Archive for June 2014

12 hours, Ritrovato time

DB here:

Reporting on the magnificent Cinema Ritrovato festival at Bologna has become a tradition with us, but it’s become harder to find time during the event to write an entry. The program has swollen to 600 titles over eight days, and attendance has shot up as well; the figure we heard was over 2000 souls. The organizers–Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée–have responded to requests for more repetition of titles by slotting shows in the evening, some starting as late as 9:45. (You can scan the daily program here.) There are as well panel discussions, meetings with authors, and some unique events, such as carbon-arc outdoor shows, the traditional screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, and Peter Kubelka’s massive and mysterious Monument Film. Add in time to browse the vast book and DVD sales tables, and the need to socialize with old friends.

In all, Ritrovato is becoming the Cannes of classic cinema: diverse, turbulent, and overwhelming. How best to give you a sense of the tidal-wave energy of the event? I’ve decided to take off one morning and write up just one day, Monday 29 June. I don’t know when Kristin and I will find time to write another entry, for reasons you will discover.

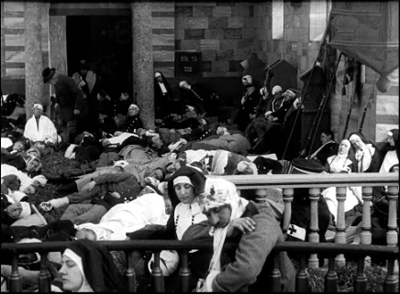

9:00 AM: Ned Med Vaabnene! (Lay Down Your Arms!, 1914) was a big Danish production, based on a popular anti-war novel by the German Bertha von Suttner. It’s a remnant of the days when the rich went to war along with the common folk. (Sounds quaint in today’s America, where the elite have other priorities.) The Nordisk studio specialized in “nobility films,” melodramas that show the upper class brought low by circumstances; Dreyer’s The President (1919) is another example. The film, directed by Holger-Madsen, shows a family devastated by war and its aftermath. It’s shot in tableau style, with the restrained acting and sumptuous, light-filled sets characteristic of Nordisk. The combat scenes are remarkably forceful, but the most harrowing scene, for me, is the shot showing a battlefront hospital, with exhausted nuns and wounded men strewn around the shot–a tangle of limbs and heads.

Premiered soon after the Great War broke out, Lay Down Your Arms! anticipates Nordisk’s wartime policy. Denmark was a neutral country, and the Danish industry depended on both the German and the American markets. As a result, most of the films studiously avoided taking sides. After the war, with the revival of the German industry and the circulation of American films in Europe, Nordisk lost its powerful position in the international market.

The entire film is available for viewing online at the Danish Film Institute site.

Programmer Mariann Lewinsky, in charge of the “100 Years Ago” thread, wisely included other pacifist films from the mid-teens. One of the high points was the evening screening, on the Piazza Maggiore, of the fine Belgian film Maudite soit la guerre (1914), in the hand-colored version I discussed some years back. Not by accident, I suspect, Lay Down Your Arms! featured several Lewinsky dogs.

10:30 AM: Werner Hochbaum was an unknown name to me, but after seeing Morgen beginnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow, 1933), I realized that was my loss. This story of a cafe violinist released from prison is a sort of anthology of 1920s International Style devices: canted angles, rapid montages, City Symphony passages, flamboyant camera movements, multiple-image superimpositions, and huge close-ups of faces, hands, and objects. The work on sound is no less ambitious, with voice-overs, sound motifs (a carousel, a canary’s call-and-response to a chiming doorbell), offscreen dialogue, and harsh auditory montages of traffic and city life. Everything from Impressionist subjective-focus point-of-view to Expressionist shadow work comes into play.

The plot is gripping throughout. At first we don’t know why the violinist was imprisoned, and we learn about the case first from his gossiping neighbors (excellent run of whispers during fast-cut close-ups of housewives), then from his own flashbacks, which build up to a revelation of the murder he committed. Threaded with all this is another uncertainty: Has his wife begun a love affair while he was in jail? Giving us only glimpses of her life as a cafe waitress, Hochbaum leads us to suspect that he will come home to more misery–and perhaps another temptation to murder.

Along with all this were arresting side scenes of cafe life, like a fat woman ordering up a gigolo to dance with her, reminiscent of Georg Grosz and the New Objectivity’s cynical portrait of daily desperation. It’s a lot to pack into 73 minutes, but Morgen beginnt das Leben succeeds smoothly and made me want more. Alex Horwath‘s introduction confirmed that this is a director we should know better. We can hope that a DVD edition is coming soon.

Noon: A packed house for the panel of three American studio archivists: Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox, Grover Crisp of Sony, and Ned Price of Warners. Too many ideas to summarize here, but one that emerged: Digital tools are great for restoration, not so reliable for preservation.

Ned (left) emphasized that now scanners are very sensitive to the oldest negatives, with their shrinkage and warpage. But Ned pointed out that today’s monitors don’t often render the full color scale needed to respect film’s tonal range, so that weak monitors mean that we are “working blind” and may “bake in” flaws that will be evident when display devices improve. Likewise, low bit-depths (often only 10-bit) in outputting to film for preservation can cause problems later. Grain reduction is another big problem. Grover (center) added: “When you do anything to grain, you’re denaturing the film.”

On the restoration front, Schawn showed clips from the 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth, first from a beautiful photochemical restoration of twelve years ago, then from a recent digital one. To my eye, the warm skin tones of the 35mm image were more attractive than the almost porcelain surfaces of the digital version, but the latter was sharper and contained a healthy amount of grain. Grover screened A/B comparisons of the main titles of Only Angels Have Wings and Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa (Sandra ), both of which showed how handily digital restoration creates a rock-stable image, without the jitter and weave unavoidable with a strip of film.

All the panelists agreed that digital restorations are rapidly improving; ones finished only a few years ago could now be done better. A major problem coming up is that younger restoration workers know the digital tools better than the look and feel of photochemical, particularly the surface of older films. Grover recalled that one eager techie added flicker to a Capra silent because he thought that was how old movies looked.

1:15 PM: Hurried lunch with Schawn. Main topic: The Grand Budapest Hotel, but also the vagaries of the DVD and Blu-Ray market.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

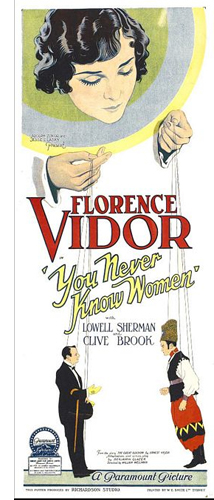

You Never Know Women (1926) is an exercise in good old classical storytelling. The plot presents Vera (Florence Vidor), star of a troupe of Russian entertainers, momentarily entranced by a no-good millionaire who wants to seduce her. The magician of the troupe, Norodin (Clive Brook) loves her, but she’s unaware of her feelings for him until the Lothario’s true nature is exposed. El Brendel adds spice as a clown devoted to his pet duck.

Variety‘s review was ecstatic, claiming that “Wellman at the megaphone lifts himself into the ranks of select directors with by his handling of this story, for his direction is never obvious or old-fashioned.” I’ll say. Filled with running gags, seesawing conflicts, and motifs (Ivan’s skill at knife-throwing, the expletive, “Ridiculous!”), You Never Know Women has a headlong pace. With nearly a thousand shots in 70 minutes, it relies on glances, gestures, and reactions to channel the dramatic flow. It needs only three expository titles, letting its 100 or so dialogue titles pinpoint key emotional transitions. In anticipating the sound cinema that was just around the corner, You Never Know Women resembles the more famous Beggars of Life (1928, given pride of place at Ritrovato), which as I recall uses dialogue titles exclusively.

The Man I Love (1929) tells the familiar story of a prizefighter who, as he rises in the game, leaves his loyal woman behind. As an early sound film, it relies on multiple-camera shooting for extended dialogue scenes, but Wellman enlivens the staging with unusual angles, including a view of a quarrel seen through a window in a dressing-room door. The Man I Love boasts the sort of ambitious, somewhat bumpy tracking shots we sometimes find in early talkies. One swaggering camera movement takes us from the locker room into an arena, down the aisle, past the ring, and to Dum Dum’s anxious wife in the crowd, a sketchy prefiguration of the celebrated Steadicam movement in Raging Bull. The fight scenes, not requiring sync sound, are shot with brio, while the dialogue scenes are extremely well-miked, allowing for fairly fast line readings and varied volume and emphasis in the voices.

Gina Teraroli and David Phelps, along with other colleagues, have assembled a wide-ranging dossier on Wellman’s work that serves as a fine complement to the Ritrovato thread.

5-something PM: One of the things in the first edition of our Film History: An Introduction that made me proud was the inclusion of sections on Indian cinema, a subject usually ignored in textbook surveys. I remember in the late 1980s and early 1990s watching the 1950s-1960s classics of Hindi filmmaking with a sense of discovery: How could we not have known this invigorating tradition? It was therefore with a sense of homecoming that I visited Raj Kapoor’s Awara (“The Vagabond,” 1951), in a pretty sepia-tinted print.

The young ne’er-do-well Raj (no last name, and this is important) is on trial for attacking a judge in his home. A female lawyer, Rita, takes up his defense and urges the judge, on the witness stand, to tell why he expelled his wife from his home many years ago. The wife had been kidnapped by the gangster Jagga, and the judge assumed that the child she was now expecting was Jagga’s. Before the courtroom, Rita recounts up the story of how young Raj, actually the judge’s legitimate son, took up a life of crime. To add spice, Rita is the judge’s ward and Raj’s lover.

No coincidence, no story, they say, and Awara offers plenty of timely misunderstandings and improbably neat encounters. No matter. We’re told that TV narrative, by stretching its tale over several hours, can introduce novelistic breadth, but so can Indian classics of the 1950s. This one takes us across twenty-four years and as many ups and downs as a mini-series might offer. Not to mention Kapoor’s vigorous visual style, with huge sets, vivacious fantasy sequences, and traces of 1940s Hollywood hysteria (chiaroscuro, fluid track-ins to overwrought faces, even thunder and lightning in the distance). Here Raj, about to stab the judge, shatters the childhood picture of Rita; her simple gaze checks his moment of revenge.

Then there are the songs, lusciously sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Mukesh. Of course the sprightly “Awara Hoon” is the official classic and Kapoor’s signature tune, but this time around my favorite was the duet, “I wish the moon…,” with Rita asking the moon to look away and Raj asking it to turn to him. With its glamorized social realism, its tale of a good boy gone wrong, unjustly punished, and eventually redeemed, and its primal themes of mothers, fathers, and sons, Awara is a milestone in the world’s popular cinema…. and just one of several Indian classics in this year’s Ritrovato.

That was one day. Now I’m off to…what? Polish films in widescreen? The Riccardo Freda retrospective? The rare Ojo Okichi? Or maybe the restored Oklahoma!? In any case, this afternoon an incontro on Nicola Mazzanti‘s book 75000 films, and tonight Guru Dutt’s glorious Pyaasa.

I tell you, it’s hard to keep up, running on Ritrovato time.

Nargis and Raj Kapoor sing to the moon in Awara.

Prague summer

The Ascension of Christ, panel from the Vyšši Brod Altarpiece, ca. 1350. Convent of St. Agnes, Prague.

DB here:

Kristin and I are in Prague for about a week, in connection with two lectures I’m giving Wednesday and Thursday.

In the meantime, we’ve met with friends. After we arrived we had a lively dinner with Radomir Kokes, specialist in Czech silent film. Last night we met with Petra Dominková and Vaclav Kofron, translators of the Czech editions of Film Art and Film History, and Michal Bregant, head of the National Film Archive (and who also contributed to the translation of Film History). During that enjoyable evening we learned, among other things,that film lovers of Michal’s generation took the train to Hungary to see American films that didn’t make their way into their country.

Later, meeting with Radomir and our principal host Lucie Česálková , we learned of their robust, long-lived journal Iluminace, which publishes film research in both Czech and English. The most recent issue is devoted to studies of film festivals.

So far we’ve spent the rest of our time visiting museums. Prague is bursting with rich collections of European art from all eras. Today (Tuesday) we went to one of the major venues, the Convent of St. Agnes, which houses a vast array of Bohemian medieval and early Renaissance painting and sculpture.

There were plenty of images to give us pleasure. One of the most spectacular set of items was a series of fourteenth-century altar panels representing the life of Jesus. Each one gave what seemed to me a fresh interpretation of the major episodes–annunciation, nativity, etc.–but especially striking was the one devoted to the Ascension. After being resurrected, Jesus is lifted to heaven; but contrary to what we usually see, the action is represented “offscreen.” All we see are Jesus’ feet, as above. A nice touch Kristin noticed: He left his footprints in the earth.

I’m drawn to such peculiar treatments of conventional material. There were some other instances in other Prague galleries. Take this piercing image of the mockery of Jesus, in an unidentified Netherlandish painting from the first half of the sixteenth century. The torturers are blowing a cowhorn at Christ, banging a pot, pressing a stool against his head, thrusting a rod into his mouth, and spraying him with a flit gun.

Most remarkably, at the bottom of the composition one man fills a basin with what seems to be shit, while another man dips a cloth in it, as if preparing to apply it to Christ’s face. The suggestion is reinforced by the wizened man on the far right holding his nose.

Such visceral images remind you that holy pictures can be pretty ornery. They also remind you of Jan Švankmajer, that great Czech animator. So far, there’s no museum dedicated to him, but following Petra’s suggestion we did visit the Karel Zeman Museum, just off the Charles Bridge. It offers enjoyable attractions tracing Zeman’s career, with emphasis on Journey to the Beginning of Time (1955) and The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958). Kristin hopes to write at greater length about the museum and Zeman later this summer.

Tomorrow: Off to the world-renowned archive to watch Czech silent films. Who knows what we’ll find?

Thanks to Lucie Česálková and all her colleagues for making our visit possible. Thanks also to Michal Bregant for a correction in the original posting of this entry.

Kristin and I wrote about Švankmajer’s remarkable Dimensions of Dialogue (1982) in the latest edition of Film Art. At the Zeman Museum we discovered a beautiful 2013 book on the filmmaker, available here.

DB at the porthole of Nemo’s Nautilus in the Zeman Museum.

Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book

Gipsy Anne (1920).

Kristin here:

A stack of new DVDs/BDs and books has been gradually building up on the floor in a corner of my study. I’ve been meaning to blog about them, but first I had to catch up with viewing and reading. Or did I? With this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato starting next week, I suddenly realized that the DVDs at the bottom of the pile were ones I bought there last year! Clearly, I would never catch up.

So this entry aims to notify you of releases, many obscure, that you may so far have missed. Mostly the DVDs and BDs come from the dedicated archives and independent home-video companies that release historical rarities and restorations.

Early Scandinavian films

I don’t think I had ever seen a Norwegian silent film, apart from the one Carl Dreyer made there, Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1925). Though produced between Master of the House and the wonderful La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, The Bride of Glomdal is unquestionably one of Dreyer’s lesser works.

In the sales room at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, one stand was selling four new releases of Norwegian and Swedish silent and early sound films. All were issued by the Norsk FilmInstitutt.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

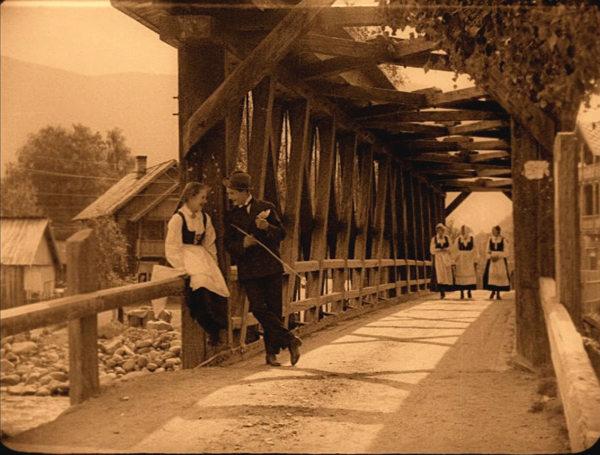

This is the only one of these Norwegian films that I have so far watched, and it’s a remarkable one. Clearly Breistein and his cinematographer Gunnar Nilsen-Vig were influenced by the great Swedish films of Sjöström and Stiller, and though Gipsy Ann is not up to the best work of those two, it shares the same feeling for landscape for for allowing a melodramatic situation to develop slowly and in unexpected ways.

It tells the story of a foundling child, Anne taken in by a widow who owns a large farm and who raises the girl alongside her son, Haldor. Haldor is a timid boy, constantly led astray by the adventurous Anne. Once they grow up, the two fall in love, but Haldor’s mother pushes her son into an engagement with a young woman from a well-to-do family. In the meantime, Jon, a humble tenant farmer working for the widow, falls in love with Anne, who snubs him.

Gipsy Anne has none of the clumsiness in lighting and staging that one so often sees in European films of the period around 1920. The cinematography is beautiful, as the frame at the top shows. Breistein has mastered shot/reverse shot and other aspects of analytical editing. The lighting is impressive, with some interiors using a strong backlight through windows and a soft fill that gives a sense of realism (left).

The film also sets up neat visual parallels. In a scene in Anne’s childhood (below left), she hides by an old farm building and curiously spies on some local lovers. Much later, she lurks heartbroken by Haldor’s lavish new house as he shows it to his fiancée:

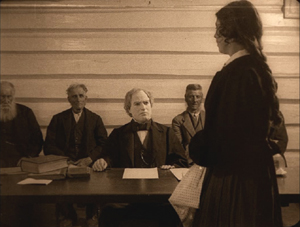

There are even some planimetric shots that yield dramatic compositions, one when Jon comforts the young Anne when she learns that she was adopted, and another, much later, when Anne is in court testifying about the fire that burned down Haldor’s new house:

Again there is a parallel, since Anne is hiding her own guilt in starting the fire, and Jon is about to falsely confess to the crime to protect her. (There’s also a hint at influence from Dreyer in that courtroom shot.)

Of the four releases, Fante-Anne is the only one put out in a Blu-ray version, packaged along with a DVD and an informative booklet in Norwegian and English. The print, with toning and a pleasantly rustic-sounding score, has English subtitles. Oddly enough, the Norsk Filminstitutt does not have an online shop. The film is available from at least two Norwegian online dealers in Scandinavian videos, Nordicdvd and Dvdhuset. It can also be ordered from an American source, Blu-ray.com.

Markens Grøde (The Growth of the Soil) was made only a year later, in 1921; it was directed by Gunnar Sommerfeldt and is another rural melodrama, adapted from a Nobel Prize-winning novel of the same title. This release is 89 minutes long and includes subtitles in English, French, Spanish, German, and Russian. It, too, can be ordered from Nordicdvd and DVDhuset.

The third release is an epic film, Brudeferden i Hardanger (The Bridal Party in Hardanger, 1926). Its two parts run 104 and 74 minutes; it was also directed by Rasmus Breistein, with cinematography by Gunnar Nilsen-Vig. DVDhuset carries it, but not Nordicdvd. It is, however, available from Amazon.uk. It has English subtitles.

Finally there is “Bjørnson på film,” a compilation of three early films based on the pastoral writings of Nobel Prize-winning author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and was issued in 2010, the centenary year of the author’s death. Two of these are Swedish productions: Synnøve Solbakken (1919, director John W. Brunius) and Et Farlig Frieri (A Dangerous Proposal, 1919, director Rune Carlsten). Lars Hansen stars in both, and Karin Molander co-stars in Synnøve Solbakken. The third is an early Norwegian talkie, En Glad Gutt (A Happy Boy, 1932, director John W. Brunius).

After considerable searching, I can find no online source for this 2-DVD set. Perhaps it will become available. Otherwise you’ll have to come to Il Cinema Ritrovato and see if it’s on sale again. If not, at least you will have a great time!

All these releases are PAL, though Fante-Anne is also Blu-ray region B; they would all need to be played on a multi-standard machine.

(Mostly) American treasures

The well-known and invaluable “Treasures” series from the National Film Preservation Foundation has become somewhat difficult to keep track of. It started with “Treasures from American Film Archives: 50 Preserved Films.” That was followed by “More Treasures from American Film Archives: 1894-1931.” After that volume numbers appeared, and the references to archives were dropped in favor of thematic collections: “Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film 1900-1934” and “American Treasures IV: Avant Garde 1947-1986.” Then Roman numerals disappeared with “Treasures 5: The West 1898-1938.”(The ones linked are still in print.)

Now we have an unnumbered entry, but it’s still part of the series: “Lost & Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive.” Most readers will recall that in 2010 it was announced that about 75 films had been found in the New Zealand Film Archive. News coverage mostly centered on John Ford’s 1927 feature Upstream, which had up to that point been lost. That film forms the central attraction for this new release.

It also includes, however, an incomplete print of a distinctly non-American film, The White Shadow (1924). It was directed by Graham Cutts, but it is mainly of interest now as a film on which the young Alfred Hitchcock worked in several capacities. He wrote the script, based on a novel, and was assistant director, editor, and art director. Despite the enthusiastic tone of the program notes in the booklet accompanying this set, there is little detectable of the later Hitch. The story is ludicrously far-fetched, depending on the old good twin/bad twin contrast, with Betty Compson in both roles (above). At various points the twins pretend to be each other, much to the confusion of the bad twin’s fiancé, played by Clive Brook. The convoluted plot becomes even more so when a series of titles tries to convey the action of the missing final three reels.

The film has its moments. Cutts, who was a decent if not outstanding director, manages some lovely compositions, as with the backlighting in the night interior below left. As with many of Hitchcock’s sets for the film, this one is pretty standard-issue. He obviously had some fun with the set for the tavern called The Cat Who Laughs. It looks a bit jumbled, but it’s actually full of little areas that Cutts uses effectively for picking out pieces of action amid the chaos:

So the Treasures series moves on, as does the Foundation. Not all of the discovered prints made it onto the DVD set. Several more have been preserved since and generously made available for free online viewing at the Foundation’s website; more will be added as the restorations are completed.

Blu-ray USA

American classics continue to make their way onto BD.

Flicker Alley has teamed with the Blackhawk Films Collection to release The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923, director Wallace Worsley). No original 35mm negative or print is known to survive, so this release was mastered from a 16mm tinted copy struck at some point from the original negative. Some restrained digital restoration was done to clean it up a bit. The extras include an essay and audio commentary by Michael F. Blake and a 1915 film, Alas and Alack, with Chaney in his pre-movie star days playing a hunchback.

The film is available at Flicker Alley’s website, where you can also pre-order their three upcoming releases: a set of all Chaplin’s Mutual Comedies (1916-17); the first volume of The Mack Sennett Collection, including 50 films; and We’re in the Movies, which collects some early local films made by itinerant moviemakers, as well as Steve Schaller’s 1983 documentary, When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose, about the first film made in Wisconsin. There’s also a documentary about a small local theater in Los Angeles that showed silent films in the sound age.

D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation will celebrate its centennial next year, and now it’s also out on Blu-ray, from both Kino Classics in the USA and Eureka! in the UK. Both have the same new restoration from 35mm elements accompanied by the same score. The extras also appear to be identical–most notably seven Biograph shorts by Griffith about the Civil War. The main difference is that Kino throws in David Shepard’s 1993 restoration, with different musical accompaniment and a 24-minute documentary on the making of the film. Again, the Eureka! version is BD region B.

Last month Eureka! also released a BD of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951, BD region B) in their “Masters of Cinema” program. The release also contains a DVD version. You can check it out, along with other recent releases and upcoming ones here.

Edition-Filmmuseum

This German series works with an impressive array of archives, mostly German but also Swiss and Luxembourgian. The titles that result include modern films (Straub and Huillet figure in their catalogue, as does Werner Schroeter), television, experimental cinema (they’ve done several James Benning films), documentaries, and older films. (No Blu-ray as of now. Perhaps too expensive or perhaps just the sort of restraint that dictates the white backgrounds on their covers.)

Recently Edition-Filmmuseum released a set with two films by Gerhard Lamprecht, a little-known and but in the 1920s an important director of socially conscience films set among the working class. The two-disc release includes Menschen untereinander (1926) and Unter der Laterne (1928), each with two musical tracks to choose from. The German intertitles are subtitled in English and French, and the enclosed booklet is likewise trilingual. Like all the DVDs from this company, there is no region coding.

Similarly, another new release is devoted to the early films of Michail Kalatozov, a Georgian director better known for his Soviet films of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., The Cranes Are Flying and I Am Cuba). One of the films here is Salt for Svanetia (1930), one of those vaguely familiar but rare titles from the history books on Soviet montage cinema. The other is Nail in the Boot (1932).

Salt for Svanetia is indeed a classic that anyone interested in silent cinema and the Soviet Montage movement should see. Set in an extremely isolated, primitive area of the Caucasus, Svanetia obviously needs a dose of Soviet modernizing. The peasants can barely subsist, and a lack of salt makes their cows and goats unable to produce milk. It’s basically an attempt to combine an ethnographic documentary with large doses of Montage-style rapid editing, canted cameras, heroic framings of people against the sky. At one point a man cutting another’s hair is framed against one of the local feudal era towers in a low angle that makes it look like something out of Alexander Nevsky (above). The film is a fascinating peep into a little-known culture.

Kalatozov stages some sketchy scenes using the locals: an avalanche which kills some men, a resulting funeral, a woman giving birth alone in the countryside. There’s no over-arching plot, though, and the director wisely sticks with showing off local customs. Naturally at the end the Soviets are building a long road to reach the area, and there’s a promise of good things to come.

Nail in the Boot is impressive for about two-thirds of its length. It stages some large battle scenes between what I take to by the Red and White Armies during the Civil War. The Whites are attacking an armored train, and a lot of explosions result. The soldiers aboard the train fire machine-guns, and Kalatozov conveys the sound by alternating single-frame shots of the muzzle of the gun with single-frame shots of the man firing it. Sound familiar? It happens two or three more times in the course of this film. Both of these films are definitely part of the Montage movement, but the director has come along so late in it that he seems to feel all the good ideas have been used, and they’re worth using again. So we get another quotation from October in a canted shot of a cannon’s wheel, and Kalatozov even steals the idea of our hero looking and feeling very small and his prosecutor becoming a looming giant, as in Kozintsev and Trauberg’s The Overcoat:

We are some time into the film before we meet the hero, and I was thinking that this might be one of those Montage films with no single central figure. But well into it, the ammunition on the train is running out, and a messenger is sent to run and get help. Much of the film simply shows him running along, becoming increasingly lame as a bullet in his boot digs into his foot. Ultimately he does not reach his goal, though he tries hard. Once he is put on trial for treason, he blames the shoddy workmanship of the cobblers who made his boot badly. This seems a strange anti-climax after the exciting battle scenes earlier on, but the film actually turns out to be about Soviet workers paying attention to what they’re doing and not putting out a bad product. All the workers looking on at the trial look shame-faced at the hero’s accusation, suggesting that if a hundred percent of the workers are doing a bad job, there’s not much hope of rectifying the situation.

Both films are fascinating because they come so late in the Montage movement, which lasted from 1925 to 1933, and they are particularly valuable because it’s harder to see the films from this late period than those from the 1920s.

Both films have optional English subtitles.

By the way, Edition Filmmuseum also sells Flicker Alley films, and those in Europe and elsewhere might find them easier to order on its website.

You’re gonna need a bigger shelf

There are three notable new releases of French films. Before I get to the two epic, brick-like sets, let me mention the new Eureka! Blu-ray of Jacques Rivette’s Le Pont du Nord (1981) in the “Masters of Cinema” series. Admirably, the film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio. The supplements consist mainly of a thick booklet with some new essays, an interview with Rivette, and so on. You can read more about the booklet’s contents and buy the film here. Note that it is coded BD region B.

Now to the bricks.

At long last the French Impressionist director Jean Epstein is well represented on DVD. Although a few of his most famous films have appeared on video from time to time, these eight discs are a cornucopia of his work (plus a 68-minute documentary on his work by James June Schneider). They come from what are probably the best possible prints, since the set is issued by La Cinémathèque Française. Marie Epstein, who had made films herself in the late 1920s and 1930s, worked at the Cinémathèque for decades and helped preserve her brother’s work. A major retrospective of Epstein’s work ran at the Cinémathèque in April and May; the restorations in preparation for the series made possible to this DVD set. (This page links to further resources on Epstein.)

Epstein started out working for some of the large French film companies, though he mixed somewhat experimental films with more standard ones. His second surviving feature film, Cœur fidèle, is one of his most famous, and perhaps his masterpiece. A beautiful print of it is already available on a Eureka! DBD/BD combo (BD region B). There’s also a French DVD. I wrote a little about it when it made our top-ten films of 1923 list.

The big outer box of the set comes with three inner fold-out disc holders that reflect the phases of his career. The first is “Jean Epstein chez Albatros.” In 1924 Epstein joined the Russian-emigré company Albatros. Three of the four films he directed there are grouped together: Le Lion des Mogols (1924), starring Ivan Mosjoukine and Nathalie Lissenko; Le double amour (1925); and Les aventures de Robert Macaire (1925). The big gap here, and indeed in the entire set, is the absence of the fourth, L’Affiche (1924), which I think is one of his best. It does survive, so I hope it will eventually appear on disc. Apart from L’Affiche, these are all big-budget productions, and Robert Macaire is a serial running 200 minutes. This set has no overlap with the Albatros set from Flicker Alley that I wrote about last year and indeed is an excellent supplement to it.

Beginning in 1926, having been successful with his big Albatros films, Epstein produced his own work under the name “Les Film Jean Epstein.” Again, there were four films, the surviving three of which are on the discs in the second folder, “Jean Epstein: Première Vague”: Mauprat (1926), La glace à trois faces (1927), and La chute de la maison Usher (1928). (The lost film is Au pays de George Sand, 1926.) La chute de la maison Usher was for a long time the only Epstein film available on 16mm prints, which didn’t really do justice to its eerie German Expressionist-influenced sets.

Gradually, however, the reputation of La glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”) has grown, and it is another highlight of Epstein’s career. It introduced a trope of modernism into the cinema, the notion of using point of view to create ambiguity. The story shows scenes concerning one man as seen through the eyes of his three lovers–each, of course, making him seem a very different person.

The other films deserve discovery as well. Le Lion des Mogols has a clever story (written by Mosjoukine) which starts out in a fictional Tibetan city where the hero, a nobleman (Mosjoukine) incurs the sultan’s wrath and flees. A cut to a ship suddenly reveals that we are in a modern world, and the film becomes a fish-out-of-water story as the hero blunders onto the set of a movie location shoot on deck (above). Intrigued, the female star of the film helps him adjust and brings him in as a leading actor. Thus our hero jumps from one genre, the fantasy Far-Eastern melodrama (familiar from various German films of the time, including the Chinese sequence from Lang’s Der müde Tod) to a modern romance. The film has the advantage of scenes in and around Albatros’s own studio:

Les Film Jean Epstein produced some major work, but it didn’t make money, and in 1928 Epstein changed course, He made 28 more films, up until his death in 1953, most of which are virtually unknown. The exceptions are some films modest, lyrical films he shot in Breton. Seven of these are presented as “Jean Epstein: Poèmes Bretons”: Finis Terrae (1928, Epstein’s last silent film), Mor’vran (1930), Les Berceaux (1931) L’Or des mers (1933), Chanson d’Ar-mor (1935), Le tempestaire (1947), and Les feux de la mer (1948). These range from 6 minutes to 82 minutes long. Most have simple plots and involve the sea.

The set has been put together so that the supplements for each film are on the end of its disc, not lumped together on a separate disc. There is also a 158-page book, not booklet, with program notes and many images: posters, designs, publicity stills, and frames. (It also has the smallest page numbers I have ever seen.) I can find no indication that the set is region-coded, but the Amazon.fr page says it’s PAL region 2. (I cannot find any reference to the set on the Cinémathèque’s own site, so I can’t confirm either way.) It does have optional English subtitles.

Since the beginning of film history, France has produced one of the world’s great national cinemas, and Jacques Tati is one of its greatest directors. On Facebook, Ingrid Hoeben, one of Tati’s devoted fans, runs a page called “I’d like to be part of the Monsieur Hulot universe, if only as a cardboard cut-out”, and I think she speaks for many of us. (She also runs a FB page on PlayTime–as she spells it. Many writers use Playtime, and I prefer Play Time.)

For those who love Tati, there is finally a new set of his complete works, restored and available in separate DVD and Blu-ray sets. The imposing big black box contains seven discs, each in its own cardboard fold-over holder, one for each of the features and one for the shorts. There are extras on each disc. The small book included with the set has a brief bio of Tati, information on the restoration of the films, and program notes.

There are various versions of some Tati films. The Mon Oncle disc includes both the French and English-dubbed versions. The Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot disc has the 1953 version and the 1978 restoration. Jour de fête, which Tati tried to make in color, has three versions: the 1949 release print, the 1964 one with selective color added, and the 1994 restoration of the color version Tati had had to abandon.

The print of Play Time, though visually beautiful, is altered by some tampering by the restorers. It originally contained passages of music over a dark screen at beginning and end. I described these moments in my essay, “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception” (published in 1988 in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis). Of the beginning I wrote:

The film begins with pre-credits music involving percussion; at a seemingly arbitrary point in this music, the bright credits shot of clouds fades suddenly in from the darkness. Already we encounter the sound track as a separate level from the image track–as something to which we should pay cloe attention in its own right. (Unfortunately, most of this music seems to have been edited out of the re-release print.) (p. 253)

(The darkness and music actually last about 10 seconds before the cloud shot.)

And the ending, which in the original has several minutes of music played over a black screen:

Play Time structures even our transference, at the end, of aesthetic perception to everyday existence, by continuing its theme music for several minutes after the images stop–so long that we are forced to get up and move about to this music. The film’s sound track becomes an accompaniment for our own actions, inviting us to perceive our surroundings as we have perceived the film. (p. 261)

(The actual timing is about one minute, though it seems longer when you’re sitting in a darkened theater and are used to leaving immediately at film’s end.)

This new disc includes the dark footage at the end and the music, but the credits for the restoration and video are superimposed throughout–quite a different experience than music accompanying darkness. The music over darkness is shortened at the beginning to about 3 seconds, with the logo of Les Films de Mon Oncle’s logo and a dedication to Sophie Tatischeff, Tati’s daughter.

All these superimposed credits alters Tati’s intentions considerably. He clearly meant for that concluding music to make us almost actors in his film and to carry over its defamiliarization of the fictional world into the real world. Without it, this cannot be considered the definitive version of Play Time. It may seem a small matter, but the original decision was completely reflected Tati’s distinctive style.

Fortunately the Criterion collection’s version retains the music over black at the end, as well as a different set of supplements. Completists will need to have both.

For many, Tati’s last feature, Parade, will be new. It’s not a M. Hulot film or even really a fiction film. It was made in Sweden and consists of a variety performance by musicians, singers, a magician, and so on, all MCed by Tati in propria persona. Between other acts, Tati performs some of his most famous pantomime bits, including a remarkable scene where, as a tennis player, he mimes part of the action as if caught by a slow-motion news camera. Tati also devised some little scenes to take place among the audience, which contains some of the same sort of cardboard cut-outs that first appeared in Play Time:

Parade was shot on video during live performances, but the acts were also staged in a studio in 35mm (see bottom). That’s the source of the inconsistent visual style, though it’s less apparent on video than when projected in 35mm on a large screen.

It’s a strange but enjoyable and even complex film, if one goes into it without expecting it to be like Tati’s others.

Very few will have seen all of Tati’s shorts. These fall into three periods.

Three of them are from the mid-1930s, brief comedies ranging from 16 to 24 minutes: On demande une brute, Gai Dimanche, and Soigne ton gauche. Tati was a young music-hall performer at the time, specializing in sports pantomimes.

Second, there is L’École des facteurs (1946), a 16-minute version of of the same story that he expanded into Jour de fête a few years later. L’École des facteurs was his directorial debut, the earlier shorts having been directed by others.

And third, Tati made some shorts late in his career: Cours du soir (directed by Nicolas Ribowski), Degustation maison, and Forza Bastia (the latter two directed by Tati’s daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, who used the original family name).

The set has optional English subtitles and is BD Region B.

On early Soviet cinema and much more

The title of Natascha Drubek’s new book, Russisches Licht: Von der Ikone zum frühen Sowjetischen Kino might seem to imply a narrow field of study. Actually, though, it ranges far, examining the introduction of electric lighting into Russia and examining what a wide range of Russian commentators wrote about light at the time. This includes, of course, the cinema, an art form both composed of light and using light during the filming.

The introductory section covers theoretical approaches to cinema, including the work of the Russian Formalists. Drubek goes on to consider factors in the early history of media in Russian and Soviet cinema, including writings on theaters and film censorship.

She then goes back to the roots of thought on light and media further back in Russian history, dealing with icons and the church, as well as the influence of icons on the Russian avant-garde of the pre-Revolutionary period. Finally she deals with cinema and in particular with the films of Evgenii Bauer.

I cannot claim to have read the book, for with my shaky knowledge of German it would be slow going. But it is an impressive achievement, and anyone interested in Russian/Soviet cinema and especially Bauer should have it. It is available online directly from the publisher.

Tati’s classic fishing routine in Parade.

The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks

Pulp Fiction (1994).

Trigger warning: This blog is about Quentin Tarantino, Walt Disney, and Henry James. Those who find violent analogies disturbing should avoid what follows.

DB here:

Every narrative film is made out of parts. Normally they just whisk by us, but sometimes our attention is called to them as parts. Occasionally, we sense that the whole movie is made out of large-scale chunks.

Take Pulp Fiction (1994). It consists of scenes grouped into larger blocks, some marked by fade-ins and outs and others with titles, like chapters in a book. The diner opening is set off as a unit before the credits. The ensuing visit of Jules and Vincent to the apartment of the welshing punks is ended in a fade-out. We then get a section tagged “Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife.” After that portion fades out, there follows a sequence introducing the young Butch as a boy, presented with his father’s gold watch. Then Butch, now grown up, heads out to the boxing match. Another fade, and we get a title, “The Gold Watch.”

That could be seen as simply a belated chapter head for the entire Butch section, boyhood and prizefighting career. Or it could mark the start of another, much longer block: the aftermath of the fight and Butch’s flight from Marcellus Wallace. Either way, the sense of a film composed of large-scale parts is very strong. As the film goes along, we realize that each block tends to concentrate on certain characters and provide distinct, sometimes overlapping, stretches of time.

For many viewers, I suspect, Pulp Fiction was their introduction to strategies of block construction in movies. Those of us studying film history had seen it in various guises before, but seldom so cleverly and explicitly worked out as in Tarantino’s film. And I’m not sure even film historians realized how much Tarantino owed to earlier traditions.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I suggested that some of the experimental trends in 1990s-2000s cinema were indebted to Hollywood in the 1940s. This is especially evident in the neo-noir films of those years, like The Underneath (1995), The Usual Suspects (1995), and Memento (2001). Now that I’m writing a book on that earlier period, I realize that studying the 1990s films, has led me to think about something that I hadn’t noticed—how interested 1940s filmmakers were in building movies out of blocks.

Turns out that the 1940s was a kind of golden age of block construction. And Tarantino serves especially well to illustrate how that strategy can be put to use in modern times. In fact, his work is a fairly comprehensive layout of the creative possibilities of the format.

Building blocks

Some basic options for block construction were laid out fairly early in the silent era. The most famous instance was Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), which sampled four historical periods, each harboring its own distinct story. He then crosscut the four epochs, building to four “simultaneous” climaxes at the end of the film. Griffith managed to secure an unprecedented level of suspense by alternating portions of his blocks.

Griffith also wanted to prove a conceptual point, that intolerance reappeared at different times in different guises. He understood one of the major attractions of block construction: It asks us to compare and contrast.

Griffith also wanted to prove a conceptual point, that intolerance reappeared at different times in different guises. He understood one of the major attractions of block construction: It asks us to compare and contrast.

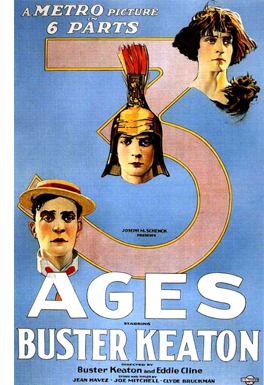

Directors who wanted to achieve the same comparison among different historical periods took the more obvious option and laid each separate story out, one after the other. We see the result in Dreyer’s Leaves from Satan’s Book (1920), Lang’s Der müde Tod (Destiny, 1921), and The Three Ages (1923), Buster Keaton’s parody of Intolerance. So this construction by integral blocks of time, laid end to end, was useful for comparing several self-contained stories.

Can you get the same sort of effect when sections of the same story are separated out in blocks? Yes, you can. The classic example would be parallel flashbacks. In Citizen Kane, an ongoing present, the reporter Thompson’s investigation, brackets long flashbacks that serve as parallel architectural parts—trips to the past, showing Kane as seen by others. We’re coaxed to compare Kane’s actions at different points in his life, as well as the various sides of him seen by his associates.

Here, as sometimes happens, the blocks are marked off not only by time period but by varying viewpoints. The alternation between the present and long stretches of the past, focused around one character and then another, characterizes many 1940s flashback films, such as The Killers (1947) and A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

Tarantino made alternating block construction the basic principle behind Reservoir Dogs (1992), which shuttles between the aftermath of a botched robbery and the planning that led up to it. One model he has acknowledged is Kubrick’s The Killing (1955), which itself transposed into cinema the overlapping point-of-view blocks that were present in Lionel White’s source novel Clean Break.

Elsewhere on the blog I’ve talked about how flashbacks can be nested inside one another, like Russian dolls. Examples from the 1940s include Passage to Marseille (1944) and The Locket (1946), and these lengthy sections surely count as blocks. Here the blocks serve less to compare dramatic situations than to fill in backstory. The blocks are lumps of exposition. In addition, blocks also can usefully delay events, creating suspense and padding the plot to its proper length. (Form often follows format.)

Tarantino embedded flashbacks within flashbacks in Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003) for just these purposes. Let’s assume that the early sequence (Chapter One) showing the Bride attacking and killing Vernita, her second victim, is a benchmark for the narrative present. That ends with her reading her list of targets. Chapter Two, which follows, initiates a flashback going back several years. In the course of that, the Bride escapes from the hospital and sets out to kill O-Ren, who’s her first victim. And in the course of that long flashback, framed by the Bride lying in the Pussy Mobile, we get a nested one, dubbed “Chapter Three: The Origin of O-Ren.” That eight-minute anime fills in the life story of the queen of the Tokyo underworld before we return to the Bride’s quest for her.

The anime sequence is closed off by a return to the Bride recovering in the Pussy Mobile.

The flashback-within-a-flashback supplies exposition, creates a parallel to what we’ve seen at the film’s start (Vernita’s little daughter discovering the Bride’s murder of her mother), and sharpens our curiosity about the Bride’s trip to Japan. We stay in that Japan-related flashback for the rest of Vol. 1. The plot won’t take us back to the present, after the Bride’s killing of Vernita, until the black-and-white beginning of Vol. 2.

A trickier Chinese-boxes structure appears in Reservoir Dogs. The present-time situation is the gathering of the surviving hoods in the warehouse. There are flashbacks to the planning stages of the holdup, each attached to one man’s viewpoint and tagged with his alias.

In the flashback attributed to Mr. Orange, the police mole, we start with him identifying himself to the tortured cop in the warehouse. We move to the past, when Mr. Orange meets a contact in a diner and explains that the gang took him in. That leads to a nested flashback showing him at his audition.

To gain the gang’s trust, Mr. Orange tells a heavily rehearsed fake anecdote about evading the cops during a drug swap. And even that gets an embedding: the false anecdote is presented visually, as a scene in a men’s toilet.

Then we come out of the nested flashbacks in proper order: back to the meeting with the gang, then to the diner, and several scenes later, back to the present situation in the warehouse.

A lying flashback is embedded in a flashback that’s itself embedded within a flashback. The whole shebang becomes a complex block labeled “Mr. Orange.”

Most flashback films use the trips to the past to revisit characters known to us in the present. But some films use the flashback option to tell independent stories. Forever and a Day (1943) is a biography of a house, supplying a history of the house from its origins to its sufferings during the Nazi bombing of London. An even clearer example is Tales of Manhattan (1943). It traces how a coat of tails is passed down the social pecking order, from an elegant actor to a sharecropping community. No characters tie the episodes together, only the coat and some thematic motifs. Again, the blocks encourage us to contrast how different social classes use the tailcoat.

I don’t find Tarantino picking up this circulating-object idea, but it has been reused in Twenty Bucks (1993), American Gun (2006), and other films. Somewhat in the same spirit, though, is Tarantino’s Death Proof, the second feature in Grindhouse (2007). The first half of the original theatrical release concerns four young women who are targeted by Stuntman Mike, a free-range master of vehicular homicide. All the women are killed, but in the second half Mike meets his match in a quartet of car-crazy film staffers, one of whom is a stuntwoman while another is an expert driver. Mike is like the coat of tails in Tales of Manhattan: the only link between the film’s episodes.

Flashbacks can, of course, be much briefer, and when they are they don’t usually have the heft of blocks. But when a scene is replayed as a flashback, both the replay and the original scene can stand out. The flashback replay of the murder of Monty in Mildred Pierce (1945) gains a certain solidity, since it reveals things that were suppressed (and fudged) in the first go-round. (Go here for the entry and the analytical video discussing these scenes.) Another example is the conflicting testimony that includes a lying flashback in Crossfire (1947).

Pushing beyond his predecessors, Tarantino tries a more elaborate replay in Jackie Brown (1997). He presents the shopping-mall money exchange three times, from different characters’ attached viewpoints. The side-by-side replays make the whole money drop stand out as a block, as does the chapter title (“Money Exchange: For Real This Time”) and the length (over twenty minutes). A practice session for the exchange forms a parallel block, with its own introductory title (“Money Exchange: Trial Run”).

Episodic memories

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

If flashbacks, played once or many times, provide the most common sorts of blocks, big or small, there are other possibilities. You can, for instance, build your plot out of chronological but independent blocks within the same locale and time frame. Three Strangers (1946) is a straightforward example.

A woman invites two men into her apartment and suggests they share the price of a sweepstakes ticket. They will then reunite on the day the ticket falls due to see if they’ve won. After the men agree, the plot follows all three separately, with long blocks devoted to each. Their stories don’t intersect. There is a little bit of crosscutting among them, but the characters don’t reunite until the climax.

The advantage of this diverging-reconverging construction is that you can tell several stories, each with its own dramatic arc, within a larger frame that brings them all to a decisive conclusion. If you pull it off, it can deepen characterization (we spend more time with the protagonists) and perhaps mark you as a virtuoso. A flashy example is Mystery Train (1989), which provides the moment of the story lines’ convergence as a sound rather than a face-to-face encounter.

The risk of this format is that some separate stories may seem less interesting than the others. An ordinary film moves along quickly enough that we can wait out tiresome characters or situations, but in this construction we’re stuck for a while. This cost-benefit analysis may be one reason that most Hollywood plots try to integrate their story lines fairly tightly. That way you can keep the audience aware that each scene has consequences for everything that follows.

Tarantino uses the parallel block device in Inglourious Basterds (2009). Here two main story strands—Shosanna’s efforts to elude Colonel Landa and the mission of Aldo Raine’s combat team—develop independently in lengthy scenes. There’s some alternation, but the plot lines don’t converge until the movie theatre conflagration. Interestingly, both Three Strangers and Inglourious Basterds fill out their dimensions by including minor subplots (the adventure of Archie Hicox developing its own interest in Basterds).

The simplest version of block construction lets one distinct story episode follow another. The most common case is the Hollywood musical, which contains numbers, either as stage performances or as sung-and-danced scenes. Each number tends to have an internal coherence and sharp boundaries that make it a detachable unit. (So detachable that it can stand on its own in documentaries like That’s Entertainment! of 1974 and its sequels.)

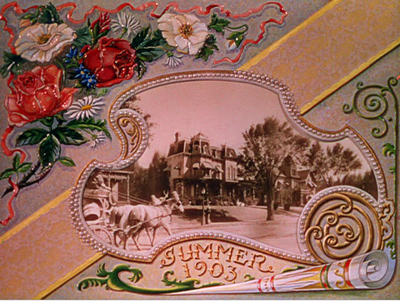

One musical that includes larger-scale segments—quite big blocks,, actually–is Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). The plot consumes about a year in the life of a family, and it opens with a candy-box title card specifying “Summer 1903.” It’s followed by two more seasonal chapters, identifying autumn and winter of the year, before we get “Spring”—a title with no date, suggesting a kind of eternal renewal that will solve the characters’ problems. Within each of these blocks, events typical of each season, including Halloween and Christmas, reinforce the sense of these as varied sections.

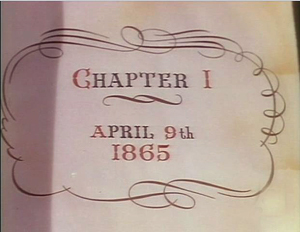

This sort of explicit chaptering in the 1930s-1940s is usually reserved for films framed by opening pages of a book, as in Salome, Where She Danced (1945).

Often, as in Salome, the book frame is dropped from the rest of the movie, although it might reappear to provide closure.

New forms of self-conscious chaptering became prominent in later years, as with the quotations announcing sections in Hannah and Her Sisters (1985). Most of Tarantino’s films use chapter titles to some extent, with the Kill Bill movies providing the most elaborate examples. Those films are presented as two “volumes” containing ten distinct “chapters.” Some are bulked out by flashbacks, some aren’t, but all these chapters become prominent through sheer length. Chapter Nine, which settles the fates of both Budd and Elle Driver, runs almost half an hour, and the final chapter lasts over forty minutes.

Moreover, the chapters, as in Pulp Fiction, aren’t arranged in 1-2-3 order, so we’re invited not only to compare parts but figure out their chronology. The very first chapter teases us with this problem.

The circled 2 is explained when we understand that Vernita is the second target on the Bride’s list.

Still other forms of big-chunk construction came into prominence in the 1940s. Think for instance of what were called “episodic” films, movies that inserted separate stories, often thematically connected, into a general framing structure. For example, the team that gave us Tales of Manhattan also produced Flesh and Fantasy (1943). The situation is of two men discussing superstition in a library. One takes down a book of stories and we see, enacted, three tales of the fantastic. At the end we return to the library.

This cinematic anthology was sometimes called an omnibus film, and it proved very popular around the world; examples are Dead of Night (UK, 1945) and the many Italian and French collections (e.g., The Seven Deadly Sins, 1952; Spirits of the Dead, 1968). It persisted for decades in the US (New York Stories, 1989; Night on Earth, 1992) and internationally (Paris, je t’aime, 2006). Tarantino’s contribution to the genre was Four Rooms (1995). The framing situation is that of a hotel, and three other directors contributed episodes showing what happens to various guests.

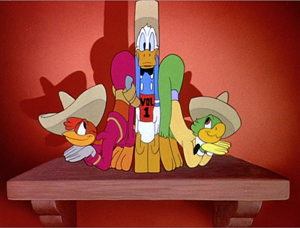

Walt Disney exploited block construction in all these ways during the 1940s. He filled out a live-action film with embedded stories (Song of the South, 1946) and interspersed cartoons with travelogue footage (Saludos Amigos, 1942). The all-animated Three Caballeros (1944; above) assembled several South American tales by means of a frame story showing Donald Duck getting gifts from below the border and dancing with his amigos. (This is a brilliant movie, as I suggest in this ancient but ageless post.)

By contrast, Make Mine Music (1946) and Melody Time (1948) give their animated musical numbers only minimal framing.

Most famous of the Disney anthologies, of course, is Fantasia (1941). Here a program of classical pieces is illustrated in cartoon sequences. The frame is provided by Leopold Stokowski at the podium and Deems Taylor, a famous music popularizer, supplying radio-style commentary in the breaks. Strange though it sounds, Tarantino (along with Robert Rodriguez) does something similar when he gives us two exploitation features, Planet Terror and Death Proof, surrounded by trailers and ads. Just as Disney posits a mock trip to the concert hall, Tarantino reimagines a night at a drive-in or an inner-city movie house.

What about Django Unchained (2012)? I think Tarantino has done something clever here. At what seems to be the climax, Dr. Schultz is killed and Django, after a fierce gunfight, is recaptured and sold to slave traders. The drama seems to be finished. But then the movie starts over, and a twenty-five-minute stretch of new action shows Django escaping the traders and returning to Candyland to wreak his revenge. Tarantino has tacked on a second, lengthy ending; block structure yields a calculated anticlimax.

Modern, middlebrow, mysterious

I guess what I’m always trying to do is use the structures that I see in novels and apply them to cinema.

Quentin Tarantino, 1993

Where did the 1940s impulse toward block construction come from? In classical Hollywood cinema, I see two primary literary sources: modernism and its offshoots in “mild modernism” (what Dwight Macdonald called “midcult”); and mystery fiction.

Fictional tales had long been broken into segments, and chapter divisions are of course very old. Assembling tales out of blocks likewise has antecedents as far back as ancient Egypt, Homer, and the Bible. Epistolary and found-manuscript fiction gravitated naturally to block arrangement. Dickens gave Little Dorrit (1855-1857) a balanced two-part layout, and he built Bleak House (1852-1853) on alternating segments in two narrative voices.

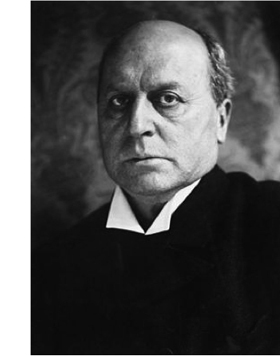

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers reflected on such problems of carpentry. Here is Henry James on carefully dividing The Wings of the Dove into discrete sections. (The italics are his.)

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers reflected on such problems of carpentry. Here is Henry James on carefully dividing The Wings of the Dove into discrete sections. (The italics are his.)

There was the ‘fun’ . . . [of treating the actions as] sufficiently solid blocks of wrought material, squared to the sharp edge, as to have weight and mass and carrying power; to make for construction, that is, to conduce to effect and to provide for beauty.

Likewise, The Awkward Age (1899) was conceived as a situation to be illuminated by different characters, or “lamps,” each participating in a single social occasion. Consequently the contents as a series of chapters (or “books”) with character titles (not unlike what Tarantino did in Reservoir Dogs): “Lady Julia,” “Little Aggie,” “Mr. Longdon,” and so on.

This sort of explicit geometry was sometimes taken up by modernist writers. Faulkner breaks The Sound and the Fury (1929) into large parts determined by place, time, and character narrators. John Dos Passos intercuts chunks of different sorts of texts (news stories, “camera-eye” views) to create the trilogy USA (1930-1036). Other modernists avoided tagging sections but made sure to give each one a blocklike singularity, as Joyce famously does with the chapters of Ulysses. Each one is keyed to a section of Homer’s Odyssey, a time of day, a symbol, and so on, and treated in a different literary technique.

Middlebrow writers, who tried to make modernism more user-friendly, seized on block construction. A prime example is Thornton Wilder’s Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927), which traces three parallel stories of people who died on the bridge when it collapsed. Less famous is Rex Stout’s fascinating How Like a God (1929), which alternates two sorts of blocks: one in italics, past tense, third-person narration, and labeled with letters of the alphabet; a second in roman type, present tense, second person (“You…”), and given a numerical order. The labels and fonts help us figure out the chronology of the story (and grasp the thoughts of the main character). Kenneth Fearing’s mildly modernist novel The Hospital (1938) borrowed from Dos Passos in shifting viewpoints among many characters, even objects, and his Clark Gifford’s Body (1942) anticipates Pulp Fiction in drastically shuffling discrete blocks out of story order.

At a more popular level, mystery fiction developed its own strategies for block construction. As a genre, mystery and detective stories are dedicated to formal play with narrative options. (Hence their interest for us narratologists.) Mysteries are frankly artificial, even gamelike, and so seek out ways to trick us.

The love of artifice often yields embedded stories, as in A Study in Scarlet (1887), and plays with point of view (famously, Christie’s Murder of Roger Ackroyd, 1926). While Dickens and James were testing block construction in the “serious” novel, Wilkie Collins was developing the “casebook” format: a collection of documents—letters, testimony, discovered manuscripts—that served as a series of blocks. Dracula (1897) also helped popularize the format. It was revived in Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace’s The Documents in the Case (1930) and Perceval Wilde’s Design for Murder (1941). And just as Stout had made typography and chapter headings formal devices, so did mystery writers use them to build suspense and their readers (e.g., Anita Boutell, Death Has a Past, 1939).

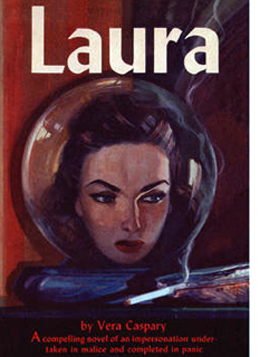

We tend to take such trickery as typical of the sleuth-and-puzzle detective tradition, but not of the hard-boiled detective tales and suspense thrillers we associate with the 1930s and 1940s. Yet writers in those traditions sometimes shift a story forward and backward in big blocks, as with Don Tracy’s Criss Cross (1934, source of the 1949 film). Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) exploited the casebook format, which was partly transposed into the film version. Kenneth Fearing, trying his hand at mystery fiction, shifted first-person narration among several characters (including a dead one) in Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946). Bill S. Ballinger’s Portrait in Smoke (1950) paralleled a first-person account of an investigation with third-person chapters that trace what happened in the past.

We tend to take such trickery as typical of the sleuth-and-puzzle detective tradition, but not of the hard-boiled detective tales and suspense thrillers we associate with the 1930s and 1940s. Yet writers in those traditions sometimes shift a story forward and backward in big blocks, as with Don Tracy’s Criss Cross (1934, source of the 1949 film). Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) exploited the casebook format, which was partly transposed into the film version. Kenneth Fearing, trying his hand at mystery fiction, shifted first-person narration among several characters (including a dead one) in Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946). Bill S. Ballinger’s Portrait in Smoke (1950) paralleled a first-person account of an investigation with third-person chapters that trace what happened in the past.

Trends in high, middlebrow, and “low” literature like crime stories had a large impact on 1940s cinema. Just as important, this formal play with narrative conventions, including block construction, continued for decades, right up to the present. Most pertinent to Tarantino is the trend toward rigorous construction we find in crime fiction from the 1960s onward.

My own favorite example is Richard Stark (aka Donald Westlake), who conceives nearly all his novels in a rigid four-part format. Tarantino seems to prefer Elmore Leonard and Charles Willeford. He isn’t given as much credit for his bibliophilia as his cinephilia, but it’s evident that he has thought a fair amount about how to bring literary techniques into cinema.

Novels go back and forth all the time. You read a story about a guy who’s doing something or in some situation and, all of a sudden, chapter five comes and it takes Henry, one of the guys, and it shows you seven years ago, where he was seven years ago and how he came to be and then like, boom, the next chapter, boom, you’re back in the flow of the action.

For example, in Rum Punch, the source novel for Jackie Brown, Leonard’s chapter-breaks usually shift our attachment from one character to another, and the new chapter may insert backstory at the start. Leaving Jackie Brown’s deal with the Feds hanging, Chapter 14 starts with Melanie sunbathing and thinking about her past. A chunk of exposition, like a film flashback, explains how she became “the tan blond California girl.” Tarantino was unusually sensitive to fiction writers’ switches in time and viewpoint, and he clearly admired the opportunities opened up by solid chapter-length blocks.

I’m not suggesting that Tarantino spends his weekends perusing Henry James or Thornton Wilder. It’s just that techniques similar to theirs have pervaded popular literature. Indeed, they were already at play in one popular genre that has always used literary artifice to shape our experience. To this day, as in King’s 11/22/63, mysteries and thrillers use block construction to promote suspense, play with alternative possibilities, make us reevaluate story situations, and engage us in a game of self-conscious form.

Sometimes current developments put the past in a new perspective. The emergence of “minimal music” (Glass, Reich, La Monte Young) suddenly showed Satie’s ideas about repetition to be more fertile than most of us had thought. Similarly, Tarantino’s work forced me to think about contemporary storytelling strategies, but it also asked me to consider more distant sources of those trends.

Studying film history is valuable for its own sake; it’s just damn interesting. Needing further justification, sometimes historians go on to say, especially to students: We study history to better understand the present. That’s surely true, but so is this: We study the present to better understand history.

Henry James’ discussion of block construction is in “Preface to The Wings of the Dove” in The Art of the Novel: Critical Prefaces (New York: Scribners, 1934), 296. Tarantino’s comments about novels and films come from Graham Fuller, “Answers First, Questions Later,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 53; Jeff Dawson, Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (Applause, 1995), 69.

A useful discussion of how chapter divisions relate to plot is Philip Stevick, “The Theory of Fictional Chapters,” in The Theory of the Novel, ed. Stevick (The Free Press, 1967), 171-184. You can sample it here.

Neo-noir encouraged many filmmakers to explore block construction. Three quick examples: Soderbergh in Out of Sight (1998; from a Leonard book), Christopher Nolan in Following (1998), and Shane Black in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005, which split up into chapters corresponding to one popular screenplay formula). Nolan proved keenly interested in this compositional approach; see our ebook, Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. More recently, Wes Anderson’s films deploy some tricky versions of block construction.

Block construction is also apparent in comic books, and Tarantino is clearly an aficionado of those traditions too. That influence should be taken into account for a fuller analysis of his narrative techniques. Also, too: The influence of Godard, especially in the “tardy” title insertions coming after the segment has started (e.g., one way to take “The Gold Watch”).

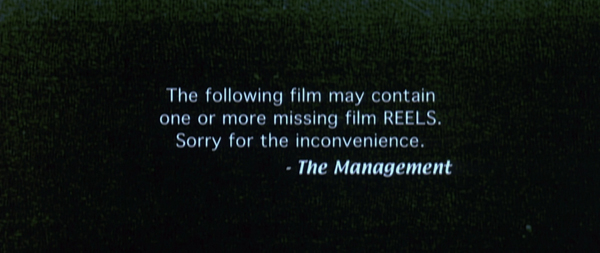

The expanded, stand-alone feature version of Death Proof displays block construction in filling out the “missing reel” portion of the first story and creating a new block, a ten-minute scene of the second “girl posse” at a convenience store. The scene starts with Stuntman Mike before shifting to the young women. It makes Mike even more a connecting link between the film’s two episodes, while Mike’s stalking and spying fulfills Tarantino’s claim that Death Proof is a slasher movie.

Embedded stories or flashbacks exemplify what researchers call “ring construction.” Bill Benzon has explored this in many critical analyses, as here with the 1954 Godzilla/Gojira.

For more on Inglourious Basterds, see our entry here and as revised in Minding Movies. We analyze the money-drop sequence in Jackie Brown in Chapter 7 of Film Art: An Introduction. Kristin discusses the titles and segmentation of Hannah and Her Sisters in Chapter 11 of Storytelling in the New Hollywood.

Thanks to participants in the 2014 conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image for their comments on some of the ideas presented here. Thanks also to Matthew Bernstein, biographer of Walter Wanger, for in-depth discussion of Salome, Where She Danced.

Grindhouse (2007).