The sirens’ song for Oscar

Sunday | February 15, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

The Lego Movie.

Another guest blog this week, this time from Jeff Smith, our colleague in the department here at UW–Madison. Jeff is one of America’s experts on movie music and sound technology. He contributed an entry on Atmos last year. He has written many articles on film sound, along with two books: The Sounds of Commerce and Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. He’s also our collaborator on the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction.

‘Tis the season for Oscar buzz, and the media glut of award prognostications is already upon us. Most of the attention will go to the above-the-line talent who’ve received nominations (actors, directors, and screenwriters). The craft categories tend to get much less scrutiny, but the work of cinematographers, editors, and composers plays an equally important role in making their films award-worthy.

Today I offer some observations about this year’s nominees in the music categories: Best Original Score and Best Original Song. By using the nominees as examples, I hope to illuminate some of the ways that music continues to contribute to cinema’s narrative functions and its emotional impact on viewers. I’ll also offer my predictions for who will win at the end of each section.

Best Original Score

Even before this year’s nominees were announced, one of 2014’s most distinctive and innovative film scores was declared ineligible by the Academy. Antonio Sanchez’s driving percussion score for Birdman was disqualified under Rule 15, which states that scores “diluted by the use of tracked themes or other pre-existing music, diminished in impact by the predominant use of songs, or assembled from the music of more than one composer shall not be eligible.” Apparently, in the view of the Academy’s music branch, Birdman’s use of substantial excerpts of concert music by Mahler, Tchaikovsky, Ravel, and John Adams weakened the impact of Sanchez’s score. That explanation, though, probably doesn’t pass the eyeball (or eardrum) test of anyone who has seen Alejandro González Iñárritu’s film. Sanchez’s drum work adds verve and energy to several of the director’s elaborately choreographed (and seamlessly stitched together) long takes.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’s electronic score for Gone Girl was also a notable snub, especially since their bold, pathfinding music for The Social Network took home the top prize just four years ago. The fact that both of these scores failed to secure nominations may be a sign that the Academy’s music branch is returning to the verities of good old-fashioned melody and harmony as the basic tools in the composer’s kit.

That being said, the absence of Sanchez, Reznor, and Ross from the list of nominees doesn’t mean that the remaining scores are dull or unadventurous. Quite the contrary. Several of them push film composition in new and exciting directions. Their scores fulfill traditional functions but employ innovative scoring techniques and orchestrations.

Old sounds, new sounds

Take, for instance, Gary Yershon’s score for Mike Leigh’s biopic, Mr. Turner. Bypassing the conventions of orchestral writing for film, Yershon composed for a chamber-sized ensemble. Some cues combine a saxophone quartet with a string quintet, a musical choice that seems deliberately anachronistic. (As Yerson himself says in the soundtrack’s liner notes, Adolph Saxe’s invention wasn’t even patented until 1846, just a few years before Turner’s death.) Other cues add flute, clarinet, harp, tuba, or timpani to the mix. But these embellishments simply add color to the basic sound of Yershon’s twin string and saxophone ensembles.

Yershon says he was attracted to the saxophone due to its ability to glissando – that is, bend pitch from one note to another. Yershon certainly exploits this element of the instrument’s sound by building his melodies from long sustained notes that slowly take on serpentine shapes. Saxophone glissandi have an almost iconic function in the idioms of jazz and pop music . (Think of the opening phrase of Wham’s “Careless Whisper.”) In this case, though, the technique gives Yershon’s score a minimalist, modernist edge.

Yershon’s inclusion of a saxophone quartet departs from two norms: the period music of Turner’s time and the symphonic orchestrations that have characterized biopics for decades. The saxophone was never a major component of the Hollywood sound crafted during the studio era. Composers like Max Steiner and Victor Young occasionally included saxophones in their arrangements of music played onscreen by dance bands, but for the most part, their wind arrangements were for some combination of flutes, oboe, English horn, clarinets, and bassoons.

Is Yershon’s score inappropriate on historical grounds? I don’t think so. By modernizing the sound of Leigh’s period biopic, Yershon’s score adds a contemporary resonance, perhaps encouraging viewers to see parallels between Turner’s painting and the work of modern-day artists. Indeed, as Guy Lodge noted in his Hitfix review of the film, “It’s tempting, even, to view the film as biopic-as-self-portrait, revealing shades of one life through another. Leigh has a reputation for prickliness and resistance to self-explication; perhaps it’s not surprising that he’s long been fascinated by Turner’s allegedly gruff, taciturn genius.”

Yershon’s use of contemporary instruments may not in itself suggest those historical parallels. Indeed, most viewers probably have no idea when the saxophone was invented. But it certainly invites us to think about Leigh and Yershon’s reasons for opting for such a modern sound. And with its smaller instrumental forces, Yershon’s score resists some of the sweeping emotionalism that is found in other examples of the genre.

Zimmer pulls out all the stops

Hans Zimmer’s nomination for Interstellar is the tenth of his long and distinguished career. With all apologies to John Williams, Zimmer is arguably Hollywood’s leading film composer and his work is emblematic of a larger industry turn toward emphasizing musical tone and texture rather than big memorable themes. Zimmer’s score for Interstellar is no exception to this rule. In this case, though, much of the tone and texture is provided by the four-manual Harrison & Harrison pipe organ found in London’s Temple Church.

Director Christopher Nolan says that he liked the sound of the church organ as something that added an element of religiosity to Interstellar. But the organ contributes other things as well. For one thing, the organ’s booming bass register adds mass and heft not only to the music, but also to the astronomical bodies shown onscreen. The sheer size of these lower frequencies enhances the sense of scale in Nolan’s imagery. Thanks to the organ’s huge pitch range, the instrument’s upper register provides the quieter, swirling arpeggios needed to suggest the story’s filial bonds between father and daughter. At the same time, the instrument’s big, fat bottom end adds the musical bombast needed to convey the film’s epic visions of distant planets, wormholes, and alternate dimensions.

More important, despite the church organ’s strong association with sacred and liturgical music, Zimmer’s score never sounds like a Bach toccata. Rather, due to its repetitive, but intricate arpeggiations and simple, but affecting harmonic structures, Interstellar’s music has the kind of trippy, drone-ish, psychedelic feel that suggests both Terry Riley and Iron Butterfly. Zimmer’s score does not contain anything that is an obvious quote from the music of Stanley Kubrick’s “thinking man’s” sci-fi classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Yet, in its own way, Zimmer’s music recalls the period where such films were being produced, indeed the very kind of film that Nolan self-consciously tried to recreate.

In developing the score for Interstellar, Nolan and Zimmer also departed from the norms for director-composer collaborations. Most composers begin their work at a fairly late stage in the filmmaking process. In some cases, they may work from a completed script. In most cases, though, a composer starts with a rough cut of the film, making his or her contribution felt only during post-production.

In contrast, Nolan acknowledged that he has gradually been bringing Zimmer into his production at earlier and earlier stages. Nolan dislikes the practice of temp tracking, a technique that involves slugging in preexisting music that temporarily serves as a guide to the production team during the editing process. Says Nolan, “To me music has to be a fundamental ingredient, not a condiment to be sprinkled onto the finished meal.”

For Interstellar, Nolan asked to meet with Zimmer well before production began. As Nolan recounts in the liner notes to the soundtrack, he gave the composer an envelope containing a one-page summary of the fable that sat at the heart of the story. The description did not contain any details of the film’s genre or plot. Rather the summary simply laid out the narrative’s emotional core. Zimmer then took the summary and retired to his studio to start composing. Several hours later, Zimmer brought back a CD that contained about three or four minutes of music. Nolan listened to the new piece: a simple piano melody that nonetheless captured the feeling of what the director says he was “already struggling with on the page.”

When Nolan began shooting, he frequently listened to Zimmer’s simple piano piece, which functioned as a kind of “emotional anchor” for the film. Eventually, Zimmer returned to the studio and created the huge musical canvas that captures Interstellar’s heady exploration of space and time. Underneath it all, though, is the humble melody Zimmer wrote prior to production, the modest edifice upon which the rest of the score is built.

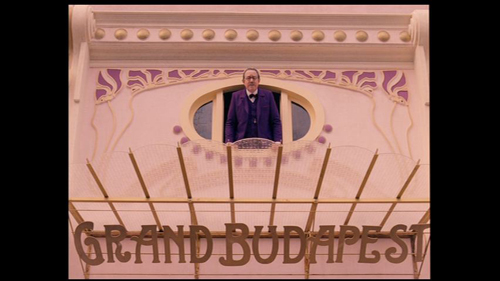

More songs about buildings and food service

Like Zimmer, Alexandre Desplat has several previous nominations to his credit, including those for the scores of Best Picture winners The King’s Speech and Argo. Unlike Zimmer, though, Desplat has yet to win. Among Hollywood’s current A-list composers, Desplat has shown extraordinary versatility. He’s at home writing for foreign art films, American indies, animation, and studio genre pictures. Desplat’s score for Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel is the third he has done for the director, following earlier collaborations on The Fantastic Mr. Fox and Moonrise Kingdom.

Here again, Desplat’s score for The Grand Budapest Hotel departs from established norms of Hollywood orchestration. Although he uses a slightly smaller version of the wind and brass sections usually found in older Hollywood film scores, he avoids the normal violins, violas and cellos. Instead he opts for a string section comprised of balalaikas, cimbaloms, zithers, mandolin, and acoustic guitar. This choice is intended to reflect the vaguely Mitteleuropean setting of the film. Just as the story is loosely inspired by the writings of Austrian novelist Stefan Zweig, the music reflects the social and geographical milieu of Zweig and his characters during the 1920s and 1930s. Eastern European and Russian folk melodies inspired much of Desplat’s. This combination of instrumentation and idiom creates a harmonic and timbral palette that proves to be enormously flexible in the composer’s hands, enabling him to add classical, modern, and jazz touches wherever they are needed.

Although Desplat employs unusual orchestration in The Grand Budapest Hotel, his score is fairly traditional in other ways. There are leitmotifs for several of the main characters, such as M. Gustave, Zero, Madame D., and Ludwig. An eight-measure theme is also linked to situations of adventure or danger. These themes and motifs tighten up the film’s structure. Such cues for patterning are particularly important when one considers The Grand Budapest Hotel’s “Chinese box” or “Russian doll” narrative construction, which nests stories inside stories.

Desplat’s score also captures the film’s dark yet whimsical tone. In interviews, the composer acknowledges that Bernard Herrmann and Carl Stalling were important influences on his work. At first blush, Herrmann, who composed several iconic scores for Alfred Hitchcock, and Stalling, who wrote crazy, almost manic music for Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons, would seem to occupy opposite corners of the universe. It’s to Desplat’s credit, though, that he is able to blend these diverse influences in a manner that is perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s imaginary “snow-globe” world. Indeed, the cue for the scene where Gustave is hanging from a cliff features harmony that would not be out place in Herrmann’s score for North by Northwest, an obvious inspiration.

But the mood is much lighter and airier in Anderson’s cliffhanger, partly because of the tenor established by Desplat’s music.

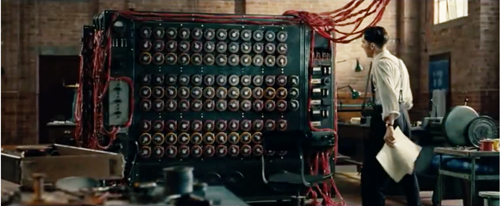

Scoring the Beautiful Minds of Cambridge

Ironically, Desplat’s chief competition may come from himself. Besides The Grand Budapest Hotel, Desplat also received a nomination for the fact-based espionage thriller, The Imitation Game. It was the fourth time in the last fifteen years that a single composer received two Oscar nominations for Best Original Score. And like the other nominees discussed here, Desplat developed an unusual compositional technique for the film, allowing for an element of randomness to determine his score’s final musical shape.

Whereas Sanchez deviated from compositional norms by improvising beats for Birdman, Desplat’s score for The Imitation Game pushes the envelope by featuring three computerized pianos, which sometimes play random patterns of preprogrammed music. According to the composer, the pianos’ fast, complex combinations not only underscore the urgency of the Bletchley Park team’s search for a solution to the Nazis’ Enigma code, but they also function as an musical correlative of cryptanalyst Alan Turing’s thought processes. As director Morton Tyldum put it, he wanted the music to seem subjective, as though it was conveying the mental operations inside the head of an awkward, but brilliant mathematician.

Desplat’s use of rapid scales and arpeggios to represent Turing’s genius actually recalls Philip Glass’ score for Errol Morris’s documentary about Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time. To be fair, Glass’ compositional style has employed these kinds of musical textures in many other types of cinematic contexts. Glass’s work not only appears in other Morris films, but also in biopics about Japanese writer Yukio Mishima and the Dalai Lama, and even in horror films and dramas, such as Candyman and The Hours. Given the constancy of his compositional proclivities, it is perhaps easy to make too much of Glass’s ability to depict the depth and brilliance of Hawking’s intellect. Yet there is little question that Glass’s music adds both a sense of mystery and majesty to Morris’s imagery, which itself explores such imponderables as the nature of time and the origins of the universe.

Because of this precedent, it is perhaps doubly striking that composer Johann Johannson took such a different tack in his music for the Hawking biopic, The Theory of Everything. With long sustained string lines and simple piano melodies, Johannson aims for a soft lyricism that is intended to add both pathos and subdued passion to the film’s depiction of Hawking’s relationship with his wife Jane. Since the film is based on Jane’s account of their marriage, it is probably not surprising that Johannson’s score plays her point of view even more than it does that of its putative subject. As the composer explains, the “heart of the film is the love story: Stephen and Jane, Jane and Jonathan. That’s really what the music needed to capture.” Thanks to Johannson’s use of harpsichord, celeste, harp, and guitar, the tone colors of the music remain light, making his score for The Theory of Everything a modern counterpart to the work of the Georges Delerue.

Prediction

All five nominees are quite worthy of the award for Best Original Score. But, if I had the opportunity vote, I would probably cast it for The Grand Budapest Hotel. Not only is Desplat’s score perfectly attuned to Wes Anderson’s distinctive style, but it would be nice to see the composer recognized for the overall quality of his oeuvre. Desplat’s fans, though, probably split their votes between The Grand Budapest Hotel and The Imitation Game, thereby increasing the chances that he’ll once again go home empty-handed.

In underlining The Theory of Everything’s romance plotline, Johansson’s score is perhaps the most traditional among the five nominees. I don’t believe, though, that its adherence to longstanding film score conventions will hurt it on Oscar night. Johansson’s sweet lyricism already carried the day at the Golden Globes, an award that has correctly predicted the eventual Oscar winner four out of the last five years. Although there could be an upset in this category, I expect we’ll see Johannson triumphantly hoist the little gold man over his head come Sunday night.

Best Original Song

If recent award ceremonies are any indication, this is a category that has fallen a bit on hard times. At least this year, there are five legitimate nominees. Last year one of the nominees was disqualified, and in 2012 and 2011, the category fielded only two and four nominees respectively.

One potential reason for the paucity of original songs may be the previously mentioned turn toward tone and texture in contemporary scoring practice. In the old days, many of the best-remembered and best-loved songs from the movies were crafted from themes specifically composed for the score. This was the case with tunes like Alfred Newman and Frank Loesser’s “Moon of Manakoora” from The Hurricane, Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s “Days of Wine and Roses,” or even James Horner and Will Jennings’s “My Heart Will Go On” from Titanic. Since current film composers are turning away from big themes, it seems there is less opportunity to adapt a musical motif into something that works as a theme song. (Of course, there are occasional exceptions. In 2013, Adele and Paul Epworth took home the Oscar for Skyfall, updating the established formula for making Bond theme songs.)

This year’s nominees also lack anything resembling last year’s heavyweight battle between Frozen’s “Let It Go” and Despicable Me 2’s “Happy.” All of the nominees seem quite worthy. None of them, though, has created the kind of cultural ubiquity enjoyed by Idina Menzel’s and Pharrell Williams’s chart-topping singles.

Two of the nominees have the misfortune of appearing in little seen films: Beyond the Lights and Glen Campbell: I’m Not Me. Diane Warren is one of the industry’s top songwriters and her “Grateful” is featured in the former of the two films. Warren also is a seven-time Oscar nominee, and although I believe her time at the podium will eventually come, it seems unlikely this year. Glen Campbell and Julian Raymond’s “I’m Not Gonna Miss You” is a moving ballad, made all the more poignant due to the singer’s ongoing struggles with Alzheimer’s disease. Campbell’s battle, which is the subject of James Keach’s documentary about the singer’s farewell tour, makes the song a counterpart to other epitaph numbers, such as Johnny Cash’s cover of “Hurt” or Warren Zevon’s “Keep Me in Your Heart.”

The third nominee is “Lost Stars” from Begin Again, director John Carney’s belated follow-up to his earlier indie sleeper, Once. “Lost Stars” was written by two members of the nineties band the New Radicals: Gregg Alexander and Danielle Brisebois. The latter has come a long way since her days as a seventies child star appearing in Broadway’s Annie and television’s All in the Family. Starting in the 1990s, Brisebois remade herself as a successful songwriter and producer, penning tracks for Donna Summer, Natasha Bedingfield, Kelly Clarkson, and a host of other top female performers.

“Lost Stars” is heard several times in Begin Again. The first time Gretta (Keira Knightley) performs it in a spare singer-songwriter arrangement featuring acoustic guitar, piano, and strings. It underscores a flashback of Gretta’s arrival in New York with her skeezy rock-star boyfriend Dave (Maroon 5’s Adam Levine). Later, we hear it as a track on Dave’s CD. Here he gives it an up-tempo stadium-pop sheen. Near the film’s end Dave again performs “Lost Stars,” this time as an arena-rock power ballad.

It is unusual to hear an Oscar-nominated song played in such wildly different styles, and even more unusual for one of those versions to be served up in a manner intended to seem excessive and distasteful. Tellingly, the end credits list Dave’s rendering of the song on CD as “Lost Stars (Overproduced Version).” The contrast between them, though, provides important character motivation for the film’s resolution. Dave’s indifference to Gretta’s creative vision of the song shows that he is ill suited to be her romantic partner. It also reveals producer Dan as a much more kindred spirit for Gretta’s professional ambitions. She gets to keep her coffeehouse, folkie purity even as her coffers are filled by the filthy lucre earned from sales of the soulless version featured on Dave’s major-label CD.

Interestingly, on Oscar night, Adam Levine will sing “Lost Stars” as part of the broadcast. If the producers wanted to stay true to the spirit of “Begin Again,” they might have opted for Keira Knightley to perform the song. Yet the fact that Levine was the first performer announced suggests that his star power was simply too much of a draw. Despite the film’s critical view of Dave’s talent, sales of Levine’s version of the song appear to have outpaced Knightley’s. Begin Again may be cynical about the music’s industry’s overinvestment in mainstream tastes, but Levine’s “overproduced” version of “Lost Stars” has done a great deal to give the film much-needed media exposure.

The fourth nominee, The LEGO Movie’s “Everything is Awesome!!!”, arguably displays an even more mind-bending degree of complexity in its relation to the popular music marketplace. The song appears quite early on in the film introducing us to a “utopian” animated world where citizens happily play their part in serving Lord Business. As my colleague Jeremy Morris pointed out in a campus symposium on song “hooks,” “Everything is Awesome!!!” is a tongue-in-cheek anthem to teamwork, conformity, and the dominant ideologies regarding labor and consumerism. Think of it as Adorno and Horkheimer for the toddler set, or better yet, as part of the Frankfurt Pre-School.

As an element of internal critique within The LEGO Movie, “Everything is Awesome!!!” is pretty effective. In a particularly naked example of Marx’s “false consciousness,” we see the characters’ submission to corporate control even as we recognize that all is not awesome in Lego Land.

If only the song weren’t so damned catchy. Like the film, the song appears to be crafted to appeal to both the kids who make up its target demographic and the parents stuck in the theater with them. The melody is deliberately simple with a pitch range and structure that any three year-old could sing. However, the song’s “four on the floor” rhythms and electro-flavored instrumentation also make it palatable to adults as well. The end result is an earworm that insinuated itself into my brain for days at a time.

Much of the song’s success derives from its ability to play it both ways. On the one hand, as a theme song for The LEGO Movie, “Everything is Awesome!!!” gently satirizes the unholy marriage between business and government that structures the Lego universe. On the other hand, though, the song appears in what is essentially a feature-length commercial for toys. Moreover, it is so hooky and memorable that it also helps promote The LEGO Movie in various ancillary markets. Still, if that sounds even more cynical than Begin Again’s depiction of corporate sellout, I can’t think of another song that would better fit what The LEGO Movie tries to accomplish.

The final nominee is “Glory” by John Legend and Common. The song is featured in Selma, Ava DuVernay’s biopic about Martin Luther King Jr. A soulful, gospel-inflected ballad, the song was written as a tribute to the members of the Civil Rights movement who worked tirelessly in their fight for equality, especially their efforts to help passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. It appears during an epilogue underscoring a montage that mixes fictional scenes with photographs and archival footage of the real-life Selma marches. The sequence also relates the fates of the various historical actors depicted in the film, reminding us of the sacrifices they made.

With its soaring chorus and rapped verses, “Glory” is decidedly contemporary fare. Yet it remains a worthy successor to the rhythm-and-blues classics heard in the film, such as Otis Redding’s “Ole Man Trouble” and The Impressions’s “Keep on Pushin’”.

Like the other four nominees, “Glory” displays the kind of multi-functionality that is the hallmark of great movie songs. Its style reminds viewers of the important role played by black churches in the early years of the Civil Rights movement. The song’s uplifting tone also provides a satisfying emotional climax to the film, providing a sense of triumph over the physical and political challenges faced by the film’s characters. Lastly, Common’s lyrical reference to the protests of Ferguson also reminds us that the struggles for civil rights continue.

The historical parallels between current events and protests portrayed in Selma have earned considerable commentary by pundits and journalists. And one doesn’t need to hear the song or even see the movie to understand the reasons why the phrase “Black lives matter” resonates across these different generations. Yet Legend and Common’s song makes perhaps the film’s most concrete and explicit connection between past and present. By linking the literal and metaphorical dimensions of Selma’s historical allegory, “Glory” achieves an associative richness that very few recent movie songs can match.

Prediction

Entertainment Weekly characterizes this as a two-horse race. The magazine suggests that “Everything is Awesome!!!” and “Glory” each give voters a chance to right a perceived wrong, honoring a film snubbed in some of the other categories.

As I indicated earlier, I find the pop panache of “Everything is Awesome!!!” undeniable. More important perhaps, the filmmakers adroitly weave the song into particular scenes in The LEGO Movie. Still, I don’t think that will be enough for “Everything is Awesome!!!” to take home the top prize. In underscoring Selma’s import and its timeliness, “Glory” does something that none of the other nominees does. By drawing together African-American musical styles, both past and present, “Glory” is imbued with a political and historical resonance that strives for higher ground. For that reason, I expect John Legend and Common will add Oscar to the other accolades they have received.

First, many thanks to Jeremy Morris, my colleague in the University of Wisconsin’s Communication Arts Department, whose thoughts on The LEGO Movie have unquestionably shaped my own. A shout-out also to Jon Burlingame, whose coverage of film music topics in Variety is second to none. Burlingame has surveyed the best Original Score nominees, and the Best Original Song nominees.

On Desplat, see Burlingame’s article “Alexandre Desplat’s Twin Takes on WWII: ‘The Imitation Game’ and ‘Unbroken.” Additionally, Matt Zoller Seitz’s companion volume to The Grand Budapest Hotel contains an interview with Desplat and an analysis of the score that reproduces excerpts from certain cues. More on Seitz’s book can be found in this promo film. The Grand Budapest Hotel’s entire soundtrack is on YouTube. Earlier entries on The Grand Budapest Hotel on this site are here and here.

For those interested in the development of Interstellar’s score, there’s a short video on J. Bryan Lowder’s blog containing interviews with both Christopher Nolan and Hans Zimmer. Lowder offers a thorough overview of Zimmer’s score here. John Legend offers comments on his song for Selma.

Begin Again.