Archive for the 'Directors: Ruiz' Category

Got those death-of-film/movies/cinema blues?

Night Across the Street (2011).

DB here:

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

These squibs seemed especially damp this time around because while these guys were knocking Hollywood and/or art movies I was enjoying the Vancouver International Film Festival. If you’re willing to watch mainstream entertainments from outside Hollywood, or films that aren’t the bland arthouse fare full of stately homes and British accents, or even films that don’t chop every scene to splintery images, Dr. Bordwell has a cure in mind for you.

Had you been looking for breezy or outlandish entertainment, for example, the Dragons and Tigers wing didn’t disappoint. Helpless, from South Korea, is a thriller built around identity theft. I thought it was clumsily plotted, but it sustains curiousity through the apparently bottomless series of discoveries a man makes about his missing fiancée. Jeff Lau’s East Meets West is a Hong Kong farrago of rapid-fire gags, weird haircuts, references to old Cantopop, and nonchalantly wacko storytelling. Granted, the central idea of making the Eight Immortals of legend into modern superheroes (and one supervillain) is smothered by Scott Pilgrim-style SPFX. Still, I will watch Karen Mok Man-wai and Kenny Bee in anything, albeit for different reasons. Closer to mainstream Hollywood tastes was Nameless Gangster, in which a restless flashback structure traces the rise of a flabby brute from customs agent to top drug smuggler. Yoon Jongbin’s slickly-made film ends with an abruptness that recalls the conclusion of The Sopranos.

Of all the pop-entertainment movies I saw at VIFF, the audience favorite was doubtless Key of Life, a nifty Japanese crime comedy. An amnesiac hitman and a shambolic slacker swap identities in a cunning series of coincidences that brings on some satisfyingly menacing underworld types. Intersecting the men’s misadventures is a hyperorganized OL, or office lady, who determines to find herself a husband within a month. Everything sorts itself out, of course, with one nice wrapup saved for the middle of the closing credits. This is the kind of Japanese diversion I’ve recorded a liking for earlier (Uchoten Hotel and Happy Flight). Hampered by a wretched title, Key of Life probably won’t get US theatrical distribution, although it may make some headway on VOD. Aussie movie maven Geoff Gardner and I agreed that if we had the money, we’d buy the remake rights.

Everything new is old (again)

Tabu (2012).

Form is the new content, they say. (Too simple, but some do say it.) No surprise, then, that part of what appeals in contemporary cinema is its overt reworking of previous styles. Neo-noir is perhaps the most common current example, but ingratiating retro-stylings were on display in more rarefied forms at VIFF.

Part of the appeal is the rediscovery of the glory of the 4:3 aspect ratio. Kristin has already talked about how Pablo Larrain’s No appropriates a seedy U-matic look to tell its tale of 1970s Chilean politics. A similar pastiche effect emerged from Mine Goichi’s All Day, a short that used even grubbier video to parody Japanese family dramas. May we expect to see more VHS-looking movies? I wouldn’t mind.

Silent cinema pastiches are usually lame, as witness The Artist, which scrambles history and treats old films as oddly soft-minded. (No Hollywood drama of the late 1920s would have been built around a protagonist so feeble he tries to commit suicide twice.) Jean Dujardin, and contemporary audiences that adore his film, should catch up with Hayashi Kaizo’s To Sleep As If to Dream (1986), in which the contemporary story is played as a silent film and the rediscovered (fake) old film is accompanied by benshi commentary and music. The “forged” footage in Forgotten Silver also shows how good filmmakers can create convincing, pleasantly anachronistic imagery.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

More celebrated since its Berlin triumph (two awards) is another 4:3 exercise, Miguel Gomes’ Tabu. A vaguely 1920s prologue shows a brooding tropical explorer who has seen his ex-wife as a ghost. Then Part 1 (“Lost Paradise”) takes us to stately black and white imagery of contemporary Lisbon. It’s late in December, and Pilar is concerned about her elderly neighbor Aurora. The old woman is taken to a hospital and asks Pilar to find Aurora’s old lover, Ventura. By the time Pilar discovers him, it’s too late. After Aurora’s funeral, Ventura starts to explain how they met in Africa. Here starts Part II (“Paradise”).

Now the film becomes hypnotic. In Africa, Aurora is married to a sturdy, good-natured colonist, and she can hunt and shoot with the best of them. Ventura and his friend Mario, who’s becoming a pop crooner, are taken into the household. He and Aurora begin a torrid affair. Part II is rendered without onscreen dialogue, but not in exact mimicry of silent cinema. There is piano music, it’s true, and much of the action is carried by letters, as in a lot of silent movies. But there are no intertitles; instead, all the action is played out with the support of Ventura’s voice-over, occasionally supplemented by the young Aurora reciting letters she wrote. Moreover, Mario’s band and his singing are rendered in full lip-synch. More eerily, as Ventura explains the rise and collapse of the love affair, we get highly selective bits of noise—not everything audible in a scene, but perhaps the tinkle of glasses or a faint wind. These become the aural equivalent of glimpses.

“Paradise” gives us silent cinema not replicated, but refracted through memory and romantic longing. In a film paying homage to Murnau (a forbidden romance as in Tabu, the name Aurora recalling Sunrise), Gomes has apparently also sought to give us something like the “part-talkies” of 1928-1929. Those films had full-blown dialogue scenes (as in Part I) and other scenes containing only music and effects (Part II), relieved by synchronized musical numbers (a sequence showing Mario’s band performing by the pool). Tabu recovers something of the strangeness of those transitional films, notably Sunrise itself, while remaining highly contemporary. It knows that we can turn to tradition when we want to rekindle a romanticism that would look high-flown today.

Long live the long take

Beyond the Hills (2012).

At about 16 seconds per shot, Tabu has the same cutting rhythm as some early talkies, like The Black Watch and Hearts in Dixie. Today, as we’ve seen, the long take is increasingly the province of movies that play chiefly at festivals. All other things being equal, a movie with around 1200 shots, like the very popular Danish import The Hunt, will be an easier sell on the arthouse circuit than, say, Beyond the Hills, with only about 110 shots in 148 minutes. It’s a pity. Although The Hunt is a solidly crafted drama in the Nordic enemy-of-the-people tradition, it moves rather predictably across the combustible subject of false accusations of child molestation. Beyond the Hills, by Cristian Mungiu, director of Four Months, Three Weeks, and Two Days, is more enigmatic and demanding.

Voichita is a nun in a rural Orthodox enclave in Romania. She’s visited by her friend Alina. The two grew up as best friends in an orphanage, but Alina went to Germany to work, and now she insists that they must run off together. Voichita resists. Alina claims that Voichita once agreed to this plan. Has the young nun changed her mind and committed to the church? Or is Alina’s plan an idée fixe that Voichita has simply humored, without ever intending to join her? Were they perhaps lovers? Alina’s endless staring at Voichita and her lunges at suicide suggest deep passions at stake.

The refusal to supply full exposition makes characterization enticingly uncertain. Voichita’s wide-eyed sympathy for her friend can be seen as both pliable and stubborn, while Alina’s nearly wordless reprimands imply that Voichita has betrayed her. But perhaps Alina is just asking too much, or Voichita is being too unbending. The couple’s drama is played out against the stringent background of a female community ruled by a priest. Alina is incorrigible, not responding to the gestures of salvation extended to her, and agreeing, stone-faced, that she has committed every sin on a list of over 400. Eventually the pious souls decide that Alina is possessed, and her demons must be exorcised. In a simple gesture of solidarity, Voichita declares something like love for Alina, but too late.

Alternating discreet handheld takes with fixed shots staged in depth, making no concessions to impatience or easy responses, Beyond the Hills recalls the sobriety of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Bresson’s Les anges du péché. It plays out in a rougher-textured, muddier world, but it’s no less concerned with the dynamics of compassion and cruelty, dogmatism and eroticism. In each, a woman is ready to sacrifice herself for love. As Romania’s Oscar submission, Mungiu’s film deserves to find an audience in the US.

Long takes were also a specialty of the late Raúl Ruiz, whose penultimate film, Mysteries of Lisbon, won him probably the widest audience of his career. That film displayed his fascination with proliferating stories, but its adherence to a single plane of reality was exceptional in the career of a fabulist who enjoyed confounding all types of realism. In that regard, Night across the Street, his last fully completed work, is more characteristic.

An old office worker is about to retire and is convinced that someone is coming to kill him. While Don Celso awaits his assassin, he fraternizes with his co-workers, with schoolteacher and author Jean Giono, and with others in the hotel where he resides. He also recalls his childhood, when he talked to Long John Silver and went to movies with Beethoven. Eventually the plot shifts levels of reality even more radically, as one séance blends into another, characters shot down in a massacre return to life, and eventually Celso takes credit for inventing the people around him.

Mungiu’s handheld shots have no place here. As in Mysteries of Lisbon and his Proust film, Time Regained, the camera glides through this world with velvety assurance. Sometimes the characters do too, as they seem to ride the dolly or saunter in front of a blatantly unreal backdrop. Ruiz subverts academic cinema by using its well-upholstered technique, but he also mines film history. He revisits tableau staging in the shrewdly split set of Don Celso’s office, and he continues to exploit his more-Wellesian-than-Welles big-foreground technique.

Above all, the boy’s trip to the movies, in an awkwardly tilted image in which the usher usually blocks the screen, pays typically skewed homage to the medium’s enchantment. The mock film of Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream has given way to The Foxes of Harrow, the Hollywood cinema of Ruiz’s childhood.

Land, sea, and sky

small roads (2012).

When one thinks of the long take, James Benning comes quickly to mind, and small roads is true to form—in more ways than one. Forty-seven fixed shots in 102 minutes take us from the Far West to the South and to the Midwest before shifting westward again. The roads are indeed small, far from superhighways and traffic circles. As usual, landscape is the protagonist and slight shifts in image or sound arrest our attention. There are plenty of perceptual teasers. When a distant truck descends the distant sloping road above, it vanishes. Will it re-emerge in the nearer road? At another point, we wonder when, or if a car we hear will appear in the frame.

Hogarth spoke of art that leads the eye “on a wanton kind of chase,” and Benning’s roads—almost never seen from dead center, so we’re not given central perspective—carve oblique or sinuous paths into fields, plains, deserts, and forests. Road signs reenact the curve of the roadway, with carets and squiggles providing spare geometric “readings” of the piled-up surfaces of color and mass. There’s also some synesthesia. In one shot, I thought I heard mist rolling in. The topographies are real but through Benning’s strict scrutiny they become as fantastical as Ruiz’s dreamscapes.

That’s why I suspect that roads aren’t the real subject of the film. They serve as a pretext for Benning’s recurring interests in how wind curls clouds and makes branches tremble, how light outlines trees, how shapes like squat black oil derricks and the textures of fat snowflakes and soggy leaves can command the frame. Now that Benning has moved to digital filming, he has discreetly inserted some CGI. I couldn’t spot any, though one partial moon in daylight looks suspicious to me. No matter. Painterly beauty, along with a certain placid mystery, is enough for any movie nowadays.

At the other extreme lies the bustle of Leviathan, a poetic, quasi-abstract documentary by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. The filmmakers capture a New Bedford fishing trip through GoPro digital mini-cameras worn by fishermen, tossed into a netful of fish, or dragged through the water. Long takes abound here too, but it’s hard to say how many. As in The Man with a Movie Camera, the very boundary between one shot and another is put into question. So is the boundary between us and the space onscreen, as we’re weirdly wrapped in the extreme wide-angle yielded by this lens.

This is what you get when no human eye is looking through the camera. Often, in fact, nobody could look through the lens. No head, let alone human body, could occupy the space of some of these shots. Chains roll out past us from churning greenish darkness, while fish drift and slither on all sides. We’re right next to a gull trying to use its beak to lift itself to another area of the hold. Here the fish-eye lens lives up to its name. The camera bobs in a tank as fish are tossed in and spin aimlessly past. Coasting along the edge of the craft, we dip abruptly in and out of the heaving water, our plunge accentuated by brutal sound cuts. We chase starfish and ride waves, spinning up to watch gulls blotting out the sky. Accelerations of speed (again, Man with a Movie Camera comes to mind) render the action hallucinatory, especially since the shutter can capture foam with strobe-like precision.

One result is a disembodied, dehumanized vision of sea and sky: The camera as flotsam. But we also get bumpy, skittish visions of human labor definitely tied to bodies that harvest the ocean. Work activities are filmed from cameras lashed to the fishermen’s heads or lying on the deck among scallops to be shucked. Most documentary close-ups of artisans’ tasks are taken from far back and with long lenses; here the very wide-angle GoPro lenses not only show tasks from the inside, but their distortions exaggerate each gesture, sometimes heroically, sometimes grotesquely. Either way, human activity has been defamiliarized no less than undersea life.

We start the movie immersed in a welter of details and stay enmeshed for nearly an hour. Only then do we get an “establishing shot” showing the boat deck and mapping the overall process of filling and emptying the nets. And fairly soon after that, as if to parody the usual documentary about fisher folk, we get a four-minute shot of the captain dozing off while watching a TV show (apparently The Deadliest Catch). Leviathan ends with a sequence that brackets the chiaroscuro of the opening, but we no longer see a clam’s-eye-view of being snagged. Instead, we get barely illuminated darkness with whiffs of crimson teasingly darting to the edge of the frame, as if to signal the end, before swerving back to the center, then heading offscreen. Again, Ruiz has the line: Special shadows that give off light.

Ready to declare cinema dead? There is a cure for your malaise. We call it a film festival.

More of my thoughts on Ruiz can be found here and here. His widow Valeria Sarmiento completed his very last project, The Lines of Wellington.

On small roads and digital manipulation, see Michal Oleszczyk’s discussion at Slant and Robert Koehler’s informative review in Variety. In correspondence Benning confirms:

Yes, lots of compositing, but no speed changing, although the border cops are going around 100 mph. . . . Shot 26 has a sky that was filmed the next day about 100 miles away. And yes the moon was out, but that shot is pointing north so I filmed the moon in the southern sky during the day, and put it into the northern sky. All the compositing was done with shots I made; always somewhere nearby. (100 miles is nearby when you circle 2/3 of the US.)

You can learn more about Leviathan from Dennis Lim’s article on the filmmakers in the New York Times. The New York Film Festival provides a lengthy Q & A on its website. See also Phil Coldiron’s “Blood and Thunder: Enter the Leviathan“ in the latest Cinema Scope, with some superb frame enlargements. Above all, don’t miss the extract on vimeo, which gives you a good sample of the splendor of this film.

Leviathan (2012).

Ruiz in memoriam: Rules and ruses

Of Great Events and Ordinary People.

DB here:

Last week, Raúl Ruiz died. His death is an enormous loss to world film culture, not least because his penultimate work, Mysteries of Lisbon, brought him a prominence he had been denied throughout his forty-year career. More important, we lost a modest, kindly, and zestful man.

From the mid-1960s through 1975, it seems to me, there emerged an interesting in-between group of filmmakers. By then film festivals had canonized an official art cinema typified by Fellini, Bergman, Wajda, and the New Wave. Now there appeared a more capricious clutch of directors, of varying ages, who pushed in a more avant-garde direction. Many made outstanding short films, like Wenders’ Same Player Shoots Again, or the Straub/ Huillet Not Reconciled, or Akerman’s Hotel Monterey, or the peculiar early efforts of Peter Greenaway.

When they turned to features, this group of directors produced films like October à Madrid (Marcel Hanoun), The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (Straub/ Huillet), Fata Morgana (Herzog), Katzelmacher (Fassbinder), and Jeanne Dielmann (Chantal Akerman)—more rigorous and forbidding than anything attempted by the older generation. In later years some of these talents moved comfortably into the festival niches vacated by senior directors, but for many years most were little known outside a small circle.

If they were marginal to most moviegoers, Ruiz was marginal to them. Exiled from Chile, where he made his first features in his twenties, he moved to France in 1973. There he proceeded to direct over a hundred films, often financed by television, while staging plays and running the Maison de la Culture in Le Havre.

His films’ repute was in inverse proportion to their availability. He was celebrated by critics in France (Cahiers du cinéma took up his cause) and England (particularly by London’s Afterimage group). Ruiz had his fans in North America too, notably Jim Hoberman and David Ehrenstein. But the films were chiefly seen at festivals, and none of his productions of this period, so far as I can tell, found stable distribution, theatrical or nontheatrical, in the United States. In 1989-1990, while Ruiz was teaching at Harvard, a batch of his films was circulated here by the quixotic International Film Circuit.

What set him apart from the other marginals was a devotion to esoterica (philosophical, literary, ecclesiastical), pursued with a sly humor. He remarked that during one screening, he was the only person laughing at his movie. Although like most of his contemporaries his sympathies lay on the left, he didn’t seem to take himself seriously, and this put him at a disadvantage in 1970s-1980s world film culture. True, Herzog had a comic side, and in The Falls Greenaway offered whimsy, though of a relentless, almost oppressive variety. Most other directors, though, were somber as well as severe. But Ruiz enjoyed intellectual lampoon, pastiche, clever cross-references, and straight-faced absurdity; the Chris Marker of Letter from Siberia (1957) is perhaps a predecessor, though Marker himself didn’t escape Ruizian parody.

Ruses

Of Great Events and Ordinary People.

Having seen about ten percent of the Ruiz oeuvre, and a lot of it quite long ago, I can’t offer a comprehensive appraisal. (Visit the bottom of the page for some more assured threads through the maze.) For reasons that will be understandable to regular readers of this page, however, I feel obliged to write something in his memory. I merely offer some observations on aspects of his work.

Ruiz often based a film on a striking formal premise, what Henry James might call a donnée. Socialist Realism (Considered as One of the Fine Arts) (1973) began, Ruiz tells us, from the idea of

having two stories that would never meet (like in Faulkner’s Wild Palms), separated by a poem. The link would be made through this lyrical element placed at the centre – the element I eventually decided to throw out. These two stories would touch each other for a single moment, accidentally, and this moment would be secondary in relation to the totality of the film.

Imagine another sort of intersection: two films in one, not a film-within-a-film but two distinct movies, one incomplete, the other filling the gaps but revising and correcting the first (The Suspended Vocation, 1977). Or imagine making an art-history documentary that speculates on the possibility of a missing link in the output of an imaginary, mediocre artist (The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting, 1979). How about dismantling the conventions of TV election coverage, to the point where one can no longer discern what candidate won (Of Great Events and Ordinary People, 1979)? Or what if a man assigned to memorize the names of 15,000 political resisters becomes absorbed in recalling visiting a movie house as a child (Life Is a Dream, 1986)? Or perhaps a single actor could play different characters (Three Lives and Only One Death, 1996)?

In their working out, however, these givens often fret and fall away. They are overtaken, or nowadays we might say overwritten, by digressions, anecdotes, accidents, interruptions, abstruse commentary, coincidences, free associations, labyrinthine plot twists (often driven by conspiracies and secret pacts), and Surrealist juxtapositions. The movie house of Life Is a Dream has a toy train running through it. Ruiz’s affinities with Borges and Góngora and Chesterton point to an almost academic fascination with schematic systems, as well as the desire to push them toward absurdity. It’s telling that the poem that was to knot the two strands of Socialist Realism was clipped from the movie.

Narrative binds, but narrative also loosens. It can be a robust oak, but it can also be kudzu. Ruiz understood that what keeps us listening, reading, watching is the promise of a surprise that in retrospect will seem inevitable. The best tragic plot, Aristotle says, is one that makes unexpected things happen within a cogent chain of causality. Ruiz knew our inclinations, but what he gave us were plots of the sort that Aristotle calls episodic–perhaps we should say fragmentary. His plots exfoliate, in both senses of the word: they spread out from a kernel, and they peel off in flakes.

In this respect he turns out to be the realist, and Aristotle the fabulist. Ruiz understood that real-world stories breed like rabbits. Listen to yourself and a friend in conversation, and you’ll find one story calling up another, with yet a third crowding from at a tangent before the first one is finished. In plotting our fictions, we can multiply tales neatly, staking them out in parallel lines or coiling them inside Chinese boxes. But if we take the pressure off, the stories can burst out of control, intertwining or doubling back or sprawling out or just dying off. Feuillade and his contemporaries understood this: A serial could go on forever, because we could plop in a fresh character and create a further adventure. The same thing happens with news on the Internet, spreading and splintering, each version of a story torn apart but also expanded by rehash and critique.

Perhaps we can take some of Ruiz’s abrupt deep-focus shots, blowing up an action or a bit of the set that would otherwise be minor background detail, as a pictorial reminder of the centrifugal impulse of narrative. Anything looming in the foreground hints at the possibility of a new character with a new story. In Three Crowns of the Sailor, while the sailor listens to a tale told by the Blind Man, we are distracted by grotesque glimpses of what unseen others are up to in the bar.

Stories have to end, but nothing at the end can match the arousal of a beginning. Endings usually disappoint. The explanation of an puzzling situation–say, footprints on the ceiling–will inevitably be more prosaic than the premise that sets our imaginations on a wanton chase. (Hence the perfunctory, even arbitrary, resolutions of detective stories.) By contrast, openings refresh us and, as the name implies, “open” things up to crazy possibilities. So why not use the prospect of endless beginnings, perpetual change of situation, to sustain the magic?

What becomes inevitable isn’t a logical resolution, which has to be more or less imposed by tradition. What’s inevitable is a perpetual spawning of characters, plots, and situations. So an apparently stable, albeit fantastic, narrative situation posited at the start may be undermined. Again and again the film seems to start over; the rules keep changing. Ruiz made shaggy-dog stories for cinephiles. He was a formalist who liked unraveling forms.

On the whole I was more an admirer than an enthusiast. I thought Ruiz’s films were imaginative and risky in ways that opened up new horizons. I tried to do justice to his importance in the survey of film history that Kristin and I composed.

Yet here we confront the difference between critical judgment and personal taste. I tended to find each Ruiz film intriguing on an intellectual level, but dry and scattershot as well. For all the prodigious invention, and given his bias toward free-range story breeding, I sometimes thought that the données were underdeveloped. He had wondrous ideas, but I wasn’t sure that he did enough with them. And of course some stretches of his yarns were downright opaque to me.

Still, artists have a way of teaching us how to watch, and rewatch, their work. Maybe now, after having been absorbed by Mysteries of Lisbon for reasons sketched here, I’m better prepared to appreciate the legacy of a unique sensibility–one that has already given us the adjective Ruizian. It is a term of praise.

No filmmaker had more zealous proselytizers. His admirers have shown how to blend analytical precision with brio. They make you want to see the films pronto. The Ruiz initiate can start with Adrian Martin’s homage at girish’s site. You won’t read a more sensitive piece of film criticism this year. Next savor James Schamus’ memoir at Filmmaker, where he recalls working with Ruiz on his first US film. Proceed to Jonathan Rosenbaum’s posting of one of his classic studies of Ruiz, which includes links to other essays.

Now you’re ready for the heady experience of the annotated filmography (complete up to 2004) in the journal Rouge. Both Adrian and Jonathan participated. My quotation about Socialist Realism comes from there. By now you should be on to the films, and perhaps the writings collected in volumes one and two of Ruiz’s Poetics of Cinema.

By chance I commented on Ruiz just a little while ago. And thanks to B. Kite for the note about Ruiz and Harry Stephen Keeler, obviously kindred spirits. Mr. Kite sent Ruiz some Keeleriana, which may have influenced what Ruiz says here.

Apologies for my tongue-twisting title, which is offered in the spirit of Tres Tristes Tigres.

Mysteries of Lisbon.

Ruiz, realism, and…me?

Mysteries of Lisbon (2010).

DB here:

Once Fassbinder said something to this effect: “One is always misunderstood. If you spend time clearing up misunderstandings, you’re dead.” Usually I think this is good advice. Now, though, a filmmaker whom I admire has, in publicity for a film that I admire, misunderstood me. So I’m squawking, mildly.

I met Raúl Ruiz only once, many years ago during his visit to our university here in Madison. We’d programmed At the Top of the Whale and Life Is a Dream. One afternoon we were sitting in the Student Union looking out over majestic Lake Mendota, and he started to muse. “I see a boat on the lake. Three men are in the boat. One is planning to kill the other two, but we don’t know which one it is.”

This was only one of many forking paths our conversation took. Over dinner that night Ruiz was at pains to explain that there was nothing new in Postmodernism that we couldn’t already find in the Spanish Baroque. That was pretty persuasive. He talked as well about his two production courses at Harvard. “In one, we shoot a drama as if it were a TV quiz show. In the other, we shoot a quiz show as if it were a drama.” In sum, typical Ruiz ebullience and passion for rethinking forms.

Earlier this year my name got linked to his in an unexpected way. In an interview, Ruiz mentioned that a Swiss magazine had claimed that Mysteries of Lisbon didn’t conform to “Bordwell’s Paradigm,” and he agreed. Alerted to this interview by Adrian Martin, I shook my head and thought, I don’t know what Bordwell’s Paradigm is, so how can anybody else? I suspect the label has to do with my characterization of classical Hollywood cinema, but who knows?

Since then Ruiz has signed a discussion of Mysteries of Lisbon that expands on the same theme. You can read it here. It starts off with a bang:

The American professor David Bordwell considered that all narrative strategies that can be applied to modern films are based on a certain notion of verisimilitude (or narrative evidence).

Thanks to them, the most unbridled fictions are acceptable and accepted. And this very verisimilitude, it is said, is averse to any straying from a guiding line (what is commonly called the action’s guiding arrow), with its variations in intensity and its turbulent twists and turns.

This theory, which depends on a certain number of rules often abusively attributed to Aristotle, finally became what purists hastened to naively call “Bordwell’s paradigm”–the whole of narrative strategies that stem from impulse, from the presumption of verisimilitude.

What is called “modern drama” or “bourgeois drama,” or even “the Ibsen Shaw postulate” has given rise to this superstition. In modern drama, structure and construction dominate, even beyond the poetic incoherence or the irrelevant facts it supposes. The author is an architect who builds shelters for fictions, various events which, and only because they are protected from the rain of the improbable, become credible and relevant.

Each of these fictions, of these mobile structures, is guided by a narrative arrow. But beware, only one per fiction: William Tell is a well-told story because only one arrow cuts in two only one apple, but the battle of Azincourt is not because Robin Hood and his people’s swarm of arrows does not enable one to read the time on the narrative clock, veiled as it is by clouds of arrows, each guided by its independent little intrigue. “Clouds and not clocks” would say Karl Popper.

In modern drama, the proliferation of truncated facts is not acceptable because it makes us stray from the notion of causality which is inherent to that of verisimilitude, and without which there would be no story.

Promoting a film by citing an American professor may not be the height of shrewd marketing, but put that aside. Peering through the haze of this rather awkward translation, I’m inclined to say that Ruiz mistakes my claims. I’ve said in several places that narrative, prototypically, requires causality. But that isn’t the same thing as claiming that such causality is realistic in nature, or that causality is the main attraction of narrative. Mainstream cinema, including Hollywood, often uses certain kinds of verisimilitude as an alibi for formal experimentation. And I’ve celebrated filmmakers like Eisenstein and Ozu who break away from narrative causality.

It’s ironic that on the same day I post a blog entry arguing that realism gets short shrift in studio cinema of the 1940s, I find Ruiz claiming that realism is my guiding light. If I disapproved of the “disparate, truncated, labyrinthine and baroque” aspects of narrative, I wouldn’t have said this about Mysteries of Lisbon:

This being a Ruiz film, there is as well a tangible pleasure in the artifice of storytelling. The film acknowledges that all the handy coincidences, buried pasts, multiple identities, and revelations of kinship are there for our delectation. . . .

This recounted history is only the first of a cascade of flashbacks, issuing from several characters, and these gradually show deep connections among persons tied to Pedro’s past. Secondary characters in one story become protagonists of another. The young hero is gradually displaced as the center of the action by war, secret romances, rivalries, duels, and infidelities. Like Pasolini in his Trilogy of Life, Ruiz is happiest when opening up a plot detour that will eventually become a new main road.

You can read my whole account, from last year’s Vancouver International Film Festival, here.

I think that Ruiz and I might disagree about how much Mysteries owes to psychological causation, and about whether labyrinthine trails can converge, let alone become highways. Both of us use metaphors of linearity, so maybe our disagreements are basically about whether the detours and paths are truly dead ends. Maybe I think his plotting is tighter than he does. Still, I expect that we’d agree that much of the pleasure of the film is its delight in apparently capricious digression.

Anyhow, my squawk is mild because it’s a pleasure to be misunderstood by a grand filmmaker. What Fassbinder didn’t say was that artists’ misunderstandings can be productive, leading to the creation of new artworks, and perhaps ideas about them.

If my remarks on Mysteries of Lisbon don’t make you thirst to see it, Manohla Dargis’ review surely will.

Seduced by structure

Mysteries of Lisbon.

DB here:

If you’re hungry to learn about the ways films can tell stories, a festival provides a feast. A huge array of narrative strategies is spread out for your delectation. You won’t like every movie you see, but thinking about the mechanics of each one can deepen your experience of it, as well as your appreciation for just how wide cinema’s resources can be. You also get to see how more unusual approaches to storytelling are often imaginative revisions of more traditional strategies.

We can usefully think about narrative from three angles. We can study the story world that a film conjures up: the characters, places, and actions we encounter. We can analyze plot structure, the distinct parts that are put together sequentially. They might be scenes or sequences or larger-scale parts, like the Hollywood screenwriters’ “acts.” We can also analyze narration, the patterned, moment-by-moment process of presenting the story world and the plot structure. Think of a narrative as like a building. The building’s furnishings correspond to the story world, and the architectural design of the building, plan and elevation, is like plot structure. Our real-time pathway through the building, from the front doorway into its depths, corresponds to narration.

The Vancouver International Film Festival that Kristin and I have been visiting offers a banquet of storytelling devices—some quite traditional, some fairly fresh. I’ll just survey some aspects of structure that I found intriguing.

The longest distance between points

The Chinese blockbuster Aftershock, centering on the 1976 earthquake that struck Tangshan, has earned some complaints about weepiness and jokes about “Afterschlock.” Perhaps melodrama makes many critics uncomfortable. They seem more at home with comedy and noirish crime stories, perhaps because the emotions stirred by these are bracketed by a degree of intellectual distance. But tell a story about a happy family split apart by a catastrophe; show a mother forced to choose between saving her son and saving her daughter; show that the girl miraculously escapes death; present her raised by a pair of new parents; and dwell on the fact that her mother, living elsewhere, expects never to see her again—do all this, and you court mockery.

Well, mockery from everybody except the hundreds of thousands of people who have always enjoyed these situations. Aftershock is now the biggest box-office success in Chinese film history (presumably using today’s currency standards). Whatever the film owes to Chinese traditions, it is easily understandable in a Western context. Stories based on pseudo-orphans, separated siblings, and parents forced to give up children have long been sure-fire. Les Deux orphelines, an 1874 play, is one strong prototype. This pathetic tale of two sisters torn apart in post-revolutionary Paris was adapted by many directors, including Griffith (Orphans of the Storm, 1921). Feuillade developed similar motifs in Les Deux gamines (1921), L’Orpheline (1921), and Parisette (1922). A mother’s loss of her children through accident or social oppression is another stock situation, seen in sublime form in Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. The obligation to pick a child to save is at the core of Sophie’s Choice, a more highbrow melodrama. Likewise, the discovery of unexpected kinship forms the climax of many stories, from Oedipus Rex to Twelfth Night and beyond.

You may call these conventions hackneyed, but it would be better to call them tried and true—proven effective by centuries of deployment, counting on emotions aroused by ties of love and blood. Such situations would be good candidates for narrative universals, which can be reshaped by local cultural pressures.

The premise of a fragmented family bears chiefly on the story world. The filmmaker still must choose how to structure the plot. For Aftershock, director Feng Xiaogang and his collaborators settled on the time-honored route: parallel stories across the years, shown by means of crosscutting. After the quake, scenes of the mother and son alternate with scenes showing the girl’s rescue and her life with her adopted parents, both soldiers in the People’s Liberation Army. For about the first sixty minutes, the segments are rather long, but after that shorter scenes from each plot line are intercut. The son moves off to a separate life, but his success as an entrepreneur is given short shrift. The plot concentrates on the daughter’s college career, her sometimes stormy relation with her foster parents, and her unexpected pregnancy. In the meantime, the mother survives, turning aside a kindly suitor in order to preserve her faithfulness to the husband who saved her life.

Narrationally, the alternation between the separated characters gives us superior knowledge. We know, as the mother and brother do not, that the daughter survives; we also know that she nurses a bitter memory of hearing her mother choose the rescue of her brother. Likewise, we know that the mother has tormented herself for decades over her forced choice. Thus the recriminations that will burst out after they rediscover one another will require some healing, which is provided in the plot’s last phase. Melodrama depends on mistakes, and they must be corrected. In a telling image of two sets of schoolbooks (not previously shown to us), we and the daughter realize that over the years the mother has been thinking of her as if she were still alive.

The dual structure can also tease us with suspense. At the hour mark, we learn that both the brother and the daughter are in Hangzhou, without each other’s knowledge. The brother even encounters the foster father. It’s the sort of coincidence that leads us to expect a reunion. Coincidences, I mentioned in an earlier entry, are fascinating narrative devices, and here the fortuitous convergence doesn’t actually pay off. But it does prepare us for the genuine reunion that will take place an hour or so later, when an earthquake hits Sichuan in 2008.

There’s a lot more to be said about Aftershock; I was struck by the fact that the children are left in the collapsing apartment because the parents have sneaked off to have sex in the husband’s truck. (So is the whole arc of suffering the punishment for a little carnality?) But just sticking with structure, we find that a cluster of ancient plot devices, fed into the established technique of crosscutting, can still find purchase in a contemporary film. In films like Aftershock, as in Hollywood’s romantic comedies and horror films and historical adventures, very old narrative conventions live on. Suitably spruced up with CGI, they still provide pleasure.

Sometimes, however, you get the sense that filmmakers in other cultures are borrowing conventions of recent Western films. This seems the case in City of Life from the United Arab Emirates. Faisal is a spoiled playboy who spends his nights with his pal Khalfan, a fistfight-prone club-hopper. Natalia is a Romanian flight attendant who gets romantically involved with an advertising man. Basu is a taxidriver with an uncanny resemblance to a Bollywood star, and so he tries to supplement his earnings by appearing in a nightclub. As all of them move through Dubai, their lives intertwine.

We have, in short, what I’ve called a network narrative. Mostly the plot lines are juxtaposed through crosscutting, but sometimes the characters in one line of action encounter those in another. Faisal is at a club on the same night as Natalia is there, with her boyfriend and her roommate. Objects circulate as well. Natalia pays Basu for a cab ride, and Basu preserves her €20 note until he has hit rock bottom. At the midpoint, an ad campaign links Natalia’s boyfriend, Faisal’s father, and Basu’s job. Many of the conventions of the “small world” network format are included, with one character remarking that Dubai is a small city. Our old friend the traffic accident (shot and cut with exceptional vividness) plays a crucial role. A refuse collector threads through the plot, turning up at unexpected times and providing an ironic coda.

Director Ali F. Mostafa mobilizes a lot of contemporary techniques, including fast motion and rapid cutting (3.6 seconds average shot length). The editing sometimes extends the crosscutting principle by flipping back and forth between two successive scenes, creating little flashforwards. For instance, when the adman Guy phones Natalia to introduce himself, we cut to them talking in a bar and then back to her listening to his sweet talk.

The anticipatory cuts lead us to expect that Guy is calling to ask her out, and Natalia will accept. This sort of cross-stitching can be found in The Godfather and other films of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and it has shown up sporadically since, but it’s rare enough to still look modern.

In cinema, network narratives can occasionally be found before the 1990s, but they’ve become far more common. I count nearly 150 films of the last twenty years employing the structure. In literature, of course, such plots go back quite far, and they formed the basis of nineteenth-century novels by the likes of Balzac, Dickens, Zola, and George Eliot. Television soap operas and ensemble series like Hill Street Blues showed that modern media’s long-form formats fit well with network storytelling. So cinema has caught up, adjusting the template to feature-length plots. City of Life shows that artists from emerging filmmaking nations can use this structure to enter a festival circuit dominated by Western norms of construction. At the same time, those artists can tailor this structure to their own ends—in this case, it seems to me, presenting Dubai as a city of emigrants ruled by a feckless leisure class.

The theatre of memory

What happens, though, when conventions of sprawling nineteenth-century novels aren’t squeezed so drastically into the usual feature length? I had a chance to find out from Vancouver’s screening of Raul Ruiz’s four-and-a-half-hour Mysteries of Lisbon. Based on an 1854 novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, a fictioneer as prolific as Ruiz himself, the film doesn’t trim off the exfoliating plot lines that we enjoy in three-deckers from the period. This being a Ruiz film, there is as well a tangible pleasure in the artifice of storytelling. The film acknowledges that all the handy coincidences, buried pasts, multiple identities, and revelations of kinship are there for our delectation.

Orphans again: João is being raised in a church school, but he has no idea of his parentage. Early on, kindly Father Dimis tells him that his mother is Angela, the countess of Santa Barbara, but her brutal husband is not his father. We are soon embarked on the extended flashback that traces the doomed love affair that results in the birth of the young hero, now named Pedro. In the course of that tale, we meet two more suspicious characters, the gypsy Salino Cabra and the hired assassin Heliodoros.

This recounted history is only the first of a cascade of flashbacks, issuing from several characters, and these gradually show deep connections among persons tied to Pedro’s past. Secondary characters in one story become protagonists of another. The young hero is gradually displaced as the center of the action by war, secret romances, rivalries, duels, and infidelities. Like Pasolini in his Trilogy of Life, Ruiz is happiest when opening up a plot detour that will eventually become a new main road.

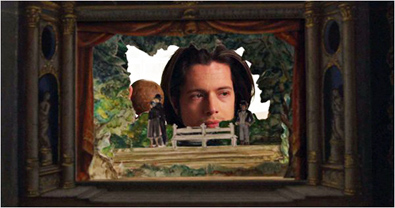

By the end, our young hero has become something of a nullity, an empty center around which aristocratic ecstasies and follies have swirled. He’s something like the Dubai of City of Hope: a point of intersection of many fates. He’s also a passive observer of scale-model dramas played out on his toy theatre stage. His voice-over narration has enwrapped the whole film, and our last glimpse of him is as merely a narrator. Pedro seems finally to realize that his entire existence has served simply to gather other people in a tangle of doomed passions.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Ruiz’s appetite for narrative is almost gluttonous; he supposedly wrote over a hundred plays in six years, and he’s made about as many films. He once told me that he thought that Postmodernism was simply a revival of the Baroque in modern dress. From Mysteries of Lisbon, it’s clear that he sees in many older narrative traditions affinities with our tastes today. Network narratives? They’ve been done, and maybe better, centuries ago. Follow the lacy tendrils of classic family-origins plots, and you’ll find a pattern as intricate as anything in Short Cuts or Pulp Fiction. More story ahead: there’s a six-hour television version.

Rumination on ruination

Ruiz understands that modernist narrative techniques, including unreliable narrators and fancy time-switches, depend upon a long tradition in at least two ways. First, very often the tradition got there first; scholars like Meir Sternberg and Robert Alter have demonstrated complex plays with chronology and point of view in the Bible and the Greek classics. Secondly, unusual plot structures may ring unexpected variations on more conventional ones. Case in point: reversed plot sequence.

Again, this seems to be something of a modern trend. The locus classicus appears to be Harold Pinter’s 1978 play Betrayal, in which, scene by scene, the plot proceeds in reverse chronology. This was filmed in 1983 and gave birth to a famous Seinfeld episode. As you know, Memento, Irreversible, and other recent films have taken up reverse-chronology plotting. Actually, however, there are several earlier instances, notably the 1934 Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (turned into a musical by Stephen Sondheim) and W. R. Burnett’s 1934 novel, Goodbye to the Past. Other examples, some going back quite far, are listed here.

Rumination, a film by Xu Ruotao in the Dragons & Tigers young directors competition at Vancouver, turns the structure to political ends. Reduced to the bare bones, the film shows a teacher, his wife, and their son caught up in the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The father falls in with a gang of Red Guard youths rampaging through the countryside. The son trails the gang at a distance and occasionally interferes with their acts of violence. These story events are arranged in blocks, with each cluster of scenes associated with a specific year. The blocks proceed backward in time, from 1976 to 1966. After a prologue, the film shows scenes of the waning of the Revolution; before the epilogue, we get a stalwart young man announcing the Revolution’s birth.

The scenes are fairly episodic and independent, so I didn’t detect the backwards structure for quite a while. But my uncertainty had another source. Xu introduces each year’s scenes with a date that is, except for one instance, not the year of the actions shown. In fact, while the segments move in reverse order, the years’ designations move in chronological order.

The opening 1976 section is labeled 1966, the 1975 section is labeled 1967, and so on up to the end, with the 1966 action designated as 1976. So we see the father’s reunion with his wife, a moment of clumsy embrace, long before he decides to leave home. As you’d expect, there’s one year in which the action and the tag coincide, 1971, and that is the only one built out of photos and film clips from the period. The year is privileged, Xu explains, because that was the year of the mysterious plane-crash death of Lin Biao, a military hero and Cultural Revolution leader who was accused of plotting Mao’s assassination.

In my viewing, the misleading dates helped conceal the reverse chronology. Confronted with so many discrete episodes of unidentified characters sprinting through the countryside, beating passersby and stealing chickens, I took the default option and assumed that the segments were chronological. Moreover, the film’s scenes play out almost entirely in overcast landscapes and decrepit factories, a landscape in which I couldn’t detect any indications of change from year to year. Watching Ruination a second time, I saw the reversal more clearly, but I also thought that some segments tease us into thinking along chronological lines. An early scene shows the father getting up in the morning (a conventional way to start a plot), saluting Chairman Mao’s statue, and reading from the Little Red Book. Yet this scene is set in 1975, after the father has returned to his wife from his Red Guard period.

Moreover, there’s some evidence that the son actually matures across the film, even though the scenes show him objectively getting younger. By the end of the plot (the earliest moment in story time) he seems to have transformed himself into a strapping young Red Guard. Supporting this construal is the fact that in the Q & A after the showing, Xu mentioned that one influence on his film’s design was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button!

Xu explained that the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution could not be comprehended through normal storytelling techniques. I suspect that viewers familiar with the relevant events and the film’s slogans, iconography, and oblique citations (even to Godard) could follow the backwards sequencing. But I suspect that those viewers would need a sense of the historical chronology to grasp the 3-2-1 order of the plot. It seems to me that Xu, known until now as a painter, has shown how an innovative approach to plot structure relies on conventional responses even as it thwarts them.

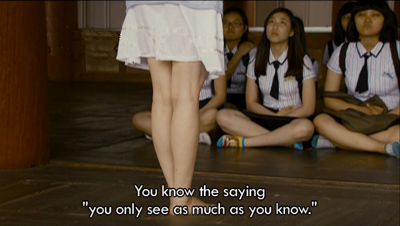

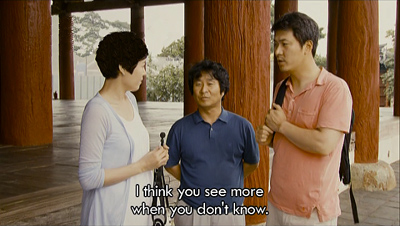

Hahaha indeed

Hong Sangsoo has been one of the leading experimenters with narrative in today’s Asian cinema. My two favorites, The Power of Kangwon Province (1998) and The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) have engaged the viewer in playful puzzlement about how story lines can collide or slip sideways, how our memory of earlier scenes’ action can be tested and found faulty. I haven’t been deeply engaged by his recent forays into more straightforward drama/comedy, such as The Woman on the Beach (2006), but his two latest features, both from this year and both on display in Vancouver, completely satisfied my hunger for intriguing plot structures.

It’s an unspoken convention of recounted-flashback tales that even though the events are told by A, B learns everything that we do—everything, that is, that we can see or hear in the flashback. But Hahaha decouples the verbal recounting from the visual presentation. Here listener B definitely does not grasp what we witness happening onscreen in the tale as told.

Hahaha is a parallel-protagonist tale. Two pals meet for some drinking before one, Munkyung, leaves South Korea for Canada. Through a series of flashbacks, they regale each other with their recent adventures, mostly amorous. The plot is structured as two alternating streams, crosscutting one man’s tale with the other’s and usually returning to the framing situation of their drinking bout. But because we can see what each one recounts, we come to realize that both stories are populated by the same people, notably the tempting female tour guide Seongok. And those people have their own relationships, which we must piece together out of the glimpses we get in each man’s tale.

Neither Munkyung nor his pal Jungshik has a clue that they are part of a fairly tight circle. The result, as usual with Hong, is a comedy of ironic misunderstanding and the puncturing of male pretension. Hahaha can also be seen as his response to the rise of network narratives. Characters in such a film don’t usually realize the larger mosaic they’re part of; the intersecting lives in City of Life transform one another unwittingly. Normally that lack of awareness isn’t the main point of the film. Here it is, and it’s wrung for classic humor at the protagonists’ expense.

In Oki’s Movie, Hong gives us another fractured plot, but now in the form of four short films. They center on three characters: Song, a film director turned professor; his student Jingu; and Oki, the woman both men are interested in. The raggedy credits of each short suggest handmade movies, but what we see in each one is the polished style familiar from Hong himself, including his current interest in abrupt zooms.

The four-part structure is far from transparent. It might be taken as a series of episodes from the trio’s lives. The first film, “Specters of the New World,” which presents Jingu as a professor himself, would have to take place in the present, and the following three would then be presenting flashbacks to the Jingu-Oki-Song triangle. In that case, the first segment would prove that Jingu did not wind up with Oki, as he’s married to another woman.

Perhaps, though, all four films are free hypothetical variations on the central situation. I’m not sure that we can easily arrange the events in the second, third, and fourth episodes chronologically. The films could be presenting successive groups of events, or events scattered across a single time span and then selectively gathered around one of the central characters. The first episode is largely organized around Jingu’s range of knowledge; the second is confined to professor Song; and the third is explicitly presented as Oki’s own thoughts. Earlier Hong films have offered us contrasting, even incompatible plots built out of a core group of characters. Oki’s Movie may be using the framing conceit of student films (none of which is plausible as a student film) to give us a suite of variants on the love triangle.

The idea of ambiguous variation is made explicit in the final mini-film, “Oki’s Movie.” It’s a sustained exercise in—yes, again—crosscutting. This episode alternates two excursions to Mount Acha, one with each man. Shot by shot, we see different courtship styles and we hear her differing reactions to her two lovers. Was she dating both men at once? When did the two excursions take place? Which one occurred first? As these questions are juggled, we get a rapid checklist of Oki’s attitudes, in voice-over, toward both these minor-key losers.

In both Hahaha and Oki’s Movie, Hong takes what’s offered by tradition—in this case, the romantic comedy and the conventions of flashbacks, crosscutting, and restricted narration—and creates a fresh structure. The play of novelty and norm is engrossing in itself, apart from the vagaries of the drama. Our appetite for narrative will always be whetted when directors find ways to whip up something new out of familiar ingredients.

For more on the three dimensions of film narrative, as well as discussion of the principles of network construction, see my Poetics of Cinema. There’s more discussion of flashbacks in film in this entry. On early narrative structure, see Meir Sternberg’s Poetics of Biblical Narrative and Robert Alter’s Art of Biblical Narrative, as well as Sternberg’s discussion of The Odyssey in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. For a sharp-eyed consideration of Oki’s Movie, see Andrew Tracy’s review at Cinema Scope.

Oki’s Movie.