Il Cinema Ritrovato 2019: Who put the Pan in Pan African cinema?

Sunday | July 7, 2019 open printable version

open printable version

Muna Moto (1975)

Kristin here–

With the plethora of films on offer this year at the XXXIII edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I decided that a necessary strategy for choosing those to watch would be to follow certain threads faithfully and then fill in the remaining time-slots with bits and pieces from other threads. (The entire program, with notes, is online here.)

A program that formed part of the core of my viewing for the festival’s eight and a half days was “Cinemalibero. FESPACO 1969-2019.” It was curated by Cecilia Cenciarelli, whose program notes explain the post-colonial context behind this fiftieth-anniversary celebration:.

“Decolonisation of the screen” also spread at a grassroots level: birthplace of the future FESPACO, the film club of the Centre Culturel Franco-Voltaïque in Ouagadougou (capital of the then Republic of Upper Volta) organised the first Semaine du cinéma africain in February of 1969. Cinema filled every venue of the city: the Nadar and Olympia cinemas, schools, offices, the People’s House and Hôtel Indépendance, the legendary filmmakers’ headquarters. Over 50 films made in Senegal, Niger, Upper Volta, Cameroon and Benin by directors like Sembène, Samb, Traoré, Alassane and Sita-Bella were screened.

The first festival in 1969 has been credited with bringing together filmmakers from all over the continent to launch an effort to support Pan African filmmaking. Short documentaries showing FESPACO in its early years, mostly by Tunisian filmmaker Mohamed Challouf, were shown before several of the features.

The program was built around eleven films directed by pioneers of the festival and the Pan African Cinema effort in general. Of those, eight were recent restorations–some of them dated 2019. Some of these films have been available online in copies with poor visual quality, and I hope now the new prints will make their way onto Blu-ray or DVD. (Ousmane Sembene, the African filmmaker best known in the West, was not represented in the program, but he was instrumental in the founding of FESPACO.)

A key problem in restoring and distributing these classic African films is the fact that many of them had to be processed in European laboratories, often in France, and the original negatives and other elements were stored there. In some cases their whereabouts are now unknown, and tracking them down has been a key factor in making them accessible again.

Here is a brief description of each film, in the order in which they were shown. In keeping with the theme of Pan African cinema, every film originated in a different country.

De quelques événements sans signification (1974, Morocco)

As the program demonstrated, the mid-1970s were a key period for the establishment of Pan African cinema. Many show the influence of European filmmaking, since several African filmmakers studied filmmaking abroad.

Mostafa Derkaoui’s 1974 film shows the influence of Godard. Its early section consists of an extended scene in a bar, where telephoto shots move across a group of filmmakers debating what direction the establishment of Moroccan cinema should take. They take to the streets to explore the situation of workers.

When one of them kills his boss, the plot takes shape as the filmmakers focus on his situation as the subject of their film. Ultimately the worker rejects their interpretation of his crime, leaving the question of how Moroccan cinema should proceed up in the air.

Les bicots-négres, vos voisins (1974, Mauritania)

Two years ago, Med Hondo presented his West Indies (1979) at Il Cinema Ritrovato. It was my introduction to his work. As I reported at the time, Hondo was thoroughly ingratiating and was moved to tears by the enthusiastic applause we gave his film. This year the two diretors who attended, Jean-Pierre Kinongué-Pipa and Souleymane Cissé, were similarly touched by their reception. It is a pity that such recognition has been so long in coming. Hondo’s death in March of this year and Moustapha Alassane’s in 2015 perhaps deprived us of other guests who might have realized that their films will live on as classics.

Hondo’s Les bicots-négres, vos voisins (roughly, “The Arab-niggers, your neighbors”), also shows a strong influence of Godard’s political films of the 1970s, and yet it is thoroughly original as well. The film breaks into seven separate sequences–all politically didactic and yet greatly varied in their approaches. The results is continually riveting.

Aboubakar Sanogo’s program notes describe this variety:

It comprises seven sequences exploring, respectively, the conditions of possibility of cinematic representation in Africa (the opening sequence), historical dissonance through the dialectic of past and present (the post-credit sequence), a flashback to the eve of African independence (the imaginary garden party sequence), the predicaments of the post-colony, an assessment of the living condition of migrant workers and the actions taken to transform these conditions, and a final sequence in a circular mode, which returns to the new cinema.

Thanks in part to these recent restorations, Hondo has emerged as one of the giants of Pan African cinema.

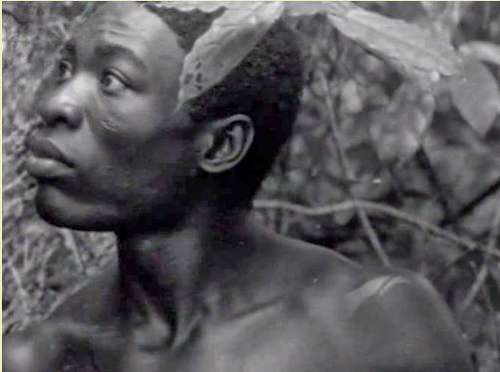

Muna Moto (1975, Cameroun)

Jean-Pierre Dikongué-Pipa was present to introduce this, one of the first films made in Cameroun. Though hampered by budgetary and censorship constraints, Muna Moto is an affecting story attacking both polygamy and the dowry tradition. The basic premise is that for any man in this culture, fathering a child is of prime importance, more than his love for any of his wives.

The protagonist N’gando, a poor, hard-working young man (see top image), aspires to marry N’Domé, a woman who genuinely loves him. The high dowry necessary to arrange such a marriage, however, presents a nearly insuperable barrier. While N’gando struggles to raise the money through low-paying manual labor, his rival, the wealthy M’bongo, who already has three wives who have failed to give him a child, takes the woman as a fourth wife in the hope of conceiving a baby.

She is already pregnant by N’gando, however. (The title translates as “Another’s Child.”) The film becomes a struggle in which N’gando tries to kidnap the baby girl.

The scene of the kidnapping opens the film, without explanation. Only gradually through flashbacks do we come to understand his motives and the tragedy of the situation. Muna Moto effectively uses the flashback conventions of European art cinema (Dikongué-Pipa had studied at the Conservatoire indépendent du cinéma français in Paris) to tell a thoroughly indigenous story with beautiful black-and-white cinematography.

The Cineteca di Bologna’s L’Immagine Laboratory restored the film in 2019 with the support of The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project. Ideally this will make the film widely available on home video and for viewing at festivals.

Le retour d’un aventurier (1966, Niger), Samba le grand (1977, Niger), and Kokoa (2001, Niger)

Moustapha Alassane directed about two dozen films, mostly shorts. He is credited with being one of the few major African directors who was completely self-taught in filmmaking. Three of his shorts were shown in one program. Le retour d’un aventurier suggests how foreign cultures adversely affect regions of Africa. A popular young man from a village returns from a trip abroad, presenting his friends with six-shooters and cowboy outfits.

At first these would-be cowpokes seem ludicrously out of place, and yet when they begin to terrorize their peaceful village, their violence becomes all too familiar.

Alassane was a pioneer of African animation. His Samba le grand, the first color animated film made in Africa, combines hand drawings and simple cloth dolls to tell a traditional African folk tale effectively.

The most engaging of the three films on the program was Kokoa, a more elaborate and sophisticated cartoon. Using puppet animation, Alassane presents a traditional Niger-style wrestling match among frogs and lizards, with a sideways-moving crab hilariously mimicking the typical movements of a referee (above).

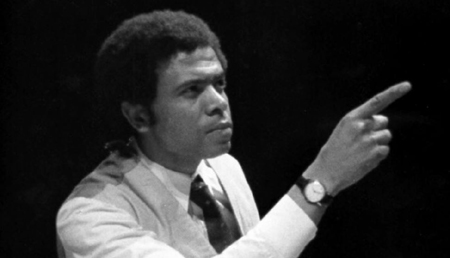

Baara (1978, Mali)

One of the most revered African directors, and certainly so among those living, is Souleymane Cissé.

Cissé was present for a Q&A session after the film. He was forthright in declaring that the somewhat faded print shown was too pink and that he would rather have had it destroyed than shown publicly. Cenciarelli assured him and us that it was the best 35mm print available, and audience members declared themselves delighted to see the film even in a less than ideal copy. Cissé stuck by his opinion and pointed out that the original negative survives intact in Paris. Ideally a restoration comparable to the ones shown in this series will someday be done.

He also mentioned that although he was jailed for accepting French funding for his first feature, Den Muso (“The Girl,” 1975), he still does not know the real reason for his arrest. He wrote the screenplay for Baara (Work) while in jail.

The film tackles the issue of the rise of a working-class in a country that had been largely rural and agriculturally based. The central figure is an uneducated young peasant who comes to the city and works as a porter. His cousin, educated and westernized, attempts to help him but is himself oppressed by the corrupt company officials above him. (Both are seen in the image above.) Unlike many other African directors who went abroad to study filmmaking, Cissé attended VGIK in Moscow (as did Sembene). Possibly the experience accounts for the narrative’s distinctly Marxist tone.

For more on Baara, see Richard Brody’s review on the occasion of a recent screening of the film at the New York African Film Festival.

La petite vendeuse de Soleil (1999, Senegal) and Le franc (1994, Senegal-Switzerland-France)

Earlier this year I reported on the showing of a restored print of Djibril Diop Mambéty’s, Hyenas (1992), at the Wisconsin Film Festival. After Touki Bouki (1973), it was the second of two full-length features Mambéty made before his early death at the age of 53. He followed Hyenas with the two short features (45 minutes each) from an intended trilogy entitled Contes des Petites Gens. The pair were shown together at the festival.

La petite vendeuse de Soleil (The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun) is perhaps Mambéty’s greatest film, though it is difficult to be objective given the utter charm of its central character, along with the performance of Lissa Balera in the role of Sili. Looking past that, though, the film is beautifully shot in locations in and around Dakar, and the narrative unrolls with a calm surety that packs a great deal into a short length.

Mambéty establishes the initial setting in the outskirts of Dakar in a leisurely fashion with dawn shots of the poverty-stricken area. We glimpse Sili limping past the hovels of the suburban slum, though we see other marginal figures as well–including a man pounding large pieces of stone into gravel. The planes taking off and landing behind him establish the theme of poverty juxtaposed with the modern, wealthy society of the city.

Soon we become attached to Sili as a friend takes her into the city to beg. She notices boys making money selling newspapers and soon becomes the first female to become a newspaper seller. Through a fluke of good luck, a wealthy man who sees her as a sign of African progress gives her a large bill to buy all her papers. Immediately confronted by a policeman over the large bill, she defiantly leads the way to the police station and talks the chief into releasing her and a woman charged with theft without reason. Once freed, she celebrates her good fortune by leading a cheerful dance in the street (above) and treating her friends to sodas.

She buys her blind grandmother a large umbrella to shade her as she sings for a living, and she gives small coins to her fellow beggars. Her generosity endears her to a seller of the rival newspaper, who becomes her defender. Her cheerful resilience persists despite bullying by a gang of rival newspaper sellers.

The film combines a realistic view of the grim life of street people in Dakar with a vision of hope represented by Sili. At the end, Dembéty dedicates it to the city’s street children.

Le petite vendeuse de Soleil was restored in 2019. Ideally, the currently available prints, with their somewhat soft images, will be replaced with this impressive version.

The second film in the series, Le franc, is not as engaging. It centers around Marigo, a shiftless man who is beleaguered by his landlady for back rent on his simple shack. He purchases a lottery ticket and, to prevent its loss, glues it to the shack’s door. When the ticket wins, he carries the door to the lottery agency, only to be told that a number on the back of the ticket is essential to allow him to collect the money. The main action is mainly extended slapstick as Marigo clumsily carries the door, frequently falling or dropping it. It’s an entertaining film but lacks the depth of La petite vendeuse du Soleil.

La femme au couteau (1969, Ivory Coast)

Timité Bassori’s La femme au couteau (“The woman with a knife”) is the earliest of the feature films shown at this year’s festival. Like numerous other directors from the continent, Bassori studied at IDHEC in Paris. The influence of 1960s European art cinema seems stronger in this film than in the others in this program.

The story is entirely based around the psychological problems of a young, unnamed, westernized man, whose romance with an unnamed woman is hampered by his disturbing hallucinations of a woman threatening him with a knife. Deciding to avoid traditional African cures, he finally is committed to a mental institution. Ultimately he recalls the trauma that had triggered his psychological problems. The film is skillfully made, with Bassori memorable as the protagonist, but it seems the kind of story that could have been made in a European country as well as an African one.

The excellent print was a product of the African Film Heritage Project, a program within the The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project; it was restored at the Cineteca di Bologna in 2019.

Wend Kuuni (1982, Burkina Faso)

This classic film was restored in 2017 by the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique. In his introduction, archivist Nicola Mazzanti expressed bitterness that Wend Kuuni has been neglected by distributors and exhibitors for decades. This new print should give it the second life that it richly deserves.

As Mazzanti pointed out, this is one of the few African films that portrays the continent as it was before colonialists invaded and changed the local culture forever.

The film follows the story of a mute orphan who is discovered nearly dead and taken in by a local farmer. (The title translates as “God’s Gift” and is the name bestowed upon the boy by his adoptive father.) Rather than develop a straightforward drama of the boy’s character arc, director Gaston Kaboré (who collaborated in the restoration) creates what is nearly a documentary on traditional rural life. We see the young protagonist herding sheep, the women of the family grinding grain, and so forth. Any progression in the plot takes place at wide intervals. The orphan’s origins and the reason for his muteness remain lingering mysteries but are not much dwelt upon until late in the film, where flashbacks and a traumatic discovery restore his voice and reveal his past.

Probably coincidentally, these two films about trauma and recovery through the recognition of a disturbing event in the past were shown back to back. But while La femme au couteau calls upon modern notions of psychology, Wend Kuuni simply presents the boy’s muteness and eventually shows his recovery without any reference to psychological concepts.

I am happy to say that some of these African films featured in our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, from its earliest edition in 1994: Les Bicots-Négres, vos voisins; Muna moto; and Wend Kuuni. We also discussed other films by Cissé and Sembene. At the time, few of these films were available for screening. It is encouraging to see such films revived and disseminated more widely.

Baara (1978).

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.