Archive for the 'Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato' Category

French silents from Il Cinema Ritrovato 2021

L’Arlésienne (1922)

Kristin here:

Like so many of our fellow festival-goers, David and I were not able to visit Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival of restored films and curated thematic threads. Fortunately the organizers made a selection of the films and events (interviews, discussions of films by archivists) available online.

We were not able to watch all of these, so we concentrated on an area in which we have both worked, French silent cinema. There were three of these, or six if you count the four episodes of the 1927 serial, Belphégor. They were beautiful restorations, all presented in black and white. (I must admit, beautiful though tinted and/or toned films are, I prefer the black-and-white versions. That’s mainly because if one is taking frame enlargements for reproduction in black and white in a publication, it is often impossible to get a decent copy from a tinted print.)

No doubt it is frustrating to read about films that are unavailable to see outside archives. Still, some of the Cinema Ritrovato films travel after their presentations at the festival, and some appear on DVD/Blu-ray. These are three to keep an eye open for.

L’Arlésienne

I must admit, this was the only title of the three that I recognized. David and I had been very impressed by André Antoine’s earlier films. (See our brief comments on and some frames from his extraordinary 1917 Le coupable here and here.)

While Le coupable was a courtroom melodrama set in Paris, L’Arlésienne follows his 1921 naturalistic film La terre by being shot in the French countryside. In this case the story takes place in and around Arles, at that time a village in the south of France, not far from the Mediterranean coast northwest of Marseilles. The familiar tale concerns the family of Rose Mamaï, a widow who runs her large farm, aided by her cheerful, naïve son Frédéri, who seems destined to marry Vivette, from a nearby farm, until he falls under the spell of the unnamed title character.

The film is not as splendid as the two earlier ones, but it is well worth seeing nonetheless. It gets off to a somewhat slow start, with a leisurely exposition of the locales and the characters. Frédéri’s growing obsession with l’Arlésienne takes its time. Still, conflict eventually creates greater drama as Rose learns of her son’s love for a woman “with a past” and the woman’s lover shows up to try and thwart her golddigging attempt to marry Frédéri.

The gorgeous cinematography and use of authentic locations, however, more than offset the plot problems (see frames above and at top). Like so many French directors of the silent era, Antoine took advantage of local carnivals and holidays, economizing by filming the crowds candidly. The frequent glances into the camera by locals testify to that.

To the far left of this frame, one can glimpse the well-known Roman amphitheatre of the town, used in L’Arlésienne for a bullfight scene, whither the villagers in their best clothes are headed.

Antoine’s film makes an interesting comparison with Alberto Capellani’s 1908 version, shown in the first Cinema Ritrovato season of his films. Capellani shot most of his excellent version in Arles as well, though in a very different style. (I discuss it briefly here and here; the latter entry gives information on the DVD releases of various Capellani films shown at the festival, including L’Arlésienne.)

Figaro (1927)

Gaston Ravel is a director whom many of us have heard of, but few of us have seen his films. His reputation is as a director of high-budget, prestigious films–comparable to Raymond Bernard, whose The Miracle of the Wolves (1924) is perhaps the most familiar of the epic period films of the period, excepting Napoléon vue par Abel Gance (1927).

With Figaro, Ravel manages to condense all three of Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s three Figaro plays (Le Barbier de Séville [1775], Le Mariage de Figaro [1781 but banned from performance until 1784], and La Mère coupable [1792]) into a two-hour film.

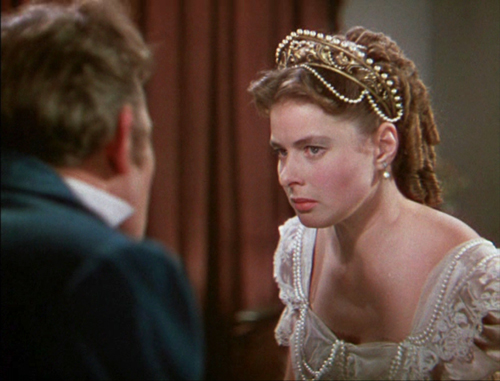

The result is a lavish spectacle. The costumes were designed by J. K. Benda, who later created those of La Kermesse héroïque (Jacques Feyder, 1935). The interior sets were studio-built (see bottom), though the exteriors of the later parts of the film were shot at a huge chateau with extensive grounds, the Rochefort-en-Yvelines. At least some French directors had by this point adopted and mastered Hollywood three-point lighting, as the frame above demonstrates.

Visually the film in fact looks like it could have been made in one of the big Hollywood studios, though the story is a bit too risqué to have been made there. (The young lady dancing and trailing a long, diaphanous veil in the frame at the bottom eventually spins until it drops off, leaving her completely nude.)

I found the casting of “artistic dancer” Edmond van Duren (as the program notes describe him) unfortunate. He reminded me of the overly merry Merry Men in Alan Dwan’s 1922 Robin Hood, bounding through nearly every scene. The rest of the actors were fine, particularly Arlette Marchal as Rosine, later the Countess Almaviva.

The tone also changes across the film, from comedy in the first part, to drama in the second, and then to tragedy (or melodrama?) in the third. The original plays premiered so far apart that the changes might have been less noticeable or made more sense. Mozart, however, was wise to confine himself to the middle play.

Apart from such problems, however, the film is entertaining, as well as being an important example of how ambitious a project French studios could occasionally manage–as does the film immediately below.

Belphégor (1927)

By the 1920s, Hollywood serials had declined from being the center of a program to being a low-budget side attraction. In France, however, serial storytelling remained quite central to the industry. Some serials were presented as discrete episodes, each involving a continuing set of characters, as in a television series. Other installment-films were “ciné-romans,” telling a continuous tale in blocks that might be published at the same time in newspapers and magazines.

Louis Feuillade’s death in 1925 ended his long string of beloved serials and ciné-romans for Gaumont. Other studios made equally popular, big-budget items, including Albatros, with Alexandre Volkoff’s 1923 La Maison du mystère. That film’s reputation lingered in film history despite the unavailability of complete prints until recently. By contrast, Henri Desfontaines’ Belphégor has remained largely forgotten.

Now it has been restored in a beautiful version. Although it, too, centers around a mysterious master criminal out to control the world, it is miles away from the wonderful mid-1910s serials of Feuillade. It’s instead a strange and impressive combination of various elements of French cinema of the 1920s. Where Feuillade shot in a rough-and-tumble way in the streets of Paris or the environs of Nice, with cheap sets for interiors, Belphégor‘s settings immediately remind one of L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine and L’Argent. In particular, the exterior (above) and interiors (below) of the Baroness Papillon recall that of Claire Lescot in the former film.

Like Figaro, Belphégor has impressive production values and a grasp of Hollywood three-point lighting that creates dark, suspenseful shots. The film gained some prestige by supposedly being the first story to be set inside the Louvre. The interiors, of course, are sets, but ones that successfully convey the look of a major museum at night.

The script has a certain looseness, perhaps caused by the fact that the episodes were being released in parallel to the serialization of Arthur Bernède’s novel in Le Petit Parisien. That journal’s director also headed Cinéromans, a production firm making films exclusively for distribution by Pathé.

A meandering and repetitious plot is not the film’s main problem. The common–and probably correct–assumption that a film’s villain must be a strong, interesting character is completely ignored here. We see “Belphégor” only occasionally, looking like a person dressed in a burka with some checkered decoration around the head. Unlike Fantômas and other Feuillade villains, we never see Belphégor out of costume until the very end. Instead the villain’s machinations are largely carried out by a pair of thugs who have a faintly ludicrous, not-very-dangerous air. Belphégor, when encountered in the Louvre by the guards and investigators, invariably runs and, after a brief chase, escapes.

Oddly enough, the main detective, Chantecoq, is played by René Navarre, so memorable as Fantômas. (He was one of the co-founders of Cinéromans in 1919.) His presence hovers over the film, emphasizing that the main villain is barely present and does little.

Like the two other films discussed here, Belphégor’s pristine restoration, its beautiful sets and cinematography, and the expert lighting make it a pleasure to view. Complete serials from this era are so rare that as an historical document, it is welcome indeed.

Although these three films are not among the masterpieces of the 1920s (though L’Arlésienne comes closest), they give us more insight into French cinema of the day–a national cinema that has remained somewhat in the shadows of the German Expressionist and Soviet Montage movements of the same period.

As usual, the festival held its Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Awards ceremony, though by this point the competition is dominated by Blu-ray releases. Our friends at The Criterion Collection, Flicker Alley, and Kino Lorber figured prominently in the awards and jury members’ favorites, as did international archives and companies. I have blogged about the two Flicker Alley jury favorites, Waxworks and Spring Night Summer Night.

Figaro (1928).

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021: Streaming goodness

Trailer by Christina King.

DB here:

We’re been tardy about posting lately. Reasons, not excuses: I finished a book manuscript of ungainly length. Kristin has been preparing and giving a talk for an Egyptological conference. Some medical matters (non-fatal, boring) have preoccupied me further.

But who could resist telling you about the offerings of our revived Wisconsin Film Festival? Felled last spring by COVID, it has bounced back as lively as ever. Over 110 films are streaming over eight days, 13-20 May.

Some films are available to anybody anywhere, others only to people in Wisconsin or the Midwest or the USA. Some screenings may be “at capacity” because of audience limits set by distributors (who reasonably don’t want to cannibalize screenings at other fests). You can check your access to a film by visiting that film’s Eventive page on the fest site, and you can learn how to access the fest shows on the Eventive information page.

In particular, many of the regional productions we proudly host might be things you can’t be sure of catching anywhere else.

The other S-word

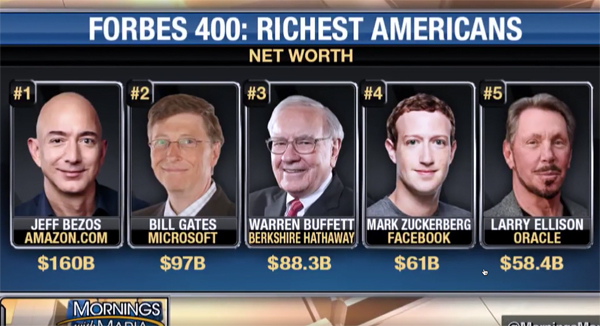

“Socialism” is back in the news. 120 mostly obscure brass hats have just proclaimed that the 2020 election was stolen. (Maybe this level of cluelessness explains our post-1945 record of winning wars.) The signatories add that the immediate conflict is “between supporters of Socialism and Marxism vs. supporters of Constitutional freedom and liberty.” These writers who obviously have not seen Dr. Strangelove or Seven Days in May. Otherwise, they’d try out better lines.

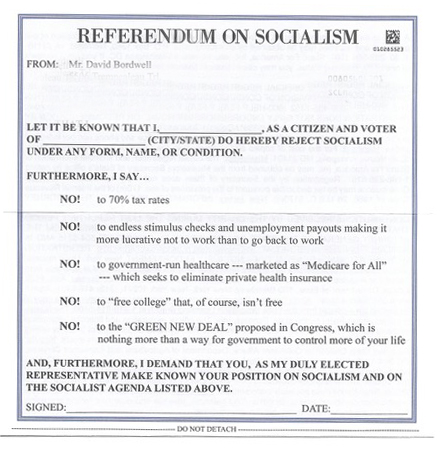

Earlier this week I received an invitation from former UN Ambassador Nikki Haley to sign up for the “National Referendum on Socialism.” The envelope window displayed a teasing flash of legal tender. It turned out to be a crisp 100-Bolivar note from Venezuela, worth about $.10.

This crushing proof that socialism doesn’t work was accompanied by Nikki’s memoir about seeing, first hand, the failures of regimes like Venezuela, Cuba, and Communist China, all representing “the terminal stage of socialism.” She reports that some of them lack toilet paper. This outrage must not stand.

For me to receive this, the Republican Big Data dragnet proves as undiscriminating as a notification I’ve inherited a fortune in Bitcoin. Still, I was happy to reply. I voted yes, or as Nikki would have it YES!, to all the options. These included 70% tax rates for her and her friends and a rejection acceptance of Nordic social democracy, an option her world travels seemed to have missed. And I’m keeping the Bolivars.

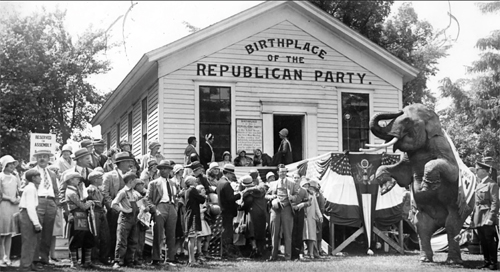

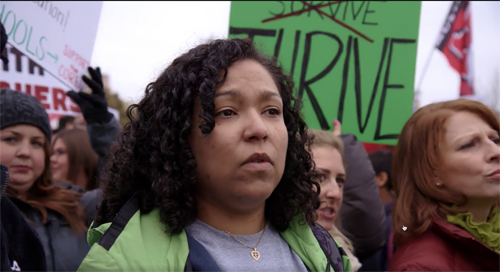

So the right-wing lies make it all the more timely that WFF has included a double feature that might well speak to the rising interest in socialism among the young and the equality-curious. The main film is Yael Bridge’s The Big Scary “S” Word. It interweaves an historical narrative with two ongoing dramas of today. From the survey we learn, as Cornel West explains, that socialism is “as American as apple pie.” John Nichols, author of The S-Word, is on hand to trace the movement back to the nineteenth century and remind us that “The Republican Party was founded by socialists.”

Other commentators show how the rise of capitalism and the cascade of crises it brought forth tended reliably to arouse demands for equal rights and economic justice. We learn of Lincoln’s friendly correspondence with Marx, of slavery’s centrality to American capital accumulation, and of the post-World-War II reaction against the New Deal, building through Reagan to Bush and Clinton. The 2008 financial crisis supplied fresh momentum for a critical reaction to capitalism; Wall Street’s capture of the economy encouraged some people to take a new look at socialist policies.

There are as well doses of theory, as when political scientists point out that capitalism depends crucially on expanding the concept of private property and inclines toward treating unpropertied individuals as interchangeable, expendable units. This may explain why conservatives explode over graffiti but praise a teenager shooting down peaceful demonstrators.

Threaded through Bridge’s account are affirmative moments: the creation of worker-owned coops, the establishment of the Bank of North Dakota (owned by taxpayers), and the stories of two young people who were fed up with injustice. One is Stephanie Price, an elementary-school teacher working two jobs; some of her income goes to books and supplies for her students. (This scenario is familiar.) She joins a teachers’ strike and finds that the union isn’t effective in fighting their Oklahoma legislature. Chris Carter, an ex-marine, is the only socialist on the Democratic side of the Virginia legislature. He learns that even Democrats are capable of sabotage (surprised?), running an oppo ad linking him with a hammer and sickle. The stories of Stephanie and Chris provide suspense and yield a flare of hope.

How to Form a Union, directed by Gretta Wing Miller, is a story that could only come from the People’s Republic of Madison. During the 197os, the Willy Street Coop was an emblem of our town’s progressive tradition. But as it expanded, it faced competition from Whole Foods and other hip purveyors of provender. (I remember visiting Whole Foods and feeling old when Björk came on the Muzak.) Workers at the Coop accused it of corporatization and agitated for higher wages, less draconian shift policies, and ultimately a union. What happened next is told with quiet passion and a fine array of talking heads.

The proclamations of our statewide election officials, cartoonish reactionaries like Ron Johnson, Glenn Grothman, and their lot, have over the last few years made me think that such large, loud, stupid people typify Wisconsin. Seeing these two films, steeped in state history, reminded me of things we can be proud of. Yes, Wisconsin gave America Joe McCarthy and Scott Walker and Reince (Obvious Anagram) Priebus and Scott Fitzgerald, who greeted voters in a hazmat suit while assuring them that Covid was no danger. But we also gave America socialist mayors, Bob LaFollette (a Republican), and political fighters like Tony Evers, Mandela Barnes, Mark Pocan, and Tammy Baldwin. These are people on the right–that is, left–side of history.

Roman New Year

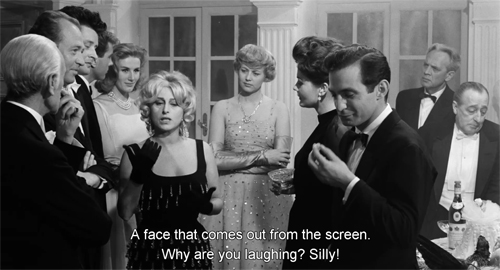

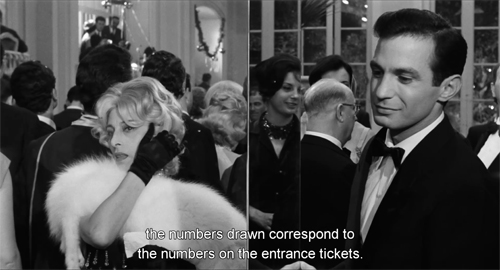

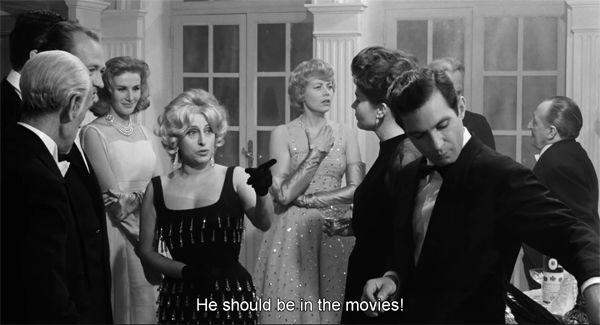

The Passionate Thief (1960).

One of the long-running revelations of the Bologna festival Cinema Ritrovato is the rich tradition of Italian comedy. (See here, and here.) One admirer is our programmer Jim Healy, who this year brought us a delightful example, Mario Monicelli’s The Passionate Thief (another film from the fabulous year 1960). Two top Italian stars, the vivacious Anna Magnani and the glum Totò, work on the fringes of the film industry. This justifies behind-the-scenes glimpses of Cinecittà, as well as the usual satire on the follies of filmmaking. We’re introduced to Magnani as part of a crowd in a sword-and-sandal epic, while Totò scrapes up work as an extra.

But it’s New Year’s Eve, and Magnani seeks out friends for a party. Meanwhile Totò is recruited as a partner for pickpocket Ben Gazzara, in the sort of imported-star turn that was common in European coproductions. His brooding, cynical presence adds a touch of gravity to a crowded night of crisscrossing destinies featuring a drunk American millionaire (Fred Clark), frenzied Roman partygoers, and rich Germans whose mansion is invaded by our trio. Gusto, brio, sprezzatura, zest–choose the word, this movie has plenty.

It also has stunning black-and-white cinematography, and its use of the 1:1.85 ratio should be studied by every film student. The screen area is shrewdly filled in long-take mid-shots.

And since we know Ben is a thief, his wandering left hand draws us away from La Magnani’s monologue, while Totò frets in the background.

Yes, mirrors are involved throughout, sometimes creating weird split-screen effects.

Much of the movie was shot on location and it reminds us that the splendor of La Dolce Vita (released the same year) wasn’t a one-off.

This ripe imagery doesn’t slow down the bustle of the whole thing. The plot seems more episodic than it is; the opening sets up a minor character (a tram driver) and a food motif (lentils) that will pay off later. Clever as the devil, The Passionate Thief is one of those pieces of good dirty fun that keeps you, and us, going back to film festivals.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of the festival panjandrums (I always wanted to use that word) Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

The Passionate Thief (1960).

Il Cinema Ritrovato: More and more

Il Cinema Ritrovato Book Fair (photograph Margherita Caprilli).

Kristin here:

I mentioned in my entry on the African thread at this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato that I filled in blank spaces in my program with a miscellany of intriguing films. Here are some of those films I saw, and others that David saw.

O Pão (1959)

Manoel de Oliveira’s first film, the gorgeous black-and-white documentary short, Douro, Faina Fluvial, was released in 1931. His last, Um Século de Energia, another documentary short, came out in 2015, the year of his death aged 106 (as did Visita ou Memórias e Confissões, a deliberately posthumous legacy film shot in 1982). That’s an 84-year career. I doubt any other filmmaker can claim as much.

Initially that career proceeded in fits and starts. He made more documentary shorts in the 1930s and then a black-and-white feature, Aniki-Boko (1942), during the war under an authoritarian regime. After the war he could not find funding and decided to study color filmmaking in Germany. During the 1950s he applied his resulting expertise to two documentaries: O Pintor e a Cidad (“The Painter and the City,” 1956) and O Pão (Bread). A beautiful print of the latter was shown in this year’s Ritrovati e Restaurati thread. It was to be his last film before he turned to feature filmmaking, though he never entirely gave up documentaries, particularly near the end of his life.

This hour-long film slowly follows the entire progress of bread, from wheat-fields to milling to baking to consumption. The images, whether in field or factory, are lovely, showing that Oliveira had indeed learned a great deal about color.

There is no voice-over narration, even during a lengthy scene in a large mill where technicians perform mysterious tests on samples of flour. The slow progression creates a soothing, almost mesmeric tone. Only toward the end does some social criticism emerge. A hungry urchin stealthily retrieves a roll dropped by a shopper, only to have it snatched away by a little street thug. Clearly bread, despite the lyricism of its production, is not for everyone.

Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Avval, Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Duvvum (1979)

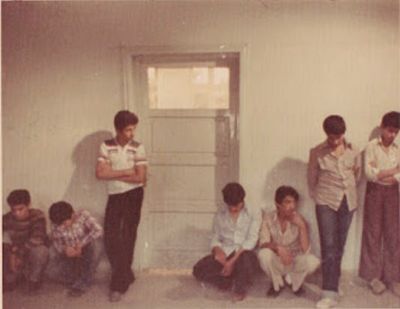

Another must-see was Abbas Kiarostami’s early film, First Case, Second Case, also presented in the rediscovered-and-restored thread. Like Oliveira, Kiarostami began in documentary work. This remarkable film was started before the 1979 Iranian Revolution and finished after it–and then banned.

The film’s beginning rather resembles other Kiarostami openings, with a simple scene in a classroom. A teacher drawing the anatomy of an ear on a blackboard is interrupted by a knocking noise caused by one of his students. No one confesses or reveals who caused the noise, and the teacher suspends seven of the boys, who spend the next days in the hall outside the classroom.

This scene is revealed to be a 16mm film being shown to a succession of teachers, government officials, religious leaders, and the fathers of some of the boys. In the latter cases, some variant of the framing above is shown, with an arrow pointing to the son of the father being interviewed. Unseen, Kiarostami asks them the same question: did the boys do right in refusing to reveal who disrupted the class? Some of these interviewees became key figure in the Islamic Revolution. (Jason Sanders’ program notes for a screening of the film provide some information about this historical context.)

This “documentary” has of course been carefully staged. A page from Kiarostami’s script reveals how he designed the passing days of the boys’ suspension, with different ones standing or sitting each time. The illustration is from Ritrovato programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht’s blog entry on the film, where he credits First Case, Second Case with introducing the interview technique into the director’s work.

This first case shows the boys maintaining their refusal to identify the culprit. In a new scene, the second case, an alternative outcome shows one of the boys naming the guilty classmate to his teacher. Again, Kiarostami interviews many of the same people as to whether they believe the boy’s decision can be morally justified.

If not as charming as some of Kiarostami’s later work, First Case, Second Case contains a familiar combination of complexity and simplicity, as well as a fascination with people telling their own versions of events.

The film has been picked up by Janus in the USA, which should mean that it becomes available from Criterion on Blu-ray and/or its streaming service, The Criterion Channel.

Twelve O’Clock High (1949)

In recent years, Il Cinema Ritrovato has featured the films of a major Hollywood director as one of its main threads. This year it was Henry King. I managed to miss nearly all of his films. In part I feared that, since the auteur du jour is always one of the the more popular items in the program, the screenings would be crowded. Word of mouth suggested that they were.

Still, I had an afternoon free, and I wanted to guarantee myself a good seat for Varda par Agnès, showing later in the day. I went to an earlier screening in the same theater, and I was glad I did. Twelve O’Clock High is an impressive and entertaining film, if not an outright masterpiece.

Fitting into David’s set of innovations typical of the 1940s, the action is enclosed by a framing situation. A man we eventually discover was an American officer posted in England during World War II bicycles out into the countryside and visits the derelict remains of the military airport where he served. (Above, played by Dean Jagger in a role that won him a best-supporting-actor Oscar).

For a long time the story concentrates on General Frank Savage (Gregory Peck), who takes over command of an underperforming bomber unit in the same air station we saw at the beginning. He proves an absolute stickler for discipline, initially alienating the pilots he commands. Eventually he wins their respect, of course, and he learns to unbend a bit.

Eventually a series of air battles occur, with some very impressive and genuine combat footage, including aerial views of bombs exploding on their German targets. The film was presented in a nearly pristine 35mm print, which certainly contributed to my pleasure at having ended up at that screening somewhat by chance.

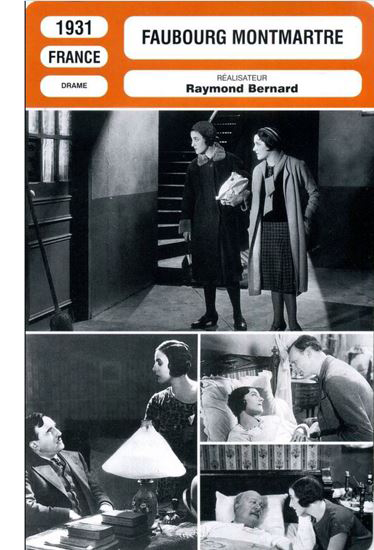

Faubourg Montmartre (1931)

I definitely planned from the start to see this film. I very much admire director Raymond Bernard’s 1932 World War I drama Wooden Crosses, his next feature after Faubourg Montmartre. Indeed, I had done a video on it for The Criterion Channel (“Observations on Film Art” #16 “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses“)

While a slighter film than Wooden Crosses, Faubourg Montmartre is quite stylish and technically impressive, considering that it was Bernard’s first sound film. In it he abandons his concentration during the silent era on historical epics (his best-known being The Miracle of the Wolves, from 1924).

Here he tackles a melodrama in a contemporary setting, centering around Ginette, a somewhat naive young working-class woman, played by popular star Gaby Morlay. She and her older sister Céline live and work in the titular district of Paris, the disreputable area of cheap entertainment and brothels. Céline works as a prostitute but tries to protect Ginette from such a life. Becoming more dependent on drugs, however, she nearly dupes Ginette into following her into prostitution.

Despite its grim setting, the film has many light moments, mostly provided by the amiable Morlay. It also contains some impressive musical numbers, one a variety number by Florelle and a café song about prostitution by Odette Barencey.

The film was yet another in the festival’s Ritrovati and Restaurati thread.

Georges Franju

There was an unaccustomed focus on documentaries this year, which presumably was the occasion for devoting a small thread to Franju. Of the thirteen shorts which he made or at least is tentatively credited with (most of them commissioned documentaries), eleven were shown. Judex, his fiction feature paying homage to the serial of the same name by Louis Feuillade, was also on the program.

I tried to see all the Franju shorts, since only Le Sang des bêtes (above) and Hôtel des Invalides are well-known in the US. The prints shown ranged widely in quality, some being in 35mm and some 16mm. En passant par la Lorraine was almost unwatchable, though most of the rest were in varying degrees acceptable.

The most interesting revelations were perhaps Mon chien (1955), a melancholy narrative based on the common habit of people abandoning their pets in the countryside. The amazingly callous parents of the little heroine dump her beloved German shepherd in the woods on their way to a vacation spot. The film follows the faithful animal’s trek home, only to find a locked house and a dog-catcher waiting. An empty cage signals that the animal was euthanized, with the voiceover of the girl calling forlornly for her pet. The other was Les poussières (1954), a lyrical survey of many kinds of dust generated in the world, ending in a strong anti-pollution message.

It was a pleasure to see this body of work brought together, but the screenings also demonstrate the pressing need to restore many of these films.

A Gabin tribute

DB here (with films I saw in boldface):

Jean Gabin has become emblematic of French cinema from the 1930s and after, so the several films devoted to him were welcome. Programmer Edward Waintrop included the classic Pépé le Moko (1936) but correctly assumed he didn’t have to show this crowd La Grande Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and Le Jour se Lève (1939). Edward’s catalog entry wisely emphasized how much Gabin owed to Julien Duvivier, an underrated director who helped the young actor find starring roles.

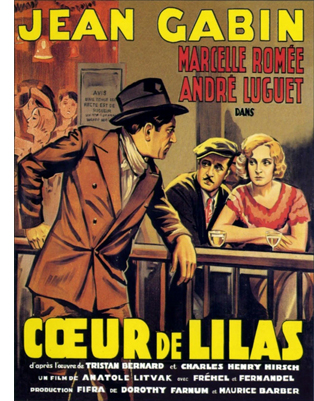

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

In her book on popular song in French cinema, our colleague Kelley Conway has written a superb analysis of Cœur de Lilas, and you can find a clip of Gabin’s big musical number here. Director Anatole Litvak handles his performance in a long tracking shot that keeps our attention fastened on Gabin’s half-scornful, half-boastful mug as he spits out lines about his girlfriend’s bedroom calisthenics (“The rubber kid. . . She dislocates you”).

Gabin plays the third point of a love triangle in Cœur de Lilas, but he’s somewhat more central to the lesser-known Du Haut en Bas (1933), a sort of network narrative that reminds us that The Crime of M. Lange (1936) isn’t the only film tracing the tangled passions in a courtyard community. More easygoing here but still a force to be reckoned with, Gabin plays a footballer with his eye on an aspiring teacher forced to work as a maid. Other plotlines, including Michel Simon’s raffish wooing of his landlady, intermingle in this thoroughly agreeable movie by the great G. W. Pabst.

A generous sampling of Gabin’s later career included La Marie du Port (1949), Le Plaisir (1951), Maigret tend un piège (1957), and the brutal Simenon adaptation Le Chat (1970), the first film I saw on my first visit to Paris. En Cas de Malheur (1957), an efficient plunge into sex and crime by Autant-Lara, features Gabin as a prestigious but dodgy lawyer drawn to the pouting self-regard of Brigitte Bardot. In youth and age, as a sort of French Spencer Tracy, Gabin could exude both relaxed joie de vivre and stolid menace. An icon, as we say.

Americana, urban and rural

State Fair (1933).

Speaking of Spencer Tracy, it was a pleasure to see this Milwaukee native in a long-neglected racketeer drama. Quick Millions (released May 1931) arrived in the middle of the first big gangster cycle and was overshadowed by two Warners hits, Little Caesar (January 1931) and The Public Enemy (May 1931). As part of Dave Kehr’s welcome second Fox cycle, Quick Millions had its own pungent force.

It traces the familiar trajectory of a working stiff, trucker “Bugs” Raymond, who claws his way to the top of the mob. Thanks to blackmail and crooked labor maneuvers (“The brain is a muscle,” he tells his moll), he winds up triggering a spate of gangland killings that eventually swallows him up.

Quick Millions was noticed as one of the earliest films to find a smart tempo for talkies, one that relies less on long speeches than snappy scenes delivering one point apiece. The passage of time is signaled by changing license plates, and the ending is a shrug, shoving Bugs’ death offscreen and giving him none of the tragic flourishes of Little Rico or Tom Powers. For almost every scene, the little-known director Roland Brown finds an unexpected twist in visuals or performance . Who else would film a sidling George Raft jazz dance from a high angle and then supply inserts of his legs, from behind no less?

Fox found more success with a folksy Grand Hotel variant based on the popular novel State Fair (1932). Henry King’s 1933 film was planned as an “all-star” vehicle, and it did boast Will Rogers, Janet Gaynor, and Lew Ayres. An Iowa family heads to the fair, aiming for blue ribbons in pickle preserving and hog-fattening. The son has a surprisingly carnal affair with a trapeze artist, while the daughter meets a roguish reporter who makes her rethink her engagement to a hick back home. State Fair‘s script gives the plot a happier ending than the book did, but that’s not necessarily a problem; we want these kind souls to enjoy a bit of glory.

Henry King became famous for rustic realism with Tol’able David (1921), a model for Soviet filmmakers, and Ehsan Khoshbakht’s King retrospective reminded us that he worked this vein a long time. From 1915 Twin Kiddies (a Marie Osborne vehicle) to Wait ‘Till the Sun Shines, Nellie (1952), this loyal Fox craftsman showed himself, like Clarence Brown at MGM, an adaptable director with an unpretentious gift for celebrating small-town life.

Still more, more…

Under Capricorn (1949).

I could go on about other films, such as Zigomar: Peau d’Anguille (“Zigomar, the Eelskin,” 1912), Victorin Jasset’s forerunner of Feuillade’s delirious master-criminal sagas. (In one episode, an elephant’s trunk fastidiously picks the lock on a circus wagon and drags away a strongbox.) Our next entry will spend a little time looking at a neat Genina film from 1919. In the meantime, I’ll sign off by mentioning two other high points.

The pretty Academy IB-Tech print of Under Capricorn (1949) made me like the film quite a bit better than previous viewings. As ever, one high point was La Bergman’s virtuoso soliloquy admitting her guilt. Any other director of the time would have reenacted the crime in a flashback, but, in the shadow of Rope (1948), Hitchcock makes her squeeze out her confession in a ravishing single-take monologue running almost eight minutes.

Its power comes partly from the fact that the framing withholds the facial response of the man who loves her. He’s slowly understanding the depth of her devotion to her husband during penal servitude. “How did you live all those years?” he murmurs. How’d you think? Her glance flicks over him, in both guilt and defiance (above).

Finally, no film gave me more pure pleasure than the restoration of Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome (1959). Sony archivist Grover Crisp explained that the original prints had all been made from the camera negative (!) and so he had no internegatives or fine-grain masters to work from. Nevertheless, this digital version, made in 4K with wetgate scanning, looked superb.

I tend to judge Boetticher westerns by the strength of the villains, meaning that Seven Men from Now (Lee Marvin) and The Tall T (Richard Boone) sit at the top of my heap, but it’s hard to resist the laconic dialogue Burt Kennedy supplied everybody in Ride Lonesome. And the antagonists facing Randolph Scott here–Lee Van Cleef (brief but unforgettable), Pernell Roberts (the good-bad rascal), and sweet-natured dimwit James Coburn (on his way to rangy knife-wielding in The Magnificent Seven)–add up pretty powerfully. Against them stands Scott as vengeance-driven Brigade, an unyielding chunk of sweating mahogany.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator. Thanks also to Dave Kehr, Grover Crisp, Mike Pogorzelski, and Geoffrey O’Brien for talk about many of the classics on display.

The entire Ritrovato ’19 catalogue, with full credits and essays, is online here. There are also videos of many events, including master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Quick Millions was remembered several years after its release for “the rapid rhythm of its continuity.” See Janet Graves, “Joining Sight and Sound,” The New York Times (29 November 1936), X4.

John Bailey’s introduction to Under Capricorn included a revealing short explaining the Technicolor dye-transfer process. For further information there’s the remarkable George Eastman House Technicolor research site and of course James Layton and David Pierce’s superb book The Dawn of Technicolor.

Kristin discusses Kiarostami’s landscape techniques in a Criterion Channel Observations entry. In American Dharma, discussed by David here, Errol Morris reveals that Twelve O’Clock High was an inspiration for Steve Bannon’s political career.

The Ritrovato program notes credit Fréhal as the working-class singer in Faubourg Monmartre, but Kelley Conway’s Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in French Film (linked above) identifies her as Odette Barencey, a lesser-known chanteuse of the period who resembled Fréhal.

Opening shot of Ride Lonesome (1959).

Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019: Who put the Pan in Pan African cinema?

Muna Moto (1975)

Kristin here–

With the plethora of films on offer this year at the XXXIII edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I decided that a necessary strategy for choosing those to watch would be to follow certain threads faithfully and then fill in the remaining time-slots with bits and pieces from other threads. (The entire program, with notes, is online here.)

A program that formed part of the core of my viewing for the festival’s eight and a half days was “Cinemalibero. FESPACO 1969-2019.” It was curated by Cecilia Cenciarelli, whose program notes explain the post-colonial context behind this fiftieth-anniversary celebration:.

“Decolonisation of the screen” also spread at a grassroots level: birthplace of the future FESPACO, the film club of the Centre Culturel Franco-Voltaïque in Ouagadougou (capital of the then Republic of Upper Volta) organised the first Semaine du cinéma africain in February of 1969. Cinema filled every venue of the city: the Nadar and Olympia cinemas, schools, offices, the People’s House and Hôtel Indépendance, the legendary filmmakers’ headquarters. Over 50 films made in Senegal, Niger, Upper Volta, Cameroon and Benin by directors like Sembène, Samb, Traoré, Alassane and Sita-Bella were screened.

The first festival in 1969 has been credited with bringing together filmmakers from all over the continent to launch an effort to support Pan African filmmaking. Short documentaries showing FESPACO in its early years, mostly by Tunisian filmmaker Mohamed Challouf, were shown before several of the features.

The program was built around eleven films directed by pioneers of the festival and the Pan African Cinema effort in general. Of those, eight were recent restorations–some of them dated 2019. Some of these films have been available online in copies with poor visual quality, and I hope now the new prints will make their way onto Blu-ray or DVD. (Ousmane Sembene, the African filmmaker best known in the West, was not represented in the program, but he was instrumental in the founding of FESPACO.)

A key problem in restoring and distributing these classic African films is the fact that many of them had to be processed in European laboratories, often in France, and the original negatives and other elements were stored there. In some cases their whereabouts are now unknown, and tracking them down has been a key factor in making them accessible again.

Here is a brief description of each film, in the order in which they were shown. In keeping with the theme of Pan African cinema, every film originated in a different country.

De quelques événements sans signification (1974, Morocco)

As the program demonstrated, the mid-1970s were a key period for the establishment of Pan African cinema. Many show the influence of European filmmaking, since several African filmmakers studied filmmaking abroad.

Mostafa Derkaoui’s 1974 film shows the influence of Godard. Its early section consists of an extended scene in a bar, where telephoto shots move across a group of filmmakers debating what direction the establishment of Moroccan cinema should take. They take to the streets to explore the situation of workers.

When one of them kills his boss, the plot takes shape as the filmmakers focus on his situation as the subject of their film. Ultimately the worker rejects their interpretation of his crime, leaving the question of how Moroccan cinema should proceed up in the air.

Les bicots-négres, vos voisins (1974, Mauritania)

Two years ago, Med Hondo presented his West Indies (1979) at Il Cinema Ritrovato. It was my introduction to his work. As I reported at the time, Hondo was thoroughly ingratiating and was moved to tears by the enthusiastic applause we gave his film. This year the two diretors who attended, Jean-Pierre Kinongué-Pipa and Souleymane Cissé, were similarly touched by their reception. It is a pity that such recognition has been so long in coming. Hondo’s death in March of this year and Moustapha Alassane’s in 2015 perhaps deprived us of other guests who might have realized that their films will live on as classics.

Hondo’s Les bicots-négres, vos voisins (roughly, “The Arab-niggers, your neighbors”), also shows a strong influence of Godard’s political films of the 1970s, and yet it is thoroughly original as well. The film breaks into seven separate sequences–all politically didactic and yet greatly varied in their approaches. The results is continually riveting.

Aboubakar Sanogo’s program notes describe this variety:

It comprises seven sequences exploring, respectively, the conditions of possibility of cinematic representation in Africa (the opening sequence), historical dissonance through the dialectic of past and present (the post-credit sequence), a flashback to the eve of African independence (the imaginary garden party sequence), the predicaments of the post-colony, an assessment of the living condition of migrant workers and the actions taken to transform these conditions, and a final sequence in a circular mode, which returns to the new cinema.

Thanks in part to these recent restorations, Hondo has emerged as one of the giants of Pan African cinema.

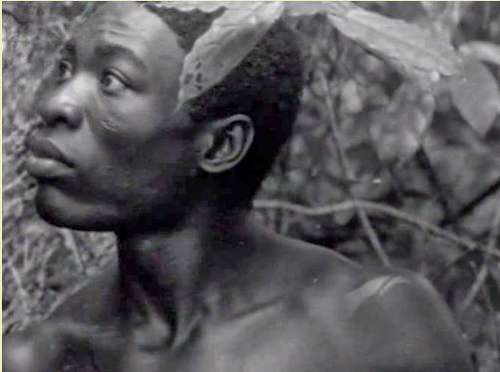

Muna Moto (1975, Cameroun)

Jean-Pierre Dikongué-Pipa was present to introduce this, one of the first films made in Cameroun. Though hampered by budgetary and censorship constraints, Muna Moto is an affecting story attacking both polygamy and the dowry tradition. The basic premise is that for any man in this culture, fathering a child is of prime importance, more than his love for any of his wives.

The protagonist N’gando, a poor, hard-working young man (see top image), aspires to marry N’Domé, a woman who genuinely loves him. The high dowry necessary to arrange such a marriage, however, presents a nearly insuperable barrier. While N’gando struggles to raise the money through low-paying manual labor, his rival, the wealthy M’bongo, who already has three wives who have failed to give him a child, takes the woman as a fourth wife in the hope of conceiving a baby.

She is already pregnant by N’gando, however. (The title translates as “Another’s Child.”) The film becomes a struggle in which N’gando tries to kidnap the baby girl.

The scene of the kidnapping opens the film, without explanation. Only gradually through flashbacks do we come to understand his motives and the tragedy of the situation. Muna Moto effectively uses the flashback conventions of European art cinema (Dikongué-Pipa had studied at the Conservatoire indépendent du cinéma français in Paris) to tell a thoroughly indigenous story with beautiful black-and-white cinematography.

The Cineteca di Bologna’s L’Immagine Laboratory restored the film in 2019 with the support of The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project. Ideally this will make the film widely available on home video and for viewing at festivals.

Le retour d’un aventurier (1966, Niger), Samba le grand (1977, Niger), and Kokoa (2001, Niger)

Moustapha Alassane directed about two dozen films, mostly shorts. He is credited with being one of the few major African directors who was completely self-taught in filmmaking. Three of his shorts were shown in one program. Le retour d’un aventurier suggests how foreign cultures adversely affect regions of Africa. A popular young man from a village returns from a trip abroad, presenting his friends with six-shooters and cowboy outfits.

At first these would-be cowpokes seem ludicrously out of place, and yet when they begin to terrorize their peaceful village, their violence becomes all too familiar.

Alassane was a pioneer of African animation. His Samba le grand, the first color animated film made in Africa, combines hand drawings and simple cloth dolls to tell a traditional African folk tale effectively.

The most engaging of the three films on the program was Kokoa, a more elaborate and sophisticated cartoon. Using puppet animation, Alassane presents a traditional Niger-style wrestling match among frogs and lizards, with a sideways-moving crab hilariously mimicking the typical movements of a referee (above).

Baara (1978, Mali)

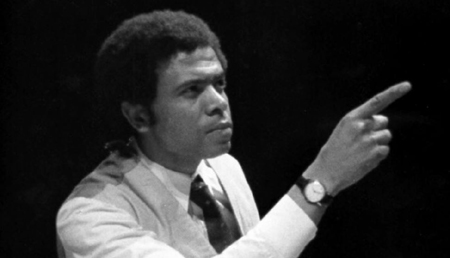

One of the most revered African directors, and certainly so among those living, is Souleymane Cissé.

Cissé was present for a Q&A session after the film. He was forthright in declaring that the somewhat faded print shown was too pink and that he would rather have had it destroyed than shown publicly. Cenciarelli assured him and us that it was the best 35mm print available, and audience members declared themselves delighted to see the film even in a less than ideal copy. Cissé stuck by his opinion and pointed out that the original negative survives intact in Paris. Ideally a restoration comparable to the ones shown in this series will someday be done.

He also mentioned that although he was jailed for accepting French funding for his first feature, Den Muso (“The Girl,” 1975), he still does not know the real reason for his arrest. He wrote the screenplay for Baara (Work) while in jail.

The film tackles the issue of the rise of a working-class in a country that had been largely rural and agriculturally based. The central figure is an uneducated young peasant who comes to the city and works as a porter. His cousin, educated and westernized, attempts to help him but is himself oppressed by the corrupt company officials above him. (Both are seen in the image above.) Unlike many other African directors who went abroad to study filmmaking, Cissé attended VGIK in Moscow (as did Sembene). Possibly the experience accounts for the narrative’s distinctly Marxist tone.

For more on Baara, see Richard Brody’s review on the occasion of a recent screening of the film at the New York African Film Festival.

La petite vendeuse de Soleil (1999, Senegal) and Le franc (1994, Senegal-Switzerland-France)

Earlier this year I reported on the showing of a restored print of Djibril Diop Mambéty’s, Hyenas (1992), at the Wisconsin Film Festival. After Touki Bouki (1973), it was the second of two full-length features Mambéty made before his early death at the age of 53. He followed Hyenas with the two short features (45 minutes each) from an intended trilogy entitled Contes des Petites Gens. The pair were shown together at the festival.

La petite vendeuse de Soleil (The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun) is perhaps Mambéty’s greatest film, though it is difficult to be objective given the utter charm of its central character, along with the performance of Lissa Balera in the role of Sili. Looking past that, though, the film is beautifully shot in locations in and around Dakar, and the narrative unrolls with a calm surety that packs a great deal into a short length.

Mambéty establishes the initial setting in the outskirts of Dakar in a leisurely fashion with dawn shots of the poverty-stricken area. We glimpse Sili limping past the hovels of the suburban slum, though we see other marginal figures as well–including a man pounding large pieces of stone into gravel. The planes taking off and landing behind him establish the theme of poverty juxtaposed with the modern, wealthy society of the city.

Soon we become attached to Sili as a friend takes her into the city to beg. She notices boys making money selling newspapers and soon becomes the first female to become a newspaper seller. Through a fluke of good luck, a wealthy man who sees her as a sign of African progress gives her a large bill to buy all her papers. Immediately confronted by a policeman over the large bill, she defiantly leads the way to the police station and talks the chief into releasing her and a woman charged with theft without reason. Once freed, she celebrates her good fortune by leading a cheerful dance in the street (above) and treating her friends to sodas.

She buys her blind grandmother a large umbrella to shade her as she sings for a living, and she gives small coins to her fellow beggars. Her generosity endears her to a seller of the rival newspaper, who becomes her defender. Her cheerful resilience persists despite bullying by a gang of rival newspaper sellers.

The film combines a realistic view of the grim life of street people in Dakar with a vision of hope represented by Sili. At the end, Dembéty dedicates it to the city’s street children.

Le petite vendeuse de Soleil was restored in 2019. Ideally, the currently available prints, with their somewhat soft images, will be replaced with this impressive version.

The second film in the series, Le franc, is not as engaging. It centers around Marigo, a shiftless man who is beleaguered by his landlady for back rent on his simple shack. He purchases a lottery ticket and, to prevent its loss, glues it to the shack’s door. When the ticket wins, he carries the door to the lottery agency, only to be told that a number on the back of the ticket is essential to allow him to collect the money. The main action is mainly extended slapstick as Marigo clumsily carries the door, frequently falling or dropping it. It’s an entertaining film but lacks the depth of La petite vendeuse du Soleil.

La femme au couteau (1969, Ivory Coast)

Timité Bassori’s La femme au couteau (“The woman with a knife”) is the earliest of the feature films shown at this year’s festival. Like numerous other directors from the continent, Bassori studied at IDHEC in Paris. The influence of 1960s European art cinema seems stronger in this film than in the others in this program.

The story is entirely based around the psychological problems of a young, unnamed, westernized man, whose romance with an unnamed woman is hampered by his disturbing hallucinations of a woman threatening him with a knife. Deciding to avoid traditional African cures, he finally is committed to a mental institution. Ultimately he recalls the trauma that had triggered his psychological problems. The film is skillfully made, with Bassori memorable as the protagonist, but it seems the kind of story that could have been made in a European country as well as an African one.

The excellent print was a product of the African Film Heritage Project, a program within the The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project; it was restored at the Cineteca di Bologna in 2019.

Wend Kuuni (1982, Burkina Faso)

This classic film was restored in 2017 by the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique. In his introduction, archivist Nicola Mazzanti expressed bitterness that Wend Kuuni has been neglected by distributors and exhibitors for decades. This new print should give it the second life that it richly deserves.

As Mazzanti pointed out, this is one of the few African films that portrays the continent as it was before colonialists invaded and changed the local culture forever.

The film follows the story of a mute orphan who is discovered nearly dead and taken in by a local farmer. (The title translates as “God’s Gift” and is the name bestowed upon the boy by his adoptive father.) Rather than develop a straightforward drama of the boy’s character arc, director Gaston Kaboré (who collaborated in the restoration) creates what is nearly a documentary on traditional rural life. We see the young protagonist herding sheep, the women of the family grinding grain, and so forth. Any progression in the plot takes place at wide intervals. The orphan’s origins and the reason for his muteness remain lingering mysteries but are not much dwelt upon until late in the film, where flashbacks and a traumatic discovery restore his voice and reveal his past.

Probably coincidentally, these two films about trauma and recovery through the recognition of a disturbing event in the past were shown back to back. But while La femme au couteau calls upon modern notions of psychology, Wend Kuuni simply presents the boy’s muteness and eventually shows his recovery without any reference to psychological concepts.

I am happy to say that some of these African films featured in our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, from its earliest edition in 1994: Les Bicots-Négres, vos voisins; Muna moto; and Wend Kuuni. We also discussed other films by Cissé and Sembene. At the time, few of these films were available for screening. It is encouraging to see such films revived and disseminated more widely.

Baara (1978).

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.