Archive for the 'Directors: Lubitsch' Category

The ten best films of … 1932

Shanghai Express.

Kristin here–

The year draws to a close, and the internet abounds with lists by professional critics, educated fans, and clueless people proffering opinions on the ten best films of 2022. David and I avoid this custom, but fifteen years ago I stumbled into a habit of listing the ten best films of ninety years ago. Such films have by now stood the test of time, and they have one enormous advantage: no one is speculating about many Oscar nominations each will get.

Back in the day, only two of the films on my list got nominated at all, and those two collected a total of three Oscars. (For a hint at one winner, see the image at the top. He will feature prominently in this year’s list.)

These ten films are of course my own choices, and for those who disagree, they are quite welcome to make their own lists.

As usual, my list is a mix of very familiar titles and some not so familiar ones. My hope is to call attention to unfamiliar films that are well worth a look. Actually this year nine of the films should be familiar to any serious film student or fan, but the tenth is a masterpiece that deserves to be rescued from obscurity.

Most historians seem to agree that 1932 was the year when Hollywood emerged from the difficult transition to sound and made polished movies that regained the fluidity of cinematography, staging, and editing that had been lost to some extent. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Janet Staiger, David, and I proposed that the transitional period lasted from 1928 to 1931.

The same was not internationally true, however. My list contains one silent film, since the Japanese industry went through a considerably longer transition. No wonder that half of this year’s list atypically consists of Hollywood movies.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, and 1931.

As usual, I’ll try to point readers toward the best available Blu-rays or DVDs. Those who prefer streaming should be able to find these titles for themselves. David and I prefer discs, at least for important films. With the decline of access t0 35mm and 16mm prints, studying films closely has become more dependent on discs (which also still have better quality images than streaming). Eventually, with streaming the only option obtaining frame grabs of the sort that illustrate these entries, close film analysis will become extremely difficult.

Hooray for Hollywood!

Trouble in Paradise

Ernst Lubitsch is one of the best-loved of film directors, both within the film industry and among cinephiles. I was lucky enough to be invited to teach a one-month summer course at the University of Stockholm on any topic related to silent cinema. I jumped at the chance to follow up on a vaguely planned project on Lubitsch, specifically a comparison of his German and American silent films. The course became a book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, now out of print but available through open access.

Trouble in Paradise is widely considered his best film, though I would say that at least Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Shop around the Corner are equal to it and others are not far behind.

The witty script is a model of sophisticated humor, and the casting is perfect. Herbert Marshall for a change got to play the suave hero, a dazzlingly expert crook who teams up romantically with Miriam Hopkins, his match as a wily pickpocket. In this 82-minute film, their hilarious courtship in a Venice hotel runs for a remarkable 17 minutes as they top each other in stealing things from each other, with her returning his watch and his flaunting her garter:

It doesn’t seem a minute too long. Essence of Lubitsch.

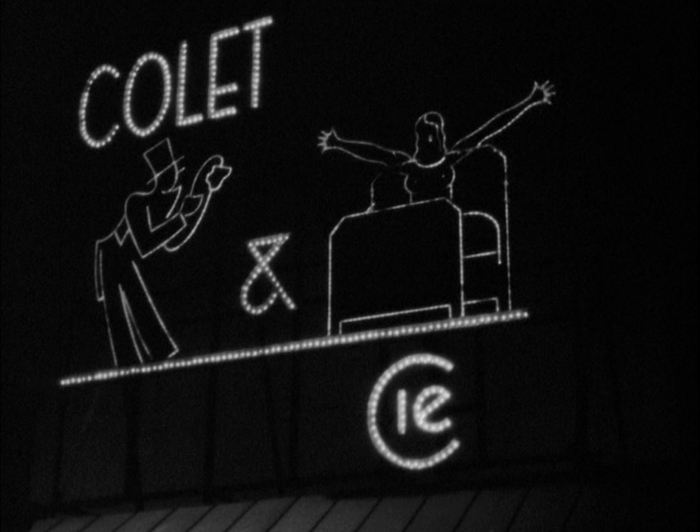

Kay Francis provides the potential trouble that threatens their idyllic life of thievery; she’s a beyond-wealthy owner of perfumery Colet & Cie. (see bottom)–so wealthy that she doesn’t really mind that her “secretary” may be a famous criminal worming his way into her confidence. Charles Ruggles and especially Edward Everett Horton provide hilarity as hopeless suitors wooing Madame Colet.

The comedy is played out in shining art-deco sets (above), lit with perfect three-point Hollywood lighting. As I demonstrate in my book, Lubitsch moved effortlessly from being the master of German silent film style to being the master of Hollywood style. It shows in every aspect of Trouble in Paradise.

The Criterion Collection DVD is still available.

Shanghai Express

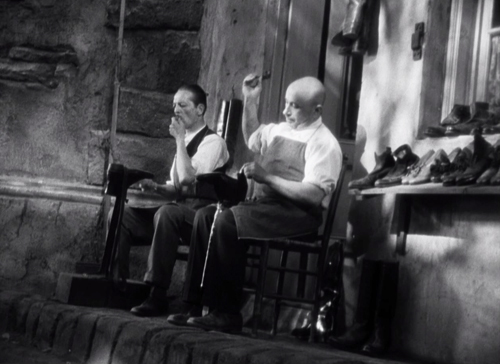

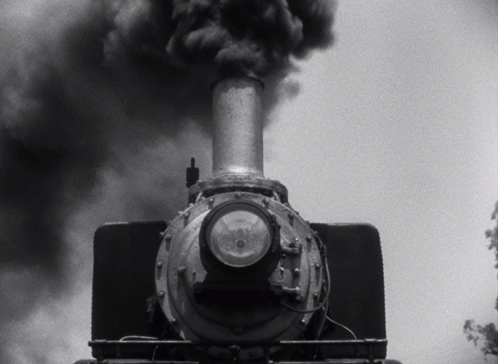

The Josef von Sternberg/Marlene Dietrich teaming. The Blue Angel, featured on my list in 1930. The pair famously made a series of Hollywood films together, all built around the glamor of Dietrich. For me, the best of the bunch is Shanghai Express. It has a stronger script than the others, being set on a train traveling from Beijing to Shanghai during the Chinese Civil War (which had started in 1927). The device of a group on a journey lends the film both unity and suspense. It’s basically a thriller with a romance included. There are more characters than in some of the other Dietrich films, the typical bunch of eccentrics for such journey-plots lending interest, humor, and pathos along the way. Dietrich’s character is strong and likeable. She pursues the man she loves, but on her own terms while he stands around cluelessly keeping his upper lip stiff.

Then there are the incredible visuals. The set design is even more dense than usual for a von Sternberg film. The train windows, both exterior (top) and interior (above) are used brilliantly, and the rebel headquarters where the group is trapped for much of the second half has hanging gauze and stairways that create a complete contrast with the train scenes.

And the Oscar mentioned above went to … Lee Garmes, whose five films in 1932 also included Scarface (see below). Apart from his photography of the settings, he shows off with with other dazzling moments, including an extraordinary tracking shot following an official along the crowded platform for nearly the entire length of the train.

Needless to say, the glamor shots of Dietrich are among the most beautiful ever (Garmes also shot Morocco and Dishonored).

In general, the train station scenes are spectacular and give a remarkable sense of authenticity. Speaking of which, all the extras and minor characters seem to be played by Chinese, or at least Asian people. Anna May Wong has a prominent role as Hui Fei. Whether casting Warner Oland as the rebel leader Henry Chang would count today as “whitewashing” is up for debate. He was born in Sweden but claimed some Mongolian ancestry (so far unproven).

The Criterion Collection has the set of six Dietrich/von Sternberg films on Blu-ray and DVD. (My frames were pulled from an old TCM DVD pairing the film with Dishonored. TCM now offers Shanghai Express by itself on DVD or Blu-ray.)

A Farewell to Arms

The second Oscar-winner of the three mentioned above was Charles Lang, for his cinematography of A Farewell to Arms. (The film also won the third Oscar, for sound recording.)

Frank Borzage has been a staple of these ten-best lists, with Lazybones (1925), 7th Heaven (1927), and Lucky Star (1929). This may be his final appearance in these year-end lists, with growing competition internationally.

A Farewell to Arms adapts Hemingway’s novel of World War I. Gary Cooper plays Frederic, an ambulance medic who spends his spare time drinking and visiting brothels with his friend, Italian Dr. Rinaldi (Adophe Menjou). He meets Catherine, a nurse, at a party, and they fall immediately in love, succumbing to passion under the assumption that war’s uncertainties may not give them another chance. Becoming pregnant, Catherine departs for Switzerland to have the baby, but her letters to Frederic and his to her, are returned to sender. Frederic risks a firing squad by deserting and desperately trying to find her.

Like Trouble in Paradise and other 1932 films, A Farewell to Arms benefited from the fact that the self-censorship Hollywood studios instituted under the Production Code (aka the “Hays code”) in 1933 was not yet in force. The result is a grittier and more honest look at life in wartime than would be possible in later years. Apart from the quite restrained brothel scene (above), there is considerable emphasis on the forbidden unwed motherhood rife among the nurses Catherine works with.

The two stars make a convincing romantic couple of the kind Borzage had become famous for, and the cinematography is lovely. Lang, too, was an expert at creating glamorous images.

Amazon would very much like you to watch the film for free with ads or with a subscription to Paramount+ or with a free Fandor trial or by paying $2.99. Once you scroll past those enticements, you can find Kino Classics release of a Blu-ray or DVD in a remastered version by George Eastman House. It seems a bit overly dark to me, but maybe the original nitrate copy was, too.

Scarface

I have to admit that gangster films are not my favorites. Still, there are outstanding films in the genre, as the presence of von Sternberg’s Underworld on my 1927 list indicates. The early 1930s established the genre solidly, and Scarface stands out among the other classics examples of the time. I have not seen the two other such classics still commonly watched, Public Enemy or Little Caesar, for a very long time, but I recall not being very impressed.

Scarface marks Howard Hawks’s first appearance on one of my lists. It’s not up to his greatest films of the 1930s, Twentieth Century and Only Angels Have Wings (and some would say Bringing Up Baby).

One thing that makes Scarface stand out for me is its considerable use of humor, which seems unusual for a gangster film. Paul Muni, so dignified in his prestigious bio-pics of this same period, lets go and struts with aggressive arrogance, lets go in fits of rage, and makes Tony Camonte a figure of fun with his accent (“That’s putty nice”) and flaunted ignorance. When the woman he’s trying to impress and seduce remarks sarcastically that his clothes are gaudy, he delightedly takes it as a compliment.

The comic relief flirts with slapstick in the figure of Camonte’s “secretary,” who is illiterate, inept, and downright stupid. According to the AFI Catalog, his character name is Angelo, though Camonte addresses him as Dope. There’s a running gag of him being unable to get basic information from callers. At one point during a raging gunfight in a restaurant, he struggles to hear a caller’s name, unaware that a tank behind him has been pierced and is dousing him.

The film also has its visual pleasures. It was one of five films, along with Shanghai Express, that Lee Garmes lensed in 1932. The cinematography is appropriately less glamorous than in Shanghai Express, but it’s dark and occasionally beautiful, as in the hospital-invasion scene at the top of this section.

Many films of the early 1930s start off with an impressive moving-camera shot, presumably to show off before settling down into scenes with standard continuity cutting. Scarface has quite an impressive opening, with a plan sequence leading up to the first act of violence.

It begins with a low angle of a streetlight going out, and then tilts down and tracks rightward past a milk delivery cart and a sign that establishes the locale.

Continuing rightward, it reaches a tired janitor who removes a sign informing us that a stag party had been held there the night before. The camera tracks rights as he starts to clean up.

The camera follows through the wall and continues as he tackles the job in a room festooned with streamers–possibly an homage to the big party scene in Underworld. One artifact of the party that he finds is a brassiere that has lost its owner.

As he pauses, the camera leaves him to pan right and track in on a gang boss and two of his men talking about a potential danger from a rival gangster. He declares that he doesn’t want war and is satisfied with the money he’s making.

The men stand, and the boss promises an even bigger party in a week. Thus for a gangster, he seems a decent sort, not willing to stir up violence against those seeking to invade his territory.

The men leave, and the camera follows the boss across the room and into a phone booth. He starts to make a call.

The camera glides past him and away off to the right, where it picks up a menacing shadow in the next room.

It follows the silhouette as the unknown man walks toward the corridor where the phone booth is. Silhouetted against a translucent window, he pulls a gun, fires it, polishes it with a handkerchief, and throws it on the floor. (This sort of offscreen or partially offscreen treatment allows the violence to be less explicit, a ploy that continues throughout the film.)

As the killer disappears, the camera tracks back to the left, revealing the boss’s body. The janitor enters, sees it, takes off his work clothes, and tosses them in the phone booth.

The scene ends with a pan left to follow the janitor as he hurriedly moves through the mess and leaves.

My frames were pulled from the Universal Cinema Classics DVD, a release which has since come out on Blu-ray. (Amazon still has the same edition on VHS!)

Love Me Tonight

So many of the early 1930s musicals were stagey. The review musicals were series of numbers without a connective narrative (convenient because they could be popular abroad without dubbing or subtitling) or backstage musicals where a “put on a show” premise also led to numbers on a stage. But with the growing freedom of the camera and editing, the musical could become something more.

Love Me Tonight feels like a wildly enthusiastic celebration of that new freedom. The story is a modern Ruritanian romance. A Parisian tailor, played by Maurice Chevalier, travels to a country chateau to collect money owed him by a client, who is a member of the aristocracy. While on his way, Maurice bumps into the debtor’s sister, Princess Jeanette, and falls in love with her without realizing who she is. Once at the chateau, he is mistaken for a Baron and proceeds to charm the Princess’ entire family and gain her love–until his lowly birth is discovered. Throughout, the dialogue is witty and the music and songs, by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart.

Much of the high spirits of the film arise from the fact that the songs are not sung by one or two people in a single locale. Instead, the music starts out in this limited way but passes along to other characters, spreading infectiously through a household or across a countryside. The process begins on a morning in Paris, as the city wakes up and goes to work. Gradually the rhythmic sounds of various activities build up to a symphony made of sound effects: a woman’s broom against a pavement or two cobblers’ hammers striking in counterpoint.

The first actual music when a man getting married that day picks up his formal outfit and Maurice sings about his work in “Isn’t It Romantic?” The groom goes out singing it, and it passes to a taxi-driver and then his fare–who happens to be a composer. Cut to a train, where he hums the music and writes it down (top of section), overheard by a group of soldiers; cut to a field where they march along singing it, and so on, until we reach the chateau and are introduced to the Princess, also bursting into “Isn’t It Romantic?”

Upon meeting Jeanette, Maurice woos her by singing “Mimi” to her. Here it’s a straightforward solo, though one that is filmed in an unusual fashion with Maurice singing and Jeanette reacting in shot/reverse shot directly into the camera.

Once at the chateau, Maurice apparently sings the infectious “Mimi” for the family and guests since there is a montage moving among them as they all cheerfully warble the song in their respective rooms. The same thing happens still later, when Maurice’s low birth is discovered; the song “The Son of a Gun Is Nothing but a Tailor,” similarly spreads throughout the building, including to the servants, who show a snobbery equal to that of their masters. Who can resist lyrics like those sung by a washerwoman?

Down upon my hand and knees/Washing out his BVDs/Is a job that hardly please me./If I had known I would have tore/The buttons off his panties for/The son of a gun is nothing but a tailor!

Overall one gets a sense that music and singing are irrepressible and ripple outward from the soloists to infect everyone within hearing distance.

Of course once Maurice has been thrown out, Jeanette decides to defy her family and races after his train on horseback. Mamoulian throws in some Soviet-style compositions as she heroically stands on the tracks and forces the train to stop.

Apart from its infectious style and music, Love Me Tonight has a wonderful cast, with Charles Butterworth as Jeanette’s wimpy but titled suitor, Charles Ruggles as the debtor son, Myna Loy as the man-hungry younger sister, and C. Aubrey Smith as the curmudgeonly father who becomes downright jolly under Maurice’s influence. Sheer entertainment.

Love Me Tonight is available from Kino Lorber on DVD or Blu-ray.

Hooray for the Rest of the World!

Vampyr

Two masters of cinema made vampire films a decade apart. I dealt with Murnau’s Nosferatu in the 1922 entry.

The two films could hardly be more different from each other. Murnau’s film was a plagiarized version of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula. He followed the original very loosely, cutting out most of the characters, including Van Helsing and hence the entire lengthy investigation process. Dreyer may well have known Murnau’s film, but it is hard to detect any influence or inspiration apart from the use of a book as exposition. The Universal version starring Bela Legosi was still in production when Dreyer finished shooting Vampyr. Instead, Dreyer drew even more loosely from the collection of horror-fantasy series short stories by Sheridan Le Fanu, published as In a Glass Darkly (1872).

Dreyer seems to have taken a few ideas from the stories, but does not use the narratives associated with those ideas. The notion of a female vampire is probably derived from one of the stories, “Carmilla,” though Le Fanu’s vampire is young and beautiful, while Dreyer’s is an elderly woman, Marguerite Chopin. The collection of stories is presented as having been case studies collected by a Dr. Hesselius, a researcher of the arcane. Allan Gray may be inspired by Hesselius, though he does no evident research and reacts in fear in most cases where he encounters anything strange and grotesque. Gray’s dream of being trapped in a coffin and carried off to be buried comes from “The Room in the Dragon Volant.”

On the whole, though, one of the most striking things about Vampyr is how little it adheres to the conventions of the vampire tale. It is not told as a collection of documents, as are Le Fanu’s stories (“Carmilla”is told in first person by Laura, the heroine and victim of the vampire) and Dracula (a collection of documentation by gathered by several characters). As in Nosferatu, a book is included to help present the “rules” of vampire stories, but the book is not written by Gray. It is given to him by the old Chatelain. The premises that vampires must travel in coffins full of dirt or will be killed if exposed to sunlight, so important in Nosferatu, are ignored here. Actually, the intention seems to be that Chopin is active mainly at night, but since the entire film was shot in murky daylight, it’s difficult to to tell night from day. Vampires also tend to be of noble birth, and we usually find out something about their family history. Chopin seems to be a local woman who somehow became a vampire.

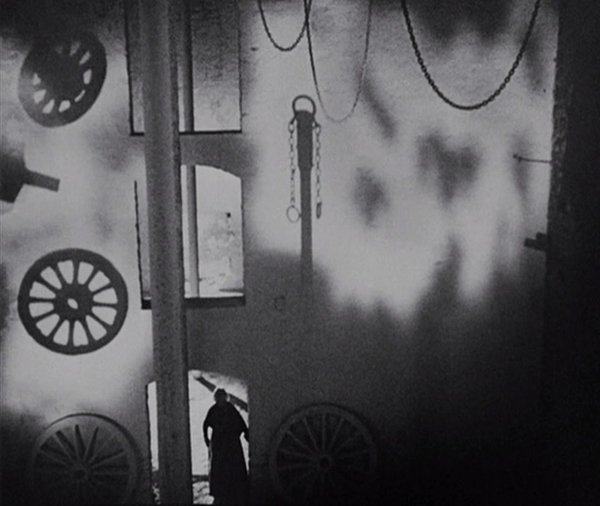

To create a creepy atmosphere, Dreyer has Gray wander about observing menacing, unnatural, or unexplained phenomena in the neighborhood of the village of Courtempierre. These are not phenomena conventional to vampire stories, so they seem as mysterious to us as to Gray. Much of what Gray observes is never explains. Gray sees numerous shadows and reflections of beings who are not visible. He follows the shadow of a peg-leg man until it finally rejoins the soldier who should be casting it. Most vampires live in crumbling Gothic castles, but Chopin seems to have made her headquarters in a dilapidated factory of some sort. (Dreyer chose a deserted plaster factory whose white walls would show off the shadows cast on them.) Her main minions, a sinister doctor and the one-legged military man apparently do whatever they do there, waiting to do her bidding. As the images above and on the right below show, Dreyer creates a mysterious air to the building through the circles and curves of large gears, wheels, and hanging chains.

Beyond such motifs, there are the actors’ unpredictable exits and entrances into the frame during camera movement and the eerie offscreen sounds that hint at something disturbing happening nearby. David has analyzed all this in detail in his book, The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer (out of print but available from second-hand book dealers).

For the ending, Dreyer draws upon the convention of a stake through the heart as the way to kill a vampire. It isn’t Gray that figures this out. A remarkably passive protagonist, he sits dreaming of being buried alive while the old servant, initially a minor character, reads the Chatelain’s book, gathers the needed equipment, and initiates the task of the staking of the vampire in her grave.

The 1998 restored version of the film is available from The Criterion Collection on DVD or Blu-ray, with a particularly good set of supplements. These include a visual essay by Danish expert Caspar Tybjerg that deals in more detail with the influences of previous vampire literature and films on Dreyer’s work; I have drawn upon it for some of the information above. Vampyr also streams on The Criterion Channel, accompanied by some of these supplements as well as a video essay by David, “Vampyr: The Genre Film as Experimental Film.”

Boudu Saved from Drowning

Jean Renoir entered this list in 1931 with La Chienne. Although a grim melodrama for the most part, the film provides put-upon accountant Maurice Legrand with a happy ending as he leaves home and becomes a jovial tramp.

Boudu, the self-centered, careless tramp at the center of this film, is presumably not Legrand, despite being played by the same actor, Michael Simon, and Boudu Saved from Drowning is not a sequel. It almost could be, but this time the genre is comedy.

The opening sets Boudu up as an unusual tramp. He is not begging, and when a little girl offers him a small bill, he asks what it is for. “To buy bread,” she replies. Soon Boudu does beg by opening a car door for a rich man, and when the man can’t find any money in his pockets to tip him, Boudu hands him the small bill “To buy bread” and walks away.

Unexpectedly, Boudu jumps into the river in a suicide attempt. Lestingois, a prosperous bookseller whose shop and apartment are across the street, witnesses this and rushes out to dive in and save Boudu. He succeeds, receiving praise from the onlookers as a bourgeois who would take this trouble for a mere tramp. Lestingois is fascinated and amused by this “perfect tramp” and takes him in, offering him dry clothes, food, and a sofa to sleep on for the night, much to the disgust of his wife.

Boudu’s antics delight Lestingois, who treats him somewhat like a pet dog (top of section). He also gives Boudu a lottery ticket, which predictably will become a vital plot device later on. The tramp, however, disrupts the routine of the household–in particular sleeping in a spot that prevents Lestingois from making his nightly visits to the maid Anne-Marie.

Boudu lingers on, seeing this cushy home as a good setup; he tries to fit in by shaving his bushy beard and trying to dress respectably. He is utterly uncouth, however, shining his shoes on the wife’s bedspread, and knocking things off shelves, and causing a flood by leaving water running in the kitchen. Lestingois ultimately gets fed up with him–but in the nick of time Boudu wins the lottery and the attitude of the household changes. Anne-Marie, who supposedly loves Lestingois, suddenly becomes engaged to him.

On the wedding day, however, as the happy couple are in a rowboat on the river, Boudu upsets the boat and floats away to resume his old life as a tramp.

Stylistically the film is distinctly Renoirian. He shot his exteriors in Paris streets and parks, seemingly concealing the camera in some cases. A telephoto lens captures Boudu wandering along the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine, with the other people presumably ignoring him as a real tramp.

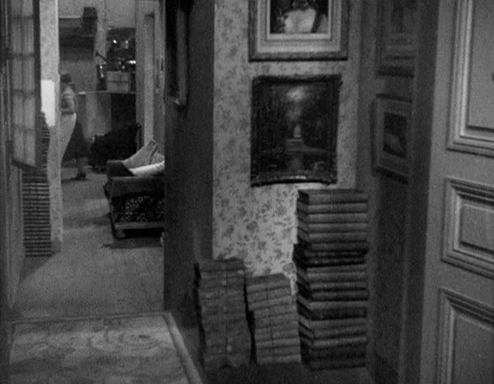

In a modest way, Renoir used the sort of roving camera movement that he would later develop into a major feature his late-1930s masterpieces. One scene starts with Lestingois and his wife eating a meal along with Boudu, seen from a distance down a hallway. As Anne Marie finishes serving, she exits left, and the camera moves left into the next room, where she is glimpsed walking toward the kitchen. It continues moving and stops briefly as Anna Marie enters the kitchen and puts down her tray. As she comes forward to the kitchen window, the camera tracks closer to the foreground window and stops, still at a distance as she talks with an unseen neighbor.

Boudu Saved from Drowning is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection and streams on The Criterion Channel (along with some supplements).

Wooden Crosses

Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses is this year’s masterpiece unknown to most modern viewers, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. I discovered the film through The Criterion Channel. David and I were relatively early in our “Observations on Film Art” series of supplements–early enough that the service was still called Filmstruck. In picking a film for a video essay, I thought it would be helpful to choose titles that were obscure but very much worth calling attention to.

One such film on the Criteron list was Wooden Crosses. I was dubious about it, since my only association with Bernard’s work was the 1924 historical epic, The Miracle of the Wolves, which I had seen back in my post-graduate days and found pretty turgid. Nevertheless, I gave Wooden Crosses a try and was bowled over by it. My video essay, “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses,” became number 16 and is available to subscribers.

In some ways Wooden Crosses is France’s great anti-war film of the early 1930s, following Hollywood’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Germany’s Westfront 1918, both of which were in my top ten for 1930. For me, it’s the best of the three.

The film begins with stock footage of Parisian crowds cheering the young men signing up to fight and marching off to war. Like The Big Parade, it introduces the war from well behind the lines, as new recruits arrive at a farmyard where the more experienced troops are billeted. The action takes place shortly after the Battle of the Marne in autumn of 1914; it was won by the French, but did not succeed in achieving ultimate victory. In Wooden Crosses, the experienced men scoff at the recruits for having arrived too late to experience any fighting.

Their optimistic assessment proves wrong, and the group is ordered to march to the front-line trenches. The result is an impressive sequence shot at night as the group goes through open areas, woods, and finally ends neck-deep in the trenches looking out across no man’s land in the darkness. As my video-essay title suggests, there is a considerable amount of night footage in the film. One point I make in that essay is that the epic footage in the film made an impression in Hollywood:

In 1935, the head of the newly merged 20th Century-Fox studio, Darryl Zanuck, bought the North American rights for Bernard’s film. He didn’t intend to release it theatrically. Instead, he realized that the spectacular battle footage was beyond anything that the studio could afford, and he wanted to reuse it.

The film it was to be used in was Howard Hawks’s The Road to Glory, released in 1936. Hawks, however, wasn’t just keen to use the battle footage. Like me, he seems to have admired the many night scenes. He said of Wooden Crosses that it had “Some fabulous film in it, marvelous scenes of great masses of people moving up to the front and through trenches—wonderful night stuff.”

The group of soldiers are quickly and marvelously characterized, notably by Charles Vanel as the group’s quiet, sensible Corporal and Gabriel Gabrio (Javert in Bernard’s Les Misérables) as the sarcastic, boastful Sulphart–a key source of comic relief in the film. Graduallynew volunteer Gilbert Demachy emerges as our main point-of-view character, though the others are kept prominent. There is a suspenseful series of scenes as they hear the sounds of German sappers tunneling below their dugout to lay mines. They are ordered to stay put, as there is plenty of time before the explosions, but as we discover, this is an example of a common motif in these films: the incompetence of the leadership.

One of the film’s most impressive aspects is the epic recreation of battle scenes. There’s no stock footage here, and there are shots over vast areas of no man’s land with explosions going off among the actors.

The climactic battle goes on and on–ten days, as repeated superimposed titles inform us–and conveys the relentlessness of the struggle that the group undergoes.

The battle ends in a long, tense scene, ironically set in a cemetery where many of the graves have been blasted open. These substitute for trenches as the men hunker down under German attack.

As with some of the other films on this year’s list, the cinematography of Wooden Crosses is extraordinary. It was shot by Jules Kruger, who had worked with major French Impressionist directors, notably Marcel L’Herbier on L’Argent and Abel Gance’s Napoléon, the latter of which no doubt gave him considerable experience with epic battle scenes. His most famous films after Wooden Crosses were La belle équipe and Pépé le Moko.

The Criterion Collection did a great service by releasing Wooden Crosses paired with Bernard’s Les Misérables in their Eclipse series. It also streams permanently on The Criterion Channel along with my video essay linked above. (New Year’s resolution: watch more Bernard films. I should give The Miracle of the Wolves another chance and set aside plenty of time to watch Les Misérables, a three-feature serial adaptation of the novel that clocks in at 281 minutes.)

I Was Born, But …

Yasujiro Ozu makes his third appearance in a row on these lists (see here and here for the first two). If I were to live to 102 and if I were still posting these lists, his last film would be on the 2052 list. That’s unlikely, but even so, he will probably be the director most represented on these lists as long as this series continues. I am still pondering whether to give him three spots on the 2023 list or just group his three masterpieces from that year as tied for a single spot.

I Was Born, But … was the first of Ozu’s silent films to become available in the West, and it is still probably the best known. So many of his early films are lost, but this may be the one where he achieved the perfect balance of humor and poignancy that characterizes so many of his best films.

Ozu is known for creating stories centered around the stages of life, often expressed as seasons in their titles, such as Late Spring‘s focusing on a daughter pushing the limits of marriageable age to care for her elderly father. His surviving early films often dealt with students or recent graduates struggling as “salarymen” in the job market of the Depression. In this film for the first time he shows the woes of the salaryman largely from the viewpoint of his children. Many of Ozu’s films are based on relations between parents and children young or grown. Those that dealt with young children were among his masterpieces: Passing Fancy, The Only Son, There Was a Father, Record of a Tenement Gentleman, and Ohayu.

The salaryman films deal with the difficulties of getting jobs, competing with colleagues, and surviving on meager wages. I Was Born, But … adds the problem of the subservience and even humiliation a salaryman sometimes undergoes and how it affects his family.

The story unfolds in parts that to some extent echo each other. Early in the film the two sons are bullied at school by the son of their father’s boss. They manage to defeat the bully and in a show of bravado boast that their father is the best in the world.

Later the family is invited to a gathering at the home of Yoshii’s boss, who shows some home movies of his employees showing off for the camera. These include Yoshii making faces and playing the fool, obviously at his boss’s insistence. The sons’ delight in seeing their father on the screen fades as they realize that their father has been humiliated and is not the great man they boasted about. Implicitly, Yoshii is being bullied as well but must submit in order to please his boss.

In an angry confrontation with their father, the sons accuse him of having proved himself not to be the man they had looked up to. The confrontation ends in their refusal to eat or speak to their parents. The parents admit to each other that their life is disappointing and not one they would wish for their children. The quarrel soon ends, with the boys accepting that their father is not the greatest.

As with That Night’s Wife (1930), Ozu is already using some of the techniques that would be part of his style for his entire career. For example, there is a transition between scenes that uses graphic values and objects in a series of images that do not behave like ordinary establishing shots.

I Was Born, But … is available in another DVD set in The Criterion Collection’s Eclipse series, “Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies.” The other two are the charming Tokyo Chorus and the wonderful Passing Fancy (which will definitely appear on next year’s top ten). Along with a slew of other Ozu films, it also streams on The Channel. Many of you know David’s book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema; it’s long out of print but available through open access on the Center for Japanese Studies Publications site (with the frames from the color films in color!).

Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World?

Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe, scripted by Bertolt Brecht, was a bold pro-Communist film made in the year before the Nazis swept into power.

Kuhle Wampe, named for the workers’ camp in which much of it is set, starts with the dire situation for the working class in Depression Germany. A typical family is singled out, with the son returning home after one of many fruitless searches for work (below). His parents blame him for his failure to find work in a society where unemployment is rampant. Their anger drives him to suicide. A neighbor woman remarks resignedly to the camera, “One fewer unemployed.”

The boy’s sister Anni becomes one of the main characters. Another is Fritz, her boyfriend, a leader in the labor protests in a local factory. When Anni becomes pregnant, the pair split up but eventually reunite when her family is evicted and moves into the tent city of the title, run by a Communist group (above). Communism is portrayed as a solution to the problems presented earlier. A lengthy sequence at a Communist youth sports festival emphasizes the happy life on offer by the Party. In the final scene, directed by Brecht himself, Anni and Fritz have an argument about the world’s financial dilemma with some middle-class passengers.

In 1933, Brecht fled the country, eventually ending up in Hollywood, and Dudow was expelled from Germany, only returning after the war to help found the Communist-run East German film industry.

As far as I can tell, the only DVDs or Blu-ray discs available in the US are imports and may not play on encoded machines. (It’s not even on YouTube!) For those with region-free players, the BFI’s release in either format seems to be best source.

Trouble in Paradise.

The ten best films of … 1929

Lucky Star

Kristin here:

As 2019 fades away, it’s time once more to look back ninety years at some great classics. This series started somewhat by accident, when we wanted to celebrate the pivotal year 1917. That was when the stylistics of the Classical Hollywood filmmaking system, which had been slowly explored for several years, finally clicked into place and became the norm in the American studios.

After that, our series became a regular and surprisingly popular feature. The point is partly just to have some fun and partly to call attention to great films that have remained obscure and/or difficult to see.

For past entries, see: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, and 1928.

After the riches of the 1920s silent film, 1929 stands out as an anomalous year. The transition to sound was under way internationally, but different countries proceeded at different paces. The new technology often was not amenable to maintaining the freedom of cinematographic and editorial style achieved during the height of the silent cinema. There are arguably not as many indisputable masterpieces from this year as from previous ones–but there are some.

Oddly enough, truly major films from this year seem to have suffered a great deal from a lack of access, both in distribution of prints and release of good (or even any) copies on home-video formats. In part I want to draw attention to the shocking neglect of some great movies.

The list is dominated by Hollywood and especially the USSR, for opposite reasons. The American studios were well into sound production, and some of the top directors found tactics for using the new technique in imaginative ways.

In the USSR, on the other hand, silents reigned. Moreover, the great directors were not lured away to work in America, as so many European filmmakers were. (For example, Murnau’s career was nearly over, and he released no films in 1929.) Thanks to them, the golden age of silent cinema continued on.

A great year for the Soviet Montage movement

The General Line (aka Old and New, dir. Sergei Eisenstein)

The General Line is probably the least of Eisenstein’s four silent features. The earlier films were all set before or on the very day of the 1917 Soviet Revolution, and they all have a vigor and a sense of political fervor that The General Line can’t quite match. Instead, it’s about policy, specifically the portion of the First Five-Year Plan devoted to the collectivization of private farms. Eisenstein adopts an odd tactic for dramatizing the need for such a drastic overhaul of life in the countryside. He presents a single protagonist for the first time, Marfa, a poor peasant working her land alone and without a horse for the plowing.

She becomes convinced that the answer to her and her neighbors’ plight is to create a cooperative dairy for the village. But throughout, Marfa has few allies and encounters opposition from both the local wealthy Kulaks and the poor peasants, who are portrayed as ignorant, greedy, and even violent in their determination to retain full ownership of their farms and livestock. Marfa is too weak to succeed without the support of the local government agronomist and a few like-minded farmers. The task of collectivization seems too overwhelmingly difficult to ever succeed.

In retrospect, we know about the systematic exile and execution of the Kulak class and the famines that resulted from government tactics over the coming decade. It is unpleasant to see Eisenstein, however unwittingly, providing propaganda for Stalinist policies.

Still, Eisenstein is Eisenstein, and The General Line is as formally daring as his earlier work. Apart from dramatic angles and rapid, jarring cutting, he experiments with extreme contrasts of elements within the frame by using depth compositions. These exploit wide-angle lenses and create impressive deep-focus images. In the shot above, Marfa is dwarfed by a pampered bull in the near foreground, and in a third plane beyond her we see the grotesquely fat Kulak lolling in the sun on his porch.

Other compositions create even greater contrasts. On the left, Eisenstein provides an image of bureaucratic indolence, official red-tape being a favorite (and apparently approved) satirical target for Soviet filmmakers. On the right frame, there’s a suggestion of the power of the collective’s new bull, who will sire a generation of calves.

Despite the grimness of the situation, Eisenstein manages to slip in an unusual amount of humor, and The General Line is quite entertaining.

The best DVD version I know of is the French one from Films sans frontiers, which is still available from Amazon France. The print in Flicker Alley’s “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film” is somewhat grayed out in comparison. Unfortunately this important set seems to be out of print. Flicker Alley rents The General Line online here.

New Babylon (dir. Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg)

This masterpiece by Kozintsev and Trauberg is all too little known. Information on the internet tends to come more often from musicologists, since Dmitri Shostakovich wrote the original musical accompaniment, rather than from film scholars. Many viewers have heard recordings of the score but not seen the film itself.

Kozintsev and Trauberg were the leading members of the FEKS (“Factory of the Eccentric Actor”) filmmaking group, based in Leningrad rather than Moscow. As the name suggests, the practitioners aimed not at realism, but at the grotesque, the comic, and the appeal of popular rather than high art.

New Babylon deals with the Paris Commune of 1871, a brief period when workers took over the French government. It was seen as a forerunner of the Soviet Revolution.

The title refers to a giant Parisian department store, which also seems to be in the business of putting on patriotic operettas about the current war with Germany. The store’s owner and patrons, as well as the performers in the operettas (see above) represent the bourgeoisie, while the workers who staff the store and create its products eventually rebel and run the doomed revolutionary government.

Again there is a heroine who represents the people, though she is unnamed, being known only as the shop assistant. She begins as a naive girl selling lacy clothing at the New Babylon and ends by becoming a militant revolutionary, standing atop a street barricade made up of the contents of the store–with the lace becoming bandages.

In keeping with its eccentric nature, the film mixes broad humor in the depiction of the bourgeoisie with grim tragedy as the defenders of the commune are shot in street fighting or tried and executed. The FEKS directors came from experimental theatre, but they also mastered the art of editing. New Babylon contains virtuoso sequences of crosscutting that sharpen the class struggle at the heart of the film.

New Babylon was restored in a joint venture by Dutch and German broadcasting channels and released, with the Shostakovich score, on DVD. There are Dutch and German versions, as Nieuw Babylon and Das neue Babylon respectively, which are out of print. We have the former. These retain the Russian intertitles, and, despite what the covers say, there are English and French optional subtitles as well as Dutch and German ones. (The booklet, however, is only in Dutch or German.) The quality is acceptable, but this film really needs a better restoration and Blu-ray release. It seems evident that the aspect ratio used in the current release crops the image to some extent.

Man with a Movie Camera (dir. Dziga Vertov)

I need say little about this film, since it has been widely seen, praised, and discussed. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, when many academic film scholars were obsessed with “self-reflexive,” or, less redundantly, “reflexive” films, Man with a Movie Camera was the great film. The result was, perhaps, that this admittedly very fine film was over-hyped. Nowadays it is as likely to be studied for the fact that Vertov’s wife, Elizaveta Svilova, created the very flashy Montage-style editing as it is for its reflexivity.

She is even seen doing so. At a number of points brief scenes of her examining, sorting, and splicing shots, which are subsequently seen in motion or in freeze-frames.

The film is a documentary, showing the filming, assemblage, and projection of a city symphony along the lines of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt, of two years earlier. Vertov’s version sort of a day in the life of Moscow (and glimpses of other cities), also beginning with the city waking up and going to work. Here, however, we see cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman (Vertov’s brother), with his camera and tripod traveling around the city, climbing factory smokestacks, filming from moving cars, and so on. Although many shots are straightforward documentary images, others use special effects, such as split-screen in the opening shot on the right below.

The film is available (as The Man with the Movie Camera) in Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray of Vertov’s main surviving silent and early-sound films.

Arsenal (dir. Aleksandr [or Ukrainian, Oleksandr] Dovzhenko)

Ukrainian director Dovzhenko came somewhat late to the Montage movement, contributing Arsenal in 1929 and Earth in 1930. When I was in graduate school, these were classics that everyone saw, mainly because 16mm prints were circulating. Now I wonder how many students and cinephiles see them. The standard print that has been released on DVD by a number of companies is quite poor: dark, low-contrast, cropped (though not as badly as the End of St. Petersburg version I complained about in our 1927 list).

Arsenal begins with the return of Ukrainian troops from World War I, with an emphasis on the decimation and impoverishment of the rural countryside with the loss and mutilation of many farmers. Only well into the film are we introduced to Timosha, the stalwart young representative of the proletariat who weaves through the film but does not really become a conventional protagonist.

Dovzhenko has come to be viewed as the poet of the Montage movement, and many of the scenes, especially early on, are more grimly lyrical than part of a straightforward causal chain of events. There is also a touch of what we would now call “magical realism,” as in two scenes where horses speak to their masters. Dovzhenko also employs a wide range of Montage techniques: canted shots (as above); very rapid, rhythmic cutting; jump cuts; compositions with very low horizon lines (below); and so on.

Given the importance of Arsenal, it is a shame that the old copies have not been replaced by high-quality, restored DVDs and Blu-rays. The images here are taken from the best release I know of, Image Entertainment’s old DVD. I’ve boosted the brightness and contrast, but the result is still not ideal, and the DVD is long out of print. (It’s worth seeking out, since it has a commentary track by our friend and colleague Vance Kepley.) The best version I have found is on YouTube, using the Film Museum Wien print. It’s not cropped and has a brighter, less contrasty image (on the right in the comparison above); the subtitles are in French.

Hollywood on the verge

I presume that some readers will expect to see the two official classics of early sound Hollywood, Ernst Lubitsch’s The Love Parade and Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause. Probably in the days of Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957) these were some of the rare films from the period that could be seen. They also were by major directors. Looking at them again, though, I don’t feel that they’re up there with the films below.

The Love Parade has the problem of dire sexual politics, the point being that while wives are naturally subservient to their husbands, a man put in the same position is entitled to be upset. That’s what happens when a court official, played by Maurice Chevalier, marries the queen of the mythical kingdom of Sylvania, played by Jeanette Macdonald in her screen debut. Moreover, we’re expected to find humor in a comic subsidiary plot where the official’s valet does a courtship duet with a maid, slapping her around a bit and apparently sexually abusing her in some fashion offscreen. Beyond that, though, there is a gaping plot hole that undermines the whole thing. The official is portrayed as nothing but a serial seducer, and yet when Sylvania is in financial difficulties, overnight he comes up with a brilliant plan to solve everything. In addition, after seemingly obsessed with sexual matters, he becomes bored with his marital position as the queen’s boy toy.

Applause displays rather clumsy camera movements that gave it cinematic flair in an era of clunky camera booths. But it simply seems to me not a very good film otherwise. Thunderbolt effortlessly runs rings around it.

Thunderbolt (dir. Josef von Sternberg)

Decades ago, when I taught the basic survey film-history course at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one could still rent Thunderbolt in 16mm. I showed it the week we studied the coming of sound. Returning to it now, I still think it’s the greatest early Hollywood talkie that I’ve seen. Here’s a film that came directly after von Sternberg’s string of silent masterpieces (not counting, unfortunately, the lost The Case of Lena Smith), and before one of his best-known works, The Blue Angel.

I’m baffled by the fact that it has never been available on DVD or Blu-ray. Fans share dreadful copies of the old VHS release or off-air recordings. Fortunately Turner Classic Movies aired it some years ago, and we have a watchable, if occasionally glitchy, homemade DVD.

The plot bears a vague resemblance to that of Underworld. A tough crime boss, nicknamed Thunderbolt (again played by George Bancroft), learns that his mistress is secretly seeing a young man and plans to marry him. The resemblance stops there, however. In an attempt to invade the young man’s apartment and murder him, Thunderbolt is finally caught and sentenced to death. Much of the rest of the film takes place in perhaps the strangest death-row prison ever portrayed on film.

Von Sternberg treats sound as a gift, not an obstacle. He cuts from cell to cell, all beautifully lit and composed, while offscreen a seemingly endless supply of singers and instrumentalists perform everything from “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” from a black soloist to a group of singers rendering barbershop-quartet style renditions like “Sweet Adeline” to a classical group that seems to be passing through. Sometimes we see the source of the music, sometimes we don’t. The music doesn’t seem to have much to do with the dramatic action but perhaps reflects the eccentricities of the warden–Tully Marshall chewing the scenery even more than usual.

Speaking of music, the film also includes an early scene with Thunderbolt and his mistress visiting a Harlem nightclub. The prolific black actress Theresa Harris, in her first known role, sings “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” Now that’s using early sound well.

Thunderbolt isn’t quite up to the level of Underworld or Docks of New York. Fay Wray and Richard Arlen make a blander couple than Evelyn Brent and Clive Brook in the former film. Still, it’s a major work in von Sternberg’s career. Let’s hope one of the DVD/Blu-ray companies finally makes it available.

Lucky Star (dir. Frank Borzage)

I well remember the astonishment and delight of the audience at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1990 when the previously lost Lucky Star was shown in that year’s Borzage retrospective. A print had recently been discovered at the Nederlands Filmmuseum (now the EYE Film Institute Nederlands).

Lucky Star was originally released in silent and part-talkie versions. The restored print was of the silent version, which was lucky indeed. Having seen how awkward and distracting the recently restored talking sequences in Paul Fejos’s Lonesome are, one can only cringe at the thought of similar scenes being inserted into Borzage’s lovely film.

Lucky Star again pairs Charles Farrell and Janet Gaynor, who had been firmly fixed as the ideal romantic couple by 7th Heaven and Street Angel.

There can be few, if any films of this period where the romantic leading man spends most of the narrative in a wheelchair. Tim has suffered a grievous injury fighting in World War I, and he and Mary, a young farm girl, fall in love. Mary’s mother insists that there’s no future with a disabled man and forces her to agree to marry a sleazy, bullying soldier. Such prejudice against a “cripple” is the main underlying theme of the film.

The development of the plot is surprisingly leisurely. The first half consists largely of Mary’s visits to Tim and his attempts to help her overcome some of the slovenliness and petty dishonesty stemming from her family’s extreme poverty. There is no real goal or conflict until the intrusion of the rival soldier about halfway through. The charm of the two characters and the actors playing them carry the action effortlessly.

As with 7th Heaven, the studio-built sets are remarkable, in this case representing entire houses set amid rolling woodlands. (See top.) The acting is splendid as well. Farrell in particular is quite convincing as a man who is paralyzed from the waist down. One remarkable shot lasting 2 minutes and 40 seconds has him struggling to leave his wheelchair and use crutches instead before finally falling into the foreground. The framing remains steady until a reframing downward at the end.

Lucky Star is one of the films included in the 2008 box, “Murnau, Borzage and Fox.” So far that invaluable set is still available. Otherwise one can find English and French DVDs of it as imports.

Hallelujah (dir. King Vidor)

For the first time, a mainstream director (Vidor was at the top of his game after enjoying a huge hit with The Big Parade in 1925) and MGM, one of the Majors of Hollywood, acknowledged that a gripping melodrama could be just as entertaining with an all-black cast as an all-white cast. That is, entertaining to those outside the deep South, where exhibitors refused to play the film, robbing it of its chance to become profitable.

Well established as a classic of both early sound cinema and African-American cinema, Hallelujah retains its entertaining quality. It is easy from a modern perspective to dismiss it as racist or dependent on stereotypes. But I think that put in the context of 1929, the film was as progressive as one could expect in the day.

Vidor had long cherished the project and gave up his salary to get a greenlight from MGM. The crew was racially mixed, including an assistant director, Harold Garrison, who was black. More importantly, the musical director, responsible for the many musical numbers, was Eva Jessye, the first widely successful black female choral conductor. A few years later she would participate in the premiere of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts, and alongside George Gershwin, she was musical director for Porgy and Bess.

Vidor shot the exteriors in the Memphis area, hiring local black preachers to consult on the religious scenes, including the river baptism. He accepted changes from his cast when they found their dialogue not ringing true. In short, he struggled to be as authentic as he could.

The casting was done with particular care. Zeke was originally to be played by Paul Robeson, the most respected black performer of the day, but he was unavailable. Instead Daniel L. Haynes, a notable stage actor, got the part through having understudied Robeson in the original production of Showboat. Haynes gives Zeke a buoyant appeal that maintains sympathy for him despite his vulnerability to temptation. Nina Mae McKinney, also coming from a stage career, did the same for the seductress Chick.

Hallelujah does not have the technical polish of a film like Thunderbolt, to a considerable extent because Vidor chose to shoot so much of it on location. The tracking shots during the opening number, “Oh, Cotton,” are certainly impressive for a 1929 film. There is also some impressive night shooting during Zeke’s chase after the escaping Chick.

Hallelujah is available on DVD from the Warner Brothers Archive Collection. Unfortunately the company has chosen to put a boilerplate warning at the beginning that essentially brands Hallelujah as a racist film:

The films you are about to see are a product of their time. They may reflect some of the prejudices that were common in American society, especially when it came to the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities. These depictions were wrong then and they are wrong today. These films are being presented as they were originally created, because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming these prejudices never existed. While the following certainly does not represent Warner Bros.’ opinion in today’s society, these images certainly do accurately reflect a part of our history that cannot and should not be ignored.

I don’t think this description fits Hallelujah, but it certainly sets the viewer up to interpret the film as merely a regrettable document of a dark period of US history. Warner Bros. demeans the work of the filmmakers, including the African-American ones. The actors seem to have been proud of their accomplishment, as well they should be.

Sound and silence

Blackmail (dir. Alfred Hitchcock)

Long ago, when I first saw Blackmail, I thought it was a pretty mediocre, clumsy film. Luckily I have learned quite a bit about cinema since then and can appreciate Hitchcock’s clever use of sound–beyond just the famous “knife … knife … KNIFE” scene.

There’s the sequence where the blackmailer saunters into the tobacco store run by the heroine’s parents. He starts forcing her and her policeman boyfriend to pamper him with an expensive cigar and a good English breakfast. As he eats, he whistles “The Best Things in Life Are Free,” successfully annoying the boyfriend even further (above).

Earlier in this scene, Hitchcock presents a leisurely long take as the blackmailer performs an elaborate examination of said expensive cigar. His byplay generates suspense in us about whether he will get away with his tactic, as well as suspense in the father as to just when he is going to pay for that cigar.

The scene works well enough in the silent version of the film, but the little sound effects and muttered comments of the blackmailer make it a combination of tension and humor that wouldn’t come across without the sound. It also makes a nice contrast with the extended scene of the heroine in the artist’s studio. There the veiled threat of his seduction attempt and her naive reactions create a genuine suspense with no humor.

In contrast, there are passages of fast cutting that help avoid the stagey quality of much early sound cinema. The opening police raid and the later chase after the blackmailer through the British Museum’s Egyptian rooms (see bottom) both employ this tactic effectively.

By the way, I always thought that the giant pharaonic head in the shot where the blackmailer slides down a chain must have been a process shot, with a smaller head blow up for effect. Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray disc of the film, though, shows the label under the head well enough to reveal that it’s a cast of one of the giant heads of Rameses II from his temple at Abu Simbel (see bottom). Casts aren’t much in favor in most museums these days, so it’s no longer on display.

Pandora’s Box (dir. G. W. Pabst)

Fritz Lang, who has appeared quite regularly on these lists, released only The Woman in the Moon, his least interesting 1920s film, in 1929. Expressionism was over. In contrast, Pabst filled in with perhaps his most popular film, Pandora’s Box.

The film derives from a pair of Expressionist plays, Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box, by Frank Wedekind. The first play had been filmed in 1923, as Erdgeist with Asta Nielsen as Lulu, and directed by Leopold Jessner in the Expressionist style. It survives but is among the most difficult Expressionist films to see. Pabst combined the second half of Earth Spirit and the entirety of Pandora’s Box for his version.

The play and film both depend on the central character being played by someone who can simultaneously Lulu’s conflicting traits: her vivacious joy in living, her strange mix of generosity and selfishness, her egalitarian attitude toward others, and her naive amorality. American star Louise Brooks was perfectly cast, as were the supporting roles, including veteran Expressionist actor Fritz Kortner as the wealthy publisher who is keeping Lulu as his mistress at the film’s beginning.

Although the source material would lend itself to Expressionist designs, Pabst went for a more modern, streamlined look, as in Lulu’s apartment (below) and the luxurious home of Dr. Schön.

Pandora’s Box was issued on DVD by The Criterion Collection but is now out of print. We can hope for a Blu-ray version.

Wild and tame surrealism

I’m dividing the tenth slot for two very different short films that were in their own ways experimental masterpieces that had a considerable lasting influence.

Un chien andalou (dir. Luis Buñuel)

Few if any trends in cinema have been so dominated by a single film. Surrealism was still a concentrated movement in the late 1920s, before it diffused out internationally to become a permanent option for experimental filmmaking. With Salvador Dalí as scriptwriter, Buñuel managed to create a loose narrative centered around displaying constant incongruous juxtapositions and inexplicable occurrences. It also aimed to offend, with the opening eye-slitting, the attempted rape, and the cavalier treatment of the clergy.

Un chien andalou, being short and in the public domain, is widely available online and on DVDs issued by small companies. I haven’t seen the BFI’s Blu-ray of L’Age d’or and Un chien andalou, but that would seem to be the best bet for quality.

The Skeleton Dance (dir. Walt Disney, animator Ub Iwerks)

The Skeleton Dance is a much tamer film than Un chien andalou, a humorous, entertaining treatment of the disturbing subject of death. (Nevertheless, it was reportedly banned in Denmark as being too macabre.) The subject was apparently suggested to Disney by composer Carl Stalling, whom the director approached to do music for two earlier Disney films. Stalling was interested in creating films based on musical themes, and The Skeleton Dance became the first of Disney’s “Silly Symphonies” series.

Stalling eventually moved on to Warner Bros.’s animation unit, where he composed the music for two series modeled on (and parodies of) the “Silly Symphonies”: the “Merry Melodies” and the “Looney Tunes.” Thus The Skeleton Dance helped inspire three of the great animated series of the 1930s and beyond.

The cartoon has only the loosest of plots, running (much as the “Night on Bald Mountain” episode in Fantasia would) through the eerie events of a night through to the calming effects of dawn. The opening features a frightened owl (below left) and a howling dog, but the main “characters” are four skeletons that leave their graves to dance and cavort. Iwerks showed off his virtuoso skill, with the complex figures of the skeletons moving in circles so that they crossed over each other, as in the circular dance in the image above. He also uses two basic techniques of animation, stretch and squash, to turn the rigid bones into lively, pliable figures (below right).

The Skeleton Dance is included in the “Walt Disney Treasures: Silly Symphonies” DVD set, now out of print.

Compilations of Carl Stalling’s brilliantly zany (and surrealistic) music for the “Merry Melodies” and “Looney Tunes” were released on CDs as “The Carl Stalling Project” Volume 1 and Volume 2. Remarkably and deservedly, these are still in print after many years. If you do not already own these, hasten to buy yourself a belated Christmas present.

Conclusion: Acknowledging two notable events

The year saw Buster Keaton, who has figured so prominently in these lists, make his final silent feature, Spite Marriage. A pleasant film, but one which does not reach the heights of his great comedies earlier in the decade. Second, the earliest surviving film of Yasujiro Ozu, Days of Youth, dates from 1929. Although not top-ten material, it already displays his unique style. Assuming we continue this annual list, it will not be long before Ozu begins appearing on it.

There’s an ongoing controversy over versions of New Babylon. Specialist Marek Pytel has noted that a number of scenes were cut from the film after its premiere, thus making the new version impossible to synchronize with Shostakovich’s score. The missing footage having been rediscovered, Pytel has constructed a new print and synced it with a piano version of the score. His website on the restoration of the original version is here. Ian McDonald has written an extensive series (in three parts, here, here, and here) analyzing in complex detail the evidence for and against Pytel’s claims. Among those is Pytel’s statement that Trauberg told him that the initial version is the one that he and Kozintsev would consider definitive, while at other times the director said that the edited version as released is the preferred one.

Pytel also has claimed that Kozintsev and Trauberg wanted the musical score to be recorded and added to the film; he argues that the film should be run at 24 fps and used that running time in the small number of live performances that have so far been the public’s only access to his version. The very low-resolution clip from Pytel’s version that he posted on Youtube, however, shows the action to be distinctly too fast at 24 fps. Perhaps Kozintsev and Trauberg would have accepted this faster action in exchange for a musical track, but it would have been quite distracting.

The standard version on the Dutch/German DVD seems to me to be running at the correct, slower speed, with the music reasonably well synced.

Whether or not the standard version is the preferred one, it has long been the one we have, and it is quite brilliant as it stands. Being episodic, it does not show signs of being incomplete, though obviously one would wish to see the extra footage in the Pytel version to be able to judge.

Our friend and colleague Ian Christie, noted historian of Russian and Soviet cinema, discusses the historical context of New Babylon in a short video essay.

Blackmail.

Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019

Hotel by the River (2018).

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival is all too rapidly approaching its end, so it’s time for a summary of some of the highlights so far.

New films from around the world

We have not quite managed to catch up with all the recent films by Korean director Hong Sang-soo, but we took a step closer with Hotel by the River. It’s an impressive film, in part by virtue of its setting. The Hotel Heimat stands beside a river which is covered in ice and snow. Even the further shore with its mountains, is reduced to shades of light gray in the misty, cold light. All of this is enhanced by the black-and-white cinematography that creates a background against which the characters and the small trees create simple, austere compositions.

The story involves an aging poet who somehow senses that he is going to die soon and settles in at the hotel to wait for death. His two sons, one a well-known art-film director with a creative block and the other secretly divorced, come to visit. A young woman who has recently broken up with her married lover is visited by a sympathetic character who may be her sister, cousin, or friend. They encounter the poet by the river, and he compliments them effusively for adding to the beauty of the scene. Conversations about life ensue. The women take naps, the men bicker. Sang-soo’s typical parallels and repetitions unfold. It’s a lovely film.

Yomeddine, an Egyptian film, created something of a stir last year when it was shown in competition at Cannes. It was a surprising choice, given that it is writer-director A. B. Shawky’s first feature.

It’s also a modest, low-budget film, and like so many such films made in countries with limited production, it’s a road movie. No need to build sets or use complex lighting. The two central characters are Beshay, dropped off as a small child at a leper colony by his father, and Obama, a young orphan who knows nothing of his birth parents. Coincidentally, they both come from Qena, a city north of Luxor on the great Qena Bend of the Nile. Longing for links to their origins, the two set out there. At first they ride in the donkey cart that Beshay uses in his work as a garbage-picker, but later, when the donkey dies, they travel on foot and occasionally by train, riding without benefit of tickets.

There’s no indication where the orphanage and leper colony are and thus how long a trek the two face. I’m pretty familiar with the Nile, but they follow the large canals and train tracks that run parallel to the river on both banks. The villages along their route look pretty much alike. Shortly into the trip, however, Shawky suddenly confronts us with the Meidum pyramid (above), which acts as a handy landmark to reveal that the pair have a long way to go. It’s Shawky’s only display of an ancient site. Beshay and Obama have no idea what it is, but they explore it and spend the night in its small chapel.

Yomeddine is a likeable film blending humor, pathos, and a little suspense as it follows the pair on their quest. It’s also a plea for tolerance. Beshay’s deformities scare off those who wrongly think that leprosy is contagious (with treatment it is not), and Obama is denigrated by his classmates as “the Nubian,” for his relatively dark skin. Their sometimes prickly odd-couple friendship is a demonstration of how people of various backgrounds, including those on the margins of society, can get along. That, I suspect, is what led Cannes programmers to include it in the competition.

Overall it’s a well-made, entertaining film, perhaps an indication that we shall see more from Beshay on the festival circuit in the future.

[April 19: Yomeddine won the Audience Favorite Narrative Feature at the Wisconsin Film Festival.]

Ralph and Venellope Back in 3D

Phil Johnston with Ben Reiser, Senior Programmer, Wisconsin Film Festival.

UW–Madison grad Phil Johnston was a key participant in the festival. Not only did he program one of his favorites, Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), but he also visited a class and ran a public event around Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Breaks the Internet. Phil was a writer on both entries and co-director on the second, while also providing screenplays for Zootopia (2016) and Cedar Rapids (2011). We’re very proud of him, and we were happy to welcome him back home.

I love both the Wreck-It Ralph films, but I don’t like to go to hit movies early in their runs. We usually wait a few weeks till the crowds die down. As I recently pointed out, though, that means risking no longer having the option of seeing a 3D film in that format. So it happened with both Ralph Breaks the Internet and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Fortunately for us, the UW Cinematheque added permanent 3D capacity to its projection options, so Ralph 2 was shown in that format. The 3D much enhances the sense of being surrounded by the myriad “websites” in the scenes showing general views of “the internet,” as well as by the vehicles and netizens that flash past in their travels.

Both Ralph films display a non-stop inventiveness, and I agree with Peter Debruge’s comment that Wreck-It-Ralph “ranks among the studio’s very best toons.” The sequel is, if anything, even better. The scene in which Venellope von Schweetz confronts the full panoply of Disney princesses and tries to prove herself one of them became a classic before the film was even released.

The notion of Venellope moving from the sickly sweet “Sugar Rush” arcade game to the wildly dangerous online “Slaughter Race” (see bottom) is a great concept to begin with, and her rendition of her “Disney princess” song, “A Place Called Slaughter Race” is hilarious. The film was robbed, in my opinion, when her song didn’t get nominated for a Oscar.

The film has jokes to burn, as in the clever puns on the signs that flash in the internet and game scenes. I look forward to being able to freeze-frame the images to catch the many I missed. Unfortunately the Blu-ray release will not be in 3D. Disney has been phasing out releasing its 3D films in that format ever since Frozen, but you could for a time order such discs from abroad. (Other studios are following suit, and our 3D copy of Into the Spider-Verse is wending its way from Italy as I type.) I am told that the only 3D Ralph will be the Japanese version, at something like $80. Fortunately, it looks great in 2D as well, but I’m glad to have seen it on the big screen in 3D once.

So old they’re new again

Jivaro (1954).

Recent restorations have become a increasingly important component of our festival’s wide variety of offerings. Selections from the previous year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna are now regularly programmed, and we had visiting curators presenting their new projects. (For a brief rundown of the Bologna offerings this year, see here.)

Another film taking advantage of the Cinematheque’s new 3D capacity was Jivaro, a jungle-adventure film of the type more popular in the 1950s and 1960s than it is now. Having seen a such films when growing up, I can say that Jivaro is better than many of its type.

It was made late in the brief early 1950s vogue for 3D, so late in fact that the studio decided to release it only in 2D. One attraction of its screening at the WFF was the fact that it was screening publicly for the first time ever in its intended format. Bob Furmanek, 3D devotee and expert, introduced the film and took questions afterward; he has been a driving force in the restoration of this and many other 3D films. (His immensely valuable site is here.) Below Bob shows one of the polarizing filters used in projection booths.

The film was highly enjoyable, partly for the 3D (shrunken heads thrust into the lens and spears coming at us!) and partly for the comfortable familiarity of its genre tropes. There’s the genial South American trader who has gained the respect of the locals, the seemingly deluded adventurer with a map to a lost treasure who turns out to be right, the gorgeous woman who shows up dressed in tight blouse, skirt, and high heels, the beautiful local girl in hopeless love with a white man, and so on. (The beautiful girl was an early role for Rita Moreno, who labored as an all-purpose-ethnic bit player for years before West Side Story made her a star.) Leads Fernando Lamas and Rhonda Fleming supply beefcake and cheesecake, respectively, at regular intervals. Lamas (as you can see above) barely buttoned his shirt across the whole film. It’s hot in jungles.

For those with 3D TVs, Jivaro is already out on Blu-ray.

The Museum of Modern Art has followed up its restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) with one of Forbidden Paradise (1924). Both were shown at this year’s festival. We saw Rosita at the 2017 Venice International Film Festival and wrote about it then. In preparing my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005; available free as a PDF here), I saw an incomplete copy of one preserved in the Czech film archive–a key element in constructing this new version. Naturally I was eager to see the new scenes and much-improved visual quality of the MOMA restoration. Archivist Katie Trainor was present to explain the process, which yielded a version that is about 90% the length of the original.

Of all Lubitsch’s Hollywood films, this is the one that most looks back to his German features of the late 1910s and early 1920s. For one thing, his frequent star of that period, Pola Negri, was by now in Hollywood and worked here with him again here, their sole Hollywood collaboration. She stars in a highly fanciful tale of Catherine the Great, and the quasi-Expressionistic sets present an appropriate version of historical style. The set in the frame above (taken from a 35mm print, not the restored version) is my favorite, with its lugubrious creatures crouched atop the wall. Grotesque sphinxes? (The designer might have been thinking of the the two beautiful granite sphinxes of Amenhotep III that sit to this day by the Neva River in front of the Academy of Arts, though they were brought to Russia decades after Catherine’s reign.) Or just elaborate gargoyles?

The plot centers around a brief affair between a young officer (Rod La Rocque) and the licentious Catherine. A brief attempt at revolution flares up. All this is deftly dealt with by the Lord Chamberlain, played by Adolf Menjou, hamming it up with eye-rolls and knowing chuckles.

It’s not first-rate Lubitsch, largely lacking the lightness that one associates with the director, and which he had already achieved in his second Hollywood film, The Marriage Circle (1924). But it’s a pleasant entertainment, and the set and costume designs are visually engaging–especially in this excellent new restoration.

David watched None Shall Escape (1944) for his book on 1940s Hollywood, but I was unfamiliar with it until its restored version was shown here as one of the Il Cinema Ritrovato contributions. The film was originally made by Columbia and was presented at our fest in a 4K restoration from Sony Pictures Entertainment, the parent company of Columbia. Rita Belda, SPE’s Vice President of asset management, was here to explain the complicated process. She summarizes it here as well.

The film had been carefully preserved, probably because of its historical importance as a unique fictional depiction of Nazi atrocities. The original negative and three preservation positives survived. These had the usual scratches and tears, as evidenced in the first comparison image above. A significant challenge, however, was that the prints had all been lacquered in a misguided attempt to preserve them. The result was staining throughout, evident in both comparison images. Digital removal allowed for a stunningly clear image throughout the finished version.