Archive for June 2022

Lie to me: MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE

Mission: Impossible (1996).

DB here:

Filmmakers rightly consider themselves problem-solvers. They deal with budget limits, scheduling constraints, temperamental staff and casts, and balky equipment. Some problems come with financial demands; others are self-imposed, such as: “Tell a story confined to a single room.” The artistic problems often demand solutions that guide viewers toward clarity, comprehension, and emotional impact.

Suppose your story situation is this. Character A is telling a story, but it’s a lie. Character B realizes it’s a lie, but doesn’t signal that recognition. This is really two problems in one: How do you tell the audience A is lying? And how do you convey that B knows but doesn’t reveal that knowledge?

These are at the crux of in an intriguing sequence in Mission: Impossible. The solutions found by screenwriter David Koepp and director Brian DePalma show how even a straightforward “entertainment movie” can pose interesting questions about cinematic expression.

Spoilers ahead. But I bet you’ve seen this movie.

The problem(s)

The Impossible Mission team has been sent to Prague, purportedly to retrieve a digital disc listing all CIA agents in Europe. They don’t know that this assignment is a pretext for finding a mole, a rogue agent who is selling secrets to foreign interests. While infiltrating a state gala, most of the team is killed. Only Ethan Hunt, point man in the mission, and Claire Phelps, the wife of the team leader Jim Phelps, survive. The IMF chief Kittridge accuses Ethan of being the mole so Ethan, along with Claire, needs to flee. But out of devotion to duty he insists on finding the mole. He learns that the mole under the alias of Job has offered to sell the NOC list to Max, a dealer in covert information. The bulk of the plot revolves around Ethan’s efforts to induce Max to reveal Job, which Ethan can do only by offering Max the NOC list—while at the same time making sure that it doesn’t really fall into Max’s hands.

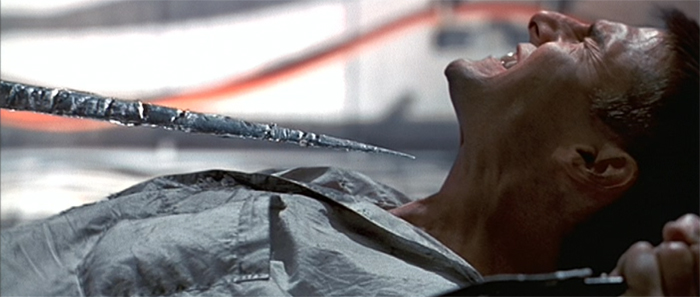

After a prologue, which I discussed in an earlier entry, the film’s first stretch revolves around the team’s invasion of the embassy party. As the scheme collapses, we see the deaths of the team members. Through cross-cutting and a moving-spotlight narration, the film shows us the technician Jack killed in an elevator shaft, Jim Phelps shot on a bridge and tumbling into the river, Sarah stabbed at a gate, and Hannah killed by a car bomb. The effects of these killings are registered largely through Ethan’s response. He hears Jack lose contact, watches video transmission of Jim’s bloody hands, finds Sarah impaled by a knife, and sees Hannah’s car explode. Later he, and we, will learn that Claire escaped.

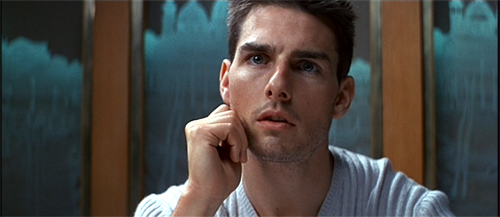

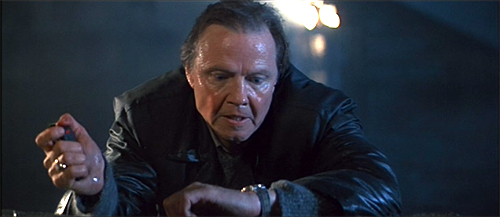

At the start of the film’s climax, Ethan discovers that Jim Phelps is still alive. In a café, Jim explains that he survived the shooting and that he saw the killer: Kittridge. Kittridge is the mole, he claims. Jack brings Jim into his plan to meet Max on the Eurostar train and apparently give her the NOC list he’s stolen from Langley.

The twist is that Jim–Ethan’s mentor, friend, and surrogate father–is lying. He is Job the mole, and he has eliminated his own team, faking the attack on himself. Thanks to crosscutting, the first version of the attacks concealed from us the actions Jim takes to kill his colleagues. The narrative problems are: How and when to tell us of Jim’s treachery? And how to represent Ethan’s state of awareness? Is he misled by Jim’s account, or does he doubt it? And what is Claire’s role in all this?

Three solutions

Singin’ in the Rain (1952).

Every creative choice eliminates alternatives, and I’ve compared classical filmmaking to selecting from a menu of more or less favored options. That menu can offer filmmakers ways of solving narrative problems. One choice for the M:I revelation is simply to present Jim telling Ethan his lies in the café. Ethan then can react in horror, leaving us to assume that he doesn’t doubt him.

This option was actually tried out in an early script draft. Jim explains and Ethan, despite some hesitation (“Hold on, it’s taking me a minute to adjust here“), seems to accept his story. Only in their final confrontation on the Eurostar does Ethan reveal that he had long before figured out that Jim had betrayed the team. We had no inkling that in the café Ethan was merely pretending to accept Jim’s account. His awareness of Jim’s scheme was held back as a surprise.

Another narrative option appears in a later script draft. This time Jim’s explanation is accompanied by flashbacks illustrating his lies. He claims to have swum to shore, patched up his gunshot wound, and followed Ethan’s trail. He then tells Ethan it was Kittridge who shot him and killed Sarah, and these moments are illustrated with quick flashback imagery. These are lying flashbacks. As a neat fillip, two of these shots replay Ethan finding Sarah’s body nearby, as if to certify Jim’s story. “Ethan just stares at Phelps, his eyes wide with surprise.” Again, we’re led to think that Ethan trusts Jim’s tale, making the train confrontation a revelation of Ethan’s outplaying Jim.

We should remember that the Hollywood menu provides the lying flashback as an option, albeit rare. In Singin’ in the Rain, for instance, Don Lockwood’s voice-over interview portrays his early career as one of refined show-business accomplishment. “Dignity—always dignity.” But the images undercut this by showing him performing slapstick routines in burlesque. Since this is a comedy, we can understand that the film’s flashbacks are debunking his pretension. As for the second problem, that of conveying a listener’s skepticism, the present-time scenes reinforce the impression of Don’s puffery by showing his pal Cosmo’s eye-rolling reaction. Still, the interviewer and presumably the radio audience are taken in.

This second M:I script variant doesn’t include such hints that Ethan doubts Jim, so the problem of the conveying the listener’s true reaction is bypassed. But the final film supplies yet another solution.

After I drafted what you’ve just read, I heard from screenwriter David Koepp. I had written him to ask about the alterations, and he talked with De Palma about them.

Brian reminded me that the intention of the scene was built around an idea — can we show Jim lying, and simultaneously see Ethan figuring out those lies in his own mind? Without telling Jim that he knows it’s a lie, Ethan is picturing for us what the truth must (or might) have been. It’s a cool idea, and, typical of DePalma, highly visual. Actually seeing on screen versions of events that may or MAY NOT have happened is something we started playing around with in M:I, and then did to a greater degree in Snake Eyes, which we wrote right after that.

Neither one of us can remember in useful detail about why we might have tried several other versions first, but my guess is that the one with Jim simply verbalizing the lie was jettisoned in favor of images for obvious (and again, DePalma-esque) reasons, i.e., it’s better to see something than to hear it. The flashback showing Kittridge as the perpetrator was likely because we wanted to keep going for as long as possible with the character I’ve come to call the Principled Antagonist — POSSIBLY a villain, turns out not to be, but always diametrically opposed to the hero and his goals.

It was good to have my hunch confirmed, and to watch filmmakers sampling the menu of options from draft to draft. The final shooting script presents the new variant. Ethan, not Jim, spells out the scheme in dialogue. This leads Jim to assume that Ethan accepts Kittridge as the culprit. But the image track shows Jim committing the crimes. As the script puts it:

A reprise of PHELPS’s narrative only now ETHAN’S telling it and camera is showing the events as ETHAN sees they actually happened.

There’s still a potential obstacle, though. What if the viewer takes the flashbacks to show what really happened but doesn’t grasp that they’re Ethan’s imaginings? They might be only “the film telling us what really happened,” as in Singin’ in the Rain. How to establish that we’re following Ethan’s train of thought while he lies during his dialogue with Jim?

How to lie to a liar

Here’s the sequence as it appears in the film.

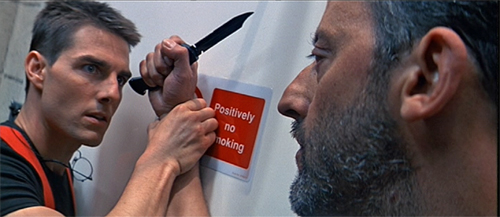

On the first problem, the sequence makes clear that Jim’s accusation of Kittridge is false. We’re introduced to Jim’s treachery with several shots showing Jim engineering Jack’s death in the elevator. Several more shots, stressed through slow-motion, illustrate how Jim faked his own death. And the knifing of Golitsyn and Sarah is attributed to Krieger. You can also argue that wily viewers will take Jim’s sidelong glance at Ethan as a tip-off to his treachery–a classic shot lingering on the Guilty One (as we’ve seen elsewhere).

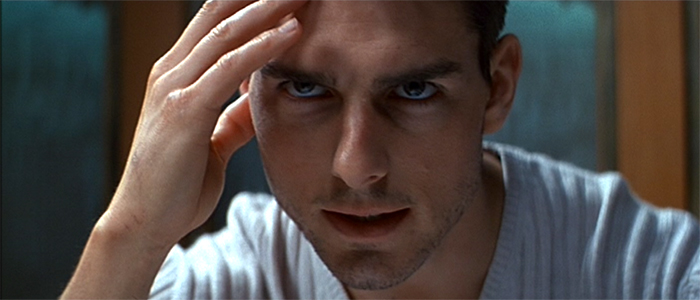

Still, how can we be sure that Ethan sees “events as they actually happened”–especially since his shock and puzzlement at hearing Jim’s tale seem so genuine?

The sequence solves the second problem with two passages that strongly imply that the flow of images reflects what’s in Ethan’s mind.

First, among phases of the stabbings at the gate, there’s the interpolated shot of Ethan pinning Krieger’s wrist to the wall during the Langley heist.

The two-shot of Ethan and Krieger, a flashback not part of Jim’s story, indicates Ethan’s realization that the knife he found in Sarah’s side was one of Krieger’s. Interestingly, this shot isn’t in the shooting script.

A stronger cue that we’re in Ethan’s mind comes with the “revised and corrected” version of Hannah’s death. Did “backup” take her out? The answer comes with a shot of Claire triggering the explosion and turning to look at the camera.

Claire’s look defies plausibility. It’s as if she is turning to glare, almost defiantly, at the Ethan who’s imagining this. Because he’s attracted to Claire, he wants to give her the benefit of the doubt. His imagination immediately proposes an alternative in which Jim sets off the bomb.

In the train at the climax, Jim will confirm Ethan’s hesitation: he was reluctant to suspect Claire. In the later stretch of the café scene, not included in my extract, the question of her loyalty is evoked as Jim urges Ethan to keep quiet about the scheme. When Ethan returns to Claire at the safe house, there remains the issue of whether her seduction of him is sincere or a further act of betrayal.

More immediately, the two problems are solved. Not only do we have the exposure of Jim’s lie, but we also get glimpses of how Ethan reconstructs what really happened. What makes this all particularly clever is that Ethan’s dialogue seems to confirm Jim’s tale. Ethan’s verbal duplicity is consistent with his talent for bluffing (as with Krieger and the fake NOC disc) and the earlier twinge of suspicion he had about Jim’s Palmer House Bible. When image and sound contradict one another here, we’re obliged to trust the image.

All of which charges Ethan’s final question–“Why, Jim? Why?”–with a double significance. Apparently asking about Kittridge’s motive, Ethan is pressing his mentor, almost desperately. Jim’s answer, about a refusal to accept the end of the Cold War, applies as much to him as to a CIA bureaucrat. We may not fully recognize it at the moment, but Ethan’s question marks the end of their friendship.

Someone might ask if every audience member will realize that the sequence solves both problems. Presumably even a ninny understands that Jim is lying; but maybe some viewers don’t get that Ethan is aware of the lie. My own inclination is to see the cues of Krieger’s knife and the revised version of Hannah’s death as pretty solid hints. Still, we might be in the realm, not unknown to Hollywood cinema, of a film that includes subtleties that not every viewer catches. I’m reminded of a screenwriter’s remark: “It’s not necessary that every viewer understand everything, only that everything can be understood.” This is presumably one reason we return to films and find more in them.

It’s also one reason it’s fun to analyze them.

Thanks to David Koepp and Brian De Palma for responding to my questions. David’s script archive is here.

The remark about understandable stories comes from Ted Elliott, as quoted in Jeff Goldsmith, “The Craft of Writing the Tentpole Movie,” Creative Screenwriting 11, no. 3 (May/ June 2004):, 53.

Mission: Impossible (1996).

Noir x 3

Repeat Performance (1947).

DB here:

For several years, the Film Noir Foundation has initiated recovery and restoration of a great many neglected films, mostly from Hollywood. Thanks to Flicker Alley, several of those have made their way to DVD and Blu-Ray. (Earlier blog entries have considered the editions of Trapped and The Man Who Cheated Himself.) Now come two more discs, with beautifully restored copies and informative supplements.

The Monogram Touch

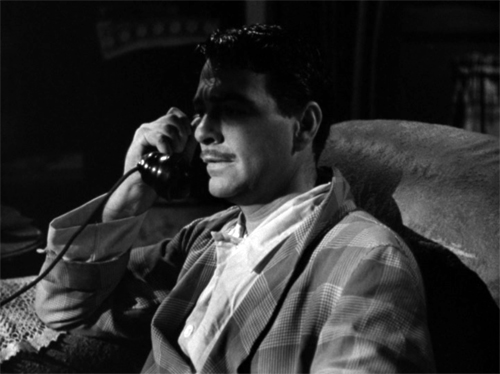

The Guilty (1947).

A generous double-feature disc displays what smooth B-filmmaking can look like. High Tide (1947) tells of Tim Slade, a rogue reporter brought back to work under his tough editor, Hugh Fresney. Fresney wants Tim’s help in taking on the city’s crime syndicate. Tim’s position is complicated by his past affair with the wife of the paper’s publisher, who’s hesitant to challenge the mob. A secret file on the gang becomes the target of Tim’s investigation, leading to an amiable former reporter Pop Garrow. The reversals pile up and lead to a surprise revelation at the climax.

A generous double-feature disc displays what smooth B-filmmaking can look like. High Tide (1947) tells of Tim Slade, a rogue reporter brought back to work under his tough editor, Hugh Fresney. Fresney wants Tim’s help in taking on the city’s crime syndicate. Tim’s position is complicated by his past affair with the wife of the paper’s publisher, who’s hesitant to challenge the mob. A secret file on the gang becomes the target of Tim’s investigation, leading to an amiable former reporter Pop Garrow. The reversals pile up and lead to a surprise revelation at the climax.

A noteworthy feature is a significant gap in a key scene. I can’t say more here, but the audio commentary by Alan K. Rode explains that although the complete scene is in the script, every print he has seen contains this omission. He speculates it might have been cut to shorten running time. I also wondered whether, since the print is a British one, the portion might have been snipped for censorship reasons. Interestingly, the AFI plot synopsis includes the scene. But 1947 sources give the original running time as 70 minutes, the same as the version we have, so the mystery remains.

Like other 1940s films, High Tide has a crisis structure. It starts with Tim and Fresney trapped in a car about to be swamped by the incoming tide. We then flash back to the events leading up to that. Director John Reinhardt and cinematographer Henry Sharp give us crisp, no-nonsense scenes making flexible use of depth staging (often to set Tim off as observer) and offering the occasional eye candy.

The main attraction on this double bill is The Guilty. It’s based on a Cornell Woolrich story, first titled “He Looked Like Murder” and republished as “Two Fellows in a Furnished Room.” As with most Woolrich adaptations, the film changes the original considerably. Mike Carr’s roommate Johnny Dixon is accused of murdering Linda Mitchell, twin sister to Estelle (Bonita Granville in a dual role). Dixon goes on the run while Carr investigates and maintains his rough-edged affair with Estelle.

Woolrich’s story doesn’t give us twin sisters or a romantic plot; the emphasis falls on Carr’s disintegrating relation with his roommate. The clues are much the same, but the film adds a flashback structure, with Carr narrating past events to a bartender (and us) as he waits for Estelle. The short story’s solution is predictable, while the film offers a twist ending, heightened by a nifty slippage of that voice-over.

The film’s plot sacrifices coherence for its surprise finale, but the overall result is pretty impressive for a two-week shooting schedule. Out of a few cheap sets, Reinhardt and Sharp create a varied range of angles and modulated lighting.

The film is exceptionally free of gunplay and other violence, but that lack is made up by a remarkable scene in a morgue. The police detective is describing to Carr how Linda was killed. As he stands by the mortuary drawer, his dry account of the grisly murder is chilling. (Once more, sometimes telling beats showing.) It’s close to the same scene in the original story. As Eddie Muller indicates in his introduction, it’s the most shocking scene in the film.

The Guilty also spares time for images that foreshadow the outcome, as in ominous high angles of a street. There’s also the sort of evocative superimpositions that Hollywood occasionally supplies. A purely functional shot of the morgue drawer sliding shut dissolves to a shot of Estelle in bed, at once substituting for her sister and looking ahead to her as a possible victim.

The Guilty typifies the sort of film that deserves to be recognized as a part of a fine Hollywood tradition—the well-made B. I had never seen it or High Tide before, and they reminded me of what could be done at the studio that also gave us the Bowery Boys, Dillinger (1945), and King of the Zombies (1941).

The future’s gonna change

Calling Repeat Performance (1947) a film noir illustrates how elastic the label has become. Yes, it begins with a murder in the manner of Mildred Pierce (1945). There’s a flashy use of chiaroscuro at its climax (surmounting this entry). It’s directed by the elusive Alfred Werker, who signed the woman-in-peril thriller Shock! (1946) and was involved with He Walked by Night (1948). But as Daily Variety’s review pointed out, it’s less a crime story than a “suspense melodrama.” And it traffics in supernatural explanations.

Eddie Muller’s introduction points out that a noir like Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) also invokes otherworldly forces. But like the Guilty adaptation, the source has been heavily altered. William O’Farrell’s novel Repeat Performance is told from the viewpoint of a man being hunted for strangling his wife. It’s a thriller more closely tied to the conventions of what we think of as noir. By switching the action to the viewpoint of the wife, and eliminating the police pursuit, the film gives us something closer to another cycle of the 1940s.

Eddie Muller’s introduction points out that a noir like Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1948) also invokes otherworldly forces. But like the Guilty adaptation, the source has been heavily altered. William O’Farrell’s novel Repeat Performance is told from the viewpoint of a man being hunted for strangling his wife. It’s a thriller more closely tied to the conventions of what we think of as noir. By switching the action to the viewpoint of the wife, and eliminating the police pursuit, the film gives us something closer to another cycle of the 1940s.

During that decade, filmmakers continued a Hollywood vein of fantasy—most obvious in the ghost films that proliferated, but also in tales of divine intervention by angels and other forces. Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941) and It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) visualize alternative futures for their protagonists. Portrait of Jennie (1949) suggests a time stream operating alongside that of normal life, and some films with prophetic dreams suggest that the characters’ fates are determined.

Other media dabbled in the alternative-universes premise. Most famously, J. B. Priestley experimented with forking-path plots in the play Dangerous Corner (1932). (I talk about the film version here.) His later dramas, such as Time and the Conways (1937) and I Have Been Here Before (1937), pursue parallel timelines, but the closest to Repeat Performance, I think, is his remarkable “mystery” An Inspector Calls (1945).

It’s no spoiler to say that the plot of Repeat Performance restarts the time scheme of the action. On New Year’s Eve, as 1947 starts, the actress Sheila Page shoots her husband Barney. But as she leaves the murder scene, she enters the world a year earlier, on the first day of 1946. As the voice-over narration explains, she will relive that year.

After Sheila understands that she has a reprieve, she sets out to change the events that led up to her crime. She tries to keep Barney sober and focused on writing his next play, and above all she struggles to keep her rival Paula Costello away from him. She wants, she says, to “rewrite the third act.” Yet even when she changes the circumstances, accidents intervene to block her efforts. She fears that the onset of 1947 will drive her to kill again. Can she thwart destiny?

The result yields a satiric portrait of Broadway backstabbing, while cleverly suggesting that the changes in Sheila’s future are like revisions of a play in production. During a rehearsal, she suggests improving Act II by “playing it backwards”—that is, putting the scenes in reverse order. Yet they yield the same consequences, just as she will learn that her fate doesn’t care about the particular patterning as long as “the result is the same.”

Like Back to the Future (1985), the film is a time-travel adventure that aims to reset the past. It reminds us that a lot of modern movie storytelling consists of shrewd revisions and updatings of premises that had their sources in earlier Hollywood periods—particularly the 1940s. Fans of The Twilight Zone will have fun with Repeat Performance.

The Film Noir Foundation’s releases abound in no-nonsense supplements. They’re full of historical background to the films, the companies, and the personnel. On these two discs we get a detailed study of producer Jack Wrather, a rich account of the Eagle-Lion company, career summaries of Cornell Woolrich, John Reinhardt, Lee Tracy, and Joan Leslie, a pressbook for Repeat Performance, and informative liner notes. These put us in the debt to filmmaker Steven C. Smith and film historians Alan K. Rode, Eddie Muller, Imogen Sara Smith, Farran Smith Nehme, Brian Light, and many interviewees. Not only the films but the bonus materials are excellent additions to a cinephile’s collection.

The Daily Variety review of Repeat Performance is in the issue of 23 May 1947, p. 3. For my take on Cornell Woolrich and cinema, go here. I discuss Repeat Performance along with other fantasy-laden films of the period in Reinventing Hollywood: How Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, chapter 9.

Repeat Performance (1947).