Archive for the 'Film history' Category

ON THE HISTORY OF FILM STYLE goes digital

Dust in the Wind (1986).

DB here:

I was born to write this book.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

So I rashly claim in the Preface to the new edition of On the History of Film Style. That’s not to say somebody else couldn’t have done it better. It’s just that the book’s central questions tallied so neatly with my enthusiasms and personal history that I felt an exceptional intimacy with the project.

Baby-boomer narcissism aside, there are more objective reasons for me to tell you about the book’s revival. It came out in late 1997 from Harvard University Press, and it went out of print last fall. Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel, it has become an e-book, like Planet Hong Kong, Pandora’s Digital Box, and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

The new edition is substantially the original book; the pdf format we used didn’t permit a top-to-bottom rewrite. Errors and some diction are corrected, though, and the color films I discuss are illustrated with pretty color frames, not the black-and-white ones in the first edition. The new Preface and a more expansive Afterword explain the origins of the book and develop ideas that I pursued in later research.

The book analyzes three perspectives on film style as they emerged historically. One, what I call the Basic Version, was developed in the silent era and saw the discovery of editing as the natural development of film technique.

The second version, associated with critic André Bazin, modified that conception by stressing the importance of other stylistic choices, notably long takes and staging in depth. I call this the Dialectical Version because Bazin claimed that these techniques were in “dialectical” tension with the pressures toward editing.

A third research program, spearheaded by filmmaker and theorist Noël Burch, argued that the development of film style was best understood as the ongoing interplay between two tendencies. There’s a dominant style Burch called the Institutional Mode. Responses to that mode are crystallized in alternative practices–the cinema of Japan, for instance, or the “crest-line” of major works associated with modernist trends.

The book goes on to show how a revisionist research program launched in the 1970s built upon these earlier perspectives. Younger scholars sought to answer more precise questions about certain periods and trends. The revisionist impulse is best seen in debates on early cinema, which I survey.

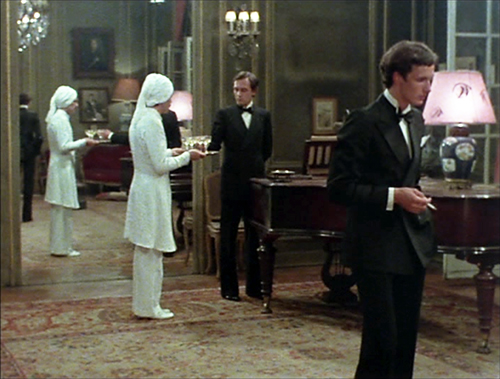

The book so far is historiographic, tracing out other writers’ arguments about continuity and change in film style. In my last chapter I try to do some stylistic history myself. I analyze particular patterns of continuity and change in one technique, depth staging. Certain conceptual tools, like the problem/solution couplet and the idea of stylistic schemas, can shed light on how certain staging options became normalized in various times and places. In turn, directors like Marguerite Duras, in India Song (1975), can revise those norms for specific purposes.

On the History of Film Style was generally well-received. John Belton, while voicing reservations, called it “a very good book. Anyone seriously interested in Film Studies should read it.” Michael Wood wrote in a review that “Bordwell is always sharp and often funny” (I try, anyhow) and called the last section “a brilliant account of the history of staging in depth.” The book has been used in some courses, and I’m happy to learn that there are filmmakers who find it useful. It’s been translated into Korean, Croation, and Japanese.

The book is available for purchase on this page. It’s priced at $7.99, a middling point between our other e-pubs. It’s a bigger book than Pandora ($3.99) and the Nolan one ($1.99), but it’s not an elaborate overhaul like Planet Hong Kong 2.0 ($15). Selling the book helps me defray the costs of paying Meg and digging up color frames. In any event, the new version is much cheaper than the old copies available at Amazon. It’s almost exactly the price of two Starbucks Caffe Lattes (one Grande, one Venti).

The archives and festivals that made the book possible are thanked inside, and they’ve continued to be hospitable and encouraging over the last two decades. Equally supportive are the students, colleagues, and cinephile friends with whom I’ve discussed these issues. So I reiterate my thanks to them all. And I hope this new edition, if nothing else, stimulates both viewers and researchers to explore the endlessly interesting pathways of visual style in cinema.

La Mort du Duc de Guise (1908).

Ninotchka’s mistake: Inside Stalin’s film industry

DB here:

It’s a commonplace of film history that under Stalin (a name much in American news these days) the USSR forged a mass propaganda cinema. In order for Lenin’s “most important art” to transform society, cinema fell under central control. Between 1930 and 1953 a tightly coordinated bureaucracy shaped every script and shot and line of dialogue, while Stalin frowned from above. The 150 million Soviet citizens were exposed to scores of films pushing the party line.

True? Not quite.

When cows read newspapers

The Miracle Worker (1936).

In the film division of the University of Wisconsin—Madison, we’ve developed a reputation for revisionism. We like to probe received stories and traditional assumptions. In Soviet film studies, Vance Kepley’s In the Service of the State challenged the idealized portrait of Alexandr Dovzhenko, pastoral poet of Ukrainian film, by tracing his debts to official ideology. In my book on Eisenstein, I suggested that this prototypical Constructivist opens up a side of modernism that is artistically eclectic, and even conservative in its gleeful appropriation of old traditions.

Now we have a new book telling a fresh story. Maria (“Masha”) Belodubrovskaya’s Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

draws upon vast archival material to argue that filmmaking, far from being an iron machine reliably pumping out propaganda, was decentralized, poorly organized, weakly managed, driven by confusing commands and clashing agendas. Censorship was largely left up to the industry, not Party bureaucrats, and directors and screenwriters enjoyed remarkable flexibility.

Was this an ideological juggernaut? Aiming at a hundred features a year, the studios were lucky to release half that. In 1936 95 films were planned, but only 53 were produced and 34 made it to screens. From 1942 on, those millions of spectators saw only a couple of dozen annually. The nadir was 1951, with 9 releases. (Hollywood studios released over 300.) The flood of propaganda was more like a trickle. Theatres were forced to run old Tarzan movies.

When quantity became thin, apologists claimed that quality was the true goal. But Ninotchka’s hope for “fewer but better Russians” wasn’t realized in the film domain. Critics and insiders admitted that nearly all the films that struggled into release were mediocre or worse.

Not According to Plan shows that Soviet institutions were incapable, by their size, organization, and political commitments, of organizing a mass production film industry. Efforts to set up something like the U.S. studio system ran up against obstacles: there weren’t enough skilled workers, and decision-makers clung to the notion of the master director. Boris Shumyatsky, who visited Hollywood and tried to create something similar at home, got his reward at the muzzles of a firing squad. But brute force like this was rare; there were few administrators and creators to spare.

The great plan was to have a Plan—specifically, a thematic one. Production would be based on an annual cluster of powerful topics like “Communism vs. capitalism” and “Socialist upbringing of the young.” Personnel were slow to realize that themes were not stories, let alone gripping ones, and the real work of imagination remained un-plannable. Starting from themes rather than plot situations, the overseers could judge only final results, which meant enormous investments in development and production—all of which might never yield a politically correct movie.

Production, wholly divorced from distribution and exhibition, couldn’t count on the vertical integration of Hollywood. Masha shows in rich detail how policies and routines worked against large-scale output. One of the most striking of those policies was the veneration of directors. A great irony of the book is that Hollywood filmmaking, with its platoons of screenwriters both credited and uncredited, was more collectivist than production in the USSR. Soviet directors enjoyed enormous stature and power. They were often the moving force behind a production, bringing on writers and then recasting the script during shooting. Assemblies of directors formed review committees, discussing and often defending their peers’ work. As Masha puts it:

The filmmaking community, and specifically film directors, never gave up on the standard of artistic mastery. They listened to the signals sent by the Soviet leadership, but then incorporated these into their own professional value system, which developed in the 1920s outside the purview of the state. Using the state’s discourse of quality and their peer institutions, they enforced their own shared norms of artistic merit.

The downside of this system, plan or no plan, was that when the film didn’t pass muster, the director was to blame. Yet the twenty or so “master” directors could survive failed projects. New talent wasn’t trusted; there were too few directors; and most basically, the organization of production remained artisanal. The role of the producer (let alone the powerful producer) scarcely existed. To a surprising extent, Soviet cinema encouraged the director as auteur. How’s that for revisionism?

Screenwriters weren’t as powerful, but they did their part. Masha has a fascinating chapter on the changing conceptions of the Soviet screenplay. The “iron scenario,” modeled on a Hollywood shooting script, was intended to lay out the film in toto, so directors couldn’t overshoot or make changes. This initiative, predictably, failed. There followed other variants: the butter scenario, the margerine scenario, and the rubber scenario (no kidding), then the emotional scenario and the literary scenario.

Masha traces the work process of screenwriting and the mostly futile efforts of literary figures to leave their stamp on a production. A similar stress on process characterizes her occasionally hilarious case studies of censorship. Some of these expose the limits of industry self-censorship. One agency signs off on a film, the next one castigates it, the next one reverses that judgment, Pravda weighs in, and finally Stalin speaks up—with a completely unpredictable verdict, à la Trump. The tale of Medvedkin’s The Miracle Worker, which jumped through all the hoops and wound up being banned after initial screenings anyhow, might have been written by Zoshchenko or Ilf and Petrov. Among the elements judged “absolutely impermissible” were shots of cows reading newspapers.

The artistic and popular success of Soviet films during the New Economic Policy (1921-1928) had spurred hopes for a mass-market sound cinema that was also of high quality. What crushed that dream? Masha gives us the hows (the machinations of the studios and government bodies) and the whys (the underlying causes and rationales). Not According to Plan is a trailblazing study of what she calls “the institutional study of ideology.” It’s also a quietly witty account of the failures of managed culture. How could artists be engineers of human souls if they couldn’t engineer a movie?

But go back to the quality issue. What were those Stalinist films like artistically?

Socialist Formalism

Three projects I’ve undertaken led me to Stalin-era cinema. Nearly all English-language film histories ignored it, or reduced it to boy-loves-tractor musicals. So Kristin and I wanted our textbook Film History: An Introduction to consider it. (Revisionism again.) My Cinema of Eisenstein and On the History of Film Style built on what I saw at archives in Brussels, Munich, and Washington DC.

As a result I sought to mount an argument that Stalinist cinema was worth our attention, especially from the standpoint of film technique. The run-of-the-mill productions seemed fairly shambolic, but the top-tier dramas revealed an academic style that interested me. Some films recalled, even anticipated, innovations taking hold in Europe and America, but other creative choices were surprisingly offbeat, and not what we associate with standard propaganda.

For one thing, it was clear that montage experiments didn’t end with the 1920s, the arrival of sound, or even the “official” establishment of Socialist Realism around 1934. Granted, classic continuity editing rules the fiction films of the 1930s and 1940s, and the most flagrant extremes of the montage style were purged.

But some moments recall the silent era. These passages are typically motivated, as in Hollywood and other national traditions, by rapid action. Military combat calls forth stretches of 2-4 frame shots of bombardment in The Young Guard, Part 2 (1948). The combat scenes of The Battle of Stalingrad (1949) include very brief shots. In one passage, an artillery blast consists of three frames—one positive, a second negative, and a third positive again, creating a visual burst.

The abrupt disjunctions of the 1920s style can be felt a little in one cut of The Fall of Berlin (1950), when at the end of a long reverse tracking shot, Alyosha and his comrades rush the camera. Cut to Hitler recoiling, as if he sees them.

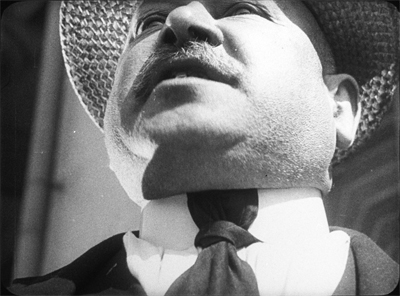

As you’d expect in an academic tradition, the use of fast cutting for fast action isn’t disruptive. A little more unusual is the embrace of wide-angle lenses, often more distorting than in Western cinema. Wide-angle imagery was used by 1920s filmmakers, often to caricature class enemies or to heroicize workers. The same sort of thing can be seen in Kutuzov (1945), when a soldier is presented in a looming close-up, or in Front (1943), when a gigantic hand reaches out for a telephone.

This use of wide angles to give figures massive bulk continued through the 1950s, as in The Cranes Are Flying (1957).

The 1940s aggressive wide-angle shots run parallel to Hollywood work, when in the wake of Citizen Kane (1941), The Little Foxes (1941), and other films, many directors and cinematographers created vivid compositions in depth. Those weren’t unprecedented in America, as I try to show in the style book, but there were some early adopters in Russia as well.

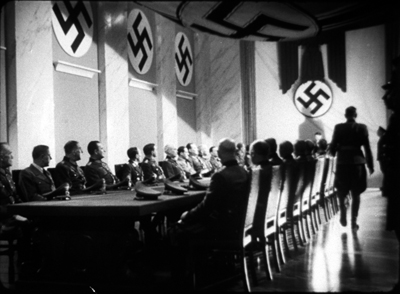

Obliged to show meetings of saboteurs, workers, generals, and party leaders, Soviet filmmakers had to dramatize people in rooms, talking at very great length. The result was a tendency toward depth staging and fairly long takes. The low-angle depth shot stretching through vast spaces became a hallmark of this academic style in the 1930s and after.

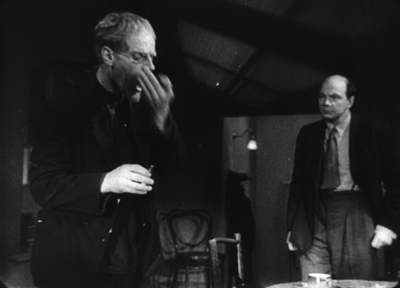

Director Fridrikh Ermler, one of the few directors who was a Party member, claimed that he devised a “conversational cinema” to deal with the prolix dialogue scenes in The Great Citizen (1937, 1939). The movie teems with shots that wouldn’t look out of place in American cinema of the 1940s.

As a solution to the problem of talky scenes, staging of this sort makes sense as a way to achieve some visual variety, and to show off production values. By the 1940s, such flamboyant depth became even more exaggerated. We see it in the telephone framing from Front above, as well as in The Young Guard Part 1 (1948, below left) and the noirish stretches of The Vow (1946, below right).

The Fall of Berlin can use depth to contrast the placid self-assurance of Stalin with a ranting Hitler, bowled over by his globe. Is this a reference to the globe ballet in The Great Dictator?

It’s well-known that for Kane Orson Welles and Gregg Toland wanted to maintain focus in all planes, sometimes resorting to special-effects shots to do so. The Soviets valued fixed focus as well, as several shots above suggest. It could be maintained if the foreground plane wasn’t too close, and the depth of field would control focus in the distance. Hence many shots use distant depth. At one point in The Great Citizen, when a woman interrupts a meeting, the official in the foreground trots all the way to the rear to meet her.

The sense of cavernous distance is amplified by the wide-angle lens.

But sometimes pinpoint focus in all planes wasn’t the goal. Another way to activate depth was to rack focus. In this scene of Rainbow (1944), the man who has betrayed the village comes home and discovers a delegation waiting to try him. At first they’re out of focus, but when he turns they become visible.

Focused or not, some of these shots push important action to the edge of visibility in a way that would be rare in American cinema. In A Great Life, a snooper is centered but sliced off by a window frame and kept out of focus, while a trial scene is interrupted by a figure far in the distance who bursts in to announce a mine collapse.

The Great Citizen shows Shakhov discussing a suspect, who hovers barely discernible in the background over his left shoulder. I enlarge the fellow and brighten the image.

This makes Wyler’s sleeve-shot in The Little Foxes seem a little obvious.

The Great Whatsis and the masters of the 1920s

The New Moscow (1938).

If American movies favor titles called The Big …., the Soviets liked The Great …. (Velikiy). But The Big Sleep doesn’t look all that big, and The Big Sick is big only to a few people, and The Big Knife doesn’t even have a knife. In the USSR, calling something big summoned up monumentality. Stalinist culture was grandiose in its architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, and even music, with symphonies of Mahlerian length and oratorios boasting hundreds of voices.

Accordingly, one effect of the depth aesthetic was to grant the characters and their settings a looming grandeur. Earth-changing historical events were being played out on a vast stage that framing and set design put before us.

Naturally, battles are on a colossal scale. Napoleon broods in the foreground (Kutuzov) and troops march endlessly to the horizon (The Vow).

1940s films feature wartime landscapes on a scale almost unknown to Hollywood. If God favors the biggest battalions, God would seem to love the Russians (a prospect that otherwise seems invalidated by history). Below: The Battle of Stalingrad.

These landscapes are surveyed in long tracking shots, a habit that survived in Bondarchuk’s War and Peace (1966-1967).

Soviet forces command impressive headquarters (The Great Change, 1945), perhaps necessary to balance the Nazis’ resources (The Vow).

Parlors and committee rooms are remarkably big, and even prison cells (The Young Guard Part 2) and farmhouses (The Vow) have plenty of room.

Gigantism wasn’t unknown in 1920s cinema, or in Russian painting both classic and recent. The Vow seems to justify its scale by reference to a Repin painting, which the characters see on display.

Not only were the 1920s silent classics monumental; they became monuments. Masha records the veneration that the “master” directors felt for the works of Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Kuleshov, Barnet, and other predecessors. Moments in the Stalinist cinema seem to refer back to that era. The Battle of Stalingrad evokes the mother with the slain child on the Odessa Steps, and The Vow has the nerve to superimpose on Stalin (friend of farmers) an image of concentric plowing from Old and New.

These can be taken as cynical ripoffs, but in a way they testify to the fact that great silent films had forged some enduring iconography.

VIP: Very important, Pudovkin

You don’t hear much about Pudovkin’s 1930s and 1940s films, but they can be exuberantly strange. Eisenstein aside, he stands in my viewing as the director who played around most ambitiously with the academic style. Perhaps he was encouraged in this by his young codirector Mikhail Doller, but Pudovkin had already tried out some audacious strokes in A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933).

For a high Stalinist example take Minin and Pozharsky (1939). This tale of seventeenth-century warfare seems virtually a reply to Alexander Nevsky (1938), as Mother (1926) responded to Strike (1925). Minin opens with statuesque staging reminiscent of Eisenstein’s film, but the scene is handled in telephoto shots and to-camera address. The combat scenes employ handheld battle shots, along with close-ups of fighters and horsemen that aren’t stylized in the Nevsky manner.

But there’s more than pastiche here. One battle shows the Russian forces rushing from the left in tight tracking shots, while the enemy forces move from the right in panning telephoto. Especially striking are axial cuts, beloved of Soviet filmmakers for static arrays, employed in movement. Horses sweep past a tent in extreme long-shot; they smash into the tent in long shot; and in a closer view the tent lies trampled as other horses continue to flash through the foreground.

The shots are 50 frames, 38 frames, and 13 frames respectively. For a moment, we might be back in the great era of Soviet editing.

Victory from 1938 is a drama in which aviators set out to rescue an interrupted around-the-world flight. Here Pudovkin and Doller invoke the depth staging of the era only to disrupt it with what we might call “smear” cuts.

During the parade for the departing airmen, for instance, a young man happily tossing papers, in another grotesque wide-angle shot. He’s blocked by a man passing through the frame. Match on action cut to another figure, close to the camera and moving in the same direction. This figure wipes away to reveal a man reading a newspaper.

This sort of weird graphic match becomes a stylistic motif in the film. Later, when the rescue has been completed, another crowd scene yields a similar pattern of depth smeared and exposed. A shot of the parade is sheared off by a woman’s passing face. That cuts to a man’s passing face, which moves away to show the crowd behind him.

The patterning pays off when the victorious plane rolls triumphantly through the frame, blotting out the image, to be graphically matched by a passing figure who unveils the pilot’s mother embracing him.

In Admiral Nakhimov (1947) Pudovkin and Doller employ the smear-cutting technique during a battle scene. Stills are totally unable to capture the way this looks. Soldiers charge up a hill, and their falling bodies, briefly blocking the camera’s view, are given in jump-cut repetitions that suggest, through a spasmodic rhythm, the sheer difficulty of advancing.

Even stranger is the moment when soldiers rush toward a distant fortification, with a latticework basket in the foreground. Cut to the hill edge, with a comparable blob moving leftward through the frame. It turns out to be a fighter’s shoulder.

The oddest part is that this second shot is only six frames long, and every frame after the first is a jump cut; that is, some frames have been dropped as the blob makes its way across the image. The effect on your eye is percussive, and seems to be anticipated by Pudovkin’s experiments in popping black frames into shots in A Simple Case. What kind of director thinks like this?

Of course these Pudovkin/Doller films also subscribe to the official look, with monumental depth staging. The films acknowledge the 1920s tradition as well. Admiral Nakhimov casts a personal look back to Pudovkin’s great rival. A shot of the crew’s tautly bulging hammocks recalls, maybe cites, the crew’s sleeping area of Potemkin.

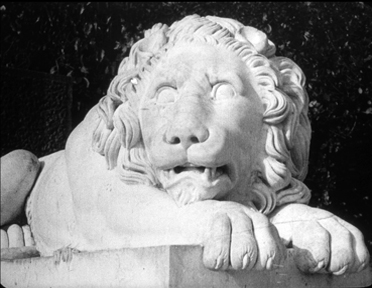

In Odessa, Admiral Nakhimov echoes Potemkin even more strongly. We get waving crowds, the stone lions, and a reminder of those famous steps.

In sum, the Stalinist cinema holds a unique interest for students of the history of film style. Not only did it apparently constitute a significant development in technique, but in forming a tradition, it provided a counterpart and sometimes a counterpoint to developments in the West. Later that tradition became something for directors to react against (Tarkovsky and Sokurov come to mind) or to adapt to new purposes (I’d put Jancsó in that category). For all the behind-the-scenes bungling, it became much more than a propaganda vehicle.

Scholars who study Stalinist film are usually impelled by an interest in propaganda or an interest in the audience’s response. My questions were different. I was driven by my interest in Eisenstein and comparative stylistics. So I tried to investigate the formal and stylistic norms of Soviet cinema. Some of those norms Eisenstein helped create, and then revised for his own ends.

Still, I feel like a butterfly collector picking out vivid specimens for an expert to explain. I can’t supply the hows and whys. How did filmmakers manage to create these remarkable images? What technical resources, of lenses and lighting rigs and film stock and set design, permitted them to craft these striking shots? Were their peers and masters insensitive to this official look? Was it taken for granted? Or was it self-consciously promoted and taught? Some of these schemas are developed in Eisenstein’s lectures at the Soviet film school. And how, at a more micro-level, do these patterns function in the individual films?

As for the whys: Why did filmmakers embrace these options rather than others? And why did they develop, sometimes apparently in a spirit of play, some oddball technical innovations?

Such questions seem to me compelled by films that turn out to be more artistically interesting than most commentators have noted. One of the most corrupt and brutal political systems in world history produced films of considerable interest, and a few of enduring value. I hope experts try to figure this all out. I bet Masha Belodubrovskaya will lead the way. Her new book is a splendid start.

Masha is no stranger to this blog, having translated Viktor Shklovsky’s remarkable “Monument to a Scientific Error” for us.

This is a good place to thank all the people who helped me see Stalinist films in archives over the decades. That number includes Gabrielle Claes, Nicola Mazzanti, and the late Jacques Ledoux of the Belgian Cinematek; Enno Patalas, Klaus Volkmer, and Stefan Droessler of the Munich Film Museum; and Pat Loughney, then of the Library of Congress.

I learned of Ermler’s “conversational cinema” (razgovornyi kinematograf) from Julie A. Cassiday’s “Kirov and Death in The Great Citizen: The Fatal Consequences of Linguistic Mediation,” Slavic Review 64, 4 (Winter 2005), 801-804. The depth aesthetic of high Stalinist cinema proved valuable when 1960s bureaucrats decided to make Stalin disappear. See our online supplement to Film History: An Introduction.

There are more examples of “Stalinist formalism” in On the History of Film Style–recently declared out of print, but soon to appear in a new electronic edition on this site. See also my Cinema of Eisenstein for arguments about how he created and then swerved from some of his peers’ norms.

Today’s Google Doodle pays tribute to Eisenstein on his birthday. But they make him a slim, hip metrosexual. Revisionism can go too far.

Kelley Conway, Masha, and Scott Gehlbach, at a party last night celebrating Masha’s book–and her winning tenure! Kelley’s contributions to our blog are here and here and here.

The ten best films of … 1927

Underworld.

Kristin here:

Once again it’s time for our ten-best list with a difference. I choose ten films from ninety years ago as the best of their year. Some are well-known classics, while others are gems I have found while doing research for various projects–though I have to admit that most of the films on this year’s list are pretty familiar.

One purpose of this yearly exercise is to call attention to great films of the past, for those who are interested in exploring classic cinema but aren’t sure where to start. (Previous lists are 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, and 1926.)

Hollywood dominates this year, with half the list being American-made.

There are reasons for the lack of international titles. This year was was the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but although Vsevolod Pudovkin’s celebratory film The End of St. Petersburg is here, Sergei Eisenstein did not finish October in time and it came out in 1928. (I remember the third anniversary film, Boris Barnet’s Moscow in October, as good but not necessarily top-ten material.) Some major directors didn’t release a film or made a lesser work. Dreyer was at work on The Passion of Joan of Arc, but it, too, wasn’t released until 1928. Lubitsch made The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, a good but not great entry in his oeuvre. Japan’s output is largely lost. Yasujiro Ozu made his first film in 1927, but his earliest surviving one comes from 1929. Most of Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1920s films are gone, including those from 1927.

1927 was the year when Hollywood dipped its toe in sound filmmaking, but we need not worry about the talkies for now. Instead, all ten titles are examples of the state of sophistication that the silent cinema had achieved by the eve of its slow demise. (Sunrise‘s recorded musical track does not a talkie make.)

Hollywood, comic

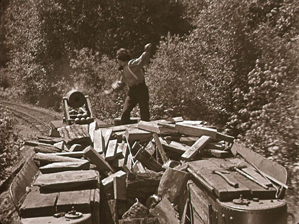

The General is often listed as a 1926 film. This is technically true, in a sense, but I choose not to count its world premiere in Tokyo on December 31, 1926. Its American premiere was scheduled for January 22, 1927 but was delayed until February 5 by the popularity of Flesh and the Devil, which was held over in the theater where Keaton’s film was eventually to launch.

David recently posted an entry on how the great silent comics moved from shorts in the 1910s to features in the 1920s. His example was Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy, one of our ten best for 1924. Keaton moved into features slightly later than Lloyd, excepting The Saphead (1920), an adaptation of a play, in which Keaton was cast in the lead but over which he had no creative control. Once he did tackle features, he soon became adept at tightly woven plots with motifs and sustained gags. The General, based on a real series of events during the Civil War, has a solid dramatic structure that is more than just an excuse for a bunch of humorous bits. (A dramatic film, The Great Locomotive Chase, was produced by Disney in 1956 and based on the same events.)

The French title of The General is Le Mécano de la General. One might call Keaton that, since The General‘s comedy is essentially a long set of variations on the humor to be gotten out of the physical characteristics of a Civil-War-era train and its interactions with tracks and ties. Keaton had always been fascinated by modes of transportation and other mechanical sources of gags: an earlier train in Our Hospitality, boats in The Boat and The Navigator, a DIY house (One Week), film projection in Sherlock Jr., and so on.

At the beginning, Keaton’s character, Johnny Gray, tries to enlist in the Confederate army, but he is rejected without explanation. The officers consider him more valuable as a train engineer. Later, when Johnny is taking troops up to the front, a group of disguised Union soldiers steal his beloved engine, “The General.” Pursuing the thieves, he ends up deep in Union-occupied territory and takes his engine home, just in time to participate in a battle and prove his worth as a soldier.

The perfection of Keaton’s construction of gags is evident in one famous scene where Johnny’s engine is towing a cannon pointed up at an angle that would clear the cab if it were fired. Johnny has just loaded it with a cannon-ball and lit the fuse; he is returning to the engine when he foot becomes caught in the hitch attaching the cannon to the fuel car. The hitch drops, jolting against the ties so that the cannon slowly sinks to point straight ahead. A cut to a side view shows Johnny noticing this and panicking.

A view from behind the cannon emphasizes his danger as he starts to climb into the fuel car but gets his foot caught in the chain, a situation made clear by a cut-in. Once he is atop the wood-pile, he throws a log which fails to shift the cannon’s aim.

A cutaway establishes the Union soldiers who have stolen the General, approaching a lake in the background. Back at the pursuing engine, Johnny gets onto the cowcatcher, as far from the cannon as he can get. A return to the previous framing shows Johnny’s engine starting to turn on a curving stretch of track with the lake in the distance. The cannon follows.

As Johnny’s engine moves just out of the cannon’s trajectory, it fires. This would be enough for the pay-off of this elaborate gag, but the smoke quickly blows aside (possibly a wind machine offscreen left?) and we see the explosion in the distance near the General. As so often happens with Keaton’s gags, we are likely to gasp in amazement at the moment’s sheer physical complexity and ingenuity, as well as Keaton’s dexterity, before we start laughing.

The consensus among most critics and historians is that The General is Keaton’s finest film. In my opinion it goes beyond the top ten for a year to the top ten, period. Participating in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll of scholars and filmmakers, I put it in my list of ten films. It only made it to number 34 among voters, but then, my opinions didn’t coincide too well with the “winners.” Only two of the top ten were on my list. Such exercises are hardly definitive, given how difficult it is to choose among films at the highest levels of brilliance. That’s why David and I tend to stay away from them–except for films made ninety years ago.

Harold Lloyd’s The Kid Brother is similarly one of his finest, along with Girl Shy (featured on my 1924 list and discussed by David in a FilmStruck introduction and his entry linked above). As David points out, Lloyd’s features usually give his character a flaw to overcome. Here, as a country boy overshadowed by his tough father and two older brothers, he believes himself to be timid and not worth much. He eventually proves himself, of course, partly from a desire to save his father, who is wrongly accused of stealing some money, and partly through the encouragement of Mary, owner of a medicine show passing through town, with whom he falls in love.

Harold Hickory is quickly set up as fantasizing that he is as capable as his father, the local sheriff, when he holds his father’s badge against his chest (see the top of this section). Not just a prop for character exposition, however, the badge leads him to be mistaken for the real sheriff. In trying to pass himself off as a convincing sheriff, he sets in motion a series of events that lead to the accusation of theft against his father and his attempts to recover the money from the real thieves.

As with Keaton, one of Lloyd’s strengths was an ability to plan a gag to use the whole frame, whether in depth or from side to side. The film stages several scenes in depth, as when the dishonest medicine-show men who will eventually steal the money arrive to try to get a permit to perform in town. As they arrive, Harold is seen in depth, wearing his father’s hat and badge, thus setting up the idea that they will believe that he is actually the sheriff. A more extended example occurs later, when he meets and is attracted to Mary, he climbs a tree to call after her as she leaves him, disappearing again and again behind a hill in the distance, and reappearing each time he climbs higher.

Lloyd skillfully employed shallow space equally well. When the medicine-wagon is destroyed by fire, Harold invites Mary to spend the night at his house. A disapproving neighbor lady soon takes her away, and Harold sleeps on the couch he had made up for Mary, complete with a tablecloth hung to give her privacy. Believing Mary still to be in bed, the two brothers separately sneak in to court her by primly handing her breakfast and gifts around the edge of the cloth. A shot from the other side shows Harold pretending to be Mary and enjoying being served food by the brothers when it is usually he who does the cooking.

Like The General, The Kid Brother demonstrates the sophistication that the great silent comedians had achieved by the late silent period.

As with the Lloyd films included in previous lists, The Kid Brother was released in the 2005 New Line boxed set, “The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection,” now out of print and available only from third-party sellers. Sold separately, Volume 2 is still in print; it contains The Kid Brother and The Freshman, as well as other important Lloyd films. Volume 3 is still available new from third-party sellers. Volume 1 is available from third-party sellers, mainly in used (and higher-priced copies).

Hollywood, serious

The popular impression seems to be that the gangster genre originated in the early sound period. Wikipedia’s entry on the subject treats Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), and Scarface (1932) as the first gangster films. There had been occasional silent films that could fit into that category, notably The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912, D. W. Griffith) and Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915, Maurice Tourneur). In 1927, however, Josef von Sternberg made Underworld, which basically defined the genre that would soon become more prominent.

It has the gangster’s little mannerism, with “Bull” Weed bending coins to show off his strength (possibly the source of the cliché of the gangster flipping a coin). There’s the emblematic and ironic death, as when Bull’s nemesis “Buck” Mulligan is shot and falls at the foot of a cross-shaped memorial arrangement of flowers in the shop he uses as a front. There’s the thug with a heart of gold redeemed by the loyalty of a friend.

Von Sternberg is most often associated with Marlene Dietrich, whom he directed in seven films in the 1930s. He built three of his last four films of the late 1920s, however, around the burly star George Bancroft (below left). (We will encounter the second in next year’s list.) He’s also associated with beautiful design and cinematography, and the look of Underworld often anticipates the films noir of the 1930s (above, top, and below right).

I’ve already written about Underworld in greater detail than I have room for here–with additional pretty pictures. That was on the occasion of Criterion’s release of a set containing von Sternberg’s last three silents. Still indispensable but out of print and selling for high prices when you can find it. (Time for a Blu-ray?)

Late in her life, I asked my mother (born in 1922) what the earliest film she could remember seeing was. She replied that she couldn’t give me the title but recalled an image: a woman floating on a lake supported by reeds. I was quite astonished, partly because of all possible late 1920s films she had mentioned one which I could identify instantly from that brief description and partly because her memory had retained an impression of one of the great classics of the silent cinema. Living on a farm in Ohio, my mother probably saw it in a late run and so probably was six or seven at the time.

The presence of Sunrise on this list will hardly come as a surprise to anyone. Murnau has been a regular, appearing in our 1922, 1924, 1925, and 1926 entries. His first Hollywood film was thoroughly Murnauesque in style. It’s story of village versus country with a lingering touch of Expressionism in the rural scenes (below left) and modern design on ample display in the city (below right). The action could be set equally plausibly in Germany or the USA, except for the English-language signs in the city.

The plot is simplicity itself, with none of the characters even given a name. A Man is seduced by a Woman from the City, who convinces him to drown his Wife “accidentally” and flee with her to the gaiety of urban life. He nearly pushes his Wife into the lake while rowing across to the mainland but relents and tries to gain her forgiveness. This all occupies less than half the film, and most of the rest consists of the couple going forlornly to the city, with the Wife heartsick and the Man pathetically trying to reassure her. Once they reconcile, there is a long stretch of them having a good time in the city before heading home.

Yes, a good time. One might expect the city to be a hotbed of decadence that contrasts with their virtuous country life, but apart from an aggressively flirtatious gentleman, most of the people they meet are kind to them. A friendly photographer thinks they are a newly married couple and takes their portrait, sophisticated patrons at the dance-hall appreciate their performance of a country dance (below), and so on.

This meandering little set of unconnected vignettes does not conform to the Hollywood ideal. It presumably aims to guarantee that we believe in the husband’s redemption and the couple’s future happiness after their symbolic “re-marriage.” It holds our attention partly because of the charm of the two lead actors, George O’Brien and Janet Gaynor, and partly because the visual style always gives us something to look at. Murnau uses his “unfastened” German-style camera movements, not only in the famous track to the marsh early on but in a movement over diners’ heads accomplished by placing a camera on a support suspended from a track on the ceiling. (This technique was being widely adopted in Hollywood during the second half of the 1920s.)

Plus there’s that memorable scene of the Wife drifting on the lake, supported by reeds.

Sunrise is available in the elaborate 2008 12-disc boxed-set “Murnau, Borzage and Fox,” though the print is the usual soft, rather dark one available elsewhere. (The main gems of the box are the rare Borzage silents, including Lazybones, one of my 1925 picks.) Eureka! put out an edition of Sunrise as the first entry in its “Masters of Cinema” series. It contains not only the same print but a second print, a Czech release with distinctly better visual quality. (The image of the restaurant directly above was taken from it, while the others are from the “Fox Box.” I have not made a comparison between the two, but apparently the Czech version has significant differences from the American one.) This edition is out of print. Eureka! now offers the same two prints and supplements as a DVD/Blu-ray combination. Note that (despite what the Amazon.uk page says), this is a region 2 DVD and region B Blu-ray; both would require a multi-standard player in the USA and other regions.

The same “Fox Box” set contains Frank Borzage’s 7th Heaven, one of his best-loved films. By rights it should not be a great film. It is intensely sentimental, depends on huge coincidences, and has a thoroughly implausible ending, not to mention a saccharine religious theme that runs through it. Yet somehow it manages to be the greatest hypersentimental, coincidence-ridden, implausible, pious film ever. I cannot explain how or why.

Borzage’s film looks a lot like Sunrise, and it is often assumed that the resemblance arises from a straightforward influence of Murnau upon Borzage (e.g., his Wikipedia entry states that Borzage was “Absorbing visual influences from the German director F. W. Murnau, who was also resident at Fox at this time”), even though 7th Heaven was released four months earlier. There is something more complex at work here. The two films’ resemblances are not surprising, since German films had been drawing excited attention among American filmmakers for the past two years or so. The Last Laugh wasn’t a popular success, but its US distributor, Universal, showed it privately for cinematographers and others in the industry interested in studying it. Variety had been a hit. Its techniques of false perspective in sets and cameras moving freely through space soon caught on. For example, the sordid flat that the heroine Diane shares with her sister in 7th Heaven has a rough wooden floor sloping up toward the back (left). A similarly sloping floor appears in the bedroom in Sunrise (right)

German producer Erich Pommer’s first American film, Hotel Imperial (released by Paramount at the beginning of 1927), used a camera elevator, hanging sometimes from a track in the ceiling and sometimes from an improvised support on a dolly (see here for an image of it attached to the latter). The famous vertical elevator shot in 7th Heaven, following Chico and Diane as they ascend to his garret apartment at the top of the building was probably the most flamboyant use of the unfastened camera to that point. Below, in a later shot, the camera follows Chico back down as he goes to fetch water.

German style alone does not explain the film’s status as a great classic, though the slightly exotic look perhaps helped to make the garret romantic enough to be called “heaven” by its inhabitants as they fall in love. As with Sunrise, the Germanic look lends a certain fairy-tale quality that helps smooth over the plausibility issues.

Beyond this, there is again the charisma of the main actors. Janet Gaynor (who was in two of this year’s greatest films) and Charles Farrell (a slightly awkward but appealing actor) became the ideal couple of the late 1920s, co-starring eleven more times between 1927 and 1934. Equally, there is the ineffable directorial sincerity that comes across in Borzage’s best films, a trait often summarized as “romantic” or “naive.”

Unfortunately the print of 7th Heaven in the “Fox Box” is virtually unwatchable. Apparently the French DVD is from a better source than the Fox release; this DVD may be the source of a version which has been posted on YouTube with bright yellow Greek subtitles. The two frames above were extracted from that online copy. Another film calling out for restoration.

Germany: farewell to Expressionism

Expressionism probably would have ended in Germany in 1926, with the releases of Murnau’s Faust and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Both films went over budget and schedule, with Lang’s being late enough to be released on January 10, 1927. Both films contributed to the decline of the large production company, UFA, which had to rely on loans from Hollywood to keep going. Murnau was by this point in America, and he never worked again in Germany. Lang had to produce his next film, Spione (destined for our 1928 list), himself, and he opted for a more streamlined modern look.

Metropolis mixes Expressionism with the sets representing the futuristic science-fiction city. The pleasure garden of the wealthiest class (above), as well as the catacombs and chapel of Maria far under the city are Expressionist, and even in the city sets the crowds often move in the choreographed fashion typical of the style.

Expressionism remained thereafter as a minor stylistic option. (Alexandre Volkoff’s 1928 French-German co-production Geheimnisse des Orients used Expressionist sets to create a fairy-tale Middle-East, rather like The Thief of Bagdad [1924].)

Metropolis has received so much attention that there is no need to plug it again as a great classic. In fact, it has been hyped to the point of being over-valued. Any of Lang’s other films from 1922 to 1928 is arguably better. It has a mawkish main premise (the heart must mediate between head and hands in labor disputes) and plot flaws (why would Fredersen destroy the substructure of his city when his power and dominance depend on maintaining it?), neither of which is a problem in Lang’s other films of this period. It deserves to be called a masterpiece for its audacity of vision, technical innovation, and many great moments.

Fans of the film will be aware that the long-lost scenes of the film were discovered in South America and restored to the film, rendering it nearly complete (running 148 minutes in Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray release). The recovered footage was unfortunately in very worn condition, and restoration can only do so much. The film is, however, much improved by having it.

David has already written on the strengths and weakness of this “great sacred monster of the cinema,” including a discussion of how the restored footage enhances it.

Back in 1970, when I was an undergraduate and first dipping a toe into film studies, G. W. Pabst was considered one of the major figures of German cinema, close to if not quite as great as Lang or Murnau. In my first film course the incomplete version of The Joyless Street was shown. (I liked it much better when it was restored.) I saw The Love of Jeanne Ney shortly thereafter. By now, however, The Joyless Street and Pandora’s Box have become the Pabst classics upon which his reputation is largely based. Whether Jeanne Ney‘s gradual fall into relative obscurity is the cause or the effect of its being difficult to see is hard to say. (I could only find it as a 2001 DVD by Kino, so-so but acceptable in quality.) Either way it’s a pity, since it deserves to be better known.

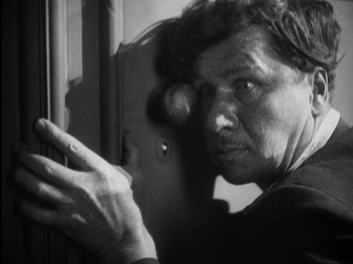

An adaptation of Ilya Ehrenburg’s novel of the same name, Jeanne Ney is set in the Civil War period that followed the Russian Revolution of 1917. The story begins in the Crimea, where Jeanne’s anti-Bolshevik father is a political observer. During the capture of the town by the Red forces, Jeanne’s lover, Labov, kills her father in self-defense. She forgives him and flees to Paris. Jeanne gets a job as a secretary in her miserly uncle’s detective agency, primarily to be a companion to her blind cousin. (Gabriele is played by Brigitte Helm, who was also Maria in Metropolis, thus making her our second actress appearing in two of this year’s top ten films.) A rascally opportunist, Khalibiev (played with sleazy relish by Fritz Rasp, see bottom) tries to marry Gabriele for her money, even though he actually lusts after Jeanne. Killing and robbing the uncle, he pins the murder on Labov.

Stylistically the film is a fascinating mix typical of the late 1920s, when influences were passing rapidly among European countries. It strives for a certain degree of the realism characteristic of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement that Pabst had helped to establish with The Joyless Street. The first part is influenced by the Soviet films that had become popular in Germany only the year before, and the Crimea-set portion could pass for a Soviet film, though not one of the more daring ones. The execution scene (below left), with the rifles sticking into the frame dramatically, was already calling upon a composition typical of the Montage movement. The interrogation of Jeanne takes place in a cluttered headquarters just set up by the conquering Reds (complete with authentic costumes and “typage” casting); the framing emphasizes both Bolshevik ideals and realism, placing in the foreground a soldier trying to make tea.

For the longer Parisian portion of the film, Pabst shot on location, as the French Impressionists were doing. He mixed this sense of realism (below left) with subjective scenes, including Jeanne’s superimposed vision of her wrongly-accused lover being executed. The film has one great set-piece, the cousin’s gradual discovery of her father’s murder as Khalibiev stands watching, thoroughly spooked by her blind staring face (below right).

Time to bring this film back into the canon.

Much more familiar is Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt, with which Walter Ruttmann brought the city symphony into the mainstream and solidified a growing strain of realism in German cinema. There had been short films and features that wove together visual motifs from urban life (e.g., Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand’s Manhatta, 1921), mostly captured on the fly though occasionally staged.

Ruttmann has been mentioned on previous ten-best lists for his abstract animation. Berlin begins with some moving abstract shapes that gradually give way to a train journey. During this real objects create abstract patterns, as when the girders of a bridge create a flicker effect as they flash by (below left).

The journey ends in a major station in the city. From there on, Ruttmann cuts together scenes to create what was to become a familiar city-symphony time-frame, a day in the life of a metropolis. Empty, silent streets lead to an early-morning dog-walker (above right) and then the bustle of the workday, lunch, and finally nightlife.

To this point most experimental films had been short and either abstract or surrealist. That experimentation could emerge from the documentary mode was a new concept, and Berlin, though it may not seem very radical to us today, helped to establish this new approach. The fact that it was co-produced by Fox Europa gave it distribution in mainstream theaters, and it has had a great influence on subsequent filmmaking, right up to the present. Coincidentally, that influence is demonstrated by the recent release of Alex Barratt’s London Symphony: A Poetic Journey through the Life of a City (2017). Flicker Alley’s liner notes include:

The release of this Blu-ray coincides with the 90th anniversary of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927), one of the most important examples of the original city symphonies. Ruttmann was one of the great pioneers of experimental film, and Barrett and [James] McWilliam [composer] have worked hard to bring a similar sense of poetic playfulness to London Symphony, while also updating the form for the 21st Century.

Berlin is available in several DVD editions, but the definitive one is in a two-disc set including Ruttmann’s Die Melodie der Welt, the first German sound film, both in restored versions from the Filmmuseum series, as well as Ruttmann’s short abstract films. I note that this is available on Amazon in the USA, but be aware that it’s PAL and so requires a multi-standard player.

The essence of French Impressionism in 38 minutes

I know most readers will expect a much, much longer French film about Napoléon to be in this spot, but I’m opting for Jean Epstein’s modest but brilliant short feature, La Glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”). Perhaps no other film of the Impressionist movement managed to create a plot that combines the subjective techniques that delve into character psychology with the presentation of events through fleeting impressions rather than linear causality. Most Impressionist films today seem a bit old-fashioned, adhering to the modernism of the era. La Glace seems familiar to aficionados of Resnais or Antonioni.

Epstein divides his brief tale of his protagonist, an unnamed playboy, into three parts devoted to the women–a wealthy society woman, a modern sculptor, and a modest working-class woman–who are all having affairs with him at the same time. Each tells her tale of his callousness and neglect to a sympathetic listener, and each presents a very different view of him. Intercut with their stories are scenes of the protagonist taking a solo ride in his sports car (above), speeding through the countryside and stopping at a local fair. Throughout he seems happier than he had with any of his lovers.

The individual scenes are brief, with quick cutting presenting glances and gestures, often from angles that prevent our getting a good look at what is happening, as with this moment in a restaurant.

We grasp what is going on primarily because the events are extremely simple. In each case the protagonist is with one of the women and abruptly walks out on her. The third tale, told by the working-class Lucie, is cut together in nearly random chronological order and with parts of the action missing. Lucie has prepared a romantic dinner at her home, but the man arrives, greets her, looks over the table, and leaves. In this snippet, however, his looking over the table is followed immediately by a shot of him just after his arrival, as Lucie embraces him and removes his hat.

The narrative achieves closure, but the film ends with an emblematic shot of the hero superimposed over a three-sided mirror, emphasizing the differences in the three women’s perceptions of him. La Glace à trois faces goes perhaps as far as any silent film does in using challenging modernist tactics, frustrating the viewer with a lack of clarity about causes and traits. It was a new form of narration that had little immediate impact on the cinema. The film was barely seen at the time. It would not be until decades later that similar techniques became common.

La Glace is available in the boxed-set of several of Epstein’s films, which I described and linked here. It is also included in Kino’s “Avant Garde” set on the 1920s and 1930s.

Tracing the birth of a Bolshevik

One can see why the Soviet government liked Pudovkin best among the major Montage directors. His films, while employing the fast cutting, dynamic angles, and other stylistic traits of the movement, are fairly straightforward and comprehensible compared to, say, Eisenstein’s pyrotechnics in October.

While the latter concentrates on the events of the Revolution proper, with no single character singled out for us to identify with, Pudovkin works up to the Revolution by following the radicalization of a peasant. The unnamed “Village Lad” sets out from his impoverished rural home to find work at a factory in the big city. We see the fomenting of a strike over dangerous working conditions and extended work hours, which begins as the Lad arrives. Ignorant of politics and the class struggle, he seizes his chance to join the scabs replacing the workers. Even worse, he betrays some of the strike’s leaders to police.

The story moves away from the Lad, who really is not very prominent in the narrative and is never characterized enough to gain much sympathy. As World War I begins, the film focuses on stock-market manipulation and war profiteering. Using typical typage casting, Pudovkin caricatures the capitalists as fat cats out for themselves (above). Eventually we see the Lad again, now wiser in the ways of the world and ready to serve the Bolshevik cause. By the end, the Reds attack the Winter Palace in a suspenseful scene, though one much shorter than the one in October.

Pudovkin featured on our list last year, for his best-known film, Mother. There the hero and his mother gain a good deal more sympathy than the Lad does, and The End of St. Petersburg is as a result perhaps a less entertaining film than Mother. Still, it is a masterly film and one of the gems of Soviet Montage.

While rewatching End on DVD, I realized that the main editions available used the same version of the film, a sonorized “restoration” done by Mosfilm in 1969. What other changes might have been made are not apparent (some films “restored” in that period were recut), but the images are severely cropped. The left side of the frame is missing, more than what one would expect would be necessary to add a sound track. The top and bottom, too, are missing portions. Only the right edge seems more or less intact.

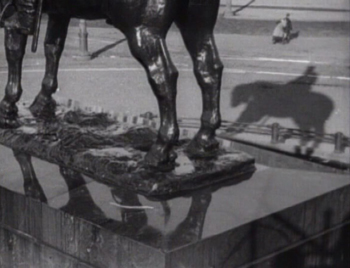

Take this famous image. The film has set up a motif of statues that come to stand for the imperial-era city. At one point there is a depth shot past an equestrian statue looming in the foreground while the Lad and his companion are seen as tiny figures walking across the square in the background. Compare the DVD image with one taken from an archival 35mm print.

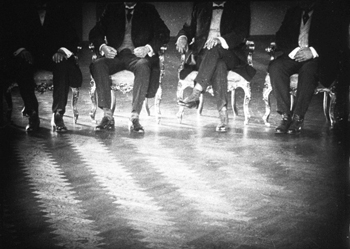

This is bad enough, but when Pudovkin starts using the edges of the frame to make ideological points, the result nearly negates the his meaning. A famous shot shows a row of seated military officials with their heads offscreen. The 35mm image cuts them off precisely at the collar. The DVD print goes down to mid-chest, while losing much of the fourth man on the left. One might say that the same simple metaphor is being presented, but it’s not as instantly apparent what Pudovkin is implying here.

So while I recommend this film, I have to caution readers that it is not currently easy to see it in an acceptable print. An older 16mm copy or a 35mm screening in an archive would be ideal but not accessible to very many. If you want to see it, even in this faulty version, the Image and Kino releases both contain the Mosfilm print. The Image DVD has End paired with Pudovkin’s very worthwhile first sound film, Deserter (1933). Since it was a sound film to begin with, Deserter is not significantly cropped here and is quite good visually. Unfortunately this version is long out of print. The Kino DVD includes Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930) and Pudovkin’s short comedy Chess Fever (1925). It is available for sale and streaming on Amazon. Perhaps our friends at one of the home-video companies dedicated to putting out restorations on DVD and Blu-ray might consider tackling this key title.

For readers who prefer streaming, The Kid Brother, Sunrise, and Metropolis are currently available at FilmStruck on The Criterion Channel. Underworld, The General, The Love of Jeanne Ney, Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, La Glace à trois faces, and The End of St. Petersburg are held in MUBI‘s library, but none is currently playing there. We haven’t checked any of these versions.

Flicker Alley’s London Symphony is available for streaming here and on MOD Blu-ray.

Our colleague Vance Kepley has written a book in the Taurus Film Companion series on The End of St. Petersburg. It seems to be slipping out of availability on amazon.com, can still be had at amazon.co.uk, and is available directly from the publisher. Malcolm Turvey discusses some of the films on our list in his The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s.

December 28, 2017: Our thanks to Manfred Polak, who sends some good news about a restoration and possible upcoming availability of one of our films: “A restored version of “The Love of Jeanne Ney” was shown in an open-air event in Berlin last August. This version also aired on German-French TV station Arte, and it was available for legal download and streaming in HD for three months. I think there might be a DVD or Blu-ray of this version in a few months.”

The Love of Jeanne Ney

The Fabulous Forties once more: REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD spreads out on the Net

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

DB here:

A couple of weeks ago, when I was in New York for the Museum of the Moving Image series based on Reinventing Hollywood, I also met with Violet Lucca, who runs the admirable Film Comment podcast. She and Imogen Sara Smith talked with me about the book. Our conversation is here.

Our session helped me to develop, somewhat babblingly, points I only touched on in the book. For example, there’s the idea that 1940s films aimed at a certain “novelistic” density (or heaviness, if you’re not sympathetic to them). That’s opposed to the fast-paced “theatricality” of many 1930s films. Of course there are exceptions, and complete outliers like The Sin of Nora Moran, a favorite of mine that Imogen mentioned.

Likewise, I got to reemphasize how filmmakers transformed conventions from fiction, theatre, and radio. And Violet and Imogen were right to draw me out on the role of the screenwriter, which I emphasized more than in my previous research.

It was not only fun but illuminating. Violet and Imogen are very knowledgeable and offered me many good ideas that expanded or nuanced things I tried to say. For example, Violet asked whether the “competitive cooperation” of the 1940s has an echo today. That seems right. Imogen suggested that the emergence of voice-over allowed actors to develop an impassive, internalized acting style characteristic of the 1940s. I wish I’d thought of that. In fact, I wish I’d talked with this pair before I wrote the book.

And yes, Daisy Kenyon is involved.

Also a click away from you is an extract from the book put up on Lapham’s Quarterly. It pulls a section from the first chapter about how amnesia works in popular storytelling. Maybe you’ll find it interesting.

Finally, Daniel Hodges kindly spotlighted Reinventing Hollywood in his very serious, in-depth website devoted to problems of film noir. While my book doesn’t say much about noir, since that wasn’t an operative category for creators of the period, my discussion of the woman-in-peril plot chimes with his very detailed study of many films in this vein. In addition, Daniel offers subtle suggestions about less-discussed sources of noir visual style, and he makes a strong case for spy films as being as important to the trend as hardboiled detective stories.

Thanks to Violet and Imogen for a very enjoyable hour, to Daniel for the link, to Lapham’s Quarterly, and to Rodney Powell and Melinda Kennedy of the University of Chicago Press.

The Sin of Nora Moran (1933).