Archive for the 'National cinemas: Taiwan' Category

Early Hou Hsiao-hsien: Film culture finally comes through (a repost)

The Green, Green Grass of Home (1982).

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1094 entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed.

DB here:

In March, the Criterion Channel will be featuring a selection of early films by the great Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. These have been very hard to see in the West; I went to Brussels and Taipei to watch prints back in the 1990s. For those who admire his later works, they are absolutely necessary, and for the casual viewer they’re great fun. Two of them, Cute Girl and Green, Green Grass of Home are lilting musicals, while The Boys from Fengkuei is a wandering-youth story with affinities to coming-of-age films like Fellini’s I Vitelloni. (Too bad the series couldn’t include his second feature, Cheerful Wind.) My effort tries to show how a basic technical choice that Hou made created powerful effects on his visual style.

Because the frames are so dense with information, you may want to enlarge them as you go. For a fuller examination of Hou’s work across his career, there’s a chapter in Figures Traced in Light and a video here. The original blog, posted on June 6, 2016, was an attempt to fill in areas I didn’t have room to include in the book. If you’re unfamiliar with Hou’s major works, you should probably watch the video before reading the recycled entry.

For today, let’s call “film culture” that loose agglomeration of institutions around non-mainstream cinema. Film culture includes art house screening venues, festivals, magazines like Film Comment, Cinema Scope, and Cineaste, distribution companies (Janus/Criterion, Milestone, Kino Lorber et al.), critical websites, and not least the new channels of distribution and exhibition like Fandor, Mubi, and the impending FilmStruck.

Although the system is decentralized, there’s usually a fairly predictable flow of films through it. A film is shown at festivals, written up by critics, and picked up by distributors. Then it gains some exposure in theatres or more festivals, and it eventually becomes available on DVD, cable, and streaming services. And now we expect the process to move fairly quickly. Mustang played Cannes and many festivals through summer of 2015; it moved to theatres in the US and elsewhere in the fall. Only a year after its premiere, you can buy it on disc.

We’ve also been aided by the emergence of multi-standard video players and the willingness of some disc-publishing companies to release versions with subtitles in several languages. All too often, though, “film culture” displays gaps and delays. It took six years for Asgar Farhadi’s wonderful About Elly (2009) to make its way to minimal visibility in the US. Fans of Godard have been prepared to wait years to see his many films that didn’t get even video release in English-speaking territories. (Soigne ta droite! played Toronto in 1987, never got a theatrical release in America, and showed up on US DVD in 2002; the Blu-ray came out eleven years after that.) Two of the most egregious examples of this time lag involve the works of the outstanding Taiwanese filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s: Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang.

Most of Hou’s films had no proper US release. When they were available for booking, as from Wendy Lidell’s heroic International Film Circuit, they circulated for one-off screenings. Some of his major films, such as City of Sadness (1989), still remain difficult to see. Edward Yang’s work was similarly obscure. When we ran a retrospective at our UW Cinematheque in 1998, we had to borrow prints from his family.

Most of Hou’s films had no proper US release. When they were available for booking, as from Wendy Lidell’s heroic International Film Circuit, they circulated for one-off screenings. Some of his major films, such as City of Sadness (1989), still remain difficult to see. Edward Yang’s work was similarly obscure. When we ran a retrospective at our UW Cinematheque in 1998, we had to borrow prints from his family.

Both of these extraordinary filmmakers had to wait many years for the exposure that is standard for European arthouse releases. After six features in seventeen years, Yang found a Western audience with Yi Yi (2000). Hou took even longer; twenty-seven years after his first feature, he gained some recognition with The Flight of the Red Balloon (2007) and last year, The Assassin. Meanwhile, many of these directors’ early films remain largely unknown, prey to ancient distribution contracts and the belief that the films would cost too much to revive and market.

Today’s entry and the next one celebrate the welcome news that important works by these two filmmakers are at last available on the disc format. Today I’ll concentrate on the three early Hou films from the Cinematek of Belgium: Cute Girl (1980), The Green, Green Grass of Home (1982), and The Boys from Fengkei (1983). Next time, I’ll consider Criterion’s release of Edward Yang’s masterpiece A Brighter Summer Day (1992).

Hou, early and late

Hou’s films are no stranger to this site. Among the first things I posted, back in 2005, was one of a batch of supplemental essays to my book, Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging (2005). That book devoted a chapter to Hou’s staging principles, with background on what I took to be the evolution of his technique. It was, I think, the first sustained view of Hou’s style, and it included discussion of his earliest films. These were scarcely known in the West and not considered in relation to his more famous work.

The online essay expanded my treatment of those titles. Because that essay is more or less buried elsewhere on the site, and it’s somewhat clunkily laid out by today’s standards, I’m reprinting it, with revisions, here, along with some bits from Figures. But first some background on these early works.

Hou began in the commercial, mainstream Taiwanese-language industry. Most local films had a strong genre identity: martial-arts movies, romantic comedies, or melodramas of family crises. Hou’s first directorial effort, Cute Girl, centered on a romance between two city dwellers who re-meet when the man is called to a surveying task in the countryside. Cheerful Wind (1981) reunites the two stars, Kenny Bee and Feng Fei-fe, in a more serious story of how he, a blind man, wins her love. In the pastorale The Green, Green Grass of Home, Kenny plays a schoolteacher brought to a village, where he meets another teacher and a romance blossoms. This film, however, expands to include dramas, big and small, involving several families; it also incorporates an ecological theme by encourage safe fishing policies.

In making these early films Hou discovered techniques that not only suited the stories he had to tell but also suggested more unusual possibilities of staging. He pushed those techniques further in his later films, with powerful results. The charming early films show him developing, in almost casual ways, techniques of staging and shooting that will become his artistic hallmarks. One basis of his approach, I argue, is his adoption of the telephoto lens.

How long is your lens?

Around the world, from the late 1930s through the 1960s, many films relied on wide-angle lenses—those short focal-length lenses that allowed filmmakers to stage action in vivid depth. One figure or object might be quite close to the camera, while another could be placed much further in the recesses of the shot. The wide-angle lens allowed filmmakers to keep several planes in more or less sharp focus throughout, and this led to compact, sharply diagonal compositions, as in Welles’ Chimes at Midnight (1966).

Although Citizen Kane (1941) probably drew the most attention to this technique, it was occasionally used in several 1920s and 1930s films made throughout the world. The great French critic André Bazin was the most eloquent analyst of the wide-angle aesthetic, and his discussion of Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), The Little Foxes (1941), and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) has strongly shaped our understanding of this technique.

The 1960s saw the development of an alternative approach, what we might call the telephoto aesthetic. Improvements in long focal-length lenses, encouraged by the growing use of location shooting, led to a very different sort of imagery. Instead of exaggerating the distances between foreground and background, long lenses tend to reduce them, making figures quite far apart seem close in size.

In shooting a baseball game for television, the telephoto lens positioned behind the catcher presents catcher, batter, and pitcher as oddly close to one another. Planes seem to be stacked or pushed together in a way that seems to make the space “flatter,” the objects and figures more like cardboard cutouts. The style was popularized by films like A Man and a Woman (1966).

The telephoto look quickly spread, employed by directors as diverse as Sam Peckinpah and Robert Altman, whose 1970s films also use the long lens, controlled by zooming, to squeeze a crowd of characters (M*A*S*H, 1972; Nashville, 1975) into the fresco of the anamorphic frame.

Hou Hsiao‑hsien came to filmmaking via the romance films so common in Taiwan in the 1970s, and this genre employed the long lens extensively. Working with low budgets, most filmmakers relied on location shooting. The telephoto allowed the camera to be set far off and to cover characters in conversation for fairly lengthy shots (as in Diary of Didi, 1978, below). In this respect, the directors were not so far from their Hollywood contemporaries; Love Story (1970) employs these techniques on a bigger budget.

Indeed, Love Story (a big hit in Taiwan) may have pushed local filmmakers toward using this technique in their own romantic melodramas; sometime the influence seems quite direct (Love Story and Love Love Love, 1974)

With these norms in place, Hou’s inclination toward location shooting and the use of nonactors, along with his attention to the concrete details of everyday life, allowed him to see the power of a technique that put character and context, action and milieu, on the same plane. His crowded compositions are organized with great finesse in order to highlight, successively, small aspects of behavior or setting, and these enrich the unfolding story, as Figures tries to show in his masterpieces of the 1980s and 1990s. Using a long lens (usually 75mm–150mm) he began to exploit some “just-noticeable differences” that the lens creates as byproducts.

Hou saw unusual pictorial and dramatic possibilities of the telephoto lens, and they became central to his distinctive way of handling scenes. A current norm of production practice yielded artistic prospects which he could explore in nuanced ways. Figures provides the detailed argument, but let me highlight three points here.

Exploiting the flaws

Flowers of Shanghai (1998).

One byproduct of the long lens is a shallow focus, as we can see in the examples above. Because the lens has little depth of field, one step forward or backward can carry a character out of focus. Hou stages in depth–and at a distance–but allows the layers to slip out of focus gradually.

Savoring the effects of gently graded focus is a common feature of Hou’s later work. The masher at the train station in Dust in the Wind (1987) moves eerily in and out of focus in the distance. In Daughter of the Nile (1988), there’s an astonishing shot showing gangsters approaching a victim’s SUV outside a nightclub: at first they’re only barely discernible blobs (seen through the vehicle’s narrow windows) but then they gradually come into ominously sharp focus in the foreground, preparing to attack one of the boys inside. The slight changes of focus train us to watch tiny compositional elements for what they may contribute to the drama. More recent examples abound in Flowers of Shanghai (1998), above, where it’s the foreground planes that dissolve.

Hou’s three first films don’t use the option quite so daringly; here the degrees of focus concentrate on the principal players but still allow us to register the teeming life around them (Cute Girl; Green, Green Grass).

Hou can put sharply different dramatic situations on different layers. In Green, Green Grass, the departure of the little girl, saying farewell to her host family, plays out slightly closer to the camera than the departure of the eccentric teacher.

This principle operates as well in the creatively distracting street and train-platform scenes of Café Lumière (2004).

Secondly, the long lens yields a flatter-looking space. It has depth, but the cues for depth that it employs are things like focus, placement in the picture format (higher tends to be further away), and what psychologists call “familiar size”—our knowledge that, say, children are smaller than adults, even if the image makes them both of equal size. One favorite Hou image schema is the characters stretched in rows perpendicular to the camera, and the telephoto lens, by compressing space, creates this “clothesline” look more vividly. We can find the clothesline staging schema in the early Hou films (Cute Girl, Cheerful Wind).

Another favorite schema is the “stacking” of several faces lined up along a diagonal (Cute Girl). This can be seen as a refinement of a schema that was in wider use, as an example from Love Story indicates.

But Hou uses this sort of image more subtly. The telephoto lens lets him stack faces in ways that encourage us to catch a cascade of slight differences (Millennium Mambo (2000)). In many scenes of Flowers of Shanghai (1998) this principle is carried to a degree of exquisite refinement without parallel in any other cinema I know. In one shot, the faces are stacked in the distance, behind a lantern, and a slightly shifting camera reveals slivers of them.

In general, because Hou is committed to a great density of information in the shot, the compression yielded by the long lens tends to equalize everything we see. Minor characters, or just passing strangers, become slightly more prominent, while details of environment can get pushed forward as well. The zoo scenes of Cute Girl enjoy showing us our characters in relation to the creatures around them.

In the shot surmounting today’s entry, the tile rooftops of The Green, Green Grass of Home, secured by bricks and pails and tires and baskets, become just as important as the figures below them.

In Green, Green Grass, Hou develops the equalized-environment option in one particular scene. A long-lens distant view catches the teacher coming to the father’s house along a corridor of rooftops.

When the teacher confronts the father, instead of tight framings on each man, Hou cuts to another angle that activates yet another range of environmental elements—principally the train passing in the background, prefiguring the trip that the man’s son and daughter will take in an effort to find their mother.

Because the long lens has a very narrow angle of view (the opposite of a “wide-angle” lens), it affects the image in a third major way. If you use a long lens in a space containing several moving figures, people passing in the foreground will block the main figures: they pass between the camera and the lens. Hou elevates this blocking-and-revealing tendency to a level of high art.

In Figures Traced in Light, I argue that many great directors, from the silent era forward, have staged action in the shot so as to block and reveal key pieces of information, calling items to our attention at just the right moment with unobtrusive changes of figure position. The possibility of blocking and revealing arises from the “optical pyramid” created by any camera lens. (Lots more on that pyramid in Figures and in this video lecture.)

Hou showed himself capable of using the blocking-and-revealing tactic in traditional ways. Take this simple encounter in Green, Green Grass, when the new teacher Da-nian meets Su-yun, the young teacher with whom he’ll fall in love. The scene begins on him, then cuts to a reverse angle as he’s introduced to the principal.

The others are turned toward the principal in the background; the whole composition pushes our eye toward him. Then the teacher steps left to judiciously block the principal. The woman on the far left turns her head and we’re nudged to look at her. Da-nian swivels slightly too.

Then the key introduction: Da-nian shifts aside a little, the teacher continues to block the principal, and the central woman turns toward us.

The climax (quiet, nifty) of this shot comes when Su-yun rises to meet Da-nian. She commands the center of the frame, frontal and radiant. Like any good classical director, Hou then gives us a reaction shot mirroring the first shot of this “simple” sequence: Da-nian is more than happy to meet her.

Imagine how a contemporary Hollywood director would handle this–lots of cuts, everybody in singles and close-ups, transfixing track-in to Su-yun, maybe a boingo music track–and count yourself lucky to have encountered, for once, an unfussy craftsman.

Hide and seek

The Green, Green Grass introduction scene involves a wide-angle lens, but Hou’s skill with slight character movement shows up in long-lens images too. In fact, I suspect that using the telephoto lens on location made him sensitive to the resources of masking and unmasking bits of the shot.

The loveliest example I know in the early films is the Cute Girl shot I analyze in Figures, when Fei‑Fei confronts the surveyors and the man in the red shirt serves as a pivot for our attention; the staging shifts our eye back and forth across the frame, according to small changes of character glance.

A less drastic example occurs when the surveying team starts quarrelling with the locals around a walled gate: The team’s blocking of the gate gives way to movement into depth and a struggle there between them and the townsfolk.

In all, it seems to me that these three resources of the long lens—the shallow focus, the compressed space, and the narrow angle of view—supplied artistic premises for Hou’s shooting and staging in the later films. This is not to ignore his use of the wide-angle lens on occasion, particularly interiors, as in the schoolteachers’ introduction scene. Once the lessons of the long lens had been absorbed, Hou could apply the staging principles that he’d developed to other kinds of shots and story situations. Sometimes he kept his style smooth and limpid, but at other times he offered the viewer some unusual challenges.

Peekaboo pictures

The Boys from Fengkuei (1983).

Presumably Hou could have kept making good-natured, crowd-pleasing movies for many years, but changes in his professional milieu gave him new opportunities. In the early 1980s Taiwan film attendance declined sharply, and Hong Kong films began to command more attention than the local product. The rash of independent companies had concentrated on speculation, not long-term investment, so only the government’s Central Motion Picture Company could initiate recovery. Ambitious government officials launched a “newcomer” program that offered support for cheap films by fresh talents. Even if the new films could not win back the local audience, they might gain renown at foreign film festivals. At the same period, a local film culture began to emerge, relying upon critics who were sympathetic to the creation of a New Taiwanese Cinema.

Hou was no newcomer, but working within the New Cinema framework he could reconceive his practice. The key question for all directors, he recalls, was: What is it to be Taiwanese? His New Cinema films would focus on political and cultural identity, and they did it through an approach to cinematic storytelling that in many respects ran against the conventions of his earlier films. His first New Cinema feature, The Boys from Fengkuei (1983; included in the Cinematek set) reminds us of how “young cinemas” have often represented a return to Neorealism.

Instead of introducing us to clear-cut protagonists and a dramatic situation, the film immerses us in a milieu, that of the small town of Fengkuei. The first fifteen minutes are episodic, casually showing a gang of teenage boys playing pool, lounging about, playing pranks, and above all getting in fights. Initially, the one who’ll become the main figure is minimally characterized; the emphasis, as the title indicates, is really on the group. The boys drift to the big city, where they try to get by and meet others their age. Throughout, local color and everyday routines drive the action more than character goals and traditional drama do.

This somewhat diffuse approach to narrative, in various countries, has proven well-suited for filmmakers who want to explore psychological development and social-cultural commentary. So it accords with the impulse toward understanding national identities that animated New Taiwanese Cinema. In addition, I think that this looser conception of storytelling allowed Hou to refine some of the stylistic options he had already explored. Now the extended, fixed telephoto shot with varying planes of focus appears as a more indeterminate pictorial field, as in our rather oblique introduction to the boys–partial framed figures drifting in and out of the frame–and their poolroom hangout. Emphasizing incomplete views and vague figures outside the door, Hou gives us a more precise array of balls on the table than he does of his characters in space.

Likewise, even though Hou has surrendered his very wide anamorphic frame, he finds ways to balance human action and tangible surroundings in the ways he did with city landscapes and village rooftops in the earlier films. The bullying of a motorcyclist and a pursuit by a rival gang aren’t rendered with the aggressive cuts and angles we’d expect in violent scenes in the Hong Kong action pictures then ruling Taiwanese screens. It’s as if Hou, along with his colleagues, is rejecting that other Chinese-language tradition.

Which is to say that when conflict comes, Hou turns to “dedramatization,” that tendency (again related to Italian Neorealism and its successors) of tamping down peaks of action. Now his characteristic long lens creates detached shots, sometimes with planimetric flatness, sometimes with tunnel vision. These images play out chases and fights in a way that minimizes their physical impact but reminds us of the design and details of the characters’ world.

Hou’s insistence on the fixed, distant telephoto take is now put in the service of obscured vision. The people who passed through the frame in the earlier films, blocking and revealing the action judiciously, may become more salient than the action itself–which is itself often offscreen, or swathed in shadow, or shielded by aspects of setting. The early films’ fixed long take enabled us to see story action fully, but, now, in its refusal to cut away, the camera can suppress story information.

Early in the film, a street fight passes in and out of a far-off intersection among stalls. The dust-up stirs only slight interest from passersby, before bursting back into the alleyway and coming to the camera.

The masking of the fight by the setting can be seen as an extension of the way the walls in the Cute Girl surveying quarrel intermittently cut off our vision, but here it’s far more drastic and sustained.

I’ve drawn my examples from the early stretches of The Boys from Fengkuei, so as not to preempt your own discoveries as the plot carries the gang to the big city. In these scenes Hou in effect teaches us how to watch his movie. But I think I’ve said enough to suggest how Hou’s fresh conception of narrative, born of a renewed interest in local culture (already present in another register in the first three films), allowed him to carry his stylistic explorations to new levels.

Hou saw certain pictorial possibilities in the long lens, and after developing them to a certain point in popular musicals, he recast them when he took up another kind of storytelling. He realized that leisurely, contemplative narratives permitted him to refine these visual possibilities, and they could become powerful, nuanced stylistic devices. And he didn’t stop, as the films following his New Cinema works vividly show. His visual imagination seems unlimited.

A more general lesson follows from this. Norms of form and style are resources for artists. Some artists follow the schemas that they inherit, while others probe them for fresh possibilities. A few can even make a handful of schemas the basis of a rich, comprehensive style. Ozu did this with the techniques of classical Hollywood editing; Mizoguchi did it with depth staging in the long shot. Like these other Asian masters, Hou reveals how much nuance a few techniques can yield, even when deployed in crowd-pleasing, mass-market movies. And now, thanks to the vagaries of film culture, more viewers can come to appreciate his achievement.

The frames from Diary of Didi and Love, Love, Love are, alas, cropped video versions, but that condition doesn’t keep us from recognizing the telephoto lensing in the originals.

The Cinematek collection also includes sensitive English-language introductions to the films by Tom Paulus and enlightening audiovideo essays by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin.

The indispensable English-language sources on Hou are James Udden’s in-depth career survey, Richard Suchenski’s monumental anthology, Emilie Yeh and Darryl Davis’ study of New Taiwanese Cinema, and two monographs on City of Sadness, one by Bérénice Reynaud, the other by Abe Markus Nornes and Emilie Yeh.

The fullest account I’ve offered of Hou’s style are in Figures Traced in Light and in a video lecture, “Hou Hsiao-hsien: Constraints, traditions, and trends.” See also the several blog entries touching on his work. A broader account of the historical tradition to which he belongs can be found in both Figures and On the History of Film Style, as well as in entries under Tableau staging and in the video lecture mentioned already.

The Boys from Fengkuei.

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Retrospectating

Keep Rolling (2020).

DB here:

Several of the films I’ve seen this go-round are either revived versions of older films, or recent films indebted to older traditions. Herewith, some thoughts on them.

Tender and tawdry

La Belle de nuit (1934).

I felt less dopey about not knowing about Louis Valray when Serge Bromberg, in an interview on the WFF site with Kelley Conway, confessed he’d not heard of him until he found an incomplete print of Escale (1935) by accident. Bromberg went on to find more footage, discover Valray’s first film, and secure the rights to restore and distribute them. Splendid in their restored versions (with curved corners on the frame), the films are at once generic and pleasingly perverse.

La Belle de nuit (1934) is a boulevard melodrama with hints of Vertigo and Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne. When a playwright discovers his wife has cheated on him with his best friend, he plots vengeance. By chance (i.e., dramaturgy) he finds a prostitute who is almost a dead ringer for the wife. He dresses her up, installs her in an apartment, and coaxes her to adopt a remote, mildly mocking manner. Of course, the treacherous best friend is in a frenzy to possess her. Wait till he learns about the past of his new passion.

La Belle de nuit alternates rather flat scenes of bourgeois flirtation with bursts of cinematic energy. Like other early sound films, there are some sharp auditory transitions. Dynamic hooks link scenes with sounds, images, or both: automobile wheels, locomotives, phonograph records.. There are peculiar angles and, most noticeably, a fascination with the unattainable woman. As ever, cigarette smoke helps the mystique.

I suspect that Valray learned a lot from making this first film because I found Escale a more polished production. Like his debut, it centers on a fallen woman who hangs around hazy cafes where hard-used women stroll among tables and sing about the troubles of life. Jean, an uptight lieutenant on passenger ships, falls in love with Eva, who hangs around smugglers in her seaport town. Jean and Eva share an idyll, and she seems redeemed. But when Jean leaves on a voyage, Eva’s loyal manservant Zama can’t keep her from succumbing to the mesmeric bootlegger Dario.

Escale has more exquisite visuals than La Belle de nuit. Filmed on a lush Mediterranean island, it bathes its landscapes and sea vistas and seedy port with a languid melancholy akin to that of Pépé le Moko (1937). Practically every shot, on land or sea or in the alleys or the boudoir, yields brooding, hypnotic imagery.

I find Escale‘s villain far scarier than the fussbudget playwright of La Belle de nuit. Dario wears more mascara than Eva, but the effect is to give him the burning glance of the true monster.

Both films, available on French DVD, would be a fine double feature for an enterprising US disc publisher or streaming service. Thanks to Bromberg and Lobster Films, they can be seen in their full glory.

A Taiwanese revelation

Just as the Valray films cast a new light on 1930s French cinema, so The End of the Track (1970) puts the standard history of Taiwanese cinema into a fresh perspective. The story is that the New Taiwanese Cinema of the 1980s, developed by Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and others, created a fresh turn toward social realism and more adventurous storytelling. Their tales of rural life and urban anomie clashed with the entertainment genres of commercial cinema and the government-sponsored films asserting that under Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang regime life was buoyant and carefree. With The End of the Track we have a fine predecessor, a “parallel” film that dared formal and thematic opposition to the mainstream, and did so well before the New Wave directors.

Yung-shen’s father and mother run a noodle cart; Hsiao-tung’s family is well-off. But the boys are fast friends. They enjoy long days in their rural paradise–swimming naked, play-fighting, and exploring caves. The film’s first twenty-five minutes are almost plotless, built out of routines of school, play, and homework. But then a crisis strikes, and the film turns achingly sad in a quiet, unmelodramatic way. The plot shifts slowly to a study of how one boy becomes a surrogate son for a grieving family, while his own parents respond uncomprehendingly.

The boys’ skinny-dipping and mud wrestling earned the film a ban for “homosexual undertones and ideology.” There’s surely a homosocial, and maybe homoerotic undercurrent, but the main impression is that of devoted friendship and the heavy weight of obligation. One boy must leave childhood behind, too soon, and start a new life. Just as powerful is the class component. In one grueling sequence, Yung-shen’s parents try to push their cart through typhoon-swept streets as Hsiao-tung’s parents look on from their car.

Pictorially, director Mou Tun-fei makes full use of the glorious scenery that rural Taiwan can yield. He uses fast cutting, handheld shots, abrupt flashbacks, and other “modern cinema” techniques. These techniques can be seen in many commercial Taiwanese films of the period, but most directors used them to jazz up generic plots. Here, the fastidious black-and-white palette gives them a certain sobriety. The gravity is enhanced by severe but lyrical compositions, like this planimetric shot of the boys laying out a running track.

Above all, the slow pace of the film–the basic story is almost an anecdote–allows Mou to soak us in the characters’ milieu. There are even some prolonged, static long shots that look ahead to the precisely unfolding scenes we get in Hou’s films and in Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991).

Mou is now, like Valray, a rediscovered director enjoying belated fame in his national cinema. In a very helpful discussion of his career, Wafa Ghermani and Victor Fan point out that there was at the period an important trend toward independent, low-budget films in Taiwanese (rather than the official language of Mandarin), and Mou’s work is just one example. As usual, a festival screening can remind us that there’s a lot more powerful cinema out there than we’ve realized.

Her time has come

Keep Rolling (2020) isn’t an old film, but it’s about a director who has over forty years quietly carved her own niche in world cinema.

In the 1980s, a new generation of filmmakers overturned Hong Kong cinema. Some, like Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, and John Woo, brought a turbocharged version of the New Hollywood to a film culture already energized by a tradition of martial-arts action. Other young talents formed what came to be called the Hong Kong New Wave. Although Tsui was sometimes identified with this, this trend was not so brash. It moved toward social realism, with directors like Allen Fong and Stanley Kwan exploring a modernizing Chinese culture living under colonial rule but forging its own identity.

Of all the New Wave directors, Ann Hui distinguished herself by her sincere and dogged attention to Hong Kong life as it is lived. After making some docudramas for television, she directed her first feature, The Secret (1979) and won festival attention with Boat People (1982) and Song of the Exile (1990). Although she has happily embraced genre films–she has made ghost stories and thrillers–she always treats sensational material with a calm, unspectacular attention to characterization and mood. Her swordplay film, the two part Romance of Book and Sword (1987), emphasizes landscape and interpersonal drama over action set-pieces. Who else would make Ah Kam (1996), a martial-arts movie centering on a stuntwoman?? She brought attention to social problems, sometimes in advance of social policies: caring for a parent suffering from dementia (Summer Snow, 1995), the need to shelter victims of marital abuse (Night and Fog, 2009), and lesbian rights in Hong Kong (All About Love, 2010).

In all, she has directed twenty-eight features. Every one has been a struggle.

Because the local market has been small, Hong Kong filmmakers have had to look abroad. For directors like Tsui and Woo, that meant making flamboyant action vehicles for audiences across East Asia, as well as for the Chinese diaspora and fans in other territories. But Ann Hui’s commitment to local life meant that her films had to gain wider attention on the red-carpet circuit. They did. Over the decades, they routinely played the major festivals. Her A Simple Life (2011) got a standing ovation when it played Ebertfest in 2014; Roger called it one of the year’s best films.

Last year Kristin and I were sorry we couldn’t be in Venice to watch her accept a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. In response to my email of congratulation, she was characteristically modest in facing a 14-day quarantine when she returned home. As ever, she makes personal contact:

Tonight I am dead beat n have a whole day of press tomorrow before I leave on the day after. I promise myself I’ll only stick to filmmaking from now onwards. How r u and is the pandemic bad in your area? HK is bad all the way you must know. Will u still come n visit us? Take care n keep well! Ann

Ann’s career receives a fitting tribute in Man Lim-chung’s Keep Rolling. It surveys her life, with fine interviews with her sister and brother, along with comments from friends and critics. There’s a lot of behind-the-scenes production footage. Above all, Man offers a personal portrait of her persistence and dedication. Virtually the only female director to make a career in Hong Kong, she has contributed to the world’s humanist cinema shaped by directors like Kurosawa, Kiarostami, and Satayajit Ray. Stubbornly sincere, with no PoMo flash or trickery, her small-scale studies of character always have wider social resonance. One can only hope that this film brings her–and her films, shamefully neglected on DVD–to more audiences.

The four films reviewed above are all available from the Festival across the USA until midnight Thursday. You can sign up here.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

For more on Ann Hui’s visit to Ebertfest, go here. We’ve reviewed many of Ann’s films on this site; check the category. I discuss trends in Hong Kong cinema in Planet Hong Kong and consider some aspects of Taiwanese film in Chapter 5, on Hou, in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. I sure wish I had known The End of the Track when I wrote that chapter.

The End of the Track (1970).

Madalena, Rosalind, and Suzanna: More Rotterdam revelations

Madalena (2021).

DB here:

A mixure of moods and tones for our final communiqué from the International Film Festival Rotterdam. Its fiftieth year has been a lively one.

The Madalena mystery

Madalena (2021).

In earlier entries (especially here) I’ve noted that the thriller genre is well-adapted to festival circulation. It doesn’t require the budget of a blockbuster. It can attract major actors who want tricky parts to play. It can be shot on contemporary locations. And the appeal to suspense and surprise fits comfortably with edgy narrative strategies favored by art cinema. At the limit, a filmmaker can arouse our thriller appetites and then try a bait-and-switch that not only warps the genre’s conventions but sets us thinking.

The Brazilian film Madalena, by Madiano Marcheti, starts as a classic mystery. In a vast field of soy, reas stalk gracefully as a monstrous pesticide-sprayer grinds toward them. But among the rows lies a corpse.

What follows is more fractured and prismatic. A first section attaches us to Luci, a friend of Madalena’s who works as manager of a club. She also picks up work dancing for TV commercials, one set in that very acreage. Then we follow Cristiano, whose father owns the land and demands he hustle to harvest. A third section takes us with trans woman Bianca and her girlfriends, who sort through Madalena’s belongings before setting out for a day of driving, swimming, gossiping, and teasing one another, the memory of Madalena never far from their thoughts.

Marcheti skips some of the standard scenes. We never see the police investigation, or even the discovery of the body. The crime plot has been a pretext to reveal a cross-section of life in the community, from the wealthy farmers to the cottages where the staff live. The resolution shifts the question of who did it to the broader impact of the death, and how it stands for a horrifying statistic: Brazil has the world’s biggest murder rate of transgendered people.

Throughout, sexualization of bodies is a central motif. Luci and her posse hang out at curbside, Bianca and her posse turn tricks and find boyfriends, and Cristiano, after sizing up the crowd at Luci’s bar, winds up dancing with himself in mirror reflection.

To say much more would spoil things, so I’ll just note that this story is filmed with a pictorial intelligence that one seldom sees these days. The imagery of the soy fields is at once magnificent and ominous. Drones hover over it like birds of prey, and its horizon haunts the people’s lives.

Overwhelming as the landscape is, it doesn’t blot out the characters’ routines and the crises that disrupt them. Moving from Luci’s aimless days and nights to Cristiano’s panic to Nadia’s quiet tribute to Madalena, a locket set adrift in the stream that runs along the field, the film pauses for intimate moments. It reminded me a bit of Varda’s great Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi), in which an enigmatic figure’s fate charts the range of human indifference, but also affords glimpses of sympathy.

An informative discussion of the film with Marcheti is provided by IFFR here.

As we too like it

As We Like It (2021).

This movie saw me coming a mile away. It does for As You Like It what Lurhmann did for Romeo and Juliet, but to an Asia-pop beat. Four romantic couples lose and rediscover one another in a magical milieu–not the Forest of Arden (currently under corporate development) but a district of Taipei with no Web connections. In Heaven, a sign informs us, there is no Internet.

Accordingly, people must deliver messages in person, seek out each other by dint of shoe leather and motorbikes, and actually meet face to face. So Rosalind’s quest to find her father the Duke (a genial tycoon) intertwines with Orlando’s search for her. But of course she’s disguised as a boy and aided by Celia, a fortune-teller who’s the dream girl of Orlando’s sidekick Dope.

The film’s world is maximum kawai, pushing beyond camp to a fangirl fantasy of irresponsible sweetness. This candy-colored city, with its pink blimps and anime posters, spills over with tweens, teens, and twentysomethings shopping in malls, flirting at stalls, and sipping bubble tea.

In the process, old stuff becomes cool. Tradition, in the form of calligraphy and handmade paper, is a retro decorator choice, while letting your date clean your ears old-style makes him a friend with benefits.

It might all seem sappy, but like Tati’s Play Time and Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, the film seeks to distill authentic poignancy out of kitsch, schlock, consumer clichés, lethal cuteness, and the detritus of urban lives. Frivolity must be good for something; why else would God give us giggles? Comic form, as Shakespeare acknowledged, redeems a lot of silliness, especially if the gags are hurled at us with the ruthless conviction that anything goes.

Did I mention that all the roles are played by female performers?

In a switcheroo on Elizabethan theatre, globalization inverts the Globe. The film, a final title tells us, is dedicated to Shakespeare “but also to the patriarchy who would not allow female actors upon the stage.” The frisson is akin to that of Tsui Hark’s Peking Opera Blues and The East Is Red, where gender-blurring yields both humor and genuine feeling. From instant to instant, you see a character go male or female or something in between; a painted-on mustache and a swaggering gait become cosplay, not deep definitions of you. Unless you want it to be.

Identities are fluid. Okay, says Orlando, so he falls in love with Rosalind, then Roosevelt, and refinds him/her as Rose. What’s in a name? You get to call yourself, and be, what you wish, and love whoever.

Not a fresh-minted message these days, but the sparkle comes with how it’s all carried off. Every scene finds a clever way to amuse or bemuse. When Rosalind as Roosevelt slips into a trim suit, she pads out the crotch with a towel, and teeny gull-like waves waft out. That’s soft power, the equivalent of a mystic ring. Eventually she has to go along when Orlando visits the men’s room. While he stands at the pissoir, she ducks into a toilet pretending to take a dump, her groans covering the sound of peeling open a maxi-pad.

The project was co-directed. Wei Ying-chuan, a graduate of NYU’s Educational Theatre division, is a founder of Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group in Taiwan. Chen Hung-yi’s feature The Last Painting was chosen for IFFR in 2017 and won a best feature award at Cines del Sur. The pair bring an unflagging energy to the task of creating a paradise of easy living and loving–bereft of villains, open to any piece of harmless fun and heartbreak. As We Like It is a must for every LBGTQ film event, but its hella dirty fun for any festival whatsoever. Couples welcome.

Again, the IFFR provides a fine discussion of the film with the directors, moderated by our old friend Shelly Kraicer.

St. Tropez, mon amour

Suzanna Andler (2020).

Eric Bentley once described great serious literature as “soap opera plus.” Anna Karenina, Othello, and the rest offer us tormented love affairs, sexual jealousy, hidden schemes, and forced confessions of betrayal, but it’s all endowed with wider significance through characterization, implication, style. But can we have soap opera minus?

In Daisy Kenyon, Anatomy of a Murder, and other films, Preminger moves in this direction, banking the fires of conflicts drawn from lurid bestsellers, but other filmmakers have gone further in de-dramatizing melodrama. Dreyer’s Gertrud and some of Oliveira’s adaptations offer examples. Here we have the classic fraught situations, but muffled and fragmented and punctured through long pauses and wayward, looping, maddeningly banal conversations.

Marguerite Duras made this artistic strategy peculiarly her own, notably in her masterpiece India Song (1974) and its counterpart Son nom de Venise en Calcutta désert (1976). In a curious reversal, she often prepared the film first and then published the text as a quasi-play, as if scraping away the luscious imagery and ripe sound would create something even purer, soap opera distilled to Racinian starkness.

Suzanna Andler, a Duras theatre piece from 1968, has now been adapted to film featuring Charlotte Gainsbourg and three other players. The result isn’t as severe as the play reads, since director Benoît Jacquot has filmed it in a gorgeous villa overlooking the Mediterranean. It remains, however, in the tradition of kammerspiel. The bulk of the action takes place in a salon and the terrace outside, with one sequence, also in the play, set on a rocky beach.

The situation is sheer bourgeois melodrama. Suzanna is in a loveless marriage with the philandering Jean. She has apparently stayed with him for the sake of their children and the wealthy life they lead. Now Michel, a young journalist, has tempted her into a love affair, and she has for the first time cheated on Jean–who seems okay with it. Today’s crisis, if this counts as one, is her need to decide: Will she lease this villa for the summer with the kids? Or will she accept Michel’s invitation to go to Cannes? In the course of about four hours, she may make up her mind.

If some of my synopsis seems hazy, it’s partly because the exposition comes out in bits as Suzanna and others chat about her past, and partly because what she says may not be wholly truthful. She sometimes admits to lying. And what was her relation to the never-seen Bernard Fontaine, who has just been killed in a car crash? The blurry backstory is one strategy Duras uses to tamp down the melodrama, which usually gives its plots clear-cut contours and definite revelations.

In filming the play, Jacquot has taken an approach that approximates the rigor of Duras’s aesthetic. He has shot the blocks of action using slightly different techniques. Not for him obvious alternatives like color/ black-and-white or a range of tonalities. The differences are made harder to spot because Jacquot has not given us separate chapters corresponding to the act divisions; the scenes blend, punctuated only by long shots. So there are stylistic spoilers coming up.

At the start, Suzanna is shown the house by the real estate agent de Rivière. This segment is filmed in distant shots that emphasize the landscape and straight-on views of the sitting room opening out onto the terrace and the sea. The agent is seen from behind or at a distance, while the few close views we get concentrate on Susanna.

Staying behind alone, she falls asleep and awakes when Michel enters. This is a second phase of the play’s first act, and now Jacquot’s camera setups take a more oblique view of the room. The full-length windows dominate again, but now at an angle that recalls the magic mirror of India Song (on which Jacquot was an assistant).

The couple is often seen at a distance, but now closer views of Suzanna emphasize the mirror motif.

At a high point, the camera celebrates a momentary reconciliation with a track in to their embrace (the first such florid move in the film, I think).

In the sequence corresponding to the second act, Suzanna meets her friend (and Jean’s ex-lover) Monique. On the beach they talk of their pasts. Now the conversation is rendered in many rapid, tight shots of the two women. The orthodox shot/ reverse shot setups are sometimes given a strange emphasis when instead of A/B alternation we get two (but only two) variants of a view of each one as she speaks (A1/A2, then B1/B2). So a cut like this::

. . . is followed by ones like these:

Back at the villa, Suzanna answers a phone call from Jean, and they discuss their plans, with the uncertainty typical of all the film’s conversations. This scene is handled in circular tracking shots around Suzanna, from a moderately close distance.

As the conversation ends, Michel returns. After he reveals some key information about his relation to Jean, he stretches out on the sofa. In a long take running several minutes, the camera swings around them in a half-circle, clockwise and counterclockwise, often adjusting to her shifts in position.

The changing angle also captures Suzanna perched against a painting of very 60s boomerang shapes that echo the camera’s trajectory.

As the action approaches what might be a climax, Michel drifts out to the terrace and sits on the balustrade above the sea. Suzanna approaches.

Telling you what happens next would truly be a spoiler. On seeing it, I thought it was something that Jacquot added to the play, but nope . . . it’s there in the text, and he’s perfectly faithful to it.

As if all this patterning doesn’t look finicky enough, the scene on the beach is punctuated by a single shot of the Quai de Passy with a Métro train rumbling by.

This bump comes exactly halfway through the film, at the moment Suzanna mentions the surge of attraction she felt when Michel looked at her on their first encounter. Believe it or not, the line in the play also comes midway through the text. This alien shot functions expressively, I think. It underscores the epiphany Susanna felt upon learning she might be loved. Another filmmaker might have stressed the moment with music under her monologue, but Jacquot goes for a formal bonus: breaking the visual texture just here further articulates the design of his film.

The rigorous geometry Jacquot has clamped down on the play is interesting in itself, and the abstract array of options adds, I think, to the hieratic quality Duras is after. Yet each style matches the tenor of the action it carries and doesn’t conceal the subdued feelings rippling through the scenes. This dimension depends on Gainsbourg–her slim silhouette, her microdress, and especially her face, with her alert chin and hard mouth. Her vacillations have nothing of the diva about them, but still she stands forth as a new avatar of The Confused Woman so beloved of art cinema (Voyage to Italy, L’Avventura, The Headless Woman). Without those closer shots, the film might fall flat.

Once asked what would be his ideal final shot, Jacquot replied: “A distinctive glance [un certain regard] in close-up.” His ending delivers that.

Duras is doing something similar to what Wei and Chen do in As We Like It. She is seeking genuine emotion in clichés (unfaithful husband, wrung-out wife, surly rescuer). But she hasn’t exempted her characters from social critique. Hiroshima, mon amour renders the meeting of two lovers as an intertwining of two national histories. The colonialists of India Song, drifting through their sparsely attended embassy parties, trying to replicate salon society in the tropics, cannot hear the voices offscreen of the people they subjugate. Likewise, Suzanna’s anxiety may or may not register some distant tremors. In summer of 1968 her world is sliding into something she isn’t prepared for. Far away from St. Tropez, in Paris students are hoping to find their own beach, but they’re doing it by tearing up the pavement.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to visit their event virtually. Here’s to another fifty years of ambitious programming!

A very helpful edition of Suzanna Andler has been published in conjunction with the film’s release. It contains a lot of stimulating background information and critical commentary. Bentley’s comment about “soap opera plus” comes from The Life of the Drama (Applause, 1991), 14. Thanks to Kelley Conway for sharing with me the Jacquot interview in “Réponses à tout,” Libération (14 May 2004), 1.

Jacqout’s rendition of Duras’s play exemplifies what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film “parametric narration.” This rare approach consists of playing out a range of expressive possibilities, scene by scene, in ways that both shape the ongoing plot and “anthologize” sharply contrasting cinematic techniques. Noël Burch first proposed this idea in his enduring Theory of Film Practice (1973), although Eisenstein and Bazin envisioned it. But then they envisioned everything.

P. S. later: The Rotterdam prize winners have been announced (per Variety).

As We Like It (2021).

Friendly books, books by friends

Moses and Aaron (1974).

DB here:

When the stack of books by friends threatens to topple off my filing cabinet, I know it’s time to flag them for you. I can’t claim to have read every word in them, but (a) we know the authors are trustworthy and scintillating; (b) what I’ve read, I like; (c) the subjects hold immense interest. Then there’s (d): Many are suitable seasonal gifts for the cinephiles in your life (which can include you).

Happy birthday, SMPTE

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

It includes survey articles on the history of film formats, cameras and lenses, recording and storage, workflows, displays, archiving, multichannel sound, and television and video. There’s even an overview of closed-captioning. The issue costs $125 for non-SMPTE members, and it’s worth it. Many libraries subscribe to the journal as well.

A highlight is John Belton’s magisterial “The Last 100 Years of Motion Imaging,” which includes twenty-two pages of dense timelines of innovations in film, TV, and video. They stretch back beyond 1916, to 1904 and the transmission of images by telegraph. John’s article is provocative, suggesting that we might think of digital cinema as returning to film’s origins in handmade images for optical toys.

Lucas predicted that digital postproduction brought film closer to painting, and for more and more filmmakers that prediction is coming true. I was startled to learn that 80% of Gone Girl was digitally enhanced after shooting.

Yes, sir, that’s our BB

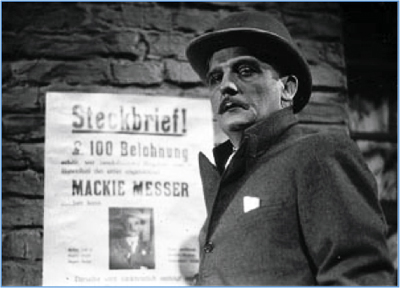

Die 3 Groschen-Oper (1931, G. W. Pabst).

During the 1970s, Bertolt Brecht’s name was everywhere in film studies. He epitomized what an alternative, oppositional, or subversive cinema ought to be. Cinema, even more powerfully than theatre, was a machine for producing illusions. So in his name critics objected to happy endings, plots that tidied up reality, characters with whom we ought to identify, messages that masked the real nature of bourgeois society. Films made all these things seem part of the natural order of things.

The Brechtian antidote was, as people used to say, to “remind people they were watching a film.” This was done by rejecting what he called the Aristotelian model and replacing it with the “alienation effect”: a panoply of distancing devices like intertitles, characters addressing the camera, actors confessing they were actors, and a display of the means of cinematic production (including shots of the camera shooting the scene).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

Brecht became part of Theory. In French literary and theatrical culture of the 1950s, his ideas on staging and performance had claimed the attention of Roland Barthes and other Parisian intellectuals. Godard was alert to the trend early, it seems; he had fun in Contempt (Le mépris, 1963) citing the two BB’s (the other was Brigitte Bardot, bébé), and letting Lang quote a poem by his old collaborator and antagonist. By the time Anglo-American film theorists were ready for semiotics, Brecht was offering support. Didn’t his anti-illusionism chime well with the belief that all sign systems were arbitrary and culturally relative?

My summary is too simple, but then so were many borrowings. Soon enough any highly artificial cinematic presentation might be called “Brechtian,” though usually minus the politics. In the academic realm, Murray Smith’s book Engaging Characters (1995) pointed out crucial weaknesses in the anti-illusionist, anti-empathy account. By then, the certified techniques were becoming part of mainstream cinema. Thereafter, we had Tarantino’s section titles and plenty of movies breaking the fourth wall. Brecht might have enjoyed the irony of using the to-camera confessions of The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) bent to support cynical swindling. Isn’t The Big Short (2015) a sort of Hollywoodized lehrstück (“learning play”)?

Brecht’s writings should be read and studied by every humanist and certainly everybody interested in film. They’re clear, blunt, and often sarcastic.

This beloved “human interest” of theirs, this How (usually dignified by the word “eternal,” like some indelible dye) applied to the Othellos (my wife belongs to me!), the Hamlets (better sleep on it!), the Macbeths (I’m destined for higher things!), etc.

Now Marc Silberman, our colleague here at Madison, has completed a trio of books that make the master’s work available. Bertolt Brecht on Film and Radio includes essays, scripts, and the Threepenny Opera lawsuit brief. There’s also Brecht on Performance and a complete revision of that trusty black-and-yellow volume dear to many grad students: Brecht on Theatre. The latter two collections Marc worked on with collaborators. All are indispensible to a cinephile’s education. As Brecht imagined a bold political version of music he called misuc; can we imagine a cenima?

From BB to S/H

Speaking of Straub and Huillet, every decade or so somebody comes out with a book about them. This time we have to thank the admirable Ted Fendt, in the twenty-sixth volume in the series sponsored by the Austrian Film Museum (as well as the Goethe Institute and Synema). Like the Hou Hsiao-hsien volume (reviewed here), Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet is fat and full of ideas and information.

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

Starting things off is a lively and comprehensive survey of the duo’s careers by Claudia Pummer, with welcome emphasis on production circumstances and directorial strategies. The book wraps with a detailed thirty-page filmography and a substantial bibliography.

My thoughts about S/H are tied up with their earliest work, when I first learned of them. So I loved, and still love, Not Reconciled (1965) and The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. I also have a fondness for Moses and Aaron, Class Relations (1983), From Today until Tomorrow (1996), and Sicilia! (1998). I find others out of my reach, and several others I haven’t yet seen. People I respect find all their work stimulating, so I suspect it’s really a matter of gaps in my taste.

Whether you like them or not, they’re of tremendous historical importance. Without them, Jim Jarmusch and Béla Tarr, and of course Pedro Costa and Lav Diaz, would not have accomplished what they have. And especially in December 2016, we ought to find their unyielding ferocity inspiring. Remember them on Dreyer: “Any society that would not let him make his Jesus film is not worth a frog’s fart.” Brecht would have approved.

Stone’d

To the minimalism of Straub and Huillet we can counterpoint the maximalism of Oliver Stone, the most aggressive tabloid American director since Samuel Fuller (although Rococo-period Tony Scott gives him some competition). After two books on Wes Anderson, Matt Zoller Seitz has brought us a booklike slab as impossible as the man’s films. Can you pick it up? Just barely. Can you read it? Well, probably not on your lap; better have a table nearby. Does its design mirror the maniacal scattershot energy of films like JFK (1991), Natural Born Killers (1994), and U-Turn (1997)? Watch the title propel itself off the cover.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The whole thing comes at you in a headlong rush. Amid the pictorial churn and several essays by other deft hands, we plunge into and out of that stellar interview, mixing biography and filmmaking nuts-and-bolts. Matt gets deep into technical matters, such as Stone’s penchant for rough-hewn editing, as well as raising some big ideas about myth and autobiography. There are occasional quarrels between interviewer and interviewee. Out of the blue we get remarks like “Alexander was not only bisexual, he was trisexual,” which was not redacted.

The book’s very excess helps make the case for Stone’s idiosyncratic vision. Matt’s connecting essays, along with the vast visual archive he’s scavenged and mashed up, made me want to rethink my attitude toward this overweening, sometimes crass, sometimes inspired filmmaker. He now seems a quintessential 80s-90s figure, as much a part of the era as Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Stone emerges as a resourceful defender of The Oliver Stone Experience, articulating a radical political critique with gonzo verve.

Rhapsody in white

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

This period piece is in its own way as wild as an Oliver Stone movie. From its opening cartoon of Paul himself as a Great White Hunter bagging a lion, it’s a virtually self-parodying account of how a black musical tradition got netted, trussed up, and caged for the swaying delectation of white audiences. (No need to mention the irony of the name of our King.)

Along the way we have some straight-up songs (including some by Bing Crosby) spread among extravagant dance numbers. The Universal crane gets a workout as well. The music is infectious, the performers sweating to please, and the restoration–coming, I hope, to your screen soon–finally shows what two-color Technicolor could do. This is the definitive version of a film too often known in cut versions with shabby visuals and sound.

The book is an in-depth contextualization of the film, the studio, and the tradition of musical revues, both on stage and in film. It records the production and reception, with rich documentation throughout. The story of assembling the restoration is there too, and it’s a saga in itself. David is one of the moving spirits behind the online Media History Digital Library and its gateway Lantern. James is Manager of the Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center at the Museum of Modern Art. Their collaboration has given us both a lush picture book and a serious, always enjoyable piece of scholarship. Their book proves the value of crowdsourcing: funded by online subscription, it was self-published. In this and much else, it can be a model for film historians pursuing questions that commercial and university presses might find too specialized. The result is a model of ambitious research, writing, and publishing.

Visiting Radio Ranch

Gene Autry in The Phantom Empire (1935).

For about thirty years I’ve been arguing that one fruitful research program in film studies involves what I call a poetics of cinema: the study of how, under particular historical conditions, films are made to achieve certain effects. This program coaxes the researcher to analyze form and style, study changing norms of production and reception, and consider how filmmakers work in their institutions and creative communities, with special focus on craft routines, work methods, and tacit theories about the ways to make a movie.

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

Scott traces production practices and conventions, focusing in particular on two dimensions. First, to a surprising degree, serials rely on the conventions of classic stage melodrama, such as coincidence and more or less gratuitous spectacle. Second, the serials are playful, even knowing. Like video games, they invite viewers to imagine preposterous narrative possibilities, not only in the imagination but also on the playground, where kids could mimic what they saw Flash Gordon or Gene Autry do.

Matinee Melodrama investigates the implications of these dimensions for narrative architecture, visual style, and the film and television of our day. Scott closes with analysis of the James Bond series, the self-conscious mimicking of serial conventions in the Indiana Jones blockbusters, and the Bourne saga, and he shows how they amp up the older conventions. “Like the contemporary action film generally, the Bourne movies participate in a cinematic practice vigorously constituted by studio-era serials. That is, they blend melodrama with forceful articulations of physical procedure in scenes of pursuit, entrapment and confrontation.”

Poetics, frank or stealthy

The Red Detachment of Women (1971).

Scott’s book acknowledges the poetics research program, and so, even more explicitly, does a new collection edited by Gary Bettinson and James Udden. The Poetics of Chinese Cinema gathers several essays that usefully test and stretch that frame of reference.

One standard challenge to the poetics approach is: How do you handle social, cultural, and political factors that impinge on film? I think the best way to answer this is to treat these factors as causal influences on a film’s production and reception. More specifically, in the production process, what we now call memes function as materials—subjects, themes, stereotypes, and common ideas circulating in the culture or the filmmaking institution. In the reception process, they provide conceptual structures that viewers can use in making their own sense of the films that they’re given. And such materials will necessarily include other art forms; films are constantly adapting and borrowing from literature, drama, and other media.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Both of these possibilities are vigorously explored in several essays in The Poetics of Chinese Cinema. For instance, Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh traces how Taiwanese and Japanese cultural materials are reworked by Hou Hsiao-hsien in his Ozu homage Café Lumière (2003). Peter Rist, a long-time student of Chinese painting, shows how Chen Kaige deploys cinematic means to revise landscape traditions to create a “Contemplative Modernism.” Victor Fan shows how the Hong Kong classic In the Face of Demolition (1960) adapts and revises a mode of narration already established in Cantonese theatre. In a clever piece called “Can Poetics Break Bricks?” Song Hwee Lim considers how digital technology feeds into a poetics of spectacle, specifically around slow-motion techniques that were emerging in pre-digital filmmaking.

Tradition is a key concept in poetics, and the editors explore important ones in their own contributions. Gary Bettinson studies the emergence of Hong Kong puzzle films in works like Mad Detective (2007) and Wu Xia (2011). Are they simple imitation of Hollywood, or are they doing something different? Gary shows them to have complicated ties to local traditions of storytelling. Jim Udden focuses more on stylistics in his account of Fei Mu’s 1948 classic Spring in a Small Town, remade by Tian Zhuangzhuang in 2002. By examining staging, cutting, and voice-over, Jim shows that the earlier film is in many ways more “modern” than it’s usually thought and is somewhat more experimental than the remake.

It might seem that the “model” operas and plays of the Cultural Revolution, epitomized in The Red Detachment of Women (1971) would resist an aesthetic analysis; they’re determined, top-down fashion, by strict canons of political messaging. But Chris Berry’s contribution shows that they’re amenable to close analysis too. Like Soviet Socialist Realism, they may be programmatic in meaning, but not in every choice about framing, performance, cutting, and music. Indeed, the fact that people both inside and outside China (me included) still find them pleasurable probably owes something to their “Red Poetics.” And in true Hong Kong fashion, many filmmakers in that territory plundered those soundtracks with shameless, drop-the-needle panache.

I should probably add that I have an essay in this collection too. It’s called “Five Lessons from Stealth Poetics,” and it surveys things I’ve learned from studying cinema of the “three Chinas”: Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. What attracted me were the films themselves, but in exploring them I was obliged to nuance and stretch the poetics approach. Readers of this blog know the trick: in talking about particular movies, I also try to show the virtues of the approach I favor. In other words, stealth poetics.

This is a good moment to pay tribute to Alexander Horwath, moving into his final nine or so months of directing the Austrian Film Museum. He has been a major figure in European film culture, through his inspired programming and leadership in publishing the books and DVDs issued by the Museum. We’re very grateful for all he has done for us and for film historians around the world.

P.S. 11 December 2016: Thanks to Mike Grost for a title correction and John Belton for a name correction!

King of Jazz (1930).