Archive for March 2016

Threefer

DB here:

First, there’s this:

http://isthmus.com/screens/movies/film-scholars-david-bordwell-and-kristin-thompson/

Thanks to Laura Jones and the Isthmus staff for this profile. Among the stills they didn’t use is one of Kristin and me with Robert Altman. I interviewed him for a screening of The Player at the Walker Art Center in 1992. Why waste the scan? I thought, so I put it below.

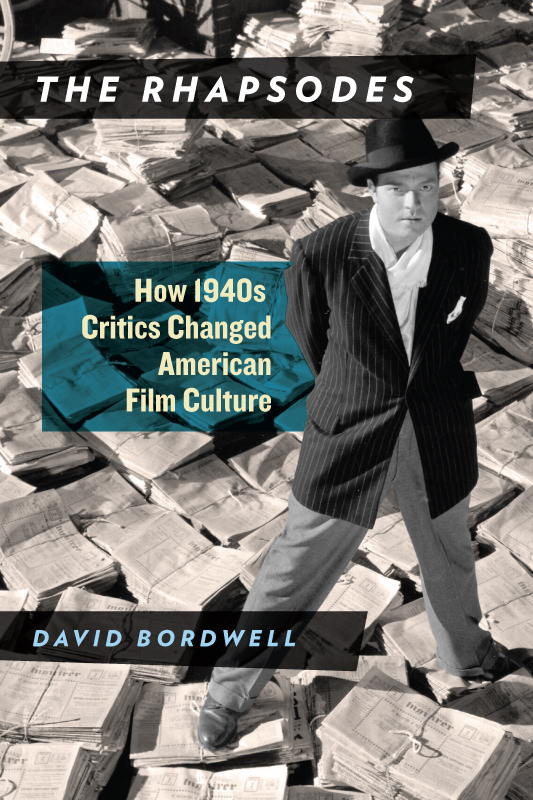

Second, there’s the pleasant fact that my book The Rhapsodes will be available on 4 April, Kristin’s birthday. It’s an essayistic study of four American film critics who, I think, prepared the way for the film-reviewing explosion of the 1960s.

I like to say that good film criticism offers not only opinions but information and ideas. Otis Ferguson, James Agee, Manny Farber, and Parker Tyler met that standard. The book tries to show that they had intriguing notions about American cinema and its aesthetic. They were superb writers as well. Although each man’s style was unique, they all wrote with a gleaming exuberance. The result, as the title suggests, is a controlled wildness, a quality captured I think in the book’s epigraph by Robert Lewis Stevenson:

In anything fit to be called by the name of reading, the process itself should be absorbing and voluptuous; we should gloat over a book, be rapt clean out of ourselves, and rise from the perusal, our mind filled with the busiest, kaleidoscopic dance of images, incapable of sleep or of continuous thought.

I’m very grateful to the University of Chicago Press, particularly my editor Rodney Powell, manuscript editor Kelly Finefrock-Creed, and Senior Promotions Manager Melinda Kennedy. Deep thanks as well to my initial readers Jim Naremore and Chuck Maland, and to the people who kindly endorsed the book: David Koepp, Manohla Dargis, and Philip Lopate.

More background on the book is here. I hope to offer some ideas about film criticism today in an upcoming entry.

Third, later this week Kristin and I are moving to Manhattan for three months. (Whoopee!) She’ll be working on her Amarna statuary project with her collaborator, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I’ll be doing research, mostly on Hollywood in the 1940s, while watching movies, seeing friends, and blogging. I’ll give some talks as well. One, presented at Sacred Heart University and at Tufts, is drawn from the 1940s book. I’ll discuss The Rhapsodes at the 92nd Street YMCA and the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria (details on the last yet to be finalized). Maybe I’ll see you at one of these get-togethers?

Photo: Walker Art Center, Minneapolis.

The BIFF imbroglio: Further developments and another communiqué from Tony Rayns

DB here:

The aggressive action taken by Busan’s mayor Suh Byung-soo to curtail programming at the city’s international film festival continues to have repercussions. A January post here reviewed the controversy, and a later one relayed the support offered to festival Co-Director Lee Yongkwan by the Rotterdam Film Festival. These entries include links that can supply backstory.

The reporting of Jean Noh at Screen Daily has covered some new developments. A 10 March panel concluded that the festival is “on the verge of being ruined.” Last week nine major Korean film organizations threatened a boycott if Mayor Suh does not withdraw from the festival board and apologize for his actions. The photo above is from that event. Things are getting hotter. Suh cut short a meeting to discuss revisions to the festival policies, and, as Noh reports:

Busan City has since filed an injunction against 68 newly appointed advisors to the festival including internationally renowned filmmakers such as Park Chan-wook (Stoker), Ryoo Seung-wan (Veteran), Choi Dong-hoon (Assassination) and top stars such as Ha Jung-woo (The Chaser) and Yoo Ji-tae (Old Boy).

At this juncture comes a piercing second Open Letter to the people of Busan from critic, filmmaker, and programmer Tony Rayns. You can read Kamikaze Mayor, a good-old-fashioned butt-stomping polemic, on Geoff Gardner’s Film Alert 101 website.

Busan International Film Festival, September 2015.

Our daily barbarisms: Leo Hurwitz’s STRANGE VICTORY (1948)

DB here:

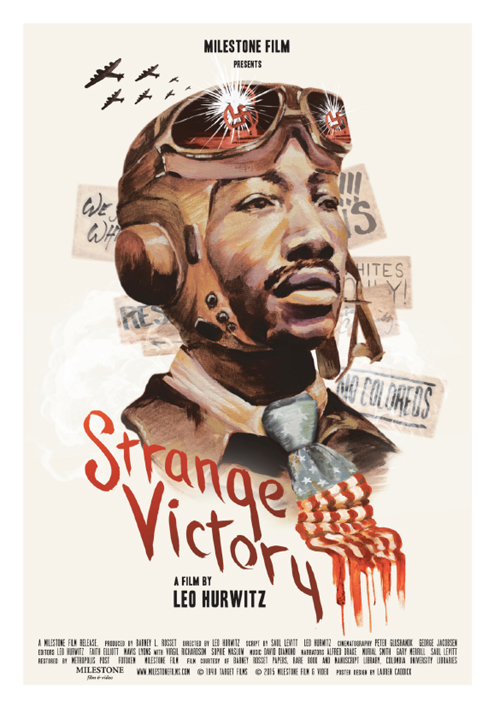

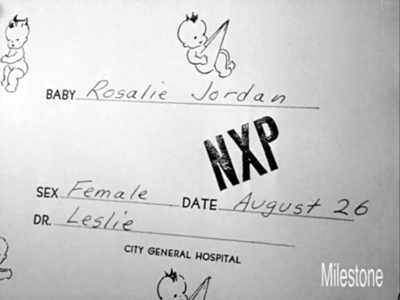

Leo Hurwitz is perhaps best known for Native Land (1942), the documentary codirected with Paul Strand and narrated by Paul Robeson. Strange Victory (1948) has been less easy to see. It was scarcely distributed and, though some reviews praised it, it was accused of Communistic sympathies. Now, restored and recirculated by the enterprising Milestone Films, Strange Victory has lost none of its compassion and righteous anger. Thanks to the energy of the Milestone team, led by A my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

my Heller and Dennis Doros, every citizen has a chance, say rather a duty, to see a film whose force is undiminished today.

In a period of postwar optimism, Hurwitz and his colleagues dared to point out that the prejudices exploited by the Nazis remained powerfully present in the United States. The winners, it seemed, hadn’t repudiated the bigotry of the losers. American racism persisted and even intensified. The Nazis lost, but a form of Nazism won.

Dec. 14, 2015, in Las Vegas. Individuals at a Trump rally yelled “Sieg Heil” and “Light the motherfucker on fire” toward a black protester who was being physically removed by security staffers.

News of the world

Like The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936), on which Hurwitz was cameraman, and the Why We Fight series, Strange Victory is largely a compilation documentary. Guided by voice-over narration, it ranges across newsreels of Hitler’s rise, chilling combat shots, and footage from the liberated death camps.

But Hurwitz and his team shot a lot of new material as well, with an eye to bringing out the postwar significance of their theme. Newborn babies eye the camera, and kids play on sidewalks and in backlots (some shots recall Helen Levitt’s evocative street photos). Meanwhile, anxious adults approach a newsstand. “If we won, why are we unhappy?” the narrator asks at the beginning. The question is answered at the end: “There was not enough victory to go around.”

Thanks to a hidden camera, that newsstand becomes a sort of gathering spot, a place where people might encounter uncomfortable truths. Intercut with people buying newspapers are images of battles, as if the hunger for news aroused by the war didn’t dissipate. But what is that news? Hurwitz introduces it quickly: the rise of nativist bigotry. In an eye-blink, racist decals are slapped on fences, synagogues are smashed, and vicious pamphlets swarm through the frame. Race-baiting politicians, radio hate-mongers, and fascist sympathizers–the 1940s equivalents of our celebrity demagogues–are pictured and named. This is just one of many passages that guaranteed that Strange Victory could never be circulated on mainstream theatre circuits.

Hurwitz mixes found footage, stills, posed images, and fully staged scenes, such as the episode in which a Tuskegee Airman tries to find a job with an airline. In this mixed strategy he follows not only the precedent of the March of Time series but also, and more self-consciously, the Soviet documentarist Dziga Vertov.

In a 1934 article, Hurwitz called The Man with a Movie Camera “the textbook of technical possibilities,” and he isn’t shy about mimicking the master. Early in the film, portraying the Allies’ victory, a shot shows a swastika-emblazoned building blown to bits in slow motion. Later, to convey the return of Hitlerism, the same shot is run backward, reinstating the swastika on the building’s roof. A graphically matched dissolve equates a Klan wizard with Southern senator John Elliott Rankin.

Later, via constructive editing à la Kuleshov, parental pride is made color-blind, as both a white mother and a black one return a father’s glance.

The film hasn’t aged a bit. The print is gorgeously subtle black and white, and the score by the underrated David Diamond is warm in a chamber-music way. The film’s vigorous voice-over and its ricocheting images (some returning as refrains, bearing new implications) look forward to the hallucinatory, expanding associations created by our most biting contemporary documentarist, Adam Curtis.

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

Shiya Nwanguma, a young African-American student at the University of Louisville, was shoved and verbally abused when she attempted to protest at the Trump event. “I was called a nigger and a cunt, and got kicked out,” Nwanguma said after the incident. “They were pushing and shoving at me, cursing at me, yelling at me, called me every name in the book. They’re disgusting and dangerous.”

One of the individuals involved in the confrontation with Nwanguma was Joseph Pryor, a native of Corydon, Indiana, who graduated from high school last year. After the rally, Corydon posted a photo on his Facebook page that showed him shouting at Nwanguma. The post went viral and eventually attracted the attention of the Marine Corps, which Pryor had just joined.

The Marine Corps recruiting station in Louisville told military publication Stars and Stripes that Pryor had recently enlisted and was about to head off for boot camp. Captain Oliver David, a spokesman for the Marine Corps command, said Pryor had not yet undergone Marine Corps ethics training. . . . He added: “Hatred toward any group of individuals is not tolerated in the Marine Corps and he is being discharged from our delayed entry program effective [Wednesday].”

The tyranny of facts

As ever, the ordering of parts matters greatly. How best to convey the idea that after a struggle to cleanse Europe of violent prejudice, the same attitude is flourishing in America? You might think of couching your argument as a narrative. In chronological order, that would be: The rise of Hitler; the war defeating Hitler; the celebration of victory; the return of American bigotry in the postwar period. Clear and straightforward.

Hurwitz is more canny. Many films embracing rhetorical form, like the problem/solution structure of Pare Lorentz’s The River (1938), will embed brief narratives into their overarching argument. This is Hurwitz’s approach, but his stories aren’t chronologically sequenced. Instead, we start with the America of today before flashing back to the high price of defeating the Axis. “Everybody paid,” says the male narrator. “Everybody.” With a pause to register Roosevelt’s death, jubilation surges up as the Nazis fall. “For a day or two, the plain people owned the world.” But then we’re back to the newsstand and a montage of race-baiters and graffiti scrawlers.

Then, as we see a pregnant woman on a bench, we hear a woman’s voice. Her poetic musings reassure the newborn babies that they have a place here; she welcomes them to earthly love. Following the montage of haters with images of innocence casts a melancholy pall over these fresh-begun lives. They know nothing of the American brownshirts, but we know that they must learn our world.

This foreboding is confirmed by a chorus of name-calling over shots of newborns, the woman’s song of innocence is undercut by a song of bitter experience. A new male narrator (Gary Merrill) raps out the facts of “our daily barbarisms.” Get ready, he warns the babies: You will be tagged and vilified by how you look and where you live. “Separation of people is a living fact,” and they are future “casualties of war.” Throughout the rest of the film, the shots of children carry a terrible aura; they have no idea of what they’re facing.

Now, after a long delay, we flash back to Hitler’s rise. The Führer’s strategy, funded by the rich, is seen as a deliberate mobilization of just these tribal “facts” for the sole end of acquiring power. And where that process ends is the death camp. In a chilling visual refrain, the happy American toddlers are compared to troops of children marched along barbed wire.

The narrative spirals back to the beginning. Again we see Hitler defeated, again ecstatic celebrations–but not, as before, among civilians in cities. Instead, we see Russian and American soldiers fraternizing, and included in this mix is the black pilot, smiling serenely in his cockpit. His presence was foreshadowed by swooping aerial shots of the beginning. Now we’re back to the present, and he’s looking for work. No luck; maybe he can be a porter? A new montage generalizes his plight: American society refuses to assimilate African Americans. A savage cut takes us from a room full of white secretaries to a cotton field–the only work available for people who participated as fully in the war effort as anyone.

Now the early montage of Jim Crow images is recalled in a poetic string of associations on the word word, from Hitler’s control of The Word to signs barring blacks from entry, ending with inscriptions etched on forearms.

The final images of passersby, filmed unawares, replace the newsstand of the opening with shop windows as they peer inside. The sequence uncannily predicts the explosive consumer society that would follow in the war’s wake. Again, though, a shadow falls over the postwar world. Hurwitz daringly intercuts the intent window-shoppers with the plunder of the camps–hair, jewelry–and the numbers on inmate uniforms, as if these were commodities on display.

The war against inhumanity is far from over. Americans will need to be more than curious consumers if they are to face the struggle that lies ahead.

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

16 March 2016. UW-Madison police are investigating an act of racist vandalism that was committed earlier this week on campus, officials confirmed Wednesday. The drawing, which was found in a men’s bathroom in the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, shows a stick figure hanging from a noose in a tree with the word “nigger” written next to it. UW police spokesman Marc Lovicott says the vandalism was reported at about 7:20 p.m. on Monday and is believed to have occurred some time between 3:30 and 7 p.m. that same day. (Photo by Marla DG on Twitter.)

Strange Victory is, it seems to me, the essential documentary of our moment. A nearly seventy-year-old film can remind us that, as the narration puts it, “hopelessness is next door to hysteria.” The frustrations, despair, and hatreds that surfaced during Obama’s tenure have crystallized in an American fascist movement of unprecedented breadth. The film reminds us that scapegoating is eternal, sometimes summoned quietly (they’re not like us, she’s a traitor, he knows exactly what he’s doing), sometimes conjured up in full fury. At a moment when America is one IS attack away from a Trump or Cruz presidency, it’s good to be reminded how the well-funded Hitler exploited Us vs. Them. Temporizing pundits give every sufficiently funded lunatic the benefit of straight-faced interviews, or even tongue-baths. Right-wing politicians and agitators, keen on power and uncommitted to principle, are ready to fall in line behind a leader if he might win. Forget Godwin’s Law. Facing today’s assault on peace and justice, Strange Victory can rekindle our energies, without a moment to lose.

The crematorium is no longer in use. The devices of the Nazis are out of date. Nine million dead haunt this landscape. Who is on the lookout from this strange tower to warn us of the coming of new executioners? Are their faces really different from our own? Somewhere among us, there are lucky Kapos, reinstated officers, and unknown informers. There are those who refused to believe this, or believed it only from time to time. And there are those of us who sincerely look upon the ruins today, as if the old concentration camp monster were dead and buried beneath them. Those who pretend to take hope again as the image fades, as though there were a cure for the plague of these camps. Those of us who pretend to believe that all this happened only once, at a certain time and in a certain place, and those who refuse to see, who do not hear the cry to the end of time.

Milestone, who gave us the restored Portrait of Jason, has provided a very full presskit for Strange Victory here. My final quotation comes from Jean Cayrol’s text for Night and Fog (1955).

Strange Victory (1948).

Weaponized VOD, at $50 a pop

Ant-Man 2: This time it’s personal. Not that it wasn’t before. But now it’s personal and expensive.

DB here:

Sean Parker, the Napster founder who taught everybody that digital piracy means never having to say you’re sorry, has come up with a new killer app. Called The Screening Room, the pitch is catching the eye of an industry that thrives on finding new niches for its product.

Stuff you probably already know

Recall, as background, that Hollywood’s economic model depends on two conditions.

(1) Strong Intellectual Property measures, both technological and legal. (Intellectual is to be taken in a broad sense here. It includes Paul Blart movies.) Encryption is designed to protect DVDs, streaming, and the Digital Cinema Package that plays in your local multiplex. Law enforcement, under the auspices of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, backs up anti-piracy with fines and jail time.

(2) Price discrimination. The premise of the classic vertically-integrated studio system was that people will pay more to see a movie sooner than other people. Why this is true still mystifies me, but facts are facts. Hence the old system of “runs.” First-run movies demanded top dollar, then second runs were at lower prices, and subsequent runs were still cheaper. When the studios surrendered their theatre ownership, the runs system remained roughly in place, chiefly because most films were platform released, playing the big cities before gradually expanding to the provinces. And network TV was basically the only ancillary market. But wide releases–hundreds or even thousands of copies playing everywhere–became the industry norm as cable, home video, and other technologies came along. The run system was reborn, and price discrimination became much more fine-grained.

Known, confusingly, as “windows,” phases of the film’s life are assigned to various platforms. After the theatrical window, typically 90 days after release, there are windows for airline/hotel access, disc (DVD, Blu-ray), Pay-per-View, streaming, cable, and on down the line. The order of these windows for any one title can vary somewhat, depending on negotiations. Most of them are designed to define price points scaled along a curve: how much it’s worth to somebody to see the movie at intervals after the initial theatrical release. By the time a movie comes to free cable, you’ve pretty much squeezed everything out of it, though the industry relies very extensively on worldwide cable purchases.

The studios depend on the theatrical release, but not because it’s the biggest source of revenue. (For the top films it can yield a lot, of course, but most films don’t recoup their costs in that window.) The theatrical release builds awareness, making it stand out downstream in the ancillaries. Without theatrical release, a film needs a lot of publicity to draw notice. Witness all those films on your Netflix or Hulu menu, all those John Cusack movies you didn’t know existed.

Independent films are increasingly relying on day-and-date release between a mild theatrical run and some form of Video on Demand. Other indie titles, along with foreign ones, are going wholly VOD, and the big players–Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon–are vigorously buying titles and backing new projects against the looming day when the studios will license fewer blockbusters to them.

The studios need the theatre chains as a shop window for their top-tier product. The theatre chains obviously need the studios to keep crowds flowing in. But some parties have flirted with day-and-date theatrical/VOD. Most famously Ted Sarandos of Netflix argued for it in 2013, then had to backtrack a few days later. On the studio end, Universal in 2011 proposed softening the theatrical window by offering Tower Heist on “premium VOD.” The plan was to drastically cut into the theatrical window by making the film available after three weeks of release, for the hefty price of $59.95. Theatre owners threatened to boycott the film, and filmmakers howled in protest. Many feared that it was the thin edge of a wedge that would eventually, through price wars, shorten windows and lower prices–not to mention wreck theatre attendance. The idea was quickly dropped.

No bad idea ever goes away, as we learn from claims that tax cuts create jobs and that we’re just one intervention away from creating peace in the world. Thanks to Parker, we now have Premium VOD in a new guise. That means a new window, with corresponding price discrimination.

Premium VOD, steroidal

Last week, The Screening Room project, sponsored by Parker and entrepreneur Prem Akkaraju, was made public. Brent Lang of Variety outlined the plan circulating among the major players.

Individuals briefed on the plan said Screening Room would charge about $150 for access to the set-top box that transmits the movies and charge $50 per view. Consumers have a 48-hour window to view the film.

To get exhibitors on board, the company proposes cutting them in on a significant percentage of the revenue, as much as $20 of the fee. As an added incentive to theater owners, Screening Room is also offering customers who pay the $50 two free tickets to see the movie at a cinema of their choice. That way, exhibitors would get the added benefit of profiting from concession sales to those moviegoers.

Participating distributors would also get a cut of the $50-per-view proceeds, also believed to be 20%, before Screening Room took its own fee of 10%.

Parker assures all stakeholders that the magic box would assure maximum antipiracy controls.

Since then, developments have been swift. Peter Jackson, Ron Howard, and J.J. Abrams are supporting the plan, while James Cameron is opposing it. The Cinemark and Regal chains, at this point the biggest theatre chains in the country, are against it, but there are hints that AMC, soon to be the biggest chain in the world if it’s allowed to purchase Carmike, might be interested. As for studios, Universal, Sony, and Fox are rumored to be considering the prospect. Once the give-and-take of dealmaking gets under way, there’s no telling what a final arrangement might look like.

What’s transparently clear is the opposition of the art-house sector. Tim League of Alamo Drafthouse issued the first warning on Monday, calling The Screening Room a “half-baked” idea. Today the Art House Convergence, an association of 600 theatres, issued a severe criticism of Parker’s plan. The open letter has been summarized in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. Indiewire has published it in its entirety, and I do the same, as follows.

The Art House Convergence, a specialty cinema organization representing 600 theaters and allied cinema exhibition businesses, strongly opposes Screening Room, the start-up backed by Napster co-founder Sean Parker and Prem Akkaraju. The proposed model is incongruous with the movie exhibition sector by devaluing the in-theater experience and enabling increased piracy. Furthermore, we seriously question the economics of the proposed revenue-sharing model.

We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model, nor are we arguing for the decrease in home entertainment availability for customers – most independent theaters already play alongside VOD and Premium VOD, and as exhibitors, we are acutely aware of patrons who stay home to watch films instead of coming out to our theaters.

Rather, we are focused on the impact this particular model will have on the cinema market as a whole. We strongly believe if the studios, distributors, and major chains adopt this model, we will see a wildfire spread of pirated content, and consequently, a decline in overall film profitability through the cannibalization of theatrical revenue. The theatrical experience is unique and beneficial to maximizing profit for films. A theatrical release contributes to healthy ancillary revenue generation and thus cinema grosses must be protected from the potential erosion effect of piracy.

The exhibition community was required to subscribe to DCI-compliance in a very material way – either by financing through VPF integrators (and those contracts have not yet expired) or by turning to other models which necessitated substantial time and commitment. Those exhibitors who were unable to make the transition were punished by a loss of product. The digital conversion had a substantial cost per theater, upwards of $100,000 per screen, all in the name of piracy eradication and lowering print, storage and delivery costs to benefit the distributors. How will Screening Room prevent piracy? If studios are concerned enough with projectionists and patrons videotaping a film in theaters that they provide security with night-vision goggles for premieres and opening weekends, how do they reason that an at-home viewer won’t set up a $40 HD camera and capture a near-pristine version of the film for immediate upload to torrent sites?

This proposed model would negate DCI-compliance by making first-run titles available to anyone with the set-top device for an incredibly low fee – how will Screening Room prevent the sale of these devices to an apartment complex, a bar owner, or any other individual or company interested in creating their own pop-up exhibition space? We must consider how the existing structures for exhibition will be affected or enforced, including rights fees, VPFs and box office percentages.

A model like this will also have a local economic impact by encouraging traditional moviegoers to stay home, reducing in-theater revenue and making high-quality pirated content readily available. This loss of revenue through box office decline and piracy will result in a loss of jobs, both entry level and long-term, from part time concessions and ticket-takers to full time projectionists and programmers, and will negatively impact local establishments in the restaurant industry and other nearby businesses. How many of today’s filmmakers started their careers at their local moviehouse?

There are many unanswered questions as to how this business model will actually work. The proposed model, as we have read in countless articles, suggests exhibitors will receive $20 for each film purchased. At first glance, an exhibitor may think it represents a small, but potentially steady, additional revenue stream. But how will this actually be divided among the number of theaters playing the purchased title; will exhibitors who open the title receive more than an exhibitor who does not get the title until several weeks later (based on a distributor’s decision); who will audit the revenue to ensure exhibitors are being paid fairly; does this revenue come from Screening Room or from the distributor… these are just a few of the issues yet to be explained.

Similarly, Screening Room promises to give each subscriber two free cinema tickets with each film purchase. Yet to be disclosed is how an exhibitor will recoup the value of those tickets from Screening Room so they can then pay the percentage of box office revenue owed to the distributor of the film. Yet to be explained is who will manage the ticket program details such as location choice, method of purchase, and so on. Will all exhibitors be expected to honor Screening Room free tickets, or will some exhibitors receive preferential treatment over others?

We strongly urge the studios, filmmakers, and exhibitors to truly consider the impact this model could have on the exhibition industry. We as the Art House and independent community have serious concerns regarding the security of an at-home set-top box system as well as the transparency and effectiveness of the revenue-sharing model. Our exhibition sector has always welcomed innovation, disruption and forward-thinking ideas, most especially onscreen through independent film; however, we do not see Screening Room as innovative or forward-thinking in our favor, rather we see it as inviting piracy and significantly decreasing the overall profitability of film releases.

At this time and with the information available to us we strongly encourage all studios to deny all content to this service.

One point of clarification. Some reports have interpreted the paragraph beginning “We are not debating the day-and-date aspect of this model…” as meaning that art-house programmers, managers, and owners are okay with day-and-date VOD. But many Art Housers wish that day-and-date VOD had been strangled in its cradle. For those people, “not debating” doesn’t mean “accepting” or “not disputing.” It means that this is not the occasion for taking issue with that feature of the concept, as the Parker proposal introduces serious problems of its own.

The churn around this proposal is turbulent; stories kept popping up as I was writing the entry. A useful update is here. To keep up to speed, you may want to visit these two summative links, one for Variety and the other for The Hollywood Reporter.

There were, and are, still second-run movie houses. To my joy, Ant-Man, released last summer, has been playing for at least seven months at our second-run house here in Madison. And in 35! Is this a record in modern times? Also, too: My Ant-Man image up top comes from the first film, not the sequel, which doesn’t yet exist. I was just fooling and pretending.

What’s the Art House Convergence? Visit their site here. My visit to their annual confab is recorded here. An updated version is available in Pandora’s Digital Box.