Archive for March 2019

Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE

Kristin here:

Given the current year-round feverish speculation about the Oscars, it was perhaps inevitable that the campaign for performer-awards nominees for the three leading ladies of The Favourite was what drew attention to their relative prominence in the film. As Gold Derby (the website subtitled “Predict Hollywood Races”) said during the lead-up to the announcement of the nominees, “The film inspired a lot of debate in the early days of the Oscar derby as to what categories the film would campaign its three actresses [for].” Ultimately it was decided to place Olivia Colman in Best Actress and Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz in Best Supporting Actress. (For those who are interested, this story gives a detailed run-down of those occasions on which two or even three performers from the same film were nominated opposite each other in the same category.)

Esquire was one among many media outlets stating the same opinion: “Yes, Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz are both leading players in The Favourite, and yes, it’s probably category fraud that they were submitted in the supporting category to bolster Olivia Colman’s chances to win Best Actress. It is what is, and we must live with the fact that these two will get the nomination.” Indeed, that was what happened.

Stone and Weisz showed good grace in reacting to the studio’s decision–wise even without the benefit of hindsight–to campaign for Colman as the sole best-actress nominee. They did not, however, suggest that she was the sole protagonist of the film. In an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, Weisz remarked, “I think Fox Searchlight was quite brave to make a film with three really complicated female protagonists. It’s doesn’t happen every day, sadly.” Every year The Hollywood Reporter interviews prominent but anonymous Academy members about their opinions and preferences in the main categories. This year an unknown director complained of the best-actress race, “I don’t understand what [Olivia Colman’s] doing in this category, or what the other two [Emma Stone and Rachel Weisz] are doing in supporting–all three should be the same.” The notion that the three roles were roughly equal in importance was expressed widely during awards season. Google “The Favourite” and “three protagonists,” and many hits will show up in the trade and popular-press coverage.

This notion of three protagonists intrigued me. I believe that the structures of many classical narrative films depend to a considerable extent on how many protagonists they have, what those protagonists’ goals are, and what sorts of obstacles they encounter along the way–often obstacles that lead or force them to change their goals. I based my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999), partly on that idea. For close analysis I chose four exemplary films with single protagonists (Tootsie, Back to the Future,, The Silence of the Lambs, and Groundhog Day), three with parallel protagonists (Desperately Seeking Susan, Amadeus, and The Hunt for Red October), and three with multiple protagonists (Parenthood, Alien, and Hannah and Her Sisters).

Single protagonists are the commonest, and their obstacles are typically generated by single antagonists. Multiple protagonists are somewhat less so. They tend to break into at least two types. There are shooting-gallery plots like Alien, in which the protagonist is the one who, predictably or not, survives the gradual killing-off of the other main characters. Then there’s the network-of-relations plot, like Parenthood and Hannah, in which separate plotlines are acted out, with the protagonist of each related by blood or friendship to the protagonists of the others. More difficult to pull off is the multiple-protagonist plot where the characters are linked by an abstract idea and have minimal or tenuous relationships to each other–Love Actually being a masterfully woven example. (Would that it had existed when I wrote my book!)

The parallel-protagonist plot is relatively rare. I’m not talking about a film with two main characters who are closely linked and sharing the same goal. The buddy-film, most obviously two partner cops as in the Lethal Weapon films, is a common embodiment of this goal, as is the romance where the couple are in love from early on but face obstacles posed by others, as in You Only Live Once.

Parallel protagonists are not initially linked but pursue separate goals that usually bring them together. This might involve a romance conducted from afar, as in Sleepless in Seattle. One character may know the other and seek to be more like him or her, as in Desperately Seeking Susan and The Hunt for Red October. In those two cases, the main characters end by succeeding as they come together and become friends. (Hair would be another example I could have used.) In Amadeus, on the other hand, Salieri fails in his desperate attempt to replace Mozart in public favor and to essentially become him by stealing his Requiem and passing it off as his own.

The triple-protagonist plot

I never considered the category of triple protagonists, simply assuming they would belong within the multiple-protagonist films. Perhaps they do, but The Favourite raises the possibility that such films have a distinctive dynamic, somewhat akin to the parallel-protagonist plot but more complex, or at least more complicated.

Balancing two protagonists who have more-or-less equal stature in the plot is probably not much more difficult than the other types of classical plots. I think that’s largely because these two main characters can come together by the end and become the romantic couple or the buddies who could easily have been the main figures in a dual-protagonist film. Three protagonists, however, are very difficult to balance without one or two of them becoming mere supporting players by the end.

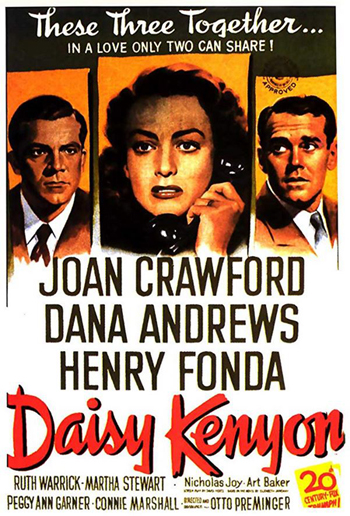

Across the history of classical filmmaking, there are probably a fair number of examples of such a balance being achieved. It’s not easy to think of more than a few, though. The first one that came to my mind is Otto Preminger’s underappreciated Daisy Kenyon (1947). In it Daisy is the mistress of a prosperous married lawyer, Dan, who refuses to divorce his wife and marry her. She meets a genial but traumatized war veteran, Peter, and marries him, but when her initial lover finally files for divorce, she is torn between the two. More about Daisy Kenyon later, the point here being that a triple-protagonist plot is not out-of-bounds for Hollywood and that two people struggling to win a third’s favors is an obvious situation to use in such a film.

The first half of The Favourite displays the long-established relationships between Queen Anne and Sarah. Sarah is stern and commanding with Anne, even cruel at times, and she runs political affairs in the Queen’s place. It is also clear, however, that the two love each other and that Anne, with her various physical and mental frailties, heavily depends on her friend. This half also traces the rise of unfairly impoverished Abigail, Sarah’s cousin. She ingratiates herself with Anne by helping nurse her gout and providing sympathy and deference; she even induces the semi-invalid Anne to dance.

Up to this point we are cued to sympathize with Abigail. She has been the innocent victim of misfortune and is treated cruelly once she arrives at court and Sarah hires her as a scullery maid. The midway turning point, as I take it, happens in the scene where Abigail shoots a pigeon and the blood spurts onto Sarah’s face. Immediately after this a servant arrives to say that the Queen is calling for Abigail rather than Sarah. Abigail is implied to have tipped the balance toward her being accepted as Anne’s favorite.

After this point, we suddenly start to see Abigail’s conniving side, and the pendulum swings as we grasp that Sarah has been displaced in the Queen’s affections through Abigail’s lies about her. In this second half, we are led to recall that Sarah, dominating though she is with Anne, truly loves her and is far more qualified to help run the state than frivolous Abigail is. By the end, all three have managed to make each other and themselves miserable, though Sarah still has her husband and manages to take exile abroad in her stride. None of them emerges as the most important character.

One might argue that Abigail functions as a conventional antagonist. After all, she drugs Sarah’s tea, nearly causing her death–and showing no compunction about it. Yet she, too, is pitiable. Her father gambled her away into marriage with a stranger, and early in the film she is bullied by the other servants. Sarah has her unlikable side and at one point attempts to blackmail Anne by threatening to make public the Queen’s love letters to her–an act that finally drives Anne to reject her. Before that rejection, however, Sarah burn the letters instead, confirming her inability to betray queen and country.

In a review on tello Films Karen Frost writes,“While Stone may receive a modicum more screen time than the other two, this movie really has three protagonists, all of whom are compelling in their own way.” I suspect a lot of spectators, including me, share this impression that Abigail is onscreen or heard from offscreen marginally more than Anne or Sarah. That said, it’s very difficult to measure the presence of each character, given how short the scenes are and how often the women come and go from the rooms where the main action is occurring. And does a scene like the one at the top of this section, where Anne and Sarah converse while Abigail stands mutely in the distance, give equal weight to all three? Perhaps, in that we are here conscious of the latter’s simmering resentment.

In a comparable scene, Abigail is pushing the Queen in a wheelchair. Anne becomes upset and tries to stagger back to her room. We follow her and concentrate on her struggle and emotions for some time before Abigail appears again with the chair. Should we consider this one scene between the two, or actually three scenes, with the two together, then Anne alone, and then the two together again? Even within scenes where two or three of the women are present, weighing their relative prominence in the scene presents difficulties.

The casting is crucial in such a film, since the relative prominence of the actors tends to affect our judgment of their characters’ importance. Rachel Weisz and Emma Stone were both Oscar-winning stars before The Favourite‘s release. Olivia Colman was not well-known in the US, but she had had a long and prominent career on television and occasional films in the UK, The Favourite‘s country of origin. Certainly as Anne she gains the audience’s sympathy early on and becomes plausible as a protagonist alongside the other two.

Scenes and twists

I decided that rather than attempt to clock screen time, I would count how many scenes each character had alone, how many involved two of them, and how many showed all three together. When I say “alone,” I mean only one of the three women is present, though often she is interacting with the main male characters, Lord Treasurer James Godolphin, Leader of the Opposition Robert Harley, and Baron Masham. Given the many very short scenes, the intercutting, the presence of the characters in the backgrounds when the others are emphasized, and the brief intrusion of a character into a scene that overall emphasizes one or two of the other women, my breakdown into segments can’t be precise.

I’ve compared the numbers of scenes devoted to the various combinations of characters in the first and second halves of the film, given the reversed situations of Sarah and Abigail in those large-scale sections.

First, the characters alone:

Anne has only 1 solo scene in the first half/3 in the second. (Total 4)

Sarah is alone 2 times in the first half/8 in the second. (Total 10)

Abigail is alone 7 times in the first half/9 in the second (Total 16)

Abigail’s larger number of scenes apart from the other two women occur largely because she is duplicitous and her situation changes drastically. Anne and Sarah behave straightforwardly, the former because she is too addled to be capable of deception and the latter because she is fundamentally honest, if sometimes brutally so.

Abigail’s duplicity must be revealed gradually. This is done to a considerable extent through two important relationships that help reveal that she is not the sweet young thing that we may have initially taken her to be. In the first half, Harley tries to bully her into acting as a spy in Anne’s bedchamber, passing on to him the political tactics and decisions of the Queen and Sarah. At first it is not clear that Abigail will comply. She also has aggressively flirtatious scenes with Masham. Initially she seems to be Harley’s victim and genuinely attracted to Masham, if in a rather eccentric fashion. Almost immediately after the midway turning point, however, Abigail passes secret information to Harley for the first time. Later, after Anne permits her to marry Masham, it is revealed that Abigail’s primary motive was to restore her lost social standing.

Scenes with Queen Anne with one or the other or both other women:

Anne with Sarah: 6 times in the first half/7 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with Abigail: 3 times in the first half/10 in the second (Total 13)

Anne with both: 6 times in the first half/5 in the second (Total 11)

Here the balance among the three protagonists becomes apparent. Whether intentionally or not, the scriptwriters gave Sarah and Abigail the same number of scenes alone with the queen. Abigail’s access to the Queen is naturally considerably greater in the second half of the film, as she gains her status as the favorite. Surprisingly, though, Sarah’s scenes with Anne are balanced between the two halves. I take this to reflect the Sarah’s determination not to be defeated and also the lingering friendship and genuine love that the two have shared since childhood. If we are to realize by the end that Anne has made a dreadful mistake by rejecting Sarah and sending her into exile, we must be reminded at intervals of how vital Sarah had been in helping Anne run the affairs of state.

The fact that Anne’s scenes with both other women are balanced between the two halves functions to allow us to continue comparing the behavior of both women toward the Queen. We slowly grasp Abigail’s perfidy and Sarah’s prickly steadfastness. The latter is made particularly poignant in Anne’s and Sarah’s final conversation, which takes place through the closed doorway of Anne’s room and ends with Anne rejecting her old friend, despite apologies and pleading.

Queen Anne is in a total of 41 scenes, Sarah in 44, and Abigail in 50, which does suggest that the latter has more screen time overall. The reason for this is probably not that she is more important, but that Sarah and Anne have an established, loving relationship at the beginning, which is easy to set up. Abigail must claw her way up from the scullery to the Queen’s bedroom, which takes more time to accomplish.

The screen time, however, is not the key factor. The film’s impact on the spectator depends to a considerable degree on our struggle to figure out which, if any, if these characters we might identify or sympathize with. There are such frequent shifts of tone and of what we know about each of them that our expectations are systematically undermined in the course of the plot.

In an interview on Deadline Hollywood, Tony McNamara, one of the scriptwriters, describes the effects of having three protagonists:

I thought it would be hard, but it was actually kind of liberating to have three, because it just gave you more options and places to go. Often, an action in a script has a reaction, but just one antagonist and protagonist. But because it’s three protagonists, there was always this cascading effect, and there were more twists. It was fun to have options, [though] there was work to do, making sure that the three were in balance, throughout.

Twists the film has in abundance. Our attitudes toward the characters change time and again. The scene in which Sarah starts letter after letter to Anne, trying to regain her favor, encapsulates all three women’s mercurial behavior. Her openings range from violent resentment (“I dreamt I stabbed you in the eye”) to fondness (“My dearest Mrs Morley”–her pet name for the Queen). The latter is the one she sends, but Abigail consigns it to the fire, finally making any reconciliation between her rival and the Queen impossible.

The ending, with its superimpositions of Anne’s rabbits over the faces of her and Abigail has been criticized as a failure to provide a satisfactory conclusion to the tale of the three protagonists. I’m not sure it is a failure of invention. Abigail’s insinuation of herself into the Queen’s favor began when she noticed the rabbits in the royal bedroom and elicited Anne’s tale of the loss of all seventeen babies she had had, with the rabbits acting as substitutes for them. Abigail had expressed an apparently deep sympathy, but in the final scene Anne sees Abigail capriciously and cruelly press her foot down on one of the rabbits. All illusions that her new favorite has loved her better than Sarah had vanish at this point, if they had not already. The two are portrayed as trapped in a relationship based on grief over unthinkable loss on the part of one and hypocritical manipulation by the other.

Preminger’s balancing act

Daisy Kenyon differs vastly from The Favourite, to be sure. Still, it’s a romantic triangle situation, and the woman who must decide between her two suitors is indecisive up until just before the ending. Dan and Peter are equally plausible as a final choice. Both have faults. Dan is content to carry on his adulterous affair with Daisy indefinitely, and Peter spies rather creepily on her after meeting her, secretly following her to a movie theater so that he can “accidentally” meet her when she comes out. Both clearly are in love with her.

Preminger also managed to cast three stars of more-or-less equal stature. Andrews had gone from supporting roles to the lead in Laura (1944) and was just coming off the success of The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Fonda had had both leading and supporting roles since the mid-1930s and starred in such films as Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Lady Eve (1941), and My Darling Clementine (1946). There is no Ralph Bellamy, the obvious Other Man, here.

There’s another resemblance to The Favourite, in that the man Daisy ultimately chooses then says something that creates a final twist–indeed, it’s the last line of the film. He reveals that not all is as we assumed, and we may be left wondering if, like Queen Anne, Daisy may regret her choice.

Another obvious triple-protagonist film is Ernst Lubitsch’s Design for Living (1933), which once again presents a romantic triangle centering on a heroine who is understandably indecisive in choosing between Gary Cooper (George) and Fredric March (Tom). She moves in with both with an agreement that they will avoid sex. She succumbs to George’s charms when Tom is away and to Tom’s when George is away, and when jealousy between the two men breaks out, marries her rich but boring boss (Edward Everett Horton). The pre-Code ending sees Gilda back with Tom and George in an arrangement that seems no more likely to remain sexless than the first one had.

Again the casting makes the two male protagonists seem equal. March and Cooper were both rising stars at the time, with March fresh off an Oscar win for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932). Cooper had achieved prominence with The Virginian (1929) and followed up with Morocco (1930) and A Farewell to Arms (1932).

This is not to say that all three-protagonist films have this triangle plot with an indecisive woman as the pivot. No doubt there are all sorts of other ways to balance three lead roles. Nor is it to say that three-protagonist films are so common and distinctive as to make me go back and revise Storytelling in the New Hollywood. Still, it’s interesting to see this kind of variant played on more familiar plot structures and to study how filmmakers can go about maintaining the necessary delicate balance.

David has an analysis of Daisy Kenyon‘s narrative maneuvers in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Much ado about noir things

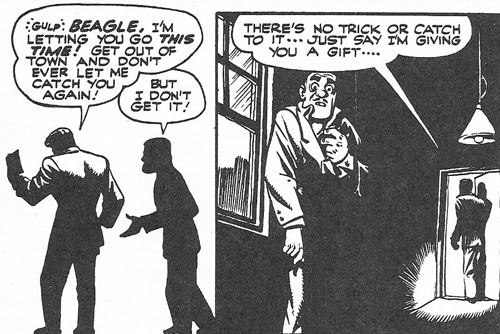

From “The Killer,” Spirit Comics (8 December 1946), by Will Eisner and studio.

DB here:

This is my final effort to cram my latest book down the resisting gullet of the reading public. Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling has just come out in paperback and I’ve been using our blog to trace out some relevant ideas that surfaced in recent books and DVD releases. The first entry dealt with some general issues, the second with popular culture’s drive toward variation, the third with craft and auteurism. This one has murder on its mind.

Noir as mystery and mystique

Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

Crime looms large in Reinventing Hollywood. But I forsake the usual category of film noir. It didn’t exist as a concept for the filmmakers or audiences of the day. It’s the creation of critics, first overseas and then, much later, here at home. That doesn’t make the category invalid, though. Many art-historical categories (Baroque, Gothic) are later inventions, and those can be illuminating. Still, I think we gain some understanding if we situate our inquiry, for a time at least, at the level of what people seemed to be trying to do at the time.

Put it another way. By focusing on noir as the model of Forties narrative, we miss the ways in which the films we pick out under that rubric participate in wider trends. We miss, for instance, the new importance of mystery in all plotting of the period.

In the 1930s, mystery was mostly confined to detective stories. Think of your prototypical 1930s movie; it’s unlikely to have a mystery at its center. (Okay, maybe we’re curious about the identity of Oz the Great and Powerful.) In the 1940s, though, filmmakers began to scatter mystery devices into other genres. Mystery became a central storytelling strategy for personal dramas (Citizen Kane, 1941; Keeper of the Flame, 1943), romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan, 1945), war films (Five Graves to Cairo, 1943), social comment films (Intruder in the Dust, 1949), and domestic melodrama (Mildred Pierce, 1945; The Locket, 1946; A Letter to Three Wives, 1948). Some of what we call noir is part of this trend.

Over the same period, a fairly minor genre got promoted. Psychological thrillers can be traced back to Gothic novels and sensation fiction, but they became a distinct part of crime literature in the 1930s. They became an important genre for cinema in the 1940s, and so Reinventing Hollywood devoted a chapter to films like The Spiral Staircase (1945) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948).

These aren’t canonical “noir” films, at least if your notion of noir stems from hard-boiled fiction. Some rely on the guilty-party plot exemplified in C. S. Forester’s novel Payment Deferred (1926), Patrick Hamilton’s play Rope (1929), and Anthony Berkeley Cox’s novel Malice Aforethought (1931). Less famous but just as interesting is the “woman-in-peril” thriller.

This was an upmarket version of romantic suspense novels associated in earlier decades with Mary Roberts Rinehart and Mignon Eberhart. Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938), one of the top-selling books of the 1940s, lifted the genre to respectability. Revisiting traces the wide-ranging variations that followed in film, fiction, and theatre. (An early draft of that chapter is elsewhere on this site.) Mystery is central to this subgenre. Who is endangering the protagonist? What are the real motives of the people around her, especially her lover or husband? Are her friends complicit? How will she escape?

The gynocentric thriller remains powerful in popular literature today. We’re currently in a rapid-fire cycle of it, typified by the work of Laura Lippman and Gillian Flynn. Some of the books have come to the screen: Gone Girl (2014), The Girl on the Train (2016), and A Simple Favor (2018). The HBO series Big Little Lies (2017-on), turns a fairly satiric domestic-suspense novel into a heavier exploration of spousal abuse. I’ll be writing more about this cycle later (and giving a paper on it this summer), but let me note two recent examples. One takes its Forties sources for granted, the other flaunts them. Both are coming to a screen near you.

In Alex Michaelides’ new novel The Silent Patient Alicia Berenson, an emerging painter, is found guilty of shooting her husband. Because she seems in permanent shock and refuses to speak a word, she’s confined to a mental institution. There the ambitious young psychotherapist Theo Faber tries to ferret out why she remains silent. The narration alternates, Gone Girl fashion, between Theo’s first-person investigation and Alicia’s diary of events leading up to the killing.

It’s a spare tale narrated in a clumsy style that doesn’t distinguish the two voices. And it reminds us that if you become a character in a novel or movie, don’t get into a car. But it does show the persistence of Forties strategies.

There’s the Crazy Lady (recalling Shock of 1946, above, and Possessed of 1947, as well as John Franklin Bardin’s 1948 novel Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There’s the sinister side of the artworld, with a predatory dealers, a demented painter, and portraits that suggest sinister psychic forces. There’s the apparently rational man who becomes obsessed with a woman in a picture (as in Laura, 1944). There’s a mythological parallel to the heroine (here, Alcestis; in The Locket of 1946, Cassandra). There’s the therapeutic motif of a doctor falling in love with a mentally disturbed patient (Spellbound, 1945). And there is, of course, a twist depending on suppressive narration.

The Silent Patient quietly absorbs these Forties conventions, with virtually no mention of the tradition. At the other extreme sits the self-conscious geekery of A. J. Finn’s The Woman in the Window. In an earlier entry on the eyewitness plot I swore I wouldn’t give space to this novel, largely because I resist people swiping titles of movies I admire. But after alert colleague Jeff Smith told me, “It’s as if he read your Forties book,” I figured I could break my rule.

Indeed this eyewitness thriller relies on a great many narrative tricks from the period. We get a Crazy Lady, dreams, hallucinations, an unreliable narrator, the drama of doubt, flashbacks within flashbacks (with the revelatory one coming at the end), and a Gothic climax punctuated by lightning bursts. Also, inevitably, a car crash.

The book’s epigraph comes from Shadow of a Doubt, and the pages that follow are littered with references to 1940s movies. Our homebound heroine lives in thrall to DVDs and TCM, though her impending fate gives a new meaning to “Netflix and chill.”

The Woman in the Window is soaked in contemporary movie-nerd culture. The heroine updates Jeffries’ tech gear in Rear Window by shooting video footage of the suspects across the way. She mentions Kino and Criterion discs, and even refers to “diegetic sound.” (Has she read Film Art: An Introduction?}

Like The Silent Patient, Finn’s book illustrates how much modern thrillers owe to Forties movies. But it also exemplifies how noir has become a kind of brand and a signal of hip tastes. Maybe that’s a reason to back off the label for a while.

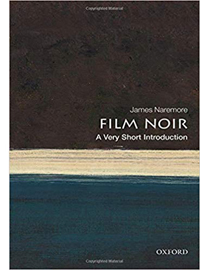

Noir in brief

But let’s not back off too far. Any student of 1940s Hollywood can learn a lot from the vast literature on noir. The most recent item to cross my desk is James Naremore’s Film Noir: A Very Short Introduction. (It’s due to be published in April.) As you’d expect, the author of More Than Night will bring a wide-ranging expertise to a compact survey of books, films, and ideas.

I wish I could’ve signaled his study of “the modernist crime novel” in my book. I emphasize how modernist narrative techniques shaped middlebrow fiction, which in turn made their way into movies. Naremore points out some more direct affiliations:

I wish I could’ve signaled his study of “the modernist crime novel” in my book. I emphasize how modernist narrative techniques shaped middlebrow fiction, which in turn made their way into movies. Naremore points out some more direct affiliations:

In the previous two decades modernism had influenced melodramatic fiction of all kinds, and writers and artists with serious aspirations now worked at least part time for the movies.

When the trend reached a peak in the early 1940s, it made traditional formulas, especially the crime film, seem more “artful.”. . . And yet there was a tension or contradiction within the Hollywood film noirs of the 1940s. Certain attributes of modernism—its links to high culture, its formal and moral complexity, its frankness about sex, its criticism of American modernity—were a potential threat to the entertainment industry and were never fully absorbed into the mainstream.

Naremore goes on to discuss several influential writers—Hammett, Greene, Cain, Chandler, Woolrich—and key films such as The Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity as examples of “tough modernism” in fiction and film. One of the virtues of the book is its sweep: it covers nearly eighty years of noir on the page and on the screen. Like everything else Jim writes, it’s essential for film fans and researchers. His recently inaugurated webpage displays his range of interests.

The Big Nutshell

Did the 1940s give us the habit of calling a movie The Big Whatever? True, we had The Big Parade in 1925 and The Big Broadcast of 1935 but it seems that the next decade was quite big on bigness. Apart from The Big Sleep (1946), we had The Big Store (1941), The Big Street (1942), The Big Shot (1942), The Big Clock (1948), The Big Steal (1949), and The Big Cat (1949). Many episodes of Dragnet, as both radio show and later TV program, had The Big . . . as their title prefix.

So I wish I’d known about David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. It’s hard-boiled reportage in the vein of Courtney Riley Cooper’s flinty Here’s to Crime (1941). Maurer introduces us to a repertoire of grifts that will nimbly extract dough from the mark (aka the fink).

So I wish I’d known about David W. Maurer’s 1940 book The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man. It’s hard-boiled reportage in the vein of Courtney Riley Cooper’s flinty Here’s to Crime (1941). Maurer introduces us to a repertoire of grifts that will nimbly extract dough from the mark (aka the fink).

There are small-scale operations (the short con), as well as complex ensemble efforts using, naturally, the Big Store (fitted out with a fake racetrack wire). The scam shown in The Sting (1973) is a Big Store con. Maurer provides a sociological study as well: “Confidence men, like civilians, mate once or more (usually more) in their lives.” I don’t know exactly how I would have worked in a footnote to The Big Con, but I would have tried.

While Maurer was writing The Big Con, something more sinister was going on. In her four-story farmhouse, Frances Glessner Lee was laboring over the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death.

These were crime scenes presented on an itty-bitty scale. Little corpses—stabbed, drowned, hanging—are surrounded by the most banal furnishings. Exquisitely miniaturized chairs, rugs, lamps, beer bottles, calendars (“Corn Products Sales Company”) surround the pathetic figures. A woman stares up from a bathtub alongside tiny towels, hanging socks, and even a simulacrum of tap water endlessly gushing. Frank Harris is found drunk and crumpled in front of a saloon; the next scene shows him dead in his cell. What happened?

Ms Lee, a wealthy devotee of criminal investigation, recreated these grim tableaus as audio-visual aids for police training. Exactly how useful they were as pedagogy isn’t clear. The imagery recalls classic mysteries, and it’s not surprising that Lee was a friend of Erle Stanley Gardner, creator of Perry Mason. Yet her scenes have a creepy melancholy quite alien to Golden Age puzzle plots. As a testimony to the 1940s fascination with aestheticized homicide, they’re close to Weegee or Chester Gould. But they’re rendered as fastidiously as a Joseph Cornell box. I see in the Nutshells the populist Surrealism that led, at the other end of the scale, to Wisconsin’s House on the Rock (which began construction in the 1940s).

Corinne May Botz is the David Fincher of the Lee oeuvre. Her camera in The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death gets deep into the scene and renders the most upsetting images with a cold precision that matches the staging. These bits of cloth and plastic, sculpted and arranged with maniacal precision, make death at once childish and bleak. Blown up in Botz’s photos, the scenes radiate anxiety and menace. Dollhouse noir?

Frozen movies

Will Eisner, “Beagle’s Second Chance,” Spirit Comics (3 November 1946).

In Reinventing Hollywood I suggest that techniques we find in the films have their counterparts in popular novels, short stories, plays, and radio shows. Artists in these media were also exploring shifting time frames and viewpoints, voice-over narration, and other devices. I called it the multimedia swap meet, where mass-culture wares were available for use and revision (thanks to the variorum).

A Christmas gift from alert programmer Jim Healy reminded me of my neglect of a major medium. Jim gave me the wondrous Comic Book History of Comics by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey. Each teeming page is jammed with facts, figures, and follies from the history of American comic art, illustrated with frantic drawings and exploding panels. As a comics fan, I should have mentioned how the narrative strategies I traced in film have counterparts in many of the trends Van Lente and Dunlavey cover.

A Christmas gift from alert programmer Jim Healy reminded me of my neglect of a major medium. Jim gave me the wondrous Comic Book History of Comics by Fred Van Lente and Ryan Dunlavey. Each teeming page is jammed with facts, figures, and follies from the history of American comic art, illustrated with frantic drawings and exploding panels. As a comics fan, I should have mentioned how the narrative strategies I traced in film have counterparts in many of the trends Van Lente and Dunlavey cover.

One example is shown at the top of today’s entry: an effort toward optical POV in Will Eisner’s The Spirit. Eisner renders almost all the panels on that page as subjective. At the time, films were exploring the same idea for certain scenes (e.g., Hitchcock’s work), for long stretches (Dark Passage, 1947), and for nearly the whole movie (The Lady in the Lake, 1947).

Of course Eisner’s Spirit tales evoke noir visuals as well–and become more noirish as the Forties go along, at least to my eye. Other cartoonists, particularly Chester Gould and Milton Caniff, push toward the steep compositions and chiaroscuro lighting we find in the films. I’m inclined to say that the movies got there first; I argued in The Classical Hollywood Cinema that noirish visual designs were often recruited for scenes of crime and mystery in the 1920s and 1930s. (A blog entry found examples from the 1910s.) I suspect that artists of the comics adopted those schemas when they started to make cops-and-robbers strips. By the 1940s, though, with Eisner and others, the visual dynamism pushed beyond what we see in most films. Except, as always, for Welles: Mr. Arkadin seems an Eisner comic brought to life.

Vanilla noir

The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950).

Noir is a tricky category because it’s a cluster concept. It can refer to visual style, matters of narrative or narration (haunted protagonists, plays with viewpoint), genre (drama, not comedy), and themes (betrayed friendships, dangerous eroticism, male anxiety). Take away one dimension and you might still be inclined to call the movie a noir. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956) has a noir plotline, but its disarmingly drab images mostly lack the low-key look. And maybe someone would call Murder, He Says (1945) a noir comedy.

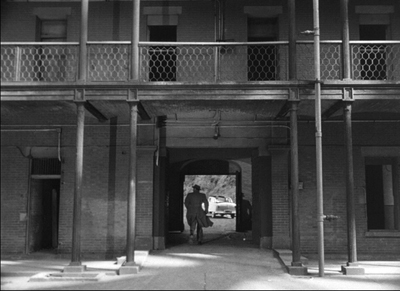

A good example of mild noirishness is The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950), now made available in a handsome UCLA restoration from Flicker Alley. Ed Cullen is a tough homicide cop lured by a rich woman into a murder plot. He helps her cover it up, but his younger brother, just starting out in the police force, gets too close to solving the case.

The action climaxes in a vigorous showdown in San Francisco’s Fort Point compound. Director Felix Feist, who gave us the better-known The Devil Thumbs a Ride (1947) and The Threat (1949), exploits this impressive location.

Most of the film is more soberly shot, but one long take of an interrogation uses the typical Forties image: a low-slung camera, figures deployed in depth and rearranged as the pressure intensifies.

The Blu-ray release includes a well-filled booklet and two excellent documentaries. Brian Hollis pinpoints the use of San Francisco locations and has interesting comparisons with Vertigo. A second short provides background on the participants and the film’s production, with shrewd remarks on the film’s casting by Eddie Muller. I was also pleased to see that the film, full of smokers, includes Hollywood’s favorite brand of the Forties, Chesterfields.

From Sunrise to Moonrise

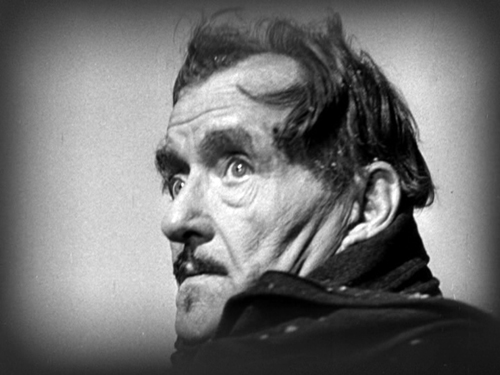

Moonrise offers a different negotiation of noir conventions. The Criterion Blu-ray release, produced by Jason Altman, makes this 1948 classic available in a much better version than I’ve seen before. I discuss the opening in Reinventing, taking it as an example of a deeply subjective montage sequence, and I posted the clip online as a supplement.

After knowing the film for years, I expected that the 1946 source novel by Theodore Strauss would have some of the delirious prose we get in Steve Fisher’s I Wake Up Screaming (1941). Strauss wrote film journalism for the New York Times, so it seemed likely he would incorporate some of the pseudo-cinematic techniques of voice-over, subjectivity, and the like, as do other crime novels I mention in Reinventing. Instead, the storytelling is standard hardboiled. Here, for instance, is Strauss sketching the buildup of grudges that leads Danny to kill his long-time nemesis Jerry:

Every time his fist smacked into Jerry’s soft side or smashed Jerry’s mouth against his teeth Danny knew he was paying back. He was paying back for that first day at grade school when he was the new kid and Jerry had whipped him with the whole playground backing him. He was paying back for the night Jerry and his gang took him into the alley and tarred him because Jerry said he’d squealed to the principal. He was paying back for the scar on his shoulder left by Jerry’s cleats in scrimmage seven years ago. He was paying back for every dirty crack jerry had ever made about him or his father in public or private, to his face and behind his back. Paying back. Paying pack good.

Borzage’s movie turns this compact backstory into something much more hallucinatory.

The montage intersperses a hanged man with vignettes of his son being bullied from childhood on. First the rippling miasma seen under the credits gives way to blobs appearing as if in reflection. The camera reveals them as mysteriously projected on a wall (or is it a screen?), and then it picks up feet stalking toward the gallows.

Witnesses are revealed standing in the rain, and the camera rises to show the execution as shadows flung onto the wall/screen.

It seems more of a feverish childhood vision of the hanging rather than any veridical presentation. Cut to a view of a baby with a doll dangling over his crib. This traumatic image is followed by scenes of jeering schoolboy cruelty. (“Danny Hawkins’ dad was hanged!”)

It’s a murky, delirious passage. Its tactility, with mud smeared into Danny’s face, admirably prepares us for a film steeped in swamp water and dank foliage. Here, as elsewhere, 1940s filmmakers are rehabilitating the expressionist devices of late silent film.

The rest of the film doesn’t present such overpowering imagery, but by continuing the opening sequence in the present, following Danny as he drifts past a dance pavilion, the narration makes Danny’s fight with the bully Jerry a furious culmination of all the indignities he’s suffered.

The plot traces a familiar Forties trajectory, following a flawed but not despicable man driven to conceal a crime. In the course of his evasions, he tries to make a life with a compassionate woman. There are many wonderful scenes, including a suspenseful ride on a ferris wheel and a lyrical dance in an abandoned mansion. The lawman tracking Danny comes off as gentle and compassionate. The rippling imagery of the opening recurs in the background of shots, as if the swamp were waiting to claim Danny. As Hervé Dumont points out in a bonus conversation with Peter Cowie on the Criterion disc, all this gloom eventually clears to arrive at a sun-drenched resolution quite different from your typical noir payoff. (Though it’s faithful to the novel, as indeed most of the film’s plot is.)

This time around I was struck by the delicacy of Frank Borzage’s direction in the less flamboyant passages. This master of silent cinema knows how to let a pair of hands show distress, an effort toward tenderness, and then rejection.

Borzage was most famous for his feelingful melodramas Humoresque (1920), Seventh Heaven (1927), and Street Angel (1928). He made those last two features at Fox while F. W. Murnau was there, and it’s probably not too much to see the brackish mist of Borzage’s 1948 film as reviving the look of the nocturnal countryside scenes of Sunrise (1927).

Some shots might almost be homages to Murnau’s film.

The compositions remind us that the 1940s deep-focus style isn’t far from the wide-angle imagery Murnau pioneered in the silent era. Although Strauss’s novel gives the Borzage film its title, we’re free to imagine Sunrise (in which the moon figures prominently) as a prefiguration of Moonrise, in which we never see the moon rise.

A final thanks to all who have picked up a copy of Reinventing Hollywood. Apart from its arguments, I hope that it steers you toward some new viewing pleasures.

Film rights to The Silent Patient, whose author has an MFA in screenwriting, have been sold to Annapurna and Plan B. Amy Adams is set to star in The Woman in the Window, from Fox 2000.

It seems that The Woman in the Window owes a debt to more than movies. A detailed profile of its author in The New Yorker suggests that exposure to Highsmith’s Ripley novels at an impressionable age can have serious consequences, especially if you wind up among the Manhattan literati.

Robert C. Harvey offers a careful analysis of Eisner’s Spirit story, “Beagle’s Second Chance,” in The Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History (University Press of Mississippi, 1996), 178-191. Interestingly, the chapter is titled, “Only in the Comics: Why Cartooning Is Not the Same as Filmmaking.”

The most comprehensive book on Borzage’s career I know is Hervé Dumont’s de luxe edition Frank Borzage: Sarastro à Hollywood (Cinémathèque Française, 1993). An English translation was published in 2009.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Urk.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Eep. I try to do the film, and its genre, justice in another entry.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Omigosh.

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix,” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. So I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death: Parsonage Parlor, by Lorie Shaull.

The movie experience as format: A 3D state of the union

Kristin here:

On February 13, the day after I posted my blog entry, “3D in 2019: Real Dvided?,” I received an email message from Belgian film critic David Vanden Bossche. He had been intrigued enough by my post to investigate the number of 3D screenings on offer in Belgian cinema chains in comparison with “standard” or “premium” 2D screenings. I had found 3D screenings the distinct minority in our local Madison theatres, even early in films’ runs. David found the opposite in Belgium

To extend his investigation, David enlisted his colleague Tim Bouwhuis to analyze the proportions of 3D screenings in the Netherlands.

David and Tim’s resulting online article, “Filmbeleving als Format: A 3D State of the Union,” was posted on March 13 on Enola.be, a film and music site in Flemish. David kindly offered to send me an English translation of the piece. It turned out to be quite intriguing, since 3D in Belgium and the Netherlands is considerably more robust than in the US. I mentioned in my post that areas of the world outside North America have a higher proportion of 3D-equipped screens than we do here. The attention usually focuses on the Chinese market’s enthusiasm for 3D. This enthusiasm is often credited with encouraging Hollywood studios to keep making 3D films despite their waning popularity in North America. But other countries favor 3D as well, and it’s valuable to have an examination of a pair of small European markets.

Our thanks to David and Tim for allowing us to present their article here as a guest post.

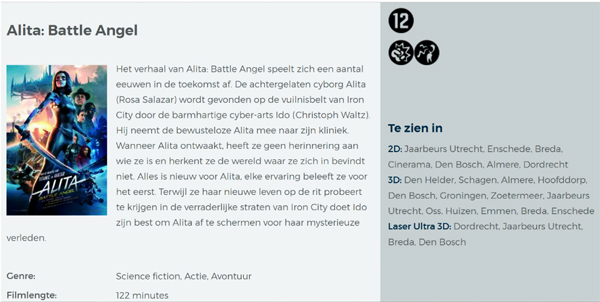

On 12 February, following the American premiere of Alita: Battle Angel, Kristin Thompson posted a new entry, 3D in 2019: Real Dvided? Thompson investigated the state of 3D within the contemporary theatrical environment in the United States. Her conclusion was crystal clear: 3D’s share within American movie screenings has steadily declined in the last decade, when Avatar urged most theatre chains to make the switch to 3D projection. The numbers Thompson presents abundantly show that American multiplexes are less and less inclined to include large numbers of 3D screenings in their programs, and that 3D is losing ground to another ‘premium’ format such as IMAX.

Those findings were intriguing enough suggest a closer look into the Belgian situation. Because that is ultimately a small market, I contacted fellow film critic Tim Bouwhuis, who lives in the Netherlands and could thus provide some information on the particular situation in his home country. Our research allowed us to collect an acceptable amount of material and provide us with numbers that paint a rather different picture than the one to be found in Thompson’s piece. The data we collected show a different evolution for 3D in these two countries and possibly in the whole of Europe. Further research could shed some light on this. Even a limited study, however, offers some possible explanations for these differences. This entry will tackle some of them.

United States: RealDvided

Before dealing with the situation in Belgium and the Netherlands, it is probably a good idea to summarize what Thompson presents in her piece.

Starting with screenings in her hometown Madison, Wisconsin, she observes that 3D’s share in the number of screenings of recent blockbusters is surprisingly limited. Thompson broadens the scope with additional numbers from other cities, concluding that this is definitely not a local issue.

The growth in 3D emerges with the success of Avatar and the consequent peak in 3D earnings in 2010. Since then, 3D’s share of film grosses has been in decline. Production of 3D television sets – a prime feature in store windows just a few years ago – has all but halted. Even if one should exercise some prudence in declaring the death of 3D in a theatrical environment, it is safe to state that its intrusion into the living room has failed spectacularly.

It is remarkable that other ‘premium formats’ (Thompson refers to these as PLF – Premium Large Formats,’ a term we will stick with here) such as IMAX or various “ultra” and “grand” large-screen auditoriums (usually offering extra comfort and superior sound) are gaining in popularity, while 3D is on the decline. That means the public is willing to pay extra for a ‘premium’ – PLF upcharges are as high or higher than those of 3D – and apparently often prefers to pay for PLF rather than for 3D. This process obviously suits the theatres’ economic agenda: a large part of the extra income returns to the distributor and – as Thompson points out – there’s also the extra cost for 3D glasses. The upcharges may also make the visitor less inclined to spend money on food & beverages, a vital source of income for theatres. That means the final balance might be rather negative from the theatre’s point of view in the case of 3D revenues. The fact that PLF’s may net a larger profit thus adds another extra factor working against 3D.

One might expect that in case of Alita the figures would be rather different. The film is produced by James Cameron, one of 3D’s most prolific advocates and arguably one of the few directors – along with Ang Lee, Martin Scorsese, Werner Herzog, Gan Bi and (even) Jean Luc-Godard–who actually tried to explore the true potential of 3D’s formal cinematic language.

The numbers Thompson presents, however, show that even an “event” film such as Alita does not always encourage US theatre owners to schedule more 3D screenings. Thompson points out that there might also be a more practical issue at work here: the clarity of the image is one of the more troublesome issues 3D faces. To solve this, Cameron and Roberto Rodriguez (who took the directing honors when it turned out Cameron was too busy preparing the Avatar sequels) made sure the DCP’s (digital cinema package, used to send movies to theatres since the disappearance of film stock) came with a set of guidelines. These technical complexities, combined with pricey investments and low returns, make for a cocktail that encourages theatres to drastically cut back on the number of 3D screenings.

Belgium: The Kinepolis experience

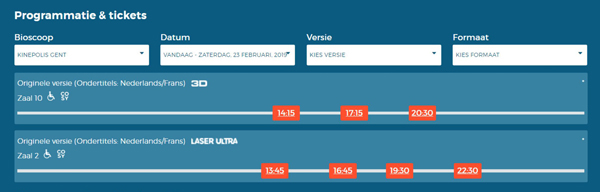

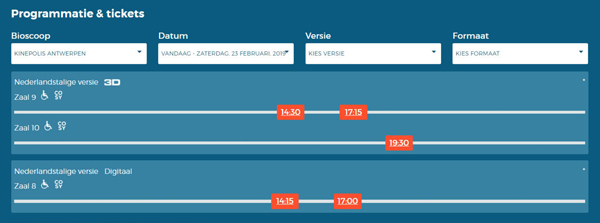

Intrigued by Kristin Thompson’s article, I gathered comparable statistics for Alita in Belgium. See the top image for an ad listing the formats available during the first week of release at Kinepolis Group theatres in Belgium.

That’s a lot of 3D ! No fewer than four of these six formats integrate 3D into the theatrical experience. Obviously, a film such as Alita is likely to receive such a treatment and definitely during its first week. It is also necessary to look – as Kristin Thompson did – at the relative percentage of 3D versus “standard” 2D screenings. A ten day interval seemed ideal to reassess the situation. Here are schedules for two Kinepolis theatres ten days after the film’s opening.

As it turns out – depending on the Kinepolis theatre one chooses to visit – 3D still makes up between 42 and 67 percent of Alita’s daily screenings. The highest number is reserved for Kinepolis Brussels, with the theatre being the only one equipped with a full-fledged IMAX screen. IMAX as a PLF in Belgium is used exclusively for 3D screenings, save for some very rare exceptions.

As pointed out already, Alita can be regarded as an exceptional production that integrates 3D as part of its raîson d’être and its promotion. Alita’s figures might be exceptional, so looking at a comparable title might be necessary. The Lego Movie 2 made its debut about three weeks later, is also shown in 3D and thus makes for a perfect comparison.

3D’s share is smaller here, but still 40 percent of the screenings are in the 3D format, a number well above the American averages.

Because two titles might still represent a distorted sample, we contacted Kinepolis Group Belgium and asked them to provide us with some material that would allow to have a better general idea about the significance of 3D within their total number of screenings and their profits and the way this share has evolved (or is evolving).

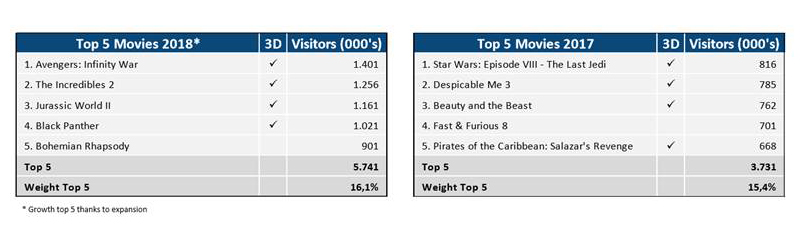

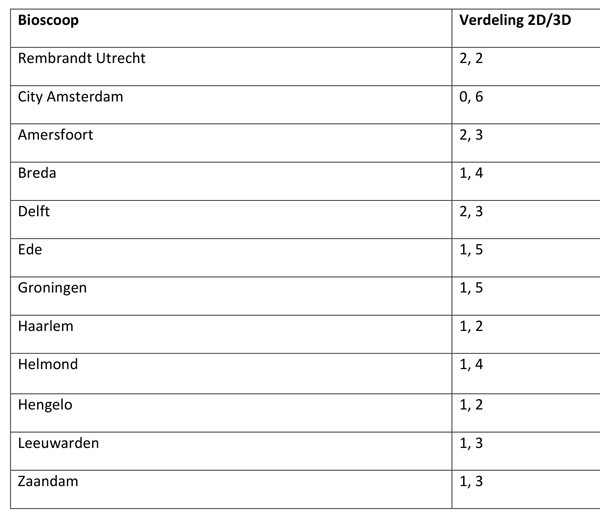

These numbers are clear enough to allow some conclusions. Both in 2017 and 2018, 4 out of 5 of the most popular films for Kinepolis Belgium were 3D movies. 2018’s numbers even show that both the relative share and the absolute numbers (and thus the weight of the top 5 and 3D) are indeed increasing. Obviously that does not mean that every paying visitor opted for 3D (or one of the various combinations of 3D and PLF), but as the general share of 3D screenings for every movie released in this format at Kinepolis theatres in Belgium is situated anywhere between 40 and 60 percent of the total number of screenings. That means this percentage can be applied to these numbers.

The Kinepolis representative pointed out that the percentage of 3D screenings for a movie is determined on the basis of the quality of the 3D imagery and the way the 3D format enhances the viewing experience. Alita is perceived to be a prime candidate for these arguments and thus the number for 3D screenings is very high and at the lower end for The Lego Movie 2. Even if one sticks to the lower end of the scale, however, the importance of 3D screenings within the total number of screenings is still remarkable.

Beyond Kinepolis

All those results lead to a single clear picture: unlike the American situation, 3D is still positions itself as the preferred “premium format” in Belgium. Its impact on the total number of screenings (in Kinepolis theatres) is still very significant and shows no signs of diminishing.

I believe there are a few elements at play to create this situation. One of the first emerges when we take a look at the Alita screenings outside of Kinepolis theatres. Another large chain of theatres, UGC, provides a useful comparison. (Most independent movie houses have not screened Alita). The schedule immediately below is for a UGC cinema in Antwerp, and below that, one in Brussels.

In Antwerp there is not a single 3D screening to be found; in UGC Brussels, there’s just one, while the same day lists 8 standard screenings. The discrepancy between these numbers and the ones at Kinepolis are easily explained: UGC has a very limited number of 3D screens.

Slowly it becomes clear that the very specific situation of the Belgian movie theatre environment is an important factor in all of this.

Kinepolis Group was formed through the joining of two large family companies, the Claeys & Bert Groups. At the start of the 19080s, they began setting up a chain of theatres that no longer consisted of the smaller movie theatres Belgium had known up to that point. Their theatres introduced multiplex to the country. “Decascoop” in Ghent (first 10 screens, with two added later) and the other early Kinepolis theatres benefited from the rise in ticket sales in the early eighties and consolidated their position by being the only theatres around the country able to show box-office hits such as E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial and the “Indiana Jones” trilogy, on multiple screens. 1988 saw the inauguration of Kinepolis Brussels – at that time one of the largest theatres in Europe – along with the first IMAX screen in the country (and most neighbouring countries).

At that time though, IMAX was a used only to screen spectacular documentary films that offered the sensation of flying through the Grand Canyon, diving into the ocean or being in outer space. Production of these films was rather limited. When the audience started to lose interest, Kinepolis halted its programming in 2005, just when the US market was taking its first steps towards IMAX screenings of regular releases. Christopher Nolan’s films were instrumental in the process that eventually turned IMAX into a popular “premium format.”

More or less simultaneously 3D resurfaced. The format enjoyed some popularity during the fifties (Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder comes to mind) and returned in the early eighties, blessing film history with a few horrendous films as Jaws 3D and Friday The Thirteenth – Part III 3D. The more recent revival of 3D gained impetus with the releases of animated films, notably The Polar Express (2004) and Chicken Little (2005) and was given a boost by U23D (2008). Other animated and concert films followed, but it was Avatar, with its combination of 3D with the latest state-of-the-art special effects technology, that pushed theatre owners to convert their screens to digital projection, the necessary prerequisite for add-on 3D capability. Its huge success started an evolution that promised the full potential of the 3D cinematic language would finally be explored. When Scorsese, Lee, and Godard took up experiments, it even briefly seemed this would actually be true.

In the US, although Cameron’s smash hit dictated the rapid spread of 3D technology, the format still had to face competition from the already established IMAX format. That was not the case in Belgium or the Netherlands. Kinepolis Group – the dominant chain by now – solely promoted 3D, and this position dictated the whole theatrical environment. The IMAX screen reopened in 2016, when 3D was well established as the preferred premium format. IMAX was (and is) used almost entirely for 3D screenings.

It is necessary to include another element here: the exceptionally high projection standards at Kinepolis Group. When John McTiernan came to Brussels in 1988 to launch Die Hard, he claimed that there was probably no better projection of his film to be seen anywhere in the world. Those might have been the words of an overly enthusiastic director, but they illustrate the high technical standards within Kinepolis Group. Other theatre chains were more or less forced to follow suit.

Because quality projection became the standard, any other “premium” format faced a high hurdle when it came to distinguishing itself. “Laser Ultra” already offers an exceptional viewing experience on a very large screen, so further investment had to be justified by something beyond image quality or a larger screen. 3D offered such a distinctive element and extra added value and initially did not face any competition from PLF’s. When that changed, Kinepolis kept promoting 3D, with combinations: “Laser Ultra 3D” and “4DX,” which adds vibrations to the experience.

All of the above means that 3D’s position in the Belgian environment is very different from its position in the US. Obviously Kinepolis also needs to pay the distributors, but a new deal with RealD on the use of 3D glasses consolidates Kinepolis’ position and intensifies their efforts to promote 3D. All of this means that the format will remain popular in Belgium. In this way, Kinepolis Group’s market position also dictates 3D’s standing as the preferred “premium” format in Belgium.

The Netherlands: Experiences & attractions

The Kinepolis Group is also a dominant factor in the Netherlands, which makes comparing the situation in both countries an interesting endeavour. The Netherlands’ theatrical environment has two major chains, Pathé and Kinepolis, both of them part of larger European concerns. Pathé is part of the French group ‘Les Cinémas Gaumont Pathé’ – a company that has its roots in the early days of cinema. Pathé owns 28 theatres, spread out over 20 Dutch cities. Kinepolis is a branch of the Belgian company and owns 17 theatres in the Netherlands.

With 21 theatres, “Vue Nederland” also deserves to be mentioned, although their total seating capacity is rather limited and has its main focus on smaller provincial towns.

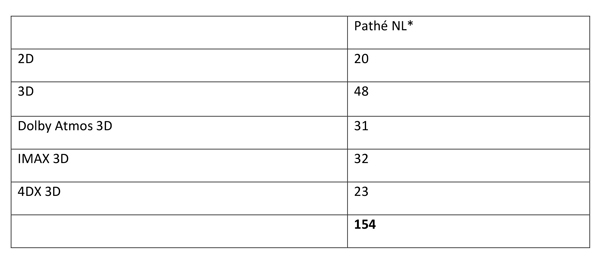

The rise of new technologies, PLFs and “extra” movie attractions such as 4DX, has lead to a situation in which standard screenings have become something of a curiosity in the multiplexes of most major cities. Almost every theatre in a major city boasts 3D, Dolby Atmos or another premium feature. Developments in sound and imagery are promoted: Pathé even distinguishes between Dolby Atmos and Dolby Cinema, with the first emphasizing immersive sound.

Six IMAX screens are spread throughout the country, although most of them would not stand up to a purist’s scrutiny: the largest one – Pathé Arnhem – measures 21×12 metres, whereas a standard IMAX screen is supposed to be at least 22x16m. The Dutch IMAX venues pale in comparison to Brussels’ enormous 27.6 x 19.3 screen.

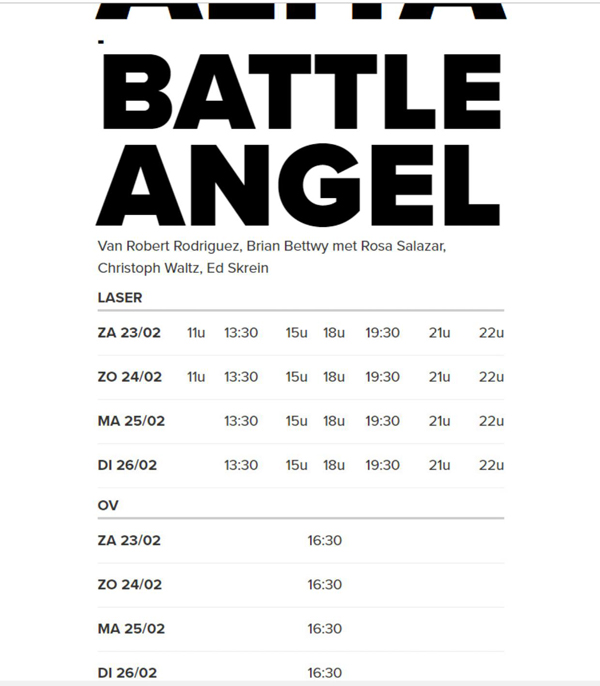

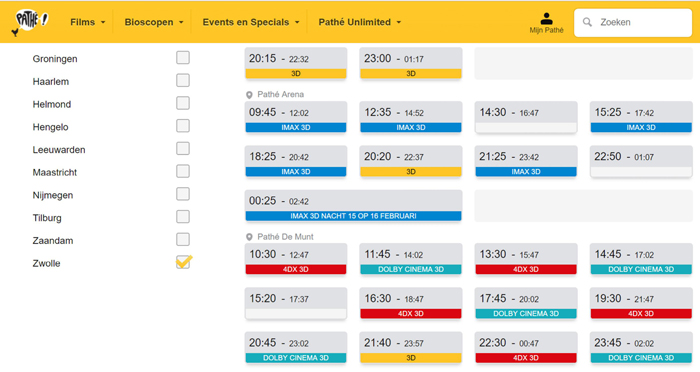

This variety of screens, systems, and venues makes it difficult to get a good grip on the partition of different formats, so once again we turned to specific Alita screenings available on February 2, 2019 :

At first glance, standard 2D and 3D screenings are balanced by premium screenings. That perception changes, when we take into account that only 5 out of 25 theatres feature 4DX, 5 offer Dolby Atmos 3D and 6 offer IMAX. That means that in some theatres it has become all but impossible to see a standard 2D screening.

The most important factor here is the fact that theatres that offer 4DX/Dolby Atmos 3D/IMAX, focus almost entirely on these formats. Those theatres are usually situated in larger cities, thus rendering it almost impossible to see a standard screening there. Amsterdam/Rotterdam (see above and below) are prime examples: out of 44 combined screenings only three of them are standard screenings. In Scheveningen, Maatsricht or Eindhoven there are no standard screenings to be found at all on the same day.

Most theatres are still located in smaller cities, and a general overview would thus suggest a rather balanced field of standard and 3D screenings. But even in those smaller venues – that do not offer the extra attractions 4DX, Dolby Atmos 3D or IMAX, the 3D screenings still outnumber standard screenings (see below)

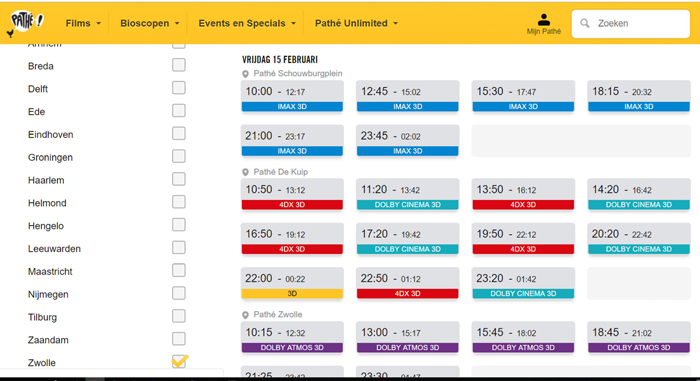

3D vs 2D in theatres without 4DX, Dolby Atmos and/orIMAX as of February 15, 2019:

With 1 out of 3/3/4 , it is clear that 3D screenings are dominant in Pathé theatres. Even daytime screenings on weekdays are 3D, which relegates standard 2D screenings to the position of a rarity.

Kinepolis’ available number of formats in the Netherlands is more limited than in Belgium. Neither IMAX nor 4DX is an option here. For Alita that results in:

The Vue chain competes with Kinepolis and Pathé in offering DX theatres that combine Dolby Atmos with superior projection technology. As in Belgium, the dominant chain sets the technical standard. A select number of theatres offers D-Box chairs that move with the action on screen. The American film critic Jeffrey Wells describes D-Box chairs as “4 DX’s less dynamic cousin.” (D-Box is Canadian in origin, while 4DX is South Korean).

Pathé, Vue and Kinepolis promote their different PLFs in exactly the same way, using “experience” and “immersion” as unique selling propositions. With 4DX the movements and effects start competing with the images for the viewer’s attention, returning the cinematic experience in a ironic way to its attraction-based origins when it was something to be experienced at fairgrounds and other shows.

In sum, the Dutch theatrical environment resembles the Belgian. A high technical standard has become the zero-line for movie screenings and 3D has penetrated the market to such an extent that it is no longer perceived as being a “premium” format, which leads to a set of various attraction-based formats that try to justify the extra cost.

At this point Dolby Atmos, Imax, and 4DX are still perceived as novelties, but it is likely that exhibitors will need additional attractions in years to come. Rising admissions for PLFs and anything “premium” suggest that visitors are constantly looking for more immersive experiences (according to the “Dutch Foundation for Film Research” in their 2018 yearly review). The number of available PLFs has significantly risen in the last few years and as long as the dominant chains continue to invest in these formats, others will follow suit. Kinepolis and Pathé set the standard, competing chains adapt.

Whether or not the public is actually asking for these technologies remains a topic open to discussion. One could claim the public merely adapts to the industries’ innovations. Still, there is no denying that PLFs turn a large profit. In Pathé Rotterdam the regular ticket price for PLF is 18 euros, while a standard screening will cost you 11 euros. Despite the cut that needs to return to the distributors, the cost for 3D glasses, and the “hardware” investments, 3D in all its forms is dominant when it comes to movie screenings in the Netherlands. The late entry of IMAX into this environment (as in Belgium and contrary to the US) meant 3D had little or no competition and consolidated its position as the preferred “premium” format.

These conclusions to come with some nuances. The Dutch part of this piece limits itself to one title and three dominant chains. Independent movie theatres were not addressed and obviously Alita: Battle Angel has some standard screenings outside of the major theatre chains. There is enough conclusive evidence, however, to support the claim that standard screenings have all but vanished in the larger cities.

A publicity image for Kinepolis, Brussels.

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Artisans and artistry

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). Production still from lost scene.

DB here:

This is the third blog entry amplifying on the paperback edition of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. This mini-series tries to enhance the book’s arguments by taking into account books and DVDs that have come out since the hardback publication in 2017. (Previous entries are here and here.) Today I want to talk about what T. S. Eliot called “tradition and the individual talent” in a realm Eliot would disdain: American studio cinema.

Curtiz, pronounced Cur-tess

Noah’s Ark (1928).

Reinventing Hollywood offers itself as an alternative to two major ways of understanding the films of a period. One angle is to see creativity flowing from gifted filmmakers. The story often concentrates on how they have to struggle against the constraints of the film industry. In the Forties, Orson Welles would be a prime instance, though Preston Sturges and others could also be invoked. Without denying the talent and originality of key filmmakers, and without neglecting the stubborn ignorance of many executives, I wanted to show that in many ways creativity can be enabled by the conditions of the industry.

Genre is an obvious instance. Without the Western, where would John Ford be? The musical brought out the gifts of Minnelli and Donen, just as the crime film spurred Huston and Anthony Mann. I wanted to suggest that filmmakers were challenged to work with other normative factors than genre—factors centering on how stories were told. Writers and directors collectively amassed a menu of narrative options, from flashbacks to voice-overs, that got quite refined in the course of a dozen years or so.

Some sympathetic readers have considered the book anti-auteurist because I emphasize those pooled resources that any filmmaker, weak or strong, could draw upon. To some extent, that’s right: stretches of the book resemble “art history without names.” Tony Rayns warned readers that they should read Reinventing Hollywood with Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide at hand.

Not a bad idea. A single paragraph compares A Child Is Born (1940), One Crowded Night (1940), Busses Roar (1942) and Dial 1119 (1950). None of them is exactly a lustrous classic, and I didn’t mention the directors or the screenwriters. My main point is that these films play out variants of the Grand Hotel plot, and they show how even artisans can take the opportunity to revamp current norms.

So for my project, creators of whatever rank matter. In the course of my research, it struck me that three “creative producers”–Hal Wallis, David O. Selznick, and Darryl F. Zanuck–are as important as many directors. The same goes for screenwriters, such as Casey Robinson, Vera Caspary, and Ben Hecht. And now that we have biographies of Victor Fleming and William Wellman, we’re starting to understand the importance of skilled directorial artisans. I’ll take even so-so craftsmen (and craftwomen) if they can teach us secrets of Hollywood carpentry. Charles Lang and Walter Lang are no Fritz Lang, but they made more popular films, and we can study the ways they instantiate filmmaking norms.

So for my project, creators of whatever rank matter. In the course of my research, it struck me that three “creative producers”–Hal Wallis, David O. Selznick, and Darryl F. Zanuck–are as important as many directors. The same goes for screenwriters, such as Casey Robinson, Vera Caspary, and Ben Hecht. And now that we have biographies of Victor Fleming and William Wellman, we’re starting to understand the importance of skilled directorial artisans. I’ll take even so-so craftsmen (and craftwomen) if they can teach us secrets of Hollywood carpentry. Charles Lang and Walter Lang are no Fritz Lang, but they made more popular films, and we can study the ways they instantiate filmmaking norms.

Then there’s Michael Curtiz.

Andrew Sarris claimed that “Curtiz reflected the strengths and weaknesses of the studio system,” and most writers have agreed. Although Curtiz is mentioned by name only twice in Reinventing Hollywood, I draw examples from ten of his films, from Four Daughters (1938) to Young Man with a Horn (1950). I devote most space to Passage to Marseille (1944). Mildred Pierce (1945) is absolutely central to the book’s arguments, but as I’ve written about it before, both in print and online, I didn’t rehash my argument in the book.

Which is to say, I guess, that Curtiz exemplifies what I was analyzing. He was a master craftsman who has a lot to teach us about norms, both inside and outside Hollywood.

Alan K. Rode’s biography, Michael Curtiz: A Life in Movies, focuses on the man and his accomplishments, and it paints a vivid portrait of a director of intense creative and sexual appetites. He also liked polo. Drawing on memos, production records, and memoirs published and unpublished, Rode provides brisk, telling background on dozens of films. He dwells, as you’d expect on the milestones: Noah’s Ark, the early 30s horror films like Dr. X, Angels with Dirty Faces, Yankee Doodle Dandy, Casablanca, and the Flynn vehicles. But he doesn’t neglect the fleet-footed programmers like The Kennel Murder Case (1933) and The Case of the Curious Bride (1935), projects enlivened with fancy angles, propulsive pace, and bold tracking shots.

On-the-set anecdotes keep things lively. Rode is careful to debunk some of the most famous stories, but he leaves a lot of good ones in. His conversational style is likewise engaging. He compares Peter Lorre to “a sinister kewpie doll” and calls Alexis Smith lissome, using a word I had forgotten exists. Although Rode isn’t as interested in the questions I pursued, his book set me thinking about creativity in the studio system. Specifically, we can broaden our view of Curtiz’s career, which ran from 1912 to 1962, and see it as encapsulating some major trends in commercial entertainment cinema, inside Hollywood and out.

Starting well before DeMille, Ford, Hitchcock, Hawks, Walsh, and other Hollywood auteurs, he was initiated into the standard tableau style of the 1910s. Fairly distant shots in long takes relied on deep sets, staging and performance. Cutting was used principally to shift the scene, show adjacent locales, or occasionally enlarge a detail. The Undesirable of 1914 (available in a stunning restoration distributed by Olive) shows fairly orthodox choreography of figures in depth and across the frame, with foreground figures masking irrelevant background action.

Apart from Lubitsch and DeMille, most of the directors who had long careers in the studio system didn’t come out of tableau cinema. They began by practicing the rapid editing and close-up framings that emerged in America in the mid-1910s. Curtiz was more or less up to speed with them in his stupendous Viennese production Sodom und Gomorrha (1922, available on a well-restored DVD version). He breaks up vast shots with axial cuts, close-ups, and occasional reverse angles. This nutty film, surely one of the biggest productions of the day, used kitschy modern sets for the contemporary story, expressionist ones (with cadaverous jailers) for dreams, and gigantic pseudohistorical ones for Biblical bacchanals.

His first American film, The Third Degree (1926), tries to bring into Hollywood some fashionable European stylization. Curtiz showcases flashy camera movements, rapid rack-focusing, swift montage, and distorted subjectivity reminiscent of French Impressionist cinema. The specific reference is Dupont’s Variety (1925). Curtiz’s tightrope shots mimic Dupont’s trapeze angles, and prismatic superimpositions of eyes during the cops’ third degree recall the swirl of the spectators’ eyes in Variety.

When a detective drops down to investigate a clue, Curtiz doesn’t hesitate to cut to a skewed view framed by the arm and leg of his crouching colleague.

Much of Noah’s Ark (1928) uses standard silent-film continuity style, although Hal Mohr’s lighting sparkles even more than in The Third Degree. Curtiz’s opening montage relies on wide-angle compositionssof a type resembling images in Murnau’s late silent pictures. Here we dissolve from Biblical worshippers of gold to modern stockbrokers, and the dense packing of figures recalls William Cameron Menzies’ work of the same period.

But Curtiz’s most flamboyant effects are reserved for the spectacle, especially in the preposterously vast flood scenes with devastation that recalls the rain of fire in Sodom und Gomorrha.

In his sound pictures Curtiz was less outré, but he never lost his taste for momentary flourishes. Anybody who starts a film called The Keyhole (1933) by moving the camera through a keyhole gets points from me.

Curtiz made his name as a master of crowd effects, and he didn’t shrink from handling groups in tight interiors. A hotel-suite party in Kid Galahad (1937) runs thirteen minutes and is packed with movement. The first shot starts on a phonograph, two abandoned drinks, and a carelessly smoldering cigarette–details indicating a wild party, and setting up the importance of serving drinks in the scene to come. Tilt up to a mirror that hints at a space we’ll soon visit.

The next shot launches a leftward track across two rooms, motivated by a damsel’s wild shimmying. People are packed into the foreground and distance. In the next room the dancing woman carries us to card players before we settle on the fight promoter played by Edward G. Robinson, who calmly gets a haircut amid all the revelry. (After all, the party has lasted three days.)

As these Kid Galahad shots show, Curtiz favored low angles and moderately wide-angle lenses to jam his figures together. In the party scene, he multiplies setups freely, almost never repeating one exactly. (Compare the slightly different framings of the second and third image.) The confrontation of two prizefight gangs is played out in a tricky mirror shot.

By comparison, W. S. Van Dyke’s handling of an apartment party in The Thin Man (1934) looks timid.

Watch Four Daughters (1938) and Four Wives (1939) to see how adroitly you can choreograph a big bunch of people strewn around a parlor. In the first film, Curtiz never lets us forget the defensive outsider Mickey (John Garfield), disturbed by this loving household and shielding himself behind the piano. Some might say that Curtiz’s use of “distant depth” is less heavy-handed than Welles’ in-your-face foregrounds in Kane, three years later.

Rode shows how Curtiz managed to control his films while shooting. From the start, in The Third Degree, he freely added scenes to the script. Thereafter, producer Hal Wallis railed at his “overshooting” with more angles than most directors would use, and he added props and actors without permission. Hawks, Hitchcock, and Ford would work uncredited on the screenplay, but Curtiz simply changed the script on the fly. As he gained more authority, he prepared new dialogue and business at night with his wife Bess Meredith.

Often over budget and schedule, constantly berated by his bosses, Curtiz got away with it all because the films were usually successful and critically acclaimed. Besides, the complaints usually came too late; he was already at work on the next movie. In some years he turned out six features. He’s a good example of a how a vigorous Hollywood artisan could leverage the system through both craft and craftiness.

Wellesapoppin’

I can’t foreswear auteurs altogether. Reinventing Hollywood does spare some time for Preston Sturges, Mankiewicz, Hitchcock, and a few others.

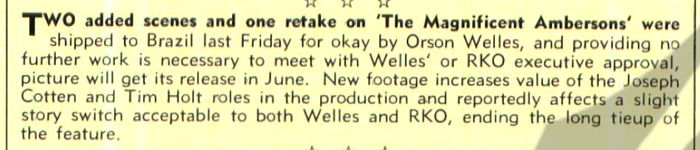

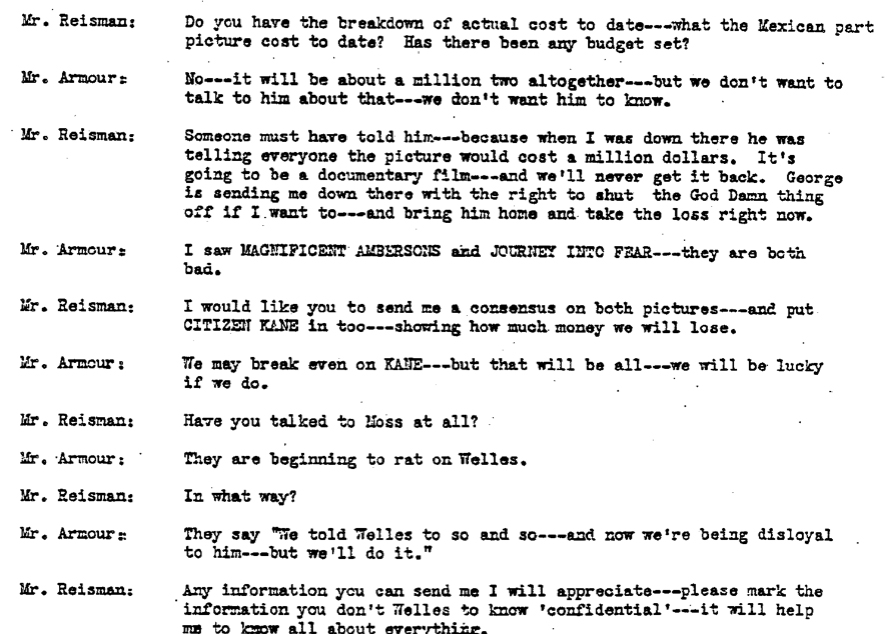

Notable among those is Orson Welles, who threads through my story. Citizen Kane helped popularize flashback narrative for A-pictures, and I argue that its use of the device blended several options that had floated around in the years just before. In the chapter on Hollywood’s efforts to interpret its own traditions, Welles and Sturges come forth as proto-film-geeks citing film history. The Magnificent Ambersons is imbued with a nostalgia for silent films. There’s the edge-vignetting on the early scenes (above), the famous iris that closes the snow idyll, the final credits showing the players more or less addressing the viewer, and the very geeky posters I illustrate in this entry and those leading up to it. The now-lost scene on the veranda with George, Aunt Fanny, and Isabel, shown at the top of today’s entry, included a vision of Lucy appearing to George “in transparency (the shadowy ghost figure from the silents).”