Archive for August 2012

How to watch an art movie, reel 1

Sueño y silencio (2012). Shot 1.

DB here:

We all know that Hollywood films and their counterparts elsewhere obey certain conventions of style and story. (I say conventions to put it neutrally. Some will call them formulas, some will call them clichés.) Against that tradition some critics and film lovers posit what’s been called “festival cinema” or “art cinema,” a tradition that favors individual expression and more unusual storytelling. But can we say that this tradition also has its conventions?

I think so. Let me take an example that you’ve probably not (yet) seen. Jaime Rosales’ Sueño y silencio premiered in the Directors Fortnight at Cannes this year, went into distribution in Spain recently, and will probably be making the festival rounds. I think it’s a good film, but my appraisal is beside my point today. I want to use the film as a sort of “tutor-text,” a handy way of talking about how such movies engage us in ways different from more mainstream films.

Paranorms

Central to my claim is that such films cultivate intrinsic norms, storytelling methods that are set up, almost like rules of a game, for the specific film. In a way, every film does this. I once wrote that “every film trains its spectator”–an idea that Jim Emerson put more pungently as “Any good movie–heck, even the occasional bad one–teaches you how to watch it.” Up to a point, we figure out the film’s characteristic stylistic and narrative strategies as it unrolls.

Of course most films’ intrinsic norms match what we can call extrinsic norms–those codified by the tradition. Hollywood films frequently simply follow the conventions of genre, structure, style, and theme that have flourished for a long time. What the art film does, I think, is what ambitious Hollywood films try to do: It tries to freshen up its intrinsic norms. But it does this according to broader principles of the art-film tradition. In other words, an individual device might seem strange, even unique to this or that movie, but the function it fulfills is familiar to us from our knowledge of the tradition’s conventions. We figure out the device because we assume it has a familiar function.

Take an example. How does the film indicate that certain images are flashbacks? Classical Hollywood films provided clear markers: Dissolves as transitions, wobbly music, voice-over remarks indicating that a character was recalling the past. But 1960s art films found other devices–slow-motion, shifts to black-and-white or a different palette, cuts to images that would have been out of place in a continuous scene. Viewers who understood the concept of flashback could infer that in this film, flashbacks were signaled through an unusual intrinsic norm. Fairly soon, of course, these devices were widely copied and became extrinsic norms, to the point that Hollywood films picked them up.

I’ve tried to make this entry a primer in art-cinema comprehension strategies. Many of this site’s readers have had a lot of practice in watching films like Sueño y silencio, so in a way what I say won’t come as a surprise. Yet many skilled viewers know the conventions only tacitly. Critics are well-versed in the tradition, but they typically talk only about the film at hand and don’t examine how it connects with more general principles of storytelling. Noting these guidelines, then, helps us understand criticism as well as movies; we can gauge critics’ reactions more exactly when we realize they’re responding to particular conventions.

Since Sueño y silencio has had such limited exposure, I’ll dwell only on the film’s first twenty minutes, its first reel. If you don’t want any spoilage at all, stop reading right now. But actually, my commentary tells you less about the film’s plot twists than the early reviews. I’m just trying to illuminate how such films work and, of course, entice you to see the film if it becomes available to you.

Fifteen shots

When we go to a movie we usually know a good deal about it. For now, though, let’s pretend you haven’t been privy to any information about what you’re going to see in Sueño y silencio. You just take it as it comes. But of course you’re exercising your eyes, ears, and mind all the while.

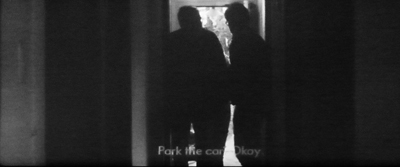

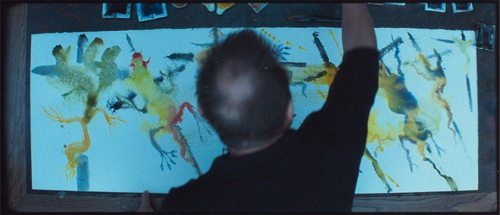

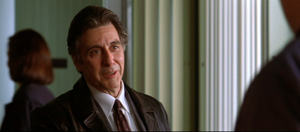

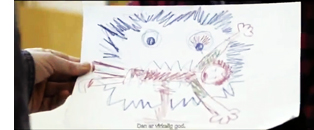

First you see a water-color painting being finished, in fast motion, by an unidentified painter (see the still at top). The image is pretty hard to determine. What seems to take shape is an image of a vaguely simian creature on the left, some animals in the middle, and a humanoid slung on what looks like a spit. What can this image have to do with what follows? Is the painter our protagonist, and will we learn about his creative endeavors? No. The shot functions as a kind of narrational mystery: We ask not only what it signifies, but why we’re being shown it.

This is as good a way as any of formulating an initial guideline for the hardcore art movie: How the story is presented is as important as what is presented. For instance, is this image offering a cluster of motifs that will be important in the film? When the film is over, we might be able to find out something about the painting or the painter, and we might find some connections to the plot.

So a second guideline: Often we’ll have to go outside the film to understand its story. This contrasts with most mainstream movies, which don’t make reference to recondite things like Spanish abstract painters. As it turns out, the painting refers to Abraham’s pious willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac to God, but it treats the tale in a disturbingly primal way.

Now the story proper seems to be starting. We watch a woman putting on eye make-up, seen through a slit in a door. There’s no dialogue, and the camera waits patiently; the shot lasts nearly a minute. This is the first signal that the film will be observing everyday routine, in more or less real time, from a stationary standpoint. The intrinsic norm that shapes nearly all the film–one fixed shot per scene–is being put into place. This stylistic choice isn’t unique to this film, but it is characteristic of art cinema. When there aren’t dramatic goings-on, as with Paranormal Activity‘s locked-down surveillance camera, the static shot usually asks us to adjust our expectations to a slowly unfolding exposition.

Why start with this woman (whom we’ll learn is called Yolanda)? I think it’s because, as the film goes on, she will be the focus of most of our attention, particularly once the drama starts. In a way, the film is following a very common extrinsic norm: Identify your protagonist early.

But the director gives with one hand and takes away with another. Yolanda isn’t doing anything of particular dramatic significance. At the same time, Rosales conjures up another, more unusual norm: obscured vision. We don’t see Yolanda fully and adequately. Throughout the film, our knowledge of what the characters do, even what they look like, will be cramped by such stylistic decisions. The film resists quick and easy comprehension; it asks us to make some effort. A new guidelines suggests itself: Be prepared to fill in a lot. And expect occasionally to be wrong.

A man (later identified as Oriol) and a little girl (Celia) are reading a storybook together. The tale is about monkeys in a park, and one escapes (in a book illustration they describe). Maybe this monkey connects back to the simian creature we saw in the painting? Later in the film, a zoo and a park will become very important.

But before we even get to these motifs, we notice that the filmmaker isn’t telling us who these characters are, or what their connection is to the woman we saw in the previous shot. We might assume that they’re a family, but a Hollywood film would tell us clearly and quickly (“Hi, Mom!” “Hi, honey. What are you and Dad reading?”). Here we have merely a possibility. A new guideline: A lot of exposition can be left to the imagination.

We’re also invited to consider the possibility that Oriol and Celia are especially close, since the other daughter we’ll meet, Alba, isn’t in this scene.

A long shot in a clothing store lingers for a while before Yolanda and two girls drift in from the right and wander to frame left. They are browsing for an outfit for Celia. Yolanda suggests a couple of choices, but Celia rejects them as uncool. Now we have better reason to take Yolanda as the mother of the family, but given that Oriol isn’t shopping along with them, there’s always the possibility that the parents are divorced or separated, swapping the kids back and forth. The basic circumstances of the family are held in suspension for some time.

The empty frame that opens this shot suggests another guideline. In many art films, settings take on a weight that they don’t have in many mainstream films. We’re used to them as a more or less neutral container for the real action, the clash of characters pursuing their goals. Films like Sueño y silencio may contain moments that function like the descriptive passages in a novel. These blocks of space invite us to focus on surroundings–to see them as abstract designs (planimetric framings like this work well), or to recognize their concrete layout, as here when Yolanda and her daughters have to thread their way through the aisles. Just as the unmoving long take asks us to feel the pressure of time, we should be ready to register space as space.

The next shot, of Oriol at his desk in his office, is doubly obscure: He’s in silhouette, and he’s talking to a man who is offscreen. This introduces another norm of the film: Often we won’t see both partners in a conversation. The framing will usually concentrate on the family members, as if the secondary characters are really secondary. But there are exceptions, and surprises as well.

The offscreen man is discussing his career, and from the conversation we learn that Oriol is an architect. But by starting with his role as father (reading to Celia), the film invites us to infer that the family may count more for him than his job does. (Imagine if the plot began by showing him at work, then showed him at home.) And just as he was patient and calm with Celia, he’s the same way with the young man offscreen.

In other words, first impressions matter in all films. They provide an anchoring bias that later developments will be measured against. In fact, an extended crisis later will propel Oriol into his work and away from his family. So while mainstream films tend to reinforce first impressions, many art films will nuance or even negate them. This can create an impression of character complexity, or of a narration that doesn’t pretend to know everything about the story.

Six and a half minutes in, the narration breaks one of its “rules.” A smoothly tracking camera takes us through a building under construction. For a few moments we’re allowed to register this as a specific place before the camera halts on a distant view of Oriol and some colleagues discussing the construction project.

In story terms, this could seem pretty redundant; we know Oriol is an architect. (Okay, now we know he’s a hands-on architect, but still…) But I think that the shot is important as resetting the film’s intrinsic norms. Later in the film, we’ll get small doses of camera movements of different types (one lateral track, one handheld shot, a couple of gliding Steadicam moves). It’s almost as if Rosales is sparingly spreading several alternatives out alongside his procession of static shots–a creative choice that will continue to dominate the film.

On the second viewing, it seemed to me that the payoff of this loft shot occurs when the camera moves away from the men and back toward the windows. Bursts of flash frames, as if the film were inadvertently exposed, end the sequence.

At the plot’s first turning point, we’ll get another moving shot, with the camera mounted on a car, and that will be broken up by a fusillade of flash frames like these. We’re used to foreshadowing in plot terms: the gun in the drawer in act one will get used at the climax. But we should expect that art films will use stylistic foreshadowing, often in place of the dramatic sort.

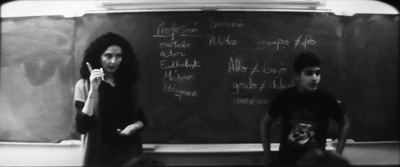

Now the exposition, oblique though it is, starts to hang together. Scenes of the family together (shots 2-4) are followed by a pair of shots showing Oriol at work (5 and 6). In another planimetric shot we see Yolanda at work, teaching Spanish to French students. But so far no conventional drama has started. Rosales has concentrated on showing the family’s daily lives and then lets us infer relationships and character from lots of ordinary activity. In shot 5, Oriol speaks as an idealist, saying that a building project’s budget ought not to determine the result. Here Yolanda is patient with her (unseen) students as she teaches them vocabulary through a guessing game.

For the Hollywood screenwriter, character is ultimately revealed through conflict. In many art films, character is revealed–or kept under wraps–through routines. This strategy puts an emphasis on what the person is like when not grappling with problems–on what we might call their enduring natures, or (as in Bresson) on their essential mystery.

More empty space: A girl’s bedroom, with photos and projects and lots of colored pencils and pens. Audrey Hepburn looks out at us. As in the clothing shop, setting comes forward. This time the locale encourages us to make inferences about character: later we’ll learn that Alba likes to draw and paint.

And more indirection. Offscreen conversation between the girls is followed by the two of them stepping partially into the frame. By now we can see that this film will deny us a lot. What will it give in return? Emotion–a domestic tragedy is going to strike–but muted emotion.

The girls play together, but it’s their gestures and voices (talking about a game they’ll play) rather than their faces that we have to fasten on. Art-cinema narration is a lot like what we find in a mystery film, but we’re teased with clues about basic story action. Instead of who done it? we ask what are they doing?

Now the scenic norm is firmly in place: We’ll be lucky to get half the scene: one character, or offscreen sound, or partial framings. In the ninth shot, all we see of Oriol is his arm. Still, maybe at last a drama is getting going. The boss complains that Oriol commits the firm to projects and then, once it’s on the hook, everybody has to fulfill his plans, regardless of the cost. Oriol replies that he’s flexible and willing to have the overages deducted from his pay. This leaves the boss flummoxed.

Yet this isn’t the core of the plot; nothing comes of the boss’s exasperation. An art film may give us nascent conflicts but never develop them, or pay them off. Characters may come and go without preparation, and chance events may divert the plot. Are these tactics more realistic than what we get in tightly plotted films? Some would say so; they’d say it’s more like the way life moves. In any event, it’s an important convention of this filmmaking tradition.

Parallels matter more than causality in many art films. While Oriol confronts job problems, Yolanda chats with other teachers. They consider the fact that kids don’t like foods that they’ll enjoy when they grow up. She suggests adding some chorizo to lentils, accentuating her as a Spaniard teaching in Paris.

Again a routine is invoked, but now we get a good look at the woman we’ll be seeing a lot of. Unlike the distant shots we’ve had so far, this shows us her curly hair, sharp chin, and gleaming eyes. The gentle, easygoing nature she revealed in shot 7 is confirmed. The film is introducing us to her very gradually, again through routines.

A variant of shot 3 (but Dad now with both daughters) and shot 4 (both daughters with Mom). The girls are waiting for their music teacher and Oriol keeps them amused. His closeness to them is reiterated, so that later when he changes his attitude, that becomes more marked.

Again the emphasis falls on everyday “undramatic” activities. Rosales is really pushing his luck. “For a long time,” wrote one critic, “nothing much is happening and the feeling of directorial self-indulgence is tangible.” Actually, we’re only fifteen minutes into the film at the end of this shot. Patience, please.

Some would say that the movie could begin here; many movies would. The parents are together in bed (so it’s presumably not a split-up family) and sharing time with the kids. They’re telling each daughter how she was born. One came out yelling, the other as if swimming.

Again, though, it’s all in the staging. We scarcely ever glimpse the daughters’ faces, and at many moments, as in my frame here, the parents are blocked by the kids. Like the slit composition in shot 2, the silhouette of shot 5, and the distant framing of shots 4, 6b, and 11, this shot gives us a willfully stingy stream of information. But the presentation is consistent with the staging and framing that contribute to the film’s intrinsic norm, so we’re not as startled by this shot as we might be if it cropped up in an ordinary film. It also varies the norm: Now characters don’t have to be off frame to be invisible.

Some critics would be inclined to say that this shot, like others “distances” us from the characters and their situation. But we shouldn’t confuse pictorial distance with emotional distance. Long shots can be emotionally wrenching; just look at the last two shots of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. I’d prefer to say that in what could have been a sentimental scene, the composition and the actors’ understated playing keeps the emotion simple and understated.

This is the first time we see the whole family together. It’s also the last. Some art films are quite laconic.

Laconic, did I say? Cut to a rocky landscape and the sound of a car engine. Is a car visible in the shot? Two screenings in 35mm didn’t reveal it to me. Again we’re invited to suspend our narrative interest and study a space.

Soon we’ll learn that this shot stands in for the travel to visit the grandparents. The bed scene makes no mention of the upcoming trip, so this landscape comes as a surprise. The moment reminds us that the film lacks cohesion devices, those elements that tie scenes together through:

Plans: For instance, maybe “Tomorrow you get to go see Grandma and Grandpa!”

Appointments: “Don’t forget you have to get up early for the trip!”

Deadlines: “Oriol, can you make it there before nightfall?”

Hooks: Those lines of dialogue that link the end of one scene with the beginning of another :”Don’t you love that wrinkled terrain near where your father and mother live?”/ cut to landscape.

Mainstream plotting tries to bind one scene to another tightly, making their succession seem smooth and inevitable. We’ve become so used to this that many art films feel fragmentary. We can’t easily predict what we’ll see next. After all the images of people, Rosales’ “empty” shot is surprising.

This refusal of tight scene-to-scene connections creates a different sense of time and forward-moving action. Movies like Sueño y silencio present life as one damn thing after another, not necessarily one damn thing because of another.

In laying out those possible transitions, I just construed shot 13 retrospectively, knowing what came next. The action’s causality has to be figured out afterward; we often have to think to understand what we’ve just seen. This is one of many reasons that we must often watch such movies twice (or more) to appreciate them fully.

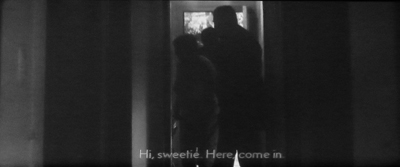

Now more opaque/oblique presentation. An old man comes through a doorway, illuminated briefly.

As the old man becomes a silhouette, another silhouette emerges. It must be Oriol, by his voice and his glasses, but we have to pay attention to be sure. Is Yolanda there too? And the daughters?

the even more obscure figure of a woman comes bustling in from the right and starts speaking to someone in the adjacent room. “Hi, sweetie!” Our inference engines have to work up exposition again. Older couple: probably grandparents. Grandma doting on (unseen) granddaughter. But only one daughter? And no Yolanda?

Yes, only one daughter came. “One is better than none,” Grandma says as she leads the girl–on a big screen, you can make out that it’s Celia–to the foreground and out right. And no sign of Yolanda, so we must infer that Oriol made the trip only with the one daughter Celia. Hollywood tends to tell you important story points three times; art movies, less often. It’s the mystery-story model again: basic information is given through clues and hints.

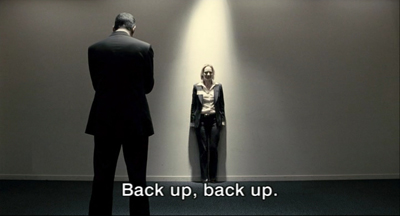

Finally, delivering on the early line of dialogue in which Oriol says he’ll move the car, the camera dwells on the corridor. Then we see the car backing up. Ending with the distant doorway we saw at the start, the shot is given a neat curve of development.

It would have been much simpler to show an exterior long shot of the house, the old folks coming out toward the camera to greet the car as it pulls up, Oriol and Celia climbing out, hugs all around, and so on. But then we wouldn’t have been as actively engaged in the way the scene develops; we’d immediately label it “Family visit.”

One way to think of art-movie conventions is that they’re reworking of elementary story actions we’ve seen before, but transformed through choices about narration (suppress some information) and visual and auditory style (choose an elliptical or “difficult” way of shooting the action). I think this tendency is one reason some critics think that such films heighten our awareness of both ordinary life and the conventions of art. “The Dream and the Silence,” says one, “is the work of someone with enormous intelligence and a need to see the world afresh.”

Surely not every viewer will grasp the points I just made. (I didn’t myself on the first viewing.) Any artwork needs some redundancy, so the next shot/ scene stabilizes our understanding of the situation. It’s now clear that Celia and her father have come for a holiday. She goes walking in the forest with her grandmother, who explains about grasses and trees on their property. They wander out of the frame, and the camera drifts away from them. Their conversation fades out, and the camera continues its trajectory….

…until it stops at a dark mass of bushes. Why?

I wish I could answer with confidence. The camera movement is a complement to the forward tracking we saw in the construction site during shot 6, but that’s not enough to explain the strong emphasis given to this foliage. Is it meant to evoke the rough, Art-Brut look of the painting in shot 1? Given what comes in the next five minutes, are these brambles a premonition of catastrophe?

In a way, the shot brings us back to the watercolor painting of the opening. In films like this, there will always be some images, sounds, or scenes that resist easy sense-making. They become interpretive nodes for critics to probe, sometimes for years.

These fifteen shots constitute the film’s first reel, and they lock in place many of the intrinsic norms. But these norms won’t simply be repeated in the course of what follows. They will be varied in cunning ways. The omission of certain information will keep us in suspense, heightened by framing that excludes what we need to know. After we’ve become used to the norm of the offscreen speaker or listener, one later shot will use it surprisingly, with disquieting emotional effect. After shots in black-and-white, two are in color. After the rigorous objectivity of what we’ve seen so far, we’re surprised to see a shot that is likely to be a hallucination. And the film’s one optical POV passage will be decoupled from its owner, in both time and space.

The variations keep us engaged in the ongoing effort to assemble a coherent story, with each scene forcing us to rethink the one that it replaced while sensing the emotional currents at play within both of them. In Sueño y silencio, the conventions of art cinema allow Rosales to present profound pain with a measure of tranquility. We can register this mixed emotion all more acutely because we’ve participated in creating it. We grasp the conventions he’s exploiting, and we can enjoy seeing them employed in fresh ways.

There are several scenes from Sueño y silencio on YouTube, but I wouldn’t necessarily suggest watching them. They’re pretty meaningless out of context. See this review for a little background on the making of the film. Rosales claims that he used nonactors and let them improvise their scenes.

The ideas in this entry are reworkings of points I’ve made elsewhere, notably in Narration in the Fiction Film and in the essay “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice.” If you’re interested in that essay, I’d prefer you read the revised version in Poetics of Cinema. On this site, another analysis of intrinsic norms in an art film is the entry on the excellent In the City of Sylvia.

I’m grateful to Cinédecouvertes, the annual festival conducted by the Cinematek of Brussels, and specifically to Sam DeWilde for bringing Sueno y silencio. Thanks also to Clémentine De Blieck for technical assistance and to Gabrielle Claes for enlightening conversation about the film.

Sueno y silencio: Miquel Barceló paints “El sacrificio de Cristo.”

Nolan vs. Nolan

DB here:

Paul Thomas Anderson, the Wachowskis, David Fincher, Darren Aronofsky, and other directors who made breakthrough films at the end of the 1990s have managed to win either popular or critical success, and sometimes both. None, though, has had as meteoric a career as Christopher Nolan.

His films have earned $3.3 billion at the global box office, and the total is still swelling. On IMDB’s Top 250 list, as populist a measure as we can find, The Dark Knight (2008) is ranked number 8 with over 750,000 votes, while Inception (2010), at number 14, earned nearly 600,000. The Dark Knight Rises (2012), on release for less than a month, is already ranked at number 18. Remarkably, many critics have lined up as well, embracing both Nolan’s more offbeat productions, like Memento (2000) and The Prestige (2006), and his blockbusters. Nolan is now routinely considered one of the most accomplished living filmmakers.

Yet many critics fiercely dislike his work. They regard it as intellectually shallow, dramatically clumsy, and technically inept. As far as I can tell, no popular filmmaker’s work of recent years has received the sort of harsh, meticulous dissection Jim Emerson and A. D. Jameson have applied to Nolan’s films. (See the codicil for numerous links.) People who shrug at continuity errors and patchy plots in ordinary productions have dwelt on them in Nolan’s movies. The attack is probably a response to his elevated reputation. Having been raised so high, he has farther to fall.

I have only a welterweight dog in this fight, because I admire some of Nolan’s films, for reasons I hope to make clear later. Nolan is, I think all parties will agree, an innovative filmmaker. Some will argue that his innovations are feeble, but that’s beside my point here. His career offers us an occasion to think through some issues about creativity and innovation in popular cinema.

Four dimensions, at least

First, let’s ask: How can a filmmaker innovate? I see four primary ways.

You can innovate by tackling new subject matter. This is a common strategy of documentary cinema, which often shows us a slice of our world we haven’t seen or even known about before—from Spellbound to Vernon, Florida.

You can also innovate by developing new themes. The 1950s “liberal Westerns” substituted a brotherhood-of-man theme for the Manifest-Destiny theme that had driven earlier Western movies. The subject matter, the conquest of the West by white settlers and a national government, was given a different thematic coloring (which of course varied from film to film). Science fiction films were once dominated by conceptions of future technology as sleek and clean, but after Alien, we saw that the future might be just as dilapidated as the present.

Apart from subject or theme, you can innovate by trying out new formal strategies. This option is evident in fictional narrative cinema, where plot structure or narration can be treated in fresh ways. Many entries on this blog have charted possible formal innovations, such as having a house narrate the story action, or arranging the plot so as to create contradictory chains of events. Documentaries have experimented with a film’s overall form as well, of course, as The Thin Blue Line and Man with a Movie Camera. Stan Brakhage’s creation of “lyrical cinema” would be an example of formal innovation in avant-garde cinema.

Finally, you can innovate at the level of style—the patterning of film technique, the audiovisual texture of the movie. A clear example would be Godard’s jump cuts in A Bout de souffle, but new techniques of shooting, staging, framing, lighting, color design, and sound work would also count. In Cloverfield and Chronicle, the first-person camera technique is applied, in different ways, to a science-fiction tale. Often, technological changes trigger stylistic innovation, as with the Dolby ATMOS system now encouraging filmmakers to create sound effects that seem to be occurring above our heads.

I see other means of innovation—for instance, stunt casting, or new marketing strategies—but these four offer an initial point of departure. How then might we capture Nolan’s cinematic innovations?

Style without style

Well, on the whole they aren’t stylistic. Those who consider him a weak stylist can find evidence in Insomnia (2002), his first studio film. Spoilers ahead.

A Los Angeles detective and his partner come to an Alaskan town to investigate the murder of a teenage girl. While chasing a suspect in the fog, Dormer shoots his partner Hap and then lies about it, trying to pin the killing on the suspect. But the suspect, a famous author who did kill the girl, knows what really happened. He pressures Dormer to cover for both of them by framing the girl’s boyfriend. Meanwhile, Dormer is undergoing scrutiny by Ellie, a young officer who idolizes him but who must investigate Hap’s death. And throughout it all, Dormer becomes bleary and disoriented because, the twenty-four-hour daylight won’t let him sleep. (His name seems a screenwriter’s conceit, invoking dormir, to sleep.)

Nolan said at the time that what interested him in the script—already bought by Warners and offered to him after Memento—was the prospect of character subjectivity.

A big part of my interest in filmmaking is an interest in showing the audience a story through a character’s point of view. It’s interesting to try and do that and maintain a relatively natural look.

He wanted, as he says on the DVD commentary, to keep the audience in Dormer’s head. Having already done that to an extent in Memento, he saw it as a logical way of presenting Dormer’s slow crackup.

But how to go subjective? Nolan chose to break up scenes with fragmentary flashes of the crime and of clues—painted nails, a necklace. Early in the film, Dormer is studying Kay Connell’s corpse, and we get flashes of the murder and its grisly aftermath, the killer sprucing up the corpse.

At first it seems that Dormer intuits what happened by noticing clues on Kay’s body. But the film’s credits started with similar glimpses of the killing, as if from the killer’s point of view, and there’s an ambiguity about whether the interpolated images later are Dormer’s imaginative reconstruction, or reminders of the killer’s vision—establishing that uneasy link of cop and crook that is a staple of the crime film.

Similarly, abrupt cutting is used to introduce a cluster of images that gets clarified in the course of the film. At the start, we see blood seeping through threads, and then shots of hands carefully depositing blood on a fabric (above). Then we see shots of Dormer, awaking jerkily while flying in to the crime scene. Are these enigmatic images more extracts from the crime, or are they something else? We’ll learn in the course of the film that these are flashbacks to Dormer’s framing of another suspect back in Los Angeles. Once again, these images get anchored as more or less subjective, and they echo the killer’s patient tidying up.

Nolan’s reliance on rapid cutting in these passages is typical of his style generally. Insomia has over 3400 shots in its 111 minutes, making the average shot just under two seconds long. Rapid editing like this can suit bursts of mental imagery, but it’s hard to sustain in meat-and-potatoes dialogue scenes. Yet Nolan tries.

In lectures I’ve used the scene in which Dormer and Hap arrive at the Alaskan police station as an example of the over-busy tempo that can come along with a style based in “intensified continuity.” In a seventy-second scene, there are 39 shots, so the average is about 1.8 seconds—a pace typical of the film and of the intensified approach generally.

Apart from one exterior long-shot of the police station and four inserts of hands, the characters’ interplay is captured almost entirely in singles—that is, shots of only one actor. Out of the 34 shots of actors’ faces and upper bodies, 24 are singles. Most of these serve to pick up individual lines of dialogue or characters’ reactions to other lines. The singles are shot with telephoto lenses, a choice exemplifying what I called the tendency toward “bipolar” lens lengths in intensified continuity–that is, either very long lenses or fairly wide-angle ones.

Fast cutting like this need not break up traditional spatial orientation. In this scene, there are a couple of bumps in the eyeline-matching, but basically continuity principles are respected. As Nolan explains on the DVD commentary, he tried to anchor the axis of action, or 180-degree line, around Dormer/Pacino, so the eyelines were consistent with his position, and that’s usually the case here.

I can’t illustrate all the shots here, but despite its more or less cogent continuity, the scene seems to me choppy, uneconomical, and fairly perfunctory in its stylistic handling. Nolan makes no effort to move the actors around the set in a way that would underscore the dramatic development. Because of the rapid editing, characters’ lines and gestures are cut off or unprepared for. There is no effort to design each shot, à la Hitchcock, to fit the line or reaction of the actor. Most shots are excerpted from full takes, all from the same setup. The most obvious example is the setup that pans to show Dormer as he comes in, stops, and reacts to the conversation. Thirteen shots are taken from that setup (not necessarily the same full take, of course, as the last frame here shows).

In Nolan’s recent films, this avoidance of tightly designed compositions may be encouraged further because he’s shooting in both the 1.43 Imax ratio and the 2.40 anamorphic one. There remains a general tendency toward loose, roughly centered framings.

Somebody is sure to reply that the nervous editing is aiming to express Dormer’s anxiety about the investigation into his career. But that would be too broad an explanation. On the same grounds, every awkwardly-edited film could be said to be expressing dramatic tensions within or among the characters. Moreover, even when Dormer’s not present, the same choppy cutting is on display.

Consider the 23 shots showing Ellie greeting Dormer and Hap as they get off the plane. Again we have full production takes broken up into brief phases of action (it takes five shots to get Dormer out of the plane), with an almost arbitrarily succession of shot scales. When Ellie leaves her vehicle to go out on the pier, the action is presented in nine shots.

We can imagine a simpler presentation—perhaps after an establishing shot, we track with Ellie down along the dock (so we can see her smiling anticipation), then pan with her walking leftward into a framing that prepares for the plane hatch to open. Arguably, the need to show off production values—the vast natural landscape, the swooping plane descending—pressed Nolan to include some of the extra shots. They don’t do much dramatically, and the strange cut back to an extreme long-shot (to cover the change to a new angle on Ellie?) may negate whatever affinity with her that the closer shots aim to build up.

Swedish sleeplessness

Magic Mike.

Want an up-to-date comparison? Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike has a quiet, clean style that conveys each story point without fanfare. Soderbergh saves his singles for major moments and drops back for long-running master shots when character interaction counts. His cuts are just that; they trim fat. He doesn’t resort to those short-lived push-in camera movements that Nolan seems addicted to. He doesn’t waste time with filler shots of people going in and out of buildings, or aerial views of a cityscape. Soderbergh can provide an unfussy 70s-ish telephoto long take of Mike and Brooke walking along a pier and settling down at a picnic table in front of a Go-Kart track while her brother Adam materializes in the distance. In a single year, with Contagion, Haywire, and Magic Mike, Soderbergh has confirmed himself as our master of the intelligent midrange picture. To anyone who cares to watch, these movies give lessons in discreet, compact direction.

For a more pertinent contrast case, we can go back Insomnia’s source, the 1997 Norwegian film of the same name written and directed by Erik Skjoldbjaerg. Here a Swedish detective, vaguely under suspicion for an infraction of duty, comes to a town on the Arctic Circle for a murder investigation. The plot is roughly similar in its premise, but the working out is quite different, and I can’t do justice to it here. Let me mention just two points of contrast.

First, the cutting is less jagged. Skjoldbjaerg’s film comes in at ninety-seven minutes, about fifteen minutes shorter than Nolan’s, and its cutting rate is much slower, around 5.4 seconds. That means that many passages are built out of sustained shots, particularly ones showing the detective Jonas Engström walking or sitting in a brooding, self-contained silence. Also, this version finds ways to convey several bits of information concisely, in carefully designed shots. For a straightforward example: We see Engstrom’s eyes open, as he’s unable to sleep, and then he lifts his head. Rack focus to the clock behind him.

Nolan uses several shots to get across a comparable point.

As for subjectivity, Skoldbjaerg is just as keen to get us inside his detective’s head as Nolan is. At times he uses the sort of flash-cutting Nolan employs, so we get fragmentary reminders of the fog-clouded shooting. But Skoldbjaerg doesn’t tease us with unattributed inserts (Nolan’s flashbacks to Dormer’s framing of a suspect), and he never suggests, via images of the murder and its cleanup, that his detective can imagine the crime concretely. Instead, Skoldbjaerg often evokes his character’s unease through camera movements that upset our sense of his spatial location. The camera shows Engstrom striding into a room…and then swivels rightward to show him in his original location, as if he’s sneaked around behind our back.

Then Engstrom turns, and we hear a footstep. Cut to a shot showing that the sound is made by him, walking in another room.

I’m not going to suggest that Skoldbaerg innovates more radically than Nolan does, though most viewers probably are more startled by these devices than by Nolan’s. I think that the original Insomnia’s stylistic gamesmanship owes something to other precedents, going back to Dreyer’s Vampyr. What I find more interesting is that Nolan had available the prior example of these strategies from his Nordic source, and he still chose to go with the more conventional, cutting-based options.

The editing-driven, somewhat catch-as-catch-can approach to staging and shooting is clearly Nolan’s preference for many projects. He doesn’t prepare shot lists, and he storyboards only the big action sequences. As his DP Wally Pfister remarks, “What I do is not complicated.” Comparing their production method to documentary filming, he adds: “A lot of the spirit of it is: How fast can we shoot this?”

Throwing it against the wall

We can find this loose shooting and brusque editing in most of Nolan’s films, and so they don’t seem to me to display innovative, or particularly skilful, visual style. I’m going to assume that his strengths aren’t in the choice of subjects either, since genre considerations have kept him to superheroics and psychological crime and mystery. I think his chief areas of innovation lie in theme and form.

The thematic dimension is easy to see. There’s the issue of uncertain identity, which becomes explicit in Memento and the Batman films. The lost-woman motif, from Leonard’s wife in Memento to Rachel in the two late Batman movies, gives Nolan’s films the recurring theme of vengeance, as well as the romantic one of the man doomed to solitude and unhappiness, always grieving. If this almost obsessive circling around personal identity and the loss of wife or lover carries emotional conviction, it owes a good deal to the performances of Guy Pearce, Hugh Jackman, Christian Bale, and Leonardo DiCaprio, who put some flesh on Nolan’s somewhat schematic situations.

You can argue that these psychological themes aren’t especially original, especially in mystery-based plots, but the Batman films offer something fresher. The Dark Knight trilogy has attracted attention for its willingness to suggest real-world resonance in comic-book material. Umberto Eco once objected that Superman, who has the power to redirect rivers, prevent asteroid collisions, and expose political corruption, devotes too much of his time to thwarting bank robbers. Nolan and his colleagues have sought to answer Eco’s charge by imbuing the usual string of heists, fights, chases, explosions, kidnappings, ticking bombs, and pistols-to-the-head with sociopolitical gravitas. The Dark Knight invokes ideas about terrorism, torture, surveillance, and the need to keep the public in the dark about its heroes. Something similar has happened with The Dark Knight Rises, leaving commentators to puzzle out what it’s saying about financial manipulation, class inequities, and the 99 percent/ 1 percent debate.

Nolan and his collaborators are doubtless doing something ambitious in giving the superhero genre a new weightiness. Yet I found The Dark Knight Rises, like its predecessor, unable to bear the burden. It seemed to me at once pretentious and confused in a manner typical of Hollywood’s traditional handling of topical themes.

The confusion comes into focus when journalists, needing an angle on this week’s release, look for a coherent reflection of that elusive, probably imaginary zeitgeist. I think that most popular films don’t capture the spirit of the time, assuming such a thing exists, but simply opportunistically stitch together whatever lies to hand. Let me recycle what I wrote four years ago.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). . . .

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do that. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Since I wrote that, Nolan has confirmed my hunch. He says of the new Batman movie:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. . . . We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story.

Just to be clear, I don’t think the just-telling-a-story alibi is bulletproof. The cultural mix on display in a movie can still exclude certain ideological possibilities, or frame the materials in ways that slant how spectators take them up. My point is only that we ought not to expect popular movies, or indeed many movies, to offer crisp, transparent visions of politics or society. Thematic murkiness and confusion are the norm, and the movie’s inconsistencies may reflect nothing more than the makers’ adroit scavenging.

Subjectivity and crosscutting

Nolan’s innovations seem strongest in the realm of narrative form. He’s fascinated by unusual storytelling strategies. Those aren’t developed at full stretch in Insomnia or the Dark Knight trilogy, but other films put them on display.

One way to capture his formal ambitions, I think, is to see them as an effort to reconcile character subjectivity with large-scale crosscutting. Nolan has pointed out his keen interest in both strategies. But on the face of it, they’re opposed. Techniques of subjectivity plunge us into what one character perceives or feels or thinks. Crosscutting typically creates much more unrestricted field of view, shifting us from person to person, place to place. One is intensive, the other expansive; one is a local effect, the other becomes the basis of the film’s enveloping architecture.

The Batman trilogy has plenty of crosscutting, but as far as I can tell, subjectivity takes a back seat. Nolan’s first two films reconcile subjectivity and crosscutting in more unusual ways. Following takes a linear story, breaks it into four stretches, and then intercuts them. But instead of expanding our range of knowledge to many characters, nearly all the sections are confined to what happens to one protagonist, and they’re presented as his recounted memories in a Q & A situation.

Likewise, Memento confines us to a single protagonist and skips between his memories and immediate experiences. Again what might be a single, linear timeline is split, but then one series of incidents is presented as moving chronologically while another is presented in reverse order. Again, the competing time trajectories aren’t presented as large blocks but are fairly swiftly crosscut.

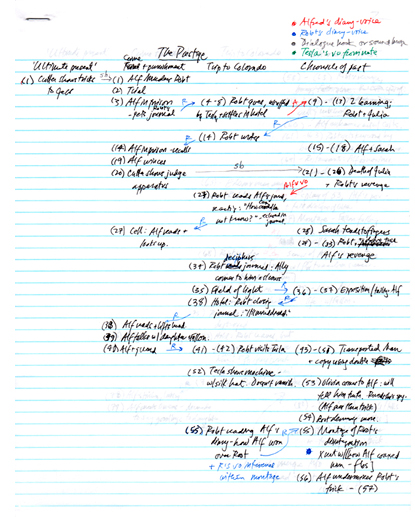

In The Prestige, dual protagonists, both with a secret, take over the story, but the presentation remains steeped in subjectivity. Now much of the action is filtered through each magician’s notebook of jottings and recollections, translated into voice-over commentary. One character may be reading another’s notebook in which the writer reports reading the first character’s notebook! And of course these tales-within-tales are intercut, with one man’s frame story alternating with the other’s past experience. You can work it all out diagrammatically, as I tried to do in my notes (on right).

In The Prestige, dual protagonists, both with a secret, take over the story, but the presentation remains steeped in subjectivity. Now much of the action is filtered through each magician’s notebook of jottings and recollections, translated into voice-over commentary. One character may be reading another’s notebook in which the writer reports reading the first character’s notebook! And of course these tales-within-tales are intercut, with one man’s frame story alternating with the other’s past experience. You can work it all out diagrammatically, as I tried to do in my notes (on right).

With Inception, subjectivity takes the shape of dreaming, and the crosscutting is now among layers of dreams. The embedding that we find in The Prestige is now carried to an extreme; in the long, climactic final sequence a group dream frames another dream which frames another, and so on, to five levels. Once again, these all get intercut (although Nolan wisely refrains from reminding us of the outermost frame too often, so that our eventual return to it can be sensed more strongly).

Kristin and I have written at length about these strategies in earlier entries (here and here). To recapitulate, Kristin found Inception‘s reliance on continuous exposition a worthwhile experiment, and I argued that the lucid-dreaming gimmick was simply a motivational strategy, a pretext for connecting multiple plotlines through embedding rather than parallel action. My point in the first essay is summed up here:

As ambitious artists compete to engineer clockwork narratives and puzzle films, Nolan raises the stakes by reviving a very old tradition, that of the embedded story. He motivates it through dreams and modernizes it with a blend of science fiction, fantasy, action pictures, and male masochism. Above all, the dream motivation allows him to crosscut four embedded stories, all built on classic Hollywood plot arcs. In the process he creates a virtuoso stretch of cinematic storytelling.

My later thoughts tried to survey the breadth of Nolan’s development of formal strategies. Here’s my conclusion:

From this perspective, Inception marks a step forward in Nolan’s exploration of telling a story by crosscutting different time frames. You can even measure the changes quantitatively. Following contains four timelines and intercuts (for the most part) three. Memento intercuts two timelines, but one moves backward. Like Following, The Prestige contains four timelines and intercuts three, but it opens the way toward intercutting embedded stories. The climax of Inception intercuts four embedded timelines, all of them framed by a fifth, the plane trip in the present. For reasons I mentioned in the previous post, it’s possible that Nolan has hit a recursive limit. Any more timelines and most viewers will get lost.

The Dark Knight Rises hasn’t dulled my respect for Nolan’s ambitions. Very few contemporary American filmmakers have pursued complex storytelling with such thoroughness and ingenuity.

Nolan has made his innovations accessible, I argued, by the way he has motivated them. First, he appeals to genre conventions. Following and Memento are neo-noirs, and we expect that mode to traffic in complex, perhaps nearly incomprehensible plotting and presentation. He has called Inception a heist film, and what many viewers objected to—its constant explanation of the rules of dream invasion—is not so far from the steady flow of information we get in a caper movie. In the heist genre, Nolan remarks, exposition is entertainment. Further, the separate dreams rely on familiar action-movie conventions: the car chase that ends with a plunge into space, the fight in a hotel corridor, the assault on a fortress, and so on.

But I should have mentioned another method of motivation–one that helps make the films comprehensible to a broad audience. In some cases the formal trickery is justified by the very subjectivity the film embraces. It’s one thing to tell a story in reverse chronology, as Pinter does in Betrayal; but Memento’s broken timeline gets extra motivation from the protagonist’s purported (not clinically realistic) anterograde memory loss. (We’ve already seen a lot of amnesia in film noirs.) Subjectivity is enhanced by the almost constant voice-over narration, reiterating not only Leonard’s thoughts but what he writes incessantly on his Polaroids and his flesh.

In The Prestige, each magician’s journal records not only his trade secrets but his awareness that his rival might be reading his words, so we ought to expect traps and false trails. And in Inception, the notion of plunging into a character’s mind becomes literalized as a dream state. Once we accept the conceit of controlled dreaming, we can buy all the spatial and temporal constraints the dream-master Cobb sets forth. As with Memento, Nolan creates a set of rules that allow him to crosscut many different time lines. In each film, the subject matter—memory failure, magicians’ enigmas, controlled dreaming—serves as an alibi for both subjectivity and broken timelines.

Synching story and style

Can you be a good writer without writing particularly well? I think so. James Fenimore Cooper, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis, and other significant novelists had many virtues, but elegant prose was not among them. In popular fiction we treasure flawless wordsmiths like P. G. Wodehouse and Rex Stout and Patricia Highsmith, but we tolerate bland or clumsy style if a gripping plot and vivid characters keep us turning the pages. From Burroughs and Doyle to Stieg Larsson and Michael Crichton, we forgive a lot.

Similarly, Nolan’s work deserves attention even though some of it lacks elegance and cohesion at the shot-to-shot level. The stylistic faults I pointed to above and that echo other writers’ critiques are offset by his innovative approach to overarching form. And sometimes he does exercise a stylistic control that suits his broader ambitions. When he mobilizes visual technique to sharpen and nuance his architectural ambitions, we find a solid integration of texture and structure, fine grain and large pattern.

Here’s a one-off example. Nolan has remarked that he’s mostly not fond of slow-motion simply to accentuate a physical action, or to suggest some mental state like dream or memory. Inception motivates slow-motion by another of its arbitrary rules, the idea that at each level of dreaming time moves at a different rate. Here a stylistic cliché is transformed by its role in a larger structure, as Sean Weitner pointed out in a message to us.

Memento displays a more thoroughgoing recruitment of style to the purposes of guiding us through its labyrinth. The jigsaw joins of the plot require that the head and tail of each reverse-chronology segment be carefully shaped, because they will be reiterated in other segments. Within the scenes as well, Nolan displays a solid craftsmanship, with mostly tight shot connections and an absence of stylistic bumps.

He can even slow things down enough for a fifty-second two-shot that develops both drama and humor. Leonard has just shown Teddy the man bound and gagged in his closet, and Teddy wonders how they can get him out. In a nice little gag, Leonard produces a gun from below the frameline (we’ve seen him hide it in a drawer) and then reflects that it must be his prisoner’s piece. This sort of use of off-frame space to build and pay off audience expectations seems rare in Nolan’s scenes.

The moment is capped when Leonard adds, “I don’t think they let someone like me carry a gun,” as he darts out of the frame.

The straightforward stylistic treatment of Memento‘s more-or-less present-time scenes, both chronological and reversed, is counterbalanced by the rapid, impressionistic handheld work that characterizes Leonard’s flashbacks to his domestic life and his wife’s death (in color) and his flashbacks to the life of Sammy Jankis (in black-and-white). Nolan shrewdly segregates his techniques according to time zone.

If anything, The Prestige displays even more exactitude. Facing two protagonists and many flashbacks and replayed events, we could easily become lost. Here Nolan doesn’t use black-and-white to mark off a separate zone. Instead he relies more on us to keep all the strands straight, but he helps us with voice-overs and repeated and varied setups that quietly orient us to recurrent spaces and circumstances. Here Nolan’s preference for cutting together singles is subjected to a simple but crisp logic that relies on our memory to grasp the developing drama.

I’ve discussed these stylistic strategies in another entry and in Chapter 7 of Film Art. More generally, they serve the larger dynamic of the plot, which creates a mystery around Alfred Borden, hides crucial information while hinting at it, invites us to sympathize with Borden’s adversary Robert Angier (another widower by violence), and then shifts our sympathies back to Borden when we learn how the thirst for revenge has unhinged Robert. To achieve the unreliable, oscillating narration of The Prestige, Nolan has polished his film’s stylistic surface with considerable care.

Midcult auteur?

Trying to specify Nolan’s innovations, I’m aware that one response might be this: Those innovations are too cautious. He not only motivates his formal experiments, he over-motivates them. Poor Leonard, telling everyone he meets about his memory deficit, is also telling us again and again, while the continuous exposition of Inception would seem to apologize too much. Films like Resnais’ La Guerre est finie and Ruiz’s Mysteries of Lisbon play with subjectivity, crosscutting, and embedded stories, but they don’t need to spell out and keep providing alibis for their formal strategies. In these films, it takes a while for us to figure out the shape of the game we’re playing.

We seem to be on that ground identified by Dwight Macdonald long ago as Midcult: that form of vulgarized modernism that makes formal experiment too easy for the audience. One of Macdonald’s examples is Our Town, a folksy, ingratiating dilution of Asian and Brechtian dramaturgy. Nolan’s narrative tricks, some might say, take only one step beyond what is normal in commercial cinema. They make things a little more difficult, but you can quickly get comfortable with them. To put it unkindly, we might say it’s storytelling for Humanities majors.

Much as I respect Macdonald, I think that not all artistic experiments need to be difficult. There’s “light modernism” too: Satie and Prokofiev as well as Schoenberg, Marianne Moore as well as T. S. Eliot, Borges as well as Joyce. Approached from the Masscult side, comic strips have given us Krazy Kat and Polly and Her Pals and, more recently, Chris Ware. Nolan’s work isn’t perfect, but it joins a tradition, not finished yet, of showing that the bounds of popular art are remarkably flexible, and imaginative creators can find new ways to stretch them.

Box-office figures for Nolan’s films are compiled from Box Office Mojo. For detailed critiques of Nolan’s style, see Jim Emerson’s entries archived here; Jim’s video essay dissecting one Dark Knight action scene is here. A. D. Jameson’s essays on Inception are here and here.

Nolan discusses the background to Insomnia in John Pavlus, “Sleepless in Alaska,” American Cinematographer 83, 5 (May 2002), 34-45. My quotation about subjectivity comes from pp. 35-36. By the way, Insomnia does create a moment of tense quiet during the longish dialogue between Dormer and the killer Finch (Robin Williams) on the ferry: some sustained two shots give the adversaries time to size each other up (and Pacino gets an occasion to execute some business with an iron pole). Although the setup is broken by some irrelevant cutaways to the passing vistas, perhaps to cover faults in the takes, the sequence shows something of the sustained calm that we find in moments in Memento and The Prestige.

Thanks to Jonah Horwitz for the Wally Pfister link.

Umberto Eco’s 1972 essay, “The Myth of Superman,” appears in his book, The Role of the Reader. Portions are available here. One relevant passage is this: “He is busy by preference, not against black-market drugs nor, obviously, against corrupt administrators or politicians, but against bank and mail-truck robbers. In other words, the only visible form that evil assumes is an attempt on private property” (p. 123; italics in original).

Dwight Macdonald’s 1960 essay is available in Masscult and Midcult. A pdf is online here. Macdonald seems to have softened his demands a bit in later years. He praised 8 1/2, softcore modernism for sure, as Shakespearean in its vivacity. “The general structure–a montage of tenses, a mosaic of time blocks–recalls Intolerance, Kane, and Marienbad, but in Fellini’s hands it becomes light, fluid, evanescent. And delightfully obvious.” The essay is reprinted in Dwight Macdonald on Movies, pp. 15-31.

J. J. Murphy has a detailed analysis of Memento in his book Me and You and Memento and Fargo. I discuss the film’s contribution to complex storytelling trends in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 74-82, where I also discuss the notion of intensified continuity editing. We analyze The Prestige‘s narrative, narration, and sound techniques in Film Art: An Introduction (ninth ed., pp. 298-307; tenth ed., pp. 298-306).

P.S. 19 August: Thanks to Guillaume Campreau-Dupras for correcting a film title.

PS 27 August: Thanks to the many bloggers and tweeters who linked to this entry!

The tireless A. D. Jameson has posted another probing critique of Nolan’s Bat-saga, this one concentrating on TDKR, here. While making serious points about Nolan’s use of expository dialogue and the confused politics of the film, the essay also contains some good jokes.

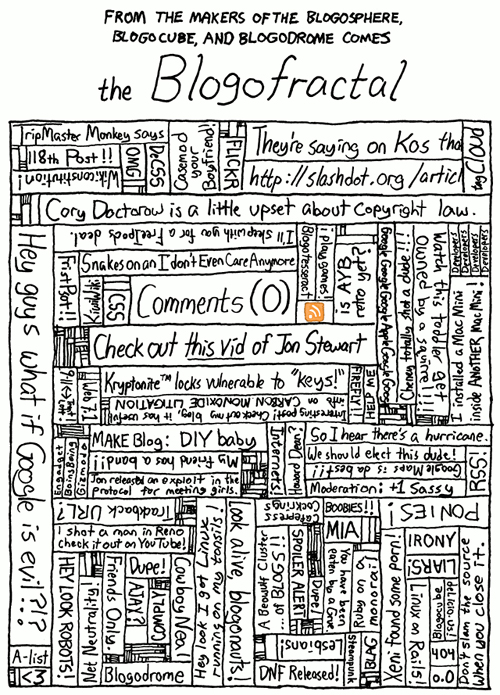

Is there a blog in this class? 2012

From the xkcd webcomic

Kristin here:

August is here, and many film teachers are back from summer research trips and starting to prepare syllabi for the fall. Those who are using the new tenth edition of Film Art will have noticed that tucked away in its margins are references to blog entries relevant to the topics of each chapter. But since the new edition went to press, we’ve kept blogging. As has become our tradition, we offer an update on blogs from the past year that teachers might want to consult as they work on their lectures or assign their classes to read. Even if you’re not a teacher, perhaps you’d be interested in seeing some threads that tie together some recent entries.

For past entries in this series, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011.

First, some general entries about the blog itself and the new edition of Film Art. On our blog’s fifth anniversary last year, we posted a brief historical overview of it. That entry contains some links to some of our most popular items. If you’re new to the blog and want some orientation, it could prove useful. Maybe students would be interested as well. At least the photos reveal our penchant for Polynesian adventure and shameless pursuit of celebrities.

In case you haven’t heard about the changes we made for the new Film Art, including our groundbreaking new partnership with the Criterion Collection to provide online examples with clips from classic movies, there’s a summary post available.

And here’s another entry on the new edition, discussing a new emphasis on filmmakers’ decisions and choices.

Now for chapter-by-chapter links.

Chapter 1

Understanding the movie business often means being skeptical of broad claims about supposed trends. We explained why the widespread “slump” of the movies in 2011 was no such thing in “One summer does not a slump make.”

Trying to keep one step ahead of students (or just keep up with them, period) on the conversion to digital projection and its many implications? Our series “Pandora’s Digital Box” explores many aspects:

In multiplexes: “Pandora’s digital box: In the multiplex”

In small-town theaters: “Pandora’s digital box: The last 35 picture show”

At film festivals: “Pandora’s digital box: At the festival”

On home video: “Pandora’s digital box: From the periphery to the center or the one of many centers”

In art-houses: “Pandora’s digital box: Art house, smart house”

Challenges to film archives: “Pandora’s digital box: Pix and pixels”

How projection is controlled from afar: “Pandora’s digital box: Notes on NOCs”

Problems introduced by digital: “Pandora’s digital box: From films to files”

Another case study of a small-town theater: “Pandora’s digital box: Harmony”

Or you can pay $3.99 and get the whole series, updated and with more information and illustrations, as a pdf file.

3D is a technological aspect of cinematography, but it’s also a business strategy. We explore how powerful forces within the industry used it as a stalking horse for digital projection in “It’s good to be the King of the World” and “The Gearheads.”

Independent films can be the basis for blockbuster franchises. “Indie” doesn’t always equal “small,” as we show in “Indie blockbuster franchise is not an oxymoron.”

One of the top American producers and screenwriters of independent films is James Schamus, head of Focus Features. We profile him in “A man and his focus.”

3D is probably here to stay, but it may have already passed its peak of popularity, as we suggest in “As the summer winds down, is 3D doing the same?”

The late Andrew Sarris played a crucial role in shaping the “auteur” theory of cinema. We talk about his work in “Octave’s hop.”

Chapter 2 The Significance of Film Form

“You are my density” is an analysis of motifs in Hollywood cinema, including a detailed look at a scene from Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

We offer a narrative analysis of a Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, a film many viewers found difficult to follow on first viewing, “TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed.” A follow-up, “TINKER TAILOR once more: Tradecraft,” concentrates on the adaptation of Le Carré’s novel.

A tricky narrative structure in Johnnie To’s Life without Principle called forth our entry, “Principle, with interest.”

In “John Ford and the Citizen Kane assumption,” we consider the possibility that Kane, analyzed in this chapter, might not be the greatest movie ever made.

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-scene

For some reason teachers (and apparently students) always want more, more, more on acting, the most difficult technique of mise-en-scene to pin down. “Hand jive” talks about hand gestures, which in the past were used a lot more than they are now. “Bette Davis eyelids” takes a close look at the subtleties of Bette Davis’ use of her eyes.

“You are my density,” already mentioned, offers several examples of dynamic staging in depth.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style as a Formal System

We have posted two entries dealing with form and style, specifically experimental artifice in 1940s Hollywood. These could be of interest to advanced students. “Puppetry and ventriloquism” deals in general with the topic, while “Play it again, Joan” looks at scenes that replay the same action or situation. The latter contains an analysis of a lengthy scene of Joan Crawford performing that could be useful in discussing staging and acting for Chapter 4.

Chapter 9 Film Genres

If you teach a unit on genre and choose to focus on mysteries, “I love a mystery: Extra-credit reading” gives some historical background information on the genre in popular literature and cinema.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

“Solomonic judgments” centers on the gorgeous experimental films of Phil Solomon.

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

Our discussion of Tokyo Story in Film Art could be supplemented by this brief birthday tribute: “A modest extravagance: Four looks at Ozu.”

Chapter 12 Historical Change in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

Last September I found an extraordinary little piece of formal and stylistic analysis using video, Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912. A Spanish film student, Aitor Gametxo, had displayed the staging and cutting patterns of Griffith’s Biograph short, The Sunbeam, by laying out the shots in a grid reflecting the actual spatial relations among the sets and running the action in real time. If you teach a history unit or just want an elegant, clear example of how editing of contiguous spaces works, this is a wonderful teaching tool. Classes may be particularly intrigued that a student was able to put together something this insightful. Plus The Sunbeam is a charming film that would probably appeal to students more than a lot of early cinema would. See “Variations on a Sunbeam: Exploring a Griffith Biograph film.” Gametxo’s film also provides an elegant example of how editing of adjacent spaces works and could be a useful teaching tool for Chapter 6.

Teachers showing a Georges Méliès film might have their students read “HUGO: Scorsese’s birthday present to George Méliès,” which has some background information on the career of this cinematic conjurer.

German silent film was the focus of “Not-quite-lost shadows.”

Not strictly on the blog, but alongside it, is a survey of how developments in film history generated changes in film theory. The essay is “The Viewer’s Share: Models of Mind in Explaining Film.”

Further general suggestions

Looking for some new and interesting films to add to your syllabus? We cover quite a few in our dispatches from the Vancouver International Film Festival 2011: “Reasons for cinephile optimism,” “Son of seduced by structure,” “Ponds and performers: Two experimental documentaries,” “Middle-Eastern crowd-pleasers in Vancouver,” and “More VIFF vitality, plain and fancy.”

Or if you seek information on historical films newly available on DVD, we occasionally post wrap-ups of recent releases, including a cornucopia of international silent films. See “Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings.”

We have also carried on our tradition of a year-end ten-best list—but of films from 90 years ago. Not all the films on our list for 1921 are on DVD, but most are: “The ten best films of … 1921.”

Every now and then we post an entry pointing to informative DVD supplements that might be useful teaching tools. It’s surprising how few of them go beyond a superficial level where the actors and filmmakers sit around praising each other: “Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something.”

Bon Cinéma! (miaou optional)

The Sorceror and the White Snake.

DB here:

For days, debates about the new Sight and Sound Poll have been saturating the Net ecosystem. The reach of the Web allowed editor Nick James to launch what may be a month-long striptease. (Well played, sir.) And likely you, reader, were weighing lists of masterworks.

But not me. I was watching Japanese space warriors blasting phosphorescent aliens to bits. I saw an amiable cannibal provide gory inspiration for a creatively blocked painter. I saw Dutch layabouts in mullets who made sponging off the system a death sport while calling each other “homo” and kut. I saw an ode to women’s armpit hair, moments of man-on-mule lust, and sexy female snake-demons writhing their way through two movies.

No candidates for the 2022 S & S poll here, but all in all, pretty diverting.

No hecklers, please

Montréal’s annual FanTasia is a three-week tribute to the world’s genre cinema. You get horror, SF, fantasy, martial arts, crime, and tasteless comedy. These movies are bloody, horrifying, outrageous, and hilarious. Nothing says entertainment quite like a wholesome family, complete with babe in arms, being plowed down by a delivery truck.

The name packs in a lot. I think it was first called FantAsia, as befit its early emphasis on Far Eastern imports, but the newer version shifts a little more emphasis to “fan,” which captures the tenor of the audience. Old folks worry that that the young avoid subtitled cinema. They should visit FanTasia, where teens and twentysomethings are happily watching movies from Iceland, Vietnam, Japan, Denmark, Hong Kong, South Korea, Thailand, and Holland. The brains behind this festival know what the kids want.

Don’t confuse this with Camp or Hecklevision. The multititudes come not to mock but admire. I suppose that’s partly because for decades smart genre pictures have woven moments of self-mockery into their texture, so as to mesh with that knowing, ironic attitude that characterizes our consumption of much popular culture. A closed loop: Genre connoisseurs make these movies, and other connoisseurs applaud them. Once you learn that Inglourious Basterds, Shaun of the Dead, Perfect Blue, Killer Joe, and Visitor Q have had premieres of one sort or another here, you get it: This is head-banging, but strictly quality head-banging.

The proof came with DJ XL5 Italian Zappin’ Party. This two-hour mélange of b-movie trailers and clips is a FanTasia tradition, having been preceded by Mexican and Bollywood editions. This year’s brew mixed snippets from fairly famous movies with glimpses of little-known items like Zorro contra Maciste, Spasmo, and The Three Fantastic Supermen. But the result isn’t exactly Camp, and it doesn’t attempt to mimic the media spew we see in Joe Dante’s Movie Orgy. Instead, typical trailers and scenes are tidily arranged in genres–peplum, spaghetti Westerns, giallo, and so on–and left to run at considerable length. Often the clips point up a recurring gesture or bit of iconography (decapitation, musclemen manhandling boulders). It’s less like zapping, more like an otaku assembling clips on a disc or in a file and inviting us over for an evening. Cheesy as many of these items are, we’re invited to appreciate the unpredictable energy of cinema that strives to shock.

The FanTasia tribe has its customs. At each screening, as the lights go down, you hear meowing, sometimes answered by barks or growls. One film started with bleating and clucking on the soundtrack, and this triggered a felicitous barnyard call-and-response; talk about surround sound. Nobody could explain to me the logic behind this FanTasia tradition–like streaking in the 70s, does it mean anything?–but its discreet silliness, perhaps distinctively Canadian, won me over. By the end I was joining in with a cracked miaou of my own. Yet once the movie starts, utter respect rules. Attentive silence is broken by appreciative laughter and whoops at those moments fans call OTT.

The festival’s ambitions are matched by the venues: raked Concordia University auditoriums with enormous screens and sound systems that envelop you. I sat in my favorite spot and didn’t regret it. Both film and digital projection looked sharp and bright. The staff get the audience in and out with dispatch, and everybody I met behaved with courtesy and good humor. Filmmaker Q & As are energetic and pointed. The movies are wild and sometimes abrasive, but the packaging is a model of civilized cine-festivity.

Never gonna grow up

You Are the Apple of My Eye.

The festival made its name with Asian popular cinema, and this year’s schedule didn’t disappoint. I could attend only the last week of screenings, so I missed some of the biggest titles, such as Peter Chan’s Wuxia, to be released in some markets as Dragon (innovative titling, eh? As we say in Canada.) But I did catch several entries.

You Are the Apple of My Eye, a Taiwanese rom-com, provides the now-standard mix of adolescent loutishness, romantic longing, and comic-book special effects. It starts with a twentysomething setting out for a wedding, and through flashbacks and voice-over, we learn of his high-school pranks and his surly affection for a charming girl in his class.

There’s always something touching about a gang of pals going their separate ways after school (viz., American Graffiti), so the film becomes more melancholy as the kids graduate and pass on to college and jobs; the only one who finds worldly success is a girl largely ignored by everyone. The plot shambles along, expecting us to be curious about whether the hero gets the girl he can’t quite learn to woo. The wedding culminates in a gag I found both clever and touching, a prolonged kiss–but not between the bride and our protagonist. And the motif of the ink-stained shirt, shown at beginning and end in a way that suggests a blue-bleeding heart, shows sophisticated sentiment.

School relationships are also character-defining in South Korean comedies, but their impact is more sub rosa in Love Fiction. Joo-wol is blocked after his first novel and is glumly working as a bartender. Attracted to a mysterious young woman, he pours all his literary talent into a Werther/ Cyrano effort to woo her. He even rhapsodizes about, and to, her armpit hair. Once they become a couple, however, he starts to write a murder thriller with her as a femme fatale. But his fiction leads him to investigate Hee-jin’s past, with disturbing results.

I thought this somewhat overlong movie tried to keep too many balls in the air–sequences dramatizing Joo-wol’s detective serial, flashbacks to his childhood, rumors about his girlfriend’s college sex life, and an excursion to Alaska. Again, though, it’s somewhat saved by a feel-good ending featuring Joo-wol’s friends in a scruffy band performing a karaoke video (above). As so often in the genre, stirring music redeems a meandering plot.

You Are the Apple and Love Fiction center on young men who grow up painfully, bruising others in the process, but Vulgaria keeps us firmly planted in adolescence. Pang Ho-cheung, who has done interesting work in You Shoot, I Shoot (a hitman hires a filmmaker to document his killings) and other projects, gives us what is being packaged as Hong Kong’s dirtiest comedy ever. Reliable sources report that no film has ever before contained such filthy Cantonese. It’s not quite as raunchy as it’s billed, though, and it has a predictably soft center.

You Are the Apple and Love Fiction center on young men who grow up painfully, bruising others in the process, but Vulgaria keeps us firmly planted in adolescence. Pang Ho-cheung, who has done interesting work in You Shoot, I Shoot (a hitman hires a filmmaker to document his killings) and other projects, gives us what is being packaged as Hong Kong’s dirtiest comedy ever. Reliable sources report that no film has ever before contained such filthy Cantonese. It’s not quite as raunchy as it’s billed, though, and it has a predictably soft center.