Archive for the 'Silent film' Category

Hark! How Harold’s angels sing (a repost)

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1094 entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed.

Movie fans may want something a little offbeat relax with at home, so we thought that in these turbulent times, classic comedy would be welcome. We’ve picked a 2017 entry to revive (and slightly revise): “The Boy’s Life,” devoted to Harold Lloyd. (He certainly had the holiday spirit; he’s said to have kept a Christmas tree up, complete with presents, all year round.) We still think he rewards our interest, and families and cinephiles ought to find his films fun. This entry introduces Girl Shy, still running on The Criterion Channel, with DB’s discussion included there. The blog entry refers to other Lloyd movies, all of which are on the Channel and some of which are also available on the TCM wing of Max (but not, alas, Girl Shy).

Warm holiday wishes from the two of us!

DB here:

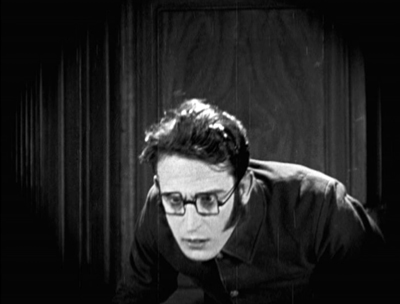

On 9 September 1917, film history changed for the better. That was when we got the eyeglasses.

Their circular, horn-rimmed frames stood out as wire rims would not; besides, horn rims had become fashionable for young people. These specs held no lenses, but so much the better. Reflections from studio lights would have hidden the eyes of the winsome, earnest, clueless young man usually called the Boy.

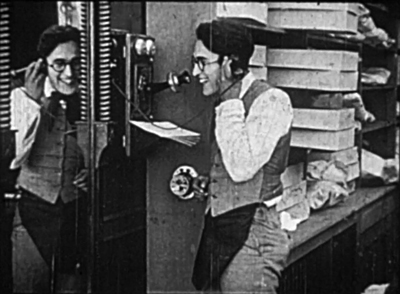

In Over the Fence, the film introducing him, he’s already amiable, a little vacuous but delighted to be talking to his girl on the phone and watching himself doing it.

Harold Lloyd had already featured in some sixty-five short comedies from 1915, playing characters called Willie Work and Lonesome Luke. Even after introducing the Boy, Lloyd continued with a few Lukes before phasing out this sad sack. No one expected that in a few years the glasses character would become world famous. Lloyd’s films were more lucrative in aggregate than those of any other silent comedian, and he became one of the central figures in Hollywood.

When our comrades at Criterion announced their plan for a centenary Lloyd celebration this month on FilmStruck, I suggested we devote an installment of our series to one of the films. Kristin and I have been Lloyd fans for decades. Fans and collectors kept his work alive. Kevin Brownlow had to remind people with his Lloyd documentary, The Third Genius (1989), that, well, Lloyd was a genius. The more you get to know his work, the better it looks, and the less plausible seem many of the clichés that have clustered around it.

One of the very best films to get to know is Girl Shy (1924). That’s the one analyzed in the latest Observations on Film Art episode on the Criterion Channel.

Man into Boy

For decades after sound came in, American silent comedies dropped mostly out of sight. Some 16mm copies were available in cut-down rental versions, and a few were circulated by the Museum of Modern Art Film Library. (Of Lloyd’s work, that included only The Freshman of 1925.) The MoMA canon became the canon. In the 1970s, thanks largely to piracy, the films of Keaton were added, and still later we came to recognize Charley Chase, Max Davidson, and other talents.

Throughout these years Lloyd’s films were almost invisible because he controlled the rights to them and limited their circulation. Kept in vaults in his rococo estate Greenacres, they would not reemerge until the 1960s, in cut TV versions distributed by Time-Life. Until fairly recently, most critics relied on memory of the films and the received image of the Boy dangling helplessly from the clock face.

Most of the sixty-one shorts featuring the Boy languish in archives, and some were lost in a fire on the Lloyd estate. But several two-reelers are readily available, as are all the longer films. What we have gives the lie to most clichés about this filmmaker.

Take the most persistent one. Socially conscious critics of the 1930s saw Lloyd’s work as naively reflecting the go-go 1920s. The Boy’s resolutely middle-class aspirations made him a crass avatar of complacency before the Crash. Chaplin seemed to stick up for the little guy, but Lloyd seemed to celebrate the striver; he compared himself to Tom Sawyer. It was all very neat. The Boy’s climb up the skyscraper in Safety Last could symbolize the heedless ambition of the white-collar worker, while the his efforts to fit in at college in The Freshman suggest desperate American conformity.

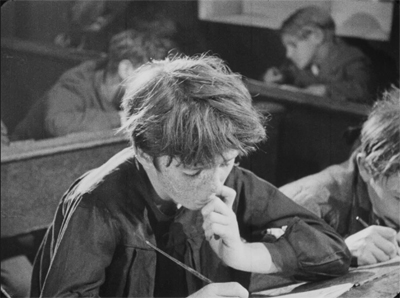

Those interpretations played down the fact that just as often Lloyd played hayseeds humiliated by city folk and con artists. In Girl Shy, the city slicker who wants the girl is a weasel, and Harold has to rescue her. Here, as often, the film is largely a procession of social humiliations. Lloyd, a predecessor of cringe comedy, in turn provided a model of embarrassment for Ozu’s silent films. Those films often feature students wearing the Boy’s glasses (below, Days of Youth, 1929). This isn’t mere imitation or homage; the glasses became a Japanese fashion item, called roydo, named after Lloyd. (Below, a photo from a student ski trip in the 1930s.)

More edgily, Lloyd also played foppish idlers, louche one-percenters who glide obliviously through the lower orders and need to learn humility. The original title of For Heaven’s Sake (1926) was to be The Man with a Mansion and the Miss with a Mission, a phrase retained in an intertitle. Here as elsewhere, the coddled Boy learns to help his social inferiors. If you’re after class-based critique, Lloyd films come out pretty well.

Likewise, there were the complaints that Lloyd’s comedy was mechanical. Chaplin was the poet and dancer. Keaton, in both concept and execution, showed himself a geometer, the dogged engineer of monumental effects more awe-inspiring than hilarious. Though granting that Lloyd, foot for foot, yielded more laughs than any of his peers, critics worried that he was only merely funny, a relentless gag machine. Here is James Agee, in one of the subtlest appreciations of silent cinema ever written:

If great comedy must involve something beyond laughter, Lloyd was not a great comedian.

But immediately, as an honest man, Agee must add:

If plain laughter is any criterion—and it is a healthy counterbalance to the other—few people have equaled him, and nobody has ever beaten him.

Still, Agee admits that Lloyd’s films pass beyond laughter in one respect. They offer harrowing suspense. What his audiences called “thrill comedy” remains chilling today. His antics on skyscraper ledges and girders still induce vertigo, and his car chases risk catastrophe on a scale that would worry Jackie Chan. Agee seems to grant that inducing shrieks as well as guffaws is no small accomplishment.

If Agee could have reviewed all the feature films, though, maybe his judgment wouldn’t have been so absolute. For example, Lloyd’s features take us beyond laughter in serious ways—into regions of vulnerability and inadequacy. The Boy is typically given a fault: cowardice (Grandma’s Boy), self-absorption (as hypochondria in Why Worry? and as self-indulgence in For Heaven’s Sake), lack of confidence (The Kid Brother), neurotic extroversion (The Freshman). In several films, the seriousness undercuts the comedy.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold can’t drive away the tramp, but Granny can do it easily, with some swipes of her broom. Our laughter is cut short when, in the space of a cut, as she calmly returns to the porch, we see the Boy slumped over, his head in his hands.

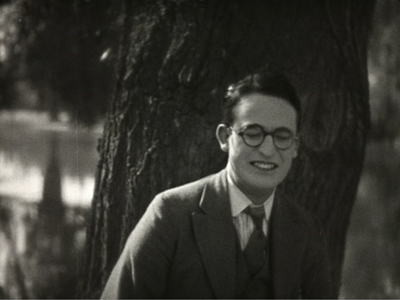

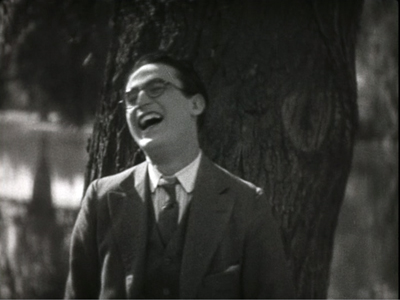

Soon he will admit that he’s a coward. Lloyd films switch their tone on a dime, shifting between comedy and drama breathlessly. In Girl Shy, the Boy not only dumps the girl he loves but does so by cruelly laughing at her trust in him. (Agee: “He had an expertly expressive body and even more expressive teeth.”) Wobbling and shifting his weight, Harold breaks the laugh with a gulp before carrying on his bluff.

Nothing in Keaton or Chaplin makes us as ashamed of our hero as we are right now. Soon he will do something worse.

This passage reminds us that Lloyd worked his face for all it was worth. Keaton had more expressions than he’s usually credited with (bewilderment, concentration, doggedness); it’s just that he doesn’t smile. Chaplin inherited the white-face clown tradition and often favored deadpan. He limited his facial reactions to squiggles and flashes, often no more than a skew of the mouth or hauteur in the brows, with an occasional embarrassed giggle. With Chaplin, the body expresses nearly everything, as befits an aesthetic predicated on the long shot.

But Lloyd, relying on medium shots, performs as a dramatic actor, with a wide repertory of expressions. Agee refers to his “thesaurus of smiles,” but he had other resources, as this Girl Shy scene attests. His producer Hal Roach is said to have remarked: “Harold Lloyd was not a comedian. But he was the finest actor to play a comedian that I ever saw.”

Another nuance: Comic laughter comes in many varieties. Like Keaton, Lloyd celebrates winning through tenacity and resilience. If we gasp at the geometrical audacity of Keaton’s humor, we’re buoyed by Harold’s righteous settling of accounts. It’s reported that audiences actually leaped up and cheered at the climaxes, when bullies and rascals were punished at delectable length. These are comedies of comeuppance and payback, outcomes universally enjoyed and still much in demand today.

Point the last: Neatness of construction. Chaplin’s films are lovably episodic; I still marvel that films that took so long to make are so loosely put together. Keaton by contrast is a metronome-and-protractor director, aiming to make every shot and sequence and reel sit in meticulous order. No one but he could have conceived the marvel of symmetry that is The General, or, on a lesser scale, Our Hospitality and Neighbors.

Lloyd’s films are no less finely put together, as many recognized at the time. A Film Daily review of The Kid Brother (1927) noted: “Lloyd and his gag-men again have devised a corking set of comedy situations that fit consistently into a well-joined plot and laughs keep building from little chuckles to hilarious roars.” Orson Welles praised “the construction of Safety Last, for instance. As a piece of comic architecture, it’s impeccable. Feydeau never topped it for sheer construction.”

To get a little more specific, I think that Lloyd’s model was the well-made dramatic film, the tight classical plot. This is the argument I make in the Girl Shy installment. I try to show that in this, his first film as an independent producer, Lloyd applied the emerging model of Hollywood narrative to feature-length physical comedy. Fairbanks had moved in this direction, and Lubitsch would achieve something similar with social comedy in The Marriage Circle (1924) and the masterpiece that is Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

Lloyd was a pioneer in showing how everything that worked for serious dramaturgy could work for comedy too. Girl Shy gives us a goal-oriented protagonist who has a serious flaw. Going beyond the figures of slapstick, we get access to his psychological yearnings and frustrations. His loneliness and fear of women fuel overwrought fantasies of domination. The Boy is caught up in the characteristic Hollywood double plot, involving love and career—two lines of action that usually block and deflect one another.

This linear action is deepened by a series of motifs. They’re simple in themselves (a stammer, a Cracker Jack box, a dog biscuit box), but they’re worked out with a pictorial and dramatic intricacy that’s rare at the time. And it’s all topped off by a two-reel chase that is simply one of the greatest ever put on the screen. At a time when every superhero blockbuster ends with a big action sequence, it’s worth seeing one that’s both graceful and hilarious, and it owes nothing to special effects.

Girl Shy shows how rewardingly complex silent Hollywood storytelling could be. It reveals Lloyd as a master craftsman of cinematic resources—dramatic, pictorial, emotional. He saw how to make a movie that would be engrossing even without the gags. The comedy deepens a powerful dramatic premise that moves forward with an organic, not mechanical, energy, and it’s developed in funny or poignant detail at every instant.

Filling the format

In the arts, form often follows format. The fourteen-line sonnet, the tondo painting, the twenty-two-minute sitcom, the nine-panel comic-book page: all provide the artist with a set framework within which to create. When Lloyd started out, film reels in the US were standardized at 1000 feet, which typically ran between twelve and fifteen minutes, depending on projection speed. Short films, particularly comedies, were either one or two reels, while features–dramas, mostly–ran four, five, or more.

The task of the filmmaker was to build a story that would fit the format. The temptation was padding. Griffith, for instance, often filled out his shorts with “goings and comings,” shots of characters leaving one place and making their way to another, sometimes across several shots. But once padding was inserted, filmmakers could make it engaging. Griffith did this by embedding the goings and comings in suspenseful situations, so that the travel shots served as dramatic delays. Mack Sennett needed scenes to lead up to a big chase (the “rally”), but those scenes could themselves have a linear logic, as with romantic rivalry or street quarrels.

Lloyd became very sensitive to film length. He knew that his initial popularity depended on the fact that Pathé and producer Hal Roach spit out a Lonesome Luke every week or two; he saturated the market. Even after Luke appeared in two-reelers, Lloyd wanted his new character, the Boy, to start in one-reelers. He recalled telling Roach, in sentences as breathless as the pace of a one-reeler:

Now, I’m getting started in a new character and you want people to get used to the character, you want them to see the character; and besides, if you make a poor, or mediocre, or moderately good, or even a bad picture in a two-reeler, it’ll kind of tend to sour the people on you because they won’t see another one for a month. But if I make one-reelers, we’ll get one out every week, so if a couple of them are not so good, and the third one is, it will cover up the other two, and besides it will keep you in front of the public.

As a result, Lloyd spent two years turning out an astonishing eighty-two one-reelers. Not until Bumping into Broadway (2 November 1919) did he launch a two-reeler featuring the Boy.

There’s evidence that Lloyd’s awareness of the niceties of running times went beyond a concern for building the brand. He understood that form and format had to mesh. His early one-reelers relied largely on the standard episodic knockabout. We’re given a defined situation, such as a modernized hotel (The City Slicker, 1918), a western saloon (Two-Gun Gussie, 1918), or a vaudeville theatre (Ring Up the Curtain, 1919). In this situation, the characters quarrel, pull pranks on one another, engage in fistfights, kick each other in the pants, and usually wind up in a chase. A string of gags might emerge, as when a stray snake terrifies the theatre troupe in Ring Up the Curtain, but the gag is quickly exhausted, and we go on to the next bit.

Once Lloyd settled on two-reelers, he built them up more carefully. He scaled, we might say, his plots and gags to a fairly tight, logical development in the fuller format. Part of that development involves what we might call nested gags. In Captain Kidd’s Kids (1920), the first part (roughly one reel) sets up Harold as a playboy recovering from a bachelor party. In his elaborate bathroom, he tips back his chair, leading us to expect him to fall in. But no: instead his butler, Snub Pollard, dumps ice in the pool.

There follows a string of shaving gags here and in the next room. Early in this series, Harold drips shaving cream in his morning tea; but after other gags he comes to drink it and finds it foul-tasting. Then he returns to the bathroom, tips back the chair again, with results we’d expected several minutes before.

Now we get some elaborate efforts to rescue Snub. The gags are simple, but by setting up one and then moving to set up and pay off others before returning to the first, Lloyd and his team avoid the start-stop-restart pattern than we find in many one-reelers.

The real plot action, of course, doesn’t get going until the second reel of Captain Kidd’s Kids, but Lloyd has provided some lively padding to start. Now or Never (1921) shows the same gag-braiding, with the recurring appearance of two drunks on the train ride that constitutes the bulk of the film.

Lloyd moved toward longer films cautiously—first to three reels, then four (A Sailor-Made Man, 1921), then five (Grandma’s Boy and Dr. Jack, 1922). He always said that most grew organically, beginning as two-reelers and then expanding when the story premises and gag sequences developed. To keep things in proportion, he tested the results on preview audiences, then reshot and recut his footage. The preview responses to one three-reeler, I Do (1921), convinced him to lop off the entire first reel. Although he had increased confidence in his ability to scale up, when he signed a new contract with Pathé in early 1922 he insisted that the company publish a notice to exhibitors declaring that film length would be

strictly governed by the character and quality of the material evolved in the production development of each subject—which means that the Lloyd standard of excellence is to be maintained first of all; a given story that turns out to be adequately filmed in two reels will be confined to two reels, and so released. This is a principle cherished by Lloyd himself.

Lloyd could be so confident because even his shorter releases were becoming the top-billed item on programs across the country. He was, in effect, returning the idea of “feature” to its original meaning—not simply a long film, but rather a movie that could be “featured” in publicity. He was also announcing his unusual concern for tight form.

Comic architecture

Grandma’s Boy (1922).

Lloyd moved to features in synchronization with his peers. Keaton was the first, with The Saphead (September 1920), though it’s less a comedy than a light drama; and Keaton returned to making two-reelers for three years. The Round-Up (October 1920) gave Fatty Arbuckle a comic role in what was basically a serious drama. Arbuckle starred in The Life of the Party (December 1920), another light drama with almost no physical comedy. Chaplin’s The Kid (February 1921), at a bit more than five reels, might be considered the first slapstick feature since the one-off Tillie’s Punctured Romance (1914, six reels). The émigré Max Linder got into the act with two 1921 features, Seven Years’ Bad Luck (May 1921) and Be My Wife (December).

It might seem that Lloyd was a bit late with the four-reel Sailor-Made Man (December 1921). But that film capped his most extraordinary year to date, with four earlier films released in spring, summer, and fall. Along with six two-reelers released in 1920, Lloyd was now a major comedy star, and the Boy could carry a longer story.

But how to do that? His peers explored some options. In Arbuckle’s two features, it’s his physical presence that matters, not consistency of character; in one he’s a genial sheriff, in the other a lawyer inclined toward crookedness. Chaplin retained the Tramp persona in The Kid, but the film is a rather episodic affair. Once the main plot is resolved, a reel pads out its length with a dream sequence set in heaven. The Linder films are lively but digressive, with plots propelled by casual pranks and lovers’ misunderstandings.

By contrast, Lloyd’s features moved toward tight construction. Despite his claim that his films just grew longer accidentally, they were shaped in ways that make them seem through-composed. His comedy sequences are deftly prolonged, building and topping themselves with great speed. Gags are embedded and interwoven in ways that yield surprises, and motifs set up early in the film pay off later. We may have forgotten about them, but Lloyd hasn’t.

Lloyd’s obsession with overall form can be seen in his use of the “Lafograf,” a kind of EKG of viewers’ response at previews. Coders sat in the audience with pencil, paper, and stop watches to note every bit of amusement, from a titter to a screech. Once graphed, the entire movie displayed laughs big and small throughout, with most of the big ones spiking in the last reel.

A powerful demonstration of Lloyd’s skill came in his first five-reeler, Grandma’s Boy (1922). Chaplin called it “one of the best constructed screenplays I have ever seen on the screen.” Lloyd began it as a two-reeler, but after expansion it had become more drama than comedy. Roach urged him to add more gags, and the result is a remarkable balance between humor and pathos.

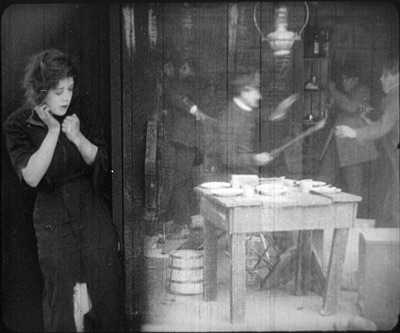

That mixture is given from the start in a prologue showing a baby Harold, glasses and all, bullied by another baby. Then the Boy as a boy is picked on and made to put a chip on his shoulder.

This last bit will pay off fifty minutes later. The rival, the little bully grown up, taunts Harold, not knowing Harold has captured the prowling tramp and proven his courage.

The upshot is a fight that knocks the stuffing out of the Bully. In the course of that fight, another moment calls up a contrast with an earlier scene. The day before, the Bully has pitched Harold into the well; now, after the Rival tries a foul blow, Harold administers payback.

These distant echoes can be very satisfying.

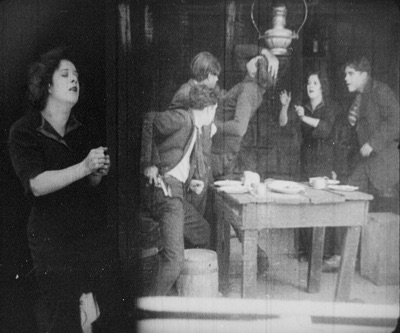

The organization of gags is likewise remarkably sustained. Walking home from his well dunking, Harold finds that his one suit has shrunk grotesquely. But the Girl has invited Harold to her home for an evening, so he needs another suit. Granny digs out his Grandpa’s suit, 1862 vintage. (The peddler said it was unique.) It still has mothballs in it. Granny also finds there’s no shoe polish, so she uses goose grease instead. These bits become the basis of a steadily building gag situation in the Girl’s parlor.

But not right away. First Harold arrives and discovers that his vintage outfit is matched by that of the butler. Another echo, when he mutters: “That peddler lied to Granny!” He sits to listen to the Girl play the piano, and gets his finger caught in a vase. Only now does one of the earlier gag setups start to pay off. A cat comes to lick his tastily greased shoes.

The grown-up Bully was introduced throwing a stick at a cat, but Harold is more gentle. He nudges the Girl’s cat away, but soon a troupe of cats enters to converge at his feet.

He has to dispose of them without the Girl’s noticing. Finally, when the couple move to the settee, the cats reconnoiter and the gag sequence pays off: Harold uses a statuette of a bulldog to scare them away.

Cozying up to the Girl, Harold ought to be in clover, but now she smells something—his suit. Investigating, he finds mothballs that he and Granny failed to remove. I’ll spare you more description. You can watch what happens next, including a new confrontation with the Rival. And again, Harold gives us an unforgettable suite of facial expressions.

Lloyd’s pacing allows just enough time for us to anticipate what might happen at each turn of events. Structurally, while Lloyd is developing and paying off the IOU of the mothballs, he wedges in a fresh setup, that of the neighbor kid’s requesting some gasoline. That becomes the topper for the mothball series, as the dog statuette topped the cat gags. This sort of braiding of gags, weaving the setup of one gag into the development of another, shows how a feature can be built out of quasi-melodic lines, like a song.

Even more important is the presentation of the protagonist. Lloyd gives his hero what modern screenwriters call a character arc. In the early 1920s Lloyd began to distinguish between gag pictures and “character pictures,” in which the story line depends on our concern for the protagonist.

In his short films, Harold had an established image, but his characterization varied a lot. Sometimes he was a good-natured everyman, but he could also be a scrapper, a hustler, or a ne’er-do-well. And his romantic relations with Bebe Daniels were wonderfully flirtatious; in one she helps him count bills by licking his thumb. In the features, Harold was given a more definite character, one with a pronounced fault. He was often insecure, awkward, and oblivious, qualities that led critics to call him a boob. The insult is referenced in Girl Shy, when his book gets mocked as The Boob’s Diary. Correspondingly, the romance plotline of his films became much more fraught.

In Grandma’s Boy, Harold’s fault is cowardice, and he must keep the Girl from finding it out. His impulse is to hide from the world, but Granny inspires him with the tale of how his Grandpa overcame his fears and helped the southern army win the war. He did it, she says, thanks to a Zuñi charm given him by an old woman.

Now Grandma gives Harold the charm, and his faith in it enables him to capture the murderous thief. In a double climax, Harold, still clinging to the charm, is able to beat the Bully in a drag-out fistfight.

Of course the action is packed with delays, detours, and surprises. The capture of the thief is a superb flow of gags, from Harold braving the tramp’s hideout to a long chase, in which the talisman does duty as a pistol barrel. And the fight with the Bully gets expanded when Harold loses the charm and turns suddenly meek. After the fight, the topper comes when Granny reveals the real source of the charm’s power. Harold comes to understand that he has inherent reserves of courage.

Nicholas Kazan once observed: “You want every character to learn something. . . . Hollywood is sustained on the illusion that human beings are capable of change.” This principle of construction goes very far back, and it became the basis of Lloyd’s feature plots. We get not just a change of fortune (and so a happy ending) but a change in personality (and so a happier one).

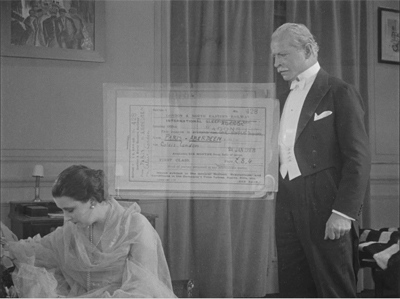

From Grandma’s Boy onward, Lloyd’s features display disciplined, inventive construction–at the macro-level of plot and at the mid-range of gag sequences, down to precise shot-by-shot articulation of the action. Here’s a moment when Grandpa (he wears glasses too) sees, reflected in an inkstand lid, a Union officer preparing to clobber him.

Since the Bully is reincarnated in the Union officer Harold outwits, this flashback quietly prefigures the Boy’s victory over the Bully at the climax.

In my Criterion Channel presentation, Girl Shy serves as another example of how Lloyd brought classical construction to comedy. I could as easily have picked another superb item, The Kid Brother. Maybe next year?

It seems likely that Lloyd’s work became a model. Keaton’s trimly carpentered second feature Our Hospitality (1923) is in the same vein. And Chaplin, after he praised Grandma’s Boy, went on to declare: “The boy has a fine understanding of light and shape, and that picture has given me a real artistic thrill and stimulated me to go ahead.” Lloyd and the Boy, glasses and all, remade Hollywood comedy in important ways, and in the process they gave us wonderfully exuberant films.

Thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, and their team at Criterion. Thanks as well to Jared Case of George Eastman House for information about their print of Never Weaken.

Lloyd’s autobiography, An American Comedy, was timed to the 1928 release of Speedy, and it’s full of detail about gag structure and the production of his films. At one point he transfers our old friend, the distinction between suspense and surprise, to comedy. The book includes Frances Marion’s memorable line, “Harold, you’ve got to lose your pants.” Coauthored by Wesley Stout, An American Comedy was reprinted in a sturdy Dover edition with a 1966 interview and a cliché-challenging introduction by Richard Griffith.

Lloyd has been lucky in his admirers. Richard Schickel’s Harold Lloyd: The Shape of Laughter (New York Graphic Society, 1974) yields a finely sustained appreciation of his art. Adam Reilly’s Harold Lloyd: The King of Daredevil Comedy (Collier, 1977) is a vast compendium of biography, plot synopses, and visual documentation. Tom Dardis’s Harold Lloyd: The Man on the Clock (Viking, 1973) is a careful biography that situates Lloyd’s career in the development of the film industry. Donald W. McCaffrey offers a comparative study of plot structure in Three Classic Silent Screen Comedies Starring Harold Lloyd (Associated University Presses, 1976).

Most comprehensive of all is the remarkable Harold Lloyd Encyclopedia (McFarland, 2004) by Annette d’Agostino Lloyd (no relation). All the films are synopsized with credits and items from trade papers. Her Harold Lloyd: Magic in a Pair of Horn-Rimmed Glasses (BearManor, 2009) is full of fan enthusiasm, shrewd observation, and information I couldn’t find elsewhere. (She even checked Lloyd’s FBI file.) My Welles quotation above comes from this book, p. 167, as does Harold’s explanation of starting the Boy in one-reelers (pp. 85-86). The indefatigable d’Agostino Lloyd earlier produced Harold Lloyd: A Bio-Bibliography (Greenwood, 1994).

The Agee essay is of course “Comedy’s Greatest Era” from 1949. My quotations come from James Agee, Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, and Manuscripts, ed. Charles Maland, vol. 5 in The Works of James Agee (University of Tennessee Press, 2017), p. 883. My Chaplin quote comes from Dardis’s biography, page 112. The quotation from Nicholas Kazan is in Jurgen Wolff and Kerry Cox, Top Secrets: Screenwriting (Lone Eagle, 1993), 134. Lloyd’s movie-measuring scheme is explained in P. A. Thomajin, “The Lafograf,” American Cinematographer (April 1928), 36-38, as applied to The Kid Brother, online here. The graph for Speedy is reproduced in Reilly’s Harold Lloyd, pp. 106-107.

A very pretty collection of early Lloyds is on Vimeo from Random Media. The standard DVD assemblage of features and shorts is the multiple-disc Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection. Several of these films are streaming on the Criterion Channel. Unfortunately, the version of Never Weaken (1921) available in these collections is a 1925 re-edit of the original three-reeler. The full version survives, however, and is available, in a so-so video, here. Criterion also offers an excellent Blu-ray disc of Speedy (1928), with solid extras, including an essay by Phillip Lopate and a visual essay on the film’s New York locations by Bruce Goldstein.

I analyze Ozu’s strong debt to Lloyd in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, pp. 152-159.

For the trivia fanatics: I think Harold’s manuscript in Girl Shy is mocking a sensational movie of a few years before, Men Who Have Made Love to Me. This film, written by Mary MacLane, an early feminist and scandal-rouser, was based on her memoirs. The movie is laid out in six parts, each devoted to the seduction method employed by one of her suitors. The film is lost, but it seems likely to have been the target of ridicule in the Lloyd picture.

Girl Shy (1924).

Manual labors

The Tin Star (1957).

DB here:

Type “screenplay writing” into Amazon and you’ll get over 6000 hits. Some of those books will be biographies of writers or screenplays of released films. But there’s still a huge number of DIY books with titles like How to Write a Movie in 21 Days and Writing Screenplays That Sell. A lot of people are apparently only one manual away from a finished script.

Screenplay manuals trigger suspicion. Can it really be that easy? Wouldn’t this be a paradise for grifters? A successful writer would hardly share trade secrets, so most of these books would be written by losers and wannabes. And if you read enough of the manuals, you’ll see the inevitable repetition of banalities. Make your protagonist “relatable.” Keep the conflicts going. Try for a twist.

Reading through them can be mind-numbing, but if you’re interested in how filmmakers tell stories, sometimes they can open up your thinking. Or so I’ll argue.

DIY scripting

The tide of manuals rose during the 1910s, when the emerging American studio system was seeking talent. The tide subsided between the 1930s and the 1960s, when screenwriting was contract labor in that system. But as filmmaking turned “independent,” ambitious people outside the industry could break in with an original script. Manuals, most famously Syd Field’s Screenplay (1979), began to pop up, and the market for how-to books expanded. Field’s book remains in vigorous circulation today, among many competitors.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

If your research touches on matters of style, you may find it illuminating to study the way practitioners pick solutions to practical problems. Which is to say that the manuals can point us toward norms. Norms are, I’ve argued, like a menu of more and less preferred options for treating the material. We developed this angle of inquiry in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, and now it seems well-established that the manuals can sometimes point us toward tacit norms of construction or visual style. For examples of how this can work, see Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood, my The Way Hollywood Tells It, and Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir. Many of our blog entries have also explored these paths. With screenplay manuals, we just have to be particularly careful to distinguish valuable data from bilge–which means checking the manual’s precept against many films.

And we shouldn’t expect the manuals or professional journals to identify every normalized device. For example, screenwriters now love to start scenes with friends greeting one another with “Hey” and “Hey,” but I doubt that there’s an explicit decision to avoid “Hi.” Similarly, I’ve never found anyone writing in the classic era who mentions the common Hollywood device of the double plot, with one line of action devoted to a goal-oriented activity and another, interdependent one devoted to heterosexual romance. Even the rather elaborate 180-degree classical editing system wasn’t apparently spelled out anywhere; it was learned by imitation and reinforced because it was economical and efficient. People can learn and follow rules that are simply taken for granted as “the way we do things.”

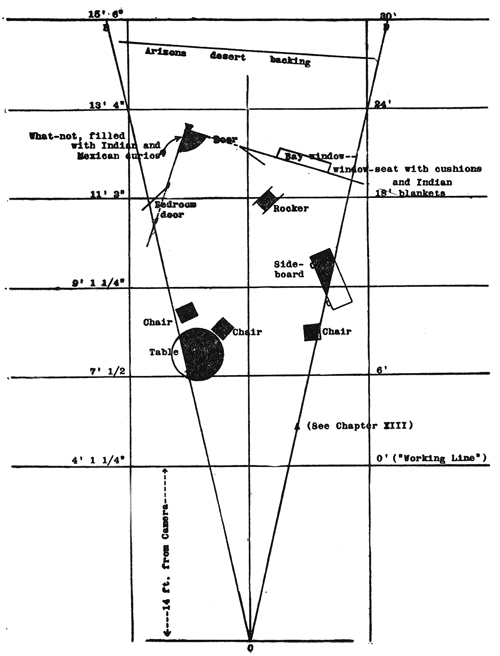

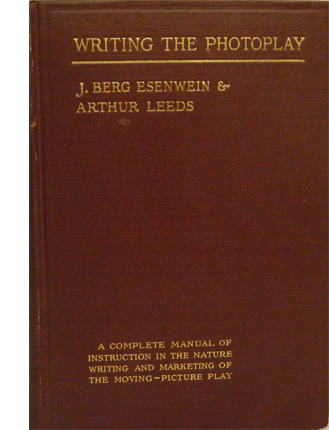

I think my soft spot for the manuals owes a good deal to my long-term affection for one item I saw in a 1913 guide. J. Berg Esinwein and Arthur Leeds’ Writing the Photoplay contains a lot of hints about standard practices of the period, but one of their diagrams changed my basic attitude about silent film technique.

The cinematic stage

In the late 1990s I became interested in the norms of scene staging in early film. I assumed that filmmakers had to call attention to story action without benefit of cutting to closer views, so I tried itemizing in a straightforward way the staging choices that could guide the viewer’s eye.

Many of the choices could be called “theatrical.” Lighting and setting could emphasize an actor’s gesture or facial expression. Performance factors operated as well, especially since actors were typically facing the viewer. Filmmakers’ reliance on these cues seemed to confirm the standard impression that early film was less “cinematic” than what came later.

Yet there were purely pictorial factors in play as well–notably, the placement of figures in the overall image. Composition of the frame, as in painting (and theatre) played a crucial role in guiding our attention.

There was something else. I was fascinated, for reasons sketched here, with the depth that many scenes in “tableau cinema” displayed. Here’s a quick example from Alfred Machin’s Le Diamant noir (1913). The entire film is available from the Belgian Cinematek.

The young secretary Luc is accused of stealing the missing diamond. He protests his innocence, but the accusation will force him to leave the country.

All the cues I’ve mentioned are at work here: centered figure placement, frontally facing characters, attention-grabbing gesture, favorable setting (the rear doorway and curtains highlight Luc’s arrival), and so on. In addition, a tunnel of information bores through the frame, leading from the distance and culminating in action in the foreground.

But this tunnel couldn’t fairly be considered “theatrical,” since if the action were played on a stage, not all viewers would have the optimal view presented in the shot. Most of the audience simply couldn’t see this alignment of players. Theatrical staging tends to be lateral and fairly shallow, so that people sitting in different seats can all see the scene. A good part of planning a stage production is calculating sightlines. But in film, there’s only one sightline, that of the camera lens.

We tend to see film space as cubical, a room with a missing fourth wall. Actually, the playing space–what Esenwein and Leeds call “the photoplay stage”–is a tapering pyramid whose point touches the lens. Because the film image captures an optical projection, the space is narrow but deep. The authors provide a diagram of a scene to explain. (For the sake of clarity, I’ve removed some of their annotations; the full version is on p. 160 of their book.) The effect is of wedge shape that carves into what would be the wide space of a theatre scene.

In 1910s cinema, the camera lens (at point 0) is assumed to be some distance from the “working line,” the layer of maximal attention. For some filmmakers this line was nine or eleven feet from the camera, rather than the 14 feet assumed here. The rest of the space falls away in the distance, and depending on the lens and lighting used, these areas can be in more or less sharp focus. Filmmakers of the period often marked out the pyramid on the studio floor so that actors would know when they were out of shot.

This diagram makes explicit many of our taken-for-granted notions about film space. Someone moving closer to the camera gets larger, of course; but the figure also blocks out more and more of the background as the pyramid narrows. An actor’s forward movement on the stage inevitably takes up a small part of the overall area, but in cinema forward-thrusting action can dominate the frame.

Just as important, the fixity of the lens makes it possible to choreograph actors with a precision impossible in theatre. Luc’s confrontation with his employer in my second frame gives him pride of place, but once he’s slumped at the foreground desk, he can move his head and clear the central zone for us to see a servant waiting in the distance. In tableau cinema, staging isn’t just “blocking.” It’s blocking and revealing, a constant flow of information presented through shifting arrays of figures. I provide several examples in the lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

My heightened awareness of the visual pyramid made me more sensitive to staging in all periods of cinema. We might think that after the tableau cinema period, when filmmakers became more dependent on editing, their reliance on the “photoplay stage” vanished. But of course every shot, close or distant, presents us with the visual pyramid, and some filmmakers relied upon it to provide the graduated layers of space in an edited sequence. Specifically, the “deep focus” that became a favored technique of 1940s cinema around the world would seem a modernization of the principles of the 1910s recognition of wedge-shaped playing space. Here’s an outrageous example from Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941), shot by Gregg Toland after Citizen Kane.

Less punchy imagery than this suggest that the skills of 1910s staging were never really lost. Another passage from Ball of Fire brings Professor Potts to the foreground in a way reminiscent of Machin’s film. Of course it helps when Gary Cooper is the tallest galoot in the scene.

Cinema’s visual pyramid becomes almost sadistic at the climax of Anthony Mann’s Tin Star (1957). The young sheriff stops a lynching by shaming the town bully. The bully responds as you’d expect, but not in the sort of shot you’d expect.

Mann’s earlier films had experimented with foregrounds thrusting out at the viewer, but this sequence carries the idea to a limit. The actor collapses against the camera, inadvertently proving how lines of cinematic sight converge at the lens–that is, at our viewpoint. Try doing this on the stage!

This entry is more a piece of intellectual autobiography than anything else. I doubt many other people were opened up to the intricacies of staging thanks to a diagram in an old book. I mean it just as an example of how reading manuals can set you thinking about the expressive possibilities of film, and taking you in directions that you couldn’t predict.

More recently, in writing Perplexing Plots, I poked into manuals for would-be fiction writers, an area that literary historians seem to have neglected. These manuals yielded a lot of principles of what people thought went into good storytelling. In particular, I found that while Henry James and Joseph Conrad were making arguments about viewpoint and chronology, so too were people writing how-to manuals. The books indicated a new awareness of these techniques among writers aiming at mass audiences.

Terry Bailey surveys and analyzes early manuals in “Normatizing the silent drama: Photoplay manuals of the 1910s and early 1920s,” Journal of Screenwriting 5, 2 (Jun 2014), p. 209 – 224. For a comprehensive overview, see Steven Price, A History of the Screenplay.

The main argument here is developed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

Ball of Fire (1941).

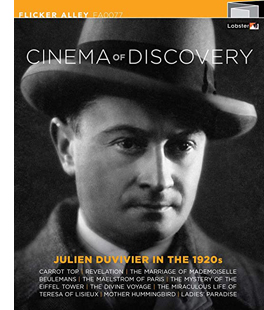

When the image ruled: Julien Duvivier in the silent era

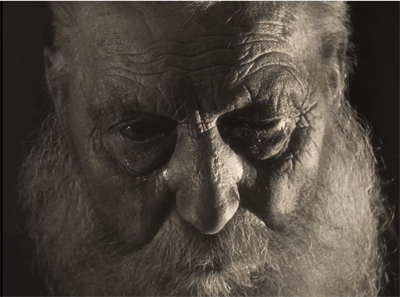

Maman colibri (Mother Hummingbird, 1930).

DB here:

Rewind the tape of film history. What if cinema had been invented as a perfect audiovisual medium, with images exactly synchronized with sound? What would the evolution of film form and style have been like?

Actually, Edison and other early inventors wanted sound to accompany the picture. Technical obstacles to sync sound initially proved too strong, and the fact that the public approved of the silent image led to a delay in fulfilling what André Bazin called “the myth of total cinema.”

It’s long been felt that this delay was a good thing for the artistic development of the medium. Perfect image/sound coordination would have led filmmakers to a line of least resistance, a simple reliance on recording what was taking place in front of the camera. The absence of dialogue forced filmmakers to develop techniques of visual storytelling. “The time of the image,” thundered Abel Gance, “has come!”

Some film techniques were borrowed from theatre and painting, but others became identified closely with the moving image. Techniques such as camera movement, analytical cutting, and rhythmic crosscutting, have analogs in other arts but remain distinctly “cinematic” (chiefly because of cinema’s ability to control duration). During the 1910s and 1920s, filmmakers refined pictorial narrative in ways that couldn’t have been foreseen earlier, and avant-garde movements showed that the new medium had remarkable abstract and non-narrative possibilities as well.

Because of all this, it seemed that sync sound came along just when the silent cinema had reached an expressive peak. By then, people knew the powers of the moving image, and so could integrate sound with it to create an audiovisual art form.

I think there’s a lot to be said for this viewpoint, though it was often used as a cudgel to beat early talkies as “uncinematic.” There’s no denying that many filmmakers who made outstanding silent films, from Hitchcock, Lang, and Ford to Lubitsch, Eisenstein, and Renoir, managed to retain pictorial richness while relying on the unique contributions sound could make. In a teaching exercise, Eisenstein asked students to plan the filming of the assassination of Julius Caesar as a silent film, and then go back and reconceive it as a sound film. That way, the new synthesis could exploit the strengths of both ingredients.

Julien Duvivier’s silent films are good examples of the push toward maximal expressivity by means of visuals. He accepted the coming of sound, even welcoming color and depth, but by then he had already accepted the 1920s urge toward an overwhelming pictorial experience. At one level, he saw the need for spectacle–either shooting on striking locations, employing masses of actors, or creating flamboyant studio sets. At another level, the visual storytelling could be more inward-turning. How could moving images illuminate the thoughts and feelings of characters, the access to minds given through language in prose fiction and on stage? We can see in Duvivier’s late silent work a pressure in both directions: a love of eye-smiting locations either found or fabricated, and an urge to plunge into characters’ minds at every moment.

Julien Duvivier’s silent films are good examples of the push toward maximal expressivity by means of visuals. He accepted the coming of sound, even welcoming color and depth, but by then he had already accepted the 1920s urge toward an overwhelming pictorial experience. At one level, he saw the need for spectacle–either shooting on striking locations, employing masses of actors, or creating flamboyant studio sets. At another level, the visual storytelling could be more inward-turning. How could moving images illuminate the thoughts and feelings of characters, the access to minds given through language in prose fiction and on stage? We can see in Duvivier’s late silent work a pressure in both directions: a love of eye-smiting locations either found or fabricated, and an urge to plunge into characters’ minds at every moment.

These revelations come courtesy of Flicker Alley’s massive collection of nine of his late 1920s features, all beautifully restored by the dedicated team at Lobster Films. Poil de Carotte (1926), the earliest item in the box, shows a filmmaker utterly in command of the resources of the “mature silent cinema.”

Most of the films between that and Au bonheur des dames (1930) have been largely unknown and forgotten, and their revelation here is unlikely to add another masterpiece to his career log. But they’re very impressive for revealing the diversity and ambitions of mainstream French cinema of the 1920s. Moreover, Duvivier was prepared to carry a commitment to pictorial storytelling to striking extremes.

Eye candy, natural and artificial

Duvivier’s first film, Halcedama (1919; not in this collection), a French “Western,” made extensive use of the rugged terrain of the Corrèze region, “the savage heart of France,” according to a title. Extreme long shots (akin to those in Feuillade’s Tih Minh) let mountains and valleys dwarf the characters. The 1920s films tend to be melodramas, but they too exploit locations with expansive production values.

Before moving to cosmopolitan scenes, Le Tourbillon de Paris (1928)’s opening scenes give off a palpable sense of cold in their bleak display of a man struggling through the snow in Tignes, in the French Alps. The same regional realism is present in La Divine Croisière (1929), shot on location in several coastal cities.

L’Agonie de Jérusalem: Revelation (1927) tells of an anarchist who rejects bourgeois comforts, including “paternal power,” and agitates for world revolution. When he’s blinded, he returns to the family home in Jerusalem. There he undergoes a conversion through identifying with Christ’s suffering and is miraculously cured. Duvivier took the production to Jerusalem, and the film features impressive scenes of the area, including the Wailing Wall and the Garden of Gethsemane.

For Maman Colibri (1930), Duvivier’s heroine, a woman who leaves her husband for a soldier young enough to be her son, follows him to his post in Algeria. The film exploits both desert landscapes and the sumptuous gardens of the Villa Arthur in Algiers. Closer to home, but still carrying the whiff of the picturesque, was Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans (1927), a comedy about rivalry between brewers. The film begins with a montage of Belgian cities and their landmarks, culminating in a documentary montage of Brussels. The film is bookended by a double wedding at the city’s splendid Grand Place.

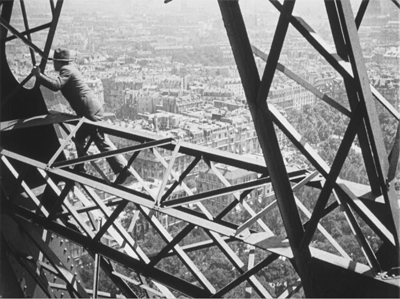

Probably the location shooting that will most attract a viewer today is the climactic sequence of Duvivier’s parody of Feuillade serials, Le Mystère de la Tour Eiffel (1927). It consists of a long chase up the girders of the tower, with actors scrambling after one another in vertigo-inducing shots.

As with Tih Minh, you have to marvel at the acrobatic skill and sheer guts of the performers.

Duvivier also took advantage of the resources of well-endowed French studios, which had yielded impressive set design in Gance’s Napoleon (1927), L’Herbier’s L’Argent (1928), and Dreyer’s Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928). Le Tourbillon de Paris, tracing the return of a stage diva to the city she loves, shows her reentry into the haute monde in a huge nightclub scene. This is later matched by her triumph in before a theatre audience.

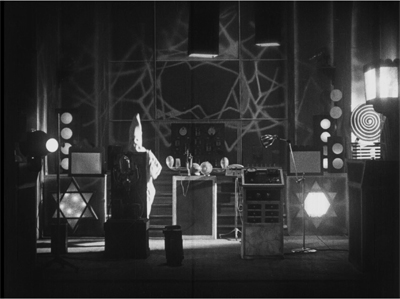

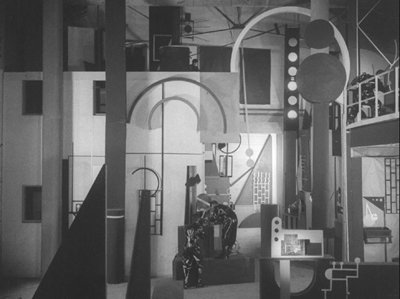

More stylized sets, in a comic vein, characterize the Antenna gang in Mystère de la Tour Eiffel. They use , the Tower to transmit coded messages to their agents. The gang headquarters may be a down-market parody of Léger’s modernist sets of L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine (1924).

Probably the most famous achievement of Duvivier’s set design is the staggering department-store set in Au Bonheur des Dames, Zola’s story of big business crushing local shops. Sweeping tracking and crane shots enhance the scale of Au Bonheur des Dames, modeled on the Galeries Lafayette (where a few shots were taken as well). The film contrasts the vista of the main shopping area with the cramped store of the fabric merchant Baudu.

The same difference emerges in the broad layout of the office of store’s boss Mouret and Baudu’s pinched apartment, built as a complete set of rooms.

Yet the sets can be less ostentatious and still powerfully functional. The simple, geometric grids and figure placements of the investiture scene in La Vie miraculeuse de Thérèse Martin (1929) gather force through their precise articulation of the stages of the heroine’s acceptance into the sisterhood.

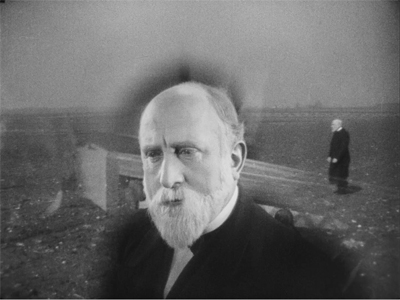

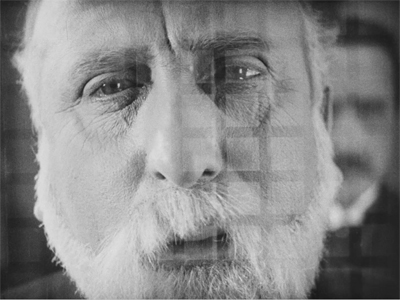

In this twenty-minute sequence, details of gesture and position exude respect for the rigors of ritual and the sincerity of the girl. Duvivier’s calm precision reminds me of scenes in Bresson’s Anges du péché. At the same time, the impersonality of the ceremony is heightened by cutaways to Thérèse’s father, at once pious and regretful; with her novitiate, he will die alone. For him, Duvivier adds Impressionist flourishes to emphasize that the grille shuts him off from her.

Such scenes create a sort of “intimate spectacle” that goes beyond sheer scale.

In a fine crowd scene in La Divine Croisière, Duvivier deploys expressive detail within a mass of people. The predatory capitalist Kerjean has ordered a defective ship to sail, and the townsfolk fear that it has been lost. Simone, a courageous young woman, calls a meeting in which she asks them to cease mourning and set out to look for the sailors. In a brief montage reminiscent of the cream-separator sequence in Eisenstein’s Old and New, close-ups show the villagers gathering hope under Simone’s visionary appeal.

With this sort of intimacy, however, we move close to the second pictorial strategy that characterizes Duvivier and many of his peers: picturing the workings of the mind.

Getting inside

Kristin has pointed out that the 1910s were an era when many filmmakers wanted to go beyond simply creating a coherent story by adding expressive dimensions to the action. Many American films of the period try to illustrate characters’ thoughts, chiefly through flashbacks. There were more elaborate experiments as well, with attempts to portray dreams, hallucinations, and even alternative courses of action. (Some examples here.) In The Gangsters and the Girl (1914), a young woman imagines two consequences of a robbery.

Halcedama had, like many other French films, incorporated simple subjective techniques like these. The looming figure of the protagonist’s dead father interrupts several scenes, and one scene multiplies the presence of the man the protagonist has come to kill.

The early 1920s saw French filmmakers eagerly exploring other resources. Duvivier’s films are much of their time in their inclusion of wide-angle shots with big foregrounds, a great range of camera angles, freely moving camerawork (including crane shots), heavy use of superimposition and dissolves, and a multiplication of cuts, often very fast-paced.

Abel Gance’s La Roue (1922) and Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidèle (1923) crystallized these possibilities, and other filmmakers felt free to flaunt pictorial display. Many of these devices were put in the service of enhanced subjectivity.

In scene after scene, Duvivier dwells on the moment by plunging into characters’ reactions to the scene, given not through dialogue but through imagery. One of his favorite devices is the superimposition–not as a single item, as in The Gangsters and the Girl, but as a flurry of images melting into one another, suggesting a stream of consciousness. In L’Agonie de Jérusalem, Alice recalls the childhood she shared with Jean, as images rolling along a road.

The heroine of Le Tourbillon de Paris is dazzled by the array of jewels and dresses her husband offers her, and the heroine of Maman Colibri is captivated by her dance partner.

Poil de Carotte is a virtual anthology of ways of conveying mental states. This tale of child abuse probes the fear and despair François feels by being trapped in a family full of hate. The opening uses superimpositions of family members to show how it’s painful for him to write an essay about them.

His cruel mother haunts his dreams, and her attacks on him are given in distorted imagery.

As he rigs up a noose with which to hang himself, we get a rapid montage, in superimposition, of memories of ill treatment.

Nearly every film is packed with these inserted passages, which seek to deepen the drama without use of intertitles. Today they look old-fashioned, even though our films continue to use them. Back then they may have become a bit tiresome. Serge Bromberg’s text for the Flicker Alley booklet quotes a 1930 review:

Why does Julien Duvivier sometimes insist on techniques that seem obsolete today? Overprints [superimpositions] and special lenses no longer surprise us.

When they work best, I think, it’s because they find fresh material that allows them to unexpectedly expand the moment of a scene. For example, François’s father is not so much cruel as indifferent to the boy. His gradual realization that the mother is working the boy like a dog is given two ways. First, a multiple-image shot shows several versions of his son busy in the garden.

Then a series of dissolves following the father’s advance to the camera shows the sheaves now sprung up in profusion–all as a result of the boy’s labor.

Still, Duvivier was able to probe minds without such devices. The village meeting in La Divine Croisière, mentioned above, is an example. So too is a little bit of byplay in Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans.

Albert, a Parisian, is working in a Brussels brewery and has fallen in love with the boss’s daughter Suzanne. He leaves a corsage on her desk while she’s out. Seraphin, her shady fiancé, has found it there and, when she returns, offers it to her as his own gift. When Albert returns and finds her wearing it, he assumes that he’s won her affection–until he realizes Seraphin’s ploy. Duvivier could have played this out in a series of superimpositions in which Albert imagines her finding it, thinking of him, and wearing it for his sake. Instead, it’s left to the actors in a simple two-shot.

Albert sees her caress the corsage and he’s pleased. But then she says Seraphin gave it to her. There’s no dialogue title. She turns her head to the left to indicate he’s outside.

Albert starts to claim credit, but thinks the better of it and turns away. She notices and asks if he gave it to her.

He doesn’t admit it, but she realizes the truth.

As she ponders Seraphin’s deceit, Albert understands. He approaches, but she wards him off, still believing she must marry her fiancé.

Admittedly, this little pas de deux takes place after a dialogue in which Albert imagines all the slights he’s suffered as an outsider to the company, and before a lyrical passage in which he conjures up finding a flower in a lake. Duvivier couldn’t resist expanding the situation through his usual means. But the understated playing of the pair, without any verbal explanation, shows that he didn’t always need flashy visualizations to evoke characters’ changing reactions to a situation.

Duvivier remained active until his death in 1967, racking up an astonishing seventy-one features. There are plenty I have yet to see, but I’ll just signal some landmarks. Although he has remained most famous for his two Poetic Realist achievements, La Belle équipe (1936) and Pépé le Moko (1937), his accomplishments were more wide-ranging. Allô Berlin? Ici Paris! (1932) is a charming early sound comedy, and Un Carnet de bal (1937) and La Fin du jour (1939) won acclaim around the world. In Reinventing Hollywood I called attention to his significant American work: Lydia (1941), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Flesh and Fantasy (1943). His powerful Simenon adaptation Panique (1946) is admirable, as are the lighter-hearted Sous le ciel de Paris (1951) and La Fête à Henriette (1952). Marie-Octobre (1959) is an interesting experiment in the three unities. And his later policiers have their supporters, especially Voici les temps des assassins (1956). Attacked by the Nouvelle Vague as a fossilized academic, he has reemerged as a robust example of the enduring force of French film tradition. The Lobster/Flicker Alley box confirms him as a sturdy storyteller and an ambitious pictorialist.

Halcedama is available on the Cinémathèque Française website, among many other discoveries. Gance’s broadside, “Le Temps de l’image est venu!” is in L’Art cinématographique II, ed. Léon Pierre-Quint, Abel Gance, Lionel Landry, and Germaine Dulac (Paris: Félix Alcan, 1927), 83-102. It is available in an Arno Press reprint (New York, 1970).

The best book on French silent film is Richard Abel’s magnificent, encyclopedic French Cinema: The First Wave, 1915-1929. A very complete account of Impressionist cinema is in Noureddine Ghali, L’Avant-garde Cinématographique en France dans les années vingt: Idées, conceptions, théories (Paris: Experimental, 1995). Kristin’s argument about the 1910s is set forth in “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Film and the First World War, ed. Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp (Amsterdam University Press, 1995), 65-85.

Kristin picked Au Bonheur des dames as one of the best films of 1930. I discuss Lydia in a Criterion Channel installment, teased here. French Impressionism has remained a powerful, if usually indirect, influence on modern directors–for example, Scorsese.

Le Mariage de Mlle Beulemans (1927).

Dietrich before von Sternberg and von Sternberg before Dietrich

Thunderbolt (1929)

Kristin here–

In my entry on the ten best films of 1929, I suggested that that particular year, hovering as it did between silents and talkies, was relatively poorly represented on home video. Now Kino Lorber has released two films from that year that both entertain us and contribute to our knowledge of the late 1920s cinema.

In that entry I lamented the fact that Josef von Sternberg’s marvelous early talkie Thunderbolt had not had a proper DVD or Blu-ray released. I expressed hope that one of the home-video companies specializing in historically important classics would finally make it available. The Kino Lorber release finally allows historians and cinephiles access to this little-known masterpiece.

If Thunderbolt was a legendary film that called out for such a release, the 2012 Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung restoration of Kurt Bernhardt’s The Woman One Longs for reveals this previously forgotten film to be, if not a masterpiece, a very good film. It’s also completely typical of a trend of the late 1920s that I have termed the International Style.

Coincidentally, von Sternberg and Dietrich, so closely connected in our minds, link the two releases. Thunderbolt was the director’s last film before beginning his series with Dietrich, and The Woman One Longs for was Dietrich’s last (and first) starring roll before she worked with von Sternberg for the first time.

I’ll deal with it first, since I don’t want it to be overshadowed by Thunderbolt.

The Woman One Longs for

The standard story has Marlene Dietrich claiming that The Blue Angel was her first film. Seemingly she wanted to suggest that von Sternberg’s use of her in a series of star vehicles created her career. The image above, of her staring through a frosty train window, might easily be mistaken for a von Sternberg shot. In fact it’s from her previous film, The Woman One Longs for (Die Frau, das der man sich sehnt, aka The Three Lovers), directed by Bernhardt.

The Jewish director barely made his escape from the Nazis, working during the 1930s in France and then shifting to Hollywood. There, under the name Curtis Bernhardt, he made many films up to the 1960s, perhaps most notably the Joan Crawford psychological drama Possessed (1947) and the Rita Hayworth vehicle Miss Sadie Thompson (1953). That was an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s “Miss Thompson” (previously filmed by Raoul Walsh as Sadie Thompson, starring Gloria Swanson, in 1927 and by Lewis Milestone as Rain [a new title that had replaced the original name of the short story], starring Joan Crawford).

The plot of The Woman One Longs for is straightforward melodrama. The protagonist, Leblanc, is expected to rescue his family’s factory, tottering on the brink of bankruptcy, by marrying a wealthy heiress who loves him but who leaves him cold. He marries her, but on their honeymoon trip aboard a train to the south of France, he suddenly becomes fascinated by a mysterious beauty, played by Dietrich. She seemed to be under the sadistic control of Dr. Karoff. The latter is played by the great actor of the Expressionist theater, Fritz Kortner, familiar to most modern spectators as Dr. Schön, who keeps Lulu as his mistress in Pandora’s Box (also 1929). Leblanc becomes obsessed with saving Dietrich from her captor.

The plot is entertaining enough, but the real interest in the film, at least for David and me, is Bernhardt’s direction. It’s quite skillful, even flashy. Moreover, Bernhardt had clearly been seeing many of the major films of the 1920s from Germany, the USSR, and France. Like many other directors of the late 1920s, he blends them seamlessly into what I have called the “International Style.” (See Chapter 8 of Film History: An Introduction.)

The film starts in a setting done in a style familiar from many German films of the era, with a camera following a character through an atmospheric, faintly Expressionist street clearly built in a studio (below left). Even after the Expressionist movement ended in early 1927 with Metropolis, German films continued to use settings influenced by the style to represent old buildings or poor neighborhoods. Compare the opening shot of The Blue Angel (below right), the only Expressionistic setting in the whole film.

But Bernhardt has seen Soviet films as well. The early montage establishing the Leblance family’s factory uses the quick cutting, dramatic angles, and dissolves that such scenes have in so many Soviet and European films of the era (below left). A fight scene between Leblanc and Karoff uses fast editing, canted compositions, and camera reframing (below right).

Bernhardt has almost certainly seen L’Herbier’s L’Argent of 1928, with its streamlined sets (left) and low-angle framings shot with wide-angle lenses (right). Compare the latter with the low-camera-height shot of the Paris Bourse at the top of the L’Argent section in the 1928 entry linked immediately above.)

Bernhardt had also clearly seen Underworld, for the New Year’s party that forms the climactic scene of his film imitates von Sternberg’s party scene fairly obviously. The action centers around the two main male characters’ struggle over the heroine, with two count-downs raising the suspense: the beauty contest in Underworld and the approaching midnight signalling the new year in The Woman One Longs for. The hanging streamers that increasingly dominate the setting are, however, the giveaway for von Sternberg’s influence on Bernhardt (see bottom).

Speaking of influence, there is a moment in the party scene when the drunken Kaross pops a startled child’s balloon with a cigarette. Maybe this is a common trope in films, but the only other example I can think of is Bruno’s similar gesture of casual cruelty in Strangers on a Train.

The Woman One Longs for also contains a reference that we might today call an “Easter egg.” At the end, Karoff is arrested in the luxury hotel where the three main characters have been staying and where the New Year’s party take place. The manager insists that in order to avoid a scandal, the police must escort him out of the building via the “Hintertreppe” (backstairs). One of Kortner’s major roles had been the devious, obsessed postman in Leopold Jessner’s Hintertreppe (1921), one of the few other classics by which Kortner is known today.

Thunderbolt

I have already sung the praises of von Sternberg’s pre-Dietrich films on this blog. I find his naturalistic first feature, The Salvation Hunters (1925) heavy-handed, but with Underworld (1927) he abruptly hit his stride. To me it and The Docks of New York (1928) are his masterworks–those and Shanghai Express (1932), arguably the best of his Hollywood Dietrich films. The Last Command (1928) is excellent but not up to that level. I discussed these three when The Criterion Collection released them as a set in 2010. That set went out of print but is fortunately now available in Blu-ray. I put Underworld in my ten-best list for 1927 and The Docks of New York in the 1928 list. As I mentioned at the outset, Thunderbolt made the 1929 list.

There I briefly discussed the remarkable compositions and use of offscreen sound in the lengthy prison scenes of the title character on Death Row. Watching the new Blu-ray in preparing this entry, I was struck even more by the early scene in the Black Cat, a Black-run nightclub where we are introduced to Thunderbolt and his relationship to Ritzie, the heroine. As in the silents, von Sternberg’s habit of staging compositions with obstructing objects in the foreground is apparent. Note the entrance of Thunderbolt and Ritzie with a set element both framing and obstructing them (see top). Later a scene as two patrons of the club gossip about Thunderbolt partially blocks the faces, particularly of the one on the left.

The whole scene is marvelously enhanced, as I said in my 1929 entry, by the inclusion of Theresa Harris’ complete rendition of “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” It’s hard to think of another mainstream Hollywood film in which a Black cultural situation is used so naturally and with so much respect.

The Black Cat sequence ends with a police raid on the club. The cinematography at this point is pure film noir. (See image at the top of this section.)

As I said in the earlier entry, the one flaw in the film is the tepid central couple played by Richard Arlen and Fay Wray. Given the excellence of the Black Cat sequence and the lengthy prison scenes, that flaw is minor indeed.

The Woman One Longs for (1929)