Archive for December 2013

The ten best films of … 1923

Le brasier ardent.

Kristin here:

Six years ago David and I celebrated the 90th birthday of the classical Hollywood cinema with a post that included a list of what we considered the ten greatest (surviving) films of 1917. Choosing the ten best films of 90 years ago has become a custom, one which helps us avoid doing a ten-best list for the current year. It’s a way of drawing attention to some wonderful but often little-known films, for those who are interested in exploring the treasures of silent cinema.

For previous entries, click here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, and 1922.

For some reason, that 1917 list was pretty easy to put together. In recent years, I’ve had more trouble. As I wrote last year, “For the past two years, I’ve noted that it was difficult to fill out the list of ten masterpieces. I keep thinking that I’ll get to a year where I won’t have to say that, but 1922 turns out not to be that year. Some titles were obvious, but the last one or two took some hunting.” Well, 1923 still isn’t that year. I’ve again had some trouble filling out the top ten.

Why? 1923 should be packed with worthy candidates. But oddly, some of the most significant directors of the era didn’t make films that year. This seems to have been partly because success brought greater ambitions. In 1923 Fritz Lang was preparing his epic two-part Die Nibelungen, guaranteed to show up in next year’s list. Abel Gance had embarked the long road to the release of Napoléon, four years later.

Carl Dreyer, who had made three films in 1919 and two each in 1920 and 1921, was bouncing around among companies and countries in the mid-1920s, and didn’t again release anything until his 1924 German-produced film, Michael.

Others made relatively unremarkable films. F. W. Murnau’s surviving film from 1923, Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs, serves mainly to prove that comedy was not his strong suit. Victor Sjöström’s Eld ombord (The Hell Ship) doesn’t match the masterpieces we find elsewhere in his career. Louis Feuillade’s 1923 feature Le Gamin de Paris is likewise unexceptional, though it’s of interest for showing his abandonment of complex staging and his conversion to American-style cutting, including angled shot/reverse-shots. (Of Feuillade’s 1923 installment film Vindicta, we can’t speak; we haven’t been able to see it.)

Other films are lost. John Ford made four films that year, only one of which survives: an incomplete, beat-up version of Cameo Kirby that doesn’t make it look like anything special. Murnau’s first 1923 film, Die Austreibung, seems to be gone. Mauritz Stiller’s The Blizzard is lost, and he, too, was probably already involved in his own 1924 two-part epic, The Saga of Gösta Berling.

[December 29: Brian Darr tweets that The Blizzard is not lost, which I am glad to learn. Its Wikipedia entry confirms that it is only partially lost, with about two-thirds of the film known to be preserved.]

Finally, the Soviet cinema, which was to make such major contributions to 1920s cinema, had not yet gotten off the ground.

Still, with some help from David, I’ve concocted a list with some great films and some near-great ones. The place to start was obvious.

From the ridiculous to the sublime

Some years now we’ve been watching the careers of Charles Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton delivering wonderful short films and inching toward even greater things. This was the year they blossomed.

Chaplin made a charming short feature, The Pilgrim, this year, but he also surprised everyone by making a sophisticated sex comedy (appearing only in an unrecognizable cameo as a porter). The title role of A Woman of Paris features Chaplin’s regular leading lady, Edna Purviance, as a village girl, Marie, who loses her young boyfriend Jean through a misunderstanding. She runs off to the city to become a rich man’s mistress and realizes too late what she has lost.

The plot centers largely around this romantic triangle and Marie’s indecision about whether to return to her boyfriend, who has become an impoverished artist in Paris, or to stay in the luxurious life that Pierre provides her. The affair between Marie and Pierre is handled in a sophisticated and yet subtle way. There are no love scenes, but at one point Pierre finds himself without a handkerchief and goes into the bedroom to pluck one casually out of drawer. Clearly he spends a lot of time in their love nest.

At the same time, the film deals more generally with the gulf between the very wealthy and the working-class people who who serve them. In one well-known scene, a woman gives Marie a massage, and the camera stays mainly on the masseuse as she tries to maintain a neutral expression while obviously being shocked by the lurid gossip between Marie and a friend. In another, a kitchen assistant in a swanky restaurant cannot bear the odor of the aging game bird he has to fetch for the chef, but the chef and Pierre consider it a prime delicacy.

At the same time, the film deals more generally with the gulf between the very wealthy and the working-class people who who serve them. In one well-known scene, a woman gives Marie a massage, and the camera stays mainly on the masseuse as she tries to maintain a neutral expression while obviously being shocked by the lurid gossip between Marie and a friend. In another, a kitchen assistant in a swanky restaurant cannot bear the odor of the aging game bird he has to fetch for the chef, but the chef and Pierre consider it a prime delicacy.

One of the strengths of the film is that it does not take the obvious approach of making Pierre into a fat, obnoxious oaf. On the contrary, Adolphe Menjou plays him as a witty, unflappable figure. He thinks nothing of arranging a marriage with a rich woman while planning to carry on his affair with Marie, but he puts up with her shifting moods and does genuinely seem to love her. The touch of having him play his saxophone while Marie has a tantrum and orders him out (right) typifies the light touch Chaplin applies to what is ultimately a tragic story.

A Woman of Paris was not well received upon its release, at least by the ticket-buying public, who expected a Chaplin film to star the Little Tramp and to be straightforwardly funny. The title at the beginning, where Chaplin explains that he does not appear in the film undoubtedly did little to appease them. Many critics were respectful, however, and other filmmakers recognized the new type of sophisticated comedy that he had introduced. Lubitsch, who was working on Rosita at the same studio, United Artists, was definitely influenced by it–as we shall see next year when his The Marriage Circle figures in the top ten of 1924. That film includes Menjou, playing a similar role, and in fact after playing minor roles for nearly ten years, he became a star with Chaplin’s film.

[February 10, 2014: Paul Duncan, Film Book Editor for Taschen, has kindly supplied figures showing that A Woman of Paris was profitable, if not as much as Chaplin’s other films: “It earned United Artists $634,000, of which $608,868.91 went to Regent Film (the company Chaplin formed to produce films for Edna Purviance). So with a production cost of $351,853.03, A Woman of Paris made a healthy profit, though, as you write, obviously it would have been more if it had been a comedy starring Chaplin.” Paul also informs me that Taschen’s The Charlie Chaplin Archives, which he is editing, will be published later this year.]

By 1923, Harold Lloyd had already done some shorts featuring nail-biting but hilarious comedy high up on skyscrapers. (See High and Dizzy in our 1920 entry.) In 1923 he took the same sort of premise into the feature-length Safety Last and created an indelible image: a brash young man hanging from a tilting clock. The gags go on story by story. After surviving the clock, Harold manages to get to the next level, only to be chased out a flagpole by a dog (left). Looking back, people tend to remember the vertiginous climb as the whole film, though remarkably, it takes place only over the last third. Earlier scenes involve a romance and misunderstandings that arise from the hero’s job at a department store.

By 1923, Harold Lloyd had already done some shorts featuring nail-biting but hilarious comedy high up on skyscrapers. (See High and Dizzy in our 1920 entry.) In 1923 he took the same sort of premise into the feature-length Safety Last and created an indelible image: a brash young man hanging from a tilting clock. The gags go on story by story. After surviving the clock, Harold manages to get to the next level, only to be chased out a flagpole by a dog (left). Looking back, people tend to remember the vertiginous climb as the whole film, though remarkably, it takes place only over the last third. Earlier scenes involve a romance and misunderstandings that arise from the hero’s job at a department store.

Safety Last wasn’t Lloyd’s greatest film, but it launched the greatest period of his career. He’ll probably be joining us for these nostalgic lists every year now until 1927. The film is still available as part of New Line’s big box set of Lloyd’s films on DVD. (Buy that one, and you’ll be a step ahead of those future lists.) This summer the Criterion Collection brought Safety Last out on DVD and Blu-ray. There’s only that one feature on the disc, but it includes several supplements, including three newly restored Lloyd shorts and Kevin Brownlow’s 104-minute documentary, The Third Genius.

Keaton, too, entered a hugely creative streak in 1923. He made an amusing satire on Intolerance, the feature-length The Three Ages, in which Buster traces love through the stone age, the Roman era, and the Roaring Twenties. As Keaton himself acknowledged, “Cut the film apart and then splice up the three periods, and you will have three complete two-reel films.” He followed it up, however, with a masterpiece that displayed a complete command of story structure in the classical Hollywood mold: Our Hospitality. It’s arguably as fine as anything he ever made, except The General, which just edges it out.

Interestingly, Our Hospitality and The General are Keaton’s only two period pieces. (that is, if one excepts The Three Ages, which is far more farcical and does not attempt to recreate a realistic period atmosphere.) Both also take place in the South, and outdoors to a considerable extent. The milieu seems to have inspired him. Dealing with old-fashioned trains and other technology generated a lot of clever gags, and the fields, forests, and rivers helped give these two films a pictorial beauty that separates them from the Keaton’s other films.

Way back in 1978, when David and I were working on the first edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we wanted to include an extended analysis of a single film in each of the chapters on film technique. For mise-en-scene we chose Our Hospitality, which contains numerous uses of setting, costume, acting, and lighting brilliant enough to inspire a teacher and straightforward enough for students to notice and understand. Plus what better way to win over students who think that old black-and-white silent movies aren’t worth watching?

The story is simple. Willie McKay, the hero, travels from New York to the deep South, under the impression that he has inherited a mansion. The trip south on a very old-fashioned train supplies a long string of marvelous sight gags. There Willie meets the heroine, who shares his coach. Upon arrival, Willie discovers that his “mansion” is really a decaying house. Since the heroine has invited Willie to dinner, he wanders around to pass the time, unaware that he has inherited something else: a feud. The heroine’s family has a longstanding grudge against the McKays, and the father and two brothers are determined to shoot Willie. The only catch is that Southern hospitality dictates that they cannot kill him while he’s in their home.

In our analysis in Film Art, we pointed to the many motifs Keaton uses in service of the narrative, such as the moment of the hero’s rescue of the heroine as an echo of the earlier fishing pole/waterfall gag. One stylistic motif of staging comes back several times: Keaton using foreground doors or walls to create depth staging of moments when people spy or eavesdrop on others. In the frame on the left below, one of the brothers waits to ambush Willie, who is unaware of his presence (or indeed of the feud itself). In the one on the right, Willie eavesdrops on the brothers in their house, learning that they intend to kill him but that he is safe inside the house. Now Willie learns what’s going on, while the brothers don’t realize that he’s overhearing their plan. Such compositions are a motif in the film, forming a way of manipulating the narration–usually giving us more information than the characters onscreen have.

Like Safety Last, Our Hospitality ushered in the prime of the comedian’s career. Keaton made a string of marvelous features that lasted until The Cameraman in 1928. He didn’t always sign the films as director (he’s listed as co-director of Our Hospitality, along with John Blystone), but his unerring sense of how to compose images for the entire frame, both its surface composition and in depth, suffuses all his films of this period.

I’ve mentioned that Lubitsch was working at United Artists in 1923. Rosita was his first American film, starring Mary Pickford. It’s certainly not a masterpiece on the level of The Marriage Circle or Lady Windermere’s Fan, but Rosita is a charming and impressive film, certainly at least as good as Lubitsch’s other lesser films of the decade, Forbidden Paradise and Three Women.

As I discuss in my book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, the director had already been tentatively using classical Hollywood style in his last two German films, Das Weib des Pharao and Die Flamme. In Rosita, he managed to balance a typical historical epic from his German period (Madame Dubarry, Anna Boleyn) with the light, vivacious appeal of his star. She plays the title character, a cheerful street musician who is in love with Don Diego, an impoverished nobleman and military officer. Rosita catches the eye of the lecherous king. Don Diego ends up condemned to death, and Rosita plots to save him.

The sets were built on the enormous backlot of United Artists, where Douglas Fairbanks’ castle for Robin Hood had stood. The day after Rosita wrapped, the construction of the sets for The Thief of Bagdad began on the same lot. Indeed, one can detect a distinct similarity between Rosita’s big sets–city streets and a large prison–and those of the two Fairbanks films. This frame is a shot of the prison interior emphasizing a gallows in the background:

Given that this giant set was built in the open air, Lubitsch must have filmed this and other scenes at night, using the giant arc spotlights that had recently become a standard tool of Hollywood filmmaking to throw great swathes of illumination across the scene. In general, Rosita‘s style demonstrates that by 1923, Lubitsch had come fully to understand the American approach.

As a vehicle for Pickford, the film also is skillfully done, permitting her numerous intimate scenes that show off her charm. Given her star persona, the dramatic situation is leavened with humor in the interior scenes. Rosita’s poor family, a large, rowdy bunch, provides much of this, as when Rosita brings home a perfumed handkerchief and the impressed parents and children in turn bury their noses in it and sniff deeply. Rosita’s reactions to the King’s attempts to seduce her are also somewhat comic, though there is definitely a threat hanging over the situation.

Unfortunately, like all too many of the films on this year’s list, Rosita is difficult to see. It seems to have survived only in a Russian print, and a rather contrasty, worn one at that, as the frame above demonstrates. As long as that is the sole available material, a restoration might be too daunting. Still, in this day of digital manipulation, perhaps something could be done to improve the image quality. I hope at some point it will become available on home video. That also goes for Lubitsch’s other somewhat lesser films of the mid-1920s, Forbidden Paradise and Three Women.

Rosita’s reputation has suffered from strange statements Pickford much later made to Kevin Brownlow and which he published in The Parade’s Gone By. There she claims she and Lubitsch did not get along and that the resulting film was bad and a commercial failure. With the film itself unavailable for viewing, Pickford’s condemnation was accepted at face value. In fact, documents in the United Artists archive at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research overturn Pickford’s supposed dislike for Lubitsch. For years she tried to find financing to make another film with him, and in 1926 she called upon him for help in editing Sparrows. With the discovery of the Soviet print, it becomes apparent that Rosita was far from the disaster Pickford later claimed. Why her memories of her work with Lubitsch became so distorted late in her life we shall probably never know.

Overshadowed masters of French Impressionism

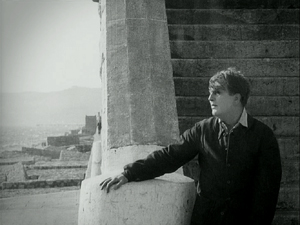

Abel Gance’s flashy La roue (on last year’s list) gets a lot of attention these days. He’s the high-profile representative of Impressionism. Yet 1923 saw the first fiction films from the director who was the movement’s modest heart: Jean Epstein. The very first, L’auberge rouge (“The Red Inn”) is a lovely film, but Cœur fidèle (“Faithful Heart”) epitomizes the quiet side of Impressionism. It’s story is as simple as they get: Marie is a barmaid whose foster parents try to force her to marry a thug, Petit Paul, while she is in love with the sensitive dock-worker Jean. The scenes around the waterside and the famous sequence in a carnival are all done with a realism blended with the subjective camera techniques that convey the characters’ thoughts, perceptions, and feelings in a way that was fresh at the time.

The exteriors were shot around the docks of Marseille, and Epstein uses superimpositions of the ocean to convey the lovers’ longing. Waves are sometimes superimposed over their figures, or one will look into the water and see the other’s face there, as when Jean envisions multiple images of Marie:

Shooting into a distorting mirror, Epstein uses the conventional Impressionist indicator of drunkenness as Petit Paul looks at a woman next to him in a bar:

Coeur fidèle has been released in the UK (Region 2) as a DVD/Blu-ray combo in Eureka!’s Masters of Cinema series. (This includes a helpful little booklet with excerpt from Epstein’s writings and a review of Cœur fidèle by René Clair.) It is also available as a Region 2 French DVD without English subtitles. As these frames indicate, the film survives in beautiful condition.

Along with La roue, Cœur fidèle proved hugely influential. It used the “unfastened camera” that later was credited to Murnau in The Last Laugh. Like Murnau, Hitchcock picked up Impressionist style, as reflected most obviously in his 1927 boxing film, The Ring. Hitchcock’s penchant for moving camera and subjectivity never went away. Hollywood, too, picked up the subjective techniques of Impressionism, especially in the 1940s films that David is studying now.

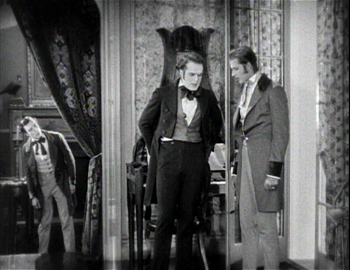

Unlike Cœur fidèle, Le brasier ardent (“The Burning Crucible”) was sophisticated, convoluted, and perplexing. It was one of two films directed in France by the Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine for the émigré film company Albatros. (The earlier one is L’Enfant du carnaval, 1921; as far as I know, no print survives.) Earlier this year, upon the release of Flicker Alley’s box set of five Albatros films, I described Le brasier ardent:

It has a reputation as an audacious, surrealist, and almost incomprehensible film. This may be due to the fact that prints available in archives during the 1970s and 1980s lacked intertitles. The opening nightmare sequence is indeed disturbing, but at least with intertitles, we understand that it is only a dream. It begins with a wild-eyed man tied to a stake where he is about to be burned. The heroine stands looking on, resisting as the man pulls on her long hair, apparently intent on dragging her into the fatal flames to accompany him in death. Subsequent scenes of the nightmare show the heroine encountering different men, all played by Mosjoukine, culminating in a man in evening dress stalking her along a vaguely Expressionist street until she escapes and wakes up in bed.

This nightmarish opening must have established vivid expectations in the spectators of 1923 as to what sort of film they were in for. After the heroine wakes up, however, what follows is quite different. The main plot is a stylized but quite amusing comedy. The heroine is a pampered wife, married to a rich man whom she does not love. She is faithful, but he is unreasonably jealous. He goes to a distinctly odd detective agency, one department of which is “Recovery of Lost Wives” (above), with “Success guaranteed!” and “Nothing to pay in advance!” Juxtaposed with the bizarre opening, this quirky humor might have eluded puzzled audiences of the day. Certainly the film itself was a failure, and Mosjoukine stuck to acting thereafter.

Unfortunately for the husband, Detective Z, whom he picks from the eccentric group pictured above, is the very man, again played by Mosjoukine, whom his wife has dreamed about. What follows is an odd tale with the detective and wife gradually falling love. Mosjoukine, known for his tragic, intense characters in the Russian cinema, plays such figures in the fantasy sequences–but in the main story he is allowed to play for laughs, gamboling and rolling on the floor like a puppy when the wife finally appears at his mother’s apartment and declares her love for him.

Mosjoukine should not, however, be allowed to overshadow his co-stars, Ermolieff actors who were also were to make their way into the wider French production of the day, including Impressionism. The wife is played by Nathalie Lissenko, one of the stars of the pre-Revolutionary cinema, who had acted opposite Mosjoukine in Russia. Among her 1920s roles was the protagonist of one of Epstein’s finest films, the largely unknown L’Affiche (1924). The husband is Nicolas Koline, who started his career with Ermolieff only after the company had left the Soviet Union. He will be familiar to silent-film fans from his performance as Tristan Fleury in Gance’s Napoléon.

By this point, stylistic influences were beginning to pass back and forth between France and Germany. Le brasier ardent shows distinct touches of Expressionism in its decor, as when the heroine flees through a distorted door. (See top.)

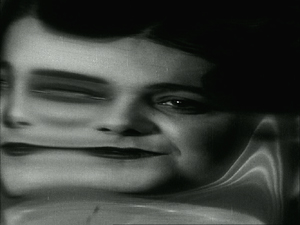

I have to admit that the third Impressionist film on our top-ten list, Germaine Dulac’s La souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) is not one of my favorites. It hasn’t got much of a plot. A sensitive woman in a provincial town finds her husband crass and unpleasant until a final crisis brings them–at least temporarily–together. It’s not so much the simplicity of the story, however, as the rather heavy-handed use of subjective camera tricks to convey Mme. Beudet’s thoughts about her husband, as when a distorting mirror conveys her grotesque view of him (at right).

I have to admit that the third Impressionist film on our top-ten list, Germaine Dulac’s La souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) is not one of my favorites. It hasn’t got much of a plot. A sensitive woman in a provincial town finds her husband crass and unpleasant until a final crisis brings them–at least temporarily–together. It’s not so much the simplicity of the story, however, as the rather heavy-handed use of subjective camera tricks to convey Mme. Beudet’s thoughts about her husband, as when a distorting mirror conveys her grotesque view of him (at right).

We’ve just seen a similar distortion in Cœur fidèle, above, to show a drunkard’s point of view. In Marcel L’Herbier’s El Dorado, from 1921, another distorted-mirror close-up suggests drunkenness without using a character’s point of view (see Film History: An Introduction, 3rd edition, p. 79).

The film has decided virtues, such as the lovely shots of the small provincial town in which the film’s exteriors were made, as well as the genuinely surprising and touching ending, which pulls back somewhat from the simplistic characterization of M. Beudet.

As with some of our choices from previous years, The Smiling Madame Beudet goes on the list partly because of its historical importance. Dulac was one of the early women directors to make a career in the cinema. Back in the days of 16mm, prints of this film were among the few Impressionist classics available for film club and classroom use, and the film became a staple in feminist-film courses.

Ironically, nowadays teaching the film is more difficult. Oddly enough, none of the mainstream labels has brought out a DVD with English subtitles. A German DVD, which includes two other short Dulac films, Invitation au voyage (1927) and the surrealist classic La coquille et le clergyman (1928), is available. The copy on this DVD is probably the same as the fairly good-quality Swiss archive print on YouTube, with bilingual French and German intertitles. For anyone with even an elementary knowledge of either language, the titles are not very challenging.

Caligarisme spreads

Caligarisme was the French word for cinematic Expressionism, which, as the example from Le brasier ardent shows, fascinating many French filmmakers.

Despite the lack of major contributions from Murnau and Lang, in 1923 the country’s cinema was going strong. Several films that fall slightly short of being masterpieces appeared. By this point the Expressionist film movement was well established, having begun in 1920 with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. Some of its greatest films–Der müde Tod, Nosferatu and Dr. Mabuse der Spieler–had already appeared.

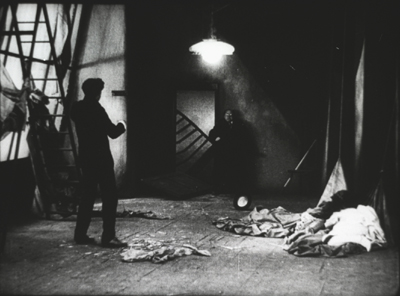

Three very good Expressionist films came out in 1923: Erdgeist (“Earth Spirit,” directed by Leopold Jessner), Schatten (“Shadows,” released abroad as Warning Shadows; Arthur Robison), and Raskolnikow (adapted from Crime and Punishment; Robert Wiene).

It’s really a toss-up as to which film should represent Expressionism on this year’s list. I give the edge to Erdgeist, largely because it and Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morn to Midnight”) are the two films from the movement that push the style the furthest. They come the closest to Expressionism as it existed in drama and the other arts. Most Expressionist cinema “tamed” the style a bit by applying it to genre tales: horror (Caligari, Nosferatu), fantasy (Der müde Tod), historical myth (Die Nibelungen), and science fiction (Algol, Metropolis). These two films, in contrast, depended on dramas where elemental human passions are released and taken to extremes, with the costumes, decor, makeup, and acting reflecting the characters’ inner states.

The film was based on the first of the two “Lulu” plays by Frank Wedekind: Erdgeist (1895) and its sequel Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box, 1904). G. W. Pabst’s much better-known Pandora’s Box (1929) combines the two plays, which tell a continuous story about an amoral young woman who lives by exploiting wealthy men but drives them to extreme jealousy by flirting with other men.

In Pabst’s film, Louise Brooks plays Lulu as a vivacious young woman, seemingly unaware of her disastrous effect on the men around her. Asta Nielsen plays the character in Jessner’s film as a ruthless, mature woman. The plot concerns Dr. Schön, a rich man who found Lulu on the streets when she was a child and has raised her with the intent of having her become his mistress. At the beginning, she is married to Dr. Goll but immediately begins seducing Schwartz, an artist hired to paint her portrait. In the image below, Goll bursts in on them in Schwartz’s studio and Lulu collapses at the right. The distorted stairway, the streaks of light painted on the set, and the jagged shadows all create the Expressionist look–as does the eerie blank glow of Goll’s glasses.

The acting is exaggerated and unnatural. Nielsen, foregoing all glamor, frequently holds a grimace on her face to the point where she almost looks like she is wearing a mask. In an early scene Goll moves his cane about, and she dances like a marionette attached to it by strings. (Puppet-like acting was a convention of Expressionist drama.)

Overall, the style is so grotesque and the characters so unpleasant as to make it clear why Erdgeist is one of the least remembered of the major Expressionist films. It is not available on home video. The print I saw about 16 years ago had Dutch intertitles and was somewhat dark. Perhaps, like Von Morgens bis Mitternachts, it will eventually be restored and released on DVD.

Two Expressionist films deserve brief mention as well.

Robert Wiene, the director of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, launched the Expressionist movement in cinema but never made another film that gained nearly as much attention. That’s a pity, because Raskolnikow is quite a good film–of all the Wiene films I’ve seen, probably his second best (though The Hands of Orlac, 1924, has its virtues). I found it difficult to decide between it and Erdgeist.

Crime and Punishment turns out to be, not surprisingly, a good fit for the style, with the hero’s increasingly bizarre view of the world literalized in the settings. The film seems to have had a higher budget than Caligari, and the sets are sturdier looking and more three-dimensional. (See bottom.) Wiene also had the good fortune to work with a group of Russian emigré theatrical actors who had trained under Stanislawski and worked at the Moscow Art Theater. Clearly they had to adapt their approach distinctly to achieve Expressionist performances, but they managed well. The lead, Gregori Chmara, makes a haggard and mercurial Raskolnikow.

Back in the 1970s, when I became intrigued by German Expressionist cinema, Schatten was considered one of the main classics. That was no doubt partly due to the limited number of Expressionist titles available for viewing at the time. It’s a good film, but its prominence in film history has declined a bit in the intervening decades, especially as the full surviving work of Murnau and Lang has been discovered and restored.

Schatten is an atypical Expressionist film. Not that many of its sets are distorted or simplified in the usual ways. (This is also true to some extent of designer Albin Grau’s other notable Expressionist film, Nosferatu.) Its few exterior shots, including the opening, show the most strongly Expressionist decor (below left). Part of the action consists of a shadow-puppet show put on by a wandering entertainer (below right). Its plot seems to magically unleash the passions of the onlookers, who begin to behave in odd ways. The male guests (and a servant) try to seduce their hostess, driving the master of the house into a jealous rage.

The shadow play creates its own distortions and stark, black and white imagery. Once the show is over, Robison often frames the distorted shadows of the characters more prominently than their actual bodies (again echoing some of the scene with the vampire in Nosferatu). In this corridor scene one of the servants slyly creates cuckold’s horns on another man’s head:

Shadows, with their natural capacity for distortion, not surprisingly appeared in many Expressionist films, though never so pervasively as in this one.

Raskolnikow is unfortunately not available on home video, at least in an acceptable copy. (The reviews for the Alpha release on Amazon deem it “unwatchable.”) Warning Shadows is available on DVD from Kino or to stream on Amazon (free to Prime customers).

Returning to our top-ten list, I yield the floor briefly to David, who has been studying Sylvester for another project.

German silent cinema is more varied than a litany of the official classics, from Caligari to Metropolis, would suggest. One of the most intriguing trends of the period involved what was called the Kammerspiel, or chamber-play, film. Kammerspiel films were far more naturalistic than Expressionist films. They concentrate on a very few characters in a drastically limited number of locales. Performance is often slow and understated, though action may freeze into somewhat contorted poses. The action typically takes place in a short time span, and it is built up out of everyday activities in working-class households—chores, job routines, the habits of family life. Eventually, however, the mundane milieu is likely to explode into violence.

The versatile Carl Mayer (who worked on the script of Caligari) conceived of the early Kammerspiel film Scherben (Shattered, 1921), which defined the trend. In the same year the stage director Leopold Jessner released the remarkable Hintertreppe (Backstairs), which Kristin mentioned as a runner-up in her Best of 1921 list. Mayer also wrote the script for Sylvester (1923). Named for the feast day of St. Sylvester, 31 December, it’s known in English as New Year’s Eve. It’s not available on home video, but it’s worth seeking out in screenings. It remains a striking study in tabloid tragedy.

A café owner and his wife are busily serving crowds on New Year’s Eve. After a big meal and too many drinks, the wife and the mother-in-law fall to quarreling. The tensions around the table are constantly crosscut with the increasingly wild revelry in the café and the upper-class nightclub across the street. As midnight draws near, the women struggle for the husband’s loyalty. This petty quarrel will end in death.

Director Lupu Pick explores the limited space of the action by shooting the parlor from many angles, including ones that make daring use of a mirror (right). The street shots feature extravagant camera movements that look forward to the “unchained camera” made famous in Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh, 1925), directed by F. W. Murnau and scripted by Mayer. With its strict limitation to a single night and its focus on domestic space, along with suggestions of the husband’s Freudian dependence on his mother, Sylvester showed how a fait divers could yield psychological drama.

The Kammerspiel film wasn’t a dead end. After Carl Dreyer’s borderline contribution to the trend, the Ufa production Michael (1924), back in Denmark he created probably the best of the lot: The Master of the House (Du Skal Aere Din Hustru, 1925). He later returned to the aesthetic in Two People (1945), and he continued to exploit its possibilities in his last features. Over the years after World War II, other directors were rediscovering Kammerspiel principles. We see fresh applications of the approach in Les Parents Terribles (Cocteau, 1948), Les Enfants Terribles (Melville, 1949), and of course Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) and Dial M for Murder (1954). As often happens, ambitious films of the sound cinema owe a good deal to innovative impulses of the silent era.

Welcome, experimental cinema!

One of the most remarkable films of 1923 is a mere three minutes long. Man Ray, an American painter and photographer who moved to Paris in 1921 and became involved in the Dadaist and Surrealist movements. He soon acquired a film  camera and later described how he shot bits of footage with it:

camera and later described how he shot bits of footage with it:

a few sporadic shots, unrelated to each other, as a field of daisies, a nude torso moving in front of a striped curtain with the sunlight coming through, one of [his] paper spirals hanging in the studio, a carton from an egg crate revolving on a string–mobiles before the invention of the word, but without any aesthetic implications nor as a preparation for future development: the true Dada spirit.

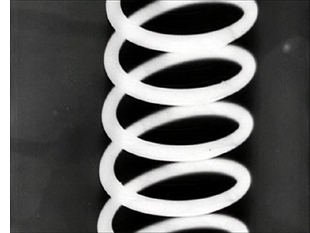

In 1923 Tristan Tzara advertised a Dadaist program in a Parisian theatre to be held the following evening, including a film by Man Ray as part of the entertainment. Ray had only a very small amount of footage ready. Faced with an overnight deadline, he supplemented it by using a technique he had already employed in still photography (the “rayograph”): placing small objects on a sheet of photographic paper in the dark, turning on the light briefly, and developing the image. The result was a series of sharply focused silhouette images of the objects against a plain background. This time Ray unrolled some raw negative film in a dark room, scattered nails, tacks, and other objects on it, exposed it to light, and developed the negative (right). Combined with the shots Ray had previously made, the result was a perfect Dada film, with randomly juxtaposed imagery that defied the audience to make any sense of what they were seeing. He titled it in ironic Dada fashion: Le retour à la raison (“The Return to Reason”).

Despite being cobbled together overnight, Ray’s film offers a broad exploration of the possibilities of abstract filmmaking. The opening, a rapidly shifting stippled screen, resembles the later flicker films of the 1960s avant-garde. The rayograph shots introduce an alien, high-contrast look–not surprising, given that these may have been the first cinema images produced without using a camera.

Ray also shifted between positive and negative imagery. This was not entirely new. Murnau had used short stretches of negative footage in Nosferatu the year before. But Murnau’s negative shots had a narrative function, to convey the eeriness of the environs of the vampire’s castle. In Le retour à la raison, Ray used negative imagery in an abstract way, to create startling juxtapositions of imagery that looked both similar and yet strikingly different. The tacks, nails, and springs in the rayograph stretches could be either stark white against black, as in the image to the right above, or the same shot repeated, but this time in black against white. The film ends with another positive/negative passage. The “nude torso moving in front of a striped curtain” is initially shown in a positive image, then in the same image flipped and shown in negative:

Ray was not the first to create an abstract film. In 1921 German filmmaker Walter Ruttmann probably made that conceptual leap in 1921 with Opus 1, a one-reeler with painted shapes moving around against a dark background. He followed this up with three further films, Opus 2 (1923), Opus 3 (1924), and Opus 4 (1925). (Good-quality prints with toning and appropriate musical accompaniment are available on YouTube: Opus 1 here, Opus 2 here, Opus 3 here, and Opus 4 here.)

I must confess that I probably should have at least mentioned Opus 1 in my entry on the best films of 1921. Still, Ruttmann’s films are far less daring than Le retour à la raison. It and its successors are basically efforts to do what so many filmmakers have tried since: to create the equivalent of a painting, but with motion. Ray’s film went much further, pushing the limits of the young art form in ways that had little precedent in the other arts, apart from Ray’s own highly experimental approach to still photography. There are even two fleeting stretches of film leader with illegible writing on them–a tactic one thinks of more in relation to, say, Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958) than to the silent era. Much of the experimental cinema to come decades later was briefly probed here.

There are several copies of Le retour à la raison on YouTube. The best was posted by Dimitri Shubin, who also provides a piano score. The film is also available on disc 3 of the Unseen Cinema set of American experimental cinema. Unfortunately this copy has a considerable amount of breakup, particularly in the early flicker portions. (An HD version would perhaps help.) The version on Kino’s “Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and ’30s” set has the same problem and is distinctly shorter, apparently because it is running at sound speed. The copy provided by Shubin has the clearest, steadiest video image of the film I have seen. Ideally, of course, Ray’s film should be viewed on 35mm.

I regret that so many of our choices for this year’s list are not available on home video or even, except in very rare circumstances, for viewing on 35mm in archive screenings. Still, part of the purpose of this ongoing series is to call attention to obscure but worthy and important films. Perhaps an archivist or an enterprising DVD publisher will be inspired to restore some of the ones described here.

The quotation concerning The Three Ages comes from p. 217 of Rudi Blesh’s biography, Keaton (New York: Collier, 1966).

Mary Pickford’s strangely distorted claims about Rosita and her relationship with Lubitsch are expressed on pp. 129-34 of Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By (New York: Knopf, 1968). I go into more detail about the continuing Pickford-Lubitsch collegiality in the 1920s in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, pp. 24-26.

For more examples of unusual German silent films, go elsewhere on this site here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here. Criterion has a new, authentic version of Dreyer’s Kammerspiel-influenced Master of the House forthcoming.

The Man Ray quotation comes from a detailed study of Le retour à la raison by Deke Dusinberre in the collection Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1893-1941 (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 2001), published to coincide with the release of the DVD set mentioned above.

Raskolnikow.

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

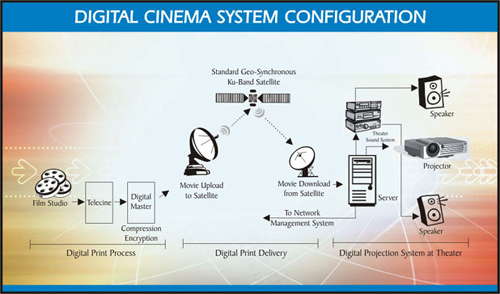

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.

Studios have incentives to shorten the windows, if only because a single promotional campaign can be kept going long enough for both theatrical and home release. In addition, buying or renting a movie with a couple of clicks encourages impulse purchasing, and the cost feels invisible until the credit-card bill comes. Nonetheless, commitment to day-and-date home delivery would be risky for the studios.

Hollywood is more than ever before playing to the global audience. Even with the VOD boom, digital purchase and rental constitute a small portion of the world’s movie transactions. According to IHS Media and Technology Digest, theatrical ticket sales, purchase and rental of physical media (DVD, Blu-ray) add up to nearly 12 billion transactions, while Pay Per View, streaming, and downloads come to only about a billion or so. (These categories omit subscription services like cable television and basic VOD on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and the like.) Moreover, customers in 2012 spent about 61 billion dollars buying tickets to movies, buying DVDs, and renting DVDs. Tania Loeffler of the IHS Digest writes of North America, the most developed market for digital sales and rental:

Movie purchases made online in North America increased year-on-year by 36.6 per cent to reach 29.2m transactions. The rental of movies online also increased, to 112m transactions, an increase of 57.3 per cent over 2011. Despite this strong growth, movies purchased or rented via over-the-top (OTT) online movie services still only accounted for a combined $836m, or 3.3 per cent of total consumer spending on movies in North America.

By contrast, worldwide consumer spending on theatrical movies actually grew in 2012, to a whopping $33.4 billion–over 50 % of all movie transactions. (Thank you, Russia and China.) And despite the decline of disc purchases and rentals, Loeffler estimates that physical media will still comprise about thirty per cent of worldwide movie transactions through to 2016.

Theatrical releases continue to offer studios the best deal. Because the prices of streaming and downloaded films are low, there is less to be gained from them. True, if windows shrink, the studios will demand that Netflix and its confrères price VOD at high levels, say $25-50 for an opening-weekend rental. But consumers used to cheap movies on demand could balk at premium pricing.

At present, digital delivery of movies to the home provides solid ancillary income to the distributors, even if it doesn’t yet offset the decline in physical media. Add in Imax and 3D upcharges, and things are proceeding well for the moment. Like the rest of us, moguls pay their mortgages in dollars, not percentages or transactions. As long as some hits keep coming, we should expect that studios will maintain an exclusive multiplex run for major releases, as the most currently reliable return on investment.

Orpheum metamorphosis

The New Orpheum Theatre, 216 State Street, 1927.

Another note on exhibition relates to the last commercial picture palace in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. My July 2012 entry related the conspiratorial tale of how the grand old Orpheum Theatre on State Street fell on hard times. In fall of 2012 the building seemed slated for foreclosure, but then maybe not. Last month Gus Paras, a hero of my initial post, stepped forward and bought the old place. According to Joe Tarr in our politics and culture weekly Isthmus, there’s a lot of work to do.

Plaster is crumbling off sections of the ceiling, the result of years of water damage from a leaky roof. The walls are littered with scratches and marks, in bad need of a paint job. A plastic garbage can sits in the theater, collecting water leaking from an upstairs urinal. Paras even found dried-up vomit in two spots on the carpet.

Making matters worse, Monona State Bank, which controlled the property while it was in foreclosure, filled in the “vaults” behind the theater, which means replacing the building’s frail boilers and air conditioning will be much more complicated and expensive.

“I don’t have any idea how I’ll get the boiler in and out,” Paras says. “The stairs are not strong enough.”

Envoi

Have any of you worked on a film, say, 10 years ago, and it comes out on Blu-ray and you look at it and think, “This isn’t the film I’ve shot”?

Bruno Delbonnel (DP, Inside Llewyn Davis): Always. Always.

Barry Ackroyd (DP, Captain Phillips): I’ll be watching and it’s in the wrong format.

So what is it like to devote your lives and careers to creating images that you know exist only momentarily in their absolute best state, that may never be seen by most people the way you would like them to be seen?

Sean Bobbitt (DP, Twelve Years a Slave): At least you get a chance to see it once. All you can do is hope that people will see an approximation of that. I’ve been to screenings where I’ve had to get up and walk out because I just couldn’t bear to watch the film in the state it was in. But at the end of the screening, people say, “That was fantastic. That was beautiful. Well done!” and you’re thinking, “If only they had seen the real thing.” We would drive ourselves mad if we worried too much about it.

On shrinking windows, see Andrew Wallenstein and Ramin Setoodeh, “Exhibitors Explode over Netflix Bomb,” Variety (5 November 2013), 16. The chart on this page doesn’t appear in Variety‘s online edition of the story. Tania Loeffer’s report, “Transactional Movies: The Big Picture,” appeared in IHS Screen Digest (now IHS Media and Technology Digest) for April 2013, 123-126. Douglas Gomery discusses the theatre television plans of the 1940s-early 1950s in his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, pp. 231-234. My envoi comes from a revealing conversation among cinematographers at The Hollywood Reporter.

A 2012 catchup blog chronicling earlier phases of these developments is here.

P.S. 23 December 2013: David Strohmaier, the creative force behind the Cinerama restorations, has put online the stirring original trailers for Search for Paradise (low resolution and high-definition) . David attended the U of Iowa when Kristin and I did, though alas we didn’t meet him. He deserves a big thank-you for all his work in making these extraordinary films available to us.

The Grandmaster.

Poetics in motion, and sound

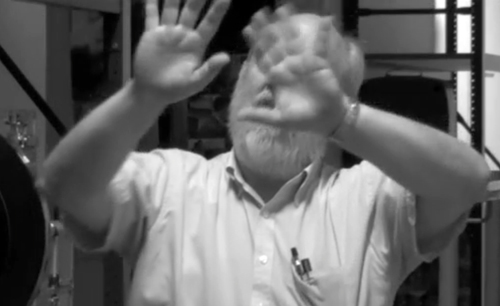

What is the sound of two hands flapping? (33:25).

DB here:

Ari Ernesto Purnama is a Ph.D. student in film studies at the University of Groningen. He has been attending the Belgian summer film schools I mentioned in the previous entry, and back in July he asked to interview me. He has kindly edited and posted the result on vimeo here.

The talk is about poetics of cinema as a research program, but I try not to get 100% hard-core academic. We discuss things like the long take, historical research into film style, and how the poetics perspective might be of interest to practicing filmmakers. Thanks to Ari and his DP Naki Naser Dauti for conducting this conversation.

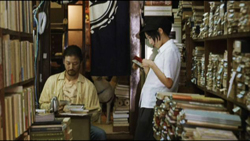

A better picture of me, in my prime, is below.

James Alexander and DB, May 1948. Thanks to Darlene Bordwell for the photograph, taken by Marjorie Bordwell.

Watch again! Look well! Look! (For Ozu)

Okada Mariko and Tsukasa Yoko with Ozu, on the set of Late Autumn (1960).

DB here:

Ozu was born on 12 December (in 1903) and died on 12 December (in 1963). He has been gone fifty years, yet his films are as fresh, inviting, funny, and moving as ever. As chance would have it, my book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema was published twenty-five years ago. Two events of the past few months have brought me back to him.

First, my biannual summer course in Antwerp, held under the auspices of the Flemish Film Foundation, was focused on him. As I’ve explained in earlier years (2011, 2009, 2007), at this Summer Movie Camp, across a week we immerse ourselves in films and wrap lectures around them. It was a joy to see a dozen of his films, mostly in good 35mm prints. Our sessions provided an occasion for me to rethink some things I said in the book, as well as to notice more about how these dazzling, apparently simple films work and work upon us. I learned as well from the comments and questions of many of the participants. The whole experience didn’t shift my opinion, stated on an earlier Ozu anniversary, that “no director has come closer to perfection.”

The second occasion: Two enterprising Ozuphiles have just published a collection of essays, Ozu à présent (Paris: G3j publishers). Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin have worked very hard for several years gathering pieces from filmmakers (Erice, Kurosawa Kyoshi) and critics like Hasumi, Frodon, Rosenbaum, and Jun Furita Hirose. Many other contributors have previously written on the director: Basile Doganis (Le Silence dans le cinéma d’Ozu), Benjamin Thomas (essays for Positif), and Clélia Zernik (Perception-cinéma). As for the editors, Diane has books on Sokurov and Kurosawa Kyoshi, while Mathias has written on Oliveira and art history generally. The entire collection is stimulating and beautifully produced.

The second occasion: Two enterprising Ozuphiles have just published a collection of essays, Ozu à présent (Paris: G3j publishers). Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin have worked very hard for several years gathering pieces from filmmakers (Erice, Kurosawa Kyoshi) and critics like Hasumi, Frodon, Rosenbaum, and Jun Furita Hirose. Many other contributors have previously written on the director: Basile Doganis (Le Silence dans le cinéma d’Ozu), Benjamin Thomas (essays for Positif), and Clélia Zernik (Perception-cinéma). As for the editors, Diane has books on Sokurov and Kurosawa Kyoshi, while Mathias has written on Oliveira and art history generally. The entire collection is stimulating and beautifully produced.

As the title indicates, it’s centrally about Ozu’s continuing influence on modern cinema. I was asked to contribute a preface, which Diane and Mathias have kindly allowed me to reproduce below in revised form. I’m now chiefly aware of what I neglected (no mention of Wenders’ Tokyo-Ga) and didn’t know about (for instance, Claire Denis’ admiration for Ozu). These and many other matters are taken up by the book’s contributors. But I think my piece may be of interest as a small update of my Ozu book.

In 1988, most of Ozu’s surviving films weren’t easy to access. Things have changed. And since I wrote the essay, virtually all the extant work has appeared on DVD, on cable television, and in the Criterion collection on Hulu Plus. As his films become more and more familiar, we can expect ever-greater acknowledgment of his centrality. Already, the 2012 Sight and Sound poll of critics put Tokyo Story just below Vertigo and Citizen Kane; the directors’ poll put it at the very top.

Why not watch an Ozu film today? Go beyond Tokyo Story, fine as it is, to Early Summer, Passing Fancy, Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, An Autumn Afternoon, The Only Son, The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, Ohayo, Diary of a Tenement Gentleman, What Did the Lady Forget?, Dragnet Girl, Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?, I Was Born, But… and on and on.

Catching up with Ozu

Ozu is a major presence in today’s international film culture. When I began seeing his work in the early 1970s, about half a dozen Ozu movies were in circulation, and of those only Tokyo Story was known to nonspecialist cinephiles. As late as the 1980s, I had to travel to archives in Europe and the US to see his rarer films. Now even the most obscure early 1930s titles are issued on DVD, and the films have been widely distributed in touring packages. They are screened all over the world, a process lovingly recorded on Twitter. Ozu is better known to a broad public than Mizoguchi Kenji is—an ironic turn of affairs, given that in many countries Mizoguchi gained fame during the 1950s and 1960s, when Ozu was unknown.

Even more famous throughout the west was, of course, Kurosawa Akira. His influence on mainstream cinema has been robust and pervasive. If slow-motion violence has become a convention in American films since Bonnie and Clyde, that is directly traceable to the director of Seven Samurai. The use of very long lenses to cover a scene, common in American cinema of the 1960s and thereafter, owes a great deal to Kurosawa’s strategies in films like I Live in Fear and Red Beard. Editing on the camera axis for visceral impact, a Kurosawa signature technique, has bumped up the visual excitement in many American action pictures.

Ozu has not had such a direct influence. He is much less easy to assimilate. With few exceptions, his signature style has been far less imitated, and it has even been misunderstood. His effect on modern cinema, it seems to me, has been far more oblique, with directors paying him tribute in discreet, sometimes unexpected ways.

Brand Ozu

Ozu wing, Kamakura Cinema World, 1996.

Ozu was careful to mark his uniqueness. He designed his films to be sharply different from those of his contemporaries. His home base, the Shochiku studio, encouraged directors to develop personal styles, and he was allowed to make artistic choices that could only be considered eccentric. At first glance, Ozu’s films may seem to melt into a broader idea of “Japanese artistic culture,” but the more films we see by his colleagues, the more idiosyncratic his works look.

Having allowed Ozu to make such singular films, Shochiku has exacted a reciprocal obligation: his legacy now serves as a trademark for a film studio. For the world at large, Japanese cinema consists of Kurosawa and Toho studios’ Godzilla, Nikkatsu action, and anime. Shochiku had its tradition of modest, humane dramas of working-class and middle-class people, treated with that mixture of humor and tears known as the “Kamata flavor” (after the Tokyo suburb where the studio was located). That tradition was sustained by Ozu and his colleagues through the 1950s as a brand identity. The forty-eight Tora-san films (Otoko wa tsurai yo, “It’s Tough to Be a Man”) became what we’d call a frachise for Shochiku from 1969 through 1996.

But as media became globalized, and as merchandising became central to sustaining filmmaking, Shochiku’s product came to seem narrowly local. Accordingly, the firm turned its attention to its most famous employee. Shochiku’s familiar postwar logo, a view of Mount Fuji, had become for westerners part of Ozu’s iconography.

Now Shochiku tried to reclaim its trademark by reminding viewers that he belonged to a bigger family.

For the local market, Shochiku tried a bit of merchandising, such as phone cards with scenes from Ozu movies. More ambitiously, there was Shochiku Kamakura Cinema World, a theme park established in 1995 at a cost of $125 million. It held many attractions devoted to American cinema, and it even allowed customers to visit a movie in the making, but one wing was devoted to Shochiku’s legacy properties, including a replica of a street from the Tora-san series. There were as well Ozu memorabilia, including a three-dimensional tableau of an effigy Ozu directing a scene in Tokyo Story. The adjacent vitrine housed a reconstruction of his work area at home, complete with whisky bottle and bright red rice kettle.

Cinema World closed in 1998, a financial failure. But Shochiku persisted and declared in 2003 that it would host a worldwide celebration of Ozu’s hundredth anniversary. That celebration consisted of a new touring program of 35mm prints of his films, with ancillary ceremonies and festival activities, and several new DVD releases. Shochiku went further and commissioned Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumière, a film in homage to the great director. For festivals and arthouse cinemas, Hou’s tribute was aimed to recall Ozu’s greatness and, by association, Shochiku’s place in film history.

As directors have sought to retain the Kamata flavor in later decades, we find hints and traces of Ozu as well. A film like 119: Quiet Days of the Firemen (1994), in which middle-aged men in a small village fantasize about romance with a young researcher, might bring to mind the overactive imaginations of the grown-up schoolboys of Late Autumn (1960). Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Still Walking (Aruitemo aruitemo, 2008) is a family drama made in full awareness of the Ozu tradition. Not surprisingly, Yamada Yoji, impresario of Tora-san, has invoked the Shochiku tradition in several productions (notably Kabei: Our Mother, 2008, and Ototo, 2010). At the start of 2013 Yamada, at 81 years of age, released an updated remake of Tokyo Story.

Ozu comes to America

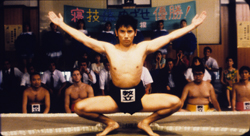

Days of Youth (1929).

Since at least the early 1920s, the Japanese cinema has responding to the American cinema. During the classic period, American films did not dominate the Japanese market, as they did in many other countries, but filmmakers were nevertheless acutely conscious of Hollywood. In particular, the founding of Shochiku in 1920, with a self-consciously modernizing orientation under Kido Shiro, created a ferment that changed Japanese cinema forever.

Like other Kamata/ Ofuna directors, Ozu relied crucially on American cinema. There are visual citations (the Seventh Heaven poster in Days of Youth), lines of dialogue about Gary Cooper and Katharine Hepburn, borrowed gags (from A Sailor-Made Man in Days of Youth), and even an extract from If I Had a Million in Woman of Tokyo. More deeply, his early films absorbed the analytical editing of 1920s Hollywood. He broke every scene into a stream of precise, slightly varied bits of information in the manner of Ernst Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd.

Ozu paid American cinema a deeper tribute. Having grasped that system of axis-of-action continuity that Hollywood had forged from the late 1910s, he created his own system as an alternative. Instead of a 180-degree organization of space, he proposed a 360-degree one. This allowed him to absorb the Americans’ innovations and yet give them a new force. Cuts would use eyelines, shoulders, and character orientation, but would often show characters looking in the same direction, their figures and faces matched pictorially from shot to shot.

A cut on movement could be made by crossing what American directors called “the line.”

Further, Ozu realized that the establishing shot, that depiction of the overall space of the action, could be prolonged and split into several shots. The result was a suite of changing spaces that could be unified by shape, texture, light, or even analogy (one window/ another window). These transitional sequences substitute for fades and dissolves, turning ordinary locales into something at once evocative and rigorous.

All of these transformations of Hollywood’s stylistic schemata are rendered more palpable by a single, simple choice that is more single-minded than anything to be found in Hollywood: The camera is typically placed lower than its subject. This constant framing choice acts as a sort of basso continuo for the melodic variations Ozu will work on two-dimensional composition and three-dimensional staging.