Archive for the 'Directors: Johnnie To Kei-fung' Category

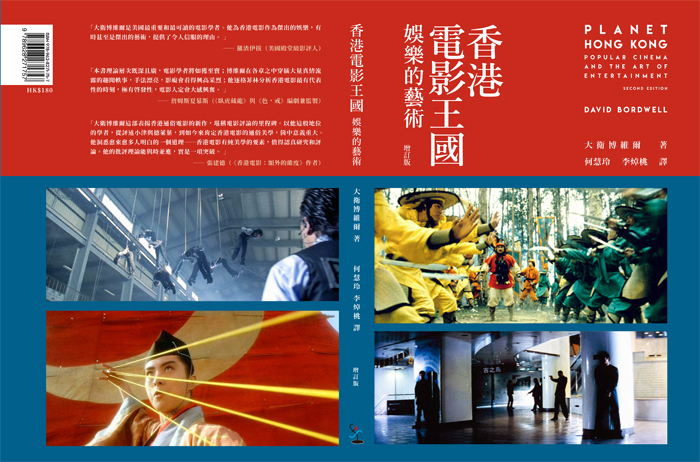

PLANET HONG KONG comes to . . . Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Film Critics Society has just published a Chinese long-form translation of the second edition of my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It can be ordered from the HKFCS bookshop. Sample pages and further information can be found here. I’m grateful to Li Cheuk To, Alvin Tse, and their colleagues for preparing and checking the text and finding nice pictures.

That second English-language edition dates back to 2011–a distant past in terms of the rapid changes in world cinema. So for this translation, I wrote a postscript last year, and at the suggestion of Cheuk To I’m posting it here. The book is dedicated to Ho Waileng.

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

Raymond Chow Man-Wai and Louis Cha Jin Yong both died in 2018. Journalists seeking a strong hook might take these unhappy departures as emblematic of changes in Hong Kong film culture—marking the “end of an era,” as we say. But Chow retired from the scene in 2007, and Cha finished revising his classics at about the same time. They stand, of course, as towering figures in Chinese cinema, but from my perspective today’s Hong Kong film is for the most part continuing processes that started quite far back. In other words, and much to my regret, the golden era ended some time ago.

I wrote the first edition of Planet Hong Kong in the late 1990s. As I explain in the book, I had been watching some Hong Kong films since the 1970s and got interested in the 1980s creative developments. By 1995, when I first visited the territory, those developments were already fading, though that wasn’t obvious to me. The local market was becoming unstable, regional tastes and investment sources were shifting, and the mainland economy was expanding. That age, undeniably golden, was ending.

When I interviewed local executives for the book, some said that they thought Hong Kong could become the “Hollywood of China.” Perhaps, they thought, all the experienced talents and financial and technical resources of the territory would be much sought after as China opened up its market.

By the time I came to revise the book in the early 2000s, such idealism had waned. As you’ll see in the pages that follow, it became obvious that Chinese authorities had shrewdly manipulated the market and the infrastructure to build up a powerful domestic industry. The rise of that industry, along with the waning of Hong Kong film, led to the biggest growth of a national film business ever seen in history. And those processes would assimilate Hong Kong creative talent on the mainland’s terms.

Now, as the 2010s come to an end, it seems that all the trends that I traced in the 2011 edition have continued, even accelerated. From 263.8 million viewers in 2010, mainland attendance has risen to over 1.6 billion in 2017. In 2010, the mainland claimed theatrical revenue of US$1.5 billion; in 2017 those were $8.27 billion. According to official figures, 970 feature films were produced in 2017. Although most of those were not released theatrically, it still remains a colossal achievement.

Over the same period, Hong Kong cinema continued in stasis. Production hovered between 42 and 64 annual releases. Theatrical admissions were likewise fairly flat, at an average of 25 million a year. Box-office revenues in 2010 came to US$179.4 million, and moved to $237.9 million in 2017. This is a substantial increase, but rising ticket prices (seen in every film culture) is likely one cause. Part of the rise, which occurred in the mid-2000s, is probably due to the emergence of 3D exhibition, which yields premium ticket pricing. And the greater part of that box office did not accrue to local films.

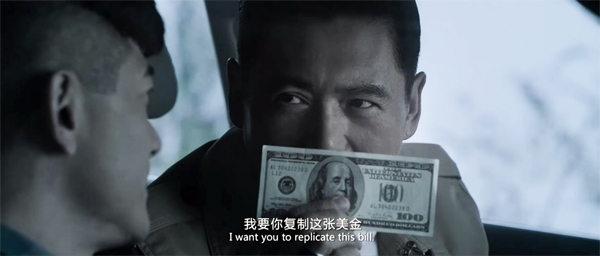

Certainly Hong Kong professionals at all levels were important resources for the growing mainland industry. Stars were and still are sought for major roles, and figures from decades ago, such as Chow Yun-fat, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Shu Qi, and Andy Lau Tak-wah, can still draw audiences. Directors Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, Stephen Chow Sing-chee, Peter Chan Ho-sun, Chang Pou-soi, Wong Jing, Johnnie To Kei-fung, and Stanley Tong Gwai-Lai found success in China, mostly with coproductions. The biggest coup of the era, Wolf Warrior 2 (2017; above) with its 154 million admissions, came from Wu Jing, a veteran actor and martial artist in Hong Kong films. Just as important, Edko, Emperor Motion Picture Group, and other local companies gained from producing movies for the mainland audience.

More broadly, the mainland box office was keeping Hong Kong film alive. A “local” film was likely to have mainland investment, and when it played there it had a good chance of making much more money than at home. SPL 2: A Time for Consequences (2015) took in less than US$2 million in Hong Kong but won over $90 million in China. Wong Jing’s From Vegas to Macau 2 of the same year captured $154 million there, as opposed to $3.6 million in Hong Kong. Through the 2010s, even a moderate success on the mainland could recoup far more money than it could in the tiny local market. To some extent the growing market to the north replaced the regional South Asian market that had sustained Hong Kong film in earlier decades. (How that market was lost is traced in Chapter 3.)

China cultivated homegrown directors as well, especially those who adapted conventions of Hong Kong and South Korean romantic drama and comedy to the local milieu. For any year, then, the top twenty films at the Chinese box office typically consisted of a mix. There would be imports (nearly all from Hollywood), domestic films by prestige directors (Zhang Yimou, Feng Xiaogang et al.), local genre films by younger hands, and two or three big box-office attractions steered by Hong Kong directors.

Coproductions that found mega-success in China didn’t register as strongly in Hong Kong. Tsui’s Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2011), Jackie Chan’s CZ12 (2012), Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China (2013), Raman Hui’s Monster Hunt (2015), and Tsui’s Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2017) all failed to crack the local top ten. Stephen Chow seems to have lost his hometown following: Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (2013) failed to score big there, while The Mermaid (2016) did, but in seventh place, below Marvel superheroes and the local thriller Cold War 2.

Not that the territory’s audience was particularly loyal to locally-sourced product either. The waning attendance I noted in Chapter 10 persisted. For the period 2010 to 2018, no more than two local films won a place in any year’s top ten. For three of those years, none did. In 2018, Project Gutenberg ranked number 12, the only local film to appear among the top thirty contenders.

Granted, in most countries, especially small ones, domestic films don’t get big box-office returns. Hollywood films dominate, with only one or two local productions finding a place on the year’s top ten. Still, those of us who remember when Hong Kong films ruled the local market have to see the stagnation as saddening. Nonetheless, with China offering many more opportunities for investment and rewards, it’s remarkable that there remains a local industry at all—and one turning out four or five dozen features a year.

Those films have tended to follow the templates established decades ago: romantic comedies, domestic dramas, films of social comment, and urban action pictures. Filmmakers have updated those genres with digital production and mostly skillful use of modern technologies of color control, computer effects, and elaborate camera movements, including the use of drones for aerial shots. But anyone familiar with classic Hong Kong film will recognize the persistence of traditional plots and story premises. Golden Job (2018) brings back the rascals from the Young and Dangerous series to execute a heist, under circumstances that strain their brotherhood. Project Gutenberg (2018) revisits the Chow Yun-fat mythos with a counterfeiting story (shades of A Better Tomorrow) that allows him to wear white suits, brandish guns in both fists, and participate in a twisty plot that owes something to the 1990s narrative stratagems I discuss in Chapter 9.

The continuity should hardly be surprising, because a great many veteran creators are still active. Producer Raymond Wong Pak-ming, who co-founded Cinema City and went on to create Mandarin Films and Pegasus Motion Pictures, continues to release films. Yuen Woo-ping was a choreographer and director in the 1970s and achieved worldwide fame with The Matrix (1999) and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000); he recently directed Master Z: The Ip Man Legacy (2018). Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, and many other directors from the 1970s remain top figures in a film culture that offers many opportunities to venerated talents.

Although I’ve long admired Hong Kong films in many genres, readers of of Planet Hong Kong know that I believe that the action film—as wuxia pian, kung-fu movie, or cops-and-robbers thriller—was the area of its most long-lasting contribution. The tradition of powerful physical action, gracefully executed and forcefully staged and cut, was a genuine contribution to the history of film as an art form.

For that reason it’s a pleasure to report that the “ordinary” action pictures of the last decade have by and large maintained that tradition. Donnie Yen Ji-dan, an actor who chooses intelligent projects, endowed films like Kung Fu Jungle (2014), the Ip Man vehicles (2008-2019), and Chasing the Dragon (2017) with vivid, exciting sequences. He and other filmmakers seem to have abandoned the looser camerawork of the early 2000s and returned to precision shooting: fixed camera, instantly legible compositions, and a flow of movement across shots that can accelerate, slow, or halt, all in the service of impact on the viewer.

Still, in the hands of a skillful craftsman any technique can work. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s White Storm (2013), a full-bore male melodrama in the John Woo manner, mixes run-and-gun handheld style with a revival of the forceful compositions and crisp editing of the heroic-bloodshed days. Cheang Pou-soi’s Motorway (2012) invests a simple plot with excitement through nearly abstract shots of cars gliding through streets and alleys, augmented by stretches of ominous silence.

Similarly, I see the positive legacy of the Infernal Affairs series (2002-2003) in franchises like Overheard (2009-2014) and Cold War (2012, 2016). While not as tightly contained as the trilogy, these films benefit from plotting that is less episodic and more finely woven than we find in the policiers of the 1980s. They also judiciously insert florid action sequences, creating a sort of middle ground between the bureaucratic intrigue of Infernal Affairs and the more extroverted spectacle of something like Police Story (1985)—or, come to think of it, any of Jackie Chan’s Police Story titles.

There’s much to be said about Tsui Hark’s PRC adventure sagas as well, particularly in their use of 3D. (The Taking of Tiger Mountain, 2014 above, is a mind-bending use of that technology.) But for my purposes here I’d like to focus on two other major talents that I analyzed in the second edition. Both made outstanding contributions to the action picture in the years since the second edition was published.

Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (2013), despite being circulated in varying versions, remains for me a powerful achievement. It carries on Wong’s persistent experimentation with decentered narrative, following not only Master Ip Man but also his chief rival Razor and Gong Er, daughter of Ip’s one-time adversary. As I suggest in a blog entry this diffuse treatment of the major characters may bear the traces of a multiple-protagonist plot reminiscent of Days of Being Wild. In addition, through strategic flashbacks and shifts from character to character, this “chaptered” film evokes the interrupted and embedded story lines of other Wong films.

Stylistically, The Grandmaster makes fresh use of distended time and slow-motion imagery; these are conventions of the kung-fu genre as well as a signature of Wong’s work. More unusual is what I call in the blog entry the “mosaic” texture he builds up through close-ups that can be put in various places in one scene or another, or even one version or another. In general, I think that Wong alters the thematics of the martial-arts film by emphasizing Gong Er’s tragic dilemma: defeating the man who killed her father both sustains and erases her family’s legacy. And, as we might expect with Wong, the film strikingly parallels martial-arts prowess with impulses toward romantic love.

Another major film of 2013, Johnnie To Kei-Fung’s Drug War, is no less characteristic of its creator. (I analyze it in another blog entry.) A cat-and-mouse intrigue between crooks and cops, it depends heavily on our filling in gaps and reading characters’ minds. Police officer Zhang tries to penetrate a drug-smuggling outfit, and he devises a perfect To/Wai Ka-fai strategy: He sets up two meetings with two kingpins who don’t know each other. At each meeting Zhang impersonates the other guy. This game of shifting identities, of symmetry and doubling among roles, is a common narrative device of the Milkyway films, but in Drug War it’s given new urgency and a great deal of suspense. One economical shot brings the two unsuspecting gangsters together in the same frame as they leave and enter elevators.

At the same time, the informant Timmy is playing his own game—one that it may take a couple of viewings to decipher. As in The Mission (1999), many scenes of Drug War consist of men looking at each other, trying to divine hidden intentions—here, framed in the simplest possible shots, mere faces seen inside adjacent cars. Timmy’s eventual double-cross culminates in one of the cruelest shootouts to be found anywhere in To’s work; its bleakness recalls the end of Expect the Unexpected (1998). Throughout his career, To’s originality and craftsmanship in this rich genre have made him one of the great contemporary directors.

Wong completed only The Grandmaster in the years I’m considering, but To remained quite productive. Romancing in Thin Air (2011) and Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 2 (2013) returned to the mode of white-collar romance that Milkyway had made its own, while The Blind Detective (2013) combined that eccentric tone with an off-center cop premise recalling Mad Detective (2007). Life without Principle (2011; discussed in this entry) was a striking use of multiple-character plotting to make incisive points about the financial crisis.

Office (2015), an adaptation of Sylvia Chang’s popular play, was at once a flamboyant musical and an experiment in 3D. In Three (2016) To took up the challenge of a tightly circumscribed time and space, tracing the raid on a hospital ordered by a triad who’s there in police custody. Milkyway produced films by others, notably Motorway and Trivisa (2016), an opportunity for three first-time filmmakers to collaborate on a feature with three intersecting story lines. This last effort was in keeping with To’s dedication to creating programs and award competitions for newcomers to the industry. He remained one of Hong Kong’s most imaginative and tireless creators.

I should mention one more tendency, and it’s an encouraging one. Both editions of Planet Hong Kong pointed out that the Hong Kong people, contrary to the stereotype, actually cared a great deal about politics, especially after 1989. Recent years have seen a resurgence in films explicitly about activism in the territory. An early example is Matthew Tome’s documentary Lessons in Dissent (2014), a stirring account of struggles over educational policy and voting rights, featuring the most heroic 15-year-old I’ve ever seen. The 2014 Umbrella Revolution brought forth Evans Chan’s Raise the Umbrellas (2016) and Yellowing (2016; below) by Chan Tse Woon of Ying e chi There was also the ambitious speculative fiction Ten Years (2015), an ensemble of stories forecasting political repression in 2025. It’s very encouraging to see these efforts to insist on free speech and social criticism.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out how much classic Hong Kong film anticipated developments in Hollywood. The comic-book franchises that found new popularity with X-Men (2000) and Spider-Man (2002) and the Dark Knight trilogy (2005-2012) feature chivalric warriors with extraordinary fighting skills and weaponry. Like the knights-errant of wuxia fiction and film, these superheroes can leap high in the air and subdue villains with secret fighting techniques. Some, like Iron Man, have an equivalent of “palm power.”

Sometimes the American films have acknowledged their sources in Asian martial arts traditions, as when Batman trains as a ninja (Batman Begins, 2005) and Doctor Strange studies under a sifu in his 2016 film. The combat scenes, full of flips and somersaults, owe a great deal to the acrobatic traditions on display in Hong Kong cinema. If the result lacks the precision and visceral punch we find in classic Hong Kong films, it’s still worth noting that Westerners have learned that kung-fu, fights in mid-air, and elegant swordplay look cool on the screen. Hollywood should thank Hong Kong for helping invigorate the American action film.

A few words about what the original book tried to accomplish. At the most basic level, I wanted to understand Hong Kong cinema as an industry, an artistic tradition, and a cultural force. At the same time, I wanted to study it as an example of a popular cinema, one that developed strategies of storytelling and style and emotional appeal that were accessible to millions of people around the world. I wanted to analyze its unique contributions to the development of film art, so that meant I had to do some comparative work, situating Hong Kong film in relation to other traditions—most notably, that of Hollywood. At another level, I was interested in particular genres, especially the action film, and directors. As a result, parts of the book—mostly the “interludes”—are devoted to a particular filmmaker or group of filmmakers. And while I expected that many readers would already be Hong Kong film fans, I wanted to persuade skeptical readers that this national cinema was worth respect. This overall project I tried to amplify in the second edition you’re now reading.

Since the last edition, I have not followed Hong Kong cinema as intensively as I would have liked. Other projects have diverted me. But I have never lost my admiration for this cinema, this culture, and this citizenry. Watching Hong Kong films and visiting the territory have added a new dimension to my life.

From my first stay in 1995, when Li Cheuk-to introduced himself to me during the festival, through many visits over the decades, I have always treasured my friends there. So many people helped me in my research—people attached to the festival, to the archive, to the industry—that to list them all would add too much to this already overlong postscript. But they are mentioned throughout the book, and I hope they know how much I appreciate their generosity over the years. I’ll be happy if anything I’ve done here and elsewhere, in other writing and teaching, have helped film lovers better appreciate the astonishing contributions of Hong Kong film to world cinema artistry.

Among those valued friends was the kind and dedicated Ho Waileng. A tireless worker for the festival, she also translated the first version of Planet Hong Kong into Chinese. She remains in the hearts of everyone who knew her.

P.S. 10 August 2020: We in the US are now accustomed to being shocked but not surprised. I woke up to learn that Jimmy Lai, maverick mogul and publisher of Apple Daily, and many of his colleagues were arrested under the new “national security” law. It’s ironic that President Trump, who has reportedly sought to jail our journalists, moved quickly to place sanctions on Hong Kong earlier this year. The latest crackdown may be a response to the U.S. condemnation of the bill’s restrictions on free speech. (I discussed them here.) An arrest warrant is out for an American citizen living in the U.S. because he advocates democracy for Hong Kong. A coalition of Democratic and Republican senators and representatives have sponsored legislation to widen refugee status for Hong Kongers. Another irony: It’s called the Hong Kong Safe Harbor Act.

Ho Waileng at Angkor Wat, 2006. Photo by Li Cheuk To.

Little stabs at happiness 4: Hitmen, with a side of sukiyaki

A Hero Never Dies (1998).

DB here:

Again, with apologies to Ken Jacobs, I offer another clip that pleases me in this long, hot summer. For earlier installments, go here, here, and here.

Johnnie To Kei-fung has been one of the leading Hong Kong directors since the 1990s. The first edition of my Planet Hong Kong (2000) wasn’t able to incorporate many mentions of his work, but that failing was remedied in my second edition, where he got several pages. Kristin and I first met him in fall of 2001, when Yuin Shan Ding arranged for us to visit the set of Running Out of Time 2. That was a memorable night, with the bike race shot in an elaborate false street wreathed in noirish city vapor.

We spent down time with the stars Ekin Cheng Yee-kin and Lau Ching-wan. It was the beginning of a long friendship with Shan, Mr. and Mrs. To, and the Milkway team.

Well before this, though, I had been teaching Mr. To’s films in my courses, and I much enjoyed showing–on 35mm, no less–A Hero Never Dies (1998). This flamboyant film, about two rival hitmen who unite against the gang bosses who have betrayed them, is a sort of post-John-Woo meditation on the costs of loyalty.

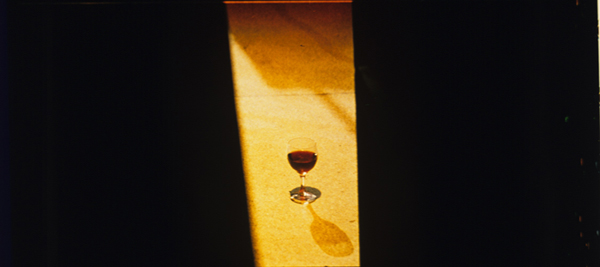

One sequence that usually got the students going was the men’s first up-close confrontation in a bar. Having struck out at each other long-distance, they rendezvous for a face-off–not over guns but over glasses of wine. The clip lacks subtitles, so I should explain that each man instructs the bartender to pour for the other one. Then, after Lau deploys his portion tactically, he refers to Lai’s wrecking his apartment: “This is for destroying my home.” There follows a tabletop action scene.

Shot and cut with great precision, timed to an infectious tune, it’s a model of mock-heroic filmmaking. Its brashness suits its swaggering protagonists, but it has a playground absurdity that evokes Leone. (Think of the hat-blasting gun duel in For a Few Dollars More.) The comedy is enhanced by Lau’s reaction shots and, as Kristin likes to point out, the heaviest coin in Hong Kong. One student told me: “When you’ve got a sequence like this, you’ve got a great national cinema.”

The result yields a pure kinetic pleasure, due partly to the coiling camera movements and the echoing rhythm of the cuts and gestures (ducking out of frame/rising into frame, finger flips/snorting smoke). Mr. To kindly took me through the sequence in an interview, and I learned that it was all shot in one night, after the bar had closed. It wasn’t storyboarded, but by this point Mr. To had all his shots and cuts in his head, and he and the actors developed the sequence as they filmed it.

It takes real pictorial intelligence, I think, to glide between concreteness and abstraction, onscreen and offscreen space, and each man’s optical viewpoint so suavely and zestfully. The camera plays peekaboo with the action.

As for the performances, Mr. To explained that Lau Ching-wan is such an extroverted actor that Leon Lai-ming could counter that bravado best by impassivity, returning his look at key moments. It’s an echo of what Howard Hawks told Montgomery Clift in facing off against John Wayne in Red River. Eventually it all settles into a calm, integrating long shot that declares a truce. What a pleasure to see a scene that actually buttons itself up visually.

And the song? Mr. To told me that the pop version of “Sukiyaki” (on the ambient soundtrack of my own teen years) was often played in theatres as pre-show music. “It always reminds me of movies.”

Thanks to Shan, Mr. and Mrs. To, To Kei-chi, and many other members of the Milkyway team. And to Li Cheuk-to, Athena Tsui, Jacob Wong, Sam Ho, and all the other HKIFF allies over the years. And continued hope for a strong Hong Kong!

We have many blog entries on Johnnie To and Milkyway.

Upper row, left to right: Lau Ching-wan, Yau Na-hoi, Johnnie To Kei-fung; bottom row, Ekin Cheng Yee-kin, DB, KT. Hong Kong, November 2001. Photo: Yuin shan Ding.

Genre ≠ Generic

The Shape of Night (Nakamuro Noboru, 1964).

DB here:

I didn’t plan it that way, but it turns out that a great many films I saw at this year’s Hong Kong International Film Festival would have to be categorized as genre pictures. Not, admittedly, Shu Kei’s episode of Beautiful 2014, which interweaves flashbacks and erotic reveries in a purely poetic fashion. And not Tsai Ming-liang’s “sequel” to Walker (2012, made for HKIFF), called, whimsically, Journey to the West. Here again, Lee Kang-sheng, robed as a Buddhist monk, steps slowly through landscapes, some so vast or opaque that you must play a sort of Where’s-Waldo game to find him. (You have plenty of time: there are only 14 shots in 53 minutes.)

But there were plenty of other films that counted as genre exercises. Yet they mixed their familiar features with local flavors and fresh treatment, reminding me that conventions can always be quickened by imaginative film artists.

Keeping the peace, in pieces

Black Coal, Thin Ice (2014).

Take, for instance, The Shape of Night, a 1966 street-crime movie from Shochiku, directed by Nakamura Noburo. Nakamura was the subject of a small retrospective at Tokyo’s FilmEx last year, and this item certainly makes one want to see more of his work. A more or less innocent girl falls in love with a yakuza, who forces her to become a prostitute. In abrupt, sometimes very brief flashbacks, she tells her life to a client who wants to rescue her. The film makes characteristically Japanese use of bold widescreen compositions, disjointed close-ups, and mixed voice-overs from her and the men in her life. In retrospect, everything we’ve seen has been seen in other movies, but Nakamura’s handling kept me continually gripped and often surprised.

Or take That Demon Within, a Hong Kong cop film that premiered at the festival’s close. Dante Lam has made several solid urban action pictures, especially Jiang Hu: The Triad Zone (2000), Beast Stalker (2008), Fire of Conscience (2010), and The Stool Pigeon (2010). They’re characterized by wild visuals and exceptionally brutal violence, and That Demon Within fits smoothly into his style. The new wrinkle is that a boy traumatized by the sight of police violence himself becomes a cop. He’s then haunted by the image of the cop from his past, while he’s also caught up in a search for a take-no-prisoners robber.

His hallucinations and disorientation are rendered through nearly every damn trick in the book, from upside-down shots and blurry color and focus to voices bouncing around the multichannel mix.

There are dreams, too (seems like almost every new film I saw had a dream sequence), and scenes under hypnosis, and men bursting into flame, and action sequences that are visceral in their shock value. I thought the movie careened out of control pretty early, and its nihilism wasn’t redeemed by an epilogue that assured us that this possessed policeman was, at moments, friendly and helpful. In this case, the storytelling innovations generated some confusion about exactly how the hero’s breakdown infused what was happening around him.

More consistent, largely because it didn’t try for the subjectivity of Lam’s film, was the Chinese cop movie Black Coal, Thin Ice. My friend Mike Walsh of Australia pointed out that the mainland cinema’s bleak realism seems to be starting to blend with traditional genre material. Director Diao Yinan explained, “My aim was not only to investigate a mystery and find out the truth about the people involved, but also to create a true representation of our new reality.” The opening crosscuts the grubby detail of bloody parcels churning through coal conveyors with a couple entwined in a final copulation before breaking off their relationship.

The mystery revolves around body parts that are showing up in coal shipments around one region. After a startling shootout in a hairdressing salon, the case remains unsolved for several years. The surviving detective, a shabby drunk, returns to track down the culprit, but in the meantime he runs into a frosty femme fatale. “He killed,” she says, “every man who loved me.” Needless to say, the detective falls for her too, especially after ice-skating with her. Diao’s film reminds us that you can create a neo-noir in two ways: By taking a mystery and dirtying it up, or taking concrete reality and probing the mysteries lurking in it.

There were even two Westerns. Another mainland movie, No Man’s Land, was unexpectedly savage coming from the director of the super-slick satires Crazy Stone (2006) and Crazy Racer (2009). Now Ning Hao has given us a bleakly farcical, Road-Warrior account of life on the Chinese prairie.

A wealthy lawyer brought out to the wasteland to negotiate a criminal case becomes embroiled in primal passions involving men with very large guns, very large trucks, impassive faces, and almost no sense of humor. It’s a black comedy of escalating payback (involving spitting and pissing), and it exudes sheer masculine nastiness. Completed four years ago, it found release only after extensive reshoots demanded by censors. Yet even in its milder state it remains true to the spirit of Sergio Leone’s jaunty grimness, bleached in umber sand and light.

Itching to see a Kurdish feminist political Western? You’ll find Hiner Saleem’s My Sweet Pepperland welcome. A tough policeman (= sheriff) is dispatched to a remote village in Kurdistan to keep order (= clean up the town). A young teacher (= schoolmarm) leaves her oppressive family to teach there as well. A warlord (= town boss) and his minions (= paid killers) have terrorized the locals, while marauding female guerillas (= outlaws) bring their fight into town.

These time-honored conventions shape a story of stubborn courage taking on complacent viciousness. In key scenes, our sheriff faces down big, hairy, scary killers.

USA frontier conventions, it turns out, work pretty well in a Muslim society too. The Hollywood Western’s continued embodiment of American values transfers easily to the former Iraq. “Our weapons are our honor,” the chief thug says, in a line that resonates through our history right up to now. Yet things we take for granted bring modern change to the wasteland. The sheriff assigns himself to the village in order to escape an arranged marriage, as the woman he finds there has done. She is vilified by both the locals and her male relatives, who would prefer death (hers) to dishonor (theirs). In the process, both he and she become heroic in a righteous, old-fashioned way.

A killer proposes a compromise while sneakily drawing his pistol. The cop shoots him and remarks: “I don’t do compromise.” Neither does My Sweet Pepperland.

Gangs of New York, and elsewhere

The Dreadnaught (1966).

From March to May, the Hong Kong Film Archive has been running a series, “Ways of the Underworld: Hong Kong Gangster Film as Genre.” It’s packed with classics (The Teahouse, To Be No. 1, City on Fire, Infernal Affairs) as well as several rarities (Absolute Monarch, Bald-Headed Betty, Lonely 15). I managed to catch three titles, all previously unknown to me.

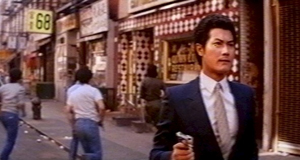

The Dreadnaught (1966) has a familiar premise. Two orphan boys indulge in petty theft after the war. One, Chow, is caught but gets adopted by a policeman. He turns out a solid young citizen. Lee, the boy who escapes, grows up to be a triad. When the two re-meet, Lee is attracted to Chow’s stepsister. Some years later, Chow is now a cop and vows to smash Lee’s gang. After a struggle with his conscience, Lee agrees to help.

The film’s main attraction is the shamelessly flashy performance of Patrick Tse Yin. Tse would make his fame in the following year in Lung Kong’s Story of a Discharged Prisoner, famous as a primary source for A Better Tomorrow. With his sidelong smile, his endlessly waving cigarette, and the dark glasses he wears at all times, Tse in The Dreadnaught looks forward to Chow Yun-fat’s charismatic role as Mark in Woo’s masterpiece.

Another icon of the period is Alan Tang Kwong-wing. He played in over 100 films, mostly romances and triad dramas made in Taiwan. Westerners probably know him best as the producer of Wong Kar-wai’s first two features, As Tears Go By and Days of Being Wild. Wong had worked as a screenwriter for Tang. Onscreen, Tang had a suave, polished presence marked by his perfect coiffure; he was known as the Alain Delon of Hong Kong. His company, Wing-Scope, specialized in mob films during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

New York Chinatown (1982) shows Tang as a young hood whose ambitions to dominate the neighborhood are blocked by a rival gang. Eventually the police decide to let the two gangs decimate each other. This leads to an enjoyable, all-out showdown involving surprisingly heavy armaments. Shot quickly on location (passersby sometimes glance into the lens), the movie gives a rawer sense of street life than you get from most Hollywood films. There’s also a scene in which Tang, apparently attending Columbia part time, corrects a history professor lecturing on Western imperialism in China. Although the film circulates on cheap DVD in 1.33 format, it’s a widescreen production, and it was a pleasure to watch a fine 35mm print at the Archive.

The biggest revelation of the series for me was Tradition (1955), a Mandarin release. This is considered one of the earliest pure gangster films in local cinema. It’s a fascinating plot about a boy raised by a triad kingpin in the 1930s. When the godfather dies, the young Xiang is given power over the gang and the master’s household. Trying to be faithful to the old man’s principles, Xiang finds himself unable to control his master’s widow and daughter, who are led astray by the widow’s worldly, greedy sister. At the same time, Xiang must ally with other triads to smuggle aid to the forces fighting the invading Japanese. He is torn between devotion to tradition and the need to adapt to modern materialism and the impending world war.

Tradition is redolent of film noir, not only in the sister-in-law’s fatal ways (she seduces the old master’s weak son) but also in the film’s flashback construction. Tracking back from a ticking clock, the movie begins with Xiang meeting the master’s daughter after his gang has been decimated in a shootout. The film skips back to Xiang’s childhood and takes us up through the main action before a final bloody confrontation with police and the corrupt family members. At the end, the camera tracks up to the clock, closing off the whole action.

Tradition is redolent of film noir, not only in the sister-in-law’s fatal ways (she seduces the old master’s weak son) but also in the film’s flashback construction. Tracking back from a ticking clock, the movie begins with Xiang meeting the master’s daughter after his gang has been decimated in a shootout. The film skips back to Xiang’s childhood and takes us up through the main action before a final bloody confrontation with police and the corrupt family members. At the end, the camera tracks up to the clock, closing off the whole action.

Even more tightly buckled up are director Tang Huang’s obsessive hooks between scenes. A final line of dialogue is answered or echoed by the first line of the next scene; a closing door or character gesture links sequences in the manner of Lang’s M. Most daringly, when sister San starts to light a cigarette in one scene, we cut to her puffing on it in a tight close-up—a gesture that takes place in a new scene hours later. This and other admittedly gimmicky links look forward to Resnais’s elliptical matches on action in Muriel.

Fortunately for us, the Archive has published Always in the Dark: A Study of Hong Kong Gangster Films. Edited and partly written by Po Fung, it is an excellent collection of essays and interviews. It is in Chinese, but it includes a CD-ROM version in English. It’s available from the Archive’s Publications office.

Behind the scenes at Milkyway

Johnnie To and a recalcitrant crane during the shooting of Romancing in Thin Air.

Sometimes a genre film becomes a prestige picture. This happened, in spades, with The Grandmaster. If awards matter, Wong Kar-wai’s film has become the official best Asian film of 2013. I missed the Asian Film Awards in Macau (was watching early Farhadi films), but the event was a virtual sweep: seven top awards for The Grandmaster, including Best Picture and Best Director. After I got back home, the Hong Kong Film Awards gave the picture a staggering twelve prizes, everything from Best Picture to Best Sound.

Unhappily, nothing in either contest went to the other outstanding Hong Kong film I saw last year, Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Drug War. It lacked the obvious ambitions and surface sheen of Wong’s film. Many probably took it as merely a solid, efficient genre picture. I believe it’s an innovative and subtle piece of storytelling, as I tried to show here.

Mr. To presses on, as prolific as usual. He has finished shooting a sequel to Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, a rom-com that found success in the Mainland, and he’s currently filming a more unusual project in Canton. More on that shortly.

During the festival only one recent To/Milkway film was screened, The Blind Detective (I wrote about that here). But Ferris Lin, a young director from the Academy for Performing Arts, presented a very informative documentary feature on To and his Milkyway company. Boundless takes us behind the scenes on several productions, particularly Life without Principle, Romancing in Thin Air, and Drug War. It also incorporates interviews with To, his collaborators, and critics like Shu Kei.

Sitting at the monitor with his cigar, To may seem distant, but actually he is wholly engaged. We see him help push a crane out of the mud and shout commands to his staff. To confesses that he may scold too much, but the dedicated cooperation he gets confirms his demands. The team gives its all, as we learn when they explain the tension ruling the three days of rehearsal for the sequence-shot at the start of Breaking News. For The Mission, made at the time of Milkyway’s biggest slump, the actors supplied their own cars and costumes.

To remains a complete professional who has perfected his craft, albeit in the Hong Kong tradition of “just do it.” He doesn’t rely on storyboards or even shot-lists, only outlines of the action, and he adjusts to the demands of the locations. The Mission had no script, but the entire story and shot layout were in his head. For Exiled, he didn’t even have that much and simply began thinking when he stepped onto the set each day. It’s hard to believe that precise shot design and sly dramatic undercurrents can emerge from such an apparently unplanned approach. In its recording of To’s unique creative process, Boundless provides a vivid portrait of one of the world’s finest contemporary directors.

To continues to challenge himself. He is currently trying something else again, shooting a musical wholly in the studio. Its source, the 2009 play Design for Living, was written by and for the timeless Sylvia Chang Ai-chia. It won success in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. In the film Sylvia is joined by Chow Yun-fat, thus reuniting the stars of To’s 1989 breakout film All About Ah-Long. The project also indulges the director’s long-felt admiration for Jacques Demy. There is no 2014 film I’m looking forward to more keenly.

Special thanks to Shu Kei and Ferris Lin of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts. Thanks as well to Li Cheuk-to, Roger Garcia, and Crystal Yau, as well as all the staff and interns of HKIFF, and to Winnie Fu of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Journey to the West (Tsai Ming-liang, 2014).

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

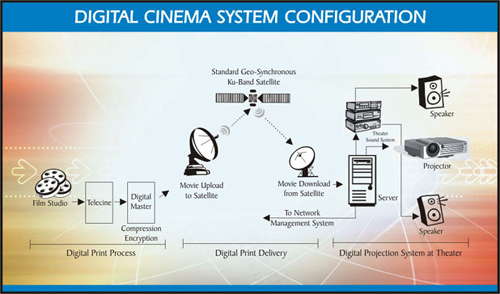

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

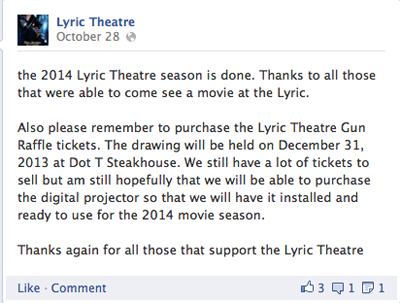

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.

Studios have incentives to shorten the windows, if only because a single promotional campaign can be kept going long enough for both theatrical and home release. In addition, buying or renting a movie with a couple of clicks encourages impulse purchasing, and the cost feels invisible until the credit-card bill comes. Nonetheless, commitment to day-and-date home delivery would be risky for the studios.

Hollywood is more than ever before playing to the global audience. Even with the VOD boom, digital purchase and rental constitute a small portion of the world’s movie transactions. According to IHS Media and Technology Digest, theatrical ticket sales, purchase and rental of physical media (DVD, Blu-ray) add up to nearly 12 billion transactions, while Pay Per View, streaming, and downloads come to only about a billion or so. (These categories omit subscription services like cable television and basic VOD on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and the like.) Moreover, customers in 2012 spent about 61 billion dollars buying tickets to movies, buying DVDs, and renting DVDs. Tania Loeffler of the IHS Digest writes of North America, the most developed market for digital sales and rental:

Movie purchases made online in North America increased year-on-year by 36.6 per cent to reach 29.2m transactions. The rental of movies online also increased, to 112m transactions, an increase of 57.3 per cent over 2011. Despite this strong growth, movies purchased or rented via over-the-top (OTT) online movie services still only accounted for a combined $836m, or 3.3 per cent of total consumer spending on movies in North America.

By contrast, worldwide consumer spending on theatrical movies actually grew in 2012, to a whopping $33.4 billion–over 50 % of all movie transactions. (Thank you, Russia and China.) And despite the decline of disc purchases and rentals, Loeffler estimates that physical media will still comprise about thirty per cent of worldwide movie transactions through to 2016.

Theatrical releases continue to offer studios the best deal. Because the prices of streaming and downloaded films are low, there is less to be gained from them. True, if windows shrink, the studios will demand that Netflix and its confrères price VOD at high levels, say $25-50 for an opening-weekend rental. But consumers used to cheap movies on demand could balk at premium pricing.

At present, digital delivery of movies to the home provides solid ancillary income to the distributors, even if it doesn’t yet offset the decline in physical media. Add in Imax and 3D upcharges, and things are proceeding well for the moment. Like the rest of us, moguls pay their mortgages in dollars, not percentages or transactions. As long as some hits keep coming, we should expect that studios will maintain an exclusive multiplex run for major releases, as the most currently reliable return on investment.

Orpheum metamorphosis

The New Orpheum Theatre, 216 State Street, 1927.

Another note on exhibition relates to the last commercial picture palace in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. My July 2012 entry related the conspiratorial tale of how the grand old Orpheum Theatre on State Street fell on hard times. In fall of 2012 the building seemed slated for foreclosure, but then maybe not. Last month Gus Paras, a hero of my initial post, stepped forward and bought the old place. According to Joe Tarr in our politics and culture weekly Isthmus, there’s a lot of work to do.

Plaster is crumbling off sections of the ceiling, the result of years of water damage from a leaky roof. The walls are littered with scratches and marks, in bad need of a paint job. A plastic garbage can sits in the theater, collecting water leaking from an upstairs urinal. Paras even found dried-up vomit in two spots on the carpet.

Making matters worse, Monona State Bank, which controlled the property while it was in foreclosure, filled in the “vaults” behind the theater, which means replacing the building’s frail boilers and air conditioning will be much more complicated and expensive.

“I don’t have any idea how I’ll get the boiler in and out,” Paras says. “The stairs are not strong enough.”

Envoi

Have any of you worked on a film, say, 10 years ago, and it comes out on Blu-ray and you look at it and think, “This isn’t the film I’ve shot”?

Bruno Delbonnel (DP, Inside Llewyn Davis): Always. Always.

Barry Ackroyd (DP, Captain Phillips): I’ll be watching and it’s in the wrong format.

So what is it like to devote your lives and careers to creating images that you know exist only momentarily in their absolute best state, that may never be seen by most people the way you would like them to be seen?

Sean Bobbitt (DP, Twelve Years a Slave): At least you get a chance to see it once. All you can do is hope that people will see an approximation of that. I’ve been to screenings where I’ve had to get up and walk out because I just couldn’t bear to watch the film in the state it was in. But at the end of the screening, people say, “That was fantastic. That was beautiful. Well done!” and you’re thinking, “If only they had seen the real thing.” We would drive ourselves mad if we worried too much about it.

On shrinking windows, see Andrew Wallenstein and Ramin Setoodeh, “Exhibitors Explode over Netflix Bomb,” Variety (5 November 2013), 16. The chart on this page doesn’t appear in Variety‘s online edition of the story. Tania Loeffer’s report, “Transactional Movies: The Big Picture,” appeared in IHS Screen Digest (now IHS Media and Technology Digest) for April 2013, 123-126. Douglas Gomery discusses the theatre television plans of the 1940s-early 1950s in his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, pp. 231-234. My envoi comes from a revealing conversation among cinematographers at The Hollywood Reporter.

A 2012 catchup blog chronicling earlier phases of these developments is here.

P.S. 23 December 2013: David Strohmaier, the creative force behind the Cinerama restorations, has put online the stirring original trailers for Search for Paradise (low resolution and high-definition) . David attended the U of Iowa when Kristin and I did, though alas we didn’t meet him. He deserves a big thank-you for all his work in making these extraordinary films available to us.

The Grandmaster.