Archive for the 'Film technique: Staging' Category

FilmStruck strikes again, and again, and again

DB here:

First, the latest installment of our Observations on Film Art series has dropped, as the kids (and now the grownups) say. It features Kristin on unconventional lighting (including darkness) in the great early French sound film Wooden Crosses (1932). This intense World War I drama boasts scenes of Fuller-like frenzy, mixed with somber passages. It’s by Raymond Bernard, a director who was a bit obscure for a while, but who gained great prominence with the rediscovery of his remarkable Miracle of the Wolves (1924).While that film doesn’t seem to be available on US video, several other Bernard films are streaming on the Criterion Channel of FilmStruck.

The arrival of Kristin’s entry tallies with the new and expanded FilmStruck. To the 1200 or so features already in the channel’s library, TCM has added 600 classics from MGM, Warners, RKO, and other studios. Many of these titles, including Citizen Kane and The Thin Man, have never been available on streaming before.

The price remains the same: $6.99 per month for vanilla FilmStruck, $10.99 for it and the Criterion Channel (which nearly all subscribers take). You can get the whole package on a yearly basis for $99.00. Yes, I bought a subscription.

Third, but no less big a deal, we just learned that FilmStruck has launched in the UK as well.

The choice of titles is smaller, partly because some films are held by other licensees in Europe, but there’s still a vast array. Cost is again very reasonable: £5.99 per month, £59.90 for a year and two free months. We think Observations installments will be available on the UK site.

I sometimes wonder how I’d have turned out if I’d had so wide and deep an access to films during the 60s. Would I have read books or listened to music? Maybe all that kept me balanced was limited access to movies. Then again, I spent a lot of time ferreting out finds–time that could have been spent watching them. I grew up in a film culture devoted to seeking whispered-about rarities and traveling to see them. Kristin and I once went to a screening of L’Age d’or supplied by a protective collector who brought the nearly unseeable film with him on the plane. Now, in the wild spiral from scarcity to superabundance, all it takes to see Buñuel’s masterpiece is pressing your remote or clicking your trackpad and paying your credit-card bill.

Life is a trade-off, but still….pretty nice to have choices. Speaking of which, our earlier installments on the Criterion Channel are here.

As usual, thanks to the Criterion team: Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and their colleagues. They not only make nice movies available, they make nice movies about them.

Michael Koresky has a wide-ranging introduction to Bernard’s 1930s films on the Criterion site, and Phillip Lopate has a characteristically engaged appreciation at Cineaste.

Wooden Crosses.

Ninotchka’s mistake: Inside Stalin’s film industry

DB here:

It’s a commonplace of film history that under Stalin (a name much in American news these days) the USSR forged a mass propaganda cinema. In order for Lenin’s “most important art” to transform society, cinema fell under central control. Between 1930 and 1953 a tightly coordinated bureaucracy shaped every script and shot and line of dialogue, while Stalin frowned from above. The 150 million Soviet citizens were exposed to scores of films pushing the party line.

True? Not quite.

When cows read newspapers

The Miracle Worker (1936).

In the film division of the University of Wisconsin—Madison, we’ve developed a reputation for revisionism. We like to probe received stories and traditional assumptions. In Soviet film studies, Vance Kepley’s In the Service of the State challenged the idealized portrait of Alexandr Dovzhenko, pastoral poet of Ukrainian film, by tracing his debts to official ideology. In my book on Eisenstein, I suggested that this prototypical Constructivist opens up a side of modernism that is artistically eclectic, and even conservative in its gleeful appropriation of old traditions.

Now we have a new book telling a fresh story. Maria (“Masha”) Belodubrovskaya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

Was this an ideological juggernaut? Aiming at a hundred features a year, the studios were lucky to release half that. In 1936 95 films were planned, but only 53 were produced and 34 made it to screens. From 1942 on, those millions of spectators saw only a couple of dozen annually. The nadir was 1951, with 9 releases. (Hollywood studios released over 300.) The flood of propaganda was more like a trickle. Theatres were forced to run old Tarzan movies.

When quantity became thin, apologists claimed that quality was the true goal. But Ninotchka’s hope for “fewer but better Russians” wasn’t realized in the film domain. Critics and insiders admitted that nearly all the films that struggled into release were mediocre or worse.

Not According to Plan shows that Soviet institutions were incapable, by their size, organization, and political commitments, of organizing a mass production film industry. Efforts to set up something like the U.S. studio system ran up against obstacles: there weren’t enough skilled workers, and decision-makers clung to the notion of the master director. Boris Shumyatsky, who visited Hollywood and tried to create something similar at home, got his reward at the muzzles of a firing squad. But brute force like this was rare; there were few administrators and creators to spare.

The great plan was to have a Plan—specifically, a thematic one. Production would be based on an annual cluster of powerful topics like “Communism vs. capitalism” and “Socialist upbringing of the young.” Personnel were slow to realize that themes were not stories, let alone gripping ones, and the real work of imagination remained un-plannable. Starting from themes rather than plot situations, the overseers could judge only final results, which meant enormous investments in development and production—all of which might never yield a politically correct movie.

Production, wholly divorced from distribution and exhibition, couldn’t count on the vertical integration of Hollywood. Masha shows in rich detail how policies and routines worked against large-scale output. One of the most striking of those policies was the veneration of directors. A great irony of the book is that Hollywood filmmaking, with its platoons of screenwriters both credited and uncredited, was more collectivist than production in the USSR. Soviet directors enjoyed enormous stature and power. They were often the moving force behind a production, bringing on writers and then recasting the script during shooting. Assemblies of directors formed review committees, discussing and often defending their peers’ work. As Masha puts it:

The filmmaking community, and specifically film directors, never gave up on the standard of artistic mastery. They listened to the signals sent by the Soviet leadership, but then incorporated these into their own professional value system, which developed in the 1920s outside the purview of the state. Using the state’s discourse of quality and their peer institutions, they enforced their own shared norms of artistic merit.

The downside of this system, plan or no plan, was that when the film didn’t pass muster, the director was to blame. Yet the twenty or so “master” directors could survive failed projects. New talent wasn’t trusted; there were too few directors; and most basically, the organization of production remained artisanal. The role of the producer (let alone the powerful producer) scarcely existed. To a surprising extent, Soviet cinema encouraged the director as auteur. How’s that for revisionism?

Screenwriters weren’t as powerful, but they did their part. Masha has a fascinating chapter on the changing conceptions of the Soviet screenplay. The “iron scenario,” modeled on a Hollywood shooting script, was intended to lay out the film in toto, so directors couldn’t overshoot or make changes. This initiative, predictably, failed. There followed other variants: the butter scenario, the margerine scenario, and the rubber scenario (no kidding), then the emotional scenario and the literary scenario.

Masha traces the work process of screenwriting and the mostly futile efforts of literary figures to leave their stamp on a production. A similar stress on process characterizes her occasionally hilarious case studies of censorship. Some of these expose the limits of industry self-censorship. One agency signs off on a film, the next one castigates it, the next one reverses that judgment, Pravda weighs in, and finally Stalin speaks up—with a completely unpredictable verdict, à la Trump. The tale of Medvedkin’s The Miracle Worker, which jumped through all the hoops and wound up being banned after initial screenings anyhow, might have been written by Zoshchenko or Ilf and Petrov. Among the elements judged “absolutely impermissible” were shots of cows reading newspapers.

The artistic and popular success of Soviet films during the New Economic Policy (1921-1928) had spurred hopes for a mass-market sound cinema that was also of high quality. What crushed that dream? Masha gives us the hows (the machinations of the studios and government bodies) and the whys (the underlying causes and rationales). Not According to Plan is a trailblazing study of what she calls “the institutional study of ideology.” It’s also a quietly witty account of the failures of managed culture. How could artists be engineers of human souls if they couldn’t engineer a movie?

But go back to the quality issue. What were those Stalinist films like artistically?

Socialist Formalism

Three projects I’ve undertaken led me to Stalin-era cinema. Nearly all English-language film histories ignored it, or reduced it to boy-loves-tractor musicals. So Kristin and I wanted our textbook Film History: An Introduction to consider it. (Revisionism again.) My Cinema of Eisenstein and On the History of Film Style built on what I saw at archives in Brussels, Munich, and Washington DC.

As a result I sought to mount an argument that Stalinist cinema was worth our attention, especially from the standpoint of film technique. The run-of-the-mill productions seemed fairly shambolic, but the top-tier dramas revealed an academic style that interested me. Some films recalled, even anticipated, innovations taking hold in Europe and America, but other creative choices were surprisingly offbeat, and not what we associate with standard propaganda.

For one thing, it was clear that montage experiments didn’t end with the 1920s, the arrival of sound, or even the “official” establishment of Socialist Realism around 1934. Granted, classic continuity editing rules the fiction films of the 1930s and 1940s, and the most flagrant extremes of the montage style were purged.

But some moments recall the silent era. These passages are typically motivated, as in Hollywood and other national traditions, by rapid action. Military combat calls forth stretches of 2-4 frame shots of bombardment in The Young Guard, Part 2 (1948). The combat scenes of The Battle of Stalingrad (1949) include very brief shots. In one passage, an artillery blast consists of three frames—one positive, a second negative, and a third positive again, creating a visual burst.

The abrupt disjunctions of the 1920s style can be felt a little in one cut of The Fall of Berlin (1950), when at the end of a long reverse tracking shot, Alyosha and his comrades rush the camera. Cut to Hitler recoiling, as if he sees them.

As you’d expect in an academic tradition, the use of fast cutting for fast action isn’t disruptive. A little more unusual is the embrace of wide-angle lenses, often more distorting than in Western cinema. Wide-angle imagery was used by 1920s filmmakers, often to caricature class enemies or to heroicize workers. The same sort of thing can be seen in Kutuzov (1945), when a soldier is presented in a looming close-up, or in Front (1943), when a gigantic hand reaches out for a telephone.

This use of wide angles to give figures massive bulk continued through the 1950s, as in The Cranes Are Flying (1957).

The 1940s aggressive wide-angle shots run parallel to Hollywood work, when in the wake of Citizen Kane (1941), The Little Foxes (1941), and other films, many directors and cinematographers created vivid compositions in depth. Those weren’t unprecedented in America, as I try to show in the style book, but there were some early adopters in Russia as well.

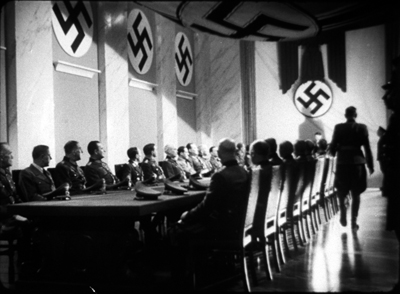

Obliged to show meetings of saboteurs, workers, generals, and party leaders, Soviet filmmakers had to dramatize people in rooms, talking at very great length. The result was a tendency toward depth staging and fairly long takes. The low-angle depth shot stretching through vast spaces became a hallmark of this academic style in the 1930s and after.

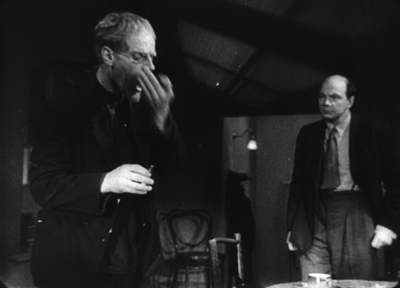

Director Fridrikh Ermler, one of the few directors who was a Party member, claimed that he devised a “conversational cinema” to deal with the prolix dialogue scenes in The Great Citizen (1937, 1939). The movie teems with shots that wouldn’t look out of place in American cinema of the 1940s.

As a solution to the problem of talky scenes, staging of this sort makes sense as a way to achieve some visual variety, and to show off production values. By the 1940s, such flamboyant depth became even more exaggerated. We see it in the telephone framing from Front above, as well as in The Young Guard Part 1 (1948, below left) and the noirish stretches of The Vow (1946, below right).

The Fall of Berlin can use depth to contrast the placid self-assurance of Stalin with a ranting Hitler, bowled over by his globe. Is this a reference to the globe ballet in The Great Dictator?

It’s well-known that for Kane Orson Welles and Gregg Toland wanted to maintain focus in all planes, sometimes resorting to special-effects shots to do so. The Soviets valued fixed focus as well, as several shots above suggest. It could be maintained if the foreground plane wasn’t too close, and the depth of field would control focus in the distance. Hence many shots use distant depth. At one point in The Great Citizen, when a woman interrupts a meeting, the official in the foreground trots all the way to the rear to meet her.

The sense of cavernous distance is amplified by the wide-angle lens.

But sometimes pinpoint focus in all planes wasn’t the goal. Another way to activate depth was to rack focus. In this scene of Rainbow (1944), the man who has betrayed the village comes home and discovers a delegation waiting to try him. At first they’re out of focus, but when he turns they become visible.

Focused or not, some of these shots push important action to the edge of visibility in a way that would be rare in American cinema. In A Great Life, a snooper is centered but sliced off by a window frame and kept out of focus, while a trial scene is interrupted by a figure far in the distance who bursts in to announce a mine collapse.

The Great Citizen shows Shakhov discussing a suspect, who hovers barely discernible in the background over his left shoulder. I enlarge the fellow and brighten the image.

This makes Wyler’s sleeve-shot in The Little Foxes seem a little obvious.

The Great Whatsis and the masters of the 1920s

The New Moscow (1938).

If American movies favor titles called The Big …., the Soviets liked The Great …. (Velikiy). But The Big Sleep doesn’t look all that big, and The Big Sick is big only to a few people, and The Big Knife doesn’t even have a knife. In the USSR, calling something big summoned up monumentality. Stalinist culture was grandiose in its architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, and even music, with symphonies of Mahlerian length and oratorios boasting hundreds of voices.

Accordingly, one effect of the depth aesthetic was to grant the characters and their settings a looming grandeur. Earth-changing historical events were being played out on a vast stage that framing and set design put before us.

Naturally, battles are on a colossal scale. Napoleon broods in the foreground (Kutuzov) and troops march endlessly to the horizon (The Vow).

1940s films feature wartime landscapes on a scale almost unknown to Hollywood. If God favors the biggest battalions, God would seem to love the Russians (a prospect that otherwise seems invalidated by history). Below: The Battle of Stalingrad.

These landscapes are surveyed in long tracking shots, a habit that survived in Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1966-1967).

Soviet forces command impressive headquarters (The Great Change, 1945), perhaps necessary to balance the Nazis’ resources (The Vow).

Parlors and committee rooms are remarkably big, and even prison cells (The Young Guard Part 2) and farmhouses (The Vow) have plenty of room.

Gigantism wasn’t unknown in 1920s cinema, or in Russian painting both classic and recent. The Vow seems to justify its scale by reference to a Repin painting, which the characters see on display.

Not only were the 1920s silent classics monumental; they became monuments. Masha records the veneration that the “master” directors felt for the works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Kuleshov, Barnet, and other predecessors. Moments in the Stalinist cinema seem to refer back to that era. The Battle of Stalingrad evokes the mother with the slain child on the Odessa Steps, and The Vow has the nerve to superimpose on Stalin (friend of farmers) an image of concentric plowing from Old and New.

These can be taken as cynical ripoffs, but in a way they testify to the fact that great silent films had forged some enduring iconography.

VIP: Very important, Pudovkin

You don’t hear much about Pudovkin’s 1930s and 1940s films, but they can be exuberantly strange. Eisenstein aside, he stands in my viewing as the director who played around most ambitiously with the academic style. Perhaps he was encouraged in this by his young codirector Mikhail Doller, but Pudovkin had already tried out some audacious strokes in A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933).

For a high Stalinist example take Minin and Pozharsky (1939). This tale of seventeenth-century warfare seems virtually a reply to Alexander Nevsky (1938), as Mother (1926) responded to Strike (1925). Minin opens with statuesque staging reminiscent of Eisenstein’s film, but the scene is handled in telephoto shots and to-camera address. The combat scenes employ handheld battle shots, along with close-ups of fighters and horsemen that aren’t stylized in the Nevsky manner.

But there’s more than pastiche here. One battle shows the Russian forces rushing from the left in tight tracking shots, while the enemy forces move from the right in panning telephoto. Especially striking are axial cuts, beloved of Soviet filmmakers for static arrays, employed in movement. Horses sweep past a tent in extreme long-shot; they smash into the tent in long shot; and in a closer view the tent lies trampled as other horses continue to flash through the foreground.

The shots are 50 frames, 38 frames, and 13 frames respectively. For a moment, we might be back in the great era of Soviet editing.

Victory from 1938 is a drama in which aviators set out to rescue an interrupted around-the-world flight. Here Pudovkin and Doller invoke the depth staging of the era only to disrupt it with what we might call “smear” cuts.

During the parade for the departing airmen, for instance, a young man happily tossing papers, in another grotesque wide-angle shot. He’s blocked by a man passing through the frame. Match on action cut to another figure, close to the camera and moving in the same direction. This figure wipes away to reveal a man reading a newspaper.

This sort of weird graphic match becomes a stylistic motif in the film. Later, when the rescue has been completed, another crowd scene yields a similar pattern of depth smeared and exposed. A shot of the parade is sheared off by a woman’s passing face. That cuts to a man’s passing face, which moves away to show the crowd behind him.

The patterning pays off when the victorious plane rolls triumphantly through the frame, blotting out the image, to be graphically matched by a passing figure who unveils the pilot’s mother embracing him.

In Admiral Nakhimov (1947) Pudovkin and Doller employ the smear-cutting technique during a battle scene. Stills are totally unable to capture the way this looks. Soldiers charge up a hill, and their falling bodies, briefly blocking the camera’s view, are given in jump-cut repetitions that suggest, through a spasmodic rhythm, the sheer difficulty of advancing.

Even stranger is the moment when soldiers rush toward a distant fortification, with a latticework basket in the foreground. Cut to the hill edge, with a comparable blob moving leftward through the frame. It turns out to be a fighter’s shoulder.

The oddest part is that this second shot is only six frames long, and every frame after the first is a jump cut; that is, some frames have been dropped as the blob makes its way across the image. The effect on your eye is percussive, and seems to be anticipated by Pudovkin’s experiments in popping black frames into shots in A Simple Case. What kind of director thinks like this?

Of course these Pudovkin/Doller films also subscribe to the official look, with monumental depth staging. The films acknowledge the 1920s tradition as well. Admiral Nakhimov casts a personal look back to Pudovkin’s great rival. A shot of the crew’s tautly bulging hammocks recalls, maybe cites, the crew’s sleeping area of Potemkin.

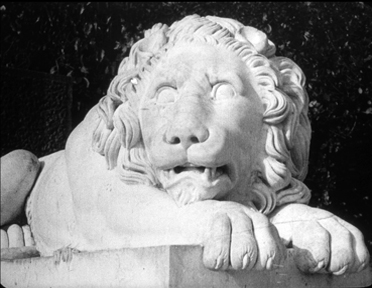

In Odessa, Admiral Nakhimov echoes Potemkin even more strongly. We get waving crowds, the stone lions, and a reminder of those famous steps.

In sum, the Stalinist cinema holds a unique interest for students of the history of film style. Not only did it apparently constitute a significant development in technique, but in forming a tradition, it provided a counterpart and sometimes a counterpoint to developments in the West. Later that tradition became something for directors to react against (Tarkovsky and Sokurov come to mind) or to adapt to new purposes (I’d put Jancsó in that category). For all the behind-the-scenes bungling, it became much more than a propaganda vehicle.

Scholars who study Stalinist film are usually impelled by an interest in propaganda or an interest in the audience’s response. My questions were different. I was driven by my interest in Eisenstein and comparative stylistics. So I tried to investigate the formal and stylistic norms of Soviet cinema. Some of those norms Eisenstein helped create, and then revised for his own ends.

Still, I feel like a butterfly collector picking out vivid specimens for an expert to explain. I can’t supply the hows and whys. How did filmmakers manage to create these remarkable images? What technical resources, of lenses and lighting rigs and film stock and set design, permitted them to craft these striking shots? Were their peers and masters insensitive to this official look? Was it taken for granted? Or was it self-consciously promoted and taught? Some of these schemas are developed in Eisenstein’s lectures at the Soviet film school. And how, at a more micro-level, do these patterns function in the individual films?

As for the whys: Why did filmmakers embrace these options rather than others? And why did they develop, sometimes apparently in a spirit of play, some oddball technical innovations?

Such questions seem to me compelled by films that turn out to be more artistically interesting than most commentators have noted. One of the most corrupt and brutal political systems in world history produced films of considerable interest, and a few of enduring value. I hope experts try to figure this all out. I bet Masha Belodubrovskaya will lead the way. Her new book is a splendid start.

Masha is no stranger to this blog, having translated Viktor Shklovsky’s remarkable “Monument to a Scientific Error” for us.

This is a good place to thank all the people who helped me see Stalinist films in archives over the decades. That number includes Gabrielle Claes, Nicola Mazzanti, and the late Jacques Ledoux of the Belgian Cinematek; Enno Patalas, Klaus Volkmer, and Stefan Droessler of the Munich Film Museum; and Pat Loughney, then of the Library of Congress.

I learned of Ermler’s “conversational cinema” (razgovornyi kinematograf) from Julie A. Cassiday’s “Kirov and Death in The Great Citizen: The Fatal Consequences of Linguistic Mediation,” Slavic Review 64, 4 (Winter 2005), 801-804. The depth aesthetic of high Stalinist cinema proved valuable when 1960s bureaucrats decided to make Stalin disappear. See our online supplement to Film History: An Introduction.

There are more examples of “Stalinist formalism” in On the History of Film Style–recently declared out of print, but soon to appear in a new electronic edition on this site. See also my Cinema of Eisenstein for arguments about how he created and then swerved from some of his peers’ norms.

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Eisenstein on his birthday. But they make him a slim, hip metrosexual. Revisionism can go too far.

Kelley Conway, Masha, and Scott Gehlbach, at a party last night celebrating Masha’s book–and her winning tenure! Kelley’s contributions to our blog are here and here and here.

Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight

Idle Wives (1916), produced by Lois Weber and Phillips Smalley.

DB here:

This year I’ve been bouncing between two magnificently creative decades in US film, the 1910s and the 1940s. In autumn I’ve been caught up in things involving Reinventing Hollywood, but those were followed by some big doings on campus.

In spring I was lucky enough to be in residence at the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. That enabled me to watch nearly a hundred feature films from 1914-1918. I did a talk at the Library reporting on some of that work, and I’ve offered some preliminary observations on those in earlier entries.

Last week, Jim Healy of our UW Cinematheque brought some of the films that had impressed me during my DC stay. There was a Saturday marathon of The Iced Bullet (1917), Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915), The Bargain (1914), Will Power (1913), and The Man from Home (1914). For our Film Studies Colloquium across two Thursdays we screened False Colours (1914; incomplete), The Case of Becky (1915), Idle Wives (1916; incomplete), and Ben Blair (1916). Some of these I’ve written about in earlier entries, here flagged by links.

The Saturday screenings were accompanied by the lively, indefatigable playing of David Drazin. David worked for many hours and without having seen the films in advance. He’s a superb artist.

Seeing the films again, of course I found more to say.

Revival and revision

The Case of Becky (1915).

One of the secondary arguments in Reinventing Hollywood is that many storytelling techniques of silent film subsided during the 1930s but were revived during the 1940s. Silent films were full of dream sequences, subjective points of view, fantasy projections, and flashbacks. Those got elaborated and consolidated for the sound cinema by Forties filmmakers.

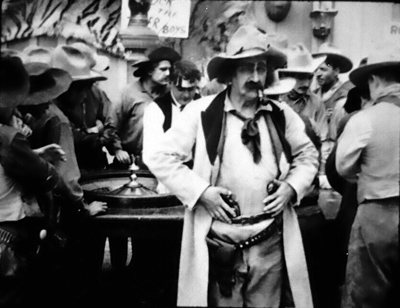

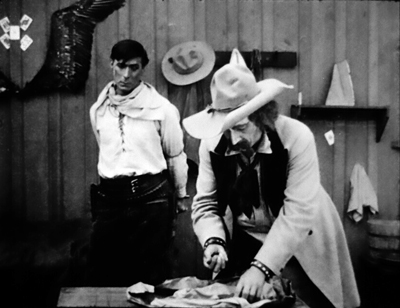

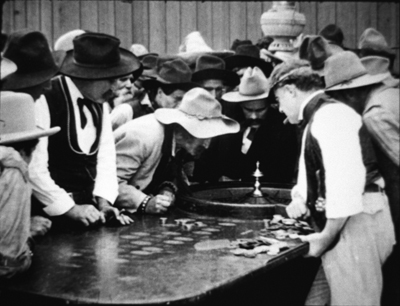

So it wasn’t surprising to find that The Bargain, a fine William S. Hart western, squeezed a lot of mental imagery into a single scene. The Sheriff has arrested Jim Stokes and retrieved the money he stole. Lashed to the bedpost, Jim remembers his wedding and the woman he’s betrayed, presented in a slow dissolve to the past.

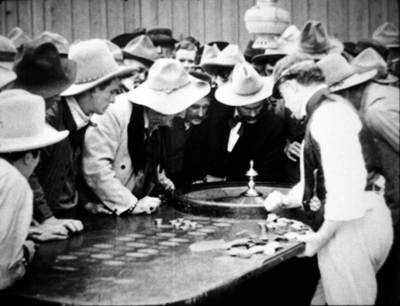

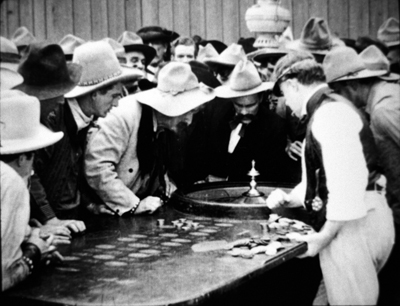

Meanwhile, downstairs in the saloon casino, the Sheriff succumbs to an impulse and loses all his money at roulette. Then he remembers, via another dissolved-in flashback, that he scooped up the stolen money too.

Back in the present, he digs that money out of his poke and bets it—and loses.

Later, in the hotel room, Stokes learns of the Sheriff’s folly and has a good laugh. But then he imagines Nell waiting for him, shown in a split-screen image.

At which point the Sheriff imagines his telegram arriving at his town, announcing Jim’s capture and the recovery of the money. That vision reminds him that he can’t return without the money he has squandered.

This makes him strike the central bargain with the thief he’s captured.

In a 1930s film, these visualized memories would most likely be presented verbally, as part of the stream of dialogue. (“When I think of marrying Nell….””I’ve promised to bring the money back…”). But 1910s American films tended to use dialogue titles sparingly; a lot of the films we saw asked the viewer to grasp the situation without benefit of words. The Bargain has only nineteen dialogue titles in 77 minutes (at 16 frames per second).

The Bargain is a good example of how purely pictorial storytelling was used to explicate a situation. Interestingly, today’s films are rather close to this tendency: fragmentary flashbacks and mental visions are common in mainstream movies.

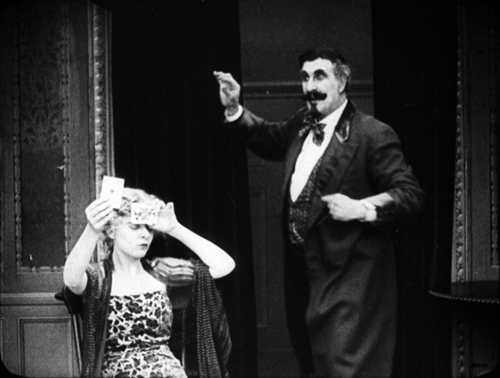

Another echo struck me, this time in The Case of Becky. This is an early story of split personality, a narrative premise popularized after The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Here the young woman Dorothy (Blanche Sweet), under the sway of the sinister hypnotist Balzamo, develops a second identity, the surly and disruptive Becky. Becky isn’t really very dangerous, but when a young doctor, himself a master of hypnosis, falls in love with Dorothy, he determines to cast out Becky. He does so in a passage of intense mind control, visualized through a double exposure of Becky departing Dorothy’s body.

What interested me is that the same visual device was used by Arch Oboler in Bewitched (1945), one of the earliest psychoanalytical films of that era. The heroine’s two sides are summoned up by the shrink.

I suspect that Oboler got wind of the Selznick/Hitchcock Spellbound (1945) and rushed a B-film into production. (He could move fast because he adapted one of his radio plays.) Bewitched was released five months before the Selznick/Hitchcock film. It’s not great movie, but it has a sort of pre-Psycho pitilessness, and it’s always nifty to see a 40s film picking up on a silent-film device.

Cutting things up and filling the corners

My main research questions about the 1910s revolved around stylistics—matters of staging, lighting, shot scale, variety of camera setup, and editing choices. For about twenty years I’ve been exploring how, to put it broadly, the long-take, intricately staged tableau cinema was largely replaced by films dependent on continuity editing. By focusing on the years 1914-1918, I thought I could track the transition in finer grain.

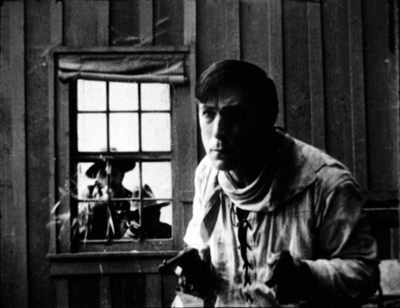

Many films were already building their scenes out of several shots. Go back to The Bargain, from 1914. A series of shots shows Stokes surrounded at the door and window, while also giving us a brief shot from a new angle incorporating tight depth, as the men at the window get the drop on him.

This freedom of camera placement within a single set is typical of the Hart films (see here and here), and of other films by Reginald Barker. It was sometimes visible in Alias Jimmy Valentine from the year before (1913), but it’s more pronounced in The Bargain. Several scenes in the hotel room where Stokes is tied up display a fairly wide array of camera setups.

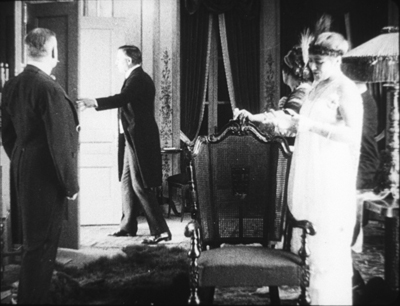

At the other extreme, The Man from Home (1914), credited to Cecil B. De Mille and Oscar Apfel, displays the tableau approach in full bloom. One long take at the climax shows a packed salon. To take just the high points of some pretty dense choreography: Ivanoff bursts in to confront his errant wife, who crumples in the lower right.

Pike holds off the Earl of Hawcastle, now partnered with Ivanoff’s wife. Hawcastle rushes to the right rear to open the curtains (stepping into a spotlight). Summoning the police, he returns to the middle ground to demand the arrest of the fugitive Ivanoff.

But a functionary arrives in the background, lifting his arm to signal the arrival of the bearded Grand Duke Vasili. Vasilii stalks in to take command of the middle ground and confront Hawcastle. Throughout. shrewd shifts of actors’ position open pockets of action, and the performers turn from the camera to drive our eye into depth.

Throughout most of this tableau, broken by occasional titles, Ivanoff’s treacherous wife is crouching in the lower right. This is an example of the “all-over staging” we find in 1910s cinema. Often corners and edges of the frame will be activated and demand to be noticed. For example, in The Bargain Stokes is observing a scene through a window. Cut inside the room, and Stokes can be seen way off to the right in a single pane.

Later directors would have placed the window nearer frame center so that Stokes’ face would be more quickly noticed.

Sometimes we find the filmmaker trusting the audience—or at least a modern audience—too much. In Ben Blair (1916), Ben is lured into a brothel and pulls his pistol in order to escape. But in the master shot, off to the right, the astute viewer can see the louche Sidwell, who’s aiming to marry Flo, cozying up to a hooker before he rises to flee the room. He has already met Ben and fears being recognized.

Director William Desmond Taylor doesn’t supply what I expect Barker would provide: a separate shot of Sidwell seeing Ben and rushing out of the room. Nor does Taylor provide a gradually unfolding tableau that would, by means of figure movement, frontality, centering, and other cues build to a crescendo revealing Sidwell’s presence—the sort of thing we see in The Man from Home. As it is, many viewers may miss the main point of the scene, which is to divulge Sidwell’s sexual betrayal of Flo.

But maybe this was best. Cutting straight in to Sidwell might have suggested that Ben recognizes him immediately. But he doesn’t. As Ben turns, Sidwell is ducking away. Ben has revealed, and seems to be concentrating, on a new center of interest, the woman who’s impudently blowing out cigarette smoke at him. He, like us, is distracted from Sidwell’s departure.

Still, we’re supposed to spot Sidwell even if Ben doesn’t. Only much later, after Sidwell has nearly convinced Ben to give up on courting Flo, does Ben realize that it was Sidwell he saw in the brothel. That’s done through a split-screen flashback of Sidwell starting guiltily beside his floozy.

Again, the shot is a little clumsy in showing Sidwell looking toward the camera, as if Ben saw him directly; but it seems to be another mental image, representing Ben’s now-clear impression that Sidwell was in the brothel.

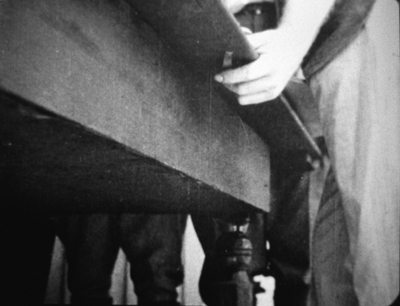

We don’t have to puzzle over such matters in The Bargain. Barker had mastered the precision necessary for off-center details. When the Sheriff is risking his money at the roulette wheel, a close-up reveals that the croupier is controlling it.

But here’s the neat part. At the turning point, when the Sheriff loses everything, Barker gives us close-ups of the Sheriff and the croupier, but not the hand pressing the button.

We’re sufficiently trained to spot the croupier pressing the button in the long shot (again, off-center). There’s no need to show the gesture again because the priming close-up has told us the game is fixed. Interestingly, that insert shot doesn’t come at the very start of the Sheriff’s gambling jag, so initially we might think the wheel is honest. We get the revelation just when the Sheriff is about to bet the money he can’t afford to lose. That boosts the dramatic tension.

Movies within movies

The Iced Bullet (1917).

While stylistics was my prime research focus, I couldn’t help but notice some bold narrative initiatives. A good example of a playful one was The Iced Bullet (1917), which has a Russian-doll structure (like many 40s films).

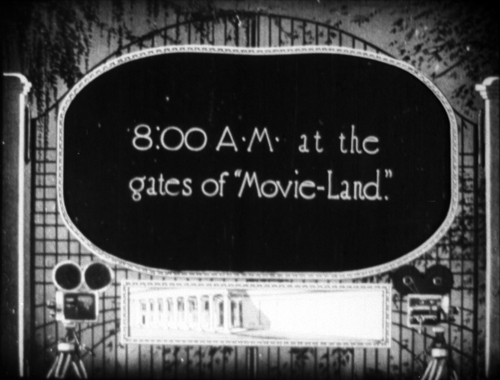

The inner tale recounts how a scientific detective solves an attempted murder, one using the method tipped in the title. But that’s swallowed up in a prologue and epilogue showing a foppish author crashing the Ince studio. He manages to interfere with filming, evade the guards, and take refuge in an executive’s office. He has brought along his screenplay, The Iced Bullet, which he hopes to direct and star in.

At the desk he falls asleep and dreams the detective story we see. At the film’s end he wakes up and flees the studio, pursued by watchmen. One trade paper of the time suggests that the comic frame story was devised in order to expand and elevate the murder story–which may explain why the film has been credited to both Reginald Barker and Charles Swickard. Maybe one directed the frame story and one the embedded one.

As the frame story stands, it offers us not only a comic pretext but precious views of the vast Ince studio.

There are also some nerdish in-jokes. C. Gardner Sullivan, author of the whole film we see, appears as the executive whose office is commandeered, while Barker shows up as a raging director trying to get the aspiring screenwriter off the set.

And when that invader takes over Sullivan’s office, he scoffs at a huge bust of William S. Hart, by now a major star.

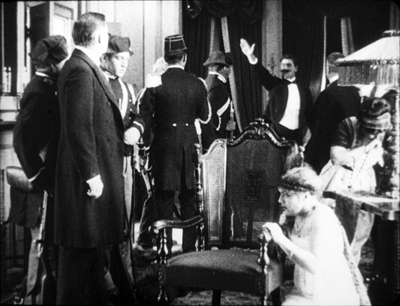

The year before, Lois Weber and her husband Phillips Smalley had given us a more intricate film-within-a-film structure. The central story of Idle Wives centers on the plights of three women. Anne Wall is a wealthy but disillusioned wife who leaves her husband John to take up settlement work. She lives with Alberta, who has married John’s brother Richard. The couple has been disowned by John’s mother and sister. In her charity duties Anne meets Molly Shane, who has left her family to run off with the no-good Larry. Anne helps Molly through her pregnancy and reconciles her with her family. John, seeing how Anne has changed the lives of unfortunate women, welcomes her back and faces down the disapproval of his mother and sister.

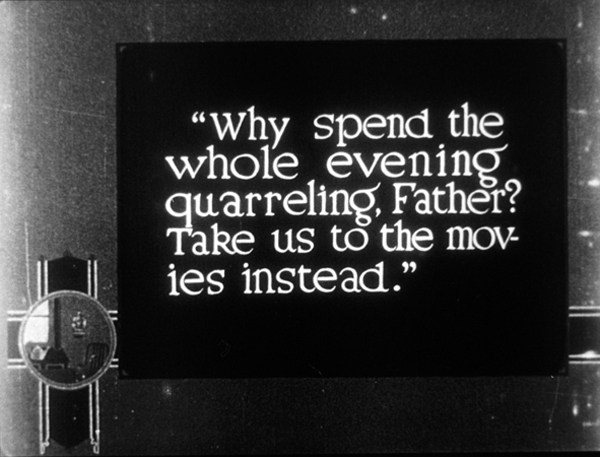

This story is enclosed within another one, involving three other women. The Jamiesons, though wealthy, have an empty marriage. When Jamison meets an old girlfriend, they decide to go see a movie. They’re trailed by Mrs. Jamieson. At the same time, Mary Wells disobeys her mother and goes out with the thug Tough Burns. They wind up going to the same movie theatre. And the poor, hard-working Smith family, whose daughter is longing to escape, decides to take a day off and go to the theatre as well. All of them join the audience for Life’s Mirror, a film by none other than….Lois Weber. It stars Weber and Philips Smalley, who’s given his own poster.

This frame story, not in the source novel, is pretty stunning. In the first reel the people assemble at the theatre, which, as you see up top, flaunts the Weber-Smalley brand. These scenes are fascinating representations of moviegoing culture of the time, showing the ticket booth and the auditorium.

Just as important is the way that seeing the movie affects the characters in the frame story. Shots show people in the audience reacting to the fictional world.

The point of the film is that the characters, recognizing their counterparts on the screen, improve their behavior. Cinema is granted the power to divine the problems of its audience, and to heal their lives.

Or so we’re told from contemporaneous synopses. Because, in one of the great losses of American silent cinema, we have only the first and second reels of Idle Wives. Fortunately, those constitute the prologue and the initial exposition of the inner story.

How does the frame story turn out? According to the fullest contemporary account I’ve seen, in the epilogue Jamieson sees his wife weeping in the aisle, sends her rival away, and reconciles with her. Mary is shocked into realizing the risk of dating Tough Burns, who seems ready to reform after seeing his fictional double behave so cruelly. The Smiths agree to be kinder to one another, and the daughter of the family realizes the danger of fleeing home.

Two network narratives, then, in a single movie. Idle Wives has over twenty individuated characters, linked by kinship or domestic circumstances. (For instance, in both stories some characters live in the same building.) It becomes didactic, as Weber’s films often are, with the theatre presenting a placard that underscores the lessons, and opening titles that address the audience directly. Idle Wives was fairly described by a review as “a preachment on the sacredness of the home, also on the power of the motion picture.”

For most film historians, the great experimental film of 1916 was Intolerance, another tale of parallel situations and fates. But the same month that Griffith’s ungainly masterpiece was released saw the appearance of Idle Wives—in its way, no less daring, and by today’s standards startlingly modern. How many other remarkable films have been lost or have gone unnoticed? Like archaeologists excavating a site, we have a lot more digging to do to understand the glories and unpredictable experimentation of the cinema of the 1910s.

Thanks to my hosts at the Kluge Center last spring: Ted Widmer, Emily Coccia, Travis Hensley, Callie Mosley, Mary Lou Reker, and Dan Turello, as well as the team in the Moving Image Research Center–Karen Fishman, Dorinda Hartmann, Josie Walters-Johnston, Zoran Sinobad, Rosemary Hanes, and Alan Gevinson–along with the Culpeper dynamic duo Mike Mashon and Greg Lukow. We in Madison are especially grateful to Lynanne Schweighofer and George Willemen for preparing a reconstructed version of Ben Blair. Thanks also to Jim Healy, Mike King, and Roch Gersbach for arranging the Madison screenings.

Some of David Drazin’s piano accompaniments are available on DVDs from Texas Guinan (that’s right, tguinan at aol.com).

Idle Wives has been posted online by the New Zealand Film Archive and the Library of Congress. An informative puff piece from the era is “The Smalleys Turn Out Masterpieces With Actors or With Types,” The Moving Picture Weekly 3, 14 (18 November 1916), 18-19, 26. The most comprehensive guide to Lois Weber’s career is Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015). I discuss the Smalleys’ little masterpiece Suspense (1913) here. Reinventing Hollywood has a chapter on the psychoanalytic cycle of the 40s, including Bewitched.

On all-over staging, and bungling the tableau, see the entry “Looking different today?” We have some entries on decentered framing, one on Mad Max: Fury Road and another on Fritz Lang’s use of corner frame space.

Idle Wives (1916).

Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch

DB here:

All artists rely on predecessors in one way or another. True, at any moment the artist may confront a dizzying array of options; there are a lot of models out there. And sometimes artists work against received traditions rather than building on them. (Usually, though, those assaults on tradition borrow from other traditions, often minor ones.)

Anyhow, it’s a good first move to assume that any artwork we encounter owes something to forebears. If we want to understand continuity and change in film history, then, we can try to know something about genes, styles, received habits, work routines, and other ongoing pressures on moviemakers.

Schema and revision

Favorites of the Moon (Iosseliani, 1984).

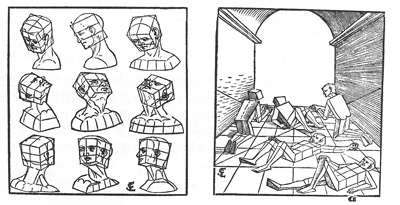

Among the strategies for making sense of a given film or filmmakers, one I’ve found useful I’ve swiped from E. H. Gombrich. In Art and Illusion, he wrote of schema and revision as one way of thinking about an artist’s ties to tradition. A schema is a pattern that has proven reliable for art-making in the past. His examples are the geometrical templates that became part of the training of Western European artists.

Gombrich suggests that artists adapt the schemas to the purposes at hand–new tasks, or the urge to capture aspects of reality that their predecessors missed.

Once a hack has learned how to make the image of a tolerably convincing head, he may be tempted to use this standard formula for the rest of his days, merely adding just such distinguishing features as will mark the admiral or the court beauty. But obviously once he is in possession of a standard head, he can also use it as a starting point for corrections, to measure all individual deviations against it. He may first draw it on his canvas or in his mind, not in order to complete it, but to match it against the sitter’s head and enter the differences onto his schema.

Hence the Gombrichian slogan: Making precedes matching. You render a version of visual reality in and through the forms bequeathed to you by tradition, adjusting them as you may need.

In film, I suggested in On the History of Film Style, we have several stylistic schemas. A prototype would be shot/ reverse-shot staging and cutting. You can replicate the schema, just running it again, as most filmmakers do. (All those damn shoulders.) You can revise it, as Ozu, Bresson, and other filmmakers did. You can adapt it to the long take, as Hitchcock and Iñarritu did. Or you can reject it, as Tati and Iosseliani did with their extreme long-shots. Iosseliani: “As soon as I see a film that begins with a series of shots and reverse shots, with lots of dialogue and well-known actors, I leave the room immediately. That’s not the work of a film artist.”

Stylistic schemas are perhaps the easiest to spot; when they cluster, we get something like a style in a general sense, such as continuity editing, or more recently what I’ve called “intensified continuity.” Even minor genres, like long-take lipdubs, have their own schemas. And revisions are ongoing. In mother! Darren Aronofsky fills the “free-camera,” run-and-gun handheld style, which usually favors medium shots, with extreme close-ups that put menacing, barely identifiable action in out-of-focus backgrounds. The result can be seen as a revision of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it reframings on display in the Bourne films.

There are schemas for narrative too. At the broadest level, the sacred Three-Act Structure can be thought of as a macro-schema; so too the more fleshed-out Four-Part Structure Kristin has proposed. In my new book Reinventing Hollywood, I invoke the schema/revision idea to talk about more specific narrative strategies of the 1940s. Examples are the flashback plot, with a shuttling between present and past, and the network narrative, which brings friends, kinfolk, and strangers together in a limited time or space.

Watching Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) again at the Venice Film Festival reminded me that the schema/revision process can take place not just between the filmmaker and tradition but within the work of a director. Once a director develops a “signature style,” that too can be reworked, refined, stretched, or even repudiated. Griffith recast his characteristic last-minute-rescue crosscutting pattern, once by making the rescue too late (Death’s Marathon), and once by multiplying it by four (Intolerance). Ozu not only revised Hollywood continuity principles, but then tweaked and played games with his customized version. Arguably, Hitchcock did the same with his refined point-of-view structures and man-on-the-run plot patterns.

In the Lubitsch case I’m considering, we have a very tiny piece of schema revision, but one that shows him to be a fastidious creator. Having sculpted a small moment one way, he extracted its principles and remade it, for other purposes in another film.

The grapes

The street singer Rosita is in the palace waiting for the king. At first she’s awed by the scale of the room, but then she spies a bowl of candied fruit on a little table. As often happens in Lubitsch’s American silents., this plays out through eyeline cutting.

Rosita heads out of her shot and a frame-edge cut brings her to the table. She drifts past the fruit, eyeing it, and now the sequence’s rhythm is established.

When Rosita leaves the frame, the camera holds on the table and the fruit bowl.

After a beat, she strolls into the frame moving right, pointedly ignoring the fruit. She goes out of frame and Lubitsch holds on the bowl.

Then Rosita comes in from offscreen right and plucks a grape as she passes through the frame. Lubitsch holds the empty shot.

Rosita comes in again from the left, snags another grape, and walks out frame right.

After another beat, she thrusts back into the frame and starts to dig into the fruit.

She’s hungry but afraid of being caught, so she swipes the food as casually as she can. Once she thinks she’s not being watched, she can take what she wants.

Instead of cutting the action up, Lubitsch holds the shot and makes a sort of contract with the viewer. The gag depends on simple spatial continuity; we know where Rosita is when she’s out of frame, so we can anticipate her coming back in and wonder what she’ll do on the next pass. By holding on the table, the camera “knows” she’s coming back and waits for her; the bowl draws her like a magnet. We enjoy the game of expectation Lubitsch has set up.

Simple as it is, this passage shows the patterned nature of a stylistic schema. You could plug different things into that pattern—a bed rather than a table, a gun on a counter, a detective casually looking for clues—but as long as you set up the pause holding on the “empty” frame as the actor passed through to and fro, we’d have a recognizable schema. It’s one that other filmmakers could use.

Or one that Lubitsch himself could cleverly revise. If the Rosita version builds a mild sort of suspense, what if we added a dose of surprise? That’s what happens in Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

The drawer

Lord Darlington, hoping to drive a wedge between Lady Windermere and her husband, suggests that she look for a check Lord W wrote to the mysterious Mrs. Erlynne. Lady W walks into the study and pauses at her husband’s desk, then goes to sit in a chair nearby.

Like Rosita studying the fruitbowl, she eyes the desk drawer holding the check.

She rises and, thanks to another frame-edge cut, walks to the desk. But thinking the better of it, she leaves the frame, going out left.

The camera stays on the desk. Pause.

Suddenly Lady W bursts into the frame, but from the right side.

Lubitsch, who understood the rules of continuity better than almost anybody, knew perfectly well that she should have come back in from the left. The actor had to go around behind the camera in order to come in from this “impossible” angle. We’d be startled to some extent if Lady W had suddenly burst in from the left, but now the effect is amplified by the unpredictable entrance from the right. To spatial suspense, holding on the desk, Lubitsch has added spatial surprise.

Interestingly, there’s another anomaly here: the early POV shot of the drawer. It represents what Lady W sees, but from the opposite angle, from the “other side” of the desk. A shot respecting her vantage point would have looked like this.

Since this is a silent film, even if Lubitsch had made a mistake during filming, the shot could have been flipped in postproduction to look correct. It’s just possible that this “wrong” POV shot is another schema revision–one that anticipates Lady W’s “wrong” reentry into the desk shot. This possibility is strengthened soon afterward when Lady W tries to open the drawer, in a framing that shows the “correct” angle.

And soon afterward, when Lord Windermere joins his wife, he will look at the drawer from the “correct” angle as well.

A spare take of his POV shot could have replaced Lady W’s mismatched one. (Though the fastidious Lubitsch gives us a slightly different angle from Lady W’s, one corresponding to the position of Lord W). It seems likely, then, that Lubitsch simply wanted Lady W’s odd POV shot. Perhaps he saw it as a cryptic hint that something important was about to happen on the other side of the desk, where Lady W will pop in.

With Lubitsch, we’re always getting into such pictorial niceties. In any case, having tried out the “waiting camera” schema in Rosita, garnished it with predictable frame entrances and exits, Lubitsch revised the schema to create a different effect. He knew that audiences would expect Lady W to reenter the way Rosita did, and he exploited our expectations to yield a bump of surprise–one that increases the expressive effect of her pouncing on her husband’s secret.

More generally, the concept of schema/revision seems to me a useful tool for studying a filmmaker’s ties to tradition, as well as his or her developing personal style. This is not to mention the role of rivalry, another important pressure for continuity and change in film craft. Once a schema is out there, people can compete for ways to revise it. But that’s a topic for another day.

My frames from Rosita are from the standard, rather bad surviving print. It has recently been restored by the Museum of Modern Art under the auspices of Dave Kehr, and the new version looks very fine. More information here.

The illustration of heads comes from Erhard Schön’s manual of 1538, reproduced in Gombrich’s Art and Illusion (Princeton University Press, 1960), p. 159; my quotation comes from p. 172.

The quotation from Iosseliani comes from “Iosseliani on Iosseliani,” in The 24th Hong Kong International Film Festival Catalogue (Hong Kong: Urban Council, 2000), p. 138.

Kristin provides close analysis of Lubitsch’s silent film style in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood: German and American Film after World War I, available online here. I discuss this sequence from Lady Windermere in more detail in Chapter 9 of Narration in the Fiction Film. But when I wrote that, I hadn’t seen Rosita. I consider how Ozu varied his bespoke version of continuity editing in Chapters 5 and 6 of Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available online here.

Fruitbowl, Mary Pickford, Ernst Lubitsch, and Holbrook Blinn on the set of Rosita.