William Cameron Menzies: One Forceful, Impressive Idea

David Bordwell

March 2010

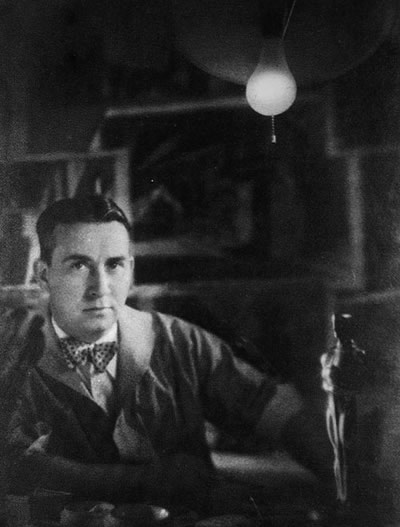

William Cameron Menzies (photo by Karl Struss)

William Cameron Menzies was a wunderkind. He started working on films in 1919

when he was twenty-three; ten years later he won an Academy Award. By the time

he died in 1956, he had participated in over seventy films. Why has nobody written

a book about him?

Don’t look at me. After several years sporadically tracking his career,

I’m aware that this is a mammoth task. Here I want just to float some ideas

about a filmmaker as distinctive, and sometimes as delirious, as Busby Berkeley.

Like Berkeley, Menzies shows that a strong imagination can yank the screen away

from weak directors. Like Berkeley, he shows that the studio system gave considerable

leeway to flamboyant, even peculiar imagery, as long as it could be somehow motivated

by story and genre. Just as important, he shows how exceeding the limits of that

sort of motivation can seem daring, or maybe just cockeyed.

Pictorial beauty and early talkies

Menzies is today remembered chiefly as Gone with the Wind’s production

designer, a term and role that originated on that production. He had already

earned acclaim as art director for Fairbanks’ Thief of Bagdad (1924,

below), Barrymore’s Beloved Rogue (1927), and The Dove (1927)

and The Tempest (1928), which jointly won him his first Oscar. His prestigious

projects included Rosita (1923), Foreign Correspondent (1940),

Korda’s Thief of Bagdad (1940), Meet John Doe (1941), For

Whom the Bell Tolls (1943), Spellbound (1945), and Arch of

Triumph (1948). He took up directing as well, signing Things to Come (1936),

the more cult-friendly Invaders from Mars (1953), several shorts and

B-pictures, and portions of films signed by others, notably Gone with the Wind.

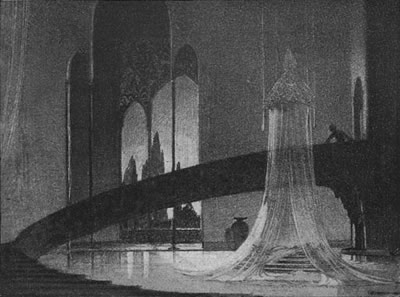

At the start Menzies made his name with monumental sets, often stylized in what

he called “romantic” fashion. These sets were well-suited to costume

pictures and period fantasies. 1 1

After these triumphs, he felt confident enough to declare that the art director

was not merely the person who designed the sets. A stage designer could concentrate

on setting and leave the moment-by-moment unfolding of the action to the director.

But cinema was a pictorial art, built out of motion within the frame and a rapid

succession of shots. So composition took on a special importance. Each shot had

to have “one forceful, impressive idea.” 2 The

art director should sketch the phases of the action, and indicate the camera’s

viewpoint, the lens used, and any trick effects. Once the set was built, the

final filming “reproduces the composition line for line.” 2 The

art director should sketch the phases of the action, and indicate the camera’s

viewpoint, the lens used, and any trick effects. Once the set was built, the

final filming “reproduces the composition line for line.” 3 3

Sound movies had lost the pictorial splendor of the great

silent era, but Menzies thought that could be recovered if someone coordinated

the overall look of the film, including lighting (traditionally the province

of the cinematographer) and figure movement (a task for the director). In 1929–1930,

Menzies began to campaign for this new production role by giving lectures, signing

articles, and publishing his drawings of film shots. Unlike most set designs,

which show empty settings or people in undramatic poses, Menzies’ drawings

look more like what we now call storyboards.

Magazines were happy to publish these dynamic images, and sympathetic journalists

took up Menzies’cause. A New York Times article from 1930 notes

that he makes sketches that follow the script “as closely as possible.

These drawings not only will show the backgrounds for the action but also suggest

the action itself, so that the eye for composition that an artist has will not

be wasted on mere back-drops.” 4 Two

visitors to Hollywood praised his dynamic images and spared a sneer for those

who didn’t understand them. 4 Two

visitors to Hollywood praised his dynamic images and spared a sneer for those

who didn’t understand them.

We must regret that often in the production of the films with which he

has been associated the supposed needs of the story have prevented him from exercising

his full artistic powers in the direction of more vivid picture-making. The number

of directors who know the value of true pictorial art in the movies is yet limited. 5 5

Menzies’ work convinced these writers that the set designer could become

the master planner, “the illustrator of the film.” 6 Significantly,

Menzies began his working life as an illustrator of children’s books. 6 Significantly,

Menzies began his working life as an illustrator of children’s books.

To show the power of his new conception of pictorial design,

Menzies gravitated toward certain types of imagery. Neither his writings nor

his drawings addressed the demands of dialogue scenes, which in early talkies

were necessarily blandly, even awkwardly composed. Filmmakers relied on shooting

with multiple cameras, a tactic that worked against that single bold design that

Menzies thought every shot ought to have. Instead, his imagination sparked to

atmospheric shots and action scenes.

In The Bat (1926) he had already experimented with frames slashed by

diagonals and wrapped in shadows.

In this frame, it’s not the prowling Bat but his shadow that opens the

door.

We shouldn’t be surprised that such images recall German Expressionism.

Menzies acknowledged his admiration for Caligari and The Golem,

and he claimed to have held Murnau in special regard. He was also probably influenced

by his mentor Anton Grot, a set designer who specialized in chiaroscuro and laid

out sets by calculating what lens would be used. 7 7

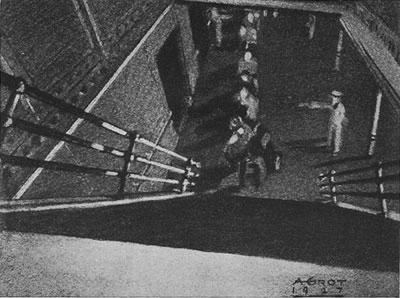

Anton Grot sketch for A Ship Comes In (1928).

By 1929, Menzies had decided that the cinematic illustrator could show his

stuff in passages of violence and “melodramatic action.” Such scenes

achieved greater emotional vibrancy with bold lines, stark tonal contrasts, silhouettes,

extremely high or low camera positions, and—a Menzies favorite—forced

perspective. (From his first film with Grot, The Naulakha, 1918, he

learned that drastic foreshortening could make sets seem bigger.) He also advocated

using wide-angle lenses and building ceilings on sets to permit low angles. 8 8

To exploit such heightened visual expression, Menzies turned to the crime film.

Three films from early sound years show this side of his talent. The least distinctive

is Raffles (1930), an amiable crook melodrama. The bulk of it doesn’t

live up to its flashy opening, in which the gentleman thief breaks into a jewelry

store safe.

Alibi (1929), directed by Roland West, has some passages of inert

dialogue, but it is pretty adroit visually, with police-investigation transitions

that look forward to M and some surprisingly flexible editing for an

early talkie. There’s an occasional proto-depth shot.

Menzies’ love of monumental central perspectives is announced in the

opening sequences of convicts in prison and of Bachmann’s night club.

Menzies claimed much later that Bulldog Drummond (1929) was

the first film in which he prepared “a complete layout of every camera

setup.” 9 The

dream of total preparation on paper was to become a leitmotif across his career,

but even at this point it fell far short of achievement. Bulldog Drummond has

many bland multicamera stretches, and nearly all its striking continuity sketches

are not fulfilled in the final product. Still, many images in these films have

a graphic vividness rare in early talkies. The asylum in Bulldog Drummond is

more or less out of Expressionism, and claw-handed silhouettes evoke Nosferatu. 9 The

dream of total preparation on paper was to become a leitmotif across his career,

but even at this point it fell far short of achievement. Bulldog Drummond has

many bland multicamera stretches, and nearly all its striking continuity sketches

are not fulfilled in the final product. Still, many images in these films have

a graphic vividness rare in early talkies. The asylum in Bulldog Drummond is

more or less out of Expressionism, and claw-handed silhouettes evoke Nosferatu.

Again we find grandiose central perspectives, off-kilter angles, and objects,

particularly lamps and lanterns, dominating the foreground.

Menzies’ love of the vertical dimension of the shot

leads him to split the frame into halves, the top dominated by empty space, the

bottom harboring an abnormally low point of interest.

Such shots subordinate the characters to the overall play of masses and edges,

fulfilling Menzies’ idea that the art director can “create his design

with a broad arrangement of lines and values, and then apply to these lines and

values the realism of architecture, figures, and properties.” 10 It’s

a brutally Modernist approach: Chisel out the composition as a pure play of graphic

energies, and then fit your setting, props, and players into it.

Even in action scenes, the human figures are dominated by the larger design.

They move through vast spaces, often overwhelmed by stabbing verticals and plunging

perspectives. One shot in Alibi turns a cityscape into nightmarish outcroppings,

and there is a chilling moment when a fleeing crook leaps across rooftops and

then falls backward into an apparently bottomless canyon between buildings. 10 It’s

a brutally Modernist approach: Chisel out the composition as a pure play of graphic

energies, and then fit your setting, props, and players into it.

Even in action scenes, the human figures are dominated by the larger design.

They move through vast spaces, often overwhelmed by stabbing verticals and plunging

perspectives. One shot in Alibi turns a cityscape into nightmarish outcroppings,

and there is a chilling moment when a fleeing crook leaps across rooftops and

then falls backward into an apparently bottomless canyon between buildings.

Drummond peers into the laboratory of the asylum, and we get a shot with an

outsize hanging lamp in the foreground; when he fires his pistol and extinguishes

the light, his silhouette in the background pops into view.

Eyes of an astigmatic worm

The 1929–1930 crook movies look as if Menzies had struck a bargain with his directors:

You handle the dialogue scenes and give me the atmospheric establishing shots,

the connective tissue, and the chases. The ultimate example of the one-off effect

is probably The Green Cockatoo, filmed in Britain in 1937 but not released

until 1940. Menzies was brought on to direct it, but it was taken from his hands

and redone by William K. Howard and Thornton Freeland, both uncredited. Only

one sequence, a noirish cat-and-mouse game on a staircase, has visual flair, but it doesn’t go beyond

what we sometimes find in American crime films of the era.

More thoroughgoing was Menzies’ contribution to two

fantasies. For Alice

in Wonderland (1933) he collaborated on the script and concentrated on creating

ingenious special effects, none of which display the compositional dynamism of

the 1929–1930 films. Things to Come (1936) was something else

again. Menzies was given the post of director, but he worked under two powerful

overseers, producer Zoltan Korda and writer H. G. Wells, who had negotiated a

degree of control over the project unprecedented for an author. The film has

become a classic for its vision of a world ravaged by war and healed by science

and rational planning. Along with the set designer Vincent Korda, Menzies gave

the city of the future an even more towering vertical thrust than we find in Metropolis.

The fantastic premise of Things to Come gave Menzies freedom to indulge

his love of unusual angles. Art director Lyle Wheeler told him he was “no

damn good” as a director because all he cared about were steep compositions. “He

wanted to photograph ceilings and didn’t give a damn what the actors were

saying.” 11 11

Menzies liked low angles because they made for cleaner design. Straight-on

angles swathed the players in distracting décor, but a face seen against

sky or ceiling stood out vividly. In interiors, ceiling corners and the edges

of walls contributed V-shaped vectors. High angles could yield sharp diagonals

just as easily.

The important thing was to avoid the neutral presentation, to charge every

moment with the sort of visual energy seen in Art Nouveau or Art Deco or the

Modern Style. With the aim of dynamizing every image, Things to Come imbues static dialogue scenes with a mild version of the interplay between figures and

setting that we find Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and Ivan

the Terrible. An underground cell is dominated by a huge pipe that pokes

into every shot. Another interior displays vectors on rooftop and floor.

The motif is sustained later when Oswald Cabal comes forward and his head

remains pinched within the wedge formed at the back of the set. Menzies was starting

to conceive the scene as not simply a string of striking images but as a decorative

accompaniment to the dramatic development.

These efforts seem a bit forced, I think, because Menzies simply lacks Eisenstein’s

resourcefulness in finding graphic motifs to fill his frames. Things to Come’s

strongest effects, it seems to me, appear in the frightening opening that juxtaposes

announcements of impending war with imagery of Christmas shopping. The anxiously

pitched shots, accompanied by harsh musical cuts in Arthur Bliss’s score,

evoke a society dancing toward catastrophe.

It’s fitting that when the bombardment starts, the first building blown

to bits is the gargantuan Modern Style cinema.

The sequences that Menzies is said to have directed of Gone with the Wind betray

his signature techniques: silhouettes, diagonal masses, low-slung camera positions,

central perspectives alternating with skewed ones, and brooding Gothic effects.

His fondness for a very low horizon line, perhaps inspired by Soviet filmmakers,

can be seen in the “burning of Atlanta” sequence, yielding probably

the most astonishing shot in the film.

It seems to rework a more stylized image scheme we find in a montage sequence

in Things to Come.

Once you’re exposed to the Menzies Touch, it’s hard not to see

even an apparently simple shot, like that of Rhett Butler at the foot of the

stairs, as a geometrical display. Squint, and it’s easy to see the curving

banister culminating in his torso while the flooring and shadows behind him mark

out his head.

Beyond those sequences he actually directed, Menzies designed the overall

look of Gone with the Wind, including its changing color palette. 12 But

did he dictate the film’s breakdown into shots as well? Selznick famously

advocated “pre-cutting” as a time- and money-saver, claiming in a

1937 memo, “I hope to have Gone with the Wind prepared almost

down to the last camera angle before we start shooting.” 12 But

did he dictate the film’s breakdown into shots as well? Selznick famously

advocated “pre-cutting” as a time- and money-saver, claiming in a

1937 memo, “I hope to have Gone with the Wind prepared almost

down to the last camera angle before we start shooting.” 13 13

This would seem to be the ideal test of Menzies’ conception of the “film

illustrator.” Yet by January of 1939, once shooting had started, Selznick

had to admit that “A picture of this size in importance cannot be created

to the last inflection in advance of production; there must be a certain leeway

in production as we go along.” 14 That

leeway was necessary partly because Selznick was constantly rewriting scenes,

sometimes the day before shooting. By May, to hurry the schedule along, he was

urging staff to “substitute simple angles that do not take time” for “elaborate

angles”—of course, a Menzies speciality. 14 That

leeway was necessary partly because Selznick was constantly rewriting scenes,

sometimes the day before shooting. By May, to hurry the schedule along, he was

urging staff to “substitute simple angles that do not take time” for “elaborate

angles”—of course, a Menzies speciality. 15 Alan

David Vertrees’ painstaking study of the scripts and the surviving continuity

sketches and storyboards confirms that the film often diverges from the “pre-cut” designs. 15 Alan

David Vertrees’ painstaking study of the scripts and the surviving continuity

sketches and storyboards confirms that the film often diverges from the “pre-cut” designs. 16 16

Vertrees argues persuasively that Menzies’ role

was not only to secure a unifying look for the film but to serve as the producer’s

representative in discussions with the director, the cinematographer, and Technicolor

consultants. Menzies became in effect the hand and eye of Selznick’s conception

of the movie. He was, according to Selznick in another memo, “the final

word on these matters…responsible for the physical aspects of the production

and for the color values of the production and any difference [of opinion among

the creative staff] should be settled by him.” 17 17

On the whole, Gone with the Wind displays a much

more subdued (some would say subtle) approach to design and framing than we find

in Menzies’ 1929–1930

crime films and in Things to Come. The other films on which he collaborated

at the time display his typical bargain: a few bursts of visual panache sandwiched

within more orthodox shooting and cutting. Mr. Lucky (1943), directed

by H. C. Potter, is a brisk and orthodox RKO item that occasionally spares a

moment for a flashy transition or a flamboyantly centralized composition, as

when the gambler Joe learns to knit. Most striking is a very early pair of shots

in which Joe, the owner of a gambling cruiser, strides down a row of slot machines

and finds one paying out. The reverse shot shows a maintenance man.

The shockingly low horizon lines and the perspective that seems to go on forever

return us to Menzies’ love of the monumental image created by forced perspective.

Chopping off the human figure and planting it at the very bottom edge of the

frame is somewhat better motivated in this exchange from Korda’s Thief

of Bagdad (1940), when the negative space at the top of the shot does duty

for the looming djinni.

Menzies’ influence is more pervasive in John Cromwell’s So

Ends Our Night (1941). Centering on refugees from Nazi-occupied countries,

it took a political stand that was quite brave for early 1941. Yet for Menzies

this was a film of “melodramatic escape” and so justified “violation

of perspective.” In one daffy passage he explains:

If it heightened the drama

to shoot a tree from the viewpoint of an astigmatic worm sitting on a leaf of

that tree, or even from that of the tree looking at itself [!], we did in so

far as the new 28mm lens and our imagination would permit. 18 18

The

result is another film that anticipates Kane through cramped compositions,

lowered ceilings, wide-angle lenses, and skewed vanishing points.

In the climax, a man’s leap from a building is shown as a faint shadow

flitting down windows from landing to landing.

The film’s tight facial close-ups pay off in a graceful tracking shot

in which a wife under surveillance by the authorities is followed, nearly cheek

to cheek, by her husband urging her to divorce him. 19 19

Did Menzies somehow abduct these films from their named directors? Surely his

stature in the industry by 1940 gave him considerable clout. By now he was frankly

claiming control over a film’s look. The production designer, he told the New

York Times, has the task of “coordinating every phase of the production

not covered by dialogue and action of the players.” 20 With

breathtaking casualness, he declared that the director’s job is to work

with actors while the production designer supervised the cinematographer, set

designer, costume designer, and other artisans. How much pressure he was able

to exert on each of these productions, I can’t say, but clearly he had

even more control over his work with Sam Wood. 20 With

breathtaking casualness, he declared that the director’s job is to work

with actors while the production designer supervised the cinematographer, set

designer, costume designer, and other artisans. How much pressure he was able

to exert on each of these productions, I can’t say, but clearly he had

even more control over his work with Sam Wood.

Where to put the camera

Sam Wood was older than Menzies by several years, but he started directing at

about the same time as the young set designer began his career. From A City

Sparrow (1920) on, Wood became known as a reliable journeyman at Famous

Players-Lasky before shifting to MGM in the late 1920s. There he turned out comedies

and sports movies before taking charge of the Marx Brothers’ Night

at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Races (1937). After directing Goodbye,

Mr. Chips (1939) in England, Wood left MGM in 1939 to go independent. He

made Raffles (1939) for Sidney Howard’s independent company and Kitty

Foyle (1940) for RKO.

Wood had seen Menzies’ prowess at full stretch on Gone with the Wind,

for which Wood shot several sequences. After Sol Lesser acquired Thornton Wilder’s

Pulitzer-Prize winning play Our Town, William Wyler was slated to direct

but had to drop out. Lesser turned to Wood, and the production design went to

Menzies. This began a three-year collaboration on five films that are among the

most visually striking, not to say narratively peculiar, in Hollywood cinema.

In Our Town (1940), The Devil and Miss Jones (1941), Kings

Row (1942), The Pride of the Yankees (1942/1943), and For Whom

the Bell Tolls (1943) Menzies’ pictorial imagination reigned. We have

testimony on one project from James Wong Howe:

Kings Row I loved doing. William Cameron Menzies designed the

sets and did the sketches for the shots; he’d tell you how high the camera

should be. He’d even specify the kind of lens he wanted for a particular

shot; the set was designed for one specific shot only, and if you varied your

angle by an inch you’d shoot over the top. . . . Menzies created the whole

look of the film; I simply followed his orders. Sam Wood just directed the actors;

he knew nothing about visuals. 21 21

Menzies, according to a contemporary, put it more abruptly: “Sam Wood

never knew where to put the camera, so I told him.” 22 22

But what did Menzies tell him, through his drawings? As we’d expect, silhouettes,

big settings, and bold perspectives—some maniacally centered and others

skewed, but all driving the eye toward a visual node.

But now Menzies seems to be playing

with solutions to a lingering problem: How to give dialogue sequences the visual

punch that he applied to transitions and scenes of physical action? How to give

conversations pictorial beauty? “He

could take the most ordinary thing in a picture,” noted art director Ted

Haworth, “and make it so cinematically fascinating.” 23 23

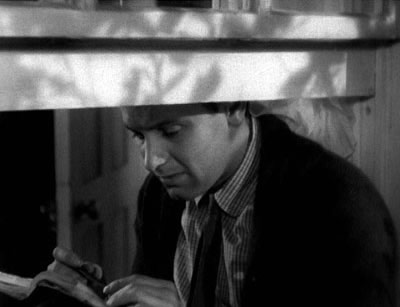

One sign of this impulse is Menzies’ effort

to rethink the close-up. In the Wood collaborations of 1940–1943, the camera

is set rather close to the players. (This may have been one of Woods’ contributions

to the pair’s style.)

Formerly a director of big sets and hollow spaces, Menzies now builds vigorous

compositions around the human face.

The films Menzies directed gave

such shots a special thrust by cutting abruptly from a long shot to a rather

big close-up without the way station of a midsize shot. A cameraman once said

to him: “Let’s pull back to

a long shot now and show the chin and hair.” 24

Sometimes the faces are vastly enlarged. Haworth again: “Bill Menzies’ philosophy

was that if you were going to show a close-up, make it closer than any close-up

has ever been.” 24

Sometimes the faces are vastly enlarged. Haworth again: “Bill Menzies’ philosophy

was that if you were going to show a close-up, make it closer than any close-up

has ever been.” 25 25

Even when the faces are not preternaturally

large, to a greater degree than in Things

to Come or Gone with the Wind they are caught within the same

V’s of setting and lighting that were formerly reserved for long shots.

Most conservatively, that means letting corners or radiating shadows in the background

give prominence to a player.

But sometimes that means having diagonals slash not across a landscape but

across a face.

Instead of canting the camera, Menzies lets lighting and wall edges create

quasi-abstract diagonals.

Another way to dynamize dialogue is through depth. That can be accomplished through

the sort of big foreground and distant background that Welles and Toland made

famous.

More often, Menzies prefers to use the wide-angle lens to jam several faces

in the frame rather close to one another.

Aggressive depth would of course become a common compositional

strategy for other directors in the 1940s, but Menzies was playing with unusual

forms of it fairly early. The Wood collaborations recast shot/reverse shot in

somewhat eccentric ways.

Perhaps most startling is his habit of pushing faces to the very bottom of

the shots, in the way he would handle bodies in long shots in the crime films.

Perhaps one shot in Our

Town sums up the emerging Wood-Menzies look. A pattern

of light and architecture creates a wedge in which a face and a shadow stand

out starkly, while the low angle and the calculatedly unbalanced framing let

the traditional center of interest—Emily, who may be dying—at the

very bottom edge.

In all these tactics, the frame edges play unusually strong roles, cropping

visual elements and chopping up the scene’s space. Menzies had little use

for camera movement, so his shots, the result of his hundreds of sketches in

the script margins, come to resemble panels in comic strips.

Our Town takes a drama usually performed on a

bare set and steeps it in Gothic chiaroscuro. It’s a useful reminder that

this play, so often taken as a hallmark of middlebrow affirmation, is actually

shot through with foreboding; early on, the stage manager tells us that a character

we’ve

just met will die some years later. If Copland’s score brings out the poignancy

and yearning in the story, the imagery is far grimmer.

Perhaps Menzies and Wood decided that if the movie version of the play had to

have props and settings, those should be stylized somehow. So everything looms.

A pump broods over a kitchen counter, and chickens look monstrous when seen

from below. The monumental fantasy sets of Menzies’ youth have become a gigantism of the homespun.

The dominant strategy for the dialogue scenes is tightly framed depth, with faces

pressed close to one another.

Call this “compressed deep space”: The frame is packed with elements

arrayed in marked depth, but the distances between planes are not great.

Broader shots exhibit the same jamming of the frame. The two primary households

in the town are cramped, and the crosscutting between them not only sets up narrative

parallels but invites us to see them as extensions of the same low-lying architecture.

In these interiors the figures scarcely have room to move; even Emily as a ghost

has to slip in between her mother and her earlier self.

True “deep-focus” imagery is reserved for the graveyard hallucination,

with mother and dead daughter in the same frame. Anticipating the special effects

in Citizen Kane, this shot was accomplished with a split screen.

In plot, Kings Row is the anti-Our Town. “A

good clean town,” says the sign under the credits, but you wouldn’t

know it from the contagion of madness that sweeps through the movie. “A

good place to raise your children”? The respectable fathers of Kings Row

lock up their wives and daughters and amputate the legs of the lads who dare

to come courting. Class warfare is rampant, old women weep powerlessly, and the

girl loved by the timid young physician behaves like one demented. She will be

poisoned by her father.

This inspires the young doctor Parris to head to Vienna to study psychiatry.

Returning to Kings Row, he will find plenty of business, and his reward will

be a new version of his beloved. The childhood scenes are shot straightforwardly,

but as adulthood pulls the characters into a spiral of hysteria, the film introduces

hard-edged shadows, thunderstorms, canted angles, oppressive ceilings, oversize

lamps, big close-ups, and a flagrant deep-focus technique. When Parris calls

on his ailing grandmother, we get an image more complicated than the celebrated

shot of Susan’s suicide in Kane.

The carafe is a decoy, taking up a huge chunk of the frame but inconsequential

compared to the syringe. That grows in importance as Parris lunges forward to

discover it.

He realizes that the old woman’s care has passed to the palliative phase,

but the framing hides his face. At this point the nurse Anna enters the background.

As she comes forward to explain that the disease is cancer, the camera tilts

up and her head fits perfectly into the vectors formed by the ceiling corners.

They close the door as Anna tells Parris that his grandmother will die in

a few days.

Anna moves offscreen to cry as Parris returns to the bedroom to stare down

at his grandmother.

A less flamboyant but equally moving scene takes place

around another bedside, when after recoiling from the woman who has nursed him,

the anguished amputee Drake clutches the bedstead and then acknowledges his need

for her by stretching one arm into the distance. The wide-angle lens exaggerates

the burst of his arms to the foreground and then accelerates the thrust of his

right hand back toward Randy.

Shot in the summer of 1941, after the spring release of Citizen Kane, Kings

Row looks as if Welles’ film had given Menzies permission to push

further in the expressive and Expressionistic direction taken in Our Town.

Yet the extremes are motivated to a considerable degree by the melodramatic fluctuations

of the action. As the plot moves toward resolution, the florid style abates and

we’re back to the more orthodox technique of the childhood scenes.

Between Our Town and Kings Row, Wood

and Menzies made a comedy, and its visual style is even more offbeat than what

we see in its mates. The

Devil and Miss Jones centers on workers’ agitation at a department

store. The owner, the pompous and life-denying mogul John P. Merrick, goes undercover

disguised as a new salesman. Soon he comes face to face with his store’s

petty bosses, obtuse policies, and quarrelsome customers. He admires Mary Jones

and her coworker Elizabeth, whom he will later start to romance. The ebullience

and self-sacrifice of Miss Jones and her agitator boyfriend Joe lead Merrick

to embrace their cause. At one point he ends up picketing himself.

The film continues

the compressed deep-space look of Our Town, with

several faces packed alongside one another, but what is most striking is a tactic

of unbalanced and decentered framing of those faces.

Menzies is one of the few filmmakers (apart from Ozu and Mizoguchi) to give

the bottom third of the frame its due. We saw one example in the Mr. Lucky slot-machine

battalions above, but there it was a one-off flourish. The Devil and Miss

Jones, made two years earlier, supplies so many instances that you start

to see this compositional oddity as normal.

At one point the key event, Mary peering under Merrick’s elbow, lies

almost flat along the bottom frameline.

It’s hard to provide a robust functional explanation

for these shenanigans. I’m inclined to take them as pure experiments, since

they create a sort of visual rigidity that is hard to integrate with comedy.

(The relevant comparison here might be the way that Gregg Toland’s deep-focus

schemas somewhat freeze up the players in Hawks’ Ball of Fire.)

The

decentering strategy is perhaps better motivated in the film that followed Kings

Row, Pride

of the Yankees. This story of Lou Gehrig follows one conventional biopic

arc: Origins—Striving—Success—Personal

Happiness—Tragedy of a Career Cut Short. (Another example is The Glenn

Miller Story, 1954). But there’s nothing ordinary about the film’s

visual design. We get the Menzies bottom-heavy look from almost the start, with

the second scene shoving the boy Lou’s face down against the frame edge.

Shot/reverse shot is even more off-balance than in Miss Jones.

And where another film would play out the pathos of Sam’s response to

Lou’s final address in a close-up, Wood-Menzies tucks it into the lower

left corner, highlighted by architectural diagonals and the other sportswriters’ stares.

Again, this pictorial strategy is hard to square with traditional genre motivation.

It seems to be an effort to create a deliberately offbeat style that not only

binds the film together but serves as an authorial signature. (If you think the

handwriting might have been Wood’s, consider that his other baseball yarn

of the period, The Stratton Story of 1949, bears no trace of these techniques.)

For Whom the Bell Tolls changes the game somewhat. A large amount of

it was filmed in exteriors (the Sierra mountains doing duty for Spain), and in

Technicolor. In some respects, it is Menzies’ most flamboyant achievement

of the era, a feast of pictorial design laid over a somewhat static plot.

Given three days to prepare to blow up a strategic bridge,

Robert Jordan, an American fighting for the Republican cause, must join a band

of guerrillas. Among them is Maria, a refugee who was raped by the Nationalists

when they took over her town. The nominal leader of the guerrillas is the shifty

Pablo, but the driving force is his wife Pilar, who can mobilize the men vigorously.

Robert and Maria fall in love quickly; the drama is provided by the band’s

efforts to plan the demolition and Pablo’s wavering support of the mission.

From

the very first shot after the opening title, we are in Menzies territory. Characteristic

jet-black silhouettes, tightly packed into the frame, are even more striking

in color.

The huddled gatherings of the band are remarkable for sustaining depth of

field with the slow Technicolor process, and action scenes are propelled by stark

vectors provided by rock formations or logs.

Menzies’ eye for expressive color remains remarkable; when Robert crouches

over the dead Anselmo, smoke curls into the frame like a shroud.

Most of the scenes between Robert and Maria are shot straightforwardly, as

if setting off their relationship from the war maneuvers filmed in low angles

and steep perspectives.

But the decentered framing, which can look so arbitrary and showoffish, becomes

a motif associated with the couple and reaches a kind of climax in the film’s

final stages. We get the decentering when they reconnoiter, and much later when

they’re reunited after the firefight.

At the end, when the wounded Robert

urges Maria to go, she is turned and pulled away by Pilar, and the two women

sink below the frameline.

This sort of downward departure has

been a signal of closure in earlier Wood-Menzies efforts. Lou Gehrig steps down

into a block of shade as he retires from baseball, and the Stage Manager of Our

Town leaves

by literally dropping out of sight.

Going solo

Each of the Wood-Menzies films of 1940–1943 deserves more detailed analysis than

I can supply here. There’s also the matter of their last collaboration

on Ivy (1947), a more pictorially restrained enterprise.  26 But

I’ll conclude by considering the films of the 1940s and 1950s that Menzies

directed. 26 But

I’ll conclude by considering the films of the 1940s and 1950s that Menzies

directed.

Two of these, Drums in the Deep South (1951) and the 3-D effort The

Maze (1953), are of striking banality (except for the occasional decentered

head). By contrast, Invaders from Mars (1953) indulges in Menzies’ eccentricities

of set design and composition pretty freely. Admirers of the film point to the

Caligaresque forest and the forced perspective of the jail cell.

There are as

well his customary bare walls and strenuous viewpoints.

Once seen, Invaders

from Mars isn’t forgotten, but the stylistic

signatures don’t seem to me to compensate for arid and schematic designs,

lugubrious pacing, and special effects of a pretty jejeune nature. The fantastic

plot offers no ballast for Menzies’ urge to float into abstraction. I’d

argue that two other films that he signed benefited from realistic constraints

on his pictorial imagination.

In The Whip Hand (1951) a

journalist on a fishing trip to a Minnesota town discovers a nest of Soviet scientists

bent on poisoning Chicago’s

water supply. The mystery is reasonably well-sustained, despite an over-explicit

opening scene showing Russian officers pinpointing the town on a US map. The

film employs solid character players, particularly Raymond Burr as a hotelkeeper

exuding false bonhomie. Menzies’ predilictions are somewhat toned down

now because his more moderate solution to the problem of enlivening dialogue

had become standard practice. Thanks to Kane and perhaps the Menzies/Wood

films, the tight, deep-space imagery of the conversations were stock in trade

of American cinema of the period.

What looked striking in 1940 had become

commonplace ten years later. But Menzies was still able to invoke bursts of graphic

tension, as when the innkeeper and a lab technician are caught in a hail of bullets

and a pattern of striped shadows.

Menzies’ most worthwhile solo

feature, I believe, is Address Unknown (1944).

Like So Ends Our Night, it’s a wartime drama with a strong political

message. Two fathers, Martin Schulz and Max Eisenstein, are partners in an art

gallery. Max’s daughter Griselle accompanies Martin’s family to Germany,

while her fiancé, Martin’s son Heinrich, stays in San Francisco

with Max to run the gallery. Once in Germany and exposed to Hitler’s rise,

Martin chooses to conform and even asks Max, who is Jewish, to stop writing to

him. At the same time, Griselle is launched on a stage career but courageously

challenges the censor. Out of cowardice Martin lets her be caught and killed.

Thereafter he starts to receive messages, apparently from Max, that the Nazis

intercept and take to be in code. Gradually Martin finds himself alone to face

the wrath of the authorities. It’s revealed that Heinrich has sent the

letters in revenge for the loss of Griselle. He has deliberately sent his father

to his death.

Unusually for a Hollywood movie, the film doesn’t build its plot around

a sympathetic protagonist. Martin nervously slips into pleasing his Nazi masters,

and Griselle becomes a figure of our allegiance only briefly. It would be too

much to call this a Brechtian exercise, but the refusal to tell the story through

the normal arc of the Griselle-Heinrich romance and the concentration on the

mechanics of correspondence give the film a drier, more detached air than we

find in most wartime propaganda. The usual iconography of swastikas, flags, and

armbands was deliberately omitted, so that the drama is really that of two elders,

an exchange of offspring, and the contrast between a weak father and a courageous

daughter in a moment of political crisis.

Visually Address Unknown is quite satisfying. No longer are Menzies’ stock

images sprinkled over the screenplay; now they become part of a consistent, albeit

unusual style. Menzies’ vast corridors and offices find a natural justification

in the government bureaucracy that Martin joins and the official style of National

Socialism.

Menzies’ beloved decenterings now serve dramatic purposes, most memorably

during Griselle’s scandalous stage performance. At one point the director

lurks backstage in a composition recalling Ivan the Terrible.

Likewise, treating Max’s art gallery in train-tunnel fashion risks looking

ponderous until we realize that the axis running from the office to the front

door of the showroom gets developed across the film. First it is a space for

welcoming a customer.

But when Max learns of Griselle’s death, the looming ceilings are replaced

by a floor as lonely as a plain.

Martin’s decline is played out through a cluster of motifs of setting

and lighting. He and his wife move into their German estate, and patterns of

circles in the windows are laid over them.

Later, as Martin starts to fear every mail delivery, Menzies uses the circular

shapes to enclose the butler striding to the postal box.

As the nets close in, Martin peers through the window pane.

At the climax, however, he is caught in a new patterns of light: a strip across

the eyes, a network across his body.

He watches his executioners arrive

through a squarish grillwork.

This modulation in imagery is recapitulated

when the epilogue reveals Heinrich as the author of the damning letters. First,

he stands in the office looking down the gallery at Max, and a reverse angle

presents him in a grid.

Our final shot of him offers a stripe

of light comparable to that crossing his father’s face.

The motifs link

the son to the father whom he has condemned to death. The pattern is simple,

but it shows that Menzies had the capacity to go beyond one-off effects and build

an associative chain that accompanies the drama as a sort of pictorial score.

The “film illustrator” has gone beyond illustration

to subtly shape the movie’s visual texture.

Legacy of an idea

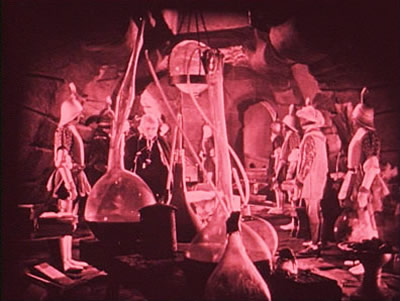

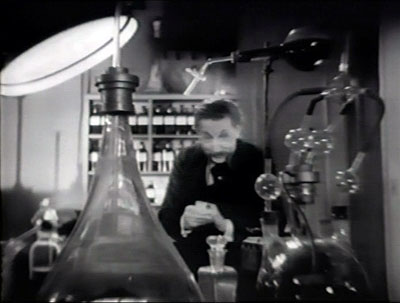

You can make the case that Menzies is an overblown, repetitive illustrator. He

recycles images over and over. The beakers bulging on lab tables are there early

on.

The Beloved Rogue (1926)

Bulldog Drummond (1929)

Invaders from

Mars (1953)

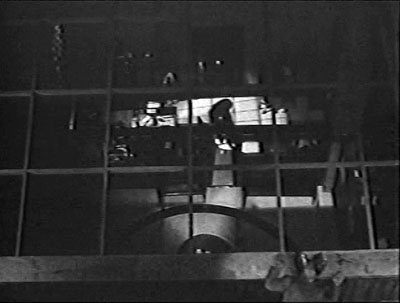

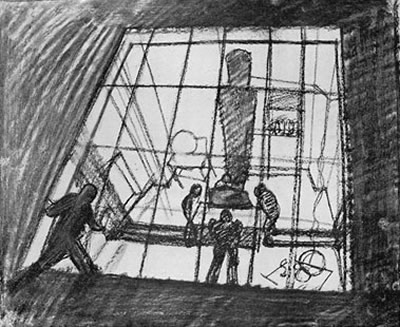

One schema, that of the plunging view

through a high window, reappears in movies twenty years apart.

The Bat (1926)

A drawing for Bulldog

Drummond

Bulldog Drummond (1929)

Whip Hand (1951)

As early as 1930,

Harry Alan Potamkin was deploring Menzies’ “arty” impulses, “which

depend for their appeal on the public’s general ignorance of the antiquity

and derivation of the devices employed, expressionistic light-designs and Méliès

virtuosity.” 27 And

undeniably arty he was. Although he paid lip service to the Hollywood idea that

visual style should be “motivated” and that “every shot must

contribute in some manner to the story,” he makes movies of flagrant artificiality. 27 And

undeniably arty he was. Although he paid lip service to the Hollywood idea that

visual style should be “motivated” and that “every shot must

contribute in some manner to the story,” he makes movies of flagrant artificiality. 28 In

the article celebrating shooting from the viewpoint of an astigmatic worm, he

also says, “My work is the less noticeable the better it is.” 28 In

the article celebrating shooting from the viewpoint of an astigmatic worm, he

also says, “My work is the less noticeable the better it is.” 29 Like

so many Hollywood practitioners, he was caught between a desire to try something

wild and the need to justify it, at least in public, as fulfilling traditional

purposes. 29 Like

so many Hollywood practitioners, he was caught between a desire to try something

wild and the need to justify it, at least in public, as fulfilling traditional

purposes.

Apart from his own films, his example

evidently spurred several new creative practices in studio cinema. If he did

not invent the storyboard, he surely popularized it, and along with it the new

role of production designer. As early as 1941, Harry Horner, production designer

on The Little Foxes, was declaring

that the task of the art director was that of “designing a visual score

to the film manuscript. Each camera set-up should be considered according to

its dramatic value, and also according to its visual artistic composition.” 30 30

Menzies’ manner of dynamizing dialogue scenes through vivid compositions

was taken up by his successors. More broadly, the general 1940s trend toward

locked, centrifugal images may owe something to Menzies as well as to Welles

and Wyler. As Boris Kaufman put it: “The space within the frame should

be entirely used up in composition.” 31 Menzies’ love

of the vertical axis, the corners of the image, and the vital frame edges fulfill

that purpose, and he may have inspired others as well. Perhaps Welles learned

something from him; Anthony Mann certainly did. 31 Menzies’ love

of the vertical axis, the corners of the image, and the vital frame edges fulfill

that purpose, and he may have inspired others as well. Perhaps Welles learned

something from him; Anthony Mann certainly did. 32 More

recently, those who admire the absurdly inflated portrayal of corporate life

seen in The Hudsucker Proxy ought to thank Menzies for leading the way.

The Coen brothers’ distended wide-angle mode, using both deep central perspective

and skewed angles for 1930s-ish montage sequences, is a contemporary equivalent

of his forceful images. 32 More

recently, those who admire the absurdly inflated portrayal of corporate life

seen in The Hudsucker Proxy ought to thank Menzies for leading the way.

The Coen brothers’ distended wide-angle mode, using both deep central perspective

and skewed angles for 1930s-ish montage sequences, is a contemporary equivalent

of his forceful images.

During the 1930s a depth aesthetic

was emerging as one creative option, but while Wyler pursued its more stable

possibilities, Menzies pushed it to an unusually frantic pitch. Then, as the

deep image was becoming normalized in the early 1940s, he was eager to take it

in unexpected directions. His oddities, pursued with zeal and a considerable

degree of commercial success, don’t fit into any

tradition neatly. That may be enough to guarantee his continuing value.

[For some personal reflections on my

interest in Menzies, see this

blog entry.]

1 :

For background on Menzies’ silent cinema work, see Beverly Heisner, Hollywood

Art: Art Direction in the Days of the Great Studios (Jefferson NC: McFarland,

1990), 41–49.

2 : Menzies, “Cinema

Design,” Theatre Arts Monthly 13 (September 1929), 681.

3 :

Menzies, “Pictorial

Beauty in the Photoplay,” Cinematographic Annual vol. 1 (Hollywood

CA: ASC, 1930), 177. See also “The Layout for Bulldog Drummond,” Creative

Art 5 (October 1929), 729–734.

4 : Anonymous, “As

a Director Views the Art of Settings,” New York Times (12 January

1930), 113.

5 : Jan and Cora Gordon, Star-Dust

in Hollywood (London: Harrap, 1930), 181.

6 : Gordons, 179.

7 : Fred J. Balshofer

and Arthur C. Miller, One Reel a Week (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1967), 130.

8 : Menzies, “Pictorial

Beauty,” 176.

9 : Ezra Goodman, “Production

Designing,” American Cinematographer 26, 3 (March 1945), 82.

10 : Menzies, “Cinema

Design,” 682.

11 :

Lyle Wheeler, quoted in Mary Corliss and Carlos Clarens, “Designed for

Film,” Film

Comment 14, 3 (May–June 1978), 57.

12 :

On Gone

with the Wind’s color design, see Scott Higgins, Harnessing the

Technicolor Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s (Austin: University of Texas

Press, 2007), Chapter 7. A very thorough account of the making of the film, with

superb color illustrations, can be found in Ronald Haver’s David O.

Selznick’s Hollywood (New York: Knopf, 1980), 236–311. Haver’s

book includes other information on the collaboration of Selznick and Menzies.

13 : Memo from

David O. Selznick, ed. Rudy Behlmer (New York: Viking, 1972), 151.

14 : Memo from

David O Selznick, 189.

15 : Memo from

David O. Selznick, 206.

16 : Alan David Vertrees, Selznick’s

Vision: Gone with the Wind and Hollywood Filmmaking (Austin: University

of Texas Press, 1997), Chapters 3 and 4.

17 : Memo from

David O. Selznick, 190.

18 : William Cameron

Menzies, “Production Designed By—Mr. Menzies, Specialist in Illusion,

Reveals a Couple of His Fancy Tricks,” New York Times (1 December

1940), X5.

19 : Kent Jones provides

an eloquent appreciation of this shot and the film as a whole in “State

of Desire,” Film Comment 43, 3 (May/ June 2007), 22.

20 : William Cameron

Menzies, “Production Designed By,” X5.

21 : Quoted in Charles

Higham, Hollywood Cameramen: Sources of Light (London: Thames and Hudson,

1970), 88.

22 : Richard Sylbert

quoted in Vincent Lo Brutto, By Design: Interviews with Film Production Designers (Westport,

CT: Praeger, 1992), 52.

23 : Quoted in Lo

Brutto, By Design, 21.

24 : Quoted in Ezra

Goodman, “Production Designing,” 83.

25 : Quoted in Lo

Brutto, By Design, 21.

26 :

David Cairns offers a discerning, more affirmative account of Ivy here.

27 : Harry Alan Potamkin, “Reelife,” Close

Up 7 (December 1930), 391.

28 : Quoted in Scot

Holton and Robert Skotack, “William Cameron Menzies: A Career Profile,” Fantascene no.

4 (1978), 6.

29 :

Menzies, “Production

Designed By—,” X5.

30 : Harry Horner, “Designing

Films,” Theatre Arts 25, 11 (November 1941), 794.

31 :

Quoted in Edward L. de Laurot and Jonas Mekas, “An Interview With Boris

Kaufman,” Film Culture 1, no. 4 (Summer 1955): 5.

32 :

See John Hambly and Patrick Downing, The Art of Hollywood: Fifty Years of

Art Direction (London:

Thames Television, 1979), 4, 90–97.

|