Archive for the 'Screenwriting' Category

Manual labors

The Tin Star (1957).

DB here:

Type “screenplay writing” into Amazon and you’ll get over 6000 hits. Some of those books will be biographies of writers or screenplays of released films. But there’s still a huge number of DIY books with titles like How to Write a Movie in 21 Days and Writing Screenplays That Sell. A lot of people are apparently only one manual away from a finished script.

Screenplay manuals trigger suspicion. Can it really be that easy? Wouldn’t this be a paradise for grifters? A successful writer would hardly share trade secrets, so most of these books would be written by losers and wannabes. And if you read enough of the manuals, you’ll see the inevitable repetition of banalities. Make your protagonist “relatable.” Keep the conflicts going. Try for a twist.

Reading through them can be mind-numbing, but if you’re interested in how filmmakers tell stories, sometimes they can open up your thinking. Or so I’ll argue.

DIY scripting

The tide of manuals rose during the 1910s, when the emerging American studio system was seeking talent. The tide subsided between the 1930s and the 1960s, when screenwriting was contract labor in that system. But as filmmaking turned “independent,” ambitious people outside the industry could break in with an original script. Manuals, most famously Syd Field’s Screenplay (1979), began to pop up, and the market for how-to books expanded. Field’s book remains in vigorous circulation today, among many competitors.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

If your research touches on matters of style, you may find it illuminating to study the way practitioners pick solutions to practical problems. Which is to say that the manuals can point us toward norms. Norms are, I’ve argued, like a menu of more and less preferred options for treating the material. We developed this angle of inquiry in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, and now it seems well-established that the manuals can sometimes point us toward tacit norms of construction or visual style. For examples of how this can work, see Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood, my The Way Hollywood Tells It, and Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir. Many of our blog entries have also explored these paths. With screenplay manuals, we just have to be particularly careful to distinguish valuable data from bilge–which means checking the manual’s precept against many films.

And we shouldn’t expect the manuals or professional journals to identify every normalized device. For example, screenwriters now love to start scenes with friends greeting one another with “Hey” and “Hey,” but I doubt that there’s an explicit decision to avoid “Hi.” Similarly, I’ve never found anyone writing in the classic era who mentions the common Hollywood device of the double plot, with one line of action devoted to a goal-oriented activity and another, interdependent one devoted to heterosexual romance. Even the rather elaborate 180-degree classical editing system wasn’t apparently spelled out anywhere; it was learned by imitation and reinforced because it was economical and efficient. People can learn and follow rules that are simply taken for granted as “the way we do things.”

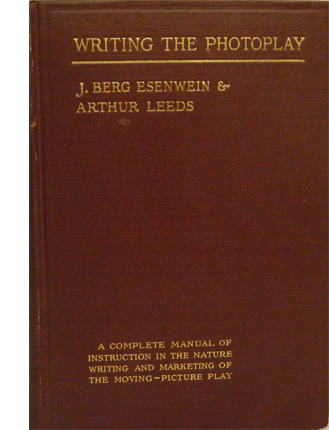

I think my soft spot for the manuals owes a good deal to my long-term affection for one item I saw in a 1913 guide. J. Berg Esinwein and Arthur Leeds’ Writing the Photoplay contains a lot of hints about standard practices of the period, but one of their diagrams changed my basic attitude about silent film technique.

The cinematic stage

In the late 1990s I became interested in the norms of scene staging in early film. I assumed that filmmakers had to call attention to story action without benefit of cutting to closer views, so I tried itemizing in a straightforward way the staging choices that could guide the viewer’s eye.

Many of the choices could be called “theatrical.” Lighting and setting could emphasize an actor’s gesture or facial expression. Performance factors operated as well, especially since actors were typically facing the viewer. Filmmakers’ reliance on these cues seemed to confirm the standard impression that early film was less “cinematic” than what came later.

Yet there were purely pictorial factors in play as well–notably, the placement of figures in the overall image. Composition of the frame, as in painting (and theatre) played a crucial role in guiding our attention.

There was something else. I was fascinated, for reasons sketched here, with the depth that many scenes in “tableau cinema” displayed. Here’s a quick example from Alfred Machin’s Le Diamant noir (1913). The entire film is available from the Belgian Cinematek.

The young secretary Luc is accused of stealing the missing diamond. He protests his innocence, but the accusation will force him to leave the country.

All the cues I’ve mentioned are at work here: centered figure placement, frontally facing characters, attention-grabbing gesture, favorable setting (the rear doorway and curtains highlight Luc’s arrival), and so on. In addition, a tunnel of information bores through the frame, leading from the distance and culminating in action in the foreground.

But this tunnel couldn’t fairly be considered “theatrical,” since if the action were played on a stage, not all viewers would have the optimal view presented in the shot. Most of the audience simply couldn’t see this alignment of players. Theatrical staging tends to be lateral and fairly shallow, so that people sitting in different seats can all see the scene. A good part of planning a stage production is calculating sightlines. But in film, there’s only one sightline, that of the camera lens.

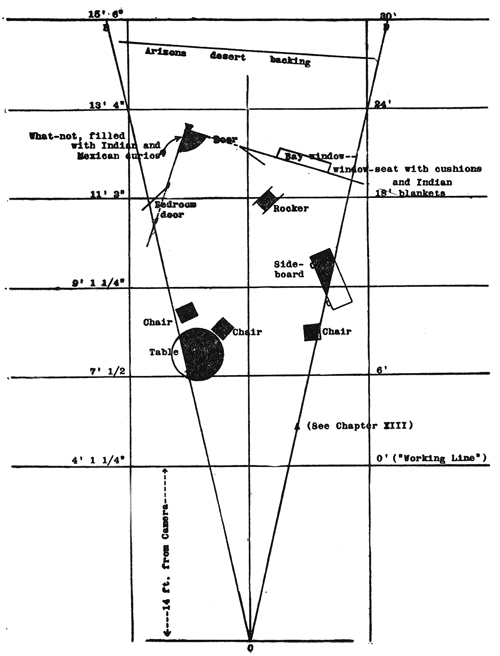

We tend to see film space as cubical, a room with a missing fourth wall. Actually, the playing space–what Esenwein and Leeds call “the photoplay stage”–is a tapering pyramid whose point touches the lens. Because the film image captures an optical projection, the space is narrow but deep. The authors provide a diagram of a scene to explain. (For the sake of clarity, I’ve removed some of their annotations; the full version is on p. 160 of their book.) The effect is of wedge shape that carves into what would be the wide space of a theatre scene.

In 1910s cinema, the camera lens (at point 0) is assumed to be some distance from the “working line,” the layer of maximal attention. For some filmmakers this line was nine or eleven feet from the camera, rather than the 14 feet assumed here. The rest of the space falls away in the distance, and depending on the lens and lighting used, these areas can be in more or less sharp focus. Filmmakers of the period often marked out the pyramid on the studio floor so that actors would know when they were out of shot.

This diagram makes explicit many of our taken-for-granted notions about film space. Someone moving closer to the camera gets larger, of course; but the figure also blocks out more and more of the background as the pyramid narrows. An actor’s forward movement on the stage inevitably takes up a small part of the overall area, but in cinema forward-thrusting action can dominate the frame.

Just as important, the fixity of the lens makes it possible to choreograph actors with a precision impossible in theatre. Luc’s confrontation with his employer in my second frame gives him pride of place, but once he’s slumped at the foreground desk, he can move his head and clear the central zone for us to see a servant waiting in the distance. In tableau cinema, staging isn’t just “blocking.” It’s blocking and revealing, a constant flow of information presented through shifting arrays of figures. I provide several examples in the lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

My heightened awareness of the visual pyramid made me more sensitive to staging in all periods of cinema. We might think that after the tableau cinema period, when filmmakers became more dependent on editing, their reliance on the “photoplay stage” vanished. But of course every shot, close or distant, presents us with the visual pyramid, and some filmmakers relied upon it to provide the graduated layers of space in an edited sequence. Specifically, the “deep focus” that became a favored technique of 1940s cinema around the world would seem a modernization of the principles of the 1910s recognition of wedge-shaped playing space. Here’s an outrageous example from Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941), shot by Gregg Toland after Citizen Kane.

Less punchy imagery than this suggest that the skills of 1910s staging were never really lost. Another passage from Ball of Fire brings Professor Potts to the foreground in a way reminiscent of Machin’s film. Of course it helps when Gary Cooper is the tallest galoot in the scene.

Cinema’s visual pyramid becomes almost sadistic at the climax of Anthony Mann’s Tin Star (1957). The young sheriff stops a lynching by shaming the town bully. The bully responds as you’d expect, but not in the sort of shot you’d expect.

Mann’s earlier films had experimented with foregrounds thrusting out at the viewer, but this sequence carries the idea to a limit. The actor collapses against the camera, inadvertently proving how lines of cinematic sight converge at the lens–that is, at our viewpoint. Try doing this on the stage!

This entry is more a piece of intellectual autobiography than anything else. I doubt many other people were opened up to the intricacies of staging thanks to a diagram in an old book. I mean it just as an example of how reading manuals can set you thinking about the expressive possibilities of film, and taking you in directions that you couldn’t predict.

More recently, in writing Perplexing Plots, I poked into manuals for would-be fiction writers, an area that literary historians seem to have neglected. These manuals yielded a lot of principles of what people thought went into good storytelling. In particular, I found that while Henry James and Joseph Conrad were making arguments about viewpoint and chronology, so too were people writing how-to manuals. The books indicated a new awareness of these techniques among writers aiming at mass audiences.

Terry Bailey surveys and analyzes early manuals in “Normatizing the silent drama: Photoplay manuals of the 1910s and early 1920s,” Journal of Screenwriting 5, 2 (Jun 2014), p. 209 – 224. For a comprehensive overview, see Steven Price, A History of the Screenplay.

The main argument here is developed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

Ball of Fire (1941).

Another degree of Kevin Bacon: David Koepp’s YOU SHOULD HAVE LEFT

You Should Have Left (2020).

DB here:

Friend of The Blog David Koepp has written and directed a new movie that is premiering online this week. You Should Have Left is in the vein of his earlier, locked-in exercises in psychological horror, Stir of Echoes (1999) and Secret Window (2004). Both a haunted-house story and a disquieting probe into male anxiety, it’s another strong entry from Blumhouse–for me, the most interesting film company out there.

Critics sometimes say that Clint Eastwood is the last really “classical” director working now. Actually, in my view almost everybody remains a classical director to some extent. Still, the term holds especially good here. David’s handling of this scary chamber drama reminds me of the unfussy precision of Polanski in The Ghost Writer. In fact, one shot recalls the famous partial view of Ruth Gordon in Rosemary’s Baby. (Doorways are always good spots for tricky framing.)

More generally, David isn’t ashamed to invoke all the creepy conventions of the Old Dark House, suitably updated. He lays out the house’s space tidily and then disorients us about exactly where we just were. I think the Dreyer of Vampyr would appreciate the ways in which this PoMo mansion becomes a maze.

Of the other films David has directed, I’m especially fond of Ghost Town (2008) and Premium Rush (2012). And of course his scripts for Jurassic Park, War of the Worlds, and other megapix are models of construction. I also admire his superbly crafted screenplays for Panic Room (another claustrophobic exercise), for the still-too-little-appreciated The Paper, and for the bravura item that is Carlito’s Way.

You Should Have Left is currently available on demand from many cable and streaming services and will eventually show up as part of the offerings of NBC Universal/Peacock.

For more on David’s work, go here, which will lead you elsewhere.

You Should Have Left (2020).

Accident forgiveness: J.J. Murphy’s REWRITING INDIE CINEMA

Maidstone (1970).

DB here:

Did you ever want to beat up Norman Mailer? The impulse must have flitted through the minds of many who paged through his work, saw him on TV, or encountered him swaying pugnaciously at a party. Rip Torn took the opportunity. One day in 1968, he whacked Mailer with a hammer and started to strangle him. As the distinguished author tried to bite off Torn’s ear, Mailer’s wife leaped into the fray and his children shrieked with fear.

This scene, totally unscripted, appears in Mailer’s film Maidstone (1970) and opens J. J. Murphy’s new book Rewriting Indie Cinema: Improvisation, Psychodrama, and the Screenplay. Nothing could better prepare us for his exploration of the traditions–and sometimes jarring consequences–of spontaneous performance in modern American movies.

I couldn’t have predicted that J. J., who was in grad school with Kristin and me, would turn to research. He began as part of the Structural Film movement, achieving wide renown with Print Generation (1974) and (my personal favorite) Sky Blue Water Light Sign (1972). After he was hired here at Wisconsin, he rejuvenated our production program and went on to make independent features: The Night Belongs to the Police (1982), Terminal Disorder (1983), Frame of Mind (1985), and Horicon (1994).

I couldn’t have predicted that J. J., who was in grad school with Kristin and me, would turn to research. He began as part of the Structural Film movement, achieving wide renown with Print Generation (1974) and (my personal favorite) Sky Blue Water Light Sign (1972). After he was hired here at Wisconsin, he rejuvenated our production program and went on to make independent features: The Night Belongs to the Police (1982), Terminal Disorder (1983), Frame of Mind (1985), and Horicon (1994).

At the same time, he was teaching both production and screenwriting. His books reflect his deepening interest in the creative process of making a film outside the Hollywood system. His initial study, Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work (2007), focused on the principles of screenplay construction that emerged with US indie cinema. Then, in The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol (2012), J. J. offered the most complete analysis of this superb body of work. In the process, he opened up a new vein of exploration. The idea of psychodrama proved an exciting way of explaining the fascinating, awkward performances in films like Kitchen (1965), Vinyl (1965), and Bike Boy (1967).

Now the concept of psychodrama gets full play in an ambitious account of the changing role of improvisation in off-Hollywood cinema. What happens, J, J. asks, when filmmakers give up the screenplay? How do they construct a story, define characters, build performances? Rewriting Indie Cinema sweeps from the 1950s to recent films like The Rider and The Florida Project. By looking for alternatives to the fully prepared screenplay, it posits a fresh way of thinking about American film artistry.

Human life isn’t necessarily well-written

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968).

To start off, J. J. proposes that we think of improvisation in a systematic way. Of course, the concept can be treated broadly. Even Hitchcock, we learn from Bill Krohn, improvised on the set much more than he claimed. But J. J. suggests that improvisation can be considered as a basic creative concept, a founding choice for art-making.

In the 1950s, many American artists began to embrace chance, accident, and personal expression. Abstract Expressionism, bebop, the Judson Dance Theater, Robert Frank’s snapshot aesthetic, and other tendencies valued spontaneity as both authentic self-expression and a challenge to conformist culture. The idea of spontaneity was carried into cinema by Jonas Mekas and fueled what became the New American Cinema of John Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke, and other filmmakers.

But the idea had deeper sources in another trend that J. J. painstakingly brings to light. The Austrian theater director Jacob L. Moreno developed in the 1920s what he called the Theatre of Spontaneity (Das Stegreiftheater). Performances consisted of purely improvised dialogue. When Moreno emigrated to America, he founded “Impromptu Theatre” in the same vein. His 1931 performance at Carnegie Hall was greeted by the New York Times with some disdain:

The first play, like the ones that followed, turned out to be a dab of dialogue uneasily rendered by its hapless players. . . . It became more and more evident that heavy boredom, rather than “forms, moods and visions,” were [sic] the product of the actors. Demanding wit above all else, the Moreno players lacked that essential as fully as the premeditation upon which they frown so heartily. The legitimate theatre, it can be reported this morning, is just about where it was.

Of course improvisation had already proven its worth in vaudeville and in jazz and other musical idioms. Today versions of Moreno’s “spontaneous theatre” flourish in comedy clubs.

Before coming to America, Moreno had discovered that improvisation had therapeautic functions as well. When a couple enacted the frustrations of their marriage, the audience was moved and Moreno was convinced that this “psychodrama” harbored artistic possibilities. Moreno’s wife Zerka called psychodrama “a form of improvisational theatre of your own life.”

J. J. shows Moreno’s pervasive influence on the postwar American scene. Psychodrama became one trend in social psychology, used to help prisoners, narcotics addicts, and even business executives. Woody Allen, Arthur Miller, and other artists were aware of Moreno’s work as well.

Drawing on Moreno but recasting him for film-related purposes, J. J. proposes a spectrum of improvisational options. There’s the completely improvised, ad-lib option, seen in Maidstone and much of Warhol’s work. Here the performers just make it up as they go, though with minimal framing of a situation. Then there’s the possibility of “planned” improvisation, in which there’s a story outline and more or less pre-set scenes. Sean Baker’s Tangerine (2015), for example, was made from a seven-page treatment that included only a couple of lines of dialogue. Then there’s the “rehearsed” option, in which the players collaborate to prepare the scenes and develop the characters, workshop fashion. In production the performers mostly stick to the “script” they’ve created. J. J. points to the films of Cassavetes as a clear case.

Any given film can mix these options, so that some scenes are planned roughly while others are purely ad-lib. And a filmmaker can explore the spectrum across several films, as Joe Swanberg has done.

Where does psychodrama come in? J. J. shows that any of the three points on the improvisation spectrum–pure, planned, and rehearsed–can yield performances that are based in the actual mental states and personal histories of the players. In our Cinematheque screening devoted to his book, Abel Ferrara’s Dangerous Game (1993) served as an example. Harvey Keitel invested his character, an intransigent film director, with the still simmering emotions he felt after his breakup with Lorraine Bracco. Meanwhile Ferrara set up scenes that would provoke Madonna, playing Keitel’s actress, to break character and reveal her immediate responses.

Ferrara wanted to attack Madonna’s celebrity image, and J. J. reads the aftermath to a rape scene in the film being made as projecting the star’s own stammering outrage at having been exploited.

Throughout the book, when improvisation becomes psychodrama, fiction moves closer to documentary. The last chapter examines how certain films considered documentaries, like Robert Greene’s Actress (2014) and James Solomon’s The Witness (2015), cross over into psychodrama from the other side, so to speak.

A detailed study of William Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968) shows how Greaves used psychodramatic techniques to create an even more complicated film-within-a-film than Dangerous Game. Two characters, Freddie and Alice, are played by five different pairs of actors, with all their scenes recorded by a bevy of camera and sound staff.

Greaves also incorporates self-criticism. When crew members object to the script, another participant remarks: “Human life isn’t necessarily well-written, you know.”

Given these conceptual tools, J. J. goes on to trace the production methods employed by a wide range of filmmakers, from Morris Engel in The Little Fugitive (1953) and Cassavetes in Shadows (1959) to Mumblecore and after. Through a mixture of film analysis and background research, he brings to light a vast variety of creative options that can bypass fully-scripted cinema.

Rewriting the unwritten

Paranoid Park (2007).

J. J.’s survey of production methods is embedded in a new historical argument about the shape of off-Hollywood filmmaking. The New American Cinema of the 1950s, which Mekas called “plotless cinema,” was wedded to a sense of realism. But it operated within limits. Cassavetes serves as a benchmark: “I believe in improvising on the basis of the written work and not on undisciplined creativity.” By balancing the planned with the impromptu, his films allowed for the actors to surprise one another. At the same time, Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason (1967) showed how psychodrama could pass easily into documentary, exemplifying Erving Goffman’s theory that everyone is playing theatrical roles in everyday life.

This open approach to screenwriting and screen acting was explored by many filmmakers in the 1960s and a little after: not only the well-known Warhol and Mailer but also Kent Mackenzie, Barbara Loden, William Greaves, and Charles Burnett. J. J. examines all this work in admirable detail. I was especially happy to see that he includes Jonas Mekas’ The Brig (1964), the harrowing film that showed me, in my undergrad days, what the New American Cinema could do in filming a play.

By the time Ferrara made Dangerous Game, most independent filmmaking had moved away from improvisation toward more tightly scripted expression. J.J. traces the institutional pressures operating here. The Sundance Film Festival and PBS’s American Playhouse favored fully-planned projects compatible with the Hollywood standard. The Sundance Institute, launched in 1981, explicitly aimed to correct what was considered the two faults of independent production: screenplays and performances.

The success of polished work like sex, lies, and videotape (1989) and Pulp Fiction (1994) created new norms for American indie cinema. Director-screenwriters like Soderbergh, Tarantino, David Lynch, Hal Hartley, Todd Haynes, the Coens, and Todd Solondz were models for younger filmmakers. As J. J. points out, their screenplays were often published as part of the marketing of the films. Framing the new trend as dominated by the screenplay helped me understand why Bryan Singer, Doug Liman, Karyn Kusama, and other indie filmmakers who came up in the wake of this generation moved so easily to mainstream genres and big-budget projects.

But history plays strange tricks. In the 2000s, filmmakers who felt constrained by the demands of tight scripting began to try something else. J. J. pays special attention to Gus Van Sant, who after proving his commercial craft, made some films with varying degrees of improvisation: Gerry (2002), Elephant (2003), Last Days (2005), and Paranoid Park (2007). Some of the Mumblecore directors relied on screenplays, but the prolific Joe Swanberg adopted a free-form approach, to which J. J. devotes a chapter.

J. J. goes on to survey the work of Sean Baker, the Safdie brothers, Ronald Bronstein, and other directors who have revived the New American Cinema’s impulses in the digital age. He concludes:

Digital technology in effect, democratized the medium, allowing young filmmakers to revive cinematic realism precisely at a time when indie cinema was at risk of losing its identity. In the new century, the use of improvisation and psychodrama provided a sense of continuity with indie cinema’s roots.

J. J. retired from UW–Madison at the end of 2018, and last Saturday night he was honored at our annual screening of student projects. He has been a constant force for good in our department, and we owe him more than we can say. Among those debts is this outstanding contribution to US film studies.

The book’s title carries a double meaning. American independent cinema has been, at crucial periods, “rewritten” by filmmakers who relied on spontaneity rather than a cast-iron screenplay. At the same time, J. J.’s panoramic research in effect rewrites that history. I’m sure that other researchers will build on his wide-ranging arguments, which put the creativity of artists–filmmakers, performers–at the center of our concerns.

J. J.’s books join a cascade of recent work by other colleagues here at Wisconsin. This blog has highlighted Jeff Smith’s Film Criticism, the Cold War and the Blacklist (2014), Kelley Conway’s Agnès Varda (2015), Lea Jacobs’ Film Rhythm after Sound (2015), Lea’s and Ben Brewster’s enhanced e-book of Theatre to Cinema (2016), and Maria Belodubrovskya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin (2018).

P.S. 9 May 2018: Thanks to Adrian Martin for correction of a misspelled name!

Kelley Conway awards J. J. Murphy a gilded Badger at the Communication Arts Showcase, 4 May 2019.

How LA LA LAND is made

La La Land (2016).

The formal method is fundamentally simple. It’s the return to craft (masterstvo).

Viktor Shkovsky, 1923

DB here:

Not how it was made. We’ll get “The Making of La La Land” as a DVD bonus, and there are already behind-the-scenes promos.

No, this is about how it is made.

On this site, we mostly practice a criticism of enthusiasm. We write about what we like, or at least about films that intrigue us from the standpoint of history or aesthetics. Sometimes, what interests us intersects with a current controversy. Take La La Land.

Some of my cinephile friends disapprove of it. It swipes too much, they say, from classic studio musicals and the work of Demy, and it doesn’t live up to either model. But tastes change. I remember when the classic musicals that we venerate were considered fluff, and I recall how Demy’s films, especially Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, were held at arm’s length by many of my 60s pals. “He tries too hard,” a friend remarked. Some say that about Chazelle, and perhaps in a few decades La La Land will be remembered fondly.

In any case, I’m not aiming to denounce this ambitious, agreeable film. I’m more interested in asking how La La Land accords with the craft of studio musicals and Demy’s efforts. I’m also interested in tracing its affinity with a third tradition of song-and-dance: the Broadway show.

Along all three dimensions, I hope to take Shklovsky’s advice and ask about craft. La La Land is both derivative and original. Actually, most movies are, though in various proportions.

The song plot

If we want to understand how film form and style work, we can’t neglect the nuts and bolts of moviemaking. In trying to achieve particular effects, filmmakers have created craft traditions, favored options bounded by loose limits. Mostly these traditions grow up intuitively, as solutions that just feel right. In any case, behind the cluster of preferred practices we can often find principles of design and execution that can be made explicit.

A lot of what Kristin and I have been doing since the 1970s consists of trying to bring to the surface filmmakers’ underlying habits and conventions. Those help shape how viewers respond to films. We aren’t maniacs for systematization—art can’t be utterly systematized—but as analysts we want to discern patterns of story and style, what earlier entries have called schemas. And as historians we want to understand how patterns of story and style get passed down from earlier films, and passed around among contemporaries.

For example, some narrative schemas of American studio cinema are what I aim to lay bare in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. Without invoking the big guns of theory, I try to point out how craft traditions of plotting and narration got recast in those crucial years. A recent entry hereabouts tries to show the legacy of those years surfacing in current releases, La La Land included.

Other researchers work along these lines, and not just in film. Art historians have been doing this sort of research for a long time, as have musicologists. A more recent example in the domain of theatre aesthetics is Jack Viertel’s exhilarating book The Secret Life of the American Musical. Its subtitle, How Broadway Shows Are Built, is a throwback (inadvertent, I suppose) to Shklovsky’s essay “How Don Quixote Is Made.” The impulse is the same: to x-ray an art work, to reveal some fundamental principles of construction, while also doing justice to its revisions of inherited traditions.

Other researchers work along these lines, and not just in film. Art historians have been doing this sort of research for a long time, as have musicologists. A more recent example in the domain of theatre aesthetics is Jack Viertel’s exhilarating book The Secret Life of the American Musical. Its subtitle, How Broadway Shows Are Built, is a throwback (inadvertent, I suppose) to Shklovsky’s essay “How Don Quixote Is Made.” The impulse is the same: to x-ray an art work, to reveal some fundamental principles of construction, while also doing justice to its revisions of inherited traditions.

What Viertel brings to the table is the “song plot,” a sequence of musical numbers that has become conventional in Broadway shows. Often, of course, many numbers enhance the dramatic action, but sometimes they’re inserted for a change of mood or a burst of energy. The song plot both echoes the action plot and provides its own arc of pleasure, with musical numbers that may be more or less extraneous to the main action.

What makes Viertel’s anatomy of shows interesting is that even the narratively “irrelevant” numbers tend to occur in the same spot from show to show, and they have a common emotional quality. They aren’t just “spectacle interrupting narrative,” to use a film-studies commonplace. As spectacle, they have their own pattern, and that’s gratifying alongside the pleasures of the story. Viertel’s macro-schema is probably known to many insiders and fans, but it was all news to me, and it helps me understand the musical spine of this recent movie.

Hence today’s title, of an entry that is 100% spoiler-filled. I’ll consider La La Land as a classically constructed film. Then I’ll test its “making” against Viertel’s template of a musical. I conclude with some remarks on how analyzing these patterns highlights the movie’s variance from adjacent traditions.

From meet-cute to remeet, and re-remeet

Start with the Hollywood plot structure. Kristin has argued that even though mainstream American screenwriters sometimes claim to be following a three-act plot model, their craft practice often pushes them to a four-part schema. (She has discussed this here, and I’ve given examples here and here.) Specifically, the long second “act” is usefully thought of as two separate parts split by the film’s midpoint.

The conventional plot pattern consists of a Setup in which protagonists define their goals; a Complicating Action that redefines those goals; a Development that muddles, delays, or intensifies the goals; and a Climax that resolves them. These parts typically run 20-30 minutes, and films of varying lengths, long or short, can include more or fewer parts than these four. In most cases there will also be an epilogue or “tag.”

La La Land runs almost exactly 120 minutes, not counting the opening logos or the end credits. The Setup (running 25 minutes) establishes Mia and Sebastian as dual protagonists, caught in the midst of the initial traffic jam.

We then follow Mia through her day as a barista, her failed audition, her return to her apartment, and her agreement to go out to a networking party with her flatmates.

A flashback returns us to the traffic jam, and now we follow Sebastian to his apartment, where in a parallel to Mia’s day he makes coffee, rummages through unpaid bills, and talks with his sister. He goes on to his job as pianist playing Christmas music at a cocktail bar. Mia, who’s come in by accident, stands before him, moved by his switch into improvised jazz. But Sebastian is fired, and disgruntled, he coldly bumps past her.

The Complicating Action starts after Mia fails another audition. She goes to a pool party and sees Sebastian in the ensemble. She teases him, and they leave the party together. Although there’s friction between them, they start a friendship. They confess their dreams: she wants to be an actress and he wants to start a club that hosts classic jazz.

Mia absentmindedly agrees to go to a movie with him on a night she has a date with her boyfriend. But she’s haunted by Sebastian’s music and she finds him at the theatre, watching Rebel without a Cause. They go to the planetarium featured in the film and kiss. At the end of the Complicating Action, about 60 minutes in, Mia resolves to write a one-woman show for herself.

The Development is the stretch where backstory is introduced, obstacles create delays, and subplots intertwine with the main action. Since in La La Land the romance seems solid (there are no love rivals), and there are no secondary characters of consequence, the film is devoted to the other major plotline: the obstacles encountered in our couple’s quest for success. Those in turn affect the romance.

A Development also typically relies on montage sequences, and we get plenty here. Mia works on her show, while Sebastian is offered a chance to join his friend Keith’s combo. To stabilize his life with Mia, he takes the job.

Soon he’s on tour, and the band finds some success, though he’s compromising his principles. “Do you like the music you play?” Mia demands, and he evades answering. The crisis comes when a photo shoot delays his arrival at her premiere, which is a fiasco.

Mia declares: “It’s over”—meaning both her career and their affair. She goes back home. We’re at the 90-minute mark.

We’re ready for the Climax, which is often driven by a deadline. Sebastian takes the call asking Mia to audition, and he rushes her back to it. She gets the part, and the two of them decide to wait and see how their relationship develops.

Five years later, Mia is now a success. This seems an abrupt, even anti-climactic turn of events, coming only eleven minutes after the Climax started. Apparently, despite their declarations of undying love, the couple’s romance was never rekindled. We see Mia visit the café where she was once a barista and return to her hotel and her husband and daughter. Her activities are crosscut with glimpses of Sebastian alone in his apartment. In effect, this passage balances our alternating introduction to the couple during the Setup.

Mia and her husband drop in on a club that turns out to be Sebastian’s. Mia and Sebastian eye each other longingly. Mia watches him play Their Song, and this launches an apparently shared fantasy of an alternate-world climax and resolution.

There’s a replay of the two of them at the cocktail bar, but this time Sebastian doesn’t brush past her. They kiss passionately. After this what-if premise, the race to the audition is replayed in stylized form, and the trajectory of Mia’s career—going to Paris, finding screen success, forming a family—is reenacted with Sebastian as her mate. At the end, Sebastian, not her husband, is sitting with her in the club (listening in effect to himself), and they kiss.

This soufflé of flashbacks and fantasies ends the plot on the conventional romantic clinch. But the film’s tag, of course, is their return to reality and the sad smiles shared as she goes off with her husband. In all, this double climax/ resolution turns out to run almost thirty minutes, which would be unusually long for a non-musical.

As is customary in Hollywood narrative, motifs and parallels crisscross the film. The opening song on the freeway lays out hints of what is to come. The sequence alternates a woman singing about a career as a film star (“It called me to be on that screen”) and a man singing about a career honoring old music (“ballads in the bar rooms left by those who came before”). Anticipating the finale, the woman’s song includes mention of a boy seeing her on the screen and remembering that he knew her.

More parallels and rhymes follow. Mia nearly stands up Sebastian on their date; he misses her show. Each encourages the other to keep struggling. Mia’s blockhead boyfriend anticipates her eventual GQ husband, as if she has decided not to go for the edgy type Sebastian is. The motif of Mia’s beloved aunt, who inspired her love of movies and her urge to act, gets dramatized twice, once in her one-woman show and more successfully in her audition song, “Here’s to the Ones Who Dream,” which wins Mia the movie part.

So many things are doubled that it’s not surprising that the Setup parallels each protagonist’s day and establishes the crucial moment at the supper club. That too gets replayed—once in the real world, as she and her husband hear Sebastian’s performance of his tune for her, and once at the start of the fantasy projection of their future, which becomes a replay of her actual life with her husband.

So far, so classical. But—duh, as they say–La La Land is also a musical.

That’s the Broadway melodies

My outline of La La Land‘s construction is fairly hollow, and could be filled in with closer consideration of the moment-by-moment process of conflict and change, or the flow of information as we’re attached to one character or the other. But we get access to another layer of “making” by considering the film as a musical–more specifically, a Broadway musical. (No surprise that the lyricists are stage-based.) Viertel is a big help here. His account of the prototypical song plot fits La La Land fairly well, and the places where it doesn’t are pretty interesting too.

Broadway shows of the Golden Age (roughly 1942-1975) tend to have the double plotline characteristic of Hollywood films. Both shows and movies make romance central, and this permits the action plot and the song plot to fit together. In Broadway shows, as in many films, paired protagonists try to find happiness in both love and work. Intertwined goals are central to getting the action moving, and so goals are ingredient to the song plot.

Director Damien Chazelle apparently hesitated about opening with the freeway-gridlock number, but he and editor Tom Cross decided to announce the film’s song-and-dance premises immediately. I think the pressure of show-biz tradition helped. According to Viertel, the prototypical musical might start with a solo, as with Oklahoma!’s “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’.” But it may also start with a “blowout,” and La La Land’s “Another Day of Sun” surely counts as that. It establishes milieu and mood, in somewhat the manner of the bouncy introduction to Damon Runyon’s world in Guys and Dolls, and it announces the central goal of showbiz success.

Viertel marks the next number as crucial. It’s the “I Want” song, the initial crystallizing of the protagonist’s goals. In La La Land, that position is occupied by “Someone in the Crowd,” which starts as an ensemble number with Mia’s brassy roommates but devolves into a solo for her. By then, the “someone” she seeks isn’t only a career-enhancing meetup but a love partner.

After the plot moves into the Complicating Action phase, Mia and Sebastian meet cute again at the pool party. He’s playing in a lame retro band and she teases him, in revenge for his brushoff at the piano bar. There follows the next key item in the song plot, what Viertel calls “the conditional love song.” The prototype is “If I Loved You” (Carousel). Essentially it declares how wrong the boy and girl are for each other. It has the function of blocking and deferring the goals of the love plotline, and in non-musical rom-coms, it takes the shape of verbal sparring, quarrels, and competition (as in, say, You’ve Got Mail).

Clearly, “A Lovely Night” is a conditional love song, as Mia and Sebastian remark on how the LA view would be perfect for a couple who were really in love. But as often happens, while the words refuse romance, the music and the choreography show that the two ought to be together.

At this point in the song plot, Viertel suggests, the show needs a burst of energy. In La La Land, what he calls The Noise is delivered by the instrumental number at the jazz club, called in the soundtrack album “Herman’s Habit.” It’s not narratively gratuitous, as it’s an AV demo of the sweet collective creativity Sebastian admires in classic jazz. The number also marks Mia’s growing affection for Sebastian and her belief in his dream.

But now Viertel’s Broadway template diverges from La La Land, and it points up a crucial factor in the film. The conventional song plot typically devotes a number to a second couple or a subplot. Think of the comic couple in The Pajama Game, and the number “I’ll Never Be Jealous Again,” which expresses Hines’s unreasonable fear of losing Gladys. That show also includes the subplot of labor negotiations with the devious Mr. Hasler. But La La Land doesn’t have a subplot involving a second couple, a romantic triangle, or a villain. So no such song appears.

Next on the Viertel template is a star turn, a distinctive number for one of the major players. That function is fulfilled by “City of Stars,” the introspective musing of Sebastian on the pier. Viertel indicates that the following number tends to be a high-energy tentpole that starts the buildup to the first-act curtain. That position is occupied by the airy pas de deux at the Griffith Observatory on their first date.

We’re now into the Development section, with Mia working on her one-woman show and Sebastian touring with his friend’s combo. The summer montage sequences offer other numbers, including Sebastian’s performance with the jazz group and the “City of Stars” duet with the couple at the piano. These bits don’t fit easily into Veirtel’s template, but what does is the “curtain song,” the Messengers’ “Start a Fire” number. It’s splashily performed at the concert that makes Mia apprehensive.

The performance functions as a curtain song, I think, because of Viertel’s claim that the close of the first act typically signals dashed hopes. The curtain numbers of Gypsy, Guys and Dolls, Carousel, West Side Story, and other shows announce a failure to achieve goals. “The most typical kind of first act curtain,” Viertel explains, is “the unraveling, in an instant, of everything everyone has planned.” It’s too strong a description of La La Land’s concert, but Sebastian’s cynical keyboard tweaks during the band’s blast of adult contemporary R&B mark him as a sellout. “Do you like the music you play?” He seems to have given up his dream, a failure that becomes the first crack in the couple’s relationship.

There are fewer discrete numbers in the film’s last stretch; it lacks several songs in the Viertel template (the Welcome-Back number, the second star turn, more subplot songs, and the first big showpiece). Owen Glieberman has noted that the film’s second hour is notably less buoyant, and the first full-blown number in the Climax is melancholic.

“The Fools Who Dream” is gently confessional, in contrast to the overheated delivery of Mia’s earlier auditions. It’s what Viertel calls a second-act showpiece, and true to that convention it yields a big plot point: She wins the role.

The resolution of the plot, what Viertel calls the “next-to-last scene,” need not be a number at all. It’s often a “book scene,” and so it is here. After Mia wins the role, she and Sebastian admit both their love and the difficulty of staying together.

There follows the finale, a bookend to the freeway opening. “The 11:00 scene,” as Viertel points out, is often a wide-ranging reprise. La La Land’s eight-minute sequence presents a synthesis of the musical motifs and a revised, stylized version of Mia’s career.

Oklahoma! is usually credited with popularizing the fantasy ballet interlude, a convention that was picked up in the “Miss Turnstiles” daydream of On the Town, the Girl Hunt of The Band Wagon, and many other what-if sequences in Hollywood musicals. As a stroke of novelty, La La Land saves its fantasy ballet for the end, and makes it a bittersweet contrast to the real resolution.

Reports on the creative process behind La La Land indicate that the filmmakers were constantly weighing their choices about where to put their musical interludes. The fact that they settled on a layout that sticks fairly closely to the Broadway template suggests that Viertel’s song plot has advantages that creators intuitively gravitate towards. Its emotional arc both complements and extends the drama-driven plot.

The long and the short of it

Viertel’s anatomy of the Broadway song plot nicely fills out some patches of classical dramaturgy. It helps us better understand the tacit guidelines that creators follow, and it shows how even movies not drawn from stage shows have absorbed some of their conventions. Yet Viertel’s layout does more than point up the affinities between La La Land and stage musicals. It also helps us see where the film rejects the traditional schema.

The film’s deletions from the song plot omit love triangles (of any consequence), subplots, villains, and parallel couples. Sebastian’s sister is basically an expositional device, while Mia’s roommates are barely characterized and her parents barely seen. The bandleader Keith is mostly a mouthpiece for a musical idiom, and the other members of the combo aren’t individualized. No secondary character is granted a show-stopper like “Sit Down, You’re Rocking the Boat” or “Steam Heat” or “Make ‘Em Laugh.”

In sacrificing subplots and side bits, La La Land forfeits what such devices add: a different range of emotions, thematic contrasts, relief from overexposure of the two lovers, and comic relief. The film gives up accessory pleasures, like the counterpoint romance of Nathan Detroit and Adelaide in Guys and Dolls, or the ballad of the parents at the piano in Meet Me in St. Louis. In a bold genre change, La La Land stands or falls by its two principals.

Strangely, this spare plot consumes two full hours. Compare its Hollywood counterparts. Cover Girl, another showbiz tale, runs fifteen minutes shorter, but has time for a fully-rendered sidekick, a competitor for the heroine Rusty, a nice role for Eve Arden, and a parallel plot (thanks to flashbacks) devoted to Rusty’s grandmother. At 95 minutes, On the Town squeezes in three couples and a New York travelogue. As for the often-invoked Demy, compare the 90-minute Umbrellas of Cherbourg, which manages to deck the plot out with two old ladies and two deftly characterized rivals for the central couple. Better yet, recall Les Demoiselles de Rochefort. Granted, it too runs two hours, but it has to pack in five couples, one triangle, a starstruck café waitress, and for good measure a serial killer.

More broadly, La La Land doesn’t give its protagonists sharply defined goals. They just want to succeed, through rounds of auditions or short-term music gigs. In Cover Girl Rusty is given clear-cut options: To sign on as a model or stay a club dancer? To marry a piano player or a Broadway impresario? And as Viertel points out, there’s often a bigger issue at play—statehood in Oklahoma!, modernizing a country in The King and I, moving a family from St. Louis to New York. Nothing like this hovers over the couple in this rather hermetic movie.

What fills up that extra running time in La La Land? For one thing, the very parallels that I’ve mentioned, notably the extended scenes in the café; but also, I think, the pool party, with its sideswipes at the movie industry, and the planetarium dance, pretty as it is. A older studio-era film would have gotten the romance going sooner, in the Setup, sharpened the choices facing the characters, and fleshed out their milieu with friends, family, and minor players who get a little bit of the spotlight. (Keith would almost certainly have gained a romantic partner, hopefully a wise-cracker.) A Demy film would have added more characters as well, with a crisp geometry of counterparts and substitutions. Everything would be color-coded too.

The slimness of the plot can be taken as a point against the film, but focusing a musical so tightly on the couple was probably worth trying. If anybody cares, I enjoyed the film, and—to invoke the distinction between taste and judgment—I think it’s a solid, sometimes stirring effort. But what matters to me now is the way that thinking about craft traditions, particularly as they affect structure, allows us to plot some ways in which La La Land is both traditional and original. Evaluation is important, but it can be guided by analysis. An essential part of criticism involves studying how things are made.

Thanks to Jeff Smith for advice about the Messengers’ musical idiom, and to Michael Campi and Peter Rist for discussions about the film.

The quotation from Shklovsky at the start comes from the extract from A Sentimental Journey (1923) in Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader, ed. and trans. Alexandra Berlina (Bloomsbury, 2017), 150. For another Shklovskyan foray into contemporary moviemaking, you can try “Pulverizing Plots.” My quotation from Viertel on first-act curtains comes from The Secret Life of the American Musical, p. 152.

More on the making: A fairly detailed account of LLL‘s choreography is provided at the Verge, with more film references than you can shake a stick at. On the authenticity dimension, Glenn Kenny gets on the case of jazz purists.

Kristin’s discussion of four-part structure is at its fullest in Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Analyzing Classic Narrative Structure. I discuss it and apply it to some examples in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Msodern Movies. For more examples, visit our category Narrative Strategies.

P.S. 24 January 2017: LLL has garnered a heap of Oscar nominations this morning. Now this Los Angeles Times story supplies more information on how it was made (financially).

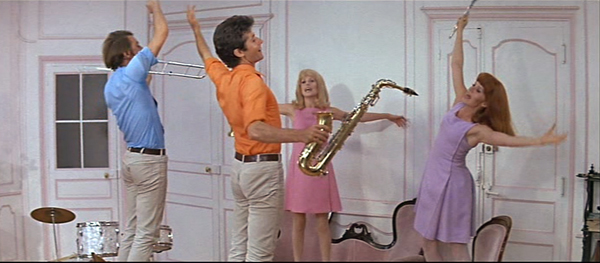

Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967).