Archive for September 2011

A memory palace

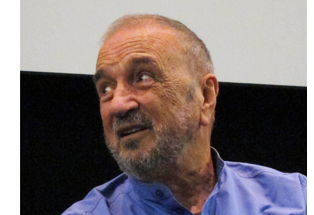

Roger Ebert in a moment of seriousness at Ebertfest 2006.

DB here:

Life Itself is not an ordinary memoir. True, it’s roughly chronological, taking you from Roger’s childhood through college to journalist days and then to the career we all more or less know. But from the start, we may find several moments, decades apart, squeezed into a single paragraph, even a single line. An incident in the past triggers a flashforward, an account of what became of this person, why this place became one to revisit. Later in the book, layers of flashbacks stack up. And usually the passage slips still further outward to the enveloping narrative, recounted by a man who now finds pleasure in the very act of recollection.

A trip to London in the mid-1960s, during which Roger and his old friend Dan Curley discover The Perfect London Walk, summons up an episode, years later, in which their guidebook of the same name is clutched in the hands of tourists whose paths cross with Roger and Chaz’s. Then we’re with Roger in a hospital bed years later as he revisits London in his mind, with details rising unbidden. He sees a nursery school and the shadow of a wooden palm tree in a window. And then we glide outward to another frame, the very moment of writing that conjures up all the others. “I believe that I could pause right now and remember something I saw on a walk that I have never thought of again since that time.” That moment yields another cascade of memories, ending in the 1970s with Roger crawling through a hotel window in order to look down on Pembridge Square.

Gifted with a preternatural memory, Roger shames most memoirists. Not for him the procession of big names and picturesque places that makes the usual autobiography little more than a prosed-up agenda book. The book crackles with sensory impressions: the taste of a ploughman’s lunch in a pub, the whiff of a Steak and Shake cheeseburger. The world is there to be known, in all its teeming variety. I remember talking with him after George W. Bush got elected, and he was appalled that our new President had not held a passport before being elected governor. “Can you imagine a young man being that incurious?”

Gifted with a preternatural memory, Roger shames most memoirists. Not for him the procession of big names and picturesque places that makes the usual autobiography little more than a prosed-up agenda book. The book crackles with sensory impressions: the taste of a ploughman’s lunch in a pub, the whiff of a Steak and Shake cheeseburger. The world is there to be known, in all its teeming variety. I remember talking with him after George W. Bush got elected, and he was appalled that our new President had not held a passport before being elected governor. “Can you imagine a young man being that incurious?”

Above all, Roger’s curiosity turns toward people. Vast though his appetites and energies are, and frank as he is about his faults and failures, the writer is most fascinated by a picaresque procession of extraordinary individuals, most not famous. Yes, there are portraits of Mitchum and Scorsese and Royko and other larger-than-life celebs, but they’re brought down to earth. He favors the unknowns. He has, like his beloved Dickens, a genuine interest in everybody. After telling a bit about Letterman and Leno, he really gets going on the civilians whom he and Siskel met doing man-on-the-street gags. Studs Terkel becomes a fatherly exemplar of this worldly curiosity about the absolute uniqueness of everybody. “Two people meeting with Studs standing between them would hear from him how extraordinary they both were.”

Roger’s cast consists of everyone who has provided him laughter, sober self-analysis, affection, passion, and a long-running, tuition-free course in being a good person. For Sartre’s character, Hell is other people. Ebert, I’d say, thinks that other people are a decent, secular definition of Heaven. Life Itself radiates respect for the stubborn, sometimes maddening uniqueness of human beings.

“I was born inside the movie of my life,” the book begins. Okay, but what kind of movie? As a bona fide film brat, Roger has given us the autobiographical equivalent of a 1960s off-Hollywood art picture. It recalls those exercises in broken chronology like Petulia, but it’s gentler: not grating cuts, but quick dissolves. The time frames keep shifting and flipping over. Far along, at something like the climax of the book, love affairs and alcoholism set off a spiral of associations around his mother. And each era is quickened by the observer’s awareness of the preciousness of the sensuous moment. Roger is writing and watching teenage Roger dancing with Marty McCloy to the Everly Brothers in the Tigers’ Den:

Under our armpits, sweat formed dark circles, and our cheeks were moist as they touched.

Cinematic though it is, Life Itself is a literary exercise too. Roger, perhaps our most bookish living film critic, provides a montage of styles and genres. The childhood scenes, echoing Portrait of the Artist and A Death in the Family and perhaps The Sound and the Fury, are bursts of bright, disconnected impressions. Things coalesce into anecdotes as the boy’s mind matures. (Is it just me who hears echoes of another Midwestern yarn-spinner, Jean Shepherd?) In the young man who yearns to travel, to explore every city, to read every book he can lay his hands on, to shyly move toward girls, we see Thomas Wolfe, teenage Roger’s guiding star. Soon enough, though, we’re in a Ben Hecht Chicago newsroom:

Once Paul was talking on a telephone headset, tilted back in his chair, and fell to the floor and kept on talking. Eppie [Ann Landers] reached in a file drawer and handed down her pamphlet Drinking Problem? Take This Test of Twenty Questions.

(Aspiring writers: Compose a 50-word paragraph explaining why “handed down” is a better choice than “handed him.”)

Every memoir needs a credo, and this we get in concluding chapters entitled, “How I Believe in God” and “Go Gently.” They give you much to chew over, including laconic bon mots like “I was perfectly content before I was born, and I think of death as the same state.” The lesson of this life? Expect no spoilers from a fellow critic, but I can provide a teaser. It has to do with joy.

Graven image and original: Ebertfest 2006.

The big oh-five

Us on Easter Island, 2006, soon after starting Observations on Film Art.

DB here:

This blog began on 26 September 2006. Today’s entry is number 450. I reckon that we’ve dumped at least 600,000 words into the maw of the Net. Add in many web essays and two full-length books (one a reprint, the other a revision), and you get an object lesson in something, probably obsession. Scribble, scribble, scribble….

The figures that make us proud, however, have to do with you. Since it launched, the site has attracted over 3.5 million visits from nearly 2.5 million readers (or computers; or IP addresses; or cookies; or some such virtual entities). Nearly half a million of those readers/ avatars have visited more than once. These numbers are, we suspect, fairly modest ones compared with other film websites. But for writers whose books have print runs of 2500, they’re cause for surprise and gratitude.

Looking back, we see we’ve learned a lot. Our first entries lacked pictures because I didn’t know how to enter them. Some of the earliest entries with pictures aren’t very well laid-out; chalk that up to my apprentice fumblings with Photoshop. Gradually, we got better at integrating texts and images, and this year we’ve started to add video clips, sparingly. In the beginning we wrote several times a week, but now we aim at only four to six a month. As readers haven’t been shy to point out, our entries have gotten rather long. It’s just to make up for less frequent posting, I tell myself and anyone who’ll listen.

There are continuities as well. The very first entry talks about how flashbacks make a difference in cinematic storytelling–a topic that continues to preoccupy me. Soon enough I was off to the Vancouver International Film Festival, an event that Kristin and I will be attending again this week. Our first month on the job led to entries on mobile cinema, an academic conference, an important film and director (Sátántangó by Tarr, earning two entries), a recent US hit (The Departed), and current trends in the American film industry. All of these matters have woven through our last five years.

An enterprise undertaken by two mild-mannered academics (okay, at least Kristin is mild-mannered) has brought us closer to old friends and introduced us to new ones. We’re thankful that so many people have kindly linked our entries and brought us readers. We’re even more grateful for getting to know Jim Emerson, Matt Zoller Seitz, Catherine Grant, Kevin Lee, Grady Hendrix, David Poland, Susan Doll, Daniel Kasman, and many of the other writers who have shown, in a wide variety of styles, what serious film thought can be in this new medium. We also thank Manohla Dargis, who introduced our blog to the New York Times readership, and Tim Smith, guest author of an entry that still draws intense interest. Roger Ebert, pioneer of Web criticism, has been a stalwart supporter, generously steering his loyal readers to our site.

The Web’s churn sometimes grinds up ideas and pulverizes thought. These people and their peers preserve the ideal of lively, acute conversation about movies. They also exemplify an openness to ideas that many academics would do well to imitate.

We’re happy as well that the blog has enabled us to call attention to DVD publishers like the Criterion Collection, Masters of Cinema, Flicker Alley, and Kino Lorber. These firms play irreplaceable roles in film culture, trusting that some viewers want to have their horizons expanded. We admire the pluck of the people behind these enterprises and we’ll continue to help get the word out about their collections.

Speaking of film culture, we’re lucky to live in a milieu rich in movie lore and movie love. Our department and our immediate colleagues keep us alert and teach us all manner of things. Our archive, run by the indefatigible Maxine Fleckner-Ducey, puts thousands of films and hundreds of thousands of documents within easy reach. Our tech support is unparalleled, thanks to Erik Gunneson and Mike King and Peter Sengstock, who has recently taken our website under his wing. This morning, with no hesitation Pete righteously smote Bangladeshi hackers who had infected our site.

We can stay reasonably plugged in to the international film scene thanks to our venues on campus, such as the Cinematheque run by the dazzling Jim Healy and the new Union South cinema, the Marquee, programmed by students and Tom Yoshikami. We benefit as well from good sites off campus, such as our Sundance miniplex and our Museum of Contemporary Art. Guests come through too; just last week we had lunch with the estimable and hilarious Second City alum Betty Thomas. Our blog tsarina Meg Hamel has as her day job directing the Wisconsin Film Festival. Meg, now the mother of a seven-week-old charmer named Hazel, has been with us from the start. Every entry we compose is in debt to her.

For some people the Web is an endless dorm-room conversation. For others it’s a speed-dating session. For us, children of the postwar print age, it’s a great big magazine rack. A blog lets us be our own editors and publishers, freeing us of length limits and giving us as many stills as we want. (And in color.) We don’t include comments because we don’t the time to monitor them. Maybe we’re just stuck in Web 1.5. But we do answer nearly everybody who writes to us, and we sometimes tack those responses onto our entries. Call it our version of letters to the editor. And these correspondents almost always make corrections and suggest nuances that are worth considering.

We have no intention of stopping. Illness, travel, and other writing projects have slowed us in the last few months, and a looming deadline will limit our output a little up to December. But there are two entries on the shelf, one coming soon, the other, a windy one, later this week. After those we’ll be reporting as usual from Vancouver. Unlike Bob and Doug McKenzie, we’re not at a loss for topics. For at least five more years, we’ll try to interest you in what we’re thinking.

Some vintage items

Kristin and I have compiled a handful of early entries that never became readers’ favorites and didn’t make their way into the Minding Movies collection but that we harbor warm feelings toward.

One entry that was originally supposed to go into Minding Movies but which had to be cut for reasons of length is “Cavalcanti + Ealing = a little-known gem.” It discusses Cavalcanti’s 1942 classic Went the Day Well? When we posted this entry in May of 2008, it was hard to obtain a DVD of this moving tale depicting an imaginary Nazi invasion of a bucolic English village. Now you can order a manufactured-on-demand DVD-R version from Amazon, but if you have a multi-standard player, you’re probably better off getting the brand new Optimum restoration from Amazon.uk, on DVD and Blu-ray (KT).

In this very early entry, some readers didn’t like my criticizing George Stevens’ direction in Giant, and I admit it wasn’t very deft. And the stills are too small. But I think my analysis of the shootout in PTU stands up. This sequence should be studied by young filmmakers, as well as by those critics still talking about the decline of craft in Hollywood action cinema. More generally, I’ve written a lot on Hong Kong film that I couldn’t fit into Planet Hong Kong 2.0. (Copies still available; a great holiday gift.) I’m unreasonably vain about writing seven longish entries in the week of its release; the one-man blogathon starts here (DB)

“Happy birthday, classical cinema!” was posted in December of 2007, to mark the 90th anniversary of the year when, as most historians agree, the classical Hollywood model of creating movies gelled. We don’t follow the bloggy tradition of posting ten-best lists each year, but we thought instead we might as well post the ten best of 1917. Of course, many silent films do not survive, but we thought such a list might be a handy guide for those seeking to explore the early era of filmmaking. The 90-year-old ten-best lists became an annual tradition on “Observations.” Watch for the 1921 entry in December (KT).

Some entries use so many stills that book publication would be onerous. One of my favorites is my appreciation of Shimizu Hiroshi. Our discussions of Japanese cinema don’t attract as many readers as they should. After all, we are talking about one of the three greatest national cinemas.(I leave it to you to imagine the other two.) Modest Shimizu can break your heart. Since I wrote this, the admirable Criterion has brought out a fine sampler (DB).

With Steven Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin coming out in a few months, it might be interesting to look at “Reflections in a crystal eye,” a joint entry on Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (or IJatKotCS, as we like to think of it). We weren’t terribly keen on the film, but there are other Spielberg movies we like a lot better. We point to some characteristic tropes (KT).

In these days of worry about piracy, it’s nice to recall an era BD (Before Digital), when piracy was simpler, and even more nourishing to film culture (DB).

Betty Thomas visits UW–Madison and dines at Dotty Dumpling’s.

Scriptography

Hollywood screenwriters at work, according to Boy Meets Girl (1938).

It’s not every conference that opens a morning session by asking the men in the audience to take off their underwear.

But I anticipate.

Last weekend I was a guest of the Screenwriting Resource Network’s fourth annual Screenwriting Research Conference in Brussels. I think that a hell of a time was had by all, and I learned quite a bit, including some reasons why people are interested in screenplays.

Schmucks with Underwoods

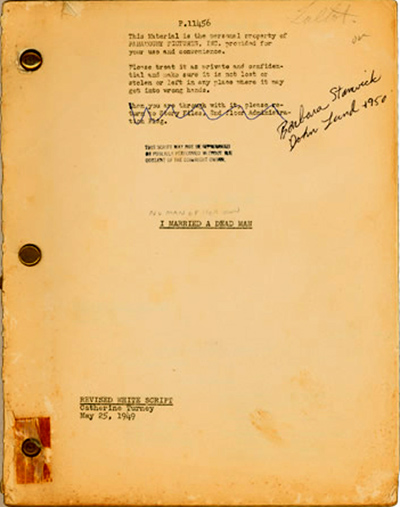

Catherine Turney script for No Man of Her Own (1950).

In my youth, there seemed to be a solemn pact among my peers that we would never study certain areas: censorship, audiences, adaptation (novels into film, particularly), and screenwriting. An earlier generation had, through patient labor, shown decisively that these subjects were dead boring. We, on the other hand, were fired by notions of the director as auteur, and indifferent to what were called “literary” and “sociological” approaches to film. So we triumphantly turned toward The Text—that is, the finished movie.

Things have changed since then. Yet there are still tempting reasons to consider the study of screenwriting a nonstarter if you’re interested in cinema as an art. If you think of the finished film as the achieved artwork, then study of screenplay drafts risks seeming irrelevant. Whatever the screenwriter(s) intended seems irrelevant to the result. So what if six or more screenwriters labored over Tootsie? The movie stands or falls by what we see onscreen.

This was the view presented in Jean-Claude Carrière’s three talks to our group. He suggested that the screenplay is destined to become landfill, and rightly so. It’s like the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly. Once the film has been made, the script has no intrinsic value.

Someone might say, “Wait! We study a painter’s sketches, a novelist’s drafts, or a composer’s early scores. These materials can contribute to understanding the finished work, and sometimes they have an artistic value of their own.” The problem is that in these arts, the preparatory materials are in the same medium as the result. But a script can’t count as a version of the film because prose can’t adequately specify the audiovisual texture of a movie. It’s commonly thought, plausibly, that giving the same script to two directors would result in significantly different films. So the script is at best a series of suggestions for filming, not a sketchy version of the movie. Why not discard it when the film is done?

The study of screenwriting has probably also lain in the shadows because of the proliferation of screenwriting gurus and how-to manuals. Every American over the age of eighteen seems to be writing a screenplay; the Cable Guy who visited me last week was working on two. So all the seminars and advice books have arguably put thinking about screenplays rather close to the amateur-script racket.

Moreover, screenplay studies seem to be part of a broader, paradoxical development in academic film studies. Today scholars have more access to films than ever before, thanks to video, festivals, archives, and the internet. Yet many researchers prefer to talk about everything but the film. More and more scholars want to study just those subjects that my cohort considered dull or irrelevant: censorship and regulation, audiences (composition, demographics, critical reception, fandom), and preproduction factors (storyboards, scripts). In addition, many academics have turned to bigger thematic ideas like film and architecture, film and the city, film and modernity. These trends of research usually make only glancing reference to actual movies, mostly mining them for quick illustrative examples.

In sum, many academics have abandoned the study of film as an artistic medium that finds its embodiment in important works. To get to know particular films more intimately, you increasingly have to go to the Net, to writers like Jim Emerson, Adrian Martin, and other sensitive analytical critics. Talking about screenwriting can seem to be another way of avoiding coming to grips with the intrinsic power of movies.

You can probably tell that one side of me shares some of the biases I’ve listed. But when I remind myself that what people should study aren’t topics but questions, I cheer up quite a bit. For there are, I think, worthwhile questions to be asked about all these areas, screenwriting included. The Brussels event gave some good instances of resourceful, occasionally exciting research into them.

Based on my short acquaintance, most of the research questions seem trained on one of two broad areas: Screenwriting and The Screenplay.

In the trenches

Kinky & Cosy

Screenwriting can be thought of as a practice, a creative activity with both personal and social aspects. How, we might ask, do screenwriters or directors express themselves in the script? How does a media industry recruit, sustain, and reward screenwriters? What are the conventions and constraints at work in a particular screenwriting community?

Questions like this are somewhat familiar to me. When I wrote my first book, on Carl Dreyer, I had to examine his scripts (notably the unproduced Jesus of Nazareth), and that helped me understand his characteristic methods of researching and planning his films. Later, when I collaborated with Kristin and Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I recognized a more institutional side of things. We can see from the films of the 1910s that filmmakers were cutting up the space in fresh ways. But this wasn’t a matter of directors simply winging it on the set. Kristin used published manuals and Janet used original screenplays to show that shot breakdowns were planned to a considerable degree before shooting. This habit made production more efficient and controllable.

At the Brussels get-together, Steven Price offered further evidence of this sort, which displayed some of his research on early scenarios for Mack Sennett movies like Crooked to the End (1915). Interestingly, Steven found that sometimes the later version of a continuity script was more laconic than the initial one. Perhaps the gags, once spelled out in the first draft, could be left up to the actors. This is the sort of thing he identified as a “trace” of production practices.

A parallel of sorts emerged in Maria Belodubrovskaya’s paper on screenwriting under Stalin. The Soviets, admiring Hollywood efficiency, tried to come up with a similar system. But their efforts to produce films in bulk were blocked by a censorship apparatus bent on ideological correctness. No surprise there, I guess. But Masha showed convincingly that the very efforts to mimic Hollywood’s “assembly-line” system also discouraged authors from submitting scripts. The writers thought (like many of their LA counterparts) that such a setup denied them creative freedom. In addition, the prospect of story departments providing a stream of screenplays ran afoul of the tradition that gave the director control of the final draft. And the role of producer, as one who could steer the whole process, didn’t exist! So much for the Soviet Hollywood.

What about other media? Sara Zanatta traced out the process of creating Italian TV series. She reviewed some major formats (miniseries, original series, adaptations of foreign series) and then took us through the process of creating individual episodes. Interestingly, it seems that the Italian system, unlike US television, makes the director the boss of it all. Frédéric Zeimat explained how he gained entry to the local screenwriting community through his university education, including work in Luc Dardennes’ workshop at the Free University of Brussels. Eventually he came up with a script that won prizes. He is about to become a showrunner for a sitcom.

One of the most stimulating panels I heard considered the writing of graphic novels and animation. Richard Neupert explored how recent French animation sustained the tradition of individual authorship while still acceding to some international norms of moviemaking. The cartoonist Nix discussed how he faced new problems in transferring his three-panel comic strip Kinky & Cosy from print to television. TV demanded less written text, especially signs, so that the clips could be exported outside Belgium. More deeply, Nix had to rethink how to pace the action and leave a beat (say, two seconds) after the punchline.

Pascal Lefèvre, one of Europe’s leading experts on comic art, provided a brisk, packed account of the history and practices of scriptwriting for Eurocomics. He described patterns of collaboration, format, and creative choice, placing special emphasis on comics as a spatial art different from cinema. His example was a page from Regis Franc’s ulta-widescreen album Le Café de la plage. Here’s a portion in which two periods of Monroe Stress’s life coexist in a single space. He muses as an adult while his childish self gobbles up food under the guidance of Mom.

Comics space can also change abruptly, as when a window appears in second panel.

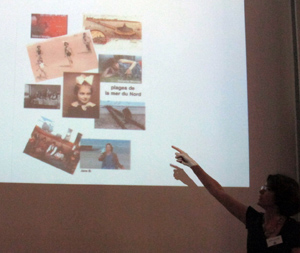

Other papers presented less institutionally fixed, more personal versions of screenwriting as a practice. Kelley Conway’s lecture on Agnes Varda exploited unique access to the filmmaker’s notebooks, scrapbooks, and databases. Kelley showed how Varda conceived three of her documentaries by means of strict categorical structures that were then frayed by digressions born out of the material she shot.

Anna Sofia Rossholm provided something similar for Bergman. Out of the vast Bergman archive she quarried sixty “workbooks,” typically one for each film. Whereas Varda’s books were filled with cutouts and images, Bergman was a word man, treating the books as diaries that recorded “this secret I.” Anna Sofia proposed that in his jottings and planning, Bergman not only communed with himself (calling himself an idiot on occasion) but also explored patterns of doubling akin to those we find in the films. The workbooks evidently held a special place for him: he included their pages in films like Hour of the Wolf and Saraband.

David Lean might be thought of as working in between the Hollywood system and the more personal European milieu. Ian Macdonald suggested that one of Lean’s unfilmed projects sheds light on what he calls screenplay poetics. Macdonald seeks, I think, a principled method for studying the creative process. He does this by tracing how a screen idea is transformed in a series of documents generated by the creative team. The process, he points out, is governed by the participants’ various conceptual frameworks. For Nostromo, Lean solicited two screenwriters and oversaw their rather different versions of the novel. Ian showed that Lean seems to have found solutions to adapting the book by fitting it to the three-act structure advocated by Hollywood artisans, a concrete case of a filmmaker accepting a fresh “poetics” or set of creative constraints.

All of these inquiries could lead to more general thoughts about the creative process in cinema. For some filmmakers, it’s a professional task, undertaken with full knowledge that problems and constraints will have to be dealt with. For others, such as Bergman and Varda, it’s obviously deeply personal, even autobiographical. Perhaps most intimate was the film discussed by Hester Joyce. New Zealand filmmaker Gaylene Preston based Home by Christmas (2010; above) partly on audiotape interviews with her father as he recalled his World War II experiences. Her script reconstructed her interviews with actors, then filled in scenes with documentary footage and scenes she imagined. It’s a family memoir on several levels: Preston’s daughter portrays her own grandmother.

The Screenplay: What is it?

Several of these probes into the creative process raise a more theoretical question. How should we best conceive of the screenplay? As a blueprint? A recipe? An outline? These labels all suggest something disposable preliminary to the real thing, the movie. But why can’t we think of the screenplay as a freestanding object? After all, there are films without screenplays, but there are also screenplays—some written by distinguished authors—that were never made into films. And some of these, like Pinter’s Proust screenplay, are read for their own sake.

In cases like this, should we consider the screenplay a literary genre? And if the screenplay for an unproduced film can be considered a discrete object, what stops us from treating a filmed script in exactly the same way? Moreover, why even speak of a single screenplay, when we know that most commercial films at least go through several drafts? Can’t we consider each one an independent literary text? We’re now far from Carrière’s idea that the script finds its consummation in the finished film and as a piece of writing it should wind up in the ashcan.

And not all screenplays are literary texts. The scrapbooks and databases that Varda accumulates are works of visual art, collages or mixed-media assemblages. Are these merely drafts of the film, or do they have an independent existence or value? We seem to be asking the sort of question that Ted Nannicelli poses in his Ph. D. dissertation. Is there an ontology of the screenplay?

Take a concrete example. Ann Igelstrom’s paper, “Narration in the Screenplay Text,” asked how literary techniques are deployed in the screenplay. When a passage in the script for Before Sunset begins, “We see…,” who exactly is this we? Ann argued that traditional narrative concepts involving the source of the narration, the implied author and implied reader, and the rhetoric of telling can illuminate conventions of screenwriting. Here the screenplay seems definitely a literary text.

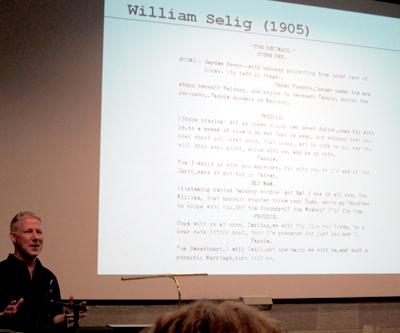

In his keynote address, “The Screenplay: An Accelerated Critical History,” Steven Price (above) declared a more abstract interest in the ontology of the screenplay but proposed that there was no clear-cut way of defining it. Historically, the screenplay takes many forms. Steven pointed out that even in Hollywood, there were many alternative formats, ranging from detailed breakdowns to the “master-scene” method (the option that didn’t specify shots or camera positions). And conceptually, the screenplay carried traces of its original production purposes, as well as other constellations of meaning. (Mack Sennett scripts seem to him part of a Sadean tradition of dehumanized, repetitive recombination.) So if there is a distinctive mode of being of the screenplay, outside of its role in production, it will turn out to be a messy one.

Envoi

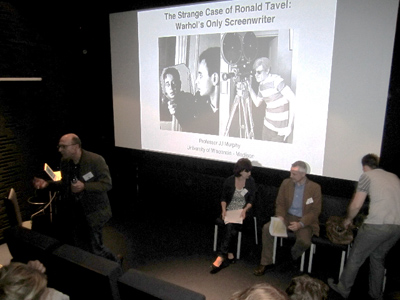

J. J. Murphy presents a paper on Ronald Tavel. Photo courtesy Richard Neupert.

If we conceive studies of screenplay and screenwriting as revolving around specific research questions, those of us interested in film as art can learn a lot. If our interests are in film history, researchers can show how organizations of production and individual choices by screenwriters/directors can shape the final product. For those of us interested in more theoretical explorations, asking about the nature and “mode of being” of the screenplay can’t help but make us think more about the ontology of cinema itself.

And if we want to know films more intimately, being aware of the creative choices that were made by the filmmakers throws a spotlight on aspects of the film we might otherwise not notice. It’s all very well to say we’ll examine the film “in itself,” but our attention is invariably selective. Knowledge of behind-the-scenes decisions can sharpen our awareness of artistic matters. Anna Sofia’s research on Bergman, like Marja-Riitta Koivumäki’s paper on Tarkovsky’s screenplay for My Name Is Ivan, activates parts of the film for special notice.

Because there were split sessions at the conference, and because I was plagued by jet lag, I couldn’t attend every panel and talk. I regret missing papers I later heard were very fine, and I haven’t written up everything I heard. I haven’t sufficiently talked about screenwriting pedagogy, represented in papers like Lucien Georgescu’s dramatic appeal to rethink whether screenwriting should be taught in film schools, or Debbie Danielpour’s stimulating survey of her methods of teaching genre scripting. So this is just a small sample of what these folks are up to. But you can tell, I think, that they’re posing questions at a level of sophistication that my 1960s cohort couldn’t have envisioned. Despite what the cynics say, there is progress in academic work.

As for men’s underpants: All is explained here.

I’m grateful to conference organizers Ronald Geerts and Hugo Vercauteren for inviting me to speak at the gathering. I must also thank conference organizer and old friend Muriel Andrin, along with Dominique Nasta and their colleagues and students from the Arts du Spectacle Department at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. My friends at the Cinematek, Stef and Bart and Hilde, helped me with my PowerPoint. Thanks as well to the Universitaire Associatie Brussel (Vrije Universiteit Brussel / Rits-Erasmushogeschool Brussel) and Associatie KULeuven (MAD-Faculty / Sint Lukas Brussel). A high point of the event was the visit to La Fleur en Papier Doré. Special thanks to Gabrielle Claes for her heartfelt introduction to my talk, not to mention a delicious bucket of moules.

A founding document in the contemporary study of the screenplay is Claudia Sternberg’s Written for the Screen: The American Motion-Picture Screenplay as Text (Stauffenburg, 1997). Other books central to the conference cohort include Steven Maras’s Screenwriting: History, Theory, and Practice, Steven Price’s The Screenplay: Authorship, Theory and Criticism, J. J. Murphy’s Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work, and Jill Nelmes’s anthology Analysing the Screenplay, which includes many essays by members of the group. See also the affiliated Journal of Screenwriting.

For more information on the Screenwriting Research Network, go here. (Thanks to Ian Macdonald for the link.) The next conference will be held in Sydney, and the 2013 one will take place in Madison, Wisconsin.

P.S. 22 Sept 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

P.P.S. Thanks to Joonas Linkola for a spelling correction!

Coke does go through you pretty fast. Richard Neupert at a Coca-Cola machine that exploits a Brussels landmark.

JCC

The Milky Way (La Voie lactée, 1969)

DB here, writing from a gray Brussels:

All the problems of a film are in the script.

When a film is made, the screenplay disappears.

When you consider what a scene needs to express, ask: How can the actor act it?

When you’re writing a scene, try to act it out yourself.

Rather than letting dialogue explain the action, let the action explain the dialogue.

It will always be possible to make films. Don’t forget to make cinema.

These and other epigrammatic insights flowed easily from Jean-Claude Carrière during his visit to the Cinematek of Belgium and the annual conference of the Screenwriting Research Network. I hope to devote a later blog to other attractions of this stimulating get-together. For now, a brief tribute to the volcanic charm of the legend known as JCC.

JCC entered cinema under the aegis of Jacques Tati. Tati wanted someone to turn M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Oncle into novels, and the very young writer seemed the right candidate. But Tati quickly learned that JCC didn’t know how a film was made. So he assigned Pierre Etaix and the editor Suzan Baron to tutor the lad in the ways of cinema. First lesson: Go through M. Hulot on a flatbed viewer, examining the script line by line while watching shot by shot. As a result, JCC says, he began to understand “the film that you don’t see.”

In the course of his career, JCC has written novels, plays, essays, screenplays, even a scenario for a graphic novel. In the process he became one of the most distinguished and respected screenwriters of the last fifty years. His most famous collaborations were probably with Buñuel, from Belle de Jour (1967) to the master’s last film, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). He worked with Etaix (The Suitor, 1962), Forman (Taking Off, 1971), Schlöndorff (The Tin Drum, 1979), Godard (Every Man for Himself, 1980), Wajda (Danton, 1983), Oshima (Max mon amour, 1986), Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1988), Peter Brook (The Mahabarata, 1989), Malle (Milou en Mai, 1990), and Haneke (The White Ribbon, 2007). He has also become known for his work on major French costume pictures and adaptations, such as Cyrano de Bergerac (1990) and The Horseman on the Roof (1995), as well as work with younger directors, including Wayne Wang (Chinese Box, 1997) and Jonathan Glazer (Birth, 2005). His TV scripts are numberless.

Directors both young and old come to him for the unique forms of collaboration that he offers. Instead of going off to write the screenplay, JCC meets frequently with the director. (Sometimes the director stays in his house.) He might ask the director to write the script for him, and they go over the result. Through these methods, JCC tries to help the director “find the film that he wants to make.” But his methods are flexible, tailored to the director’s temperament. When he was working with Buñuel, the men met daily to tell each other their dreams, some of which wound up in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). Similarly, JCC prefers to meet with the actors before production, letting them try out the parts so that he can revise things for each one’s habits of speaking. For Cyrano, Depardieu read the entire play aloud, taking all the parts, and then listened to it over and over on cassettes to refine his interpretation.

Brussels gave JCC a busy twenty-four hours. In conversation with the critic Louis Danvers he introduced a Cinematek screening of The Milky Way. He gave a keynote address for the Screenplay Network conference, and he participated in a panel discussion with members of the Flemish Screenwriters Guild at the film school RITS. These sessions ranged freely over his career and his conceptions of filmmaking. He believes that there is a language of film that sets it apart from other arts. That language is grounded in the play of meaning and emotion that comes from putting one shot after another.

He explained the point through an example that seems at first to be a restatement of the classic Kuleshov effect. In Shot 1, a man in his apartment looks out the window. Shot 2: The street. A woman is walking with another man. We’ll assume that our man is seeing them. Shot 3: Our man reacts.

But contrary to Kuleshov’s dictum, his facial expression should not be neutral. In fact, his expression tells us how to understand the scene. If the man looks upset, we surmise that he’s jealous. If he’s benevolent, we assume that the woman is a friend, his daughter—or a flirt. The filmmaker needs not only techniques like framing and cutting, but also the performances of actors.

Now cut to the woman in her bedroom brushing her hair. We need to make sure the audience understands that it’s the same woman, so maybe we have to go back and add a shot to the earlier scene, a closer view of her in the street. This constant flow and readjustment of images is based on guiding the spectator discreetly but firmly through the action. The audience isn’t aware of this “secret film,” but it governs everything the viewer thinks and feels.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

Where to get ideas for films? From the classics, of course. (“Balzac is the greatest screenwriter—every character is vivid.”) But above all you must observe reality. Tati taught JCC to sit vigilantly in a café. Study everyone who passes. Notice details. Imagine the person as a character in a story. Give him or her some motivations. What you must do is “find the fiction in the reality.” When JCC presided over the French film school La FEMIS, he promoted an exercise that required students to move out into a public space, like a market, and come back with stories about the people they saw. JCC praised Tati’s genius for spinning gags and situations out of passing life—“as if God had created the world so that it could furnish a film by Jacques Tati.”

JCC must be one of the few screenwriters who doesn’t gripe about his work being changed in its final incarnation onscreen. He sees the screenplay as ephemeral, the chrysalis for the butterfly. Once you accept the fact that your text must be sloughed off on its way to becoming cinema, you can take joy in your work. For young people, JCC advised the same relaxed, exploratory attitude. Conceive of yourself as a writer, able to move across media. The venues for your writing are constantly changing, so be prepared to write for television as well as film, to write comics and documentaries and plays. Above all, “Don’t despair of the future of cinema. It’s wide open.”

Jean-Claude Carrière turns eighty next week.

The best introduction to Carrière’s career and ideas that I know is his book The Secret Language of Film (Faber, 1995). Some of this text overlaps with Exercice du scénario (FEMIS, 1990), coauthored with Pascal Bonitzer. That book is worth reading too, but it hasn’t to my knowledge found English translation. An illuminating interview is here.

P.S. 11 September 2011: Thanks to Jonathan Rosenbaum for correcting an error in JCC’s filmography, which I’ve rectified above. Jonathan also remarks:

I assume that you know, by the way, that Carrière appears in a scene of Certified Copy, playing something similar to the “wise old guru” role played by the Turkish taxidermist in Taste of Cherry and the doctor in The Wind Will Carry Us.

I did know and should have worked it in!

P.P.S 22 September 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

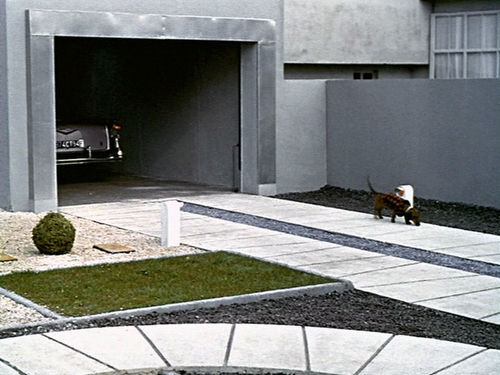

Mon Oncle (1958). “I followed Tati more or less everywhere, usually with Etaix, attending projections followed by long anxious discussions. (‘Can we clearly see the dog’s tail go past the electric eye that shuts the garage door? Yes? Clearly? You’re sure people will see it?’)