Archive for the 'Film history' Category

TRAPPED: Low-budget flash is good for you

Trapped (1949).

DB here:

Films of the 1940s sported many vivid titles, from Double Indemnity to The Best Years of Our Lives. But a lot of them really didn’t try too hard. We have Dangerous Lady, Shock!, Men on Her Mind, Bad Sister, Lust for Gold, and Criminal Lawyer. Even worse are Crack-Up, Manhandled, Temptation, Nightmare, Impact, Homicide, and even, the purest of all, Conflict.

Fortunately the lack of imagination didn’t always extend to story and style. In the Forties, even minor genre films could get flashy, displaying weird plot turns and wild visuals. Nowhere was this truer than in films centered on crime and mystery.

Granted, this material always encouraged some unorthodox techniques. (We can find examples going back to the 1910s.) Still, whatever you think “noir” was, it encouraged filmmakers to push even further. A 1930s B would have been unlikely to be as bodacious as a moment in Detour (1945), when a single forward tracking shot lets the lights lower and makes a coffee mug as big as a bucket.

For such reasons we should be grateful to the Film Noir Foundation, to the UCLA Film and Television Archive, and to Flicker Alley for bringing us Trapped (1949). The generic title had been used by four earlier films, and it could refer to several of the characters, but the results onscreen are far less banal. I hadn’t known the film, but if I had I might have wormed it into Reinventing Hollywood for the wrinkles it adds to the government-agent semidocumentary.

Crime high and low

Product placement for studio Hollywood’s favorite brand.

Trapped was produced by Brian Foy and distributed by Eagle-Lion, the same company that gave us the bizarre Repeat Performance (1947) and some of Anthony Mann’s best Forties items. According to the disc’s informative, pleasantly sensationalistic booklet, the project was hitching a ride on the success of Mann’s T-Men (1947). The Treasury Department approved of the project, and the film includes lots of fascinating shot-on-the-street scenes of LA. Although director Richard Fleischer doesn’t mention the film in his autobiography Just Tell Me When to Cry, he should have been proud of it. (He does mention Clay Pigeon, though, a film I talk about in another entry.)

A stern voice-over launches a quasi-documentary montage of the rise of counterfeiting after the war. Tris Stewart is serving time, but bills with his signature have resurfaced. Agreeing to act as a mole, he’s allowed to bust out of prison, but soon he eludes his federal handlers. He hooks up with his old girlfriend Meg and discovers that his precious plates are in the hands of an old adversary, Jack Sylvester. The bulk of the plot follows Tris’s effort to fund a last big job before fleeing to Mexico with Meg. In the course of it, he joins up with John Downey, a down-at-heel gambler.

The viewpoint shifts freely among the characters, so we always know more than any one of them. We know that the Feds have wired Meg’s apartment for sound. We learn that Downey is actually a government agent working to trap both Tris and Sylvester. And we see Tris eventually learn Downey’s identity decide to double-cross him.

Meg has a pivotal role in precipitating the climax. She’s naturally punished for hanging out with the wrong guy. I could apply my quatrain on Hollywood Stories:

The plot only works

If the men are all jerks;

But at the end of the game,

It’s the woman to blame.

Lloyd Bridges plays the sort of natty, grinning sociopath whom he would make memorable in The Sound of Fury (1951, aka Come and Get Me!). The dry John Hoyt is needed to carry the last stretch of the film, which he does with sangfroid, but Tris exits the plot a little sooner than we’d probably like. Eddie Muller suggests that Tris was intended to be in the climax but production contingencies put Sylvester into it.

To compensate, the wrapup becomes one of those dazzling Forties climaxes played out on an overwhelming location. Like the gasworks in This Gun for Hire (1942), the field of storage tanks in White Heat (1948), and the Fort Point Compound of The Man Who Cheated Himself (1950), here a vast trolley-car barn provides spectacular compositions and lighting effects.

Noir really did bring out the best in creative personnel. Guy Roe, a camera operator and assistant since the 1930s, had moved up to Director of Photography for Sirk (A Scandal in Paris, 1946), Mann (Railroaded!, 1947), another punchy Eagle-Lion effort, and Boetticher (Behind Locked Doors, 1948), so he was ready to give this effort flamboyant touches, some overt and some more subtle.

We tend to think of crane shots as aiming for surveying vistas outdoors. By the 1940s, many interiors were shot with smaller cranes or vertically mobile dollies that permitted alternation between tight high- and low-angle setups.

Roe would go on to shoot more films now considered strong noir entries: Armored Car Robbery (1950, another flat title) and The Sound of Fury. This last, as I suggest here, promotes the same tight high angles we find in Trapped, with perhaps more fine-grained results.

Fleischer didn’t have the blasting visual force of Mann, and Roe didn’t have the baroque imagination of Mann’s DP John Alton. Still, Trapped does deliver a handsome array of long-take deep-focus shots. These attest to the influence of Citizen Kane (1941) as a prototype for dynamic compositions, often exploiting ceilings on sets.

Such angles led directors to think more about using the vertical stretch of the screen, again aided by a camera pitched slightly high or low.

One turning point, Tris’s discovery of the Feds’ bug in Meg’s lamp, is designed to exploit a slightly tipped-down framing, with the splash of light accentuating the moment of revelation.

American crime films weren’t unique in their pictorial bravado. Watching Trapped drove me back to Noose, a 1948 British film by Edmund T. Gréville. A semi-comic tale of London gangsters, it abounds in florid depth compositions. (See below.) Just more proof that the 1940s saw a new exploration of bold narrative and stylistic initiatives in sound cinema around the world. And those weren’t confined to the big productions. Once new image schemas were available, artisans at all levels could make piquant uses of them.

The Flicker Alley release is nicely filled out with informative supplements contributed by Alan K. Rode, Eddie Muller, Donna Lethal, and Julie Kirgo. Mark Fleischer offers some touching reminiscences of his father’s life and creative ambitions. Thanks as well to Jeffrey Masino and Josh Fu of Flicker Alley. And we owe a debt to the collector who deposited a 35mm acetate print at Harvard, whence it comes to us.

For more on 1940s cinematography, see our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 and entries in the 1940s Hollywood categories here. Patrick Keating’s central chapters in The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood supply a lot of information about the growing use of cranes and maneuverable dollies for intimate dramatic scenes.

Noose (1948). A Brit noir ripe for Blu-ray release.

Torino images, preparing for the festival

DB here:

If you’re not a hardcore horror fan, you may not recognize the image that adorns this year’s Torino Film Festival publicity, but I bet you’re fascinated by it anyway. Barbara Steele, the diva supreme of 1960s scary cinema, is a fitting emblem for this year’s broad and deep retrospective of the horror genre. From The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971), thirty-six films are on display, often in 35mm prints. Emanuela Martin, the curator of the series and director of the festival, has created a book devoted to her program. And the festival has welcomed the iconic Ms Steele as a guest.

In-depth commitment to a retrospective is typical of this enterprising festival. Kristin and I had been hearing about it for years from our friend, Wisconsin Cinematheque honcho Jim Healy, who has long been a contributing programmer here. Previous editions focused on “Amerikana,” De Palma, dystopian SF, Powell & Pressburger, and Miike Takashi.

Still, at Torino as elsewhere, the emphasis falls on new work. Dozens of films are screened both in and out of competition. Kristin and I are still assimilating items to report on in forthcoming blog entries. But we’ve already sampled the charms of this city, not least its monumental temple to film, its Museo del Cinema. But first, another municipal tribute to picture-making.

Pictures, some puzzling

The Galleria Sabauda in the Palazzo Reale teems with masterpieces, mostly from the collection of the Savoy dynasty. The non-masterpieces are worth studying too, and some, even in their weirdness, can prompt thinking about cinema (of course).

For instance, there’s this Antonio Tempesta painting, Torneo nella Piazza del Castello (1620), showing an aristocratic wedding procession in a Turin plaza. I liked its steep perspective with the commanding figure of the warrior in the foreground. Close observation, which the Sabauda permits, reveals tiny figures on the rooftop at the left.

Evidently the paining yields a lot of information about architectural projects of the day. All I could think of is what a swell film shot it would be.

Instead of Testa’s high angle, which yields a centered and stable composition, consider Varallo’s punchier Saints Peter and Mark, from the same period (1626).

The low viewing angle on the two saints makes their muscular gestures dominate the middle of the format. That axis calls to their incredibly distended fingers caught in the act of dictating and writing. The angle also lets us enjoy the casually crossed leg of Mark and his tense, splayed toes, which seem to poke against the picture surface.

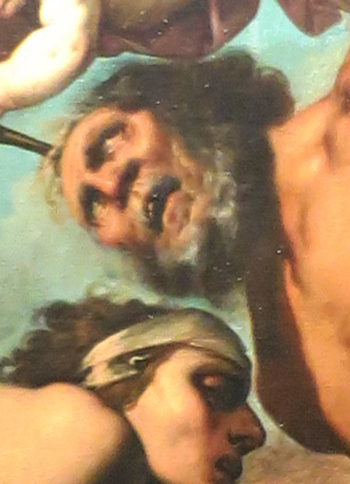

Angles again: This unidentified painting of the savage martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (ca. 1635) grabbed me because of its even steeper low angle.

Apart from the Caravaggio spotlight effect (overexposed in my shot; I can’t find an image online), it reminded me of one of my fussier concerns.

Cinema lets us separate planes because of constant overlap, one layer of space moving against another. Painting can’t let us detect contours from movement, so when painters want to shove figures together they need to mark off overlapping planes in other ways, such as color or edge lighting.

Alternatively, painters can pack figures but leave little holes that let bits of background show through but still give a sense of movement. In the St. Bartholomew painting, the contours that specify the figures nearly graze each other.

I especially like the way that the brow and nose of Bartholomew’s tormentor fit like a puzzle-piece into the twist of the saint’s shoulder. Good old figure/ground technique, but pushed to a kind of minimal limit.

When these little gaps aren’t left, and only overlap and colors pick out planes, you can get some striking effects. The most mind-bending thing of this sort I saw at the Galleria was this Resurrection, perhaps by Antonio Campi, from around 1660. At the bottom of the picture a soldier is prodding a sleeping guard beside the sepulcher.

The soldier on the right is one strange creature. You can work it out that he’s wearing a thick, ribbed yellow doublet with a beast’s head attached at the shoulder. But the effect of the overlapping planes and the compositional contours is of a duck/rabbit shift, as if the beast is bent over the soldier.

The effect is enhanced by the sinewy leg of the soldier behind, which seems at first glance to be the right arm of the stooped beast. The absence of spacing between the foot and the spear helps the effect of a limb continuing the arc of the bent back.

Enough of amateur art appreciation. Turin houses another magnificent repository of artifacts, this one dedicated to our own obsessions.

Film history on a grand scale

Mole Antonelliana, Turin.

The Museo Nazionale di Cinema is housed in the Mole Antonelliana, a fascinating elongated building that towers over the city. An elevator shoots people up to a fancy spire with a panoramic view.

Pictures can’t do justice to the Museo inside. You enter through the biggest and most engaging collection of pre-cinema materials I’ve ever seen. Nearly every gadget, from the magic lantern to Edison’s Kinetoscope, is offered for you to tinker with. (An interactive sampling is here.) Once you’ve seen the entire archaeology of film, you step into a gigantic hall with a spiral ramp leading to level after level.

Nearly the first thing you meet is the god Moloch from Cabiria (1914), a film made when Turin was a major national production center. Not quite as big as in the film, he was enough to intimidate me.

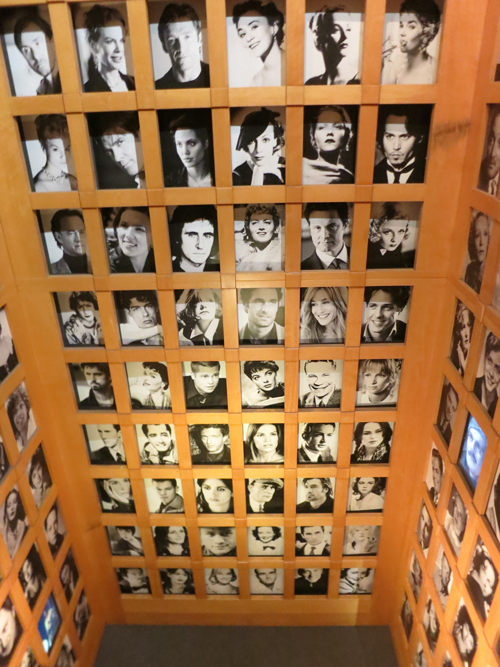

Various floors take you to theme areas. There’s one on film production with some classic cameras, another displaying a vast gallery of posters, and several devoted to changing exhibitions. (The current one was on facial expression in cinema, hooking to a big show of Lombroso’s physiognomic studies.) You can see a script page from Psycho or Citizen Kane, and stare in awe at a two-story display of star portraits.

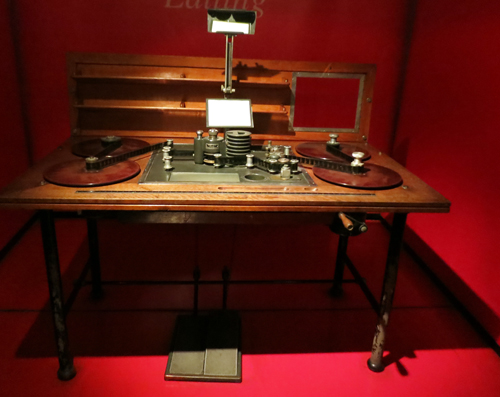

Kristin and I visited a shrine to the beautiful Prevost editing table. (This is a 1930s one.)

There’s so much here that more than one visit is probably demanded. In all, the Museo makes a splendid anchoring point for the film festival. We’ll tell you more about that in upcoming entries.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page.

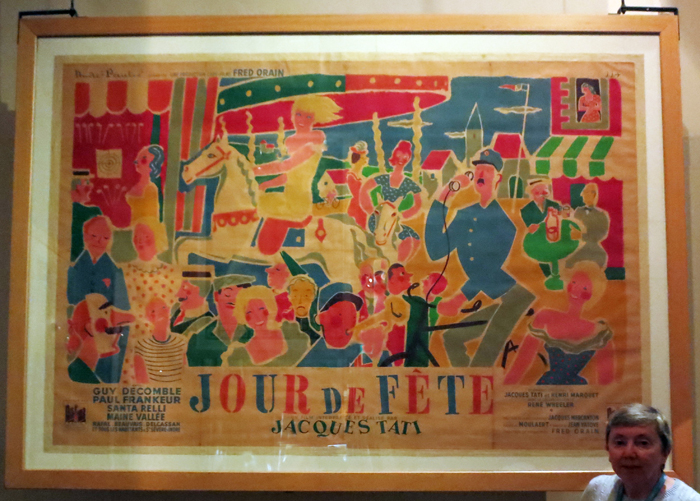

Kristin and a big poster for Tati’s Jour de fête.

Captain Cinephilia: Scorsese strikes back

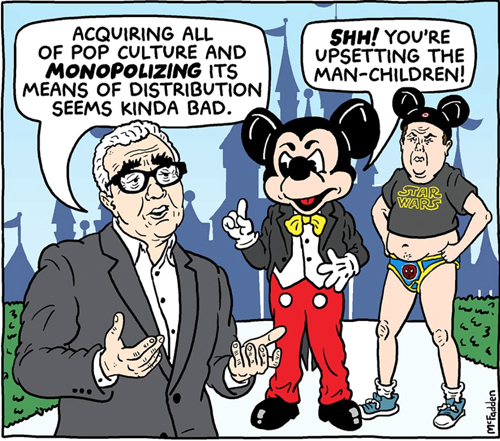

Brian McFadden, No One Is Safe: Martin Scorsese Roasts Your Fandom.”

DB here:

It started with a brief, almost offhand remark.

“I don’t see them,” [Scorsese] says of the MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe]. “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well-made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

When I learned about this interview (Empire, November issue), I took it as simply a roundabout statement of personal taste. Scorsese doesn’t find Marvel movies, and perhaps other comic-book sagas of superheroes, to his taste. He gave them a fair shot, but he now no longer sees them. He considers them visceral stimulation, like carnivals or theme parks. They’re not cinema, if you consider cinema as emotional expression of psychological conflicts.

In the massive responses to Scorsese, people pointed out that viewers often respond emotionally to superhero films. They root for certain characters, they’re amused or thrilled by certain situations, and many claim to be deeply moved by the heroes and villains (Loki, even Thanos). In fact, it’s exactly the “emotional, psychological experiences” embedded in the Marvel and DC plots that some fans say distinguish them from crude comic-book movies that went before. Much the same could be said of the Bond films, which became more humanized with Quantum of Solace, though intermittently before.

As for the claim that the superhero films “aren’t cinema,” I wasn’t really upset. Over the decades we’ve heard that 1910s films “aren’t cinema” (too theatrical), or that adaptations of novels or plays “aren’t cinema” (too literary or stagebound), or that narrative films “aren’t cinema” (usually proposed by avant-gardists). When the claim relies on a notion of some cinematic essence (editing, or pure visual form) that’s missing from this or that movie, you might be able to have a productive conversation. But if “This isn’t cinema” comes down to “I don’t like films like this,” we’re back to personal taste.

On other occasions Scorsese went on to say a lot more. The ultimate result was a 7 November article in the New York Times. I think we should take this as his most thoroughgoing effort to explain his thinking. We can supplement that with some remarks he made in interviews and Q & A sessions.

Herewith my attempts to figure out Scorsese’s argument. Trying to sort this out might teach us some important things about film now.

Scorsese in defense of Cinema

Scorsese’s Times article, “I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain,” begins by disclaiming any hatred for Marvel movies as such. “The fact that the films themselves don’t interest me is a matter of personal taste and temperament.”

But everyone’s taste gets shaped by their moviegoing experience, and in his youth Scorsese was attracted to films from America and Europe. These yielded “revelation—aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual revelation.” The films were, he felt, about characters who were complex, sometimes contradictory in their minds and behavior.

Moreover, these films showed that cinema was an art form, one existing in both commercial and more experimental spheres. Hollywood studio output (Ford Westerns, Hitchcock thrillers), European imports (Bergman, Godard), and avant-garde work (Scorpio Rising)—all these showed that cinema had powers equal to those of music, dance, and literature. These films were technically accomplished, sometimes virtuoso, but at their hearts were intense, complex emotional appeals that assured that they would be watched for decades later.

Today the Marvel pictures, often skillfully made, lack “revelation, mystery, or genuine emotional danger.” They are repetitive, adhering to a basic formula, “defined as variations on a finite number of themes.” By contrast, the films of Paul Thomas Anderson, Claire Denis, Wes Anderson, and other directors offer new and unpredictable experiences, and they expand the possibilities of the art form. “The unifying vision of an individual artist” is essential to cinema.

It’s exactly the exploratory filmmakers who are being stifled by the Marvel releases, and indeed all the franchises. These more personal films aren’t just constrained by lower budgets; they can’t get much exposure on theatre screens either. “Around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen.” Most filmmakers design their films for that scale and that communal experience, but the blockbuster films are pushing smaller pictures into streaming outlets.

The franchise mentality is a corporate one. The products are “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” As often happens, the business constrains the art. But you might say, what about the old studio system? Wasn’t that as mercenary as today’s franchise juggernaut? No, because the studios set up a creative tension between the business end and the artistic end that yielded outstanding works, even masterpieces. Today’s franchise producers are indifferent to art and hold a view of film history that is both “dismissive and proprietary.”

As a result we have two domains: worldwide audiovisual entertainment vs. cinema. They overlap less and less, and it seems likely that the financial power of one will dominate and belittle the other.

I think that some of these arguments are plausible, while others deserve more probing.

Film art: Who’s the artist?

Andrew Sarris.

During the 1950s and 1960s, this general argument was promulgated by the so-called auteur critics around Cahiers du cinéma and was developed and promoted by Andrew Sarris in the US and Movie magazine in the UK. Scorsese was deeply influenced by these ideas. He was one of many cinephile directors-in-training who assumed that the best films bore the “unifying vision of the individual artist,” who was the auteur (author) of the film.

What was considered the “auteur theory” is too complicated to explore fully here. Minimally, it’s the idea that, all other things being equal, in many movies (often the best ones) the director can be considered the source of the film’s distinctive artistic qualities. The director may achieve this by exercising near-total control (e.g., Chaplin), or working with close collaborators (Powell and Pressburger, Donen and Kelly) or serving as a “filter” for the offerings of various contributors (probably most filmmakers).

This is the minimal case. The maximal one rests on the idea that once we make the director the central power, we then discover a “unifying vision.” At this level the distinctive features of form, style, and theme coalesce into a personal conception of human life. For Ford, that might include the value of traditions and the costs they demand of those subscribing to them. Hitchcock’s recurring concern, Robin Wood famously argued, is the realization that complacency, a trust in social order, is vulnerable to disruption.

The difference between the two versions I’m sketching isn’t hard and fast. Still, it often holds good. A friend, for instance, grants that Tony Scott is a distinctive filmmaker. “He just has nothing to say.” The idea that an auteur has something consistent and personal to “say,” deliberately or unconsciously, from film to film, is a hallmark of auteur criticism at its most ambitious. And the greatest auteurs, perhaps, show development in what they say across their careers. John Ford’s attitude toward the frontier can be said to change from The Iron Horse (1924) to Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

The minimalist auteur concept isn’t new. From the 1920s on, historians and critics often attributed creative authority to Griffith, Chaplin, De Mille, Hitchcock, and European and Soviet directors. And in most film industries, executives recognized that the director had the most responsibility for the film’s look and feel.

One revolutionary edge of auteur criticism was to discover auteurs nobody had noticed before–largely unknown filmmakers working alongside humbler folk. And the critics went further, suggesting that some of these filmmakers could be considered auteurs to the max.

Typically auteur critics didn’t examine the concrete context of production to determine who did what in particular cases. They inferred directorial expression by watching lots of films and tracing recurring strategies of style and theme. Sometimes they backed their conclusions up by interviews with–who else?–the director.

Minimal versions of the auteur idea are central to film culture now. Festivals promote directors, as do studio marketers. Movie lists in reference books and search sites give directors the pride of place. Variety and Hollywood Reporter reviews usually don’t name producers, cinematographers, and other contributors, but the director is always mentioned (and blamed or praised for the film). Academics and cinephile critics ascribe more maximalist “personal visions” to directors around the world, from David Lynch and Spike Lee to Wes Anderson to Wong Kar-wai and Jane Campion.

Auteur +genre = ?

Black Panther: Danai Gurira (Okoye), Ryan Coogler on the set.

Despite the prominence of some directors, they’re usually not what draws audiences. In most countries, the mass-market cinema is dominated by genres that are populated by well-known stars.

Sarris and others assumed that auteurs built upon the foundations provided by genre conventions and star images. Ford gave the Western a new force not only through his images and use of music but also by redefining the star personas of John Wayne and Henry Fonda. Hitchcock and Lang worked with and against the conventions of the thriller, while Ophuls gave the melodrama a melancholic elegance. Or so goes auteur gospel.

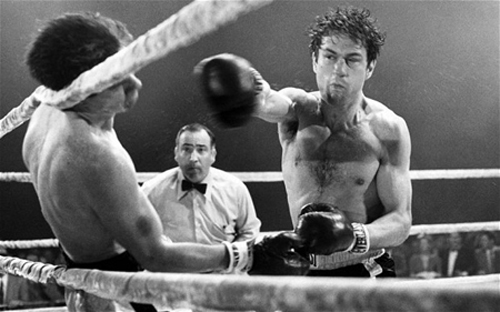

The 1970s New Hollywood auteurs embraced genre filmmaking as well. Bogdanovich, Coppola, Altman, Woody Allen, and others tested themselves in a variety of genres. Even Scorsese tried a “woman’s picture” (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), a musical (New York, New York), and a biopic (Raging Bull). They are only roughly parallel to today’s indie filmmaker who, after a breakthrough project at Sundance or SxSW, signs on to make a franchise picture.

As a generous and enthusiastic cinephile, Scorsese has long subscribed to a version of auteurism. Perhaps one source of his misgivings about Marvel and its counterparts is that he can’t detect auteurs in these movies. Does that mean they aren’t there? Is today’s studio cinema largely a genre cinema, minus the classic bonus of high-end auteur expression?

One of his comments has attracted little notice. Scorsese remarks of the theme-park picture:

The technique is very well done but there is only one Spielberg, there is only one Lucas, James Cameron. It’s a different thing now.

This implies that even the franchise genres could sustain some degree of what Sarris called “directorial personality.” Admirers of Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarock, James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, or Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman might agree. This has been one line of defense in the pushback to Scorsese’s comments.

Or maybe we should attribute whiffs of personal expression today to the producers (Bruckheimer, Kathleen Kennedy, Kevin Feige). Even in Hollywood’s heyday, we sense Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun as Selznick productions. Then there’s Walt Disney, surely a producer as auteur. I suspect that Scorsese finds these old films more inspiring than today’s behemoths.

Closing the drawbridge on Fort Multiplex

Avengers: Endgame (2019).

A genre can rise and fall in popularity. As the Western and the musical declined in the 1970s, horror and science-fiction gained traction as both programmers and A-list blockbusters. Add in the rise of fantasy, crystallized in the prestige accorded the Lord of the Rings installments. Oddly, as comic book sales declined, comic-book movies came to be a central contemporary genre. The superhero film proved a powerful blend of all these trends.

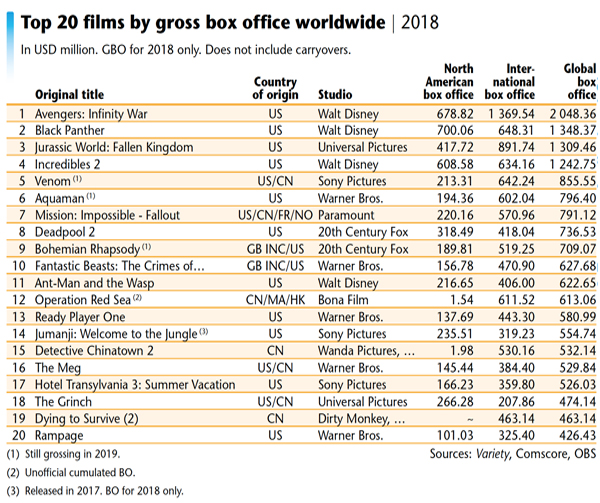

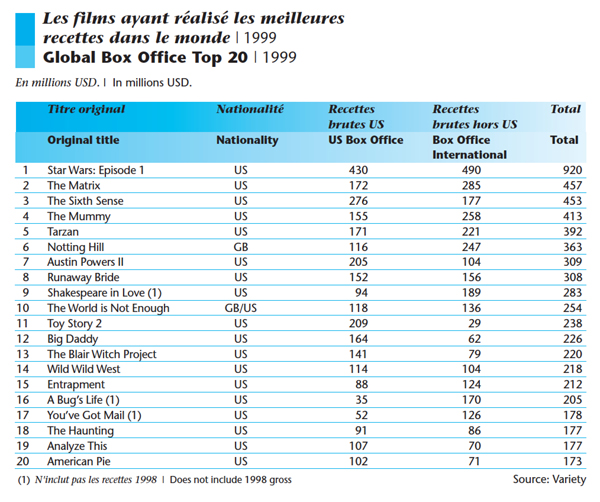

Today, the stifling presence of the fantasy/SF/comic-book franchises seems obvious. Look at two snapshots.

In 1999, the world’s top-grossing film was Star Wars: Episode 1. Among the twenty top hits were fantasy/SF blockbusters The Matrix and The Mummy, as well as a Bond entry. But there were also lower-budget horror films (The Sixth Sense, The Blair Witch Project). Most surprisingly, the top twenty include many comedies, mostly star-driven.

Now consider the 2018 situation.

Five of the global top ten were superhero films. The big winner was Avengers: Infinity War, which earned over two billion dollars globally–nearly twice as much as second-place Black Panther. Among the top ten are Venom, Aquaman, and Deadpool 2. Add The Incredibles as a sixth superhero film if you want. At 11 is Ant-Man and the Wasp. Most of the remaining titles are also franchise entries. There’s also the fantasy/SF blend Ready Player One, the monster movie Rampage, and the action thriller The Meg. Only China is offering live-action comedy (Detective Chinatown 2) and drama (Dying to Survive).

Of course nobody knows better than Scorsese that the big-budget fantasy/SF film has long been with us. His New York, New York (1977) came out the same year as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, while 1980 saw the release of both Raging Bull and The Empire Strikes Back. But in those years straight-up genre films had a fighting chance. Smokey and the Bandit, The Goodbye Girl, 9 to 5, Airplane!, and others won big box-office.

Scorsese films have landed in the top twenty occasionally (e.g., The Color of Money and The Wolf of Wall Street). On the whole, though, I’m not suggesting that Scorsese now sees himself as competing with the biggest grossers. He’s surely right that today’s superhero films dominate the landscape. But do they squeeze out other films to the degree he suggests?

In some venues, probably yes. Small towns with one or two multiplexes may not have space for the minor-key movie. But bigger towns and midsize cities can be quite hospitable to them. In one week, alongside the big releases, multiplexes in my town of Madison, Wisconsin (pop. about 250,000) played Motherless Brooklyn, Jojo Rabbit, Parasite, The Lighthouse, The Current War, Brittany Runs a Marathon, and documentaries on Molly Ivins and Miles Davis. At least some of these qualify as original vehicles. At its widest release, The Lighthouse played on nearly 1000 US screens, and Jojo Rabbit arrived at over 800.

These are merely data points, not systematic samplings. And you might argue that we’re in the middle of Oscar qualifying season, so more offbeat films are numerous now. Okay, go back to July, the most competitive month for domestic releases. Nationally, the big pictures didn’t prevent the release of Yesterday, Midsommar, Late Night, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Booksmart, The Dead Don’t Die, The Biggest Little Farm, The Farewell, The Art of Self-Defense, Amazing Grace, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood.

Again, not all of these count as auteur vehicles, and several failed domestically, but they still squeezed into multiplexes. The Tarantino film obviously commanded a wide release, but many of the titles I mentioned played on between 1000 and 2000 screens. Booksmart opened on over 2500, Midsommar on 2700.

The industry doesn’t depend on the smaller or more personal titles, but then it seldom has. The biggest box-office successes in the heyday of the studio system were almost never auteur classics. Variety reported that the top domestic hits of 1943 were For Whom the Bell Tolls, Song of Bernadette, This Is the Army, Stage Door Canteen, Random Harvest, Hitler’s Children, Casablanca, Madame Curie, Star Spangled Rhythm, and Coney Island. True, Frank Borzage struck gold with Stage Door Canteen, but it’s not typical of his work. Lubitsch (Heaven Can Wait) and Hitchcock ( Shadow of a Doubt) were far down the list, bested by the likes of Sam Wood, Clarence Brown, and Henry King.

Or take 1952, ruled by The Greatest Show on Earth (De Mille), Quo Vadis, Ivanhoe, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Sailor Beware, The African Queen (Huston), Jumping Jacks, High Noon (Zinneman), and Singin’ in the Rain (Donen/Kelly). True, The Quiet Man hit number 12, and Mann’s Bend in the River number 13. But of the top hundred the only other auteur pictures seem to be Pat and Mike (no. 39), Monkey Business (no, 47), Carrie (no. 54), The Lusty Men (no. 76), and Five Fingers (no. 85).

It seems plausible, then, that in Hollywood “audiovisual entertainment” has overwhelmingly dominated the market for decades. Auteurs seldom win the biggest grosses. But again Scorsese’s career history may have influenced his judgment.

There was a moment, the Holy 1970s, when genre cinema with a personal-vision inflection was occasionally lucrative. The Godfather, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, American Graffiti, Blazing Saddles, Alien, Apocalypse Now, The Shining, and other notably original productions did earn money and awards. Yet in retrospect that seems an interregnum. The top rentals of the following decade, the 1980s, were dominated by Spielberg and Zemeckis. Then there were the usual array of star-driven comedies and action pictures. Genres came back strong, and auteurs had to work within them, or around the edges.

Such is pretty much the case right now. At the top end, perhaps the superhero films are roughly equivalent to the biblical sagas, historical pageants, and theatrical adaptations that roadshowed throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Now as then, a number of auteur films are still getting theatrical releases. The blockbusters keep the lights on and the popcorn moving so that theatres can afford to wedge straight-up genre pictures and offbeat indies into their week. It seems that you can’t run Avengers: Endgame on all 22 screens.

Art vs. craft?

Anthony and Joe Russo directing Avengers: Endgame.

But maybe we shouldn’t think of the big pictures as “audiovisual entertainment.” What’s opposed to that? “Cinema,” Scorsese said. I’d propose that this formulation means “artistic cinema.” Which is to say that we’re in the realm of the classic distinction between art and entertainment.

This has given an opening to the people riled up by Scorsese’s remarks. Admirers of Marvel, DC, and comparable pictures can say that they find them as emotional, revelatory, inspiring, etc. as anything he finds in Bergman or Sam Fuller. They feel it in their bones. And who’s to gainsay that? Scorsese doesn’t have their bones, and neither do you or I.

On more objective grounds, I suggest that Scorsese has floated another distinction. Forget calling some things “cinema” and some things not. I think that he’s distinguishing craft from art.

Let’s say provisionally that craft is the skillful manipulation of the medium to produce the desired effects. Art, on this understanding, can be considered something more. It’s usually grounded in craft, but not always. It’s also formally and emotionally complex, original in its relation to what came before, and offering new experiences on repeated exposure (rather than replays of the original response). Many, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, would add that art induces reflection on ourselves and the world, making us wiser and deepening our humanity.

From this angle, Scorsese’s recognition of the “talent and artistry” of franchise films can be seen as a nod to craft competence. “The technique,” he says, “is very well done.” Our blockbusters are comparable to many of those anonymous hits of the studio era, turned out by skillful but impersonal artisans.

In response, the MCU advocates would need to show that the films go beyond craft. For example, some advocates find in these films the kind of character complexity Scorsese attributes to Hitchcock. He finds that Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest suffers “painful emotions” and an “absolute lostness.” Marvel fans will say something like this about moments in the stories of Tony Stark, Captain Marvel, Captain America, and the Winter Soldier.

Scorsese might reply that these are not complex characters. Yet for many years people said the same about the work of Hitchcock and other Hollywood auteurs. When people started to study them, we saw things differently. Only closer analysis of the comic-book films can give us better grounds to argue about whether their characters exhibit the “contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures” Scorsese champions.

Realism and its rivals

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014); Raging Bull (1980).

A few scattered speculations and I’m done.

I don’t know that we’ve fully recognized that these SF and fantasy franchises descend from earlier forms. Silent crime serials and installment films featuring Dr. Gar el-Hama and Judex had the same reliance on secret identities and world-threatening master villains. Chinese wuxia films gave their knight-errants the power to soar into the air (the “weightless leap”) and emit blasts of energy (“palm power”). The bullet ballets of Hong Kong films have obviously influenced Hollywood action pictures, but we haven’t acknowledged how our comic-book movies incorporate fantasy martial arts techniques. Hollywood owes Asian action cinema more than we usually admit.

But the silent policiers and the fantasy wuxia are flagrantly unrealistic. And Scorsese, more than many of his colleagues, is committed to realism. He couldn’t, I think, make Big Trouble in Little China or Kill Bill. I’d suggest he’s intrinsically out of sympathy with quasi-supernatural action. (Hugo is a historical film, and it’s about a sacred era of Cinema past.) Superhero dramaturgy, I hazard, rubs him the wrong way, and not just because it lacks psychological depth.

I’ve argued elsewhere on this blog that Scorsese makes forays into expressionist and impressionist technique, but they usually issue from a base of harsh realism. His commitment to realism may make it hard for him to engage with the more outrageous narrative conventions of the superhero film.

Here another classic dichotomy suggests itself. If you have to choose between basing your story on plot or character, Scorsese will choose character. In fantasy films, though, character motive and reaction are based on elaborate plot machinations. These films depend a lot on elaborate fake identities, as well as recognitions of hidden kinship. She’s my sister! He’s my father! Such devices serve to provide intricate genealogies and networks of relationships for fan homework.

Likewise, theatrical melodrama and adventure fiction from the nineteenth century supply superhero sagas with orphans of mysterious parentage, duels, hairbreadth escapes, family secrets, coded documents, precious but mysterious objects, and other franchise conventions. These are woven into complex schemes and counter-schemes of the sort found in the silent crime serials. But all these features run counter to the psychological conflicts that animate Scorsese’s plots.

Recognitions of kinship rely in turn on a plot strategy that’s worth discussing a little more; I suspect it yields much of the emotional resonance that fans enjoy. These films rely on courtship and romantic rivalries throughout, of course, as well as friendships forged and broken. These are standard for most American genres. But I’ve been surprised at how often family relations are developed in complicated ways.

It’s not just Star Wars. The Marvel Universe relies heavily on kinship to sustain its plots, as well as its pathos. Tony Stark and Pepper Potts have a daughter, as does Scott Lang. Hawkeye has a family, as does T’Challa, whose cousin N’Jadaka becomes a prime adversary. Nebula and Gamora are pressured to be dutiful daughters to Thanos. Thor and Loki share a mother, Frigga. You can argue that Tony Stark becomes a father-figure for Peter Parker. Other characters are more isolated, but for some of them, notably Natasha and Bucky, the Avengers team constitutes a surrogate family.

Marvel’s focus on the family asks us to exercise the skills we must bring to classic mythology, nineteenth-century novels, and TV soap operas. We need to keep track of who’s related to whom, and what in their past encounters can arouse obligations and conflicts. I don’t think that plots resting on such dense kinship relations are of great appeal to Scorsese; his families, when they’re present at all, are pretty small-scale (Raging Bull, Cape Fear, Shutter Island, The Age of Innocence).

Most of all, when Scorsese speaks of these films shying away from risk, I suspect he’d include their avoidance of narrative risk. In fantasy and SF, nobody need really die. Hero, villain, love interest, and sidekick can return in a parallel world, or they can be resuscitated through a new gadget. The worst outcome need not be the worst, as when Avengers: Endgame uses nanotech and time travel to rewrite the past. Plot mechanics again. Despite all the assurances that Tony Stark is really, really gone, we could find a way to bring him back if Downey wanted to sign on again. (Black Widow is being resurrected for a prequel adventure.) But there’s no bringing back Sport from Taxi Driver or Rodrigues from Silence—except in a prequel, another convention that Scorsese would likely disdain.

I’m just spitballing here, but for Scorsese and other stylized realists like Michael Mann, the comic-book convention of eternal return might seem merely juvenile wish fulfillment. Something really has to be at stake, and ultimates must be faced’ Danger and death are real. This is grown-up drama.

I’m not intrinsically opposed to the conventions ruling comic-book movies myself. In general, I think that plot is as underrated as character is overrated. (I’d rather give up the distinction altogether, but that’s another story.) Superhero films are mostly not to my taste, but I think they’re worth studying as intriguing contributions to trends in modern cinema. My point is just that the personal aesthetic of Scorsese, as both cinephile and cineaste, doesn’t fit very well with the elaborate, ever-changing rules of the magical MCU. He finds enough magic in a sinuous tracking shot, or a carefully synced doo-wop song, or an unexpected angle, or a wiseguy shouting match. That is Cinema.

There are other questions we might ask about Scorsese’s remarks. For instance, when he celebrates the thrill of communal moviegoing as a central feature of Cinema, he seems to ignore the fact that the franchise pictures are our prime multiplex attractions. Many viewers slot the more “personal films” into a future Netflix queue, but they commit themselves to seeing the big films on the big screen. That choice can yield contemporary viewers some of the electricity that Scorsese found at a screening of Rear Window. And when they’re not checking their text messages or chatting loudly with their pals, they might even give themselves up to laughs, screams, and applause, just as in the old days.

Since I wrote this, though, something much more draconian than superhero pictures may threaten non-franchise pictures. On Monday, Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim said that the Department of Justice is moving to end the consent decrees that have governed Hollywood studio conduct since 1948. (See here and here.)

The implications of this are staggering. We may see the return of block and blind booking, the prospect that a studio could own a theatre chain (and give favored place to its own pictures), and the decline of independent producers and art houses that favor smaller films. Nonsensically, Delrahim quoted an earlier Scorsese remark about his craft: “Cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” Delrahim went on: “Antitrust enforcers, however, were not cast to decide in perpetuity what’s in and what’s out with respect to innovation in an industry.” Thus the ideology of predatory “disrupters” goes on, and even auteurs are unwillingly recruited to the enterprise.

Thanks to Jim Danky for calling my attention to the McFadden comic, and to Jeff Smith for discussions of Scorsese’s arguments. Thanks as well to Colin Burnett for discussion of the Bond saga.

My lists of top-twenty films come from the European Audiovisual Observatory’s publications Focus 1999 and Focus 2019.

I’ve left aside other writers’ analyses of Scorsese’s views. I benefited from reading Ben Child and Helen O’Hara in The Guardian, Christopher Orr’s older review in The Atlantic, and Zachary Zahos at Playback. Also pretty forceful is Kevin Feige’s defense of the MCU, which I discovered only after writing this entry. He argues for Marvel films’ value on several grounds, including their display of positive social values. And just before I posted this, the Russo brothers weighed in.

Here are other Scorsese comments made before the New York Times piece appeared. After his BAFTA David Lean lecture on 12 October, he reiterated his view.

Theatres have become amusement parks. That is all fine and good but don’t invade everything else in that sense. That is fine and good for those who enjoy that type of film and, by the way, knowing what goes into them now, I admire what they do. It’s not my kind of thing, it simply is not. It’s creating another kind of audience that thinks cinema is that. If you have a child and the child wants to see the picture, what are you going to do? It’s up to you. The audience that sees them now, the fans that see those pictures now, they were raised on pictures like that.

The technique is very well done, but there is only one Spielberg, only one Lucas, James Cameron, it’s a different thing now. It’s an invasion, so to speak, in the theatre. . . .

We are in a moment not only of evolution but of revolution, in pretty much the whole world, everything we know, the old political systems, it’s almost as if the 21st century is beginning now and technology has gone with it and that means cinema goes with it.

Yes, see a movie in a theatre, it’s the best with an audience, but the actual concept of cinema has become something that is not definable. Something can play as a hologram, something can play as virtual reality, maybe there is going to be an extraordinary epic in virtual reality at some point. We have to start expanding what we think of as narrative, music, literature, art and particularly the visual image.

Granted, this whole passage is a bit baffling. It’s not completely clarified in a press conference the next day at the BFI London Film Festival. The relevant section starts at 16:26.

It’s also interesting that Benedict Cumberbatch (aka Dr. Strange) defends the need for auteurs.

Some comments on Sarris’s career and the vagaries of auteur theory are here. I discuss Black Panther and its debt to classical Hollywood storytelling here.

Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas (2007).

Is there a blog in this class? 2019

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries cite Film Art, but most of them are relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Readers who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we have posted well over 900 entries, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Last year for the first time I included recommendations for potentially useful videos in our series “Observations on Film Art” (a sort of extension of this blog) on the FilmStruck streaming service. Every month Jeff Smith (also our collaborator on Film Art), David, and I had contributed a visual essay that applied concepts from Film Art: An Introduction to a film (or films) streaming on FilmStruck, which began in November of 2016 and ended in November of 2018.

Fortunately in April, 2019, that platform was replaced by The Criterion Channel, which had been a major attraction as part of FilmStruck. The essays that we had contributed to FilmStruck have all been reposted on the new service, and we have continued to contribute monthly essays. As of now there are 29 essays online. See last year’s “Is there a blog in this class? 2018” for the earlier videos. (For information on the changeover of services, see here.)

Chapter 1 Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business

I’ve written an occasional series on the progress of 3D in modern cinema. In an entry concentrating on exhibition rather than the technology or the movies, I talk about the decline in the number of 3D screenings as they lose popularity: “3D in 2019: RealDivided?”

In Chapter 1 we briefly deal with the concept of the author or auteur of a film. David provides an example of how one characterizes an auteur’s work in “Terence Davies: sunset songs.” Is Michael Curtiz as clearly an auteur as Orson Welles is? This entry considers some evidence.

No year on the blog is complete, it seems, without something on Hitchcock. This time David considered Notorious, preparing the way for a video essay for the Criterion release of this masterpiece.

At greater length, our updated e-book on Christopher Nolan is a study of him as an auteur with a “formal project.” David discusses the changes in “Christopher Nolan: Back into the Labyrinth.” A later entry considers (unconvincing) critical attacks on Nolan’s work.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

In The Criterion Channel video essay, #25, “Lydia and the power of flashbacks,” David discusses the somewhat experimental ways in which flashbacks are used in Julien Duvivier’s 1941 romance. He extends his analysis in “Lovelorn LYDIA: A new installment on The Criterion Channel.”

I analyze one aspect of narrative form in The Favourite: “Balancing three protagonists in THE FAVOURITE.”

Narrative options both old (the 1940s) and new (Happy Death Day 2U) are considered in an entry on how incidents can be repeated and varied, within a film and from film to film.

This chapter of Film Art discusses narration in terms of depth, how much of characters’ knowledge and thoughts are revealed to us. In “Observations on Film Art” #26 on The Criterion Channel, Jeff examines technique that allow us access to the protagonist’s mind in “Memories of Underdevelopment.” He expands on that analysis in “Politics and Subjectivity: MEMORIES OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT on The Criterion Channel.”

Can the tools of narrative analysis shed light on The Narrative of contemporary US politics? David tries in the entry “Reliable narrators? Telling tales on Trump.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-scene

#27 in our “Observations on Film Art” on The Criterion Channel, David examines the intricate mise-en-scene of Kenji Mizoguchi: “Games of Vision in STREET OF SHAME.” He elaborates on the blog with “How to hypnotize the viewer: Mizoguchi’s STREET OF SHAME on The Criterion Channel.”

David analyzes the staging of a scene in Augusto Genina’s Il Maschera e il Voto (The Mask and the Face, 1919) in “Sometimes an actor’s back …” Those of you teaching Film History: An Introduction might find this entry useful in relation to the discussion of tableau staging in Chapter 2.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinemagraphy

In The Criterion Channel’s #24 in the “Observations on Film Art” series, Jeff Smith analyzes “Widescreen Composition in Shoot the Piano Player.” He offers additional commentary on the subject in a blog entry, “On The Criterion Channel: Jeff Smith on SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER.”

Chapter 6 The Relationship of Shot to Shot: Editing

In The Criterion Channel’s #23 video, “Mutations of Memory–Editing in Hiroshima Mon Amour,” David discusses the film’s complex, innovative use of editing to create flashbacks. He expands on that analysis in the blog entry, “On The Criterion Channel: Five reasons why HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR still matters.”

Dissolves provide a way to join shot to shot. They’re usually used sparingly and in conventional ways (flashbacks, ellipses). In “Observations on Film Art” #22 on The Criterion Channel, “Dissolves in The Long Days Closes,” I discuss how dissolves become a prominent formal device in Terence Davies’ film.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

Guest blogger Jeff Smith analyzes the music in True Stories: “From transistors to transmedia: Talking Heads tell TRUE STORIES.”

Jeff takes an informative look at the five songs from 2018 films nominated for Oscars in “Oscar’s siren song: The return: a guest post by Jeff Smith.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes cutting and framing in one scene in the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs in “The spectacle of skill: BUSTER SCRUGGS as master-class.”

The great critic André Bazin decisively shaped our sense of how to understand film form and style. David explores some of his ideas in “André Bazin, man of the cinema” and an essay, “Lessons with Bazin.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David on film noir: “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: much ado about noir things.”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

Reporting from the Vancouver festival, David discusses two documentaries that might be useful to show if you program films by either of these directors for your class: The Eyes of Orson Welles and Bergman: A Year in the Life. See his “Vancouver 2018: Two takes on two directors.”

David on three documentaries shown at our hometown film festival this year, in “Wisconsin Film Festival: Not docudramas but docus as dramas.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We were lucky enough to return to the Venice International Film Festival last year, again offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premiere of Damien Chazelle’s First Man and is based on a single viewing. The second discussed Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma and Mike Leigh’s Peterloo.The third offered David’s thoughts on the posthumous release version of Orson Welles’s The Other Side of the Wind. In a fourth, I dealt with five films from the Middle East, including Amos Gitai’s A Tramway in Jerusalem. David considers variants of wrong-doing in films from around the world, including Zhang Yimou’s Shadow and Erroll Morris’ American Dharma. Sixth and last was my longer analysis of László Nemes’s brilliant but challenging second feature, Sunset. We plan to carry on this tradition of comments on new films when we attend the Venice International Film Festival next month.

Our annual visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival yielded more brief analyses of new films. In “Vancouver 2018: Landscapes, real and imagined,” David looks at some recent Asian films, including Kore-edge Hirozaku’s Shoplifters. In “Vancouver 2018: A panorama of the rest of the world,” I comment on three films by important international directors: Nuri Bilge Ceylon’s Turkish The Wild Pear Tree, Benedikt Erlingsson’s Icelandic Woman at War, and Pavel Pavlikowski’s Polish Cold War.

I followed up with more international films in “Vancouver 2018: Panorama of the rest of the world, the sequel“: Matteo Garrone’s Italian Dogman, Nina Paley’s American Sedar-Masochism, Wolfgang Fischer’s Austrian Styx, and Christian Petzold’s German Transit. David wrote about crime films (and a TV show) in “Vancouver 2018: Crime waves.” These notably included Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Our wrap-up, “Vancouver 2018: A few final films,” again had an international flavor, commenting on Jafar Panahi’s Iranian 3 Faces (his defiant fourth feature since the government banned him from filmmaking for twenty years), Nadine Labaki’s Lebanese Capernaum, and Ciro Guerra and Cristina Gallego’s Colombian Birds of Passage.

Looking back on these two festivals makes it clear that 2018 was an extraordinary year for the cinema!

David analyzes True Stories on the occasion of its release on Blu-ray: “Pockets of Utopia: TRUE STORIES.”

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

Teaching film history? My annual choice of the ten best films from 90 years ago offers some familiar and not-so-familiar titles: “The ten best films of … 1928.” I also consider two releases of major German silent films.

Many of our entries from Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna consider older films, especially those from 1919 in “German and Scandinavian classics.” I discuss some major African films in “Who put the pan in Pan-African cinema?”

I discussed a Blu-ray release of two rare films by Mary Pickford in “Pickford times two.”

A more recent trend in film history, that of the improvised independent American film, is considered in our review of J. J. Murphy’s book Rewriting Indie Cinema.

Finally, for Film Art: An Introduction users, an account of how Jeff Smith, David, and I revised our textbook for its twelfth edition.

After forty years, we’re still grateful to teachers and students who have found Film Art: An Introduction useful in their study of cinema.