Archive for the 'National cinemas: South Korea' Category

Talking pictures: Wisconsin Cinematheque screenings and podcasts

Hill of Freedom (2014).

DB here:

Crises make people resourceful, and the Covid-19 virus has spurred workers in film culture to try new ways to feed movie appetites. The tactics include making films available virtually. Our Wisconsin Cinematheque has joined this movement by offering titles on a weekly basis in cooperation with friendly distributors.

Along with the virtual screenings, the crew of Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, and Mike King have created podcasts discussing the movies available for viewing. This week’s program is Hong Sangsoo’s Hill of Freedom. You can see it by going here. This ingratiating movie is one of my favorite Hong titles; I reviewed it at Vancouver here.

You can hear Mike King and me discussing Hill of Freedom in our Cinematheque podcast. The series has already hosted discussions with New York Times critic Manohla Dargis and Twentieth Century Fox archivist Schawn Belston. The team has also corralled filmmakers James Runde, Dan Sallitt, Mark Goldblatt, Peter O’Brian, Mary Sweeney, and not least the wonderful Bill Forsyth. Go here for the complete list.

Thanks to Mike King, Ben Reiser, and Jim Healy for setting up this pleasant encounter. Keep in touch with our Cinematheque!

Bill Forsyth has been one of our blog’s best friends, so do check in on our encounters with him: at Ebertfest in 2008 and at Antwerp in 2015. The Antwerp visit led to a fine interview as well.

Tom Paulus interviews Bill Forsyth in the Antwerp Summer Film College of 2015.

The trim, tight movie: Three variants at Vancouver

Parasite (2019).

DB here:

As a student of storytelling, I recognize that we can enjoy loose, episodic plots. But I also admire the shrewd craft of constructing a movie that develops a situation in precise, logical, yet surprising ways. Things may be resolved neatly, or not, but the satisfaction comes from the way that characters pursuing goals create conflicts, overcome obstacles, and change (or not) in the course of the action. American studio cinema developed its own version of this in what Kristin and I have called “classical Hollywood” plotting. Other countries have borrowed that model, adapting it to new needs but still keeping the storytelling trim and tight.

Three films on display at this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival illustrate some options. All have won acclaim at other festivals and constitute A-productions in their local industries. I enjoyed all of them, and I liked learning how broad principles of narrative construction can be treated in significantly different ways.

Storming the basilica

François Ozon’s By the Grace of God, a prizewinner at Berlin this year, turns Spotlight (2015) inside out. The American film follows the investigation of a news team bringing priestly pedophilia to light; it’s a detective story, with the victims serving as witnesses to the crime. By the Grace of God concentrates on the victims’ search for justice, and finds an unusual structure to give each one due weight.

The film is based on a real case in Lyon. The film starts with businessman Alexandre Guérin accusing Father Preynat of abusing him as a child. Surprisingly, Preynat admits he did the deed, so there’s no mystery to be solved. With the statute of limitations expired, the Church authorities decline to punish Preynat. He’s kept in service, and his duties still associate him with children. The only thing that worries Cardinal Barbarin is that Preynat didn’t apologize when Alexandre confronted him.

A pious Catholic, Alexandre trusts that if he appeals high enough in the Church hierarchy (even up to the Pope), some action will be taken. He is rudely awakened to the cynical willingness of Barbarin to stall and cast a smokescreen over the case. Alexandre decides to file a legal complaint and to find other victims to join him.

At this point, Ozon’s script takes an intriguing turn. The plot drops Alexandre and introduces us to another victim, François Debord, who is a fairly militant atheist. Investigating Alexandre’s charges, the police call on François’s parents. He told them of the abuse at the time, but they pressured him to stay quiet. Now he embarks on a crusade to find other victims to speak out. For some of them, the statute of limitations may not have expired.

Alexandre becomes a minor player in this stretch of the film, meeting François occasionally to plan strategy, but François is the motor of the action. His zeal leads him to yet another victim, Emmanuel Thomassin. We now follow him and learn how his life has been damaged quite severely by Preynat’s abuse.

Eventually the three men find more victims willing to go public, and by cooperating they confront the Church’s coverup.

With three sections each lasting 45-50 minutes, Ozon has mounted a block-construction plot (although without explicit chaptering). He has compared it to a relay race, with the story impulse passed like a baton from one character to another. And each phase of the action raises the stakes: growing proof of the Church’s malfeasance, a broader survey of the consequences of the crimes.

Ozon has also said that he tried to distinguish each of his three protagonists’ sections stylistically. Alexandre’s phase of action has highly economical narration, using the exchange of letters and emails (read in voice-over) to move the action swiftly, forcing us to keep up at every moment. When the action shifts to the flamboyant, web-savvy François, the emphasis falls on building online support for an organization. Emmanuel’s painful story is treated with more intimacy and empathy; the other men have overcome their childhood traumas and have buoyant families, but Emmanuel is adrift.

By the Grace of God has the carpentered solidity of Ozon’s Frantz (2016). If we can say that the French “Tradition of Quality” of the 1940s and 1950s persists today, it’s surely here in this taut, elegant piece of storytelling.

City on fire

Stylistically, Les Misérables doesn’t look as sleek and controlled as Ozon’s film. It’s shot in the free-camera style that’s now common throughout the world: handheld shots, fast cutting, tight framing on faces, lots of panning to follow the action. When cops brace three women on the street we get a rapid-fire exchange in the manner of Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Although we’re basically on one side of the confrontation, the cutting is somewhat freer than in classic continuity, as the above shot of Stéphane indicates. To emphasize the quasi-sexual gesture of Chris checking the young woman’s fingers for the smell of pot, the editing jumps the line before returning to the main setup.

Les Misérables, directed by Ladj Ly, is not quite as pure an example of the free-camera approach as Young Ahmed, (also shown at VIFF) because it affords a greater degree of “camera ubiquity.” It crosscuts among lines of action, and it relies on reaction shots that the Dardennes avoid. Still, the purpose is to immerse us, smashmouth fashion, in each scene’s conflict.

And there’s plenty of conflict. Stéphane Ruiz has joined a team of tough cops patrolling an impoverished Parisian suburb teeming with immigrants. To keep things under control Chris, the team leader, has formed alliances with drug gangs and the boss of the territory. Gwada, a Muslim cop, backs Chris loyally.

The main action, which consumes around 24 hours, shows Stéphane trying to bring a measure of humanity to the confrontations between his unit and the local residents. A petty crime escalates into a burst of police brutality, captured on video by a boy’s drone. The second half of the film puts the cops in conflict with one another and an increasingly outraged community ready to take on both the police and the gang leaders.

Ly has made short films and web videos, and while growing up in the banlieue projects he documented police actions.

For five years I filmed everything that went on in my neighborhood, particularly the cops. The minute they’d turn up, I’d grab my camera and film them, until the day I filmed a real police blunder.

Ly filmed the 2005 riots as well (365 Days in Montfermell), as part of the filmmaking collective Kourtrajmé. Les Misérables is called that partly because this is the district where Hugo wrote his masterpiece. “I wanted to show the incredible diversity of these neighborhoods. I still live there: it’s my life and I love filming there. It’s my set!” In 2018 Ly established a filmmaking school in Montfermell.

Although Ly comes from the world of documentary, he has a shrewd sense of fictional plotting. A prologue shows little Issa among thousands of Parisians celebrating France’s World Cup victory (above). It’s an image of diversity within national unity, but also a bit of narrative priming that makes us sympathetic to the boy. The rising tension of the action, from a childish prank through increasingly horrific scenes (one in a lion’s cage had me trembling) to a final cataclysm, is carefully constructed out of a series of misunderstandings, brutal decisions, overreactions, and desperate survival maneuvers.

There’s solid motivation and foreshadowing. The drone is established early as the all-seeing eye of the projects, steered by the withdrawn boy Buzz. Stéphane has reluctantly transferred to the Parisian police from the provinces because he wants to be near his son, in the custody of his ex-wife. This information prepares us for his sympathetic gestures toward the children of the projects. And just before the climax, Ly’s script gives us a pressurized nighttime pause, a sequence that cuts among all the adults we’ve seen trying to adjust to the day’s turmoil. Next day all hell will break loose.

Les Misérables shared the Jury Prize at Cannes last May with another VIFF entry, Bacunau. (Comments on this coming soon.) In the US it will be distributed, who knows how, by Amazon.

Class struggles

Viewers of Memories of Murder (2003), The Host (2006), and Mother (2009; also here) know that Bong Joon-ho has a fine hand with mystery, suspense, and abrupt plot twists. His skill is on full display in Parasite, Palme d’or winner in Cannes and already considered one of the most striking films of 2019.

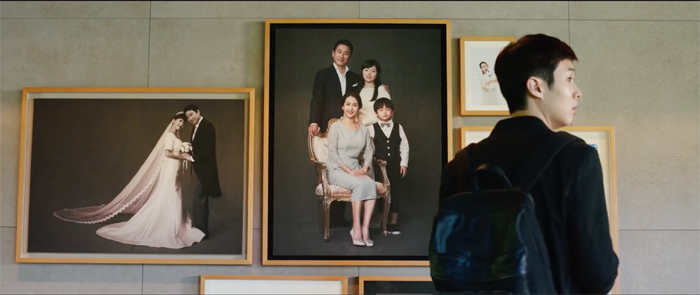

As suits the Age of Inequality, the action centers on two families. The Kims live in a crammed basement and struggle to get by. When the son Ki-woo gets a job tutoring the daughter of the rich Park family, he schemes to insert all his family members into the household. (This recalls the stratagems of the play and film Kind Lady.) The Kims’ adroit manipulation of the Parks, especially the insecure helicopter mom, provides mordant comedy. But in a long central scene, the Kims’ scam starts to unravel. They’re shocked to discover what actually goes on in the splendid mansion they’ve taken over.

Bong’s skill in shooting, staging, and composition seems effortless. Neither as academic as Ozon or as nervous as Ly, his deliberate style makes every sequence build to a neat point. The contrast between the Park house, perched high on a hill, and the Kims’ basement apartment, is echoed in vertical camera movements that carry us up and down through locales. (Here, in more instances than one, the poor live underground.) Parasite‘s opening camera setup, a view of the street through the Kims’ window, recurs at various points to mark stages of the action. Here nighttime violence erupts in the street outside.

The Kims’ barred view contrasts with the spacious picture window at the Park mansion. Fussy as ever, Bong places a comparable shot of the Kim window at the very end.

Bong plants significant motifs through the film. He forgets nothing. Cub scouts, Morse code, peach allergies, and the smell of poverty pay off in comedy while supplying thematic resonance. The parallels between the married couples are enhanced by the introduction of another husband and wife who have launched their own desperate scheme. The climax, an orgy of rich folks’ complacency, brings all together in a shocking but not ultimately surprising confrontation.

I had almost called this entry “The well-made movie,” indicating not only my praise for the films but also their kinship with the dramatic tradition of the “well-made play” (pièce bien faite). That was one powerful set of principles for plot-building. If you construe that form narrowly (as the Wikipedia entry does), these films don’t completely fit it. I think that Ibsen, Shaw, and those who followed owe more to that form than is generally admitted.

In any case, the impulse toward tight construction, full motivation of characters’ actions (usually guided by a goal), and a rising arc of conflict leading to a decisive climax–these design features, so manifest in the well-made play, have carried over to the cinema since the rise of the feature film in the 1910s.

Today’s films have a look and feel that seem of our moment, but their underlying “engineering” principles are surprisingly indebted to a long-running tradition. Those principles can be deployed, revised, and reversed in a great many ways–as these three films show.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on the general principles of “classical” construction, see this entry on The Wolf of Wall Street. In our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema Kristin traces some literary and dramatic sources of the format.

On the “free-camera” shooting style, see our blog entry on Toni Erdmann (viewed at VIFF back in 2016). We discuss the emergence of the technique in Chapter 25 of the fourth edition of Film History: An Introduction.

By the Grace of God (2019).

Vancouver 2018: Crime waves

Burning (2018).

DB:

It’s striking how many stories depend on crimes. Genre movies do, of course, but so do art films (The Conformist, Blow-Up) and many of those in between (Run Lola Run, Memento, Nocturnal Animals). The crime might be in the future (as in heist films ), the ongoing present (many thrillers), or the distant past (dramas revealing buried family secrets).

Crime yields narrative dividends. It permits storytellers to probe unusual psychological states and complex moral choices (as in novels like Crime and Punishment, The Stranger). You can build curiosity about past transgressions, suspense about whether a crime will be revealed, and surprise when bad deeds surface. Crime has an affinity with another appeal: mystery. Not all mysteries involve crimes (e.g., perhaps The Turn of the Screw), and not all crime stories depend on mystery (e.g., many gangster movies). Still, crime laced with mystery creates a powerful brew, as Dickens, Wilkie Collins, John le Carré, and detective writers have shown.

We ought, then, to expect that a film festival will offer a panorama of criminal activity. Venice did last year and this, and so did the latest edition of the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some movies were straightforward thrillers, some introduced crime obliquely. In one the question of whether a crime was committed at all led–yes–to a full-fledged murder.

Smells like teen spirit

Diary of My Mind.

Start with the package of four Swiss TV episodes from the series Shock Wave. Produced by Lionel Baier, these dramas were based on real cases–some fairly distant, others more recent, all involving teenagers. The episodes offer an anthology of options on how to trace the progress of a crime.

In Sirius a rural cult prepares for a mass suicide in expectation they’ll be resurrected on an extraterrestrial realm. The film focuses largely on Hugo, a teenager turned over to the cult by his parents. Director Frédéric Mermoud gives the group’s suicide preparations a solemnity that contrasts sharply with the food-fight that they indulge in the night before. Similarly, The Valley presents a tense account of a young car thief pursued by the police. Locking us to his consciousness and a linear time scheme, director Jean-Stéphane Bron summons up a good deal of suspense around the boy’s prospects of survival in increasingly unfriendly mountain terrain.

Sirius and The Valley give us straightforward chronology, but First Name Mathieu, Baier’s directorial contribution, offers something else. A serial killer is raping and murdering young men, but one of his victims, Mathieu, manages to escape. The film’s narration is split. Mathieu struggles to readjust to life at home and at school, while the police try to coax a firm identification from him. This action is punctuated by flashback glimpses of the traumatic crime. The result explores the parents’ uncertainty about how restore the routines of normal life, the police inspector’s unwillingness to press Mathieu too hard, and the boy’s self-consciousness and guilt as the target of the town’s morbid curiosity.

This insistence on the aftereffects of a crime dominates Diary of My Mind, Ursula Meier’s contribution to the series. This too uses flashbacks, mostly to the moments right after a high-school boy kills his mother and father. But there’s no whodunit factor; we know that Ben is guilty. The question is why. Ben’s diary seems to offer a decisive clue (“I must kill them”), but just as important, the magistrate thinks, is his creative writing under the tutelage of Madame Fontanel, played by the axiomatic Fanny Ardent. Because she encouraged her students to expose their authentic feelings, Ben’s hatred of his father had surfaced in his classroom work. Perfectly normal for a young man, she assures the magistrate. No, he asserts: a warning you ignored. The shock waves that engulf onlookers after a crime, the suggestion that art can be both therapeutic and dangerous, the question of a teacher’s duty to both her pupils and the society outside the classroom–Diary of My Mind raises these and other themes in a compact, engaging tale.

Last hurrah of (movie) chivalry

Chinese director Jia Zhangke is no stranger to criminal matters. His films have dwelt on street hustles, botched bank robberies, and hoodlums at many ranks. Ash Is Purest White is a gangster saga, tracing how a tough woman, Qiao, survives across the years 2001-2018. Initially the mistress of boss Bin, Qiao rescues him from a violent beatdown using his pistol. She takes the blame for owning a firearm. Getting out of prison, Qiao tracks down the now-weakened Bin, who has taken up with another woman.

Ash Is Purest White tackles a familiar schema, the fall of a gang leader, from the unusual perspective of the woman beside him, who turns out to be stronger than he is. Most of the film is filtered through her experience, and along with her we learn of Bin’s decline and betrayal, along with his integration into the corrupt and bureaucratic capitalism of twenty-first century China. The second half of the film shows Qiao forced to survive outside the gang’s milieu. A funny scene plays out one of her scams: picking a prosperous man at random, she announces that her sister, implicitly his mistress, is pregnant. Just as important, Qiao’s adventures allow Jia to survey current mainland fads and follies, including belief in UFO visits.

Among those follies, Bin suggests, is a trust in mass-media images. As Ozu’s crime films (Walk Cheerfully, Dragnet Girl) suggested that 1930s Japanese street punks imitated Warner Bros. gangsters, so Jia’s mainland hoods model themselves on the romantic heroes of Hong Kong cinema. They raptly watch videos of Tragic Hero (1987) and cavort to the sound of Sally Yeh’s mournful theme from The Killer (1989). They derive their sense of the jianghu--that landscape of mountains and rivers that was the backdrop of ancient chivalry–not from lore or even martial-arts novels but from the violent underworld shown on TV screens.

Bin’s decline is portrayed as abandoning those ideals of righteousness and self-sacrifice flamboyantly dramatized in the movies. But Qiao clings to the imaginary jianghu to the end. She explains to him that everything she did was for their old code, but as for him: “You’re no longer in the jianghu. You wouldn’t understand.” You can respect his pragmatism and admire her tenacity, but he’s still a feeble figure, and she’s left running a seedy mahjongg joint–one much less glamorous than the club she swanned through at the film’s start. Appropriately for someone who got her idea of heroism from videos, we last see her as a speckled figure on a CCTV monitor.

From dailiness to darkness

Burning.

Often the crime in question is presented explicitly, but two films leave it to us to imagine what shadowy doings could have led to what we see. In Manta Ray, by Phuttiphong “Pom” Aroonpheng, we get the familiar motif of swapped identity. A Thai fisherman finds a wounded man in the forest and nurses him back to health. The victim is a mute Rohinga whom the fisherman names Thongchai. They share a home and the occasional dance and swim, even a DIY disco.

But who attacked Thongchai in the forest, and why? And what is the connection to the unearthly gunman who paces through the forest, bedecked in pulsating Christmas bulbs? And what makes the foliage teem with gems glowing in the murk? Somewhere, there has been a crime.

Manta Ray accumulates its impact gradually, with the scenes of the men’s routines giving way to mystery when the fisherman vanishes and Thongchai (named by the fisherman for a Thai pop singer) is trailed by a ninja-like figure clad in a red cagoule. A disappearance and a reappearance (of the fisherman’s wife) punctuate moody scenes of trees and sea. The opacity of the action makes a political point: offscreen, Thais brutally hunt down the refugee Rohingas. But the critique of anti-immigrant brutality is intensified by the lustrous cinematography (Aroonpheng was a top DP). You can feel the texture of the planks in the cabin and the sharp edges of the gems that fingers root out of the forest floor. This is probably the most tactile movie I saw at VIFF.

Then there was Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Lee started his career strong and has stayed that way. The slowly paced, Kitanoesque gangster story Green Fish (1997) and Peppermint Candy (1999), with its reverse-order chronology, both achieved local popularity and established him as a fixture on the festival circuit. Oasis (2002), a daring romance of a disabled couple, won a special prize at Venice. Secret Sunshine (2007) brought Lee even more widespread fame. Like the episodes of Shock Waves, it dealt with the aftereffects of a horrific crime. Virtually everyone I know who saw the film remembers most vividly a particular scene: the heroine, having converted to Christianity and at last ready to forgive the perpetrator, visits him in prison. It’s one of the most nakedly blasphemous scenes I’ve ever seen, carried off with a shocking calm. Crime–this time, a gang rape–is also at the center of Poetry (2010), with another mother facing familial tragedy.

Most of these plots, particularly Poetry, are rather busy, but Burning is more stripped down (though not short). Lee Dong-su maintains the shabby family farm while his father is in jail awaiting trial. In town Dong-su meets Haemi, a former classmate now running sidewalk giveaways.

She lures him into her life by asking him to feed her cat while she’s in Africa, but before she leaves they start an affair. But he seldom breaks into a smile, favoring a puckered-lip passivity. After their coupling, we get his POV on a blank wall.

This turns out to be the first of many disquieting passages. Between bouts of tending livestock, feeding Haemi’s cat, and masturbating to her picture, Dong-su gets mysterious phone calls with no one on the line. He meets Haemi at the airport only to discover that she’s formed a friendship (or more?) with the suave Ben, whose gentle courtesy makes Dong-su feel an even bigger bumpkin. Soon the three are hanging out together, but at parties Dong-su can only stare at Ben’s yuppie friends. Dong-su, who wants to be a writer, is a fan of Faulkner, but Ben compares himself to the Great Gatsby.

After a long night of relaxing at the farm, with the men watching Haemi dance topless, she disappears. A black frame, a dream of a burning greenhouse, and Dong-su is left alone halfway through the movie. What happened to Haemi? And why does Ben say he enjoys torching greenhouses? Dong-su turns detective,

Lee is a master of pacing, and the deliberateness of the film delicately turns a romantic drama into a critique of entitled lifestyles and then into a psychological thriller. We are locked to Dong-su’s consciousness except for a couple of telltale shots of Ben calmly studying his rival from afar. We get Vertigo-like sequences of Dong-su trailing Ben and probing for clues and perhaps having more dreams. At the same time, Dong-su starts writing, as if Haemi’s disappearance has inspired him, but he finds more violent ways to release his simmering bewilderment.

After only one viewing, I didn’t find Burning as devastating a film as Secret Sunshine or Poetry, but I’d gladly watch it again and probably I’d see more in it. Lee manages to sustain over two and a half hours a plot centering on three, then two principal characters. He has earned the right to soberly take us into the mundane rhythm of a loner’s life and then shatter that through an encounter with two enigmatic figures who may be playing mind games. As with Manta Ray, we have to infer some of the action behind the scenes, but that just shows that in cinema, classic or modern, crime can pay.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Japadog, a Vancouver landmark.

Patchwork imagination: Lee Kwangkuk’s framed and frayed stories

Romance Joe (2011).

DB here:

Seeing Hong Sangsoo’s The Day a Pig Fell in the Well at the 1997 Hong Kong Film Festival didn’t convince me that he was a major talent. That happened two years later, when I saw The Power of Kangwon Province at the same event, and again at Cinédécouvertes in Brussels. At Hong Kong, and again at Brussels, I saw The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2001). In those days, Hong made a movie every year or two, like your ordinary director.

I was impressed. I included Kangwon Province as an example of modern South Korean cinema in our second edition of Film History: An Introduction (published 2002), and it’s still there in our upcoming fourth edition. A year earlier, I had brought Hong to our Wisconsin Film Festival for what I think might have been his first retrospective–if three films count as a retrospective. And I drew on a scene from The Virgin as an example of subtle ensemble performance in Figures Traced in Light (2005). And I contributed an essay to Huh Moonyung’s anthology Hong Sangsoo (Kofic/Seoul Selection, 2007).

I was impressed. I included Kangwon Province as an example of modern South Korean cinema in our second edition of Film History: An Introduction (published 2002), and it’s still there in our upcoming fourth edition. A year earlier, I had brought Hong to our Wisconsin Film Festival for what I think might have been his first retrospective–if three films count as a retrospective. And I drew on a scene from The Virgin as an example of subtle ensemble performance in Figures Traced in Light (2005). And I contributed an essay to Huh Moonyung’s anthology Hong Sangsoo (Kofic/Seoul Selection, 2007).

My apologies for playing an egocentric cinephile game. Boasting aside, though, I want to express genuine satisfaction at Hong’s sustained creativity. He has become prolific but not stale; every film offers the viewer and the filmmaker himself fresh challenges. What attracts me is his simplicity of means and the way he devises narrative games that make satiric points (usually about male vanity) without seeming mannered or precious.

He has gotten ever-greater recognition, as evidenced by the current Film Comment cover story, Dan Sullivan’s perceptive appreciation of his three (!) 2017 releases. Even more startling is a real high-culture breakthrough. In its print editions over the years, The New York Review of Books has resolutely ignored Kiarostami, Kitano, Wong Kar-wai, and Hou Hsiao-hsien, to pick some exceptional directors who hit their strides in the 1990s. But the 7 December NYRB boasts Phillip Lopate’s wide-ranging essay introducing Hong to its readership.

So he’s one of those overnight successes who took twenty years. Moreover, it’s gratifying to see that recently this body of work has had some influence, most apparent for me in the work of Lee Kwangkuk. Today I want to offer some notes on an intriguing, quietly ambitious filmmaker working in the shadow of Hong.

Two shorts

Hard to Say.

Lee learned on the job, assisting on Hong’s Tale of Cinema (2005), Woman on the Beach (2006), Like You Know It All (2009), and Hahaha (2010). His films have the crystalline cinematography and color design of Hong’s, and he has learned how to make movies that consist largely of two-person dialogues, shot in long, poised takes punctuated at just the right moment by a close-up. He has cast several actors who have appeared in his mentor’s films.

As with Hong, Lee’s characters tend to be artists: filmmakers in Romance Joe (2011), actors in A Matter of Interpretation (2014), and novelists in A Tiger in Winter (2017). They have romantic liaisons, but they also spend inordinate stretches of time wandering streets, hanging out, and drinking immense amounts of soju. And like Hong, Lee has experimented with storytelling formats.

Most obviously, there are embedded stories. Early and late Hong explored a modular narrative, broken into two or three blocks, with story lines splitting or converging. At first blush, Lee developed this in a more traditional direction, inserting stories within stories, Russian-doll fashion. His two favored forms of this are the flashback and the dream.

We get both in the short Hard to Say (2012). In a playground, a young woman declares her love for a young man, who puts her off, suggesting he’s been attracted to another woman, a guitarist. “You can imagine all you want,” he says, but he’s not going to be her boyfriend.

Saddened, the woman finds a guitar abandoned in the woods, and starts to listen to it. Cut to the boy, who’s now searching for the singer who played a song he loves. (Are we in a flashback?) He finds the young woman of the first scene, but as a different character, a poised and meditative guitarist. She tells him, via a flashback, how her father forbade her to learn the guitar, so she learned to play it in her imagination, in shadow strums and plucks.

When she finally got an instrument, she found she could play it perfectly. After her tale ends, she asks him to hug her.

Abruptly we’re back on the playground, where the original young woman is waking up from sleep. Now the boy is interested in her and offers to walk her home. The guitarist’s claim for the power of imagination is vindicated.

The fact that we’re not sure where the girl’s dream begins is conventional, but also characteristic of the way that Lee frays the boundaries of his embedded stories. And the fact that the boy has fallen in love with the girl while in her dream shows the porousness of the subjective stretch that’s embedded. Hard to Say provides a miniature example of how Lee’s characteristic plot structure prompts us to see stories within stories, and then refuses to keep them sealed tight. Early in a film, we might be led to expect a solidly implanted flashback, but soon the whole frame is revealed as less objective than we might think.

The transforming power of the imagination is given a more somber treatment in another short, Soju and Ice Cream (2016). A young woman fruitlessly selling insurance policies meets an old woman who asks her to fetch some ice cream in exchange for a basket of soju bottles. In one bottle our heroine finds a slip of paper, a sort of reformation vow written by the woman: “Do not give up. Make a plan. Stop drinking. Keep smiling.” Suddenly, in what appears to be a flashback, we’re watching the old woman write the note, in an apartment tagged with Post-its. She gets a phone call from her landlord evicting her.

The old woman casually blows into a bottle she’s just drained and, as if by magic, the girl hears and feels the breath.

Now able to listen to the old lady’s phone call, she discovers that the woman’s daughter treats her as harshly as she has treated her own mother.

The girl bursts in on the old woman–in the past? in her mind?–and pours her resentment of her mother into a criticism of the old lady for taking loved ones for granted.

Back at the ice-cream stall, she snaps out of her reverie to discover that the bottles are gone and the old woman is long dead. This touch of the fantastic has given her the chance to empathize with her mother and, in a long coda, to implore her sister to heal the family wounds. Here imagination yields not wish fulfillment, as in Hard to Say, but the recovery of duty and devotion.

Dream on

A Matter of Interpretation.

A Matter of Interpretation tackles dream narratives on a bigger scale. Yeon-shin, an actress, stalks out of a brutally awful avant-garde play because, among other problems, there is no audience. As she wanders the city, she recalls breaking up with her boyfriend a year or so ago. Now, on another bench, Yeon-shin meets a detective who claims to be able to interpret dreams. So she tells her dream of attempting suicide in a car halted in a field of goldenrod.

But a thumping from the trunk interrupts her, and she finds a man tied and gagged there. He’s the detective who had asked her about the very dream he’s now in. In a flashback he explains he found himself in the car, contemplating suicide, before she arrived.

We’re left with a dream that contains a flashback, as in Hard to Say. But it’s not a veridical one, since the man finds the pill bottle empty and Yeon-shin finds it full. So it’s a dream within a dream? Moreover, her dream features a character whom the dreamer did not know…until she recounted the dream. We’re entitled to take what we see as a version of what Yeon-shin told the detective, I suppose, with him plugged into the role that some faceless man played in the original dream. Or maybe she’s just fibbing. Or maybe what we’re seeing is a free elaboration of the situation, a startling variant without any source in her mind. The uncertainty, of course, is the point.

In any case, the detective interprets Yeon-shin’s dream as being about her dumping her ex, with the recurring car symbolizing her career failure. And now he explains his skill as a dream interpreter through a flashback to his caring for his ill sister, and her recounting a dream about a customer.

As the film goes on, we get to meet Yeon-shin’s boyfriend, Woo-yeon, through a string of flashbacks framed by her telling. Later in the day, he winds up on the bench with the detective, who probes one of his dreams–in which, again, the car and the detective appear.

Back in reality, in a string of precise repetitions, Woo-yeon follows Yeon-shin’s wanderings through the streets. And that night, exhausted and depressed, she has another dream that brings Woo-yeon back into her life.

Like Hard to Say, A Matter of Interpretation offers some legible time shifts–conventional framing situations for flashbacks–in order to give the imaginary scenes escape hatches, as the detective slips into the dreams recounted by the lovers. By the end, we’ve been prepared for their paths to cross, not least because Yeon-shin’s final dream presents a reconciliation she seems to yearn for.

Telling it backwards and sideways

There aren’t any dreams per se in Romance Joe, but it’s no less committed to the zigzag contours of the imagination. The plot presents several different time schemes (although some may be fictitious), and they don’t stay neatly separate. Again, there’s a benevolent contamination of one zone by another.

A young filmmaker has disappeared. His parents come to his friend Dam Seo to investigate.

Again, what seems to be a tidy flashback shows Dam meeting with the son, who rants that he’s run out of stories.

In a standard film, we’d return to Dam Seo and the parents for more discussion. Instead we’re now in a village, where a third filmmaker, director Lee, is dumped by his producer and ordered to conjure up a story pronto. Lounging in the hotel, Lee is brought coffee by a waitress who admires one of his films, A Good Guy, for its “critical approach to narrative.” Pleased, Lee asks her to stay the night, and she agrees, for money. He reminds him, she says, of another director who visited the town, the man she calls Romance Joe.

Joe, it turns out, is the missing, unnamed director the parents are worried about; but it’s not at all clear that Dam Seo is narrating this encounter of Lee and Rei-ji. How could he know about them? His flashback simply bleeds into a new set of scenes with these other characters.

Rei-ji tells of Joe’s coming to town, and in flashback we see him wandering the streets, then checking into a hotel and trying to write. Despondent, he starts to slash his wrist. That scene is interrupted by a flashback to Joe as a teenager finding a young woman, Cho-hee, with slashed wrists in a forest. He takes her to the hospital. At this point, the flashback-within-a-flashback ends. Rei-ji, delivering coffee, finds the bleeding Joe and hurries away.

Here, about thirty minutes in, we finally return to the initial situation of Dam Seo talking to the parents about their missing son. The father is dismissive: “All these kids today wasting their lives on film.” But the mother is sympathetic to Dam Seo and asks about his work. He says he’s working on a story, and he tries it out on them. This launches what can only be called a hypothetical sequence, about a boy visiting a town in search of his missing mother. But soon enough the boy encounters Rei-ji, the coffee-girl/hooker.

And the boy’s tale frays further when it’s interrupted by a scene of Cho-hee in the forest, starting to slash her wrists and then being discovered by the teenage Joe. There’s crosstalk among what ought to be distinct realms–Dam Seo’s script versus Cho-hee’s reality, one speaker’s story versus another’s.

The rest of the film will intercut these story lines, with some peculiar interferences. Rei-ji tells Lee of meeting Joe, who says he has no more stories and is tired of them. But after spending the night with her he tells (or seems to tell) the story of himself as a teenager, and his love for Cho-hee. The stories intersect unexpectedly, with the vagabond boy revealed to be present when Rei-ji discovers Joe’s suicide attempt. Again, though, the boy is initially presented as purely fictitious, a character in Dam Seo’s uncompleted screenplay. A similar disconnected connection involves the name “Romance Joe.” It’s the nickname Rei-ji gives the anonymous director she meets, but much later in Cho-hee’s story, it’s the title of the film Joe as a student is making in Seoul. By canons of plausibility, Rei-ji could know nothing of this.

All this is hard to visualize in my prose, but I think you can see how the firm outlines of flashback episodes or embedded tales become hazy. By the end, two filmmakers want to film this tangled tale. Director Lee sees that it could become a thriller. Joe, encouraged to tell his own story by Rei-ji, seems to be rejuvenated and wants to revisit the forest of his childhood. Yet it’s not clear that either will make the movie–especially after we hear Rei-ji confide to another waitress that you just have to tell your clients what they want to hear. (So is her story about Romance Joe’s writer’s block calculated to mend Lee’s own?) The film’s final image, harking back to an Alice in Wonderland motif, suggests that the whole patchwork of stories might be pure fabulation.

Far from being a simple imitator of Hong, Lee has taken some of his experiments in fresh directions. Some of these involve abstract form, others style; his shots tend to be prettier, and he’s more likely to break a scene into reverse angles. Other differences lie in the emotional tint of the film. Hong’s films are usually comedies, however mordant. Lee’s films have a grimmer tone. Although Hard to Say is light-hearted, Soju and Ice Cream, revealing family breakup, job insecurity, and alcoholism, modulates into tearful frustration. The comic suicide attempts of A Matter of Interpretation are balanced by the melancholy prospect of aborted artistic careers and disrupted love affairs. When Jeon-shin sees the detective again in the final stretches of the film, he ignores her; their momentary friendship is over.

Romance Joe offers something grimmer than Hong’s comedy of bad manners. At the core of the story action is the sad tale of Cho-hee, scorned by her classmates, oppressed by her parents, and desperate to flee town. After her wrist-cutting episode, she and the young Joe flee to Seoul for a night, but in confusion he abandons her. She too returns home, only to leave again when she becomes pregnant (by whom?). She becomes a Seoul prostitute. Through a chance meeting Cho-hee finds that her life has become a source for Joe’s student film. She seems cheered by this, but we never see her fully grown. Joe must confront not only his feeble career but his long-ago failure to honor his promise to Cho-hee: “I’ll always protect you.” Like her and Rei-ji he bears the stigmata of a botched suicide.

This somber tone has wholly taken over Lee’s recent A Tiger in Winter. Thoroughly linear in construction, with no embedded tales, it probes an unhappy couple: a failed novelist living on the margins and his alcoholic former girlfriend, who’s found success but now suffers writer’s block. It’s a chronicle of yuppie pathos and pain in chilly urban landscapes, where we find anomie and temps morts and, again, suicide.

“In Romance Joe,” Lee remarks, “I was focused on someone that was committing suicide because they didn’t have a story any more, and in A Matter of Interpretation she didn’t have an audience any more.” In A Tiger in Winter, the characters have run out of stories and audiences. Clearly, for Hong, your prospects are bleak when you can’t summon up the redeeming power of imagination.

Thanks to Lee Kwangkuk and Tony Rayns for help in preparing this entry. Romance Joe was once available on South Korean DVD, but apparently no longer. The only Lee Kwangkuk film currently on video, as far as I know, is Soju and Ice Cream, part of an omnibus film for the Korean Human Rights Commission. Lee’s oeuvre is a real opportunity for an ambitious streaming service.

My quotation from Lee comes from an easternkicks interview. Our entries on Hong Sangsoo are here. One of them is a 2012 first impression of Romance Joe. On embedded stories in general, there’s this.

Hard to Say (2012).