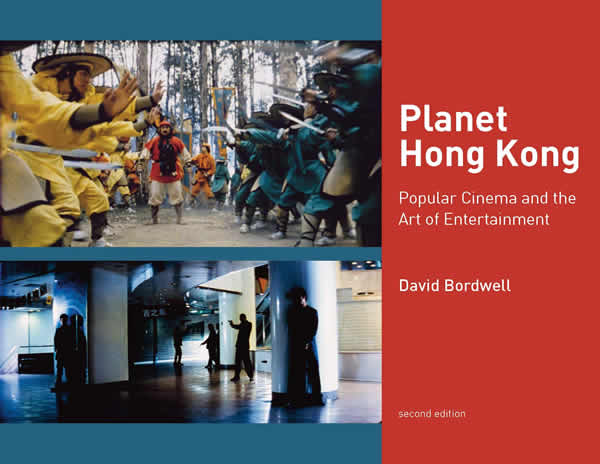

Planet Hong Kong

by David Bordwell

299-page PDF, 11 × 8.5 inches. 441 illustrations.

READ THE PDF

Planet Hong Kong was published in 2000. At some point in 2008, Harvard University Press took the book out of print, a decision I learned about in spring of 2009. The story is here. After finishing other writing commitments, I settled down to revising the book in August of 2010.

The new edition has replaced nearly all the original black-and-white illustrations with color ones, and has added several dozen new stills. The new parts of the text amount to some 40,000 words, with an updated list of further reading.

I could have recast PHK top to bottom, but I wasn’t convinced that I could come up something as pointed as the original. The text has been corrected, of course, and patches have been recast for greater clarity. My argument has been enhanced by a few more examples, film sequences I referred to in passing but could not illustrate because I couldn’t find a print or couldn’t include color images. The chief updating is a series of sections added to the back end.

So here is what the book now looks like.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

Chapter 5 surveys the industry, with emphasis on filmmakers’ craft traditions (how stories are planned, scenes are cut, and so on). The interlude that follows takes Tsui Hark as an instance of a director who creatively reworked such traditions. Chapters 6 and 7 go into the most detail about the aesthetics of Hong Kong film, surveying the dynamics of genre, the star system, visual style, and plot construction. Between these two chapters is sandwiched an interlude devoted to Wong Jing, the most disreputable major filmmaker in the territory. The longest chapter, the eighth, explores the distinctive aesthetic of action pictures, from martial arts to contemporary crime movies. The interlude that follows discusses three outstanding directors in the martial-arts tradition: Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, and King Hu. The final chapter of the original book considers how the premises of popular cinema can be adapted to create “art films.” The principal, but not sole, example is the work of Wong Kar-wai. The original book concluded with an analysis of Chungking Express.

The new material in this edition starts with a chapter on changes in the film industry since 1997. That’s followed by an interlude focusing on the Infernal Affairs trilogy, which was the source for The Departed. The next chapter considers how the artistic trends surveyed in the first edition have changed over the last ten years or so. While discussing developments in genre, storytelling, technology, and style, the chapter includes sections on Stephen Chow (particularly Shaolin Soccer and Kung-Fu Hustle), Wong Kar-wai (In the Mood for Love and 2046), and Johnnie To Kei-fung. The final interlude is a more in-depth discussion of To’s crime films and their relation to the indigenous action-movie tradition. At the very end is a new bibliography and endnote citations.

Readers not drawn to Hong Kong cinema might nonetheless find my more general arguments of interest. For example, I suggest that Hong Kong shows us how important regional and diasporan networks are in creating and maintaining a film culture. To the claim that films reflect their societies, I reply that Hong Kong films suggest a different way to think about such a dynamic, using the model of cultural conversation. Readers interested in fandom should find something intriguing in the story of how cultists around the world helped establish Hong Kong film as a cool thing in the early 1990s. I also argue against the tendency in film studies to assume that when a film tradition doesn’t follow the rules of classical plot construction it must be based on something called “spectacle.” I suggest instead that we need to study principles of episodic plotting, which are probably quite common in popular art generally. In these and other areas, I wanted to use this cinema as a way into thinking about popular moviemaking as a whole.

For other information about this edition, you can visit my blog entry here. To give you something of the flavor of the book, here is the original Preface.

Preface (2000)

Some of the best books on Hong Kong start with the author flying in to the old Kai Tak airport, the jumbo jet nearly scraping the rooftops of Kowloon City before wheeling around sharply to land. (An Australian pilot is supposed to have described the trip as eight hours of sheer boredom followed by eight minutes of sheer terror.) This magnificent arrival is impressed in my memory too, but the real thrill came later, when on a sultry March night I wandered along Nathan Road, staring up at a forest of towering neon. Columns of Chinese characters several stories high, blazing crimson or gold, stretched alongside more familiar names: Toshiba in silver and red, an aqua OK signaling karaoke.

Drifting with the crowd, I sauntered among old men walking gravely with hands clasped behind their back, executive men and women hollering into bricklike cell phones, matrons strolling four and five abreast, children trotting along in shorts and suspenders, slender boys in white shirts and blue trousers, girls with dyed auburn hair and knapsack purses strapped to their backs. There were plenty of tourists: big German and Australian couples appraised cameras and Discmen in shop windows while American students rummaged through a cart of bootleg CDs. The noise was overwhelming: buses screeched to discharge their passengers, people shouted amiably at one another. Occasionally a man would try to pull me out of the commo tion. “Copy watch?” “Sir! Where are you from, sir? Are you thinking of a suit?”

To cross from Nathan Road to Salisbury Road, the street that runs along the harbor, is to leave most of the turmoil behind. Among the cool columns of the Cultural Centre, at the tip of the peninsula, people shift gears. The Centre is less popular for its museums and theaters, I suspect, than for its tranquillity; later I would discover that every day families fresh from the Marriage Registry gather in front of a fountain there for photographs, the bride dazzling in a white gown and perhaps clutching a Snoopy hand bag. That first night, though, I was behind the Centre staring at the skyline of Hong Kong Island across the harbor.

As with all legendary views, the postcard version is too cramped. Here were skyscrapers spread out carefully, as if designed to lead your eye from the spiky profile of the Bank of China to the Neo-Deco Central Plaza and soon enough to the gigantic glowing signs for Citizen and San Miguel. Behind these, misty green hills rose to the Peak. Everything was reflected in the bay, not in perfect outline but in thousands of red, blue, and gold highlights broken by the ferries and barges that crisscrossed your line of sight. This view may be Hong Kong’s greatest work of art. I picked up smells too—the pungent “fragrant harbor” that gave the colony its name, the odor of floor wax from the lobby of the Centre. On the esplanade, couples loi tered and tourists snapped photos of the great contrivance shining across the water.

What had brought me here? In the fall of 1973, soon after I had started teaching at the University of Wisconsin, I went to see Five Fingers of Death paired with The Chinese Connection in the dilapidated Majestic Theatre. Not long afterward I saw Enter the Dragon. These movies shook me up. A few years later in Richmond, Virginia, I saw Bruce Lee’s Game of Death, a film of such surpassing oddness that I screened it for my film theory class. At the same time, during trips to Europe, I caught up with King Hu’s exhilarating masterworks.

During the 1980s, while writing about Hollywood cinema and film theory and the films of Yasujiro Ozu, I occasionally checked in on Hong Kong cinema. I caught a Jackie Chan here, a Tsui Hark there, and cable TV yielded up oddities like Shaolin Kung-Fu Mystagogue. The films appealed to me as “pure cinema,” popular fare that, like American Westerns and gangster movies of the 1930s, seemed to have an intuitive understanding of the kinetics of movies. Over these years, my old friend Tony Rayns saw to it that I was sent the annual catalogues of the Hong Kong International Film Festival, and so I came to learn something of this cinema’s history.

In the early 1990s I dived in, not least because these movies aroused my students’ passion in a way that I had not seen for a long time. I began booking Hong Kong films for my courses, subscribing to the fanzines, picking up videotapes and laserdiscs. Soon I was convinced that this was a popular cinema of great vigor. When I gained a semester’s leave in the spring of 1995, I decided that it was time to visit the Festival.

Through the Festival I met Li Cheuk-to, Athena Tsui, Stephen Teo, Shu Kei, Michael Campi, and many others who have become firm friends. I also saw a selection of recent films, a retrospective of postwar movies, and a sample of what was playing at the moment. At the first Hong Kong Critics Society award ceremony I met Ann Hui, Wong Kar-wai, and other filmmakers. I managed to slip into the Hong Kong Film Awards, where I snapped photos and got autographs of stars and directors I admired. During my three weeks’ stay I lived in a fan’s paradise. I even ate at Chungking Mansions.

I became addicted to visiting Hong Kong. Sometime after the third trip, at the urgings of my wife, Kristin Thompson, and my friend Noël Carroll, I decided to write a book. It was a difficult decision, not only because I don’t speak or read Chinese. For one thing, there is already a lot written about this cinema, and there is going to be a lot more. Web pages are sprouting at this moment. Further, I have seen only about three hundred seventy Hong Kong movies. (If you think that’s a lot, you are not yet a hardcore fan.) Still, perhaps out of stubborn naïveté, I thought that I had something original to say about the movies produced in this tiny corner of Asia. I thought that I could explore this cinema not as an expression of local society, nor as part of the history of Chinese culture, but as an example of how popular cinema can produce movies that are beautiful.

What follows, then, is an essayistic attempt to understand the interplay of art and entertainment in one popular cinema. Because I have felt free to choose what interests me, I have left to one side, for example, the Cantonese Opera films, the social realist tradition of the 1950s, the musicals and comedies and melodramas of the 1960s, and the films of Sadean violence. I have also not touched upon the work of certain directors whose work is un available in good film prints. Selective though it is, I hope that Planet Hong Kong will serve as both an introduction to Hong Kong film and an exploration of matters not addressed elsewhere—industry background, production practices, and above all filmic structure and style.

The book also delineates Hong Kong’s significance for international popular filmmaking. How did cheap movies made in a distant outpost of the British Empire achieve broad international appeal, while European filmmakers bemoan their inability to reach even their own national audiences? How did Hong Kong filmmakers manage to create artful movies within the framework of modern entertainment? What can these films tell us about storytelling in a mass medium—its history and craft, its design features and emotional effects? Such questions inevitably lead us back to the unique achievements of Hong Kong cinema and to an assessment of the delights and the shortcomings of the films themselves.

Some might say that the book risks imposing an outsider’s values on a cinema that exists in and through unique cultural circumstances. But despite many claims to the contrary nowadays, there are more commonalities than differences across human cultures. Whatever a film’s country of origin, it is likely to tap into widespread physical, social, and psychological predispositions. For instance, audiences can intuitively understand many facial expressions of emotion. Many practices—such as acquiring shelter and caring for children—are similar in different societies. Cultures also converge historically, because when they come into contact, borrowing is inevitable. The traditions of Hollywood and Japanese cinema have powerfully influenced Hong Kong film.

Popular cinema, moreover, is deliberately designed to cross cultural boundaries. Reliance on pictures and music rather than on words, appeal to widely-felt emotions, easily learned conventions of style and story, and redundancy at many levels all help films travel outside their immediate context. That audiences all over the world enjoy Hong Kong movies dramatically illustrates the transcultural power of popular cinema.

Today the Asian financial crisis has driven the crowds from Nathan Road, and the Hong Kong film industry is struggling to survive. This book portrays a vibrant moment in the history of popular film and shows how it participates in a vigorous tradition of mass entertainment. That tradition is nearly as old as the century that is now ending, and it is becoming, day by day, more powerful in every land. It is time we understood it better. These films can help us to do so. Along the way they can show us a splendid time.

|

|