Archive for the 'B films' Category

Ladies at all levels

La cigarette (1919)

Kristin here:

Earlier this month Flicker Alley released another of its ambitious collections of historic films, Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology. The dual-format edition contains three discs DVDs and three Blu-ray discs. Its ambitions are reflected in part by the volume of material included (652 minutes) and in part by the range of its contents, from well-known classics to obscure titles.

The collection was one of the last projects curated and produced by the late David Shephard. As with many of Flicker Alley’s releases, it was a joint project with Film Preservation Associates (Blackhawk Films) and Lobster Films of Paris, working with several film archives. The films are arranged chronologically, with the earliest being Les chiens savants (1902), a music-hall dog act attributed to Alice Guy Blaché, and the latest Maya Deren’s classic experimental film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943).

The publicity for the collection emphasizes that “More women worked in film during its first two decades than at any time since” (from the slipcase text). I would be interested in how such a claim was arrived at. It seems unlikely to me, if only because the film industries of the major producing countries have grown enormously since the silent and early sound periods. Still, despite this claim, the notes in the accompanying booklet (written by Kate Saccone, Manager of the Women Film Pioneers Project) describe how the DVD/Blu-ray release “reclaims that stature of ‘woman director’ and celebrates it in all its glory.” (One film included, Discontent [1916], is listed as “by Lois Weber”; in this case she wrote the screenplay, which was directed by Allen Siegler.) Thus the program does not survey the range of filmmaking work women performed–but such a survey would be essentially impossible. The lack of detailed credits on early films makes it difficult to determine even the director of a given film.

The silent films

It is not really possible to discuss all the films, but I’ll mention some and link to earlier entries where we’ve discussed some of them.

Of the 25 titles on the three discs, fourteen are silent. Six of these give an overview of work of Blaché, with three French films and three made after her move to the US.

Lois Weber is represented by three films, starting with perhaps her best-known work, Suspense (1913). With its unusual angles (see above), elaborate split-screen phone conversations, and action shown in the rear-view mirror of a speeding car, this is one of those films you show people to demonstrate how wonderfully inventive directors around the world became in that incredible year. I am also very fond of her feature, The Blot (1921).

The third Weber film, Discontent (1916), may surprise those familiar with her socially conscious features. In the mid-1910s Weber worked in a variety of genres. While David was doing research recently at the Library of Congress, he watched some incomplete or deteriorated Weber films that haven’t been seen widely. He wrote about False Colors here and here. Discontent is a comedy with a moral. An elderly man is living in a home for retirees, but he envies his well-to-do family. Finally they invite him to live with them, and naturally everyone ends up annoyed by the situation–including the protagonist, who winds up returning to the home and his friends.

Mabel Normand apparently directed quite a number of her films for Mack Sennett, and Mabel’s Strange Predicament (1914) is one of them. Its cast also includes Charles Chaplin and was his third film to be released, although it was the second shot and the first one in which he wore a version of his Little Tramp costume. Not surprisingly, he steals every scene he’s in. Normand even plays second fiddle to him, with her character forced for a stretch of the action to hide under a bed, where she is barely visible while Chaplin performs some funny business in the same room. (The print seems to have been assembled from two different copies, the bulk of the film being in mediocre condition with the ending abruptly switching to a much clearer image.)

One curious item in the program is Madeline Brandeis’ The Star Prince (1918). According to her page on the Women Film Pioneer’s Project, Brandeis was a wealthy woman who made films, mainly centering around children, as a hobby. Some of these were apparently intended for educational use. The Star Prince, her first film, is clearly aimed at children. A few of its adult characters are played by young adults, while children play both children and adults. This becomes a bit disconcerting when we assume for a long time that the prince and princess are perhaps seven or eight, until they fall in love and become engaged.

Despite the amateur filmmaking, there are some attempts at superimpositions and other special effects to convey the fantasy, as well as an charmingly clumsy pixillation of a squirrel puppet, the position of which is changed far too much between exposures.

This is the sort of local production, made outside the mainstream industry, that so seldom survives, and it is a welcome balance to the more sophisticated works that make up the bulk of this collection.

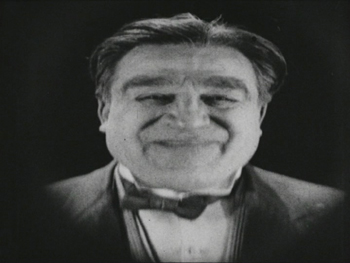

Speaking of which, the next part of the program consists of two features by one of the best-known female directors, Germain Dulac. The first, La cigarette, appeared in 1919. It’s melodrama about an fifty-ish Egyptologist, who has just acquired the mummy of a young princess who was unfaithful to her older husband. The professor begins to imagine that he is suffering a similar fate when his young and beautiful wife (see top) begins spending time with an athletic young fellow.

I remember seeing this film nearly forty years ago and thinking it was pretty weak. Luckily I have seen many films from this era since and know better how to watch them. Seeing it again I liked it quite a bit. It’s beautifully shot and well acted, and its sympathetic depiction of the doubting husband and the clever and resourceful wife is more subtle, in my opinion, than that of the marriage in The Smiling Madame Beudet (which is also included in this set). I was glad to have a chance to see the film again and recognize it as being among Dulac’s best work.

The silent section of the program ends with Olga Preobrazhenskaia’s The Peasant Women of Ryazan (1927). The title emphasizes that Preobrazhenskaia’s film is set in a provincial area. Ryazan, the capitol, is about 120 miles southeast of Moscow, so it is not one of the far-flung regions of the USSR. Still, it would have been distant enough at the time to have its own distinctive culture. Peasant Women gives us plenty of local costumes and customs without giving the sense of this being ethnography first and narrative second. Exotic though it may seem to us, this would have been recent history to Russians when it first came out.

Although most synopses claim that the story runs from 1916 to 1918, it actually begins shortly before World War I, probably in 1914, as the heroine Anna marries Ivan in a lively wedding scene including a carriage ride for the bridal couple (below). Shortly thereafter news of the war comes, and Ivan reluctantly departs for to serve in it. Anna is left in the household of her lecherous father-in-law, who rapes and impregnates her. The war goes on and ends, with the Revolution taking place entirely off-screen.

The second woman of the title is Wassilissa, a tougher sort, who applies to convert a decaying local mansion (we are left to assume that it was confiscated in the wake of the Revolution). She is seen at the end as being the prototype of the new Soviet woman, though Preobrazhenskaia throughout avoids hitting us over the head with overt propaganda.

The sound films

Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the directors on the third disc, devoted to sound films, are likely to be more familiar to modern viewers. Nevertheless, Marie-Louise Iribe and her film Le Roi des Aulnes (1920), were completely unknown to me. She was the niece of designer Paul Iribe and worked primarily an actress during the 1920s, and this seems to have been her only solo directorial effort. (IMDb lists her as the co-director of the 1928 version of Hara-Kiri, which she also starred in.)

Le Roi des Aulnes is one of the musically based movies that were popular in the early sound era, being based on both Goethe’s and Schubert’s versions of “Der Erlkönig.” It’s nicely photographed, and the part of the father is played by Otto Gebühr, known for being trapped by his resemblance to Friederick der Grosse into playing that role time after time from 1921 to 1941. He’s predictably excellent here, though the stretching of the short poem into a 45-minute film forces him to register worry and eventually grief throughout. Indeed, despite extrapolated incidents, such as the injury of the father’s horse and the need to procure a new one, a great deal of repetition occurs: lots of riding through marshes and menacing appearances by the Erlkönig, who is portrayed as a large man in chain-mail.

The special effects are the most impressive thing about the film, using double superimpositions in widely different scales, with the giant king holding a small fairy on his palm.

Despite its problems, the film is a valuable addition to our examples of this mildly avant-garde trend that flourished for a short time.

Most of the rest of the directors are well-known and can be mentioned more briefly.

The great animator and innovator of silhouette animation Lotte Reiniger is represented by three short films: Harlequin (1931), The Stolen Heart (1934), and Papageno (1935). I have written about Reiniger’s complex compositions, including her subtly shaded backgrounds. Of the directors represented here, she is the one who enjoyed the longest career, from 1916, when she would have been 17, to 1980, when she was 81. I discuss a BFI boxed set of some of her 1950s films here. I haven’t been able to find a complete filmography, but William Moritz estimates that she made “nearly 70 films.”

Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker’s A Night on Bald Mountain is similarly familiar. Like Iribe’s Le Roi des Aulnes, it falls into the genre of illustrations of existing musical pieces, being an illustration of a piece of the same name by Modest Mussorgsky, as arranged by Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov. It was created by manipulating hundreds of pins on a large frame called a pinboard, invented by Alexeieff, his first wife Alexandra Grinevsky-Alexeieff (whom he divorced in order to marry Parker in 1940), and Parker. The textured effect is quite unlike that of any other type of animation.

Dorothy Davenport was a prolific actress from 1910 to 1934. She is perhaps most remembered as the widow of Wallace Reid, a star who died from the effects of morphine in 1923. She directed seven films over the next decade, ending with the film in this set, The Woman Condemned (1934), mostly either uncredited or signing herself Mrs. Wallace Reid.

The Woman Condemned is a B picture, produced independently and distributed through the states’ rights system. It’s a competently done murder mystery that gains some interest by withholding a great deal of information from the audience. There are two main female characters, the victim and the accused (seen below in an interrogation scene), and we have very little idea of their motives and goals until the climax of the film. The revelations involve a twist on the same level of groan-worthiness as “and then she woke up.” But again, having a little-known B picture adds to the wide variety of films presented here.

One can hardly study early women directors and skip over the favored documentarist of the Third Reich, Leni Riefenstahl. Day of Freedom (1935) is a good choice for inclusion, occupying only 17 minutes of screen time and amply demonstrating Riefenstahl’s undeniable gift for creating gorgeous images from ominous subjects.

Experimental animator Mary Ellen Bute is represented by two contrasting abstract shorts, the lovely black-and-white ballet of shapes, Parabola (1937) and the vibrant and humorous Spook Sport (1939), the latter (below) made with the collaboration of Norman McLaren.

Dorothy Arzner, the only woman to direct mainstream Hollywood A films from the 1930s to the and 1940s, is introduced via a clip from one of her most famous films, Dance, Girl, Dance (1940). In the scene, Maureen O’Hara’s character interrupts her dance routine to tell off an audience of mostly men who are cat-calling her.

Maya Deren’s first film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) ends the program (see bottom). It is a happy choice, since of all the films in the program, it has undoubtedly had the greatest influence on the cinema. Much of the subsequent avant-garde cinema has turned away from music-inspired abstraction and opted for ambiguity, psychological mystery, and impossible time, space, and causality.

Valuable though this collection is, I cannot help but think that some of the directors represented have been oversold. Saccone sums them up:

Together, these 14 early women director have produced bodies of work that are inspiring, controversial, challenging, invigorating, and thought provoking. These women were technically and stylistically innovative, pushing narrative, aesthetic, and genre boundaries.

Surely not all of them meet these criteria. We would hardly expect one hundred per cent of the male directors of the same era to be “technically and stylistically innovative,” so why should we expect all of the work by fourteen varied female directors to be so? Saccone quotes Tami Williams’ book, Germaine Dulac: A Cinema of Sensations. on how the director searched “for new techniques that, in the light of official discourse of governmental and social conservatism, and the modernity of the new medium, were capable of expressing her progressive, antibourgeois, nonconformist, and feminist social vision.” Saccone sees this search in The Smiling Madame Beudet, where “Dulac utilizes cinema-specific techniques such as irises, slow motion, distortion, and superimposition, as well as associative editing, to give visibility to the inner experiences and fantasies of an unhappily married woman …”

Readers might infer that Dulac innovated these techniques. Yet they had already been established as conventions of French Impressionist cinema, notably in Abel Gance’s J’accuse (1919) and La roue (1922) and Marcel L’Herbier’s El Dorado (1921). For example, Dulac surely derived the distorted image of Beudet that conveys his wife’s disgust (below left) from a similar shot of a drunken man in El Dorado (right).

This is not to say Dulac isn’t a fine filmmaker or that she had no new ideas of her own. Only that she didn’t single-handed discover these techniques, but rather she turned the emerging repertoire of Impressionist techniques toward portraying a woman’s experience.

In some cases films that were co-directed by these women are presented as their sole efforts. Lois Weber’s Suspense was directed, as were many of her early shorts, with her husband, Phillips Smalley. Quotations from interviews with both Weber and Smalley make this clear. In 1914, Smalley said of his wife, “She is as much the director and even more the constructor of Rex pictures than I.” “Even more” because Weber often wrote the screenplays for their films and in at least some cases edited them. Weber later described how Smalley worked from her scripts: “Mr. Smalley got my idea. He painted the scenery, played the leading role and helped direct the cameraman.” Directing the cameraman is part of the job of a director.

The list of films in the booklet attributes Night on Bald Mountain entirely to Claire Parker, though on the backs of the disc cases the credit is to Claire Parker and Alexandre Alexeieff. Alexander Hackenschmied (aka Hammid) is not mentioned in the list of films, and the booklet refers to him as having a “close collaboration ” with Deren, even though he and Deren are both listed as directors on the original credits of Meshes of the Afternoon.

Still, if the collection does not make the case that all of the women represented were wildly talented and innovative, it does show the variety of ways in which women managed to work both in and out of the mainstream industry. It’s valuable collection of historical examples and should be welcomed by anyone interested in the silent and early sound eras.

It is worth noting in closing that viewers should not expect all of these films to be presented in the usual beautiful restorations we are used to from Flicker Alley. Some of these films are indeed gorgeous, including the two Mary Ellen Bute shorts, Peasant Women of Ryazan, Day of Freedom, Meshes of the Afternoon, and La cigarette (though the latter has some small stretches of severe nitrate decomposition). Other prints are quite good or at least acceptable. A few of the films simply do not survive in any but battered or faded prints, notably Discontent and The Star Prince. But we are lucky to have them at all.

The quotations from the Smalley and Weber interviews are from Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015), pp. 26-27.

[May 23] Many thanks to Manfred Polak, who has drawn my attention to a higher estimate of Reiniger’s lifetime production of silhouette films. Her friend and executor, Alfred Happ, put the figure at about 80. The source is an exhibition catalog from the Stadtmuseum Tübingen, which houses Reiniger’s archived material: Lotte Reiniger, Carl Koch, Jean Renoir. Szenen einer Freundschaft. Die gemeinsamen Filme. ed. Heiner Gassen and Claudine Pachnicke (Stadtmuseum Tübingen, 1994).

Carl Koch was Reiniger’s husband and collaborator; Reiniger created an animated sequence for her supporter and friend Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise. According to Manfred, “Alfred Happ and his wife Helga were Reiniger’s closest friends and caretakers in her last years in Dettenhausen (near Tübingen, Germany). After Reiniger’s death, Alfred Happ was the administrator of her estate. If you ever come to Tübingen, visit the Stadtmuseum (City Museum), where her estate is hosted now. A part of it is shown in a permanent exhibition.” He also provided a link to a touching account of Reiniger’s friendship with the Happs.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)

Screenplaying

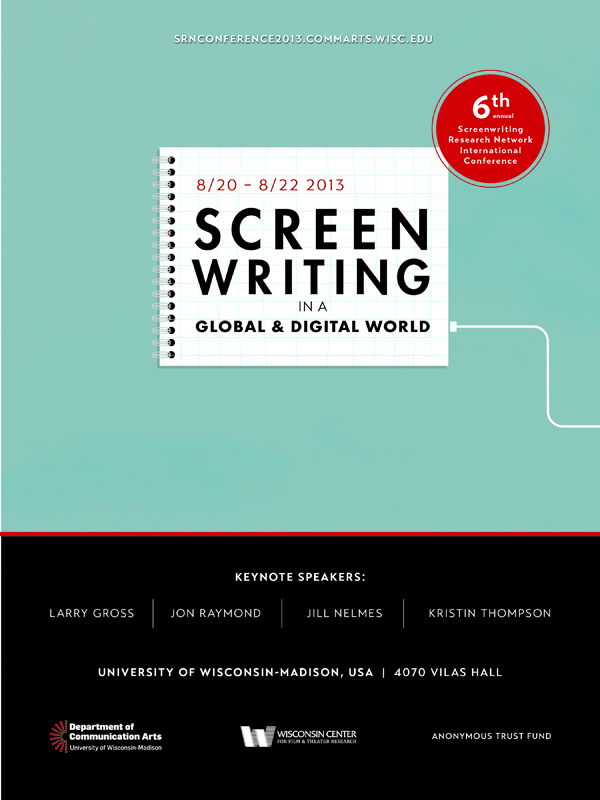

Design by Christina King.

DB and Kristin here:

Two years ago DB reported on the gathering in Brussels of the Screenwriting Research Network (here and here). This year, thanks to our colleagues J. J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, our department hosted the conference. Again, it was chock-a-block with stimulating papers. We also introduced our visitors to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which houses thousands of screenplays. It wasn’t all work, either. Participants were spotted lingering at our lakeside terrace or making their way through the cafes and saloons lining State Street. We believe it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all.

Since there were simultaneous sessions, nobody could attend everything, and we can’t run through all the papers we heard. (So do consult the program for more information.) Herewith, some highlights that set us thinking.

In the key of keynote

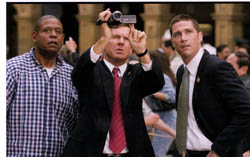

Larry Gross and Jon Raymond.

The four keynoters encapsulated the conference’s very wide range. In a workshop keynote Jill Nelmes, Editor of the Journal of Screenwriting, offered a historical survey of screenwriting research in all media, with special emphasis on television. The Big Hollywood Movie was covered by Kristin, whose paper, “Extended How?” examined the ways in which directors’ cuts and extended editions handle the multi-part structure she posits as a foundation of contemporary Hollywood. We won’t say more here, since she may turn it into a blog for this site.

Larry Gross had already started off the conference with a bang by taking us to Japan. Larry has written 48 HRS, Streets of Fire, Geronimo, True Crime, and other mainstream studio pictures, as well as television episodes, TV mini-series, and independent films like Prozac Nation and We Don’t Live Here Anymore. He also writes outstanding film criticism for Sight and Sound, Film Comment, and other journals, and he teaches screenwriting at New York University. Scott Macauley’s informative March interview with Larry is at Filmmaker Magazine.

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

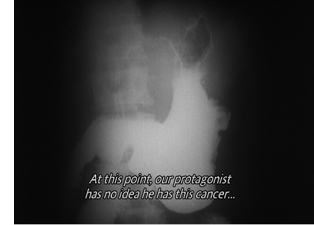

He illustrated his ideas with an in-depth examination of Kurosawa’s Ikiru. He had long thought the film “an official liberal-humanist classic,” until a course with Annette Michelson at NYU showed him that there was a lot to ponder there. Specifically, Kurosawa starts by telling the audience the end of the story: Watanabe will die of cancer. But he doesn’t know that, and neither do all the people he encounters. The strategy denies us a lot of suspense, so to hold our interest Kurosawa must engross us by delineating his relations with his colleagues, with the mothers petitioning for the neighborhood sump to be drained, and with the stray people he meets casually on his night out.

Larry showed how carefully Kurosawa played off the characters’ indifference, misunderstanding, and lack of awareness. In particular, the neighborhood wives display to Watanabe what Maurice Blanchot called “the ignorance and spontaneity of true affection.” Ikiru’s refusal to explain what it means typifies a kind of cinema that asks the audience to share the burden of understanding. “Ikiru understands how a screenplay can be composed with the audience.”

Jon Raymond’s keynote carried things to independent US film. Jon has become famous for a novel (The Half-Life) and short stories (Livability), as well as for his screenplays for Kelly Reichardt’s features. The most recent, the forthcoming Night Moves, is currently in competition at Venice. The teaser title of Jon’s address, “Screenwriting as Earth Art,” turned out to be a reference to the fact that most of his stories take place in the vicinity of his home. He has found satisfaction by composing on familiar ground.

In younger days Jon tried painting and filmmaking; a Public Access feature based on the comic strip Crock turned out to be “a movie best experienced in fast forward.” But he found that writing offered the most creative satisfaction. At the same time, while assisting Todd Haynes on Far from Heaven, he met Kelly Reichardt, who was looking for a property to adapt on a small budget. The result was Old Joy, “a New Age western,” in which two men display the violence latent in the new passive-aggressive masculinity flourishing on the Coast. Jon believes that Reichardt’s handling created a cinematic parallel to the dense intricacy of a short story.

In later collaborations, Jon mapped his patch of Portland in other ways. Seeing the annual migration of workers to Alaskan canneries, and hearing the train whistles wafting through his neighborhood, he created the story that became Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy (above). Reichardt began adapting the story to film before he had finished writing it. Similarly, Jon merged the booming housing market of the 2000s and the history of the Oregon Trail into a project that paralleled today’s gentrification with nineteenth-century colonization. Reichardt turned his screenplay into Meek’s Cutoff, a “desert poem” that completed what some have called their Oregon Trilogy. For Jon, the trilogy constitutes an alternative regional history, one that traces the process of “sowing the land with failure, betrayal, and humiliation.”

Plots and no plots

The Adventures of André and Wally B (1984).

More than most areas of filmmaking, screenwriting reminds us of the institutional framework surrounding most creative work cinema. Scholars studying the screenplay are naturally often pursuing the endless revisions, refusals, and rethinks that a film goes through in the preparation phase. It’s easy to see this as a one-versus-one struggle, but in many cases the process takes place within a social environment possessing its own roles and rules.

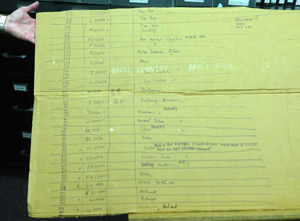

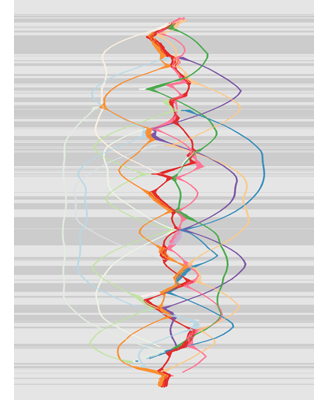

Ian MacDonald offered an excellent example in his study of the work processes behind the UK television soap opera Emmerdale. He proposed that we replace model of industrial film production as an auto factory with that of a carpet factory. Instead of the TV episode being seen as a discrete unit, like a car, it should be conceived as an ongoing fabric woven of many threads. In Emmerdale and other series, the unit of production isn’t the episode but rather the story line. Each episode is sliced out of a much bigger stretch of ongoing patterns. Ian illustrated this with the writers’ planning chart that was mounted on the wall.

The vertical column represents scenes, marked off as episodes. The characters are color-coded cards connected by solid liness that weave their way through the scenes. These waves are the melodies; the scenes are the bar-lines. In each episode, two or three characters are given prominence, while the subordinate ones contribute their harmonies. Ian’s discussion reminded me of how Hong Kong filmmakers did much the same thing in the 1980s: plotting films reel by reel and color-coding certain elements—gags, fights, and chases—to make sure that each reel had its share of attractions. This is the sort of insight into structure that institutional research can yield: Structure is these people’s business.

Other Hollywood studios envy Pixar for to its appealing, carefully structured stories. Richard Neupert showed how that tradition goes back to the earliest years at Pixar. Even in demo films which were made to show off technological innovations, the makers tried to reveal how computer animation, even in its early, simple form, could create engaging tales. At a period when computer animation could only render smooth, simple shapes, the Pixar team found appropriate subject matter, with highly stylized characters in The Adventures of André and Wally B and Luxo, Jr.

Remarkably, these tiny films have balanced “acts.” Each is 80 seconds long and has a key action at exactly 40 seconds in: the entrance of Wally B and the moment when the little Luxo lamp jumps on a ball. Similarly, Red’s Dream‘s parts run 50-100-50 seconds. This care in timing continued with the features: Toy Story’s midpoint comes when Woody finally shifts strategies, realizing he has to work with Buzz. And what about Pixar’s perceived slump in recent years? someone asked during the question session. Neupert pointed out that Pixar’s founders have aged, and there may no longer be quite the sense of excitement and discovery pushing the team to surpass others and themselves.

Sometimes institutional traditions come into conflict. Petr Szczepanik’s talk traced in meticulous detail how screenplay development in Czechoslovakia was altered in the years from 1930 to the 1950s. Czech filmmakers developed their own system of moving from theme and story germ to final screenplay. But with the Communist takeover there came the demand to add the Soviet model of the “literary screenplay,” a detailed specification of scenes, dialogue, and the like. Filmmakers resisted this, preferring the customary and more flexible “technical screenplay” that was largely the province of the director. Petr mentioned new screenwriting trends pioneered by Frank Daniel that gave directors the authority to modify the literary format. By the late 1950s, filmmakers had found ways to make the literary screenplay a less rigid blueprint for filming.

Back in the USSR, the screenwriting institution found even the literary screenplay a difficult basis for mass output. Maria Belodubrovskaya’s talk focused on “plotlessness” as a rallying cry and term of abuse in the 1930s-1940s Soviet film. There were long debates about whether “themes” sufficed to make a film or whether you needed strong plots in the Hollywood vein. Film-policy supervisor Boris Shumyatsky urged the latter course, and the popular success of Chapayev (1934) seemed to support his case. By the late 1930s, though, Shumyatsky was purged and the tide turned against strong plots. Film executives found a concern with plot too “Western” and “cosmopolitan,” and annual film production became based on themes rather than stories. Most provocatively, Masha suggested a lingering influence of Soviet Montage storytelling, which based films on vivid but loosely linked episodes. She illustrated her case with an analysis of Pudovkin’s In the Name of the Motherland (1943), with its diffuse lines of action and sudden reversals and omissions.

Back we go

Scarface (1932).

Naturally, Madison wouldn’t be Madison without strong papers on the history of cinema, and many conference presentations suited the tenor of the joint.

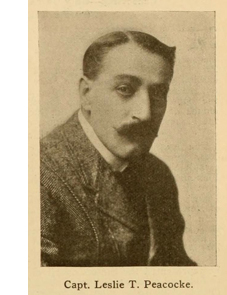

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen surveyed Peacocke’s contribution to the emerging scenario market. Peacocke believed that successful screenwriting couldn’t be taught, but he could give hints about developing original stories, thinking in visual terms, and practical craft maneuvers like snappy names for characters. During the Q & A, Stephen added that a great deal of Peacocke’s rhetoric was aiming to raise his own profile in the industry. In conversation afterward, Stephen praised the Media History Digital Library and Lantern (flagged in an earlier blog) for immensely helping research into early film. Here, for example, is Peacocke’s 216-item dossier on Lantern.

Andrea Comiskey argued that for the same period, we can study scripts and extrapolate craft practices that otherwise go undocumented. Her focus was the disparity between what manuals like Peacocke’s said and what actually got jotted down in working scenarios. Studying several screenplays from the American Film Company of Santa Barbara, she found that the manuals’ recommended stylistic approach was revised in the course of shooting.

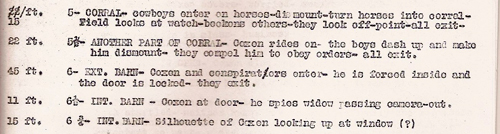

The manuals proposed that each scene would be built out of a lengthy single shot (called, confusingly, a “scene”) which could at judicious moments be interrupted by an “insert.” An insert was usually a letter or piece of printed matter read by the characters, but it might also be a detail shot of a prop, hands, or an actor’s face.

In preparing scenarios, the writers assigned numbers to each “scene,” as the manuals recommended. But Andrea found that in the filming, the director and cameraman added shots, breaking down the action into more bits. This was, in effect, a move away from the strict scene/insert method and a shift toward what would become the classical continuity system. To maintain a paper record for the editor, the interpolated shots would be recorded and labeled in fractions. Instead of a straight cut from 6 to 7, the filmmakers might wedge in 6 ½, 6 ¾, and so on. Here’s an extract from Armed Intervention (1913), courtesy Andrea.

Strange as this sounds to us today, it was preferable to renumbering the shots, which could cause confusion. (Is shot 17 the original 17 or the later one?) The fractions kept the footage consistent with the scenario across the production process. So it turns out that (as usual?) filmmakers were a bit ahead of the screenplay gurus, even back in the 1910s.

Lea Jacobs asked a question about the transition from silent to sound film: How did filmmakers manage the pacing of dialogue? Silent movies had great freedom of pacing, while the shift to talkies seemed to many filmmakers to slow things down. Lea’s research indicated that two strategies for speeding things up emerged: creating shorter scenes and shortening dialogue passages within them. She reviewed how these ideas emerged in Hollywood’s own discourse in the 1930s and in certain films. In the first years of sound, scenes were rather long (often because they were derived from stage plays) and speeches were similarly extended. But in the 1931-1932 season, she argued, short scenes and quicker repartee became more common.

She traced the process in three films of Howard Hawks, from the stagy Dawn Patrol (1930) through The Criminal Code (1931), which opens in the new style but then turns to longer sequences, and then to Scarface (1932). The gangster film shifted toward shorter scenes and more laconic dialogue than did other genres, and Scarface displays this in full flower. Tony Camonte’s takeover of the South Side beer trade is presented in six harsh, violent scenes that add up to little more than three minutes. Workers in the sound cinema, it seems, were soon pushing toward that rapid tempo we identify with the 1930s.

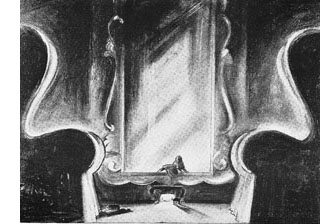

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Spielberg used sketches in addition to a screenplay from the start. Duel, surprisingly enough, was supposed to be shot in a studio, but the director insisted on working on location. The sketches he made for it do not resemble a traditional storyboard but instead are like pictorial maps framed from an extremely high angle. He also plotted out the paths of the vehicles with overhead views of the roads. The storyboards for Jaws were done from the novel at the same time that the script was being written, just as Menzies had done with Gone with the Wind. (The same thing happened with Jurassic Park.) Storyboards were vital, among other things, for telling the crew which of the four versions of the shark would be used. One fake shark had only a right side, another a left, and which one was needed depended on the direction the shark was crossing the screen. The speakers distinguished between the “working” storyboard and the “public” one. The public one is what sometimes get published, but it usually has each image cropped to remove the information about the shot (e.g., who will work on it) noted underneath.

Brad Schauer contributed to a roundtable on the American B film back when The Blog was in its infancy. He has been researching the role of B’s in the industry for many years, and he brought to our event some new ideas about them in the postwar period. His paper, “First-Run and Cut-Rate” showed that there were still plenty of theatres showing double bills in the 1950s and 1960s (DB can confirm it), and the market needed solid, 70-90 minute fillers. One answer was the “programmer,” or the “shaky A” that featured somewhat well-known talent, color, location shooting, and familiar genres (Westerns, swashbucklers, horror, crime, comedy, and science fiction). Shot in half the time of an A, with budgets in the $500,000-$750,000 range, programmers fleshed out double bills and sometimes broke into the A market.

What does this have to do with screenwriting? Brad decided to test whether Kristin’s ideas about four-part structure (here and here) held good with programmers. Looking at several, he came up with a plausible account that films like Battle at Apache Pass and Against All Flags simply compressed the four parts into short chunks, typically running fifteen to twenty minutes. In The Golden Blade, Rock Hudson formulates his goal (revenge) two and a half minutes into the movie.

Too few things happen?

La Pointe Courte (1955).

In most films, Agnes Varda said, “I find that too many things happen.” How can screenplay studies move beyond Hollywood’s jammed dramaturgy to consider the more spacious sort of storytelling we find in “art cinema”?

Colin Burnett offered a general overview of art-cinema norms that is somewhat parallel to our and Janet Staiger’s The Classical Hollywood Cinema. To a great extent, of course, “art films” differ from classically constructed films. They can be more ambiguous, more reflexive, more stylized and at the same time more naturalistic. They often replace a tight causal chain with episodic construction and nuances of characterization. The protagonists may have complex mental states; they may have inconsistent goals, or no goals at all; they may be passive; they may have shifting identities.

Yet Colin argued against claims that art films lack narrative altogether. “Art films offer reduced scene dramaturgy, rarely its complete absence.” They possess structuring devices comparable to Hollywood acts. A film’s large-scale parts may be based on a character’s development, on changes in space or time, or on variations of action and/or reaction. A question was raised as to whether such a broad category as art cinema could be characterized in such ways. Given the enormous range of types of films made in the Hollywood tradition, however, it seems possible that the art cinema could be described in a similar fashion. (For our thoughts on the matter, go here and here.)

A great many art-film strategies can be seen as stemming from modernism in literature and the other arts. As if offering a case study illustrating Colin’s argument, Kelley Conway focused on La Pointe Courte. Varda’s first film is now coming to be considered the earliest New Wave feature. But Varda wasn’t the prototypical New Waver. She wasn’t a man, she wasn’t a cinephile, and she took her inspiration from high art, not popular culture. A professional photographer who loved painting and literature, she brought to this film (made at age 26) a bold awareness of twentieth-century modernism. The result was a striking juxtaposition of stylization and realism, personal drama and community routine. In La Pointe Courte, we might say, neorealism meets the second half of Hiroshima mon amour.

Inspired by Faulkner’s Wild Palms, Varda braided together two stories. While families in a fishing village live their everyday lives, an educated couple work through their marriage problems in a long walk. Remarkably, Varda had not seen Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy. After supplying background on the production process, Kelley focused on matters of performance. She explained how Varda, well aware of Brechtian “distanciation,” made the couple’s dialogue deliberately flat. By contrast, the villagers’ lines, through scripted, were treated more naturalistically. La Pointe Courte emerges as an anomie-drenched demonstration of how little you need to make an engrossing movie.

To script or not to script (or to pretend not to script)

Maidstone (1970).

The SRN embraces research into the absence of a script as well. At one limit is the work of avant-gardists like Stan Brakhage. John Powers’ “A Pony, Not to Be Ridden” discussed how non-narrative filmmakers used paper and pencil to organize their work, much as a poet might make notes on a draft. John’s examples were three films by Brakhage, each developed out of sketches and jottings assembled after shooting but before editing. Unconstrained by any script format, Brakhage had to invent his own version of storyboarding and screenplay notes.

Compilation filmmakers also discover their structure in the process of collecting and sifting material. Documentarist Emile de Antonio, whose collection resides in our WCFTR, had to build his screenplay up after he had assembled some material. “A script won’t be ready,” he remarked, “until the film is finished.” Vance Kepley’s paper showed that In the Year of the Pig was the result of a massive effort of “information management.” De Antonio sought out press clippings, sound recordings, and news footage and then had to create an archive with its own system of labeling, cross-references, and easy access.

De Antonio started with the soundtrack, which was itself a montage of found material, and then created a “paper film,” cutting and pasting vocal passages and descriptions of images. At the limit, he charted his film’s structure with magic-marker notations on large strips of corrugated cardboard, as Vance illustrated.

One panel session took a close look at improvisation in fiction features. Line Langebek and Spencer Parsons gave a lively paper with the innocuous title “Cassavetes’ Screenwriting Practice.” Explaining that Cassavetes did use scripts (“sometimes overwritten”), and he relied on actors to help create them in workshop sessions, they proposed thinking of his work as exemplifying the “spacious screenplay.” Their ten principles characterizing this sort of construction include:

Write with specific actors in mind. Use a “situational” dramaturgy rather than a rise-and-fall one. The work is modeled on free jazz, with moments set aside for specific actors. Even minor actors get their solos. Shoot in sequence, so that emotional development can be modulated across the performances.

Line and Spencer’s precise discussions cast a lot of light on the specific nature of Cassavetes’ creative process and pointed paths for other directors. They added that the spacious screenplay is really for the actors and the director; the financiers should be given something more traditional.

Norman Mailer called Cassavetes’ films “semi-improvised.” He tried to go further, J. J. Murphy explained in “Cinema as Provocation.” Mailer wanted his three films Wild 90, Beyond the Law, and Maidstone to be completely improvised, utterly in the moment. “The moment,” he proclaimed, “is a mystery.” Mailer opposed the “femininity” he claimed to find in Warhol’s films, so he encouraged his male players to indulge their machismo playing gangsters, cops, and aggressive entrepreneurs. J. J., whose book on Warhol stressed the psychodrama component of the films, finds Mailer no less devoted to having his players work out their problems through unrestrained behavior. The climax of Maidstone, in which an enraged Rip Torn begins to strangle Mailer, becomes the logical outcome of Mailer’s needling provocation of his actors. How ya like the mystery of this moment, Norman?

Within the Hollywood industry, improvisation is identified strongly with Robert Altman’s films, but Mark Minnett‘s “Altman Unscripted?” shows another side to his work. Focusing on The Long Goodbye, Mark finds that the film doesn’t vary wildly from the script. The principle plot arcs aren’t changed, although Altman decorates them by letting minor characters inject some novelty. He encouraged the guard who does impressions of Hollywood stars, and he gave latitude to Elliott Gould, whose improvisation elaborates on the issues of trust and bonding that are embedded in the script. Some scenes are condensed or altered, as often happens on any production, but the Altman mystique of freewheeling, anything-goes creativity isn’t borne out by the film. Altman’s characteristic touches are built around what’s “narratively essential,” as laid out in the screenplay.

We learned a lot more at the conference than we can cover here. For example, Jule Selbo brought to our attention Sakane Tazuko, a woman screenwriter-director in 1930s Japan. Rosamund Davies explored the ways in which transmedia storytelling could enhance historical dramas. Carmen Sofia Brenes traced out how different senses of verisimilitude in Aristotle’s Poetics might apply to screenwriting. We learned of a planned encyclopedia of screenwriting edited by Paolo Russo and a book on the history of American screenwriting edited by Andy Horton. Not least, there was Eric Hoyt, whose “From Narrative to Nodes” showed how digitized screenplays could be used to graph character action and interaction over time. (A nice moment: When asked if his analytic could be rendered in real time, he clicked a button, and the thing moved.) Once more we’re in the x-y axes of Emmerdale and In the Year of the Pig, but now in cyberspace. Eric’s results on Kasdan’s Grand Canyon appears here on the right, but only as an enigmatic tease; he will be contributing a guest blog here later this fall.

In other words, you should have been here. Next time: October in Potsdam, under the auspices of Kerstin Stutterheim at the Hochshule für Film und Fernsehen “Konrad Wolf.” DB was at this magnificent facility last year for another event, and we’re sure–to coin a phrase–a hell of a time will be had by all.

Thanks very much to J. J. and Kelley, as well as to Vance Kepley, Mary Huelsbeck, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey of the WCFTR. Special thanks to Erik Gunneson, Mike King, Linda Lucey, Jason Quist, Janice Richard, Peter Sengstock, Michael Trevis, and all the other departmental staff that helped make this conference a big success.

Thanks also to Noah Ollendick, age 12, who asked a smart question.

P.S. 4 Sept: Thanks to Ben Brewster for a correction!

J.J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, conference coordinators.

A behemoth from the Dead Zone

DB here:

The first quarter of the year is the biggest slump time for movie theatres. (1) Holiday fatigue, thin budgets, bad weather, the Super Bowl, and the distractions of the awards season depress admissions. If people go to the movies, they tend to catch up on Oscar nominees, and studios don’t want to release high-end films that might suffer from the competition. But screens need fresh product every week, so most of what gets released at this time of the year might charitably be called second-tier.

Ambitious filmmakers fight to keep out of this zone of death. You could argue that the January release slot of Idiocracy told Mike Judge exactly what Fox thought of that ripe exercise in misanthropy. Zodiac, one of the best films of 2007, opened on 1 March, and even ecstatic reviews couldn’t push it toward Oscar nominations. You can imagine what chances for success Columbia has assigned to Vantage Point (a 22 February bow). [But see my 4 Feb. PPPS below.]

Yet this is a flush period for those of us who like to explore low-budget genre pieces. I have to admit I enjoy checking on those quickie action fests and romantic comedies that float up early in the year. They’re today’s equivalent of the old studios’ program pictures, those routine releases that allowed theatres to change bills often. In their budgets, relative to blockbusters, today’s program pix are often the modern equivalent of the studios’ B films.

More important, these winter orphans are often more experimental, imaginative, and peculiar than the summer blockbusters. On low budgets, people take chances. Some examples, not all good but still intriguing, would be Wild Things (1998), Dark City (1998), Romeo Must Die (2000), Reindeer Games (2000), Monkeybone (2001), Equilibrium (2002), Spun (2003), Torque (2004), Butterfly Effect (2004), Constantine (2005), Running Scared (2006), Crank (2006), and Smokin’ Aces (2007). The mutant B can be found in other seasons too—one of my favorites in this vein, Cellular (2004), was released in September—but they’re abundant in the year’s early months.

By all odds, Cloverfield ought to have been another low-end release. A monster movie with unknown players, running a spare 72 minutes sans credits, budgeted at a reputed $25 million, it’s a paradigm of the winter throwaway. Except that it pulled in $46 million over a four-day weekend and became the highest-grossing film (in unadjusted dollars) ever to be released in January. Here the B in “B-movie” stands for Blockbuster.

I enjoyed Cloverfield. It starts with a sharp premise, but as ever, execution is everything. I see it as a nifty digital update of some classic Hollywood conventions. Needless to say, many spoilers loom ahead.

If you find this tape, you probably know more about this than I do

Everybody knows by now that Cloverfield is essentially Godzilla Meets Handicam. A covey of twentysomethings are partying when a monster attacks Manhattan, and they try to escape. One, Rob, gets a phone call from his off-again lover Beth, who’s trapped in a high-rise. He vows to rescue her. He brings along some friends, one of whom documents their search with a video camera. It’s a shooting-gallery plot. One by one, the characters are eliminated until we’re down to two, and then. . . .

Cloverfield exemplifies what narrative theorists call restricted narration. (Kristin and I discuss this in Chapter 3 of Film Art.) In the narrowest case of restricted narration, the film confines the audience’s range of knowledge to what one character knows. Alternatively, as when the characters are clustered in the same space, we’re restricted to what they collectively know. In other words, you deny the viewer a wider-ranging body of story information. By contrast, the usual Godzilla installment is presented from an omniscient perspective, skipping among scenes of scientists, journalists, government officials, Godzilla’s free-range ramblings, and other lines of action. Instead, Cloverfield imagines what Godzilla’s attack would look and feel like on the ground, as observed by one group of victims.

Horror and science fiction films have used both unrestricted and restricted narration. A film like Cat People (1942) crosscuts what happens to Irena (the putative monster) with scenes involving other characters. Jurassic Park and The Host likewise trace out several plot strands among a variety of characters. The advantage of giving the audience so much information is that it can feel apprehension and suspense about what the characters don’t know is happening. Our superior knowledge can make us worry about those poor victims oblivious to their fate.

But these genres have relied on restricted narration as well. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is a good example; we are at Miles’s side in almost every scene, learning of the gradual takeover of his town as he does. Night of the Living Dead (1968), Signs (2002), and War of the Worlds (2005) do much the same with a confined group, attaching us to one or the other momentarily but never straying from their situation.

The advantages of restricted narration are pretty apparent. You can build up uncertainty and suspense if we know no more than the character(s) being attacked by a monster. You can also delay full revelation of the creature, a big deal in these genres, by giving us only the glimpses of it that our characters get. Arguably as well, by focusing on the characters’ responses to their peril, you have a chance to build audience involvement. We can feel empathy and loss if we’ve come to know the people more intimately than we know the anonymous hordes stomped by Godzilla. Finally, if you need to give more wide-ranging information about what’s happening outside the characters’ immediate situation, you can always have them encounter newspaper reports, radio bulletins, and TV coverage of action occurring elsewhere.

People sometimes think that theoretical distinctions like this overintellectualize things. Do filmmakers really think along these lines? Yes. Matt Reeves, the director of Cloverfield, remarks:

The point of view was so restricted, it felt really fresh. It was one of the things that attracted me [to this project]. You are with this group of people and then this event happens and they do their best to understand it and survive it, and that’s all they know.

For your eyes only

Restricted narration doesn’t demand optical point-of-view shots. There aren’t that many in Invasion of the Body Snatchers or the other examples I’ve indicated. Still, for quite a while and across a range of genres, filmmakers have imagined entire films recording a character’s optical/ auditory experience directly, in “first-person,” so to speak.

Again, it’s useful to recognize two variants of this narrational strategy. One we can call immediate—experiencing the action as if we stood in the character’s shoes. In the late 1920s, the great documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens tried to make what he called his I-film, which would record exactly what a character saw when riding a bike, drinking a glass of beer, and the like. He was dismayed to find that bouncing and swiveling the camera as if it were a human eye ignored the fact that in real life, our perceptual systems correct for the instabilities of sensation. Ivens abandoned the project, but evidently he couldn’t get the notion out of his head; he called his autobiography The Camera and I. (2)

Hollywood’s most strict and most notorious example of directly subjective narration is Robert Montgomery’s Lady in the Lake (1947). Its strangeness reminds us of some inherent challenges in this approach. How do you show the viewer what your protagonist looks like? (Have him pass in front of mirrors.) How do you skip over the boring bits? (Have your hero knocked unconscious from time to time.) How do you hide the inevitable cuts? (Try your best.) Even Montgomery had to treat the subjective sequences as long flashbacks, sandwiched within scenes of the hero in his office in the present telling us what he did next.

Because of these problems, a sustained first-person immediate narration is pretty rare. The best compromise, exploited by Hitchcock in many pictures and especially in Rear Window (1954), is to confine us to a single character’s experience by alternating “objective” shots of the character’s action with optical point-of-view shots of what s/he sees.

What I’m calling immediate optical point of view is just that: sight (and sounds) picked up directly, without a recording mechanism between the story action and the character’s experience. But we can also have mediated first-person point of view. The character uses a recording technology to give us the story events.

In a brilliant essay on the documentary Kon-Tiki (1950), André Bazin shows that our knowledge of how Thor Heyerdahl filmed his raft voyage lends an unparalleled authenticity to the action. Heyerdahl and his crew weren’t experienced photographers and seem to have taken along the 16mm camera as an afterthought, but the very amateurishness of the enterprise guaranteed its realism. Its imperfections, often the result of hazardous conditions, were themselves testimony to the adventure. When the men had to fight storms, they had no time to film; so Bazin is able to argue, with his inimitable sense of paradox, that the absence of footage during the storm is further proof of the event. If we were given such footage, we might wonder if it was staged afterward.

How much more moving is this flotsam, snatched from the tempest, than would have been the faultless and complete report offered by an organized film. . . . The missing documents are the negative imprints of the expedition. (3)

What about fictional events? In the 1960s we started to see fiction films that presented themselves as recordings of the events as the camera operator experienced them. One early example is Stanton Kaye’s Georg (1964). The first shot follows some infantrymen into battle, but then the framing wobbles and the camera falls to earth. We see a tipped angle on a fallen solider and another infantryman approaches.

He bends toward us; the frame starts to wobble and we are lifted up. On the soundtrack we hear, “I found my camera then.”

The emergence of portable equipment and cinema-verite documentary seems to have pushed filmmakers to pursue this narrational mode in fiction. One result was the pseudo-documentary, which usually doesn’t present the story as a single person’s experience but rather as a compilation of first-person observations. Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1967) presents itself as a documentary shot during a nuclear war, and it contains many of the visual devices that would come to be associated with the mediated format—not only the flailing camera but the face-on interview and the chaotic presentation of violent action. There’s also the pseudo-memoir film, pioneered in David Holzman’s Diary (1967). Later examples of the pseudo-documentary are Norman Mailer’s Maidstone (1971) and the combat movie 84 Charlie MoPic (1989). (4)

As lightweight 16mm cameras made filming easier, directors adapted that look and feel to fictional storytelling. The arrival of ultra-portable digital cameras and cellphones has launched a similar cycle. Brian DePalma’s Redacted (2007), yet another war film, has exploited the technology for docudrama. A digital equivalent of David Holzman’s Diary, apart from Webcam and YouTube material, is Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), which I discussed here.

Interestingly, Orson Welles pioneered both the immediate and the mediated subjective formats. One of his earliest projects for RKO was an adaptation of Heart of Darkness, in which the camera was to represent the narrator Marlowe’s optical perspective throughout. (5) Welles had more success with the mediated alternative, though in audio form. His “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast mimicked the flow of programming and interrupted it with reports of the aliens’ attack. The device was updated for television in the 1983 drama Special Bulletin.

Sticking to the rules

Cloverfield, then, draws on a tradition of using technologically mediated point-of-view to restrict our knowledge. Like The Blair Witch Project (1999), it does this with a horror tale. But it’s also a Hollywood movie, and it follows the norms of that moviemaking mode. So the task of Reeves, producer J. J. Abrams, and the other creators is to fit the premise of video recording to the demands of classical narrative structure and narration. How is this done?

First, exposition. The film is framed as a government SD video card (watermarked DO NOT DUPLICATE), the remains of a tape recovered from an area “formerly known as Central Park.” This is a modern version of the discovered-manuscript convention familiar from the nineteenth-century novel. When the tape starts, showing Rob with Beth in happy times, its read-out date of April plays the role of an omniscient opening title. In the course of the film, the read-outs (which come and go at strategic moments) will tell us when we’re in the earlier phase of their love affair and when we’re seeing the traumatic events of May.

Likewise, the need for exposition about characters and relationships at the start of the film is given through a basic premise. Jason wants to record Rob’s going-away-party and he presses Rob’s friend Hud into service as the cameraman. Off the bat, Hud picks out our main characters in video portraits addressed to Rob. What follows indicates that Hud will be amazingly prescient: His camera dwells on the characters who will be important in the ensuing action.

Next, overall structure. The Cloverfield tape conforms to the overarching principles that Kristin outlines in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and that I restated in The Way Hollywood Tells It. (Another example can be found here.) A 72-minute film won’t have four large-scale parts, most likely two or three. As a first approximation, I think that Cloverfield breaks into:

*A setup lasting about 30 minutes. We are introduced to all the characters before the monster attacks. Our protagonists flee to the bridge, where Jason dies. Near the end of this portion, Rob gets a call from Beth, and he formulates the dual goals of the film: to escape from the creature, and to rescue Beth. Along the way, Hud declares he’s going to record it all: “People are gonna know how it all went down. . . . It’s gonna be important.”

*A development section lasting about 22 minutes. This is principally a series of delays. Rob, Hud, Lily, and Marlena encounter obstacles. Marlena falls by the wayside. They are given a deadline: At 0600 they must meet the last helicopters leaving Manhattan.

*A climax lasting about 20 minutes. The group rescues Beth and meets the choppers, but the one carrying Rob, Hud, and Beth falls afoul of the beast. They crash in Central Park, and Hud is killed, his camera recording his death at the jaws of the monster. Huddled under a bridge, Rob and Beth record a final video testimonial before an explosion cuts them off.

*An epilogue of one shot lasting less than a minute: Rob and Beth in happier times on the Ferris wheel at Coney Island—a shot left over from the earlier use of the tape in April.

Next, local structure and texture. It takes a lot of artifice to make something look this artless. The imagery is rich and vivid, the sharpest home video you ever saw. The sound is pure shock-and-awe, bone-rattling, with a full surround ambience one never finds on a handicam. (6) Moreover, Hud is remarkably lucky in catching the turning points of the action. All the characters’ intimate dramas are captured, and Hud happens to be on hand when the head of Miss Liberty hurtles down the street.

Bazin points out that in fictional films the ellipses are cunning gaps, carefully designed to fulfill narrative ends—not portions left out because of the physical conditions of the shoot. Here the cunning gaps are justified as constrained by the physical circumstances of filming. When Hud doesn’t show something, it’s usually because it’s what the genre considers too gross, so the worst stretches take place in darkness, or offscreen, or strategically shielded by a prop when the camera is set down.

Mostly, though, Hud just shows us the interesting stuff. He turns on the camera just before something big happens, or he captures a disquieting image like that of the empty Central Park carriage.

At least once, the semi-documentary premise does yield something evocative of the Kon-Tiki film. Hud has to leap from one building to another, many stories above the street. He turns the camera on himself: “If this is the last thing you see, then I died.” He hops across, still running the camera, but when a rocket goes off nearby, a sudden cut registers his flinch. For an instant out of sheer reflex, he turned off the camera.

Overall, Hud’s tape respects the flow of classical film style. Unlike the Lady in the Lake approach, the mediated POV format doesn’t have a problem with cuts; any jump or gap is explained as a moment when the operator switched off the camera. Most of Hud’s “in-camera” cuts are conventional ones, skipping over a few inconsequential stretches of time. There are as well plenty of hooks between scenes. (For more on hooks, go here.) Hud says: “I’ll walk in the tunnels.” Cut to characters walking in the tunnels. More interestingly, visible cuts are rare, which again respects the purported conditions of filming. Cloverfield has much longer takes than any recent Hollywood film I know. I counted only about 180 shots, yielding an average of 24 seconds per shot (in a genre in which today’s films average 2-5 seconds per shot).

The digital palimpsest

We could find plenty of other ways in which Cloverfield adapts the handicam premise to the Hollywood storytelling idiom. There are the product placements that just happen to be part of these dim yuppies’ milieu. There are the character types, notably the sultry Marlena and the hero’s weak friend who’s comically a little slow. There’s the developing motif of the to-camera addresses, with Rob and Beth’s final monologues to the camera counterbalancing the party testimonials in the opening. There’s the final romantice exchange: “I love you.” “I love you.” The very last shot even includes a detail that invites us to re-view the entire movie, at the theatre or on DVD. But let me close by noting how some specific features of digital video hardware get used imaginatively.

I’ve already mentioned how the viewfinder date readout allows us to keep the time structure clear. There’s also the use of a night-vision camera feature to light up those spidery parasites shucked off by the big guy. Which scares you more—to glimpse the pinpoint eyes of critters skittering around you in the dark, or to see them up close in a sickly green light?

More teasing is the fact, set up in the first part, that this video is being recorded over an old tape of Rob’s. That’s what turns the opening sequence of Rob and Beth in May into a prologue: the tape wasn’t rewound completely for recording the party. Later, at intervals, fragments of that April footage reappear, apparently through Hud’s inadvertently advancing the tape. The snippets functions as flashbacks, showing Rob and Beth going to Coney Island and juxtaposing their enjoyable day with this horrendous night.

Cleverly, on the tape that’s recording the May disaster something always prepares the audience for the shift. For instance, when Jason hands the camera over, we hear Hud say, “I don’t even know how to work this thing.” Cut to an April shot of Beth on the subway, suggesting that he’s advanced fast forward without shooting. Likewise, when Rob says, “I had a tape in there,” we cut to another April shot of Beth. As a final fillip, the footage taken in May halts before the tape ends, so we get the epilogue showing Rob and Beth on the Ferris wheel in April, emerging like figures in a palimpsest.

No less clever, but also a little poignant, is the use of the fallen-camera convention. It appears once when Beth has to be extricated from her bed. Hud sets the camera down by a concrete block in her bedroom, which conceals her agony. More striking is the shot when the camera, dropped from Hud’s hand, lies in the grass, and the autofocus device oscillates endlessly, straining to hold on his lifeless face.

In sum, the filmmakers have found imaginative ways of fulfilling traditional purposes. They show that the look and feel of digital video can refresh genre conventions and storytelling norms. So why not for the sequel show the behemoth’s attack from still other characters’ perspectives? This would mobilize the current conventions of the narrative replay and the companion film (e.g., Eastwood’s Iwo Jima diptych). Reeves says:

The fun of this movie was that it might not have been the only movie being made that night, there might be another movie! In today’s day and age of people filming their lives on their iPhones and Handycams, uploading it to YouTube. . . .

So the Dead Zone of January through March yields another hopeful monster. What about next month’s Vantage Point? The tagline is: 8 Strangers. 8 Points of View. 1 Truth. Hmmm. . . . Combining the network narrative with Rashomon and a presidential assassination. . . . Bet you video recording is involved . . . . See you there?

PS: At my local multiplex, you’re greeted by a sign: WARNING: CLOVERFIELD MAY INDUCE MOTION SICKNESS. I thought this was just the theatre covering itself, but I’ve learned that no recent movie, not even The Bourne Ultimatum, has had more viewers going giddy and losing their lunch. You can read about the phenomenon here, and Dr. Gupta weighs in here. My gorge can rise when a train jolts, but I had no problems with two viewings of Cloverfield, both from third row center.

Anyhow, it will be perfectly easy to watch on your cellphone. But we should expect to see at least one pirate version shot in a theatre by someone who’s fighting back the Technicolor yawn, giving us more Queasicam than we bargained for.

(1) The only period that rivals this slow winter stretch is mid-August to October, when genre fare gets pushed out to pick up on late summer business. [Added 26 January:] There are, I should add, two desirable weekends in the first quarter, those around Martin Luther King’s birthday and Presidents’ Day. Studios typically aim their highest-profile winter releases (e.g., Black Hawk Down, 2001) for those weekends.

(2) Joris Ivens, The Camera and I (New York: International Publishers, 1969), 42.

(3) André Bazin, “Cinema and Exploration,” What Is Cinema? Vol. 1, trans. and ed. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 162.

(4) Not all pseudodocumentaries present themselves as records of a person’s observation. Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart (1969) presents itself as an objective record, by a hidden camera, of a psychiatrist’s dealings with his patients. Like a surveillance camera, it doesn’t purport to embody anybody’s point of view.

(5) Jonathan Rosenbaum, Discovering Orson Welles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 28-48.

(6) For Kevin Martin’s informative account of the film’s polished lighting and high-definition video capture, go here (and scroll down a bit). For discussions of contemporary sound practices in this genre, see William Whittington’s Sound Design in Science Fiction (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007).

PS: Thanks to Corey Creekmur for correcting two slips in my initial post!

PPS 28 January: Lots of Internet buzz about the film since I wrote this. Thanks to everyone who linked to this post, and special thanks for feedback from John Damer and James Fiumara.

Some people have asked me to comment on the social and cultural implications of Cloverfield’s references to 9/11. At this point I think that genre cinema has dealt more honestly and vividly with the traumas and questioning around this horrendous event than the more portentous serious dramas like United 93, World Trade Center, and the TV show The Road to 9/11.

The two most intriguing post-9/11 films I know are by Spielberg. The War of the Worlds gives a really concrete sense of what a hysterical America under attack might be like, warts and all. (It reminded me of a TV show I saw as a kid, Alas, Babylon (1960), a surprisingly brutal account of nuclear-war panic in suburbia.) Spielberg’s underrated The Terminal reminds us, despite its Frank Capra optimism, that the new Security State is run by bureaucrats with fixed agendas and staffed by overworked people of color, some themselves exiles and immigrants.

I think that Cloverfield adds its own dynamic sense of how easily the entitlement culture of upwardly mobile twentysomethings can be shattered. Genre films carry well-established patterns and triggers for feelings, and a shrewd filmmaker can channel them for comment on current events—as we see in the changing face of Westerns and war films in earlier phases of Hollywood history.

On this point, Cinebeats offers some shrewd responses to criticisms of Cloverfield here.

Finally: In the new Creative Screenwriting an informative piece (not available online) indicates that the initial logline for Vantage Point on imdb is misleading. Screenwriter Barry Levy planned to present the assassination from seven points of view, but reduced that to six. As for my speculation that video recording/replay would be involved, a production still seems to offer some evidence. Shall we call it the Cloverfield effect? The same issue of CS has a brief piece on the script for Cloverfield.

Finally: In the new Creative Screenwriting an informative piece (not available online) indicates that the initial logline for Vantage Point on imdb is misleading. Screenwriter Barry Levy planned to present the assassination from seven points of view, but reduced that to six. As for my speculation that video recording/replay would be involved, a production still seems to offer some evidence. Shall we call it the Cloverfield effect? The same issue of CS has a brief piece on the script for Cloverfield.

PPS 30 January: Shan Ding brings me another story about the making of Cloverfield, and Reeves is already in talks for a sequel, says Variety.

PPPS 4 February: A recent story in The Hollywood Reporter offers a nuanced account of how Hollywood is rethinking its first-quarter strategies. Across the last 4-5 years, a few big releases have done fairly well between January and April; a high-end film looks bigger when there is less competition. The author, Steven Zeitchik, suggests that the heavy packing of the May-August period and the need for a strong first weekend are among the factors that will encourage executives to spread releases through the less-trafficked months. I hope, though, that tonier fare won’t crowd out the more edgy, low-end genre pieces that bring me in.

PPPPS 8 February: How often has a wounded Statue of Liberty featured in the apocalyptic scenarios of comics and the movies? Lots, it turns out. Gerry Canavan explains here.

Charlie, meet Kentaro

DB here:

Echoing an earlier virtual roundtable on this blog, I want to write about my two favorite B film series, now available in handsome DVD boxed sets. Both series were mounted at 20th Century-Fox, both were adapted from genre fiction, and both seem very much of their time: lots of exotic Orientalia, and probably too many middle-aged men in tiny mustaches and broad fedoras. But to my mind these films offer brisk, unpretentious entertainment, solidly crafted and surprisingly subtle. They also allow us to trace some changes in the ways movies were made across the 1930s.

There’s another reason for this blog. Tim Onosko, a friend of Kristin’s and mine, recently died after a battle with pancreatic cancer. Tim was an extraordinary figure, as you can find here. He was central to Madison film culture for forty years, and in his various creative activities, he shaped everything from The Velvet Light Trap to Tokyo Disneyland. He and his wife Beth also made a documentary, Lost Vegas: The Lounge Era. Tim and I enjoyed talking about the two series I’ll be mentioning. He loved these films, as he loved all films and popular culture generally, with a sharp-eyed dedication. So this is a small effort at an homage to Tim.

The Hawaiian and the Japanese

Charlie Chan, a Hawaiian police inspector of Chinese ancestry, became famous in a series of six novels by Earl Derr Biggers, from The House without a Key (1925) to The Keeper of the Keys (1932). Chan novels were brought to the screen at the end of the 1920s by Pathé and Universal, but for Behind That Curtain (1929) Fox took over the franchise. Warner Oland, a Swedish-born actor who had often played Asians, settled into the lead role in Charlie Chan Carries On (1931). He played Chan up through Charlie Chan at Monte Carlo (1937), then fled Hollywood under peculiar circumstances and went to Sweden, where he died soon afterward.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

The Mr. Moto films overlapped with the Oland cycle. John P. Marquand introduced Moto in the novel No Hero (1935) and made him more central to four novels that followed. Again, Fox bought the rights and launched the film series with Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). It starred Peter Lorre as the mysterious Japanese, and I think it’s fair to say that the role made him a Hollywood star. The series ran for eight installments, ending in 1939 with Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation.

Each series echoed its mate. Tim claimed that in an early Chan, a character is reading a Moto story in the Saturday Evening Post, though I’ve never found that scene. When Charlie’s Number One Son turns up to help Moto in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1938) it’s revealed that Charlie and Moto are old friends. There’s a more elegiac moment in Mr. Moto’s Last Warning (1939) when a theatre displays a poster for the Chan series—perhaps as well serving as an homage to the recently deceased Warner Oland. Despite Oland’s death, the Chan series continued until 1949, with Sidney Toler in the role, but with Lorre’s departure the Moto films ceased.