Archive for February 2013

Oscar fever up close

Kristin here:

Most years when I’m at home, I join in our departmental Oscar party, where grad student and faculty get together to watch the broadcast and match wits at predicting the winners. It beats the grimness of sitting home watching the show.

But this year, being a relatively new staff member on TheOneRing.net, I decided to attend their celebration, “The One Expected Party,” for The Hobbit. TORn put on three Oscar parties for The Lord of the Rings, in 2002, 2003, and 2004. Those parties became the stuff of legend within the fandom, having rapidly sold out each time. The nominees and winners from the trilogy dropped by the TORn party each year (fueling the next year’s ticket sales). I wrote about the Oscar parties as part of my coverage of TORn in my book, The Frodo Franchise, but I had never been to any of them.

In planning my trip, I quickly discovered that there are a lot of other activities around the run-up to the Oscar ceremony. I knew, of course, that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences offers screenings of the nominated films to their members and to anyone else lucky enough to get a ticket. But our old friend Chen Mei, who works for the Academy library, told me about panel sessions featuring the nominees in various categories and kindly obtained tickets for me to attend two of them.

Obviously the nominees take these events seriously. For both of those I attended, with one exception all the directors of the nominated films showed up to answer questions from a moderator. Obviously they couldn’t hope to influence the members’ votes, since the ballots had already been turned in. They generously gave time to offer insights into their work to audiences who clearly were knowledgeable about filmmaking.

“Oscar Celebrates Animated Features”

This panel discussion took place on the evening of February 21, the day I arrived in Los Angeles. When I got to the Academy’s Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, more than an hour before the 7:30 event, there was already a long line of ticket-holders hoping to get good seats. I gathered from conversations with people around me in line that tickets are getting harder to obtain each year.

Most of the best seats were roped off, reserved for Academy members and the guests of honor. I got an unreserved one in the second row but way over on the side. It actually gave a pretty good view of the stage. Unfortunately photos are strictly forbidden inside the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, so I have none to show you.

Most of the best seats were roped off, reserved for Academy members and the guests of honor. I got an unreserved one in the second row but way over on the side. It actually gave a pretty good view of the stage. Unfortunately photos are strictly forbidden inside the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre, so I have none to show you.

Almost all of the directors of all five nominated features were there: Peter Lord for The Pirates! Band of Misfits; Sam Fell and Chris Butler for ParaNorman; Mark Andrews for Brave (co-director Brenda Chapman being unable to attend); Rich Moore for Wreck-It Ralph; and Tim Burton for Frankenweenie. (All but Burton stuck around to pose for the press; left to right, Moore, Butler, Andrews, Lord, and Fell.)

This line-up of talent should have made for an enlightening evening. Unfortunately the AMPAS had chosen as MC a comic actor, Rob Riggle (Talladega Nights, The Hangover) who turned out to know less about animation than most of the people in the audience did. He was obviously more concerned with being entertaining than with drawing out any solid information about the films. He kept asking the guests what inspired them to make their films, while very little got said about the films’ innovative techniques and the challenges the filmmakers faced–in short, about the films. Despite this obstacle, the guests managed to say some interesting things. There was obviously no audio recording either, so I frantically took notes.

One motif that cropped up several times was the fact that this year’s nominees included three stop-motion films. But as some of the animators emphasized, despite their love for the slow, frame-by-frame manipulation of puppets and objects, they do mix in new technologies. Fell described himself and fellow director Butler as “Luddites who’ve embraced the loom.” For example, although ParaNorman‘s young witch Aggie was animated as a puppet, her dress was an added digital effect. As Butler said, although they basically work with puppets, they will use whatever animation technique will look best on the screen. (Earlier this month, I discussed the use of color laser printing that made the wide variety of character expressions possible.)

Lord twice mentioned the convivial atmosphere created at Aardman’s Bristol studio, where people who love puppet animation have come together as a team. They avoid computer animation whenever possible, preferring “the lovely, amazing toys in the world, stuff the animators work with at Aardman.”

Fell and Butler described their influences as the horror films they saw during their childhoods in England. Butler had watched Night of the Living Dead at age 6, and Fell referred to “video nasties,” as they are labeled in England, very violent films that were banned or at least difficult to see. The age of VHS made such films as Driller Killer available, as Fell pointed out, though Butler hastened to point out that that particular film had not influenced ParaNorman.

Moore, who had directed episodes of both The Simpsons and Futurama, made Wreck-It Ralph as his first feature. Asked the difference between episodic animated TV and features, he responded that in features, characters move through an arc that changes their situation by the end. In TV, the characters start at square one, play out an action, and end up on square one by the end, ready to do the same thing the following week.

Burton was asked the difference between the original Frankenweenie short and the feature. Because the feature was animated, he considers it “a more pure version” of the original live-action short. In working on the style of the set designs for the feature, he went back not to the short itself, but to the drawings he had originally done for it. He also admitted that during the early days when he was had a job at Disney drawing cels for The Fox and the Hound (1981), his drawings of the fox looked “like road kill.”

Interlude: Ground Zero, the Dolby Theatre

The grand theater on Hollywood Boulevard where the awards ceremony takes place may now be named the Dolby, but it remains the Kodak Theatre on Google Maps and in the minds of the many who still call it that. Then again, I heard people at one of the Academy panels refer to “Grauman’s Chinese Theatre,” despite that fact that the Mann’s chain acquired it decades ago and it has again changed hands.

I was staying in the Hilton Garden Inn, on Highland Avenue a few blocks north of where it intersects Hollywood Boulevard at the corner dominated by the Dolby Theatre’s huge complex. Having a free morning on Friday, I wandered down, looking to take some pictures of the Oscar preparations.

The Dolby Theatre is also a shopping mall. It is surely the only mall in the world modeled on the work of D. W. Griffith, specifically his Babylon sets from Intolerance. Giant white elephants on pillars loom over tourists. (Top, and at left, a view looking toward the back of the complex from the north.)

Naturally the block of Hollywood Boulevard in front of the theatre was closed to traffic. Online one could find a complicated schedule of road and even sidewalk closings that went on for as much as a week before the day of the ceremony. Fortunately on this day the sidewalks were still open, so I could join the tourists watching the preparations and snapping photos. The bleachers had been installed, as had the famous red carpet. A larger nearby parking lot was filled with trailers sprouting satellite dishes. The infrastructure for this event is vast, as one would imagine. It’s also far from glamorous.

“Oscar Celebrates Foreign Language Films”

On Saturday morning I got to the Samuel Goldwyn Theatre earlier, about 8:30 am for a 10:00 event. This time I was among the first twenty-five or so in line and got an excellent seat in the third row opposite the podium. Mark Johnson, who until recently ran the foreign-language category, was the MC. David and I have known Mark for years, since the early 1970s, when we were all in graduate school in film studies at the University of Iowa. Between his film education and extensive work in the industry (including producing the Chronicles of Narnia films, Rain Man, Galaxy Quest, A Little Princess, and Breaking Bad), Mark was an excellent choice to host the event, as he had done several times in past years.

All the directors showed up: Michael Haneke for Amour; Kim Nguyen for War Witch; Pablo Larraín for No, Nikolaj Arcel for A Royal Affair; and Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg for Kon-Tiki. (I discussed No and A Royal Affair in a report from the Vancouver International Film Festival last year.)

As each director came onstage, Mark graciously asked him to acknowledge any members of his filmmaking team who were in the audience. These included three of the four producers of Amour, Stefan Arndt, Veit Heiduschka, and Michael Katz. When Mark asked where the fourth producer, Margaret Menegoz was, Haneke got off the first zingy of the evening, saying that she would be arriving that evening: “She was picking up the Césars.” (On Friday, Amour won five, for best picture, director, original screenplay, actor, and actress).

Mark’s excellent questions solicited much information. I can’t summarize it all, but here are some highlights, film by film.

Arcel emphasized how difficult it was to finance A Royal Affair, given that it was a big, expensive costume picture: “It’s a risk in Denmark, where we have more the kitchen drama.” Although Zentropa Productions made the film, there was considerable investment from other European countries. One of the film’s stars, Mikkel Boe Følsgaard, was an acting student when he was cast as the eccentric Danish king, and he won the best actor prize at Berlin. Arcel revealed that after making A Royal Affair, Følsgaard went back to resume his acting-school education, where the next unit was on film acting. A Royal Affair was the only nominee shot on 35mm. Rather than following the European art-cinema tradition, he was influenced by his favorite Hollywood films, like Gone with the Wind and Lawrence of Arabia.

No was the third film in a trilogy about the Pinochet years in Chile, the earlier ones being Tony Manero (2008) and Post Mortem (2010). Mark asked Larraín if he had initially planned a trilogy. He said no, “I would say it is mostly the press who have named this a trilogy.” On the other hand, he thinks the term makes sense when applied to these films, and he has no objection. He commented that the film depicts how the same tools of propaganda Pinochet used on the people were turned against him. Rather than staging a violent takeover, “They put him out with the tools of beauty.” His filmmaking team had intended the lead role for Gael García Bernal from the start, despite his being a Mexican actor. The other actors had been with Larraín on previous films and all are well-known in Chile.

Larraín also talked about the four 1983 video cameras that were used to simulate older footage, each of which produced footage with a slightly different look. The team was worried about the various shots not cutting together smoothly with each other and with the archival footage that was integrated into the film. During editing, however, they began to forget which footage was new and which was archival and realized that they were succeeding. “What we shot became documentary, and the documentary shots became fiction.”

Nguyen talked about casting War Witch. Seventy-five per cent of the cast were non-actors. Rachel Mwanza, who played a young African girl forced to serve as a child soldier, was recommended by some documentarists who had filmed her as part of a group of homeless street kids; she had been abandoned by her parents at age 6. The film was shot with an Alexa. Tires constantly burning in the streets of Kinshasa created a haze that the filmmakers used as a filter for the natural light. Nguyen read many autobiographies of child soldiers as models for the voiceover narration in the film.

Rønning and Sandberg were inspired by the story of Thor Heyerdahl’s raft voyage from South America to Polynesia in 1947. Heyerdahl was a national legend, and his documentary record of the trip, Kon-Tiki (1950), won the only Oscar so far awarded a Norwegian film. Heyerdahl’s life was extremely well-documented in his diaries, which guided the scriptwriting. The filmmakers were lucky enough to gain access to a replica of the original raft, which had been made by Heyerdahl’s grandson to repeat the original voyage. The shooting at sea lasted for a month. In addition, however, there were over 500 special-effects shots–making Kon-Tiki, like A Royal Affair, a big-budget, Hollywood-style film. The directors said that with so much drama on TV, they wanted to create an epic that cried out to be seen on a big theatre screen. The effects were mainly for creating sharks and other creatures, extending sets, and occasionally erasing boats or shorelines in backgrounds.

Mark pointed out to Haneke that a lot of Americans know Amour is good but avoid seeing it because they think it’s too grim. Haneke blamed the American media for giving that impression of the film, saying that he considers it to be about love rather than death. But with a smile he also admitted, “I’m afraid it’s partly my fault.” He has gotten a reputation “for inflicting pain on audiences.” From the start he had planned the film around Jean-Louis Trintignant and would not have made it had he refused the part. Emmanuelle Riva, however, he found through the conventional casting process of auditions.

Mark mentioned the fact that the film juxtaposes wide views with close-ups, with few camera distances in between. Some scenes play out in a single long shot. Haneke responded “I want to give my audience time to reflect […] I try to manipulate the audience as little as possible.” Mark pointed out that in spite of this, the spectator always knows where to look. Haneke replied: “It’s all a question of craft.” (This drew applause from the audience.) The apartment in the film was a set, a choice made mainly because the older actors could not work long hours in difficult circumstances. The views seen through the windows were added with computer effects. Haneke dislikes non-diegetic music in films, and so he writes characters who would naturally be playing or listening to music within the story. In the case of Amour, he chose all the classical music before writing the script.

“The Art of Production Design”

The AMPAS isn’t the only organization hosting events around the presence of so many Oscar nominees being in Los Angeles. Straight from the foreign-film event I went with our friend Jonathan Kuntz, who teaches film and television at Los Angeles City College and the University of California at Los Angeles, to the Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. There the Art Directors Guild, the Set Decorators Society of America, and the American Cinematheque were presenting a similar panel discussion on “The Art of Production Design.” Nearly all the nominees were present (with production designer listed first and set  decorator(s) second): Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer for Anna Karenina; Dan Hennah and set decorators Ra Vincent and Simon Bright for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey; Eve Stewart and Anna Lynch-Robinson for Les Misérables; David Gropman and Anna Pinnock for Life of Pi (at right); and Rick Carter for Lincoln (set decorator Jim Erickson couldn’t attend). The co-moderators were Thomas A. Walsh, Production Designer and Co-Chair ADG Film Society with Academy Governor Rosemary Brandenburg, SDSA.

decorator(s) second): Sarah Greenwood and Katie Spencer for Anna Karenina; Dan Hennah and set decorators Ra Vincent and Simon Bright for The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey; Eve Stewart and Anna Lynch-Robinson for Les Misérables; David Gropman and Anna Pinnock for Life of Pi (at right); and Rick Carter for Lincoln (set decorator Jim Erickson couldn’t attend). The co-moderators were Thomas A. Walsh, Production Designer and Co-Chair ADG Film Society with Academy Governor Rosemary Brandenburg, SDSA.

Greenwood stressed how little time there had been to prepare the sets for Anna Karenina. The production at first was intended to be a conventional version, and location-scouting was done in Russia. The team decided to shoot in London, but there was no unifying conception until twelve weeks before principal photography director Joe Wright decided to stage the action in a set representing a theatre. There ended up being twelve days to actually construct the set, with the designers marking the sets in chalk on the floor and starting to build before there were drawings of them. She describes the theatre set as “rich but minimalist,” since the approach was to remove as many items as possible.

Hennah answered a question from the audience concerning where conceptual design, done for The Hobbit by illustrators John Howe and Alan Lee, ends and production design begins. He responded that conceptual design involves creating the environments as a whole, as if they were real places. “The production design kicks in in terms of what takes place in the parts of that set.” The sets were drawn digitally and then built as 3D models that went to the pre-viz department. Howe and Lee worked in at Weta Digital rather than in the art department, as did an assistant art director. Vincent and Bright both consulted on the color grading, among other roles.

Hennah spoke of the design of the huge Goblin Town set. He conceived it as having been built within a great diagonal rift inside the mountain caused by an earthquake. The Goblins being thieves, they constructed the buildings and bridges out of random stolen items like carts. The layout of the Dwarves kingdom within the Lonely Mountain derived from the idea that the space expanded randomly as the workers removed stone to follow veins of gold.

According to Stewart, the filmmakers did not try to make Les Misérables a faithful reproduction of the stage play. They wanted to do what the stage version couldn’t: “You can’t see big wides and you can’t see up people’s nostrils.” Hence the film utilized sweeping cityscapes with huge buildings and crowds, while the musical numbers are filmed in relentless close-ups. Tom Hooper likes to “make things up on the day,” so Stewart had to make the sets bigger than usual, since she couldn’t plan ahead for what he might improvise during filming.

Given how much of Life of Pi was shot in tanks, what did the designers have to do? Gropman explained that they designed the interior of the Indian house where the early part of the story is set, with the interiors being constructed in Montreal and the exteriors shot in India. The apartment in the frame story had to be simple and bland, so that it would not reflect the character at all. Since the film was not shot in continuity, a big challenge was keeping track of the deterioration of the lifeboat, which becomes more worn and damaged.

Given how much of Life of Pi was shot in tanks, what did the designers have to do? Gropman explained that they designed the interior of the Indian house where the early part of the story is set, with the interiors being constructed in Montreal and the exteriors shot in India. The apartment in the frame story had to be simple and bland, so that it would not reflect the character at all. Since the film was not shot in continuity, a big challenge was keeping track of the deterioration of the lifeboat, which becomes more worn and damaged.

Gropman asked artist Haan Lee, director Ang Lee’s son, to design the raft that Pi builds, and he came up with the idea of the raft as a triangle. The island was based on a single huge banyan tree in southern Taiwan, which was filmed for a day and then built in the studio.

Carter described having spent part of a day in the White House in preparation for Lincoln, including being left alone in the evening in the Lincoln bedroom. He graciously emphasized the importance of the set decoration, by the absent Erickson, as the main aspect of the settings that makes an impression on the audience. Virtually every day during the president’s last year of life was heavily documented, and research informed the set dressings. The designers also spent much time in Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, which Carter considered a city almost as much influenced by Lincoln as was Springfield, Illinois.

A member of the audience asked what effect 3D had had on the designers’ work. The two designers of 3D films gave similar answers. Gropman remarked, “There’s nothing you do where you’re not thinking about foreground, middle ground, and background. […] We’re creating the environment primarily for the actors.” Hennah’s response was, “It doesn’t change anything in terms of how you approach it. […] It’s about giving a feeling of depth and a feeling of separation, which you would do in the real world anyway.” In other words, 2D films have always had plenty of depth cues.

Afterward Jonathan introduced me to Rick Carter, a long-time friend with whom he had gone to school (Jonathan on the left, Rick on the right). He turned out to be the one from the group who won the Oscar the next evening.

The Hobbit, win or lose

TheOneRing.net’s celebration of The Hobbit‘s three nominations (production design, makeup and hairstyling, and visual effects) began on Friday night with an art show. I was one of many volunteers helping out with setting up that and the Sunday night party, so I ventured into the labyrinth of old warehouses east of downtown, an area now established as an arts district.

The show drew some major exhibitors, including veteran Tolkien illustrator Tim Kirk, seen above posing with his most famous paintings. I was also delighted to meet some fellow TORn staff members whom I had previously only known from the group email messages we exchange and from their postings on the site. They’re an enthusiastic group who all work on a strictly volunteer basis.

The big event was on Sunday at the Hollywood American Legion hall (at bottom, the entrance, with a representation of the Arkenstone above the door and a life-sized Gollum statue lurking inside to provide a photo op). I helped out with the setup that morning, hanging signs and folding a great many “One Expected Party” T-shirts to be sold in the “Rivendell” room (aka the shop).

The main auditorium, dubbed “The Hall of the Elven-King” for the occasion, was where most of the celebrants gathered to watch the Oscars on a vast TV screen. If they turned around, they would notice that a full sized cave troll from The Fellowship of the Ring was watching along with them:

I managed to watch the first half of the show but then was slotted to help sell T-shirts and CDs by the band that would be playing after the Oscar show ended: Billy Boyd’s “Beecake.” I was there long enough to sit through two of the categories for which The Hobbit was nominated and to be nearly deafened by the cheers–and then groans of disappointment. The fans reassure each other that as with The Lord of the Rings, the third part will scoop up Oscars serving to reward the whole trilogy.

Being in “Rivendell” selling stuff, I missed the second half of the show, but I gather that was not much of a loss. The Oscar fever being exhibited elsewhere in the building and around town turned out to be more interesting than the ceremony itself.

Donald Richie

Donald Richie and students. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

DB here:

He died last week, aged 88.

What was his life about? The public dimensions involved, of course, his status as unofficial spokesman, principal gaijin, the gatekeeper and guide to anyone interested in Japan. He hosted grad students as genially as he played tour guide to Truman Capote and Susan Sontag and Jim Jarmusch. I don’t know of any other situation in which an American (from Lima, Ohio, no less) became the spokesperson for a foreign culture. From the 1950s into the 2010s, in a stream of writings and lectures, he interpreted how the Japanese lived, worked, thought, and created. Although he wrote about everything from landscape to tattoos, he became best known as the supreme expert on Japanese cinema. His particular love was the postwar “Golden Age” of the late 1940s through the early 1960s.

Tokyo/Hibiya crossing; Dai-Ichi Building, 1947.

Japan was still terra incognita to Westerners when he came there in 1947. When the outer world demanded to understand this very strange place that had fought so tenaciously against America, there arose a generation of interpreters. Of that cadre, though, he stands out as the man you can’t quite place.

The oldest of the group was Edwin Reischauer, who worked largely in international policy. A somewhat younger man, Donald Keene, became the dean of Japanese literary studies. Keene has provided translations and magisterial overviews of the Japanese novel, drama, and poetry. An almost exact contemporary of Keene’s is Edward Seidensticker, who has been a renowned translator and cultural historian.

Only a little younger was our author, who came to Japan in the Navy and soon became a prolific writer. Yet his work didn’t fit the mold of the other American experts on Japan. He was neither a traditional scholar (he read little Japanese, though he spoke it fluently) nor a pure journalist (he refused to be tied to topicality). He remained resolutely in-between. What academic would have the brass to sum up “The Japanese Way of Seeing” in a seven-page essay? Yet what journalist would write subtle critical monographs on Ozu and Kurosawa?

In my copy of Partial Views: Essays on Contemporary Japan, he wrote: “For David, from Donald, particularly pp. 157-205.” On those pages you find his “Notes for a Study on Shohei Imamura.” It’s a fertile survey of recurring themes and techniques in Imamura’s films. In the hands of a professor it could certainly become a tightly argued book. Was his inscription telling me that, when he wanted to, he could execute criticism with an academic accent? If so, it was unnecessary. I didn’t need convincing. I think he could have done whatever he wanted.

What he wanted, I think, was to join the tradition of European belles lettres. He earned his living by writing, and doubtless his championship typing skills steered him toward the quick turnover of daily deadlines. More deeply, I think, he found the shorter piece suited his flair for precise evocation. Even in his books, his approach is essayistic, faceted. His tone—thoughtful but not severe, conversational, projecting wide knowledge and good sense and humane modesty—won the reader by its quiet conviction that the subject was important. This essay wouldn’t be the last word; indeed, he would likely return to the subject years later, testing out new ideas. Much of his output consists of occasion-based pieces, and any of these might be recast, cut, or expanded. A craftsman knows how to recycle scraps and spruce up old projects.

This commitment to fluent reflection on daily changes, along with a quality of seeing everything around him afresh, put him in the tradition of the Continental “man of letters.” He was an aesthete, a moralist, and a bit of a dandy. His natty clothes were like his literary style, crisp and elegant but not flamboyant.

His preferred mode was description. He was convinced that whereas Westerners struggle to probe the depths, “The Japanese realize that the only reality is surface reality.” During a visit to Madison, he was delighted to find a translation of the Goncourt brothers’ journals. I couldn’t help thinking that he took them as a model of the urbane curiosity and pellucid prose he cultivated.

Above all he was interested in people. He was an excellent observer but also a well-tempered listener. He chatted with barbers, students, masseuses, neighbor ladies, potters, delivery boys, executives, and celebrities. He listened to their complaints, their dreams, and their reports on the texture of their lives. Sometimes they quarreled with him or disappointed him. But each one gave him a glimpse of the wavering mirage that was Japan, or at least his Japan.

Ikiru (Kurosawa, 1952).

His writing skills worked on a big canvas in The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (1959). He wrote the text while his collaborator Joseph Anderson, who read Japanese, provided the research. The book came at just the right moment, when Americans were starting to appreciate the power of this nation’s cinema. To this day, despite many specialized studies of directors, periods, and genres, it remains the standard overview of one of the great national film traditions.

Just as important, for me at least, was The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968). The first edition, a magnificent buff volume with razor-sharp illustrations and double-column text, is a triumph of book design, as solid and imposing as the films it canvasses. Along with Robin Wood’s works on Hitchcock and Hawks, it showed that cinema could be studied with intellectual seriousness. To the auteurist’s search for the guiding themes of a director’s vision, the Kurosawa book brought a sharp eye for technique and a direct access to the artist himself. (Our author’s first visit to a movie set was to Drunken Angel.) And it proved that a great film could sustain shot-by-shot scrutiny.

Turn to any chapter and you will see a probing intelligence. For Ikiru, we get a detailed layout of image/ sound relations in the nighttown sequence, bracketed by Watanabe’s funeral. The analysis carries us to this conclusion:

He has become much more than simply dead. Just as, dying, he learns to live; so, dead, he becomes more alive for others than he ever was before.

The Kurosawa book remains an exceptional achievement in sympathetic imagination. The critic is so finely in tune with the creator’s sensibility that each chapter illuminates and amplifies the dynamics of the film. There are other ways of understanding Kurosawa, but this book will remain the compass that orients us to this essential director’s career.

Floating Weeds (Ozu, 1959).

There were other books, of course. Among the best is the rare 1961 Japanese Movies, published by the Japan Travel Bureau. It is a compact survey of the major directors working in the postwar era. You sense that its intense aesthetic appreciation of particular films arises from portions cut from The Japanese Film. Here the critic is working at full stretch, and his thoughts on Naruse, Mizoguchi, and others are still worth reading. In its fifteen pages on Ozu, then unknown in the West, lie the seeds of his book on the director.

We have him to thank for our awareness of Ozu. He persuaded the reluctant Shochiku company to release the films in Europe and the US. His ten years of effort were crowned by the release of several Ozu films in New York in 1971-1972. At that point, largely as a result of accidental access, Tokyo Story emerged as the director’s official masterpiece. Soon afterward there appeared Ozu: His Life and Films (1974), another monograph informed by personal acquaintance with the director.

The Kurosawa book dealt in depth with each film, but this took a more horizontal and modular approach, tracing a skein of similarities across Ozu’s work. As one would expect, the emphasis falls on the postwar films, which were more easily available and which the author saw as they were released. (“Revisionist” takes on Ozu, and Japanese cinema as a whole, would soon return to the 1920s and 1930s and find there an earlier Golden Age.) The chapter layout tends to assume that Ozu films are more uniform than they are, but for its attention to themes and script construction in particular Ozu is indispensable. The author’s love for the films shines through every page.

It’s sometimes said that he brought Japanese cinema to the west, but apart from his championing of Ozu, this is inexact. Rashomon opened in New York in 1951, and Gate of Hell won an Academy Award in 1955. Daiei and Toho studios exported several films to Europe and America, while distributor Thomas Brandon sought to bring less-known Kurosawas to the US. The Japanese Film arrived at a propitious moment in 1959, when it could capitalize on the wider circulation of titles. Not until the 1970s was America to see a resurgence of interest in Japanese cinema, thanks to the Ozu releases, the Ozu book,the circulating programs sponsored by the Japan Film Library Council, and the efforts of Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films.

Still, our author did something quite important. By talking about Japanese cinema in terms amenable to Western tastes, he integrated it into our film culture. Kurosawa as a robust humanist; Ozu as the serene contemplator of life’s transience: these became familiar figures thanks to his eloquent critical rhetoric. At the same time he retained a sense of their uniqueness, insisting in particular on the irreducible Japaneseness of Ozu’s aesthetic.

Although his major books remained essential for film lovers and film courses, it’s fair to say that he got a second wind in recent decades. He won a wide and keen following with his commentaries and liner essays for Criterion DVD releases of Japanese classics. The outpouring of grief after his death comes in large part from viewers who knew him best as a warm, calm voice talking through scenes of Tokyo Story or When a Woman Ascends the Stair or, surprisingly, Bresson’s Au hasard Balthasar. He adjusted well to the new world of video. He treated it as a new conduit for his commitment to civilized discussion.

Five Filosophical Fables (Richie, 1967).

So much for the public man, writer and speaker and animator of film culture. Another side of him was an intense erotic interest. On your first meeting, he made sure you knew what he found appealing. In the Journals, cruising and pickups blend with a swarm of local details of landscape and custom, although consummations are elided.

I had noticed that his suteteko, being thick cotton, are still damp from the swim, and so I suggest he take them off and hang them on a branch to dry. He does so.

*

Later, in the afternoon, I take a train around the coast. . . .

The juxtapositions between moments of artistic ecstasy and sexual passions give the journals a collage-like snap.

[Hiteki] got into all this ten years or so ago. Has no particular feeling for it but it is now all he knows. . . . Does everything but only, I feel because he does not know what else to do. It apparently means little. Small excitement. . . It represents, I guess, something better than nothing.

6 October 1990. Haydn quartets—the delicious Opus 50. They are made up only of themselves.

The diaries we have are very polished products, the results of much rewriting, and stretches are calculated to render the guilt-free sexiness that the wanderer finds all around him. Consider the finesse of this passage about a visit to Aoshima island:

Later we shop in the empty tourist arcades and buy some beautiful and indecent objects—cups you turn over to discover a coupled couple, an articulated vagina disguised as a shell, and a sake cup with a mushroom-shaped penis attached. One is to suck the sake from the mushroom head.

Some readers expect the Journals to be among the author’s most lasting work. They’re valuable as chronicles of the daily life he observed with sympathetic but dispassionate acuity, but they also record the mind and feelings of a man of Wildean sensitivity wandering among dazzling surfaces that kept his senses, and his libido, ever on the alert.

The surfaces might be rough. The journals record his enjoyment of living near Ueno Park, where the homeless and the prostitutes gather at night. He strolls through them, meeting the occasional cop and seeking, as he puts it, someone who can typify Japan in all its contradictions.

Beautiful and indecent: You can find this mixture in some of the experimental films he made too. The most inoffensive of these, Wargames (1962), was circulated among American film societies during the 1960s, but others are more audacious. In the allegorical satire Five Filosophical Fables (1967) a young man abandons a snooty party, strips to the buff, and strolls smiling through Tokyo streets, past the sea, and into the countryside. Cybele (1968), a documentary of an avant-garde theatre performance, presents an orgiastic rite of sex, degradation, and bloody sacrifice.

Roppongi Hills, Christmas 2010.

He was assailed by bouts of illness across two decades, but he seems never to have lost his buoyancy and spiky wit. He was especially mordant on the New Japan. He notes that the thrusting high-rise apartments of the 1980s bubble offer more for Godzilla to whack. “Originally [he] had to content himself with a mere Diet building.” Manga and the Sony Walkman were very much alike, he maintained. Each offered not visual or aural stimulation but a convenient way to shut oneself off from the ugliness of a money-grubbing society: solitary withdrawal amounted to a critique of contemporary life. With mock pathos he told of a salaryman so preoccupied with talking on his cellphone that a passing subway train snagged him and carried him off, the handset dropped squawking to the platform.

The humor could be self-deprecating. One of our conversations:

DB: I liked The Inland Sea.

DR: I traveled for three months and wrote it in three weeks.

DB: And I read it in three hours.

DR: You took too long.

When asked if he loved Japan, he replied, “That’s complicated . . . I love Tokyo.” Yet by the end of his life, his city had become alien to him. His Japan Journals begin by sketching the vibrant colors of a blasted landscape returning to life.

Winter 1947. Tokyo lies deep under a bank of clouds which move slowly out to sea as the sun climbs higher. Between the moving clouds are sections of the city: the raw gray of whole burned blocks spotted with the yellow of new-cut wood and the shining tile of recent roofs, the reds and browns of sections unburned, the dusty green of barely damaged parks, and the shallow blue of ornamental lakes. In the middle is the palace, moated and rectangular, gray outlined with green, the city stretching to the horizons all around it.

The final entry in the journals is dated nearly sixty years later and records a 2004 trip to his old neighborhood. Tansumachi of 1947 had become the fashionable Roppongi Hills district, “the new Japan—gargantuan, expensive, and wasteful.” A Louise Bourgeois statue looms over the pavement like a tarantula. He recalls the street once named Dragon’s Way and the friend’s house that used to stand at that corner. He knows that his nostalgia must seem tiresome and he acknowledges that rapid change is itself a Japanese tradition, a sort of high-tech version of the Floating World. Yet he cannot resist denouncing the Disneyland that the old place has become. He finds no arresting color or light in this world.

In just a number of years every place will look like it, and this kind of economic expediency will be the rule, as will those cute nods in the direction of retro and trad, that comedy team of contemporary design. Here, under the spider, I look into the future which is already here.

He was well aware of living in-between. Today we might say that he was perpetually “other,” too aesthetically sensitive for a mercantile society, too protective of tradition in a period of lightning change, too gay for straitlaced America, too eccentric and independent-minded for assimilation into his adopted nation. Painful as these tensions must have been, he proudly accepted being fundamentally out of place. At the end of one essay he claims his motto to be that of Hugo of Saint Victor:

The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land.

Extracts from Richie’s writings come from The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968 and later editions), A Lateral View (1992), and The Japan Journals, ed. Leza Lowitz (2005). Richie’s films are available on DVD as A Donald Richie Film Anthology from Image Forum Video. See also The Donald Richie Reader (2001), ed. Arturo Silva, for a varied collection of pieces, including articles on how he came to write about film, and his lively tour Tokyo: A View of the City (1999), with photos by Joel Sackett. The photo of Tokyo/ Hibiya crossing comes from the Journals, the shot of Roppongi Hills from Tokyofashion.com.

For a provocative review of The Japan Journals, see Richard Lloyd Parry’s “Smilingly Excluded.” Kim Hendrickson, who produced Richie’s DVD commentaries, provides a tribute on the Criterion site. A list of his commentaries and liner notes is on this page.

For more on how Japanese films came into the United States, see Chapter 6 of Tino Balio, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973.

Thanks to Tony Rayns for conversations and assistance.

Elsewhere on this site are other Richie-related entries, particularly here and here.

P.S. 25 February: Karen Severns has set up a Donald Richie tribute page here.

Donald Richie at the grave of Ozu. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1934)

The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934).

DB here:

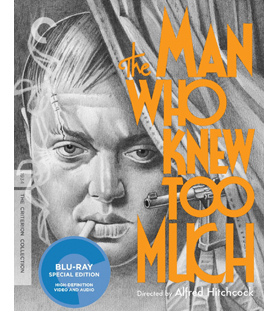

Hitchcock made six remarkable thrillers from 1934 through 1938, and I have long believed that the first one was the best. I think very well of Sabotage, and both The Lady Vanishes and The 39 Steps are strong contenders. But for me, The Man Who Knew Too Much has got damn near everything going for it.

I came to it a little late. It wasn’t the first Hitchcock I wrote about; that was Notorious, in a 1969 piece that nakedly reveals the limitations of a college senior’s knowledge. Nor was it the first Hitchcock I saw; that was Vertigo, when I was about ten. Inauspiciously for me, when Vertigo was revived for national television broadcast in 1972, I was flying to a job interview in Madison, Wisconsin.

I got that job, though, and soon The Man Who Knew Too Much became very important for me. Seeing it at a film society screening, I was bowled over. Then I discovered that it was available for purchase in a cheap 16mm print. I bought a print and began teaching the film as a model of narrative construction. It worked its way into the first edition of Film Art, in 1979 and hung around there for several editions.

That sample analysis has been available as a pdf on our site, but check it out at the Criterion site, where it’s enhanced with nice frame enlargements and a major extract. The essay makes my case for the movie as an extremely well-constructed piece in the classical storytelling tradition.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

So I was the ideal consumer for a spruced-up DVD/ Blu-ray release, and as usual Criterion doesn’t disappoint. It’s a handsome version, with some fine supplements. We get two rare interviews with Sir Alfred from CBS’s arts program Camera Three (featuring Pia Lindstrom and William K. Everson) and a perceptive discussion with Guillermo del Toro, who makes a vigorous case for the film. So does Philip Kemp in his commentary, which is strong on production background. Kemp offers valuable information on script versions and on Hitchcock’s niche in the English industry. The accompanying booklet includes a lively appreciation by The Self-Styled Siren, aka Farran Smith Nehme.

Interest in Hitchcock seems to be the one constant in the whirligig of tastes in film culture. He is a mainstay of home video and cable television; apparently the films can be re-released in perpetuity. Professors love to teach his films. The techniques are obvious and vivid, and the films offer a manageable complexity that encourages interpretation. Class, gender, power, the law—whatever your favorite themes, they’re all on the surface, yet enticingly ambivalent. Not to mention how much fun these movies are to watch. I’ve always enjoyed introducing “lesser Hitchcock” like Stage Fright and Dial M for Murder and then watching the audience fall under their spell.

Critics navigate by Hitchcock as a fixed pole star. Reviewers compare every new thriller to the classics of The Master of Suspense. Just look at what people write about Soderbergh’s Side Effects. And for those who promoted the auteur approach to Hollywood cinema, Hitchcock was a beachhead. Who could doubt that this man turned out personal projects within the impersonal machine known as Hollywood? And if he could do it, why not Ford, Hawks, Sternberg, Ray, and all the rest? Hitchcock nudged skeptics down the slippery slope toward auteurism.

Even if Hitchcock isn’t to your taste, you can’t avoid his influence. That became obvious around the 1970s, when directors began borrowing from him more or less overtly: Spielberg’s Vertigo track-and-zoom in Jaws (now itself a convention), De Palma’s homages/pastiches, Polanski’s use of point-of-view in Repulsion and Rosemary’s Baby, the endless Psycho sequels and the van Sant remake, and the rest. But Hitch was no less influential in his own day; I’d argue that filmmakers of the 1940s had to raise their game if they wanted to meet the challenge of Rebecca, Foreign Correspondent, Suspicion, Shadow of a Doubt, Spellbound, and Notorious. Billy Wilder told a reporter that Double Indemnity was his effort to “out-Hitch Hitch.”

What was so special? Obviously, the throwaway humor—sometimes airy, sometimes slapstick, sometimes sardonic. And obviously a gift for switching situations around, playing them against cliché, setting us up for a jolt. But I think there’s something else afoot. Part of the Master’s repute rests on virtuosity of film technique. Hitchcock makes movie movies, even when, like Rope or Dial M, they seem “theatrical.” And this movieness is best seen, I think, by considering a term that always comes up with Lord Alfred: the set piece.

Maintaining a tradition

Hitchcock held onto the flamboyant expressive devices of silent and early sound cinema far longer than any other director. For decades he kept alive techniques that many directors thought were old hat: abrupt cuts to details of gestures and objects; blurry point-of-view images to suggest distraught or befuddled states of mind (as above); very brief insert shots to accentuate violence. Compare Battleship Potemkin with Foreign Correspondent’s assassination scene.

Hitchcock built entire films around classic silent techniques. The Kuleshov effect governs Rear Window; the German “entfesselte” or “unchained” camera dominates Rope and Under Capricorn. Rope and Dial M revive the aesthetics of the German kammerspielfilm, or “chamber play.” The Germanic look was alive and well in the spiderweb shadow-work of Suspicion, while both French Impressionism and German Expressionism inform the dream sequences of Spellbound and Vertigo. He also preserved the “creative use of sound” that was the hallmark of directors like Clair and Milestone. While others had pretty much given up the expressionistic use of music and effects, Hitchcock was always ready to draw on them. The hallucinatory Merry Widow Waltz haunts Shadow of a Doubt, while Hitchcock’s penchant for giving us two pieces of information simultaneously, one in the image and another on the soundtrack, let him design scenes visually and push a lot of dialogue offscreen.

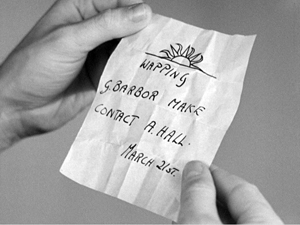

This flexibility of technique modulates from scene to scene. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, note-reading is presented in three ways, in rapid succession. First, Bob finds Louis’ note in the hairbrush.

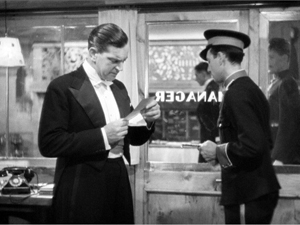

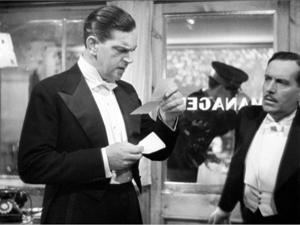

Soon Bob gets a message from the front desk. What does it say? Hitchcock hides that by, for once, not supplying subjective point of view.

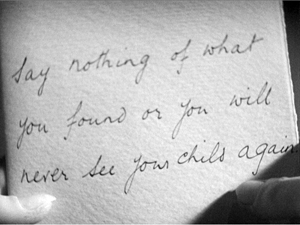

Only when the note is passed to Jill do we get to see it, but with a twist. Nobody but Hitchcock would add an extra shot that cuts to the note in her hand without revealing what it says.

That extra shot is what Eisenstein called a primer; as with dynamite, you need a little charge to trigger the blast.

We often forget that classic silent directors used their pictorial techniques for suspense. Lang’s Mabuse films and Spione furnish plenty of instances, but so do the Soviet montage films. The scene in which the police wait for the worker to return to his wife in The End of St. Petersburg now looks like pure Hitchcock, and of course the Odessa Steps sequence was the Psycho shower of its day. So it isn’t surprising that Hitchcock would turn his silent-film virtuosity toward creating scenes of high tension and threatened violence. Nor is it surprising that his skills would crystallize in “set pieces.”

Everybody talks about Hitchcock’s fondness for set pieces. It’s part of his brand. We have the Statue of Liberty climax in Saboteur, the milk carried up the staircase in Suspicion, the milk-and-razor scene and the final suicide in Spellbound, the spectacular rescue of Alicia at the end of Notorious, and the efforts of Bruno to retrieve the lighter in Strangers on a Train.

But, come to think of it, what makes something a set piece?

Game, set piece, match

Foreign Correspondent (1940).

As commonly understood in the arts, a set piece is a fairly self-contained portion of a larger work. It has a distinct beginning and end, and it’s understandable and impressive if extracted from its original. It’s designed to be a bravura display of concentrated virtuosity. In music, an example would be an operatic aria like the Queen of the Night’s in The Magic Flute: it is so flashy and complete in itself that it can enjoyed on its own, in a concert setting.

Two early uses of the term shed light on its implications. In stage parlance, a “set piece” is an item of the set that can stand alone, like a gate or fake tree. In pyrotechnics, a “set piece” is a carefully patterned arrangement of fireworks; here again, it implies a display that dazzles the audience.

In the silent era, I’d suggest, the clearest exponent of set pieces is Eisenstein, who became known as “the master of the episode.” Many of his big scenes, like the Odessa Steps massacre, are developed at such length that they function as mini-films. But you can consider passages in Chaplin and Keaton as set pieces—the dance of the breadrolls in The Gold Rush perhaps, or the windstorm in Steambout Bill, Jr. The musical would seem to be a natural home of the set piece, with numbers standing out against more mundane scenes. In modern cinema, again under the aegis of Hitchcock: De Palma offers plenty, and perhaps the prize fights in Raging Bull constitute a string of them. Today the home of the set piece is the action picture; the chases and fights are the main attraction, and the genre challenges directors and crew to find new ways to intoxicate us.

The aesthetic of the set piece implies that some scenes function as filler while others get the whipped-up treatment. If that’s right, many great directors don’t favor mounting set pieces. Ozu, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Hawks, and others present what we might call “through-composed” films. Just as Wagnerian opera and its successors minimized set pieces, these filmmakers create a surface texture that doesn’t create self-contained high points. (I grant you that the immolation of Herlofs Marthe in Dreyer’s Day of Wrath might count.)

Given the detachable quality of set pieces, it’s true that some of Hitchcock’s can seem implausible or gratuitous. How essential is Guy’s lighter to any plausible scheme of Bruno’s? If you want to kill Roger Thornhill, why send him to a crossroads in Midwest corn country? (A knife in the back on the Greyhound is more reliable.) It was this tendency to sacrifice story logic for stunning anthology bits that Raymond Chandler deplored:

The thing that amuses me about Hitchcock is the way he directs a film in his head before he knows what the story is. You find yourself trying to rationalize the shots he wants to make rather than the story. Every time you get set he jabs you off balance by wanting to do a love scene on top of the Jefferson Memorial or something like that.

Chandler has a point. How do you integrate a set piece into a whole movie? (I’ll make some suggestions shortly.) But first, give Hitch his due. For him, I think a set piece was a compact repository of inherently cinematic ideas carried to a limit within a sequence. A set piece is a challenge: How much can you squeeze out of a situation?

Go back to Foreign Correspondent. Setting an assassination in Amsterdam allowed Hitchcock to integrate the idea of a clue based on a waywardly turning windmill. So far, Chandler’s objection seems tenable: The windmill is just a gimmick. But once Hitchcock sets his hero exploring the lair, he can create a set piece that answers a question that no one ever thought to ask before: How do you eavesdrop in a windmill?

Johnny Jones has to evade the killers by crawling up alongside the giant gears, then down, then up again. At each step he barely escapes being spotted. When he seems safe, his topcoat gets snagged in the grinding gears, so he has to slip his arm out of it—just in time to avoid being crushed.

Yet once Jones is freed from the coat, it’s carried around the gearwork and might be spotted by the gang. And the old diplomat upstairs, mind hazed by drugs, is likely to reveal Jones’ presence. Hitchcock squeezes seven minutes of suspense out of all this, with a casual air that suggests: Of course, dear chap, any director worth his salary can see that a windmill harbors all kinds of excruciating menace. All in a day’s work, you know.

A whispered terror on the breeze

If anything is a set piece, the Albert Hall sequence in The Man Who Knew Too Much is. Philip Kemp’s commentary for the Criterion DVD considers it Hitch’s first, although aficionados would probably consider the “knife” sound montage of Blackmail at the very least a rough sketch for what would come. Lucky you: The entire Albert Hall sequence is excerpted on the Criterion site.

A set piece benefits from a simple premise. Here, Jill’s child is being held hostage, which keeps her from informing the police of what little she knows about the plot. We know that during the concert an assassin will try to shoot a diplomat.

You can imagine Chandler asking: Why plug Ropa during a concert, with all those witnesses? Why not when the target is on the sidewalk, shot from a rooftop for easy escape? You can hear that bland replying murmur: Raaaymond, it’s only a moovie…

So we have some conditions for a set piece: a compact piece of action limited in time and space. But there’s also a strong time marker. Ramon the assassin is to wait for a dramatic pause in the score; it’s followed by a shattering choral outburst that will muffle the pistol shot. We’ve been given a rehearsal of the passage in a gramophone record, but since we don’t hear the whole piece then, we can’t predict exactly when the chorus will hit its peak.

Hitchcock magnifies this uncertainty by letting the piece, Arthur Benjamin’s Storm Clouds Cantata, play out in its entirety. Its combination of lyrical and dramatic passages blend into a stream of music that coincides with the emotional action onscreen. I suspect that the piece, composed specifically for the film, glances at the most celebrated new choral piece of the era, William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast (1931). It too has a charged dramatic pause followed by a tremendous choral blast: “Slain!” You can listen to it here, and you can hear some of the musical affinities at 27:11 and after.

So the self-contained quality of the sequence is enhanced by the unfolding soundtrack, as well as its “bookend” structure: Jill arrives at the Albert Hall/ Jill leaves. (Hitchcock was very fond of this coming-and-going bracketing; many scenes of The Birds are built out of this.) But to be a set piece we need virtuosity too, right?

As our Film Art essay indicates, Hitchcock structures the scene using nearly every technique in the silent-cinema playbook. We get dynamically accentuated compositions, crisp point-of-view editing, subjective vision (even blurring as Jill drifts into a panicky reverie), and suspenseful crosscutting back to the gang holding Bob and Betty prisoner. The techniques build to their own crescendo, with more and shorter shots of Jill, the orchestra players, and the curtain concealing Ramon. As the climax approaches, details of the players’ performance pass in a flash. As another layer, though, all these visual techniques are synchronized with the musical structure of the piece. Most obvious is the slow tracking shot back from Jill as the female soloist launches in:

There came a whispered terror on the breeze./ And the dark forest shook.

The text has always teased me, because in my early years of studying the film I couldn’t hear everything there. Now that the Storm Clouds Cantata has become a minor concert piece, we have a full version of the text. It’s the description of an especially ominous storm, one that drives birds away and makes trees tremble in fear. The only creature left, vulnerable to the gale, is a child:

Around whose head screaming/ The night-birds wheeled and shot away.

The orchestral and choral forces mount on the line that has always come through the sound mix:

All save the child—all save the child.

The line is ambiguous. Its literal sense is that all the creatures have fled the oncoming storm except the child (“all save the child”). But Hitchcock’s cutting and the film’s overall context leave it as an imperative: the child must be rescued. Thus the musical dynamics and the text stress, for us and presumably for Jill, that Betty’s safety depends on what she does.

Soon the cantata’s text finds another analog in the concert hall. The choir sings of the storm clouds finally breaking and “finding release.” That phrase, repeated with rising intensity, yields the dramatic pause and then the final outburst that is to cover Ramon’s pistol shot. But now we have to see this phrase as prophecy and comment: Jill’s scream during the pause is the release of her tightened anxiety. And of course the line slyly signals the release of the suspense built up through the whole sequence.

With Hitchcock, you always get more.

In all, the sequence becomes exactly what a set piece ought to be: compact, with sharp boundaries and a strongly profiled arc of interest, elaborated with a great variety of technical resources and a thrusting emotional impact. But is it too much of an independent sequence? One can imagine Chandler worrying that Hitch doesn’t care much about how to hook it up with everything else. Let’s see.

This scepter’d isle

There’s no doubt that a plot driven by set pieces can seem episodic, just a matter of pretty clothes clipped to a slender line. In action movies it’s a classic problem, which, say, Speed doesn’t fully solve but Die Hard does.

You can mask an episodic plot, though, through some stratagems. First, make your filler material charming. The Man Who Knew Too Much gives us comedy in the dentist office and in the Tabernacle, with Bob and Clive mumbling messages through hymnody. You can also whisk the audience from scene to scene so quickly that the viewer has to concentrate on local connections. This is one purpose of what I’ve called the hook, the transition that smoothly links the end of one scene with the beginning of the next. If you’ve got some plot holes, strengthen your hooks–especially those that hide your gaps.

The Man Who Knew Too Much has some nifty hooks. I especially like the way the fingers pointing to the bullet hole are followed by a shot of Ramon’s head: effect and cause neatly given by a straight cut. Then there’s the contrast of the fire in the fireplace dissolving to the skier pin, a sort of thermal hook. But probably the most memorable one is Betty’s line about Ramon’s brilliantined hair.

This hook is a motif as well, and recurring images or sounds like this can help knit together your movie. In Foreign Correspondent, we get hats and birds in various scenes. Here, as our Film Art essay indicates, teeth, the skier pin, sharpshooting, the cantata’s main theme, and other motifs weave through the overall structure of the film.

You can as well knit your big scenes together through certain narrative patterns, such as a trip or a search, both strategies that Hitchcock employs in many movies. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, Bob’s investigation of the gang follows the menu set out in Louis’ note: the sun emblem, Wapping, G. Barbour, and A. Hall. This serves as a sort of map for the middle act of the film. Once Bob has cracked the message, though, the film shifts into a new register. Jill, who has been waiting passively at home, takes over the role of protagonist. And her actions will fulfill another motif: that of interruption and distraction.

The film begins with Betty’s dog disrupting Louis’ ski jump. That’s an innocent accident, as is the moment when Jill nearly spoils Roman’s skeet shooting. But soon afterward Abbott’s chiming watch deliberately breaks Jill’s concentration, making her lose the shooting match. In effect the Albert Hall sequence offers payback: With her scream Jill not only disrupts the performance but spoils Ramon’s aim as Abbott had spoiled hers.

The Albert Hall sequence fits into the film in a less obvious way, one that plays along the thematic dualities that marble the movie. Throughout the film contrasts “Englishness” with “foreignness,” the latter split between allies (Louis, Ropa) and enemies. The Storm Cloud Cantata and what follows represent a sort of triumph of England over her adversaries.

At the St. Moritz resort, the Lawrence family is set off from Louis, their French friend, and two men: Abbott the German and Ramon the Latin. (He’s handily fudged; he has a Spanish name but calls the English “extraordinaire.” And his hair is greasy.) “Sworn enemies, eh?” Jill says half-humorously to Ramon before losing the skeet shoot. After Louis’ death Bob is at a loss in the hotel, unable to speak German or Italian, and distracted while Betty is kidnapped. The English aren’t at home in this world.

Once Bob and Jill have returned to London, they join the family friend Clive, a Wodehousian upper-class twit but gifted with loyalty and tenacity. Bob and Clive have learned from Gibson of the Foreign Office that the gang intends to assassinate the diplomat Ropa. They must tell what they know; the killing could prove as catastrophic as the assassination that triggered the war of 1914-1918. Yet Bob keeps mum. He might be enacting E. M. Forster’s dictum: “If I had to choose between betraying my friend and betraying my country, I hope I would have the guts to betray my country.”

The conflict between family love and civic duty is played out in the rest of the second act, when the men’s investigation takes them to a working-class neighborhood of Wapping. There, we learn that behind respectable English institutions—a dentist, eccentric religion—foreign elements lurk. Bob has solved Louis’ riddle, but at the cost of becoming another hostage. Bob and Betty re-meet, in a characteristically subdued stiff-upper-lip encounter that denies Abbott the tearful scene he expected. The dignity with which Bob conducts himself, asking about Betty’s dressing gown and her school grades while staring defiantly at the gang, leaves the others abashed.

Clive has escaped, though, and has managed to send Jill to the Albert Hall. That musical set piece initiates the film’s climax dramatically but also thematically. For one thing, Benjamin’s cantata reaffirms another bit of Englishness. A national choral tradition runs back to Purcell and Handel, was sharpened in Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and was revived in the early twentieth century by Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius and Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony. Hitchcock and screenwriter Charles Bennett could have used Bach or Beethoven, but the choice of this brooding, mildly modernistic piece reminiscent of Walton is a nice bit of propaganda for British musical culture of the interwar years.

More importantly, the concert sequence solves the film’s ideological problem: How to save the world without destroying your family? Jill’s impulsive scream doesn’t divulge what she and Bob know about the gang, but it does serve to derail the gang’s plan and save Ropa. And by leading the police to follow Ramon to the hideout, she in effect chooses to risk Betty and Bob for the capture of the gang. Here, perhaps, the sheer drive of the action muffles the significance of her choice; Chandler complains that Hitchcock tended to take refuge from plot problems in “wild chases.”

What follows, in the middle of some violence that remains shocking today, is a vigorous reassertion of Englishness. The vignettes during the siege display stalwart national virtues. A postman insists on making his rounds during the gunplay. An inspector swipes sweets and pauses for a cup of tea. The police reluctantly take up arms, only after several of their unarmed number are mowed down. Slipping into adjacent buildings, snipers move a piano while its fussy owner rescues his potted plant. And a cop who was slated to go off duty finds a warm mattress to die on. This unassuming valor, so different from Ramon’s petulant swagger and Abbott’s self-congratulatory sadism, will win out. The victory is announced by the pent-up crowd rushing jubilantly forward as the siege ends.

In any other movie the mother would have been huddling with the child and the man would grab a rifle to pick off his enemy on the roof. But making Jill the crack shot reasserts another quintessentially English image: the hunting, shooting, riding mistress of the estate. She gets her second chance to fire, bringing down Ramon when even the police sniper hesitates. It’s also a bit of guilty revenge for the death of Louis, whom Jill danced into the line of fire. Hitchcock, as usual, renders it elliptically: we see Jill grab the gun but not fire it. As she and Bob and Betty are reunited, the movie that began with the line, “Are you all right, sir?” ends with a mother reassuring her weeping daughter, “It’s all right.”

This, we might say, is how you integrate set pieces into your movie—narratively, stylistically, and thematically. Others would disagree with me, but nearly forty years of living with this film hasn’t made me change my mind. The Man Who Knew Too Much is Hitchcock’s first thoroughgoing masterpiece.

Thanks to Abbey Lustgarten, UW-Madison alum, for her excellent production job on the Criterion disc. Thanks also to Peter Becker and Casey Moore for coordinating the posting of our Film Art piece with this blog entry.

For more on Chandler and Hitchcock, see William Luhr, Raymond Chandler and Film (New York: Unger, 1982), 81-93. My quotation comes from Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. by Dorothy Gardiner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Books for Libraries Press, 1971), 132.

Hitchcock probably doesn’t deserve 100% of the credit for the Foreign Correspondent windmill scene; it was designed by the great William Cameron Menzies.

When I wrote the Film Art analysis back in the 1970s, Kristin hadn’t elaborated her ideas about how large-scale parts, or acts, can shape a film. Yet I think that the three parts that the analysis mentions constitute pretty well-articulated acts. The first part has as its turning point Bob’s realization that when Gibson traces Betty’s call, police will converge on Wapping and endanger her. So Bob and Clive set out to save her. That decision comes about twenty-six minutes into the movie. I’d mark the end of the second act with Abbott’s sending Ramon on his mission after playing the cantata recording; that comes at about fifty-three minutes into the film. At this point we know everything we need to know, so the premises can play out. The last act is shorter, as climaxes tend to be. The Albert Hall sequence and the final shootout and rescue take up the final twenty-three minutes, capped by a very brief epilogue of the reunited family. For more on act structure, see Kristin’s entry here, mine here, and my essay on action movies, as well as Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood and my The Way Hollywood Tells It.

A final note: Frank Vosper, who plays Ramon, was a well-known stage actor and playwright. His most famous play is Love from a Stranger (1936); the film version was released in 1937. Another successful Vosper play was the fantasy comedy Murder on the Second Floor (1929), in which a writer devises a play consisting of all the clichés of sensational mystery fiction. But the Vosper play that piques my curiosity most is his 1927 drama called—I’m not kidding—Spellbound.

See? With Hitchcock you always get more.

The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Annies to Oscars: this year’s animated features

Awards scene in The Pirates! Band of Misfits.

Kristin here:

On February 1, the Annie Awards were given out. These are the honors bestowed by the International Animated Film Society. Up for best animated feature were the five Oscar nominees in the same category–Brave, Frankenweenie, ParaNorman, The Pirates! Band of Misfits, and Wreck-It Ralph–plus three others–Hotel Transylvania, Rise of the Guardians, and The Rabbi’s Cat. Rather to my surprise, Wreck-It Ralph took the top honor.

This seems like a good occasion to follow up on some of my entries on animation posted here years ago and to present some comments on the five Oscar nominees.

Mainstream fare

Remember when entertainment journalists were suggesting that there were getting to be too many big-studio animated features in the market each year? Remember when supposedly there just wasn’t that much demand and that cartoons were starting to eat into each other’s box-office takings? No? I do, partly because back on January 23, 2007, I blogged on the subject. I said at the time, “The ‘too many toons’ issue looks to me like a tempest in a teapot.”

For one thing, animated features were actually doing very well at the box-office:

In 2006, the ten highest domestic box-office grossers included four CGI hits: Cars, #2, Ice Age: The Meltdown, #7, Happy Feet, #8, and Over the Hedge, #10. On the worldwide chart, these four films rank high as well: Ice Age: The Meltdown, #3, Cars, #5, Happy Feet, #10, and Over the Hedge, #11. In the domestic market, 6 other toons make the top 100. So, 4 out of 10 toons are in the top ten, while 6 out of 90 live-action films make that short-list. I’m no math whiz, but that looks like 40% versus 6.6% to me.

Since 2006, animated features have increased in number, as witnessed by the fact that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences upped the number of nominees in that Oscar category from three to five for the 2010 awards. Actually, the rules are more complicated than that:

All submissions sent to the Academy will be screened by the Animated Feature Film Award Screening Committee(s). After the screenings, the committee(s) will vote by secret ballot to nominate from 2 to 5 motion pictures for this award. In any year in which 8 to 12 animated features are released in Los Angeles County, either 2 or 3 motion pictures may be nominated. In any year in which 13 to 15 films are released, a maximum of 4 motion pictures may be nominated. In any year in which 16 or more animated features are released, a maximum of 5 motion pictures may be nominated.

The 2010 and 2012 Oscars each had five nominees in the category, while for 2011 there were again only three. This year there are again five, and it seems likely that this will continue to be the case.

In 2012all but one Hollywood studio had at least one animated feature among its five top-grossing films. So much for such films crowding each other out of the market. Totals below are worldwide and include the grosses only to December 31:

Sony: Hotel Transylvania, #4 ($313.2 million, still in release; $324.3 million as of Feb. 3)

Warner Bros.: none

Fox: Ice Age: Continental Drift, #1 ($897.3 million)

Disney: Brave, #2 ($538.3 Million)

Disney: Wreck-It Ralph, #3 ($283.6 million, still in release; $376.6 million as of Feb. 3)

Universal: Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax, #3 ($349.6 million)

Paramount: Madagascar 3: Europe’s Most Wanted, #1 ($743.3 million)

Paramount: Rise of the Guardians, #3 ($261.2 million, still in release; $297.8 million as of February 3)

The first six of these films were in the 20 top-grossing American films of 2012; Rise of the Guardians was #30.

(These figures are from “Studio figures hit sky high” by Ian Sandwell, in the January 25, 2013 issue of Screen International. Unfortunately the charts of studio hits aren’t in the online version of the article.)

People no longer suggest that there are too many animated films. In fact, they’re a predictable mainstay of the studios, partly because they have proven themselves capable of generating lucrative franchises, just like those big action-packed CGI fantasy and sci-fi films. People are now suggesting that maybe there are too many of those in the market, cannibalizing each other’s grosses.

The Return of Handmade Animation

In recent years, some members of the industry, the punditry, and the general audience have complained that small, independent films and even foreign fare have elbowed their way into the live-action categories. The best-picture category was reportedly increased from five titles to up to ten slots specifically to make sure that some blockbusters would make the list and draw in a larger audience for the televised Oscar ceremony. Still, The Hurt Locker beating Avatar has been pointed to innumerable times in order to claim that the Academy voters are out of touch with the broad popular audience’s tastes.

Wait a minute. The box-office charts are themselves in touch with the broad audience’s tastes as expressed by tickets sold. The Oscars are supposed to be about honoring the year’s best films, not the biggest earners, aren’t they? This year’s best-picture nominees again reflect the Academy’s willingness to cast a somewhat wide net, with a very low-budget film (Beasts of the Southern Wild) and a foreign one (Amour) sitting cheek-by-jowl with hits like Django Unchained and Les Misérables. Despite the expansion in the number of nominees, the really big hits that also garnered critical acclaim, notably The Dark Knight Rises and Skyfall, didn’t make the list.

The same phenomenon has crept into the animated-feature list. Only two of the nominees come from those six that were in the top-twenty box-office hits: Brave and Wreck-It Ralph. The other three were all box-office disappointments to some extent: Frankenweenie, ParaNorman, and The Pirates! Band of Misfits. (Or, to call it by its funnier British release title: The Pirates! In an Adventure with Scientists!)

These three were all created via stop-motion animation. In contrast, all the hits in the list above were CGI, as was the mid-level grosser, Rise of the Guardians.

This is not to say that the three stop-motion film completely avoided computer effects. As Iain Blair pointed out recently in Variety, they made use of new technologies. ParaNorman worked innovatively with 3D laser printing to create huge numbers of slightly different faces for the puppets. (More on that below)

The Pirates! mainly used puppets, but there digital effects done in-house, creating water, fire, smoke, fog, and so on, including the whale. Basically, Aardman’s using special effects in a puppet film the way live-action films use them. (A 3D printer was used to create different mouths to achieve variety of expression, a technique somewhat comparable to that used for ParaNorman.)

While Frankenweenie used puppets and miniature sets, it also included digital technology, like scenes done against greenscreens with clouds and background vistas added as effects:

So why were the three films made mostly by hand all less successful than the year’s big CGI toons? I would have thought that most people can’t tell the difference, and those who can don’t care. The characters in most CGI animation are basically imitations of puppets, and good stop-motion animation can look nearly as smooth as the digital equivalent. I doubt that audiences are consciously avoiding puppet-based films.

On the basis of these three films, one might almost believe that stop-motion films are become the art-house fare of the animated sector of the industry. I don’t think that’s the case, though. It’s probably just an odd coincidence likely to be limited to 2012. If anything, I suspect that the dominance of the list of nominees by stop-motion films reflects the Academy’s animation wing’s appreciation of the work and skill that goes into such painstaking work. They clearly took note of films that used this technique, including The Pirates!, which was released way back in April. Which is not to say that CGI-based animation involves less work or skill. It just isn’t quite so vivid and obvious.

The Pirates! was unquestionably a failure in the USA. This harks back to my entry kvetching that Flushed Away was sunk by DreamWorks, for lack of trying to turn Aardman into a recognizable brand like Pixar. Now Sony has done the same with The Pirates! In 2011, Sony also released Arthur Christmas to poor business; it’s a hilarious and charming film, well worth a watch. I suspect The Pirates! has little chance for an Oscar, especially without the magical Nick Park name. (Park has won five Oscars on six nominations. He couldn’t win six, since Creature Comforts and A Grand Day Out were nominated opposite each other!) But suppose The Pirates! did win. It would join Wallace & Gromit in The Curse of the Were-Rabbit, that other DreamWorks “flop” that won Best Animated Feature. It made 71% of its worldwide gross outside North America.