Archive for the 'The Frodo Franchise' Category

Frodo lives! and so do his franchises

Given the saturation of fantasy, sci-fi and superhero films we experience today, not to mention how frequently we quote from Lord Of The Rings, it bears reminding now and again (not too obsessively, mind) just what a game changer Lord Of The Rings was.

Jordan Adcock

Kristin here:

A little over ten years ago, in April 0f 2006, I finished the manuscript of The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (University of California Press, 2007). Given that I had previously written books and essays on films by such auteurs as Sergei Eisenstein, Jacques Tati, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean Renoir, and Robert Bresson, those who knew my work were perhaps bemused by this change of direction.

I had decided to tackle this project, which proved to be an enormous but richly rewarding one, in 2002, after the release of the first part of The Lord of the Rings, The Fellowship of the Ring (December, 2001). Already it was apparent to me that Peter Jackson’s adaptation would be an enormously influential film, to the point where, whether or not one likes the movie itself, it would be among the most historically important films ever made. New Line used the internet to promote it at a time when it was still not common for a film to have its own studio-created website. The cooperation between the filmmakers and the video-game designers was unprecedented. The extended-version DVD releases, arriving only five years after the introduction of the format, had unique depth and breadth. The impact of its technical innovations, particularly in digital special effects and color grading, was enormous. The film’s success boosted the many independent producers around the world who had largely financed it. Not to mention the ways in which the movie transformed New Zealand through tourism, a small but sophisticated and thriving film industry, and a surge of national pride. The film and the franchise impacted the Hollywood industry in almost any way one could imagine.

In 2002, to believe all of this was going to happen and to commit to spending time, money, and effort in researching all these topics required something of a leap of faith. It was one I was confident in making. Uncharacteristically for a historian, I made some predictions about the lasting power of LOTR and its franchise. This risk was inevitable, given that I was writing about a lengthy ongoing event, one which clearly would last far into the future. The book begins: “The Lord of the Rings film franchise is not over, not will it be for years.” [p. XIII] Later I specified:

The franchise is not nearly over. Middle-earth-themed video games continue to appear. Additional licensed toys and collectible items are still being brought out. Fan activity remains lively in cyberspace and the real world. The phenomenon has reached into international culture in ways that go far beyond the commercial confines of the franchise. Politics, education sports, and religion all reflect the influences of the film. An extinct race of tiny people discovered on a Pacific island was instantly dubbed “hobbits” by headline writers and even the scientists who discovered them. [pp. 9-10]

I was reminded of these claims by two recent events. First, last week’s Comic-Con included, as usual, a Weta Workshop booth, and, as usual, several of its popular limited-edition collectible figures from LOTR were debuted there. Second, on June 23, Jordan Adcock posted an intriguing article, “Can fantasy films escape Lord of The Rings’ shadow?” on Den of Geek. Yes, thirteen years after the release of The Return of the King (December, 2003) and ten after I ended the coverage in my book, the franchise goes on, as does the influence of Peter Jackson’s film. The number of products and tie-ins is far smaller than at the height of the films’ releases, but it seems to have settled down to a steady flow.

This combination suggested that it is an opportune time to point out that this film is still influencing the fantasy genre–perhaps too greatly–and that its franchise, though reduced, rolls on. I don’t think I was being terribly prescient in predicting all this, but it’s a bit of a relief to find out that I was right.

Collectibles, video-games, and more

Fans and collectors continue to purchase LOTR studio-licensed and fan-generated items of all sorts. Some of these are from the era of the film’s release, and some are new. A search on “Lord of the Rings” in the collectibles category on eBay generates 13,476 items, only a small percentage of which are related to products relating to the novel’s franchise or that of the 1978 Ralph Bakshi film. Some of the upscale and/or rare items sell for hundreds of dollars. There is still a demand.

In my book I made no effort to catalog all the products made to that point. In fact, I don’t think it would have been possible, unless I had had access to New Line’s records of its licensing contracts. Besides, that wasn’t part of the purpose of the book. In discussing licensed products, I was more interested in digital technology had affected what sorts of items were made. There was the motion-capture for the video games, for example. There were the DVDs–a format introduced as recently as 1997, the year when Miramax signed a contract with Saul Zaentz, thus obtaining the rights for Peter Jackson to make LOTR. (In Chapter 7 I give a little history of the introduction of DVDs and the part LOTR played in the studios efforts to move from rentals to purchases of home video.) There was the facial scanning of the actors for the action figures. There was, however, a dizzying array of hundreds, or more likely thousands of other, more conventional products licensed around the world. I once bought a lottery ticket in London not because I hoped to win a prize but because it was LOTR-themed and had a picture of Elijah Wood as Frodo on it.

Here I just want to give a few examples to show that New Line-licensed products are continuing to appear. I won’t include any Hobbit-based licensed products except in passing. Obviously the second trio of films extended the original franchise, but here I am only concerned with the longevity of the LOTR’s ability to generate more products and to influence the fantasy genre.

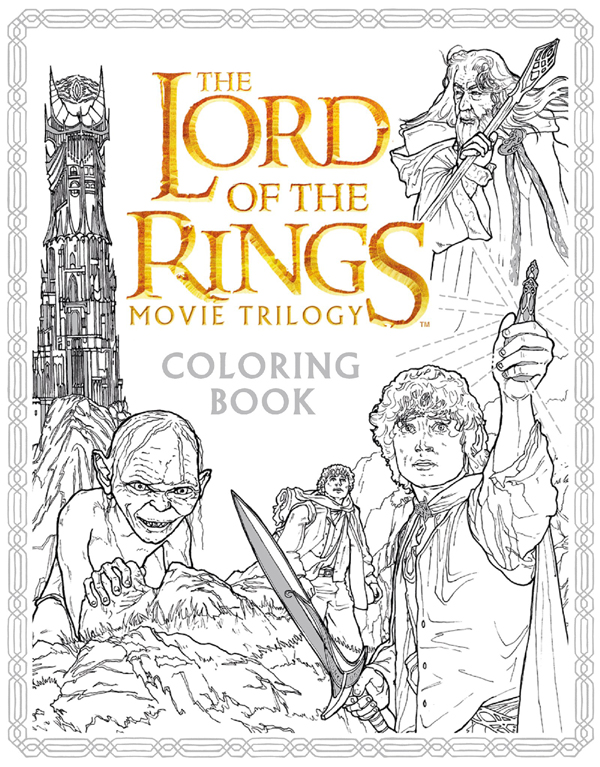

I mentioned the Weta Workshop collectible figures, which continue to be among the most popular products among devoted fans. The main fan-site, TheOneRing.net (Disclosure: I am a member of the staff) annually posts a video tour of the Weta booth at Comic-Con. This year’s video, Collecting the Precious-Weta Workshop Comic-Con 2016 Booth Tour (by TORn staffer Josh Long, about 18 minutes), lovingly moves over the glass cases containing the new items, including statues of Lurtz and Boromir enacting the latter’s death scene late in Fellowship. There’s also a big piece with the battering-ram, Grond. (I have a sentimental attachment to Grond, since it was the only one of the large miniatures made by Weta Workshop that I saw during my 2003 tour of facilities at Stone Street Studios. See above for the miniature version of the minature.) In watching the video, I didn’t keep count, but although over half of the figures are from The Hobbit, there are quite a few LOTR ones as well.

I have lost track of all the Middle-earth-based video games that have appeared since the last one the book covered: “The Battle for Middle-earth” (released on December 6, 2004, and, as far as I can tell, still in print). It was the fourth, and the first to concentrate on battles and strategies rather than on the plot of the movies themselves. By now here have been 22 of them, according to the “Middle-earth in video games” entry on Wikipedia, the most recent being “Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor” (2014). Its action takes place between that of The Hobbit and of LOTR. The total given above includes “Lego The Lord of the Rings.”

Lest one think that the only products are expensive ones aimed at the most enthusiastic core fans and dedicated gamers, I should mention that there are less pricey items. Inevitably, given the recent fad for adult coloring-books, there is one based on LOTR, list price $15.99, released May 31 of this year. (See top.) I expect a Hobbit one will follow. Warner Bros. has continued to bring out a film-based LOTR wall calendar each year. You can already pre-order the 2017 one, due out on September 15.

The posthumous career of J. R. R. Tolkien

As I pointed out in The Frodo Franchise, there has long been a franchise based around Tolkien’s original novels, which I discussed briefly. Lest we think that the film franchise must inevitably fade, it is worth noting that HarperCollins, Tolkien’s publisher, has kept the novel-based one going for decades after the author’s 1973 death.

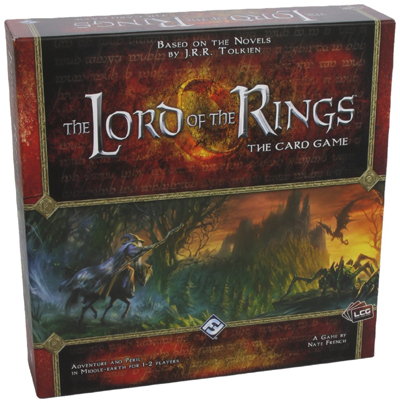

There are, for example, numerous games like “The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game” (judging from the comments on Amazon, this must have appeared in 2013). HarperCollins publishes its own calendar, based on Tolkien’s work as a whole rather than just LOTR. Many do center on LOTR, often featuring the work of a major Tolkien illustrator. With The Hobbit having been published in 1937, however, its 80th Anniversary is being featured for 2017, also available for pre-order.

The Tolkien-based franchise items tend to be somewhat more dignified than many of the film-derived ones. This is especially true given that many of the products consist of new or reissued works by Tolkien.

Non-fans of the books may not be aware that the Tolkien publishing juggernaut goes on as well. These are not all cobbled-together variants of existing Tolkien works. Actual new texts by him appear at intervals as his son Christopher Tolkien slowly releases editions of unfinished manuscripts by his father. By now Tolkien has far more literary works published posthumously than during his lifetime, even if one does not count Christopher’s epic assemblage of the drafts for LOTR in the twelve thick volumes of “The History of Middle-earth.” (Tolkien was a notorious non-finisher and left behind many incomplete academic manuscripts as well.)

Earlier this year there appeared The Story of Kullervo, retold by Tolkien from the Finnish epic The Kalevala. Amazingly, a second is due this year: The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun (out November 3). These poems, both with historical and formal analysis by notable Tolkien scholar Verlyn Fleiger, are not for the broad audience of Tolkien fans, but they obviously generate enough interest among core devotees and scholars to be worth publishing.

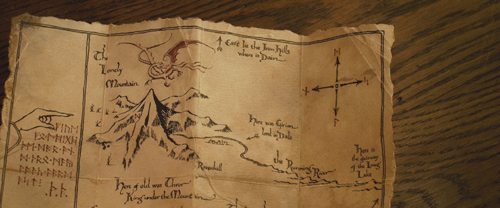

Tolkien was a talented amateur artist who occasionally illustrated his own work, most notably The Hobbit, and drew many sketches and maps to help him visualize Middle-earth. The ones for LOTR were published last October as The Art of The Lord of the Rings.

There are also, of course, as many different new editions of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings as the publishers can possibly justify in some fashion. Every now and then a “gift edition” with new illustrations appears. The one tied to the 80th anniversary of The Hobbit is a version illustrated by Jemima Catlin, announced for early next year. On September 22, the long-delayed facsimile of the first edition of The Hobbit is due to appear. (As I recall, it was originally supposed to be part of the 75th anniversary celebration.) This facsimile is of considerable interest to fans and scholars alike, since Tolkien revised portions of the original tale. Most notably, it contains a very different version of the famous riddles scene between Bilbo and Gollum, in which the Ring is introduced in a way completely incompatible with the premises concerning it established later by Tolkien in LOTR.

Even bits of film and audio recordings of Tolkien occasionally resurface. On August 6 at 8 pm London time, BBC Radio 4 will broadcast of “Tolkien: The Lost Recordings.” This program is based around some newly rediscovered audiotapes of outtakes from the BBC’s 1968 documentary, Tolkien in Oxford.

Fantastic stories and where to find them

Jordan Adcock’s “Can fantasy films escape Lord of the Rings‘ shadow?” was inspired by the release and failure of Warcraft: The Beginning. He uses the occasion both to explain why the Jackson’s LOTR trilogy so dominates conceptions of filmic fantasy and to suggest how Hollywood might make films that won’t be compared to it and inevitably found wanting.

Alcock largely credits the film’s lingering impact to the depth and plausibility of its visual rendering of Tolkien’s invented world, Middle-earth. He spends some time describing how Tolkien, with his brilliant command of history and ancient languages, managed across his lifetime to develop a consistent, appealing continent with different races, languages, countries, and landscapes, as well as its own history. Jackson’s film manages to create “a fantasy world with both digitally-aided grandeur and a practical, lived-in feel […] Jackson recreates Tolkien’s precision of time and setting.”

Certainly the film’s production design, its New Zealand locations, and its cinematography creates a Middle-earth that impressed even the film’s harshest critics. Its treatment of the plot and characters, though less successful overall, stuck far closer to the novel than did the more recent Hobbit trilogy. (See here, here, here, and here for my comments on the strengths and failures of the three parts of the latter.) Long-time fans like me forgave LOTR a lot, including added schoolboy humor and Arwen supposedly dying, for the visuals and the music and the near-perfect casting. And, as David, who has never read Tolkien, remarked to me when we walked out of theater after his first viewing of Fellowship, “Well, it’s better than Star Wars!” Within the fantasy genre, LOTR probably is the finest achievement in modern American moviemaking. It is no wonder that subsequent films, even twelve years later, are seen by critics either as pale imitations of it or as failed attempts to create a different but equally dense and coherent fantastical world.

Alcock’s hints at how filmmakers might avoid such problems, but in the process he also admits that his solutions are nearly impossible to achieve. First, he points out that the fantasy world need not be created across several decades–and yet if it isn’t, it will not measure up.

Authors and screenwriters don’t have to go away and devote the rest of their lives [to] creating a universe as large and self-sustaining as Tolkien’s, but against such a brilliant creation done such justice, all other attempts feel a little short-termist.

I assume “done such justice” refers to Jackson’s film, the implication being that the screenwriters need not necessarily invent an entire world but might find it ready-made in a literary work. The fact that the Harry Potter serial achieved such fierce fan devotion and high BO seems to confirm that. Though not an impressive stylist, J. K. Rowling shares with Tolkien a remarkable imagination when it comes to making the Wizarding World vivid to readers. She also anchors it just enough in the real world to make it appealing and easy to relate to. Her novels bear almost no resemblance to LOTR, apart from the fact that the Dementors seem derived from the Black Riders. To a considerable extent, the strongest aspects of the film adaptation’s version of Rowling’s world parallels that of LOTR, superb design and excellent casting being perhaps foremost among them.

Creating an original screenplay with a similarly original world, however, seems an extremely tall order. To be sure, it is not impossible. George Miller’s first Mad Max film was not a fantasy but an action-revenge film shot on the cheap with an unknown star-to-be. Its success, probably based on skillful direction and an appealing actor, allowed Miller to transform Max’s ordinary Australian Outback into a distinctive fantasy world, a post-apocalyptic Wasteland. This, too, was fairly low-budget, requiring little more than a desert, a bunch of eccentric, souped-up vehicles, and a team of daredevil stunt performers. Even greater success allowed the third film a big Thunderdome set, some modest special effects, and a second star. Most recently Miller gained a blockbuster-size budget for special-effects, an Oscar-winning co-star, and a multiplication of the weird vehicles. This is not to say that Miller’s created world is as complex as Middle-earth, but it has a visceral sense of reality and a distinctive look that set it apart from any other films, fantasy or not. But how often can you generate a Mad Mad-style franchise from almost nothing?

Alcock doesn’t mention it, but fairy tales have become a fallback option for Hollywood fantasy. Such films, adapting the originals into versions aimed at adults, have largely failed to catch on. (Given the recent failure of The Huntsman: Winter’s War, we might suspect that the success of Snow White and the Huntsman was due largely to the star power of Kristen Stewart, fresh off the Twilight series.) Fairy tales are sketchy stories with fantastical events and minimal characterization. They usually either take place more-or-less in our world or else spend little time describing the look of Faerie.The designers are left to their own imaginations to create settings, most of which tend to be pretty conventional.

Following in the footsteps of the LOTR and Harry Potter filmmakers, finding a novel or other literary property with the built-in popularity to carry a big-budget special-effects film seems the way to go. Despite the plethora of fantasy novels since LOTR appeared in the 1950s, choosing just the right one has proven a considerable challenge.

New Line’s adaptation of The Golden Compass, the first book in Philip Pullman’s brilliant His Dark Materials trilogy, was creditable but not exciting enough to create a successful film, let alone a franchise justifying the expense. Perhaps the novel was too little known in the US. The same could be true for The BFG, another British children’s classic, which is doing even worse at the box-office. (The studio could at least have had the sense to rename it The Big Friendly Giant, though that probably would not counteract what I suspect was the public’s mistaken impression that the film was aimed strictly at children, and very young ones at that.)

Alcock carries on his speculations.

So how does a different fantasy film emerge from the shade that Middle-earth put over all the competition? Frankly, it’d have to be another masterpiece to do it. The problem is the cohesion of vision or sincerity of intent from these other would-be franchises.

“Make a masterpiece” is excellent advice but rather difficult to follow. It doesn’t always work, either. Probably the two best mainstream American films I saw last year were Mad Max: Fury Road and Pixar’s Inside Out. Both were fantasies. Neither, as far as I know, drew any comparisons to LOTR from critics or fans, so they did escape its shadow. Both were highly praised by critics and won Oscars. They may or may not be considered masterpieces in the long run, but they certainly could count as such in the context of contemporary Hollywood. One made lots of money and may eventually spawn a sequel, given Pixar’s growing penchant for such things. The other, given its hefty budget, probably did not make a profit, or at any rate not one that Warner Bros. would consider large enough to justify taking the franchise to a fifth film–unless, perhaps, Miller went for a lower-budget project. So making a masterpiece may help distance a film from LOTR, but it does not guarantee a more practical sort of success.

On the issue of vision or sincerity mentioned above, Alcock touches on one subject that I think helps explain why it’s extremely hard to produce successful fantasies that have not the slightest whiff of Middle-earth about them. His point also explains why we seem to be stuck in a dismal summer where every week the same set of interchangeable films come out. He discusses Hollywood’s failure to follow up the LOTR with a fantasy franchise that would avoid the inevitable comparisons to LOTR.

Just think of The Golden Compass, New Line’s attempt to create a new fantasy franchise out of Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials, much more lukewarmly received and whose box office led to New Line’s end as an independent company. Now there’s food for thought–would Warner Brothers [sic], who own New Line as all but a label today, have really greenlit Lord of the Rings in its ultimate form?

I think we know that the answer to that question is almost certainly no.

In fact, LOTR actually did fail to get greenlit in its final form, though at a different major studio. As I describe in The Frodo Franchise, in 1998 Harvey Weinstein was planning to produce LOTR as a two-feature film directed by Jackson and with a budget of $140 million. When the project was a year and a half into the scripting and design process, Weinstein was called into Michael Eisner’s office at Disney, parent company of Miramax. Eisner demanded that he cut the film to one feature, made for $75 million. Jackson balked and persuaded Weinstein to put the project into turnaround for two weeks. Famously Jackson pitched it to Bob Shaye, founder and co-president of New Line, a man who knew the value of a franchise with a built-in fan base and proposed to make LOTR as three features.

Today’s New Line, a mere production unit of Warner Bros., could not undertake such a project on its own accord, and today’s Warner Bros. surely would not. With studios opting for the most established formulas, a film comparable in originality to LOTR being made, especially with all three parts shot simultaneously, would be little short of a miracle.

The only circumstance in which such things can happen would be an adaptation of a book so successful that it virtually guarantees box-office success. Warner Bros. undertook the Harry Potter series under such circumstances, given the overwhelming popularity of the book. That the resulting series of films pleased established fans and new audiences probably owes much to the fact that Rowling took an active role in consulting on the scripting and other aspects.

Today’s largely unappealing lineup of summer films (and I am writing here of mainstream Hollywood films, not including such original independent fare as James Schamus’ excellent Indignation) has been punctuated so far by two entertaining and satisfying items: The BFG and Pixar’s Finding Dorie. Both fantasies, one an undeserved box-office failure, the other a record-breaker. Which goes to show, I suppose, that good, non-LOTR-influenced fantasy (whatever its box-office record) rests with auteurs and Disney/Pixar.

Is television the answer?

Like numerous other writers, Alcock offers Game of Thrones as a model for what fantasy films with richly realized worlds might be.

If Middle-earth has a “successor,” it’s Game of Thrones. Based on George R. R. Martin’s books, the TV series has come far closer to Lord of the Rings‘ immersive world-building and cultural impact than any other fantasy, and perhaps suggests how Lord of the Rings might be adapted today.

He is far from the only writer to offer Martin’s books and the TV series based on them as an example of successful world-building. Many would say, to be sure, that the shadow of Tolkien’s and Jackson’s influence hovers over it, but perhaps that does not matter. It has brought respected long-form fantasy to TV, just as LOTR brought it to the big screen. It has gradually achieved critical acceptance, garnered a healthy number of awards, and contributed familiar tropes to modern culture, even for those unfamiliar with the books or series. I myself gave up on the novel after reading the first volume and have seen no episodes of the series. Already by the end of the first book it seemed to me that Martin was starting repeat his own devices, and if he was doing that within one book, what would later volumes be like? I certainly can’t see it as literature on a level even remotely approaching that of LOTR or even Harry Potter. I have not seen any episodes of the HBO series and hence cannot judge it. From what I can tell, it does not escape the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR, but that’s probably a matter of opinion.

Many fans who long to see an adaptation of Tolkien’s The Silmarillion have suggested that long-form television would be a more plausible medium than theatrical film. I consider The Silmarillion utterly unfilmable, except possibly in the hands of a brilliant animator, but that’s another issue. The point is that television, and especially powerful cable channels like HBO, are seen as the venue for long films that would be unlikely to be greenlit as high-budget theatrical features.

Despite appearances, I am not a keen fan of fantasy literature and films. The only fantasy novels (apart from children’s books) I have enjoyed enough to reread are LOTR, the Harry Potter series, and Susannah Clarke’s Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. The seven-part TV series based on the latter ended its American run on BBC 2 just over a year ago. I believe it is somewhat parallel to the LOTR film in being a reasonably successful–artistically at least–adaptation of a major work of literature It also bears no trace of Tolkien’s influence.

How does it escape? If you asked someone who had read both Martin’s books and Clarke’s whether they had read Tolkien, he or she would probably guess that Martin had and would have no idea whether or not Clarke had.

Martin admits his debt to Tolkien freely. “I revere Lord of the Rings, I reread it every few years, it had an enormous effect on me as a kid. In some sense, when I started this saga I was replying to Tolkien, but even more to his modern imitators.”

Clarke also was a Tolkien fan, but I have never seen anyone compare JS&MN to LOTR, either the original novel or the TV series. For one thing, she had other, quite different influences well, as described in a reader’s guide on her publisher’s website.

During an illness that required her to rest a great deal, Clarke re-read Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, and when she finished she decided to try writing a novel of magic and fantasy. She had long admired the fantasy writing of Ursula Le Guin and Alan Garner, but also loved the historical fiction of Rosemary Sutcliff and novels of Jane Austen. These various influences were to come together in a novel which is part magical fantasy, part scrupulously researched historical novel, with teasing faux-academic footnotes referencing a bibliography of magical books entirely of her own invention.

Clarke also has a literary skill that elevates her above most writers in the genre. Her approach was not to invent an imaginary world à la Middle-earth, but to begin by setting her story in the actual English history of the Regency era. Into that she inserted two magicians seeking to revive the tradition of Faerie-derived English magic and use it to aid their country during the wars with Napoleonic France. Her seamless blend of real historical figures and events with her own inventions can leave many nonspecialist readers wondering which is which.

I have already written about the TV adaptation of Clarke’s book, pointing out both what I consider some problems with the adaptation of the narrative and some real strengths of the series. As with LOTR, the adaptation’s strengths have much to do with the design, the special effects, and the acting. Indeed,the series won two BAFTA TV Craft awards, for production design (above, designer David Roger accepts his award) and special effects. In some ways, it could have been to TV what LOTR was to film, though it was far less successful with audiences and thus will no doubt have concomitantly less influence.

The elusive “masterpieces” of fantasy that Adcock suspects might escape from the shadow of Jackson’s LOTR could be either films or TV series. But unless the studios greenlight more imaginative fare, that shadow will persist for a long time.

On the point about whether Warner Bros. would greenlight a LOTR trio of films today. I discuss studio executives’ decisions about which fantasy films to make, specifically in relation to Warner Bros. and Jack the Giant Slayer, in “Jack and the Bean-counters.” In my 1999 book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood, I suggested that Hollywood’s originality and risk-taking had declined so much, even by then, that many classic and successful films could not be greenlit; I suggested Witness, Chinatown, The Fugitive, and Alien as fairly recent examples. By now the system has become even more exclusionary.

The idea that series TV offers the advantage of more time to play out the narrative of a long book is not true in all cases. Including credits, JS&MN runs a total of 406 minutes, while LOTR runs 558 minutes in its theatrical edition and an extra two hours in the extended home-video release. (In the 50th Anniversary edition, Tolkien’s novel runs 1029 pages without the appendices. The first edition of JS&MN is 782 pages.) Ironically, in the wake of LOT’s success, New Line optioned JS&MN as a possible successor to Jackson’s film. The Golden Compass took precedence, and eventually JS&MN became available for the BBC to adapt. Made as a trilogy, with a higher budget, it would have looked great on the big screen.

Wildstyle, Gandalf, and Batman in The Lego Movie (2014)

A Hobbit is chubby, but is he pleasingly plump?

Kristin here:

Some readers have been kind enough to ask if I would be writing a wrap-up entry on The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies now that the entire set of Peter Jackson’s films have appeared, including the extended edition of the last part. I was somewhat hesitant to do so. Five Armies is my least favorite among the six parts, and I have many fond associations with researching and writing about the Lord of the Rings films for The Frodo Franchise book and blog. Still, it makes sense to follow up on my previous comments on the strengths and weaknesses of the two earlier parts of the HOB trilogy and suggest how they continued on into this concluding chapter.

I have previously blogged three times about The Hobbit at intervals since just before the release of the first part. In September of 2012, I posted “A Hobbit is chubby, but is he padded?” In it I discussed the July 30 announcement that the film would be released in three parts rather than the originally announced two. I expressed cautious optimism, suggesting that there was enough material in the original novel plus the appendices of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings to create a film reasonably faithful to the original.

In mid-January of 2013, I posted a follow-up entry, “A Hobbit chubby, but is he off-balance?” The first part of the film, An Unexpected Journey, had been out for about a month, and I felt the additions mostly worked well, or at least were acceptable. I still think the first part is the best.

Almost exactly a year later, I added a third entry, based on the release of The Desolation of Smaug: “Is Tauriel more powerful than Eowyn? and other questions we shouldn’t have to ask.” By this point I felt that the project had considerably strayed in directions that betrayed Tolkien’s source material. As the title implies, I felt that the modest “prequel” film had also begun to swell inordinately and threatened to overshadow the fine trilogy that the filmmakers had made earlier.

These problems are even more evident in the final installment.

Marvelous moments

To be sure, there are some impressive shots and scenes in the final film. In the opening sequence of Five Armies, Smaug’s flights over the town and his confrontation with Bard are the most impressive parts of the scene, and the dragon’s death is appropriately enough its high point, both literally and figuratively. The overhead shot of his lifeless body drifting downward, seen against the inferno that he has created, is one of the best of the film (see top). It recalls the marvelous shot of him at the end of Desolation, emerging from Erebor covered in the coating of molten gold that the Dwarves had hoped would kill him and rising into the sky as he effortlessly shakes it off.

Some of the later shots in Erebor are wonderful as well. (See the image at the bottom.)

The climactic confrontation between Thorin and Azog on the frozen lake has been widely praised. It’s a complete invention of the filmmakers; there is nothing like it in the novel. It contains many lovely shots which, I must say, provide a welcome change from the crowded battle scenes. The lake is introduced as Kili and Fili creep along its edge, hoping to reach the summit of Ravenhill, where Azog had been located as he commands the battle. (See top of this section.)

The confrontation itself contains many impressive compositions, both as the two competitors circle each other and later as Thorin, mortally wounded, watches the Eagles swooping as Azog’s corpse lies in the foreground.

Surely one of the film’s best scenes is the one where Thorin, driven nearly mad by his obsession with the treasure, wanders on the solid-gold floor left behind by the failed attempt to kill Smaug by flooding him with molten gold. We see him wander over the floor as a hallucinatory vision of Smaug slithers through the gold below him (left). Finally Thorin imagines himself sinking into the gold 9Right), an overhead shot that echoes the one of Smaug’s death at the top of this entry.

Another very different high point is Bilbo’s arrival back at Bag End only to find himself presumed dead and an auction of his effects going on. No doubt fans were looking forward to seeing this scene from the book, and it delivers considerable humor as well as poignancy once Bilbo gets inside his nearly empty house and replaces the portraits of his parents on their hooks.

Gaps and missed opportunities

Some things that one would expect to see in the film are simply not there. In the opening framing scene in Unexpected Journey, the elderly Bilbo remarks that the little trunk in which he has stored the treasured objects from his adventure still “smells of troll.” In Unexpected Journey we see the Dwarves bury treasure in trunks, so that it may be collected later. In Five Armies, we see Bilbo carrying his trunk on his journey as he nears home. Yet we never see him and Gandalf return to the scene of the encounter with the trolls and dig up the treasure. In the book, they do so and agree to divide the loot. Why bother to place such emphasis on the trunk and show Bilbo taking it home with him if the story does not include him retrieving it on the way back to Bag End? We last saw the trolls’ trunks two films ago, and surely at least a mention of their retrieval would remind those unfamiliar with the book where Bilbo got this rather large piece of luggage. Surely at least in the extended version a minute or so could have been spared from the overextended battle scene.

As to gaps, the big battle at Dol Guldur ends with Saruman telling Elrond to take the weakened Galadriel back to Lothlorien and “Leave Sauron to me!”

This is one the largest dangling causes in the film, and yet it never comes to anything. In between the Hobbit and LOTR films, Saruman seems to have come under Sauron’s sway, but there is no indication as to how that might have happened. Causes that dangle need to be taken up and explained.

More generally, fans have complained that Bilbo often seems to be missing from his own story.

The original novel is told almost entirely from Bilbo’s point of view. There are only a few scenes where he is not present, and his personality gives the book considerable unity of narrative tone. In Martin Freeman, the filmmakers found the perfect actor to portray him. It is a pity that Bilbo has to cede so much of his screen time to Azog and Bolg and Alfrid and even Tauriel, pleasant though she is in some ways.

The expanded edition

As with all five other parts of this serial, Five Armies was released in an extended version. This added 20 minutes, as compared with 13 minutes for An Unexpected Journey and 25 for The Desolation of Smaug. (For a list of which scenes were extended or added to all three parts, see here.) In the two previous parts, the additions were mainly more conversations and characterization. In Desolation, for example, the brief scene of Gandalf, Bilbo, and the Dwarves visiting Beorn were significantly expanded. In Five Armies, however, much of the extra footage expanded the already lengthy battle scene. There are some pluses and minuses in this new material.

Fans of the book were particularly annoyed by the elimination of the funeral of Thorin, Kili, and Fili, and a short but touching scene of the Dwarves and Bilbo grieving over their bodies was restored. This scene establishes that the Arkenstone, the cause of so much strife, has been returned to Thorin and will rest on his body, thus wrapping up the question of what ultimately happened to it.

A few additions provided explanations for plot points, as when Gandalf visits Radagast’s home after being rescued from Dol Guldur and receives Radagast’s staff to replace his own–thus confirming fans’ speculations about where he got the new one. (See above.)

Whence came the giant rams on which Thorin, Kili, Fili, and Dwalin ride up Ravenhill? Now we learn that they were the mounts of part of Dain’s Dwarf army.

By the way, I’m puzzled by the Hobbit film’s the obsession with using odd animals for transportation: Thranduil’s elk, Dain’s hog, other Dwarves’ rams, and Radagast’s bunny sled. The only one that comes from the book is the habit of orcs riding wolves and wargs, though we do know from LOTR that Dwarves don’t like riding horses–but Elves certainly do.

The one quiet conversation that was added has Bilbo talking with Bofur (in a track entitled “The Night Watch”). Bofur strongly hints that Bilbo would be justified if he simply slipped out and returned home before the battle starts, but Bilbo assures him he’s not leaving.

I suppose it’s a nice little reversal in the scene in Unexpected Journey when Bilbo does try to slip out of the cave in which the group are sleeping and go home. There Bofur spots him and kindly wishes him well. He is one of the few Dwarves that Bilbo seems especially to befriend, but it doesn’t really add much. In fact, about half of the Dwarves have been relegated to barely speaking. Some seem to have no audible lines, and some are barely glimpsed. It’s a considerable change from the earlier parts, where the writers took care to give each of them bits of business or dialogue.

One Dwarf’s role is considerably filled out from his relatively brief role in the theatrical edition. Dain Ironfoot, Thorin’s hog-riding cousin, now has considerable dialogue and swings a mighty war-hammer in battle. He is a much more comic character than in the book, which is unfortunate in that it makes him seem an inappropriate figure to replace the serious, majestic Thorin as King under the Mountain.

His salty language, though relatively mild as profanity (calling his foes bastards and buggers), is out of keeping with the language in the rest of the series. There is also some unintended humor as Dain and Thorin are able to pause in the midst of a crowded and chaotic battle to greet each other, exchange pleasantries, and discuss strategy, with the melee conveniently receding to provide them a little safety zone. Their discussion does help us a bit in understanding what is now an even more scattered, confusing battle scene.

Finally, we find out in this longer version how the comic villain Alfrid met his well-deserved end. Attempting to flee with some gold coins he has discovered, he hides on a catapult and inadvertently sends himself hurtling into the mouth of a large troll.

Alfrid, who does not exist in the novel, was a tolerable figure while the characters were still in Laketown and he could interact with the Master. Bringing him safely ashore and making him part of the actions of the citizens as they take refuge in the ruins of Dale, however, was in my opinion a big mistake. Without any justification, he becomes a sort of assistant to Bard. Fans widely expressed mystification as to why Bard and even Gandalf would give him important duties to perform when both should know that he is completely unreliable, foolish, dishonest, and selfish. In general he injects a humor that undercuts the serious nature of many of the scenes. He, like the Master, should have been left to go down with the ship back in Laketown.

Increased violence

Throughout the LOTR and Hobbit series, the filmmakers have pushed the limits of the rating system, always achieving a hard PG-13 label for both the theatrical and extended versions. With Five Armies, they have for the first time crossed the limit and been given an R rating, though only for the extended edition.

I see this as something of a betrayal of the fans, especially families, who have fallen in love with this franchise, sharing the films over many years. The reason for the R rating is probably entirely due to some extreme violence and cruelty. Certainly there is no sexual basis for such a rating, and the mild profanity mentioned above, introduced with the character of Thorin’s cousin Dain seems unlikely to have been a significant cause of the stricter rating.

One particularly disturbing figure is a troll who figures prominently in the battle. He has apparently had all four limbs systematically amputated and replaced with prostheses in the form of giant metal weapons. Moreover, he is controlled by a rider who guides him with reins made of large chains attached to his blinded eye sockets with hooks. While most of the trolls who serve the enemy’s troops seem to do so more-or-less willingly, this one does so through sheer torture. This is all the more disturbing because at one point Bofur manages to gain control of this troll and delightedly uses him as a weapon in the same fashion, directing him with the reins and hooks.

Apart from such scenes, there are numerous new moments where decapitations and amputations are copiously meted out, often in humorous fashion. In one scene Thranduil’s battle elk scoops up eight or so orcs, and the Elven King beheads them all with a single sweep of his sword.

The chariot drawn by large rams has blades sticking out from the hubs of its wheels, and these provide the opportunity for much carnage, as when one cuts off a large orc’s legs and it staggers about on the stumps of his thighs or when a row of trolls are rapidly decapitated as the the chariot bounces past them.

I watch and write about movies for a living and have been exposed to a great deal of cinematic violence, but such scenes as these seem particularly out of place to me in a series aimed at an audience intended to include young people.

More echoes of LOTR

In the third entry, I discussed what I consider a serious problem with The Hobbit: the tendency to copy so many elements from LOTR.

Most crucially, I think, instead of using these already established characters in Desolation or just sticking more closely to the book, the filmmakers have introduced many new elements that are essentially diminished versions of characters and events in LOTR. That strikes me as a bad idea and perhaps really does betray a lack of inspiration. Already fans of the LOTR films have complained that so many echoes of LOTR appear in Desolation. Worse is to come, though. When people view LOTR as part of a series of six parts beginning with The Hobbit, they will end up seeing things in LOTR as echoes of Desolation. The result will be to rob LOTR of some of its originality and effectiveness.

Take Tauriel. She’s a pleasant, admirable character, with a stubborn, headstrong streak that keeps her from being bland. Evangeline Lilly’s performance strikes me as excellent. A lot of fans worried about her inclusion in the film but came to like her. They seem to see her as blending well into the world of the film. But there’s a reason for that. She does come from the world of LOTR.

Was it really a good idea to add a major character who’s basically a blend of Arwen and Eowyn? Doesn’t she make both of those characters less distinctive?

Similar things happen in Five Armies. Bombur blows a big horn outside Erebor during the Battle, just had Gimli had done to signal the big charge out of Helm’s Deep in The Two Towers (in a more impressive composition).

Yes, one takes place in daytime and is seen in low angle, the other at dawn and from above, but still.

Or take the appearance of the Eagles, which in both films drift out of the bright clouds in the background, their leader carrying a wizard. (Radagast does not appear at all in the book, let alone as part of the battle.)

The berserker troll that butts his head into the protective wall at Dale recalls the similar Uruk Hai with a torch who dived into a drain tunnel at Helm’s Deep, sacrificing himself to set off an explosive and create a similar entryway for the attacking army of orcs.

In addition, there’s the scene of the arming of the men and boys in Dale echoing the one in Helm’s Deep. Or Dale in flames, see from above and looking very like Minas Tirith in a similar situation.

I wish I could give the filmmakers the benefit of the doubt and say that these echoes are attempts to create motifs that would knit the two films into a single, unified tale. That’s not the effect of them, however. Aren’t these just repetitions without any real connections? Why would things so often happen in the same way? Doesn’t it distract from the drama at hand to keep thinking back to when we’ve seen something like this before? Wouldn’t we’d rather be seeing something new and original?

There should instead be more echoes like the one mentioned above, between the death of Smaug above a lake of fire and the scene where Thorin’s hallucinations are staged on a similarly glowing golden floor. That’s the way to create a rich narrative, and that comparison resembles nothing in LOTR–except perhaps the shot of Gollum, also seen from above, falling into the pit of lava. Whether or not the similarity of the two shots in Five Armies were intended to echo the Gollum one, it’s a reasonable comparison to make.

I haven’t yet tried the experiment of watching all six parts straight through, The Hobbit and then LOTR, to see how they work as a complete serial. More than ever I fear that the result will be to diminish LOTR, which is clearly the better of the two by a long way.

Basically I do not think that many of The Hobbit‘s problems result from the splitting of the adaptation into three rather than two parts. Done in service to the original book, it could have worked. Rather, those problems stem from a fundamental mistake made by the filmmakers.

They decided to adapt The Hobbit into an adult story with the same sorts of somber moments and terrors that LOTR contains. I basically agreed with that decision in a previous entry, saying this was now Peter’s Hobbit. But given how far he took all this–with the overextended battles, the urge to interject grotesque humor into serious situations, and the extra characters who turn Bilbo into a supporting player in his own tale–I believe he should have done what Tolkien did: let the two books (or films) be different. Let one be aimed at children—less violent, simpler, more humor—and the other be aimed at adults.

So what if the two aren’t consistent with each other? Generations have read Tolkien’s two novels and noticed that they are essentially in different genres and simply accepted that. The problem has been compounded by the fact that so much that happens in The Hobbit is copied so closely from LOTR. Now that we have every bit of the second trilogy, I’m afraid I must conclude that yes, this Hobbit is chubby but also off-balance and padded.

My “A Hobbit is chubby” phrase refers to the fact that Tolkien’s Hobbits are all to some degree chubby. This is not the case with three of the four main Hobbits in LOTR, nor is it true of Bilbo. Still, given the controversy over the added length of the film adaptation, it was impossible to resist the reference.

Although much has been made of the idea that the two trilogies are the same length, in that they are three parts each, it’s worth pointing out that the extended version of The Hobbit (8 hours 52 minutes) totals an hour and a half shorter than that of The Lord of the Rings (11 hours 22 minutes). Over such a span it may not seem like much, but it’s the equivalent of a shortish feature film.

A hobbit is chubby, but is he off-balance?

Kristin here–

I first read J. R. R. Tolkien’s work during what might be described as the second generation’s discovery of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The Hobbit was very popular from its initial publication in 1937, enough so that the publisher asked for a sequel. Though Tolkien wanted LOTR to come out in a single volume, postwar austerity dictated that it be divided into three separate volumes. After their publication in 1954-55, a devoted following grew. The real explosion, however, came in 1965, when the Ballantine paperback editions appeared in the USA.

I was fifteen at the time and already an aficionado of Victorian literature (H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle). I was used to reading long books (David Copperfield, Don Quixote). Like so many other people who were in high school or college in the 1960s, I loved Tolkien from the start. Eventually I became an academic writer. At some point, I decided to write a book on the two Hobbit novels.

I had done a lot of reading and note-taking for that project by the time of the release of Peter Jackson’s film version, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. With reservations, I liked that film. What fascinated me more, though, was the incredible success of the innovative marketing and merchandising side of the LOTR franchise. I decided this film was going to be historically significant in a major way. In 2002, I decided to write a book about it.

The Tolkien study was put way back behind even the back burner. The franchise book needed to be written now, when I could (I hoped) get access to the filmmakers and to information that would not be available after the last part was released. With enormous good luck and help from many interviewees, I managed to write The Frodo Franchise (2007). My Tolkien project came forward onto the stove and is now in progress.

I’ve kept up my interest in the films, though. Editors have asked me to write short pieces on Jackson’s LOTR, and I’ve done four of those so far. I maintained my Frodo Franchise blog until it became apparent that I would not be granted access to the filmmakers for a book on The Hobbit. Now I’m on the staff of TheOneRing.net, for which I write occasionally. Naturally I’ve kept up on the progress of Jackson’s new trilogy.

Not long ago in these pages, I wrote about the fact that The Hobbit had been expanded from its originally announced two parts to a three-part film. To those who accused the filmmakers of doing this for strictly mercenary purposes, I countered that there were reasons why such an expansion could work well. Mainly these relate to the extra material in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, which provide information on two kinds of events: those taking place during the time period when The Hobbit’s action unfolds (most importantly an attack on Sauron’s [aka the Necromancer] lesser dark tower Dol Guldur) and those which took place in the past but which relate to characters and actions in the novel (e.g., Smaug’s attack on Erebor and Dale, the Dwarves Pyrrhic victory over the troops of the Orc Azog at Moria).

Having now seen The Hobbit three times, I want to suggest how successfully, if at all, the filmmakers have incorporated this material. For the most part the non-Hobbit material has been brought in well, or in some cases acceptably.

It’s a prequel now

One objection to the division of The Hobbit into three parts is that the book won’t support a narrative nearly as long as that of the filmed LOTR. Over and over, fans and critics have complained that Peter Jackson’s adaptation of The Hobbit (1937) isn’t designed as Tolkien wrote it, as a children’s story, lighter in tone and shorter than LOTR. They often also object to those who refer to it as a “prequel.” The novel’s events took place years before those of LOTR. It was also published first, appearing in 1937, while LOTR came out in three volumes published in 1954-55. The implication is that Jackson should just have ignored the other film and stuck strictly to the novel, which is about a quarter the length of the LOTR tome. As literature, LOTR is a sequel to The Hobbit.

But the films are different. Even if The Hobbit were adapted page by page, speech by speech exactly as written, those of us who have seen the LOTR film or read the book could not see it as a separate tale. We know already what the Ring is and what eventually happened to it, while readers, if they started with The Hobbit, do not. We know that Elrond is a powerful leader among other powerful Elf leaders, destined eventually to leave Middle-earth for the Undying Lands. We know Gandalf is a wizard who will guide the various peoples through the War of the Ring. And so on. Only viewers who see The Hobbit without having seen LOTR first or having read the book or having read any of the extensive media coverage of both could come to the prequel unaware of such things. And while the novel The Hobbit is not a prequel, the film adaptation certainly is.

Because most of us do know about these major characters and premises, Jackson and his team could hardly avoid trying to make the new film match his version of LOTR. He had to treat events, characters, tone, and setting with some consistency, and he had to link the films as one long account of historical events in the same era of Middle-earth.

Tolkien himself tried to smooth out the disparities between The Hobbit and LOTR, both in tone and causal connections. He revised The Hobbit slightly in 1947, mainly to make the Riddles in the Dark scene work better in the light of what the Ring eventually became when he brought it back as a more crucial plot element in LOTR. In 1951, those revisions got into the second edition of The Hobbit and have remained canonical ever since. In 1960 Tolkien was again disturbed by the differences between the two books and launched into a more thoroughgoing revision of The Hobbit to make it conform exactly to the later events in LOTR. Others convinced him that this was a mistake and that it damaged the charm of the earlier book, already a classic of children’s literature. Eventually he allowed those disparities to remain. He did, however, write passages in the appendices that at least briefly described events that helped stitch the two books’ narratives together.

I don’t see that it’s a problem for the filmmakers to use those passages to try and make their films flow more smoothly from the first to the second. In a few years we will be able to watch all six parts of what will then essentially be a single narrative with a sixty-year gap in the middle. For better or worse, depending on one’s opinion, this is Jackson’s Hobbit. Unlike Tolkien, he is making it after already having made LOTR. He can include the links between the two tales, as well as extra plot material that Tolkien published in the 1950s but hadn’t conceived in the 1930s. The question is not whether those links and that material should have been included but whether they have been well handled.

In terms of the links, many of the ones in An Unexpected Journey seem effective. The notion of starting The Hobbit at a point just before Gandalf’s arrival for Bilbo’s 111th birthday party seems a good one: we see Frodo nailing up the “No Admittance” sign from the early LOTR scene and then heading off to read in the woods and await the wizard (above). There’s an immediate recognition factor. The younger Bilbo mentions Bree, a locale seen in LOTR, and he recalls Gandalf’s fireworks from his youth. A fireworks display also figures in Bilbo’s birthday party scene in LOTR. Bilbo’s initial awe upon arriving in Rivendell and his reluctance to leave it tie in with the fact that he goes to live there after leaving The Shire early in LOTR. Certainly the inclusion of Balin, made into a more prominent character than he is in the novel and played with considerable humor and charm by Ken Stott, should make the discovery of his tomb in LOTR a more meaningful and poignant scene. On the whole, the stitching together of the two films so far is quite accomplished, and I assume it will continue to be so through the other two parts.

But is it padded?

Most of these links between The Hobbit and LOTR are brief references or gestures, made in passing. They are not the reason that Jackson’s team decided, to considerable critical and fan uproar, to make The Hobbit in three parts rather than the originally announced two. In the earlier entry, I suggested that there was material in the appendices of LOTR that fills in information relevant to The Hobbit’s plot.

There’s the backstory of the Dwarves, involving two major events. Bilbo’s exposition at the beginning establishes their great kingdom within Erebor (the Lonely Mountain). Its king, Thror (Thorin Oakenshield’s grandfather), oversees the accumulation of a huge horde of gold and gems, and it attracts the dragon Smaug. Smaug’s destruction of the Dwarves’ home and the neighboring city of Men, Dale (portrayed briefly in a sort of Renaissance Italian style), leads to the Dwarves’ exile and hereditary king Thorin’s eventual decision to try and retake Erebor.

Second, there is the great battle fought between the Dwarves and Orcs at Moria, in which Thror is killed and Thorin earns the respect of his people by defeating the great Orc leader, Azog—chopping off his arm and leaving him, as Thorin wrongly assumes, to die.

All of this the film explains in flashbacks derived from the LOTR appendices, and this embedded material seems to me to come off well. In my opinion, most of the other scraps of text used as the inspiration for scenes not in the original Hobbit novel results in reasonably successful scenes—with one major exception, which I will deal with in the next section.

The most important extra plotline concerns the White Council (not so named in the first part of the film). Initially I speculated that the White Council scene would be a flashback to an early meeting. That’s not the case, since Gandalf meets with Elrond, Galadriel, and Saruman during the visit to Rivendell (above). In the novel, when Bilbo and Gandalf revisit Rivendell on their way back to The Shire, the Hobbit simply overhears Gandalf talking to Elrond: “It appeared that Gandalf had been to a great council of the white wizards, masters of lore and good magic; and that they had at last driven the Necromancer from his dark hold in the south of Mirkwood.”

Here, by the way, is an example of the sort of inconsistent plot points that Tolkien presumably hoped to eliminate when he struggled to revise The Hobbit in the early 1960s. By then he had written LOTR and given the Wizards their emblematic colors, so Saruman (and later Gandalf) was the only “White” wizard. The “Necromancer” would become Sauron; the “dark hold in the south of Mirkwood” gained a name, Dol Guldur. What Jackson and the other writers have done is to move that meeting of white wizards (which took place somewhere to the south, presumably either in Lothlórien and Orthanc) to Rivendell. That simplifies things.

Now the question remains, to what degree does the White Council hint that Saruman has already become treacherous? Is he dismissing Gandalf’s worries as exaggerated merely because he’s conservative and just doesn’t much respect the Grey Wizard, or is he secretly searching for the Ring himself (as Tolkien revealed in the appendices)? I hope these questions will be explored further in one or both of the upcoming parts.

Interestingly, Gandalf is already visibly frustrated by Saruman’s presence at Rivendell, and the two are at odds about the degree of danger evidenced at Dol Guldur. Saruman favors inaction, meaning that he opposes the Quest of Erebor. Gandalf sees all sorts of ramifications in the presence of the dragon and the odd goings-on at Dol Guldur. Obviously we know Gandalf is right, especially since Galadriel sides with him from the start. The explicit representation of this action within The Hobbit’s plot is, I think, off to an excellent start. I look forward to seeing how it develops.

Gandalf’s seems to regard Saruman with a mixture of frustration, annoyance, and forced friendliness and deference. How will this attitude affect our perception of Gandalf’s words about Saruman when he prepares to go and consult the White Wizard in The Fellowship of the Ring? There, as Frodo prepares to take the Ring and head to Bree, Gandalf says, “I must see the head of my order. He is both wise and powerful. Trust me, Frodo, he’ll know what to do.” In retrospect, Ian McKellen’s reading of these lines in Fellowship works in remarkably well with Gandalf’s attitude toward Saruman in the White Council scene in The Hobbit. He speaks the first two sentences quickly, without inflection, as if reciting them; we could interpret them as arising from a sense of duty rather than hope that Saruman really can or will help. The “Trust me, Frodo” sentence is accompanied by a tight smile, perhaps the sort of forced smile that Gandalf assumes as he turns to greet Saruman in the White Council scene. Given that neither director nor actor was presumably looking forward to someday adding such a scene, they turned out to be lucky that Gandalf’s speech was delivered in such a way that it could imply a lurking dislike or distrust of Saruman. (There is evidence for such distrust in the novel. In his long conversation with Frodo about the Ring, Gandalf remarks “I might perhaps have consulted Saruman the White, but something always held me back …. His knowledge is deep, but his pride has grown with it, and he takes ill any meddling.”)

One admirable thing about the Rivendell sequence is that the friendships among Elrond, Galadriel, and Gandalf are portrayed. In the book, these three have known each other for two thousand years. They are the bearers of the Three Elven Rings. Those who know only the film of LOTR are unlikely to be aware of that, since only in the penultimate scene at the Grey Havens are the three openly wearing their Rings—barely noticeable even on the big screen. Oddly, however, the licensed tie-in products for LOTR included replicas of Narya, Nenya, and Vilya, made by the Noble Collection. The three characters are able to communicate telepathically. Elrond, portrayed as rather aloof in LOTR, is a warmer figure here, embracing and teasing Gandalf, and the scene after the White Council meeting in which Galadriel reassures Gandalf and offers him her help is one of the most genuinely moving moments in the film (see top). (We never saw Galadriel and Gandalf together in the LOTR film, though they are together in some of the late book chapters that were cut in the adaptation.)

Radagast the Fool

Then there’s Radagast. The Brown Wizard appears in one scene in the novel version of LOTR, but Jackson and company eliminated him. Radagast is only mentioned in The Hobbit, but now he appears in two extended scenes and presumably will return in the later parts. Many fans object to Radagast’s being made into a comic figure, driving a sled pulled by large rabbits and hosting birds in his hair, with a resulting streak of droppings down the side of his head. Never mind that in Radagast’s one scene in LOTR, Tolkien portrays him as faintly comic, as well as timid and ineffectual. While pumping up the humorous side of the Brown Wizard, Jackson develops him into a character with considerably more gumption.

It has also been claimed that his role in the drama isn’t significant enough to warrant his presence. Did we really need all this time devoted to someone who’s there mainly to give Gandalf the Morgul blade as evidence of foul goings-on at the seemingly deserted Dol Guldur? Yet the dialogue does help motivate his importance. Gandalf declares to Bilbo, “He keeps a watchful eye over the vast forest lands to the east, and a good thing, too, for always evil will look to find a foothold in this world.” That dialogue hook leads to the first scene with Radagast, walking through the forest and finding death and decay, evidence of a mysterious force that he traces to Dol Guldur.

And the blade brought to Gandalf is definitely a significant object. When Gandalf presents it to the Council, Galadriel is very perturbed by it, and Elrond loses his initial certainty that Middle-earth is at peace. By the end of the scene, only Saruman denies the need to investigate what’s going on at Dol Guldur. Gandalf’s visit to Dol Guldur and the White Council’s subsequent actions in relation to the Necromancer’s presence there will form a crucial subplot in the upcoming parts; we’ve already glimpsed part of Gandalf’s exploration of the stronghold in the trailers.

Radagast also serves to draw the Orc band away from the Dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf. He drives his infamous bunny sled across the rolling hills, allowing the group time to find the hidden entry into Rivendell. But is the bunny sled so very ridiculous? Teanna Byerts, aka swordwhale, a member of the Message Boards at TheOneRing.net, has written an informative and amusing essay, “Radagast’s Racing Rhosgobel Rabbits: A Recreational Musher Looks at the Realities of Bunny Sledding.” It turns out that a sled would not be a bad vehicle for a woodland environment, and, allowing for the fact that this is a fantasy film, large rabbits not entirely implausible beasts for pulling them. (A Google Image search on “large rabbit” brings up some bunnies about the size of Radagast’s–and no, they’re not all Photoshopped.) The main problem is that ordinary rabbits would not pull as a team, but as Radagast says with relish, “These are Rhosgobel Rabbits!”

Although there is probably too much silliness relating to Radagast, on balance I think that he is a plus for the film and shouldn’t be dismissed as mere padding. Tolkien’s novels suggest that Radagast is a member of the White Council, one of the “white wizards” Gandalf met with down south. He lives in southern Mirkwood at Rhosgobel, a short way north of Dol Guldur. As Gandalf’s speech quoted above (not in the book) indicates, despite Radagast’s hermit-like ways and fascination with nature, he keeps an eye on things in the area. He also seems to maintain a system of bird messengers and spies for the use of the White Council. (In the novel he, not some passing moth, is responsible for the eagle Gwaihir appearing at Orthanc to rescue Gandalf.) Though Radagast never visits Dol Guldur in the book, he generally does the sorts of things that he does in the film. Although he perhaps contributes little in the first part of the film, we should withhold judgment on his importance to the plot until we see what he does in the second and perhaps the third.

The chase of the Orcs after Radagast’s sled, by the way, exemplifies one of the several lapses of causal motivation in the film. Why do the Orcs try to catch Radagast? They are specifically after Thorin, and the Orcs have no way of knowing that Radagast has any connection to the Dwarves. If they take off after every passing stranger when they are supposed to pursue a specific mission, these Orcs make very poor hunters. And while we’re on the subject, how does Radagast get all the way from southern Mirkwood, which is on the far side of the Misty Mountains, and find Gandalf so quickly?

A final note on Radagast. For those of us who were lucky enough to see Sylvestor McCoy play the Fool to Ian McKellen’s Lear during the stage tour, there is a bit of added resonance in their scene together.

Unjolly giants

The scene of the stone-giants has been criticized as well. They occupy four minutes of screen time, putting the Dwarves and Bilbo in extreme danger without having any real link to the plot. The scene’s only causal function is to give Thorin another opportunity to belittle Bilbo. The episode derives from a few brief remarks in the middle of the novel’s description of a terrible thunderstorm the group encounters in the high mountain pass:

When he [Bilbo] peeped out in the lightening-flashes, he saw that across the valley the stone-giants were out, and were hurling rocks at one another for a game, and catching them, and tossing them down into the darkness, where they smashed among the trees far below, or splintered into little bits with a bang …. They could hear the giants guffawing and shouting all over the mountainsides.

Douglas Anderson has suggested that by “stone-giants” Tolkien meant a particular type of troll; he mentions the “Stone-trolls of the Westlands” in Appendix F. (See the second edition of The Annotated Hobbit, p. 104.) If so, they would probably only be a little larger than the three trolls in the earlier forest scene. But whatever they are, they are clearly not fighting but playing a game. Moreover, the Dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf (who does not stay behind in Rivendell in the novel) are inside a cave when all this happens. Jackson could have chosen to leave out such a brief references, but he instead turns the creatures into immense giants made of stone, and they are having a flat-out battle rather than a game. I don’t think this was part of an effort to stretch the film into three parts but results from Jackson’s tendency to add or extend action scenes.

Finally, the film considerably lengthens the Goblin-town episode and includes a great deal more combat. In the book, Gandalf quickly kills the Great Goblin and leads the Dwarves and Bilbo in a race for the entrance, with a couple of skirmishes with small groups of Goblins. Again, I don’t think the expansion was created in order to necessitate a third part to the film. This scene had almost certainly been planned and shot well before the decision to ask Warner Bros. for permission to add a third part. Extending the scene is another instance of Jackson’s penchant for big action sequences, and especially battles. I find it a bit overlong myself, but many fans probably like it.

Azog the Defiler of Plots

There is, however, a plotline that does seem to me to be padding. The placement of scenes involving its action damages the narrative rhythm of the film as a whole. The plotline centers around Azog the Defiler, the “Pale Orc” whom Thorin grievously wounded in the battle at Moria (below) and who turns out not to be dead. Instead, he and his band of Orcs, bent on revenge and mounted on wargs (giant wolves) are hunting for Thorin. Making room for this line of action evidently led the filmmakers to cut other scenes that I, and undoubtedly some others, would have preferred to see.

Critics have pointed out a pattern of rescues and respites in both The Hobbit and LOTR. At fairly regular intervals, the characters get into dangerous situations and are rescued, often by someone completely unexpected and even unknown. They then spend a peaceful time with their rescuers before going on to the next challenge. This pattern is so consistent and evident that Ursula K. Le Guin termed it the “rocking-horse gait” of the books.

Obvious examples of down-time are the interludes in Rivendell in both books and the stay in Lothlórien in LOTR. These aren’t dull stretches. They’re occasions for introducing new characters, giving exposition, and bringing a new population with a distinctive culture into the mix of peoples uniting to battle evil. They’re about character development and revelation. They’re about showing off the beauties and wonders that make Middle-earth such an attractive, fully realized fantasy world. And between the battles and chases, they give us, as well as the characters, a bit of respite. This rescue pattern is one of the most basic structures of both of Tolkien’s novels. (I’ve devoted a chapter about it for my book-in-progress.)

The Azog plotline throws off the rescue/respite pattern (which Jackson’s team respected more consistently in LOTR). Worse, it tips the dramaturgical balance of the whole film. First there is the ten-minute troll battle, and then a pause while the group explores the cave. That moment of quiet action lasts only four minutes, and then Radagast shows up. I take this to be the beginning of the next scene of fear and danger, since the Brown Wizard agitatedly launches into a tale about his visit to Dol Guldur, presented as a flashback full of menace and threat. Almost as soon as he finishes, the chase begins. The Radagast scene to the point where the Dwarves’ group hides and Elrond’s Elves drive the Orcs away lasts 9:39 minutes, roughly the same length of time as the trolls scene.

The big Azog battle, in which the Defiler shows up in person and Thorin at last realizes that he’s alive, similarly comes very soon after the end of the huge Goblin-town battle and the concurrent Riddles in the Dark scene. The Goblins/Gollum action lasts 28:37. Once it ends, there’s an all-too-brief scene while the Dwarves and Gandalf think Bilbo has lost or has deserted the group, only for him to show up and explain why he has decided to stay with them (2:53).

Then Azog and his band arrive. The rather straightforward scene in the book, with ordinary Goblins and wolves trapping the company in some fir trees (not on the edge of a cliff), becomes a full-blown battle with Thorin nearly killed and Bilbo prematurely summoning up his submerged courage to save him (11:00). After three viewings, my basic response when the final forest confrontation with Azog begins is, Oh, not again! We’ve just had nearly half an hour of suspense and violence, with considerable variety and impressive filmmaking. The Goblin/Gollum scene should be the high point of the film. To have a shorter battle immediately after it makes the Azog fighting suffer by comparison while undercutting our memory of the earlier, longer one. I don’t think the Azog scenes in general add anything except brute action. Yes, they give Thorin a new revenge motive, but it kicks in only at the end of the film, and he already has plenty of dark motives with his hatred of Smaug and the Elves, particularly Thranduil. Far better to have stuck to Tolkien’s simpler version, ending the film with the group treed by generic Goblins and wolves and then get to the eagles’ rescue as quickly as possible.

The decision to end part 1 by moving away from the group and following a thrush to the Lonely Mountain is, I think, one of the more inspired additions to the story. As the thrush cracks a snail, the sound seemingly carries through the rock and into the cavernous interior, where we see a close view of Smaug’s eye emerging from a great heap of gold and popping open. Smaug is a great villain, unlike Azog, and I suspect his first conversation with Bilbo will be the equal of the Riddles in the Dark scene.

The Azog plotline also introduces a massive coincidence. Just after Balin has told the group the tale of the Moria battle and Gandalf and Balin have exchanged glances suggesting that they do not assume Azog is dead, there’s a cut to Azog’s Orcs appearing and discovering the group. We don’t know how long it has been since the Moria battle, but has this group of hunters been combing Middle-earth for Thorin ever since, while Azog cools his heels at Weathertop waiting for them to report to him? Possibly some sort of motivation for this will be supplied in part 2, but it’s really not a good idea to leave such a flagrant coincidence unexplained within this part.

Doing the numbers

Some have complained about the slow beginning of the film, which, apart from the early flashback to the kingdom of Erebor and city of Dale and their destruction by Smaug, takes place entirely in and around Bilbo’s home, Bag End. As has been endlessly pointed out, Bilbo’s race down the Hill to catch up to the Dwarves starts fully thirty-nine minutes into the film (not counting the open series of logos). To those interested in character and plot–and faithfulness to Tolkien’s book–this makes perfect sense. To those just waiting for the big action scenes, it’s frustrating. But the long exposition has to accomplish something that never challenged Tolkien: differentiating thirteen Dwarves. In the novel, only a few members of the group get any significant amount of characterization, and they mostly remain shadowy background figures whom we don’t have to visualize as individuals. But in a film they’re all there on the screen, and Jackson has to at least give them distinctive appearances. He goes further and assigns them traits, however simple, and on the whole does a good job of it.

To me, apart from the overly coarse behavior of the Dwarves (does Kili really have to be so boorish as to scrape his muddy boots on Bilbo’s furniture?), this early part of the film consists mostly of entertaining, lovely stuff. Kudos to Jackson’s team for keeping not one but both Dwarf songs, which nicely display the contrast of comedy and determination that underlies the group’s nature. The contract-reading scene and Gandalf’s attempts to persuade Bilbo to join the Dwarves’ quest are both entertaining and nicely revealing of Bilbo’s character. I particularly like the quiet conversation between Thorin and Balin, with Balin trying to talk Thorin out of the quest and Thorin revealing his reasons for confidence and hope. (In some ways, this makes little sense, given that it is Balin who later rashly sets out to try to retake Moria and ends up getting himself and his colony of Dwarves killed, but at this point it’s a minor matter.)

Again, though, there’s a problem of balance. So much of this fascinating material is crammed into the opening, and so much of the rest of the film is taken up with dangerous action scenes. It’s notable that the Goblins/Gollum sequence and the final Azog battle add up to 39:37, almost exactly the same length as the opening of the film up to Bilbo’s departure from home. The string of action scenes that begin with the trolls proceeds with only brief letups. A major exception is the Rivendell interlude, with the crucial White Council scene.