Thrill me!

Saturday | June 3, 2017 open printable version

open printable version

Based on a True Story (Polanski, 2017).

DB here:

Three examples, journalists say, and you’ve got a trend. Well, I have more than three, and probably the trend has been evident to you for some time. Still, I want to analyze it a bit more than I’ve seen done elsewhere.

That trend is the high-end thriller movie. This genre, or mega-genre, seems to have been all over Cannes this year.

A great many deals were announced for thrillers starting, shooting, or completed. Coming up is Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, “centering on members of a church who are troubled by the loss of their loved ones.” There’s Sarah Daggar-Nickson’s A Vigilante, with Olivia Wilde as a woman avenging victims of domestic abuse. There’s Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World, about the kidnapping of J. Paul Getty III. There’s Lars von Trier’s serial-killer exercise The House that Jack Built. There’s as well 24 Hours to Live, Escape from Praetoria, Close, In Love and Hate, and Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, featuring Zac Efron as Ted Bundy. Claire Denis, who has made two thrillers, is planning another. Not of all these may see completion, but there’s a trend here.

Then there were the movies actually screened: Based on a True Story (Assayas/ Polanski), Good Time (the Safdie brothers), L’Amant Double (Ozon), The Killing of a Sacred Deer (Lanthimos), The Merciless (Byun), You Were Never Really Here (Ramsay), and Wind River (Sheridan), among others. There was an alien-invasion thriller (Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Before We Vanish), a political thriller (The Summit), and even an “agricultural thriller” (Bloody Milk). The creative writing class assembled in Cantet’s The Workshop is evidently defined through diversity debates, but what is the group collectively writing? A thriller.

Thrillers seldom come up high in any year’s global box-office grosses. Yet they’re a central part of international film culture and the business it’s attached to. Few other genres are as pervasive and prestigious. What’s going on here?

A prestigious mega-genre

Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958).

Thriller has been an ambiguous term throughout the twentieth century. For British readers and writers around World War I, the label covered both detective stories and stories of action and adventure, usually centered on spies and criminal masterminds.

By the mid-1930s the term became even more expansive, coming to include as well stories of crime or impending menace centered on home life (the “domestic thriller”) or a maladjusted loner (the “psychological thriller”). The prototypes were the British novel Before the Fact (1932) and the play Gas Light (aka Gaslight and Angel Street, 1938).

While the detective story organizes its plot around an investigation, and aims to whet the reader’s curiosity about a solution to the puzzle, in the domestic or psychological thriller, suspense outranks curiosity. We’re no longer wondering whodunit; often, we know. We ask: Who will escape, and how will the menace be stopped? Accordingly, unlike the detective story or the tale of the lone adventurer, the thriller might put us in the mind of the miscreant or the potential victim.

In the 1940s, the prototypical film thrillers were directed by Hitchcock. I’ve argued elsewhere that he mapped out several possibilities with Foreign Correspondent and Saboteur (spy thrillers) Rebecca and Suspicion (domestic suspense), and Shadow of a Doubt (domestic suspense plus psychological probing). Today, I suppose core-candidates of this strain of thrillers, on both page and screen, would be The Ghost Writer, Gone Girl, and The Girl on the Train.

In the 1940s, as psychological and domestic thrillers became more common, critics and practitioners started to distinguish detective stories from thrillers. In thinking about suspense, people noticed that the distinctive emotional responses depend on different ranges of knowledge about the narrative factors at play. With the classic detective story, Holmesian or hard-boiled, we’re limited to what the detective and sidekicks know. By contrast, a classic thriller may limit us to the threatened characters or to the perpetrator. If a thriller plot does emphasize the investigation we’re likely to get an alternating attachment to cop and crook, as in M, Silence of the Lambs, and Heat.

Today, I think, most people have reverted to a catchall conception of the thriller, including detective stories in the mix. That’s partly because pure detective plotting, fictional or factual, remains surprisingly popular in books, TV, and podcasts like S-Town. The police procedural, fitted out with cops who have their own problems, is virtually the default for many mysteries. So when Cannes coverage refers to thrillers, investigation tales like Campion’s Top of the Lake are included.

In addition, “impure” detective plotting can exploit thriller values. Films primarily focused on an investigation, but emphasizing suspense and danger, can achieve the ominous tension of thrillers, as Se7en and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo do. More generally, any film involving crime, such as a heist or a political cover-up, could, if it’s structured for suspense and plot twists, be counted as part of the genre.

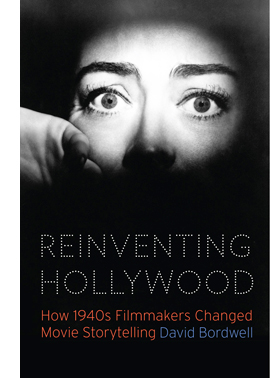

Yet tales of police detection aren’t currently very central to film, I think. Their role, Jeff Smith suggests, has been somewhat filled by the reporter-as-detective, in Spotlight, Kill the Messenger, and others. Straight-up suspense plots are even more common, as in the classic victim-in-danger plots of The Shallows, Don’t Breathe, and Get Out. Tales of psychological and domestic suspense coalesced as a major trend in Hollywood during the 1940s. It became so important that I devoted a chapter to it in my upcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. (You can get an earlier version of that argument here.)

By referring to “high-tone” thrillers, I simply want to indicate that major directors, writers, and stars have long worked in this broad genre. In the old days we had Lang, Preminger, Siodmak, Minnelli, Cukor, John Sturges, Delmer Daves, Cavalcanti, and many others. Today, as then, there are plenty of mid-range or low-end thrillers (though not as many as there are horror films), but a great many prestigious filmmakers have tried their hand: Soderbergh (Haywire, Side Effects), Scorsese (Cape Fear, Shutter Island), Ridley Scott (Hannibal), Tony Scott (Enemy of the State, Déja vu), Coppola (The Conversation), Bigelow (Blue Steel, Strange Days), Singer (The Usual Suspects), the Coen brothers (Blood Simple, No Country for Old Men et al.), Shyamalan (The Sixth Sense, Split), Nolan (Memento et al.), Lee (Son of Sam, Clockers, Inside Man), Spielberg (Jaws, Minority Report), Lumet (Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead), Cronenberg (A History of Violence, Eastern Promises), Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown), Kubrick (Eyes Wide Shut), and even Woody Allen (Match Point, Crimes and Misdemeanors). Brian De Palma and David Fincher work almost exclusively in the genre.

And that list is just American. You can add Almodóvar, Assayas, Besson, Denis, Polanski, Figgis, Frears, Mendes, Refn, Villeneuve, Cuarón, Haneke, Cantet, Tarr, Gareth Jones, and a host of Asians like Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho, and Johnnie To. I can’t think of another genre that has attracted more excellent directors. The more high-end talents who tackle the genre, the more attractive it becomes to other filmmakers.

Signing on to a tradition

Creepy (Kurosawa, 2016).

If you’re a writer or a director, and you’re not making a superhero film or a franchise entry, you really have only a few choices nowadays: drama, comedy, thriller. The thriller is a tempting option on several grounds.

For one thing, there’s what Patrick Anderson’s book title announces: The Triumph of the Thriller. Anderson’s book is problematic in some of its historical claims, but there’s no denying the great presence of crime, mystery, and suspense fiction on bestseller lists since the 1970s. Anderson points out that the fat bestsellers of the 1950s, the Michener and Alan Drury sagas, were replaced by bulky crime novels like Gorky Park and Red Dragon. As I write this, nine of the top fifteen books on the Times hardcover-fiction list are either detective stories or suspense stories. A thriller movie has a decent chance to be popular.

This process really started in the Forties. Then there emerged bestselling works laying out the options still dominant today. Erle Stanley Gardner provided the legal mystery before Grisham; Ellery Queen gave us the classic puzzle; Mickey Spillane provided hard-boiled investigation; and Mary Roberts Rinehart, Mignon G. Eberhart, and Daphne du Maurier ruled over the woman-in-peril thriller. Alongside them, there flourished psychological and domestic thrillers—not as hugely popular but strong and critically favored. Much suspense writing was by women, notably Dorothy B. Hughes, Margaret Millar, and Patricia Highsmith, but Cornell Woolrich and John Franklin Bardin contributed too.

I’d argue that mystery-mongering won further prestige in the Forties thanks to Hollywood films. Detective movies gained respectability with The Maltese Falcon, Laura, Crossfire, and other films. Well-made items like Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, The Ministry of Fear, The Stranger, The Spiral Staircase, The Window, The Reckless Moment, The Asphalt Jungle, and the work of Hitchcock showed still wider possibilities. Many of these films helped make people think better of the literary genre too. Since then, the suspense thriller has never left Hollywood, with outstanding examples being Hitchcock’s 1950s-1970s films, as well as The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seconds (1966), Wait Until Dark (1967), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Parallax View (1974), Chinatown (1974), and Three Days of the Condor (1975), and onward.

Which is to say there’s an impressive tradition. That’s a second factor pushing current directors to thrillers. It does no harm to have your film compared to the biggest name of all. Google the phrase “this Hitchcockian thriller” and you’ll get over three thousand results. Science fiction and fantasy don’t yet, I think, have quite this level of prestige, though those genres’ premises can be deployed in thriller plotting, as in Source Code, Inception, and Ex Machina.

Since psychological thrillers in particular depend on intricate plotting and moderately complex characters, those elements can infuse the project with a sense of classical gravitas. Side Effects allowed Soderbergh to display a crisp economy that had been kept out of both gonzo projects like Schizopolis and slicker ones like Erin Brockovich.

Ben Hecht noted that mystery stories are ingenious because they have to be. You get points for cleverness in a way other genres don’t permit. Because the thriller is all about misdirection, the filmmaker can explore unusual stratagems of narration that might be out of keeping in other genres. In the Forties, mystery-driven plots encouraged writers to try replay flashbacks that clarified obscure situations. Mildred Pierce is probably the most elaborate example. Up to the present, a thriller lets filmmakers test their skill handling twists and reveals. Since most such films are a kind of game with the viewer, the audience becomes aware of the filmmakers’ skill to an unusual degree.

Thrillers also tend to be stylistic exercises to a greater extent than other genres do. You can display restraint, as Kurosawa Kiyoshi does with his fastidious long-take long shots, or you can go wild., as with De Palma’s split-screens and diopter compositions. Hitchcock was, again, a model with his high-impact montage sequences and florid moments like the retreating shot down the staircase during one murder in Frenzy.

Would any other genre tolerate the showoffish track through a coffeepot’s handle that Fincher throws in our face in Panic Room? It would be distracting in a drama and wouldn’t be goofy enough for a comedy.

Yet in a thriller, the shot not only goes Hitchcock one better but becomes a flamboyant riff in a movie about punishing the rich with a dose of forced confinement. More recently, the German one-take film Victoria exemplifies the look-ma-no-hands treatment of thriller conventions. Would that movie be as buzzworthy if it had been shot and cut in the orthodox way?

Fairly cheap thrills

Non-Stop (Collet-Serra, 2014). Production budget: $50 million. Worldwide gross: $222 million.

The triumph of the movie thriller benefits from an enormous amount of good source material. The Europeans have long recognized the enduring appeal of English and American novels; recall that Visconti turned a James M. Cain novel into Ossessione. After the 40s rise of the thriller, Highsmith became a particular favorite (Clément, Chabrol, Wenders). Ruth Rendell has been mined too, by Chabrol (two times), Ozon, Almodóvar, and Claude Miller. Chabrol, who grew up reading série noire novels, adapted 40s works by Ellery Queen and Charlotte Armstrong, as well as books by Ed McBain and Stanley Ellin. Truffaut tried Woolrich twice and Charles Williams once. Costa-Gavras offered his version of Westlake’s The Ax, while Tavernier and Corneau picked up Jim Thompson. At Cannes, Ozon’s L’Amant double derives from a Joyce Carol Oates thriller the author calls “a prose movie.”

Of course the French have looked closer to home as well, with many versions of Simenon novels by Renoir, Duvivier, Carné, Chabrol (inevitably), Leconte, and others. The trend continues with this year’s Assayas/Polanski adaptation of the French psychological thriller Based on a True Story.

In all such cases, writers and directors get a twofer: a well-crafted plot from a master or mistress of the genre, and praise for having the good taste to disseminate the downmarket genre most favored by intellectuals.

Another advantage of the thriller is economy. There are big-budget thrillers like Inception, Spectre, and the Mission: Impossible franchise. But the thriller can also flourish in the realm of the American mid-budget picture. Recently The Accountant, The Girl on the Train, and The Maze Runner all had budgets under $50 million. Putting aside marketing costs, which are seldom divulged, consider estimated production costs versus worldwide grosses of these top-20 thrillers of the last seven years. The figures come from Box Office Mojo.

Taken 2 $45 million $376 million

Gone Girl $61 million $369 million

Now You See Me $75 million $351 million

Lucy $40 million $463 million

Kingsman: The Secret Service $81 million $414 million

Then there are the low-budget bonanzas.

The Shallows $17 million $119 million

Don’t Breathe $9.9 million $157 million

The Purge: Election Year $10 million $118 million

Split $9 million $276 million

Get Out $4.5 million $241 million

Of course budgets of foreign thrillers are more constrained, and I don’t have figures for typical examples. Still, overseas filmmakers tackling the genre have an advantage over their peers in other genres. Thrillers are exportable to the lucrative American market, twice over.

First, a thriller can be an art-house breakout. Volver, The Lives of Others, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2009) all scored over $10 million at the US box office, a very high number for a foreign-language film. Asian titles that get into the market have done reasonably well, and enjoy long lives on video and streaming. The Handmaiden and Train to Busan, both from South Korea, doubled the theatrical take of non-thrillers Toni Erdmann and Julieta, as well as that of American indies like Certain Women and The Hollers. Elsewhere, thrillers comprised two of the three big arthouse hits in the UK during the first four months of this year: The Handmaiden, a con-artist movie in its essence, and Elle, a lacquered woman-in-peril shocker.

Second, a solid import can be remade with prominent actors, as Wages of Fear and The Secret in Their Eyes were. Probably the most high-profile recent example was The Departed, a redo of Hong Kong’s Infernal Affairs. Sometimes the director of the original is allowed to shoot the remake, as happened with The Vanishing, Loft, and Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Even if the remake doesn’t get produced, just the purchase of remake rights is a big plus. I remember one European writer-director telling me that he earned more from selling the remake rights to his breakout film than he did from the original. He was also offered to direct the remake, but he declined, explaining: “If someone else does it, and it’s good, that’s good for the original. If it’s bad, people will praise the original as better.” And by making a specialty hit, the screenwriter or director gets on the Hollywood radar. If you can direct an effective thriller, American opportunities can open up, as Asian directors have discovered.

Thrillers attract performers. Actors want to do offbeat things, and between their big-paycheck parts they may find the conflicted, often duplicitous characters of psychological thrillers challenging roles. For Side Effects Soderbergh rounded up name performers Jude Law, Rooney Mara, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Channing Tatum. The Coens are skillful at working with stars like Brad Pitt (Burn after Reading). The rise of the thriller has given actors good Academy Award chances too. Here are some I noticed:

Jane Fonda (Klute), Jodie Foster (Silence of the Lambs), Frances McDormand (Fargo), Natalie Portman (Black Swan), Brie Larson (Room), Anjelica Huston (Prizzi’s Honor), Kim Basinger (L.A. Confidential), Rachel Weisz (The Constant Gardener), Jeremy Irons (Reversal of Fortune), Denzel Washington (Training Day), Sean Penn (Mystic River), Sean Connery (The Untouchables), Tommy Lee Jones (The Fugitive), Kevin Spacey (The Usual Suspects), Benicio Del Toro (Traffic), Tim Robbins (Mystic River), Javier Bardem (No Country for Old Men), Mark Rylance (Bridge of Spies).

Finally, there’s deniability. Because of the genre’s literary prestige, because of the tony talent behind and before the camera, and because of the genre’s ability to cross cultures, the thriller can be….more than a thriller. Just as critics hail every good mystery or spy novel as not just a thriller but literature, so we cinephiles have no problem considering Hitchcock films and Coen films and their ilk as potential masterpieces. On the most influential list of the fifty best films we find The Godfather and Godfather II, Mulholland Dr., Taxi Driver, and Psycho. At the very top is Vertigo, not only a superb thriller but purportedly the greatest film ever made.

I worried that perhaps this whole argument was an exercise in confirmation bias–finding what favors your hunch and ignoring counterexamples. Looking through lists of top releases, I was obliged to recognize that thrillers aren’t as highly rewarded in film culture as serious dramas (Manchester by the Sea, Moonlight, Paterson, Jackie, The Fits). But I also kept finding recent films I’d forgotten to mention (Hell or High Water, The Green Room) or didn’t know of (Karyn Kusama’s The Invitation, Mike Flanigan’s Hush). They supported the minimal intuition that thrillers play an important role in both independent and mainstream moviemaking.

And not just on the fringes or the second tier. Perhaps because film is such an accessible art, all movies are fair game for the canon. As a fan of thrillers in all variants, from genteel cozies and had-I-but-known tales to hard-boiled noir and warped psychodramas, I’m glad that we cinephiles have no problem ranking members of this mega-genre up there with the official classics of Bergman, Fellini, and Antonioni (who built three movies around thriller premises). Of course other genres yield outstanding films as well. But we should be proud that cinema can offer works that aren’t merely “good of their kind” but good of any kind. For that reason alone, ambitious filmmakers are likely to persist in thrill-seeking.

Thanks to Kristin, Jeff Smith, and David Koepp for comments that helped me in this entry. Ben Hecht’s remark comes from Philip K. Scheuer, “A Town Called Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times (30 June 1940), C3.

You can get a fair sense of what the Brits thought a thriller was from a book by Basil Hogarth (great name), Writing Thrillers for Profit: A Practical Guide (London: Black, 1936). A very good survey of the mega-genre is Martin Rubin’s Thrillers (Cambridge University Press, 1999). David Koepp, screenwriter of Panic Room, has thoughts on the thriller film elsewhere on this blog.

Having just finished Delphine de Vigan’s Based on a True Story, I can see what attracted Assayas and Polanski. The film (which I haven’t yet seen) could be a nifty intersection of thriller conventions and the art-cinema aesthetic. As a gynocentric suspenser, though, the book doesn’t seem to me up to, say, Laura Lippman’s Life Sentences, a more densely constructed tale of a memoirist’s mind. And de Vigan’s central gimmick goes back quite a ways; to mention its predecessors would constitute a spoiler. For more on women’s suspense fiction, see “Deadlier than the male (novelist).” For more on Truffaut’s debt to the Hitchcock thriller, try this.

The Workshop (Cantet, 2017).