TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed

Monday | January 23, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

DB here:

As the final credits rolled, a man behind me blurted out, “I don’t get it.” He’s not alone. Kristin and some acquaintances have told me that they found parts of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy hard to follow. Several critics, while praising the film (and doubtless getting more of it than that guy), have warned viewers to pay close attention. Roger Ebert said:

I enjoyed the film’s look and feel, the perfectly modulated performances, and the whole tawdry world of spy and counterspy, which must be among the world’s most dispiriting occupations. But I became increasingly aware that I didn’t always follow all the allusions and connections.

Some of the film’s admirers advise us not to worry much about the intricate storyline. Michael Phillips remarks:

This is one of the finest achievements of the year, and while it’s easy to lose your way in the labyrinth, I don’t think “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” is most interesting for its narrative pretzels. Rather, it’s about what this sort of life does to the average human soul.

Even if I weren’t a le Carré fan, I’d be fascinated by a film that can succeed both critically and financially and still leave its audience puzzled about its plot.

Critics of popular filmmaking claim that our movies cater to simple minds, but we actually find a lot of successful films, from Groundhog Day and Pulp Fiction to Inception, that are complex in intriguing ways. I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It that since the 1960s one current of filmmaking has explored narrative strategies that were minor, even unheard-of, options in earlier times.

I’m not ready to join Steven Johnson in suggesting that audiences have become smarter. In certain respects older films are more demanding than contemporary ones. I’d rather say that new conventions are in force, aimed at certain sectors of the audience who are willing to put forth the effort. Ambitious filmmakers may find new ways to fulfill these conventions, balancing novelty with intelligibility. This is the path, I think, that the makers of Tinker Tailor took, and it didn’t prevent the film from earning $17 million at the US box office.

The film’s ’70s patina isn’t off-putting. The filmmakers offer deliberately grainy imagery, enveloped in hazes of rain and cigarette smoke. The palette, except for Ricki Tarr’s idyll with Irina, is grey, brown, and beige. Scenes are shot with long lenses, rack-focus, and drifting tracking shots. Zooms and push-ins are interrupted by cutaways. The result is an Altmanesque look, but more disciplined. It’s not the visual style, then, but those the narrative pretzels—another reminder of late ‘60s and early ‘70s storytelling—that attract my notice today.

So I persist: What makes the movie hard to grasp? If we can get a sense of this, we might get to know Tinker Tailor more intimately, while also producing some ideas about how mainstream films work generally. To attempt an answer, I have to go into detail. I won’t be supplying a plot synopsis, but the Wikipedia entry is reasonably comprehensive. I’ll be looking less at the story and more at the storytelling. Still, don’t read further if you haven’t seen the film. In the tradecraft jargon of blogging: There are spoilers ahead.

Breaking up the blocks

One factor contributing to the film’s difficulties, as many reviewers have pointed out, is that it’s adapted from a big and complex book. But it isn’t just the size of the original novel that poses problems. It’s the way the plot is constructed and the story is narrated.

The plot of the novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (published 1974; the commas aren’t in the adaptations) consists mostly of blocks of flashbacks. The action starts long after Control has died and his old staff, including George Smiley, has retired. The novel’s first scenes show Jim Prideaux’s arrival at the boy’s school, seen from the perspective of Bill Roach, his shy confidant. We don’t yet know how Jim connects to Smiley, who after a dinner with a gossipy acquaintance, is summoned to investigate the prospect of a mole in the Circus’s top echelon.

Smiley’s investigation involves questioning witnesses like Connie Sachs, but more often it involves “burrowing,” working patiently through the files that Control had studied. Le Carré presents what Smiley gleans from the files as flashbacks, and interwoven with those are Smiley’s reflections on the key personnel and their power struggles. Institutional memory and Smiley’s rueful recollections tie together the ambush of Jim Prideaux and the vein of top-secret information code-named Witchcraft.

Respecting the novel’s construction would demand a cascade of long tales framed by Smiley’s step-by-step pursuit. Arthur Hopcraft’s screenplay for the seven-installment 1979 BBC series took the simpler option of starting with a scene that is presented very late in the novel, during Jim’s revelatory confession to Smiley. The TV series opens with Control summoning Jim and sending him off to Czechoslovakia. Jim is shot and Control is cast out. Clarifying the string of events this way, and giving us a decent action scene early on, has its cost: Smiley doesn’t enter the series for twenty-three minutes.

Since Hopcraft and director John Irwin had hours at their disposal, the scenes could stretch and breathe, and they retain the somewhat chunky, modular quality of the novel. But a two-hour film couldn’t handle the book’s plot so spaciously. What did the team of Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan do? Straughan explains:

The adaptation process differs from book to book, but in the case of “Tinker Tailor,” it involved a kind of mosaic work. The structure of the novel was broken into pieces. Some long sequences would remain intact – Peter Guillam stealing the files from the Circus, for example – but in other cases we would take a line or event from one place in the narrative and move it elsewhere, shifting the fragments around endlessly until it felt right. The goal was to create a new version of the narrative which would bear a close family resemblance to the source material, but have its own cinematic personality. The really difficult part was not fitting the plot into two hours but doing it without losing the tone; to give the film the same autumnal, melancholy pace, and to give the script air and silence.

The most obvious instance of this fragmentation is the repetition of the ambush of Bill Prideaux in the Budapest café. In keeping with current norms of storytelling, this scene is replayed at crucial points, each time giving us a bit more information relevant to the scenes of testimony around it.

Repetition is a luxury that can’t be overindulged in adapting a hefty novel. To spare time for the pace, the air, and the silences the filmmakers want to include, they had to be more concise in their presentation of plot. They had to chop le Carré’s big narrative blocks into bits.

When we view a mosaic we can step back to see how the composition blends all the fragments. But we have to experience a movie bit by bit. A film, we might say, is a moving mosaic, and we are usually standing very close to it. Just as important, a mosaic, made out of gaps, leaves it to us to grasp how the parts fit together—to make our mind jump the gaps.

Unconventionally conventional

How does Tinker Tailor fit the pieces together? In general, the film adheres to common conventions of modern storytelling but then subtracts one or two layers of redundancy. The little gaps created make the film seem roundabout today, when rather linear and explicit narration is the norm.

Start with a simple case. Like many modern spy films, Tinker Tailor initiates a shift to another locale by a long-shot framing, often from on high. Here’s an example from The Bourne Ultimatum.

It’s triply redundant: We see a city landscape including the Arc de Triomphe; we’re told it’s Paris; and we’re told it’s Paris, France (not Paris, Maine). Compare the parallel shot from Tinker Tailor.

Not exactly a difficult leap—who doesn’t know that the Eiffel Tower is in Paris (France)?—but it’s a little less explicit. Earlier instances are more laconic. When we’re taken to Budapest and Istanbul, probably not as immediately recognizable to many in the audience as Paris, we get a cityscape with only one mention in the dialogue to tag the setting, and no captions. Least explicit of all are the shots picking out the Circus in London.

Another film would have typed out, “MI6 HQ,” but we’re left to infer that behind this façade the Secret Intelligence Service does its work. So the convention of the exterior establishing shot is respected but made a little less redundant.

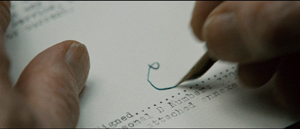

Consider as well the introduction of the Circus’s decision makers. Another film might have started with Smiley and followed him from his office into the briefing room. Instead, he’s introduced as one of several men, then as an out-of-focus figure alongside Control. And even Control could have been more clearly identified. He signs his resignation with what could become an emblem of the film’s stingy approach to storytelling.

Just as truculent is the process by which Lacon is led to summon Smiley. First Lacon gets a warning call from the field agent Ricki Tarr. So far, so conventional. But Tomas Alfredson has staged things so that Tarr is seen at a distance, turned from us, and blocked by a phone booth. Who is this guy? We must get all our information solely from his voice, not his facial expression.

Soon after Peter Guillam has entered the Circus, he gets a call. Most directors would have cut away to the caller, or at least let us hear what Peter is hearing. But we’re denied that information. On the soundtrack, we hear only a muffled, “It’s Oliver…ringing…” It’s Lacon, but you know that only if you know his first name is Oliver, and we’re teased by hearing almost nothing of what he’s saying. We know even less than Guillam, and this suppressive narration is characteristic of Alfredson’s handling of genre conventions.

Next we see Smiley at home, watching television. There’s a knock at the door. Cut to a car driving, Peter at the wheel and Smiley in the back seat. Smiley is silent, and Peter offers his regrets: “I was sorry to hear about Control, Mr. Smiley.” Earlier we’ve been given one shot of the dead Control in the hospital. So much for his backstory.

Finally, as the car pulls up at Lacon’s house, the fragments combine into an intelligible sequence when Peter says, “He said Tarr called him from a phone box.” Retrospectively, we can buckle the sequence up as a familiar genre action: The hero is called back to the battle by his chief.

Another convention, one that goes far back, is the dialogue hook. This is a bit of speech that ends one scene and links directly to the next one. Tarr calls Lacon and names Guillam as his supervisor. Cut to Guillam crossing the street and entering the Circus. Later, Smiley suggests that he and Guillam investigate Control’s flat. Cut to them entering it.

Dialogue hooks, as I’ve traced out here, are enormously helpful in guiding us through the plot. But sometimes Tinker Tailor works more obliquely. In one scene Peter reads of the staff who were sacked following Control’s fall. One is Jerry Westerby, whom we’ll meet a long while later, and the other is Connie Sachs. Cut to a train station, with Smiley buying a ticket to Oxford. It’s a hidden hook: most films would include in the earlier scene a line such as, “Connie Sachs, who’s now in Oxford.” Again, a conventional device is roughened a bit, made slightly more difficult. And sometimes the hook is visual and disruptive, as when a shot of Jim, bleeding in the Budapest arcade, is followed by a shot of the boy Bill Roach looking out a window at Jim’s arrival, as if he’s also looking down at his future teacher.

The BBC series was broadcast in weekly episodes, so recapping and backtracking in each installment helped viewers remember. At intervals we see Smiley bringing Peter up to date and briefing Lacon on current discoveries. The film flagrantly refuses to provide this conventional help. As Ebert notes:

More ordinary spy movies provide helpful scenes in which characters brief each other as a device to keep the audience oriented. I have every confidence that in this film, every piece of information is there and flawlessly meshes, but I can’t say so for sure. . . .

What replaces the standard briefing scenes? Some rather elliptical passages. There are the nodes in which Smiley reflects on the evidence. We get a shot of him staring, followed by a cascade of imagery as his mind plays with possible suspects.

Linked to the briefing scene is another convention, the board or wall on which all the suspects are diagrammatically arranged. In our visit to Control’s apartment we might have seen pictures of Bill Haydon, Roy Bland, Toby Esterhase, and Percy Alleline laid out in a rectangle, with the sinister silhouette of Karla up top, and dotted lines connecting them. Yet Control, the bedraggled chainsmoker, could hardly be so tidy. Instead, the film gives us something more in character and more oblique: a litter of chessmen, each with a picture taped awkwardly on. Eventually Karla is revealed as another piece (the powerful white Queen). On his own, Smiley joins in Control’s conceit and tapes a picture of the new suspect Polyakov to a bishop.

Le Carré’s novel tied the suspects together with a verbal emblem, based on the child’s nursery rhyme. It linked the boy’s school to the Circus. But the film doesn’t introduce the tinker-tailor motif until very late. Instead the chess pieces visualize the multiple-choice problem, but in a ragged, haphazard way that suggests that perhaps Control really was, as Jim Prideaux suspects, going mad. More broadly, the imagery (with the briefing room as a gridded checkerboard) reminds us that spying, known for decades as The Great Game, is now a global chess match. It pits Karla against Smiley—whom Control has identified as the black Queen.

George the Obscure

Again and again, the script and Alfredson’s direction invoke a convention only to make it more difficult to grasp. The central examples involve Ann, the faithless wife. She isn’t just treated elliptically; she’s suppressed. Instead of showing her flirting with Bill at the Christmas party, we see only the back of her head and Bill looking past Smiley’s shoulder.

In a later flashback to the party, Smiley looks out the window and sees Ann in the garden. Another film would have shown us who’s clutching her in the foliage, but this film leaves it to us.

Of course many viewers will know Ann’s partner is Bill, but another film would have confirmed this more explicitly. Instead another standard scene is handled in a glancing way. More generally, Ann’s phantom presence not only makes her seem remote, like a princess in a tower, but sets her off against the blonde Irina, the maiden to be rescued in Ricki Tarr’s story. Thanks to the camera and a compact mirror, Irina’s face gets the caresses another film would devote to Ann.

Irina, beautiful and sincere, holds the film’s major secret, the one that initiates Smiley’s investigation. She harks back to the blonde mother who is in the line of fire in the Budapest arcade, and that shooting prefigures Irina’s fate.

The crowning achievement in the film’s laconic way with conventions is the climax in the safe house. Smiley has arranged for Ricki to send a message that will force Karla’s mole to make an emergency appointment with his connection Polyakov. There Smiley, Guillam, and Mandel will record the meeting and capture the double agent. In the BBC series, this climax runs over eight minutes, built out of crosscutting and suspenseful waiting. Smiley and Guillam burst in together and a quick pan shot reveals Bill as the culprit.

The film uses suspense and crosscutting as well, but the sequence consumes only six minutes. More important, by switching our attachment away from Smiley at the crucial moment, it conceals his entry to Bill and Polyakov. Instead we follow Guillam separately into the house, up the stairs, and to the parlor. There he confronts the aftermath of what might have been a heroic confrontation. Climax is treated as anticlimax.

Jim Emerson, in a nicely honed piece, suggests that we think of such passages as not so much elliptical as economical. I want to have it both ways. The scenes are economical because they fulfill familiar narrative and genre-based functions: We know how to fill them in. Yet they’re also elliptical because they hold back information, sometimes a little and sometimes a lot. A mosaic can show us familiar people and things, but it also asks us to make extra effort to see the pattern emerge. The tesserae fit, but the bumps and grooves between them are palpable.

It may be that art films have always tended to be self-consciously wrought genre films. L’Avventura: A mystery-melodrama. Blow-Up: A detective story. Drive: the thinking person’s action film. If so, then Tinker Tailor is the smart Bourne movie. Creative novelty needs a familiar base to play off. Movies come from other movies, and originality can take a tradition, even a popular one, as a point of departure for innovation.

Best watcher in the unit

Once plot gaps have alerted us, we should expect things to proceed through hints. Granted, there are hints that can’t be picked up unless you know the novel. For instance, the film doesn’t stress the fact, emphasized in the novel, that Bill is an amateur painter and the canvas he brings Ann on the fateful night is one of his own works. It’s the picture that Smiley is studying at the end of the credits sequence, as if the film’s two primary antagonists are already squaring off.

But, sticking just to the hints we can pick up without the novel, the film is fairly rich. It invites multiple viewings, as many movies do nowadays, in order to catch the undercurrents or the things that flash by too quickly on the first pass. (If we want to find more, we can buy the DVD.) I can’t pretend to exhaust the possibilities, but here are some that strike me.

Go back to those chessmen. As we’ve seen, the two antagonists, Karla and Smiley, are made parallel as the rival Queens. Three suspects are assigned to innocuous pieces: Percy as the white Rook, Toby as the black Knight, and Roy as the black King (although that assignment might be a narrative feint, hinting that Roy’s the traitor). But Bill is the white Bishop, and in retrospect we can see the fact that Smiley makes the Moscow agent Polyakov a black Bishop is a pointer to Bill’s guilt—and maybe a suggestion that, as Bill will say, George knew all along.

Or take the homosexual element. One question that comes up in conversation after the movie is whether Bill and Jim were lovers. It’s treated as a possibility in the original novel and becomes stronger as the film proceeds, especially after Bill—in a moment of privileged information for the audience—pockets a picture of the two friends embracing and laughing. By the end, in the final flashback of the Christmas party, Bill rouses the loner Jim and flashes him a smile; but the brandy glass he floats away with seems intended for Ann. Bill’s bisexuality is explicit in the epilogue when, in the compound, he asks Smiley to pay off both a girl and a boy. More than a hint, as well, is the tear that dribbles down Jim’s cheek as he executes his friend. (Bill’s wound, rhyming with Jim’s perforated back in Budapest, again recalls the slain mother in the arcade.)

Similarly ambivalent is the presentation of the dapper Peter Guillam. He’s introduced turning his head to watch a cute young lady pass. Later he’s revealed to be gay: for security reasons, he has to break up with his partner. In retrospect, we can see the shot when Bill and Peter eye the new clerk Belinda as presenting two double agents, each one passing as a lady-killer.

More minor touches hint at the sexual undercurrent. Bill on the phone: “And I said you may fuck me but you still have to call me sir in the morning.” It takes a quick eye to spot another manifestation of the motif. Polyakov, posing as a cultural attaché, writes articles for a bilingual magazine. After Connie has told her tale, there’s an insert—an excerpt from Connie’s memorabilia, or perhaps only a memory of Smiley’s—of an article signed by Polyakov, which says of the Russian Ballet corps:

To see them only in a narrative ballet would be to know them incompletely. The programme shows a perfect cross section of their accomplishments.

They can dazzle us with a technique that seems to defy the laws of gravity but that is not merely acrobatic because it is truly gay in expression.

Like the dancers, Bill and Jim are both athletes and acrobats, powerful and graceful. I can’t prove this implication was intended by filmmakers, but by chance or design, it’s a fragment that fits.

Or take the Christmas party. There the tune, “The Second-Best Secret Agent in the World” ramifies outward to several second-besters: that night Jim is Bill’s second-best lover, Smiley is Ann’s second-best lover, and Smiley is the agent outwitted, at that point, by Bill. Another hint: At the height of the evening, the USSR anthem is sung ironically by the Circus staff, while Bill, an undercover Soviet, is off in the garden. Not to mention that as Control signs his retirement papers, he asserts: “A man should know when to leave the party.”

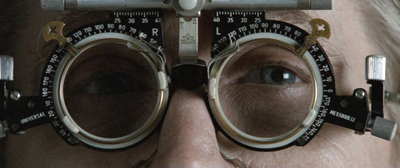

Above all are the eyeglasses. Promoted in the film’s publicity (when Oldman found them, he found the character), they become associated with seeing things as they are. The old hornrims seem to be something of a shield; Smiley pushes them back into place after he sees Bill with Ann. But once Smiley has gotten his new, more powerful pair after leaving the Circus, he uses them as an instrument of scrutiny. They enlarge his vision eerily; often they’re lit and in focus when his eyes aren’t. And they hide his eyes from others.

Although he bears Bill’s name, the podgy boy Roach is a closer parallel to Smiley. For him and for George, spectacles are a sign of wary vigilance. Jim praises Roach: “Best watcher in the unit, I’ll bet. As long’s he’s got his specs on, aye?” The motif may come from a passage in the novel that is recast for the film. Bill tells Smiley that Karla had worried that Smiley would catch him.

Karla said you were good—the one we had to worry about. But you do have a blind spot. And if I was known to be Ann’s lover, you wouldn’t be able to see me straight. And he was right—up to a point.

But those were the old glasses, and Smiley was a more vulnerable man then.

Saint George?

The novel is based, as most people know, on the revelation back in 1963 that a cadre at the center of the British Secret Intelligence Service was in the pay of Moscow. Kim Philby was the central figure, surrounded by Donald Maclean, Guy Burgess, and “the fourth man” identified later as art historian Anthony Blunt. In a scathing introduction to a 1981 book on the conspiracy, le Carré diagnoses the scandal as symptomatic of an endemic weakness in Britain’s ruling class. (Yes, he uses that phrase, which no American politician dares to utter.)

Was he not born and trained into the Establishment? Effortlessly he copied its attitudes, caught its diffident stammer, its hesitant arrogance; effortlessly he took his place in its nameless hegemony. . . . The SIS quite clearly identified class with loyalty.

He might be describing Bill Haydon:

Philby, an aggressive, upper-class enemy, was of our blood and hunted with our pack; to the very end he expected and received the indulgence owing to his moderation, good breeding, and boyish, flirtatious charm.

Worse, the agency that was pledged to protect Britain had insulated itself from reality, somehow seeing in an American-promoted anti-Communism a small rebirth of the Raj.

Whatever went on the big world outside, England’s flower would be cherished. “The Empire may be crumbling; but within our secret elite, the clean-limbed tradition of English power would survive.”

Le Carré’s lacerating remarks remind us that he might be our only major popular novelist who has held uncompromisingly critical positions on international affairs, including the Iraq war and the growth of American militarism and corporate power.

But the polemicist isn’t identical with the novelist. Tinker, Tailor provides a far more ambivalent picture of betrayal. Le Carré the polemicist has created in Haydon a perfect embodiment of what he despised about British Intelligence and the class system that feeds it. The parallel world of the boys’ school evokes the origins of the corrosive ethic that led to Bill’s treachery.

Yet the novelist spares his traitor the worst. For one thing, Peter Guillam, who idolized Haydon, can’t summon up condemnation.

Despite his banked-up anger at the moment of breaking into the room, it required an act of will on his own part—and quite a violent one, at that—to regard Bill Haydon with much other than affection. Perhaps, as Bill would say, he had finally grown up.

Smiley, who has every reason to hate Bill, is at a loss. He mulls over how he should judge the man who has done such monstrous things. As a friend worthy of respect who stood by his convictions? As a committed thirties intellectual? As a romantic elitist clouded by ideology? As an esthete who elevated his distaste for Philistinism to a political principle? As a superficial man in the grip of a compulsion to betray?

Smiley shrugged it all aside, distrustful as ever of the standard shapes of human motive. He settled instead for a picture of one of those wooden Russian dolls that open up, revealing one person inside the other, and another inside him. Of all men living, only Karla had seen the last little doll inside Bill Haydon.

In the book, Smiley’s uncertainty about Bill leads him to hope for a reconciliation with Ann. For him, unlike Bill and Karla, love isn’t an illusion or cover story. In the TV series, for all his triumph over the Alleline cadre and Karla’s mole, he returns to Ann and her chiding: “Poor George, life’s such a puzzle to you, isn’t it?” But the film gives us a different Smiley, and it interprets his reward quite differently.

We can approach the problem through performance. The TV series makes Smiley a stern schoolmaster, keeping his own counsel but voluble, thanks to the fluting of that Guinness voice. His facial expressions work a narrow range, but are very nuanced within that compass. Here is Guinness shifting, minutely, from polite approval to a steely comprehension while his oblivious informant chatters on.

By contrast, as every critic has noted, Oldman’s Smiley is virtually blank for most of the film. His frog-mouth, half-open or clamped shut, remains impassive. Guinness lets us into Smiley’s mind as he interrogates his targets, but Oldman’s most marked reactions are brow-wrinkling concentration and puzzlement. The high point, George’s discovery of Ann’s disloyalty, elicits only a gasp and a gape (and a pushing up of the glasses). As usual, even that reaction is muffled a bit, this time by the profile angle.

Similarly, everything conspires to make George obscure. Framing, setting, and lighting put him far from us, wrap him in shadows, let reflections on his spectacles block his eyes.

Guinness’s Smiley isn’t hard to read, once you tune to his high, narrow frequency, but Oldman’s Smiley is a sphinx. And it seems to me that this poker face works toward a new conception of Smiley’s role. The elliptical narration conspires with Oldman’s performance to create a conclusion that is far more harsh than what we find in the book or the series.

Early on, the film shows us George shamed. Control, forced to resign, announces that Smiley will leave with him. It evidently comes as a surprise to Smiley, who—in a moment that many critics have rightly praised—turns his head slightly and after a beat and a blink accepts with a tiny nod. For the rest of the film, George’s head-turns will be his principal signal of surprise, uncertainty, or sudden realization. (It’s even contagious: his adversaries execute the same gesture, and even Guillam catches the habit.) Smiley and Control stalk out of the Circus as exiles and part on the sidewalk without a word and Smiley comes home to an empty house.

Summoned back into service, he launches his investigation. In a key scene in the novel, the series, and the film, he confides to Peter his meeting with Karla long ago, when he tried to persuade the Russian to switch sides. The meeting disclosed a faultline in Karla’s character (“He’s a fanatic, and the fanatic is always concealing a secret doubt”), but it revealed Smiley’s weak spot too. Asking Karla to think of his wife, Smiley betrayed his worries about Ann. Karla retained the cigarette lighter that Ann had given Smiley, a token of Smiley’s fear of losing her. Years later, cuckolded by Bill at Karla’s behest, Smiley adds sexual shame to professional disgrace.

There’s a certain mystery about how the movie Smiley cracks the case. In the book and the series, there’s a lot more evidence about the mole than we get in the film. In the turning-point sequence, subjective montages lead to a burst of images and recurrent lines from Ricki: “Everything the Circus thinks is gold is shit.” Smiley is convinced there really is a mole, chiefly because of Jim Prideaux’s testimony, but we have to reason on trust: the reappearance of Karla and the murder of Irina before Jim’s eyes connect the mission to Budapest with the Witchcraft files.

The TV Smiley reveals his reasoning in a very lengthy interrogation of Toby Esterhase. Over fifteen minutes, Smiley builds a plausible case and forces Toby, to avoid suspicion that he’s the mole, to reveal the location of the safe house. Lacon is briefed offscreen, and George is given permission to set the trap.

But the film Smiley acts very differently. He confronts Lacon and the Minister and bluntly announces that there’s a mole, that Karla controls him, and that SIS has been feeding the Americans trivia and lies. He offers no evidence. The officials are shaken solely by Smiley’s uncharacteristic vehemence. His mocking conviction smashes their resistance and they give him permission to go after Toby.

With Toby, Smiley again uses brute force. No reasoning, no evidence, just the bald threat of throwing Toby onto the plane and shipping him back over the Curtain. Cringing and whining, Toby gives up the safe house’s address, and George can proceed to set the trap. And this comes after the moment when Smiley, knowing full well that Irina is dead, promises Ricki to do “his utmost” to retrieve her. Guinness’s Smiley makes the same promise, but in his gentleness we sense a man pained by his bad faith. Oldman’s Smiley is as guarded as ever.

I submit that the Smiley of the film, once he has overpowered his superiors, can’t spare a moment to brood over Haydon’s personality. He proceeds largely from a vindictive, controlled aggression. Lacon fired him, Alleline despised him, Toby insulted him, and Bill betrayed his marriage. Behind that severe blankness, I think, burns a desire to avenge Control, and to get a bit of his own back. When that mask slips, in talking with Lacon and the Minister, he’s nearly gloating.

The film, in sum, seems to me to offer a legitimate reinterpretation of the Smiley character. His fierce anger is rather close to le Carré’s attitude toward Kim Philby: The man may have been an enigma, but he was still despicable. The difference is that while le Carré can castigate the man in print, George can pay his traitor back. In this dirty game, he can finally checkmate Karla.

Was it worth it? The novel leaves you wondering. In its final pages, Smiley moves toward uncertain reconciliation with Ann. Jim’s future is more hopeful: after killing Haydon, he returns to the school and rebuilds his relation with young Bill, the other “new boy.” The only hope, it seems, lies in human relationships, not in a frigid bureaucracy.

But in the film, Jim harshly breaks off with the boy, and Smiley triumphs. To the music of “Beyond the Sea,” the losers—Ricki, Connie, Bill—are glimpsed. But Smiley, having kept his own counsel throughout, is a winner. There’s little sense here of le Carré’s distaste for the institution that nourished Bill and his breed. Smiley reenters the Circus, in a smart new suit and topcoat, striding to the top floor and taking Control’s seat, to offscreen applause. (I grant you there’s a bit of irony in that sound effect.) And how else to explain the vignette before that when, after the death of Bill Haydon, Smiley comes home to find Ann there? The sailor of the song has returned to the woman who has been waiting for him. Beggarman has gotten what Ricki saw in Irina: Treasure.

In preparing this entry, I was much helped by James Schamus and Khaliah Neal of Focus Films. Thanks also to Jeff Smith and Kristin for conversations about the movie.

For more on the film’s artistic approach, see Jean Oppenheimer, “A Mole in the Ministry,” American Cinematographer 92, 12 (December 2011), 28-34 (apparently not available online). After explaining that DP Hoyte van Hoytema and Alfredson sought “a grainy, somewhat colorless look,” the article reports van Hoytema saying that the zoom shots were modeled on 1970s ones: “When I look at films from the ‘70s, I like the fact that the zooms are so functional and solid. They have a beginning and an end.”

Le Carré’s introduction may be found in Bruce Page, David Leitch, and Phillip Knightley’s The Philby Conspiracy (Ballantine, 1981). Valuable studies of le Carré’s work include Peter Lewis, John le Carré (Ungar, 1985) and Michael Denning, Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1987). In an earlier entry I offer an appreciation of the second book in the Karla trilogy, The Honourable Schoolboy.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: John le Carré in right foreground.

PS 1 March: In a followup entry, I explore other aspects of Tinker Tailor.