Archive for the 'Film technique: Staging' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

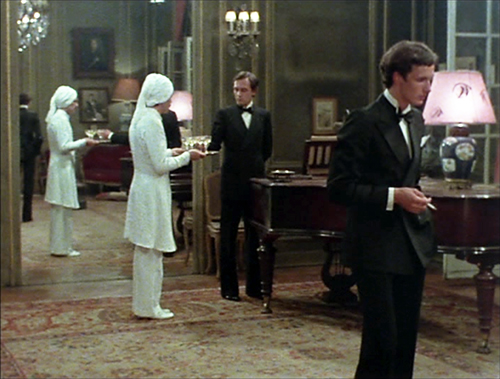

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

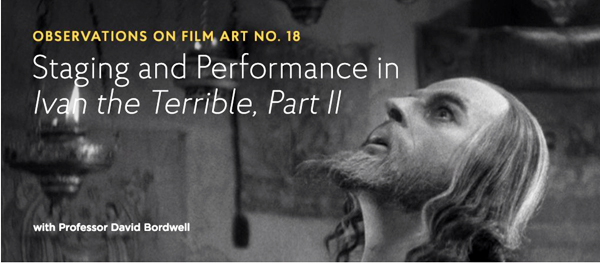

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

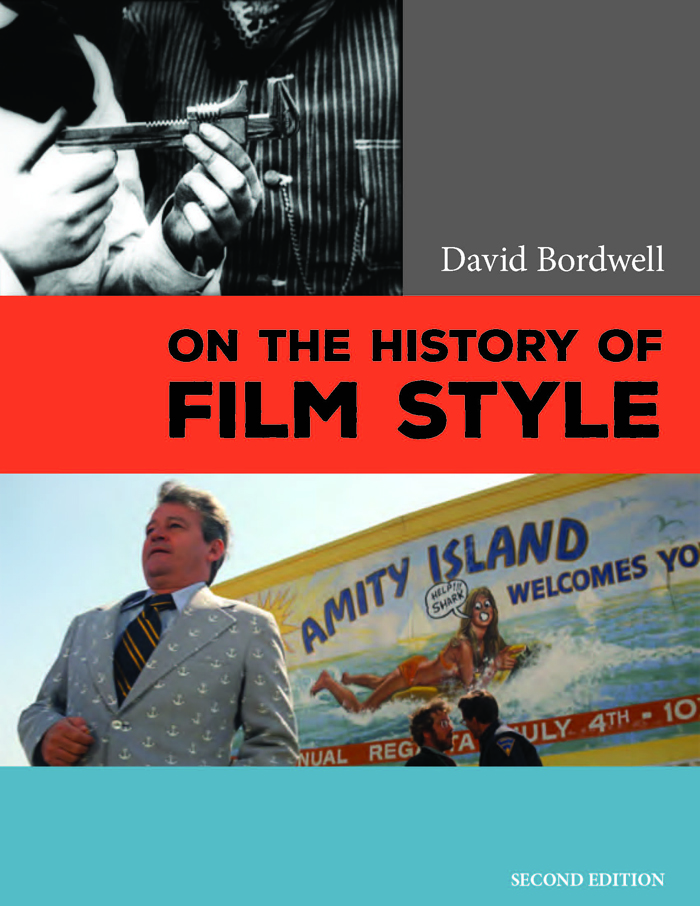

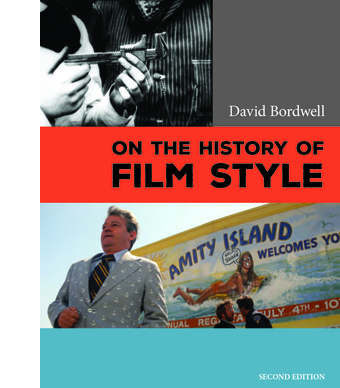

ON THE HISTORY OF FILM STYLE goes digital

Dust in the Wind (1986).

DB here:

I was born to write this book.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

Baby-boomer narcissism aside, there are more objective reasons for me to tell you about the book’s revival. It came out in late 1997 from Harvard University Press, and it went out of print last fall. Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel, it has become an e-book, like Planet Hong Kong, Pandora’s Digital Box, and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

The new edition is substantially the original book; the pdf format we used didn’t permit a top-to-bottom rewrite. Errors and some diction are corrected, though, and the color films I discuss are illustrated with pretty color frames, not the black-and-white ones in the first edition. The new Preface and a more expansive Afterword explain the origins of the book and develop ideas that I pursued in later research.

The book analyzes three perspectives on film style as they emerged historically. One, what I call the Basic Version, was developed in the silent era and saw the discovery of editing as the natural development of film technique.

The second version, associated with critic André Bazin, modified that conception by stressing the importance of other stylistic choices, notably long takes and staging in depth. I call this the Dialectical Version because Bazin claimed that these techniques were in “dialectical” tension with the pressures toward editing.

A third research program, spearheaded by filmmaker and theorist Noël Burch, argued that the development of film style was best understood as the ongoing interplay between two tendencies. There’s a dominant style Burch called the Institutional Mode. Responses to that mode are crystallized in alternative practices–the cinema of Japan, for instance, or the “crest-line” of major works associated with modernist trends.

The book goes on to show how a revisionist research program launched in the 1970s built upon these earlier perspectives. Younger scholars sought to answer more precise questions about certain periods and trends. The revisionist impulse is best seen in debates on early cinema, which I survey.

The book so far is historiographic, tracing out other writers’ arguments about continuity and change in film style. In my last chapter I try to do some stylistic history myself. I analyze particular patterns of continuity and change in one technique, depth staging. Certain conceptual tools, like the problem/solution couplet and the idea of stylistic schemas, can shed light on how certain staging options became normalized in various times and places. In turn, directors like Marguerite Duras, in India Song (1975), can revise those norms for specific purposes.

On the History of Film Style was generally well-received. John Belton, while voicing reservations, called it “a very good book. Anyone seriously interested in Film Studies should read it.” Michael Wood wrote in a review that “Bordwell is always sharp and often funny” (I try, anyhow) and called the last section “a brilliant account of the history of staging in depth.” The book has been used in some courses, and I’m happy to learn that there are filmmakers who find it useful. It’s been translated into Korean, Croation, and Japanese.

The book is available for purchase on this page. It’s priced at $7.99, a middling point between our other e-pubs. It’s a bigger book than Pandora ($3.99) and the Nolan one ($1.99), but it’s not an elaborate overhaul like Planet Hong Kong 2.0 ($15). Selling the book helps me defray the costs of paying Meg and digging up color frames. In any event, the new version is much cheaper than the old copies available at Amazon. It’s almost exactly the price of two Starbucks Caffe Lattes (one Grande, one Venti).

The archives and festivals that made the book possible are thanked inside, and they’ve continued to be hospitable and encouraging over the last two decades. Equally supportive are the students, colleagues, and cinephile friends with whom I’ve discussed these issues. So I reiterate my thanks to them all. And I hope this new edition, if nothing else, stimulates both viewers and researchers to explore the endlessly interesting pathways of visual style in cinema.

La Mort du Duc de Guise (1908).

Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part II on the Criterion Channel

For Yuri Tsivian

DB here:

Everyone knows Eisenstein as a theorist and practitioner of something called montage, which in his hands comes to mean a lot of things. But he was no less interested in what he called expressive movement. He believed that the viewer could be aroused by dynamic physical action that carried powerful feeling. Expressive movement pervades the set-pieces of his silent films. On the Odessa Steps of 1925’s Battleship Potemkin (1925), we get the robotic descent of the Cossacks opposed to the agitated flight of the citizenry, and the street massacre of October (1927) makes even mechanical bridges seem ferocious. And less flamboyant moments, from the animalistic antics of the spies in Strike to the weeping masses at the Odessa quai, are full of expressive postures, gestures, and facial behavior. Eisenstein sculpts the human body so as to project extreme states of feeling.

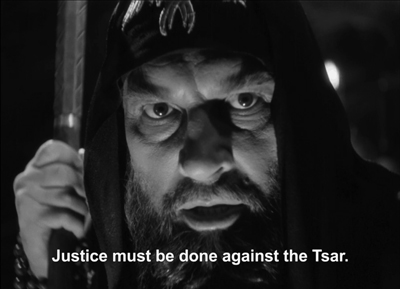

That effort is on full display in Ivan the Terrible Part II, which I discuss in our current entry on FilmStruck‘s Criterion Channel. My commentary, grounded in a single sequence, builds on an analysis I offered in my book The Cinema of Eisenstein, but the clever experts at Criterion have created dynamic juxtapositions through cuts and replays that I couldn’t summon up in print. I try to show how, as ever, Eisenstein sacrifices bland realism of behavior to something more sharp and intense. In this “theatrical” film, he goes beyond line readings to offer maniacally heightened physical action–a sort of deadly serious, amped-up, live-action cartoon. Eisenstein worshipped Disney, after all.

Today’s blog entry bounces off that installment to show the connection between expressive movement and the most banal stock-in-trade of cinema: the standard scene of two people talking to each other.

Lessons with the master

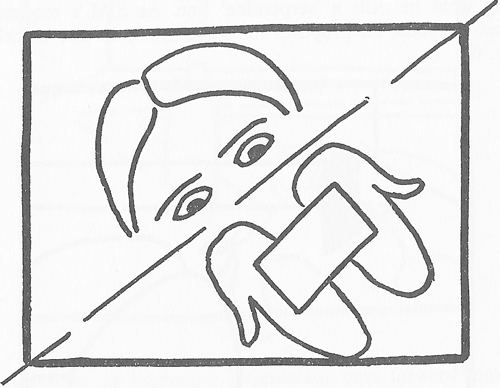

A sketch from Eisenstein’s lectures on Crime and Punishment.

Eisenstein’s silent films seek a “dramaturgy of film form” that would surpass traditions of theatrical and novelistic storytelling. This mission, which creates a sort of epic cinema, left an odd gap. From Strike (1925) to Old and New (1929), his films are notably lacking in one stock ingredient. He seldom creates sustained scenes showing a developing conflict between two characters in an ordinary setting–a parlor or office or street. With few exceptions, Eisenstein “explodes” even standard scenes by cutting to action elsewhere. The factory owners of Strike chortle over drinks while, thanks to parallel montage, the workers are rounded up by soldiers on horseback.

Other Soviet Montage directors were willing to work up theatrical scenes: Pudovkin has a Hitchcockian suspense sequence in Mother (1926), while Kuleshov turns the second stretch of By the Law (1926) into a Kammerspiel. But Eisenstein’s urge to splinter face-to-face dramaturgy came from a different sense of theatre–that “Theatricalism” of his teacher Meyerhold, who saw the stage not as the copy of a real space but as an arena for performance. Eisenstein extended this idea by thinking of the shot and the sequence as an arena for action, specifically expressive movement.

By the 1930s, Eisenstein may have sensed that sound cinema would make films more theatrical in a traditional sense. Sequences would be more concentrated in one locale and focused on a few characters. Crosscutting, a mainstay of silent film, would become rarer. He accordingly began to ponder creative ways of filming two-handers. In his courses at the Soviet film school VGIK he explored ways to intensify dramatic face-offs without interruptive cutting.

These lectures are inspiring because they show you a filmmaker thinking through problems and tracing how one solution leads to new problems. A soldier returns from the war to find his wife pregnant with another man’s child. With his students Eisenstein spent weeks scrutinizing options for performance, shooting, and cutting this simple situation. A banquet is held for Dessalines, Haitian hero. How do you film his realization that his hosts are planning to kill him? How do you present the bedroom of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, or the claustrophobic apartment of Thérèse Raquin? How do you stage Raskolnikov’s murder of the pawnbroker in Crime and Punishment…and do it in one fixed shot? (You don’t hear much about Eisenstein the long-take man.)

The results of this line of thinking show up in his films. Alas, we have only glimpses in what remains of Bezhin Meadow (finished 1937; banned, now lost). And Alexander Nevsky (1938), still conceived on a broad canvas, doesn’t really face up to the demands of intimate scenes. It’s only in both parts of Ivan the Terrible (1944, 1946) that we can see how Eisenstein plunged into doing what most directors do: filming uninterrupted scenes of people talking to one another.

Needless to say, he doesn’t do it the way they do.

The tsar in your lap

Expressive movement is involved, but so too are other stylistic strategies. For one thing, Eisenstein rethinks analytical editing. Characters need not face one another; they can be turned to the viewer and interact by shifting their eyes. No need for over-the-shoulder reverse angles either; you can cut in or out along the camera axis. Both strategies are introduced at the start of Ivan the Terrible Part I.

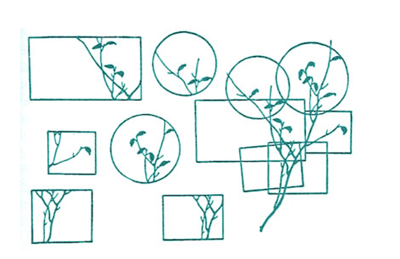

More elaborately, Eisenstein may dissect a scene through what he called in his VGIK classes the “montage unit” (uzel), a cluster of shots taken from roughly the same orientation. These yield chunks of space that overlap when edited together. He diagrammed this procedure in an illustration of cherry blossoms he found in a Japanese drawing manual.

This collage of overlapping bits, anticipating Hockney’s photo paste-ups, is actualized on film in the Pskov sequence of Ivan Part I, as I discuss in my book.

Another strategy is the use of depth. While Renoir, Welles, William Cameron Menzies, and other directors were trying out deep-space staging and depth of camera focus, so was Eisenstein. Well before Welles, he and his Soviet colleagues offered grotesque wide-angle shots. Below, Old and New and China Express (Ilya Trauberg, 1929).

More rigorously, Eisenstein began to think of how to arrange his scenes along the camera axis. True, a great many of his scenes are staged laterally, with figures arrayed from left to right.

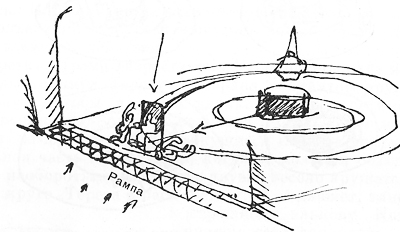

But others, particularly those at a dramatic pitch, are staged in depth. And what distinguishes Eisenstein, to my mind, is a strikingly confrontational or immersive approach. You can see it emerging in the VGIK exercises, notably in his stage designs for a hypothetical production of Thérèse Raquin. Here the paralyzed, speechless Madame Raquin terrorizes the murderous lovers with her glittering eyes. Eisenstein wanted the actors to perform on a turntable that would show her chair rotating to spy on the couple’s affair from different vantage points. At the climax, when the guilty lovers commit suicide, Madame Raquin’s chair was to break from the circle and propel itself forward, so that she would be staring furiously into the audience.

The footlights, marked with arrows, indicate that the effect is exaggerated by horror-style lighting from below.

This effect might look gimmicky, a sort of stage equivalent for what we can easily accomplish in cinema. Don’t directors often heighten the drama by making their actors advance to the camera? But in many scenes Eisenstein moves his players toward us, then cuts further backward, letting axial cuts create an unfolding foreground. A new playing space is opened up, and the actor is free, or rather compelled, to thrust further forward, sometimes into uncomfortably big close-up.

The Soviets called axial cuts “concentration cuts,” and we mostly find them used to enlarge, usually shockingly, something far off. But Eisenstein creates something more risky.“In my work,” he wrote, “set designs are inevitably accompanied by the unlimited surface of the floor in front of it, allowing the bringing forward of unlimited separate foreground details.” In principle the camera can back up again and again, and the foreground could unfold forever.

The result sometimes yields direct address, as in my Criterion Channel example, but more generally it creates a sense of characters passionately engaged in clamping their will upon others and hurling themselves not just at one another but at us. Characters confide in the camera, and–long before all today’s talk of “immersive” cinema–the camera is us.

The short lesson is that we still have a lot to learn from Eisenstein–and his films. Apart from opening up new vistas of cinema, they offer thrilling experiences. Ivan Part II, subtitled “The Boyars’ Plot,” is a dark Jacobean drama of bloody revenge and betrayal. It’s twisted enough to satisfy any connoisseur of palace intrigue. It’s also brilliantly weird as cinema. Once more the Old Man comes through.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues at Criterion for making this installment, which was a bit tougher than usual. Thanks as well to old friend Erik Gunneson, and to Masha Belodubrovskaya for translation help. Our entire Criterion Channel series is here.

The best source for Eisenstein’s VGIK classes remains Vladimir Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein, my pick for one of the top ten film books ever published. Direction, Volume 4 of Eisenstein’s Selected Works in Six Volumes (Izbrannie proizvedeniia v shesti tomakh, 1964-1969) is the source of other examples I use here, including Thérèse Raquin, from p. 622.

Of the immense literature on Eisenstein, I especially recommend Yuri Tsivian’s monograph on Ivan the Terrible in the BFI series. Yuri also provided a wonderful video essay for the Criterion DVD release, now unhappily out of print. Kristin wrote a whole book on Ivan: Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible: A Neoformalist Analysis.

I discuss Eisenstein as an action director in an earlier entry. On axial cuts in Eisenstein and others, go here; Kurosawa’s use of them is discussed here.

Hockney’s photomontage Mother 1 is from 1985.

Also, too: I noted earlier that my book On the History of Film Style has gone out of print. An e-book edition, with updates and color images, is nearing completion. I hope to offer a pdf to you soon. Yes, Eisenstein is involved.

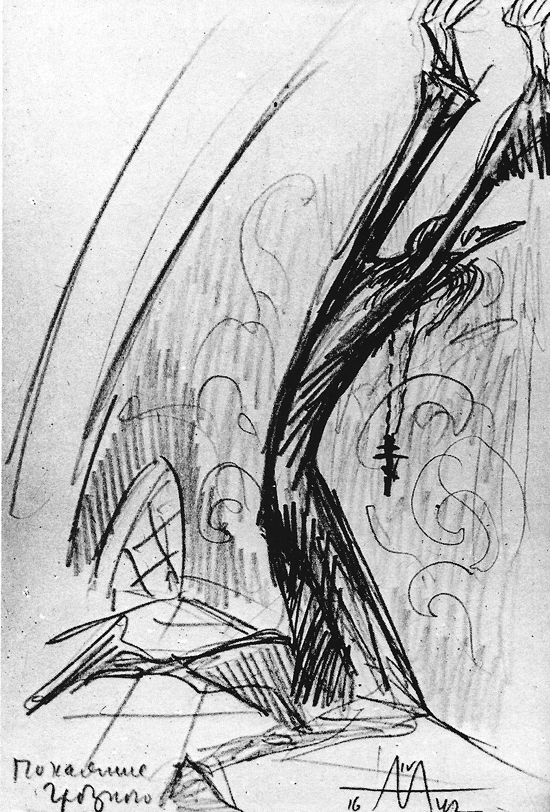

Eisenstein sketch: Ivan pleading for mercy in the Last Judgment, planned for Part III of the film.