Archive for the 'Directors: Demy' Category

Capellani ritrovato

Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse.

Kristin here–

[Note, July 11, 2011. The release of a considerable number of Capellani films on DVD since the 2010 festival has allowed me to add some frames to my examples below. The frames from L’Arlésienne, L’Épouvante, and Pauvre mère are new, and the one from Cendrillon has been replaced by a better copy. For more on the DVD, see the entry on the second half of the retrospective.]

Back in the 1980s and early 1990s, researchers into silent cinema became used to the discovery of little-known auteurs. The 1910s proved an exceptionally rich source of directors beyond the familiar names of Griffith, Ince, Chaplin, Feuillade, Lubitsch, Stiller, and Sjöström.

In 1986 Le Giornate del Cinema Muto’s epic retrospective of pre-1919 Scandinavian cinema revealed the Swedish master Georg af Klercker. In 1989, a similarly ambitious presentation of pre-Revolutionary Russian films brought the work of Evgeni Bauer to light. In 1990, the “Before Caligari” year added Franz Hofer to the list of obscure directors at last receiving their due. After that quick series of revelations, there has been a dearth of such significant revelations until, some would argue, now.

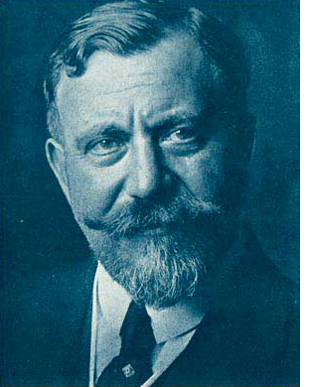

This year Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato presented 24 films directed by Albert Capellani (1874-1931), previously known mainly to specialists for two films, his magisterial adaptations of Hugo in the four-part serial Les Misérables (1912) and of Zola in Germinal (1913). The retrospective has been  arranged by Mariann Lewinsky, who, as in previous years, has also been responsible for this year’s “Cento anni fa” program, covering the output of 1910. (The “Cento anni fa” series began in 2003, with Tom Gunning as programmer, and Mariann took over that duty in 2004.)

arranged by Mariann Lewinsky, who, as in previous years, has also been responsible for this year’s “Cento anni fa” program, covering the output of 1910. (The “Cento anni fa” series began in 2003, with Tom Gunning as programmer, and Mariann took over that duty in 2004.)

A gradual rediscovery

When Georges Sadoul wrote his multi-volume Histoire général du cinéma, the second part (1948) mentioned Capellani a few times. With the lack of available prints of the films, however, he was limited to treating the director primarily as the head of S.C.A.G.L., the prestige production unit launched by Pathé in 1908. Richard Abel’s The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema 1896-1914 (1994) devotes considerably more space to Capellani. Dick was able to view and analyze seven of the shorts and four features but was hampered by the incompleteness of some of these and the lack of such key films as L’Arlésienne (1908). As Mariann points out in her program notes, Capellani’s significance has been commented on by several scholars, including our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. (Ben’s detailed analysis of the acting in Germinal is here, including a citation to a 1993 article on the film by Michel Marie).

Mariann, however, has recently been instrumental in bringing Capellani’s films to broader attention. The decision to mount retrospectives of his work has spurred archives to restore several which had been unavailable or lost, and more prints will presumably be ready for next year.

Capellani has actually been creeping up on us in Bologna for some time now. In 2006, Mariann’s programs from 100 years ago had reached 1906–the year when Capellani’s career really got started, though at least one of his films appeared in 1905. We saw only one from 1906, La Fille du sonneur. I can’t say that I remember anything about it. In the 1907 program, Les Deux soeurs, Le Pied de mouton, and Amour d’esclave. Again, I probably would have to say that I don’t recall these films, except that I vaguely recognized Le Pied de mouton, a fairy tale about a young man who receives a magic object in the form of a large sheep’s foot, when it was shown again this year.

By 2008, however, a pattern had started to emerge, and Mariann showed seven Capellani films, with six of them forming one program devoted solely to the director’s work, “Albert Capellani and the Politics of Quality”: La Vestale, Mortelle idylle, Corso tragique, Samson, L’Homme aux gants blancs, and Marie Stuart. The seventh, Don Juan, appeared in the “Men of 1908” program.In visiting archives and choosing films Mariann often saw prints without credits and from unknown directors, so the pattern only gradually became clear. In the 2008 catalogue she reflected on her realization that Capellani was showing up regularly in her choices for the annual centennial celebrations: “When organising the 1907 programme, however, in the light of Amour d’esclave, a gorgeous mise-en-scène of classical antiquity, I asked myself for the first time, ‘Who made this sophisticated film?'”

She speculated that the relative neglect of Capellani perhaps came from the Surrealists’ campaign against highbrow filmmaking during the 1910s and 1920s:

From his very first film on–the memorable Le chemineau of 1905, based on an episode from Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables–Albert Capellani transports the contents and qualities of bourgeois culture to the cinema. He films Zola, Hugo and Daudet–his Arlésienne of 1908 has unfortunately been lost. His many fairy tale films (scène des contes), biblical and historical scenes reveal him as a great art director, who also adopted the latest developments in modern dance and worked with its stars Stacia Napierkowska and Mistinguiette. Highly versatile, he had an unerring sense of the best approach to a given genre.

Fortunately, L’Arlésienne has subsequently been discovered by Lobster Films, just in time to be presented this year.

The 2009 program contained only two Capellani films, but one was the extraordinary Zola adaptation L’Assommoir. This had been known only from fragments until a complete copy was found in Belgium. It displays an unusual degree of realism that fits the naturalist subject matter and also contains complex and deft staging that moves numerous characters around a scene in a way that shifts the spectator’s attention among them exactly as the flow of the narrative requires. The other, La Mort du Duc d’Enghien, was shown again this year. It’s a rare case of an historical drama of the period that manages to arouse a genuine sympathy for its main character, a young nobleman unjustly arrested and executed upon Napoleon Bonaparte’s orders. More on it later. The 2009 catalogue announced that in the following year, Capellani would graduate from the annual “Cento anni fa” programs to his own retrospective.

This year’s films

This first full-fledged Capellani retrospective gave a generous though not complete overview of his surviving films from early 1906 to 1914—a few bearing 2010 restoration dates. Capellani also worked in the United States from 1915 to 1922, and the program included The Red Lantern, a 1919 feature starring Nazimova. This, Mariann’s notes assure us, is “a taster for next year’s festival,” which will include further restorations from the French period, as well as more features from his American career. (It would be good to see the other Capellani films shown in previous years repeated, now that we have a sense of his work more generally.)

Ideally our examples here should include frames from the films shown at this year’s festival, but none of them is out on DVD. The Brewster article linked above has a generous selection of well-reproduced frames from a 35mm print of Germinal. As far as I know, the only Capellani film available on DVD is Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse, on the third volume of Kino International’s “The Movies Begin” set. I’m sure it was included there not because it was a Capellani but because it survives in beautiful condition and is an epic with elaborate hand-coloring. I’ve included frames at the top and bottom of this entry, despite the fact that it has not been shown at Bologna. The smaller frames illustrating a few of films shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato come from the Gaumont Pathé Archives website (registration required). This site is the best online source of information on the director’s films, including complete video versions in a few cases. These are, however, quite small screens, and they display the double branding of a prominent timer and a bug of a Pathé rooster superimposed over much of the frame.

Capellani had worked in the theater as a director and actor until Pathé recruited him in 1905. In a sense, he became a specialist in literary adaptations, especially after his appointment in 1908 as artistic director of S.C.A.G.L. Yet the films being shown this year include pure melodrama (such as Pauvre mère, “Poor mother,” 1906), crime-suspense films (L’Épouvante, “The Terror,” 1911), classic fairy-tales (Cendrillon, 1907), and historical/biblical costume pictures (Samson, 1908).

With his theatrical background, it is not surprising that Capellani was able to cast many old colleagues in his films, notably Henry Krauss, who played Quasimodo in Notre-Dame de Paris (1911) and Jean Valjean in Les Misérables (1912). Wherever his actors came from, however, Capellani was a master at directing performances. In many cases the acting makes characters who would seem completely conventional figures in most films of the day into people with whom the audience can empathize.

The staging in Capellani’s shots is inevitably impeccable. The progression of the story is clear even in shots with numerous characters on camera. More of his stage experience coming out, one might say, but he also adapts his technique to the visual pyramid of space tapering toward the camera’s lens.

L’Évadé des Tuileries (1910), for example, deals with the Count du Champcenetz, the governor of the Tuileries during the French Revolution, who initially tries to alert the royal family to their impending arrest and subsequently flees for his life from the revolutionary forces that invade the palace. In the most spectacular shot, he rushes in, exhausted and wounded, to speak to the king as the members of the royal family gradually enter and guards surround them. Champcenetz collapses and slides partway under a chair at the foreground right as the revolutionaries burst into the room. The business of the ensuing struggle, the departure of the combatants with the royals under arrest, and a short burst of looting leaves a still scene with the dead and wounded on the floor. Suddenly an arm moves at the far lower right corner of the frame, and we become aware that Champcenetz has survived.

David has praised the sustained tableau staging in depth of the 1910s, in the films of Feuillade, Sjöström, Hofer, and others, but here is Capellani doing it all in 1910—and this is not the first of his films to display such control of the complex arrangement of actors in space.

None of this is to suggest that Capellani’s films are “stagey.” He is quite capable of a cinematic flourish for purposes of dramatic effectiveness. L’Arlésienne, shot largely on location in the old town of Arles, includes a shot of the young couple atop a tower that looks over the cityscape. The camera begins on the spire, panning right until the couple appear in medium shot, with the town beyond them and the parapet. They wander out right, and the camera pans around the parapet, only catching up with the couple when they are roughly 180 degrees opposite to where the camera started:

It is hard to believe that in London L’Arlésienne played on the same program as L’assassinat du Duc de Guise, which, sophisticated as it is in some ways, seems seems downright old-fashioned when contrasted with Capellani’s film.

Even flashier is L’Épouvante, which seems at first a simple story of a young woman in danger as she retires for the night, unaware that a burglar had stolen her jewelry just before she came in and is now hiding under the bed. She lights a cigarette and carelessly tosses the match on the floor. The camera tracks slowly back from the bed to bring the burglar into view; he registers fear that the match is still alight and might set the rug on fire. He reaches to snuff it out, and a sudden cut places us at a high angle above the heroine as she looks down and sees the hand appearing from beneath her bed. A return to the long shot displays her reaction:

Up to this point our sympathy has been entirely with the heroine. But once she escapes the room and locks the burglar in, his struggle to escape before the police find him takes up much of the remaining action and gradually gains him our sympathy as well. Trapped multiple stories up, he climbs to the roof, only to have to retreat as the pursuers rush up and search there. Moving downward, the burglar ends up hanging by an ominously bending gutter.

Only the heroine is left in her flat to discover his plight, and she lowers some drapes for him to climb up. In a touchingly awkward scene, the man is relieved but unable to express his gratitude except by returning the stolen jewelry and silently exiting, while she makes no attempt to stop him. In a way, L’Épouvante reminded us of Suspense, Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley’s remarkable 1913 film of a woman besieged in her house by a burglar, but the unexpected shift of emotional dynamics between the two characters in Capelanni’s film makes it equally memorable.

Capellani’s pictorial sense in real locations has been widely remarked upon. Even in La Mariée du château maudit (1910), a relatively slight tale of spooky doings in a deserted castle where a wedding party plays hide-and-seek, becomes impressive in part because of its use of an extensive set of actual ruins. There’s also a remarkable moment after the bride accidentally becomes locked in a room with a skeleton dressed in a bridal gown. She reads an old book telling of the young woman’s fate, and two successive bits of the story appear as matte shots on the right and left leaves of the open book. (Working at Pathé, Capellani could use impressive special effects, as the dream image in the Aladin frame at the top demonstrates.)

The sets are masterful as well. I was particularly struck by Jean Valjean’s desk in the second episode of Les Misérables (1912). It creates an effect of forced perspective that is like German Expressionist eight years ahead of its time. Valjean has escaped from prison and become a mayor and successful small-factory owner. Javert, formerly a guard at the prison and now a local police officer, suspects Valjean of being the fugitive. Now he comes to Valjean’s office to introduce himself.

Valjean sits at the left behind an enormous desk which dominates the left and center of the screen; its size is exaggerated by rows and stacks of thick volumes ranged across its top. About a third of the screen is empty at the right, where Javert enters at the rear and walks only partway forward. The effect is to make Javert appear smaller than he really is, with the low camera height that Pathé films were using by this point exaggerating the effect; during part of the scene he is also partially blocked by the desk. The suggestion is that he has no ability to follow up his suspicions of such a powerful man.

In a subsequent scene, when Valjean brings the ailing worker Fantine to his office, the desk has been moved away from the camera, which frames the scene from further to the right. The result is a far more open space at the right, while Valjean brings forward a chair for Fantine that puts her in front of the desk. Unlike Javert, she is not dwarfed by the desk, which, once Valjean comes to lean over her, is barely visible. Instead, the right half of the screen is left unoccupied so that a flashback can fill it.

In the scene like the one with Javert, a German Expressionist film would have exaggerated the size of the desk even further and perhaps tilted the floor up at the rear, but the effect is clear and dramatic enough as it is. Again, it is not an effect one would expect to find in a film of the early 1910s. There is also a contrast between the massive desk and the relatively small, insubstantial table that Javert uses as a desk in the setting of the police headquarters

Even the most conventional films receive what I began to recognize as Capellani touches, often to bring a moment of realism into a fantasy or melodramatic setting. In Cendrillon, the gardener who carries in a huge pumpkin to be turned into the heroine’s magic coach exits wiping the sweat from his head with a handkerchief (below left). The little girl who falls out of a window to her death in Pauvre mère leaves a large, dramatic splotch of blood on the sidewalk when her lifeless body is lifted—a realistically gory touch of a sort which I don’t recall seeing in any other film of this era (below right). When the hero finds the magic lamp in Aladin ou la lampe merveilleuse, he blows dust off it and turns it over to shake out further dirt (see bottom).

Another sort of touch appears in La Mort du Duc D’Enghien, a carefully executed motif of a sort one doesn’t often see in films of this type. The hero is arrested while at a hunting lodge, and throughout he wears a distinctive hat that’s probably part of a hunting outfit. He throws it defiantly to the floor during the courtroom scene in which he is unjustly condemned; he throws it down again in his cell, this time to indicate despair and exhaustion; in the final execution scene, he tosses it aside as part of his brave resignation, facing the firing squad with open arms and without a blindfold. These moments aren’t stressed, and one could understand the plot perfectly well without noticing the repetition. Still, the motif helps characterize D’Enghien quickly in this relatively short film and indicates the care with which Capellani was crafting even his one-reelers.

Mariann was somewhat apologetic about La Glu, a 1913 feature, since it centers around a femme fatale who victimizes three men in the course of the narrative. The title is the heroine’s nickname, and it means what it sounds like, “glue,” and particularly sticky substances like bird-lime that are used to ensnare. But the audience thoroughly enjoyed this distinctly absurd but entertaining and fast-paced tale of a heartless, mercenary woman, played with relish by Mistinguett, and the men foolish enough to fall for her. After all, there are plenty of depictions of love-’em-and-leave-’em men from this period, so why not turn the tables? At least one flagrant coincidence brings all of them to the south of France, where the heroine goes for a vacation, and Capellani contrasts the early scenes of high-society Paris with the stark seascapes in and around a fishing village. Though another literary adaptation (from a novel and play by Jean Richepin), this film certainly stands out among the pre-war features and demonstrates once more Capellani’s versatile ability with a range of genres.

After all these treats, the last French feature on offer, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914), proved a slight let-down. Capellani had a penchant for substituting letters and other texts for intertitles, but this film pushes the device to the point where sometimes it seemed as if every other shot was an insert. The plot, dealing with a scheme to rescue the imprisoned Marie Antoinette, was also frustratingly complicated and not presented with the admirable clarity that characterizes most of the other films. As I’ve mentioned, Capellani was often able to generate an empathy with the characters which is rare for films of this period, but as a result of the constant plot twists, the Chevalier and his endangered mistress remain rather remote figures. There are some effective moments, though. One exterior view of the protagonist’s home places a door at the upper center, approached by a symmetrical pair of staircases running to the right and left and forming a pyramid shape. A foreground pond elaborates the space still further, so that when a crowd tries to break in, the staging utilizes the frame vertically and horizontally, with intricate movements of individuals to avoid the water.

Ahead of his time–up to a point

As I remarked in an entry on last year’s festival, L’assommoir struck me as looking like it had been made in 1912 or 1913 rather than 1909. Now it becomes clear that many of Capellani’s films give this sense of trying things that other filmmakers would begin doing routinely a few years later. In some cases, like L’Arlésienne, it’s a focus on acting of a sort that we associate with Griffith’s films like The Mothering Heart or The Painted Lady. In others, it’s the motifs or the subtle changes of framing or the eye for landscapes. Although the editing is not usually flashy, Capellani is good at keeping spatial relationships clear, as the series of shots depicting Valjean’s escape from prison in the first part of Les misérables demonstrates. As Mariann wrote, he seemed able to adapt to any genre. I’m not a particular fan of the historical films so common during this period, but Capellani manages to humanize most of his.

It was only with Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge that the sense of Capellani being ahead of most of the directors of his time largely disappeared, though it seems premature to judge from a single 1914 film. Perhaps during the immediate pre-war era, and especially the creatively fecund year of 1913, the exploration of the cinema by an increasing number of masters created a spurt that he did not participate in. And perhaps more films from 1913 and 1914 will appear in next year’s retrospective and give us a better sense of how his career developed in that crucial period. It will also be interesting to trace his assimilation of the developing classical Hollywood norms once he moved to the U.S. By 1919 and The Red Lantern, he clearly had absorbed the norms thoroughly, and his style had become indistinguishable from that of his American colleagues.

Added July 13: Roland-François Lack has kindly written to point out that another Capellani film exists on DVD. (Thanks, Roland-François!) His 1908 version of the French tale Peau d’âne was included as a supplement on the  collector’s edition of Jacques Demy’s film of the same name. It is also included in the “Intégrale Jacques Demy” 12-disc set. These DVDs are Region 2 (Europe) and won’t work on other region-coded players.

collector’s edition of Jacques Demy’s film of the same name. It is also included in the “Intégrale Jacques Demy” 12-disc set. These DVDs are Region 2 (Europe) and won’t work on other region-coded players.

The source of the print isn’t clear on the disc. (It’s another one that hasn’t been shown at Bologna.) Probably Pathé’s own archive, since there’s a little rooster-shaped bug superimposed at the lower left in every shot.

It’s a fairly contrasty print with replaced intertitles in French only. It also seems to be running at 24 fps or something close to it. The action zips right along, which is a pity. There’s a lot of carefully executed pantomime-style acting. It’s impossible to catch all the gestures, especially since there are often three or four actors going at it at the same time. It would actually be a good film for teaching about the acting styles of this period if one could just slow it down.

I wouldn’t have spotted this as a Capellani film if I hadn’t known its source when I watched it. Still, it has some of the traits we’ve recently come to associate with him. The meeting between the heroine and Prince Charming takes place in a carefully chosen setting with a reflecting pond in the foreground. It looks like the film was shot on a hazy day, but it looks as though the camera may be set up to shoot with the sunlight at the characters’ backs.

The film also has the director’s typical elaborate interior sets juxtaposed with a dramatic use of real exteriors. The frame at the left below shows the fairy appearing for the first time to the princess. It’s not easy to see, but the busy interior includes a deep, diagonal space with several arches decorated with portraits that are painted, frames and all on the square pillars. Once the heroine disguises herself and flees to avoid her suitors, Capellani goes on location, using an impressive château and streets that look like they are in the same vicinity.

I hope that some of the more realistic films will soon appear on DVD. Lobster in particular could make their newly restored L’Arlésienne available.

The Cross

The Puffy Chair (2005).

Mark: [The actors] need to improvise. They need to find the moments, and we don’t let them lean on the script too much. We want them to try to reinvent some of the dialogue and make it fresh.

Jay: We don’t do any blocking. Our whole goal is just to set up a room and basically foster an interaction that we feel is interesting and real.

Mark: And spontaneous.

Jay: And spontaneous.

Jay and Mark Duplass, talking of their new film Cyrus.

DB here:

We don’t do any blocking. Dude, we noticed. In The Puffy Chair, the Duplass brothers typically settle the actors into one spot and pan or cut between them.

Seldom do the characters move around the setting. When they do, it’s usually by means of a walk-and-talk traveling shot that transitions to the next static layout of actors.

We are talking about filmmakers who refuse the challenge of staging.

At the other extreme of budget and commercial clout, consider another film by two brothers. In The Matrix Reloaded, Neo meets the Oracle in the virtual courtyard and sits on a bench with her.

The whole scene, which runs nearly seven minutes, contains 94 remarkably static shots. After Neo settles on the bench beside her, we get simple reverse shots—lots of them, mostly one per line of dialogue. The setups are maniacally repeated. There are thirty-one iterations of the first framing below and eighteen of the second.

The only variation is a slightly tighter framing on each character, creating another brace of single setups during Neo’s acknowledgement of his dream of Trinity’s death. Each of these gets nine iterations.

Sustained two-shots would have let the actors do more with their upper bodies, but in this string of singles, faces and dialogue have to present Neo’s reactions to his new mission to save Zion. Granted, there are seven shots showing both Neo and the Oracle in the same frame, but these are very brief and seem to be there simply to provide beats and add some variety to the load of exposition the scene must carry.

Breaking the scene up so much has interesting rhythmic implications. Paradoxically, our movies are cut very fast but they feel rather slow (and run very long). When we need a cut to see a character’s reaction, a scene plays out more slowly than if the characters were held in the same frame for a significant period. Then we might see Neo’s reactions while the Oracle is speaking, rather than having to wait for them afterward.

But my main point is that the actors are planted in one spot. Like the Duplasses, the Wachowski brothers have felt no need to imagine the characters’ interaction through blocking. Indeed, when shooting a conversation, most of today’s filmmakers seem happiest if the actors stay riveted in place—standing, seated, riding in a car, typing at a computer terminal. Improvised cinema or storyboard cinema: Both camps are refusing the challenge of staging.

In some books and some web entries (most recently, here and here and here and here), I’ve tried to trace the rich tradition of ensemble staging. From almost the start of cinema, filmmakers have explored creative ways of moving actors around the set, aiming at both engaging storytelling and pictorial impact. Since the 1960s, on the whole, this tradition has been waning. Now, I fear, it has nearly disappeared.

I’m not going to reiterate those earlier arguments. Instead I want to talk about one simple staging tactic that directors almost never employ today. I offer it at no cost to young directors. Try it! You might get a taste for a range of cinematic expression that is nowadays neglected.

Cross and double cross

Assume you have two characters in a set. At a crucial moment, you invent some business that lets them exchange places, so that the one on the left winds up on the right, and vice-versa. At a minimum, this gives you visual variety; it keeps the viewer’s attention engaged by refreshing the composition. It can of course also heighten dramatic impact.

Naturally, we expect to find the Cross in the first golden age of cinematic staging, the 1910s. Here’s a case that combines the cross with depth staging, from the Doug Fairbanks picture The Matrimaniac (1916).

Marna and the Court officer have switched places in the frame. Note especially that her movement to the right, clearing our view of the officer at the door, is motivated by her hesitation at following him. Actually such moments probably don’t need much motivation; the flow of the action is so quick that no viewer will ask why she moved to the right, since our attention is on what her action reveals.

One way to motivate the Cross is to have A turn sharply away from B but keep talking. This is a bit of actor’s business that seems far more common in the classical era of moviemaking. Here is an excerpt from a single-shot scene in Budd Boetticher’s The Tall T (1957). Brennan tries to console Mrs. Mrs. Mims, who has realized that her husband betrayed her. He enters the shack and then walks past her, as if considering exactly how to calm her.

This has been the prelude to a more intense confrontation. She comes closer to the camera, and Brennan joins her, forcing her to look at him as he says they must concentrate on staying alive.

In Demy’s Lola (1961) the Cross is motivated by the urge to offer another emphatic view of the protagonist. Roland has been talking to the two mother-figures who run the café he frequents. He’s dragging himself off to work as Jeanne fetches her radio from the bar and goes into the back room. We get two Crosses.

The shot’s climax comes when Roland pauses in the foreground and says: “One day I’ll go away too.” Again, a key character is turned from the other but continues to speak.

No need to cut in to a close-up because Roland’s face is perfectly visible. Just as important, while his face shows a certain reverie, his nervousness is conveyed by the way he waggles the novel in his hand. The actor is given a chance to act, not just with line reading and facial expression but with his slumped posture and his arms—one casual, the other in anxious motion. Taken together, the body and the face present Roland’s confusion.

Crossfire

Don Siegel’s The Big Steal (1949) yields many offhand instances of the Cross, indicating how taken for granted the technique was in studio films. When the slippery Fiske invites Joan in, she comes to the left foreground and he moves to the right side of the frame to shut the door.

Approaching her by stepping into medium shot, he tries to warm her up, but she slaps him. Cut in to underscore her reaction. “What did you expect—kisses?”

In a return to the earlier setup, she turns away and executes another Cross, settling on the sofa.

Simple and concise; some would say banal. But compared to The Puffy Chair and The Matrix Reloaded, it looks brisk. The characters move easily through the frame without camera arabesques, and the medium shot is saved for the slap. The single of Joan adds another spike to the drama. Close-ups no longer rule but are used for momentary emphasis.

So the Cross can be sustained by cutting and camera movement. In The Lady Is Willing, Liza has found a baby and called a pediatrician. Director Mitchell Leisen gives us an over-the-shoulder shot of her and at the close of it she walks around Dr. McBain’s arm, with her feathery hat brushing his face.

If the shot were sustained with a pan, we’d have a Cross, but instead there’s a cut to Liza continuing the movement. McBain turns to watch her.

He starts to follow her diagonally. When she pauses to face him, the Cross is completed.

They leave the room. After a cutaway shot showing Liza’s secretary, the camera pans to follow McBain into depth washing his hands. When he comes through the door past Liza, we get another Cross.

With positions switched, the camera travels with her as she catches up with him in a medium shot. He is opening his medical bag.

This pause enables Leisen to underscore a key line of dialogue. “I detest children of all ages. I detest infants particularly.”

One more Cross and the shot is done. The camera pans again to follow McBain bending over the child, and Liza slips into the shot behind him, remonstrating with him. “A man who dislikes children simply can’t be a baby specialist.”

As so often, the Cross is used to present one character turning from another, or one trying to catch up with another who for dramatic reasons plows ahead. And the Cross favors a moderate depth, not the eye-smiting foregrounds of Welles but something less aggressive. In these ways, the simple device can participate in a broader pattern of fluid craftsmanship. The action can unfold in a clean rhythm, consistent with what Charles Barr calls “gradation of emphasis.” Story points arise smoothly out of the flow of behavior. Actors get a chance to use their whole bodies, to create character through posture or stance, or even the angle of the elbows. Imagine if Dietrich, in the left shot just above, had sauntered to McBain with her hand on her hip as she does in so many other movies; the scene would take on a different tint.

When thinking about staging, we usually invoke Renoir or Ophuls or Jancsó, directors who integrate complex choreography with complicated tracking shots. (They also use the Cross a lot.) My examples try to show that even simple camerawork can enhance the performers’ grace. Nor do they have to execute the calisthenics on display in the office scenes of His Girl Friday. The modest moves we see in The Big Steal and The Lady Is Willing are within the grasp of eager filmmakers and game actors.

Cross purposes

I don’t have a good explanation for why such simple staging tactics have gone out of fashion. It’s too easy to cite laziness or lack of imagination, though they may play a role. I wonder as well if complicated staging is much taught in film schools. More specifically, improvisational methods may actually inhibit creative blocking. An actor who’s winging it may be reluctant to shift around the set, for fear that this creates new problems for framing or lighting or the other performances. Better, the actor may think, to concentrate on line readings, expressions, and other things that she can control while staying rooted to the spot. And maybe our directors don’t want to work their actors too hard, especially when the actors are beginners or nonprofessionals, as we find in indie filmmaking. Yet some masters of supple, intricate staging, such as Hou Hsiao-hsien, employ untrained performers.

Contemporary directors may have a more principled objection to the older staging style: It’s too artificial. In real life, people mostly chat with each other when they’re sitting down, or walking, or riding in a car. Static staging, some might say, captures the passive nature of everyday interactions.

But dramatic narrative typically doesn’t consist of ordinary life. A film offers heightened, focused, pointed encounters, shot through with meaning and feeling. The actors and the filmmaker have a chance to sharpen the viewer’s perception of the situation and pass along the moment-by-moment play of thought, emotion, and action. There are both loud and quiet ways of doing this. Antonioni’s famously “dedramatized” scenes are staged as dynamically as the more florid moments of Visconti or Fellini. Emotionally subdued action can be shaped just as precisely as passionate outbursts, and it can carry its own impact.

I should make it clear that I’m not asking anybody to embrace a single style. Sometimes stand-and-deliver and intensified continuity editing work very well. Directors will always seek specific solutions to the problems of a scene. But I don’t see much variety in the solutions many people now pursue. I don’t see evidence that most young filmmakers around the world are aware that traditions furnish lots of alternatives.

In earlier periods, some directors were as editing-oriented as today’s mainstream ones, while other directors adopted more staging-driven approaches. But either sort had a broader palette than what we see today. Any accomplished director could stage a conversation in a variety of ways. Just to take Demy, some scenes in Lola are handled in full shots like the one highlighting Roland in the café. Other scenes are broken up into tight singles, and still others are treated in two-shots.

All the classical films I’ve mentioned are pluralistic in their technical choices. Today, though, we see more uniformity, or rather conformity.

Cinephile conversation on the internet is currently rippling around a controversy about “slow cinema.” Whatever that rough category covers, it surely includes those festival films that put the camera in one spot per scene and simply observe. I’d argue that many of these minimalist movies are also AWOL when it comes to staging. After watching a long-take, flatly shot film with me, a Hong Kong filmmaker friend remarked, “This sort of thing is just too easy.” One difference between a solid “slow film” and an empty one, I suspect, lies in the extent to which the filmmakers explore the resources of staging. How do we know? We have to analyze the films. (More on this matter here.) Absent that analysis, critics’ appeals to realism or meditative restfulness or “time flowing through the shot” risk becoming alibis for inert moviemaking.

Many young directors want to be innovative. They want to shake things up. This is a good impulse. The way things are going, the ambitious way forward is obvious: Go backward. Avoid stand-and-deliver. Avoid walk-and-talk. Get your actors on their feet and move them around the setting. Invent bits of business that let them crisscross the frame, laterally and in depth. Dynamize all areas of the shot. In the process you may discover new dimensions of creativity.

The Cross is only one tactic, but I think it’s useful as a way to sensitize ourselves to staging. The best way to understand staging is to watch, really watch, a lot of classic cinema from Hollywood and elsewhere. When you’re ready for the hard stuff, Mizoguchi is waiting.

I expect disagreements with my criticisms of contemporary film technique, so I hope skeptics will consider my more extensive arguments in On the History of Film Style, Figures Traced in Light, and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I haven’t found references to what I call the Cross in manuals of direction. The closest technique, and the one that called my attention to the possibilities of the technique, is what Mike Crisp in his valuable book The Practical Director (first ed., 1993) calls the “rise and cross.” This refers to actors getting up from sit-down conversations in one spot and moving to another sit-down area, while switching position in the frame. I’ve expanded the idea to cover a broader variety of situations.

As far as I can tell, my term doesn’t have much in common with the stage direction “Cross,” which you’ll find in play scripts. Janie Jones provides definitions here. While staging in film is in many respects different from that in theatre, I think that moviemakers can find intriguing practical ideas in Terry John Converse, Directing for the Stage.

Alicia Van Couvering’s interview with the Duplass brothers, “Don’t you want me?”, is published in Filmmaker 18, 3 (Spring 2010; not yet available online); my quotation is from p. 43. In his essay Slow Cinema Backlash, Vadim Rizov argues that lesser attempts at “slow cinema” have led to a somewhat predictable style.

Raining in the Mountain (King Hu, 1979).

Class of 1960

DB here:

By now most people accept the idea that 1939 was a kind of Golden Year of cinema. You know, Rules of the Game, Stagecoach, Wizard of Oz, that movie about the Civil War, etc. TCM has even made a movie about 1939. On this site Kristin and I have talked about earlier wonder years, like 1913 and 1917. So in planning this year’s Bruges week-long Zomerfilmcollege (aka Cinephile Summer Camp), Stef Franck and I discussed building my lectures around a single year. I proposed 1941, but he countered with 1960.

1960 was a logical choice in providing spread for the whole program. At Bruges we intertwine several threads of lectures and screenings, and this year we had silent films (The Cat and the Canary, The Wind), Hollywood’s cinema of emigration (Florey, Siodmak, Ophuls, etc.), and contemporary Korean film. All in 35mm, of course. So picking 1960 filled in another area.

As so often happens, a contingent choice came to seem a necessary one. By the time I opened my mouth to introduce The Bad Sleep Well, I had convinced myself that 1960 was another watershed year. Consider these releases:

Rocco and His Brothers (Visconti), La Dolce Vita (Fellini), L’Avventura (Antonioni), Le Testament d’Orphée (Cocteau), Plein Soleil (Clement), À bout de souffle (Godard), Les Bonnes femmes (Chabrol), La Verité (Clouzot), The Bridge (Wicki), Wild Strawberries (Bergman), The Devil’s Eye (Bergman), Lady with the Little Dog (Heifetz), The Letter that Wasn’t Sent (Kalatozov), The Steamroller and the Violin (Tarkovsky short), The Teutonic Knights (Alexander Ford), Innocent Sorcerors (Wajda), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Reisz), Tunes of Glory (Neame), Sergeant Rutledge (John Ford), Psycho (Hitchcock), Spartacus (Kubrick), Elmer Gantry (Brooks), 101 Dalmatians (Disney/ Reitherman), The Magnificent Seven (Sturges), Exodus (Preminger), Home from the Hill (Minnelli), Comanche Station (Boetticher), Verboten! (Fuller), The Bellboy (Lewis), The Young One (Buñuel), TheYoung Ones (Alcoriza), The Shadow of the Caudillo (Bracho), Devi (Ray), The Cloud-Capped Star (Ghatak), This Country Where the Ganges Flows (Karmakar), Red Detachment of Women (Xie Jin), The Back Door (Li Han-hsiang), Enchanting Shadow (Li Han-hsiang), The Wild, Wild Rose (Wang Tian-lin), Desperado Outpost (Okamoto), Spring Dreams (Kinoshita), When a Woman Ascends the Stairs (Naruse), Daughter, Wives, and Mother (Naruse), Cruel Story of Youth (Oshima), The Sun’s Burial (Oshima), Night and Fog in Japan (Oshima), The Island (Shindo), Pigs and Battleships (Imamura), Sleep of the Beast (Suzuki), and Fighting Delinquents (Suzuki).

We didn’t show any of them.

Several factors constrained our choices, including the availability of good prints with Dutch subtitles, or at least English ones. We also didn’t want to run too many official classics. And we fudged a little for pedagogy’s sake. We had to include a Godard, but instead of À bout de souffle, we picked Le Petit soldat—made in 1960 but not released until 1963. The World of Apu was released in 1959 in India, though it made its world impact in the following year. Lola was finished in 1960 but released in early 1961. A dodge, but I wanted a Nouvelle Vague counterpoint to Godard, and it fit well with the Ophuls thread, and—well, it’s Demy. In any case, we wound up with a list of outstanding movies.

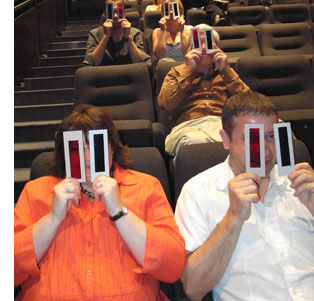

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

Running alongside my titles were horror films and thrillers from the same year, including Peeping Tom, Black Sunday, The Leech Woman, and Corman’s House of Usher. William Castle’s 13 Ghosts was shown with reconstructed versions of the original two-color Ghost Viewers. (Look through red if you believe in ghosts, blue if you don’t.) Imagine the shot above through a red filter. The creature, pink on the print, turns satanically crimson—confirmation that ghosts exist, although they look less like Casper and more like those Red Devil candies you ate in theatres as a kid. In a prologue, available here, Mr. Castle explains it all.

All in all, quite a week. My sessions ran from 9:00 AM to 12:30 or 1:00 PM, with the film embedded. After lunch, there were more talks and screenings, usually winding up at about 1:00 AM. Other speakers included Kevin Brownlow, Tom Paulus, Steven Jacobs, Muriel Andrin, Egbert Barten, and Christophe Verbiest (linking his talks on contemporary Korean film to the absolutely nuts 1960 Kim Ki-yong melodrama The Maid). The locals’ lectures were in Dutch, but these worthies are fluent in English, so sharing meals with them allowed me to catch up with their ideas.

Pegging a batch of movies to a single year can seem gimmicky, so I treated the films as exemplifying different trends, many of which started before 1960 and have continued since. I concentrated on trends within world film culture, though in several cases those were tied to still broader social and political developments. Above all, the 1960 frame allowed me to do the sort of comparative work I enjoy.

Generations

My first grouping was “Twilight of the Masters.” This allowed me to develop the idea that, remarkably, people who had started making films in the 1910s and 1920s were still active in the 1960s—and often making films that recalled their youthful efforts. Renoir revisited La Grande illusion in The Elusive Corporal, and Dreyer returned to his origins in tableau cinema through the staging of Gertrud.

In this connection, Fritz Lang’s 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, his final movie, revisits his Mabuse cycle in the way his previous films for Artur Brauner revise the “sensation-films” he wrote for Joe May (especially The Indian Tomb). Drawing on some ideas in my online essay, “The Hook,” we studied Lang’s crisp transitions between scenes. From this angle, 1000 Eyes is a sort of encyclopedia of ways you can connect scenes (visual link, auditory link, association of ideas, etc.). The transitions whip up a breathless pace and steer past some plot holes, and sometimes they generate a level of mistrust, implying story possibilities that don’t turn out to be valid.

Testament’s motif of eyes and vision became expanded to television surveillance in 1000 Eyes. There might even be an oblique connection between the Hotel Luxor’s panopticon and the rise of television ownership in Europe at the period. Here, as ever, cinema doesn’t have good things to say about TV.

Twilight of another, not quite so old master: Late Autumn by Ozu. I reviewed some features of Ozu’s style and then analyzed the film as a multiple-character drama. Ozu and his collaborator Noda Kogo split up the plot in order to present different characters’ attitudes to the central situation: the question of a daughter’s marriage. The plot ingeniously withholds information about the attitude of Akiko, the mother, by deleting certain scenes that would clarify it. Here too, the old master recalls earlier films by having characters discuss their college flirtations, which invoke scenes from Days of Youth and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?

Both Billy Wilder and Akira Kurosawa furnished me with a second generational cohort. I know, probably nobody in his right mind would see common features between these two directors. But desperation can fuel audacity. Both emerged during the late 1930s, began directing in the 1940s, and enjoyed a string of great successes in the 1950s; but both fell on harder times in the 1960s. Both became accusatory living legends, haunting local industries that had kept them from working.

Leading up to The Apartment, I considered Wilder’s contribution to two trends. First, the industry had hit the doldrums. In Europe television and new leisure lifestyles were not yet the threat they would become, but in America, the industry needed to pull its audience away from the TV set and the barbecue. Wilder proved skilful in using Hollywood’s turn to sex as the basis for his cynical comedies. The Lubitsch touch, a worldly appreciation of the oblique approach to matters of sex, was replaced by something harsher. In Wilder’s world, there are mostly sharks and shnooks, those who take and those who are taken.

Second, I situated Wilder as a leading figure in the emergence of the writer-turned-director in the 1940s (Sturges, Huston, Brooks, Fuller, Mankiewicz, etc.). This encouraged me to probe his dramaturgy, and so we analyzed the taut structure of The Apartment’s plot. It has rightly been recognized as a model screenplay, making us sympathize with a careerist covering up his bosses’ infidelities, all the while whetting our interest by shifting the range of knowledge away from the protagonist at key moments. It also displays a nice interweaving of motifs that function both dramatically and metaphorically (especially Miss Kubelik’s hand mirror). Of course at the end I had to run a clip showing the influence of The Apartment on the opening of Jerry Maguire.

By the mid-1960s, however, Wilder was pushing his luck, especially with Kiss Me Stupid. In The Apartment he wanted to make “a movie about fucking,” and he predicted that some day people would do the deed onscreen. But having glimpsed the promised land of the 1970s, he was unable to enter. Despite some worthy efforts, notably The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, he haunted Hollywood as a major director who had outlived his moment.

Human, all too human

Kurosawa’s international fame came largely through the growth of the film festival as a prime institution of international movie culture. This situation let me sketch in the importance of festivals in bringing directors like him to world recognition. (By the way, Richard Porton has just brought out an informative collection of thoughts on film festivals.) With The Bad Sleep Well, I was able to talk a bit about something that is often forgotten—Kurosawa’s efforts in social, even political cinema. From Sugata Sanshiro, a tribute to Japanese martial arts, and The Most Beautiful, the loveliest movie you’ll ever see about girls making lenses for gunsights, up through Occupation projects like No Regrets for Our Youth and Scandal, Kurosawa engaged with political subject matter. Ikiru and I Live in Fear made this side of his work even more salient in the 1950s.

The Bad Sleep Well’s attack on corporate corruption sits well with this tendency. It considers the “iron triangle” of Japanese politics, the collusion of bureaucrats, politicians, and private industry—particularly the building industry, whose livelihood depends on bids for government projects. Still, it’s hard to believe that while Kurosawa made the film, and while Ozu made the serene Late Autumn, students were fighting police in the streets over the US-Japan security treaty. That turmoil surfaced in Oshima Nagisa’s demanding and formally daring Night and Fog in Japan.

The movie is shot with Kurosawa’s usual muscularity, including virtuoso compositions in what he called, following Toland, “pan-focus.”

The film’s twists also seemed to me worth examining. The protagonist is a minor presence in the first scenes, and his reticence in the beginning is mirrored in the finale, when he simply vanishes and his pal has to tell us what happened to him. Such a daring structure, reminiscent of the abrupt midway break in Ikiru, gives the film an almost Brechtian discomfiture, as well as highlighting the secondary characters’ rather perverse reaction to the hero’s fate.

Kurosawa was widely called a “humanist” director, and this concept sheds light on what we might call the “international film ideology” pervading festivals in the 1950s. In various areas of social and philosophical thought, a notion of humanism emerged out of disillusionment with the “age of ideology” that had engulfed the world in war. Several thinkers declared that the age of religious dogma and social collectivism, either Nazi or Communist, was over. Now what mattered were the features that drew people of all societies together, and the prospect of enlightened social action based on those commonalities—tolerance, respect, and a belief that people ultimately took individual responsibility for their communities. Catholics, Communists, and people of all stripes scrambled to call themselves humanists. As Dwight Macdonald, former Trotskyite, put it, “The root is man.”

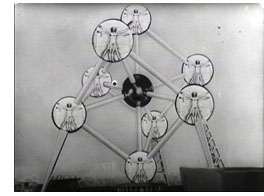

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

This frame of reference can be seen in Steichen’s 1955 photo exhibition, circulated around the world in a best-selling book, called The Family of Man, as well as in the 1958 Brussels Expo, the first major world’s fair since the war. There films like For a More Human World (frame right) presented technology, science, education, and cooperation as teaming up to improve the lives of people in all nations.

Film festivals embraced this universalism, pointing to the great films of Italy’s Neorealist trend as proof of cross-cultural communication. Although these films often scored specifically Italian political points, they could also be seen as human documents speaking to audiences anywhere. Who could not empathize with Ricci and his son in Bicycle Thieves (named at the 1958 Expo as the third-greatest film ever made)?

The turn to humanism helps answer a puzzling question: Why Satyajit Ray? Virtually no Europeans had ever seen a film from India. What enabled a director from this country to achieve worldwide renown? And why not other Indian directors of his era, such as Raj Kapoor, Guru Dutt, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak? All of these had to wait many years for discovery by European tastemakers.

For one thing, Ray was highly westernized himself. He was a child of the Bengali Renaissance, a virtuoso in many fields (he composed music, drew with facility, wrote detective stories and children’s books), and an admirer of European cinema. A stint assisting Jean Renoir exposed him to one of the greatest of Western filmmakers. A viewing of The Bicycle Thieves determined him to make films. He was skeptical of imitating Hollywood, which had been a prime inspiration for Hindu cinema. He criticized Bollywood’s reliance on schematic romance and musical numbers. If any Indian director was to make the move to the festival circuit, it would be him. (You can argue that other non-European filmmakers who made it into the fold were the most “western”—Kurosawa, Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, etc.).

Just as important, Ray’s stories suited the humanist program. Whereas Ghatak and Sen made politically charged films, Ray concentrated on the individual. In The World of Apu, social conditions are shown, but as a background to the development of personality and psychological tensions. At the film’s start, students are holding a street march demanding political rights, but they are offscreen, a backdrop to Apu’s meeting with his old professor as he gets his letter of recommendation. What follows is a drama of artistic failure, blossoming love, and a young man’s confused growth to maturity and responsibility.

It’s a simple story, rendered lyrical through constantly developing imagery: Apu stretched out prone, the famous grimy window curtain, and a cluster of visual motifs I hadn’t noticed on previous viewing. Ray’s concise direction links the torn curtain in Apu’s room to the famous (Langian?) transition from a movie screen to a carriage window, the cluster unified by associating Apurna with male children. Thanks to Andrew Robinson’s book on Ray, we know that in the carriage scene she is already thinking of the son she will bear.

It’s easy to romanticize this handsome, happy-go-lucky hero. I think the College participants thought I was a little hard on Apu, since I treated him as far from the “conscientious and diligent” young man his professor wrote of. Surely his idealistic-novelist persona is sympathetic. But if he is to grow as the film suggests, he must have failings, and Ray shows them to us—dreamy indolence, self-centeredness, even poutiness. The film is a character study, a sort of Bildungsroman tracing how Apu learns his place in his world. Our discussion after this film was particularly rich, with one participant suggesting that in accepting his son he isn’t abandoning his art entirely, but giving it human significance: He promises to tell Kajal stories.

Ray came to directing in middle age, a somewhat rare option. So too did Gillo Pontecorvo, but the latter made many fewer films. Although Kapò, isn’t as strong a movie as our other entries, it did allow us to talk a bit about coproduction, about European cinema’s relation to World War II, and about what came to be known as the morality of technique.

European coproductions are another fundamental part of the 1960 landscape, and they illustrate how economic considerations penetrate artistic choices. (Why are American and Italian actors in the “German” film 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse? Why do we find Anouk Aimée in 8 ½ and Jeanne Moreau in La Notte? Follow the money.) For the Italian production Kapò, the primary roles are taken by an American (Susan Strasberg, playing the heroine Edith) and two French actors—the concentration camp translator played by Emmanuelle Riva and the heroic Soviet soldier played by Laurent Terzieff. The film was shot in Yugoslavia.

The story centers on a young Jewish girl who, in order to survive Nazi internment, passes herself off as a Gentile and becomes a camp commandant, whipping other prisoners into line. Other Italian films of the period, notably Rossellini’s Generale Della Rovere, were dealing with issues of conscience during the war, but Kapò was apparently the first fictional feature in Western Europe to confront the Holocaust since Alessandrini’s Wandering Jew of 1947. In 1960, Adolf Eichmann had been captured by the Mossod and stood trial the following year, and after Kapò came a few other films addressing the camps, notably Wajda’s Samson (1961) and Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1965). So the film had a strong contemporary resonance; after its US release, it would be nominated for an Oscar.

One reason Stef and I picked Kapò was the controversy around Jacques Rivette’s accusation in Cahiers du cinéma that for a particular tracking shot Pontecorvo deserved “the most profound contempt.” The film, as Rivette indicates, is dominated by an already compromised conception of realism: grimed faces, make-up that hollows cheeks, somewhat ragged clothes, moderately shabby bunks. The shot shows the body of Theresa hurled against the electrified barbed wire, with the camera coasting slowly toward it. Her silhouette is almost classically composed, with the hands artfully pivoted and standing out against the sky. For Rivette this pictorial conceit is virtually obscene.

It seems to me that Rivette’s essay sought in part to reply to those who thought that Cahiers’ policy amounted to pure formalism. In calling for an ethics of technique, Rivette argues that artistic choices which might seem to be in the service of correct politics can betray a deeper immorality: using a historical cataclysm as an occasion for a safe realism and self-congratulatory flourishes. Similar complaints could be lodged against Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg and Stone’s World Trade Center. And because for the Cahiers team artistic cinema was an expression of a creator’s vision, the morally maladroit traveling shot brands the director as a man of bad faith.

Rivette isn’t saying that film artists shouldn’t try to represent historical trauma. He simply argues that other paths could be taken. For instance, Resnais’ Night and Fog and Hiroshima mon amour acknowledge that some events cannot be encompassed by normal understanding, and the form of each film enacts an effort to understand, not a fixed conclusion. What we see in Night and Fog is “a lucid consciousness, somewhat impersonal, that is unable to accept or understand or admit this phenomenon.” For Rivette, Pontecorvo seems convinced that romantic love and self-sacrifice can overcome Nazism, albeit with some help from the Red Army. He tries to explain, even prettify, an event that cannot be understood within the usual humanistic categories.

New Wave, still new

Lola.

Godard’s Le Petit soldat is far more preoccupied with uncertainties, even confusions, than Kapò is. 1960 saw an extraordinary number of former colonies, especially in Africa, gain independence, and during that year the Algerian war of resistance was spreading to Europe. Godard’s central character Bruno is working with the OAS vigilantes dedicated to killing Algerian terrorists, but when he meets the lovely Veronica Dreyer he decides to leave politics behind and flee with her to Brazil. Perhaps “decides” is the wrong word, since his actions are impulsive: he abruptly shies away from committing a political assassination, and he abruptly abandons his colleagues. But he’s captured by FLN terrorists and, in the film’s most famous sequences, tortured. At the end, he commits the assassination, not knowing that Veronica, herself in league with the Algerians, has been captured by his pals and killed. But his final voice-over is almost a shrug, and his act of murder takes on the flavor of an existentialist acte gratuite.

Le Petit soldat doesn’t offer heroic figures, as Kapò does in Theresa and the Soviet soldier. Nor does it allow us to sympathize much with the egotistical, capricious Bruno. The texture is more disjunctive, littered with the usual digressions and citations. Since the film was shot in Geneva, there’s a persistent motif of Swissness, with citations of Paul Klee. A sneaky one I never noticed before: the seduction game Bruno plays is modeled on the three fundamental shapes in the Bauhaus basic course, which Klee taught.

Having experimented with discontinuous imagery in À bout de souffle, Godard in his second feature turns his attention to the soundtrack, creating one of the most minimalist ones I know. If Bresson whittles down his soundtrack to a spare but recognizable realism, Le Petit soldat goes a step further, scrubbing out nearly every noise until we’re almost watching a silent film. Traffic scenes lack traffic noises, with only a car horn or a bit of dialogue breaking in. One passage on a train could almost be a sound loop.

The strategy of suppressed sound is carried to a paroxysm in the torture scenes, with the clink of handcuffs and the soft tapping of typewriter keys highlighted and bits of music played spasmodically…but no sounds of pain. Only during the rushed and almost throwaway climax, is something like a plausible city ambience heard. In a dichotomy that will be familiar throughout Godard’s work, there’s a split between image (Bruno is a photographer, and in the early part of the film he takes snapshots of Veronica in her apartment) and sound (the political factions rely on telephones and tape recorders, and the OAS thugs trick their way into Veronica’s apartment through sound recording).

In all, Le Petit soldat isn’t exactly fun but it’s exhilarating in its bursts and unexpected frictions. Next time somebody tells me that Godard’s technical innovations have all become commonplace, I’ll point to this film of 1960, which would be daring and demanding if released tomorrow.

Fun, albeit grave, is what Lola is all about. It takes formal artifice far beyond realism, creating a sort of non-musical musical. (It has one number, and even that is a sketchy rehearsal.) As geometrical as a minuet, its plot plays out in a hall of mirrors, where characters share names, pasts, and sentiments. The sailor Frankie and the wandering Michel, both in love with Lola, are blonde giants. Lola is actually named Cécile, and the little girl of the same name seems in some ways an early version of her, while Cécile’s mother has a dash of Lola in her past.

Roland starts out as the protagonist, but as he warms and cools and warms to Lola, the story momentum shifts to others. There’s Lola of course, and young Cécile who strikes up a friendship with Frankie, and Cécile’s mother who yearns a bit for Roland, and Michel, who left Nantes years ago and has lived in another movie, specifically, Mark Robson’s Return to Paradise (1952). Here the structure of the plot unfolds the network of relationships among people, linked mostly by casual encounters across a few days. The last section accordingly consists of a series of farewells, as if the story can end only by breaking ties of affection.

In surveying these films, I was struck by how much most of them owed to the growth of postwar institutions of film culture, and how strong those institutions remain. Coproductions and subsidies were feeding a massive buildup of European cinema. Contrary to what you might expect, as attendance cratered from the late 1950s onward, the number of European films produced went up. The EU countries still overproduce, releasing nearly 1200 theatrical features in 2008.

Film festivals were promoting not only universal humanism; they were also packaging films under rubrics of authorship or the New XXX Cinema and the Young ZZZ Cinema. 1940s Neorealism, aka “New Realism in Italian Cinema,” seems to have been, once more, the prototype. Festivals must make discoveries and emphasize novelties. At the same period film schools taught professional standards, and film archives showed classics and gave postwar filmmakers a more secure sense of the medium’s history. Lang, Ozu, and Wilder weren’t dependent on such institutions, but younger filmmakers were. And still are.

1960 is an arbitrary data point, but it stands out as an extraordinary year for quality. In addition, picking it as a benchmark allowed me to think about some important trends of the period. What probably didn’t show through my lumbering PowerPoints, with their charts, diagrams, and frame enlargements, was how much I learned from my Bruges stay. One of the deep satisfactions of teaching is remembering, no matter how confidently you declare your claims, how much more there is to know. Of things cinematic there is no end.

We also asked participants to read Serge Daney’s essay, “The Tracking Shot in Kapò.” Daney’s elaborate exercise in autobiography, irony, and moral reflection could not be plumbed in the time at my disposal, there or here. But it did help me understand Rivette’s argument. In preparing my lectures, I also owed a debt to some excellent books, notably Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity; Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye; Carlo Celli, Gillo Pontecorvo: From Resistance to Terrorism; and Richard Brody, Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard. As ever, the invaluable documentation provided by the print editions of Screen Digest over the years enabled me to compile my tables of attendance, releases, and the like.

Late Autumn.

P.S. 3 Aug: Stef has posted snapshots from our Zomerfilmcollege here.

P.P.S. 3 Aug: This helpful correction from Roland-François Lack on Le Petit Soldat:

One small point: the organisation Bruno works for cannot be the O.A.S., which wasn’t active until the end of 1960.

He is working, rather, for ‘La main rouge’, a government sponsored counter-terrorist agency run by a Colonel Mercier (hence the name of Bruno’s associate).

Nice! Thanks.

In critical condition

DB here:

A Web-prowling cinephile couldn’t escape all the talk about the decline of film criticism. First, several daily and weekly reviewers left their print publications, as Anne Thompson points out. Then one of our brightest critics, Matt Zoller Seitz, suspended writing in order to return to film production. This and the departure of another web critic, Raymond Young of Flickhead, has prompted Tim Lucas to ponder, at length and in depth, why one would maintain a film blog. Go to Moviezzz for a summing up.

I’ve been teaching film history and aesthetics since the early 1970s, but before that I wrote criticism for my college newspaper, the Albany Student Press, and then for Film Comment. When I set out for graduate school, film criticism was virtually the only sort of film writing I thought existed. Auteurism was my faith, and Andrew Sarris its true apostle (for reasons explained in an essay in Poetics of Cinema). In grad school, I learned that there were other ways of thinking about cinema. Since then, I’ve tried to steer a course among film criticism, film history, and film theory—sometimes doing one, sometimes mixing them. But criticism has remained central to my interest in cinema.

What, though, does the concept mean? I think that some of the current discussions about the souring state of movie criticism would benefit from some thoughts about what criticism is and does.

Watch your language

Consider criticism as a language-based activity. What do critics do with their words and sentences? Long ago, the philosopher Monroe Beardsley laid out four activities that constitute criticism in any art form, and his distinctions still seem accurate to me. (1) We use them in Chapter 2 of Film Art.

*Critics describe artworks. Film critics summarize plots, describe scenes, characterize performances or music or visual style. These descriptions are seldom simply neutral summaries. They’re usually perspective-driven, aiding a larger point that the critic wants to make. A description can be coldly objective or warmly partisan.

*Critics analyze artworks. For Beardsley, this means showing how parts go together to make up wholes. If you simply listed all the shots of a scene in order, that would be a description. But if you go on to show the functions that each shot performs, in relation to the others or some broader effect, you’re doing analysis. Analysis need not concentrate only on visual style. You can analyze plot construction. You can analyze an actor’s performance; how does she express an arc of emotion across a scene? You can analyze the film’s score; how do motifs recur when certain characters appear? Because films have so many different kinds of “parts,” you can analyze patterns at many levels.

*Critics interpret artworks. This activity involves making claims about the abstract or general meanings of a film. The word “interpret” is used in lots of ways, but in the sense meant here, figuring out the chronological order of scenes in Pulp Fiction wouldn’t count. If, though, you claim that Pulp Fiction is about redemption, both failed (Vincent) and successful (Jules’ decision to quit the hitman trade), you’re launching an interpretation. If I say that Cloverfield is a symbolic replay of 9/11, that counts as an interpretation too.

*Critics evaluate artworks. This seems pretty straightforward. If you declare that There Will Be Blood is a good film, you’re evaluating it. For many critics, evaluation is the core critical activity; after all, the word critic in its Greek origins means judge. Like all the other activities, however, evaluation turns out to be more complicated than it looks.

Why break the process of criticism into these activities? I think they help us clarify what we’re doing at any moment. They also offer a rough way to understand the critical formats that we usually encounter.

In paper media, on TV, or on the internet, we can distinguish three main platforms for critical discussion. A review is a brief characterization of the film, aimed at a broad audience who hasn’t seen the film. Reviews come out at fixed intervals—daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly. They track current releases, and so have a sort of news value. For this reason, they’re a type of journalism.

An academic article or book of criticism offers in-depth research into one or more films, and it presupposes that the reader has seen the film (or doesn’t mind spoilers). It isn’t tied to any fixed rhythm of publication.

A critical essay falls in between these types. It’s longer than a review, but it’s usually more opinionated and personal than an academic article. It’s often a “think piece,” drawing back from the daily rhythm of reviewing to suggest more general conclusions about a career or trend. Some examples are Pauline Kael’s “On the Future of Movies” and Philip Lopate’s “The Last Taboo: The Dumbing Down of American Movies.” (2) Critical essays can be found in highbrow magazines like The New Yorker and Artforum, in literary quarterlies, and in film journals like Film Comment, CinemaScope, and Cahiers du Cinéma.

Any critic can write on all three platforms. Roger Ebert is known chiefly for his reviews, but his Great Movies books consist of essays. (3) J. Hoberman usually writes reviews, but he has also published essays and academic books. And the lines between these formats aren’t absolutely rigid, as I’ll try to show later.

Reviewing reviewers

How do these forums relate to the different critical activities? It seems clear that academic criticism, the sort published in research articles or books, emphasizes description, analysis, and interpretation. Evaluation isn’t absent, but it takes a back seat. Usually the academic critic is concerned to answer a question about the films. How, for instance, is the theme of gender identity represented in Rebecca, and what ambiguities and contradictions arise from that process? In order to pursue this question, the critic needn’t declare Rebecca a great film or a failure.

Of course, the academic piece could also make a value judgment, either at the outset (I think Rebecca is excellent and want to scrutinize it) or at the end (I’m forced to conclude that Rebecca is a narrow, oppressive film). But I don’t have to pass judgment. I have written about a lot of ordinary films in my life. They became interesting because of the questions I brought to them, not because they had a lot going for them intrinsically.

The academic article has a lot of space to examine its question—several thousand words, usually—and of course a book offers still more real estate. By contrast, a review is pinched by its format. It must be brief, often a couple of hundred words. Unlike the academic critique, the review’s purpose is usually to act as a recommendation or warning. Most readers seek out reviews to get a sense of whether a movie is worth seeing or even whether they would like it.

Because evaluation is central to their task, reviewers tend to focus their descriptions on certain aspects of the film. A reviewer is expected to describe the plot situation, but without giving away too much—major twists in the action, and of course the ending. The writer also typically describes the performances, perhaps also the look and feel of the film, and chiefly its tone or tenor. Descriptions of shots, cutting patterns, music, and the like are usually neglected. And what is described will often be colored by the critic’s evaluation. You can, for instance, retell the plot in a way that makes your opinion of the film’s value pretty clear.

Reviews seldom indulge in analysis, which typically consumes a lot of space and might give away too much. Nor do reviewers usually float interpretations, but when they do, the most common tactic is reflectionism. A current film is read in relation to the mood of the moment, a current political controversy, or a broader Zeitgeist. A cynic might say that this is a handy way to make a film seem important and relevant, while offering a ready-made way to fill a column. Reviewers don’t have a monopoly on reflectionism, though. It’s present in the essayistic think-piece and in academic criticism too. (4)

The centrality of evaluation, then, dictates certain conventions of film reviewing. Those conventions obviously work well enough. But we can learn things about cinema through wide-ranging descriptions and detailed analyses and interpretations, as well. We just ought to recognize that we’re unlikely to get them in the review format.

The good, the bad, and the tasty

Let’s look at evaluation a little more closely. If I say that I think that Les Demoiselles de Rochefort is a good film, I might just be saying that I like it. But not necessarily. I can like films I don’t think are particularly good. I enjoy mid-level Hong Kong movies because I can see their ties to local history and film history, because I take delight in certain actors, because I try to spot familiar locations. But I wouldn’t argue that because I like them, they’re good. We all have guilty pleasures—a label that was coined exactly to designate films which give us enjoyment, even if by any wide criteria they aren’t especially good.

They needn’t be disastrously bad, of course. I do like Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, inordinately. It’s my favorite Demy film and a film I will watch any time, anywhere. It always lifts my spirits. I would take it to a desert island. But I’m also aware that it has its problems. It is very simple and schematic and predictable, and it probably tries too hard to be both naive and knowing. Artistically, it’s not as perfect as Play Time or as daring as Citizen Kane or as….well, you go on. It’s just that somehow, this movie speaks to me.

The point is that evaluation encompasses both judgment and taste. Taste is what gives you a buzz. There’s no accounting for it, we’re told, and a person’s tastes can be wholly unsystematic and logically inconsistent. Among my favorite movies are The Hunt for Red October, How Green Was My Valley, Choose Me, Back to the Future, Song of the South, Passing Fancy, Advise and Consent, Zorns Lemma, and Sanshiro Sugata. I’ll also watch June Allyson, Sandra Bullock, Henry Fonda, and Chishu Ryu in almost anything. I’m hard-pressed to find a logical principle here.

Taste is distinctive, part of what makes you you, but you also share some tastes with others. We teachers often say we’re trying to educate students’ tastes. True, but we should admit that we’re trying to broaden their tastes, not necessarily replace them with better ones. Elsewhere on this site I argue that tastes formed in adolescence are, fortunately, almost impossible to erase. But we shouldn’t keep our tastes locked down. The more different kinds of things we can like, the better life becomes.