Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Crime spree

Patricia Highsmith (from Loving Highsmith, 2022).

DB here:

Crime fiction, whether in words or pictures, is a bigger category than we might initially think. There are whodunits, hardboiled detective stories, police procedurals, suspense thrillers, and stories of gangsters, professional crooks, and petty scoundrels (e.g., Elmore Leonard’s world). That’s a lot in itself. But since every plot of any interest depends on some disruption of a stable situation, an illegal transgression can do the trick. So we can get bank robbery in a comedy (e.g., Take the Money and Run, 1969), or murder and extortion in a family melodrama (The Little Foxes, play 1939, film 1941), or authorial disputes about plagiarism (Secret Window, 2004). Even romantic comedy has room for a crime or two (Date Night, 2010).

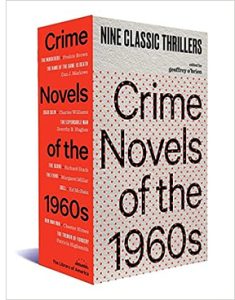

Geoffrey O’Brien is a polymath. He’s written poetry, evocative memoirs (Sonata for Jukebox, 2004), experimental fiction (the recent lyrical “fantasia,” Arabian Nights of 1934), and outstanding literary and film criticism (Castaways of the Image Planet, 2002). He’s also an expert in crime fiction (Hardboiled America, 1997), so he’s ideal for editing the new Library of America collection Crime Novels of the 1960s. His choices, all unimpeachable, cover a lot of the central creative options. There are crook stories, suspense thrillers, a police procedural, several strains of whodunit, psychological studies, and at least one crime novel possibly lacking a crime. In style they vary between pitiless hardboiled narration and more delicate but still forceful dissection of middle-class mores. As you might expect from books of their era, racial prejudice, urban upheavals, and the folkways of the counterculture are seldom far away.

Geoffrey O’Brien is a polymath. He’s written poetry, evocative memoirs (Sonata for Jukebox, 2004), experimental fiction (the recent lyrical “fantasia,” Arabian Nights of 1934), and outstanding literary and film criticism (Castaways of the Image Planet, 2002). He’s also an expert in crime fiction (Hardboiled America, 1997), so he’s ideal for editing the new Library of America collection Crime Novels of the 1960s. His choices, all unimpeachable, cover a lot of the central creative options. There are crook stories, suspense thrillers, a police procedural, several strains of whodunit, psychological studies, and at least one crime novel possibly lacking a crime. In style they vary between pitiless hardboiled narration and more delicate but still forceful dissection of middle-class mores. As you might expect from books of their era, racial prejudice, urban upheavals, and the folkways of the counterculture are seldom far away.

Taking pulp mainstream

The nightmarish plots and staccato vernacular of O’Brien’s hardboiled sampling are vestiges of the pulp magazines, where Hammett and Chandler developed their technique in the 1920s and 1930s. But the classic crime pulps were long gone by the 1960s. What replaced them were the massive paperback originals pouring from presses from the Forties onward. A first paperback printing of a novel would routinely run to 150,000 copies. The success of cheap reprints of hardcover titles impelled publishers to capitalize on the new market with novels written specifically for paperback distribution. The most popular genre was crime fiction. Originals tended to be short, running 60,000 to 80,000 words, with plenty of blank space for laconic dialogues. A dedicated pro could turn out one in a month or two, at a fee of a few hundred dollars.

A vivid example in this collection is Dan J. Marlowe’s The Name of the Game Is Death, which first appeared as a Fawcett Gold Medal paperback in 1962. It starts with three thieves executing a bank robbery. The opening plunges us into the crossfire of pulp narration.

A vivid example in this collection is Dan J. Marlowe’s The Name of the Game Is Death, which first appeared as a Fawcett Gold Medal paperback in 1962. It starts with three thieves executing a bank robbery. The opening plunges us into the crossfire of pulp narration.

Bunny went through the front door in a sliding skid. The kid took one look at my face and started to run back in front of the Olds. Across the street something went ker-blam!! The kid whinnied like a horse with the colic. He ran in a circle for three seconds and then fell down in front of the Olds, his white cottom gloves in the dirty street and his legs still on the sidewalk. The left side of his head was gone.

Bunny dropped the sack and scrambled for the wheel. I was halfway into the back seat when I heard the car stall out as he tried to give it gas too fast. It was quite a feeling. I backed out again and faced the bank, tried to have eyes in the back of my head for the unseen shotgunner across the street, and listened to Bunny mash down on the starter. The motor caught, finally. I breathed again, but a fat guard galloped out the bank’s front doors, his gun hand high over his head.

I swear both his feet were off the ground when he fired at me.

Bunny flees with most of the loot, and our nameless narrator escapes alone. He waits for news that Bunny has found sanctuary and is ready to divide the take. When the narrator hears nothing, he worries that Bunny is in trouble and sets out to find him. In his travels from Phoenix to Florida he encounters several problems that demand violent solutions. Across his trip, it becomes evident that our protagonist is a borderline sociopath.

His journey gives Marlowe’s plot a linear trajectory that is studded with flashbacks to his childhood, including a traumatic incident with his beloved cat. The episodes build a degree of understanding of his damaged personality, only to have that mitigated by a savage climax. Hardboiled to the end.

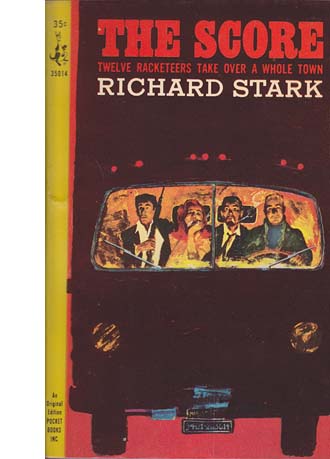

Donald E. Westlake, a favorite of this blog, was endlessly prolific, cranking out erotica, science fiction, comic fiction, psychological thrillers, and hard-core crime stories under several pseudonyms. He created two long-running series, both based on heist plots. A comic one centered on John Dortmunder, a hapless down-at-heel thief. The other series was dead serious (though with some light touches) focused on Parker, an impassive, nearly amoral robber specializing in organizing big capers. The Score (1964) is one of Parker’s most ambitious projects. With a large team, he ransacks an entire town.

Donald E. Westlake, a favorite of this blog, was endlessly prolific, cranking out erotica, science fiction, comic fiction, psychological thrillers, and hard-core crime stories under several pseudonyms. He created two long-running series, both based on heist plots. A comic one centered on John Dortmunder, a hapless down-at-heel thief. The other series was dead serious (though with some light touches) focused on Parker, an impassive, nearly amoral robber specializing in organizing big capers. The Score (1964) is one of Parker’s most ambitious projects. With a large team, he ransacks an entire town.

Westlake broke nearly all his Parker novels into four parts, and within them he enjoyed mixing flashbacks and shifting viewpoints. Part 3 of The Score is a virtuoso panorama of the entire raid, played out in short scenes in different parts of town. It provides a careful layout of how the takeover is engineered. Most scenes are devoted to the robber in charge and provide us characterization that enlivens the action. As usual, the perfect heist goes badly wrong, and Westlake’s anatomy of the scheme forces us to admire its precision up until the final catastrophe.

Westlake exemplifies how the hardboiled tradition could be exciting without being sensationalistic. Avoiding the near-hysteria of Marlowe (no double exclamation points here) and the florid metaphors of Chandler, Westlake is close to Hammett in his understated but elegant style. He playfully references books and movies, as when Parker’s colleague Grofield imagines his thieving days as a long film with a musical score and swooping camera angles. I devoted a chapter of Perplexing Plots to the rigorous intricacy and captivating style of the Parker books. (For online instances, go here and here.)

Hitchcock and Evan Hunter (Ed McBain), who wrote the screenplay for The Birds.

The Score was a paperback original for Pocket Books, which also initiated Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct series. McBain’s police procedurals mixed a realistic treatment of procedures (printed-out lab reports, fingerprint files, and the like) with a slangy dialogue redolent of the hardboiled pulps. Doll (1965) includes not only a gory murder but a series of punishing scenes in which a killer repeatedly injects a captive cop with heroin.

McBain sought to capture the protocols of investigation through the “conglomerate hero” formed by an entire squad. Although Steve Carella is the first among equals, inquiries get split up among his colleagues. In Doll Carella is reluctantly partnered with the troubled Bert Kling. But Carella soon disappears and is believed dead. Kling continues solo until he’s replaced by Meyer Meyer, who’s aided by colleagues Hal Willis and Arthur Brown. Eventually Kling rejoins the hunt and partners with Meyer to resolve the case. In other books, cases run in parallel or are revealed as connected. This sort of plotting, popularized in Hill Street Blues, is common in modern procedurals. McBain complained that others swiped his idea.

Another McBain innovation was an intrusive authorial voice. The action is typically recounted in the third person and through shifting viewpoints in a moving-spotlight manner, but the narration injects digressions and ventures into sheer chattiness. The opening of Doll interrupts the scene of a grisly murder with a lengthy reflection on how police cope with unimaginable crime scenes. This meditation isn’t attributed to Carella or anyone else. McBain, who was an English major in college, deliberately flouted the demand for neutral narration.

I know that in these books I frequently commit the unpardonable sin of author intrusion. Somebody will suddenly start talking or thinking or commenting and it won’t be any of the cops or crooks, it’ll just be this faceless, anonymous “someone” sticking his nose into the proceedings. Sorry. That’s me. Or rather, it’s Ed McBain.

McBain’s string of police procedurals quickly graduated to hardcover publication by Delacorte Press. His success exemplifies the new respectability of the pulp tradition.

The insanely prolific Fredric Brown gets some respectful mentions in Perplexing Plots for eccentric experiments like The Far Cry (1951). Echoes of the hardboiled school show up more mutedly in his The Murderers (1961). The protagonist, a shiftless would-be actor, drifts through Hollywood trying to pick up commercial gigs or small parts in an ongoing TV series. Mostly he’s interested in drinking and hanging out with hippies and pliable women. He gets attached to a businessman’s wife, and together they fumble into a murder scheme. There’s more than a passing resemblance to Double Indemnity, and the hero is a softer, semi-comic descendant of James M. Cain’s doomed fools for passion. Overall, Brown presents a cooler, more laid-back vision of Cain’s sunbaked California car culture and killing fields. As a bonus, Brown merges his murder scheme with another swiped ingeniously from the most prominent woman writer of psychological thrillers.

Murder with gravity

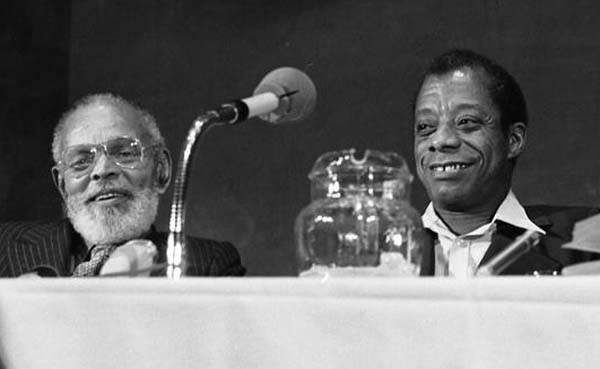

Chester Himes and James Baldwin, 1973. From Stars and Stripes.

Late one night a drunken, psychopathic cop shoots and kills a restaurant’s two kitchen cleaners. A third man witnesses the crimes and escapes. The cop uses all the authority of the law to pursue him. Moving-spotlight narration switches us rapidly from one man to the other as the tension builds and the cop closes in.

Sounds like pure pulp, no?

What if the cop is a racist, and his two victims and third target are Black?

That’s the premise of Chester Himes’ Run Man Run (1966). Himes was one of several Black artists and writers who found sanctuary in Paris after confronting postwar bigotry at home. He won fame in France, and belatedly in the U.S., with a series of hardboiled detective novels (some as paperback originals) centering on Gravedigger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson. The best-known is Cotton Comes to Harlem (1966), which also became a lively movie.

His marquee cops are absent from Run Man Run, but the book is filled out by evocative descriptions of the Harlem milieu and sharp portrayals of the secondary characters, particularly the pursued man’s morally equivocal girlfriend and a cop who’s not as racist as his peers. The density of detail and the psychological probing of hunter and hunted give the book the gravity of a “serious” novel like Himes’ excellent If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945).

Gravity of a comparable sort dominates Charles Williams’ Dead Calm (1963). The situation merges two long-lasting schemas: the woman menaced by the sociopathic killer, and the man trapped aboard a sinking ship. A couple honeymooning in a yacht come to the aid of an apparent castaway and get far more than they expected. Williams gives unremitting apprehension by crosscutting the two situations while also filling in the backstory in ways that add layers of understanding and misunderstanding. It’s a model blend of mystery and suspense.

It’s also a lesson in another, frequently forgotten side of the hardboiled tradition. The tough guy isn’t just a mindless thug; he’s often the master of a delicate craft. Stark’s Parker is a virtuoso in breaking and entering, but also in calmly managing the problems that come up. He works with his hands but also his mind. So does the central male of Dead Calm. John Ingram must draw on his expertise in professional sailing to stay alive in a crisis, and Williams freely lets us understand the minutiae of survival to make us admire his resourcefulness. More significant, Ingram’s wife has absorbed many of the same skills, and her shrewd use of them renders her as no less tough an adversary.

Williams’ rich vocabulary yields the pleasure of watching neat, efficient intelligence in a crisis. Another sort of literary gravity, then, makes this book as evocative as any piece of straight fiction, and more gripping than most. No wonder that Philip Noyce and Terry Hayes were able to adapt it to the screen in 1989 with trim economy.

Ladies of crime

Women writers have been prominent in crime fiction virtually from the start. Anna Katherine Green’s bestselling detective story The Leavenworth Case (1878) predates Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series. Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Marjorie Allingham and others became famous for their mystery novels. In the 1930s and 1940s, Charlotte Armstrong, Elizabeth Sanxay Holding, Vera Caspary, and many others contributed both whodunits and psychological thrillers. Sarah Weinman has collected some of these authors’ outstanding suspense novels in a fine Library of America set, which I discuss in another entry.

Among these admirable artisans was Dorothy B. Hughes, whose Ride the Pink Horse (1946) and In a Lonely Place (1947) were adapted to films that became prime examples of what was later called film noir. Hughes also wrote a discerning critical biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. She reflected thoughtfully on the conventions of crime fiction, reviewing books and even teaching a course at UCLA in the 1960s.

Among these admirable artisans was Dorothy B. Hughes, whose Ride the Pink Horse (1946) and In a Lonely Place (1947) were adapted to films that became prime examples of what was later called film noir. Hughes also wrote a discerning critical biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. She reflected thoughtfully on the conventions of crime fiction, reviewing books and even teaching a course at UCLA in the 1960s.

Perhaps her acute awareness of how thrillers manipulate viewpoint to maximize anxiety and to build up mystery led her to The Expendable Man (1963). It’s a wrong-man plot. Out of a spurt of kindness Dr. Hugh Densmore picks up a hitchhiking teenage girl on a lonely desert highway. She turns out to be reckless, manipulative, and obviously dangerous. Densmore lets her out at several points on the way, only to find her waiting for him further along. In Phoenix, where he’s come for his niece’s wedding, the young doctor learns that the girl has been murdered. He’s a prime suspect.

During his first police interrogation, Hughes casually drops in a shock that makes the reader reevaluate everything that’s led up to it–and feel not a little shame in the bargain. After this tour de force, Densmore’s struggle to prove himself innocent takes on a new pressure that adds enormously to the growing tension. Sorry to be so cryptic, but you have to read it in innocence to feel the diabolical force of Hughes’s scheme.

Margaret Millar, Santa Barbara. From “Margaret Millar Rediscovered,” Bay Area Reporter.

The Expendable Man locks us tightly to Densmore’s consciousness, while another book by a queen of suspense uses a wider-ranging narration. In Margaret Millar’s The Fiend (1964), a moving-spotlight narration reveals sharp criticism of how wives chafe under suburban routine.

Charlie Gowen spends his lunch hour sitting in his green coupé watching children in a playground. He becomes worried that one little girl takes risks on the jungle gym, and he fears that her parents are neglecting her. This concern grows to the point that he sends an anonymous letter to her mother. But he sends it to the wrong family. From this festers a plot of intricate lies, revelations, misunderstandings, and accusations that pulls in an entire neighborhood–friends, other kids, librarians, a lawyer, a pharmacist, Charlie’s caretaker brother, a would-be romantic partner, and of course the police.

Millar was a major crime novelist recognized in her day but now little-known. (Her fame was eventually surpassed by that of her husband Kenneth Millar, aka Ross Macdonald. I think she’s the better writer.) Her many first-rate suspense novels include A Demon in My View (1955) and Do Evil in Return (1950), a sensitive probing of a female doctor deciding whether to perform an illegal abortion. The Fiend sustains suspense to the very last page while offering portraits of children’s efforts to understand adult hypocrisy, and the various ways women cope with suffocating domesticity–not least, the obliteration of their identities. All this is given in a rich evocation of the milieu, down to the redwood picnic tables at a backyard barbecue and chipmunks scampering up lemon trees.

Unlike Millar, Patricia Highsmith was often underrated by American genre fans, while highbrow critics mostly ignored her. Fame has come to her more recently, thanks largely to popular film adaptations of her books (especially The Talented Mr. Ripley, 1999) and her tumultuous life as a Lesbian. Her personality, alternately fascinating and repelling, has too often distracted commentators from the power of her plotting and style. I try in Perplexing Plots to provide an analysis of some of her major storytelling strategies.

Her other books do not fully prepare you for The Tremor of Forgery (1969). It’s a crime novel in which the crime has the haziness of a mirage. Howard Ingham is in Tunisia starting to prepare a screenplay when his progress halts after the death of his producer in New York. He decides to linger and work on his next novel. That centers on an amoral, Ripleyesque bank executive stealing funds from accounts. In the real world, Ingham loiters, tours Tunisia, and strikes up friendships with a gay neighbor and a peculiar American propagandist. He also broods on whether his producer was having an affair with Ina, a woman he might marry. All this takes place against the background of the six-day Arab-Israeli war and the ongoing war in Vietnam.

Eighty pages in, Ingham takes a hasty action that may have resulted in a man’s death. By utterly limiting the viewpoint to Ingham, Highsmith keeps us in uncertainty about the consequences. The rest of the book plumbs Ingham’s mind as he tries to discover what he may have done and reacts to the responses of those around him. Highsmith’s finesse in keeping us in suspense about the exact contours of the incident releases her from what Henry James called “weak specification.” Instead she puts at the center of our attention Ingham’s fluctuating uncertainties about what he has done and should do.

The title refers to the telltale tremor in the sort of forgeries that Ingham’s embezzler Dennison commits. If it’s a symptom of guilt, it’s also a trace of Highsmith’s perennial theme of the instability of a person’s identity. Sometimes Ingham feels that he’s no more than all the opinions about him others hold. The Tremor of Forgery asks to what extent all our momentary roles are forgeries, and whether our moments of guilt and indecision betray a fundamental emptiness. At one moment, Ingham considers the possibility that “One was nothing anywhere, ever.”

As usual for the Library of America, these nine powerhouses are presented in elegant editions, filled out with plenty of authorial background and bibliographical sources. Just as important, this publishing initiative does a lot to dissolve that boundary between art and entertainment I objected to in an earlier entry.

Dead Calm (1989).

Art, entertainment, and the hard-boiled mystique

The Maltese Falcon (1941).

DB here:

The traditional opposition between Art and Entertainment still holds some sway. Art, some believe, is the realm of higher significance and profound emotion, while entertainment yields mere diversion and superficial engagement. Art embodies wisdom and technical breakthroughs, while at best entertainment is home to talent and cleverness. Art harbors genius, entertainment offers ingenuity. Art expresses the creator’s personal vision, entertainment recycles collective fantasy (or the Zeitgeist). There’s usually an implied hierarchy of quality and of appeal: art is for a sensitive elite, entertainment is popular (read vulgar).

One problem, though, is that for long stretches of history much art has been thoroughly entertaining. Mozart, Shakespeare, Dickens, Hiroshige, Austen, and many other major artists have found wide popularity. They provide pleasure aplenty. But with urbanization and the rise of capitalism, mass production created a huge public, and tastemakers have tended to treat art as a realm apart. For a hundred years or more, entertainment has been equated with mass culture, and art with high culture, most notably with modernism and its successors.

Another problem is cultural endurance. In a recent column, Michael Dirda points out that genre fiction often outlasts prestigious literary fiction of its era.

Take fantasy and science fiction: In 1997, I praised William Gibson’s “Neuromancer,” John Crowley’s “Little, Big,” Gene Wolfe’s “Book of the New Sun” and the works of Ursula K. Le Guin — all remain vital to contemporary writers and readers.

Similarly, classics of mystery fiction by Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Patricia Highsmith still attract readers, while “mainstream” novels of their eras are forgotten. Dirda’s second point is no less valid.

More generally, American novelists have wholly embraced the energy and potential of fantasy in its various forms. We are all fabulists now. This century revels in comics, graphic novels, manga and superhero movies. Authors as varied as Colson Whitehead, Walter Mosley, Kelly Link, Jonathan Lethem, Elizabeth Hand and Michael Chabon, to name a few prominent figures, all grew up loving fantasy and science fiction.

Genre appeals have infiltrated prestige literature, as in the crime plots of Graham Greene, Joyce Carol Oates, and Richard Price. (I consider Colson Whitehead’s and Richard Wright’s contributions here.) Likewise, we have horror-infused tales like George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo and Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home .

Creators of entertainment have felt the distinction keenly. “A wedge has been driven into the industry,” says Christopher MacQuarrie, director of the latest Mission: Impossible installment. “Are you an artist or an entertainer? Tom doesn’t see them as mutually exclusive.” But some creators have seen a forking path. Rex Stout, after several “serious” novels failed, came to two conclusions:

First—that I was a good storyteller, and second—that I would never be a great novelist. I’d never be a Tolstoy, or a Dickens, or a Balzac…. So since that wasn’t going to happen, to hell with sweating out another twenty novels when I’d have a lot of fun telling stories which I could do well and make some money on it.

The Art/ Entertainment distinction runs through my recent book, Perplexing Plots, because many mystery writers have aimed at “elevating” their work to the level of prestige literature. This urge drives them to experiment with the norms of plotting and writing. Even when the genre limits remain in force, there’s a chance that skillful exponents can accept them and still yield “literary” pleasures. A good example is what happened to hard-boiled detective fiction in the hands of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler.

The Op

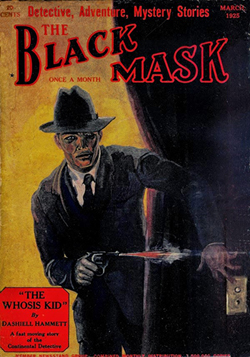

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Hammett launched his fame with a series of crime stories mostly published in the pulp magazine Black Mask from 1923 to 1930. His protagonist is a nameless investigator for the Continental Detective Agency. The Continental Op, as he came to be called, is a pudgy but tough middle-aged detective who values camaraderie, crafty stratagems, and a good cheap steak. Women flirt with him, but he sees through their schemes. The Op’s drabness and humility give him a realism that is amplified by the milieu Hammett depicts. He had been a Pinkerton agent and larded the stories with underworld argot and tips on investigative technique.

Black Mask stories put a premium on action, so the Op was often at the center of violence perpetrated by crooks, sociopaths, and corrupt cops. Unlike other hard-boiled detectives, the Op isn’t a swaggering sadist. Violence is his last resort; he favors obstinate everyday professionalism. Sometimes he’s fooled by the grifters and has to wriggle his way out. At other times, he can set crooks against one another and watch the mutual destruction.

Hammett wrote the stories in the first person, giving the Op a telegraphic, visceral style laced with sour humor. A 1923 story shows his American vernacular already in place.

Just at the wrong minute Henderson decided to look over his shoulder at us–an unevenness in the road twisted his wheels–his machine swayed–skidded–went over on its side. Almost immediately, from the heart of the tangle, came a flash and a bullet moaned past my ear. Another. And then, while I was still hunting for something to shoot at in the pile of junk we were drawing down upon, McClump’s ancient and battered revolver roared in my other ear.

Henderson was dead when we got to him–McClump’s bullet had taken him over one eye.

McClump spoke to me over the body.

“I ain’t an inquisitive sort of fellow, but I hope you don’t mind telling me why I shot this lad.” (“Arson Plus”)

In 1929, the publisher Knopf issued two Hammett novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse, based on Black Mask serials. The Op had not lost his wit or his gift for staccato narration. Here are three excerpts.

I didn’t think he was funny, though he may have been.

He stood at the foot of the bed and looked at me with solemn eyes. I sat on the bed and looked at him with whatever kind of eyes I had at the time. We did this for nearly three minutes.

The latch clicked. I plunged in with the door.

Across the street a dozen guns emptied themselves. Glass shot from door and windows tinkled around us.

Somebody tripped me. Fear gave me three brains and half a dozen eyes. I was in a tough spot. Noonan had slipped me a pretty dose. These birds couldn’t help thinking I was playing his game.

I tumbled down, twisting around to face the door. My gun was in my hand by the time I hit the floor.

Across the street, burly Nick had stepped out of a doorway to pump slugs at us with both hands. I steadied my gun-arm on the floor. Nick’s body showed over the front sight. I squeezed the gun. Nick stopped shooting. He crossed his guns on his chest and went down in a pile on the sidewalk.

Hands on my ankles dragged me back. The floor scraped pieces off my chin. The door slammed shut. Some comedian said:

“Uh-huh, people don’t like you.”

As he was finishing The Dain Curse, Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf confessing that in future work he wanted to go beyond Entertainment to Art.

I’m one of the few—if there are any more—people moderately literate who take the detective story seriously. I don’t mean that I necessarily take my own or anybody else’s seriously—but the detective story as a form. Some day somebody’s going to make “literature” of it (Ford’s Good Soldier wouldn’t have needed much altering to have been a detective story), and I’m selfish enough to have my hopes, however slight the evident justification may be.

The question is: How to do this?

Inside and outside

Hammett proposed an answer in his letter to Blanche Knopf. He wanted to try that he wanted to try out modernist technique in a third novel.

I want to try adapting the stream-of-consciousness method, conveniently modified, to the detective story, carrying the reader along with the detective, showing him everything as it is found, giving him the detective’s conclusions as they are reached, letting the solution break on both of them together. I don’t know whether I’ve made that very clear, but it’s something altogether different from the method employed in “Poisonville [Red Harvest],” for instance, where, though the reader goes along with the detective, he seldom sees deeper into the detective’s mind than dialogue and action let him.

His mention of stream of consciousness may mislead us about his intentions. In that technique the verbal narration seeks to mimic the flow of the mind as it flits across sensory impressions, memories, and fantasies. The process is often rendered as sentence fragments, often introduced by a sentence indicating the behavior of the character.

Here’s an example from Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), the most famous showcase of stream of consciousness. Mr. Bloom is in a Catholic church.

He saw the priest stow the communion cup away, well in, and kneel an instant before it, showing a large grey bootsole from under the lace affair he had on. Suppose he lost the pin of his. He wouldn’t know what to do to. Bald spot behind. Letters on his back I.N.R.I? No: I.H.S. Molly told me one time I asked her. I have sinned: or no: I have suffered, it is. And the other one? Iron nails ran in.

Sometimes the images and phrases are separated by commas and periods, but sometimes they simply pile up. In the book’s last chapter, Molly Bloom’s drowsy imaginings are given in an unpunctuated, sparsely paragraphed flow.

It’s likely that Hammett didn’t want his usage to be as fragmentary as what we encounter in Joyce and others. His invocation of Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915) suggests something closer to what many now call inner monologue. (Ford called it “impressionism.”) Here the flow of thought is given as a sort of soliloquy, a flow of more or less cogent and coherent ideas and impressions. What makes it a modernist technique is that inner monologue may not respect story chronology and it’s likely to be biased, uncertain, equivocal, and subject to revision. Ford’s narrator, John Dowell, tells a rambling, out-of-order tale of marital infidelity and suicide, in which flashbacks are analyzed and re-analyzed.

Looking over what I have written, I see that I have unintentionally misled you when I said that Florence was never out of my sight. Yet that was the impression that I really had until just now. When I come to think of it she was out of my sight most of the time.

At the climax, Dowell makes a provisional sense of what the characters knew and why they acted as they did.

The problem in importing this to the detective story is evident. How can the detective’s ongoing reasoning, bristling with mistaken inferences and reconstructed impressions, be passed along to the reader without causing confusion? For this reason, detective story narration, whether first-person or third-person, suppresses most of the protagonist’s reasoning. The Watson figure and the dumb authorities exist to be baffled and play with misleading possibilities while the detective holds back even a partial solution.

By convention, the climax of the tale is the revelation of the truth–not when the detective discerns it, but at the moment when it can be announced with decisive impact (often in a gathering of suspects with the police present). Raymond Chandler noted that the delayed revelation was a serious constraint of the genre, even when the detective, like the Op, is telling the story. “The first person story is assumed to tell all but it doesn’t. There is always a point at which the hero stops taking the reader into his confidence.” The detective “stops thinking out loud and ever so gently closes the door of his mind in the reader’s face.” This prevents the public announcement of the solution from being anticlimactic.

Worse, Ford’s protagonist Dowell is an unreliable narrator, as the above passage suggests. To make the detective’s first-person account unreliable would be more than a “convenient modification” of the standard plot schema. It would push toward the experiments seen in Cameron McCabe’s The Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937) and later “anti-mysteries.”

Hammett admitted in a later letter that he would put the “stream-of-consciousness” experiment on hold while he wrote material for Hollywood in “more objective and filmable forms.” (That would include his script for City Streets of 1931, which does include a subjective auditory flashback rare in films of the time.) But in his next novels Hammett turned sharply away from the interiority he had considered. Instead, he went toward extreme objectivity, almost completely shutting us out from his protagonists’ inner lives.

The action of The Maltese Falcon (1930) and The Glass Key (1930) attach us closely to his protagonist, scene by scene. We’re confined to his activity and his range of knowledge. But this doesn’t get us into his mind. For these books Hammett switched to third-person narration and made it radically objective, sticking almost completely to reporting dialogue and character interaction.

In Perplexing Plots, I explore how this strategy works, but here’s an example from The Glass Key.

At Madison Avenue a green taxicab, turning against the light, ran full tilt into Ned Beaumont’s maroon one, driving it over against a car that was parked by the curb, hurling him into a corner in a shower of broken glass.

He pulled himself upright and climbed out into the gathering crowd. He was not hurt, he said. He answered a policeman’s question. He found the hat that did not quite fit him and put it on his head. He had his bags transferred to another taxicab, gave the hotel’s name to the second driver, and huddled back in a corner, white-faced and shivering, while the ride lasted.

The narration presents what a third-person observer would have seen and heard, and it won’t venture into Beaumont’s thinking. The cues are behavioral: he seems cool enough in slipping out of the crash, but his true reaction is given through his nervous reaction while riding back to the hotel.

As Hammett’s second letter to Blanche Knopf suggests, this flat objectivity would seem an ideal novelistic basis for a “filmable” treatment. John Huston’s screen adaptation of The Maltese Falcon confines us almost completely to Spade’s range of knowledge. (The big exception is that we see his partner Miles Archer shot by an unknown killer.) The film’s visual narration mostly follows Hammett’s impassive neutrality. But when Casper Gutman drugs Spade, we get Spade’s clouded optical viewpoint.

In the novel the narration reports that Spade’s eyes seemed to muddy over. When he says, “And the maximum?” we’re told that “An unmistakable sh followed the x in maximum as he said it.” This isn’t Spade’s experience but rather what an observer would register, an “unmistakable” impression confirmed when we’re told that “a sharp frightened gleam awoke in his eyes.” As Spade tries to walk, he’s tripped by Wilmer. He falls and Wilmer kicks him. “Once more he tried to get up, could not, and went to sleep.” The whole scene is rendered externally.

So instead of giving the detective story a modernist subjectivity, Hammett went to the other extreme. Did he intuitively recognize the problem of revealing the detective’s inferences too soon? Maybe, although his increasing involvement with Hollywood may have kept him on the objective, “filmable” path. The Thin Man (1934), his last novel, is a fascinating effort to return to first-person narration while incorporating the dry objectivity of the two previous books.

Perhaps inadvertently, Hammett’s radicalization of the objective method yielded what he had hoped for. The Maltese Falcon was greeted as a serious work of literature and was soon incorporated into the prestigious Modern Library series. His works have become part of the canon of American letters enshrined in the Library of America collection. The convention of delaying the detective’s solution didn’t prevent the genre from becoming accepted as a legitimate literary form–at least as practiced by Hammett, and his most prominent successor.

Overtones, echoes, images

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

That successor was, of course, Raymond Chandler. Ten years after Hammett wrote to Blanche Knopf with his hopes of elevating the whodunit, Chandler wrote to Alfred Knopf about his plans for The Big Sleep (1939) and the novels that followed. It has an echo of Hammett: “I was more intrigued by a situation where the mystery is solved by the exposition and understanding of a single character, always well in evidence, rather than by the slow and sometimes long-winded concatenation of circumstances.”

But what Chandler means by “understanding” doesn’t include full-blown reasoning. First-person narration, he explains in a 1949 note, must “suppress the detective’s ratiocination while giving a clear account of his words and acts and many of his emotional reactions.” This seems a response to the detached reportage of late Hammett prose. Chandler also rejects the Op’s streetwise patter by explaining to Knopf that his method will use “a very vivid and pungent style, but not slangy or overtly vernacular.” He wants “to acquire delicacy without losing power.”

Hammett, while a voracious reader, learned a good deal of his craft from actually investigating crimes. Chandler, who began writing mysteries as Hammett’s productivity tailed off, owed his knowledge of the mystery genre to reading. He studied crime fiction of all sorts with almost academic passion and became one of the most nuanced commentators on the tradition. He claimed to have learned plotting from outlining pulp stories by Erle Stanley Gardner. His literary tastes didn’t run to modernism. He admired the Greek and Roman classics, Flaubert, James, and Conrad and thought highly of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Hammett imagined elevating the genre by “conveniently modifying” modernist technique, but Chandler sought to make the hard-boiled detective story more like the ambitious mainstream novel.

He believed he could do that through style. In his crucial essay, “The Simple Art of Murder (1944/1946),” he praises Hammett’s prose but objects that “it had no overtones, left no echo, evoked no image beyond a distant hill.” Chandler sought to give style a greater novelistic richness not only through probing his protagonist’s mind but also through fairly dense descriptions colored by the protagonist’s emotions and judgments.

Hammett sketches characters in quick strokes and he merely indicates settings. But Chandler dwells on his characters and their surroundings. The opening of The Big Sleep devotes a page and a half to Philip Marlowe’s impressions of the Sternwood mansion (stained-glass window of a knight rescuing a lady, plush chairs, a mysterious portrait) and another page and a half to his meeting with the coy Carmen. These are filtered through Marlowe’s running commentary. The knight doesn’t really seem to be trying. The chairs appear to never have been sat in. The portrait looks threatening. Carmen’s infantile flirtation reveals that “thinking was always going to be a bother to her.” Here are the overtones and echoes that Chandler finds lacking in Hammett. This is an ominous household–as Marlowe will later say, this will be “no game for knights.”

Chandler would pursue this method in the following novels. Yet at times the narration plunged deeper into subjectivity. In Farewell, My Lovely (1940) Marlowe is repeatedly knocked out in tussles, and in the second passage Chandler writes:

The man in the back seat made a sudden flashing movement that I sensed rather than saw. A pool of darkness opened at my feet and was far, far deeper than the blackest night.

I dived into it. It had no bottom.

The film adaptation, titled Murder, My Sweet (1944), uses this subjective device in every knockdown. Marlowe’s voice-over narration runs through the film, and after the first assault we hear:

I caught the blackjack right behind my ear. A black pool opened up at my feet. I dived in. It had no bottom.

Onscreen we see Marlowe’s crumpled body blotted out by a miasma that leads to a black frame.

In a later sequence, a knockout of Marlowe is rendered as wild optical exaggerations before following the novel’s report of Marlowe seeing a room full of smoke. That’s translated as wispy superimpositions over the shots, with explanatory voice-over.

The film tries a bit too hard, but its use of voice-over and delirious visual subjectivity would become common in film noirs of the period.

In Farewell, My Lovely, Marlowe’s recovery from his first knockout is rendered with vigorous subjectivity across two pages, as Marlowe realizes that the voice he hears reviewing what happened is his own. “I was talking to myself, coming out of it. I was trying to figure the thing out subconsciously.”

Marlowe is able to reconstruct bits of the crime through this process, but it’s a provisional solution, not the decisive one. That one he keeps from the reader until the climax. By then, as per convention, the door to his mind has shut in the reader’s face.

Hammett’s novels were published when most crime fiction consisted of genteel whodunits and gangster sagas, so he had the advantage of novelty. By the time Chandler published The Big Sleep, he was competing with many book-length stories of hard-boiled investigators. Aware of the need to establish a distinctive presence, he presented work that stood apart by its social criticism and the romanticized realism of a righteous avenger alone on the mean streets of a corrupt city–sure-fire attractions to intellectuals then and since. Just as important was his self-consciously literary style. “In the long run, however little you talk or even think about it, the most durable thing in writing is style, and style is the most valuable investment a writer can make with his time.”

Through concern with language’s echoes and overtones, he established himself as Hammett’s successor. The literati followed his lead and declared him a significant novelist. His books, along with “The Simple Art of Murder,” provided an enduring rationale for the tough detective story. While adhering to the conventions of the classic puzzle (clues, faked deaths, false identities, least-likely culprit), he acquired lasting prominence. Like Hammett he has found a home in the Library of America.

Arguably Hammett and Chandler also elevated their genre. Their achievements encouraged other ambitious writers and stimulated critics and readers to look more closely at the possibilities of the murder novel. No wonder that prestigious writers have turned to mystery plots. Fans still labor to make a case for Golden Age puzzles as art rather than entertainment, but most critics and readers assume the hard-boiled mystery to be at least potentially serious literature–especially when it goes under the alias “noir.”

Nowadays the Art/ Entertainment duality has weakened its hold. If, as Dirda suggests, we are all fabulists now, we’re also probably mystery fans to some degree. It’s likely that film played a role in dissolving the duality. Intellectuals began to understand that films by Ozu, Hitchcock, and other popular directors were of high quality. More and more, I think, people aren’t as eager to see the split as absolute. Instead of a hierarchy, we have more of a spectrum.

In harmony with this, Perplexing Plots argues that culture offers us a plenitude of individual works with varied appeals, all of which can be realized with, to use Chandler’s terms, delicacy and power. Some works rely on subtlety, others on immediate impact. We have the refinements of Baroque music and the direct force of The Rite of Spring. If Treasure Island is a masterpiece as well as a rousing yarn, so is Die Hard. There is heavy art and light art, brooding art and and diverting art, intellectual density and emotional charm. None of these qualities is simple or easy to achieve; all can repay analysis. The slogan might be: “There’s valuable work at all levels. And there are no levels.”

One source of value, not always acknowledged, is the role of entertainment in revealing fresh expressive possibilities in the medium. For example, the martial arts cinemas of Japan and Hong Kong opened up new vistas of cinema. And yes, as Hammett and Chandler indicated, a lot of the freshness lies in style. This is why Perplexing Plots spends time looking closely at how mystery fiction and film work, word by word or shot by shot. Even Agatha Christie’s supposedly bland verbal texture points up ways in which language can mislead us.

So Hammett and Chandler didn’t “elevate” the hard-boiled story so much as blur the line between genre fiction and the “legitimate” novel. Ambler and Le Carré did the same for the spy story, as did Highsmith for the psychological thriller. For such reasons, Perplexing Plots discusses hard-boiled detection extensively. I explore the Art/ Entertainment distinction because it has obsessed critics and creators. But I try not to buy into the split, opting instead for the looser idea of “crossover.” It’s a swap meet, with storytellers ransacking works “high” and “low” for subjects, forms, techniques, whatever.

I wanted to put up this entry on 23 July, Raymond Chandler’s birthday. It happens to be mine too. No cheerleading here, though. I prefer Hammett, as maybe you can tell.

My quotations from Hammett’s letters come from Selected Letters of Dashiell Hammett, 1921-1960, ed. Richard Layman and Julie Rivett (2002). I take Chandler’s remarks on mystery fiction from Selected Letters of Raymond Chandler, ed. Frank MacShane (1981) and Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardiner and Katherine Sorley Walker (1962).

Michael Dirda, as my mentions of him should lead you to expect, has written an admirable example of taking popular storytelling seriously but not solemnly: On Conan Doyle, or the Whole Art of Storytelling (2014). Kristin does something similar in her Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes, or Le Mot Juste (1992), available here and here. Her immensely popular subject, P. G. Wodehouse, was regarded as a master of English prose by Martin Amis, Evelyn Waugh, and many other literary celebrities.

What about the third celebrated hard-boiled pioneer, Ross Macdonald? Read Perplexing Plots to find out!

Murder My Sweet (1944).

P.S. 11 October 2023: In a Slate essay, Dan Sinykin shows that the merging of “genre fiction” and “literary fiction” has causes in the economics of the publishing industry. A fine analysis I wish I’d had available for Perplexing Plots.

The reader is warned

Where the Crawdads Sing (2022; production still).

DB here:

When I wasn’t paying attention, along came Where the Crawdads Sing (2018 novel, 2022 film). The book was a huge bestseller, while the movie version was panned by critics but attracted a good-sized audience. It exemplifies how strategies of nonlinear storytelling have become deeply woven into mainstream entertainment.

It has an investigation plot, structured around the trial of “swamp girl” Kya, who’s accused of the murder of her boyfriend Chase in the marshlands of North Carolina. Through flashbacks we learn of her desperate childhood, as she is abandoned by her family and castigated by the townfolk. She learns to live alone in the family cabin and fills her days drawing precise images of the natural life around her. A well-meaning young man teaches her to read but he too he leaves her to struggle alone. Soon she meets Chase, a charming good-for-nothing. Is his fall from a swamp tower an accident, or did someone push him? A kindly local attorney takes her case, and the plot climaxes first in the jury’s verdict and then a twist that reveals what happened at the scene of the crime.

We’re so used to plots like this that we may forget how nonlinear they are. In the Crawdads film, the court investigation probes the circumstances of Chase’s death, but the flashbacks, instead of illustrating stages of the crime, supply Kya’s life story in chronological order. They contextualize the long-range causes of her dilemma. Accordingly, they’re narrated by her in voice-over. Titles supply the relevant timeline, dating episodes from 1963 through to 1970, the year of the trial.

All of these strategies have become familiar from a century of popular storytelling. A court case as an occasion to visit the past goes back at least to Elmer Rice’s On Trial (1914), although the play dramatizes testimony in a way that Crawdads doesn’t. (Its flashbacks, more boldly, are in reverse order.) The crosscutting of past and present has become common to explain (or obfuscate) ongoing story events. Tying us to a character’s viewpoint and letting the character’s voice narrate what we see is likewise a standard device in modern media. And of course an investigation plot is inherently nonlinear. The task is for someone to uncover the “hidden story” of what occurred in the past.

Simple though it is, Where the Crawdads Sing shows just how pervasive devices associated with mystery and detective fiction have become in mainstream storytelling. Told chronologically, the story would be a biography of Kya (and would presumably have to reveal how Chase died). Instead, the film becomes what Wikipedia calls “a coming-of-age murder mystery.”

By splitting the chronological story into two parts and interweaving them, manipulating viewpoint, and rearranging temporal order, the film tries to achieve interest and suspense. We know from the start that Chase is dead, so we watch every scene with him for clues as to what could have caused it. Tension gets amplified as time passes, when the shifts between the courtroom drama and the day of Chase’s death come faster and faster. These effects couldn’t be achieved with a linear layout.

One of the major points of Perplexing Plots is to remind us just how much of popular entertainment trades on narrative strategies forged in the big genre of mystery. Once we’re reminded, we can ask: How did those strategies get implemented? How did audiences come to understand and enjoy these highly artificial ways of telling stories?

I promise not to keep plugging the book on this blog, but allow me one more notice. A Q and A with me has been published on the Columbia University Press site. It tries to inform any souls whom fate has cast my way about the argument of the book. You may find it of interest.

I’m taking the occasion to note some features of the book not advertised elsewhere. Perhaps they too would appeal to you, especially if you’re interested in some of the choices a writer has to make.

Obscure is as obscure does

First, the book draws on some unorthodox sources. Most obviously, I tried to canvass obscure novels and plays that are now forgotten but that did try some experiments with nonlinear storytelling. Who’d expect a reverse-chronology play in 1921, years before Pinter’s Betrayal (1978)? A 1919 play anticipates Rear Window by offering testimony from a deaf witness and then a blind one. The first version plays out on stage in pantomime, the second in a completely dark setting. A 1936 novel offers a string of conflicting character viewpoints on a single situation, revising and correcting previous accounts, well in advance of Herman Diaz’s recent novel Trust. A 1919 play depicts a woman in different aspects, as seen by the people who know her. These instances of what we now call “complex narrative” belong to what literary scholars have called “the great unread,” the thousands of pieces of fiction and drama that haven’t become canonical through enduring popularity or academic favor.

Other precedents are dimly recalled but seldom revisited, such as George M. Cohan’s play Seven Keys to Baldpate (1913) and W. R. Burnett’s Goodbye to the Past (1934). How many people would be aware of Kaufman and Hart’s reverse-chronology play Merrily We Roll Along (1934) if Stephen Sondheim hadn’t turned it into a musical? The very existence of these marginal works helps support the premise that a lot of what we consider innovative today has broad historical roots. They just aren’t as vivid to our memory as more recent instances. But fifty years from now, will many viewers remember contemporary experiments like Go (1999) and Shimmer Lake (2017)?

The book uses other unorthodox sources. I put craft technique at the center, and so it makes sense to look at the principles that writers of fiction and drama were using. Of necessity I review the emerging idea of the “art novel” at the end of the nineteenth century, with Henry James as spokesman for this trend. In addition, unlike most mainstream literary histories, Perplexing Plots consults contemporary manuals for aspiring writers. These books are the progenitors of all those how-to-get-published books that fill Amazon today, and they reveal a surprising sophistication. Manuals allow me to show how a new self-consciousness about linearity, particularly point of view, became central to popular writing as a craft. For example, a now-forgotten critic, Clayton Hamilton, epitomizes the willingness of ambitious writers to try out new possibilities.

So one choice I made was to search out fiction, drama, and films that have fallen into obscurity. Another was to look at the nuts and bolts of plotting, as practitioners seemed to be conceiving it. These help explain why many novels and plays, major and minor, began tinkering with innovative storytelling.

Time as space

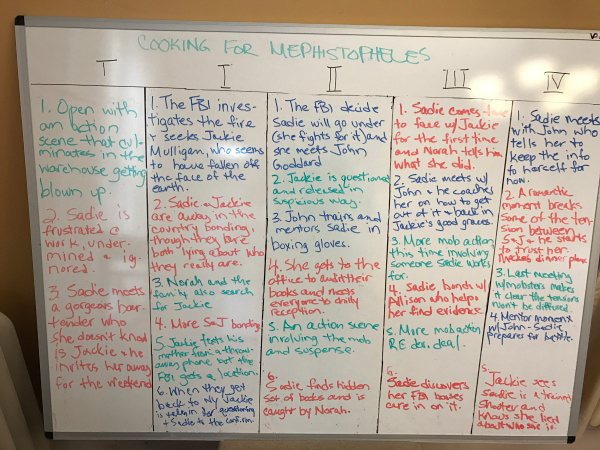

From Karen Loves TV: “Contemplations on the Whiteboard.”

A nonlinear plot has a geometrical feel to it, so one way of thinking about it is to envision it as a table or spreadsheet. Where the Crawdads Sing could be laid out in a double-column table, with each present-time scene aligned with the past sequence that follows it.

There are more complex possibilities as well. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) would constitute a four-column layout displaying each different historical epoch. Perhaps this is one sense of the term that came into use in the 1940s: “spatial form” as a description of unorthodox narratives. The principle is akin to the whiteboard “season arcs” and “episode outlines” used in writers’ rooms to lay out story lines threading through a film or TV series.

There are more complex possibilities as well. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) would constitute a four-column layout displaying each different historical epoch. Perhaps this is one sense of the term that came into use in the 1940s: “spatial form” as a description of unorthodox narratives. The principle is akin to the whiteboard “season arcs” and “episode outlines” used in writers’ rooms to lay out story lines threading through a film or TV series.

Novelists have long made use of such charts. The most famous is that prepared by James Joyce for Ulysses, where each chapter is assigned a different color, body organ, and so on. This was published in Stuart Gilbert’s 1930 book. Because the rights to reproduction are obscure, we regrettably didn’t include it my book. No surprise, though, it’s available online.

I did, however, obtain rights to a less-known but rather brilliant table included in Anthony Berkeley’s Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929). Later chapters of Perplexing Plots use tables of my own devising to clarify the complicated layout of Richard Stark’s Parker novels, the chapter structures of Tarantino films, and the alternating viewpoints and time schemes of Gone Girl. There will always be readers who complain that these tables are just academic filigree, but I believe that they help us appreciate the intricate interplay of time, segmentation, and viewpoint. They show how precise the narrative architecture of mystery fiction can be.

To spoil or not to spoil

For decades, criticism of mystery fiction has labored under the expectation that a critic must not reveal a story’s ending, or the story’s central deception. In journalistic reviews of literature and film, the writer is expected to keep such things secret, but even academic studies of crime fiction put pressure on the critic to maintain the surprise of whodunit and howdunit.

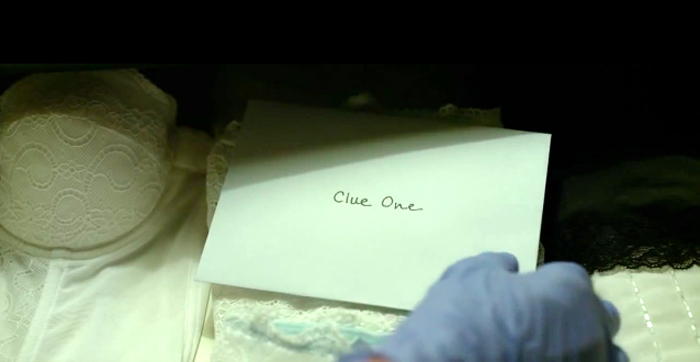

But this limits our ability to study plot mechanics. I chose to preserve the secrets of the books, plays, and films as much as I could (as with my Crawdads sketch). Still, when the analysis demanded exposure of the “hidden story,” I did so. This doesn’t result in a lot of spoilers because some canonical texts, like The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Big Sleep, are very well-known. But I lay out some strategies of deception in novels by Christie and Sayers and films such as Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. There really was no other way to show points of narrative craft at work in them, particularly the fine grain of writing or filming that shapes our response. I regret most exposing the central feint of Ira Levin’s novel A Kiss Before Dying, so readers who aren’t familiar with the book may want to read it before reading my account. Otherwise, I can only cite the title of one of Carter Dickson’s trickiest novels.

But this limits our ability to study plot mechanics. I chose to preserve the secrets of the books, plays, and films as much as I could (as with my Crawdads sketch). Still, when the analysis demanded exposure of the “hidden story,” I did so. This doesn’t result in a lot of spoilers because some canonical texts, like The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Big Sleep, are very well-known. But I lay out some strategies of deception in novels by Christie and Sayers and films such as Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. There really was no other way to show points of narrative craft at work in them, particularly the fine grain of writing or filming that shapes our response. I regret most exposing the central feint of Ira Levin’s novel A Kiss Before Dying, so readers who aren’t familiar with the book may want to read it before reading my account. Otherwise, I can only cite the title of one of Carter Dickson’s trickiest novels.

Part of the justification for hiding the legerdemain is the doctrine of “fair play.” I trace how this idea emerged in the Golden Age of detective fiction, when a story was treated as a game of wits between author and reader. In principle, nothing necessary to the solution of the puzzle should be withheld, though it can be disguised or hinted at. One thing I learned in writing the book is that fair play has become a premise of most duplicitous narratives in any genre, from horror to science fiction. People don’t realize how much the maneuvers of Psycho and Arrival owe to the belief that the audience should in principle be able to go back and see how we were misled. (We can do this with the “missing clue” in Crawdads as well.)

Fair play encourages the author to be ingenious and entices the audience to appreciate artifice-driven construction. Both effects are legacies of classic detective fiction, and they still shape much mainstream entertainment.

Thanks to Maritza Herrera-Diaz of Columbia University Press for arranging for the Q & A published on the Press site.

The phrase “the great unread” is used by Margaret Cohen in The Sentimental Education of the Novel (Princeton, 1999) and cited in Franco Moretti, “The Slaughterhouse of Literature,” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 61, 1 (March 2000), 208.

As I’ve indicated in an earlier entry, Martin Edwards’ The Life of Crime is a vast and entertaining survey of the history of mystery fiction. It was crucial help to me in writing Perplexing Plots. Martin, an advance reader of the manuscript, has been kind enough to discuss my book on his blog.

Other early responses to the book have been encouraging. Michael Casey reviewed it for The Boulder Weekly, and Doug Holm discussed it on KBOO on his show Film at 11. My thanks to both these commenters.

Psycho (1960): Misdirection and fair play all in one shot.

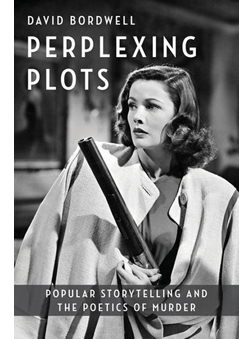

PERPLEXING PLOTS now available!

Gone Girl (2014).

DB here:

Like a movie rolling out on a platform release, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder, has several “publication dates.” The official pub date is 17 January of next year, and that’s when I expected to see it. Now Amazon lists a shipping date of 1 December. But I just got my author’s copies, and I learn that the book can be bought from Columbia University Press now–at a 20% discount! (As of this writing, Amazon offers no discount.) If you’re interested, go here. To get the discount, enter CUP20 in the promo code box.

As I indicated in an earlier entry, the book is an attempt to trace how mainstream audiences learned to understand and enjoy stories that play with linearity and viewpoint–what we now call the “New Narrative Complexity.” Except that it’s not so new. If we look at fiction, theatre, and film (even a little radio) from the nineteenth century to the present, and are willing to go beyond the canon in search of oddball experiments, we find that many of the subterfuges we associate with narrative innovation today were attempted earlier–sometimes achieving great popularity.

As I indicated in an earlier entry, the book is an attempt to trace how mainstream audiences learned to understand and enjoy stories that play with linearity and viewpoint–what we now call the “New Narrative Complexity.” Except that it’s not so new. If we look at fiction, theatre, and film (even a little radio) from the nineteenth century to the present, and are willing to go beyond the canon in search of oddball experiments, we find that many of the subterfuges we associate with narrative innovation today were attempted earlier–sometimes achieving great popularity.

I go on to argue that an important training ground for narrative gamesmanship was the realm of mystery, especially detective stories and suspense thrillers. I trace important developments in this domain and then analyze several of my favorite mystery-mongers, from Rex Stout and Donald Westlake to Patricia Highsmith and Laura Lippman. Yes, Griffith, Hitchcock, Tarantino, and other filmmakers are involved too.

I hope to devote some future blogs to filling out gaps in the book, such as discussing G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown stories, considering Nero Wolfe’s relation to the FBI, and examining a now-nearly-forgotten mystery series that in its day sold millions of copies. And, given how Knives Out chimes with PP, I expect to have something to say about Glass Onion. In the meantime, you can check the Table of Contents and read early reactions from readers on the CUP website. Encouragingly, the book is now number 1 in Amazon’s list of new books on mysteries.

Thanks to the readers who have already expressed interest in the book!

The Great Piggy Bank Mystery (1946).