apt, although Andersson does not assign a single character to be an observer. Here to a considerable extent Suleiman keeps to the long-shot framings that are familiar from his other films, but there are also more close-ups, in particular of his face as his reacts to what he sees.

It Must Be Heaven suggests that wherever Suleiman goes once he leaves his Palestinian home, he sees the same sorts of odd behavior, especially the violence that has become endemic everywhere. (A particularly hilarious episode shows Suleiman shopping in New York and noticing that everyone around him, including babies, is carrying some sort of weapon, from pistol to bazooka.) I suspect, however, that most viewers would fail to catch the political points Suleiman claims in interviews to be making.

DB here:

Oh Mercy (Roubaix, une lumière)(2019)

Arnaud Desplechin regards his previous films (Esther Kahn, Kings and Queen, A Christmas Tale) as “a fireworks of fiction,” as he explained in a Q & A session. His latest, Oh Mercy, is based on fact. The screenplay dramatizes criminal cases that took place in Roubaix, the impoverished town Desplechin grew up in. The result is an unusual policier, which twists some crime-movie conventions in intriguing ways.

As we expect, the cops form a team. The emphasis is divided between the young and eager Louis Coterelle and the experienced chief Daoud. But Coterelle is an ascetic young man, reminiscent of Bresson’s country priest. Daoud, rather than being the tough boss who has to make his staff shape up, is an eerily quiet and sympathetic professional. Cast out by his family, he devotes his life to his work (and the occasional horse race). These characters keep surprising us. It’s the pious Coterelle who, pushing to make his mark, bullies suspects, while Daoud’s gentle ways eventually tease the truth out of them.

The police procedural typically shows several cases worked at once, with some minor ones and others explored in more detail. Desplechin’s film does the same, as an automobile fire and a petty robbery introduce us to the main cops. To help a friend, Daoud must also investigate a runaway teenager. Soon there’s a building fire, and then a murder on the same block. Gradually it becomes clear that these two crimes are connected–another convention of the genre.

It’s the nature of the connection, though, that reveals Desplechin’s originality. About halfway through the film the police commit their energies to questioning two women, Claude and Marie, who share an apartment. In a string of riveting interrogations, the film shows Coterelle and Daoud, each in their own way, peeling back layers of the women’s relationship. It’s a tour de force relying on the Prisoner’s Dilemma, and it reveals as much about the cops as it does about the sad, confused lovers. Even the reenactment of the crime, another staple of the genre, avoids sensationalism and achieves a mournful gravity.

Most cop movies make justice a matter of vengeance (“This time it’s personal”), so it’s rare to find one about pity. The lies and mistaken memories that prolong the investigation are accepted by Daoud with quiet compassion. A gradual-revelation film like this, impeccably plotted and directed though it is, depends crucially on performances, and the principals (Roschdy Zem as the patient Daoud, Léa Seydoux as Claude, Antoine Reinartz as Coterelle) are extraordinary. Above all I will remember Sara Forestier as the skittish Marie, perpetually corrugating her forehead, always a beat behind in appraising how much the woman she loves loves her.

Once more we thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies. In addition, we appreciate the generosity of Arnaud Desplechin in answering questions about his film.

Oh Mercy (2019).