Archive for September 2018

On the Criterion Channel: Five reasons why HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR still matters

Often this scandalous or honorable story, this beautiful or ugly one, will be told you the next day or the next month, sometimes in fragments. There is nothing that is of a piece in this world, everything is a mosaic.

Balzac, Une fille d’Ève

DB here:

We’re not big fans of listicles. Our only effort in this direction is our annual review of the 10 best movies of 90 years ago. But now we have my Criterion Channel installment devoted to Hiroshima mon amour. (There’s a sample here.) The installment is focused on the film’s use of editing. That topic does allow me to touch on wider matters of storytelling and theme, but I found myself struggling to squeeze in all I wanted to say. So. . . .

If you haven’t seen the film, both this and the Criterion Channel segment will teem with spoilers. Now I’ll give a plot synopsis, but the shocks in the film’s early stretches are probably softened if you know the story’s premises. So if you haven’t seen the film yet, you’re advised to stop reading now.

Hiroshima mon amour, the 1959 feature film directed by documentarist Alain Resnais, tells the story of a brief sexual affair between an unnamed man and woman. She has come to Hiroshima to make a film about the effects of the US nuclear bombing of the city in 1945. Her plane is scheduled to leave the following day, but he asks her to stay longer in Japan. As a result, what drama there is becomes psychological—pressured by her deadline, but complicated by her memories.

After their first night of lovemaking, she tries to break with him, but in the course of the day he pursues her and they meet at intervals. They go to his house for another bout of lovemaking, to a bar called the Tea Room, to the train station, and back to her hotel, where the film began. In the course of their affair, she recalls and recounts her wartime romance with a German soldier stationed in her city of Nevers. At the liberation, he was shot by a sniper. The townsfolk punished her by cropping her hair and confining her in a cellar.

In a gesture characteristic of ambitious cinema of the period, we don’t definitely learn that the woman decides to leave. The final scene, suggesting that she will always think of the man as Hiroshima, does imply that they’re parting. More important, in the course of their affair she has realized that her memories of her first love are fading, and she fears that makes her deeply disloyal to him. Worse, she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

Hiroshima is one of the most important films ever made, summing up many tendencies of modern cinema but also indicating new directions for later filmmakers. Its implications and possibilities radiate out in several directions, like the spidery silhouette (in negative?) under the opening credits. So a listicle format seems, for once, justified.

(1) The opening

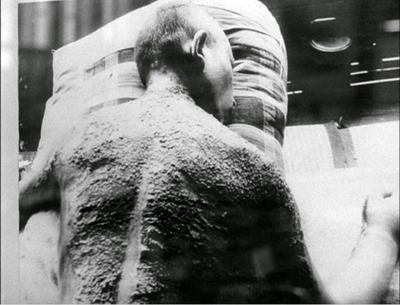

Two bodies, from the waist up, are locked in an embrace. The faces aren’t visible. At first, the bodies are powdered with dust but as the images dissolve into one another, the limbs are glittering and then oily with sweat.

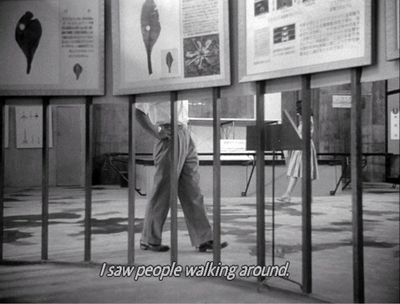

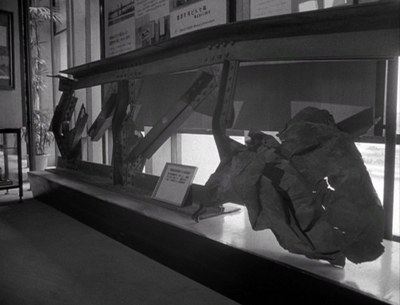

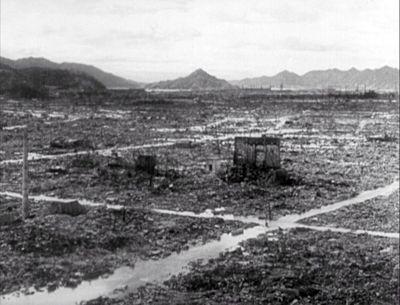

These images give way to documentary-style shots of Hiroshima, both in the present and in newsreel footage. We see modern architecture, a hospital, museum exhibits, city streets, a cheerful lady bus conductor, victims of the nuclear blast, and even restaged scenes of the bombing’s aftermath, taken from fiction films.

Over all the footage float a male voice and a female voice: “You saw nothing in Hiroshima–nothing.” “I saw it all…” She describes what can be seen and understood, while he contradicts her. We return intermittently to their bodies. The sequence concludes with her voice: “I met you here.”

Thus ends one of the most daring sequences in film history, a dense thirteen minutes of imagery, music, and dialogue. I think it’s hard for us today to grasp just how jolting this opening felt in 1959. Ten years after its premiere, when I first saw it (and without much foreknowledge), I was overwhelmed. For me, and I think for many others, cinema wasn’t quite the same after this.

For one thing, there’s the sex. Although it’s portrayed abstractly, the voluptuous skin tones and clutching, twisting arms are powerfully erotic–and poetic. The oily skin might be considered realistic, but the dust particles can’t be justified as anything but metaphorical, perhaps nuclear fallout or the ashes of a city in flames. (Is this like the embracing couples discovered in Pompeii by the heroine of Voyage to Italy?) Later the sexual angle will become more socially specified; it’s an “interracial” coupling, involving a French woman with a Japanese man. An entire “social problem” movie could be made about this situation, which this film takes utterly for granted.

Then there’s the juxtaposition of this stylized intercourse with the bombing of Hiroshima–and naked bodies very different from the ones we see in bed. We’re given smooth tracking shots through a hospital and a museum. In some of his documentaries Resnais had presented locales in solemn, slightly disquieting traveling shots, mimicking a tourist-eye view into a library (Toute la mémoire du monde, 1956) or a concentration camp (Nuit et brouillard/ Night and Fog, 1956). Here, similar traveling shots are more or less anchored to the unseen woman reporting on her impressions.

I say more or less because, in a slippage characteristic of the film, sometimes the camera height is lower than an adult’s eye level, as in the second shot above. And often the camera is withdrawing along the line of the museum exhibits, as if looking backward.

Already the imagery is rendered a little detached from a human perspective. More generally, by suppressing the woman’s face and eliminating diegetic sound, the shots for all their concreteness seem unreal, as if pulled up from memory or imagination.

When the shots segue to found footage (“I saw the newsreels”) and then to strident reenactments, those too seem less historical records or blatant fictionalizing than part of a phantasmagoric vision.

Maps and twisted relics, faces and stones, kitsch and authentic suffering are all put on the same plane, with a disturbing neutrality.

Perhaps this is the tragedy of Hiroshima as absorbed by a consciousness unequal to it. But what consciousness could comprehend it? Night and Fog openly proposed that our minds couldn’t grasp the enormity of the Holocaust. Not that this was a counsel of despair; our very helplessness was a warning to remain vigilant against the next glimpse we might get of human monstrousness. Here another voice challenges the limits of our sympathetic imagination: “You saw nothing.”

What about the opening’s soundtrack? Plaintive piano music, Debussy-ish, passes to strings and woodwinds–slow and brooding, but sometimes disarmingly bouncy. Nothing could be farther from the Mahleresque scores of Hollywood cinema or most documentaries than this chamber-music intimacy. The score pulls a bit away from the images, we might say, seldom emphasizing them even at their most horrific.

In his documentaries, Resnais had pioneered a lyrical, somewhat dry voice-over quite different from the conventional nudging or hectoring Voice-of-God commentary. Like the tracking shots, though, this vocal technique takes on a new effect in a fictional cinema. For one thing, when and where is the conversation occurring? Not evidently during the lovemaking. Before? After? Maybe never? Is it a sort of telepathic exchange, expressing the essence of her tourist-level days in the city and then his assured sense that such an experience blinded her to the real Hiroshima? Interestingly, we’ll learn that he wasn’t in Hiroshima during the attack. So perhaps he, like the narrator of Night and Fog, is warning her against premature confidence in understanding any historical event on this scale.

The woman’s voice dominates the soundtrack, meditating on her lover and her surroundings. Again, it might be a monologue addressed to the man at some point, but thanks to rushing shots through Hiroshima streets, it equates his body with his city. This motif will culminate at the climax, when she compresses her memories of 1944 down to landscapes in Nevers and she decides to give her lover a name: Hiroshima.

Since the mid-1940s, André Bazin had argued that the future lay with long take-filming that respected the continuum of reality–the continuum that Soviet filmmakers had freely splintered in order to make rhetorical and poetic points. Yet with this overture, Hiroshima revived and revamped the Soviet tradition of montage-based moviemaking. The sequence averages a little more than six seconds per shot, a rate seldom seen in European fictional film of the 1950s. The result somewhat recalls the free editing of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, but it anchors the visual disjunctions in psychology and a personal drama yet to be specified.

Bazin had worried that by chopping the world into little fragments, editing by its nature ruled out ambiguity of expression. Yet here was a film that showed, as avant-garde filmmakers had done, that montage could generate poetic ambiguity. Editing patterns could create analogies and associations. The spatter on a rock could evoke the scars on a victim’s head, and the dusted couple of the opening could become ghostly doubles of a victim of radiation.

One could even intercut staged footage and documentary material without hiding the filmmaker’s artifice (as Citizen Kane does with the faked footage in “News on the March”). Free montage and collage-like mixing of documentary and fiction would be hallmarks of 1960s and 1970s films by Alexander Kluge, Dušan Makavejev, and of course Jean-Luc Godard.

Something similar happened with the soundtrack. Detached, unemphatic scores would become part of the repertoire of modern cinema, as would floating voice-overs. Films like Chungking Express and Wings of Desire, to say nothing of the work of (again) Godard, would show the expressive power of voices cut free from story time and space. Montage, as Eisenstein prophesied juxtaposed not only image to image but image to sound.

No later passage of Hiroshima mon amour is as aggressively disorienting as this overture. It’s as if Psycho started with the shower sequence. This opening not only introduces a lot of cinematic and thematic material. It also seeks to sensitize us to images and sounds, as a poem at the start of a novel might sensitize us to language. My discussion of editing in the Criterion installment points out that most of the ensuing film is cut in a pretty orthodox way, respecting the rules of continuity construction. But the sheer disjunctiveness of this prologue prepares us to notice whatever abruptness and juxtapositions do arrive. Assailed by this opening, at once jagged and eerily smooth, we’re set to register some even finer-grained shifts in time and sequence to come.

(2) Flashbacks that aren’t flashbacks

Hiroshima’s script by Marguerite Duras was, Resnais claimed, based on “parallel editing” that would link wartime France and contemporary Japan. But Resnais insisted that this editing didn’t create flashbacks.

Here is another movie, one that Resnais and Duras didn’t make. A French woman visiting Hiroshima on a film shoot turns tourist. She then meets a Japanese man and they have sex. Next day she avoids him, but he pursues her and eventually she agrees to spend the evening with him. In a bar we get the big reveal: the woman explains her wartime love affair and the punishment that drove her out of Nevers. Her past episodes are given in large blocks, perhaps one long flashback. The plot concludes with the man and the woman forced to choose their future.

We’ve already seen that the woman’s tourist-eye view has been fragmented, scrambled, and stylized in the opening montage. We might be tempted to call those images flashbacks, were they not so firmly part of an overall collage including purely documentary material. But once the story proper begins, we, or at least I, am inclined to call the bursts of images from 1944 Nevers flashbacks–brief ones, but flashbacks.

I say this because I take the primary purpose of a flashback is to present story material out of chronological order. A secondary purpose, not always in force, is to represent a character’s memories. Some films, especially after Pulp Fiction, rearrange story order without appeal to character memory. In classical studio cinema, though, flashbacks are usually motivated by a character recalling or recounting an event that she remembers. More often than not the scenes we see in the past aren’t restricted to what she witnesses or even knows about. Memory provides a rationale for the main purpose–revealing action in the past.

But there’s a contrary line of thought that says that a character’s memory ought not to count as a flashback because memories exist in the present. Arthur Miller took this line with respect to the time-shifts in his play Death of a Salesman, as I discuss in Reinventing Hollywood. Resnais, it turns out, felt the same way. For him, the fragments of the past that interrupt the present-time scenes of Hiroshima exist in the present because they’re being remembered. He wrote to Duras during shooting: “The past won’t be expressed by true flashbacks, but will be felt to be present throughout.” In 1968 he reiterated: “In Hiroshima there is not a second’s worth of flashbacks.”

There’s no point in quibbling about terms, but we should note that Resnais thought his interruptive images of the past were capturing something important about how memory works. Memory is fragmentary and jumbled, not operating in the big chronological blocks given us in 1940s Hollywood flashbacks. When asked by his producer if Citizen Kane hadn’t already shifted chronology, Resnais replied: “Yes, but with me, it’s all disordered.”

Moreover, memory is abrupt and fragmentary: Resnais uses cuts, not dissolves, to deliver his memory images. The first instance in the film has become a locus classicus. The woman sees her Japanese lover’s hand twitch, and that leads to another hand, a quick pan to a dead man being kissed, and then the Japanese lover again. This time-shift is literally a flash, lasting only a few frames.

And to insist that memory operates in the present moment, Resnais uses present-time diegetic noise–a train whistle in the scene above, a pop tune on a jukebox later–providing something that literature can’t: the absolutely simultaneous presence of now and then.

Again, Resnais brings into sound cinema narrative strategies that had emerged in silent film. Gance in La Roue, Fredrikh Ermler in Fragments of an Empire, and others had provided rapid-fire memory montages. In most commercial sound cinema, this sort of mental imagery was largely confined to one-off sequences depicting dreams, hallucinations, or mental illness. Resnais and Duras boldly made an entire film in which recollected moments unexpectedly erupt into present-tense action.

Again, though, the filmmakers introduce ambiguity. It’s hard to plausibly assign some of the “memories” of Nevers to the female protagonist. Bare landscapes and abrupt tracking shots of empty streets seem more like Eliot’s “objective correlative,” more oblique representations of feelings, than traces of what the woman has witnessed. Even the invasive images from the past aren’t free of the uncertainties that hover over the opening sequence. This strategy of hovering between subjectivity and “authorial commentary” would become central to 1960s art cinema–perhaps most obviously in Red Desert, where the unrealistic color can be taken as both an expression of the protagonist’s alienation or a more detached, stylized presentation of a modern wasteland.

(3) Talkies and walkies

Griping about Antonioni’s longueurs, Dwight Macdonald remarked that “the talkies have become the walkies.” His complaint captures something important. From Bicycle Thieves through La Strada and L’Avventura up to Linklater’s Before/After trilogy, the idea of building a plot around two characters’ more or less mundane traipsing became a salient option for filmmakers who wanted to stray from classical narrative organization.

But settling down in one place to talk became important too. Serious European cinema often featured dialogue scenes of a length that would have been discouraged in American cinema. Play adaptations like Sjöberg’s Miss Julie (1951) naturally featured such protracted conversations, but so did works by Bergman such as Waiting Women (1952), Wild Strawberries (1957), and Brink of Life (1958). Having revived silent-film montage in Hiroshima‘s early stretches, Resnais and Duras makes peace with their contemporaries in the second part by settling their characters down for two good chats broken by a long stroll.

It all starts when the man declares, after a second bout of lovemaking, that they have sixteen hours to kill before her departure. By Hollywood standards, this period should be handled with dramatic crises leading to the deadline. Instead, we get a quick montage of the city at dusk (with figures unnaturally still, as if rehearsing for walk-on parts in Last Year at Marienbad) and the two of them at a table in the Tea Room bar.

It’s in this lengthy scene that the woman’s memories become most coherent for us and the man. What was private in earlier parts of the film–flashes like the hand on the bed–become externalized in her confession. Again, though, we get Resnais’s version of “disorder.” For one thing, her Nevers story isn’t given in a block, but rather as a burst of fragments. After their second lovemaking, she had already begun to tell her lover about her affair with the German, and the editing was rather choppy: six alternations of past and present in about seven minutes. Now at the Tea Room she’s more explicit about his fate and her punishment. Over twenty-four minutes, the action alternates between Hiroshima and Nevers seventeen times. Often a single shot breaks into her confession.

For another thing, the incidents remembered tumble out of order. Glimpses of her imprisoned in a basement are followed by her ritual haircutting before being sent there. Image and sound fall out of true: we see her pedaling to Paris, we hear her telling us what she read in the newspapers upon arriving. We need to integrate what she’s recounting now with what she’s recalled earlier.

By the time the couple leave the Tea Room, we have a fairly coherent account of the woman’s Nevers trauma. In our alternative film, we’d now have a climax in which she decides to leave Hiroshima or stay. Instead, she and the man separate. She returns to her hotel, washes her face, accuses herself of betraying her German lover with the Japanese, and. . . wanders back outside.

She returns to the Tea Room, now closed. The plot’s irresolution is prolonged. Her lover materializes, as if summoned by her voice-over. The woman, now distraught, tells him she’ll stay. Immediately she tells him to leave. He says he could never leave her. Then he leaves her.

What follows is a string of further evasions and encounters, almost a suite of variations on how a couple can seek to connect and avoid connecting. The film becomes a walkie. Resnais planned the street scenes, he explained in a letter to Duras, by listening to a tape of her reading the commentary and blocking the actors’ movements with wooden dolls.

The woman moves down the street, trailed by her lover. He follows her to a train station, and then to a bar called–you must remember this–Casablanca. She eludes him by letting a slick stranger join her for a drink. The night goes on. Dawn arrives.

In the course of these stop-and-start ramblings, memories return, but images of her lover dwindle, to be replaced by those of Nevers; he has faded into the landscape. As I indicated, these might as well be narrational commentary rather than her memories, with the film’s overarching form juxtaposing the French city with the Japanese one in ways she doesn’t yet grasp.

Now you know why people say art movies seem never to end: They tease us with closure and then deny it. Extended talk scenes and walk scenes, however realistic they may seem in contrast with busy Hollywood plots, are also conventions of this mode of filmmaking. It’s up to the filmmakers to shape them to their immediate purposes.

(4) At the limit

In a plot centered on action–goals, blockages, clashes among characters, struggles to accomplish some feat–you typically have a clear-cut climax and resolution. The protagonist either succeeds or fails. But when you deny that sort of arc, you have to find other ways to inject drama. In Hiroshima, we have a classic instance of the undecided protagonist, who can’t settle on a goal and so drifts from situation to situation, each one of which dramatizes a facet of her character, or of her indecision.

Sooner or later, the plot has to stop, so if there’s no decisive way to end the action, how do you conclude? The most favored option, borrowed from serious literature, involves what literary theorist Horst Ruthrof calls a “boundary situation.” Instead of creating a resolution by what the protagonist accomplishes, the plot confronts the character with something that forces a reevaluation of his or her life. The drama is psychological, not physical; the resolution involves insight, not action of the normal sort. As Ruthrof puts it, the character “in a flash of insight become[s] aware of meaningful as against meaningless existence.” The boundary situation is existential, consisting of “a final vision or revelation, rejection of false moral premises, and the gain of a state of authenticity.”

James Joyce called such bursts of recognition “epiphanies,” and he employed them in his Dubliners short stories. Ruthrof argues persuasively that they can be found throughout modern European literature, from Flaubert and Tolstoy to Conrad and Thomas Mann. In Narration in the Fiction Film, I proposed that many films in the European tradition had recourse to boundary-situation plots. Guido’s acceptance of all the contradictions of his life in 8 ½ and Isak Borg’s reconciliation with his past in Wild Strawberries are fairly clear examples.

Instances of boundary situations are central to two Marguerite Duras novels of the period. The Square (1955) consists of routine encounters on a park bench between an unnamed man and woman. They talk at length each time, and the climax comes when the man declares suddenly, “I’m a coward.” Moderato Cantabile (1956) is set in a cafe, and the conversations are broken by time shifts to piano lessons and a party. Again we get laconic exchanges between a man and woman who don’t know each other, culminating in confession and tears. (“I wish you were dead.”/ “I am.”) Resnais said that he wanted to work with Duras after reading Moderato Cantabile.

In Hiroshima, what, finally, provides closure for the plot? Not the woman’s decision to stay or not; we never know what she chooses. Instead, her affair has forced her to psychological crisis. She realizes that her memories of her first love are partial and impermanent. This shocks her as an act of disloyalty. And she feels that she’s already forgetting her Japanese lover. The passage of time and the waning of emotion come to feel like a betrayal.

The film’s climax is a personal epiphany, not a clear-cut showdown. The woman has come to accept that her past and present are ephemeral, that even the memories she’s making now–of the lover whose skin she adores–will wane. What remains? The late sequences that take her wandering through his city cement the relation between his body and the town: her voice-over repeats the exultant incantation that opened the film, but now we hear it over shots of neon signs and empty streets. So she can name the man: “Hiroshima.” And although we have never had privileged access to his mind, the fact that he rejoiced in hearing her story of her past, in being the only person she had told of it, he may well have achieved a similar epiphany. He reciprocates, calling her “Nevers. Nevers in France.”

This is of course just one interpretation. Whatever thematic implications a critic constructs from the film, though, I think that those will depend on acknowledging the transformative boundary situation that functions as a climax. The woman’s confrontation with the man and the city has forced her to a self-recognition, putting her life in a new light.

Cinema of character rather than plot, we sometimes call it. I’d rather say it’s a particular breed of plot, one that replaces achievement of external goals with achievement of partial, tentative, but still life-transforming insight. A different dramaturgy for a different tradition.

(5) Consolidating innovations

Voyage to Italy; La Pointe Courte.

Hiroshima mon amour changed the way movies told their stories, not least because it revised some trends that had emerged in two other European films of the 1950s.

One was Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (released late 1954). Despite featuring two major American stars, Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders, it was far from an ordinary Hollywood picture. It pushed further that conception of “plotless,” anecdotal narrative on display in Neorealist films like Paisá and Umberto D. The center of the tale is a couple whose marriage is quietly dying. Having inherited a villa in Naples, the characters must decide to sell it. But instead of building a conflict out of this goal, the film fills itself with episodes of the husband’s philandering and the wife’s touring of the region. It settles its plot by an epiphany in which man and wife are mysteriously reconciled.

Voyage to Italy, wrote Jacques Rivette, “opens a breach. . . . All cinema, on pain of death, must pass through it.” “The story is loose, free, full of breaks,” said Eric Rohmer, “and yet nothing could be further from the amateur. I confess my incapacity to define adequately the merits of a style so new that it defies all definition.” Rivette again: “Here is our cinema, those of us who in our turn are preparing to make films (did I tell you, it may be soon).”

The Cahiers du cinéma critics weren’t so eager to welcome Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1956). A married couple drifts through a fishing village, and their meditations on their life together are woven into documentary recording of the locals’ work and relaxation. André Bazin championed the film, but others in the Cahiers team were cool, objecting to the stylized photography and performances. The fact that it was made by a woman probably didn’t help. Against Varda’s wishes Cahiers ran a photo of her as a martyred angel, and it’s hard not to see it as mockery, especially since the caption revels in Henri Agel’s “wicked manhandling” of the film in his review.

Because La Pointe Courte was produced by a company registered to make only short films, it couldn’t achieve commercial distribution and so circulated mostly to ciné-clubs. But most reviews were praising, and today it’s recognized as a bold anticipation of the Nouvelle Vague.

Among those films that La Pointe Courte anticipates is Hiroshima. Resnais, was editor on La Pointe Courte. He initially resisted the job, telling Varda: “Your explorations are too close to mine,” but he wound up working for free.

Three films about couples, then, rendered in a strikingly episodic way. All use long walks and extended talks. All three display a dual structure as well. Rossellini intercuts the activities of husband and wife. Varda, influenced by the parallel structure of Faulkner’s novel Wild Palms, alternates scenes of village life with the couple’s wanderings. And as we’ve seen, Resnais asked Varda to build Hiroshima upon an editing strategy that set the past against the present.

There are probably other antecedents of the film (Resnais was reminded of Il Grido when cutting La Pointe Courte), but I hope I’ve said enough to indicate how Resnais recasts an emerging tradition of ambitious European cinema. He goes beyond it in all the ways I’ve mentioned and more I haven’t, but like all art works it owes part of its power to its reworking of techniques it inherits.

We could list more reasons that this film endures, certainly. Not least: Its unforgettably enigmatic title. Even that offers us ambiguous fragments, in something like an abrupt cut. “Hiroshima mon amour” might suggest “I love the city of Hiroshima.” But there’s no punctuation, no comma or dash that would equate the two terms. Instead, we might take it as a splice. It might be a contrast: “Hiroshima” versus “my love, the German soldier.” But then, since the Japanese comes to stand in for the German, the title would equate “Hiroshima” to him. This would be consistent with the final dialogue: “Hiroshima, that’s your name.” The film’s very title implies the ambivalent juxtapositions that Resnais will build up through cutting.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues at Criterion for making this installment. Thanks as well to old friend Erik Gunneson and to Kelley Conway for discussion of Resnais and Varda. Our entire Criterion Channel series is here.

Bazin’s worries that montage lacked ambiguity are set forth in various essays in What Is Cinema? vol. I, ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (University of California Press, 1967), particularly “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema,” 36.

Resnais’s comments about Hiroshima‘s avoidance of flashbacks are quoted in Jean-Louis Leutrat, Hiroshima mon amour, 2nd ed. (Armand Colin, 2006), p. 84. He describes his film’s “disorder” in conversation with Anatole Dauman, quoted in Jacques Gerber, Souvenir-Écran: Anatole Dauman, Argos Films (Pompidou, 1989), 86-87. He mentions his use of puppets to plan his staging in a letter reprinted in Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima, ed. Marie-Christine de Navacelle (Gallimard, 2009), 66. This lovely edition shouldn’t be confused with Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima!, ed. Raymond Ravar (Brussels: Institut de Sociologie, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1962). This remarkable volume is a detailed book-length analysis of the film and includes interviews with Resnais.

Horst Ruthrof’s discussion of boundary situations appears in The Reader’s Construction of Narrative (Routledge, 1981), 101-108.

See Cahiers du cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave, ed. Jim Hillier (Harvard University Press, 1985), 192-208, for Rivette and Rohmer on Voyage to Italy. The macho mockery of Varda occurs in Cahiers no. 56 (February 1956), 29. For a comprehensive discussion of La Pointe Courte, see Kelley Conway, Agnès Varda (University of Illinois Press, 2015), 9-26. We consider Kelley’s book and Varda’s film here

In Narration in the Fiction Film, I argue that the ambiguous interplay of objective realism, subjective projection, and external narrational commentary is a major strategy of “modernist” cinema or “art cinema.” That argument is sketched in an earlier essay available here, with an update. See also the blog entry, “How to watch an art movie, reel 1.”

I played awhile with the idea that the floating voice-overs in the opening sequence might have been Duras’s efforts to capture what Nathalie Sarraute described as sous-conversation, the unarticulated subtexts that shape what we actually say. The historical timing fits, as Sarraute’s essay positing the possibility, “Conversation and sous-conversation,” appeared in early 1956. (See Sarraute, The Age of Suspicion: Essays on the Novel, trans. Maria Jolas, Braziller, 1963). But I’m not fully convinced of a direct debt. More generally, though, Sarraute’s insistence that the contemporary novel must replace external action with dialogue that hints at internal states seems in accord with the way Duras and Resnais conceived Hiroshima. Maybe here the image track does duty for Sarraute’s “subterranean conversation”? And perhaps the idea of sous-conversation is more relevant to Duras’s own films, particularly the masterpiece India Song (1975).

Hiroshima mon amour.

Venice 2018: A dazzling second feature

Kristin here:

In my first report from the Venice International Film Festival, I described the excitement of seeing three excellent and quite varied films right in a row, at consecutive early-morning press screenings: First Man, Roma, and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. We had to wait a whole two days before seeing what may be the masterpiece of this year’s festival–this year’s Zama, as it were.

I’m sure virtually everyone who attended the press/industry screening of László Nemes’s Sunset was wondering whether it would live up to his first feature, Son of Saul (2015), which won, among other prizes, the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film. It’s one of the more deserving winners of that prize in recent memory.

The narration famously concentrates fiercely on the central character, a Hungarian Jew forced to work in a death camp helping to kill and dispose of fellow Jews. The camera follows him from behind or circles to show his face, and keeps most of the horrors occurring around him dimly visible, in the background and on the periphery of the shots, usually out of focus. Mark Kermode praised the technique as a brilliant solution to the problem of not showing those horrors but seeing them reflected in one man’s attention and expressions. We so much admired this rigorous technique that we incorporated Son of Saul into the new fourth edition of Film History: An Introduction.

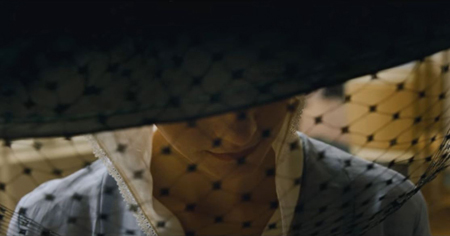

My suspicion is that many present at that first screening of Sunset in Venice were wondering if Nemes could do anything beyond similarly following a single character around, restricting our point of view in a dazzling exhibition of camera choreography centered on a single intense performance. Well, Sunset is based almost entirely on the camera following (below and top) or weaving around the central character, Írisz Leiter, or framing her face in medium close-ups and close-ups.

There are a many of these “nape-of-the-neck” framings, as we might call them, with only Írisz in focus–and not always her. Again, the point of view is highly restricted to what she sees, hears, and knows. She is present in virtually every shot, or revealed to be nearby. The apparent point of view shot into which the character steps is occasionally used in Hollywood and elsewhere, but here it becomes an insistent technique.

I suspect further that, seeing virtually the same device being used again, reviewers dismissed Sunset as a far less original work than Son of Saul. It helped that the latter was a tale of the holocaust and fairly simple to follow.

In my opinion, Nemes has done something extraordinary. He has taken the same basic approach but turned it to an entirely different use. Now the restricted point of view functions to slowly dole out clues in a complicated double mystery plot. The result is complex, tantalizing, and absorbing.

Sunset is difficult to compare with other films or artworks, since it so very original. It is thoroughly modern art cinema. (Nemes worked as an assistant director to Béla Tarr, though neither of his features reflects any direct influence of Tarr.) It also, however, has something of the air of Feuillade serials. Fantômas was made in 1913, the same year in which Sunset‘s action takes place. Sunset deals with an anarchist gang, and at one point Írisz disguises herself as a man and escapes captivity through an upper-story window. There’s also a considerable streak of Grand Guignol (the theatre that was then building to its height of popularity between the two world wars), with actual and attempted rapes, rumors of a grisly murder, and torch-lit attacks by the anarchist gang.

At least two reviewers have mentioned Mullholland Drive as a comparison point. I don’t think the two films have much in common, apart from their pleasantly puzzling aspects. It’s interesting, though, that reviewers grasped at such a comparison as a way of trying to convey the nature of a very unusual film.

In fact, Nemes has said that Blue Velvet was one of his inspirations. That actually makes far more sense to me, with an innocent gradually witnessing unimaginable cruelties.

What just happened?

The film depends heavily on our gradually getting clues and information as Írisz does, and to avoid spoilers I’m going to be vague describing the plot.

The heroine is the daughter of two founders and owners of Leiter’s, a high-fashion hat shop in Budapest. Orphaned, she has learned hat-making in Trieste and returns to Budapest, aspiring to work in the shop and regain what little connection she can with her parents’ heritage. Her application for a job there opens the film, but she is turned down by the current owner of Leiter’s, Mr Brill.

She soon learns that she apparently has a brother, hitherto unknown to her, who has committed a heinous murder five years earlier. While trying to track down the truth about him, she begins to suspect that Brill may be involved in equally hideous crimes. She spends most of the film wandering about looking for clues and trying to make sense of them.

Sunset is not as puzzling or opaque or illogical as reviewers seem to think. One reviewer refers to it as “befuddling,” which it certainly is not, if one pays careful attention. Lee Marshall, one of those who evoked Mullholland Drive, complains that:

Sunset begins to crumble, to offer itself up to scorn and absurdity, once we start asking questions like “Doesn’t Irisz have regular work hours?” or “How come she always manages to get a lift in a coach just when she needs one?”

In fact there is nothing mysterious about either point. The film makes it quite clear that Írisz is not hired by Brill, even though she offers to work for free. She has no “regular work hours” because she has no job. Brill offers to let her sleep in the Leiters’ rundown house where the store’s milliners live, but he clearly is trying to control her attempts at investigating the dual mysteries. He assigns her tasks to keep her busy, but Zelma, the store’s manager and possibly Brill’s mistress, pointedly tells her when giving her a little task to do, “It doesn’t mean you’re hired.” Another task that he assigns her ends up having to be executed by the other milliners, as Írisz constantly defies Brill by leaving the store and dorm at every opportunity. When Leiter and Zelma tells her not to leave without permission, she inevitably and defiantly departs on another investigative foray. Brill’s description of her as stubborn is a considerable understatement.

As for coaches, Írisz’s brother seems to control an anarchist gang consisting largely of coachmen, some of them with motives to drive Írisz to various destinations. Brill uses his coach to fetch her back to the store and as a setting for lecturing her about not defying him by trying to find her crazed, violent brother. Coaches become another way to try and control her movements.

Such mechanics of the plot are consistently motivated, whether we catch the motivation or not. The script is extraordinarily unified and tight, despite its complexity.

After two viewings, I was glad to discover that I had understood the basic plot on my initial one, although many subtle points were filled in.

Clues–but to what?

The narrative is structured through a chain of clues, which we learn only as Írisz does. Írisz is told something–initially, that she has a brother Kálmán. She tries to follow up that clue but is thwarted for a time. Eventually, wandering about or while accompanying the milliners of the shop to various celebrations of the store’s 30th anniversary, she bumps into people who provide her with new clues. Coincidental meetings and overheard conversations are rife here, but as David has pointed out, that’s how narratives work. If there’s one tradition that Sunset doesn’t belong to, it’s realism.

The other tradition it doesn’t belong to, of course, is classical filmmaking. In a Hollywood film, one clue would lead the protagonist to another and that to another, building the chain that resolves the mystery. The action would move steadily, even when obstacles that thwart the protagonist must be overcome, creating suspense. In Sunset, a clue may intrigue the heroine, but she finds no way to follow up on it. There is a frustrating pause another clue crops up. The sense of progression is thus sporadic and somewhat random, rather than linear and strictly causal.

The overarching ambiguities of the plot arise from the fact that Írisz frequently receives contradictory clues and is unable to decide whether Kálmán and Brill are heroes or villains. At one stage Írisz thinks her brother is a sadistic murderer, but later she begins to suspect he is a hero–and still later she again believes him to be a monster. A similar series of reversals happens with Brill. Thus we may conclude that we understand where the narrative development is headed, only to have our expectations reversed. It also takes quite a long time before we realize that the Kálmán Leiter mystery and the Brill mystery are connected, at which point we must rethink them both.

In a few cases we must even infer a clue that Írisz has been given in the interval between scenes. I must admit that on first viewing I was puzzled as to how Írisz finds where a key player in past action, Fanni, lives. Seeing it again, I realized that the scene where Írisz asks Andor, a young servant at Leiter’s, where she can find Fanni ends with Andor asking eagerly, “Can you make him come back?” He’s referring to Kálmán, whom Andor secretly idolizes. A cut begins a new scene with Írisz approaching the building where she finds Fanni. When she again sees Andor in the following scene, he asks, “Did you find the girl?” Thus it is clear that Írisz told Andor she would try to bring Kálmán back, as she may intend to at this point, and that he gave her the address. It’s not easy to grasp moments like this on the fly, but it’s far from impossible.

The decision to restrict our state of knowledge so thoroughly to that of Írisz, pushing the story to the edge of comprehensibility, was deliberate. In an interview Nemes, he says, “We had an overall strategy: the viewer should go into the labyrinth of the story with the protagonist, in order fo feel the disorientation and defencelessness the protagonist experiences. This subjective aspect is what connects ‘Sunset’ with ‘Son of Saul.'”

Rory O’Connor, writing on The Film Stage, caught the labyrinthine spirit of the film better than have the other reviewers I have read. He realized and accepted that one must re-watch the film in order to appreciate its complexities:

Sunset is a film awash with such delicious ambiguities, almost to the point of damaging its basic cogency at times (not least in simple geographical terms). That said, however disorientated I became while watching Sunset, I never grew frustrated. I did, however, begin to backtrack and second-guess myself just a little, which somewhat diminished the experience (and from speaking to other critics, I was not the only one). Yet the ambiguous will always face such early criticisms–just look at Mullholand Dr.–and I not only plan on seeing Sunset again; I will relish the challenge.

This is exactly what great art films can do: make us relish the challenge.

Seeing and yet not seeing

The film is easy to relish, given its original, systematic stylistic elements.

The cinematography has been widely admired, even by those who otherwise dislike the film. The long takes with the camera moving smoothly along with Írisz through crowded streets or circuitous interiors are virtuoso shots, justifying the use of consistently handheld camera as few films have done.

Beyond that, though, the tactic of throwing most planes of the scene out of focus is used in nearly every shot, so that we are forced intensely to concentrate on Írisz. This way we actually see even less than Irisz does, but we are not distracted from the dogged obstinacy and reckless courage of her quest.

The minute control of planes of action is masterly (above and below).

Throwing certain planes out of focus can become a motif (if one watches closely enough). Zelma is often seen out of focus in the backgrounds of scenes. In the frame at the top of this entry, she escorts Írisz to meet with Brill in the opening scene, when Írisz is applying for a job at Leiter’s. Zelma hovers in the middle ground in the frame at the top of the this section; in the frame just above, she’s in the distance, greeting the royalty from Vienna. She is seen for the last time disappearing into a soft, distorting view (bottom of the entry), going to either a posh job attending royalty or a grim fate. As usual, we have no way of knowing which, though we may suspect. The composition hauntingly recalls the early shot of her escorting Írisz, at the top.

I spotted only one shot where Írisz is wholly absent, late in the film, and that is a single tracking movement in the street inserted between two scenes. Nothing is in focus. By following Írisz we may not see everything, but without her we see even less.

Interestingly, Nemes and the cinematographer, Mátyás Erdély, originally intended to try and find an approach quite different from that of Son of Saul:

When we finished ‘Son of Saul’ and began to talk about ‘Sunset,’ we definitely wanted to do something that was very different. For example, if the aspect ratio was 1:1.37 in ‘Son of Saul,’ then it should be anamorphic 1:2.39 in ‘Sunset’; if ‘Son of Saul’ was to be photographed with a handheld camera, then let’s use the dolly for ‘Sunset.’ We made a mood test film, but the camera was in my hands already for the second shot. We realised that the kind of approach that László likes and that matches ‘Sunset’ requires that the camera be hand-held. We decided in advance that there would be dolly and anamorphic, however, in vain–in the end, it was 1:1.85 and a hand-held camera.

The film was shot in 35mm, with the final shot that constitutes the epilogue being set apart by filming on 65mm. Some release prints are available on film, and that’s what we saw in Venice. It was one of only two films shown on 35mm (the other being Vox Lux). See it on film if you possibly can. It’s gorgeous.

I unfortunately haven’t seen Son of Saul on the big screen, but Sunset is clearly a very different sort of film, much more epic in scale. It had a considerably bigger budget and is an historical piece about a beautiful, crowded city. The central set, Leiter’s Hat Store, depicts the luxurious goods that the upper classes and even royalty purchase. The filmmakers built Leiter’s in a vacant lot in a small street in Budapest’s Palace District, behind the National Museum. That way characters could exit the store and be followed by the camera into the bustling street lined with buildings that existed in 1913. As László Rajk, the production designer, says,

The space of ‘Son of Saul’ is an enclosed universe, the strict but also intimate world of the concentration camp. ‘Sunset,’ on the other hand, takes place in an open world, with all the sounds and noises of a big city. This means that in this film we–sound designer and production designer alike–had to create a completely different, open and noisy universe which reflects much less intimacy.

The amazing thing is that the designer took all this trouble and expense even though the lack of focus meant that most of the surroundings, both the built hat store and the real streets, would usually be only dimly visible to the audience. As Rajk adds, however, “those who played–and practically lived–their parts within [the store’s] walls had to believe every single second that they were in the year 1913, in Budapest, at its most elegant hat store full of secrets.”

We do occasionally see the store’s interior in focus, as in this, one of the two true point-of-view shots I spotted in the film:

Still, I would be hard put to figure out that layout of Leiter’s Hat Store or guess where the house where Írisz and the other milliners live is in relation to it.

If there’s one thing that reveals the vast difference between Son of Saul and Sunset, it’s that in the former we dread to see the offscreen, out-of-focus, peripheral things that are happening. In the latter, we yearn for a view of the crowded streets of Budapest and the splendid decor of Leiter’s Hat Shop. We are frustrated, channeled into watching Írisz but having a constant sense of the city which we glimpse occasionally in focus and more frequently in an evocative haze.

I look forward to relishing a third viewing.

As always, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

Many thanks also to Michael Barker and Allison Mackie of Sony Pictures Classics for their help in preparation of this entry.

My quotations come from the interviews with the filmmakers in Hungarian Film Magazine (Autumn 2018), pp. 10, 11, 16, 17, 21. Nearly all of this issue is devoted to revealing interviews with the director, star, cinematographer, set designer, costume designers, and sound designer. In Venice, this issue was provided to the press, and it is available in its entirety online here.

Some photos from our Venice jaunt are on our Instagram page.

Venice 2018: Assorted malefactors

Ying (Shadow).

DB here:

You don’t have to be an addict of crime fiction to notice that bad behavior–from lying and cheating to assault and murder–is a prime motivation in all genres of storytelling. A gripping plot often depends not on innocent mistakes but something worse: an assassination plot (Macbeth), a savage robbery (Crime and Punishment), wicked mind games (Les Liaisons dangereuses). Some of my favorite films from the latest Venice Film Festival feature scurrilous intrigue and a whole lot worse. Hell, in one movie the subject was happy to be compared to Satan, and that was a documentary.

Shadow warrior

After the extravagantly peculiar Great Wall, Zhang Yimou has come back with a more sober, somewhat arty wuxia drama. Leaning a bit on the premise of Kurosawa’s Kagemusha, Ying (Shadow) presents a king trying to reclaim territory with the aid of a crafty general. But he’s relying on a ringer; the real general languishes in a secret chamber recovering from a severe wound. Court intrigue–the general’s wife falls in love with her husband’s double, the king’s sister resents his manipulation of her–builds toward a massive military attack on the Jing stronghold. The sister, in rebuff to the enemy’s insult to her, enlists in the ranks as well.

It’s quite a show. For one thing, Zhang has reengineered the color-design principles of Hero. There each flashback episode was keyed to a different palette.

In Ying, the settings exist almost entirely in deep blacks and soft grays. For most of the film, only flesh and blood are given in their natural colors, and even then they are pastels.

For another thing, in contrast to the overcast skies of Hero and in perhaps another Kurosawa nod, here it’s almost always raining. This constant downpour extends the gray-black color palette of the palace to the massive landscapes.

Above all, the training of the young imposter in a technique of fighting with a metallic umbrella leads to some memorable combat sequences. Little do we realize in the initial practice sessions that the umbrella technique will expand on a grand scale. Pei’s troops invade a town using umbrellas as bobsleds, and they attack the enemy with umbrellas as scythes and buzzsaws. Despite the fact that digital rain doesn’t bounce off shoulders or trickle down the tracery of armor, the water-drenched attack at the climax of Ying yields the tingling sense of tactile spectacle that we’ve come to expect from the maker of Red Sorghum.

Cops and/as crooks

Dragged Across Concrete (production still).

In another but not wholly different genre, we have S. Craig Zahler’s Dragged Across Concrete. I was unfamiliar with his two earlier features, Bone Tomahawk and Brawl in Cell Block 99, though alert viewer Dave Kehr urged me to see the latter last year. (I tried, on streaming, but I gave up because the image was too small; Zahler’s eye is calibrated for the big screen.) Now, seeing this latest enterprise smashed across the Lido’s Darsena screen, I’m here to declare myself a fan.

It’s got a neat structure. There are two protagonists. We’re first introduced to Henry Johns, a discharged prisoner. He’s ready to reenter a life of crime to keep his disabled brother safe and rehabilitate his mom, who’s tricking to support her drug habit. After twenty minutes, he drops out of the plot and we pick up Brett Ridgeman, a cop whose menacing interrogation techniques, captured on cellphone video, result in a suspension. Pressed by money problems and his wife’s MS, Ridgeman decides to get “proper compensation” by ripping off a gang planning a heist. Of course Henry and Ridgeman’s trajectories intersect, while drawing in others: Henry’s sideman Biscuit, Ridgeman’s partner Anthony, and a woman working at the company that’s the target of the robbery.

At two and a half hours, Dragged Across Concrete might seem to be an overinflated genre movie, but it owes its leisurely pace, I think, to the tradition of crime novelists like Lionel White, George V. Higgins, Elmore Leonard, and George P. Pelicanos. In their work crime, duplicity, betrayal, and revenge are at the center of a web of human relations. Unrestricted narration follows outlaws, cops, and bystanders whose fates will be intertwined with acts of violence. You need a certain amount of time to give solidity to the lives of these stakeholders in criminal action.

The sweep of such plotting allows us to appreciate irony, especially when characters misjudge each other’s motives. In Zahler’s film, the split structure of the narration–setting up Henry before we see Ridgeman–pays off in several ways. Having access to the frustrations that push Henry back into crime allows us to judge Ridgeman’s occasional bursts of bigotry as both understandable (given the treatment of his daughter in the neighborhood) but no less hateful. At the climax, there’s a crisis of trust that depends on mutual ignorance. Both Henry and Ridgeman err because each man doesn’t know something crucial about the other.

The film’s length is also warranted by Zahler’s classical approach to composition and cutting. He knows how to exploit anamorphic widescreen, to let the camera stay still and watch action unfolding.

The film’s title summons up Sam Fuller sensationalism (and Zahler’s overheated prose in his novels isn’t far removed from Sam’s). But the film reminded me of Jean-Pierre Melville and Kitano Takeshi, partly for the laconic dialogue but also for the deliberate pacing. (The average shot length is 6.5 seconds, about twice what we find in most Hollywood movies today.) Lacking Tarantino’s self-congratulatory flamboyance, Dragged Across Concrete exemplifies the power of a dry but not unemotional approach to genre conventions.

The Forties, yet again

Charlie Says.

Police thrillers like Dragged Across Concrete became salient creative options in the 1940s, as I tried to suggest in my book about that era in Hollywood. Other 1940s options surfaced in two other crime-based movies I saw at Venice.

The first, rarer choice, was the chaptered film, the movie broken into blocks that are marked as distinct. Meet Me in St. Louis does it by season, Holiday Inn by, well, holidays. We’ve become used to chaptering since Pulp Fiction revived the scheme.

In The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, Joel and Ethan Coen literalize the technique by beginning with an old-fashioned book consisting of six chapters. The tales all center on the American West, and each one is introduced by a captioned color plate and ends with a glimpse of the closing passages of text.

This direct address to the audience is carried on in the first episode, “You seen ’em, you play ’em.” Here the gunslinger Buster Scruggs tries to charm us while singing “Cool Water.” The conceit is that a fancy-pants singing cowboy is planted in the grubby, dangerous west of actual history.

At first Buster dispatches fast-draw artists, but when he meets his match he’s lofted to heaven in a goofy cadenza that recalls stretches of The Big Lebowski.

Thereafter we get tales of bank robbery and lynching (with a shaggy-dog punch line), a bleak carnival sideshow, gold prospecting, a wagon train, and a mysterious stagecoach ride. All are rendered with the patented Coen panache. Such a pleasure to see a movie that is designed, from first frame to last, to give you time to see everything. The Coens’ love of the grotesque, their eagerness to satirize movie conventions while still honoring them, their parodic side (e.g., the opening Leone riffs), and their gift for gorgeous landscapes and catchy tunes–all are here.

Still, the wagon-train episode, much in the spirit of True Grit, shows that not everything is fodder for mischief. The highly formal, archaic dialogues and grave sincerity of the performances in this section are for me deeply moving. The chaptering device itself carries a certain warmth; we might be kids discovering a great-grandparent’s childhood reading.

Mary Harron’s Charlie Says uses a more common 1940s template, that of an inquiry that triggers flashbacks to the past. It’s also, as Harron notes, a woman-in-prison movie. Karlene Faith is a feminist and social activist who counsels three women on Death Row. They participated in the murders instigated by cult leader Charles Manson. As she gets to know them and they probe her own life, we’re shown increasingly brutal episodes of their absorption into Manson’s brood.

The task of Harron and screenwriter Guinevere Turner was to make the women sympathetic and comprehensible. The script might have offered mini-biographies showing how each one’s unfulfilled life led her to fall prey to Manson’s manipulation. Instead, they make one woman, Leslie nicknamed Lulu by Charlie, our primary focus, and through her they lead us gradually into the monstrous crimes.

The early flashbacks, attached to Leslie as she enters the fold, emphasize Manson’s rather mild, almost offhand seduction style. At first he comes across as a gentle, guitar-strumming hippie wooing his followers with a lifestyle challenge: Give up consumerism, learn to live simply, share the love. Certain signals–the men always eat first, Charlie has claim on all the women–are outweighed by Manson’s glowering conviction and the group’s hopes that his songs will earn a record contract.

The flashbacks trace a shift from communitarian idealism to “subversive” rock music (the coded message in the Beatles’ “Helter Skelter”) to whacked-out politics. (Manson promises a race war in which blacks will need a leader like him.) Men as well as women fall under Charlie’s patriarchal management style. By the end, murdering the piggies through home invasion comes to be the ultimate test of Manson family values.

The flashbacks, shot in a nervous style in sun-soaked terrain, contrast with the locked-down camera and drab prison surroundings of the present. The unpretentious production values are matched by a sober style that favors the performances, particularly those of Hannah Murray, Merritt Wever, and in the flashiest role Matt Smith as Manson. In all, it’s a very worthy, unsensational effort to understand how naive idealism can be recruited by lunatic evil.

Better to reign in Hell

American Dharma (production still).

Speaking of lunatic evil, Donald Trump has had many abettors and acolytes, but few are as clever and intellectually pretentious as Steve Bannon. Errol Morris’s interview film, American Dharma, premiered at Venice and was put to the blade in the press conference.

Reporters’ objections seemed to me twofold.

You were too easy on him. You didn’t pose enough hard questions and you cut away when he fell silent. Morris replied that this was an investigation, not a debate. He wanted to probe Bannon’s worldview, not “pin him to the wall, like a butterfly expert handling a specimen.” And Morris does push Bannon on several points, notably the contrast between his apocalyptic intentions (Trump is the “blunt-force candidate, an armor-piercing shell”) and his earnest claim to be fighting for those people who want a stable, steady life. For my part, I thought that Morris scored points whenever the garrulous Bannon didn’t reply or changed the subject.

In addition, Morris peppers Bannon’s discourse with montages of cutaways to internet news and commentary. Like the newspaper headlines of The Thin Blue Line and Tabloid, this swarm of Facebookings, Twitteries, and soundbites acts as both challenge to what’s been said and a reminder of how the media snatch up phrases and images and spew them back at us, complicating and sometimes obscuring our understanding. At the very least, we’re reminded that there is pushback to virtually every lie put forth by the Trump regime: the Resistance will be videoized.

Nothing new here. What did we learn from this? Well, said Morris, we learn that “at the heart of his beliefs is a deep self-deception.” Morris challenged Bannon to explain how, if he believes that Trumpism is a populism on behalf of the forgotten middle class, all his policies are aimed to strengthen the wealthy and weaken the ordinary citizen. Bannon got quiet. And though Bannon claims to be a rationalist, he soon enough rails against rationalism.

All of which makes him a guy who has given a tongue bath to the Blarney Stone. A Hollywood investor with ties to the videogame industry, Bannon strikes me as less a thought leader than a canny VC opportunist, spraying out memes like a scriptwriter in a pitch session. He even assures us solemnly: “The medium is the message.” In his cascade of clichés I saw the desperate self-confidence of a hip boomer who wants to be the brightest boy in the meeting.

Along these lines I thought I learned something else important. Bannon the vaunted intellectual gets his inspiration from pop culture. Most of what I’ve read about his ideas emphasize their philosophical pedigree–his readings in Eastern and Western religion, his defense of Julius Evola–but it turns out that Bannon is a geek like the rest of us.

When he draws life lessons from Paths of Glory and The Searchers, Morris punctures these absurd pretensions simply by literalizing them. This creep casts himself as Kirk Douglas or John Wayne? Like Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight, Bannon claims, he has prepared a carouser for rule before the pupil betrays the mentor. So Morris straight-facedly inserts Welles’ footage, and Bannon, no Fat Jack, is thereby shrunk. Likewise, Morris makes monumental fun of Bannon’s shallowness by building a duplicate of the Quonset hut of Twelve O’Clock High, Bannon’s favorite movie. In this set Bannon, not exactly Gregory Peck, is interrogated before Morris sets it ablaze.

When he draws life lessons from Paths of Glory and The Searchers, Morris punctures these absurd pretensions simply by literalizing them. This creep casts himself as Kirk Douglas or John Wayne? Like Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight, Bannon claims, he has prepared a carouser for rule before the pupil betrays the mentor. So Morris straight-facedly inserts Welles’ footage, and Bannon, no Fat Jack, is thereby shrunk. Likewise, Morris makes monumental fun of Bannon’s shallowness by building a duplicate of the Quonset hut of Twelve O’Clock High, Bannon’s favorite movie. In this set Bannon, not exactly Gregory Peck, is interrogated before Morris sets it ablaze.

I didn’t think that the journalists in the press conference gauged the ways in which Morris made Bannon seem naive. But I always forget that a hermeneutics of pop-culture justification, with The Simpsons and The Matrix fodder for philosophers trying to fill their courses, is taken for granted now. Bannon encountered Twelve O’Clock High when it was taught as a leadership model in, of all places, Harvard Business school. To my mind, Morris shows that the would-be highbrow’s search for allegories in mass culture is a caricature of serious thinking.

Another piece of news: Bannon admits to being a Miltonic rebel angel, one who would rather reign in Hell than serve in Heaven. Think about that. Morris got Bannon to embrace Satan. He asked, with justification: “How many interviewers have done that?” Errol Morris, boy detective, may have revealed the real puppeteer behind Trump’s coup d’état: the petty overachiever swollen with dreams of grandeur drawn from movies.

This is my last dispatch from a festival that became a high point of my cinephiliac life. Apart from seeing fine films in splendid circumstances, talks with Dave Kehr, Chris Vognar, Michael Philips, Glenn Kenny (some choice reviews here), Stephanie Zacharek, Mick LaSalle, Kim Hendrickson, Peter and Françoise Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michel Ciment, Olaf Möller, and other friends have set me thinking ever since.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

For more Venice snapshots, see our Instagram page.

October 31, 2018: Netflix has announced that The Ballad of Buster Scruggs will be narrowly platformed starting November 8 and will premiere on its streaming service on November 16; also on the 16th it will show in selected theaters in the US and Europe, as well as Toronto.

Venice 2018: The Middle East

As I Lay Dying (2018)

Kristin here:

As Variety‘s Nick Vivarelli pointed out earlier this week, Arab cinema is well represented here at the Venice International Film Festival. The same is true of Middle Eastern films in general. I couldn’t catch all them, but here are some thoughts on those I saw.

The Palestine question as sit-com

Comedies about ethnic hostility in Ramallah are understandably rare. For a long time the only one I knew of was Elia Sulieman’s masterly Divine Intervention (2002), though there may be others. Now we have Sameh Zoabi’s Tel Aviv on Fire, a real crowd-pleaser playing in the competitive Horizons section of the festival, a section designed to showcase promising early-career filmmakers.

Despite the title, which might suggest a grim tale of conflict, perhaps involving terrorism, the film is very funny. “Tel Aviv Is Burning” is the name of a daily melodramatic TV series made in Ramallah by a group of Palestinians but enjoyedby both Jewish Israelis and Palestinians–mostly women. (All citizens of Israel are considered Israeli. This means that, ironically, the Israeli Film Fund is required to provide funding to Palestinian projects; it is one of Tel Aviv on Fire’s backers.) The story arc is at a point where a Palestinian woman is assigned to disguise herself as Jewish in order to seduce an important Israeli general and get a key to a hiding place for military plans.

Salam, the protagonist (played by Kais Nashif, who won the best actor award in the Horizons competition), is the lowly nephew of the show’s producer, fetching coffee and helping keep the Hebrew dialogue authentic. Suggesting a bit of action one day, he is promoted to be a writer, despite having no experience or skill. When Saam is stopped for no reason at an Israeli checkpoint (above), he meets a general, Assi. Salam boasts about being a writer on the show, which happens to be a favorite of Assi’s wife. Hoping to impressive his shrewish spouse, Assi puts pressure on Salam to slant the story: the heroine should fall in love with and marry the Israeli general she has seduced. Eager to get away, Salam agrees.

The rest of the story is a cleverly scripted series of twists as Assi makes further demands to make the Israeli general more sympathetic and Salam tries to foist these on his reluctant collaborators. One might argue that the final surprise revelation does in fact make the film lean toward the Israeli side. On the whole, though, Zoabi’s film balances the two factions and manages to convey that the ongoing conflict is absurd, given the many similarities between the two main characters and the universal appeal of “Tel Aviv on Fire” across Israel’s population.

One strength of the film is the stylistic contrast between the main story’s conventional lighting and location shooting and the tacky sets, garish colors, improbable dialogue, and over-the-top performances in the scenes from the TV series.

A microcosm of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Veteran Israeli filmmaker Amos Gitai contributed a program of two films to the festival. The first was a short, A Letter to a Friend in Gaza, the second the feature A Tramway in Jerusalem, both playing Out of Competition.

A Letter to a Friend in Gaza is a evocation of the bitter disagreement between people, even within families, using a text by Albert Camus to sum up the issues in poetic form. I suspect one would need to know a great deal about the Palestinian occupation to fully grasp this oblique work.

The issues are readily apparent, however, in A Tramway in Jerusalem. Set aboard a tram, with occasional shots on platforms where it stops, the action consists of a series of short scenes between a wide variety of citizens. The episodes are separated by titles announcing the time of day, but these skip about, suggesting that this is not a day-in-the-life-of a tram tale but a series of random encounters. The vignettes are not connected, though a few characters recur, most notably a French tourist introducing his beloved Jerusalem to his son. The participants in these short scenes are played by actors, though the only one likely to be recognizable to a broad audience is Mathieu Amalric as the tourist (above).

The scenes suggest a range of possibilities for successful or failed coexistence. For no reason but prejudice a woman accuses a Palestinian man standing next to her of sexual harrassment, and the guards on board immediately throw him to the floor. Two sophisticated young women, one Palestinian with a Dutch passport, the other an Israeli, are standing side by side. They chat casually, clearly very much alike, and when, again for no reason, an aggressive guard demands the Palestian’s passport, the Israeli stands up for her. In an overly long episode, a Catholic priest soliloquizes about the death of the three religions struggling for dominance in their mutually sacred city. The French tourist, determined to idealize Jerusalem, fails to realize that a local couple is poking fun at him by enthusiastically advocating the violent suppression of Palestinians.

The Iranian search narrative endures

Not all Iranian films involve searches by any means, and yet searches, whether they involve a journey or not, provide the structure of many familiar classics like Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Mirror. By chance, two films at this year’s festival show searches involving in one the beginning of life and in the other its end.

Mostafa Sayari’s first feature, As I Lay Dying (Hamchenan ke Mimordam), also played in the Horizons competition. It begins after the death of an old man. One of his sons, Majid, who has cared for him recently, admits to the doctor that he had provided the sleeping pills that apparently killed his father, but the doctor agrees not to mention this on the death certificate. A hint that the time of death is not known provides the first clue in a subtle mystery. Further clues surface in the course of a psychological drama among the four siblings who assemble to drive their father’s body to a small, distant village for burial.

As the journey continues and quarrels develop, the siblings question Majid as to why he chose this remote village for the burial. The length of time that the father has been dead emerges further as a significant factor. By the end, the answers to the three siblings’ questions becomes apparent to them.

Speaking with others who had seen the film, I heard complaints that the story was difficult to understand. I think that As I Lay Dying is something of a mystery story, without being strongly signaled as such, and that sufficient clues are dropped along the way that the viewer should be able to understand the situation by the time the story ends, rather abruptly and perhaps seeming not to offer a resolution. (It would help to know that Muslim burials are supposed to take place as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours.) Certainly nothing is made explicit at the end, though again, an attentive viewer should figure out the implied outcome.

The film takes place largely on a bleak desert road, including some beautiful widescreen compositions reminiscent of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s work in Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, perhaps coincidentally also involving a search in the desert, in that case for an already buried body. (See top.)

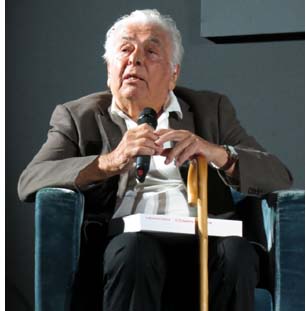

The search narrative goes back at least as early as Ebrahim Golestan’s Brick and Mirror (Khesht O Ayeneh, made 1963-64, released 1966). It was one of the historically important films shown in the “Venice Classics” series of recent restorations.

Brick and Mirror is generally considered the first Iranian art film, having come out three years before Dariush Mehrjui’s classic, The Cow (1969). Golestan was an experienced filmmaker, mostly of documentaries, but Brick and Mirror was his first fiction feature.

The title has nothing to do with the subject matter of the film but is more evocative, being, as Golestan has revealed, derived from a Thirteenth Century Persian poem: “What the Youth sees in the mirror, the Aged sees in the raw brick.” The word “brick” here does not refer to the familiar fired brick, which costs money to buy, but to the simple mud brick, widely used by the poor across the Middle East, since anyone with access to silt and a simple wooden frame can make them.

The story begins one night as the taxi-driver protagonist, Hashem, discovers that a woman passenger has left a baby in the back seat of his car. In a famous scene, he wanders the desolate neighborhood searching for her (see below). Eventually his girlfriend joins him in his apartment to help care for the child. The experience leads her to hope that they can marry and raise the child themselves, turning their so-far aimless affair into a family. The quest to find a practical, humane way to dispose of the baby–or not–takes up the rest of the film. Near the end, a lengthy scene of babies and young children in an orphanage reflects Golestan’s documentary experience.

The new print recalls the rough, often dark look of black-and-white widescreen films of the 1960s, especially those of the French New Wave. Golestan’s story of fruitless wandering and unresolved relationships has been compared by some critics to the films of Antonioni, and it seems clear that Antonioni’s work and other European films of the 1950s and 1960s influenced him. There are, however, distinct differences. While Antonioni deals with the psychology of bourgeois characters (except in Il Grido), the couple in Brick and Mirror are working-class, and their problems are caused as much by their social situation as by any general ennui.

Remarkably, Golestan was present to introduce the film. At 97, he remains articulate and charming. He primarily sketched out his early career and the inspirations for Brick and Mirror. The most interesting point concerned a startling moment during the early scene of Hashem searching the dark neighborhood for the elusive mother of the baby. A close composition of him at the top of a long stairway suddenly leads to a quick series of axial cuts, each shifting further back until he is seen in extreme long shot. The moment reveals the empty staircase and emphasizes the hopelessness of the chase. Golestan emphasized jump-cut quality of the passage and mentioned that he had not seen Breathless at the time Perhaps the moment harks back further, to the axial cuts of static figures used in Soviet films of the 1920s and the work of Kurosawa.

Previously only incomplete, worn prints of Brick and Mirror were available, and then only in rare screenings. The importance of this restoration was emphasized by the festival’s publication of a short book, Brick and Mirror, which brings together a number of essays by Golestan and others. It also describes the restoration, done with the director’s cooperation and accomplished at the L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in Bologna. My thanks to Ehsan Khoshbakht for providing me with a copy and more generally for his important work in reviving Iran’s film heritage, including programing the Iranian season at Bologna that I reported on in 2015.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

For more photos from this years Mostra, see our Instagram page.

[September 12: Thanks to Steve Elsworth for some corrections.]

Brick and Mirror (1966).