Archive for the 'Film technique: Cinematography' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

The camera as perpetual motion machine: Jeff Smith on BREAKING THE WAVES

Jeff Smith’s analysis of von Trier’s film has been posted on our series on the Criterion Channel of FilmStruck. Here, as is his custom, he offers more insights into this extraordinary work.

I still remember the shock I felt watching Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves for the first time. Some of it was undoubtedly a response to the film’s emotionally unsettling narrative. Yet I also wasn’t quite prepared for the caught-on-the-fly quality of Robby Müller’s handheld cinematography.

Was this the same director who had created such striking, high-contrast, black and white images for Zentropa?

Was this the same Robby Müller who composed the austere, yet stylish landscapes shots in Kings of the Road, Paris, Texas, and Down by Law?

In contrast to the very controlled look of those titles, the prologue to Breaking the Waves establishes a more muted visual style. Interior spaces look washed-out and the color is drained from the beautiful Scottish landscape. This effect was created by shooting on 35mm, scanning the negative to video, and transferring the altered footage back to film.

The camera also moves constantly. It anxiously follows action as it unfolds to capture a sense of both intimacy and immediacy. In Zentropa, the actors mostly were subsumed into the overall visual design of the image. In Breaking the Waves, the specific choices in editing and cinematography were subordinated to the actors’ performances. For Trier, this choice was partly dictated by the material. He wanted to preserve a sense of existential mystery about the film’s events. The decision to shoot in a raw, naturalistic style was necessary to keep the film believable.

Breaking the Waves also laid down a marker in terms of von Trier’s commitment to the dictates of the Dogme 95 manifesto. Although the film departs from those principles in significant ways, it previews the even nervier approach von Trier takes in The Idiots.

Yet elements of pictorial stylization are retained in Breaking the Waves, and they foreshadow the formal tensions that characterize much of von Trier’s later work. In Dancer in the Dark, the juxtaposition of stylization and naturalism is evident in the way Bjork’s musical numbers provide escape from the grim misery of Selma’s daily existence. Antichrist opens with luminous black and white imagery in super-slow -motion that directly contrasts with the slightly more desaturated color seen in the rest of the film.

Melancholia begins with fantastic, colorful, almost still tableaux accompanied by an excerpt from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. This differs markedly from the rest of the film which is shot in the semi-documentary style seen in Trier’s Dogme work.

In what follows, I trace the way Breaking the Waves’ dialectic between naturalism and stylization is expressed in particular visual motifs. I also show how these techniques reinforce some of von Trier’s larger thematic concerns. Warning: some spoilers ahead.

Camera playing catchup

Robby Müller’s handheld cinematography in Breaking the Waves fulfills a number of different objectives. First and foremost, the constant, restless movement adds a visual dynamism that contrasts with the locked-down camera frequently seen in “slow cinema.” Secondly, the association of this style with documentary adds a jolt of authenticity to the scenes of Jan aboard ship and the various emergencies that occur at the hospital. Lastly, the “caught on the fly” quality of the images lends a sense of intimacy and immediacy to the character’s interactions.

Breaking the Waves’ most common technique involves the use of rapid pans to convey a feeling of imminence–the sense of pushing us toward what is just about to happen in the scene. Those anticipatory pans pans serve a number of storytelling functions.

They’re often used during dialogue scenes as a variant of more conventional shot/reverse shot techniques. In the hospital, when Bess and Dodo discuss Jan’s sick fantasies, the camera swivels between the two speakers some eight times.

The entire conversation is handled in five longish takes instead of the dozen or so shots we’d get if von Trier had used shot/reverse shot.

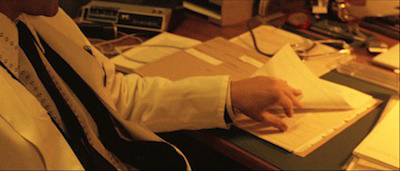

More commonly, von Trier’s dialogue scenes use quick pans to capture another character’s reaction before then cutting back to the other speaker. Near the midpoint of Breaking the Waves, we see Richardson rifling through the pages of Bess’s file. Richardson asks Bess about her care under another doctor. The camera swings swiftly over to Bess who professes ignorance of this prior episode.

The camera then pans back to Richardson.

He acknowledges that her treatment was related to her brother’s death before von Trier eventually cuts back to Bess. Given the emphasis on performance during shooting, these panning movements keep the actors in the moment, enhancing the impression of dramatic intimacy and visual energy. But the style also enables Trier to shoot coverage so that he can select between different takes during editing.

In some instances, these rapid shifts from one character to another preserve the interactions of the ensemble within a single take. This occurs, for example, as the wedding party reacts to the sudden appearance of rain. We see it again later when Jan and his buddies pass around a flask of booze.

In still other cases, these rapid pans enhance the dramatic impact of eyeline matches. The viewer is often cued to these moments by a character’s glance offscreen and their facial expression. The camera then pivots to reveal what is in the offscreen space. A fairly early instance of this is when Dodo returns to Bess’s house to find her sitting quietly and Bess’s mother asleep.

Later Trier uses Bess’s glance offscreen to cut during a whip pan to a rabbit on the side of the road.

The moment serves as counterpoint to what we’ve just seen. Bess has vomited in disgust after a sexual encounter on a bus. The way she wrinkles her nose at the bunny reminds us of her childlike naiveté.

The panning motif pays off during the inquest into Bess’s death. Dr. Richardson testifies that Bess died because of her inherent goodness. Unsurprisingly, this claim is met with skepticism from the magistrate presiding over the hearing. Von Trier then cuts to a close-up of Dodo.

The camera tilts down and pans right as she grasps someone’s hand. It then tilts back up, to reveal Jan seated next to her.

The revelation comes as a bit of surprise because Trier has omitted the narrative action that connects the hospital scenes to the hearing. As mysterious as Bess’s death is, Jan’s recovery prompts even deeper questions. How is it that Jan survived when it appeared that his own death was imminent? More pertinent, how was his paralysis cured? In exploring the nature of the miraculous as part of the everyday, von Trier presents us with an enigma that he refuses to explain. It is here that we first begin to grasp the meaning of Bess’ religious faith and the impact of her self-sacrifice.

Are you there, God? It’s me, Bess.

Another important visual motif involves the long takes used for Bess’ talks with God. For the most part, Breaking the Waves’ average shot length is relatively short. But Trier sets off these moments of prayer by shooting them in a markedly different style.

More often than not, Müller’s camera photographs Bess in close-up or medium close-up to focus our attention on her face. Emily Watson uses the simplest of means to indicate the two sides of her dialogues with God. She shifts her gaze either upward or downward and changes her style of speech. Notably, in a suggestion of the degree to which Bess has internalized the church’s doctrines, her vocal impersonation of God sounds uncannily like one of the church elders.

These shots of prayer often unfold in real time lasting a minute or more. Their duration and more static framing convey both a sense of intimacy and important information about Bess’ motivation. Her imagined conversations with the heavenly father help to explain her actions in what would otherwise seem like wildly improbable changes in character.

These scenes also invite the viewer to consider Bess’ mental stability. Because of her childlike nature, Bess’ belief that God talks directly to her initially seems delusional. Yet, as the film goes on, Bess’ devotion to both God and her husband introduces the possibility that her actions are divinely inspired. By demonstrating her selfless love for Jan above all else, including her own safety, von Trier suggests that Bess’ sacrifice might be the reason for Jan’s recovery.

Or it could all just be a coincidence. Jan’s recuperation might not have any explicable cause, either physical or spiritual.

An energetic but casual style: raw immediacy as studied nonchalance

Throughout much of Breaking the Waves’ running time, von Trier’s narration seems to be rather communicative. The relentless camera movement and frequent cutting suggest a desire to capture the story as it unfolds and to transmit the most narratively salient material.

At key moments, however, the film’s visual techniques prove surprisingly reticent. Significant plot developments are sometimes handled in an offhand fashion. This strategy seems to be an extension of von Trier’s interest in making the film’s melodramatic narrative seem plausible. (Indeed, Breaking the Waves plays as a sort of Magnificent Obsession for the art film crowd.) More than that, though, this restraint also encourages viewers to form their own conclusions about the events depicted.

Consider Jan’s observation that Bess has blood on her wedding dress after consummating their marriage in the bathroom of the reception hall.

Another director would likely cut to an insert from Bess’s pov to underscore this image. It would serve as a symbol of her loss of innocence and as a grim foreshadowing of her ultimate fate (i.e. love as a form of blood sacrifice). But Trier refuses to force that interpretation on the viewer. Instead, by showing Bess calmly rinsing out the stain, von Trier allows the moment to resonate more organically.

This motif reaches a kind of apotheosis in the shot of Jan standing on crutches at Bess’s gravesite. The whole story has built toward this moment. Yet Trier treats it in a pointedly cursory fashion. Jan is photographed in long shot. The camera’s distance mollifies the character’s evident grief and refuses the viewer the kind of emotional catharsis we commonly associate with such rituals.

Jan’s silence also preserves the sense of mystery about how this turn of events occurred. Is Jan’s ability to walk evidence of the hand of God? Perhaps. Yet it might also be seen as a kind of cosmic joke, proof that humanity’s existence is ruled by forces of Kierkegaardian absurdism.

Rendering the kitsch sublime

Breaking the Waves’ most striking shots appear in the film’s chapter titles. Von Trier worked with the artist Per Kirkeby to create these images using fairly simple computer animation tools. Early in the production, they were described as merely panorama shots. But as the work developed, Trier described them as natural landscapes that evoked the Romantic tradition. This picture-postcard imagery is simultaneously both beautiful and banal, sublime and kitschy.

These more conventionally picturesque shots are further differentiated by Trier’s use of music. Each chapter title is accompanied by a different seventies classic: Elton John’s “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” Mott the Hoople’s “All the Way to Memphis,” Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale,” and David Bowie’s “Life on Mars.” The combination of music and saturated color enable these proleptic titles to function as the antithesis of the film’s handheld camerawork. As Kirkeby himself explained, they contrasted with Müller’s “tropistic intimacy.”

By using these titles to structure the narrative, von Trier preserves the opposition between naturalism and stylization until Breaking the Waves’ final shot. After Jan and his pals give Bess an impromptu burial at sea, they awaken the next morning to the sounds of bells ringing. We know from the scenes of Jan and Bess’ wedding that the source of the sound can’t be the church. Rather miraculously, the bells ring in the clouds unmoored from any terrestrial structure.

Von Trier denies us narrative closure by refusing to explain the meaning of Bess’ actions. But he gives us a kind of formal closure by synthesizing within a single image the different styles of cinematography seen throughout Breaking the Waves.

A riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma

Breaking the Waves has always fascinated me as a study in contradictions. The film is about a miracle, but it is rendered in a style that seems wholly naturalistic. The cast was encouraged to improvise to create the desired sense of spontaneity. Yet Stellan Skarsgård reported that the actors mostly stuck to the script because the dialogue was so good as written. The plot hinges on an answered prayer, but the outcome is such a cruel twist of fate that it leads the viewer to doubt the nature of divinity entirely.

Even the central characters are defined by contradictions. Jan is a worldly outsider whose passions and joie de vivre raise the hackles of the strict Calvinist community where the principal actions take place. Bess was raised inside this overtly patriarchal structure, but she displays such childlike innocence that the inherently sinful nature of humanity somehow eludes her. Only von Trier would make a film in which a character’s adultery and debauchery are construed as holy acts of spiritual self-sacrifice. Bess might seem like a secular saint. But her sainthood is achieved by almost completely abasing herself.

This sense of contrast and contradiction also extends to Trier’s sources for Breaking the Waves. Much of the inspiration for Bess came from a children’s book entitled Gold Heart. The title character is a young girl who enters the woods with bread and other foodstuffs in her pockets. By the end of her journey, she is left naked and empty-handed. Her innate goodness and generosity makes her vulnerable, almost to the point of self-destruction. To quote von Trier, “Gold Heart is Bess in the film. She is goodness in its most absolute gestalt.”

At the other end of the cultural spectrum, though, von Trier incorporates ideas drawn from the films of his Danish predecessor, Carl Theodor Dreyer. The original title of Breaking the Waves was “Love is Everything,” the aphorism that Gertrud’s protagonist wanted as her epitaph. The basic dramatic situation is also reminiscent of Ordet. Like Inger, Jan is bedridden and near death. Like Johannes, Bess is the holy fool whose insistence on faith acts as a counter to science and rationality. And as in Dreyer’s work (La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, Day of Wrath) a woman’s decisive actions put her at odds with a community steeped in religious dogma.

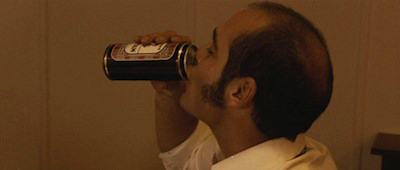

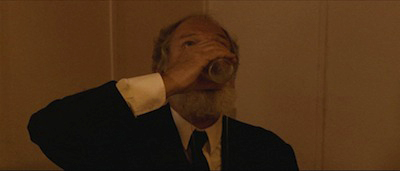

Breaking the Waves accent on contrasts is perhaps best epitomized in one of the film’s lighter moments. During Jan and Bess’s wedding reception, Terry and the Chairman of the church elders chug their beverages.

A close-up shows Terry crushing his beer can in an homage to a similar contest of machismo in Jaws.

It takes a rather dark turn, however, when the Chairman breaks the glass he’s holding with his bare hand.

Although the scene is a bit of a throwaway, it in many ways epitomizes the tonal shifts that mark von Trier’s work as a whole. All of his films contain moments of bleak humor, episodes where laughter slightly obscures the stories’ violent undertones and dark menace. To quote the spirit animals in Antichrist, “Chaos reigns” in the von Trier universe. And whether it is death, nightmare visions, or the literal end of the world, the prototypical von Trier hero confronts this chaos mindful of the immense absurdity of the inexplicable.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and the whole Criterion team for their superb work on the video. A complete list of our FilmStruck installments is here.

Several different editions of Breaking the Waves have been released on home video. I recommend the Criterion dual-format edition. As one would expect, it contains lots of goodies in the extra features. These include deleted and extended scenes, interviews with Emily Watson and Stellan Skarsgård, and selected-audio commentary by von Trier, editor Anders Refn, and location scout Anthony Dod Mantle.

The published screenplay from Faber & Faber includes introductory essays by von Trier, artist Per Kirkeby, and Swedish film critic Stig Björkman.

Collections of interviews with Denmark’s enfant terrible can be found here and here. There’s also a good online interview with von Trier about Breaking the Waves.

The quote from Stellan Skarsgård can be found at Mental Floss.

I also want to thank the film faculty at the University of Copenhagen and Lars von Trier himself. I had the rare privilege of hearing the director discuss his work after a special screening of Antichrist that was arranged for attendees of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference in 2009. I learned a lot from the experience, especially about von Trier’s fondness for mixed pictorial styles within his films.

Breaking the Waves (1996).

ON THE HISTORY OF FILM STYLE goes digital

Dust in the Wind (1986).

DB here:

I was born to write this book.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

Baby-boomer narcissism aside, there are more objective reasons for me to tell you about the book’s revival. It came out in late 1997 from Harvard University Press, and it went out of print last fall. Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel, it has become an e-book, like Planet Hong Kong, Pandora’s Digital Box, and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

The new edition is substantially the original book; the pdf format we used didn’t permit a top-to-bottom rewrite. Errors and some diction are corrected, though, and the color films I discuss are illustrated with pretty color frames, not the black-and-white ones in the first edition. The new Preface and a more expansive Afterword explain the origins of the book and develop ideas that I pursued in later research.

The book analyzes three perspectives on film style as they emerged historically. One, what I call the Basic Version, was developed in the silent era and saw the discovery of editing as the natural development of film technique.

The second version, associated with critic André Bazin, modified that conception by stressing the importance of other stylistic choices, notably long takes and staging in depth. I call this the Dialectical Version because Bazin claimed that these techniques were in “dialectical” tension with the pressures toward editing.

A third research program, spearheaded by filmmaker and theorist Noël Burch, argued that the development of film style was best understood as the ongoing interplay between two tendencies. There’s a dominant style Burch called the Institutional Mode. Responses to that mode are crystallized in alternative practices–the cinema of Japan, for instance, or the “crest-line” of major works associated with modernist trends.

The book goes on to show how a revisionist research program launched in the 1970s built upon these earlier perspectives. Younger scholars sought to answer more precise questions about certain periods and trends. The revisionist impulse is best seen in debates on early cinema, which I survey.

The book so far is historiographic, tracing out other writers’ arguments about continuity and change in film style. In my last chapter I try to do some stylistic history myself. I analyze particular patterns of continuity and change in one technique, depth staging. Certain conceptual tools, like the problem/solution couplet and the idea of stylistic schemas, can shed light on how certain staging options became normalized in various times and places. In turn, directors like Marguerite Duras, in India Song (1975), can revise those norms for specific purposes.

On the History of Film Style was generally well-received. John Belton, while voicing reservations, called it “a very good book. Anyone seriously interested in Film Studies should read it.” Michael Wood wrote in a review that “Bordwell is always sharp and often funny” (I try, anyhow) and called the last section “a brilliant account of the history of staging in depth.” The book has been used in some courses, and I’m happy to learn that there are filmmakers who find it useful. It’s been translated into Korean, Croation, and Japanese.

The book is available for purchase on this page. It’s priced at $7.99, a middling point between our other e-pubs. It’s a bigger book than Pandora ($3.99) and the Nolan one ($1.99), but it’s not an elaborate overhaul like Planet Hong Kong 2.0 ($15). Selling the book helps me defray the costs of paying Meg and digging up color frames. In any event, the new version is much cheaper than the old copies available at Amazon. It’s almost exactly the price of two Starbucks Caffe Lattes (one Grande, one Venti).

The archives and festivals that made the book possible are thanked inside, and they’ve continued to be hospitable and encouraging over the last two decades. Equally supportive are the students, colleagues, and cinephile friends with whom I’ve discussed these issues. So I reiterate my thanks to them all. And I hope this new edition, if nothing else, stimulates both viewers and researchers to explore the endlessly interesting pathways of visual style in cinema.

La Mort du Duc de Guise (1908).

You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t

Casablanca (1943).

DB here:

How could I have written a longish book on 1940s Hollywood and have devoted so little space to Casablanca?

This question was brought home to me when Pauline Lampert, mastermind of Flixwise, asked me to be a guest on her podcast….and to talk about Casablanca. You can listen to our conversation here. Yes, Joan Crawford is involved.

Reinventing Hollywood mentions Casablanca in a few places, but it doesn’t discuss it in the depth it devotes to, say, A Letter to Three Wives or Cover Girl or Five Graves to Cairo or Unfaithfully Yours, let alone Swell Guy or Repeat Performance or The Guilt of Janet Ames. I suppose it’s partly because many of those movies are less famous and more peculiar.

In addition, I confess that I’ve never been a big fan of Casablanca. I admire it as a solid piece of work, but it hasn’t aroused my passion. I’m much more emotionally attached to How Green Was My Valley, The Magnificent Ambersons, Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Meet Me in St. Louis, Mildred Pierce, The Little Foxes, On the Town, and many other movies of its time.

Admittedly, my book doesn’t dwell on most of these either, although I’ve written about most of them elsewhere (including on this site). Basically, I suppose I neglected Warners’ evergreen classic because its canonical status made it unnecessary for me to talk about it. It’s a typical 40s film that everybody knows well, and I guess I trusted that interested readers would apply to it the ideas I float in the book. And another factor may have blocked my considering Casablanca.

Learning from a classic

When historians want to explain changes in film artistry, they have some options. One possibility is to focus on the influential individual, the great artist who inspires successors. Charles Rosen makes this case in The Classical Style, which concentrates on Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven as prime innovators. Traditional film historians have singled out Griffith for this role; I’d add Ozu and Antonioni, in their respective contexts, as significant influencers.

A second option is to zero in on an individual work that became a prototype for other works. The Birth of a Nation, Potemkin, Citizen Kane, and The Bicycle Thieves have played this role in film histories.

A third possibility is to explain change through patterns of collective practice. Creative choices, disclosed in several (perhaps minor) works, propagate through a community and eventually establish norms. This seems to have been what happened with tableau staging and the system of continuity editing. They emerged in bits and pieces, as ad hoc practices that were forged into firm craft practice.

Without denying that some individuals, like Welles and Hitchcock, matter, and without denying that there are powerful models, such as Kane, my book was mostly committed to showing how narrative norms, pressured by competition and other factors, mutate across the 40s ecosystem. This emphasis on norms is one aspect of my research program.

So in re-watching Casablanca for my meeting with Lady P.’s podcast, I noticed some norm-abiding and norm-tweaking things I could have written about.

Classical plot construction (of course). Despite the legend of last-minute screenplay fixes, this is a tightly organized plot. Kristin’ s four-part structural template is in force. After shrewdly distributed exposition, Laszlo and Ilsa stroll into Rick’s at the 25-minute point. At the midpoint (about 50:00), Rick calls Ilsa a whore and she departs to meet Renault. The climax, I’d say, starts around 80:00, when Rick and Ilsa reconcile and he hatches his plan to rescue her and Laszlo.

The parallels are also well-carpentered. Rick is compared to Laszlo; both have been activists. Rick’s also like Renault, in that both are now in-between men, apolitical cynics who will convert to the cause. Ilsa is paralleled to Rick’s high-strung paramour Yvonne, as well as the Bulgarian woman who has concealed from her husband the fact that she traded her body for safe passage out of Casablanca.

Ticking the 40s boxes: Voice-over narration to open the thing? Check. Crisis structure that launches an explanatory flashback? Check.

Franker sexuality and Parker Tyler’s Morality of the Single Instance? Check-plus. When Ilsa comes to Rick’s apartment, they obviously do the thing. He later says they “got Paris back last night.”

And of course it’s a feast of 40s character actors, including Rains, Lorre, Greenstreet (in a silly fez), Veidt, Kinskey, Dalio, and Sakall (aka Cuddles).

Even John Qualen shows up. Casablanca is as much an oddball hangout as Casablanca is.

Domesticating deep focus: Part of the influence of Citizen Kane stemmed from its flaunting of big-foreground depth. A head or an object would be pasted in the front plane, and other figures would stretch out in the distance.

Kane wasn’t the first film to use this strategy, but Welles and Gregg Toland made it vivid by playing out these shots in very long takes. After Kane, 1941 became the Year of the Big Head, apparent in The Little Foxes and, surprisingly, Ball of Fire. Toland shot these.

But these films didn’t treat such compositions in long takes. Wyler and Hawks integrated the wide-angle shots into a standard analytical editing breakdown, using the big foregrounds for orthodox shot/ reverse shot. We see the trend as well in tighter-than-usual over-the-shoulder shots like these from The Maltese Falcon, also 1941.

Curtiz wasn’t as flamboyant a stylist as Welles, but he often added pictorial zest to his shots. He too integrates the wide-angled foreground into standardized setups and editing patterns. Interestingly, his cinematographer was Arthur Edeson, who shot Falcon.

In this respect, Casablanca exemplifies how a new norm was diffused as a toned-down version of a more self-conscious technique.

Smooth visual and verbal narration: This time around I admired the opening passage, with rapid exposition based on adjacency. We start at street level, as the police capture suspected agents of the Free French. One is gunned down, in a moderate deep-space composition. And everything is explained by a chatty pickpocket.

The Bulgarian couple is planted in a panning shot that follows the secret agent and settles on them. (Again, the wide angle accentuates foreground action.)

We get continuity by contiguity. A neat touch: Major Strasser’s plane arriving is glimpsed in conjunction with Rick’s sign, setting up that location well before we visit it. (See still up top.) At the airport, Renault closes the loop, explaining to Strasser that everybody comes to Rick’s. That initiates a dialogue hook to the café, where we’ll spend the next thirty minutes of screen time. And the arrival of Strasser’s plane rhymes neatly with the departure of the one carrying Ilsa and Laszlo at the end.

Motifs, motifs: In a movie where every scene has a famous tagline, I was struck this time by one tweak. Meeting Strasser, Renault says that he’ll round up “twice the usual number of suspects.” In the epilogue, that phrase becomes the nonchalant one everybody remembers, “Round up the usual suspects.” It’s a reminder of corrupt policing, a guarantee that Rick will not be charged, a sign of Renault’s new loyalties, and a contrast to Renault’s initial obedience to the man Rick has just killed.

Seeing eye to eye: I’ve written elsewhere (here and here and here) about the importance of eye behavior in storytelling cinema. In Casablanca, I noticed how Edeson’s cinematography made the women’s eyes glisten. This is standard female lighting for the period, but Ingrid Bergman often gets an extra princess sparkle.

As for Bogart, often a blinker, he lowers his eyes ambiguously when he says that Renault has always kept his word.

When the Bulgarian woman asks about a woman who keeps secret something to save her husband, he manages to shift into a stricken stare for eleven seconds: “Nobody ever loved me that much.”

Actually, Bergman beats him when Sam plays “As Time Goes By.” Ilsa stares, slightly shifting her head but with a largely blank expression, though her mouth opens slightly.

She doesn’t blink for twenty-four seconds. Nearly all the action is in those eyes, as a glint of light jumps from her right eye to her left.

A 1940s movie, over-solemn as it can sometimes be, has this virtue: it can show people thinking.

When you try to study filmmaking norms, often you find that the individual film becomes a “tutor text,” as the French Structuralists used to call it. The movie shows you things about movies. His Girl Friday, I’ve argued, is such a film for me. Maybe Casablanca should be. In any event, we can learn a lot from it, and in the process still enjoy its drama of love sacrificed to political commitment.

Thanks to Pauline for having me on Flixwise. Kristin’s analysis of four-part plotting, first floated in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, has been applied and expanded in my The Way Hollywood Tells It and many of our site entries, as here and here. I discuss Parker Tyler’s Morality of the Single Instance in The Rhapsodes. My deep-focus arguments can be found in Chapter 27 of The Classical Hollywood Cinema and developed at greater length in On the History of Film Style, soon to be available in an updated version on this site. See also this entry and this one and this one.

Casablanca.