Archive for the 'Directors: Fincher' Category

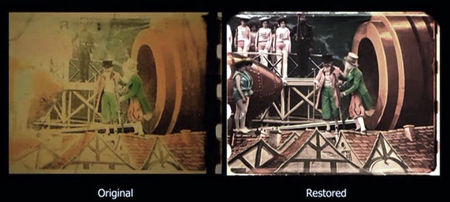

Stuck inside these four walls: Chamber cinema for a plague year

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Privacy is the seat of Contemplation, though sometimes made the recluse of Tentation… Be you in your Chambers or priuate Closets; be you retired from the eyes of men; thinke how the eyes of God are on you. Doe not say, the walls encompasse mee, darknesse o’re-shadowes mee, the Curtaine of night secures me… doe nothing priuately, which you would not doe publickly. There is no retire from the eyes of God.

Richard Brathwaite, The English Gentlewoman (1631)

DB here:

We’re in the midst of a wondrous national experiment: What will Americans do without sports? Movies come to fill the void, and websites teem with recommendations for lockdown viewing. Among them are movies about pandemics, about personal relationships, and of course about all those vistas, urban or rural, that we can no longer visit in person. (“Craving Wide Open Spaces? Watch a Western.”)

Cinema loves to span spaces. Filmmakers have long celebrated the medium’s power to take us anywhere. So it’s natural, in a time of enforced hermitage, for people to long for Westerns, sword and sandal epics, and other genres that evoke grandeur.

But we’re now forced to pay more attention to more scaled-down surroundings. We’re scrutinizing our rooms and corridors and closets. We’re scrubbing the surfaces we bustle past every day. This new alertness to our immediate surroundings may sensitize us to a kind of cinema turned resolutely inward.

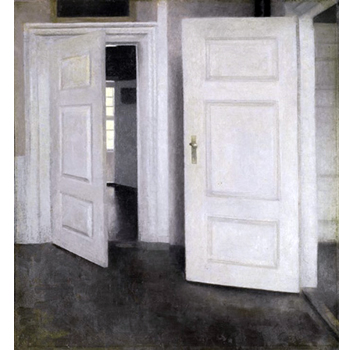

Long ago, when I was writing a book on Carl Dreyer, I was struck by a cross-media tradition that explored what you could express through purified interiors. I called it “chamber art.” In Western painting you can trace it back to Dutch genre works (supremely, Vermeer). It persisted through centuries, notably in Dreyer’s countryman Vilhelm Hammershøi (below).

Plays were often set in single rooms, of course, but the confinement was made especially salient by Strindberg, who even designed an intimate auditorium. For cinema, the major development was the Kammerspielfilm, as exemplified in Hintertreppe (1921), Scherben (1921), Sylvester (1924), and other silent German classics. Kristin and I talk about this trend here and here.

In the book I argued that Dreyer developed a “chamber cinema,” in piecemeal form, in his first features before eventually committing to it in Mikael (1924) and The Master of the House (1925). Two People (1945) is the purest case in the Dreyer oeuvre: A couple faces a crisis in their marriage over the course of a few hours in their apartment. (Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem available with English subtitles.) But you can see, thanks to Criterion, how spatial dynamics formed a powerful premise of his later masterpieces Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964).

Dreyer wasn’t alone. Ozu tried out the format in That Night’s Wife (1930), swaddling a husband, wife, child, and detective in a clutter of dripping laundry and American movie posters.

Bergman exploited the premise too, in films like Brink of Life (1958), Waiting Women (1952), his 1961-1963 trilogy, and Persona (1966). (All can be streamed on Criterion.)

Chamber cinema became an important, if rare expressive option for many filmmaking traditions. Writers and directors set themselves a crisp problem–how to tell a story under such constraints?

The challenge is finding “infinite riches in a little room.” How? Well, you can exploit the spatial restrictiveness by confining us to what the inhabitants of the space know. Limiting story information can build curiosity, suspense, and surprise. You can also create a kind of mundane superrealism that charges everyday objects with new force.

On the other hand, you need to maintain variety by strategies of drama and stylistic handling. Chamber cinema–wherever it turns up–offers some unique filmic effects, and maybe sheltering in place is a good time to sample it.

Herewith a by no means comprehensive list of some interesting cinematic chamber pieces. For each title, I link to streaming services supplying it.

Bottles of different sizes

From David Koepp I learned that screenwriters call confined-space movies “bottle” plots. There’s a tacit rule: The audience understands that by and large the action won’t stray from a single defined interior. In a commentary track for the “Blowback” episode of the (excellent) TV show Justified, Graham Yost and Ben Cavell discuss how TV series plan an occasional bottle episode, and not just because it affords dramatic concentration. It can save time and money in production.

Usually the bottle consists of more than a single room. The classic Kammerspielfilms roam a bit within a household and sometimes stray outdoors. But their manner of shooting provides a variety of angles that suggest continuing confinement. Dreyer went further in The Master of the House. He built a more or less functioning apartment as the set, then installed wild walls that let him flank the action from any side. Then editing could provide a sense of wraparound space.

The variations in camera setups throughout the film are extraordinary. Dreyer would create more radically fragmentary chamber spaces in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), while his later films would use solemn, arcing camera movements to achieve a smoother immersive effect. (For more on Dreyer’s unique spatial experimentation, here’s a link to my Criterion contribution on Master of the House. I talk about the tricks Dreyer plays with chamber space in Vampyr in an “Observations” supplement on the Criterion Channel.)

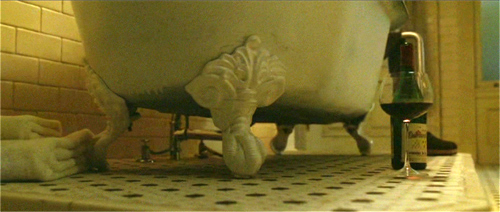

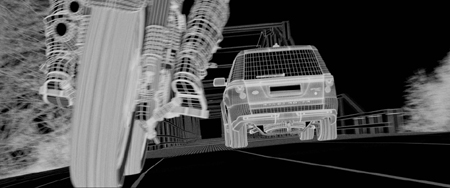

Likewise, Koepp’s screenplay for Panic Room allows David Fincher to move 360 degrees through several areas of a Manhattan brownstone. The film also offers a fine example of how our awareness of domestic details gets sharpened by a creeping camera.

Trust Fincher to find sinister possibilities in a dripping bathtub leg and a kitchen island.

Confined to quarters

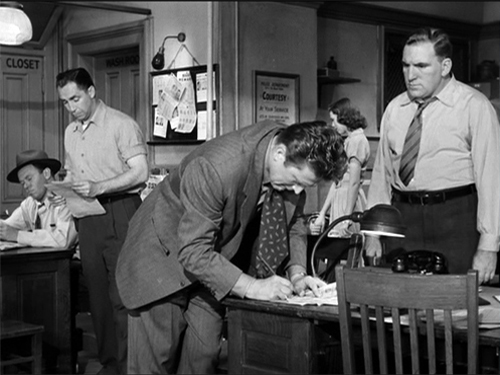

Detective Story (1951).

Many chamber movies are based on plays, as you’d expect. Unlike most adaptations, though, they don’t try to “ventilate” the play by expanding the field of action. Or rather, as André Bazin pointed out, the expansion is itself fairly rigorous. They don’t go as far afield as they might.

Bazin praised Cocteau’s 1948 version of his play Les parents terribles (aka “The Storm Within”) for opening up the stage version only a little, expanding beyond a single room to encompass other areas of the apartment. This retained the claustrophobia, and the sense of theatrical artifice, but it spread action out in a way that suited cinema’s urge to push beyond the frame. The freedom of staging and camera placement is thoroughly “cinematic” within the “theatrical” premise.

Depending on how you count, Hitchcock expanded things a bit in his adaptation of Dial M for Murder. Apart from cutting away to Tony at his club, Hitchcock moved beyond the parlor to the adjacent bedroom, the building’s entryway, and the terrace.

An earlier entry on this site talks about how 3D let Sir Alfred give an ominous accent to props: a particularly large pair of scissors, and a more minor item like the bedside clock.

Hitchcock gave us a parlor and a hallway in Rope (1948), but when Brandon flourishes the murder weapon, the framing audaciously reminds us that we aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen.

Bazin did not wholly admire William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951), despite its skill in editing and performances; he found it too obedient to a mediocre play. True, the film doesn’t creatively transform its source to the degree that Wyler’s earlier adaptation of The Little Foxes (1941) did; Bazin wrote a penetrating analysis of that film’s remarkable turning point. Detective Story is more obedient to the classic unities, confining nearly all of the action to the precinct station. Although I don’t think Wyler ever shows the missing fourth wall, he creates a dazzling array of spatial variants by layering and spreading out zones of the room. In his prime, the man could stage anything fluently.

As Bazin puts it: “One has to admire the unequaled mastery of the mise-en-scène, the extraordinary exactness of its details, the dexterity with which Wyler interweaves the secondary story lines into the main action, sustaining and stressing each without ever losing the thread.”

Some films are even more constrained. 12 Angry Men (1957), adapted from a teleplay, is a famous example. Once the jury leaves the courtroom, the bulk of the film drills down on their deliberation. Again, the director wrings stylistic variations out of the situation; Lumet claims he systematically ran across a spectrum of lens lengths as the drama developed.

But you don’t need a theatrical alibi to draw tight boundaries around the action. Rear Window (1954), adapted from a fairly daring Cornell Woolrich short story, is as rigorous an instance of chamber cinema as Rope. Here Hitchcock firmly anchors us in an apartment, but he uses optical POV to “open out” the private space.

With all its apertures the courtyard view becomes a sinister/comic/melancholy Advent calendar.

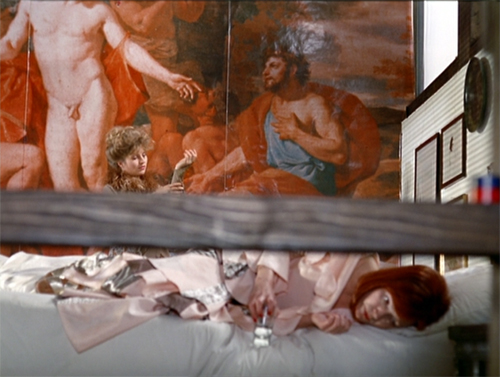

Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) denies us this wide vantage point on the outside world. This space seems almost completely enclosed. But Fassbinder finds a remarkable number of ways to vary the set, the camera angles, and the costumes. We’re immersed in the flamboyant flotsam of several women’s lives. The result is a cascade of goofily decadent pictorial splendors.

It’s virtually a convention of these films to include a few shots not tied to the interiors. At the end, we often get a sense of release when finally the characters move outside. That happens in 12 Angry Men, in Panic Room, in Polanski’s Carnage (2011) , and many of my other examples. Without offering too many spoilers, let’s say Room (2015) makes architectural use of this option.

On the road and on the line

Filmmakers have willingly extended the bottle concept to cars. The most famous example is probably Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), which secures each scene in a vehicle and mixes and matches the passengers across episodes. The strictness of Kiarostami’s camera setups exploit the square video frame and always yield angular shot/reverse shots. They reveal how crisp depth relations can be activated through the passing landscape or in story elements that show up in through the window.

Perhaps Kiarstami’s example inspired Danish-Swedish filmmaker Simon Staho. His Day and Night (2004) traces a man visiting key people on the last day of his life, and we are stuck obstinately in the car throughout. This provides some nifty restriction, most radically when we have to peer at action taking place outside.

Staho’s Bang Bang Orangutang (2005), a portrait of a seething racist, takes up the same premise but isn’t quite so rigorous. We do get out a bit, but the camera stays pretty close to the car. I discuss Staho’s films a little in a very old entry.

Like autos, telephones provide a nice motivation for the bottle, as Lucille Fletcher discovered when she wrote the perennial radio hit, “Sorry, Wrong Number.” The plot consists of a series of calls placed by the bedridden woman, who overhears a murder plot. The film wasn’t quite so stringently limited, but the effect is of the protagonist at the center of several crisscrossed intrigues.

A purer case is the Rossellini film Una voce umana (1948), in which a desperate woman frantically talks with her lover. It relies on intense close-ups of its one player, Anna Magnani.

It’s an adaptation of a Cocteau play, which Poulenc turned into a one-act opera. In all, the duration of the story action is the same as the running time.

I wish Larry Cohen’s Phone Booth displayed a similarly obsessive concentration, but we do have the Danish thriller The Guilty, where a police dispatcher gets involved in more than one ongoing crime. We enjoyed seeing it at the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival.

And of course car and phone can be combined, as they are in Locke (2013)–another play adaptation. Tom Hardy plays a spookily calm businessman driving to a deal while taking calls from his family and his distraught mistress. Those characters remain voices on the line while he tries to contend with the pressures of his mistakes.

House arrest, arresting houses

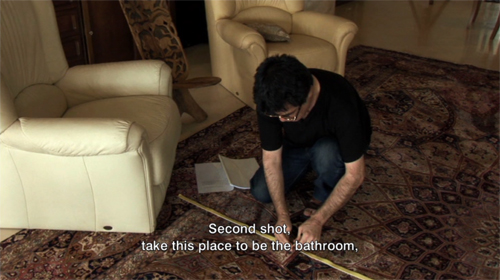

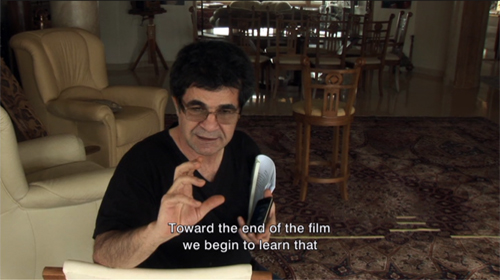

Sometimes you must embrace the chamber aesthetic. In 2010 the fine Iranian director Jafar Panahi was forbidden to make films and subjected to house arrest. Yet he continued to produce–well, what? This Is Not a Film (2012) was shot partially on a cellphone within (mostly) his apartment.

Wittily, he tapes out a chamber space within his apartment. Then he reads a script to indicate how absent actors could play it and how an imaginary camera could shoot it.

But his imaginary film still isn’t an actual film, so he hasn’t violated the ban. So perhaps what we have is rather a memoir, or a diary, or a home video? Panahi’s virtual film (that isn’t a film) exists within another film that isn’t a film. Yet it played festivals and circulates on disc and streaming. The absurdity, at once touching and pointed, suggests that through playful imagination, the artist can challenge censorship.

Panahi slyly pushed against the boundaries again with Closed Curtain (2013, above). Shot in his beach house, it strays occasionally outside. Next came Taxi (2015), in which Panahi took up the auto-enclosed chamber movie, with largely comic results.

More recently, he has somehow managed to make a more orthodox film, 3 Faces (2018), which considers the situation of people in a remote village.

The chamber-based premise needn’t furnish a whole movie. As in Room, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) is tightly concentrated in its first half. We are in two enclosures, a house and a train. The film then bursts out into a rushed, wide-ranging investigation. Large-scale or less, the chamber strategy remains a potent cinematic force.

They say that the last creatures to discover water will be fish. We move through our world taking our niche for granted. Cinema, like the other arts, can refocus our attention on weight and pattern, texture and stubborn objecthood. We can find rich rewards in glimpses, partial views, and little details. Chamber art has an intimacy that’s at once cozy and discomfiting. Seeing familiar things in intensely circumscribed ways can lift up our senses.

So take a break from the crisis and enjoy some art. But return to the world knowing that for Americans this catastrophe is the result of forty years of monstrous, gleeful Republican dismantling of our civil society. Rebuilding such a society will require the elimination of that party, and the career criminal at its head, as a political force. This pandemic must not become our Reichstag fire.

Yeah, I went there.

Thanks to the John Bennett, Pauline Lampert, Lei Lin, Thomas McPherson, Dillon Mitchell, Erica Moulton, Nathan Mulder, Kat Pan, Will Quade, Lance St. Laurent, Anthony Twaurog, David Vanden Bossche, and Zach Zahos. They’re students in my seminar, and they suggested many titles for this blog entry.

Bazin’s comments on Detective Story come in his 1952 Cannes reportage, published as items 1031-1033, and as a review (item 1180), in Écrits complets vol. I, ed. Hervé Joubert-Laurencin (Paris: Macula, 2018), pp. 918-922, 1059. My quotation comes come from the review, where he does grant that Wyler is the Hollywood filmmaker “who knows his craft best. . . . the master of the psychological film.”

The tableau style of the 1910s probably helped shift Dreyer toward the chamber model, which he learned to modify through editing. I discuss Dreyer’s relation to that style in “The Dreyer Generation” on the Danish Film Institute website. Also related is the web essay, “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic.”

Some other examples could be mentioned, but I didn’t find them on streaming services in the US. It would be nifty if you could see the tricks with chamber space in Dangerous Corner (1934); fortunately it plays fairly often on TCM. There’s also Duvivier’s Marie-Octobre (1959), a tense drama about the reunion of old partisans.

I especially like the 1983 Iranian film, The Key, directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and scripted by Kiarostami. It’s a charming, nearly wordless story of how a little boy tries to manage household crises when Mother is away. It has the gripping suspense that is characteristic of much Iranian cinema, and the boy emerges as resourceful and heroic (though kind of messy). Kids would like it, I think.

Also, I’ve neglected Asian instances. Maybe I’ll revisit this topic after a while.

P.S. 1 April 2020: Thanks to Casper Tybjerg, outstanding Dreyer scholar, for corrections about the nationality of The Guilty and the Staho films.

Gertrud (1964).

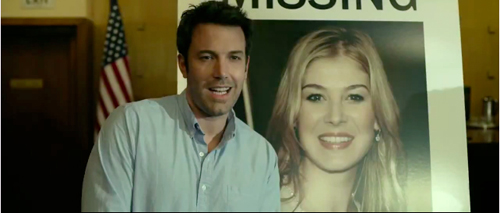

Gone Grrrl

Gone Girl.

DB here:

How are contemporary movies, even this weekend’s releases, indebted to earlier traditions? Sometimes Kristin and I tackle this question. We’re not (I hope) trying to impress you as connoisseurs of esoteric knowledge. We’re definitely not trying to play down a movie’s originality by yawning and shrugging and murmuring “We’ve seen it all before.” Instead, as historians of film forms and styles, we’re interested in the ways that current movies reconfigure techniques that have been circulating across cinema history.

A lot of those techniques involve storytelling. So we’re obliged to study narrative conventions and innovations across the decades. And since cinema isn’t sealed off from other media, we’re curious about how films borrow narrative devices from other arts. The borrowing isn’t only one-way, of course; cinema has influenced storytelling in other media too.

Mystery and suspense stories have long attracted people who study narrative (“narratologists”) because such fictions depend almost completely on storytelling subterfuge. True, other genres can include false leads, or misleading ellipses, or questionable flashbacks, or strange point-of-view switches. But mystery-based plots require them in a way that science-fiction or romance plots don’t. In mystery stories, characters keep secrets from each other and the author must keep secrets from the audience as well.

Which brings us to Gone Girl.

Detective stories and thrillers are one-off demos of narrative trickery, so studying them can teach us something about how we understand stories. We’ve made a stab at showing this elsewhere on this site (see our codicil). But now comes a flagrant instance of narrative manipulation that has set people talking ever since Gillian Flynn’s novel was published.

That novel and the film she wrote and David Fincher directed throw into relief how popular narratives revise devices from earlier traditions. As narratologists in training, we’re keen as well to understand how the film creates its particular effects. I can’t answer all such questions here, but I offer some thoughts on the film’s storytelling strategies, with notes on how those adapt earlier ones.

Of course beyond this point there are spoilers for Gone Girl. I also heedlessly spoil Leave Her to Heaven, both book and film.

Two plots for the price of one

The domestic thriller usually involves a couple living together—a husband and wife, or in modern times a pair of lovers. The conflict might center on them or on a third threatening figure. A very common option focuses the plot on either a murderous husband or a murderous wife.

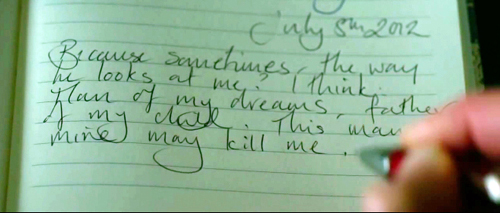

Gone Girl, both novel and film, starts with a classic murderous husband situation. Amy disappears. She has made her husband Nick discontented and angry, and he has started an affair with one of his students, Andie. Thanks to a crucial ellipsis in showing the first day, what Nick has been doing during Amy’s disappearance is skipped over. When Amy vanishes, apparently leaving a pool of blood behind, Nick is the prime suspect.

If your plot centers on a murderous husband, you have a choice. You can let the audience in on his plans, as in Rage in Heaven (1941), Conflict (1945), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), and, much more recently, Safe Haven (2013). But Gone Girl doesn’t unequivocally show that Nick has killed Amy, or even plotted to kill her.

The second alternative for handling a murderous-husband situation is to keep it mysterious, chiefly by confining us to the wife’s range of knowledge. This ploy was made famous in Francis Iles’ novel Before the Fact (1932) and in Hitchcock’s adaptation Suspicion (1941). The premise is: I think my husband is trying to kill me. The 1940s crystallized this plot format in films like Secret Beyond the Door (1948) and Sleep, My Love (1948), and it survived for decades, in films from Sleeping with the Enemy (1991) to Side Effects (2013).

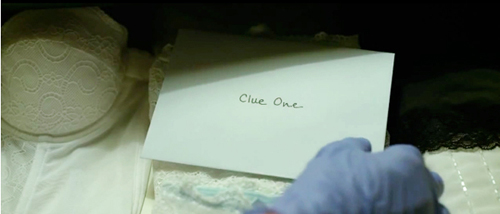

The first half of Gone Girl uses Amy’s diary entries to present the familiar arc of suspicion. The Dunnes’ marriage frays and she becomes increasingly frightened. Just before their fifth anniversary she buys a gun for self-defense. In her last entry she records her fear that he will kill her.

Nick looks pretty guilty at first, but with the whiff of doubt, another convention kicks in. That’s the one that film scholar Diane Waldman has called the “helper male.” If there’s another man nearby able to rescue the wife and play the role of a future romantic partner, then the husband is likely to be exposed as villainous. Examples are the Hollywood version of Gaslight (1944) and Sleep, My Love. If no helper is visible, then we’re likely to have a plot based on the wife’s misperception of the husband, as in Suspicion and Secret Beyond the Door. In Gone Girl’s first half, Amy seems to have no recourse to a helper male. This fact might dissolve some suspicion attached to Nick. Maybe, some viewers might ask, Amy was indeed abducted by a third party?

So much for the convention of the killer husband. A second type of domestic thriller, rarer than the first, centers on a homicidal woman. She shows up in the great Vera Caspary’s novel Bedelia (1945; made into a British feature in 1946) and in such films as Ivy (1947), A Woman’s Vengeance (1948), and Too Late for Tears (1949).

An especially shocking 1940s specimen of the killer wife is the cool, irresistible Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven (novel 1944, film 1945). At first, Ellen wishes no harm to her husband Dick; she just wants to eliminate anybody with whom she’d have to share him. She lets his little brother drown, and, fearing that her unborn child will come between them, she flings herself downstairs and induces a miscarriage. Eventually, though, she turns her wrath on Dick. (Ellen’s most extreme tactic I’ll save for later, as it looks forward to Gone Girl.)

An especially shocking 1940s specimen of the killer wife is the cool, irresistible Ellen Berent in Leave Her to Heaven (novel 1944, film 1945). At first, Ellen wishes no harm to her husband Dick; she just wants to eliminate anybody with whom she’d have to share him. She lets his little brother drown, and, fearing that her unborn child will come between them, she flings herself downstairs and induces a miscarriage. Eventually, though, she turns her wrath on Dick. (Ellen’s most extreme tactic I’ll save for later, as it looks forward to Gone Girl.)

What is exceptionally clever about Gone Girl, again both novel and film, is that its second half replaces the murderous-husband schema with a revelation of Amy as a spider woman. Angry with Nick’s failure to sustain the role of the man she wants him to be, she has elaborately prepared an apparent murder that will lead police to suspect him. Here Flynn revives an old reliable of mystery plots, the faked death.

Amy has dovetailed three sets of clues for the police. There are clues she leaves in the treasure hunt, a little-girl game she obliges Nick to play every anniversary. This time, though, the hints point to uncomfortable aspects of their relationship. A second array of clues—imperfectly cleaned bloodstains, obviously faked signs of abduction, big credit-card purchases in his name—make Nick seem a lying killer. Then there is Amy’s faked diary, which she arranges to appear at just the moment that would harm him most. The diary entries initially coax us toward the Suspicion situation, seeming to provide a record of a wife’s growing apprehension of danger.

Knowing that a dead body will clinch the uxoricide case against Nick, Amy initially considers doing away with herself and letting the corpse be found in the river. Interestingly, this vindictive-suicide motif is the extreme tactic Ellen Berent pursues in Leave Her to Heaven. She poisons herself and sets up her sister Ruth, who’s in love with Dick, as her murderer. Like Amy, she has left a damning testament behind: a letter that will lead the police to arrest Ruth. Like Amy, Ellen has dropped a judicious trail of clues prepared well in advance.

So Flynn’s novel and screenplay shrewdly couple two thriller plot schemes, the murderous husband and the lethal wife. As an extra fillip, once Amy has been robbed by the desperate Jeff and Greta, she calls rich Desi Collings and convinces him of the threat Nick supposedly represents. In effect, Amy re-launches the lethal-husband scenario and recruits Desi as her helper male. Of course in most such plots, the helper male rescues the woman from peril. Here she is the peril.

Thank you, Mr. Griffith

So far I’ve talked mostly about what I called, in an earlier entry and in an online essay, the story world. But I couldn’t keep clear of two other dimensions of film narrative: plot structure and narration. I’ll talk about these more now.

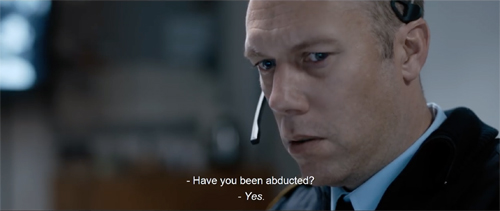

I’ve indicated that Flynn’s novel breaks fairly neatly into two halves, splitting when Amy reveals that she hasn’t been kidnapped or killed. (“I’m so much happier now that I’m dead.”) The film, though, is a little less tidy.

As recidivist readers of this site know, Kristin has proposed that for decades Hollywood feature films have tended to break into several distinct parts that don’t fully correspond to the three acts of screenwriting manuals. The core structure for a normal feature involves four parts. Kristin labels these the Setup, the Complicating Action, the Development, and the Climax, with a brief epilogue tacked on. They’re determined by turning points that alter the goals that the characters pursue, and they tend to run twenty-five to thirty minutes or so.

Kristin argues in Storytelling in the New Hollywood that short films can delete a middle chunk, and long films can iterate one. For instance, she finds that Amadeus has two Development sections. Picking up on this, I proposed in The Way Hollywood Tells It that The Godfather (a very long movie) has not only two Developments but two Complicating Actions.

The film version of Gone Girl offers an interesting extension of the basic pattern. The film runs 144 minutes without credits. I divide up the first 126 minutes according to major turning points.

Setup. After the prologue close-up of Amy, she goes missing and Nick begins to conceal things from the police (roughly the first half hour).

Complicating action, in which the main character conceives a new goal. Now that public opinion casts Nick as the killer and Andie becomes another secret he must conceal, he must try to convince all he’s innocent. He fails. Boney summarizes the case against him at about 60 minutes in. Then he discovers the luxury goods stuffed into his sister Margo’s shed and he realizes that he’s been set up.

Development, in which backstory is provided, the protagonist confronts more problems, and many delays are set up. As Amy drives away from town and assumes a new identity, her Cool Girl monologue confirms for us that she has framed Nick. She hides in the motor court and strikes up an uneasy friendship with Greta and Jeff. While Nick engages Tanner Bolt as attorney and learns of Amy’s earlier framing of O’Hara, Amy calls Desi Collings for help. Nick has agreed to go on Sharon Schieber’s show.

Once we learn that Amy has faked her diary and loaded it with lies, we follow her stratagems after the first day. Gradually her life on the road syncs up with the progress of Nick’s situation, so that via crosscutting they eventually watch the TV coverage simultaneously.

Development sections tend to run a little long, and this one needs a chunk of backing-and-filling to explain Amy’s scheme. This part ends, I think, around the 104-minute mark, when Andie at a press conference confesses her affair with Nick while Amy accepts sanctuary at Desi’s lake house. Now Nick must take the initiative and fight back, while Amy must concoct a new plan for her new circumstances.

Climax: Here a plot culminates in success or failure, goals definitely achieved or not. Nick does well in his Sharon Schieber interview, but almost immediately the police discover the loot in Margo’s shed and confront him with the diary. He’s arrested. It’s his darkest moment so far. Meanwhile, Amy has become Desi’s prisoner. But Nick’s TV performance has convinced her that he’s ready to resume playing her ideal man. Accordingly, with typically surgical preparation, she kills Desi and returns home, announcing her escape from sex slavery. She comes back at about the 126-minute mark.

Were this a normal film, things would end here, with the couple restored; we’d need only a gloating tag showing humiliated police. Amy’s revelation of her scheme at 65:00 would then become a neat midpoint. But the film has almost twenty more minutes to run.

Is this section a protracted epilogue? Some viewers seem to take it as such, and to find it draggy, but it’s structurally necessary. I think it’s fruitful to see Gone Girl as having two climaxes.

Two climaxes for the price of one

The double climax in Gone Girl, I think, occurs because the film has a tandem structure from the start. The first hour alternates scenes involving Nick’s search for Amy with brief flashbacks triggered by shots of Amy writing in her diary. The diary supplies what we initially take to be exposition about their meeting, falling in love, getting married, losing their jobs, and moving to Missouri. These past scenes are sandwiched in between present-time scenes of the inquiry into Amy’s disappearance. The Griffith of Intolerance, not to mention the Christopher Nolan of The Prestige, would enjoy the extent to which book and film rely on large-scale crosscutting between protagonist and antagonist.

The duplex story lines lead to two turning points, one assigned to each major character. At 65 minutes, Nick’s discovery of the fancy purchases in Go’s shed changes his goal: He now must prove that Amy has set him up. At the same juncture, the revelation that Amy is on the road sets up her new goal of escape—at first, she thinks, to suicide but then to a life free of Nick, who seems safely en route to the death house.

Given the dual line of action, we have a first climax that puts Nick in jail and shows Amy killing Desi, which ends her flight. Her return provides a first phase of resolution for the overall action: Back home, she spins a new narrative for the media, one in which she “fought her way back” to her husband.

But we don’t have full resolution. Nick still has the goal of proving that Amy faked her disappearance, and now he must also show that she murdered Desi in cold blood. In addition, his rage against his wife’s frame-up threatens to make him the homicidal husband she painted in her diary. Will he be driven to kill her, as he sometimes indicates he’d like to? Meanwhile, Amy’s goal of reunion isn’t fully achieved. She still must evade punishment (Boney the cop is suspicious) and she must also persuade Nick to back up her rigged story of his abusive and spendthrift ways.

So a second climax shows Amy thwarting Nick’s goals. She blocks his efforts to reveal the truth and won’t allow a divorce. She retained Nick’s stored semen when they were trying to conceive a child, and she has impregnated herself. She will keep his son from him if he tries to make trouble. Nick accepts her frame-up and the couple become, as he says in their final TV interview, “partners in crime.” If you assume that Nick is the film’s protagonist and Amy the antagonist, we have that rare mainstream movie in which the antagonist wins.

Some critics have called the book and the film Hitchcockian, and film geeks will notice the midpoint giveaway as similar to that in Vertigo. More generally, the complicit couple exemplifies the transfer-of-guilt dynamic we find in Shadow of a Doubt, Strangers on a Train, and other of the Master’s films.

But this last quality isn’t unique to Hitchcock, or Flynn-Fincher. In Leave Her to Heaven, Dick becomes an accomplice to Ellen’s act of drowning his brother. He keeps quiet for the sake of the child he thinks she is carrying. As a result, the novel gives us a passage that could come straight from Gone Girl, on the page or on the screen.

And she said in serene and level tones: “But you lied to protect me, so—we share the guilt. That binds us together. We can never escape that now.” After a moment she added: “So we must go on together, wearing a mask for the world, being honest only with ourselves.”

Look who’s talking, or not

In both film and novel, Gone Girl’s large-scale plot patterns—the wedged-in diary entries, the ABAB attachment to characters, the cross-stitched timelines—are enhanced by choices about narration. I take narration to be not only voice-over sound but the moment-by-moment flow of story information. That flow is regulated by cinematic techniques, orchestration of point of view, and kindred strategies.

Now we encounter some differences between film and literature as storytelling media. For instance, in the novel the parallel plotlines are rendered in first-person narration, alternating accounts from Nick and Amy. Amy’s fourteen diary entries are motivated as the sort of things one enters in a private journal, whereas Nick’s aren’t presented as him telling anyone his tale. When Amy’s diary is revealed as a hoax, she continues to recount events, and still in present tense, as if she couldn’t shake the habit. Nick, however, continues to tell us what happened in the past tense. This sort of difference is rather hard to achieve in film, unless you have two continual voice-over narrators. This option Flynn and Fincher decline, probably in the interests of clarity.

Both the alternation and the variation in tense have a long novelistic past. Dickens’ Bleak House (1853) switches between chapters in third-person narration in the present tense and chapters in first-person past. The device of alternating viewpoints was picked up in twentieth-century modernism (notably Faulkner’s books) and popular genres as well. A simple example is Philip MacDonald’s 1933 mystery, X v. Rex, which switches between first-person letters written by a serial killer to the police and third-person accounts of the efforts to track him/her down. Somewhat fancier is Anita Boutell’s Death Has a Past (1939), which takes a series of scenes transpiring across one week and sandwiches among them bits of a confession written by the killer afterward—“flashforwards,” in effect.

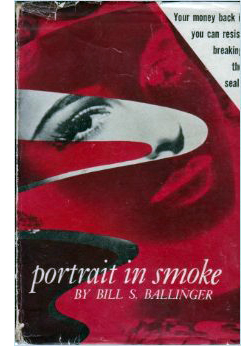

To go back to Leave Her to Heaven, Ben Ames Williams’ original novel alternates chapters filtered through the consciousness of husband, wife, brother, and sister, although all are treated in the third person. At about the same time, mystery writer Bill S. Ballinger gained notoriety for alternating chapters told from two characters’ viewpoints in two different time frames. Examples are Portrait in Smoke (1950) and The Tooth and the Nail (1955), the latter of which also toggles between first- and third-person discourse. More recently, in novels like Rebel Island (2007), Rick Riordan has intercut first- and third-person chapters.

To go back to Leave Her to Heaven, Ben Ames Williams’ original novel alternates chapters filtered through the consciousness of husband, wife, brother, and sister, although all are treated in the third person. At about the same time, mystery writer Bill S. Ballinger gained notoriety for alternating chapters told from two characters’ viewpoints in two different time frames. Examples are Portrait in Smoke (1950) and The Tooth and the Nail (1955), the latter of which also toggles between first- and third-person discourse. More recently, in novels like Rebel Island (2007), Rick Riordan has intercut first- and third-person chapters.

Journals and assembled documents have been one standard way that classic novels have been organized, and shrewd writers have exploited many possibilities. I think of the moment in The Woman in White (1860) in which a long and engrossing account written by a character in peril is revealed, only at the end, as being read by her adversary. More specifically, a major Flynn trick—the discovery that the diary mixes reliable accounts of events with false ones—has one major precedent. It occurs in a famous 1938 mystery novel that, for once, I will not spoil by naming. Here the diary in the first section is intended to be found by investigators and to cover up the identity of a killer.

This isn’t to call Flynn unoriginal; she has come up with a new variant of these narrational conventions. The point is simply that once you work in the realm of the mystery thriller, you will probably be seeking out ways to mislead the reader, and some of those stratagems will have a kinship with your predecessors. More generally, all narrative traditions exfoliate. Storytellers are constantly experimenting with new ways to engage us, and it would be surprising if two authors, both bent on achieving similar effects, didn’t occasionally hit on similar devices. Just as Flynn welded together two domestic-murder plot premises, she recast traditions of shifting, unreliable narration.

In the novel, the two first-person accounts, Nick’s and Amy’s, restrict our knowledge to each one’s perspective. Which isn’t to say that each is transparent. Nick will sometimes report his dialogue with the speech tag, “I lied.” This teases us to wonder what he’s holding back from the cops. Interestingly, confessing lies makes him a more reliable narrator, because he’s confiding in us. This has the effect of making us trust his claims about wanting children, not beating up Amy, and so on. By contrast, Amy’s chipper narration seems completely open about her feelings, but many of those entries are revealed as part of her murder masquerade. Her unreliability, though, seems chiefly confined to the diary entries; once she’s on her own, she seems to be reporting her sociopathic reactions sincerely.

Because the novel restricts us to the two main characters, we can’t know what’s happening outside their ken. Something similar happens to the attached viewpoints in Leave Her to Heaven, in which Dick and Ruth only gradually learn how his wife Ellen plotted to make her death seem to be murder. In adapting the novel to film, screenwriter Jo Swerling respected the novel’s systematic attachment to characters to a surprising extent.. First we are mostly with Dick, but at crucial points we’re given blocks of scenes organized around Ellen. Unlike the book, the film version shows us her executing her plan to implicate Dick and Ruth in her death. Here, for instance, Ellen puts arsenic in the sugar bowl that Ruth will use to sweeten Ellen’s coffee.

The film Gone Girl doesn’t give Nick a pervasive narrating voice as the book does, and we aren’t wholly restricted to his range of knowledge. On several occasions we watch the police making discoveries that he’s not aware of. Crucially, we see them find the diary some days before they tell him about it. As so often happens, mainstream film introduces some unrestricted narration, which yields suspense rather than surprise. Amy narrates the eight diary entries which introduce flashbacks, some of which turn out to be false ones. But once she finishes her Cool Girl monologue after the big turning point, we don’t, I think, hear her voice-over again.

Nick’s voice-over enters only twice, with carefully symmetrical effect. The film’s first shot is a close-up of Amy turning toward us as a hand strokes her head. Nick’s voice talks of wanting to split open her skull, unspool her brain, and find the answer to married folks’ perennial questions. “What are you thinking? What are you feeling? What have we done to each other?”

Most broadly the shot has the effect of rendering this beautiful woman mysterious. It also suggests a violent impulse in an uncaring, obtuse male—the sort of scenario that would lead to the murderous-husband plot that hovers over the film’s first hour. The final shot of Gone Girl repeats the close-up, and Nick asks his questions again but adds, “What will we do?” Now we know how devious that brain is, and how much justified anger the man speaking may be feeling toward her. Perhaps, after the movie ends, he will be ready to kill her. The two shots, unanchored in story time, bracket the movie with the central duality that the plot and the narration will enact: a potentially murderous man and an innocent-appearing but lethally dangerous woman.

There’s much more to be said about the film and the novel. I haven’t touched upon Flynn’s subject matter—what we might call Yuppies 2.0, the brain-entitled Net-enabled cool kids—and her theme of marriage as a struggle to play the role your partner cast you in. Issues like these have ingeniously set readers talking about marriage’s putative dark side and how men can feel “picked apart” by dazzling, demanding women. For my money, the presence of this brilliant, beautiful Crazy Lady, another legacy of the 1940s, favors Nick’s side of things. He’s a weasel but not as dangerously nuts as his wife. Your mileage may vary, for reasons I attribute to Hollywood’s perennial urge to cover every bet on the board.

We’d also want to consider the novel’s style, which offers caffeinated versions of Product Placement Realism and Vivid Writing, in both male and female registers. The screen version loses this aspect of the novel, and we get instead Fincher’s calm, polished direction. Too many shots of vehicles pulling up to buildings, I suppose; but if everybody laid out scenes as slickly as Fincher does we wouldn’t complain so much about our movies. I admired in particular the virtuoso sequence accompanying Amy’s Cool Girl monologue. Her eloquent rant runs underneath a crisp replay of her scheme and then supplies a montage of her trip and her change of identity, with glimpses of female types illustrating her diatribe. This passage is a good example of the crackling pace of the movie, which, thanks to smooth hooks and concise exposition, rushes along at just the speed of our comprehension.

Consider as well the economy of a single moment, when Greta and Jeff steal Amy’s money. At one level, the couple serves purely a plot function, one typical of a Development section: new problems, often overcome, serve to delay the climax. (Another plot construction would have had Amy simply lose her money and call Desi right off, shortening the movie by quite a bit.) The confrontation in the motel also serves a thematic function, contrasting Amy’s sheltered life with another social level she both detests and fears, as well as giving us another couple to compare with Amy and Nick. (Interestingly, in the Greta-Jeff pairing, it’s the woman controlling the man.) The moment I have in mind, the instant when Greta slams Amy’s face against the wall and says, “I don’t think you’ve really been hit before,” fulfills even more purposes. The whack (a) shows that Amy’s new identity is easier to see through than she thinks; (b) reminds us that her diary reports of being beaten by Nick are false; and (c) engenders a certain sympathy for her, invoking the classic woman-in-peril situation. This tight packing of implication and emotion into an instant is characteristic of classical studio storytelling. It exemplifies the unfussy efficiency celebrated by Otis Ferguson and Monroe Stahr.

My purpose here has simply been to indicate that we can usefully understand any plot as a composite of possibilities that surface in other plots. In a way, I’m revisiting ideas floated in my Shklovsky/Sondheim entry months ago. Again, this isn’t to put down Gone Girl as formulaic. Instead, it’s to suggest that any narrative we encounter in the mass-market cinema (and probably in other forms of filmmaking) is part of an ecosystem, a realm offering niches for many varieties—including hybrids.

Thanks to Kristin, David Koepp, and Jeff Smith for conversations about Gone Girl.

For comprehensive accounts of mystery and detective fiction, visit Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website. Relevant to today’s entry is my web essay, “Murder Culture,” and my entry comparing Safe Haven and Side Effects. Film Art: An Introduction includes a section on various forms of the thriller in Chapter 9. And don’t get me started on the relation between Gone Girl and one of my favorite domestic thrillers, Double Jeopardy.

The distinctions among story world, plot structure, and narration that I use here are explained in two other items: the chapter, “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” in Poetics of Cinema, available on this site; and the analysis of The Wolf of Wall Street illustrating that argument.

Diane Waldman outlines the role of the helper male in her article “‘At last I can tell it to someone!’ Female Point of View and Subjectivity in the Gothic Romance Film of the 1940s,” Cinema Journal 23, 2 (Winter 1984), 29-40.

For more on four-part plots, go to Kristin’s entry here and the essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture.” I’ve argued in another entry that popular novels can be built upon the four-part structure Kristin outlines, and it’s interesting to compare them with film versions that follow the same template. My examples were The Ghost Writer and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Fincher version). I think that Flynn’s novel is built on a five-part armature roughly comparable to that of the film. As for double-climax plots, I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that In Cold Blood is another instance of this structure.

A more intricate use of diary narration in film is Nolan’s The Prestige, which derives from the even more intricate deployment of it in Christopher Priest’s original novel. We discuss the film in Chapter 7 of Film Art: An Introduction, and there’s a bit about the novel here.

Why so much emphasis on the cat in the film of Gone Girl? I suspect it’s at first a place-holder for the vanished Amy. Nick strokes the kitty as he strokes Amy’s head in the opening and closing shots. Seeing the cat tiptoe near broken glass (“You haven’t got a clue, have you?”) provokes Nick to solve the final clue in the treasure hunt. One shot, after Amy has returned, includes both wife and cat perkily welcoming Nick to breakfast. The cat is oddly matched eventually by the robot dog that Amy orders in Nick’s name. As a result, when Ellen Abbott gives Nick a robot cat, we have matching mechanical pets. Sort of like the human couple at the end.

Gone Girl.

Comic-Con: The end of an era, and other highlights

Kristin here:

Long-time readers of this blog may recall that in 2008 I went to Comic-Con for the first time. I can’t recall exactly what led me to take the plunge. It may have been that by that time it was evident that the con had grown into a major opportunity for Hollywood studios to publicize their upcoming blockbusters to their core audience and I wanted to witness the process in person. Until this year, I hadn’t returned to Comic-Con. I was motivated in part by the fact that this was the last big promotional event for a film in the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise. I had briefly discussed Comic-Con in relation to LOTR in The Frodo Franchise, but I had not witnessed any of the appearances of cast and crew promoting the first trilogy. This was my final chance, the end of an era.

I blogged about my first visit four times. I wrote about the LOTR/Hobbit presence on the Frodo Franchise blog. On this blog I gave an overview of the Comic-Con experience, analyzed why Hollywood poured so many resources into an event nominally about comic books, and posted a conversation between Henry Jenkins and me. Henry, who had helped found the area of fan studies back in the 1990s with such widely cited publications as Textual Poachers, was also a Comic-Con newbie that year, and we shared our reactions. (This year Henry was on a panel, “Creativity Is Magic: Fandom, Transmedia, and Transformative Works,” one of a number of panels on fan culture. I missed it because I was in line for Hall H. More on that below.)

A friend of mine who has a press pass assured me that they were not as hard to obtain as I had feared, so, based on my collaboration on this blog and my position on the staff of TheOneRing.net, I applied. To my delight, I was granted one, so I set out to cover Comic-Con more officially.

Going to Comic-Con alone isn’t nearly as fun, and I was lucky enough this year to meet up there with my friends, Professors Jonathan Kuntz and Maria Elena le las Carreras and their irrepressible daughter Rebecca, who are always terrific company.

Preview night

On the Wednesday evening before Comic-Con begins, there is a preview. This means that people with various special passes can get into the big exhibition hall where most of the booths are set up. These range from dealers in rare comic books to the biggest entertainment companies, like Warner Bros. and Lego. Many of them offer unique items only for sale or give-away at Comic-Con.

Many attendees have realized this, and they buy tickets that include the preview evening. The floor was much more crowded than when I attended the preview night in 2008. There were lots of lines with people trying to get those unique collectibles.

Others were there to look at comics. Yes, there are still plenty of comics at Comic-Con. There are dealers offering rarities, as in the image above. There are comics publishers with their latest offerings.

A particular favorite of ours is Fantagraphics, which specializes in reprinting comics. They’ve launched a set of hard-cover volumes of Walt Kelly’s syndicated Pogo strips. They also, I discovered, are doing a series of Don Rosa comics, also in hardback. In fact, when I was strolling around the booth, I realized that Rosa himself was signing autographs until 8 pm. It was then 7:59, so I grabbed volume 1 and was the last person to get my copy signed. By the way, it includes “Cash Flow,” one of the Uncle Scrooge stories I mentioned in our first blog entry on Inception. Volume 1 hasn’t actually been published, but it’s available for pre-order on Amazon.

The big moment of my evening, entirely by chance.

My first press conference

Once you’re granted a press pass, your name is put on a list made available to the exhibitors and publicists planning events. Companies big and small send you announcements about signings, press  conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

I showed up and got a front-row seat off to the side. The room filled up (right).

The event itself started somewhat late, and two gentlemen who were not Benedict Cumberbatch or John Malkovich appeared and answered some questions. (I would give their names, but the usual signs put on the table in front of guests were not in evidence.) We were approaching 11:25. John Malkovich and another gentleman appeared. Another couple of questions were asked, and someone announced that Benedict Cumberbatch’s plane had gotten in late the night before and besides we had to leave to make room for the next event scheduled in the room. We were not escorted to reserved seats in Hall H, where I hear that Benedict Cumberbatch did appear.

I can only trust that this is not how most press conferences turn out. Perhaps I will be invited to another one and find out.

Bill Plympton in person

Given that I had no option to go to the Hall H DreamWorks Animation presentation, I sought out an alternative among the several items offered during the noon slot. I had had my eye on a panel which had as its guests the well-known animator Bill Plympton, as well as Jim Lujan, the co-director of the feature-length Revengeance, in progress. David and have long been fond of Plympton’s work, especially his laugh-out-loud classic, Your Face (1987), which was nominated for an Oscar. It’s just a series of distortions of a man’s face as he sings an utterly wimpy love ditty (above).

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Apart from clips from Revengeance, Plympton also showed a brand new short, Footprints, a charming tale of a man’s search for a mysterious house invader. It will be shown on August 14 as part of the Hollyshorts Film Festival, which will honor Plympton with the Indie Animation Icon Award. The film was entirely hand-drawn in black and white and then colored digitally.

During the panel there was a contest for a T-shirt. The question was: What is Bill Plympton’s middle name? Despite a plethora of cell phones, laptops, and tablets in the audience, no one could come up with the right answer. A second question was put forth: what was Plympton’s first theatrically released film? “The Tune,” came a cry from the audience. It was Sam Viviano, art director of Mad Magazine; he walked off with the shirt. Plympton then sheepishly confessed that his middle name is Merton.

Plympton’s films have been hard to find online, but this fall they will become available on Source HD: “It’s the entire catalog, everything I’ve ever done.” That includes about 60 shorts. As a result of this online exposure, he says, “I expect that when I come back to San Diego next year they’re going to have to give me one of those huge 2000-seat rooms.” I hope so, and I hope it will be filled–but not so jammed that I could not get a seat.

Plympton offered all attending his panel a free autographed drawing. I went to collect mine at his booth in the exhibition hall and found him drawing (right), as he must constantly be doing. Note the Cheatin’ poster behind him at the left and the usual bustle of Comic-Con in the background. He paused to dash me off a delightful image of his famous Dog character. (An animator who doesn’t use cels has to be really fast at drawing.)

Plympton DVDs are not all that easy to find, though you can get them and other merchandise at his website’s shop. If you don’t know his work, it’s time to start catching up.

A new experience: The Indigo Ballroom

Seeking to accommodate more fans without violating fire regulations, Comic-Con has expanded into nearby buildings. One of the facilities utilized this year was the Hilton San Diego Bayfront, just across from the Convention Center on the Hall H end. That’s where the DreamWorks press conference sort of took place. Its biggest room was the Indigo Ballroom. I’m not sure it had 2000 seats, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

My colleagues at TheOneRing.net have been presenting panels on the Hobbit series for several years now. In fact, my visit to Comic-Con in 2008 was as a participant on one of those panels, speculating much before the fact on the shape that the Hobbit project would take. At that point the cast hadn’t even been chosen. I suggested that Wisconsin’s own Mark Ruffalo would make an excellent Thorin. I still think he would have, but Richard Armitage has gained a large fan following in that role. I’m not sure that at that early stage Martin Freeman was everyone’s favorite candidate for Bilbo, but he soon became so–including mine. The man is a born hobbit.

That 2008 panel took place in a relatively small room in the Convention Center. In more recent years, the TORn panel has been joined by such luminaries from the filmmaking team as Richard Taylor. It has gained such a following that this year it was booked into the Indigo Ballroom.

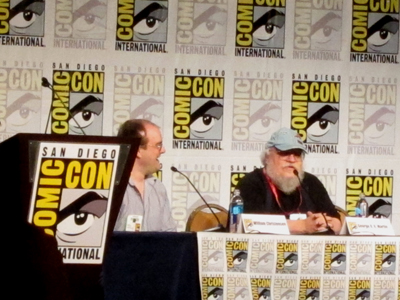

Then we learned that George R. R. Martin was booked into the same room in the time-slot directly before TORn. (I’m sure you all know who he is, but for the few who don’t, I’ll just say, he’s the author of the “A Song of Fire and Ice” series, of which Game of Thrones is the first book.) We were all convinced that Martin’s session would be jammed and furthermore that an overlap in fandoms would mean that the audience there for Martin would stay for the TORn panel, excluding those who showed up just before the TORn session. There was much discussion as to how TORn staff not on the panel (like me) could get in and be sure of a seat. How many seats could be reserved? We didn’t know.

I determined to support my colleagues and attend the TORn panel. The question was, how many sessions would I have to sit through to make sure I could get a seat? (Rooms are never cleared between sessions at Comic-Con, since doing so would take too much time and would mean that people in one room for a session would not be able to get in line for the next session in that room. Hence the strategy of sitting through multiple panels in the same room to guarantee a seat at the one you really want to see.)

I arrived early in the afternoon in the middle of a session about some show on Comedy Central. This finally ended and the George R. R. Martin panel began. To my surprise, it was only about two-thirds full. I learned later that Martin often attends Comic-Con. Moreover, this time he wasn’t talking specifically about Game of Thrones. The session was billed as “George R. R. Martin Discusses In the House of the Worm.” The title in question is a new comic-book series that Martin is involved with. (Above, William Christensen, publisher at Avatar Press, interviews Martin.)

I had expected to sit through Martin’s session merely waiting for the TORn one to begin. I had read Game of Thrones, widely assumed to be heavily influenced by The Lord of the Rings. Game of Thrones was entertaining, but by the end I found it repetitious. I figured that the series could only become more so, so I quit there. I haven’t seen the TV episodes. Yet Martin turned out to be quite entertaining. He is a long-time fan, and his reminiscences about fandoms during the 1960s and onward were fascinating. He’s a lively, knowledgeable, and entertaining speaker with a wide experience in both reading and creating fantasy works in those days. His presentation made me wish that I liked that first book better.

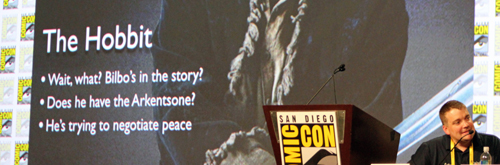

The next session was “An Unofficial Look at the Final Middle-earth Film: The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies.” (Actually in the program the title said “Final Middle-Earth Film,” but I’m sure my colleagues did not make that capitalization error when they proposed the panel.)

The panel consisted of, from the left, Chris “Calisuri” Pirotta, a TORn co-founder; John Tedeschi, long-time staffer; Cliff “Quickbeam” Broadway, frequent contributor to the site; Kellie Rice, staffer and half of the “Happy Hobbits” fan duo; and Larry D. Curtis, another long-time staffer and frequent contributor. Chris and Cliff were among several TORn interviewees when I was researching The Frodo Franchise.

TORn has made annual appearances at Comic-Con, usually speculating in expert fashion on what might be included–or not–in the next film. Staffers comb the previous films, trailers, Peter Jackson’s production diaries, publicity photos, and cast and staff interviews, seeking for clues. While presenting their findings, they point out things in the earlier parts that people might not have noticed or may have forgotten.

The first line in the Powerpoint image above refers to widespread fan annoyance that Bilbo seems to have been pushed to the periphery of his own story in The Desolation of Smaug. This is a topic of frequent comment on the website. The TORn panel was held on Thursday, two days before any of us had a chance to see the first teaser-trailer’s premiere on Saturday in Hall H. (More on that below.) Although there are shots of Bilbo in that trailer, they mainly show him staring offscreen and reacting. I was left hoping that this is not an indication of more sidelining of our protagonist. In Tolkien’s book Bilbo decides to sit out the Battle of Five Armies and gets knocked unconscious early in the fighting; given that he’s our point-of-view figure, the battle is mainly told through other characters describing it afterward. No one expects Peter Jackson to stay true to that action and sacrifice the chance for another epic battle scene, so maybe Bilbo will get to do his share of fighting.

This year’s celebrity guest made an appearance at the end and took a few questions: Jim Rygiel, multi-Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor for The Lord of the Rings (and more recently Godzilla and The Amazing Spider-Man):

Whether the panel members were right in their speculations will not be known until December 17 (in the USA). Right or not, it was an entertaining and informative session.

What were they really there to see?

There are many rooms devoted to Comic-Con events, not to mention the various open-air booths and attractions set up in open spaces near the convention center. Room 25ABC is fairly large, but it’s considerably smaller than the Indigo Ballroom, 23ABC, and of course, Hall H. I was not alone in being puzzled as to why the panel “Fight Club: From Page to Screen and Beyond,” was scheduled in 25ABC at 7 pm on Saturday evening. Sure, the topic was an older film, and the panel was largely devoted to a forthcoming graphic-novel sequel to the story. Still, the participants included David Fincher, making his first Comic-Con appearance. I can only suspect that Fincher was a late addition to the panel’s line-up and it was too late to change the venue.

The result was that anyone determined to hear what Fincher had to say was bound to line up for the panels just before the Fight Club one and sit through them in order to see it. I decided to line up for “Disney’s Gargoyles 20th Anniversary” at 5 pm, having no idea what the Gargoyles are, and “Publishing 360: Building a Bestseller” at 6 pm, having no intention of trying to build a bestseller.

I got into a line that looked fairly short and was defined by lines of tape laid down on the carpets in the broad corridor outside 25ABC. It turned out to be one of those Disneyland-style ribbon-candy set-ups, where the line folds back on itself time after time, and you end up walking in one direction, turning around to walk in the opposite direction, only to realize that there is another group of people doing the same thing ahead of you in the same line. Fortunately most people seem to stick to the rules pretty closely, perhaps being aware of the wrath they would call down upon themselves by attempting to cut ahead of others.

I ended up about ten people back in line when the room was full. I never did learn what the Gargoyles were, but I suspected some people behind me had been hoping to get into that panel and were not there for the Fincher event. Indeed, as it became clear that no seats were going open up, a small number of people departed, leaving me about six people back from the front. It was looking good for me to get into “Publishing 360.”

At this point, from behind me I heard “Pardon me, but are you Kristin Thompson?” or words to that effect. Thus I met Ryan Gallagher, one of the stalwarts of The Criterion Cast, which describes itself as “A podcast network and website for fans of quality theatrical and home video releases.” (It is not officially associated with The Criterion Collection.) I recognized his name because he has sent many a reader to Observations on Film Art. Ryan’s latest podcast is a preview of Comic-Con, and I expect he will add one looking back on his experiences there.

What are the odds, I thought, and still think, that with 125,000+ visitors to Comic-Con, I would end up in line next to someone who recognized me? Turns out Ryan had been in line for the Gargoyles panel, so after a brief conversation, he departed. Eventually I was among the first into the room for the “Publishing 360″ panel, though there were people already there who didn’t leave, and I suspect the audience for Gargoyles doesn’t overlap all that much with the audience of people longing to write a bestseller. The procedure for building a bestseller, by the way, seems to consist primarily of getting the best agents and editors in the world. Aspiring writers, take note. Before the session began, I located an unoccupied electrical outlet and recharged my recorder. (This is a serious business at Comic-Con. The convention center is full of cell phones, tablets, and cameras dangling from outlets.)

The panel as pictured above consists of, from the left: moderator Rick Kleffel, Doubleday executive editor Gerald Howard, Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk, David Fincher, and three artists and/or editors from Dark Horse Comics, which will bring out the Palahniuk-penned ten-part sequel starting in May, 2015.

A lot of the panel was about the graphic-novel sequel, of course. The main bit of new information about the film was that although it didn’t do particularly well at the box-office, Fincher finally got 20th-Century Fox to give him figures on how many DVDs were sold. Sales totaled around 13 million, so Fincher reckons the film must have made a profit in the long run. Probably the quotation from Fincher that will be remembered is: “My daughter had a friend called Max. She told me Fight Club is his favorite movie. I told her never to talk to Max again.” Fincher may not have been to Comic-Con before, but he knows how to please the fans.

Check out the Film website for an audio recording of the panel.

Hall H: Getting in

Hall H tends to draw much of the attention accorded to Comic-Con in the media. It’s the largest venue, with 6500 seats–including a large number reserved for representatives of the studios presenting publicity events there. That’s a big venue, but compared to the roughly 125,000 people attending the con each day, it’s not big enough. Although not everyone at Comic-Con wants to get into Hall H, most days the lines snake down and across the street, along the sidewalks. (A video moving along an entire Hall H line at a walking pace was posted on Youtube last year. It runs for over fourteen minutes, despite the fact that the people toward the front of the line are walking forward past the camera; if they were standing or sitting still, it would have run even longer.) In previous years the only way to guarantee getting into the hall for the first events of a day was to get there the previous evening and stay in line overnight. Short departures were possible if someone held your place, but basically you were there for the duration.

I was lucky enough to benefit from the innovation of a new policy on Hall H admissions. Color-coded wristbands would be handed out as the line formed, pausing at 1 am and resuming at 5am. The first portion of the line got a red band, with other colors for the next portions. The purposes were 1) the management could gauge how many people were lined up; 2) those in line could know whether they would get in or not; and 3) for the first time some people could leave for longer stretches of time than required for a rest-room break, as long as someone from their group with the same color wristband remained.

At least, that was how it was described in the online announcement. Those charged with distributing the bands and keeping order informed us that “a majority” of the group had to remain. To what degree that was enforced, we never learned. Fortunately that worked for Jonathan, Maria Elena, and I, since Rebecca had formed a “Hall H-line” group on Facebook and assembled a bunch of friends to camp out in line together. We adults, with our less flexible bones, departed for dinner and some sleep at our hotel. The next morning when we came to rejoin our group, the people in charge of keeping order asked if we had been to the rest room. Yes, we had. That and other things. Apart from everything else, the parking garage under the convention center has to be cleared after 10 pm, so the Kuntzes had to leave to get their car out. Clearly some clarifications of the guidelines are in order, but based on our experience the new wristband policy has improved the Hall H-line experience considerably.

The announced wristband-distribution schedule also had to be adapted. In the past, the Hall H line has started forming in the late afternoon or early evening, depending on the popularity of the first event scheduled for the following morning. Jonathan presciently went and got in line at 2:30 pm, and he was far from the first. Our party gradually grew as other members arrived, and inevitably groups ahead of us also swelled. Soon the line was very, very long. (A small portion of it is pictured above; the line had taken a U-turn a few hundred feet behind us, off right here.) Somewhere around 6:00 the wristbands started to be handed out, and small groups were escorted across the street to line up in the relatively luxurious area on the grass near the entrance to Hall H. There were white canopies overhead and the inevitable red plastic barriers dividing the area into rows approximately one reclining person wide. Those further back in line were less fortunate, having the sidewalk to call their bed. Our group of young stalwarts settled in for games, sleep, and an endless supply of trail mix and donuts. Rumor has it that anyone who arrived after about 9:30 pm didn’t get in. The last wristbands were handed out at around 2:30am. Presumably the handout did not pause at 1 am as planned, since clearly everyone who was going to get in when the hall opened was already there.

The next morning we received a call from Rebecca saying the group had been moved into the “chutes,” a process which had started at 7 am. These are slightly narrower strips of grass with the same plastic barriers; the chutes are opened one at a time, allowing the people in each to go in before the next chute is opened. More people are moved into the emptied chutes, and the process continues until the hall is full.

Although the handlers had said we would be let in at 9:30 for a 10:00 start, they got the process going at 9 am. By 10 we were all seated and ready for the Warner Bros. extravaganza to begin. There I am, wearing my vintage licensed Fellowship of the Ring T-shirt and the crucial pink wristband:

Expensive flash

Warner Bros. had two hours in Hall H on Saturday morning to promote their films. The full program is not announced in advance. People were assuming that The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies, as the biggest item on tap, would be saved for the end. That turned out to be correct.

The event started with curtains sliding back to reveal a long, panoramic screen on either side of the big central one. This surrounded about the front half of the audience in a U-shaped set of images. Warners installed these screens at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars; naturally no other studios were allowed to use them.

Some short presentations opened the program, beginning with Zack Snyder coming onstage. He introduced Ben Afleck, Henry Cavill, and Gal Gadot, none of whom spoke. We saw a very brief clip from Batman vs. Superman. The two lead characters’ first meeting had them glaring at each other with glowing eyes, white and red respectively. (Naïve me, wondering why if they’re both good guys, they don’t just join forces to fight evil.) My main impression was that Batman looks like he’s wearing a small tank turret on his head. The fans were apparently pleased with what they saw.

The moderator then introduced Channing Tatum, who stood below the screen as a montage of footage from Jupiter Ascending was shown. This made no impression on me, and I have no memory of it, except that the big action scene looked pretty conventional.

The event really got going with a much longer promotion with George Miller talking about Mad Max: Fury Road. This used the side panels to good effects (above). David and I have been fans of Miller and the Mad Max series ever since Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior in the USA) appeared. It was a treat to hear him talk about the new film, though what he said is pretty much what he has said in other interviews: there’s little CGI in the film, he storyboarded the whole thing rather than writing a script, it’s an attempt to do a continuous chase sequence for an entire film, etc.

Miller presented a montage of quick scenes from the film. It looked good but familiar. There’s Max, chained up on the front of one of the villains’ vehicles, as were some of the captives in The Road Warrior. A lot of the minor characters recall those of the same film. The digital image looked brighter and sharper than the previous films–not necessarily a good thing, since the three first films were muted, conveying a sense that everything and everyone was coated with dust. Unseasonal rains in Australia forced the new film’s shoot to move to Namibia, which looks like it stands in for the Outback pretty well. We must trust that, just as the first three films were significantly different from each other, this fourth film will have a unique flavor not apparent in the footage shown.

This was, by the way, the second preview I’ve seen recently of a film that imitates the awesome (in the old and literal meaning of that word) dust-storm in this well-known National Geographic clip online. And why not, though CGI can never equal the real thing in this case.

Hall H for Hobbit

Quasi-Spoilers ahead:

The second half of Warners’ slot was given over to The Battle of Five Armies. An opening blast of music accompanied the appearance from left to right of a panorama of images from all three Hobbit films:

Even this fairly comprehensive view of the screens leaves out two or three images on the far right. The most revelatory of these shows Galadriel, Elrond, and Saruman at Dol Guldur, rescuing Gandalf. The panorama stayed up throughout the presentation. (A rather juddery pan around the whole things can be seen on Youtube.)

Steven Colbert, widely known as a devoted and highly knowledgeable Tolkien fan, MCed the panel, dressed in his costume from the third film, in which he has a nonspeaking bit part. He expressed his love for Tolkien and the films and showed the brief scene in which he appears. Then he introduced the impressive eleven-person panel Warner Bros. had managed to assemble:

From the left, Colbert, Peter Jackson, Philippa Boyens, Benedict Cumberbatch, Cate Blanchett, Orlando Bloom, Evangeline Lilly, Luke Evans, Lee Pace, Graham McTavish, Elijah Wood, and Andy Serkis

Of course, most of us couldn’t see them this clearly with the naked eye. Seated about a third of the way back in the auditorium, my view was as shown in the image at the top of this entry. Peter (that’s he in the lower left corner) looked mighty small in reality, but in Hall H three large screens magnify the proceedings for the crowd. (Similar video screens are used in the other very large auditoriums, notably the Indigo Ballroom.)

One highlight was the first screening of the long-awaited teaser trailer. This was released online two days later; the best place to see a large, sharp image that starts streaming almost instantly is on Peter’s Facebook page. I have to say that it looks pretty promising, apart from the continued presence of the distracting and tedious Azog and Bolg.

I won’t give a complete run-down on this panel, since a good video of it has been posted on Youtube (with the two screenings of the teaser trailer cut out). Much of it consists of typical star chit-chat. The most interesting thing said came from Peter. There has been considerable speculation among fans as to whether the filmmakers will stick to the book and let some characters die during the battle. Peter stated that the grim parts of the book are being retained and implied that several characters will indeed die. (This should mean that here will be much lamentation among the “hot Dwarves” aficionados.)