Archive for the 'Directors: Hou Hsiao-hsien' Category

Early Hou Hsiao-hsien: Film culture finally comes through (a repost)

The Green, Green Grass of Home (1982).

David’s health situation has made it difficult for our household to maintain this blog. We don’t want it to fade away, though, so we’ve decided to select previous entries from our backlist to republish. These are items that chime with current developments or that we think might languish undiscovered among our 1094 entries over now 17 years (!). We hope that we will introduce new readers to our efforts and remind loyal readers of entries they may have once enjoyed.

DB here:

In March, the Criterion Channel will be featuring a selection of early films by the great Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. These have been very hard to see in the West; I went to Brussels and Taipei to watch prints back in the 1990s. For those who admire his later works, they are absolutely necessary, and for the casual viewer they’re great fun. Two of them, Cute Girl and Green, Green Grass of Home are lilting musicals, while The Boys from Fengkuei is a wandering-youth story with affinities to coming-of-age films like Fellini’s I Vitelloni. (Too bad the series couldn’t include his second feature, Cheerful Wind.) My effort tries to show how a basic technical choice that Hou made created powerful effects on his visual style.

Because the frames are so dense with information, you may want to enlarge them as you go. For a fuller examination of Hou’s work across his career, there’s a chapter in Figures Traced in Light and a video here. The original blog, posted on June 6, 2016, was an attempt to fill in areas I didn’t have room to include in the book. If you’re unfamiliar with Hou’s major works, you should probably watch the video before reading the recycled entry.

For today, let’s call “film culture” that loose agglomeration of institutions around non-mainstream cinema. Film culture includes art house screening venues, festivals, magazines like Film Comment, Cinema Scope, and Cineaste, distribution companies (Janus/Criterion, Milestone, Kino Lorber et al.), critical websites, and not least the new channels of distribution and exhibition like Fandor, Mubi, and the impending FilmStruck.

Although the system is decentralized, there’s usually a fairly predictable flow of films through it. A film is shown at festivals, written up by critics, and picked up by distributors. Then it gains some exposure in theatres or more festivals, and it eventually becomes available on DVD, cable, and streaming services. And now we expect the process to move fairly quickly. Mustang played Cannes and many festivals through summer of 2015; it moved to theatres in the US and elsewhere in the fall. Only a year after its premiere, you can buy it on disc.

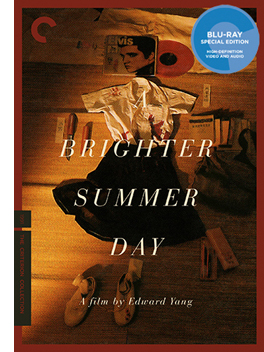

We’ve also been aided by the emergence of multi-standard video players and the willingness of some disc-publishing companies to release versions with subtitles in several languages. All too often, though, “film culture” displays gaps and delays. It took six years for Asgar Farhadi’s wonderful About Elly (2009) to make its way to minimal visibility in the US. Fans of Godard have been prepared to wait years to see his many films that didn’t get even video release in English-speaking territories. (Soigne ta droite! played Toronto in 1987, never got a theatrical release in America, and showed up on US DVD in 2002; the Blu-ray came out eleven years after that.) Two of the most egregious examples of this time lag involve the works of the outstanding Taiwanese filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s: Hou Hsiao-hsien and Edward Yang.

Most of Hou’s films had no proper US release. When they were available for booking, as from Wendy Lidell’s heroic International Film Circuit, they circulated for one-off screenings. Some of his major films, such as City of Sadness (1989), still remain difficult to see. Edward Yang’s work was similarly obscure. When we ran a retrospective at our UW Cinematheque in 1998, we had to borrow prints from his family.

Most of Hou’s films had no proper US release. When they were available for booking, as from Wendy Lidell’s heroic International Film Circuit, they circulated for one-off screenings. Some of his major films, such as City of Sadness (1989), still remain difficult to see. Edward Yang’s work was similarly obscure. When we ran a retrospective at our UW Cinematheque in 1998, we had to borrow prints from his family.

Both of these extraordinary filmmakers had to wait many years for the exposure that is standard for European arthouse releases. After six features in seventeen years, Yang found a Western audience with Yi Yi (2000). Hou took even longer; twenty-seven years after his first feature, he gained some recognition with The Flight of the Red Balloon (2007) and last year, The Assassin. Meanwhile, many of these directors’ early films remain largely unknown, prey to ancient distribution contracts and the belief that the films would cost too much to revive and market.

Today’s entry and the next one celebrate the welcome news that important works by these two filmmakers are at last available on the disc format. Today I’ll concentrate on the three early Hou films from the Cinematek of Belgium: Cute Girl (1980), The Green, Green Grass of Home (1982), and The Boys from Fengkei (1983). Next time, I’ll consider Criterion’s release of Edward Yang’s masterpiece A Brighter Summer Day (1992).

Hou, early and late

Hou’s films are no stranger to this site. Among the first things I posted, back in 2005, was one of a batch of supplemental essays to my book, Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging (2005). That book devoted a chapter to Hou’s staging principles, with background on what I took to be the evolution of his technique. It was, I think, the first sustained view of Hou’s style, and it included discussion of his earliest films. These were scarcely known in the West and not considered in relation to his more famous work.

The online essay expanded my treatment of those titles. Because that essay is more or less buried elsewhere on the site, and it’s somewhat clunkily laid out by today’s standards, I’m reprinting it, with revisions, here, along with some bits from Figures. But first some background on these early works.

Hou began in the commercial, mainstream Taiwanese-language industry. Most local films had a strong genre identity: martial-arts movies, romantic comedies, or melodramas of family crises. Hou’s first directorial effort, Cute Girl, centered on a romance between two city dwellers who re-meet when the man is called to a surveying task in the countryside. Cheerful Wind (1981) reunites the two stars, Kenny Bee and Feng Fei-fe, in a more serious story of how he, a blind man, wins her love. In the pastorale The Green, Green Grass of Home, Kenny plays a schoolteacher brought to a village, where he meets another teacher and a romance blossoms. This film, however, expands to include dramas, big and small, involving several families; it also incorporates an ecological theme by encourage safe fishing policies.

In making these early films Hou discovered techniques that not only suited the stories he had to tell but also suggested more unusual possibilities of staging. He pushed those techniques further in his later films, with powerful results. The charming early films show him developing, in almost casual ways, techniques of staging and shooting that will become his artistic hallmarks. One basis of his approach, I argue, is his adoption of the telephoto lens.

How long is your lens?

Around the world, from the late 1930s through the 1960s, many films relied on wide-angle lenses—those short focal-length lenses that allowed filmmakers to stage action in vivid depth. One figure or object might be quite close to the camera, while another could be placed much further in the recesses of the shot. The wide-angle lens allowed filmmakers to keep several planes in more or less sharp focus throughout, and this led to compact, sharply diagonal compositions, as in Welles’ Chimes at Midnight (1966).

Although Citizen Kane (1941) probably drew the most attention to this technique, it was occasionally used in several 1920s and 1930s films made throughout the world. The great French critic André Bazin was the most eloquent analyst of the wide-angle aesthetic, and his discussion of Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), The Little Foxes (1941), and The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) has strongly shaped our understanding of this technique.

The 1960s saw the development of an alternative approach, what we might call the telephoto aesthetic. Improvements in long focal-length lenses, encouraged by the growing use of location shooting, led to a very different sort of imagery. Instead of exaggerating the distances between foreground and background, long lenses tend to reduce them, making figures quite far apart seem close in size.

In shooting a baseball game for television, the telephoto lens positioned behind the catcher presents catcher, batter, and pitcher as oddly close to one another. Planes seem to be stacked or pushed together in a way that seems to make the space “flatter,” the objects and figures more like cardboard cutouts. The style was popularized by films like A Man and a Woman (1966).

The telephoto look quickly spread, employed by directors as diverse as Sam Peckinpah and Robert Altman, whose 1970s films also use the long lens, controlled by zooming, to squeeze a crowd of characters (M*A*S*H, 1972; Nashville, 1975) into the fresco of the anamorphic frame.

Hou Hsiao‑hsien came to filmmaking via the romance films so common in Taiwan in the 1970s, and this genre employed the long lens extensively. Working with low budgets, most filmmakers relied on location shooting. The telephoto allowed the camera to be set far off and to cover characters in conversation for fairly lengthy shots (as in Diary of Didi, 1978, below). In this respect, the directors were not so far from their Hollywood contemporaries; Love Story (1970) employs these techniques on a bigger budget.

Indeed, Love Story (a big hit in Taiwan) may have pushed local filmmakers toward using this technique in their own romantic melodramas; sometime the influence seems quite direct (Love Story and Love Love Love, 1974)

With these norms in place, Hou’s inclination toward location shooting and the use of nonactors, along with his attention to the concrete details of everyday life, allowed him to see the power of a technique that put character and context, action and milieu, on the same plane. His crowded compositions are organized with great finesse in order to highlight, successively, small aspects of behavior or setting, and these enrich the unfolding story, as Figures tries to show in his masterpieces of the 1980s and 1990s. Using a long lens (usually 75mm–150mm) he began to exploit some “just-noticeable differences” that the lens creates as byproducts.

Hou saw unusual pictorial and dramatic possibilities of the telephoto lens, and they became central to his distinctive way of handling scenes. A current norm of production practice yielded artistic prospects which he could explore in nuanced ways. Figures provides the detailed argument, but let me highlight three points here.

Exploiting the flaws

Flowers of Shanghai (1998).

One byproduct of the long lens is a shallow focus, as we can see in the examples above. Because the lens has little depth of field, one step forward or backward can carry a character out of focus. Hou stages in depth–and at a distance–but allows the layers to slip out of focus gradually.

Savoring the effects of gently graded focus is a common feature of Hou’s later work. The masher at the train station in Dust in the Wind (1987) moves eerily in and out of focus in the distance. In Daughter of the Nile (1988), there’s an astonishing shot showing gangsters approaching a victim’s SUV outside a nightclub: at first they’re only barely discernible blobs (seen through the vehicle’s narrow windows) but then they gradually come into ominously sharp focus in the foreground, preparing to attack one of the boys inside. The slight changes of focus train us to watch tiny compositional elements for what they may contribute to the drama. More recent examples abound in Flowers of Shanghai (1998), above, where it’s the foreground planes that dissolve.

Hou’s three first films don’t use the option quite so daringly; here the degrees of focus concentrate on the principal players but still allow us to register the teeming life around them (Cute Girl; Green, Green Grass).

Hou can put sharply different dramatic situations on different layers. In Green, Green Grass, the departure of the little girl, saying farewell to her host family, plays out slightly closer to the camera than the departure of the eccentric teacher.

This principle operates as well in the creatively distracting street and train-platform scenes of Café Lumière (2004).

Secondly, the long lens yields a flatter-looking space. It has depth, but the cues for depth that it employs are things like focus, placement in the picture format (higher tends to be further away), and what psychologists call “familiar size”—our knowledge that, say, children are smaller than adults, even if the image makes them both of equal size. One favorite Hou image schema is the characters stretched in rows perpendicular to the camera, and the telephoto lens, by compressing space, creates this “clothesline” look more vividly. We can find the clothesline staging schema in the early Hou films (Cute Girl, Cheerful Wind).

Another favorite schema is the “stacking” of several faces lined up along a diagonal (Cute Girl). This can be seen as a refinement of a schema that was in wider use, as an example from Love Story indicates.

But Hou uses this sort of image more subtly. The telephoto lens lets him stack faces in ways that encourage us to catch a cascade of slight differences (Millennium Mambo (2000)). In many scenes of Flowers of Shanghai (1998) this principle is carried to a degree of exquisite refinement without parallel in any other cinema I know. In one shot, the faces are stacked in the distance, behind a lantern, and a slightly shifting camera reveals slivers of them.

In general, because Hou is committed to a great density of information in the shot, the compression yielded by the long lens tends to equalize everything we see. Minor characters, or just passing strangers, become slightly more prominent, while details of environment can get pushed forward as well. The zoo scenes of Cute Girl enjoy showing us our characters in relation to the creatures around them.

In the shot surmounting today’s entry, the tile rooftops of The Green, Green Grass of Home, secured by bricks and pails and tires and baskets, become just as important as the figures below them.

In Green, Green Grass, Hou develops the equalized-environment option in one particular scene. A long-lens distant view catches the teacher coming to the father’s house along a corridor of rooftops.

When the teacher confronts the father, instead of tight framings on each man, Hou cuts to another angle that activates yet another range of environmental elements—principally the train passing in the background, prefiguring the trip that the man’s son and daughter will take in an effort to find their mother.

Because the long lens has a very narrow angle of view (the opposite of a “wide-angle” lens), it affects the image in a third major way. If you use a long lens in a space containing several moving figures, people passing in the foreground will block the main figures: they pass between the camera and the lens. Hou elevates this blocking-and-revealing tendency to a level of high art.

In Figures Traced in Light, I argue that many great directors, from the silent era forward, have staged action in the shot so as to block and reveal key pieces of information, calling items to our attention at just the right moment with unobtrusive changes of figure position. The possibility of blocking and revealing arises from the “optical pyramid” created by any camera lens. (Lots more on that pyramid in Figures and in this video lecture.)

Hou showed himself capable of using the blocking-and-revealing tactic in traditional ways. Take this simple encounter in Green, Green Grass, when the new teacher Da-nian meets Su-yun, the young teacher with whom he’ll fall in love. The scene begins on him, then cuts to a reverse angle as he’s introduced to the principal.

The others are turned toward the principal in the background; the whole composition pushes our eye toward him. Then the teacher steps left to judiciously block the principal. The woman on the far left turns her head and we’re nudged to look at her. Da-nian swivels slightly too.

Then the key introduction: Da-nian shifts aside a little, the teacher continues to block the principal, and the central woman turns toward us.

The climax (quiet, nifty) of this shot comes when Su-yun rises to meet Da-nian. She commands the center of the frame, frontal and radiant. Like any good classical director, Hou then gives us a reaction shot mirroring the first shot of this “simple” sequence: Da-nian is more than happy to meet her.

Imagine how a contemporary Hollywood director would handle this–lots of cuts, everybody in singles and close-ups, transfixing track-in to Su-yun, maybe a boingo music track–and count yourself lucky to have encountered, for once, an unfussy craftsman.

Hide and seek

The Green, Green Grass introduction scene involves a wide-angle lens, but Hou’s skill with slight character movement shows up in long-lens images too. In fact, I suspect that using the telephoto lens on location made him sensitive to the resources of masking and unmasking bits of the shot.

The loveliest example I know in the early films is the Cute Girl shot I analyze in Figures, when Fei‑Fei confronts the surveyors and the man in the red shirt serves as a pivot for our attention; the staging shifts our eye back and forth across the frame, according to small changes of character glance.

A less drastic example occurs when the surveying team starts quarrelling with the locals around a walled gate: The team’s blocking of the gate gives way to movement into depth and a struggle there between them and the townsfolk.

In all, it seems to me that these three resources of the long lens—the shallow focus, the compressed space, and the narrow angle of view—supplied artistic premises for Hou’s shooting and staging in the later films. This is not to ignore his use of the wide-angle lens on occasion, particularly interiors, as in the schoolteachers’ introduction scene. Once the lessons of the long lens had been absorbed, Hou could apply the staging principles that he’d developed to other kinds of shots and story situations. Sometimes he kept his style smooth and limpid, but at other times he offered the viewer some unusual challenges.

Peekaboo pictures

The Boys from Fengkuei (1983).

Presumably Hou could have kept making good-natured, crowd-pleasing movies for many years, but changes in his professional milieu gave him new opportunities. In the early 1980s Taiwan film attendance declined sharply, and Hong Kong films began to command more attention than the local product. The rash of independent companies had concentrated on speculation, not long-term investment, so only the government’s Central Motion Picture Company could initiate recovery. Ambitious government officials launched a “newcomer” program that offered support for cheap films by fresh talents. Even if the new films could not win back the local audience, they might gain renown at foreign film festivals. At the same period, a local film culture began to emerge, relying upon critics who were sympathetic to the creation of a New Taiwanese Cinema.

Hou was no newcomer, but working within the New Cinema framework he could reconceive his practice. The key question for all directors, he recalls, was: What is it to be Taiwanese? His New Cinema films would focus on political and cultural identity, and they did it through an approach to cinematic storytelling that in many respects ran against the conventions of his earlier films. His first New Cinema feature, The Boys from Fengkuei (1983; included in the Cinematek set) reminds us of how “young cinemas” have often represented a return to Neorealism.

Instead of introducing us to clear-cut protagonists and a dramatic situation, the film immerses us in a milieu, that of the small town of Fengkuei. The first fifteen minutes are episodic, casually showing a gang of teenage boys playing pool, lounging about, playing pranks, and above all getting in fights. Initially, the one who’ll become the main figure is minimally characterized; the emphasis, as the title indicates, is really on the group. The boys drift to the big city, where they try to get by and meet others their age. Throughout, local color and everyday routines drive the action more than character goals and traditional drama do.

This somewhat diffuse approach to narrative, in various countries, has proven well-suited for filmmakers who want to explore psychological development and social-cultural commentary. So it accords with the impulse toward understanding national identities that animated New Taiwanese Cinema. In addition, I think that this looser conception of storytelling allowed Hou to refine some of the stylistic options he had already explored. Now the extended, fixed telephoto shot with varying planes of focus appears as a more indeterminate pictorial field, as in our rather oblique introduction to the boys–partial framed figures drifting in and out of the frame–and their poolroom hangout. Emphasizing incomplete views and vague figures outside the door, Hou gives us a more precise array of balls on the table than he does of his characters in space.

Likewise, even though Hou has surrendered his very wide anamorphic frame, he finds ways to balance human action and tangible surroundings in the ways he did with city landscapes and village rooftops in the earlier films. The bullying of a motorcyclist and a pursuit by a rival gang aren’t rendered with the aggressive cuts and angles we’d expect in violent scenes in the Hong Kong action pictures then ruling Taiwanese screens. It’s as if Hou, along with his colleagues, is rejecting that other Chinese-language tradition.

Which is to say that when conflict comes, Hou turns to “dedramatization,” that tendency (again related to Italian Neorealism and its successors) of tamping down peaks of action. Now his characteristic long lens creates detached shots, sometimes with planimetric flatness, sometimes with tunnel vision. These images play out chases and fights in a way that minimizes their physical impact but reminds us of the design and details of the characters’ world.

Hou’s insistence on the fixed, distant telephoto take is now put in the service of obscured vision. The people who passed through the frame in the earlier films, blocking and revealing the action judiciously, may become more salient than the action itself–which is itself often offscreen, or swathed in shadow, or shielded by aspects of setting. The early films’ fixed long take enabled us to see story action fully, but, now, in its refusal to cut away, the camera can suppress story information.

Early in the film, a street fight passes in and out of a far-off intersection among stalls. The dust-up stirs only slight interest from passersby, before bursting back into the alleyway and coming to the camera.

The masking of the fight by the setting can be seen as an extension of the way the walls in the Cute Girl surveying quarrel intermittently cut off our vision, but here it’s far more drastic and sustained.

I’ve drawn my examples from the early stretches of The Boys from Fengkuei, so as not to preempt your own discoveries as the plot carries the gang to the big city. In these scenes Hou in effect teaches us how to watch his movie. But I think I’ve said enough to suggest how Hou’s fresh conception of narrative, born of a renewed interest in local culture (already present in another register in the first three films), allowed him to carry his stylistic explorations to new levels.

Hou saw certain pictorial possibilities in the long lens, and after developing them to a certain point in popular musicals, he recast them when he took up another kind of storytelling. He realized that leisurely, contemplative narratives permitted him to refine these visual possibilities, and they could become powerful, nuanced stylistic devices. And he didn’t stop, as the films following his New Cinema works vividly show. His visual imagination seems unlimited.

A more general lesson follows from this. Norms of form and style are resources for artists. Some artists follow the schemas that they inherit, while others probe them for fresh possibilities. A few can even make a handful of schemas the basis of a rich, comprehensive style. Ozu did this with the techniques of classical Hollywood editing; Mizoguchi did it with depth staging in the long shot. Like these other Asian masters, Hou reveals how much nuance a few techniques can yield, even when deployed in crowd-pleasing, mass-market movies. And now, thanks to the vagaries of film culture, more viewers can come to appreciate his achievement.

The frames from Diary of Didi and Love, Love, Love are, alas, cropped video versions, but that condition doesn’t keep us from recognizing the telephoto lensing in the originals.

The Cinematek collection also includes sensitive English-language introductions to the films by Tom Paulus and enlightening audiovideo essays by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin.

The indispensable English-language sources on Hou are James Udden’s in-depth career survey, Richard Suchenski’s monumental anthology, Emilie Yeh and Darryl Davis’ study of New Taiwanese Cinema, and two monographs on City of Sadness, one by Bérénice Reynaud, the other by Abe Markus Nornes and Emilie Yeh.

The fullest account I’ve offered of Hou’s style are in Figures Traced in Light and in a video lecture, “Hou Hsiao-hsien: Constraints, traditions, and trends.” See also the several blog entries touching on his work. A broader account of the historical tradition to which he belongs can be found in both Figures and On the History of Film Style, as well as in entries under Tableau staging and in the video lecture mentioned already.

The Boys from Fengkuei.

Can the science of mirror neurons explain the power of camera movement? A guest post by Malcolm Turvey

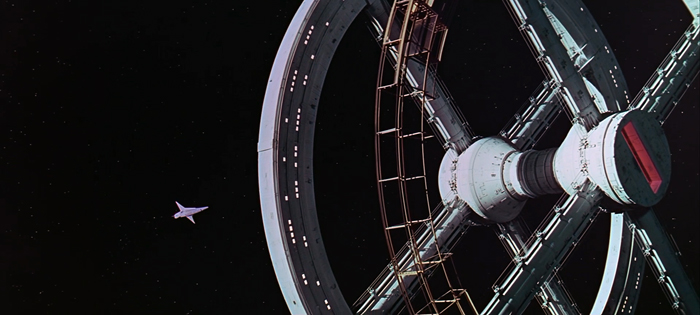

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

DB here:

Over the years we’ve brought you several guest posts from friends whose research we admire. The list includes Matthew Bernstein, Kelley Conway, Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, Eric Dienstfrey, Rory Kelly, Tim Smith, Amanda McQueen, Jim Udden, David Vanden Bossche, and our regular collaborator Jeff Smith (most recently, on Once Upon a Time in Hollywood…).

Today our guest is Malcolm Turvey, Sol Gittleman Professor in Film and Media Studies at Tufts University. Malcolm has long been a voice calling for rigorous humanistic study of film. His books include Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition (2008) and The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s (2011). Just this year he published Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism. (More on this in a future blog entry.) Among his many specialties, Malcolm applies the philosophical tools of conceptual analysis to problems of film criticism and theory.

My previous entry discussed some ways psychological research has helped me understand how films work, and I touched on the recent efforts to invoke mirror neurons to explain some effects that movies have on us. Today Malcolm takes a deeper plunge into this line of thinking, and the result is an exciting instance of how careful intellectual debate can be carried out in film studies. It’s also a cautionary tale about relying on scientific research to explain the appeal of artworks. A more extensive version of this piece is slated for publication in Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind.

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), Alex Sebastian (Claude Rains) is one of a group of Nazis who have relocated to Brazil after WWII. He has unwittingly married Alicia Hubermann (Ingrid Bergman), an undercover American agent seeking his circle. When Alicia learns that their scheme somehow involves the wine bottles locked in her husband’s cellar, she decides to procure the key so that she and her handler (and lover), Devlin (Cary Grant), can investigate.

Her opportunity comes in a characteristically suspenseful scene. Alicia nervously contemplates her husband’s keychain lying on a bureau as he finishes taking a shower nearby. She bravely steals the key and barely escapes discovery as Alex emerges from the bathroom. But what is the source of the scene’s suspense?

In a provocative new book titled The Empathic Screen, Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra claim the suspense should be attributed primarily to a brief, “human-like” camera movement toward the keys that occurs as Alicia looks at them. Moreover, they draw on neuroscience, specifically the science of mirror neurons, to make their case.

Here is the scene.

Are Gallese and Guerra right about the role played by the camera movement? For reasons I’ll give shortly, I doubt they are. More importantly, I question whether the neuroscientific evidence they lean on supports their case. This may seem like nit-picking, but I think their appeal to neuroscience contains valuable lessons about how students of film should–and shouldn’t–engage with scientific research.

Science and film studies

Readers of this blog are likely familiar with the idea that science has an important role to play in film studies. Since 1985, David Bordwell has drawn on contemporary cognitive psychology to answer questions about perceiving and understanding narrative films, thereby launching a new paradigm in film theory that has come to be known as cognitivism. In his previous entry, David offers an overview of his current thinking about cognition and movies.

Cognitivism has generated much heat in academic film studies. But at its heart is what should be an uncontroversial principle: that those who wish to understand the perceptual, cognitive, and affective capacities with which we engage with art should turn to the work of those who know something about these capacities, namely, the psychologists and other scientists who study them empirically and propose theories about them in light of their findings.

This is because our pre-scientific, “folk” understanding of our psychological capacities is usually non-existent or flawed. It is, for instance, hard to explain why we see still frames as moving images when they are projected above a certain speed merely by reflecting on our “phenomenological” experience of watching movies.

Perceptual psychologists, however, have studied this phenomenon empirically and have proposed explanations for it, such as critical flicker fusion frequency and the phi phenomenon (although like all scientific explanations, these are open to revision and even falsification in the light of new evidence and theorizing). The same is true of other features of our experience of films, and cognitive film scholars have built on David’s work by drawing on contemporary scientific knowledge of emotion, music, moral psychology and much else.

This does not mean that film studies is or should be a science. As David and Kristin’s blog entries repeatedly demonstrate, many of the things we want to know about cinema and the other arts can be discovered through non-scientific, humanistic methods such as analyzing films and researching the context in which they were made. In other words, our methods should be tailored to the questions we ask. Cognitivism argues that some important questions about the cinema can be answered by science, not that all or even most can.

The deceptive authority of Science

That said, I worry that engaging with science in a responsible manner is much more difficult than some of my cognitivist colleagues acknowledge. That difficulty is due, in part, to the “authority” of science.

Because of this authority, many non-scientists might assume that science is more settled than it often is, especially in a human science such as psychology. Those of us who aren’t scientists could be tempted to think that a scientific argument must be true because, well, there are scientific data to support it.

But as the recent “repligate” controversy in psychology and elsewhere shows, just because a scientist can present evidence for their views does not make them true. Data can be unreliable and the conclusions drawn from themunwarranted, as we are witnessing on a daily basis during the coronavirus pandemic.

Although there are occasional scientific revolutions, if science makes progress, something that some ph0ilosophers have questioned, it usually does so incrementally through trial and error, and there is much more failure than success. Those of us who don’t participate in this dialectical process might be apt to forget the provisional, tenuous status of much scientific research and accord it more certainty than it warrants.

Mirror neurons: The controversy

This has happened, I believe, with mirror neurons, a new scientific paradigm that has emerged over the past few decades and that some film scholars have started to draw on to explain some of our responses to films, such as empathizing with characters.

Mirror neurons are neurons that fire both when a subject executes a movement and when the subject sees the same movement executed by another. They were first discovered in the early 1990s in the motor cortex of pigtail macaque monkeys by a group of neuroscientists in Parma, Italy, and they have been invoked to explain a wide array of human behaviors such as language, imitation, empathy, art appreciation, and autism.

This is because mirror neurons appear to provide an explanation for how macaques and human beings understand the actions of their conspecifics. Researchers speculate that, if the same neurons fire when a subject reaches for an object, say food, and when the subject observes another agent reaching for food, the subject must be simulating the observed reaching-for-food action in its brain without actually executing it.

By simulating the observed reaching-for-food movement in its neurons, the subject knows the meaning of the movement–reaching for food–because it has performed the movement itself in the past, and attributes that meaning to the action being executed by the agent it observes, thereby comprehending it. As Marco Iacoboni puts it in a popular treatment of the subject:

To see . . . athletes perform is to perform ourselves. Some of the same neurons that fire when we watch a player catch a ball also fire when we catch a ball ourselves. It is as if by watching, we are also playing the game. We understand the players’ actions because we have a template in our brains for that action, a template based on our own movements.

Yet within neuroscience, mirror-neuron explanations of human behavior are controversial and contested, and no less an authority than Steven Pinker has referred to them as “an extraordinary bubble of hype.” Meanwhile, cognitive scientist Gregory Hickock has written an exhaustive book on the subject with a title that says it all: The Myth of Mirror Neurons.

Film scholars who appeal to the mirror neuron paradigm have not engaged with criticisms of it. Hence, their neural explanations of cinema appear to be supported by a scientific consensus that is in fact lacking, and they may not be drawing on the best current science.

For example, the philosopher of film Dan Shaw maintains that “The discovery of the existence and emotive function of mirror neurons confirms that we simulate other people’s emotions in a variety of ways, even in cinematic contexts,” and he views mirror neurons as the neurophysiological foundation for cinematic empathy. Notice how Shaw makes a strong claim here by using the word “confirms.”

Yet, although Shaw writes that “it is a cliché that monkeys are good imitators,” Pinker suggests that macaques do not imitate and they have “no discernible trace of empathy.” This is despite their possession of mirror neurons. Thus, the mere presence of mirror neurons or a mirror system in a creature cannot be evidence, in and of itself, for the creature’s capacity for empathy. While it might provide one of the neural foundations for empathy or contribute to its realization in some way, much more is needed than mirror neurons or a mirror system for a creature to empathize. Their presence certainly doesn’t “confirm” that we empathize with characters in film.

It is, however, a different, equally pernicious consequence of the authority of science that I wish to highlight here using mirror neurons. The apparent authority of a scientific paradigm can lead scholars to cherry-pick and mischaracterize our artistic practices in order to fit the science. This brings us back to Gallese, one of the co-discoverers of mirror neurons, and Guerra, and their claims about camera movement.

Camera movement and mirror neurons

Gallese and Guerra argue that our mirror neurons not only simulate the emotions of film characters but also the anthropomorphic movements of the camera recording them.

We maintain that the functional mechanism of embodied simulation expressed by the activation of the diverse forms of resonance or neural mirroring discovered in the human brain play an important role in our experience as spectators. Our ability to share attitudes, sensations, and emotions with the actors, and also with the mechanical movements of a camera simulating a human presence, stems from embodied bases that can contribute to clarifying the corporeal representation of the filmic experience. [My emphasis.]

In support of their contention that the mirror neurons of film viewers simulate human-like camera movements, Gallese and Guerra cite an experiment they participated in. This measured the motor cortex activation of nineteen subjects who were shown short video clips of a person grasping an object. The action was filmed in four different ways: with a still camera, a zoom, a dolly, and a Steadicam.

“The results were positive,” Gallese and Guerra conclude. “Shortening the distance between the participant and the scene by moving the camera closer to the actor or actress resulted in a stronger activation of the motor simulation mechanism expressed by the mirror neurons” relative to the clips shot with a still camera. Moreover, the subjects rated those scenes filmed with a moving camera as more “involving.”

Gallese and Guerra rely on this single experiment to make a bold argument about the role of camera movement in the design of films and its effect on the experience of film viewers. “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” This is because “the sense of participation in the camera action is undoubtedly enhanced by the fact that its behavior is interpreted by both filmmakers and spectators according to evident and automatic anthropomorphological analogies.”

When scenes are recorded with human-like camera movements, they seem to be suggesting, our mirror neurons simulate these camera movements because they are like actions we ourselves have performed. This in turn results in a feeling of “involvement” or “participation” in the scene on the part of the film spectator.

There is much one could question about this experiment and the conclusions Gallese and Guerra draw from it. For example, if it is camera movement that elicits mirror neuron simulation which in turn gives rise to a sense of immersion, viewers should feel involved in the camera movement, not the sceneit films. Indeed, what is depicted in the scene should be irrelevant to the viewer’s feeling of involvement if it is the camera movement that gives rise to this feeling by eliciting mirror neuron simulation.

Making the art fit the science

It is, however, the theory’s cherry-picking and mischaracterization of the artistic practice of cinema that most concern me here. According to this theory, as we have seen, “the involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” The explanatory claim is that anthropomorphic camera movements, in other words those that resemble the human action of walking through space, elicit the mirror neuron simulation that gives rise to the viewer’s immersion in the film.

This is a strong claim, and if it were true it would have profound implications for both the study of film and filmmaking. It would mean that the more anthropomorphic camera movements that films contain, the more involving they would be for viewers. It would also mean that scenes filmed with human-like camera movements would be more involving than those shot with a still camera, and that scenes filmed with non-anthropomorphic camera movements would be less involving than those shot with anthropomorphic ones.

The latter is due to the mirror neuron simulation theory’s argument that we can only simulate movements we ourselves have performed. Hence, camera movements must be like ones we have executed ourselves in order for our mirror neurons to simulate them and produce the requisite sense of immersion.

Before assessing this claim, one question needs to be answered. What, exactly, is meant by involvement, participation and immersion? After all, there are a number of different kinds of possible involvement in a film.

We can be cognitively immersed in a film when we are intensely interested in the outcome of the plot or the revelations of a documentary. We can also be emotionally involved, as when we feel strong emotions toward the people or events depicted in the film. There is also aesthetic involvement when we pay close attention to and evaluate the design properties of a film. Then there’s physical or corporeal involvement, as when we are physically impacted by film techniques, such as the startle effect or bright lights and loud sounds. Doubtless there are other kinds of involvement too.

Gallese and Guerra never explicitly define what they mean by involvement, although on occasion they mention a “sensation of immersion in the spatiotemporal dimension of film.” In an earlier text they claimed that, by using the camera to mimic bodily movement, filmmakers make audiences feel that “we are inside the diegetic world, we experience the movie from a sensory-motor perspective and we behave ‘as if’ we were experiencing a real life situation.”

Personally, I am not sure what they mean by this. I have never felt immersed in the space and time of a film in the sense of somehow thinking or feeling that I am actually inside it. More importantly, it is not clear that the subjects of the experiment on which their theory is based meant spatiotemporal involvement as opposed to cognitive, emotive, aesthetic or other kinds of immersion when they rated how involved they felt in the clips they were shown. Thus, Gallese and Guerra’s experiment may provide no empirical evidence at all for their occasional references to spatiotemporal participation.

Confusingly, however, Gallese and Guerra sometimes seem to mean involvement in another sense of the term I have clarified. Regarding the brief camera movement toward the keychain in the scene from Notorious of Alicia stealing the key, they contend that “The problem that Hitchcock had to solve in this complex sequence was how to bring the spectator to an almost unbearable level of suspense.” They suggest that if Hitchcock had only used “classical editing” to film the scene, “our level of involvement would not be nearly so high.” They conclude: “This is why Hitchcock uses camera movement; it is this movement that creates the overpowering tension.”

Here, Gallese and Guerra seem to be using “involvement” in the emotive sense of feeling strong emotions such as “tension” and “suspense” about the characters and events in the scene, and they make no mention of “spatiotemporal immersion.” Either way, Gallese and Guerra provide no evidence at all that it is this brief camera movement “that creates the overpowering tension” in the scene. While the camera movement is certainly effective in drawing our attention to the keys and conveying Alicia’s anxious focus on them, I conjecture that there is a far more obvious, broadly “cognitive” reason for the scene’s suspense.

This is the possibility that Alicia, with whom we sympathize, will be caught stealing the key by her husband, who is a ruthless Nazi. Gallese and Guerra, however, discount such a narrative-based explanation for the suspense. They argue that “What strikes us most in films like Notorious is Hitchcock’s almost complete indifference to the plot” and that “the state of suspense in which we find ourselves at every viewing of Notorious has nothing whatsoever to do with the story.”

Yet, according to Hitchcock biographer Donald Spoto, Hitchcock himself wrote the outline for Notorious in late 1944, and then spent three weeks closeted with Ben Hecht writing the script, which was further modified in late-night script sessions with David O. Selznick before the project was eventually sold to RKO and filming began in October 1945. While it may be true that Hitchcock tended to see the plots of his films as merely a means to creating the arresting images and eliciting the strong emotions from his audiences that truly interested him, this does not mean he was “indifferent” to plot. He spent considerable time developing his scripts, and he was keen to work with talented screenwriters such as Hecht.

Nor is it plausible that the suspense in Notorious “has nothing whatsoever to do with the story.” Indeed, suspense is usually defined as a state of anxious uncertainty about what will happen in the story. If suspense has nothing to do with the story, it is hard to know what viewers feel suspense about. In the key-stealing scene in Notorious, it is surely the case that we are anxious about the possibility that Alicia will be caught in the act of stealing the key by her husband, an event that might happen in the narrative. If not, what else might the suspense be directed at?

Of course, the suspense in this scene is not solely dependent on the story but also on the scene’s style. But there are other stylistic techniques that play a much bigger role than the camera movement in the creation of suspense in the scene. For example, Alex’s shadow is visible on his partially open door as he towels himself dry and moves around the shower room.

This activity suggests that he has finished his shower and will emerge at any second. It starts to seem more likely that Alicia will be caught stealing the key, thereby intensifying the suspense. Meanwhile, other than delaying the scene’s outcome by a few seconds, it is not clear how the camera movement toward the keychain itself intensifies the scene’s suspense.

What is happening in the narrative and what is conveyed by other stylistic techniques, such as Alex’s shadow on the door and the music on the soundtrack, are the factors that intensify the scene’s tension. It seems highly unlikely that “our level of involvement would not be nearly so high” in the absence of the camera movement, in the sense of feeling tension and suspense about the scene’s outcome. Certainly, Gallese and Guerra provide no evidence to this effect.

Furthermore, as I’ve already mentioned, Gallese and Guerra’s theory at best explains our sense of involvement in the camera movement, not the scene it films. Recall that it is the camera movement itself that our mirror neurons simulate. It is unclear from their theory, therefore, how our putative feeling of immersion in the camera movement, if indeed we do feel immersed in it, can yield suspense about the concrete actions being filmed.

The category of human-like camera movement, if such a category is functionally relevant to cinema, comprises many fine-grained variations with different effects. Camera movements, for example, can elicit curiosity by making us wonder what they will reveal, as well as surprise when they come to rest on something unexpected. They can startle through their rapidity, as when swish pans suddenly disclose something off-screen, or they can uncover information at an agonizingly slow pace. They can reveal characters’ mental states through push-ins that show us that a character is concentrating hard on something, or they can hide information from us by moving away from it. They can also be aesthetically pleasing, as when we marvel at their gracefulness or the intricacy with which their movements are coordinated with those of the characters. None of these sources of the power of camera movement are explained by arguing that mirror neurons fire in response to anthropomorphic camera movements, if indeed they do.

Most broadly, as David points out in his previous entry, there is much that their theory cannot capture or explain about the power of framing. A static camera can evoke tremendous suspense, as David’s example from Hou’s Summer at Grandpa’s illustrates. It is hard to see what a tracking shot would add at such a moment.

The lessons of film history

Of course, just as damaging to the theory are the countless examples from the rich history of film of highly suspenseful, tension-filled, and in other ways involving scenes that lack anthropomorphic camera movements or that contain non-anthropomorphic ones.

In Notorious, right after the scene in which Alicia steals the key and is nearly caught by Alex, there is a crane shot in which the camera, having panned across the party in the hallway below from a first-floor landing, glides smoothly down toward Alicia talking to Alex and some guests in the hallway and ends in a close-up on her hand holding the key to the cellar.

Given that no human being could perform this movement, our mirror neurons shouldn’t be able to simulate it and produce a feeling of involvement in it. Yet, I hypothesize that, for most viewers, this camera movement creates a strong sense of cognitive, emotive, aesthetic, and other forms of engagement in the scene.

Among other things, this movement prompts us to wonder how Alicia is going to gain entry to the wine cellar without her husband noticing, thereby intensifying our sympathetic concern for her and our suspense about whether she will be caught. And in its overtness, it might make us think about Hitchcock’s choice of technique and the reasons behind it. For some, it might even induce that sense of “spatiotemporal immersion” that Gallese and Guerra mention given that it brings our perceptual perspective close to Alicia’s in the midst of the party, although I personally don’t feel this.

Either way, in this case, it cannot be due to mirror neuron simulation that we experience these forms of immersion. This is a non-anthropomorphic camera movement that human beings cannot execute themselves and therefore cannot simulate with their mirror neurons.

An example from a film by a different director would be the shots in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) of Dr Floyd (William Sylvester)’s ship docking with a space station while Strauss’s Blue Danubewaltz plays on the soundtrack. (See image surmounting today’s entry.) For many, the smooth camera movements through space in this sequence evoke an intense sense of weightlessness, thereby creating a physical or corporeal form of involvement in the film. Yet, very few of us have moved in space or have experienced weightlessness, meaning that our mirror neurons should not be able to simulate these camera movements.

Then there are the copious examples of involving scenes that lack camera movement. Hitchcock’s oeuvre contains many, such as the infamous shower scene in Psycho (1960), which is devoid of camera movement during the 20 seconds or so in which the stabbing of Marion Crane takes place. Another example is the highly suspenseful sequence in Strangers on a Train (1951) in which Bruno (Robert Walker) drops Guy (Farley Granger)’s cigarette lighter down a drain while he is on his way to plant the lighter at the amusement park where he murdered Guy’s wife, Miriam (Kasey Rogers). Bruno wishes to implicate Guy in the murder, and Guy, who is a professional tennis player, has guessed Bruno’s plan and is trying to complete a tennis match in time to stop him from planting the lighter. Hitchcock cuts back and forth between the tennis match and Bruno’s efforts to reach down into the drain and retrieve the lighter.

Interestingly, while there is some camera movement at the beginning of the sequence, as the suspense builds, the camera movement lessens. Hitchcock relies largely on still shots of Bruno’s grimacing face as he reaches into the grate, his hand inside the grate and the lighter below it, and the faces of the referees and spectators at the tennis match. Only the shots of Guy and the other tennis player contain a little movement when the camera slightly reframes them as they move to hit the tennis ball.

This sequence is considered one of the most suspenseful (and thereby emotionally involving) in Hitchcock’s oeuvre, yet it defies Gallese and Guerra’s prediction that “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.”

So does the astonishing sequence in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) in which Horace (Herbert Marshall), having told his estranged wife, Regina (Bette Davis), of his plans to leave his fortune to their daughter, begins experiencing painful symptoms of his heart disease as she tells him how much she despises him.

Horace reaches for his heart medication but knocks over the bottle and its contents and begs his wife to fetch another bottle of medication from upstairs. She, however, sits immobile while Horace, realizing she will not help him and wants him to die, staggers around her, clinging to the wall, and stumbles upstairs before collapsing on the staircase. An agonizing long take lasting about forty seconds shows Regina in medium shot sitting while her husband, who is out of focus, moves toward the stairs, and the shot is immobile except for slight reframings to keep Horace partly visible in the shot.

This is an intensely suspenseful, emotionally involving moment as we wonder whether Horace will reach his medication in time, or Regina or someone else will take action to help him. Yet, there is no anthropomorphic camera movement to elicit our sense of involvement in the scene. On the contrary, according to many critics, it is precisely the lack of camera movement that contributes to its emotional intensity. As André Bazin noted, “Nothing could better heighten the dramatic power of this scene than the absolute immobility of the camera,” in part because it mirrors and emphasizes the “criminal inaction” of Horace’s wife, Regina, who is hoping he will fail to reach his medication and die so that she can be rid of him and claim his fortune.

Gallese and Guerra could perhaps protest that I have misconstrued their theory. Although their claim that “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements” seems to suggest that anthropomorphic camera movement is both a necessary and sufficient condition for occasioning involvement in a film, they might admit that immersion can be elicited in other ways. Instead, they could allow, human-like camera movement is merely a sufficient condition for involvement, not a necessary one. When it is present, we feel immersed in films, although this is not the only route to immersion.

However, it is not difficult to think of films containing lots of camera movement of both the anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic kinds that fail to engage viewers. An example is Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), a film in which, as David Ansen of Newsweek put it, “The camera, and the actors, are always in a mad dash from here to there” (Ansen 1994). Nevertheless critics, who according to Gallese and Guerra “usually get much more excited” when camera movement is present, largely panned the film. (For what it’s worth, the film has a critics’ score of 38% and audience score of 49% on Rotten Tomatoes.) As Ansen put it:

What we get is Romanticism for short attention spans; a lavishly decorated horror movie with excellent elocution. [Branagh’s] strategy undermines itself–there’s a lot of sound and fury, but all the grand passions are indicated rather than felt. Watching the movie work itself into an operatic frenzy, one remains curiously detached: the grand gestures are there, but where’s the music? [My emphasis.]

Anthropomorphic camera movements do not, therefore, even appear to be a sufficient condition for immersion in a film, let alone a necessary one.

The way forward?

Gallese and Guerra, it seems to me, cherry-pick examples from films that appear to support their theory, and ignore obvious counterexamples even in the films they examine. They also mischaracterize scenes such as the one in which Alicia steals the keys, overlooking other evident sources of “involvement,” a term they fail to define consistently. They do, I suspect, because they are in thrall to the mirror neuron theory, and they therefore force the art to fit the theory.

None of this means that cognitivism should be abandoned and that film scholars shouldn’t be turning to science. Nor does it mean that camera movement doesn’t sometimes elicit and intensify emotions such as suspense. Moreover, neuroscience may well be able to shed light on some of the reasons why this happens, although many more experiments are needed to demonstrate this than the single one relied on by Gallese and Guerra.

But it does suggest that our engagement with the sciences should be governed by two principles.

First, when drawing on a scientific theory, it is crucial that film scholars also consider criticisms of it. Despite its authority, scientific research is typically provisional. Those of us in the humanities are not usually in a position to determine who is right in a scientific debate. So we should entertain criticisms of the scientific theory, in case they reveal pitfalls and other problems in applying the theory to cinema, or show the theory to be on far less secure ground than it may seem to be.

Second, those of us who are humanistic scholars of film should trust the knowledge we have gleaned from decades of work on the cinema. We shouldn’t simply accept conclusions that contradict this knowledge because they are supposedly scientific. We should not, in other words, be cowed by the authority of science. While we haven’t gotten everything right, most of us know from a little reflection, for example, that anthropomorphic camera movements aren’t required for greater “involvement” in a film.

Of course, we should allow for the possibility that our assumptions about these and other matters are incorrect. But given the weight of experience and knowledge behind them, the evidentiary bar should be set very high for their disconfirmation by empirical scientific research.

Thanks to Malcolm for all his work in preparing this version of his paper for our blog. Another essay of his along these lines is “Can Scientific Models of Theorizing Help Film Theory?” in Philosophy of Film: Introductory Texts and Readings, ed. Angela Curran and Tom Wartenberg (Blackwell, 2004), 21-32

Quotations from Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra’s Empathic Screen come from pp. 68, 111, 91, 94, and 114. Their claims about Notorious are found on pp. 53-58. The quotation from their earlier piece can be found in “Embodying Movies: Embodied Simulation and Film Studies,” Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image (2012) 3: 188.

The crucial experiment is documented in Katrin Heimann et al., “Moving Mirrors: A High-Density EEG Study Investigating the Effect of Camera Movements on Motor Cortex Activation during Action Observation,” The Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience (2014), 26,9: 2087-2101. with the discussion of involvement coming on p. 2097. The Marco Iacobobi citation comes from Mirroring People: The New Science of How We Connect with Others (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), 5.

Pinker’s remarks about mirror neurons and empathy are to be found in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Penguin, 2011), 577. The quotations from Dan Shaw are from “Mirror Neurons and Simulation Theory: A Neurophysiological Foundation for Cinematic Empathy,” in Current Controversies in Philosophy of Film, ed. Katherine Thomson-Jones (Routledge, 2016), 148, 151.

André Bazin discusses The Little Foxes in “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work, ed. Bert Cardullo (Routledge, 1997) 3, 4. A blog entry here supplies further thoughts on the famous scene, which DB also analyzes in On the History of Film Style.

Donald Spoto discusses Hitchcock’s working methods in The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock (Da Capo, 1999; Centennial Edition), 284-287. David Ansen’s strictures on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein appeared in “Monster Mush,” Newsweek (6 November 1994). More on Notorious is here.

During the current health crisis, Berghahn has made all issues of Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind freely available. Several articles over the years debate issues around cognitive film theory and brain-based explanations of media effects. Malcolm Turvey has made many contributions to Projections; see especially his book review here.

2001: A Space Odyssey.

Friendly books, books by friends

Moses and Aaron (1974).

DB here:

When the stack of books by friends threatens to topple off my filing cabinet, I know it’s time to flag them for you. I can’t claim to have read every word in them, but (a) we know the authors are trustworthy and scintillating; (b) what I’ve read, I like; (c) the subjects hold immense interest. Then there’s (d): Many are suitable seasonal gifts for the cinephiles in your life (which can include you).

Happy birthday, SMPTE

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

Starting off in 1916 as the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, this peerless record of American moving-image technology has gone through many changes of name and format. It’s now The SMPTE Motion Imaging Journal. Its back issues have been a treasure house for scholars studying the history of movie technology, and it has outdone itself for its 100th Anniversary Issue, published in August.

It includes survey articles on the history of film formats, cameras and lenses, recording and storage, workflows, displays, archiving, multichannel sound, and television and video. There’s even an overview of closed-captioning. The issue costs $125 for non-SMPTE members, and it’s worth it. Many libraries subscribe to the journal as well.

A highlight is John Belton’s magisterial “The Last 100 Years of Motion Imaging,” which includes twenty-two pages of dense timelines of innovations in film, TV, and video. They stretch back beyond 1916, to 1904 and the transmission of images by telegraph. John’s article is provocative, suggesting that we might think of digital cinema as returning to film’s origins in handmade images for optical toys.

Lucas predicted that digital postproduction brought film closer to painting, and for more and more filmmakers that prediction is coming true. I was startled to learn that 80% of Gone Girl was digitally enhanced after shooting.

Yes, sir, that’s our BB

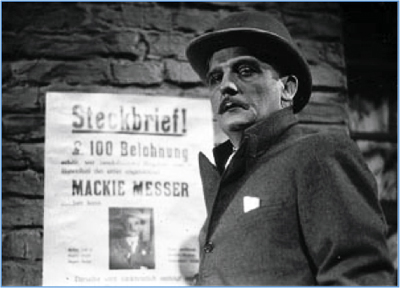

Die 3 Groschen-Oper (1931, G. W. Pabst).

During the 1970s, Bertolt Brecht’s name was everywhere in film studies. He epitomized what an alternative, oppositional, or subversive cinema ought to be. Cinema, even more powerfully than theatre, was a machine for producing illusions. So in his name critics objected to happy endings, plots that tidied up reality, characters with whom we ought to identify, messages that masked the real nature of bourgeois society. Films made all these things seem part of the natural order of things.

The Brechtian antidote was, as people used to say, to “remind people they were watching a film.” This was done by rejecting what he called the Aristotelian model and replacing it with the “alienation effect”: a panoply of distancing devices like intertitles, characters addressing the camera, actors confessing they were actors, and a display of the means of cinematic production (including shots of the camera shooting the scene).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

The promise was that once viewers were banished from the imaginary world of the film they would exercise their intellects and coolly appraise not only the fiction machine but its ideological underpinnings. Godard was the chief cinematic surrogate for Brecht, and La Chinoise (1967) became the big prototype of Brechtian cinema—unless you preferred the more austere version incarnated in Straub/Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1967) and their adaptation of Othon (1969). The ideas spread fast, helped by the user-friendly Brechtianism of Tout va bien (1972).

Brecht became part of Theory. In French literary and theatrical culture of the 1950s, his ideas on staging and performance had claimed the attention of Roland Barthes and other Parisian intellectuals. Godard was alert to the trend early, it seems; he had fun in Contempt (Le mépris, 1963) citing the two BB’s (the other was Brigitte Bardot, bébé), and letting Lang quote a poem by his old collaborator and antagonist. By the time Anglo-American film theorists were ready for semiotics, Brecht was offering support. Didn’t his anti-illusionism chime well with the belief that all sign systems were arbitrary and culturally relative?

My summary is too simple, but then so were many borrowings. Soon enough any highly artificial cinematic presentation might be called “Brechtian,” though usually minus the politics. In the academic realm, Murray Smith’s book Engaging Characters (1995) pointed out crucial weaknesses in the anti-illusionist, anti-empathy account. By then, the certified techniques were becoming part of mainstream cinema. Thereafter, we had Tarantino’s section titles and plenty of movies breaking the fourth wall. Brecht might have enjoyed the irony of using the to-camera confessions of The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) bent to support cynical swindling. Isn’t The Big Short (2015) a sort of Hollywoodized lehrstück (“learning play”)?

Brecht’s writings should be read and studied by every humanist and certainly everybody interested in film. They’re clear, blunt, and often sarcastic.

This beloved “human interest” of theirs, this How (usually dignified by the word “eternal,” like some indelible dye) applied to the Othellos (my wife belongs to me!), the Hamlets (better sleep on it!), the Macbeths (I’m destined for higher things!), etc.

Now Marc Silberman, our colleague here at Madison, has completed a trio of books that make the master’s work available. Bertolt Brecht on Film and Radio includes essays, scripts, and the Threepenny Opera lawsuit brief. There’s also Brecht on Performance and a complete revision of that trusty black-and-yellow volume dear to many grad students: Brecht on Theatre. The latter two collections Marc worked on with collaborators. All are indispensible to a cinephile’s education. As Brecht imagined a bold political version of music he called misuc; can we imagine a cenima?

From BB to S/H

Speaking of Straub and Huillet, every decade or so somebody comes out with a book about them. This time we have to thank the admirable Ted Fendt, in the twenty-sixth volume in the series sponsored by the Austrian Film Museum (as well as the Goethe Institute and Synema). Like the Hou Hsiao-hsien volume (reviewed here), Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet is fat and full of ideas and information.

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

There are interviews, tributes from filmmakers (Gianvito, Farocki, Gorin), and Fendt’s account of distribution and reception of their films in the Anglophone world. This last includes charming facsimile correspondence, with one Huillet letter pockmarked by faulty typewritten o’s. As you’d expect, she is objecting to making a 16mm print of Moses and Aaron (1974) from the 35. (“No, definitively.”)

Starting things off is a lively and comprehensive survey of the duo’s careers by Claudia Pummer, with welcome emphasis on production circumstances and directorial strategies. The book wraps with a detailed thirty-page filmography and a substantial bibliography.

My thoughts about S/H are tied up with their earliest work, when I first learned of them. So I loved, and still love, Not Reconciled (1965) and The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach. I also have a fondness for Moses and Aaron, Class Relations (1983), From Today until Tomorrow (1996), and Sicilia! (1998). I find others out of my reach, and several others I haven’t yet seen. People I respect find all their work stimulating, so I suspect it’s really a matter of gaps in my taste.

Whether you like them or not, they’re of tremendous historical importance. Without them, Jim Jarmusch and Béla Tarr, and of course Pedro Costa and Lav Diaz, would not have accomplished what they have. And especially in December 2016, we ought to find their unyielding ferocity inspiring. Remember them on Dreyer: “Any society that would not let him make his Jesus film is not worth a frog’s fart.” Brecht would have approved.

Stone’d

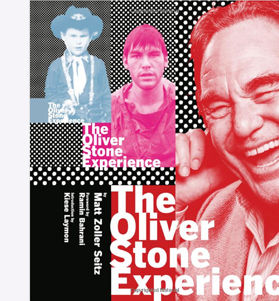

To the minimalism of Straub and Huillet we can counterpoint the maximalism of Oliver Stone, the most aggressive tabloid American director since Samuel Fuller (although Rococo-period Tony Scott gives him some competition). After two books on Wes Anderson, Matt Zoller Seitz has brought us a booklike slab as impossible as the man’s films. Can you pick it up? Just barely. Can you read it? Well, probably not on your lap; better have a table nearby. Does its design mirror the maniacal scattershot energy of films like JFK (1991), Natural Born Killers (1994), and U-Turn (1997)? Watch the title propel itself off the cover.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The Oliver Stone Experience is basically a long interview, sandwiched in among luxurious photos, script extracts, correspondence, and the sort of insider memorabilia that Matt has a genius for finding. We get not only pictures of Stone with family and friends, on the set, and relaxing; there are bubblegum cards from the 40s, collages of posters and filming notes, maps, footnotes, and shards of texts slicing in from every which way. Newspapers, ads, and production documents are scissored into the format, including a Bob Dole letter fundraising on the basis of the naughtiness of Natural Born Killers. Beautiful frame enlargements pay homage to the split-diopter framings of Born on the Fourth of July (1989) and the shadow of the 9/11 plane sliding up a facade in World Trade Center (2006). When Stone had second thoughts about things he’d said, Matt had the good idea of redacting the interview like a CIA file scoured with thick black lines.

The whole thing comes at you in a headlong rush. Amid the pictorial churn and several essays by other deft hands, we plunge into and out of that stellar interview, mixing biography and filmmaking nuts-and-bolts. Matt gets deep into technical matters, such as Stone’s penchant for rough-hewn editing, as well as raising some big ideas about myth and autobiography. There are occasional quarrels between interviewer and interviewee. Out of the blue we get remarks like “Alexander was not only bisexual, he was trisexual,” which was not redacted.

The book’s very excess helps make the case for Stone’s idiosyncratic vision. Matt’s connecting essays, along with the vast visual archive he’s scavenged and mashed up, made me want to rethink my attitude toward this overweening, sometimes crass, sometimes inspired filmmaker. He now seems a quintessential 80s-90s figure, as much a part of the era as Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Stone emerges as a resourceful defender of The Oliver Stone Experience, articulating a radical political critique with gonzo verve.

Rhapsody in white

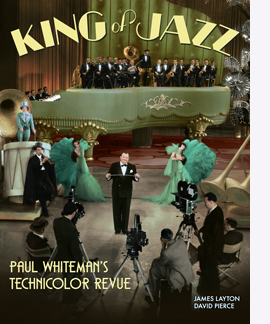

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

If lifting the Book of Stone doesn’t suffice for exercise, try another weighty and sumptuous item, King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue, by James Layton and David Pierce. Last spring the Museum of Modern Art premiered one of the most ravishing restorations I’ve ever seen, a digital version of King of Jazz (1930).

This period piece is in its own way as wild as an Oliver Stone movie. From its opening cartoon of Paul himself as a Great White Hunter bagging a lion, it’s a virtually self-parodying account of how a black musical tradition got netted, trussed up, and caged for the swaying delectation of white audiences. (No need to mention the irony of the name of our King.)

Along the way we have some straight-up songs (including some by Bing Crosby) spread among extravagant dance numbers. The Universal crane gets a workout as well. The music is infectious, the performers sweating to please, and the restoration–coming, I hope, to your screen soon–finally shows what two-color Technicolor could do. This is the definitive version of a film too often known in cut versions with shabby visuals and sound.

The book is an in-depth contextualization of the film, the studio, and the tradition of musical revues, both on stage and in film. It records the production and reception, with rich documentation throughout. The story of assembling the restoration is there too, and it’s a saga in itself. David is one of the moving spirits behind the online Media History Digital Library and its gateway Lantern. James is Manager of the Celeste Bartos Film Preservation Center at the Museum of Modern Art. Their collaboration has given us both a lush picture book and a serious, always enjoyable piece of scholarship. Their book proves the value of crowdsourcing: funded by online subscription, it was self-published. In this and much else, it can be a model for film historians pursuing questions that commercial and university presses might find too specialized. The result is a model of ambitious research, writing, and publishing.

Visiting Radio Ranch

Gene Autry in The Phantom Empire (1935).

For about thirty years I’ve been arguing that one fruitful research program in film studies involves what I call a poetics of cinema: the study of how, under particular historical conditions, films are made to achieve certain effects. This program coaxes the researcher to analyze form and style, study changing norms of production and reception, and consider how filmmakers work in their institutions and creative communities, with special focus on craft routines, work methods, and tacit theories about the ways to make a movie.

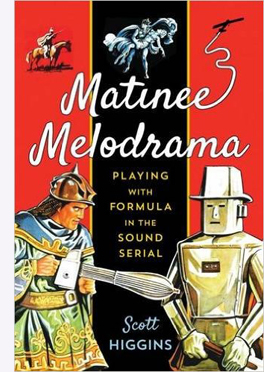

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”

A sturdy example of this approach has appeared from Scott Higgins. His Matinee Melodrama fulfills the promise of its subtitle: Playing with Formula in the Sound Serial. Scott has closely examined this widely despised genre, plunging into the 200 “chapterplays” produced in America between 1930 and 1956. They offer bald and bold display of the rudiments of action-based storytelling: “If Hitchcock built cathedrals of suspense from fine brickwork of intersecting subjectivities and formal manipulations, sound serials used Tinkertoys.”